Article contents

Working memory and inhibitory control among manic and euthymic patients with bipolar disorder

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 April 2005

Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric illness that is characterized by episodes of extreme mood states. The affective components of bipolar disorder have been studied extensively, but only recently have investigators begun to systematically examine its cognitive concomitants. Although executive dysfunction has been reported in this population, especially while patients are manic, the tasks administered in many previous studies have made it difficult to determine the specific executive abilities that were compromised. The present study examined 15 patients with bipolar disorder who were manic, 18 who were euthymic, and 18 healthy participants. Tests were selected to evaluate two specific aspects of executive functioning in these participants. The Object Alternation Task was given as a measure of inhibitory control, and the Delayed Response Task was included as a measure of spatial delayed working memory. All groups performed similarly on the Delayed Response Task. On the Object Alternation Task, however, the manic and euthymic patients committed significantly more perseverative errors than healthy participants. These results indicated that patients in the present sample had relatively normal working memory abilities, but had a deficit in behavioral self-regulation, which was evident across mood states. (JINS, 2005, 11, 163–172.)Location of work: Center for Bipolar Disorders Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society , Volume 11 , Issue 2 , March 2005 , pp. 163 - 172

- Copyright

- © 2005 The International Neuropsychological Society

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric illness that is characterized by episodes of abnormal mood elevation, often with intervening periods of depression. Cognitive symptoms are prominent and may include racing thoughts, distractibility, and severely impaired judgment. Neuropsychological deficits have been documented during periods of mania, including memory impairment (Henry et al., 1971, 1973; Sweeney et al., 2000), inattention (Harmer et al., 2002; Larson et al., 1998; Sax et al., 1995), and executive dysfunction (Larson et al., 1998, 2001; McGrath et al., 1997; Morice, 1990; Murphy et al., 1999; Sweeney et al., 2000). There are also reports of persistent cognitive deficits during periods of euthymia (Cavanagh et al., 2002; Clark et al., 2002; Martinez-Aran et al., 2001; van Gorp et al., 1998). Few studies, however, have compared cognitive functioning between manic and euthymic patients (McGrath et al., 1997) or specifically related cognitive functioning to clinical symptomatology.

It is plausible that impulsive behavior, a defining characteristic of mania, may be related to specific deficits in executive functioning that are not present during euthymic periods. Impairment of component executive abilities (e.g., planning, working memory, response inhibition, organization, and flexible thinking) can lead to unique behavioral syndromes (Levin et al., 1991), some of which resemble mania. For example, working memory deficits may lead to disordered behavior by making it difficult to sustain and organize goal-directed activity, and inhibitory dyscontrol may result in a reduced ability to resist impulsive tendencies. By definition, mania is characterized by impulsive behavior, but it is unclear from the existing neuropsychological literature whether the disordered behavior might be related to defective working memory ability or inhibitory control processes.

Despite the fact that impulsive behavior is such a prominent symptom of mania, only a handful of studies have attempted to measure this construct. This trend is partly attributable to many investigators' reliance upon traditional clinical neuropysychological tests, which often simultaneously measure multiple aspects of executive functioning (McGrath et al., 1997; Morice, 1990). Although such tests tend to be sensitive to overall executive function abilities, their use makes it difficult to examine individual components of the executive system. In contrast, comparative neuropsychologists, who examine animal models of brain injury, employ tests of executive functioning that are more specific. Inhibitory control and working memory represent two dissociable aspects of executive functioning that have been extensively researched in the animal experimental literature (Mishkin et al., 1969; Oscar-Berman, 1975).

Two tasks that have been used extensively by comparative neuropsychologists include the Object Alternation Task and the Delayed Response Task. Primates with ablations restricted to the dorsal regions of the frontal lobes are known to perform poorly on the Delayed Response Task, which measures the ability to retain spatial information over a delay (Goldman-Rakic, 1987). Impairment on the Delayed Response Task following dorsal frontal lesions is one of the best-validated findings in the comparative neuropsychology literature (Goldman-Rakic, 1987). Ventral frontal lesions, in contrast, often disable self-regulatory ability. This deficit has been consistently measured with the Object Alternation Task, which requires the ability to inhibit previously rewarded behavior (Mishkin et al., 1969). Impairment on this task has been found to correlate with poor psychosocial outcome and also with impaired performance on tests involving unstructured situations (Levine et al., 1999).

Although working memory and inhibitory control have been extensively evaluated in the experimental literature, they have only recently been compared in patients with bipolar disorder. Two studies simultaneously examined both working memory and inhibitory control in manic patients (Murphy et al., 1999; Sweeney et al., 2000). Both studies suggested impaired working memory skills in this population, but only one study found evidence for impaired inhibitory control processes (Murphy et al., 1999). These studies employed a combination of verbal and nonverbal tasks; therefore, it is plausible that the discrepant findings may be due in part to deficits in fundamental language skills or visuoperception. Only one study has reported impaired inhibitory control in euthymic patients (McGrath et al., 1997) and there is conflicting evidence regarding the status of working memory in this group (Ferrier et al., 1999; Park & Holzman, 1992). One recent investigation, however, concluded that working memory is intact in euthymic patients after accounting for the effects of sustained attention (Harmer et al., 2002). It is conceivable that manic patients may also have relatively normal working memory processes, but this factor has not been measured after accounting for other potential confounding variables, such as the ability to attend to the tasks. An additional observation is that no study has examined executive functioning in both manic and euthymic patients; therefore, it is unclear whether cognitive deficits are present solely during symptomatic periods, or whether some deficits may persist during times of euthymia and represent a trait in these patients.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate working memory and inhibitory control in different mood states in groups of patients with bipolar disorder. We predicted that both euthymic and manic patients with bipolar disorder would perform similarly to healthy participants on the Delayed Response Task. As behavioral dyscontrol is the clinical hallmark of mania, we posited that the largest magnitude of difference between manic and euthymic patients would emerge on tests that required behavioral regulation. Therefore, we predicted that manic patients would perform more poorly than euthymic patients and healthy participants on the Object Alternation Task.

METHODS

Participants

Three groups of participants were recruited for this study: 15 patients (7 women, 8 men) with bipolar disorder who were hospitalized for a manic episode; 18 patients (8 women, 10 men) with bipolar disorder who were euthymic at the time of recruitment; and 18 healthy participants (6 women, 12 men) from the local community.

Patients with mania were recruited from the inpatient psychiatric units of the University of Cincinnati Hospital. These participants were recruited based on the following criteria: (1) hospitalization for a bipolar manic episode defined by DSM–IV criteria; (2) age 17 to 45 years; (3) ability to communicate in English, and; (4) provision of informed consent. Patients were excluded for (1) acute medical illness (delirium) as determined by medical evaluation and rapid symptom resolution; (2) drug or alcohol abuse or dependence within the previous three months (DSM–IV criteria); (3) acute intoxication or withdrawal from drugs or alcohol; (4) history of a neurological disorder or loss of consciousness due to head injury; and (5) documented IQ below 75, or history of significant learning disorder (e.g., documented verbal or nonverbal learning disability).

Patients with bipolar disorder who were euthymic were recruited from an ongoing study of outcome following first-episode mania (Strakowski et al., 1999). Patients participating in this study return to the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine every 4 months for follow up interviews, and it was during or soon after these visits that participants were enrolled in the present study. The design of the current study is cross sectional; therefore, no patient tested when manic was retested when euthymic.

Euthymic patients were required to have had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type I, as verified by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID-P) (Spitzer et al., 1995). To determine if the participants in the study were clinically stable, the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation was completed to assess symptomatic recovery (Strakowski et al., 1998). Patients who received scores that ranged from 1 (no symptoms) to 3 (no DSM–IV syndrome criterion item scored greater than “mild”) for the past consecutive 8 weeks were considered to be “stable” and were included in the study. These criteria are based on the syndromic recovery criteria from the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study (Shapiro & Keller, 1981; Strakowski et al., 1999). Other than symptoms at the time of testing, euthymic patients were selected according to the same inclusion/exclusion criteria as the manic patients.

The same criteria that were used to enroll patients with bipolar disorder were applied to healthy participants, except that healthy participants were free of Axis I disorders, had no family history of mood or psychotic disorder, and had no previous exposure to psychiatric medication. Healthy participants were group matched to the patients with respect to age, education, and sex. These participants were recruited by word of mouth, by contacting healthy participants who had participated in previous research studies, and by newspaper advertisement.

Diagnostic and Symptom Evaluation

Diagnoses for all participants were confirmed or ruled out with the SCID-P. This instrument was administered by psychiatrists or post-doctoral fellows who had established high inter-rater reliability (kappa > .90). Measures given to all participants prior to neuropsychological testing included the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978), Hamilton Depression Inventory (HAM-D) (Hamilton, 1960), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1982).

All participants were assessed for lifetime substance abuse and dependence and for use in the month prior to screening using the SCID-P and the Alcohol and Drug use portions of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McClellan et al., 1980). Toxicology screens were conducted as part of the routine inpatient admission evaluation and were used to corroborate information obtained through the structured interview. Toxicology screens were not obtained for euthymic patients or healthy participants. With respect to medication treatment, 11 manic patients and 13 euthymic patients were receiving some form of mood stabilizing medication at the time of testing.

Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained, followed by the diagnostic, substance abuse, neuropsychological, and symptom severity measures. To minimize the possibility of coercion while they were receiving treatment, no inpatient was paid a stipend for participating in this study; however, they were given the opportunity to earn money based on successful task performance as described below. Healthy participants and patients who were euthymic were paid a stipend for their time in this study, in addition to the money that they earned for successful task performance. This protocol was approved by the University of Cincinnati's Internal Review Board.

Neuropsychological Tests

Object Alternation Task (OA)

The OA was chosen as a more specific measure of inhibitory control than traditional clinical tests (Freedman, 1990), and is more sensitive to the cognitive rather than the motor aspects of inhibitory control. To successfully complete this task, participants must inhibit responses for which they have been rewarded previously. A modification of the Wisconsin General Test Apparatus was used for this study. We chose to create a testing apparatus that was similar to the original form employed in the experimental animal literature, rather than a computerized version, in order to keep stimuli as similar as possible to what has been used in the animal literature. Briefly, one-inch PVC piping was assembled to form a standing frame with internal dimensions of 61 cm wide and 53 cm high. A black curtain was attached to the top of this frame that was raised and lowered by a pulley system controlled by the investigator.

For this task, two three-dimensional objects covered two black wells. Each object had a unique shape and color: one was a green cylinder and the other was a red triple octahedron. Both objects were mounted atop a black square plaque (7.6 × 7.6 × 2 cm). The curtain was placed between the investigator and the participant such that the participant could see neither the stimuli nor the investigator.

For each trial, the curtain was partially raised, allowing the participant to see the stimuli and the hands of the investigator (Oscar-Berman, 1991). The participant's task was to learn under which of the objects a nickel was hidden. The curtain was lowered before each trial. On the first trial, both objects were baited with nickels. On the second trial, the nickel was placed under the object not chosen on the preceding trial. The objects were placed next to each other, to the left and right of the center of the curtain. After each correct response, the nickel was moved beneath the object that was previously not baited. Placement of each object to the left or right of the participants was predetermined based on a modified random schedule (Gellerman, 1933).

Participants were considered to have learned the alternation strategy if they achieved 12 consecutive correct responses, and the task was discontinued at that point. A correction procedure was used in which the nickel remained under the same object until the participant responded correctly (up to 10 trials). This aspect of the task administration provided a measure of perseverative responding. A maximum of 50 trials were administered if the participant failed to achieve the learning criterion. The participants kept the money that they earned through correct responses.

The dependent measure was the total number of perseverative errors. If a participant committed three errors in a row, the second such error was considered the first perseveration, and subsequent consecutive errors were scored as perseverative errors. Perseverative errors are thought to represent a rigid response style and difficulty inhibiting previously rewarded responses (Bardenhagen & Bowden, 1998).

Delayed Response Task (DR)

The Delayed Response Task is a measure of spatial working memory (Goldman & Rosvold, 1970). Deficits on the DR in monkeys are most severe following damage to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Oscar-Berman, 1975). This task has been recently modified for use with humans; however, the most common administration has frequently yielded ceiling effects (i.e., the healthy participants in some studies committed a mean number of errors equal to zero) (Brewer et al., 1996; Gansler et al., 1996; Levine et al., 1999). Therefore, a novel protocol was developed for the present study. As described below, this modification created a more difficult task by increasing the number of foils and including a distracter task to reduce rehearsal.

The DR used the same apparatus as the OA; however, for the DR, eight wells were arranged in a circular pattern, and nondescript square plaques covered each of the wells. A nickel was hidden under one of the plaques in view of the participant, and then the curtain was lowered. Participants were asked to remember the spatial location of the nickel across the delay intervals of 1 s, 5 s, 10 s, or 15 s, which were presented in random order.

During the delay intervals, the participants engaged in a visual-spatial distraction task to reduce the likelihood that they would employ rehearsal or other mnemonic techniques. The distraction task involved having the participants complete a number of permutations of the Trail Making Test, Part B. Participants were given the standard administration of the Trail Making Test immediately prior to the DR task, which served to introduce participants to the task. Participants then attempted to complete as many of the number-letter connections on the Trail Making Test as they could within each delay interval. The directions for the task were as follows:

“This is a test requiring you to complete two tasks at the same time. On the first task, I am going to hide a nickel under one of these covers. Your job will be to remember where the nickel was hidden. After I hide the nickel, I am going to hide the covers by lowering the curtain. After I lower the curtain, you will begin the second task by continuing to connect the numbers and letters on these sheets (i.e., Trail Making Test forms), just like you did on the previous test. Place your other hand on top of the piece of paper that you are working on, so that I can see both of your hands. (This request prevented participants from using their hands to “mark” the location of the target.) If you make a mistake, continue from where you realize your mistake, don't take time erasing. When you have completed one sheet, go on to the next one. Keep working until the curtain is raised. At that point you pick up the cover that was hiding the nickel. The placement of the nickel will not have changed. You get one chance to find the nickel, and you may keep any money that you earn.”

During the 1-s delay condition, the participants did not work on the distraction task; rather, the curtain was lowered and immediately raised. This condition was included to ensure that the participants were adequately attending to the material. All participants completed 40 trials of the DR, the same number of trials used on a similar DR task in a previous study (Brewer et al., 1996). The dependent variable was the total number of correct responses.

American National Adult Reading Test (Grober & Sliwinski, 1991)

This test was included as an estimate of premorbid intelligence. Participants were required to read a list of 50 words that were difficult to pronounce based on phonetic decoding. The number of words accurately pronounced on this task significantly correlates with overall intelligence (Spreen & Strauss, 1998).

Token Test (DeRenzi & Vignolo, 1962)

This test assesses verbal comprehension by requiring participants to attend to and execute simple tasks (Benton et al., 1994). A number of tokens were placed in front of the participant which varied by shape (circles and squares), size (small and large), and color (red, yellow, green, white, and black). The participants manipulated the tokens in response to verbal commands. This test was used to assess the participants' abilities to follow instructions.

Facial Recognition Test (Benton & Van Allen, 1968)

This test was developed to examine the ability to recognize faces independent of memory ability and is sensitive to deficits in visual perception. The participant's task was to identify target faces that were hidden among foils. This test was used to ensure that the participants could adequately encode visual spatial material. As both the Object Alternation and Delayed Response Tasks were dependent on the ability to remember the position of an object in space, adequate visual perceptual abilities were thought to be necessary for interpreting performance on the experimental measures.

Data Analysis

Healthy participants were group matched to patients with respect to sex, age, and education. To determine whether IQ, spatial perception, language comprehension, sex, age, race, or years of education were related to task performance, these factors were entered into one multivariate linear regression model, with OA and DR performance serving as the dependent variables. Any factors with p < .10 were judged to potentially have an influence on task performance and were selected as covariates in subsequent analyses to provide adjusted estimates of task performance. To evaluate the effects of disease severity, substance abuse, and medication, similar regression analyses were conducted with only the patient groups included.

To test the hypothesis that patients with mania had more difficulty with inhibitory control than with working memory, the number of perseverative errors from the OA and the number correct on the DR, respectively, were converted to Z scores based on the mean and standard deviation of the healthy participants. Perseverative errors on the OA were reverse scored to yield standardized values where higher Z scores indicated better performance, which enabled comparison with DR scores. The transformed values were entered into a repeated-measures ANCOVA with the following factors: group (control / euthymic / manic) and task (OA perseverative errors / DR number correct). Tukey correction was used for post-hoc analyses.

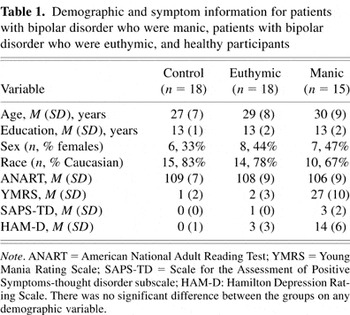

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, the groups were well matched on demographic variables including age, verbal IQ estimate, sex, race, and years of completed education. On average, the participants were young adults with intellectual abilities in the average range who had completed one year of college. There were similar proportions of males and females in each group. The groups did not differ significantly in their performance on the Token Test (a measure of verbal comprehension), the DR 1-s trials (a measure of immediate attention), or the facial recognition test (a measure of visuospatial perception). Group scores on these tasks can be found in Table 3.

Demographic and symptom information for patients with bipolar disorder who were manic, patients with bipolar disorder who were euthymic, and healthy participants

Disease Variables

Consistent with their affective state at the time of testing, manic patients had significantly higher symptom severity ratings than the euthymic patients on the YMRS, F(1,32) = 103, p < .01, the SAPS-TD (thought disorder subscale), F(1,32) = 44, p < .01, and the HAM-D, F(1,32) = 54, p < .01. Post-hoc tests revealed that euthymic patients and healthy participants did not differ on the symptom severity measures. Four manic patients were experiencing mixed mania at the time of testing. When variables related to illness severity were examined, the manic patients were found to have significantly more hospitalizations than euthymic patients, Z(29) = 3.1, p < .01. The patient groups, however, were similar for other disease factors, as shown in Table 2.

Descriptive information for disease variables

Group performances on cognitive tests

No healthy participant endorsed current or previous substance abuse or dependence. One manic and four euthymic patients endorsed histories of substance abuse. Three manic and five euthymic patients endorsed prior substance dependence. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to the number of patients taking medications.

Group Performances on Cognitive Tests

The main hypothesis of this study was examined by evaluating each group's performance on the DR and the OA. Raw data for these and the other cognitive tests are presented in Table 3. Prior to examining group performance on these tasks, multivariate regression analyses revealed that age, F(1,43) = 3.3, p < .08, and verbal IQ estimate, F(1,43) = 6.1, p < .02, were associated with task performance. Therefore, these factors were selected as covariates.

Variances were found to be heterogeneous across groups; therefore, an estimated unequal variance model was used to address our first hypothesis. A repeated-measures ANCOVA revealed a significant interaction between group and task, F(2,48) = 4.8, p < .02. Similar analysis conducted on raw test data also showed a significant interaction. Post-hoc testing on the standardized data showed that the manic, F(1,31) = 5.7, p < .02, and the euthymic, F(1,34) = 6.6, p < .02, patients performed significantly worse on the OA than on the DR. In addition, when compared with healthy participants, both the manic, t(48) = 3.4, p < .01, and the euthymic patients, t(48) = 2.2, p < .04, showed impaired performance on the OA, but their performance was similar to healthy participants on the DR. There was no significant difference between the patient groups on either the OA, t(48) = 1.6, p < .12, or the DR, t(48) = 0.9, p < .37. These data are illustrated in Figure 1.

Z-scores of means of group performances on the Object Alternation (OA) and Delayed Response (DR) Tasks. Bars represent standard error.

The manic patients took significantly more trials (M = 79, SD = 22) than healthy participants (M = 54, SD = 23) to complete the OA, F(1,31) = 10.4, p < .003. This finding raised the possibility that the manic patients may have committed more perseverative errors simply because they completed more trials. To address this possibility, manic patients and healthy participants were compared on the percent of perseverative responses. This analysis confirmed that a higher percentage of perseverative responses were committed by manic patients (M = 11%, SD = 7%) relative to controls (M = 6%, SD = 7%), F(1,31) = 4.3, p < .05.

Working Memory Performance Across Delay Intervals

Previous studies indicated that patients with mania might display steeper performance declines than healthy participants as working memory demands increase (Sweeney et al., 2000). One-way analyses of variance showed that the groups performed similarly on the 1-, 5-, and 10-s delay intervals. However, at the 15-s interval the manic patients performed significantly worse than the other groups, F(2,48) = 3.8, p < .03. Healthy participants and patients with bipolar disorder in remission performed similarly at this interval, F(1,34) = .05, p < .83. These data are illustrated in Figure 2.

Patients with mania displayed working memory deficit at the 15-s interval of the Delayed Response Task, while patients with bipolar disorder who were in remission performed similar to healthy participants at all delay intervals. Bars represent standard error.

Influence of Factors Related to Disease Course

In previous studies, longer and more severe courses of illness were found to be associated with poorer cognitive performance (Denicoff et al., 1999; Hoff et al., 1988; van Gorp et al., 1998). To determine whether a similar pattern existed in the present sample, associations were evaluated between cognitive performance and disease duration, age at disease onset, number of hospitalizations, and number of manic and depressed episodes. This issue was considered to be particularly important given that the patient groups differed significantly in the number of hospitalizations. As some patients had suffered many more depressive and manic episodes than others, Spearman correlations were used to evaluate the relationships between these variables and cognitive performance. The normal effects of aging are known to include a reduction in some executive abilities (Albert et al., 1990). Age, therefore, was controlled during calculation of partial correlations. These results indicated that earlier age at onset was associated with poorer OA performance, r(33) = .41, p < .02. No other significant association was detected.

Effects of Substance Abuse and Medication

Presence or absence of past substance abuse and dependence were dummy coded and entered into a multivariate regression equation. Neither prior history of substance abuse, F(1,45) = .2, p < .7, nor dependence, F(1,45) = .1, p < .9, was significantly related to task performance. Likewise, the cognitive effects of treatment with lithium, antipsychotic, antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and benzodiazepine medications were evaluated with multivariate regression. No medication was found to significantly relate to task performance.

Contribution of Symptom Severity to Cognitive Performance

There was no significant correlation between mania or psychosis severity and OA or DR performance. Severity of depressive symptoms correlated significantly with OA perseverative errors, r(33) = .37, p < .04. Patients with mixed mania have depressive symptoms that co-occur with manic symptoms; however, in our sample there was no significant difference between the manic (M = 12.6, SD = 5.0) and mixed (M = 18, SD = 6.6) patients with respect to HAM-D scores, Z (15) = 1.6, p < .12.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with our hypotheses, patients with mania performed significantly worse on the Object Alternation Task, a task requiring inhibitory control, than on the Delayed Response Task, a task of visual working memory. Contrary to expectations, however, euthymic patients also displayed impaired performance on the Object Alternation, but not on the Delayed Response Task. Component executive abilities, therefore, were found to be dissociable across groups, and suggested that impaired inhibitory control processes may persist during normal mood states. These results did not appear to be attributable to comprehension or visuospatial deficits or an inability of the patients to attend to and encode visual information, as they performed normally on measures of each of these constructs. It was found, however, that depression symptom severity was significantly correlated with Object Alternation Task performance, revealing a potential relationship between mood factors and inhibitory control.

On the Delayed Response Task, manic and euthymic patients performed similarly to controls when overall task score was considered. Post-hoc analyses revealed that all groups performed similarly at the shorter delay intervals; however, at the 15-s interval, the manic patients' performance was significantly below that of the euthymic patients and healthy participants. This finding suggested that the manic patients' deficits became more apparent as working memory demands increased. A similar finding has been reported in one other study (Sweeney et al., 2000).

Previous reviews have alluded to methodological deficiencies that plague interpretation of many studies of bipolar disorder (Chowdhury et al., 2003). For example, it has been suggested that poor cognitive performance by manic patients may be due to nonspecific factors such as low motivation, distraction, or generalized cognitive impairment (Murphy et al., 1999). Impaired Object Alternation performance but normal performance on the Facial Recognition Test and the Token Test argues against any generalized dysfunction in this patient group. Psychiatric medications and substances of abuse have also been found to influence executive ability in patients with bipolar disorder (van Gorp et al., 1998); however, no medication or recreational drug was found to be significantly related to test performance in the present study.

Participants may have failed the Object Alternation Task because of impaired executive abilities that were unrelated to inhibitory control. For example, working memory impairment may have led to perseverative responding if the participants failed to remember trial-to-trial information, and relied instead on the same strategy that they used at the beginning of the task (Oscar-Berman, 1991). However, the Object Alternation Task employed a delay interval of approximately 5 s, a range that was shown to be within the capabilities of the manic patients based on the Delayed Response data. The euthymic patients also performed poorly on the Object Alternation Task, but they showed no difference from healthy participants on even the longest delay intervals of the Delayed Response Task. This finding is consistent with a recent finding of intact working memory in a group of euthymic bipolar patients (Harmer et al., 2002). Therefore, it is difficult to attribute the patients' poor performance on the Object Alternation Task to working memory dysfunction. Impaired problem solving ability might also lead to impaired performance on the OA. If this were the case, the patient groups would be expected to have difficulty initially formulating a problem solving strategy, and produce a pattern of responses that is more random in nature. However, patients in the present study showed increased perseveration, suggesting that they were able to select a problem-solving approach to the task, but had difficulty subsequently altering that strategy.

Taken together, it appears that the number of perseverative errors committed by the patients on the Object Alternation Task may be related to impaired inhibitory control mechanisms. Other reports of impaired performance by bipolar patients on tests of inhibitory control support the role of inhibitory dyscontrol in this population (Murphy et al., 1999). For example, one study evaluated a group of bipolar patients when they were manic and again 4 weeks later as outpatients, after their clinical status had improved (McGrath et al., 1997). At both time points these patients performed poorly on the Stroop Color-Word Test, a verbally mediated test that required the ability to inhibit an initial speech–response impulse. Similarly, these patients continued to show an abnormally high number of perseverative responses on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, another measure of inhibitory control, despite significant improvement on aspects of this test (i.e., categories achieved) that involve other executive abilities. Further supporting inhibitory dyscontrol in euthymic patients is one study where patients with bipolar disorder endorsed significantly greater inter-episode impulsivity on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale than healthy participants (Swann et al., 2001). This information, along with cognitive data, provides converging evidence to support a deficit that persists across mood states in the cognitive aspects of inhibitory dyscontrol in patients with bipolar disorder.

The Object Alternation Task has been shown to be relatively specific to damage in the ventral areas of the frontal lobes in primates, most notably the orbitofrontal cortex (Oscar-Berman, 1975), while the Delayed Response Task has been shown to be sensitive to lesions in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Oscar-Berman, 1975). Both manic and euthymic patients performed significantly worse on the Object Alternation as compared to the Delayed Response Task; therefore, dysfunction in the orbitofrontal cortex may be one explanation for this deficit. Supporting this possibility is one recent study that used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine inhibitory control in bipolar patients who were experiencing elevated, depressed, or euthymic mood states (Blumberg et al., 2003). Signal changes associated with specific mood states were detected in areas of the ventral prefrontal cortex, of which orbitofrontal cortex is a part; however, there were aspects of the left ventral prefrontal cortex that revealed attenuated signal in all groups of bipolar patients (i.e., independent of mood state). Thus, the current findings are consistent with imaging data in suggesting that the orbitofrontal cortex may play a role in the expression of bipolar disorder.

A contribution from orbitofrontal cortex may be one explanation for the findings presented, but mood-related factors also appear to be important. When the relationships between symptom severity and cognitive performance were considered, we found no significant correlation between cognitive performance and either mania or psychosis severity. However, worse performance on the Object Alternation Task was found to correlate significantly with greater depression severity. These findings are consistent with previous studies that reported a significant relationship between tests of executive function and level of depression in euthymic patients (Ferrier et al., 1999; Martinez-Aran et al., 2000; van Gorp et al., 1998). Further analyses of our data revealed that manic patients had significantly greater elevation on the HDRS than either healthy controls or euthymic patients, whom did not differ from each other. The relationship between OA performance and depression rating is not likely attributable to patients with mixed mania in the present study, as mixed and pure mania patients did not differ on their HDRS ratings. The nature or significance of the relationship between depression severity and inhibitory control is unclear. It is possible that, during depression, a fundamental deficit in inhibitory control manifests as overinhibition rather than impulsivity. Studies examining patients with bipolar disorder across all mood states will be needed further explore this hypothesis.

There is increasing consensus that earlier age of onset of bipolar disorder is associated with poorer cognitive performance (Denicoff et al., 1999; van Gorp et al., 1998) and clinical outcome (Meeks, 1999). In the present study, we found that age at onset was positively correlated with performance on the Object Alternation but not the Delayed Response Task. It follows that severity of inhibitory dyscontrol may partly account for the worse outcome in patients with early onset of the disorder. Studies employing larger sample sizes will need to confirm these ideas.

This study was limited by the majority of manic and euthymic patients receiving psychotropic medication at the time of testing. As previously discussed, we found no relationship between medication treatment and cognitive performance, but it is difficult to completely rule out the potential effects of this factor. It is likely that patients with bipolar disorder have other impairments than were measured in this study and future studies may place our findings in the context of other cognitive dysfunction. It was found that the manic patients had greater number of hospitalizations than the euthymic patients and, therefore, may have had more treatment-resistant illnesses. Future studies using longitudinal design may avoid this and other group specific factors in our study. Depressed bipolar patients were not included in the present study. Consequently, it is difficult to speculate whether the pattern of performance of euthymic and manic patients will generalize across all mood states associated with bipolar disorder. Future studies may include depressed bipolar patients and expand the inquiry into the nature of executive functioning into this serious psychiatric disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by MH58170. The authors thank Jennifer Ret and Wendi Wigh for their assistance with aspects of this project.

References

REFERENCES

Demographic and symptom information for patients with bipolar disorder who were manic, patients with bipolar disorder who were euthymic, and healthy participants

Descriptive information for disease variables

Group performances on cognitive tests

Z-scores of means of group performances on the Object Alternation (OA) and Delayed Response (DR) Tasks. Bars represent standard error.

Patients with mania displayed working memory deficit at the 15-s interval of the Delayed Response Task, while patients with bipolar disorder who were in remission performed similar to healthy participants at all delay intervals. Bars represent standard error.

- 61

- Cited by