Introduction

The septal nuclei in the basal forebrain constitute an interface between limbic medial temporal brain structures (hippocampus and amygdala) associated with cognition and motivation and hypothalamic and brainstem regions related to endocrine and autonomic functions (Colom & Garrido-Sanabria, Reference Colom and Garrido-Sanabria2007). The medial septal nuclei (medial septum and diagonal band of Broca) provide the major cholinergic input to the hippocampus (Colom & Garrido-Sanabria, Reference Colom and Garrido-Sanabria2007; Mesulam, Mufson, Wainer, & Levey, Reference Mesulam, Mufson, Wainer and Levey1983) and drive hippocampal theta oscillations involved in memory encoding (Huerta & Lisman, Reference Huerta and Lisman1993). Although once thought to be vestigial in humans, the septal region (septum verum or precommissural septum) contains well developed nuclei, including the ventrolateral, dorsolateral, intermediolateral, septofimbrial, and medially, the medial septal-vertical limb of the diagonal band nuclei (Mai, Assheuer, & Paxinos, Reference Mai, Assheuer and Paxinos2004). Septal lesions in humans impair memory; however, such lesions also typically involve neighboring orbitofrontal regions (Alexander & Freedman, Reference Alexander and Freedman1984; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Okuda, Tsukiura, Ohtake, Miura, Fukatsu and Yamadori2002) leaving the role of human septal nuclei uncertain. A small number of neuroimaging studies suggest a role for basal forebrain including the septal region, in episodic memory (Caplan, McIntosh, & De Rosa, Reference Caplan, McIntosh and De Rosa2007; De Rosa, Desmond, Anderson, Pfefferbaum, & Sullivan, Reference De Rosa, Desmond, Anderson, Pfefferbaum and Sullivan2004; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Okuda, Tsukiura, Ohtake, Miura, Fukatsu and Yamadori2002; Jernigan, Ostergaard, & Fennema-Notestine, Reference Jernigan, Ostergaard and Fennema-Notestine2001). This paucity of reports of septal involvement in human memory may relate to the fact that septal nuclei are not included in standard neuroanatomical macroscopic parcellation schemes commonly used in neuroimaging studies.

Recently, probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps of cholinergic basal forebrain cell groups, including septal nuclei, have been developed by combining histological and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from 10 deceased human subjects (Zaborszky et al., Reference Zaborszky, Hoemke, Mohlberg, Schleicher, Amunts and Zilles2008). We used these maps to measure septal forebrain volume in a group of healthy subjects, and to determine if septal volume could predict measures of recognition memory accuracy as assessed using the California Verbal Learning Test Second Edition (CVLT-II) (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan & Ober, Reference Delis, Kramer, Kaplan and Ober2000). For discriminant validity, we looked at whether septal volume predicted performance in a cognitive domain not expected to involve septal nuclei: visual confrontation naming ability. In an exploratory analysis, we examined whether the volume of any other cortical or subcortical brain structures predicted recognition memory.

Method

Subjects

Twenty-five right-handed participants (11 female; mean age 41.1 years; range, 21–62 years; std: 11.4 years]; mean years of education 13.2 years; range, 8–20 years; std: 3.1 years) were recruited through online advertisement for this study, which was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Subjects denied medical, neurologic, or psychiatric illness. Participants full-scale IQs ranged from 84 to 143 (mean: 110.5; std: 17.9).

Assessment

The CVLT-II was administered as part of a neuropsychological test battery. The CVLT-II provides a detailed assessment of verbal learning and memory. Examinees are read a list of words (List A) multiple times, and asked to recall them across a series of learning trials. A second list of words (List B), read once to participants, provides a means to measure interference. Retention and free recall is tested after a brief (5-min) and long (20-min) delay, followed by a yes/no recognition test for the 16 original List A target words and 32 distracters (consisting of 16 List B distractors and 16 novel distracters). For this study, we focused on the Total Recognition Discriminability Index (TRDI) as a measure of overall recognition memory accuracy. The TRDI takes into account correct hits and false-positive responses (for both List B and novel distractors), and is noted in the CVLT-II manual to be the “single best measure of overall recognition performance.” In addition, we looked at two related but more specific indices: Source Recognition Discriminability (SRDI) and Novel Recognition Discriminability (NRDI). SRDI measures a subject's ability to endorse the 16 list A target items and reject the 16 distractor items from List B. Patients with deficits primarily in remembering the context or source of verbal information will often attain poor SRDI scores. NRDI measures a subject's ability to endorse the 16 target items and reject the 16 novel distractors that are not found on either List A or List B.

The Boston Naming Test (BNT; Kaplan, Goodglass, & Weintraub, Reference Kaplan, Goodglass and Weintraub1983) was also administered. This task requires subjects to name a series of objects depicted as two-dimensional line drawings.

MRI Scanning and Initial Image Processing

Imaging was performed at the NYU Center for Brain Imaging on a 3 T Siemens Allegra head-only MR scanner. Image acquisitions included a conventional 3-plane localizer and two T1-weighted volumes (echo time = 3.25 ms; repetition time = 2530 ms; inversion time = 1.100 ms; flip angle = 7 deg; field of view (field of view) = 256 mm; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1.33 mm). Images were automatically corrected for spatial distortion due to gradient nonlinearity and B1 field inhomogeneity using Freesurfer auto reconstruction (Freesurfer 5.0; http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). Further image analysis used SPM (SPM8, Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging) and FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu).

Measurement of Septal Nuclei Volume

Using SPM, individual scans were normalized to the MNI152 T1-template using a 12-parameter affine transformation and partitioned into gray and white matter using a unified segmentation approach. Gray and white matter maps were registered to the segmented MNI152 T1-template using the DARTEL toolbox, an efficient large deformation diffeomorphic framework which provides information about voxel-level local expansion and contraction necessary to deform the image to match the template (Ashburner, Reference Ashburner2007). The DARTEL flow fields derived from this registration were applied to a binary mask of the septal nuclei (generated as described below). To warp the septal nuclei maps, which were in MNI template space, back to each individual subject's native space, we applied the inverse DARTEL flow field. We then calculated the volume of each subject's septal nuclei mask in mm3.

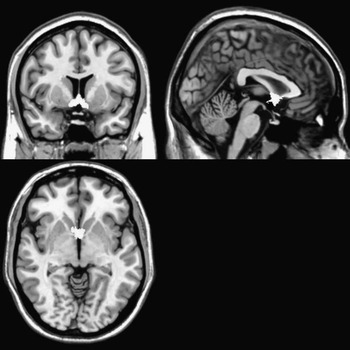

The binary septal nuclei masks we used (Figure 1) were based on probabilistic basal forebrain maps generated using digital images of cell-stained histological sections from 10 human postmortem brains which were reconstructed in three dimensions using the MRI scans of the fixed brain as a shape reference, then spatially normalized to the single-subject T1-weighted MNI reference brain, as described in detail elsewhere (Zaborszky et al., Reference Zaborszky, Hoemke, Mohlberg, Schleicher, Amunts and Zilles2008). The binary septal nuclei masks included all voxels showing ≥ 10% probability of being part of the medial septal nucleus or the nucleus of the diagonal band of Broca (Zaborszky et al., Reference Zaborszky, Hoemke, Mohlberg, Schleicher, Amunts and Zilles2008).

Fig. 1 Bilateral septal nuclei mask derived from Zaborszky et al. (Reference Zaborszky, Hoemke, Mohlberg, Schleicher, Amunts and Zilles2008) displayed on T1 magnetic resonance imaging template.

Measurement of Volume of Other Brain Regions

Freesurfer was used to calculate volumes of structures other than septal nuclei. The two T1-weighted images were rigid body registered to each other and reoriented into a common space, registered, and averaged to improve signal-to-noise. Automated cortical and subcortical segmentation was performed based on image intensity and by assigning a neuroanatomical label to each voxel based on a manually labeled training set and Bayesian prior information. Labeling was performed by rigid-body alignment of each subject's brain to the probabilistic atlas, followed by non-linear morphing to the atlas. Labels were generated based on the prior probability of a given tissue class occurring at a specific atlas location, the likelihood of the image intensity given that tissue class, and the probability of the local spatial configuration of labels given the tissue class. Volumes in mm3 of all cortical and subcortical structures (n = 40 for each hemisphere; see supplemental table for list of structures) as well as a measure of total intracranial volume (TICV) were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Using SPSS, we performed separate linear regressions using each bilateral brain region (septal forebrain and, in exploratory analyses, each of the 40 Freesurfer-derived regions) as independent variables, and either TRDI or BNT score as the dependent variable, while controlling for age and TICV. Results were considered significant at p < .05 for a priori regions of interest (septal forebrain) and p < .0001 for non-hypothesized regions. To determine whether brain regions that were significant predictors of overall recognition memory (TRDI) predicted particular recognition memory subtypes, significant TRDI predictors were further assessed using both SRDI and NRDI as the dependent variable. Significant TRDI predictors were also assessed for potential laterality effects.

Results

Bilateral septal forebrain volume was a positive predictor of TRDI accuracy (β = 0.921; t = 2.2; p = .039). Results remained significant when the analysis was performed using either left or right septal nuclei volume (left: β = 0.828; t = 2.09; p = 0.049; right: β = 0.926; t = 2.17; p = .042) indicating no laterality effects. Results remained significant when SRDI but not NRDI was used as the dependent variable (SRDI: β = −0.381.06; t = 2.56; p = .018; NRDI: β = .767; t = 1.65; p = .11) indicating that septal forebrain volume predicted only source discrimination (not novel discrimination) memory. Results were similar when additional covariates (years of education, IQ) were included in the model. See Figure 2 for plots of memory test scores as a function of septal forebrain volume.

Fig. 2 Partial regression plots of standardized residuals and regression lines of memory test scores as a function of septal forebrain volume. Plots reflect multivariate relations between total (right and left) septal forebrain volume and (a) Total recognition discriminability (TRDI; ratio of correct hits to false positives), R 2 = 0.187*; (b) Source recognition discriminability (SRDI; ratio of correct hits to List B false positives), R 2 = 0.237*; and (c) Novel recognition discriminability (NRDI; ratio of correct hits to novel false positives), R 2 = 0.115*; with the variance accounted for by other independent variables in the models (age, intracranial volume) removed. *Significant at P < .05.

Supporting discriminant validity, total septal volume did not predict naming ability (β = .004; t = 0.339; p = .738). Of the 40 other brain regions examined, none were significant predictors of TRDI. See Supplemental Table for CVLT-II and BNT raw scores.

Discussion

Septal Forebrain

A relationship between septal forebrain volume and recognition memory accuracy—but not naming ability—supports a specific role for septal forebrain in human episodic memory. More specifically, septal forebrain volume was associated with SRDI, a measure of source memory, but not NRDI, which measures the more basic ability to discriminate new from old items, without requiring knowledge of the context in which those old items were presented. This distinction between memory for content and memory for source/context has been recognized for decades (reviewed in Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, Reference Johnson, Hashtroudi and Lindsay1993). While memory for content is known to depend critically upon the hippocampus, the neural basis for source/context memory is less understood. In accord with our current finding of an association between septal forebrain volume and source memory, patients with basal forebrain lesions have been shown to demonstrate specific deficits in source memory, although these deficits may also relate in part to accompanying frontal lobe lesions (Alexander & Freedman, Reference Alexander and Freedman1984; Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Okuda, Tsukiura, Ohtake, Miura, Fukatsu and Yamadori2002). Several functional neuroimaging studies found specific activation of basal forebrain in the region of the septal nuclei when subjects performed tasks requiring memory for source/context, including recall of items based on temporal cues (Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Okuda, Tsukiura, Ohtake, Miura, Fukatsu and Yamadori2002) and resolution of the interference between newly learned information and prior memories (Caplan et al., Reference Caplan, McIntosh and De Rosa2007; De Rosa et al., Reference De Rosa, Desmond, Anderson, Pfefferbaum and Sullivan2004). Our findings complement and extend these prior lesion and functional neuroimaging studies by providing greater anatomic specificity (through use of a newly-developed probabilistic histology-based atlas of human septal nuclei) and functional specificity (through use of validated CVLT-II indices of memory subtypes), demonstrating, for the first time, a specific role for septal forebrain in human source memory.

Our finding of a positive relationship between septal volumes and recognition memory accuracy is consistent with a prior study showing that volume of another basal forebrain structure—nucleus accumbens—was independently associated with recognition memory in a mixed population of subjects with and without memory problems (Jernigan et al., Reference Jernigan, Ostergaard and Fennema-Notestine2001). In that study, basal forebrain atrophy in patients with Alzheimer's Disease (Grothe et al., Reference Grothe, Zaborszky, Atienza, Gil-Neciga, Rodriguez-Romero, Teipel and Cantero2010) likely contributed to results. Because our study included only healthy, relatively young subjects, disease-related degeneration would be expected to play less of a role. Rather, our results of enhanced recognition memory in subjects with larger septal nuclei are in accord with an increasing number of studies demonstrating better cognitive performance in association with larger brain regions in healthy controls (Kanai & Rees, Reference Kanai and Rees2011). However, the directionality of this relationship remains unclear. Although there is evidence that gray matter increases are associated with learning/practice in specific domains (Draganski et al., Reference Draganski, Gaser, Kempermann, Kuhn, Winkler, Buchel and May2006), it is also possible that early structural differences may potentiate more efficient learning and memory performance. Furthermore, complexities in regional structure/function relationships with respect to age and disease (Van Petten, Reference Van Petten2004) suggest that bigger is not always better, and this may account for the absence of a relationship between hippocampal volume and TRDI (or SRDI or NRDI) in the current study, despite the established role of the hippocampus in memory.

This study is limited by its reliance upon the SRDI of the CVLT-II as the only measure of source memory. SRDI is confounded by levels of memory given that List A is repeated five times and List B only once. However, there are currently limited neuropsychological tools for assessing source memory in clinical populations (Fine et al., Reference Fine, Delis, Wetter, Jacobson, Hamilton, Peavy and Salmon2008). Future studies should use a more precise measure of source memory in which learning exposure is equated, and only information source is varied. Furthermore, our analyses were limited by relatively small variation in scores on the discriminability tasks. This likely increased the probability of Type 2 errors, rendering caution in the interpretation of null findings. Given the limited range in SRDI scores, the presence of a significant relationship between septal forebrain volumes and SRDI is striking and worthy of further exploration.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a specific relation between septal forebrain volume and source memory accuracy in healthy humans. Results calls attention to this understudied brain region, which likely plays a role in memory and other impairments associated with human diseases including epilepsy, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's disease (Grothe et al., Reference Grothe, Zaborszky, Atienza, Gil-Neciga, Rodriguez-Romero, Teipel and Cantero2010; Heath, Reference Heath2005).

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants NS018741, NS023945 and NS057579 and faces (Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures). No authors have any financial disclosures. Drs. Butler and Blackmon contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Material

To review these additional data and analyses, please access the online-only Supplementary Table 1. Please visit journals.cambridge.org/INS, then click on the link “Supplementary Materials” at this article.