INTRODUCTION

Regular cannabis use exerts changes in brain structure (Ceccarini etal., Reference Ceccarini, Kuepper, Kemels, Van Os, Henquet and Van Laere2015; Lorenzetti, Chye, Silva, Solowij, & Roberts, Reference Lorenzetti, Chye, Silva, Solowij and Roberts2019; Rocchetti etal., Reference Rocchetti, Crescini, Borgwardt, Caverzasi, Politi, Atakan and Fusar-Poli2013) and neurofunctional connectivity (Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018), negatively affecting cognitive function (Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018), such as memory (Prini etal., Reference Prini, Zamberletti, Manenti, Gabaglio, Parolaro and Rubino2020; Schoeler etal., Reference Schoeler, Kambeitz, Behlke, Murray and Bhattacharyya2016). Chronic and long-term cannabis exposure may exert differential, region-specific effects in brain areas enriched with cannabinoid receptors, such as the hippocampus, orbitofrontal cortex volume (Lorenzetti etal., Reference Lorenzetti, Chye, Silva, Solowij and Roberts2019; Yanes etal., Reference Yanes, Riedel, Ray, Kirkland, Bird, Boeving and Sutherland2018), and decreased activation in the anterior cingulate cortex and in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Chang, Yakupov, Cloak, & Ernst, Reference Chang, Yakupov, Cloak and Ernst2006). Some neurophysiological and behavioral changes seem to reverse after around 28 days of no cannabis use (Hirvonen etal., Reference Hirvonen, Goodwin, Li, Terry, Zoghbi, Morse and Innis2012; Krzyzanowski & Purdon, Reference Krzyzanowski and Purdon2019; Medina, Hanson, Schweinsburg etal., Reference Medina, Hanson, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007; Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, etal., Reference Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007). Moreover, the effect size for cognitive function decreases the longer the abstinence period is (Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018). Neuropsychological tests of attention in cannabis users have resulted in effect sizes below one-third of a standard deviation (Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018), however, less is known about the effect of cannabis use and cannabis dependence on systems of attention.

Attention is a cognitive function crucial to carry out our daily activities successfully (Han, Reference Han2017; Lundwall etal., Reference Lundwall, Dannemiller and Goldsmith2017). It allows us to selectively focus on relevant information from the environment (Han, Reference Han2017; Noudoost etal., Reference Noudoost, Chang, Steinmetz and Moore2010; Stevens & Bavelier, Reference Stevens and Bavelier2012). Performance in attention tasks is reduced by acute (Bocker etal., Reference Bocker, Gerritsen, Hunault, Kruidenier, Mensinga and Kenemans2010), long-term (Solowij, Michie, & Fox, Reference Solowij, Michie and Fox1991; Solowij etal., Reference Solowij, Stephens, Roffman, Kadden, Miller, Christiansen and Vendetti2002) cannabis use, as well as when cannabis use has begun in adolescence (Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally, & Dishion, Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Cengel etal., Reference Cengel, Bozkurt, Evren, Umut, Keskinkilic and Agachanli2018). It has also been reported that cannabis abstinence for at least 23 days in adolescent cannabis users still presented poorer attention efficiency relative to non-using control adolescents (Medina, Hanson, Schweinsburg, etal., Reference Medina, Hanson, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007); this effect was negatively related to lifetime cannabis use. Contrasting studies have failed to document cannabis-induced attention impairment (Chang etal., Reference Chang, Yakupov, Cloak and Ernst2006; Indlekofer etal., Reference Indlekofer, Piechatzek, Daamen, Glasmacher, Lieb, Pfister and Schütz2009; Rangel-Pacheco etal., Reference Rangel-Pacheco, Lew, Schantell, Frenzel, Eastman, Wiesman and Wilson2020; Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018; Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013). The inconsistency of these results may be due to the type of task used (Colizzi & Bhattacharyya, Reference Colizzi and Bhattacharyya2018), the differences among the samples evaluated, such as the frequency of cannabis use, the age at onset, total consumption time, whether the subject has developed cannabis dependence, or the time required for an abstinence period from cannabis. Some studies have overlooked that subjects use multiple other substances in addition to cannabis, including alcohol and tobacco, which may blur their findings. In fact, studies performed in heavy cannabis users and with no significant alcohol or other drug use are relatively scarce.

Three components or networks have been suggested to explain attention, by means of the Attention Network Test (ANT) (Petersen & Posner, Reference Petersen and Posner2012; Petersen etal., Reference Petersen, Posner and Petersen1990; Posner & Petersen, Reference Posner and Petersen1990): alerting, orienting, and executive control. The alerting system mains a responsive state to sensory demands; the orienting system confers the ability to efficiently direct attention to select the target stimuli; and the executive control system allows to resolve conflict among responses. ANT has helped to reveal alterations in attention networks in subjects suffering from internet addiction (Fu etal., Reference Fu, Xu, Zhao and Yu2018), binge drinking (Lannoy etal., Reference Lannoy, Heeren, Moyaerts, Bruneau, Evrard, Billieux and Maurage2017), autism (Mutreja etal., Reference Mutreja, Craig and O’Boyle2016), schizophrenia (Orellana etal., Reference Orellana, Slachevsky and Peña2012; Urbanek etal., Reference Urbanek, Neuhaus, Opgen-Rhein, Strathmann, Wieseke, Schaub and Dettling2009), and trait anxiety (Pacheco-Unguetti etal., Reference Pacheco-Unguetti, Acosta, Callejas and Lupiáñez2010). Likewise, some studies reported deficiencies only in the executive control system in adolescent cannabis users (Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Epstein & Kumra, Reference Epstein and Kumra2014), but others did not report any deficiencies (Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013); and have reported only that the earlier the age of regular cannabis use, less efficiency of the orienting system (Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013). A concern with all these studies is the small samples used and the assessment of the attention networks in adolescent cannabis users. However, in adult cannabis users, performing tasks that evaluate orienting (e.g., Chang etal., Reference Chang, Yakupov, Cloak and Ernst2006) and executive control (Rangel-Pacheco etal., Reference Rangel-Pacheco, Lew, Schantell, Frenzel, Eastman, Wiesman and Wilson2020) systems, independently, have shown no behavioral changes but altered brain activation (Chang etal., Reference Chang, Yakupov, Cloak and Ernst2006) and prefrontal–occipital connectivity (Rangel-Pacheco etal., Reference Rangel-Pacheco, Lew, Schantell, Frenzel, Eastman, Wiesman and Wilson2020) relative to control subjects.

On the other hand, cannabis dependence and abuse is usually comorbid with other substance use or dependence and it seems to result in confusions about its effect on cognitive function. For example, alcohol-dependent subjects with cannabis abuse had higher cognitive efficiency, than even the non-using control subjects and other alcoholic subgroups (Nixon, Reference Nixon1999). But alcohol and cannabis abuse/dependence were associated with changes in hippocampal asymmetry and abnormal verbal learning relative to controls (Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zaion, etal., Reference Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007); in contrast, methamphetamine and cannabis-dependent users scored intermediate in a global deficit neuropsychological test relative to controls and methamphetamine only dependent users (Gonzalez etal., Reference Gonzalez, Rippeth, Carey, Heaton, Moore, Schweinsburg and Grant2004).

Considering all these results, this work aimed: (1) to evaluate the integrity of the three attentional networks (alerting, orienting, and executive control systems) in a larger sample of adult cannabis users with recent use. Due to the region-specific effects in brain areas associated with the orienting and executive systems, we expect a detriment in the orienting and executive control systems; (2) to assess the effect of cannabis dependence on the attention networks. We expect a larger functional detriment on attention network systems in cannabis users with dependence; (3) to test if the effect of cannabis dependence on the attention networks can be explained by tobacco or alcohol dependence; and (4) finally, as previously reported, cannabis use characteristics have been associated with cognitive performance, such as age of onset of consumption (e.g., Meier etal., Reference Meier, Caspi, Ambler, Harrington, Houts, Keefe and Moffitt2012; Solowij etal., Reference Solowij, Jones, Rozman, Davis, Ciarrochi, Heaven and Yücel2011) or lifetime cannabis use (e.g., Lisdahl Medina, Schweinburg, Cohen-Zion, etal., Reference Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007), thus, we expect to detect associations with cannabis use characteristics negatively affecting the attention networks systems.

METHODS

Participants

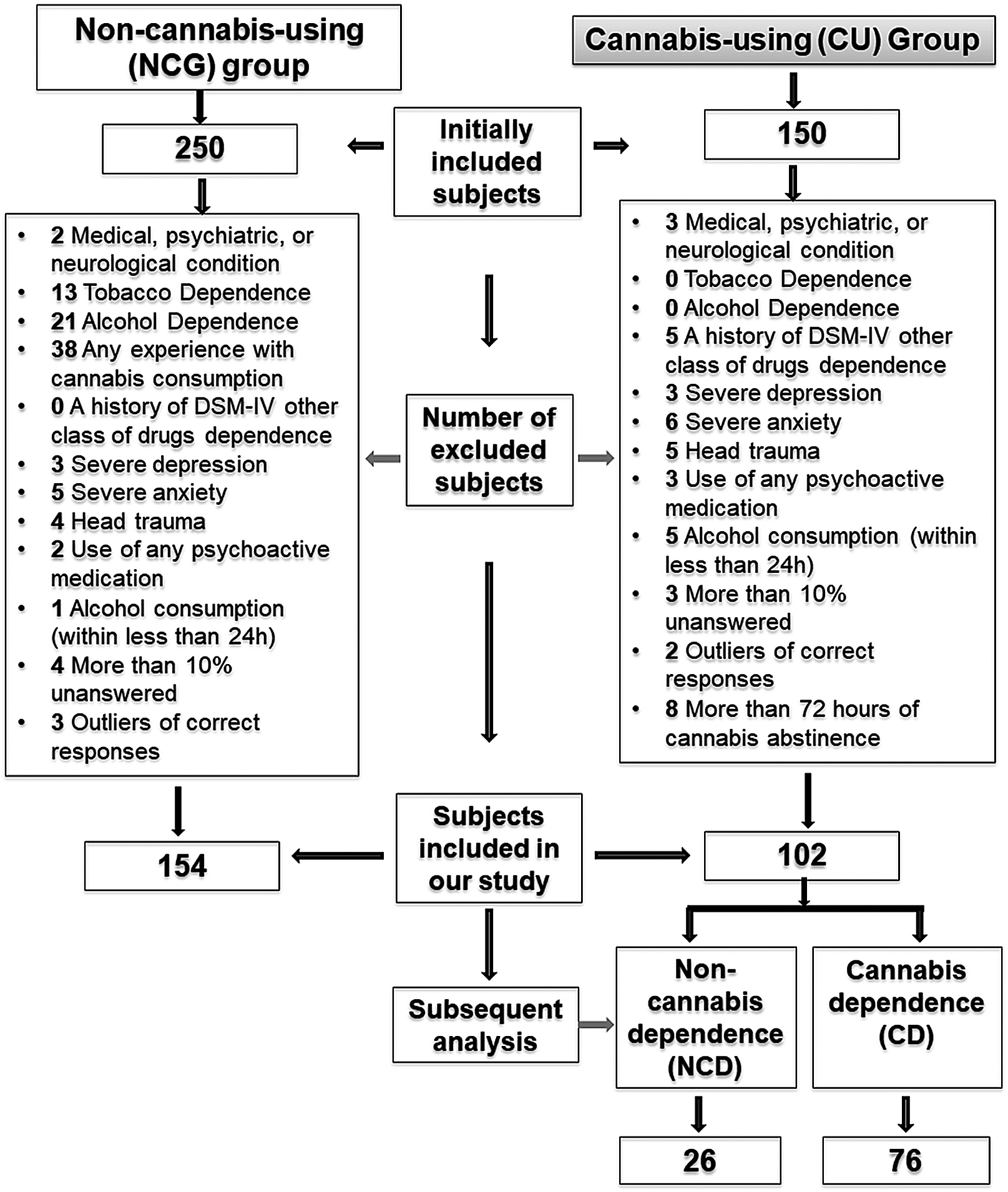

Initially, a convenience sample of 400 volunteers between 20 and 30 years old were recruited through printed advertisements in different areas through Mexico City and through social media (Facebook and e-mail). Due to the exclusion criteria (see further), 144 participants were excluded from the study, resulting in a sample size of 256 volunteers (Figure 1). The sample was divided into two main groups: the first one, the non-cannabis-using group (NCU: n = 154; 87 women; mean age 23.25 years, SD = 2.55); and the cannabis-using group (CU: n = 102; 48 women; mean age 22.66 years, SD = 2.76). All the participants were Mexican native Spanish speakers, right-handed (laterality was detected by the Edinburgh Inventory (Oldfield, Reference Oldfield1971), and they had normal or corrected to normal vision.

Fig. 1. Description of assignment of participants into the groups.

Participants were subjected to a structured interview to assess if they could participate in the study. They were asked about their substance abuse history and their current alcohol and tobacco use, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM IV) criteria, as well as neurological or psychiatric disorders (based on the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview). General cognitive ability was assessed using the Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (Raven etal., Reference Raven, Raven and Court1998). The mood status was measured by means of the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Anxiety Inventory, respectively, validated in the Mexican population (Jurado etal., Reference Jurado, Villegas, Méndez, Rodríguez, Loperena and Varela1998), Questionnaires on demographic information, medical history, and current medication status were additionally collected to select volunteers of both groups.

According to previous research (Pope, Gruber, Hudson, Huestis, & Yurgelun-Todd, Reference Pope, Gruber, Hudson, Huestis and Yurgelun-Todd2001), CU group was defined as the individuals who had used cannabis at least 50 times within the 6 months prior to the study and at least once within the last 72 hr. It also included individuals who had used cannabis as the main substance, and not undergoing cannabis or other substance rehabilitation. The comparison group, the NCU, were those who reported never consuming cannabis in their life.

All participants were subjected to a urine drug screen for detecting recent consumption of cannabis, methadone, opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates (2001103 BIO-DRUG 5x1, Grupo Industrial MexLab S.A. de C.V., Guadalajara, Jal, Mexico). NCU participants who were positive for any of the substances were excluded from the experiment, whereas CU participants that tested positive in any substance other than cannabis, were also excluded.

Volunteers were also excluded if they reported: (1) a medical, psychiatric, or neurological condition that might affect cognitive function; (2) a history of any head trauma resulting in loss of consciousness requiring clinical evaluation; (3) current use of any psychoactive medication; (4) a history of DSM-IV dependence disorder or other class of drug abuse (such as hallucinogens, cocaine, stimulants, or opiates); (5) have used any drug, different from tobacco and alcohol, within the last 2 weeks prior to the experimental session; (6) presenting severe symptoms associated with depression and/or anxiety; (7) reporting alcohol consumption within the 24 hr prior to the experimental session; (8) resulting an outlier in the percentage of correct responses (i.e., three or more standard deviations lower or higher than the group average); (9) having more than 10% of no responses in the ANT; and (10) for CU, gave a negative result for cannabis use in the urine drug screen (Figure 1); for NCU, reporting any lifetime experience with cannabis consumption.

Experiments were performed between 10:00 and 18:00 hr to control diurnal effects in cognitive performance (Valdez, Reference Valdez2019). All participants signed a written informed consent prior to the evaluations. The experimental protocol was endorsed by the Research and Ethics Committee at UNAM’s School of Medicine. Subjects received a detailed description of the research basis at the end of the experimental session.

Cannabis Use Measurements

Participants of the CU group were asked about their age at onset, the number of years, and episodes of cannabis use. An episode was defined as when cannabis is used even if the amount of consumption is minimal (e.g., a puff, a touch, or a portion of an edible cannabis product). They are considered as different episodes when there was at least 1 hr of separation (Pope etal., Reference Pope, Gruber, Hudson, Huestis and Yurgelun-Todd2001). Subjects were asked to report the number of episodes in the last month and last week, as well as the number of days they used cannabis in the last month and last week; and how many hours had passed since the last cannabis use (Scott etal., Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur2018). In addition, the number of episodes of cannabis use during their lifetime was estimated, by means of a six-point ordinal scale as follows: 1 = 3–50 times; 2 = 51–100 times; 3 = 101–500 times; 4 = 501–1000 times; 5 = 1001–1500 times; 6 = more than 1500 times. This study included only CU volunteers with a maximum abstinence period of 72 hr as in previous works (Filbey, McQueeny, Kadamangudi, etal., Reference Filbey, McQueeny, Kadamangudi, Bice and Ketcherside2015). As suggested previously, participants were instructed to not alter their habitual cannabis use on the day of testing, in order to prevent any abstinence effect, such as irritability or anxiety, which are manifested mostly on days 0–3 after the last cannabis use (Bonnet & Preuss, Reference Bonnet and Preuss2017; Lee etal., Reference Lee, Vandrey, Mendu, Anizan, Milman, Murray and Huestis2013) and it could impair attention performance (Hanson etal., Reference Hanson, Winward, Schweinsburg, Medina, Brown and Tapert2010). Like previous works, cannabis users who met the criteria for symptoms related to alcohol and/or tobacco dependence were not excluded, because cannabis use is frequently concomitant with the dependence on alcohol or tobacco (Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Agrawal etal., Reference Agrawal, Lynskey, Hinrichs, Richard, Saccone, Krueger and Bierut2011; Barrett etal., Reference Barrett, Darredeau and Pihl2006; Bellis etal., Reference Bellis, Wang, Bergman, Yaxley, Hooper and Huttel2013; Chung etal., Reference Chung, Cornelius, Clark and Martin2018; Hooper etal., Reference Hooper, Woolley and De Bellis2014).

To assess the effect of cannabis dependence on the attention networks, we performed an analysis considering cannabis use dependence. It was defined as a lifetime history of DSM-IV cannabis dependence, (i.e., three or more, out of seven criteria, clustering within 12 months).

The Attention Network Test (ANT)

Participants performed the ANT (Figure 2) after completing a preliminary practice session (24 randomly selected trials), ensuring that all participants understood the instructions and were able to perform the task reliably. Briefly, the ANT (Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz, & Posner, Reference Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz and Posner2002) consists of a series of trials and are as follows: the presence or absence of a cue (100 ms), a “plus sign” as a fixation point (displayed for 400 ms) followed by the target stimulus (i.e., an arrangement of five horizontal arrows displayed for 1700 ms). Participants had to determine whether the central arrow of this arrangement pointed to the left or to the right, by pushing a left button for the left direction with their left hand or a right button for the right direction with their right hand; subjects had up to 1700 ms to answer; and, finally, a fixation point was displayed with a random intertrial interval between 400 ms and 1600 ms (1000 ms on average) to avoid habituation. The central arrow was at a visual angle of 0.3° at a viewing distance of 100 cm. The total visual angle of the central arrow with the five flankers was 1.1° × 1.7° (vertical and horizontal, respectively). Targets were presented 0.55° above or below the fixation “plus sign”. Asterisk cues were warning cues that were shown at the beginning of the task (visual angle of 1.8°).

Fig. 2. Attention Network Test.

Trials started with one of three alerting cue conditions: no-cue (no warning of target arrival); double cue (two asterisks displayed, one above and the other below the fixation point, warning of the upcoming arrival of the target), and spatial cue (an asterisk which was displayed right on the location of the forthcoming target, above or below the fixation point, warning of target’s arrival). Regarding the target, there were two types of trials based on two flanking conditions: a central arrow pointing in the same direction as the flanking arrows (congruent target trial; i.e., →→→→→); or a central arrow pointing in the opposite direction of the flanking arrows (incongruent target trial; i.e., →→←→→). A total of 120 trials were performed; there were 40 trials for each type of cue (non-cue, double cue, and spatial cue) and half of the trials for each type of cue were congruent, whereas the other half, incongruent. Subjects were instructed to respond as fast and as accurately as possible. Time presentations and responses for the ANT were controlled using E-prime v1.2 (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

To perform the statistical analysis, Jamovi v.1.1.9 software was used. To identify the violation of homogeneity and/or nonnormality in the analyses, we visually inspected the model residuals using a residuals versus-fitted values plot and a normal “Q–Q” plot (Crawley, Reference Crawley2012; Zuur etal., Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009). No heterogeneity was detected in either model. In addition, we checked for the presence of influential observations in each model by measuring the Cook’s distance of each observation (values greater than 1 are considered influential; (Cook & Weisberg, Reference Cook and Weisberg1984). Thus, we detected no outliers in the final sample (see Supplementary Figure 1). Statistical analyses are described according to the aims of the study.

Cannabis-Using-Group versus Non-Cannabis Group Comparison

The demographic and descriptive data were analyzed by means of Student’s t test for independent samples (i.e., for continuous variables) or χ2 (i.e., for frequencies) to detect differences between the NCU and CU.

By measuring how mean reaction times (RT) are influenced by cue condition and flanker type (Fan etal., Reference Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz and Posner2002), the ANT provides measures using the raw scores of RT to obtain the scores associated with the alerting system (the mean RT of the non-cue condition minus the mean RT of the double-cue condition; i.e., participants are expecting the appearance of the target stimuli), the orienting system (the RT time of the double-cue condition minus the mean RT of the spatial-cue condition; i.e., participants know where the target stimuli are going to appear, because of the spatial cue) and the executive control system (the mean RT of the incongruent condition minus the mean RT of the congruent trials; i.e., subjects have to solve a conflict). Considering that the general cognitive ability differed between NCU and CU groups (see Table 1), analyses of covariances (ANCOVA) were performed for all dependent variables (i.e., RT, percentage of correct responses, alerting, orienting, and executive control systems) using the general cognitive ability as a covariate. RT and percentages of correct responses were evaluated by a mixed three-way ANCOVA, using the group as independent factor and cue condition (non-cue, double cue, and spatial cue) and flanker type (congruent and incongruent) as repeated measures factors. For alerting, orienting, and executive control scores, a one-way ANCOVA was performed using group (NCU vs. CU) as a factor.

Table 1. Demographic and characteristics of substance use of the participants of this study. It was compared between non-cannabis-using group (NCU) and cannabis-using group (CU) (sixth column); NCU versus Non-cannabis dependence (NCD) users and versus cannabis dependence (CD) users (seventh column); and NCD users versus CD users (eighth column). At the end of the table, it is specified which statistical test was used for each comparison, as well as the type of measure that is reported. Significant differences are signaled in bold

Statistical tests are used.

* Pearson’s χ2 test. It is reported the frequency of cases and percentages in parentheses.

† Student’s t test for two independent samples. It is reported the mean and the standard deviation.

‡ One-way analysis of variance for independent samples. It is reported the mean and the standard error of the mean.

§ Mann–Whitney U test. It is reported the median and the minimum and maximum values.

** The estimated lifetime episodes of cannabis use was done by means of a 6-point ordinal scale: (1 = 3–50 times; 2 = 51–100 times; 3 = 101–500 times; 4 = 501–1000 times; 5 = 1001–1500 times; 6 = more than 1500 times).

Assessment of Cannabis Dependence in the ANT

First, demographic variables were compared between NCU, NCD, and CD groups, through one-way ANOVA for independent groups. Additionally, by mean of Student’s t test for independent samples, cannabis use characteristics were compared, such as the frequency of individuals with tobacco or alcohol dependence, the onset age and years of cannabis use, days, and episodes of cannabis use in the last month and week, and the reported hours from the last use between NCD and CD groups. Mann–Whitney U test was used for compared groups in the estimate of lifetime episodes of cannabis use (because of the ordinal 6-point scale employed), and the number of episodes of cannabis use in the last month (because of the skewness distribution).

To test the second aim of this study, subsequent analyses evaluated the potential effect of cannabis dependence in the attention network systems. For this purpose, the CU group was subdivided as a function of the presence (CD) or absence of cannabis dependence (NCD; according to the DSM-IV criteria), a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for independent samples was used for alerting, orienting, and executive control scores.

For all the analyses, Welch’s correction was used for unequal variances; Greenhouse–Geisser correction (ε) was performed to avoid violation of sphericity. And Bonferroni was used as the post hoc test. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Assessing the Effect of Cannabis and Tobacco and Alcohol Dependence on the Attention Network Systems

One-way ANOVA was performed for the attention network systems that resulted statistically significant in the evaluation of the effect of cannabis dependence.

Characteristics of Cannabis Use and Attention Network Systems

Finally, simple regressions were calculated using the cannabis use variables (i.e., onset age of cannabis use, years of cannabis use, estimate of the number of lifetime episodes of cannabis use, days of cannabis use in the last month and last week, episodes of cannabis use in the last week, reported hours from the last cannabis use) as predictors of the ANT scores. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic and drug use characteristics of both NCU and CU. Groups did not differ significantly in age (p = 0.23), sex (p = 0.14), or years of schooling (p = 0.07). But in the general cognitive ability (i.e., Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (p = 0.01), there were more individuals above average in the CU than in the NCU group. Considering this result, the following statistical analysis includes the category of general cognitive ability as a covariate.

Cannabis-Using-Group versus Non-Cannabis Group

RT and percentage of correct responses between CU and NCU

For RT, after controlling for the effect of the general cognitive ability, there was an effect of the group (F(1, 253) = 11.93, p = 0.0007, ηp 2 = 0.05); the CU group was faster (Mean ± SEM: 592.28 ± 12.22) than the NCU group (627.27 ± 13.38) for answering the ANT. Also, there were the typical main effects of cue condition (F(1.80, 454.36) = 22.92, p < 0.0001, ηp 2 = 0.08, ε = 0.90) and flanker type (F(1, 253) = 193.80, p < 0.0001, ηp 2 = 0.43), independent of group. The non-cue condition (628.58 ± 11.82 ms) was significantly slower than the double-cue condition (602.84 ± 11.82 ms); likewise, it was significantly slower than the spatial cue condition (597.91 ± 11.82 ms). On the other hand, the incongruent trials (644.74 ± 11.82 ms) were significantly slower than the congruent trials (574.81 ± 11.82 ms). Also, there was a significant interaction between cue condition and flanker type (F(1.96, 496.21) = 7.96, p = 0.0004, ηp 2 = 0.03). Post hoc revealed that for all cue conditions, the congruent trials were faster than the incongruent trials, and this effect was slower in the non-cue condition in comparison with double-cue condition, and this relative to spatial condition.

An interaction between group and cue condition was observed (F(1.80, 454.36) = 13.52, p < 0.00001, ηp 2 =0.05, Figure 3a). The effect of cue condition was observed in the NCU group (non-cue>double cue>spatial cue), but not in the CU group (non-cue>double cue=spatial cue); participants from the CU group responded faster than NCU in the non-cue and double-cue conditions, but not in the spatial condition. The difference between the non-cue and the double cue was shorter for the CU group (20.44 ms) than the NCU group (31.04 ms). There were no significant interactions between group and flanker type (p = 0.26), or group by cue condition by flanker type (p = 0.53).

Fig. 3. (a) Mean and SEM for the reaction times depending on cue conditions and group. The healthy control group is depicted in black, and the cannabis use group, in gray. Compared with the NCU, CU exhibited significantly faster reaction times for non-cue and double-cue conditions (a), but not for the spatial cue condition. Significantly lower intergroup reaction times for the non-cue condition were observed in both NCU and CU, compared with double and spatial conditions (b); slower reaction times for the double-cue condition were observed compared to the spatial cue condition but only in the NCU group (c). (b) Mean and SEM for the percentage of correct responses depending on flanker task and group. Congruent differed from. incongruent trials in both groups (a). Lower percentage of correct responses was observed in the CU group compared to NCU only for incongruent trials (b). a, b, and c: p < 0.05.

For the percentage of correct responses, after controlling for the effect of the general cognitive ability, there was no main effect for cue condition (p = 0.15), but a marginal main effect for the group (p = 0.051): CU group had a lower percentage of correct responses (97.70 ± 0.46%) than the NCU group (98.46 + 0.51%). Also, there was a significant main effect for flanker type (F(1, 253) = 19.64, p < 0.00001, ηp 2 = 0.07); the percentage of correct responses was lower for incongruent (97.70 ± 0.46%) than for congruent (99.09 ± 0.46%) trials. A significant interaction was observed for group and flanker type (F(1, 253) = 4.44, p = 0.04, ηp 2 = 0.02). There was a lower percentage of correct responses for incongruent trials than for congruent trials in both NCU and CU groups; no differences between groups were observed for congruent trials but it was for incongruent trials (Figure 3b). No significant interaction was observed for cue condition by flanker type (p = 0.14), and for the group by cue condition by flanker type (p = 0.63).

Attention Networks between NCU and CU

Table 2 shows attention network results for the whole sample, as well as for NCU and CU, after controlling for the effect of the general cognitive ability.

Table 2. Mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) for each of the attention network systems for the whole sample and as a function of cannabis-using group. The last column shows the statistical comparison between non-cannabis using versus cannabis-using group. Significant results are shown in bold

Alerting System

NCU and CU groups differed (F(1, 253) = 7.08, p = 0.008, ηp 2 = 0.03). CU group had a 34.10% lower alerting score than the NCU group (Table 2).

Orienting System

There was a significant difference between groups (F(1, 253) = 9.14, p = 0.003, ηp 2 = 0.03). CU group showed a significantly lower (101.89%) orienting score than the NCU group (Table 2).

Executive System

No differences between groups (p = 0.29) were found.

Assessment of Cannabis Dependence in the ANT

To test cannabis dependence had a different effect on the ANT, we performed a subsequent analysis segregating the CU sample between the cannabis dependence (CD; n = 76; 35 women) and a non-cannabis dependence (NCD; n = 26; 14 women) groups. Both groups CD and NCD were compared versus NCU. Table 1 presents the demographic and the cannabis use data for both types of cannabis users. There were no significant differences among the three groups as to age (p = 0.31), sex (p = 0.31), years of schooling (p = 0.18), or in the Raven’s progressive matrices (p = 0.10).

Alerting System

Significant differences were observed among the three groups (F(2, 253) = 3.36, p = 0.04, ηp 2 = 0.03, Figure 4a). CD group had a 34.69% significantly lower alerting score (20.16 ± 3.55 ms) relative to the NCU group (30.87 ± 2.49 ms), but it did not differ from the NCD group (22.30 ± 6.06). NCU and NCD groups did not differ.

Fig. 4. Mean and SEM for alerting (a) and orienting (b) scores, as a function on NCU, CU, and CD groups. Differences were observed between NCU and CD groups (a) in both alerting and orienting scores. a: p < 0.05.

Orienting System

Differences among groups were detected (F(2, 77.17) = 6.24, p = 0.003, ηp 2 = 0.04). The CD group (−1.19 ± 3.02 ms) showed a significantly (111.61%) less orienting effect than the NCU (10.25 ± 2.12 ms), but it did not differ from NCD (1.64 ± 5.17 ms); NCU did not differ from NCD (Figure 4b).

Executive System

No significant differences were observed among the three groups (p = 0.51).

Cannabis and Tobacco and Alcohol Dependence on the Alerting and Orienting System

To test whether the alerting and orienting system results associated with CD could be modified by tobacco or alcohol dependence, the alerting and the orienting scores were assessed based, on the one hand, by tobacco dependence, and on the other hand, by alcohol dependence. Stratifying the sample, according to cannabis and tobacco dependence, there were five subgroups: NCU, n = 154; CU without cannabis dependence nor tobacco dependence (NCD/NTD), n = 19; CU with cannabis dependence but not tobacco dependence (CD/NTD), n = 57; CU without cannabis dependence but tobacco dependence (NCD/TD), n = 7; and CU with both cannabis and tobacco dependence (CD/TD), n = 19. No significant effect was observed on alerting scores as a function of group (p = 0.10); nonetheless, there was a significant effect on orienting scores (F(4, 251) = 2.67, p = 0.03, ηp 2 = 0.04). Post hoc revealed a 120.88% lower orienting score for CD/NTD group (−2.14 ± 3.50) relative to the NCU group (10.25 ± 2.13; Figure 5a); no other comparison resulted significantly different (p > 0.05).

Fig. 5. Mean, SEM, and the observed scores for the orienting system. (a) Comparison of NCU, NCD/NTD, CD/NTD, NCD/TD, CD/TD groups. Differences were between CD/NTD and NCU groups (a). NCU, non-cannabis using; NCD, Non-cannabis dependence; NTD, non-tobacco dependence; CD, cannabis dependence, TD, tobacco dependence. (b) Comparison of NCU, NCD/NAD, CD/NAD, NCD/AD, CD/AD. Differences were found between CD/AD and NCU (a) and a trend between CD/NAD contrasted to NCU (b). NCU, non-cannabis using; NCD, Non-cannabis dependence; NAD, non-alcohol dependence; CD, cannabis dependence, AD, alcohol dependence. a: p < 0.05; b: p = 0.051.

According to alcohol dependence, there were five subgroups: NCU, n = 154; CU without cannabis dependence nor alcohol dependence (NCD/NAD), n = 19; CU with cannabis dependence but not alcohol dependence (CD/NAD), n = 27; CU without cannabis dependence but with alcohol dependence (NCD/AD), n = 7; and CU with both cannabis and alcohol dependence (CD/AD), n = 49. For the alerting score, no differences among groups were detected (p = 0.09). In contrast, for the orienting score, there were differences among groups (F(4,36.64 = 0.03, p = 0.03, ηp 2 = 0.04). The CD/AD group (−1.57 ± 3.78 ms) significantly (115.32%) reduced their orienting score compared to the NCU group (10.25 ± 2.13 ms; p = 0.02; Figure 5b); and the CD/NAD group (−0.51 ± 5.09) showed a marginal decrease of 104.98% in its orienting score relative to the NCU group (p = 0.051). No other comparison resulted statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Characteristics of cannabis use and the attention network systems

Only the age of onset of cannabis use significantly predicted orienting (β = 0.25, t(101) = 2.56, p = 0.01, R 2 = 0.06) and executive control (β = −0.23, t(101) = −2.37, p = 0.02, R 2 = 0.05) scores. This variable did not significantly predict alerting scores (p = 0.54) (Figure 6). No other characteristic predicted the ANT scores (p > 0.05).

Fig. 6. Regression results for alerting (top), orienting (middle), and executive control (bottom) systems predicted by age of onset of cannabis use. This factor only significantly predicted orienting and executive control systems.

DISCUSSION

This research focused on four goals. First, to thoroughly evaluate the effect of cannabis use on three attention network systems in a large adult sample. Our results showed that the alerting system is enhanced, and the orienting system is diminished in cannabis users (goal 1), particularly, in those who have cannabis dependence (goal 2, Table 2, Figure 4). And this effect seems to be associated with cannabis dependence more than with tobacco or alcohol dependence (goal 3, Figure 5). Among the characteristics of cannabis use (goal 4), only the age of onset of cannabis use significantly predicted the orienting and executive control scores: earlier age of onset predicted worse orienting and executive control systems (Figure 6).

The alerting and orienting systems were susceptible to cannabis use and dependence, but not the executive control system. Alerting is the ability to be responsive to the demands in the environment; it relies on the tonic alertness for maintaining attention (Posner, Reference Posner2008). The difference between non-cue and double-cue conditions was shorter for the CD group compared to the NCU group shortening the alerting score. While no difference was observed between groups in the percentage of correct responses, it seems that the CD group was more efficient in using the cue to predict the target appearance compared to when there was no cue. Probably, CD subjects increase their alertness to attending active engagement with the task. Our results contrast with previous studies that have not detected changes in tonic alertness (Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, Reference Gouzoulis-Mayfrank2000). This could be explained by differences between sample sizes and the type of population studied.

On the other hand, orienting is the ability to correctly select the target information from the sensory input, and this was lowered by cannabis dependence. The orienting of attention guided by a cue helps the individual to enhance processing of the relevant information (Posner, Reference Posner2014), and is part of the top-down control of attention (Corbetta & Shulman, Reference Corbetta and Shulman2002). Our results revealed a deleterious ability in CD individuals to engage directing attention to the target stimulus, affecting their top-down control. Interestingly, the orienting system can be facilitated by cannabis cues in cannabis users (i.e., attentional bias toward cannabis cues, an automatic selective attentional orientation toward stimuli associated with drug use; (O’Neill etal., Reference O’Neill, Bachi and Bhattacharyya2020; Vujanovic etal., Reference Vujanovic, Wardle, Liu, Dias and Lane2016). Our results differed from others which did not detect any effect of cannabis use in orienting systems (Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013). Also, the small and type of population samples can be related to differences between studies.

Some studies have reported a detriment in the executive control system in adolescent cannabis users (Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010, Cengel etal., Reference Cengel, Bozkurt, Evren, Umut, Keskinkilic and Agachanli2018), but not others (Rangel-Pacheco etal., Reference Rangel-Pacheco, Lew, Schantell, Frenzel, Eastman, Wiesman and Wilson2020; Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013), as ours. It could be because our participants had a later cannabis use onset age, 17 years old on average, than in previous studies (14 years old on average); therefore, cannabis use onset was in a different phase of brain development (Gogtay & Thompson, Reference Gogtay and Thompson2010); in fact, it is well known that CB1R expression increases as a function of age, increasing after adolescence (Amancio-Belmont etal., Reference Amancio-Belmont, Romano-López, Ruiz-Contreras, Méndez-Díaz and Prospéro-García2017; Long etal., Reference Long, Lind, Webster and Weickert2012). These changes have been observed in the prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in attention (Jha etal., Reference Jha, Fabian and Aguirre2004; Paneri & Gregoriou, Reference Paneri and Gregoriou2017). Thus, the use of cannabis at earlier ages could modify the endocannabinoid homeostasis, impinging brain development. Supporting this idea, it has been shown that the cortical architecture is modified in those individuals with earlier cannabis use onset (<16 years old) compared to those with later onset (Filbey, McQueeny, DeWitt, etal., Reference Filbey, McQueeny, DeWitt and Mishra2015). According to these results, there is evidence of functional alteration in attention. (Vilar-López etal., Reference Vilar-López, Takagi, Lubman, Cotton, Bora, Verdejo-García and Yücel2013) reported that an earlier age of regular cannabis use was associated with poorer orienting. We found similar results (Figure 6): the age of onset of cannabis use predicted the orienting score: earlier the age of onset of cannabis use, worse their orienting ability; furthermore, this variable also predicted the executive control system: as earlier the age of onset of cannabis use, worse their ability to resolve the conflict.

The comorbidity of cannabis with other drugs has been made the effect of cannabis use difficult to understand. Several studies have suggested that cannabis can have a potential protective effect against the consumption or dependence on other substances (Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, Reference Gouzoulis-Mayfrank2000; Jacobus etal., Reference Jacobus, McQueeny, Bava, Schweinsburg, Frank, Yang and Tapert2009; Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, etal., Reference Medina, Schweinsburg, Cohen-Zion, Nagel and Tapert2007; Nixon, Reference Nixon1999). Thus, we also evaluated whether tobacco or alcohol dependence could modify the results in the alerting and the orienting system we observed. Taking our results cautiously given the small subsample sizes, differences in the orienting, but not in the alerting system, between the NCU and the CD/NTD and between NCU and CD/NAD and CD/AD, one can interpret that cannabis dependence is deteriorating the orienting system, more than alcohol dependence. To test this hypothesis, a design of 2×2 independent groups (absence vs. presence of cannabis dependence; and absence vs. presence of alcohol dependence) is necessary. Our sample did not give us the possibility to test this hypothesis. However, previous literature has shown that alcohol dependence does not impair the orienting system (Lannoy etal., Reference Lannoy, Heeren, Moyaerts, Bruneau, Evrard, Billieux and Maurage2017; Maurage etal., Reference Maurage, de Timary, Billieux, Collignon and Heeren2014).

Instead of the DSM-V to detect users with alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis dependence, we used the DSM IV-TR, because it was not available when we started our research. While the DSM-V could increase the prevalence of diagnoses due to substance use disorder, the DSM-IV-TR could underestimate them. However, studies have found that concordance between the DSM-IV-TR and the DSM-V is above 99% (Kelly etal., Reference Kelly, Gryczynski, Mitchell, Kirk, O’Grady and Schwartz2014). Thus, our results can be conciliated with works using DSM-V.

It is worth mentioning that we compared, between NCU and CU, those variables that are known to interfere with attention performance, such as age, years of schooling, or general cognitive ability to clearly detect differences caused by drugs (Table 1). Interestingly, in our sample, there was a higher frequency of CU individuals with superior general cognitive ability than in NCU participants. We controlled this variable using it as a covariate in the comparison between the NCU and CU groups. Thus, even controlling for this covariate, the effect associated with cannabis dependence remains. Two facts make us have confidence in our results, our participants were rigorously recruited and our sample is larger than in most studies that explore cannabis use and attention tasks (e.g., Abdullaev etal., Reference Abdullaev, Posner, Nunnally and Dishion2010; Bocker etal., Reference Bocker, Gerritsen, Hunault, Kruidenier, Mensinga and Kenemans2010; Solowij etal., Reference Solowij, Michie and Fox1991; Solowij etal., Reference Solowij, Stephens, Roffman, Kadden, Miller, Christiansen and Vendetti2002), which resulted in an advantage because it allowed us to stratify our CU sample and to make a thorough behavioral evaluation of the characteristics of cannabis users in our country.

Previous research has suggested that sex and substance use disorders interact. Sex moderates the neural impact of the use of cannabis and alcohol, and it has been suggested to consider this variable in research (Medina etal., Reference Medina, McQueeny, Nagel, Hanson, Schweinsburg and Tapert2008). We performed the same analyses described previously adding the sex factor to detect its potential contribution to the effect of cannabis use. However, no sex by group interaction was found in any of the attention systems or in the RT and percentage of correct responses results (p > 0.05, data are not shown).

Although this study has strengths, a number of limitations should be addressed. While every possible effort was made to carefully measure recent substance use, we were not able to account for cannabis potency, quantity, and dosing ingested in each episode, neither quality nor quantity of its main components. These limitations could be resolved in future research using other more precise methods that would require less stigma from the present environment toward the substance. Another limitation of our study was the lack of brain response measures while participants perform the ANT. It would be important, because no behavioral differences between control subjects and cannabis users have been reported, but brain activity is modified in the later subjects, suggesting a compensation effect (e.g., Chang etal., Reference Chang, Yakupov, Cloak and Ernst2006; Rangel-Pacheco etal., Reference Rangel-Pacheco, Lew, Schantell, Frenzel, Eastman, Wiesman and Wilson2020). Thus, it is possible that the attention network systems tested here are accompanied by altered brain activity or connectivity. On the other hand, although we considered variables that contribute to attention efficiency, further research could explore the effect of having fewer years of schooling on attention network systems. In our study, our subjects had 15 years of schooling on average, which might protect subjects from a wider effect of cannabis use. Also, it will be important to further research the potential changes in the attention systems associated with aging.

Another limitation of our study was the small sample sizes resulting when the sample was stratified to evaluate tobacco and alcohol dependence effects and the impossibility to test specific hypotheses related to dependence on other substances. Finally, as a first attempt of researching patterns of use episodes, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, the patterns of cannabis use and alcohol use could not be clearly ascertained. Using a longitudinal approach would allow us to obtain more precise substance use information in subsequent research.

In conclusion, our results indicated that cannabis dependence enhances alerting and reduces the selective attention given by the orienting system. Additionally, age of onset of cannabis use predicted the detriment in the orienting and executive control systems.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617721000369.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Edith Monroy for her careful editing of the English language manuscript. We also thank Dr. Raúl Aguilar-Roblero for the discussion of the data of this research. We also appreciate Dr. Isaac G. Santoyo for his invaluable advice in the statistical analyses. We thank Iván Guillermo for helping with data acquisition.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work is Ivett Ortega-Mora’s Doctoral Dissertation in the Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas of UNAM and received fellowship number 586812, No. CVU 586812 from CONACYT. This work was supported by Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico-Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (DGAPA-PAPIIT-UNAM), Grant numbers: IN217918, IN218620, IA205218 to AERC, OPG, and MMD, respectively.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

All participants collaborated in this study voluntarily. This study was conducted according with the Helsinki declaration. The experimental protocol was endorsed by the Research and Ethics Committee at UNAM’s School of Medicine. All data were anonymized.