INTRODUCTION

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can lead to declines in cognitive functioning over time. In a meta-analysis of the neuropsychological (NP) sequelae of HIV infection (Reger, Welsh, Razani, Martin, & Boone Reference Reger, Welsh, Razani, Martin and Boone2002), cognitive deficits were detected at each stage of HIV disease progression, particularly in the later stages of illness (e.g., AIDS). Compared to seronegative controls, persons with symptomatic HIV showed significant problems in ten cognitive domains, especially motor function, executive function, information processing speed, and language. Persons with AIDS showed even more significant declines, most notably in motor function, executive function, information processing speed, immediate visual memory, and visual construction. In another meta-analysis (Cysique, Maruff, & Brew, Reference Cysique, Maruff and Brew2006), individuals with symptomatic HIV demonstrated mild global cognitive impairment, whereas individuals with AIDS demonstrated moderate global cognitive impairment, particularly in attention, psychomotor speed, learning, motor coordination, verbal memory, and reasoning.

Cognitive deficits are frequently associated with declines in everyday functioning because these activities require multiple cognitive skills. For instance, poor NP performance has been associated with deficits in self-care, independent living, and academic achievement (Heaton & Pendleton, Reference Heaton and Pendleton1981), and impairment in medication management, finances, cooking, and shopping (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; Mindt et al., Reference Mindt, Cherner, Marcotte, Moore, Bentley, Esquivel, Lopez, Grant and Heaton2003).

Effective vocational performance also requires the use of cognitive skills, and cognitive deficits have been associated with diminished vocational functioning. NP-impaired adults with HIV are more likely to be unemployed compared to NP-normal adults with HIV (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Marder, Dooneief, Bell, Sano, Todak and Stern1995; Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Velin, McCutchan, Gulevich, Atkinson and Wallace1994, Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; Kalechstein, Newton, & van Gorp, Reference Kalechstein, Newton and van Gorp2003; van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney, & Rabkin, Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999). They are also more likely to perform poorly on standardized work samples of job-related skills (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, White, Ross, Meredith and Taylor1996, Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004), to show decreases in worker qualification profiles (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, White, Ross, Meredith and Taylor1996), and to work fewer hours than their NP-normal peers (Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, van Gorp, & Lin, Reference Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, van Gorp and Lin2004).

To investigate the predictive relationship between cognitive and vocational functioning in adults with HIV who were seeking to reenter the workforce, we enrolled 174 individuals with HIV in a prospective workforce-reentry study. We administered a battery of NP tests assessing nine cognitive domains and followed participants for 24 months to monitor their progress toward employment. This approach conferred advantages over previous studies. First, it is a prospective study of individuals likely to attend vocational rehabilitation programs. Most earlier studies (e.g., Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Velin, McCutchan, Gulevich, Atkinson and Wallace1994; Rabkin et al., Reference Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, van Gorp and Lin2004) followed participants who were enrolled in natural history studies of HIV progression but were not necessarily seeking workforce reentry, and used cross-sectional designs (e.g., Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999). One longitudinal study of NP performance and employment was recently published (van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Rabkin, Ferrando, Mintz, Ryan, Borkowski and McElhiney2007); it employed a design similar to this study. Second, we also examined volunteer work and job training activities, important employment-related outcome variables that previous studies have not considered. The path toward employment can be complicated for people with HIV, and may be a progression that includes volunteer work, formalized training, and employment. Thus, we believed it was essential to include these as indicators of progress toward employment.

We hypothesized that NP functioning would predict employment-related activities over a two-year period. We approached this question from two analytic perspectives. From the first perspective, employment-related activities were expected to increase in frequency before full-time employment was obtained, and IQ and NP functioning were expected to positively predict involvement in volunteering, job training, and employment. From the second perspective, we conceptualized volunteering/job training and part-time employment as steps toward returning to work full-time. We expected IQ and NP performance to positively predict participants’ steps toward employment at their final study visit.

METHOD

Participants

This study used data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effectiveness of a vocational rehabilitation intervention designed to help HIV-infected adults return to work. The intervention results will be reported elsewhere. All participants were HIV-positive, were receiving disability payments, and were contemplating reentering the workforce. They were recruited through presentations to staff at community agencies and HIV medical providers throughout Los Angeles County. Participants were also recruited directly through presentations at community forums and programs for HIV-positive adults, and through advertisements in publications.

Participants completed an initial telephone screening to determine whether they were HIV-positive; were receiving medical care for HIV; were receiving disability payments; had stable housing for at least two months; and received less than $24,000 per year in private disability income. We imposed the private disability income restriction because we judged the risk of harm (i.e., permanent loss of disability income) from study participation to outweigh any potential benefits for these individuals.

Participants meeting the five inclusion criteria were invited for an in-person screening to determine if they had a current, untreated mental health problem; a current, untreated substance use problem; or significant impairment in cognitive functioning. Mental health and substance use problems were detected through structured interview questions based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1995) and assessed for symptoms of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and substance abuse and dependence. Participants were excluded from the study if they met criteria for one or more disorders over the previous 30 days and were not receiving treatment. These limitations were imposed because their presence might confound the analysis of the intervention’s effectiveness.

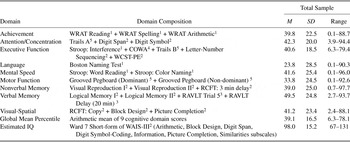

Table 1 presents the tests used in the NP screening and mean percentile ranks for each domain. These domains were selected based on studies suggesting they were the strongest NP predictors of employment (Kalechstein et al., Reference Kalechstein, Newton and van Gorp2003; Wen, Boone, & Kim, Reference Wen, Boone and Kim2006). Participants were excluded because of cognitive impairment if they scored in the impaired range (i.e., at or below the first percentile when compared with a relevant normative sample) on at least four of the seven tests of verbal and nonverbal memory; they scored in the impaired range on at least three of the five tests of executive functioning; or their full scale IQ score on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test-III (WAIS-III) was in the mental retardation range (i.e., < 70), and they reported no history of past employment. These criteria were chosen in order to allow participants with a broad range of cognitive abilities to enter the study, and to exclude only those who scored in the impaired range on more than half of the tests per domain in either executive functioning or verbal and nonverbal memory, or those who scored in the mental retardation range and did not have any employment history. This was consistent with our desire to represent as closely as possible the population of people with HIV who are actively seeking employment and are most likely to present for services at vocational rehabilitation programs.

Table 1. Composition and descriptive statistics for neuropsychological (NP) functional domain scores

Note

N = 174. All domain scores are mean percentiles except for the Estimated IQ scores. The references are the norms used to standardize scores on each test. WAIS-III subscales (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997a): Arithmetic, Block Design, Digit Span, Digit Symbol, Information, Letter-Number Sequencing, Picture Completion, and Similarities. Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd edition subscales (WMS-III; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997b): Logical Memory I and II and Visual Reproduction I and II. Boston Naming Test (Farmer, Reference Farmer1990); COWA = Controlled Oral Word Association Test (Ruff et al., Reference Ruff, Light, Parker and Levin1996); Grooved Pegboard = Grooved Pegboard (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein1985); RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Geffen et al., Reference Geffen, Moar, O’Hanlon, Clark and Geffen1990); RCFT = Rey Complex Figure Test (Miller, Reference Miller, Mitrushina, Boone, Razani and D’Elia2003); Stroop (Demick & Harkins, Reference Demick and Harkins1997); Trails A & B = Trail Making Test (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein1985); WRAT = Wide Range Achievement Test, 3rd edition (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1993); WCST-PE = 64-card Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, perseverative errors (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay and Curtiss1983).

1 Age corrected norms.

2 Age and education corrected norms.

3 Age and gender corrected norms.

4 Education and gender corrected norms.

5 Age, education, and gender corrected norms.

The in-person screenings were conducted by a neuropsychologist or by master’s level research assistants. The research assistants received approximately six hours of supervised training on administration of the screening instrument and NP tests. The neuropsychologist observed all research assistants conduct a mock screening and at least one screening with a potential participant.

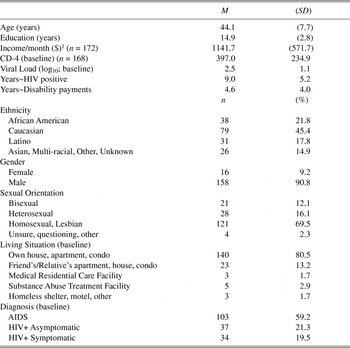

Two hundred thirty-eight participants completed the in-person screening. Of these 238 participants, 39 (16.4%) were excluded: 8 because of NP impairment; 6 because of NP plus untreated mental health or substance use problems; 12 because of untreated mental health problems; 10 because of untreated substance use problems; and 3 because of untreated mental health plus substance use problems. Another 25 participants (10.5%) were eligible for the study but declined to participate. Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the 174 remaining participants.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of study participants

Note

N = 174 unless otherwise noted.

1 Median monthly income for participants was $944.50.

Measures

Neuropsychological assessment

The four-hour battery was administered at the in-person screening. Full-scale IQ scores for each participant were estimated using the Ward 7 short form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales, 3rd edition (WAIS-III; Pilgrim, Meyers, & Whetstone, Reference Pilgrim, Meyers and Whetstone1999; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997a). Nine other cognitive domains were assessed: achievement, attention/concentration, executive function, language, mental speed, motor function, nonverbal memory, verbal memory, and visual-spatial function.

Employment activity

Participants’ employment-related activities were assessed at baseline and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months following baseline by participants’ self-report of their involvement in these activities during the six months preceding their appointment. The three work-related activities assessed were: (1) Paid employment – whether participants had full-time, part-time, temporary, or “under the table” paid employment; (2) Volunteer work – whether participants completed any unpaid volunteer work; and (3) Job training – whether participants attended job training classes or classes to develop specific job skills.

Covariates

Because the analytic approach used in this study did not show a significant effect for the intervention, experimental group was not considered an important covariate in these analyses. Other covariates were selected based on previous studies of HIV, employment, and cognitive functioning (e.g., Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; Rabkin et al., Reference Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, van Gorp and Lin2004; van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999).

Age. Participants’ years of age at the screening visit.

Education. Participants’ years of formal education and training.

Ethnicity. Participants’ self-identified ethnicity. This was categorized as White (not Hispanic/Latino), Black or African American (not Hispanic/Latino), Hispanic/Latino, or other ethnicity/multi-racial/Asian for this study.

CD4 count and viral load. Participants reported their most recent CD4 (T-cell) count and viral load.

Physical and mental health. We administered the SF-36 Health Survey (Ware, Snow, Kosinski, & Gandek, Reference Ware, Snow, Kosinki and Gandek1993), a widely used, well-validated 36-item self-report scale measuring eight health domains that has been used with HIV populations (Smith, Reference Smith, Sales and Folkman2000; Turner-Bowker, Bayliss, Ware, & Kosinski, Reference Turner-Bowker, Bayliss, Ware and Kosinski2003; Wachtel et al., Reference Wachtel, Piette, Mor, Stein, Fleishman and Carpenter1992). Two summary scores were computed from these domains, the Physical Components Score (SF-36 PCS) and the Mental Components Score (SF-36 MCS). Estimates of internal consistency for the eight SF-36 scales range from .73 to .96, with a median of .95. Test-retest coefficients range from .60 to .81, with a median of .76 (see, e.g., Ware et al., Reference Ware, Snow, Kosinki and Gandek1993).

Substance use. Participants reported the number of days they drank alcohol or used 10 classes of illicit drugs in the three-month period preceding their follow-up appointment. The drug categories were marijuana, amphetamines, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, designer or club drugs (e.g., ecstasy, ketamine), inhalants (e.g., poppers), and nonprescribed sedatives, painkillers, or methadone.

Procedure

All participants who completed the screening interview were paid $50.00, and, if eligible for the study, presented written verification of their HIV diagnosis, disability status, and stable residence prior to the baseline interview. All eligible participants were invited for the study’s baseline interview, and follow-up data were collected at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after this interview. Participants completing the baseline and any follow-up interviews were paid $25 per completed session. All participants were treated in compliance with our Institutional Review Board (IRB) regulations and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

To ensure completeness and accuracy of data entry, the baseline and follow-up interviews were administered by trained research assistants and employed a computerized format using the Questionnaire Development System (QDS) software (NOVA Research Company, 2003).

With the exception of the SF-36 and substance use measures, all measures in the baseline and follow-up interviews were administered in person. The research assistants read each item aloud and recorded participants’ responses directly into laptop computers. The SF-36 and substance use measures were completed by participants privately to minimize response bias. The research assistants demonstrated how to use the software and participants demonstrated they understood the operating procedures before completing these items. These self-administered measures were also programmed with computer-assisted audio, so that a computer-generated voice could read each item, and were programmed to prevent any item from being skipped.

RESULTS

We examined the influence of cognitive functioning on employment-related activities among HIV-infected adults seeking workforce reentry using two different statistical models. The first model assumed that participants’ employment-related activities increased prior to obtaining full-time employment, while the second model assumed that participants completed a series of steps in the process of obtaining full-time employment.

Dataset Preparation

Missing data

Not all 174 participants enrolled in the study attended the 24-month follow-up appointment. Therefore, missing employment and covariate data at the 24-month appointment were imputed using participants’ last observation carried forward (LOCF). One hundred seventeen participants (67.2%) completed the 24-month follow-up interview. LOCF-imputed scores for the remaining 57 participants were obtained as follows: 32 (18.4%) from the 18-month follow-up interview, 7 (4%) from the 12- and 6-month assessments, respectively, and 11 participants’ (6.3%) data were imputed from their baseline assessment.

IQ and NP domain scores

Estimated IQ scores were converted to percentile ranks using the age- and education-corrected norms for the WAIS-III (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997a). The NP test results were converted to percentile ranks based on available norms for each test. These normed test scores were used to calculate a mean percentile score for each domain. This analytic strategy was chosen to minimize the risk of Type I errors and to obtain more stable estimates of participants’ cognitive functioning in these domains. Table 1 displays the tests included in each cognitive domain and the descriptive statistics for each domain. It also shows which scores employed age, education, and/or gender corrections, and provides references for the normative studies used to compute these scores. Finally, we computed a global measure of cognitive functioning (Global Mean Percentile) consisting of the arithmetic mean of the nine cognitive domain mean percentiles.

Employment activity scores

Two employment scores were created for use with the two statistical models. The first score, used in the multiple regression analyses, was a weighted, summed employment activity scale assessing participants’ vocational activities in paid employment, volunteering, and job-training activities during the six months preceding the participants’ final study visits. Participants’ self-reported involvement in these vocational activities were summed, with those who reported full-time employment (i.e., > 30 hours per week) weighted to score “4.” Thus, if participants reported only one activity, they scored “1”; if they reported two activities, “2”; and if they reported 3 activities, “3.” However, if they reported full-time employment, they would score “4,” whether or not they participated in other employment activities during the six months preceding their final study visit. Thus, the weighted, summed employment activity scores ranged from 0 to 4 (M = 1.37, SD = 1.30).

The second employment score, Steps Toward Employment (ESteps), was employed with the ordinal logistic regression analysis. This score suggests that obtaining full-time employment may follow a progression of steps from no employment activity to obtaining full-time employment, and uses participants’ highest level of functioning in the specified period to estimate their placement on these steps. Thus, if participants reported no employment activities, they scored zero; job training or volunteer activities, “1”; part-time employment, “2”; and full-time employment, “3.” At their final study visit, participants’ reported ESteps were: 28.2% (n = 49) no employment activities (ESteps = “0”), 31.0% (n = 54) job training or volunteering (ESteps = “1”), 27.6% (n = 48) part-time employment (ESteps = “2”), and 13.2% (n = 23) full-time employment (ESteps = “3”).

Selection of covariates

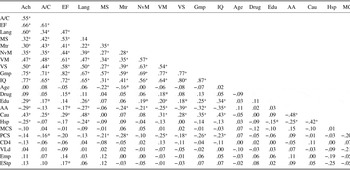

Table 3 presents the Pearson’s product moment correlation matrix of all variables included in this article. Seven potential confounding variables were significantly associated (p < .05) with cognitive performance, IQ, or employment activities: age, years of education, African-American ethnicity, Caucasian ethnicity, Hispanic ethnicity, number of days of alcohol or drug use in the three months preceding the baseline appointment, and the SF-36 PCS (Ware et al., Reference Ware, Snow, Kosinki and Gandek1993). Notably, CD4 count, viral load, and the SF-36 MCS (Ware et al., Reference Ware, Snow, Kosinki and Gandek1993) were not significantly associated with cognitive performance, IQ, or employment activity, so they were not included as covariates in the analyses.

Table 3. Pearson product moment correlations among study variables (N = 174)

Note

A/C = Attention/Concentration mean percentile; AA = African American ethnicity; Ach = Achievement mean percentile; Age = years of age; Cau = Caucasian ethnicity; CD4 = T-cell count at baseline assessment; Drug = Alcohol and drug use in the 3 months preceding baseline assessment; Edu = years of education; EF = Executive functioning mean percentile; Emp = employment activities weighted summed score at 24-month follow-up; EStp = employment activities scored using steps toward employment model; Gmp = Global mean percentile of cognitive domain percentile scores; Hsp = Hispanic ethnicity; IQ = Estimated WAIS-III full-scale IQ; Lang = Language mean percentile; MCS = SF-36 Mental Components Scale at baseline assessment; MS = Mental speed mean percentile; Mtr = Motor functioning mean percentile; NvM = Nonverbal memory mean percentile; PCS = SF-36 Physical Components Scale at baseline assessment; VLd = Log-10 transformation of viral load at baseline assessment; VM = Verbal memory mean percentile; VS = Visual-spatial mean percentile.

*p < .05; + p < .01.

Data Analysis

Multiple regression analyses

Three hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationships between cognitive functioning and employment activities, one investigating the relationship between IQ and employment activities, the second investigating the relationship between global NP performance and employment activities, and the third investigating the relationships between the NP domain scores and employment activities. These were conducted as separate analyses to address concerns about multicollinearity from the inclusion of WAIS-III subscales in the cognitive domain scores, Global Mean Percentile, and estimated full-scale IQ scores. Each analysis used the weighted, summed employment activity score as the dependent variable, entered potentially confounding covariates in Step 1, and added the variables of interest in Step 2.

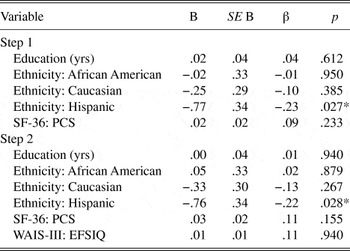

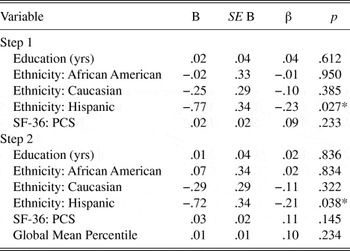

Relationship between IQ and employment activities. Step 1 of this analysis entered the five covariates significantly associated with IQ or the employment activity score (i.e., years of education, African American ethnicity, Caucasian ethnicity, Hispanic ethnicity, SF-36 PCS). This step was not significant, R(5, 168) = .231, p = .099. Step 2 of the model added estimated full-scale IQ and was also not significant, R(1, 167) = .246, p = .103. Table 4 presents the details of this regression analysis.

Table 4. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis of IQ’s influence on employment activities

Note

N = 174. R 2 = .053, p = .099 for Step 1; ∆R 2 = .007, p = .255 for Step 2. Employment activities = a weighted summed score of the patients’ self-reported employment activities (active employment, volunteering, job training) in the 6 months preceding the 24-month follow-up appointment.

* p < .05.

Relationship between cognitive functioning and employment activities. Step 1 of the first analysis entered the five covariates significantly associated with the Global Mean Percentile score or the employment activities score (i.e., years of education, African American ethnicity, Caucasian ethnicity, Hispanic ethnicity, SF-36 PCS) and was not significant, R(5, 168) = .231, p = .099. Step 2 of the model added the Global Mean Percentile score and was also not significant, R(1, 167) = .247, p = .099. Table 5 presents the details of this regression analysis.

Table 5. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis of influence of global cognitive performance on employment activities

Note

N = 174. R 2 = .053, p = .099 for Step 1; ∆R 2 = .008, p = .234 for Step 2. Employment activities = a weighted summed score of the patients’ self-reported employment activities (active employment, volunteering, job training) in the 6 months preceding the 24-month follow-up appointment; Global Mean Percentile = the arithmetic mean of the cognitive domain percentile scores.

* p < .05.

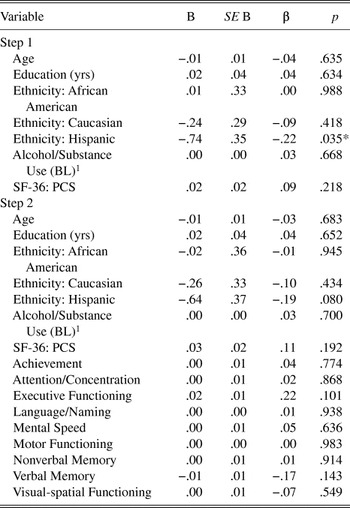

The second analysis investigated the relationship between the NP domains and employment activities and entered the seven covariates significantly associated with any of the cognitive domains or employment activities score (age, years of education, African American ethnicity, Caucasian ethnicity, Hispanic ethnicity, number of days of alcohol or drug use, and the SF-36 PCS) into Step 1 of the model and was not significant, R(7, 166) = .236, p = .208. Step 2 of the model added the mean percentile scores from the nine cognitive domains and was also not significant, R(9, 157) = .316, p = .369. Table 6 presents the details of this regression analysis.

Table 6. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis of the influence of cognitive domains on employment activities

Note

N = 174. R 2 = .056, p = .208 for Step 1; ∆R 2 = .044, p = .566 for Step 2. Employment activities = weighted sum of the patients’ self-reported employment activities (active employment, volunteering, job training) in the 6 months preceding the 24-month follow-up appointment.

1 Alcohol/Substance Use (BL) = sum of the patients’ self-reported days of use of 11 substances in the 3 months preceding the baseline appointment.

* p < .05.

Ordinal logistic regression analyses

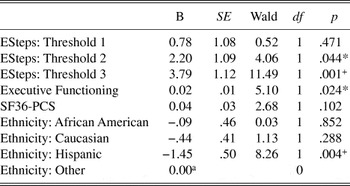

These analyses evaluated a model designed to predict participants’ progress toward employment. The NP domain scores, IQ, and the significant demographic and health variables (i.e., age, years of education, alcohol/drug use, SF-36 PCS, and ethnicity) were entered as predictors in the model. Three link functions (Logit, Cauchit, and Negative Log-Log) were examined to determine which fit the data most appropriately. The Logit function was selected because it best predicted scores at the higher levels of the ESteps variable, the levels with the most interest for this study. In order to refine the model and gain the best predictive value with the fewest predictors, only those predictors with Wald values greater than 2.5 in the first Logit analysis (executive functioning, SF-36 PCS, and ethnicity) were selected for a second ordinal regression analysis using the Logit link function. Executive functioning, SF-36 PCS, and ethnicity significantly predicted ESteps, χ2(5) = 19.42, p = .002, R 2N = .113, and the Test of Parallel Lines was not statistically significant, suggesting that the parallel slopes assumption of ordinal regression was met. Table 7 presents the contributions of each variable to the model, and Table 8 presents the classification table resulting from this analysis, a matrix of the ESteps values observed in our sample versus the values predicted by the statistical model. Table 8 shows that the model did not predict full-time employment, and only 63 participants (36.2%) were correctly staged using this model. Nevertheless, executive functioning was significantly and positively associated with reported employment, and Hispanic ethnicity was significantly and negatively associated with reported employment (see Table 7). Scores on the SF-36 PCS scale were not significant predictors in this model.

Table 7. Summary of ordinal regression model predicting steps toward employment

Note

N = 174. Link function: Logit. Model Fitting Information: χ2(5) = 19.42, p = .002. R 2cs = .106; R 2n = .113; R 2m= .042. Test of Parallel Lines, χ2(10) = 13.77, p = .184. ESteps = Steps Toward Employment (dependent variable), coded as 0 = No employment-related activities, 1 = participating in job training or volunteering, 2 = part-time employment (30 hours per week or less), and 3 = full-time employment (more than 30 hours per week).

a This parameter is set to zero because it is redundant.

* p < .05; +p < .01.

Table 8. Comparison of observed versus predicted categories in ordinal regression model predicting steps toward employment

Note

N = 174. The percentages listed in the table represent the predicted response/observed response. Values in bold font highlight predictions that match the observed response values.

a 30 hours or less paid employment per week.

b More than 30 hours paid employment per week.

DISCUSSION

We examined whether cognitive functioning predicted employment-related activity over a two-year period for a sample of HIV-infected individuals participating in a workforce reentry program. Previous cross-sectional studies have found that NP impairment among HIV-infected individuals was positively associated with reported levels of unemployment (e.g., Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999), and the only longitudinal study we were able to locate (Van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Rabkin, Ferrando, Mintz, Ryan, Borkowski and McElhiney2007) suggests the same. Thus, we expected to find a positive relationship between cognitive functioning and reported levels of employment activity, such as part-time or full-time employment, volunteer work, and job training.

We found that cognitive functioning did not predict employment activity very well in our sample. In the hierarchical regression analyses, we examined whether IQ and the mean percentile NP domain scores predicted the weighted sum of employment activities, which included part-time and full-time employment, volunteer work, and job-training activities. Neither IQ nor the mean percentile NP domains predicted the weighted sum of these employment activities at the participants’ final study visit.

In the ordinal logistic regression analysis, we conceptualized part-time paid work, and volunteering and job training as steps toward full-time employment. Between IQ and the nine cognitive domains we examined, we found that executive functioning was the only cognitive domain to positively predict steps toward employment. In addition, Hispanic ethnicity negatively predicted these employment steps.

Many job-related tasks require executive functions such as decision-making, planning, and judgment, and our findings are consistent with the findings of earlier investigations that suggest executive functioning affects employment among people with HIV. Van Gorp and colleagues (1999) found that unemployed people with HIV performed significantly worse on executive function tasks, and Rabkin and colleagues (2004) found that executive functioning was positively associated with total hours worked. However, we would like to highlight that the association between executive functioning and employment, while statistically significant, was weak, accounting for only a small percentage of the variance in our model. Moreover, as may be seen in Table 8, 63.7% of the participants were misclassified using this model. Although this model did predict employment significantly better than chance, it did not predict steps toward employment as well as we expected based on the previous literature (i.e., only 36.2% of participants were correctly staged using this model).

Our findings carry several implications for vocational rehabilitation with HIV-infected individuals. A common assumption among practitioners is that NP tests are useful tools for predicting successful employment. However, in our sample of participants with HIV who were seeking workforce reentry, cognitive testing generally did not predict employment activity at follow-up, or, in the case of executive functioning, was statistically significant but of marginal clinical utility. These results suggest that NP tests may not be the most clinically useful tools for informing HIV-infected individuals about whether they should attempt workforce reentry or for preparing them to return to work. Additional research tying NP testing results to vocational outcomes is needed before this application of NP testing may be considered useful among people with HIV who are seeking workforce reentry.

An extension of our findings is that problems with cognitive functioning may not necessarily be a barrier to employment if those problems are not severely debilitating. In our study, those with low cognitive functioning were as likely to engage in employment activities over a two-year period as those with high cognitive functioning. Demographic factors such as age, education, ethnicity, substance use, CD4 count, viral load, and physical and mental health also did not predict employment activity. It may be that motivational factors such as readiness for work, self-efficacy, and sense of purpose are more predictive of employment activity than cognitive functioning. Future research is needed to ascertain whether these or other factors may explain how and why some HIV-infected individuals can successfully engage in employment, while others have more difficulty.

Several factors may make our findings more relevant to clinicians contemplating use of NP testing to predict employment among people with HIV/AIDS than previous studies. Our sample was different from those of most earlier studies (e.g., Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Marcotte, Mindt, Sadek, Moore and Bentley2004; Rabkin et al, Reference Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, van Gorp and Lin2004; van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999), which used natural history samples of HIV-infected persons that are certain to include individuals with varying degrees of motivation to return to work. Our study specifically recruited individuals who were receiving disability compensation, contemplating returning to work, and were interested in participating in a vocational rehabilitation program. Because our study included only individuals motivated to return to work, the impact of cognitive performance as a predictor of employment may have been diminished.

Cognitive impairment at the most severe levels may be a barrier to workforce reentry. While acknowledging that our decision not to include those individuals with the most severe NP impairment may have restricted the range of NP performance in our sample, we believe it is of little consequence, because the number of individuals excluded due solely to impaired NP performance was very small (n = 8; 3.4%), and the range of percentile scores in our sample is large for all of the cognitive domains and estimated IQ (see Table 1).

We believe our study has several advantages over earlier investigations of HIV, employment, and cognitive functioning. Our study may have greater ecological validity, because the HIV-infected participants in our study were motivated to return to work, similar to those who are most likely to present for services at vocational rehabilitation programs. Our study was truly longitudinal, examining whether cognitive functioning predicted employment activity up to two years after the cognitive assessment. Finally, our study suggests that workforce reentry may entail a progression of steps toward employment and included methodology to test one model of the steps patients may take in their quest to reenter the workforce.

We believe our caveats concerning the clinical utility of NP tests with this population also apply to the findings reported by van Gorp and colleagues (2007), who reported that baseline CVLT Total scores predicted employment at follow-up. First, as the authors acknowledge, their findings should be regarded as preliminary, in part because of the large number of statistical tests conducted without any control for false positive findings. Second, a single test is unlikely to provide a stable estimate of patients’ functioning in a particular cognitive domain, and group research does not provide access to the clinical observations that might justify interpreting a single impaired performance in clinical settings. We opted for a composite measure, which we believed would have greater stability and precision, and found a relationship that, while statistically significant, may be of limited clinical utility. Finally, we note that the results found by van Gorp and colleagues and our results are consistent with the extant literature implicating executive functioning and verbal learning in employment among people with HIV (van Gorp et al., Reference van Gorp, Baerwald, Ferrando, McElhiney and Rabkin1999). However, we urge caution when interpreting these findings, because inconsistent results across studies and relatively small effect sizes for NP testing may attenuate confidence in the clinical utility of these tests for predicting vocational rehabilitation.

We found that Hispanic ethnicity negatively predicted steps toward employment in our sample. While additional research may help determine whether this finding is spurious (it is not reported in previous studies of HIV/AIDS and workforce reentry), factors such as acculturation (although all spoke English) or immigration status (which was not assessed) may figure in this finding.

Cohen and colleagues (2003) suggest that ordinal logistic regression “merit[s] more frequent use” (p. 525) in the analysis of behavioral data. We are indebted to their discussion of this methodology and the paradigm shift the methodology provided in this study. Ordinal logistic regression allows the use of a dependent variable with ordered categories when the categories are assumed to represent an underlying, latent continuum, and interval-level assumptions of measurement may not be met. It also provides a mechanism to test whether the effects of the independent on the dependent variables are equivalent at each threshold between categories, it provides a measure of the odds of crossing thresholds between categories, and it provides threshold estimates. Similarly, it allows for the construction of a classification matrix, which demonstrates, in an applied way, how well the statistical model fits the observed data.

We believe the discrepant results obtained in the multiple regression and ordinal logistic regression analyses are a result of a higher level of precision in the ESteps employment variable. Both approaches assume that obtaining full-time employment is a desirable outcome for disabled people with HIV or AIDS, and assess participants’ progress toward obtaining full-time employment. Both implicitly allow that obtaining full-time employment may not be a reasonable goal for some people with HIV who would like to reenter the workforce, and should be more robust than a dichotomous (yes/no) employment measure. However, the ESteps variable, which uses the highest level of vocational functioning to estimate participants’ progress toward obtaining full-time employment, appears more precise, perhaps because the quantity of vocational activities is not necessarily related to their quality or their likelihood of success for achieving full-time employment.

A possible objection to this study is the length of time between the assessment of cognitive functioning and the measurement of employment activities. However, we believe this to be one of the study’s strengths; cognitive functioning is presumed to be relatively stable or in decline in patients with HIV and advocates of using cognitive testing for vocational rehabilitation programs often employ these measures as screening tools. In fact, van Gorp and his colleagues (2007) found that results from a baseline neuropsychological screening assessment were as effective as later neuropsychological assessments at predicting employment at follow-up in a sample that was similar to ours. Thus, the design of this study allows for a truly longitudinal assessment of the effects of cognitive functioning on employment activities in a way that closely mirrors the way these tools are currently used in vocational rehabilitation settings.

This study provides marginal support for earlier findings on the role of cognitive functioning in employment among patients with HIV. Although executive functioning significantly predicted participants’ steps toward employment, the effect was smaller than anticipated, and we suggest that other factors might play a more prominent role in predicting reentry into the workforce among people with HIV who are seeking workforce reentry. It should be noted that this study only assessed employment and did not assess level of employment or how well participants functioned at their jobs. Further research is needed to elucidate the roles that cognitive functioning and motivational factors play in the vocational rehabilitation of people with HIV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partially supported by Grant #1 RO1 MH62966-01A1 to David J. Martin, Ph.D., and the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute. The findings and views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the funding agencies. None of the authors has any financial or other relationship that could be construed as a conflict of interest affecting this article.