INTRODUCTION

Confabulation, the production of statements or actions that are unintentionally incongruous to the subject’s history, background, present and future situation (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a), is observed in several conditions affecting the nervous systems and can follow lesions located in several brain areas (see Schnider, Reference Schnider2008, for a review).

Since the early description of this phenomenon, clinicians and scientists have distinguished between two forms of confabulation. Bonhoeffer (Reference Bonhoeffer1904) distinguished between momentary confabulations and fantastic confabulations. Momentary confabulations are typically produced in response to questions, are always plausible and have been considered to reflect a more or less intentional strategy to fill a gap in memory and to overcome embarrassment. Momentary confabulations have also been called “out of embarrassment” confabulations (Verlegenheit Konfabulationen) (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1949), classic compensatory confabulations (Flament, Reference Flament1957) or simply “confabulations” (Talland, Reference Talland1961). By contrast, fantastic confabulations are much more context-free, unprovoked, implausible statements relating to unreal events and often favored by an euphoric mood.

More recently, Kopelman (Reference Kopelman1987), following Berlyne (Reference Berlyne1972) distinguished between provoked and spontaneous confabulations. According to Kopelman, provoked confabulation reflects a normal, plausible response to a faulty memory, whereas spontaneous confabulation reflects the production of incoherent memories and associations, resulting from the superimposition of frontal dysfunction on an organic amnesia. For example, patients with spontaneous confabulation may report as personal memories incoherent and implausible events such as having been visiting their parents or grandparents who had been dead for years. Kopelman’s conceptual distinction between these two types of confabulation is certainly valuable because it underlines the qualitative difference between two extreme forms of confabulation, which may have different underlying mechanisms. In addition, in focusing on the modality of appearance, spontaneous vs provoked, it provided a clearly defined method for testing provoked confabulation. However, the line drawn between spontaneous and provoked confabulation often results in a quite difficult decision, because in some cases, spontaneous confabulations are plausible (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a) and provoked confabulation may be bizarre and implausible (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993b).

Schnider (Reference Schnider2008) extended Kopelman’s classification and proposed to distinguish between four forms of confabulation: 1. Intrusions in memory tests, or alternatively, provoked confabulation; 2. Momentary confabulations, which describe false verbal statements in a discussion or other situation inciting a patient to make comments; 3. Fantastic confabulation, which have no basis in reality, are nonsensical and logically inconceivable; 4. Behaviorally spontaneous confabulations occurring in the context of severe amnesia and disorientation. With this term, Schnider indicates patients who not only produce verbal confabulations, but who also behave and act on their confabulations.

Following a different perspective, Dalla Barba (Reference Dalla Barba1993b) proposed that, regardless their modality of appearance (spontaneous vs. provoked), confabulations can be distinguished according to the semantic quality of their content. Confabulation may be semantically appropriate, when, because of their internal semantic coherence, they are indistinguishable from true memories, unless one has access to personal information concerning the individual who confabulates. Or, they can be semantically anomalous, when, because of their internal semantic incoherence, they are recognizable as confabulations, although one does not know anything about the individual who confabulates. An example of semantically appropriate confabulation is: “Yesterday I went shopping” (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a). An example of semantically anomalous confabulation is: “Yesterday I won a running race and I was awarded with a piece of meat which was put on my right knee” (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993b). They are both confabulations, but to recognize them as such, in the first case one needs to know that the day before the patient could not go shopping because he was hospitalized, whereas in the second case one does not need any external additional information. In fact, in this case, confabulation describes an event that not only the patient is unlikely to have experienced at that particular time, but which is unlikely that anybody would have or will ever experience.

Like many distinctions, those proposed for confabulation show advantages and limits. The advantage is that they provide a separation between phenomena that may reflect differing underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms. The limit is that they fail to classify several confabulations that are not appropriately captured by either of the distinctions’ terms.

Clinical and experimental observation shows that confabulation often consists of personal habits which are considered by the patient as specific personal episodes. When asked what they did today or what they will be doing tomorrow, confabulating patients may reply with well-established memories from the past, however irrelevant these memories may be to their present situation. This type of confabulation can be either provoked by specific questions or produced spontaneously (e.g., Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a; Dalla Barba, Boissé, Bartolomeo, & Bachoud-Lévi, Reference Dalla Barba, Boissé, Bartolomeo and Bachoud-Lévi1997; Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, Signorini, & Denes, Reference Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, Signorini and Denes1997). These observations have been formalized in theoretical terms and experimentally supported by some authors. From a theoretical point of view, confabulation consisting of what we will refer to as Habits Confabulation (HC) seems to be compatible with accounts proposed, for example by Burgess and Shallice (Burgess & Shallice, Reference Burgess and Shallice1996) and Moscovitch and coworkers (Gilboa, Alain, Stuss, Melo, & Moscovitch, Reference Gilboa, Alain, Stuss, Melo and Moscovitch2006; Moscovitch & Melo, Reference Moscovitch and Melo1997). However, we have analyzed in detail elsewhere these accounts (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba and Tulving2000, Reference Dalla Barba2001, Reference Dalla Barba2002) showing that they contain theoretically unsolved problems, namely in attributing intentionality to unconscious processes. From the clinical and experimental domain, it is evident that confabulating patients rely on their habits to consciously remember their past and project their future. This has been well documented by several studies (Attali, De Anna, Dubois, & Dalla Barba, Reference Attali, De Anna, Dubois and Dalla Barba2009; Burgess & McNeil, Reference Burgess and McNeil1999; Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a, Reference Dalla Barba1993b; Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, et al., Reference Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, Signorini and Denes1997; Metcalf, Langdon, & Coltheart, Reference Metcalf, Langdon and Coltheart2007). However, the quantitative contribution of the retrieval of HC in confabulators has never been directly studied.

Based on our previous theoretical and experimental work, our hypothesis predicts that this type of confabulation, HC, contributes more to confabulations than other types of confabulatory responses. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to characterize and quantify the relative contribution of HC to confabulations produced by confabulating amnesics of various etiologies and patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The rationale for comparing AD patients and confabulating amnesics (CA) was to test the prediction that even very different pathologies tend to produce the same patterns of confabulations. In other words, we expect that mild AD patients, who are known to be mild confabulators, produce less confabulations than CA patients, but, like CA patients, more confabulations of the HC type than other types of confabulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 28 participants entered the study. Ten patients with a clinical diagnosis of probable AD according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price & Stadlan, Reference McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price and Stadlan1984) (6 female, mean age: 80.2 years, years of education: 10.4, all right-handed, mean MMSE score: 22.5), 8 confabulating amnesic (CA) patients of various etiologies (see Table 1 for CA patients characteristics) and 10 aged normal controls (NC). All patients had a digit span ≥ 5 and were judged to be normal on bedside tests of oral expression and understanding of oral language. NC were either spouses of patients or other individuals who volunteered to participate in the research projects of our laboratory. All the participants gave their written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki (2000).

Table 1. CA patients’ characteristics

Note

AACoA = aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; APCoA = aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery.

Experimental Material

Confabulations were collected with the Confabulation Battery (CB) (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a; Dalla Barba & Decaix, Reference Dalla Barba and Decaix2009). The CB involves the retrieval of various kinds of information and consists of 165 questions, 15 for each of the following domains:

1. Personal Semantic Memory (age, date of birth, current address, number of children, etc.).

2. Episodic Memory. Episodic, autobiographical questions.

3. Orientation in Time and Place.

4. Linguistic Semantic Memory. Items 16 to 30 of the WAIS vocabulary subtest were selected for a word definition task.

5. Recent General Semantic Memory. Knowledge of facts and people, which have been repeatedly reported in the news during the last ten years. For example, “Who is Ben Laden?”

6. Contemporary General Semantic Memory. Knowledge of famous facts and famous people from 1940 to 1990. For example, “What happened in Paris in May 1968?”

7. Historical General Semantic Memory. Knowledge of famous facts and famous people before 1900. For example, “What happened in 1789?”

8. Semantic Plans. Knowledge of issues and events likely to happen in the next ten years. For example, “Can you tell me what you think will be the most important medical breakthrough likely to take place in the next 10 years?”

9. Episodic Plans. Personal events likely to happen in the future. For example, “What are you going to do tomorrow?”

10. “I don’t know” Semantic. These were questions tapping semantic knowledge and constructed so as to receive the response “I don’t know” from normal subjects. For example, “What did Marilyn Monroe’s father do?”

11. “I don’t know” Episodic. These questions tapped episodic memory and were constructed so as to receive the response “I don’t know” by normal subjects. For example, “Do you remember what you did on March 13, 1985?”

Procedure

Questions from the 11 domains were presented to the participants in a semi-randomized order. Responses were scored as “correct”, “wrong”, “I don’t know”, and “confabulation”. For episodic memory, responses were scored “correct” when they matched information obtained from the patient’s relatives. Correct responses were self-evident for semantic memory questions. For “I don’t know” questions, both Semantic and Episodic, an “I don’t know” response was scored as correct. Because there is no sufficiently acceptable external criterion capable of defining confabulation, for its detection an arbitrary decision necessarily had to be made. To distinguish between a wrong response and a confabulation, a clear-cut decision was adopted only for answers to questions probing orientation in time. In this case, the most strict criterion was chosen: answers to questions regarding the current year, season, month, day of the month, day of the week, and hour of the day were judged to be confabulations only if erring for more than 5 years, 1 season, 2 months, 10 days, 3 days, or 4 hours, respectively. Answers to the other questions of the CB were independently rated as “correct”, “wrong”, and “confabulation” by four different raters, and inter-rater reliability was 100%. Minor distortions were considered errors, whereas major discrepancies between the expected and the given answer were considered confabulations, regardless of their content. In other words, generic responses and errors were not coded as confabulation if they did not show major discrepancies with the expected response. It must be emphasized that the decision as to whether an answer was wrong or confabulatory was never puzzling, although it may have been made on an arbitrary or subjective basis. As far as questions concerning personal and semantic plans are concerned, it might be argued that any possible answer is a confabulation, because, by definition, the future is only “probable” and there is in principle no “correct” answer to questions about the future. Yet, answers concerning the future can be definitely confabulatory when they show a marked discrepancy or a real contradiction with what a predicted future event might be, in view of the present situation. For example, although he was hospitalized and despite the fact that there was not any television in the ward, to the question “What are you going to do to night?”, one patient answered “I’ll have dinner with my wife and then watch the news on the television”.

All patients confabulated also spontaneously in their daily life and some of them acted on their confabulations. However, their spontaneous confabulations were not analyzed here [but see (Dalla Barba, & Boissé, Reference Dalla Barba and Boissé2010) for the analysis of CA’s confabulations].

Three different, independent raters classified confabulations according to the following criteria:

1. Habits: these are confabulations consisting of personal habits, which are considered by the patient as specific personal episodes.

2. Misplacements: these are confabulations consisting of true episodes and facts misplaced in time and place.

3. Memory Fabrications: these are plausible memories, semantic or episodic, without any recognizable link with personal or public events.

4. Memory Confusions: these are confusions with other personal or public events related to the target memory or confusion between family members.

5. Autoreferential Contaminations occur when patients, questioned about public or historical events, refer to the event in a personal context.

6. Semantically Anomalous are those confabulations with an extremely bizarre and semantically anomalous content.

Statistical analyses were conducted on the mean percentage of correct responses and confabulations on the CB. Further analyses were conducted on the types of confabulations, as classified according to the criteria described above.

RESULTS

Participants’ performance in the CB is reported in Figure 1. The percentage of correct responses was entered in a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group (AD, CA, and NC) as between-subjects factor and type of question (the CB’s 11 types of question) as repeated measures factor. Results indicated a main effect for group [F(2,25) = 76.8; p < .001] and for type of question [F(10,250) = 15.5; p < .001]. Post hoc analysis (Scheffe’s F corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons) revealed that NC produced significantly more correct responses than CA patients for all types of questions (all p < .01). Compared with AD patients, NC produced significantly more correct responses for all types of questions (all p < .01), except for linguistic semantic memory and historical general semantic memory. AD patients produced significantly more correct responses than CA patients for all types of questions (all p < .05), except for linguistic semantic memory, recent general semantic memory, historical general semantic memory and semantic plans.

Fig. 1. Participants’ performance in the Confabulation Battery. The subdivision within each bar indicate what proportion of responses were classified as correct, confabulation, wrong and “I don’t know”, for each type of responses in Alzheimer’s disease patients (AD), confabulating amnesics patients (CA), and normal controls (NC).

A significant interaction was observed for group by type of question [F(20,250) = 4.7; p < .001].

NC produced significantly fewer correct responses for historical general semantic memory questions than for all other types of questions (all p < .05). AD patients produced significantly more correct responses for personal semantic memory and linguistic semantic memory than for all other types of questions (all p < .05). They also produced significantly fewer correct responses for episodic memory and recent general semantic memory than for contemporary general semantic memory (both p < .05). CA patients produced significantly more correct responses for personal semantic memory than for episodic memory, recent general semantic memory, contemporary general semantic memory, and episodic plans (all p < .05). They also produced fewer correct responses for episodic memory than for orientation in time and space and linguistic semantic memory (both p < .05). and for episodic plans than orientation in time and place and linguistic semantic memory (both p < .05).

The percentage of confabulations was entered in a two way ANOVA with group (AD vs. CA) as between-subjects factor and type of question (the CB’s 11 types of question) as repeated measures factor. Results indicated a main effect for group [F(1,16) = 35.4; p < .01] and for type of question [F(10,160) = 7.5; p < .001]. Post hoc analysis (Scheffe’s F corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons) revealed that CA patients confabulated significantly more than AD patients for all types of questions (all p < .05), except for semantic plans and “I don’t know” questions, both semantic and episodic.

A significant interaction was observed for group by type of question [F(10,160) = 6.5; p < .01].

AD patients confabulated significantly more only in episodic memory compared with personal semantic memory (p < .05), whereas CA patients confabulated significantly more in episodic memory and episodic plans than in any other condition (all p < .01).

Types of Confabulations

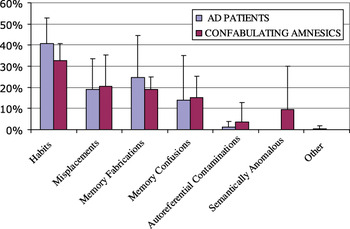

Overall, AD patients and CA produced 146 and 278 confabulations, respectively. The mean percentage of each type of confabulation for each group of patients is reported in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Mean percentage of different confabulation types in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and confabulating amnesics patients (CA) patients.

Both patients’ groups produced more HC confabulations than of any other type. HC accounted for 41% and 32% of confabulation in AD patients and CA, respectively. An example of HC confabulation is provided by patient PD. To the question “How did you spend last Christmas?” PD answered “Last Christmas? During the day we prepared… we opened oysters, we ate prawns, shrimps, turkey, chestnuts, some French fries, salad, cheese, fruits, a little ‘bûchette’. We gave the presents to the children, we participated in the games… we had to do something. We played dominos”. This example shows that PD, when confabulating, recalls a “general” Christmas as a specific one. Instead of recalling what she did specifically during the previous Christmas, she recalls what she has probably done on many Christmas days throughout her life.

Misplacements confabulations accounted for 19% and 20% of confabulation in AD patients and CA, respectively. An example of this type of confabulation is the following: to the question “What happened in Nuremberg?” patient PD answered “There was a criminal trial against the Nazis, 4 years ago.” In this case, a true episode and a correct memory are misplaced in time.

Memory Fabrications accounted for 24% and 18% of AD’s and CA’s confabulations, respectively, and Memory Confusions accounted for 14% and 15% of AD’s and CA’s confabulations, respectively. Autoreferential Contaminations and Semantically Anomalous confabulations were less than 10% in both patients’ groups, with the exception of one CA patient, who produced 25 Semantically Anomalous confabulations of a total of 42 confabulations.

The percentage of the different types of confabulations was entered in a two-way ANOVA with group (AD vs. CA) as between-subjects factor and type of confabulation as repeated measures. Results indicated a main effect for type of confabulation [F(6,96) = 1; p < .001], but no significant main effect for group. Moreover results indicate no group by type of confabulation significant interaction.

Both patients’ groups produced significantly more confabulations of the HC type than of any other type (all p < .01).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described the performance of a group of mild AD patients and a group of CA on the CB, a set of questions involving the retrieval of various kinds of semantic and episodic information. The aim of the study was to quantify and qualify confabulations in our patients. In particular, based on previous clinical and experimental observation, we predicted that HC would contribute to confabulations more than other types of confabulatory responses.

Consistent with our prediction, the main finding of this study demonstrates that the most frequently our patients’ confabulations consisted of HC. Other types of confabulations were also present, but contributed much less than HC to the total number of confabulatory responses. Interestingly, both patients’ groups showed the same pattern of confabulations. AD patients confabulated significantly less than CA patients and can be considered “mild” confabulators. However, the relative contribution of the different types of confabulations was the same in AD and CA, with the exception of Semantically Anomalous confabulations that were present only in CA. Semantically Anomalous confabulations in our present classification are sometimes described in the literature as “fantastic”, “bizarre”, or “implausible” (Baddeley & Wilson, Reference Baddeley, Wilson and Rubin1986; Berlyne, Reference Berlyne1972; Stuss, Alexander, Lieberman, & Levine, Reference Stuss, Alexander, Lieberman and Levine1978; Weinstein & Lyerly, Reference Weinstein and Lyerly1968) and are often considered to belong to the “spontaneous” domain of the provoked/spontaneous dichotomy (Kopelman, Reference Kopelman1987). Our present results show that this type of confabulation is quite infrequent (only 31/424 in this study) and that it can be provoked by specific questions.

The great majority of confabulations in this study fall into four categories, HC, Misplacements Confabulations, Memory Fabrications, and Memory Confusions. These types of confabulations clearly differ in their type of content, which consists of habits, repeated memories in HC, of temporo-spatial misplacements of true episodes, of episodes that never happened to the subject, or in confusions between true episodes or people in the other types of confabulation. These differences may reflect the involvement and disruption of different cognitive processes and possibly different underlying neural substrates. However, these confabulations also show commonalities in that they all show a plausible content. In other words, a hypothetical observer faced to these types of confabulations, could never recognize them as such, unless he or she is aware of the personal history, background, and present situation of the individual who produces them.

In this study, we based our analysis on the confabulation’s content. This led us to identify six major types of confabulations, with one, HC, by far more frequent than the other types. Five of the six types we identified are plausible and semantically appropriate, and one is semantically anomalous. The results of this analysis expand the distinction between semantically appropriate and semantically anomalous confabulations (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba1993a) indicating that within semantically appropriate confabulations further subtypes can be identified.

The taxonomy we propose here is not necessarily alternative to the spontaneous/provoked distinction, which, at a general level of description, remains useful in identifying two entities that can be considered the two extremities of an otherwise rich spectrum of phenomena.

The relationship between the classification we propose here and that proposed by Schnider (Reference Schnider2008) seems more problematic. In fact, if Semantically Anomalous confabulations in our classification may correspond to Schnider’s fantastic confabulations, the other types of confabulations we described are hardly captured by Schnider’s classification. However, in our understanding, Schnider’s classification is meant to be more clinical than content based. In other words, it is aimed at identifying different types of confabulators rather than different types of confabulations. Then, if this is the case, our classification can be applied to each subtype of confabulator described in Schnider’s. Yet, there is still a problem with this type of account. In our study patients with different pathologies and different types and sites of lesion showed, with little variance, the same pattern of confabulation. In particular, regardless their clinical diagnosis, their brain pathology or their lesion’s site, all patients produced by far more HC than other types of confabulations. This, which is actually the main result of our study, indicates that, regardless the underlying pathology, confabulation largely reflects the individual’s tendency to consider habits, routines and over-learned information as unique episodes. And this tendency is not limited to the retrieval of past information but also involves the planning of the future. In fact, based on personal habits, patients who are hospitalized may confabulate in planning their personal future by saying, for example, that the following day they will go to work. This shows that confabulation is not a “pure” memory disorder, but rather a pathological condition that involves the individual’s temporality, or, in our terminology, Temporal Consciousness (TC), that is, being conscious of one’s own past, present, and future (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba, Markowitsch and Nilsson1999, Reference Dalla Barba and Tulving2000, Reference Dalla Barba2001, Reference Dalla Barba2002, Reference Dalla Barba and Hirstein2009; Dalla Barba & Boissé, Reference Dalla Barba and Boissé2010; Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, et al., Reference Dalla Barba, Cappelletti, Signorini and Denes1997).

According to the Memory, Consciousness, and Temporality Theory (MCTT) (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba2002), in confabulating patients TC is still there, as in normal subjects. In other words, their faculty of mental time travel (Suddendorf & Corballis, Reference Suddendorf and Corballis2007) is preserved. At difference with non-confabulating amnesics who do not have TC and are lost in a permanent instantaneous present, confabulating patients can still remember their past, they are present to a world, and can project themselves into a personal future. The difference between non-confabulating amnesics and confabulating amnesics is not in their amnesic status, because they both have severely impaired memory, but in the expression of this status. In non-confabulating amnesic, memory impairment is characterized by “negative” symptoms, loss of TC, that is, their complete inability to remember their past, be oriented in their present world and project their personal future. In contrast, in confabulating amnesics, memory impairment is characterized by “positive” symptoms, preserved TC, that is, their preserved ability to remember their past, be oriented in their present world and project their personal future. However, in doing this, these patients make errors, sometimes frankly bizarre errors. Actually what is happening in these patients is that TC is still there but is not interacting with less stable patterns of modification of the brain, because these modifications are abolished or inaccessibleFootnote 1. Most frequently the result of this condition is that personal habits and routines are considered in a personal temporal framework. When asked what they have done the previous day or what they are going to do the following day, confabulating patients typically answer with memories and plans that they usually have in their daily life. Although admitted to the hospital, they will say, for example, that the previous day they went out shopping and that the following day they will be visiting some friends, acts that presumably were part of their routine life. According to the MCTT, in this condition TC interacts with more stable patterns of modification of the brainFootnote 2 and addresses routines and repeated events as unique past event (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Confabulation according to the Memory, Consciousness, and Temporality Theory (Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba2002). NS = nervous system; X, Y, Z = less stable (X), more stable (Z) patterns of modification of the nervous system; TC = temporal consciousness; KC = knowing consciousness. Arrows indicate the succession order of phenomena from events to consciousness in normal and confabulating memory.

The condition we have sketched here (but see Dalla Barba, Reference Dalla Barba2002, Reference Dalla Barba and Hirstein2009; Dalla Barba & Boissé, Reference Dalla Barba and Boissé2010 for more detailed descriptions) accounts for what we indicated with HC confabulations.

Suddendorf and Corballis (Reference Suddendorf and Corballis2007) suggested that TC (mental time travel in their terminology) has an adaptive advantage and contributes to future survival because it allows to shape future events and to develop anticipatory behavior. However, the preservation of TC is not itself an adaptive advantage, because it may lead to inappropriate anticipatory behavior when it interacts with inappropriate information. Indeed this is what happens in confabulating patients, who, even more than non-confabulating amnesics, are exposed to the risk inappropriate behavior.

To conclude, the qualitative account and the taxonomy of confabulations we propose here fits the MCTT, but it is not incompatible with other theories, which consider the construction of a coherent notion of subjective time a crucial step to understand the more evolved aspects of human memory. The MCTT shares similarities with Tulving’s notion of autonetic consciousness (Tulving, Reference Tulving1985), with the concept of mental time travel (Suddendorf & Corballis, Reference Suddendorf and Corballis2007) and with Schnider’s theory of extinction as a necessary component to adapt to ongoing reality and to anticipate future events. Future research should focus on cognitive and biological mechanisms that enable individuals to have and adapt their subjective time to past, present, and future reality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are no conflicts of interest and no source of financial support. The information in this manuscript and the manuscript itself has never been published either electronically or in print.