Introduction

The rapid graying of the U.S. population and the attendant increase in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) has heightened public and scientific interest in identifying ways to maintain cognitive vitality and prevent the onset of dementia. Cognitively stimulating leisure activities have been reported to be associated with reduced risk of developing dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) syndromes (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003; Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, LeValley, Derby, Kuslansky, Katz, Hall and Lipton2006). However, not all studies have found these associations (Aartsen, Smits, van Tilburg, Knipscheer, & Deeg, Reference Aartsen, Smits, van Tilburg, Knipscheer and Deeg2002).

Empirical support for the amount of mental activity and its role in influencing rate of mental ageing is yet to be conclusively demonstrated. The role of crossword puzzles in preventing cognitive decline is of particular interest given their wide availability (newspapers, books, and the Internet), easy accessibility, and minimal cost. The U.S. census bureau reported that 14 to 16% of the adult population did crossword puzzles, with at least half of the puzzlers doing it at least two or more times a week (United States Census Bureau, 1998, 2008). Fifteen percent of participants in the Bronx Aging study (BAS) reported doing crossword puzzles; supporting this pastime's popularity among older populations (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003; Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, LeValley, Derby, Kuslansky, Katz, Hall and Lipton2006). Although attempting to solve crossword puzzles is frequently mentioned and recommended in the popular press as a mentally stimulating activity, there is surprisingly little empirical support for their role in influencing the rate of cognitive aging.

Crossword puzzles might reduce risk of cognitive decline via their effect on improving cognitive reserve, direct disease modification effects, or they may be a marker for other healthy behaviors (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003; Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, LeValley, Derby, Kuslansky, Katz, Hall and Lipton2006). The cognitive reserve hypothesis suggests that some individual characteristics such as participation in cognitively stimulating activities or education result in maintenance of cognitive function in the face of accumulating dementia pathology in the brain (Katzman, Reference Katzman1993; Stern, Reference Stern2009). In support of this hypothesis, we have previously reported that subjects who participated frequently in cognitively stimulating leisure activities had a later onset of cognitive decline and more rapid post-onset cognitive decline (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009). Crossword puzzles are a learned skill but related to education; although not all educated people are active puzzlers. Therefore, studying crosswords provides a way to study if proficiency in a specific learned skill rather than education in general (which could have other confounders like occupation) can have an effect on cognitive decline.

Herein, we analyzed if participation in crossword puzzles affected the trajectory of memory decline in 101 Bronx Aging Study (BAS) participants who ultimately developed dementia. Specifically, we use change point models to ascertain whether the onset of accelerated memory decline (the change point) was delayed in crossword puzzle players and how the rate of memory decline after the change point was affected (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009).

Methods

Study Population

The Bronx Aging Study cohort included 488 healthy community-dwelling individual volunteers living in Bronx County, New York, enrolled between 1980 and 1983. Study design, methods, and demographics have been previously described (Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Hall, Kuslansky, Katz and Buschke2002, Reference Verghese, LeValley, Derby, Kuslansky, Katz, Hall and Lipton2006; Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009). The study enrolled English-speaking subjects between 75 and 85 years of age. Exclusion criteria included previous diagnoses of idiopathic Parkinson's disease, liver disease, alcoholism, or known terminal illness; severe visual and hearing impairment interfering with completion of neuropsychological tests; and presence of dementia. The inception cohort was middle class, 90% white, and 64.5% women. This analysis includes 101 study participants who were cognitively normal at baseline, reported their formal education and participation in leisure activities at baseline, and developed incident dementia during follow-up. The local institutional review board approved the study protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and surrogate decision makers at enrollment.

Cognitive Evaluation

An extensive battery of validated neuropsychological tests was administered to all participants at all study visits and was used to inform dementia diagnosis at case conferences (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003). For the purposes of this study, we examined performance on the Buschke Selective Reminding Test (SRT) (Buschke, Reference Buschke1973; Buschke & Fuld, Reference Buschke and Fuld1974), a word list memory test that was not used as part of the diagnostic process. The sum of recall on the SRT has been reported to predict incident dementia in this cohort (Masur et al., Reference Masur, Fuld, Blau, Thal, Levin and Aronson1989; Masur, Fuld, Blau, Crystal, & Aronson, Reference Masur, Fuld, Blau, Crystal and Aronson1990; Masur, Sliwinski, Lipton, Blau, & Crystal, Reference Masur, Sliwinski, Lipton, Blau and Crystal1994). Episodic memory problems including delayed free recall and recognition are prominent in early AD, the most common subtype of dementia in older patients (Greene, Baddeley, & Hodges, Reference Greene, Baddeley and Hodges1996; Wilson, Bacon, Fox, & Kaszniak, Reference Wilson, Bacon, Fox and Kaszniak1983) unlike normal older adults (Munro Cullum, Butters, Troster, & Salmon, Reference Munro Cullum, Butters, Troster and Salmon1990; Salthouse, Fristoe, & Rhee, Reference Salthouse, Fristoe and Rhee1996). In a previous study in the same cohort using similar change point methods to the current study, we have also reported that accelerated decline in memory processes occurs earlier than decline in other non-memory cognitive processes (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ying, Kuo, Sliwinski, Buschke, Katz and Lipton2001).

Dementia Diagnosis

At study visits, subjects with suspected dementia received a clinical workup, including CT scans and blood tests to rule out reversible causes of dementia. Triggers for workup for reversible or underlying causes of dementia during the follow-up visits included reports of new or progressive memory or other cognitive complaints by the subjects or caregivers during study visits, observations made by study clinicians during the clinical and neurologic evaluations, Blessed test performance (Blessed, Tomlinson, & Roth, Reference Blessed, Tomlinson and Roth1968) increase of four or more points since the previous visit or more than eight errors on the current visit), and a pattern of worsening scores (cutoff scores not used) on the neuropsychological test battery compared to previous visits. As noted above, the SRT score was not used as part of the diagnostic process.

A diagnosis of dementia was assigned at case conferences attended by study neurologist, neuropsychologist, and a geriatric nurse clinician, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, and the revised third edition criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1987). Updated criteria for dementia and subtypes were introduced after the study launch. To ensure uniformity of diagnosis, all cases in the inception cohort were re-conferenced in 2001 by a neurologist and a neuropsychologist who did not participate in diagnostic conferences from 1980 to 1998 (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003). The diagnosticians had access to all available information for each subject at the conference, including results of any investigations done at or following the study visit when dementia was diagnosed. Disagreements between raters were resolved by consensus after presenting the case to a second neurologist.

Leisure Activities and Crossword Puzzles

At baseline, participants were interviewed about participation in six cognitive leisure activities (reading, writing, crossword puzzles, board or card games, group discussions, or playing music). We coded self-reported frequency of participation to generate a scale on which one point corresponded to participation in one activity for 1 day per week. For each activity, subjects received seven points for daily participation; four points for participating several days per week; one point for weekly participation; and zero points for participating occasionally or never. For this analysis, we report CAS scores excluding participation in crossword puzzles, which was independently examined as the main predictor for this analysis. We summed activity days across the remaining five activities to generate a Cognitive Activity Scale (CAS) for each participant (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003) CAS scores ranged from 0 (does not participate in any activity) to 35 (daily participation in all 5 activities excluding puzzles). For instance, a subject who read daily (7 points) and played chess 3–4 days per week (4 points) would receive a total score of 11 points. We have reported that CAS scores were not correlated with age (Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003).

We tested various metrics for quantifying crossword puzzle playing that incorporated frequency of participation in our preliminary analyses. However, the results using these scales were not materially different using self-reported history of crossword puzzle playing (irrespective of frequency). Hence, for ease of interpretation the predictor reported is self-reported history of crossword puzzle playing at baseline study visit.

Pathology

Thirteen participants (3 crossword puzzlers) from this dementia study sample received brain autopsies. Senile plaques (SP) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) were counted in mid-frontal, temporal, parietal, hippocampal, and subcortical regions with thioflavin-S fluorescent microscopy as previously described (Verghese, Buschke, et al., Reference Verghese, Buschke, Kuslansky, Katz, Weidenheim, Lipton and Dickson2003).

Statistical Methods

We modeled scores on the SRT as a function of the subjects’ self-reported participation in crossword puzzles, and time before diagnosis of dementia (measured in years) for each subject contributing observations to the analysis. The basic conceptual model assumes that memory as measured by the SRT declines at a constant (possibly non-significant) rate before some unknown change point (presumed to be several years before dementia diagnosis), after which the decline would be more rapid. This assumption is supported by theory (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Doody, Kurz, Mohs, Morris, Rabins and Winblad2001) and by previously reported findings from this cohort (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Derby, LeValley, Katz, Verghese and Lipton2007, Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009) and elsewhere (Wilson, Beckett, Bienias, Evans, & Bennett, Reference Wilson, Beckett, Bienias, Evans and Bennett2003). The rates of memory decline were also assumed to be constant in time but random effects were used to allow that rate to vary across individuals. The expected SRT score at the change point, and the rates of decline before and after the change point were estimated from the data. The change point and the rates of decline before and after were allowed to vary as a function of self-reported participation in crossword puzzles. Interaction terms were included in the model to allow the rates of cognitive decline before and after the change point to vary as a function of crossword puzzle participation. We also fit a similar model in which both crossword puzzle participation and education were allowed to affect the change point and the rates of cognitive decline to consider the possibility that one of the two measures may confound or mediate the effect of the other. We used a similar approach to study potential confounding by participation in cognitive activities other than crossword puzzles. To account for baseline differences in cognitive status among puzzlers and non-puzzlers, we conducted a subgroup analysis restricted to participants with baseline verbal IQ scores of 95 and higher (excluding participants with scores in the lowest quartile).

If the change point were known a priori, the model would be a linear model in the unknowns; however, the unknown change point makes this part of a class of statistical models called nonlinear mixed effects models (Lindstrom & Bates, Reference Lindstrom and Bates1990). Maximum likelihood, assuming normal distributions for the SRT scores and the random effects, was used to estimate all model unknowns, using the SAS procedure NLMIXED (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Missing clinic visits were assumed to be at random, and Akaike's information criterion (Akaike, Reference Akaike1974) was used to assess whether the random effects added to the model fit.

For the exploratory clinicopathological study, we compared markers of Alzheimer pathology in mid-frontal, temporal, parietal, hippocampus, and parahippocampus regions in participants who did and did not play crossword puzzles using descriptive statistics (Altman, Reference Altman2006).

Results

The 101 study participants contributing data to these analyses averaged 79.5 years of age at baseline (range, 73.4–87.4 years). Sixty-two percent of participants were women, and 91% were non-Hispanic whites. The mean score on the Buschke SRT at baseline was 32.8 (standard deviation, 10.8). The mean time to dementia diagnosis was 5.0 years (maximum, 15.9 years), a total of 505 person-years of follow-up over 351 clinic visits.

Forty-seven of the participants were classified at consensus diagnostic conferences as probable or possible AD, 25 as probable or possible vascular dementia, 23 as mixed dementia, and 6 as other subtypes (2 Lewy body dementia, 1 Pick's disease, 2 vitamin B12 deficiency, 1 Parkinsonian dementia). Participation in crossword puzzles at baseline was not associated with the age at which dementia was diagnosed (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographics and cognitive test performance of study participants stratified by crossword puzzle participation at baseline

BIMC = Blessed Memory-Information-Concentration test; SRT = Buschke Selective Reminding Test.

Table 1 lists demographics of the 101 participants by reported crossword puzzle participation. Seventeen subjects reported playing crossword puzzles, with the frequency ranging from less than once per week in nine participants, once per week in two, 2–6 days per week in one, and daily in five participants. There were no significant differences in age or sex distribution between the crossword puzzle players and remaining subjects. Crossword puzzlers had non-significantly higher mean education level than non-puzzlers. Crossword puzzle players also had significantly higher mean estimated Verbal IQ scores compared to controls. While the mean CAS scores (for participation in the five leisure activities other than crossword puzzles) were higher in crossword players, the group difference was not significant. The median CAS scores in both groups were 7 activity days.

Table 2 shows the results for the change point model. Effect of crossword puzzles is reported in terms of self-reported participation at baseline. Participation in crossword puzzles resulted in a 2.54 years delay in the beginning of accelerated memory decline, but once the decline began, the rate of decline was 3.31 SRT points per year more rapid for crossword puzzlers than for non-puzzlers. Participants who had reported doing crossword puzzles had non-significantly better scores on the SRT at their later change point (39.01 vs. 34.92; p = .16). The mean SRT score at the time point when dementia was diagnosed was similar in the puzzlers and non-puzzlers (23.67 vs. 24.05; p = .13) because of the much more rapid memory decline in the puzzlers after the change point.

Table 2 Estimates from change point model.

SRT = Buschke Selective Reminding Test.

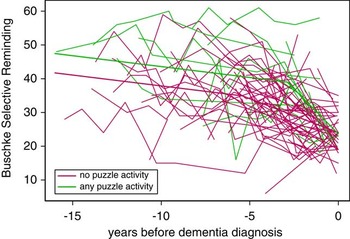

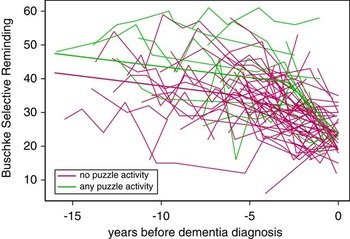

Figure 1 shows the relationship between crossword puzzle participation and the natural history of memory. Figure 1 compares the expected trajectory of memory function for a typical study participant who did crossword puzzles to a typical participant who did not do crossword puzzles. The former participant would have experienced accelerated decline beginning 2.88 years before diagnosis, whereas the latter participant would have experienced accelerated decline beginning 5.42 years before diagnosis.

Fig. 1 Memory performance as a function of time and crossword puzzle participation. Narrow lines show individual participants’ repeated scores on the Buschke Selective Reminding Test (SRT) over time; crossword puzzlers are shown in green and non-puzzlers in red. The wide lines show the expected trajectories for a hypothetical participant from both groups.

We considered the effect of education, which has previously been shown to influence cognitive trajectory of preclinical dementia in this sample (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Derby, LeValley, Katz, Verghese and Lipton2007). Specifically, we considered a model in which both education and crossword puzzle participation could affect the change point and the rate of post-change point decline, comparing it to models including only education, and only crossword puzzle participation. In the model with both education and puzzle participation, only puzzles were associated with either a delay in the onset of cognitive decline and an increase in the post-acceleration rate of decline; the addition of education did not improve model fit compared to a model with just puzzle participation (likelihood ratio test statistic = 0.9 with 3 degrees of freedom; p = .83). However, adding puzzle participation to a model with just education significantly improved the fit (likelihood ratio test statistic = 14.0 with 3 degrees of freedom, p = .003). Inclusion of cognitive activity other than crossword puzzles into the model did not improve model fit (likelihood ratio test statistic = 0.4 with 2 degrees of freedom; p = .82).

In a subgroup analysis restricted to the 15 puzzlers and 55 non-puzzlers with baseline verbal IQ scores of 95 or higher, the differences in cognitive trajectories were even more marked than the primary analysis. The difference between change points was 4.02 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.74–6.29) and the difference between post-change point rates of decline was 3.98 points/year (95% CI, 0.80–7.17).

As the puzzlers and non-puzzlers differed in baseline verbal IQ (Table 1), we matched the puzzlers to non-puzzlers on verbal IQ and repeated the analyses. This subgroup contained 14 puzzlers and 14 non-puzzlers matched by verbal IQ. When there were several possibilities for an exact match we selected the non-puzzler with the longest follow-up. The results are very consistent with the results from the entire dataset, as expected, with a change point for non-puzzlers 5.80 years before dementia diagnosis and a change point for puzzlers 2.95 years before dementia diagnosis. As expected, the small sample resulted in wide confidence interval estimates; although the difference was not statistically significant, the magnitude of the difference was larger than for the full cohort analysis. Addition of education terms to the model resulted in only minor differences in the estimates and did not significantly improve the model fit (likelihood ratio test p value .98).

Pathology

Subjects who did and did not take part in crossword puzzles were not significantly different in terms of age, sex, education, and interval from last visit to death. There were also no significant differences between the 3 crossword puzzlers and 10 non-puzzlers in mean brain weight as well as NFT and senile plaque counts in the brain regions analyzed in our study.

Discussion

We had previously reported that participation in cognitively stimulating leisure activities delayed the onset of accelerated cognitive decline using the Buschke Selective Reminding Test as a measure of memory performance in the same sample of older adults with dementia (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009; Verghese, Lipton, et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Katz, Hall, Derby, Kuslansky and Buschke2003). Building on this observation, we selected crossword puzzles, a popular cognitively stimulating leisure activity, and report their independent effect on memory decline. Participation in crossword puzzles delayed the onset of accelerated memory decline in subjects who developed dementia by 2.54 years compared to non-puzzlers. However, once the memory decline began, the rate of decline was 3.31 SRT points per year more rapid for crossword puzzlers compared to non-puzzlers. This pattern of findings for memory decline supports the cognitive reserve hypothesis, which postulates that cognitively stimulating activities may help delay the emergence of clinical cognitive deficits. But once the cognitive reserve is no longer able to compensate for the increasing pathological brain damage the rate of cognitive decline is more rapid (Stern, Reference Stern2009).

Relative sparing of skills such as ability to play music or games has been described even in patients with advanced AD (Cowles et al., Reference Cowles, Beatty, Nixon, Lutz, Paulk, Paulk and Ross2003; Baird & Samson, Reference Baird and Samson2009), which could result from enhanced cognitive reserve or sparing of brain areas serving these skills by disease pathology. Similarly, the medial temporal structures affected early in the course of AD do not appear to be critical in preserving ability to do crossword puzzles (Skotko, Rubin, & Tupler, Reference Skotko, Rubin and Tupler2008) and mental representations learned previously could help anchor new semantic knowledge (Skotko et al., Reference Skotko, Kensinger, Locascio, Einstein, Rubin, Tupler and Corkin2004). We also note the case of the famous amnesiac patient, H.M., who lost his ability to remember new events and facts after bilateral medial temporal resection during epilepsy surgery; strikingly, his language ability and performance of standard motor tasks acquired before surgery remained intact (Corkin, Reference Corkin1984). H.M. was also a crossword puzzle aficionado, able to use his intact memory for word meanings as long as the questions and the place in the puzzle remained in front of his eyes (Markowitsch & Pritzel, Reference Markowitsch and Pritzel1985). It is, therefore, possible that skills relating to crossword puzzle performance could be preserved despite early Alzheimer related pathology in the medial temporal lobe and help mediate improved cognitive function in related functional tasks. In this context, general knowledge but not abstract reasoning ability was reported to be the strongest predictor of crossword puzzle proficiency (Hambrick, Salthouse, & Meinz, Reference Hambrick, Salthouse and Meinz1999).

According to the cognitive reserve hypothesis we might expect that puzzlers in our sample would manifest more Alzheimer pathology in their brains for the same level of cognitive impairment (Roe, Xiong, Miller, & Morris, Reference Roe, Xiong, Miller and Morris2007; Stern, Reference Stern2009). However, our small clinicopathological sample is limited in clarifying the role of crossword puzzles in influencing neuropathological burden in the face of progressive dementia, and should be followed up in a larger study. It is also possible that the role of crossword puzzles in influencing cognitive reserve may have its mark on other variables not measured in our present sample, such as changes in synaptic density (Katzman, Reference Katzman1993) and this also needs to be further investigated in future clinicopathological studies.

In our previous study (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lipton, Sliwinski, Katz, Derby and Verghese2009), participation in cognitively stimulating activities remained significant after education was added as a predictor of the change point and the rate of decline, and education did not significantly add to the fit of the model in our analyses. We, therefore, hypothesize that the effect of early life education could be mediated through late life participation in cognitively stimulating activities. In the current study, the influence of crossword puzzle participation on memory decline also remained after accounting for education as well as participation in cognitive activities other than crossword puzzles. Different cognitive leisure activities may vary in their degree of influence on memory decline with strong effects seen for crossword puzzle participation in our study.

Crossword puzzlers had higher verbal IQ compared to non-puzzlers at baseline even as both groups had comparable years of education. Hence, another possible explanation for our findings is that crossword puzzle participation in seniors is a marker for cognitive reserve measures such as Verbal IQ. However, in a subset analysis in which participants were matched for verbal IQ, results were similar to that in the full cohort and again education did not significantly add to the model fit. Thus neither education nor verbal IQ appears to confound the effect of crossword puzzle participation on the trajectory of memory decline in our cohort. Rather, in people who do crossword puzzles, measures of education and verbal IQ do not significantly improve our estimates of cognitive reserve. As this is an observational study, we cannot rule out that crossword puzzle participation is the mediator through which education protects against early acceleration of cognitive decline in preclinical dementia.

The change point model assumes a discrete point of decline in the preclinical stages of dementia. On the other hand, terminal cognitive decline has been reported in AD using other statistical methods (Laukka, MacDonald, & Bäckman, Reference Laukka, MacDonald and Bäckman2006; Small & Bäckman, Reference Small and Bäckman2007). While longitudinal studies widely use chronological age or time since enrollment, these methods to describe trajectories do not define the relationship between increasing brain pathology and cognitive changes well (Steinerman, Hall, Sliwinski, & Lipton, Reference Steinerman, Hall, Sliwinski and Lipton2010). For instance, individuals with the same age may be at different disease stages and the results could reflect mixed effects of disease and normal aging changes.

Our sample size was limited and did not permit us to examine subtypes of dementia. Participation in crossword puzzles was associated with delayed onset of accelerated memory decline even though the activity was modeled using only at a single point in time. Preliminary analyses using different metrics of frequency of crossword puzzle participation did not materially change our results. Hence, any level of participation in crossword puzzles was combined into a single measure for ease of interpretation of results. Excluding puzzlers with less than weekly frequency or classifying these subjects as non-puzzlers would have reduced power to detect meaningful differences in this small sample. Classifying puzzlers with less than weekly frequency as non-puzzlers would also have been problematic as in our ongoing studies most subjects report participating in these types of leisure activities for many years (Verghese, Reference Verghese2006). Hence, a lower reported frequency at study entry does not preclude a long-term effect of engaging in this activity. However, the wide variability in the type, experience, and frequency of participation in crossword puzzles among our subjects, which might influence cognitive decline, was not accounted for in our analyses. Thus the self-report at baseline was probably a quite imperfect measure of crossword puzzle participation later in life, and the actual effect of participation in crossword puzzles might be stronger than those we observed. It has been reported that crossword puzzle proficiency is influenced by general knowledge but not by reasoning ability (Hambrick et al., Reference Hambrick, Salthouse and Meinz1999). A subsequent analysis including the study by Hambrick and colleagues concluded that there was no evidence of slower rate of age-related decline in reasoning, or a greater age-related increase in knowledge, for crossword puzzlers (Salthouse, Reference Salthouse2006). However, comparisons to our study might be limited by the wide age range (age 18 and higher), cognitively normal sample, and cross-sectional design of this previous study (Hambrick et al., Reference Hambrick, Salthouse and Meinz1999, Salthouse, Reference Salthouse2006). While we controlled for several potential confounders in our analyses such as baseline cognitive status, education, and participation in other cognitive activities, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual or unmeasured confounding given the observational nature of the study.

Given the widespread popularity of crossword puzzles in all age groups, it is encouraging that our results support a possible role of this easily accessible pastime in cognitive decline with aging. As is the case with any cohort study the results indicate that the cause (crossword puzzle participation) precedes the effect (cognitive decline) but more conclusive proof will require clinical intervention trials to further test this association.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (J.V., RO1 AGO25119) and the Einstein Aging Study (PI: RL, PO1 AGO3949). No conflict of interest. Funding disclosed in Acknowledgments.