INTRODUCTION

HIV disease is associated with elevated immune system activation and persistent inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS) (Hong & Banks, Reference Hong and Banks2015; Letendre, Reference Letendre2011). Neuroinflammatory responses persist despite virally suppressive antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Vera et al., Reference Vera, Guo, Cole, Boasso, Greathead, Kelleher and Gunn2016), and are likely major contributors to the pathogenesis of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (Gannon, Khan, & Kolson, Reference Gannon, Khan and Kolson2011; Saylor et al., Reference Saylor, Dickens, Sacktor, Haughey, Slusher, Pletnikov and McArthur2016). Although the prevalence of HIV-associated dementia has markedly decreased in the ART era, milder forms of neurocognitive impairment remain common, with a prevalence of 20–50% among people with HIV (PWH) (Iudicello et al., Reference Iudicello, Hussain, Watson, Morgan, Heaton, Stern and Alosco2019; Saloner & Cysique, Reference Saloner and Cysique2017). HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment has been associated with increased risk of deficits in real-world function including medication adherence, employment, automobile driving, and quality of life (Casaletto, Weber, Iudicello, & Woods, Reference Casaletto, Weber, Iudicello and Woods2017). Interventions that target neuroinflammation underlying these cognitive difficulties are lacking currently, but burgeoning evidence suggests there are potential therapeutic benefits of cannabis (Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018; Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Henriquez, Aldhamen, Gulick, Amalfitano and Kaminski2018).

Cannabis use is common among PWH in the U.S., with 23–56% reporting use in the past year (Pacek, Towe, Hobkirk, Nash, & Goodwin, Reference Pacek, Towe, Hobkirk, Nash and Goodwin2018). PWH also frequently report using cannabis for medicinal purposes (25–35%) (Fogarty et al., Reference Fogarty, Rawstorne, Prestage, Crawford, Grierson and Kippax2007) primarily for pain relief, alleviation of anxiety and depression, and appetite stimulation (Woolridge et al., Reference Woolridge, Barton, Samuel, Osorio, Dougherty and Holdcroft2005). Randomized clinical trials of cannabis and cannabinoids show moderate evidence of clinical benefit for HIV-associated symptoms such as appetite/weight loss and sensory neuropathy (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Toperoff, Vaida, Van Den Brande, Gonzales, Gouaux and Atkinson2009; National Academies of Sciences & Medicine, 2017; Whiting et al., Reference Whiting, Wolff, Deshpande, Di Nisio, Duffy, Hernandez and Ryder2015). Given high rates of use among PWH, growing state-based legalization in the U.S., and increased marketing of cannabis-based products, there is growing interest in examining the influence of cannabis on neurocognitive function in this population.

The current literature base examining the relationship of cannabis use and neurocognitive function in HIV shows inconsistent findings. Recent work from our group indicates that cannabis use is associated with lower rates of global neurocognitive impairment and higher performance in verbal fluency and learning domains selectively among PWH (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Paolillo, Morgan, Umlauf, Sundermann, Ellis and Grant2020). Light cannabis-using PWH have also shown higher verbal fluency compared to HIV− light cannabis users (Thames, Mahmood, Burggren, Karimian, & Kuhn, Reference Thames, Mahmood, Burggren, Karimian and Kuhn2016). Conversely, adverse effects of daily cannabis use on cognitive domains such as delayed recall/memory have also been observed (Cristiani, Pukay-Martin, & Bornstein, Reference Cristiani, Pukay-Martin and Bornstein2004), and several studies have shown comparable cognitive performance between PWH cannabis users and non-users (Chang, Cloak, Yakupov, & Ernst, Reference Chang, Cloak, Yakupov and Ernst2006; Thames, Kuhn, Williamson, et al., Reference Thames, Kuhn, Williamson, Jones, Mahmood and Hammond2017; Wang, Liang, Ernst, Oishi, & Chang, Reference Wang, Liang, Ernst, Oishi and Chang2020). Such variable findings suggest that characteristics of cannabis usage such as frequency and quantity of use, as well as other contextual and cohort factors, likely moderate its effects on neurocognitive performance (Gonzalez, Pacheco-Colon, Duperrouzel, & Hawes, Reference Gonzalez, Pacheco-Colon, Duperrouzel and Hawes2017).

Cannabis’ anti-inflammatory properties may underlie the sometimes observed beneficial effect of cannabis exposure on neurocognitive function in HIV. Cannabis aside, inflammatory biomarker levels remain elevated in PWH and contribute to CNS injury even when HIV RNA levels are suppressed (Neuhaus et al., Reference Neuhaus, Jacobs, Baker, Calmy, Duprez, La Rosa and Neaton2010; Wada et al., Reference Wada, Jacobson, Margolick, Breen, Macatangay, Penugonda and Bream2015). A key process in chronic HIV-associated neuroinflammation involves activated T-cell and monocyte migration to the brain. Subsequent interactions of infiltrating immune cells with astrocytes and microglia result in secretion of neurotoxic cytokines and chemokines (Hong & Banks, Reference Hong and Banks2015; Ramesh, MacLean, & Philipp, Reference Ramesh, MacLean and Philipp2013), and these pro-inflammatory factors in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma have been related to worse neurocognitive performance in PWH (Burdo et al., Reference Burdo, Weiffenbach, Woods, Letendre, Ellis and Williams2013; Burlacu et al., Reference Burlacu, Umlauf, Marcotte, Soontornniyomkij, Diaconu, Bulacu-Talnariu and Ene2020; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, de la Monte, Gongvatana, Ombao, Gonzalez, Devlin and Tashima2011; Imp et al., Reference Imp, Rubin, Tien, Plankey, Golub, French and Valcour2017; Kamat et al., Reference Kamat, Lyons, Misra, Uno, Morgello, Singer and Gabuzda2012; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Qiao, Wei, Yin, Liu, Ji and Chen2013).

Pre-clinical and human endocannabinoid system studies show that cannabinoids may mediate immunomodulatory actions that disrupt pro-inflammatory processes in HIV (Chen, Gao, Gao, Su, & Wu, Reference Chen, Gao, Gao, Su and Wu2017; Rom & Persidsky, Reference Rom and Persidsky2013). Recent evidence has demonstrated associations between current cannabis use and reduced systemic inflammation among PWH, as indexed by lower levels of activated and inflammatory monocyte frequencies, and in plasma, lower levels of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)1α, interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10), also referred to as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Silva, Dorneles, Barros, Ribeiro, Noronha and Pereira2019; Keen & Turner, Reference Keen and Turner2015; Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018; Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Henriquez, Aldhamen, Gulick, Amalfitano and Kaminski2018). In contrast, higher plasma levels of soluble cluster of differentiation 14 (sCD14) have been observed in cannabis-using compared to non-cannabis-using PWH (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Silva, Dorneles, Barros, Ribeiro, Noronha and Pereira2019), and many inflammatory plasma biomarkers (20 out of 21) have shown no differences by cannabis use among PWH (Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018). Higher levels of plasma interleukin-1β have also been observed among daily cannabis using PWH and HIV− individuals compared to non-users, with no differences in many inflammatory plasma biomarkers (23 out of 24) by cannabis use after controlling for multiple comparisons (Krsak et al., Reference Krsak, Wada, Plankey, Kinney, Epeldegui, Okafor and Erlandson2020). Thus, the prior literature is highly mixed, showing current cannabis use is associated with lower and higher levels of some plasma inflammatory biomarkers, and many peripheral markers show no evidence of cannabis-related modulation. No studies to date have examined the intersection of cannabis exposure, CNS inflammation, and cognition among PWH.

The goal of this study was to determine the relationship between cannabis use and HIV-associated inflammation, and the potential downstream association between inflammation and cognitive function. In study aim 1, we investigated the effects of no cannabis use, moderate cannabis use, and daily cannabis use on CSF and plasma biomarkers in PWH, with an HIV− non-cannabis-using comparison group. We hypothesized that cannabis use would be associated with lower levels of some inflammatory biomarkers among PWH, such as IP-10 and TNF-α, with others showing no differences by cannabis use, given the limited and mixed existing evidence. Post-hoc analyses investigated whether specific parameters of cannabis use over the past 6 months (cannabis quantity, cannabis recency, or cannabis frequency) correlated with CSF and plasma biomarkers.

In study aim 2, to determine the functional relevance of any anti-inflammatory cannabis effects observed, we first examined cognitive performance in PWH by cannabis use group, and next, examined relationships between inflammatory biomarker levels that were related to cannabis use in study aim 1, and cognitive performance in seven domains. We hypothesized that for biomarkers associated with cannabis use, lower levels of pro-inflammatory markers would relate to better performance in some cognitive domains among PWH, such as in verbal fluency and learning, based on previous findings from our group.

METHODS

Participants and Design

The sample included 263 community-dwelling adults enrolled in NIH-funded studies at UC San Diego’s HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP). Study design and cohort selection have been described in detail previously (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Franklin, Ellis, McCutchan, Letendre, Leblanc and Group2011). Study visits took place between August 2001 and January 2018. All study procedures were approved by the UC San Diego Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written, informed consent.

Inclusion criteria for the current analyses were data present for (a) detailed self-report of cannabis and other substance use; (b) drug urine toxicology; (c) inflammatory biomarkers; and (d) neurocognitive and neuromedical assessments. Exclusion criteria for the parent studies included history of non-HIV-related neurological, medical, or psychiatric disorders that affect brain function (e.g., epilepsy, stroke, schizophrenia), learning disabilities, or a dementia diagnosis. Exclusion criteria for the current analyses were (a) positive urine toxicology for addictive substances other than cannabis; (b) report of any substance use disorder, including alcohol use disorder, in the past year other than cannabis; and (c) reported use of any of the following substances in the past year: cocaine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, other stimulants, heroin, other opioids, sedatives, anti-anxiety drug abuse, hallucinogens, PCP, ketamine, or inhalants.

Cannabis Use

Cannabis use was characterized by self-report and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) positive urine toxicology. Frequency, quantity, and recency of cannabis use were assessed via a modified timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview (Robinson, Sobell, Sobell, & Leo, Reference Robinson, Sobell, Sobell and Leo2014). This modified TLFB captures age of first use and average quantities and frequencies of use during participant-identified periods of cannabis use. To define recent cannabis use patterns among participants, TLFB estimates were used to obtain an estimate of days since last use, as well as total days used, total grams used, and average grams per day of use, over the past 6 months.

Three cannabis use groups were defined for this study: non-cannabis users, moderate cannabis users, and daily cannabis users. When we initially examined cannabis use frequency within our cohort, this three-group categorization appeared to best characterize the natural distribution of cannabis use patterns. Non-cannabis users reported either no use of cannabis over their lifetime or no use in the past 5 years and had THC negative urine toxicology. Moderate cannabis users reported use of cannabis within the past month, with an average pattern of weekly use over the past 6 months (ranging from a minimum of 3 days of use over 6 months to a maximum of 3 days of use per week over 6 months), and could have positive or negative THC urine toxicology (given that participants with less frequent cannabis use could likely have a positive or negative THC screen on their testing day). Daily cannabis users reported a pattern of daily use over the past 6 months and had THC positive urine toxicology.

Inflammatory Biomarkers in CSF and Plasma

Blood was drawn via venipuncture through the antecubital vein into an EDTA vacutainer. Plasma was centrifuged at 1,800 relative centrifugal force for 8 min at room temperature and aliquoted for storage at −80°C until the time of assay. CSF was collected via lumbar puncture using a non-traumatic spinal needle and aseptic technique. CSF was centrifuged at low speed to separate cells; both supernatants and cells were aliquoted and stored at −80°C and were not thawed until the time of assay. Six pro-inflammatory biomarkers in plasma and CSF were measured using commercially available immunoassays and run according to the manufactures’ protocol: Interleukin-6 (IL-6); monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), also referred to as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2); IP-10; sCD14; soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type II (sTNFR-II) and TNF-α. Biomarker precision was ensured by (a) assaying all specimens in duplicate; (b) repeating assays of specimens with coefficients of variation greater than 20%; (c) repeating 10% of all assays to assess operator and batch consistency; and (d) regularly assessing batch effects.

Neurocognitive Testing

Participants completed a standardized battery of well-validated neuropsychological tests designed to assess global cognition and seven domains: verbal fluency, executive function, attention/working memory, processing speed, learning, delayed recall/memory, and motor skills. Details about all tests included in this battery have been published elsewhere (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Woods, Gonzalez, Conover, Marcotte, Grant and Heaton2004). Raw test scores were transformed into normally-distributed t-scores which are demographically adjusted for age, years of formal education, sex/gender, and race based on normative samples of HIV− participants (Heaton, Miller, Taylor, & Grant, Reference Heaton, Miller, Taylor and Grant2004; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Moore, Taylor, Franklin, Cysique, Ake and Group2011). Cognitive domain summary t-scores were generated by averaging t-scores across tests within a cognitive domain.

Neuromedical, Psychiatric, and Other Substance Use Assessment

Participants underwent a comprehensive neuromedical assessment. HIV infection was established by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with Western blot confirmation. Routine clinical chemistry panels, complete blood counts, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C virus antibody, and CD4 + T cells (flow cytometry) were performed. HIV viral load in plasma and CSF were measured using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), with a lower limit of quantitation (LLQ) of 50 copies/ml. HIV viral load was dichotomized as detectable versus undetectable at the LLQ of 50 copies/ml. Detailed medical and antiretroviral usage history was captured via a structured, clinician-administered questionnaire. Current depression symptoms were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996). Current tobacco use was assessed by a modified TLFB interview (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Sobell, Sobell and Leo2014), and defined by use (yes/no) in the past 6 months. Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI).

Statistical Analyses

Participants were categorized into four study groups based on HIV status and cannabis use: HIV− non-cannabis users, HIV+ non-cannabis users, HIV+ moderate cannabis users, and HIV+ daily cannabis users. Demographic, psychiatric, and HIV disease variables were compared across the four HIV/Cannabis groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Pair-wise comparisons were conducted to follow-up on significant omnibus results using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests or Wilcoxon tests for continuous outcomes and χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical outcomes, with false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment. We also compared cannabis use characteristics between the HIV+ moderate and daily user groups (age of first use; over the past 6 months: total days used, total grams used, and average grams per day of use; days since last use; and THC positive urine toxicology).

For study aim 1, Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare levels of CSF and plasma biomarkers between the four HIV/Cannabis groups. p-values were adjusted using FDR correction for multiple comparisons, and p-values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Biomarkers were adjusted for batch effects and log10 transformed (except for sCD14) to improve fit and limit the influence of outliers. Additionally, non-parametric tests which are robust to outliers were employed for study aim 1. Biomarker data was further examined for outliers, defined as any log-transformed biomarker values outside the 3 SD range. Sensitivity analyses were conducted on a subset of participants, with all outliers identified by this criteria removed. Criteria for covariate inclusion in our study aim 1 models were characteristics that differed by cannabis use between the three HIV+ groups; all characteristics assessed showed comparable levels across HIV+ groups, and thus no covariates were included in study aim 1 models. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine whether including current tobacco use as a covariate influenced the relationship between cannabis use group and inflammatory biomarkers. In post-hoc analyses, Spearman’s rho correlations examined whether specific parameters of cannabis use over the past 6 months (total grams of cannabis used, days since last cannabis use, or total days of cannabis use) correlated with inflammatory biomarkers.

For study aim 2, we first examined cognitive performance across HIV+ non-cannabis users, HIV+ moderate cannabis users, and HIV+ daily cannabis users. Next, multivariable linear regressions examined relationships between any biomarkers showing lower levels with cannabis use in study aim 1 and cognitive domain t-scores among PWH. Given that t-scores adjust for demographic factors that can influence cognitive performance: age, years of formal education, sex/gender, and race, we did not include any further demographic covariates in our models. We included current CD4 + T cell count and current tobacco use as covariates. Effect sizes for regression analyses were presented as estimated regression coefficients (b). p-values for the association of a biomarker with each cognitive domain were adjusted using FDR correction and p-values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Given that a portion of the HIV+ cohort was not virally suppressed, sensitivity analyses were conducted on a subset of PWH with undetectable plasma HIV RNA.

RESULTS

The study cohort of 263 community-dwelling adults included 198 PWH and 65 HIV− people, and ranged in age from 18 to 70 years old (M = 42.3, SD = 11.1). Four study groups included the HIV− non-cannabis users (n = 65) comparison group, and PWH categorized into three groups based on cannabis use: HIV+ non-cannabis users (n = 105), HIV+ moderate cannabis users (n = 62), and HIV+ daily cannabis users (n = 31).

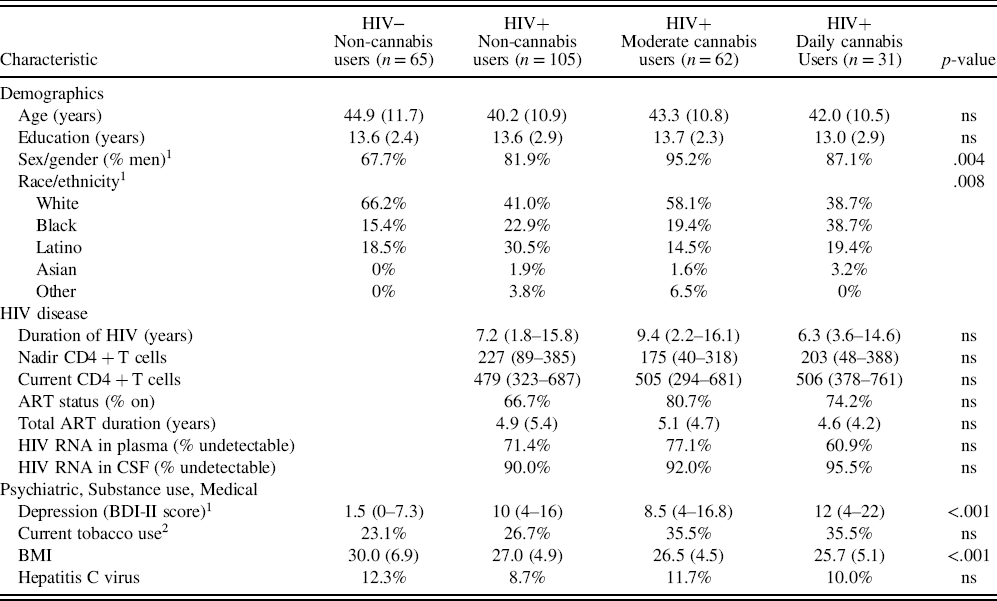

Sample characteristics by HIV/Cannabis group are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, years of formal education, current tobacco use, nor hepatitis C virus across study groups. While there was a greater proportion of men, greater proportion of non-white people of color, higher depression symptoms, and lower BMI in the three HIV+ groups compared to the HIV− group, these characteristics did not differ between the HIV+ cannabis use subgroups. Thus, these characteristics were not included as covariates in study aim 1 models. Furthermore, no HIV disease characteristics (e.g. duration of HIV disease, current CD4 + T cell count, HIV RNA in plasma and CSF) differed across HIV+ cannabis use subgroups and were not included as covariates in study aim 1 models.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (n = 263)

Data are presented as Mean (SD), Median (IQR), or %.

Abbreviations: ns = non-significant (p ≥ .05); HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-2nd Edition; BMI = Body Mass Index.

1 Only four characteristics varied between the four groups: sex/gender, race/ethnicity, depression symptoms, and BMI. All three HIV+ groups had a higher proportion of men and people of color, higher depression symptoms, and lower BMI compared to the HIV− group but these variables did not differ by cannabis use between HIV+ groups.

2 Use in the past 6 months.

Self-reported cannabis use characteristics were compared between HIV+ moderate and daily cannabis users in Table 2. While age of first use was comparable between the two groups, over the past 6 months, daily users reported higher total days used, higher total grams used, and higher grams per day of use compared to moderate users (p < .001, p < .001, p = .04). Daily users reported a median of 0.5 grams per day of use (IQR = 0.2–1.1), while moderate users reported a median of 0.3 grams per day of use (IQR = 0.2–0.8). Per inclusion criteria for the daily users, 100% had THC positive urine toxicology, while 47.5% of moderate users had THC positive urine toxicology (p < .001).

Table 2. Cannabis use characteristics of HIV+ moderate and daily users

Data are presented as Mean (SD) or Median (IQR).

Abbreviations: ns = non-significant (p ≥ .05); HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; THC = Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

1 Over the past 6 months.

2 Per day of cannabis use.

CSF Biomarkers: Lower MCP-1 and IP-10 in Daily Cannabis Users

Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed a significant omnibus difference across HIV/Cannabis groups in MCP-1 and IP-10 levels in CSF (p = .027; p = .001) with FDR adjustment. Follow-up pair-wise comparisons showed that MCP-1 and IP-10 levels in CSF were significantly lower in HIV+ daily cannabis users compared to HIV+ non-cannabis users (p = .015; p = .039; Figure 1A and 1B). Furthermore, CSF MCP-1 was higher in HIV+ non-cannabis users compared to the HIV− non-cannabis users (p = .005; Figure 1A). CSF IP-10 was higher in HIV+ non-cannabis and moderate cannabis users compared to the HIV− non-cannabis users (p < .001, p = .003; Figure 1B). No differences were observed in IL-6, sCD14, sTNFR-II, and TNF-α levels in CSF across HIV/Cannabis groups.

Fig. 1. HIV+ daily cannabis users display lower levels of MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF compared to HIV+ non-cannabis users. Abbreviations: MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; IP-10 = interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Plasma Biomarkers: No Differences by Cannabis Use

Plasma biomarkers IL-6, MCP-1, sCD14, sTNFR-II, and TNF-α showed no significant omnibus differences across HIV/Cannabis groups. There was a significant omnibus difference across HIV/Cannabis groups in plasma IP-10 levels (p < .001) with FDR adjustment. Follow-up pair-wise comparisons showed that plasma IP-10 was elevated in all three HIV+ groups: HIV+ non-cannabis users (p < .001), HIV+ moderate cannabis users (p < .001), and HIV+ daily cannabis users (p = .042), compared to the HIV− group.

In sensitivity analyses with biomarker outliers removed, CSF and plasma findings did not differ from whole sample analyses. In sensitivity analyses adjusting for current tobacco use, CSF and plasma findings also did not differ from whole sample analyses, and no independent effects of tobacco use on CSF or plasma biomarker levels were observed.

Cannabis Use Parameters and Biomarker Correlations

Total grams of cannabis used over the past 6 months did not correlate significantly with any CSF or plasma biomarkers (ps > .05). Days since last cannabis use also did not correlate significantly with any CSF or plasma biomarkers (ps > .05). Two trend-level correlations were observed. Total grams of cannabis used trended towards a small to medium negative correlation with CSF IP-10 (r = -.19, p = .083), indicating that more grams consumed was weakly linked to lower IP-10 in CSF. Days since last cannabis use trended towards a small to medium positive correlation with CSF MCP-1 (r = .18, p = .082), indicating more recent cannabis use was weakly linked to lower MCP-1 in CSF. Total days of cannabis use over the past 6 months had medium and significant negative correlations with CSF MCP-1 (r = –.23, p = .026) and CSF IP-10 (r = –.27, p = .011), indicating that greater days of cannabis use predicted lower levels of MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF.

Cognitive Performance and CSF MCP-1 and IP-10

Across the HIV+ groups, HIV+ daily cannabis users had similar global cognitive performance with a trend of better performance (M = 48.8, SD = 6.0) compared to HIV+ moderate cannabis users (M = 46.4, SD = 6.5) and HIV+ non-cannabis users (M = 46.9, SD = 6.8) (p = .26). An analogous pattern was observed in the domains of: verbal fluency, attention/working memory, processing speed, learning, and motor skills, with a slightly and non-significantly higher performance among HIV+ daily cannabis users. Among all PWH, a negative association was detected between MCP-1 in CSF and learning performance (β = -6.3, p = .016; Table 3), indicating that lower MCP-1 is related to better learning, while adjusting for current CD4 count and current tobacco use. A negative association was also detected between IP-10 in CSF and learning (β = -2.3, p = .036; Table 3) among PWH, indicating that lower IP-10 was associated with better learning performance with the same covariate and FDR adjustment. CSF MCP-1 and IP-10 did not relate significantly to any other cognitive domains among PWH.

Table 3. Relationship of CSF biomarkers and cognitive domains among people with HIV

Cognitive t-scores are adjusted for age, sex/gender, race, and years of formal education, and models adjust for current tobacco use and current CD4 + T cell count.

Abbreviations: ns = non-significant (p ≥ .05); CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; IP-10 = interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10.

1 p-values were adjusted using false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons.

In sensitivity analyses with the PWH sample restricted to those with undetectable plasma HIV RNA viral load, CSF and plasma biomarker and cognitive domain findings (study aims 1 and 2) did not differ from whole sample analyses.

DISCUSSION

Study findings support our hypotheses that frequent cannabis exposure may reduce neuroinflammation in PWH, with possible downstream benefits for cognition. Daily cannabis use was associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory chemokines MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF, factors critical to immune cell migration and HIV pathogenesis. In contrast, cannabis use was not associated with inflammatory biomarker levels in plasma. HIV+ daily cannabis users showed similar cognitive performances with a trend toward higher scores in global cognition and several cognitive domains including learning compared to HIV+ moderate users and HIV+ non-cannabis users. Lower CSF levels of MCP-1 and IP-10 were related to better cognitive performance in the domain of learning, which is commonly impaired in HIV disease. When recent cannabis use parameters were examined, cannabis quantity and cannabis recency did not correlate significantly with any inflammatory biomarkers, but greater total days of cannabis use, or cannabis frequency, significantly predicted lower levels of MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF. Findings indicate that regular, daily cannabis use may be important for reduced CNS inflammation in HIV. Importantly, daily cannabis users in this cohort reported a median of half a gram of cannabis use per day, and 75% of daily users reported less than 1.1 grams of cannabis use per day, suggesting that frequent, but not heavy cannabis use generally characterized this group. Therefore, inference about the anti-inflammatory benefit of cannabis in PWH cannot be extrapolated to more high-dose, heavy use of cannabis. Furthermore, given our study design is retrospective and cross-sectional, we cannot clarify actual cause-effect relationships regarding the inflammation modulatory effects of cannabis, which would require longitudinal study design.

Our study findings are novel in detection of lower pro-inflammatory chemokines with cannabis exposure specifically in CSF, and converge with recent research showing anti-inflammatory activity of cannabis in PWH on activated immune cells and systemic inflammation (Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018; Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Henriquez, Aldhamen, Gulick, Amalfitano and Kaminski2018). Lower CSF MCP-1 and IP-10 with daily cannabis use and no differences by cannabis use for CSF biomarkers IL-6, sCD14, sTNFR-II, and TNF-α suggest that MCP-1 and IP-10 may be specifically sensitive to cannabis-related modulation and could play a mechanistic role in any downstream cognitive benefit or physical symptom relief observed with regular cannabis use among PWH. Both IP-10 and MCP-1 are considered important contributors to neuroinflammation in HIV infection and reductions in their levels could have beneficial downstream effects for PWH. IP-10 is a major chemo-attractant for T-cells and activated monocytes, and in excess, leads to neurotoxic pro-inflammatory cytokine production and neuronal apoptosis, while MCP-1 mediates trafficking of infected macrophages across the blood brain barrier (Asensio et al., Reference Asensio, Maier, Milner, Boztug, Kincaid, Moulard and Fox2001; de Almeida et al., Reference de Almeida, Letendre, Zimmerman, Lazzaretto, McCutchan and Ellis2005; Pulliam et al., Reference Pulliam, Rempel, Sun, Abadjian, Calosing and Meyerhoff2011; Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Scully, Groden, Benedict, Chang, Lane and Altfeld2013). Our findings suggest that cannabis use may lead to reduced CNS-infiltration of T cells and monocytes. In a small pilot study, our group recently reported that cannabis recency (days since last use) was associated with lower levels of CSF interleukin-16 (IL-16) and C reactive protein (CRP) (Ellis, Peterson, Li, et al., Reference Ellis, Peterson, Li, Schrier, Iudicello, Letendre and Cherner2020). These findings are complementary with the current study in suggesting that sustained reductions in neuroinflammation related to cannabis likely require ongoing exposure, although we only observed a small to medium and non-significant relationship between cannabis recency and CSF MCP-1 in this cohort. The current study’s findings suggest that the parameter of cannabis frequency is slightly more predictive of inflammatory biomarker levels compared to cannabis quantity and cannabis recency. An additional benefit of cannabis, potentially linked to its anti-inflammatory effects, is stabilization of the blood brain barrier, which we demonstrated in a separate report showing that more frequent use of cannabis in the past month was associated with higher blood brain barrier integrity in PWH (Ellis, Peterson, Cherner, et al., Reference Ellis, Peterson, Cherner, Morgan, Schrier, Tang and Iudicello2020). We extend this work in the current study, showing that lower MCP-1 and lower IP-10 relate to better learning performance, a cognitive domain which frequently shows mild deficits in PWH in the ART era (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Clifford, Franklin, Woods, Ake, Vaida and Atkinson2010). Elevated MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF have previously been observed in PWH with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (Mehla, Bivalkar-Mehla, Nagarkatti, & Chauhan, Reference Mehla, Bivalkar-Mehla, Nagarkatti and Chauhan2012; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Qiao, Wei, Yin, Liu, Ji and Chen2013).

Taken together, findings are consistent with the notion that cannabinoids may modulate inflammatory processes in PWH, specifically in the CNS, and suggest a link between lower CNS inflammation and better neurocognitive function. Our finding that HIV+ daily cannabis users showed slightly and non-significantly better performance in several cognitive domains compared to HIV+ non-users reflects a similar pattern to a recent study (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Ernst, Oishi and Chang2020), suggesting a signal of a neuroprotective effect which warrants further investigation of regular cannabis use among PWH. Our sensitivity analyses indicate that the relationships observed between cannabis, inflammatory biomarkers, and cognition are relevant to PWH with both detectable and undetectable plasma HIV RNA.

In plasma, we observed elevated IP-10 in all three HIV+ groups compared to the HIV− group, but we did not detect lower levels of plasma IP-10 nor TNF-α with cannabis use as previous studies found (Keen & Turner, Reference Keen and Turner2015; Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Henriquez, Aldhamen, Gulick, Amalfitano and Kaminski2018). Our null findings for the relationship between cannabis use and plasma biomarker levels are congruous with several other studies in which the vast majority of peripheral inflammatory and immune activation markers show no differences by cannabis use (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Silva, Dorneles, Barros, Ribeiro, Noronha and Pereira2019; Krsak et al., Reference Krsak, Wada, Plankey, Kinney, Epeldegui, Okafor and Erlandson2020; Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018). Although plasma levels of chemokines such as MCP-1 are generally reflective of inflammatory states and found to be elevated in patients with neurodegenerative diseases (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Liao, Wang, Lin, Wang and Fuh2018), chemokine levels in the CNS may more specifically indicate their role in microglial activation and proliferation and chemotaxis of blood monocytes to the CNS (Weiss, Downie, Lyman, & Berman, Reference Weiss, Downie, Lyman and Berman1998). It is important to recognize the biological implications of differing chemokine levels found in CSF and plasma hence, differential cannabis effects. There may be several reasons why we observed distinct cannabis effects in CSF and plasma. Cannabinoids are highly lipid soluble, so their biological effects may be amplified and prolonged in CSF as compared to blood (Hložek et al., Reference Hložek, Uttl, Kadeřábek, Balíková, Lhotková, Horsley and Tylš2017; Huestis & Smith, Reference Huestis and Smith2007). Furthermore, immune responses between CNS and peripheral blood are typically compartmentalized and the dynamics of chemokine production, degradation, and removal in each may differ. Numerous HIV studies have shown that levels of neurotoxic chemokines such as MCP-1 and IP-10 are much higher in CSF than in plasma, suggesting that there are distinct production and metabolism processes for these chemokines in CSF compared to plasma (de Almeida et al., Reference de Almeida, Letendre, Zimmerman, Lazzaretto, McCutchan and Ellis2005; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Liu, Qiao, Sheng, Xu, Li and Chen2015). Although we cannot determine the exact cellular sources of MCP-1 in CSF in our study, MCP-1 causes activation and proliferation of microglia and neurotoxicity, highlighting its role in neuroinflammation and brain outcomes (Hinojosa, Garcia-Bueno, Leza, & Madrigal, Reference Hinojosa, Garcia-Bueno, Leza and Madrigal2011; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Meng, Li, Yong, Fan, Ding and Ke2011). Lastly, CSF biomarkers may be more robust indicators of changes relevant to CNS function and neurocognitive outcomes compared to peripheral blood markers.

Mechanistically, our findings are consistent with the current preclinical literature showing cannabis-related modulation of pro-inflammatory processes in HIV via the endocannabinoid system (Costiniuk & Jenabian, Reference Costiniuk and Jenabian2019). While cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors are the principal type found in the CNS and account for the psychoactive effects of ligands such as THC, cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptors also are expressed in the CNS by microglia and astrocytes (Bisogno & Di Marzo, Reference Bisogno and Di Marzo2010; Van Sickle et al., Reference Van Sickle, Duncan, Kingsley, Mouihate, Urbani, Mackie and Sharkey2005). Preclinical models show activation of CB1 and CB2 receptors can induce apoptosis of activated T-cells and macrophages (Persidsky et al., Reference Persidsky, Fan, Dykstra, Reichenbach, Rom and Ramirez2015), downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production (Nagarkatti, Pandey, Rieder, Hegde, & Nagarkatti, Reference Nagarkatti, Pandey, Rieder, Hegde and Nagarkatti2009), and inhibit HIV-associated synapse loss and neural injury (Kim, Shin, & Thayer, Reference Kim, Shin and Thayer2011; Ramirez et al., Reference Ramirez, Reichenbach, Fan, Rom, Merkel, Wang and Persidsky2013). Both natural and synthetic cannabinoids have demonstrated neuroprotective effects after various types of CNS insults, and in particular under conditions of high inflammation (Bilkei-Gorzo et al., Reference Bilkei-Gorzo, Albayram, Draffehn, Michel, Piyanova, Oppenheimer and Imbeault2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Gao, Gao, Su and Wu2017). In vitro, THC treatment has been shown to suppress a number of pro-inflammatory factors including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 and decrease NF-κB secretion in human osteosarcoma cells (Yang, Li, Han, Jia, & Ding, Reference Yang, Li, Han, Jia and Ding2015) as well as monocyte-derived interleukin IL-1ß production and astrocyte secretion of MCP-1 and IL-6 from a human coculture system (Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Bach, Sermet, Amalfitano and Kaminski2019). In sum, there is substantial evidence that cannabinoids display beneficial effects on chronic inflammatory responses in HIV infection.

Our study has several limitations. First, cross-sectional analyses of an observational cohort cannot establish cause–effect relationships. Second, we lacked an HIV− cannabis user group to compare cannabis effects on inflammatory markers by HIV status. While an HIV− cannabis-using group would allow for a more balanced design, our HIV− non-cannabis user group did allow us to observe differences in inflammatory markers between this comparison group and the three HIV+ cannabis use groups. Third, the majority of participants in this study were men and we were underpowered to examine sex/gender differences or similarities in cannabis-related modulation of inflammatory markers. Animal models have shown that endogenous sex hormones and synthetic steroid hormones influence physiological response to cannabinoids, and modulate drug sensitivity (Struik, Sanna, & Fattore, Reference Struik, Sanna and Fattore2018), and a recent study among PWH suggests a few inflammatory biomarker levels differ by sex/gender (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Neigh, Sundermann, Xu, Scully and Maki2019). Future work should include a larger cohort of women with HIV and examine whether relationships between cannabis, neuroinflammation, and cognition are similar or vary by sex/gender or by specific hormone levels. Fourth, our method of defining cannabis use groups combined self-report of frequency and quantity of use and urine toxicology. While this method is more comprehensive than most previous studies in PWH, which rely solely on self-report, self-report of drug use remains prone to inaccuracy due to possibility of recall bias and/or social desirability bias. Previous studies have collected more detailed frequency of use data with the number of times of cannabis use per day to characterize heavier user groups (Bolla, Brown, Eldreth, Tate, & Cadet, Reference Bolla, Brown, Eldreth, Tate and Cadet2002; Thames et al., Reference Thames, Mahmood, Burggren, Karimian and Kuhn2016) while our study only characterized daily users. Further, two recent studies used a more precise method to categorize levels of cannabis exposure with direct measurement of cannabis metabolites in plasma (Manuzak et al., Reference Manuzak, Gott, Kirkwood, Coronado, Hensley-McBain, Miller and Martin2018; Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Crawford, Henriquez, Aldhamen, Gulick, Amalfitano and Kaminski2018); this data is not available for our sample. Additionally, we did not collect information concerning important aspects of cannabis use such as: recreational versus medicinal use, cannabinoid composition (e.g. THC/CBD ratio), nor strength of cannabis strain. Such contextual variables may moderate the anti-inflammatory effects of cannabis observed in this study. Fifth, our study lacks data on anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and numerous forms of social adversity that PWH commonly face in the U.S. and are detrimental to neurocognition (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Cook, Springer, Weber, Cohen, Martin and Milam2017; Thames, Kuhn, Mahmood, et al., Reference Thames, Kuhn, Mahmood, Bilder, Williamson, Singer and Arentoft2017; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Sundermann, Hussain, Umlauf, Thames, Moore and Moore2019). Lastly, our study did not collect standardized data on dietary factors nor regular physical exercise which can influence chemokine expression via pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects (Montoya et al., Reference Montoya, Jankowski, O’Brien, Webel, Oursler, Henry and Erlandson2019). Future cannabis research in PWH should undertake careful assessment of cannabis use, anxiety and trauma-related disorders, social adversity, and dietary and physical exercise variables, as these factors should be considered for their influence on both inflammatory processes and neurocognitive outcomes.

Future studies in PWH are needed to investigate potential distinct effects of specific cannabinoids, and adult medicinal use, on brain structure and function. These relations among PWH can be clarified in longitudinal studies following designs of recent medicinal cannabis, neuroimaging, and cognition studies in a general clinical population (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Sagar, Dahlgren, Gonenc, Smith, Lambros and Lukas2018). Any neuroprotective effects of cannabis products on cognition are likely limited to specific cannabis/cannabinoid use parameters and individual characteristics of users (disease comorbidities, pharmacokinetic factors). In the general population, studies of heavy recreational cannabis use and cannabis dependence show CB1 receptor downregulation, which may be a mechanism for drug tolerance, lead to CB2 receptor desensitization on immune cells, and disrupt endocannabinoid system homeostasis (Hirvonen et al., Reference Hirvonen, Goodwin, Li, Terry, Zoghbi, Morse and Innis2012; Rotter et al., Reference Rotter, Bayerlein, Hansbauer, Weiland, Sperling, Kornhuber and Biermann2013). Thus, determination of harmful levels of cannabis use in relation to quantity and addictive potential must be considered in PWH.

Our work demonstrated some reduced inflammation in CSF, but not plasma, among HIV+ daily cannabis users who reported a median of half a gram of cannabis use per day. Of functional relevance, lower levels of chemokines MCP-1 and IP-10 in CSF were associated with better cognitive performance in the domain of learning among PWH. Our findings point to the need for more targeted mechanistic studies of cannabis use and cognition specifically in PWH. In the context of HIV-associated chronic immune system activation and neuroinflammation, cannabis-based therapeutics may have a role in reducing inflammation and risk for downstream neurocognitive impairment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH), including the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (grant numbers P30MH062512, N01MH22005, HHSN271201000036C, HHSN271201000030C); and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (grant numbers P50DA026306, P01DA12065). CWW and LMC were supported by NIDA (grant number T32DA031098). SH was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (grant number AG063328). RE was supported by NIA (grant number R01AG048650–01A1). JI was supported by NIDA (grant numbers K23DA037793, R01DA047879).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.