INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative disorders associated with aging are a rapidly growing public health crisis. Early detection is critical for accurate and timely diagnosis and is important for facilitating entry into clinical trials, once available. In primary care settings, screening tools for the early detection of cognitive impairment that are simple to administer, short, and well validated are particularly valuable. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease causing dementia among individuals over 65 (Hebert, Weuve, Scherr, & Evans, Reference Hebert, Weuve, Scherr and Evans2013). Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) is typically characterized by episodic memory deficits, or amnesia, in early stages (Weintraub, Wicklund, & Salmon, Reference Weintraub, Wicklund and Salmon2012). Several screening instruments have been developed to identify differences between normal age-related changes in cognition and mild stages of DAT. In particular, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (a prodromal state in which there is cognitive impairment with minimal impact in activities of daily living; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Lopez, Armstrong, Getchius, Ganguli, Gloss and Rae-Grant2018) have become increasingly important to research as they are at high risk for progression to DAT (Gauthier et al., Reference Gauthier, Reisberg, Zaudig, Petersen, Ritchie and Broich2006). Studies have shown memory to be the first cognitive domain to decline in patients who progress to DAT (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Roberts, Knopman, Boeve, Geda, Ivnik and Jack2009); as such, research on screening tools has typically focused on the amnestic phenotype of dementia. Within the last few decades, it has become clear that AD does not exclusively manifest as an amnestic syndrome, and that, although less common than amnesia, progressive visuospatial, language (i.e., aphasic), or behavioral deficits may also appear early in disease course (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, McGinnis, Xia, Price, Atri, Murray and Wolk2017; Rogalski et al., Reference Rogalski, Sridhar, Rader, Martersteck, Chen, Cobia and Mesulam2016).

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is diagnosed when language impairment arises as the most salient symptom and progresses to affect daily functioning. Indeed, PPA can be caused by frontotemporal lobar degeneration or AD, the latter of which has been shown to be atypically distributed in left-hemisphere language regions as opposed to memory-related limbic regions (Gefen et al., Reference Gefen, Gasho, Rademaker, Lalehzari, Weintraub, Rogalski and Mesulam2012). Most screening instruments were not developed to differentiate among distinct clinical dementia syndromes such as DAT versus PPA. In fact, a common instrument, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), has been shown to penalize individuals with PPA since the performance is heavily dependent on language (Osher, Wicklund, Rademaker, Johnson, & Weintraub, Reference Osher, Wicklund, Rademaker, Johnson and Weintraub2007).

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was published in 2005 as a brief cognitive screening tool with high sensitivity and specificity (Nasreddine et al., Reference Nasreddine, Phillips, Bedirian, Charbonneau, Whitehead, Collin and Chertkow2005). It was originally used to detect MCI in patients who performed in the “normal range” on the MMSE. The MoCA has been validated in typical amnestic DAT (Nasreddine et al., Reference Nasreddine, Phillips, Bedirian, Charbonneau, Whitehead, Collin and Chertkow2005), but it remains unclear whether the MoCA can be used to differentiate between distinctive clinical dementia syndromes in which episodic memory loss is not a primary symptom. The MoCA total score is comprised of 30 points for items categorized into six domains: (1) Memory; (2) Executive Functioning; (3) Attention; (4) Language; (5) Visuospatial; and (6) Orientation. Items in each domain yield individual index scores, providing an opportunity to make use of domain-specific test items in characterizing different dementia syndromes. The current study compared MoCA Index scores between cognitively normal controls, patients in mild stages of DAT with an amnestic syndrome, and patients in mild stages of PPA with an aphasic syndrome. The goal was to determine whether the use of MoCA Index scores could help differentiate the salient deficits unique to amnestic versus aphasic dementia syndromes in early stages.

METHODS

The design of this study was an analysis of existing data from participants enrolled in the Clinical Core of the Northwestern Alzheimer’s Disease Center, 1 of 32 such centers funded by the National Institute on Aging/NIH. Participants were excluded if they showed a history of, or unmanaged, neurological or psychiatric impairment. Individuals with a primary uncorrected visual or significant hearing impairment were also excluded. Participants are followed annually with a set of procedures common to all centers, the Uniform Data Set–Version 3 (UDS-3) (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Besser, Dodge, Teylan, Ferris, Goldstein and Morris2018). Written informed consent was collected from each subject and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University.

The groups identified for this study included: mild DAT (n = 33), PPA (n = 37), and cognitively normal control participants (n = 83). The clinical amnestic DAT diagnosis was based on the most up-to-date research diagnostic criteria used by all Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (McKhann et al., Reference McKhann, Knopman, Chertkow, Hyman, Jack, Kawas and Phelps2011). The PPA root diagnosis was based on the criteria of Mesulam (Reference Mesulam2003), and PPA subtyping was not considered for inclusion. Participants received a Global score (0–3) from the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, a screening measure to stage dementia severity (Morris, Reference Morris1993). DAT and PPA patients were selected if the Global CDR score ≤1.0 to ensure early stages of cognitive impairment. For the PPA group, a CDR Memory domain score of ≤.5 was required in order to reflect the absence of significant memory dysfunction. Scores from the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (ADL-Q), a validated measure for rating functional dependence based on informant report, were used to ensure that those with severe levels of dependence were excluded (Johnson, Barion, Rademaker, Rehkemper, & Weintraub, Reference Johnson, Barion, Rademaker, Rehkemper and Weintraub2004). Healthy controls were selected based on normal neuropsychological performance on the UDS-3 battery (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Besser, Dodge, Teylan, Ferris, Goldstein and Morris2018), well-preserved activities of daily living as reported by a study partner, and a CDR Global score of 0.

Procedures

All participants had completed the MoCA as part of the UDS-3 neuropsychological battery. Total MoCA scores and index scores were obtained from initial enrollment based on the NACC UDS-3 scoring criteria (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Besser, Dodge, Teylan, Ferris, Goldstein and Morris2018). All index scores were calculated based on the validated methods reported in the NACC UDS-3 scoring criteria (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Besser, Dodge, Teylan, Ferris, Goldstein and Morris2018) based on Nasreddine et al. (Reference Nasreddine, Phillips, Bedirian, Charbonneau, Whitehead, Collin and Chertkow2005), and on Julayanont, Brousseau, Chertkow, Phillips, and Nasreddine (Reference Julayanont, Brousseau, Chertkow, Phillips and Nasreddine2014). Some subjects showed cognitive decline during their longitudinal participation in the Clinical Core and therefore met the criteria for DAT after their initial enrollment. In these cases, the participant’s MoCA from their first visit in which a DAT diagnosis applied was used.

Statistical Analysis

Given that equal variances were not assumed, and significant differences in age between groups, a one-way analysis of covariance with the post hoc Games–Howell procedure, both adjusted for age, was used to compare MoCA total scores and each domain-specific index score across the three groups. The experiment-wise error rate used for the post hoc tests was .05. Two-sample t-tests were used to compare Global CDR scores between PPA and DAT. A logistic regression was performed to investigate the relative likelihood of group affiliation based on MoCA Index scores on an individual level. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 25 (Armonk, NY), R version 3.6.1 (Vienna, Austria), and SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) statistical software packages.

RESULTS

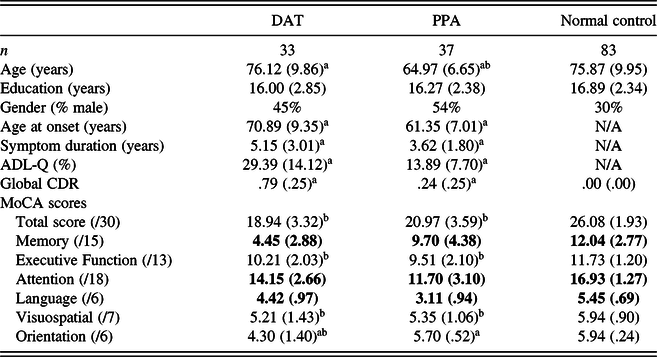

Group MoCA scores and demographic information are presented in Table 1. Global CDR Scores were significantly different between DAT (mean = .79; SD = .25) and PPA (mean = .24; SD = .25) groups (p < .001). Significant differences were due to the fact that the Memory “box” score impacts the Global CDR score, but the Language score does not. Individuals with PPA (mean age = 64.97) were significantly younger than those in DAT (mean age = 76.12) and normal control groups (mean = 75.87; p < .001). There were no significant differences in educational levels across groups. There was a significant difference in age at onset between patient groups (p < .001), and the DAT group showed a greater symptom duration compared to the PPA group (p < .05). There were no gender differences across the entire sample when comparing MoCA total scores.

Table 1. Demographics and MoCA total and index scores (mean raw score; SD)

Note. The bold values indicate significant differences between all groups at p < .05. Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (ADL-Q) (lower score indicates less impairment). Symptom duration = age at visit – age at onset.

a Significant differences between DAT and PPA groups at p < .05

b Significant differences compared to NC at p < .05.

As expected, the MoCA total score (max = 30) was significantly lower for both patient groups compared to the control group (mean = 26.08; SD = 1.93; p < .001), but there was no difference between DAT (mean = 18.94; SD = 3.32) and PPA groups (mean = 20.97; SD = 3.59). When index scores were analyzed across groups, individuals with DAT scored significantly lower on Memory [mean = 4.45 (15 total); SD = 2.88] and Orientation [mean = 4.30 (6 total); SD = 1.40] Indices compared to the other groups (p < .001). PPA patients scored significantly lower in Language [mean = 3.11 (6 total); SD = .94] and Attention [mean = 11.70 (18 total); SD = 3.10] Indices compared to other groups (p < .001). There were no differences between the patient groups in Executive Function and Visuospatial Index scores. The normal control group scored significantly higher than each patient group in all domain-specific index scores, except in the Orientation domain where there was no difference observed between normal controls and the PPA group.

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), a commonly used data-based covariate selection technique (Konishi & Kitagawa, Reference Konishi and Kitagawa2008), was employed to determine which MoCA Index scores to include in a multivariate logistic regression model. A model including the Memory, Language, and Orientation Indices collectively showed the smallest BIC, indicating the best fit model with the observed data. The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the individual effects of Memory (p = .001), Language (p = .002), and Orientation (p = .025) Indices were significant. This suggested that a higher Memory or Orientation Index score predicted a significantly lower likelihood of falling within the DAT versus PPA group with an odds ratio of .53 (95% CI .33–.73) and .19 (95% CI .03–.61), respectively. A higher Language Index score was associated with a significantly higher probability of affiliation in the DAT group with an odds ratio of 14.72 (95% CI 3.71–139.35) compared to the PPA group.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to compare MoCA Index scores in patients with DAT, an amnestic form of dementia, and PPA, an aphasic dementia syndrome. The hypothesis was that MoCA Index scores would be able to differentiate between distinct clinical dementia syndromes at early stages of disease. Previous research on MoCA scores has primarily focused on differences in total scores with few studies examining the utility of index scores. While it has been shown that the MoCA total score has greater incremental validity than individual index scores (Goldstein, Milloy, & Loring, Reference Goldstein, Milloy and Loring2018), others have shown the utility of the MoCA Memory Index score to discriminate between normal controls and patients with amnestic-MCI (Kaur, Edland, & Peavy, Reference Kaur, Edland and Peavy2018). Julayanont et al. (Reference Julayanont, Brousseau, Chertkow, Phillips and Nasreddine2014) showed that 90.5% of MCI participants with a MoCA Memory Index score less than 7/15 at baseline progress to AD dementia within the average follow-up period of 18 months, suggesting that the Memory Index score can be used as a predictor of progression.

Our analyses compared each diagnostic patient group to one another and with a cognitively normal control group. Results showed no significant differences in the MoCA total score between patient groups. However, there were differences among index scores between groups that reflected unique syndrome profiles specific to DAT and PPA; while the DAT group showed poorest scores on Memory and Orientation Indices, the PPA group showed poorest scores in Language and Attention Indices. To explore the effect of index scores on the individual level, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression which supported our findings at the group level, that is, that an individual scoring lower on Memory and Orientation Indices is significantly more likely to affiliate with the DAT group compared to the PPA group, and those scoring lower on the Language Index are more likely to affiliate with the PPA group. These patterns are consistent with the salient clinical presentations of each group, namely DAT characterized by predominant amnesia, and PPA characterized by predominant aphasia. While the PPA group showed lower scores on the Memory Index compared to controls, performances were still higher than those demonstrated by the DAT group. Our prior work using the Three Words-Three Shapes Test in patients with PPA showed that non-verbal learning and recall were normal. In addition, although effortless verbal recall was impaired, effortful learning and delayed recognition of words were preserved. (Weintraub et al., Reference Weintraub, Rogalski, Shaw, Sawlani, Rademaker, Wieneke and Mesulam2013).

Our findings highlight the utility of MoCA Index scores in clinical practice to assist in the early detection of domain-specific cognitive impairment. Still, careful clinical characterization of dementia phenotypes and diagnosis requires a more systematic and thorough neuropsychological examination by a trained professional. Limitations of our study include predominantly high education levels among participants. Further, given that this was an antemortem sample, the relationship between disease duration and MoCA performance between groups remains unclear. In general, subsequent studies with larger sample sizes would be ideal, allowing for close inspection of differences between PPA variants, and, perhaps, generation of specific cut-off scores to help screen for phenotypic patterns.

These findings provide evidence that MoCA Index scores may help distinguish amnestic and aphasic dementia syndromes at early stages of disease course. Its utility in identifying relative impairments in specific cognitive domains may assist with clinical diagnosis and phenotypic characterization and can be particularly useful in primary care settings in which brief screening instruments are favored.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health (P30 AG013854, R01 NS075075, R01 AG056258), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders/National Institutes of Health (R01 DC008552), a National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center New Investigator Award (U01 AG016976), and the Florane and Jerome Rosenstone Fellowship.