INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological evidence consistently shows that exercise is associated with improved cognitive function throughout the lifespan (Ahlskog, Geda, Graff-Radford, & Petersen, Reference Ahlskog, Geda, Graff-Radford and Petersen2011; Geda et al., Reference Geda, Roberts, Knopman, Christianson, Pankratz, Ivnik and Rocca2010; Sofi et al., Reference Sofi, Valecchi, Bacci, Abbate, Gensini, Casini and Macchi2011). Thus, exercise is an attractive potential intervention to reduce the risk of cognitive decline. The mechanisms underlying exercise’s protective role against cognitive decline are not well understood, though there are a few hypotheses. The neurogenesis hypothesis proposes that exercise causes an upregulation of factors called neurotrophins that directly influence neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. The vascular hypothesis arises from the coexistence of both vascular dysfunction and cognitive decline in many patients. The vascular hypothesis states that impairments in vessel function, which can range from deficiencies in the large central arteries to the brain capillaries, affect neuronal health and thus cognitive ability (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2004). This review will focus on the vascular hypothesis.

The brain has a vast vascular network tasked with precisely and adequately supplying blood flow to its 86 billion active neurons. The neurovascular unit (NVU) in the brain coordinates blood flow regulation and includes several cell types: endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons. The majority of information regarding NVU function comes from animal models. These preclinical models suggest that early declines in vascular regulation or NVU function precede neuropathological changes (Iadecola, Reference Iadecola2004; Kisler, Nelson, Montagne, & Zlokovic, Reference Kisler, Nelson, Montagne and Zlokovic2017; Sweeney, Kisler, Montagne, Toga, & Zlokovic, Reference Sweeney, Kisler, Montagne, Toga and Zlokovic2018). The extent to which the mechanisms identified from preclinical models extend to humans is unknown. There is however supporting evidence that early changes in vascular biomarkers and declines in cerebral blood flow occur before common neurological biomarkers such as changes in amyloid-β, tau, or hippocampal atrophy (Albrecht et al., Reference Albrecht, Isenberg, Stradford, Monreal, Sagare, Pachicano and Pa2020; Iturria-Medina et al., Reference Iturria-Medina, Sotero, Toussaint, Mateos-Perez, Evans and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging2016). Thus, an ideal time to initiate interventions in an effort to delay or prevent the onset of cognitive decline is midlife, when age-related declines in vascular regulation are emerging, and the neuropathological burden is low. Because exercise is considered protective against age-related vascular dysfunction, exercise may therefore reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia through its beneficial effect on the systemic and cerebral vasculature.

Lifestyle interventions are promising for reducing age-related morbidity and mortality. Aerobic exercise interventions have been shown to improve vascular function in the large central arteries and in the peripheral circulation (Tanaka, Reference Tanaka2019), but the extent to which this translates to the cerebral circulation, influences neuronal function, or impacts cognition is unclear. The purpose of this review is to discuss the effect of exercise on the function of the large central arteries supplying the brain and the cerebral circulation, as well as to discuss potential physiological mechanisms and considerations underlying the association between exercise and cognition within the context of primary aging.

Age-Associated Changes in Structure and Function of Large Central Arteries

With advancing age, there are alterations in structure and function of the central and peripheral arteries. The structural properties of arteries begin to change with age, as evidenced by vessel wall thickening (Tanaka, Dinenno, Monahan, DeSouza, & Seals, Reference Tanaka, Dinenno, Monahan, DeSouza and Seals2001), increased collagen content (Sun, Reference Sun2015), vascular calcification (Lee & Oh, Reference Lee and Oh2010), deposition of advanced glycation end products (Lee & Oh, Reference Lee and Oh2010), and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (Kohn, Lampi, & Reinhart-King, Reference Kohn, Lampi and Reinhart-King2015). Taken together, these maladaptive changes in arterial structure contribute to an increase in large artery stiffness as evidenced by stiffening of the ascending and descending aorta, as well as the carotid arteries (Thijssen, Carter, & Green, Reference Thijssen, Carter and Green2016; X. Xu et al., Reference Xu, Wang, Ren, Hu, Greenberg, Chen and Jin2017).

Because the large central arteries supply the brain with blood flow, alterations in structure and function of the large central arteries can influence hemodynamics in the cerebral circulation (de Roos, van der Grond, Mitchell, & Westenberg, Reference de Roos, van der Grond, Mitchell and Westenberg2017). Indeed, stiffening of the large central arteries is associated with reduced cerebral blood flow (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Xu, Rodrigue, Kennedy, Cheng, Flicker and Park2011; Tomoto, Riley, Turner, Zhang, & Tarumi, Reference Tomoto, Riley, Turner, Zhang and Tarumi2020) and consequently hypoperfusion of the brain (Yang, Sun, Lu, Leak, & Zhang, Reference Yang, Sun, Lu, Leak and Zhang2017). This is evident in both animal and human models. For example, in an experimental mice model, inducing calcification predictably altered the structure and function of the carotid artery and caused detrimental hemodynamic changes in the cerebral circulation, as well as hippocampal neurodegeneration (Sadekova, Vallerand, Guevara, Lesage, & Girouard, Reference Sadekova, Vallerand, Guevara, Lesage and Girouard2013). Increased carotid arterial stiffness in mice is associated with decreased resting cerebral blood flow, a disrupted blood–brain barrier, and impaired neurovascular coupling and cerebral autoregulation (Muhire et al., Reference Muhire, Iulita, Vallerand, Youwakim, Gratuze, Petry and Girouard2019).

In humans, detrimental hemodynamic changes in the cerebral circulation may manifest as an increase in cerebral pulsatility (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2008), elevated cerebrovascular resistance, and lower cerebrovascular conductance. Cerebral pulsatility increases with age (Pase, Grima, Stough, Scholey, & Pipingas, Reference Pase, Grima, Stough, Scholey and Pipingas2014) and is associated with central arterial stiffness (T. Y. Xu et al., Reference Xu, Staessen, Wei, Xu, Li, Fan and Li2012). Indeed, large cohort studies have demonstrated associations between arterial stiffness and cerebral pulsatility (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, van Buchem, Sigurdsson, Gotal, Jonsdottir, Kjartansson and Launer2011). Additionally, higher arterial stiffness is associated with greater cerebrovascular resistance (Robertson, Tessmer, & Hughson, Reference Robertson, Tessmer and Hughson2010) and lower cerebrovascular conductance (Jaruchart, Suwanwela, Tanaka, & Suksom, Reference Jaruchart, Suwanwela, Tanaka and Suksom2016). Cerebral pulsatility of the middle cerebral artery is associated with central and brachial pulse pressure (T. Y. Xu et al., Reference Xu, Staessen, Wei, Xu, Li, Fan and Li2012). In patients with leukoaraiosis, cerebral pulsatility of the middle cerebral artery is associated with aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Simoni, Mazzucco, Kuker, Schulz and Rothwell2012). Thus, impaired dampening of pulsatile flow caused by arterial stiffness may lead to greater transmission of pressure pulsatility to the cerebral circulation.

Unfavorable changes in large artery stiffness are associated with elevated cerebral pulsatility which could lead to impaired vascular endothelial function. Impaired vascular endothelial function is the diminished ability of the endothelial layer of the blood vessels to respond to vasoactive substances and regulate blood flow (Seals, Jablonski, & Donato, Reference Seals, Jablonski and Donato2011). Higher arterial stiffness, measured by aortic pulse wave velocity, is associated with impaired endothelial function (assessed by flow-mediated dilation) (McEniery et al., Reference McEniery, Wallace, Mackenzie, McDonnell, Yasmin, Newby and Wilkinson2006). In addition, elevated central and peripheral pulse pressure is associated with impaired endothelial function (McEniery et al., Reference McEniery, Wallace, Mackenzie, McDonnell, Yasmin, Newby and Wilkinson2006; Nigam, Mitchell, Lambert, & Tardif, Reference Nigam, Mitchell, Lambert and Tardif2003). Therefore, stiffening of central arteries and elevated pulse pressure could lead to changes in the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature. In the cerebral circulation, increased pulse pressure in an experimental model led to hypertrophy of cerebral arterioles and vascular remodeling (Baumbach, Reference Baumbach1996). The study by Baumbach et al. supports the idea that an increase in transmission of pulsatile blood flow (i.e. pulse pressure) to the peripheral and cerebral circulations results in vascular endothelial damage and impaired endothelial function (Baumbach, Reference Baumbach1996; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2008; Thorin-Trescases et al., Reference Thorin-Trescases, de Montgolfier, Pincon, Raignault, Caland, Labbe and Thorin2018).

Aging is also associated with systemic endothelial dysfunction, as measured by endothelium-dependent dilation in the coronary arteries (Egashira et al., Reference Egashira, Inou, Hirooka, Kai, Sugimachi, Suzuki and Takeshita1993) and peripheral arteries (Gerhard, Roddy, Creager, & Creager, Reference Gerhard, Roddy, Creager and Creager1996). Multiple factors are associated with the age-related decrease in systemic endothelial function including both a reduction in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator (Taddei et al., Reference Taddei, Virdis, Ghiadoni, Salvetti, Bernini, Magagna and Salvetti2001), and an increase in the production of endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor (Thijssen et al., Reference Thijssen, Carter and Green2016; Thijssen, Rongen, van Dijk, Smits, & Hopman, Reference Thijssen, Rongen, van Dijk, Smits and Hopman2007). Similarly, age-related increases in large artery stiffness and cerebral pulsatility likely impact vascular endothelial function in the cerebral circulation (Thorin-Trescases et al., Reference Thorin-Trescases, de Montgolfier, Pincon, Raignault, Caland, Labbe and Thorin2018; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Henson, Reihl, Morgan, Dobson, Nielson and Donato2015), although mechanistic data in humans are lacking. For more information on age-related changes in peripheral vascular function, there are many excellent reviews available (de Roos et al., Reference de Roos, van der Grond, Mitchell and Westenberg2017; Seals et al., Reference Seals, Jablonski and Donato2011; Thijssen et al., Reference Thijssen, Carter and Green2016; X. Xu et al., Reference Xu, Wang, Ren, Hu, Greenberg, Chen and Jin2017). Collectively, changes in the structure and function of central and peripheral arteries contribute to stiffening of the large central arteries and unfavorable alterations in cerebrovascular hemodynamics which may increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

Age-Related Changes in Vascular Function Influence Brain Health

The transmission of highly pulsatile pressure and flow to the microvasculature has been linked with tissue and organ damage (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2008). Because the brain and kidneys are organs with high blood flow and low impedance, the microcirculation within these organ systems is particularly susceptible to damage due to age-related changes in arterial structure (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2008; O’Rourke & Hashimoto, Reference O’Rourke and Hashimoto2007). The idea that elevated arterial stiffness results in cerebrovascular damage and structural remodeling in the brain leading to impaired function is supported by human and clinical evidence (de Roos et al., Reference de Roos, van der Grond, Mitchell and Westenberg2017). For example, elevated central arterial stiffness has been associated with increased white matter hyperintensities in healthy non-hypertensive middle-aged women (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Harvey, Zuk, Lundt, Lesnick, Gunter and Kantarci2017), and adults with cognitive complaints (Kearney-Schwartz et al., Reference Kearney-Schwartz, Rossignol, Bracard, Felblinger, Fay, Boivin and Zannad2009). In addition, arterial stiffness is associated with cerebral microbleeds (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Mitchell, Bots, Sigurdsson, Harris, Garcia and Launer2015), cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) (Zhai et al., Reference Zhai, Ye, Chen, Ding, Han, Yang and Zhu2018), and lower brain volume (Palta et al., Reference Palta, Sharrett, Wei, Meyer, Kucharska-Newton, Power and Heiss2019). Importantly, these changes in brain structure may be mediating factors amongst the relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function, as shown in large clinical studies (Elias et al., Reference Elias, Robbins, Budge, Abhayaratna, Dore and Elias2009; Palta et al., Reference Palta, Sharrett, Wei, Meyer, Kucharska-Newton, Power and Heiss2019; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Sutton-Tyrrell, Rosano, Boudreau, Hardy, Simonsick and Newman2011).

Alterations in vascular structure and function occur in both the large and small intracranial vessels. CSVD is often used to refer to the disease of the cerebral microvessels. The most common diagnostic method of CSVD is the appearance of white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, which are areas denoting leukoaraiosis (Sargurupremraj et al., Reference Sargurupremraj, Suzuki, Jian, Sarnowski, Evans, Bis and Debette2020). CSVD has been associated with altered cerebral hemodynamics (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Atwi, Kostoglou, Verhoeff, Oh, Mitsis and MacIntosh2019) and an increased risk of cognitive impairment (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Wolters, Darweesh, Vernooij, de Wolf, Ikram and Hofman2018). The relationship between CSVD and dementia has been the subject of many recent reviews and meta-analyses; however, increases in arterial stiffness and alterations in cerebral blood flow may precede the diagnosis of CSVD or CSVD related pathologies (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Thrippleton, Makin, Marshall, Geerlings, de Craen and Wardlaw2016; van Sloten et al., Reference van Sloten, Protogerou, Henry, Schram, Launer and Stehouwer2015). While arterial stiffness is associated with structural changes in the brain in patients with CSVD, this review will focus on alterations of vascular function associated with primary aging in individuals without established CSVD.

Regular Exercise and Central Arterial Stiffness

Exercise has the ability to affect both the structure and function of the central elastic arteries; however, its effects are dependent on numerous factors, such as mode, volume, and frequency of exercise performed. Studies examining the effect of exercise on central arterial stiffness in middle-aged and older adults have largely shown beneficial results, such that central arterial stiffness is lower in exercise trained middle-aged and older adults and is inversely associated with cardiorespiratory fitness or VO2max (Tanaka, DeSouza, & Seals, Reference Tanaka, DeSouza and Seals1998; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Dinenno, Monahan, Clevenger, DeSouza and Seals2000; Vaitkevicius et al., Reference Vaitkevicius, Fleg, Engel, O’Connor, Wright, Lakatta and Lakatta1993). Furthermore, there is evidence that elevated levels of arterial stiffness can be reversed through short-term moderate-intensity aerobic exercise interventions in this population (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Dinenno, Monahan, Clevenger, DeSouza and Seals2000; Yoshizawa et al., Reference Yoshizawa, Maeda, Miyaki, Misono, Saito, Tanabe and Ajisaka2009). However, there may be a threshold of exercise volume necessary for the prevention of age-associated changes. Recently, Shibata et al. have reported 4–5 days per week of at least 30 min of aerobic exercise is required to prevent age-associated changes in central arterial stiffness (Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Fujimoto, Hastings, Carrick-Ranson, Bhella, Hearon and Levine2018). This idea of an exercise volume threshold is consistent with earlier publications showing lower levels of central arterial stiffness in endurance trained older men (performing vigorous aerobic exercise at least 5 days per week and competing in local running races), but not recreationally active older men (light to moderate exercise 3 days per week) when compared with their sedentary peers (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Dinenno, Monahan, Clevenger, DeSouza and Seals2000). A recent meta-analysis by Ashor et al. also concluded that higher intensity aerobic exercise resulted in lower central arterial stiffness in adults (Ashor, Lara, Siervo, Celis-Morales, & Mathers, Reference Ashor, Lara, Siervo, Celis-Morales and Mathers2014). Importantly, not all modes of exercise appear to have the same effects on central arterial stiffness. Most studies focus on aerobic exercises such as walking, running, or cycling, as the primary exercise mode when evaluating the impact on arterial stiffness. Healthy adults who participate in other modes of aerobic exercise, such as swimming or rowing, also show reduced levels of age-related arterial stiffness compared with sedentary adults (Cook et al., Reference Cook, DeVan, Schleifer, Anton, Cortez-Cooper and Tanaka2006; Nualnim, Barnes, Tarumi, Renzi, & Tanaka, Reference Nualnim, Barnes, Tarumi, Renzi and Tanaka2011). In contrast, adults who regularly participate in high-intensity resistance exercise paradoxically have higher arterial stiffness (Miyachi et al., Reference Miyachi, Donato, Yamamoto, Takahashi, Gates, Moreau and Tanaka2003). Furthermore, high-intensity progressive resistance training interventions 3–4 days per week (near 80% one repetition maximum) have been shown to increase central arterial stiffness in both men (Miyachi et al., Reference Miyachi, Kawano, Sugawara, Takahashi, Hayashi, Yamazaki and Tanaka2004) and women (Cortez-Cooper et al., Reference Cortez-Cooper, DeVan, Anton, Farrar, Beckwith, Todd and Tanaka2005). Although the underlying mechanisms are not clear, high-intensity resistance exercise produces large fluctuations in blood pressure during the activity, which over time can alter the load-bearing properties of the artery (Miyachi, Reference Miyachi2013). However, this increase in arterial stiffness only appears in younger adults or when the intervention includes high-intensity resistance exercise, with studies using moderate intensity resistance training showing no effect on central arterial stiffness (Ashor et al., Reference Ashor, Lara, Siervo, Celis-Morales and Mathers2014; Miyachi, Reference Miyachi2013). Therefore, both exercise volume and modality of exercise influence arterial stiffness in the large central arteries.

Aging and Vascular Function of the Cerebral Circulation

This review has largely focused on the function of the large central arteries which supply the brain. From the large central arteries, blood travels into the intracranial vessels and through the Circle of Willis before it reaches its destination at the neuronal tissue. Blood flow to the neuronal tissue is regulated by the smaller brain blood vessels, astrocytes, pericytes, and neurons that form the NVU to help control oxygen delivery to match increases in metabolic activity in the brain. The vascular smooth muscle cells at the level of the arterioles help to control the amount of blood flowing into the capillary bed and the NVU precisely dictates the regional distribution of blood flow. Thus, the structure and function throughout the entire brain’s vascular network, from the large central blood vessels to the pericytes in the brain capillaries, are essential for maintaining brain health (L. S. Brown et al., Reference Brown, Foster, Courtney, King, Howells and Sutherland2019; Iadecola, Reference Iadecola2017; Kisler et al., Reference Kisler, Nelson, Montagne and Zlokovic2017; Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Kisler, Montagne, Toga and Zlokovic2018).

Many studies suggest that reduced vessel function in the cerebral circulation (or cerebral vascular function) is part of the etiology of cognitive decline. For example, individuals with lower cerebral blood flow are at a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease (Wolters et al., Reference Wolters, Zonneveld, Hofman, van der Lugt, Koudstaal and Vernooij2017). In addition, Alzheimer’s disease patients demonstrate early vascular dysregulation (Arvanitakis, Capuano, Leurgans, Bennett, & Schneider, Reference Arvanitakis, Capuano, Leurgans, Bennett and Schneider2016; Iturria-Medina et al., Reference Iturria-Medina, Sotero, Toussaint, Mateos-Perez, Evans and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging2016; Laing et al., Reference Laing, Simoes, Baena-Caldas, Lao, Kothiya and Igwe2020; Montagne et al., Reference Montagne, Nation, Pa, Sweeney, Toga and Zlokovic2016), reduced cerebrovascular function (Silvestrini et al., Reference Silvestrini, Pasqualetti, Baruffaldi, Bartolini, Handouk, Matteis and Vernieri2006), and post-mortem evaluations show both vascular pathology and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Toledo et al., Reference Toledo, Arnold, Raible, Brettschneider, Xie, Grossman and Trojanowski2013). Furthermore, early vascular-tau associations may be exacerbated in the presence of amyloid-β, suggesting a synergistic effect of vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies (Albrecht et al., Reference Albrecht, Isenberg, Stradford, Monreal, Sagare, Pachicano and Pa2020). Thus, evaluating vascular health and cerebral vascular function may be important in understanding the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease. This may be especially critical in prodromal stages of cognitive decline when neuropathology and cognitive symptoms are below detection thresholds.

Vascular function in the cerebral vessels in humans can be assessed by measuring global or regional cerebral perfusion at rest or assessing the blood flow response to a vasoactive stimulus. Several vasoactive stimuli are more frequently used to assess cerebral vascular function, including alterations in arterial blood gases (O2 and CO2), acetazolamide, or neuronal stimulation using visual perturbations or cognitively challenging activities (Fierstra et al., Reference Fierstra, Sobczyk, Battisti-Charbonney, Mandell, Poublanc, Crawley and Fisher2013). The magnitude of the blood flow response to these stimuli determines cerebral vasoreactivity, with higher vasoreactivity to a vasodilatory stimulus indicating healthier cerebral blood vessels.

While there are an increasing number of studies that include cerebral vascular function, the relationship between advancing age and cerebral vascular function is still not well understood. One reason for this is because of the inherent difficulty of imaging blood flow through the skull. Common techniques attempt to measure blood flow through the larger intracranial vessels include ultrasonography or 2D, 3D, or 4D phase contrast MRI. Other techniques to measure bulk flow, or infer microvascular flow, include measurement of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration with near-infrared spectroscopy, estimation of cerebral blood flow using an invasive tracer such as quantitative [15O] water brain positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, measurement of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin using blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) imaging, MRI, and estimating cerebral blood flow with an intrinsic tracer (radiofrequency labeled arterial blood) via arterial spin labeling (ASL) techniques. PET and MRI techniques can measure global or regional cerebral blood flow or blood flow through the large intracranial vessels. However, MRI is not always available and scanning sequences cause a temporal constraint. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound was developed in the early 1980s and has become a popular technique to measure brain blood flow because it allows for the measurement of blood velocity through large intracranial vessels with high temporal resolution to assess rapid changes in the cerebral circulation. It also allows for screening of participants who could not safely undergo MRI scans and permits experimental measurements that would be restricted in an MRI. However, TCD lacks spatial resolution, can only image one vessel at a time, and measures velocity rather than flow. The difference between blood velocity and blood flow is an important distinction, especially in the instance where a stimulus may change diameter of the vessel of interest. Currently, there is no gold standard technique to measure cerebral blood flow and each technique has strengths and weaknesses (see review Tymko, Ainslie, & Smith, Reference Tymko, Ainslie and Smith2018).

Using the TCD technique, studies have shown that primary aging, in the absence of cardiovascular risk factors, is associated with lower cerebral vasoreactivity (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, de Leeuw, den Heijer, Koudstaal, Hofman and Breteler2004; Barnes, Schmidt, Nicholson, & Joyner, Reference Barnes, Schmidt, Nicholson and Joyner2012; Kastrup, Dichgans, Niemeier, & Schabet, Reference Kastrup, Dichgans, Niemeier and Schabet1998), indicating a reduction in cerebral blood vessel health. However, there are also studies using TCD that show no effect of age on cerebral vasoreactivity (Galvin et al., Reference Galvin, Celi, Thomas, Clendon, Galvin, Bunton and Ainslie2010; Madureira, Castro, & Azevedo, Reference Madureira, Castro and Azevedo2017; Miller, Howery, Harvey, Eldridge, & Barnes, Reference Miller, Howery, Harvey, Eldridge and Barnes2018) and suggest preserved cerebral vascular function (see additional review by Hoiland, Fisher, & Ainslie, Reference Hoiland, Fisher and Ainslie2019). These contrasting results may be due to several methodological factors (as discussed above) that may mask the effects of primary aging, including the influence of arterial blood pressure, body posture during data collection, use and timing of medication, or other experimental procedures used to deliver a vasoactive stimulus. For example, arterial blood pressure is important for the interpretation of cerebral blood flow because an increase in perfusion pressure will drive an increase in cerebral blood flow. This is in part blunted if cerebral autoregulation is intact, but there is a complex relationship between arterial blood pressure and cerebral blood flow across a range of physiological conditions (Tzeng et al., Reference Tzeng, Ainslie, Cooke, Peebles, Willie, MacRae and Rickards2012). Importantly, physiological factors in the aforementioned studies may also influence the conflicting results, including whether or not the study participants had high cardiorespiratory fitness or were endurance trained (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Marley, Brugniaux, Hodson, New, Ogoh and Ainslie2013; Barnes, Taylor, Kluck, Johnson, & Joyner, Reference Barnes, Taylor, Kluck, Johnson and Joyner2013; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Harvey, Eldridge and Barnes2018; Murrell et al., Reference Murrell, Cotter, Thomas, Lucas, Williams and Ainslie2012; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Yezhuvath, Tseng, Liu, Levine, Zhang and Lu2013). In order to determine age-related changes in cerebral vasoreactivity in healthy adults vs. pathological declines in cerebral vasoreactivity, future studies should provide sufficient characterization of participants and consider experimental factors such as body posture, simultaneous arterial blood pressure measurements, medication or hormone use, and consider the imaging modality best suited for the research question.

One methodological factor warrants additional discussion because of its impact on the effect of aging on cerebral vasoreactivity. TCD ultrasound, used by previous studies to evaluate cerebral vasoreactivity, has the limitation of only measuring blood velocity and not blood flow, as it cannot assess blood vessel diameter. Using MRI to measure the middle cerebral artery response to vasoactive stimuli, recent studies have shown that the middle cerebral artery vasodilates under vasoactive conditions like elevated CO2 (Coverdale, Gati, Opalevych, Perrotta, & Shoemaker, Reference Coverdale, Gati, Opalevych, Perrotta and Shoemaker2014; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Rivera-Rivera, Johnson, Rowley, Wieben and Barnes2019; Verbree et al., Reference Verbree, Bronzwaer, Ghariq, Versluis, Daemen, van Buchem and van Osch2014). This would suggest that changes in blood velocity obtained by TCD may not accurately represent changes in blood flow during a vasoactive stimulus.

In order to address this limitation of TCD, our group has utilized 4D flow MRI which has the advantage of measuring structural and flow data of large intracranial vessels in the same scan acquisition. This technique has been validated at rest (Rivera-Rivera et al., Reference Rivera-Rivera, Turski, Johnson, Hoffman, Berman, Kilgas and Wieben2016; Schrauben et al., Reference Schrauben, Johnson, Huston, Del Rio, Reeder, Field and Wieben2014) and during hypercapnia (Mikhail Kellawan et al., Reference Mikhail Kellawan, Harrell, Schrauben, Hoffman, Roldan-Alzate, Schrage and Wieben2016) to measure blood flow in 11 large intracranial vessels. When these changes in blood vessel diameter are evaluated with changes in blood velocity simultaneously (via 4D flow MRI), we have shown reduced cerebral vasoreactivity in healthy older adults, compared with young adults (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Rivera-Rivera, Johnson, Rowley, Wieben and Barnes2019). This is in contrast to our previous work in healthy older adults using TCD ultrasound, when the participant characteristics were well-matched with healthy young adults (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Harvey, Eldridge and Barnes2018). When using 4D flow MRI to measure the magnitude of middle cerebral artery diameter changes in response to CO2, vasodilation was only significant in young adults (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Rivera-Rivera, Johnson, Rowley, Wieben and Barnes2019). In other words, the middle cerebral artery (and potentially other intracranial blood vessels) diameter increases in response to a vasoactive stimulus, but only in young healthy adults. These age-associated differences could potentially explain some of the conflicting results for cerebral vasoreactivity. However, it is also unknown if factors such as cardiorespiratory fitness or habitual endurance training influence the magnitude of cerebral artery dilation in the presence of a vasoactive stimulus like CO2. Our hypothesis is that cardiorespiratory fitness is positively associated with the magnitude of middle cerebral artery dilation (based on our unpublished observations), but this has not been systematically tested. More research is necessary to determine how habitual exercise and cardiorespiratory fitness may mediate the effects of aging on peripheral and cerebral vascular function.

Exercise and the Cerebral Circulation

The impact of aging on cerebral vasoreactivity could be influenced by habitual aerobic exercise, and there are conflicting reports in the literature. Our previous work using TCD ultrasound has shown that VO2max is associated with cerebral vasoreactivity in healthy older adults, but are not correlated in young adults (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Taylor, Kluck, Johnson and Joyner2013). Additionally, while our previous studies have shown lower cerebral vasoreactivity in healthy older adults, compared with younger adults (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Schmidt, Nicholson and Joyner2012), we reported no age-related difference in cerebral vasoreactivity when including only habitually exercising adults (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Howery, Harvey, Eldridge and Barnes2018). Other groups have also examined the influence of habitual exercise or VO2max on cerebral vasoreactivity using TCD ultrasound and have reported either no association with exercise (Braz, Fluck, Lip, Lundby, & Fisher, Reference Braz, Fluck, Lip, Lundby and Fisher2017; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Tarumi, Tseng, Palmer, Levine and Zhang2013) or a positive association between VO2max and cerebral vasoreactivity in young and older men (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Marley, Brugniaux, Hodson, New, Ogoh and Ainslie2013). Studies that have examined the effect of exercise on the cerebral circulation using MRI methods such as ASL or BOLD have added to the conflicting literature on the relationship between exercise and cerebral blood flow and cerebral vascular function. These studies have shown reduced cerebral vasoreactivity in highly trained Master’s athletes compared with sedentary controls (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Yezhuvath, Tseng, Liu, Levine, Zhang and Lu2013), and conflicting relationships between VO2max and cerebral vasoreactivity (Furby, Warnert, Marley, Bailey, & Wise, Reference Furby, Warnert, Marley, Bailey and Wise2019; Intzandt et al., Reference Intzandt, Sabra, Foster, Desjardins-Crepeau, Hoge, Steele and Gauthier2020).

While we have focused on the impact of exercise on cerebral vascular function, there are studies investigating the effect of exercise on resting cerebral perfusion. Again, there are conflicting results in the literature with some studies reporting an increase in regional cerebral perfusion (Alfini, Weiss, Nielson, Verber, & Smith, Reference Alfini, Weiss, Nielson, Verber and Smith2019; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Aslan, Spence, Defina, Keebler, Didehbani and Lu2013; Guadagni et al., Reference Guadagni, Drogos, Tyndall, Davenport, Anderson, Eskes and Poulin2020; Kleinloog et al., Reference Kleinloog, Mensink, Ivanov, Adam, Uludag and Joris2019) or no effect of exercise training on resting cerebral blood flow (Flodin, Jonasson, Riklund, Nyberg, & Boraxbekk, Reference Flodin, Jonasson, Riklund, Nyberg and Boraxbekk2017; van der Kleij et al., Reference van der Kleij, Petersen, Siebner, Hendrikse, Frederiksen, Sobol and Garde2018).

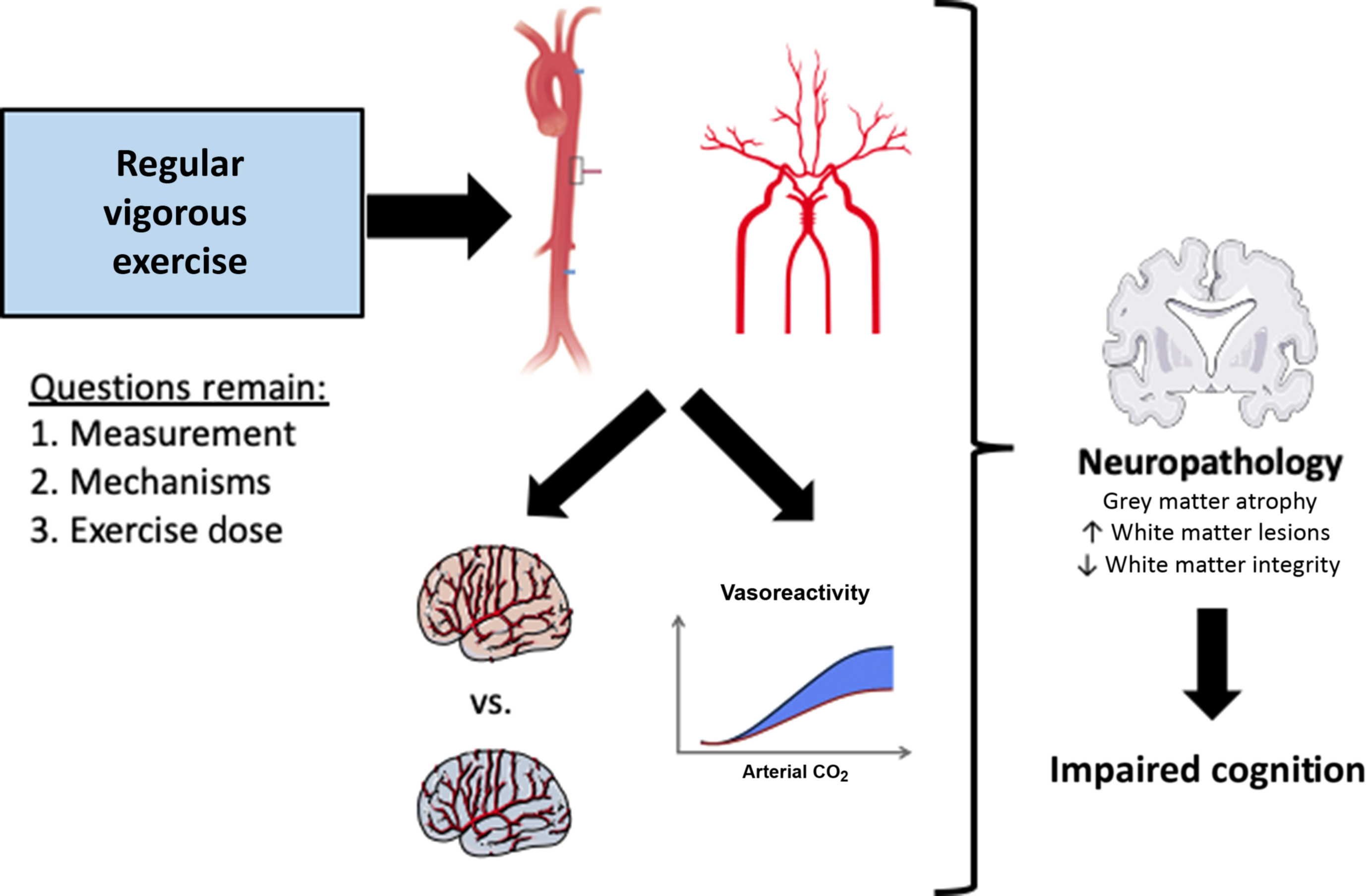

Collectively, the majority of studies have found a neutral or favorable effect of exercise on cerebral vasoreactivity, cerebral perfusion, and thus, cerebral vascular function (Figure 1). However, longitudinal or intervention studies are necessary to determine the influence of habitual exercise on cerebral vasoreactivity, as the conflicting evidence may be due to: 1) methodological factors such as using TCD ultrasound vs. MRI and the method of delivering the vasoactive stimulus; 2) study design, particularly the lack of women participants in earlier studies; or 3) physiological effects of exercise that are unrelated to vascular health, such as altered chemoreceptor or baroreceptor sensitivity.

Fig. 1. Conceptual summary of how regular vigorous aerobic exercise may impact the central arterial stiffness, cerebral vascular function, and cerebral perfusion, with implications for future risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. This figure was created in part with modified Servier Medical Art templates, which are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: https://smart.servier.com.

Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Benefit of Exercise

The mechanisms underlying exercise’s protective role against cognitive decline are not well understood. A single bout of exercise leads to considerable changes in metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune pathways (Contrepois et al., Reference Contrepois, Wu, Moneghetti, Hornburg, Ahadi, Tsai and Snyder2020; Egan & Zierath, Reference Egan and Zierath2013; Pedersen & Hoffman-Goetz, Reference Pedersen and Hoffman-Goetz2000; Whyte & Laughlin, Reference Whyte and Laughlin2010). The effects of habitual exercise, as well as the mode, frequency, and intensity of exercise needed to invoke the favorable effects of exercise on brain health remain unclear. In addition, there are other favorable effects of exercise that will not be covered in this review. For example, psychological benefits of both acute and chronic exercise may, over the long term, affect cognition independent of vascular adaptations. Diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Cohen, Edmondson, & Kronish, Reference Cohen, Edmondson and Kronish2015) and dementia (Kuring, Mathias, & Ward, Reference Kuring, Mathias and Ward2018). However, acute exercise and exercise training can reduce psychosocial stress (O’Keefe, O’Keefe, & Lavie, Reference O’Keefe, O’Keefe and Lavie2019), which could indirectly benefit cognitive function. Another example of the favorable adaptations of exercise is the effect of learning or cognitive activity associated with exercise training, particularly when training for many competitive sports. Again, it is difficult to tease out the physiological effects of movement from the neural engagement associated with learning the movement or novel activity. The remainder of this section will focus on the direct physiological mechanisms underlying the benefits of exercise.

In a breakthrough study in 1999, Van Praag and colleagues described the development of new neurons in the hippocampus in mice that were exposed to wheel running (van Praag, Christie, Sejnowski, & Gage, Reference van Praag, Christie, Sejnowski and Gage1999; van Praag, Kempermann, & Gage, Reference van Praag, Kempermann and Gage1999). This study is associated with the neurogenesis hypothesis, suggesting that exercise causes an upregulation of factors called neurotrophins that directly influence neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Indeed, exercise has also been shown to upregulate neurotrophins in humans, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Church et al., Reference Church, Hoffman, Mangine, Jajtner, Townsend, Beyer and Stout2016; P. Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Brassard, Adser, Pedersen, Leick, Hart and Pilegaard2009). In humans, positive associations between greater amounts of physical activity and hippocampal volume have been reported (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Prakash, Voss, Chaddock, Hu, Morris and Kramer2009; Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Raji, Lopez, Becker, Rosano, Newman and Kuller2010). In addition to BDNF, other signaling molecules have been identified though the mechanisms underlying the cognitive benefits of exercise are still being explored. For additional reviews on this topic, see Cotman, Berchtold, & Christie, Reference Cotman, Berchtold and Christie2007; Stillman, Esteban-Cornejo, Brown, Bender, & Erickson, Reference Stillman, Esteban-Cornejo, Brown, Bender and Erickson2020; Vivar & van Praag, Reference Vivar and van Praag2017.

Other than BDNF, upregulation of factors that influence or regulate neural and blood vessel survival and growth, such as insulin-like growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor, likely contributes to the beneficial effect of exercise (Cotman et al., Reference Cotman, Berchtold and Christie2007; Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Hillman, Stillman, Ballard, Bloodgood and Conroy2019; Liu & Nusslock, Reference Liu and Nusslock2018; Stillman et al., Reference Stillman, Esteban-Cornejo, Brown, Bender and Erickson2020). Other myokines, or cytokines synthesized and released by contracting skeletal muscle such as cathepsin B and irisin, may integrate with other growth factors or work via separate pathways to preserve brain vasculature and neural tissue, though these mechanisms are only beginning to be explored (Severinsen & Pedersen, Reference Severinsen and Pedersen2020). The exact mechanisms underlying the favorable effects of exercise on brain health remain unclear. Here, we briefly review considerations and potential mechanisms that may mediate the effect of exercise specifically on the cerebral circulation.

When investigating the effect of exercise on resting cerebral perfusion, studies have reported no effect of 16 weeks of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise interventions on cerebral blood flow in patients with established neurodegenerative disease (van der Kleij et al., Reference van der Kleij, Petersen, Siebner, Hendrikse, Frederiksen, Sobol and Garde2018). Similarly, a study in middle-aged and older healthy adults reports no effect of a low to moderate intensity exercise intervention on cerebral blood flow (Flodin et al., Reference Flodin, Jonasson, Riklund, Nyberg and Boraxbekk2017). In contrast, Chapman et al. reported an increase in regional cerebral perfusion in middle-aged and older healthy adults with a more intense, structured exercise intervention, representing a greater overall exercise dose (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Aslan, Spence, Defina, Keebler, Didehbani and Lu2013). Another study by Kleinloog et al. reported an increase in resting cerebral blood flow of the frontal cortex after a supervised, progressive aerobic exercise training protocol for 8 weeks in previously sedentary healthy older men aged 60–70 years (Kleinloog et al., Reference Kleinloog, Mensink, Ivanov, Adam, Uludag and Joris2019). Similarly, Poulin and colleagues recruited healthy older participants to undergo a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention progressively increasing the exercise intensity. Post-intervention, Guadagni et al. reported increased resting cerebral blood velocity, as well as improved measures of cerebral vascular function (Guadagni et al., Reference Guadagni, Drogos, Tyndall, Davenport, Anderson, Eskes and Poulin2020). Collectively, these studies suggest that exercise of a sufficient dose and duration of training may influence cerebral blood flow characteristics in healthy adults, at least during the preclinical phase of disease.

As previously discussed in this review, habitual exercise may reduce central arterial stiffness, which corresponds to greater compliance of the large central arteries such as the aorta. It is possible that the beneficial effects of exercise on vascular structure may extend further than large central vessels and into the intracranial vessels. Using diffuse optical imaging to examine cerebral pulsatile waveforms in older adults, cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with greater arterial compliance of the vessels in frontoparietal brain regions (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Low, Kong, Fletcher, Zimmerman, Maclin and Fabiani2017). In young adults, cardiorespiratory fitness was positively associated with cerebral artery compliance (Furby et al., Reference Furby, Warnert, Marley, Bailey and Wise2019). Together, these studies suggest that exercise may improve the vascular structure of both large and small intracranial vessels. As cardiorespiratory fitness is comprised of both genetic and lifestyle factors (i.e. exercise habits), future studies could evaluate if an acute exercise intervention may improve arterial compliance in the cerebral circulation. Ultimately, improved intracranial arterial compliance (or reduced arterial stiffness) could lead to reduced pressure pulsatility in the cerebral microvessels, slowed breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, and better clearing of circulating amyloid-β (Kisler et al., Reference Kisler, Nelson, Montagne and Zlokovic2017; Zhao, Nelson, Betsholtz, & Zlokovic, Reference Zhao, Nelson, Betsholtz and Zlokovic2015; Zlokovic, Reference Zlokovic2011).

Together with improvements in arterial compliance, aerobic exercise improves vascular endothelial function in peripheral blood vessels. In the peripheral circulation, exercise increases NO synthesis, regulation, and signaling, improves prostaglandin-mediated vasodilation, and decreases oxidative stress and inflammation (DeSouza et al., Reference DeSouza, Shapiro, Clevenger, Dinenno, Monahan, Tanaka and Seals2000; Green, Hopman, Padilla, Laughlin, & Thijssen, Reference Green, Hopman, Padilla, Laughlin and Thijssen2017; Seals et al., Reference Seals, Jablonski and Donato2011; Tanaka, Reference Tanaka2019). The endothelial function in the cerebral vessels could benefit from habitual exercise similar to peripheral blood vessels, though mechanistic studies of cerebral vessels in humans are lacking. Animal studies have provided some evidence to suggest exercise-mediated improvements in vascular endothelial function. For example, vigorous aerobic exercise training in rats resulted in higher NO-dependent cerebral vasoreactivity compared to sedentary rats (Arrick, Yang, Li, Cananzi, & Mayhan, Reference Arrick, Yang, Li, Cananzi and Mayhan2014). Furthermore, voluntary wheel running in wild-type mice increased basal cerebral blood flow; however, there was no improvement in cerebral blood flow in mice that were endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) deficient (Endres et al., Reference Endres, Gertz, Lindauer, Katchanov, Schultze, Schrock and Laufs2003). This suggested that improvements in cerebral blood flow are influenced by aerobic exercise-induced increases in vascular shear stress, but dependent on eNOS upregulation. The increase in blood flow during dynamic aerobic exercise increases shear stress which stimulates the eNOS enzyme to rapidly vasodilate the blood vessel (Green, Maiorana, O’Driscoll, & Taylor, Reference Green, Maiorana, O’Driscoll and Taylor2004). Along these lines, voluntary wheel running in mice induces beneficial changes in cerebral arteries, with evidence of larger and more regularly shaped endothelial cell nuclei in the middle cerebral artery (Latimer et al., Reference Latimer, Searcy, Bridges, Brewer, Popovic, Blalock and Porter2011). In humans, postmenopausal women with higher levels of plasma-derived measures of oxidative stress demonstrated reduced cerebrovascular conductance (Pialoux, Brown, Leigh, Friedenreich, & Poulin, Reference Pialoux, Brown, Leigh, Friedenreich and Poulin2009). Additionally, higher cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with lower markers of oxidative stress (Pialoux et al., Reference Pialoux, Brown, Leigh, Friedenreich and Poulin2009). Because oxidative stress can reduce NO bioavailability, reductions in oxidative stress or increased antioxidant pathways may be an underlying mechanism by which habitual exercise improves cerebral blood flow regulation via increased NO bioavailability (Thijssen et al., Reference Thijssen, Carter and Green2016). Another possible mechanism underlying exercise-mediated changes in vasodilatory capacity involves the role of prostaglandins (Nicholson, Vaa, Hesse, Eisenach, & Joyner, Reference Nicholson, Vaa, Hesse, Eisenach and Joyner2009). With our previous work in older adults, we have shown that cyclooxygenase blockade reduces cerebral vasoreactivity (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Schmidt, Nicholson and Joyner2012). In addition, higher cardiorespiratory fitness was positively associated with the magnitude of change in cerebral vasoreactivity after cyclooxygenase blockade (reducing prostaglandins) (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Taylor, Kluck, Johnson and Joyner2013). This suggests that higher cardiorespiratory fitness may upregulate the reliance on prostaglandin-mediated vasodilation in the cerebral vessels (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Taylor, Kluck, Johnson and Joyner2013).

This review largely focused on research detailing the impact of aging and exercise on the cerebral vasculature. However, altered energy metabolism is another factor that impacts neurovascular coupling and improved energy metabolism may contribute to the effect of exercise on the brain (for review see van Praag, Fleshner, Schwartz, & Mattson, Reference van Praag, Fleshner, Schwartz and Mattson2014). Because glucose molecules cannot pass through the blood–brain barrier without a carrier protein, this rate-limiting step in energy metabolism requires the vascular glucose transporter GLUT1. Importantly, GLUT1 is the primary glucose transporter in endothelial cells that make up the blood–brain barrier (Veys et al., Reference Veys, Fan, Ghobrial, Bouche, Garcia-Caballero, Vriens and De Bock2020). In addition, in the cerebral microvessels, the density and distribution of GLUT1 are correlated with regional cerebral glucose utilization (Zeller, Rahner-Welsch, & Kuschinsky, Reference Zeller, Rahner-Welsch and Kuschinsky1997). Transgenic mice overexpressing amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) with GLUT1 deficiency had lower cerebral blood flow, impaired neurovascular coupling, and increased amyloid-β pathology compared with APP mice (Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Nishida, Sagare, Rege, Bell, Perlmutter and Zlokovic2015). This suggests that GLUT1 reductions may be an early modification in the neuropathological processes associated with Alzheimer’s disease. In the human brain, Alzheimer’s disease is associated with reduced glucose transporters in the blood–brain barrier (Kalaria & Harik, Reference Kalaria and Harik1989; Szablewski, Reference Szablewski2017).

In mice, acute aerobic exercise (voluntary wheel running) led to an increase in expression of GLUT1 in the brain (Allen & Messier, Reference Allen and Messier2013). Similarly, regular exercise in mice increased expression of GLUT1 in cardiomyocytes (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jia, Zhang, Yang, Dong, Sun and Ge2020) and the central nervous system (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Wang, Pei, Zhang, Shen, Gao and Chang2019). In addition, upregulation of GLUT1 in the cortex was reported after a single bout of aerobic exercise in rats (Takimoto & Hamada, Reference Takimoto and Hamada2014). Because cerebral hypometabolism is often observed in Alzheimer’s disease, the exercise-mediated upregulation of GLUT1 may contribute to the positive effects of exercise on cognitive and brain health (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Wang, Pei, Zhang, Shen, Gao and Chang2019). It is unknown if similar increases in GLUT1 expression in humans are apparent after an exercise intervention.

Recent research on the glymphatic pathway, a glial-lymphatic system that provides drainage of fluids from brain tissue that was first identified in rodents, suggests that this pathway is also present in humans (M. K. Rasmussen, Mestre, & Nedergaard, Reference Rasmussen, Mestre and Nedergaard2018). Because of the blood–brain barrier and lack of lymphatic vessels in the parenchyma, the brain cannot rely on the vascular lymphatic system to clear metabolic waste like most other organs. Briefly, the glymphatic pathway clears solutes and metabolic waste via a perivascular pathway. This pathway allows exchange between the cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid and appears to be facilitated by astrocytic aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels (Iliff & Nedergaard, Reference Iliff and Nedergaard2013) and arterial pulsations (Mestre et al., Reference Mestre, Tithof, Du, Song, Peng, Sweeney and Kelley2018). Preclinical models show that aging and CSVD may impair glymphatic function due to attenuated periarterial influx of cerebrospinal fluid and impaired exchange between cerebrospinal and interstitial fluid (Kress et al., Reference Kress, Iliff, Xia, Wang, Wei, Zeppenfeld and Nedergaard2014; Mestre et al., Reference Mestre, Tithof, Du, Song, Peng, Sweeney and Kelley2018). In the context of Alzheimer’s disease, AQP4 helps to “drain” extracellular amyloid-β, preventing the deposition of amyloid-β plaques (Iliff & Nedergaard, Reference Iliff and Nedergaard2013). In support of the data from animal models, patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia have reduced tracer clearance compared with controls, indicating impaired glymphatic function, which is increasingly recognized as a key factor in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (de Leon et al., Reference de Leon, Li, Okamura, Tsui, Saint-Louis, Glodzik and Rusinek2017; Ringstad et al., Reference Ringstad, Valnes, Dale, Pripp, Vatnehol, Emblem and Eide2018; Tarasoff-Conway et al., Reference Tarasoff-Conway, Carare, Osorio, Glodzik, Butler, Fieremans and de Leon2015).

An emerging hypothesis is that habitual exercise assists in glymphatic flow to help clear amyloid-β, tau, and other soluble proteins and metabolites. In mice, voluntary running is associated with increased cerebrospinal fluid flow and amyloid-β clearance, indicating enhanced glymphatic function (He et al., Reference He, Liu, Zhang, Liang, Dai, Zeng and Lan2017; von Holstein-Rathlou, Petersen, & Nedergaard, Reference von Holstein-Rathlou, Petersen and Nedergaard2018). Therefore, in addition to the benefits of increased cerebral vascular function, one more advantage of exercise in rodents may be greater clearance of neurotoxic proteins. Yet, the translation of this information to aging humans is unclear. In a study of cognitively normal older healthy adults, those who exceeded exercise guidelines of 7.5 MET-hr/week had higher cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of Aβ42, the isoform of amyloid-β commonly found in brain plaques, compared with non-exercisers, which would suggest enhanced clearance (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Mintun, Fagan, Goate, Bugg, Holtzman and Head2010). A study by Brown et al. reported no difference in cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of Aβ42 between exercise groups, even though amyloid-β deposition in the brain was lower in exercising adults at elevated risk of Alzheimer’s disease (B. M. Brown et al., Reference Brown, Sohrabi, Taddei, Gardener, Rainey-Smith and Peiffer2017). However, a short-term moderate to high-intensity exercise training intervention in patients with Alzheimer’s disease did not change Aβ42, tau, or APP concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (Steen Jensen et al., Reference Steen Jensen, Portelius, Siersma, Hogh, Wermuth, Blennow and Hviid Simonsen2016). Clearly, there are still many questions in this emerging research area regarding whether exercise enhances activity of the glymphatic pathway to reduce neuropathology in the brain.

Collectively, these findings in animals and humans suggest that exercise may: (1) contribute to structural and functional improvements in the large central arteries supplying the brain and the cerebral arteries; (2) upregulate local and systemic factors that impact neurogenesis and vascular function; and (3) improvements may extend throughout the vascular tree, from large intracranial vessels to the cerebral arteries and microvasculature, and to cerebrospinal fluid flow.

Summary

Regular lifelong aerobic exercise is associated with higher cognitive function scores. In order for exercise to be considered a successful intervention to reduce the risk or delay the onset of cognitive decline, more research is necessary. Because of the time delay between the initial pathological changes and the onset of cognitive symptoms, other variables are necessary to use as targets for evaluating the success of exercise interventions on brain health. These variables may include arterial stiffness of the extracranial vessels, cerebral artery vasoreactivity, or cerebral pulsatility. Arterial stiffening in the large central arteries is associated with indicators of declining brain health and is improved by regular exercise. Therefore, the reported beneficial effects of exercise on arterial stiffness may also indicate favorable changes in the brain. Measuring cerebral vascular function offers a promising way to assess vascular health in the cerebral circulation and could be used as an early biomarker. Although there is evidence that exercise positively impacts cerebral vascular function, more research is necessary to optimize experimental protocols and address methodological limitations and physiological considerations. Additionally, more information is necessary on the systemic and local mechanisms, the mode of exercise, and the appropriate exercise “dose” for brain health. Despite the need for more research, exercise nevertheless remains an appealing lifestyle intervention to reduce the risk of cognitive decline. Understanding the impact of exercise on vascular function in the cerebral circulation is important for understanding the association between exercise and brain health and may inform future intervention studies that seek to improve cognition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Anna Howery and Kelli England for their critical review of this manuscript.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association 17-499398 (JNB) and the National Institutes of Health grants NS117746 (JNB) and T32 HL007936 (KBM).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.