INTRODUCTION

Although verbal memory deficits have been associated consistently with left temporal lobe epilepsy (LTLE), the findings are less robust for nonverbal impairments in spatial memory associated with right temporal lobe epilepsy (RTLE; Barr, 1997; Baxendale et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2003). Although some studies detect deficits among RTLE patient's propensity in recalling unfamiliar faces (Seidenberg et al., 2002) and location in space (Abrahams et al., 1997; Baxendale et al., 1998), the clinical assessment of nonverbal memory occurs primarily through performance on figural drawing tasks, such as the Benton Visual Retention Tests, and visual reproduction subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS). Among those studies using figural reproductions as measures of nonverbal memory in patients with TLE, some have demonstrated impairments in the recall conditions for individuals with seizures of right temporal origin (Abrahams et al., 1997), whereas others have disconfirmed the material sensitivity hypothesis (Barr et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2002). These discrepancies, along with the extensive documentation of material-specific deficits in temporal lobe epilepsy, pose the question of whether current neuropsychological measures are sufficient in detecting the nature of the memory deficits characterizing individuals with seizures of left or right temporal origin (Sawrie et al., 2001).

Several hypotheses have been proposed for the equivocal literature in individuals with RTLE. These concepts range from poor definitions of the constructs regulated by the right hemisphere, to lack of uniformity in the measures chosen for assessment (Barr, 1997), and the confounding of information (verbal and spatial) on these measures (Barr et al., 1997; Breier et al., 1996; Pelo et al., 1998). One commonly used instrument for assessing nonverbal memory is the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT). Few studies have demonstrated lateralization capabilities using the original scoring system for the figure (Lezak, 2004; Spreen & Strauss, 1998). Several scoring systems have been developed to address this issue, each with varying degrees of success (Lezak, 2004; Loughead et al., 2000; Spreen & Strauss, 1998; Troyer & Wishart, 1997; Waber & Holmes, 1986). One consideration that may allow the RCFT to assist in the detection of material specific lateralized memory deficits is the application of global and local paradigms of hemispheric specialization (Binder, 1982; Poreh & Shye, 1998). Recent investigations of hemispheric asymmetries offer further support for the right hemisphere's succinctness in processing global information and the left hemisphere's superiority for detecting local features through the use of visual hierarchical stimuli. For instance, Loring et al. (1988) were able to specify site of seizure focus in a sample of 29 presurgical temporal lobe epilepsy patients according to 11 criteria assessing for perseveration, rotation, the presence of additional line segments, major mislocations, and distortions of additional details (e.g., diamond, large triangle). Observation of the figural reproductions of RTLE patients revealed distortions and omissions to the overall configuration of the stimulus. LTLE patients made errors on the details of the stimulus (Loring et al., 1988; Piguet et al., 1994) more frequently than did those with seizures originating in the right temporal lobe. Thus, strategies for drawing configurational (global) and detail-oriented (local) components of the RCFT have potential in differentiating between epilepsy focus groups (Schwartz et al., 2000; Stern et al., 1994). Although several investigations have characterized deficits of left and right TLE patients using global and local features of the RCFT (Breier et al., 1996; Loring et al., 1988; Stern et al., 1994), many clinicians often evaluate performance in the context of overall scores and by clinical observation (Chervinsky et al., 1992). An overlooked aspect of scoring the figure is the subjective approach clinicians take in deciding whether a reproduction has errors in the overall configuration or in the details of the figure. A scoring system using clinical ratings to define RCFT items as global or local elements would allow for another approach in examining material specific deficits characterizing left and right temporal lobe epilepsy patients.

The goal of the present study was to evaluate the ability of estimations of global and local RCFT items to differentiate between individuals with left or right TLE. The first aim of the study focuses on obtaining clinical ratings of globally and locally oriented items on the RCFT. We hypothesized that the performance of LTLE and RTLE patients would be differentiated on the RCFT by using the global and local components of the figure. Specifically, it was predicted that RTLE patients would exemplify lower Global index scores than LTLE patients and that patients with LTLE would have lower mean scores on the items composing the Local index. It was also predicted that the performance of each group would vary according to RCFT trial, with worsening performance across the copy, immediate, and delay conditions, and with maximal group discrimination occurring in the delayed condition.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 146 temporal lobe epilepsy patients (selected from an Internal Review Board-approved archival database) who underwent anterior temporal lobectomy. Demographic data for the sample are displayed in Table 1. The sample was composed of individuals with seizures of focal temporal lobe origin, with lateralization of seizure onset either exclusively or primarily left temporal (LTLE) in 83 patients, and right temporal (RTLE) in 63 patients. Preoperative diagnostic procedures consisted of magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (with T1- and T2-weighted images in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes), as well as video/electroencephalographic monitoring with 128-channel scalp electrodes. For those participants who underwent Wada testing, only individuals who had left hemisphere speech/language lateralization were included. In addition, the sample consisted of individuals who were right-hand dominant. Exclusionary criteria were evidence of temporal cortical developmental lesions, bilateral hippocampal sclerosis, or other temporal lobe pathology. All of the individuals included in the sample eventually underwent unilateral anterior temporal lobe resection.

Mean demographic information for selected right (RTLE) and left temporal lobe epilepsy (LTLE) patients

RTLE and LTLE patients were compared using independent samples t tests for age, education, age of seizure onset, full-scale IQ score (FSIQ), and California Verbal Learning Test Scores-II (CVLT) Trials 1–5 scaled scores (see Table 1). Results revealed that there were no significant group differences between the RTLE and LTLE groups across any variable with the exception of the CVLT-II Trials 1–5 scaled score. Individuals in the RTLE group obtained higher scores on this measure than those in the LTLE group. Due to the clinical significance of this difference, the score was used as a covariate in subsequent analyses. There was no evidence that the right and left TLE groups differed in their ratios of men and women χ2(1, n = 63) = .35; p = .55.

PROCEDURES

Phase I: Expert Ratings

Materials

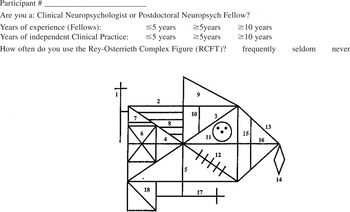

A questionnaire (see Appendix) composed of the RCFT items (Lezak, 2004) was used to obtain clinician ratings. The overall layout for the questionnaire consisted of: a display of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure, a description of the rationale for completing the questionnaire, and a set of instructions with definitions of global and local features to use for rating the answer choices. A description of each item was accompanied by a closed-ended question (e.g., “This item is most accurately described as:) paired with the seven-point Likert scales. Labels for the scale were defined as: Local and Global indices, with numerical units assigned to each descriptor. The Local anchor included unit 1 on the scale, whereas the Global anchor subsumed unit 7. Raters were expected to choose the option they believe characterized the nature of the specified item.

A similar questionnaire was submitted to obtain clinical estimates of how easily verbalized each of the RCFT items were. The questionnaire featured a different set of instructions for easily verbalized and difficult to verbalize information. Raters were again expected to choose the option that characterized the nature of the specified item.

Data collection

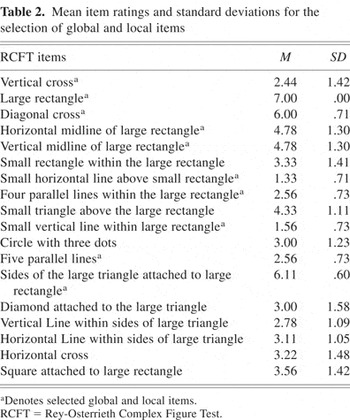

The global/local questionnaires were issued to a panel of practicing neuropsychologists and postdoctoral fellows (with an emphasis in neuropsychology) who were familiar with the RCFT. The questionnaires were collected, and the degree to which each item was rated Global or Local was averaged by tallying the participants' responses and dividing this sum by the number of raters. The average item scores on the Likert scales were then used to classify each item into one of the categories (see Table 2).

Mean item ratings and standard deviations for the selection of global and local items

Items with an average rating of less than 2.5 were tallied for the Local score, and items receiving a score greater than 5.5 were tallied as Global. The composite list contained a total of 10 items, composed of 5 global and 5 local items based upon the clinical rankings. This list was used to compare the performance of RTLE and LTLE patients during phase II of the study.

An additional questionnaire was issued to a panel of neuropsychologists (n = 5) and fellows (n = 1) to obtain clinical estimates of verbalizability for the selected items. The degree to which the global and local items were easily verbalized was averaged, yielding separate verbalization scores for each index. Items that were easily verbalized received a lower score (e.g., 1, 2) on a scale of 1–7, whereas items that were difficult to verbalize received higher scores (e.g., 6, 7).

Phase II: Analysis of RCFT protocols

Assessment and scoring

Participants were administered the RCFT (copy, immediate, delayed), as part of a larger presurgical neuropsychological evaluation. The RCFT was scored according to the criteria described by Meyers & Meyers (1995). Interrater reliability indices were calculated between the original scores of a subset of 20 protocols. Blinded scoring was performed by the first author (R.M.) and a psychometrician (M.D.) on the copy (.90), immediate (.90), and delay (.89) sections of the RCFT. Separate global and local composites were calculated by summing the items corresponding to each index. Participants' scores on the selected items were recorded for each reproduction of the RCFT (i.e., copy, immediate, and delay), and scores for the Global and Local indices were calculated.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Expert Ratings

Mean item totals for the global/local questionnaire are shown in Table 2. A total of nine questionnaires (n = 6 neuropsychologists, n = 3 fellows) were collected and used to calculate the averages of each item. Three items (1, 7, and 10) met the inclusion criteria of an average score of less than or equal to 2.5 for the Local index, and three items (2, 3, and 13) exceeded the 5.5 or greater criteria for inclusion into the Global Index. For each index to have a minimum number of five items, items 8 and 12, with an average of 2.56, were added to the Local Index, whereas items 4 and 5, both with the average of 4.78, were selected to complete the Global Index.

An estimate of inter-rater reliability was calculated to assess the amount of agreement between clinician's ratings on the global/local questionnaire. The coefficient showed that there was excellent agreement between raters (α = .95).

The global and local indices were also characterized in terms of the verbalizability questionnaire (see Table 3). Two items (2 and 3) from the global index were rated as less than or equal to 2.5 and were classified as easily verbalized. Only one item (1) from the local index met this criteria. One item (10) from the local index obtained a score that was greater than or equals to 5.5, and was classified as difficult to verbalize. This item was coded negatively in the data set.

Mean item ratings and standard deviations for verbalization of the items

Global versus Local scoring

Performance on the global and local scores were analyzed in a 2 × 3 × 2 (focus × trial × index) analysis of covariance with seizure focus (left, right) serving as the between-subjects factor, and trial (copy, immediate, delayed) and index (Global, Local) as within-subjects factors. The CVLT Trials 1–5 scaled score was used as a covariate. The analysis yielded a significant main effect for index F(1,141) = 163.33; p < .001, and trial F(2,282) = 29.63; p < .001, and a significant interaction between index and trial F(1.41,282) = 8.82; p < .001. Specifically, the index by trial interaction accounted for approximately 5.9% of the variance in the RCFT scores. There was no main effect for focus F(1,141) = .842; p = not significant (n.s.), and the interaction of focus and index did not yield significant differences between the scores of LTLE and RTLE groups F(1,141) = .385; p = n.s. Similarly, the three way interaction between seizure focus, index, and trial was also nonsignificant F(1.41,282) = .086; p = n.s. Means depicting the index by trial interaction for the RTLE and LTLE groups are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. The significant index by trial interaction was further analyzed by means of simple effects, where index was examined within each level of trial. Results of the simple effects analysis revealed a significant difference between the global and local indices in the copy F(1,142 = 5.23; p = .024), immediate F(1,142) = 445.26; p < .001 and delay trials F(1,142) = 427.82; p < .001. The mean score for the global index was consistently higher than the local index in both the copy, immediate, and delay trials of the RCFT.

Mean scores for right temporal lobe epilepsy (RTLE) group in each Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) trial.

Mean scores for left temporal lobe epilepsy group in each Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) trial.

Bivariate correlations were also performed to assess the relationships between the global and local indices and CVLT-II Trials 1–5 scaled scores for each trial (see Table 4). For the LTLE group, Trials 1–5 scaled scores were marginally correlated with the global and local indices of both the immediate and delay RCFT trials. Only the local index score in the immediate RCFT trial was correlated with Trials 1–5 scaled score for the RTLE group.

Correlations between Index, Trial, and California Verbal Learning Test trials (1–5) scaled scores

Verbalization

See Table 5 for mean verbalization scores for the RTLE and LTLE groups. Independent samples t tests revealed that there were no differences between the RTLE and LTLE groups for the global verbal and local verbal indices for the copy (tglobal(1,144) = −1.20, p = n.s.; tlocal(1,144) = −.56, p = n.s), immediate (tglobal(1,144) = −.35, p = n.s.; tlocal(1,144) = −.16, p = n.s.), and delay trials (tglobal (1,144) = −.51, p = n.s; tlocal(1,144) = .57, p = n.s.). However, to control for the potential effects of verbalization on the original global and local indices, the primary analysis was repeated using verbalization scores as covariates. Results showed that there was a main effect for trial F(2,137) = 12.00, p < .001. Although the index by trial interaction was no longer significant, F(2,137) = .27, p = n.s., there were several interactions between index, trial, and the verbalization covariates. Within the copy trial, there was an interaction between index (global, local) and the global verbalization measure F(1,138) = 10.91, p < .001, but not the local verbalization measure F(1,138) = 2.53, p = n.s. In the immediate trial, neither the local verbalization measure F(1,138) = .00, p = n.s., nor the global measure F(1,138) = 2.16, p = n.s., interacted significantly with index. Finally, in the delay trial, there was an interaction between index and the global F(1,138) = 10.27, p = .002, and local F(1,138) = 4.40, p = .04, verbalization measures. Similarly, there were interactions the global and local verbal indices and the copy Fglobal(1,137) = 23.63, p < .001; Flocal(1,137) = 11.89, p < .001; immediate Fglobal(1,137) = 16.80, p < .001; Flocal(1,137) = 24.45, p < .001; and delay trials Fglobal(1,137) = 26.45, p <. 001; Flocal(1,137) = 12.90, p < .001.

Mean verbalizability scores for the right (RTLE) and left temporal lobe epilepsy (LTLE) groups on the global and local indices.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the present investigation was to identify whether ratings of global and local items on the RCFT would be able to differentiate between right and left TLE groups. The primary hypothesis was specifically addressed by analyzing the relationship between the Global and Local indices and site of seizure origin to test the prediction that differences between global and local scores would vary according to seizure focus. Results did not support the primary hypothesis. RTLE and LTLE groups were not discerned in regard to their scores on the Global and Local indices. Furthermore, the absence of the effect was noted to occur across the copy, immediate, and delay trials of the RCFT. Instead, it was found that the index scores became more distinct across time, in that the Global index consistently yielded higher scores than the Local index, which declined rapidly. Although this difference existed in the copy condition, that it was more pronounced in the immediate and delay conditions suggests that the global index was resistant to changes at each interval, whereas the local index was more sensitive to delays over time.

The present findings add to the equivocal literature on the efficacy of the RCFT in lateralizing brain dysfunction. Despite utilization of clinical indicators of global and local items, interpretation of the figural reproductions with this application of the paradigm did not produce results differentiating groups of patients with unilateral brain dysfunction. Instead, only mild associations between verbal memory and LTLE were observed during the immediate and delay trials. Many investigators have explored the relationship between memory content and lateralization in presurgical epilepsy candidates, and the distinctions between the right and left hemispheres in processing modality-specific information have been described in a range of contexts (Fedio & Mirsky, 1969; Kim et al., 2003; Spiers et al. 2001;). However, the results are less consistent when using the RCFT to understand hemispheric contributions to memory processing (Barr, 1997; Barr et al., 1997). Research examining the global/local distinction is sparse, and the few studies that have been conducted demonstrate various effect sizes (Barr et al., 1997; Boles, 1984). For the current study, an a priori power analysis revealed that it was unlikely that the absence of the focus by index effect could be attributed to inadequate sample size.

The rapid deterioration of the local index from the copy to the immediate trial appears to suggest greater difficulty in the retention of these items, and this effect exceeded that which would be expected to occur due to seizure focus. Thus, the items composing the local index were consistently lower than those in the global index after both 3- and 30-minute delay periods. In contrast, the global index, while also demonstrating mild declines, was better preserved across the immediate and delayed trials. A possible reason for these differences is that the local elements were more obscure than the items selected for the global index. The current results suggest that verbalization may influence the relationship between global and local stimulus properties and time. After controlling for verbalizability in the copy, immediate, and delay trials, there was no significant relationship between index and trial. Furthermore, the global and local indices were related to the global verbalization measure in both the copy and the delay trials. Only in the delay trial was the local verbalizability measure related to each index. Because both the global and local indices were verbalized to some extent, this finding suggests that the indices may have had both visual and verbal representation in memory. If the global items were processed by the right hemisphere, and verbalized by the left, this function may account for why the global index was more resistant to changes across time. The local index, however, is processed primarily in the left hemisphere and would be more susceptible to change. However, this relationship remains speculative.

Another potential explanation for the decrease in the local index is a perceptual bias. For example, the more unifying, or global, elements could be perceived as more attentionally salient or relevant in reproducing the figure, even in the presence of right mesial temporal lobe damage. This finding may best be illustrated within the context of the tachistoscopic evidence demonstrating the priority of global elements in perception (Martin, 1979; Sergent, 1982). However, whereas a perceptual bias that leads one to analyze global elements before local has been heavily alluded to in the literature, research conducted by Robertson and Lamb (1991) contend that both perceptual and attentional processes play a role in the analysis of global and local information. As a result, the global elements may be attended to first, and minor details, although similar (such as the small horizontal line above the small rectangle and the small vertical line within large rectangle) could require more effort to recall, even in the presence of lateralized brain dysfunction. Selection of the items by means of the clinical rating method had both advantages and limitations. Because many clinicians rely on their experience to judge the nature of impairment expressed on the RCFT (Chervinsky et al., 1992), obtaining ratings of global and local items provides more external validity. Given the current results, it may appear as if the clinicians were inaccurate in selecting the elements or that the original RCFT items simply may not be divisible into global and local elements. However, previous research, although limited, suggests that this is not the case. In reviewing the total item list, it was observed to bear similarities to the items demarcated by other qualitative scoring systems (Binder, 1982; Poreh & Shye, 1998; Stern et al., 1994).

It is interesting to note that the decline of the Local score occurred immediately after the stimulus presentation, and then stabilized for the delayed condition. This finding indicates that the information that was processed immediately was retained. An important piece of information to examine would be whether the Local score could be improved with cueing. In this regard, a recognition trial of the RCFT would help to clarify whether an encoding problem was the source of the decline, or if it could be more accurately characterized as a retrieval problem. Furthermore, incorporation of a comparison group in examining the most frequently missed/retained elements would help to establish whether the differences in the global and local indices are germane to normal control and/or patient groups with generalized central dysfunction (e.g., patients with generalized epilepsy). This information could then be used to more accurately portray the nature of spared/impaired nonverbal functions among individuals with TLE.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The present study addressed the question of whether clinical estimations of global and local items on the RCFT are sensitive to unilateral mesial temporal lobe dysfunction. Results showed that individuals with right or left TLE could not be differentiated based on their performance of a global/local partitioning of the RCFT. Future research should endeavor to explore the item analyses among normal and other clinical samples (e.g., unilateral stroke) on the RCFT. In this regard, items that maximally differentiate RTLE and LTLE groups are defined, and those items that both groups collectively miss or get correct could be excluded. The information on the most frequently missed items would aid in the attempt to identify indicators of lateralized dysfunction. Finally, the use of a pre/postsurgical design analysis may further aid investigations of this nature. Given that the differences in presurgical epilepsy patients was reported by Milner (1975) to be more subtle, comparison of the item list in individuals who received temporal lobectomies may also help to clarify whether the properties of the clinically selected items is able to discern between those with right or left temporal lobe resections.

One limitation of the research using the global/local paradigm is the variety of definitions for the constructs of global and local elements. This criticism is prevalent in much of the literature examining hemispheric specialization. Historically, the terms analytic, and featural have been synonomous with local, whereas holistic, contextual, and configurational have been used interchangeably with the term global. In conclusion, more clearly defined criteria are needed to determine whether dissociation of the global and local elements have clinical utility for detecting right and left hemisphere dysfunction in epilepsy patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We sincerely thank Melissa Deakle, who kindly assisted in re-scoring a subset of the RCFT protocols.

APPENDIX

You have been asked to complete the following questionnaire because of your familiarity and clinical experience with the RCFT. Please rate whether the following items are classified along the dimensions of Global, Ambiguous, or Local. Each item number corresponds to the label number in the Complex Figure. Please rate to what extent the following items are classified along the dimensions of Global or Local based upon the following criteria.

- A global component is defined as one that contributes to the larger layout of a visual stimulus and is necessary to determine its overall configuration (e.g., the “whole”). It is the major organizational framework that is essential in identifying an object as an independent unit.

- A local component refers to a feature or detail that further refines the stimulus, but that is not essential for its identification (e.g., the “part”). Local components are distinct entities, yet are embedded within higher order objects.