INTRODUCTION

Vesicomyids are one of the most often mentioned taxa associated to megafaunal communities based on chemosynthesis. The presence of representatives of this family are used thus as indicators of benthic reducing environments in the world Oceans. Calyptogena gallardoi has been recently described by Sellanes & Krylova (Reference Sellanes and Krylova2005), at the Concepción Methane Seep Area, in the eastern South Pacific. This new species extends the range of the genus Calyptogena to 36°22′S in the oriental margin of South America; more specifically, to the area of the Chilean margin, where the presence of an extensive gas-hydrate field between 35°S and 45°S has been inferred based on acoustic surveys (Grevemeyer et al., Reference Grevemeyer, Diaz-Naveas, Ranero and Villinger2003; Morales, Reference Morales2003). Conservative estimates of the volume of gas stored as gas-hydrate in subsurface sediments of this area are in the order of 3.2 × 1013 m3, roughly 3% of the world total (Morales, Reference Morales2003). Despite the extension of this area there is very little knowledge on the structure and composition of the benthic communities associated to these cold seeps and the metabolic rates of the species inhabiting the environment where the gas-hydrates are located are totally unknown. Here, we report the enzymatic activities associated to energetic metabolism of Calyptogena gallardoi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples were obtained from two dredge hauls conducted off Concepción (36°21.46′S 73°44.08′W, water depth 934 m, and 36°16.40′S 73°40.70′, 651 m) during the ONR/PUCV/UDEC Cruise (8–21 October 2004) onboard the AGOR ‘Vidal Gormáz’ (Oceanographic and Hydrographic Service of the Chilean Navy). The objective of the cruise was a survey of the hydrographic conditions, methane seepage and associated chemosynthetic communities in the bathyal zone off central Chile. Three specimens were analysed for their enzymatic activities present in foot, gill and abductor muscle tissues. Each tissue was analysed using three different sub-samples and each sub-sample was determined in triplicate. Enzymatic activities were measured at saturated concentrations of substrates and co-substrates. The homogenization buffer included 80 mM phosphate buffer (K2HPO4), pH 7.9, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, except for ETS), 0.3% (wt/vol) polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 g during 5 minutes at 4°C. An aliquot of the supernatants was used for enzymatic assays. Pyruvate oxidoreductases (PORs: lactate dehydrogenase, LDH, EC 1.1.1.27; octopine dehydrogenase, OPDH, EC 1.5.1.15; alanopine dehydrogenase, ALPDH, EC 1.5.1.17 and strombine dehydrogenase STRDH, EC 1.5.1.22), were measured with a reaction mixture based on the method of Schiedek (Reference Schiedek1997). The measurement of ethanol dehydrogenase (EtOHDH, EC 1.1.1.1), was based on the method of Bergmeyer (Reference Bergmeyer1983). However the reverse reaction was done using acetaldehyde as substrate. The reaction mixture contained 80 mM K2HPO4 buffer pH 7.9 at 20°C, 0.1 mM NADH and 3.2 mM of acetaldehyde. The activity of L-MDH was assayed as it catalysed the formation of malate from oxaloacetate using the general procedure described by Childress & Somero (Reference Childress and Somero1979) and Vetter et al. (Reference Vetter, Lynn, Garza and Costa1994). The fumarate reductase (FR) activity was assayed using Schroff & Schöttler's procedure (Reference Schroff and Schöttler1977).

All reactions for dehydrogenases were started by the addition of the supernatant. The absorbance was monitored at 340 nm following the addition of the supernatant. Enzymatic activity measurements were corrected for unspecific NADH oxidation. Furthermore, OPDH, ALPDH, and STRDH were corrected for LDH activity and unspecific NADH oxidation. The assay of citrate synthase (CS) activity was modified from Childress & Somero (Reference Childress and Somero1979) and Vetter et al. (Reference Vetter, Lynn, Garza and Costa1994) whereas the activity of the respiratory electron transport system (ETS) was determined based on the method of Packard (Reference Packard, Jannasch and Williams1985).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

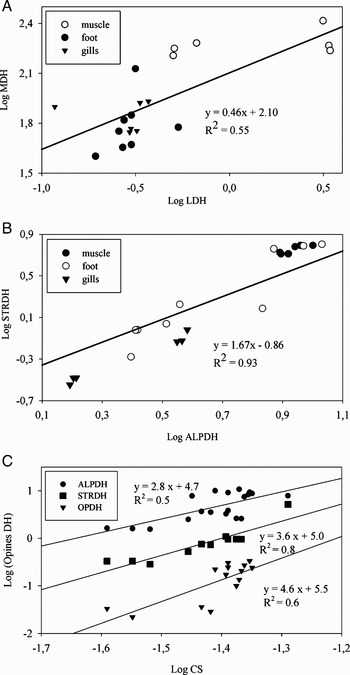

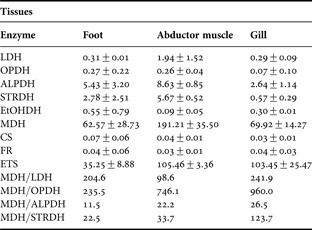

Studies on the physiological and biochemical adaptation of organisms inhabiting deep sea ecosystems fuelled primarily by chemosynthetic oxidation of hydrogen sulphide in thermal vents and methane seepages have been mainly focused on symbiotic relationships with sulphur methane-oxidizing bacteria and its metabolism (e.g. Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Gaill and Felbeck2001; Goffredi & Barry, Reference Goffredi and Barry2002). Nevertheless, there are very few studies (e.g. Steven & Somero, Reference Steven and Somero1983; Dodds, Reference Dodds1996) dealing with Calyptogena's enzymatic activities involved in anaerobic and aerobic metabolism. In the present study, the fact that: (i) MDH presented the highest activity of all dehydrogenases analysed in the three tissues studied (Table 1) with similar values to those reported for C. kilmeri and C. pacifica (Dodds, Reference Dodds1996); and (ii) the presence of opines dehydrogenase activity (OPDH, ALPDH, STRDH), is consistent with the metabolism of an organism that must cope with semi-permanent low oxygen conditions (Livingstone, Reference Livingstone1983, Reference Livingstone1991). Anaerobic glycolysis is, comparatively to aerobic metabolism, an inefficient metabolic strategy, generating a maximum of 15% of the ATP synthesized in the aerobic potential metabolism of an organism (Jackson, Reference Jackson1968). For organisms inhabiting indefinitely under anoxic conditions it would be particularly inefficient. However, there is a direct association between an organism's ability to withstand temporary anaerobiosis under oxygen limiting conditions and values of the ratio MDH/LDH; the higher this value, the greater an organism's tolerance to hypoxia (Shapiro & Bobkova, Reference Shapiro and Bobkova1975). In C. gallardoi, the activities of MDH and LDH are positively correlated (Figure 1A) and in all tissues analysed the ratio MDH/LDH is higher than one. The same can be seen in the ratio of MDH with any opine dehydrogense studied (Table 1). The strong relationship found between ALPDH and STRDH (Figure 1B; R2 = 0.93, P << 0.05) suggests a link between the anaerobic and amino acid metabolisms in C. gallardoi because these enzymes share piruvate as substrates but they also use the amino acids alanine (ALPDH) and glycine (STRDH). This link may constitute a regulatory pathway of anaerobic metabolism depending on the amino acid used in the formation of opines which are less acid than lactic acid (Livingstone, Reference Livingstone1983, Reference Livingstone1991).

Fig. 1. Regression between enzymatic activities involved in anaerobic metabolism (MDH versus LDH and ALPDH versus STRDH) as well as between enzymatic activities of aerobic–anaerobic metabolism (CS versus OPDH; CS versus STRDH, CS versus ALPDH). All regressions are significant at P < 0.05. Dehydrogenases activities in μmol NADH min−1 g−1 ww. ETS activity: μl O2 h−1 g−1 ww. CS activity: μmol DTNB min−1 g−1 ww. 1U = μmol min−1.

Table 1. Enzymatic and ETS activity in foot, gill and abductor muscle tissues of Calyptogena gallardoi collected off central-south Chile. Ratios of MDH to opines dehydrogenases are also shown. Dehydrogenases activities in μmol NADH min−1 g−1 ww. ETS activity: μl O2 h−1 g−1 ww. CS activity: μmol DTNB min−1 g−1 ww. 1U = μmol min−1.

Mean±standard deviation.

The ETS activity found in C. gallardoi is low (Table 1) compared with other bivalves such as the Zebra mussel (Fanslow et al., Reference Fanslow, Nalepa and Johengen2001) which has values at least three times higher. Even though the Zebra mussel is not an inhabitant of cold seepages, ETS activity measured in organisms belonging to the same genus living in extreme environments and non-extreme environments do not present major differences (e.g. Sell, Reference Sell2000).

Citrate synthase (CS), which is located at the beginning of the Kreb's citric acid cycle, is an indicator of an organism's maximum aerobic potential (Hochachka & Somero, Reference Hochachka and Somero1984). The CS activity of C. gallardoi (Table 1) is extremely low even when compared to C. kilmeri and C. pacifica (Dodds, Reference Dodds1996) as well as with Vampyroteuthis infernalis, a habitant of oxygen minimun zones, which has the lowest CS activity reported within cephalopoda (Seibel et al., Reference Seibel, Thuesen and Childress1998). Low CS activity has also been reported in the tissue of C. magnifica and therefore this species may also rely largely on anaerobic pathways of energy metabolism (Steven & Somero, Reference Steven and Somero1983). The extremely low CS activity in C. gallardoi suggests a suppression of aerobic metabolism as a response to near anoxic environment caused by the methane seepage. This feature is consistent with an organism adapted to live in low oxygen conditions. The positive relationship found between CS activity and the opines dehydrogenase activities (Figure 1C) suggest a biochemical adaptation of C. gallardoi to low environmental oxygen conditions. These relationships suggest a link between anaerobic and aerobic metabolism, however further research in this subject is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the COPAS Center (FONDAP, CONICYT, Chile). Additional funding for E.Q. and J.S. was provided by Fondecyt 1061217 project.