Introduction

To manage daily life without visual information, blind people heavily rely on their memory and maintain equal or superior performance in some memory processes such as serial memory (Amedi, Raz, Pianka, Malach, & Zohary, Reference Amedi, Raz, Pianka, Malach and Zohary2003; Raz, Amedi, & Zohary, Reference Raz, Amedi and Zohary2005; Raz, Striem, Pundak, Orlov, & Zohary, Reference Raz, Striem, Pundak, Orlov and Zohary2007; Roder & Rosler, Reference Roder and Rosler2003; Roder, Rosler, & Neville, Reference Roder, Rosler and Neville2001). It is unclear, however, whether the equal or superior performance in the blind despite lack of visual information is a result of better efficiency of the same memory network as the sighted or from engagement of additional or alternative memory circuits.

Previous studies regarding of reorganization in the occipital cortex of the congentially (early) blind have suggested that the latter possibility is likely to be a more plausible explanation. Functional reorganization in the unemployed occipital cortex of blind individuals has been found by various studies using Braille reading (Sadato et al., Reference Sadato, Pascual-Leone, Grafman, Ibanez, Deiber, Dold and Hallett1996, Reference Sadato, Pascual-Leone, Grafman, Deiber, Ibanez and Hallett1998), auditory localization (Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Horwitz, Aziz-Sultan, Tian, Wessinger, Cohen and Rauschecker2000), speech processing (Roder, Stock, Bien, Neville, & Rosler, Reference Roder, Stock, Bien, Neville and Rosler2002), mental imagery (Lambert, Sampaio, Mauss, & Scheiber, Reference Lambert, Sampaio, Mauss and Scheiber2004), and semantic auditory language processing (Burton, Diamond, & McDermott, Reference Burton, Diamond and McDermott2003). Therefore, there is a possibility that the occipital cortex may act as an additional memory circuit in the blind. Indeed, functional neuroimaging in the blind has demonstrated involvement of the occipital cortex during the memory processing for short-term verbal memory (Amedi et al., Reference Amedi, Raz, Pianka, Malach and Zohary2003) and episodic retrieval (Raz et al., Reference Raz, Amedi and Zohary2005).

In contrast to short-term memory or episodic memory, working memory requires executive and attention control, as it not only temporarily stores but also manipulates information (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley1998, Reference Baddeley2003). Working memory activates a network that mainly includes the lateral part of the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe in sighted individuals, although cortical involvement may vary depending on the material and the processing requirements of the task (for reviews, Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000). At the same time, working memory induces suppression in the midline regions, such as the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and medial prefrontal cortex, depending on the memory load (Fransson, Reference Fransson2006; Fransson & Marrelec, Reference Fransson and Marrelec2008; Hampson, Driesen, Skudlarski, Gore, & Constable, Reference Hampson, Driesen, Skudlarski, Gore and Constable2006; Salvador et al., Reference Salvador, Martinez, Pomarol-Clotet, Gomar, Vila, Sarro and Bullmore2008; Sambataro et al., 2010; Scheeringa et al., Reference Scheeringa, Petersson, Oostenveld, Norris, Hagoort and Bastiaansen2009). These areas are often called the “default mode network (DMN)” (Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman, & Raichle, Reference Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman and Raichle2001; Raichle et al., Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001) and are known to be activated during a baseline resting state but deactivated during a goal-directed attention-demanding task. Since working memory demands active attention (unlike a passive storage system), a high memory-load task may require reallocation of attention from other brain activities (McEvoy, Smith, & Gevins, Reference McEvoy, Smith and Gevins1998). Therefore, working memory may recruit at least two cooperative processes, including a lateral activation circuit and a medial deactivation circuit.

In the present study, we investigated how these normal brain networks for working memory are manifested in the early blind. First, we aimed to elucidate the role of the occipital cortex in working memory in the early blind. Since the occipital cortex of the blind has been associated with higher level cognitive processes, such as mental imagery and language (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Diamond and McDermott2003; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Sampaio, Mauss and Scheiber2004), we hypothesized that the central executive aspects of working memory, rather than its phonological and visuospatial components would affect occipital lobe activity. Second, since the blind may be more exposed to self-referential thoughts than the sighted and may require attention reallocation due to the visual deprivation, we hypothesized that the blind would show altered DMN for working memory. Third, we further hypothesized that the blind would demonstrate modification in their network connectivity among the occipital cortex, DMN, and other working memory components such as the frontal and parietal cortices.

To address these issues, we evaluated both task-driven activation of the occipital cortex and task-driven deactivation of the DMN circuits during 2-back working memory tasks with 3 different stimulus modalities such as auditory verbal, non-verbal, and spatial. We also examined the effective connectivity between the working memory networks to investigate the connectivity alteration in the occipital cortex and DMN with other working memory components.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

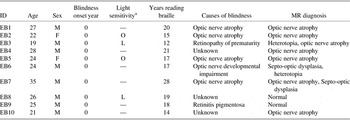

Ten early blind subjects (8 male, 2 female) and 10 sighted subjects (8 male, 2 female) participated in this study. The mean age and education years were 25.1 years (SD = 4.4) and 14.5 years (SD = 1.8) for the blind group, and 25.3 years (SD = 2.8) and 14.8 years (SD = 2.3) for the sighted group; both of them were not significantly different between the two groups. All subjects were right handed. The cause of blindness in these subjects was retinal pathology. None could navigate without aid. All blind subjects had been reading Braille since they were 7 years old. No subject had a history of alcohol/substance abuse or neurological problems except for visual sensory deprivation. All subjects gave written informed consent after hearing detailed explanation about the study. The study was conducted under the guidelines for the study of human subjects established by the Institutional Review Board. Table 1 summarizes information on the blind subjects.

Table 1 Demographic information of the blind subjects

Note. EB = Early blind.

aLight sensitivity: O = existence of object; L = existence of light; — = no light sensitivity.

Behavioral Tasks

We used 2-back tasks as experiment tasks and 0-back tasks as control tasks with three different types of auditory stimuli such as words, pitches, and sound locations, which were considered to reflect verbal, non-verbal and spatial working memory, respectively. For 0-back tasks, subjects were instructed to respond every time a target stimulus was presented. For 2-back tasks, subjects were instructed to respond whenever a pre-indicated stimulus that had been presented was presented again before one intervening stimulus. The stimuli were three Korean nouns (socks, pencil, and plate) in a word n-back task, three sinusoidal tones (620, 730, and 800 Hz) in a pitch n-back task, and three different locations of a 620 Hz pure tone (left, middle, and right) in a sound-location n-back task. Because only three items were used in the sound-location task for the blind, the same number of stimuli was also used in the word and pitch tasks to control the number of stimuli across stimulus types. In the practice session before the functional scanning, all subjects were tested to confirm that they could discriminate the stimuli and perform the tasks.

The block-designed experiment was composed of three runs, once for each stimulus condition. A sequence of blocks for word condition was word 0-back/word 2-back/word 0-back/word 2-back/word 0-back/word 2-back. The same block sequence was also used for pitch and location conditions. The order of the stimulus conditions was counterbalanced across subjects. Ten stimuli were presented for 25 s in a 0-back task block, whereas 14 stimuli were presented for 35 s in a 2-back task block. Each block began with instructions for the following task.

Sighted subjects were instructed to close their eyes while performing the tasks. Stimuli were presented using E-prime of the Eloquence stimulus system (Invivo, USA), and each response was received using an MR-compatible mouse.

Image Acquisition

Brain activity was measured using a Philips 3T MRI system (Achieva; Philips Medical System, Best, The Netherlands) with T2* weighted single shot echo planar imaging (EPI). For each task, fMR images with four dummy scans were scanned axially with the following parameters: echo time (TE) 35 ms, repetition time (TR) 2,500 ms, flip angle 90°, slice thickness 3.5 mm, slice numbers 36, scan image matrix 80 × 80, field of view 220 mm, and voxel unit 2.75 × 2.75 × 3 mm. We also obtained a high-resolution T1-weighted MRI volume data set for each subject using a three-dimensional T1-TFE sequence configured with the following acquisition parameters: axial acquisition with a 224 × 224 matrix, field of view 220 mm, voxel unit 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.2 mm, TE 4.6 ms, TR 9.6 ms, flip angle 8°, slice gap 0 mm.

Image Preprocessing and Statistical Analysis

Data were processed using SPM8 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, version 8, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). After correcting slice acquisition time differences acquired in the interleaved sequence, head movement effects were corrected by realigning the images. After slice timing and realignment, functional images were coregistered to the T1-weighted image for each subject, and then spatially normalized using nonlinear transformation functions obtained by registering individual T1-weighted images to a standard template. The spatially normalized functional data were smoothed with an 8 mm full-width-at-half-maximum Gaussian filter.

Significant differences in regional activity between the 2-back and 0-back tasks, in both the blind and sighted subjects, were estimated using a generalized linear model at every voxel. Group-level activation, within groups and between groups, was compared using a random effect model for the effect of interest. Statistical activation and deactivation for each group during the 2-back versus 0-back tasks were estimated using one-sample t tests and differences between the two groups were estimated using two-sample t tests. The results were identified at the significance level of a minimum of 50 clustering voxels with the threshold of family-wise error (FWE) corrected p < .05. We also analyzed stimulus-specific activations and deactivations during working memory tasks using one-sample t tests for each group and two-sample t tests to see group difference. To consider small data size in the analysis of each task with different stimulus, we used rather a loose criterion of the significance, a minimum of 20 neighboring voxels with the threshold of uncorrected p < .001. Furthermore, percent signal changes were calculated in the coordinates that were selected in the characteristic regions obtained from the group comparison, and were compared between the two groups.

Group Independent Component Analysis and Granger Causality Test

We tested the effective connectivity between the working memory networks using Granger causality test (Granger, Reference Granger1969), which was used to identify a causal relationship between brain regions using fMRI (Bressler & Seth, Reference Bressler and Seth2010; Roebroeck, Formisano, & Goebel, Reference Roebroeck, Formisano and Goebel2005).

Since activated brain regions would include time series other than working memory components, we tested Granger causality between weight time series of independent components for working memory instead of fMRI time series at the activated brain regions. Independent components for working memory were extracted by applying a data-driven group independent component analysis (ICA) to fMRI time series (Calhoun, Adali, Pearlson, & Pekar, Reference Calhoun, Adali, Pearlson and Pekar2001).

As a preprocessing step, we applied a two-level principal component analysis (20 principal components in the first individual level and 30 principal components in the second group level, respectively) to reduce redundancy in the temporal domain. Thus, fMRI data for 10 subjects for each group, that is, 78 total scan time points × 3 stimuli types × 10 subjects, were reduced to 30 principal components with a total voxel number within gray matter, to which we applied ICA based on the Infomax algorithm (Bell & Sejnowski, Reference Bell and Sejnowski1995).

Among 30 independent components of each group, we chose four working memory components: the left and the right fronto-parietal components, DMN cored at the PCC and occipital component. For individuals, we estimated weight time series of these four working memory components using a back-reconstruction procedure. Since we are interested in the modality independent relationship among working memory components and since reliable Granger causality estimation requires sufficient time points, we concatenated weight time series across subjects and stimulus types.

Then, we applied Granger causality analysis among four concatenated weight time series corresponding to working memory components. In detail, for two different weight time series, x(t) and y(t), for image scan time t, Granger causality can be obtained using two multivariate autoregressive models as follows:

![\[--><$$>\eqalign{ x(t)\, = & \,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{i\, = \,1}^p {{{A}_x}(i)x(t\,{\rm{ - }}\,i)} \, + \,{{e}_1}(t),\;\;{\rm var}({{e}_1}(t))\, = \,{{\rm \rSigma }_1} \cr x(t)\, = & \,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{i\, = \,1}^p {{{A}_x}(i)x(t\,{\rm{ - }}\, i)} \, + \,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{i\, = \,1}^p {{{A}_y}(i)y(t\,{\rm{ - }}\,i)} \cr & \, + \,{{e}_2}(t),\;\;{\rm var}({{e}_2}(t))\, = \,{{\rSigma }_2} <$$><!--\]](https://static.cambridge.org/binary/version/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:binary:20160901070446819-0922:S1355617711000051_eqnU1.gif?pub-status=live)

Here, p and A represent a maximum number of lagged observations and regression coefficients, respectively. Granger causality from y(t) to x(t) is defined as

If the current x is better modeled by the past x and y than past x alone, Σ2 becomes less than Σ1, and we can say that y(t) Granger-causes x(t).

To test the existence of Granger causality among working memory components within each group, we used the first order (p = 1) autoregressive model and applied F test. The significance level for Granger causality was set as p = .004 (0.05/12) after Bonferroni correction of multiple testing (n = 12).

Results

Behavioral Results

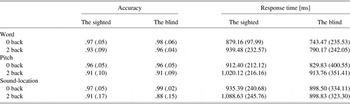

The accuracy and response time were analyzed using a 3 (stimuli; words/pitches/sound-locations) × 2 (task; 0-back/2-back) × 2 (group; blind/sighted) repeated measures analysis of variance using SPSS v.18 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL) (Table 2). Main effects for task were significant for accuracy (F(1,18) = 10.61, p = .004) which was significantly lower in the 2-back condition (0.915, SD = 0.20) than in the 0-back condition (0.971, SD = 0.009). The accuracy did not significantly differ with respect to group (p = .853), stimulus (p = .185), stimulus × group (p = .559), task × group (p = .816), stimulus × task (p = .190), and group × stimulus × task (p = .289).

Table 2 The accuracy and response time of the sighted and blind subjects

Note. Data given as mean (standard deviation).

Main effects of task and stimulus were significant for response time (Ftask(1,18) = 9.16, p = .007; Fstimuli(1.744,31.388) = 4.75, p = .019). The response time was significantly longer in the 2-back condition (941.83 ms, SD = 55.66) than in the 0-back condition (816.54 ms, SD = 54.69). The response times were 838.07 ms (SD = 43.77), 919.03 ms (SD = 65.81), and 955.46 ms (SD = 62.80) for the word, pitch, and sound-location tasks. The response time showed no significant main effects with respect to group (p = .291), and no interactive effects with respect to stimulus × group (p = .797), task × group (p = .220), stimulus × task (p = .588), or stimulus × task × group (p = .203).

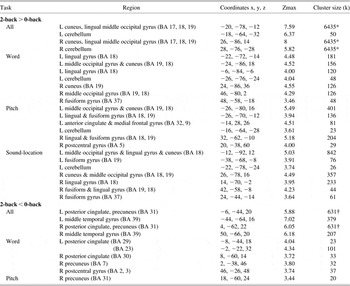

Working Memory-related BOLD Changes in the Sighted

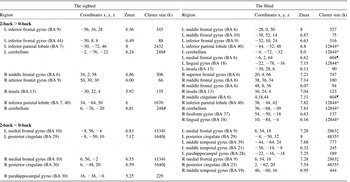

Sighted subjects showed bilateral activation in the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe and cerebellum in the 2-back versus 0-back task comparison regardless of stimulus types (Table 3). More specific information for the detailed regions in the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe was provided in Tables 4–6. As indicated as “A” in Figure 1, for the word and pitch 2-back tasks, the BOLD signal increased in the middle and inferior frontal cortex, corresponding to Broca's area (Brodmann area (BA) 44, 45). In contrast to the word and pitch 2-back tasks, the sound-location 2-back task did not specifically involve this inferior frontal cortex (Table 6).

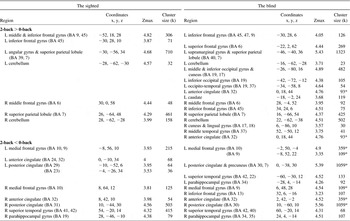

Table 3 Activation and deactivation areas during the working memory in the sighted and in the blind

Note. Family wise error (FWE) corrected p < .05, cluster size ≥ 50; BA = Brodmann area; Coordinates = Montreal Neurological Institute coordinate; Zmax = Z maximum within a cluster; L = left; R = right; k = cluster voxel numbers.

*, †, ‡, §, ||, ¶, indicate cluster sizes of a common cluster but separated into multiple regions: half of total cluster size.

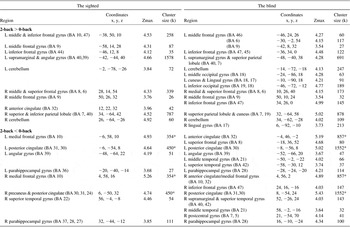

Table 4 Activation and deactivation areas during the word working memory in the sighted and in the blind

Note. p < .001 uncorrected (Z > 3.37), cluster size ≥ 20; BA = Brodmann area; Coordinates = Montreal Neurological Institute coordinate; Zmax = Z maximum within a cluster; L = left; R = right; k = cluster voxel numbers. An asterisk indicates manually segregated cluster size due to a cluster covering both hemispheres: half of total cluster size.

Table 5 Activation and deactivation areas during the pitch working memory in the sighted and in the blind

Note. p < .001 uncorrected (Z > 3.37), cluster size ≥ 20; BA = Brodmann area; Coordinates = Montreal Neurological Institute coordinate; Zmax = Z maximum within a cluster; L = left; R = right; k = cluster voxel numbers. An asterisk indicates manually segregated cluster size due to a cluster covering both hemispheres: half of total cluster size.

Table 6 Activation and deactivation areas during the sound-location working memory in the sighted and in the blind

Note. p < .001 uncorrected (Z > 3.37), cluster size ≥ 20; BA = Brodmann area; MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute coordinate; Zmax = Z maximum within a cluster; L = left; R = Right; k = cluster voxel numbers. An asterisk indicates manually segregated cluster size due to a cluster covering both hemispheres: half of total cluster size.

Fig. 1 A three-dimensional presentation of the areas activated and deactivated during working memory. The first and second columns show the maps of the 2-back minus 0-back tasks of the sighted and the early blind subjects, presenting activations in red to yellow and deactivations in blue to green. The difference of 2-back minus 0-back tasks between the blind and the sighed are displayed in the third column; red to yellow colors indicate increased activation while blue to green colors indicate decreased activation in the early blind compared to the sighted control group. For ALL (word+tone+location-threshold), clusters with a family-wise error corrected p < .05 and cluster size (voxel number) > 50 were displayed in the first row. For word, pitch, sound-location tasks (second to fourth rows), clusters with a threshold p < .005 and cluster size (voxel number) > 50 were displayed. PL = parietal lobe; PCC = posterior cingulate cortex; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; PFC = prefrontal cortex; OC = occipital cortex.

In the sighted, BOLD deactivations were found more in the medial part of the brain such as the medial prefrontal cortex and/or ACC, PCC and precuneus. In addition, deactivation was also detected in the auditory cortex of the right superior temporal gyrus, especially for the pitch 2-back task (see “B” in Figure 1). The sound-location 2-back task evoked additional deactivation in the cuneus (see “C” in Figure 1) which was not involved in the other 2-back tasks.

Working Memory-related BOLD Changes in the Blind

As shown in Tables 3–6, blind subjects showed activations in the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe and cerebellum, which was similar to sighted subjects. Unlike the sighted, blind subjects showed additional activations in the occipital regions. Group comparison showed a significant difference in activation in the occipital lobe for all tasks (Table 7).

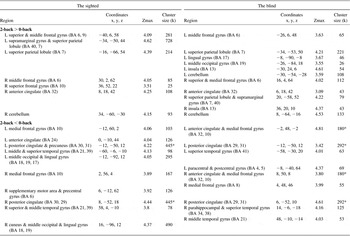

Table 7 Difference in activation and deactivation between the blind and sighted

Note. For All (word + pitch + sound-location), family wise error (FWE) corrected p < .05, cluster size ≥ 50. For word, pitch, and sound-location, p < .001 uncorrected (Z > 3.37), cluster size ≥ 20; BA = Brodmann area; Coordinates = Montreal Neurological Institute coordinate; Zmax = Z maximum within a cluster; L = left; R = right; k = cluster voxel numbers.

*,† indicate three and two regions compose each cluster (sizes, 6435 and 631).

Compared to the sighted, blind subjects showed greater degree of deactivation in the medial part of the brain (Tables 3–6), especially in the PCC during the word processing, as indicated as “D” in Figure 1. Group difference in deactivation in the PCC/Precuneus during the 2-back task existed markedly in the word task and weakly in the pitch task, but not in the sound-location task.

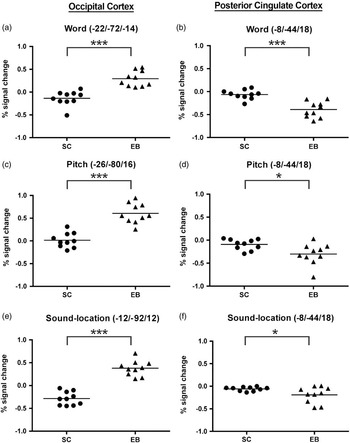

Because the occipital cortex and PCC were found to show the most characteristic differences in the group comparison, we counted percentage signal changes in these regions. As shown in Figure 2, the blind group showed higher signal change in the occipital cortex (BA 18) and decreased signal change in the PCC (BA 29). There was no significant correlation between signal changes in these areas (p > .05).

Fig. 2 Percentage signal change in 2-back versus 0-back tasks at the occipital cortex and posterior cingulate cortex in the sighted (SC) and the early blind (EB). Coordinates in the graphs correspond to peaks relevant to the occipital cortex (BA18) (a, c, and e) for all tasks and to the posterior cingulate cortex (b, d, and f) for the word task in Table 5, which had significant group-difference. Percentage signal changes were calculated at voxels within 3 mm distance from the peak location. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Effective Connectivity Between Activated Regions

Figure 3 explains the result of Granger causality among working memory components in sighted and blind subjects. In the sighted subjects, Granger causality was reciprocally detected between the left and right working memory components. Granger causality from the DMN to both left and right working memory components was also significant in the sighted (Figure 3a). There was no significant connectivity from or to the occipital component during the task.

Fig. 3 Granger causality among working memory components. Granger causality among working memory components are displayed for the sighted (a) and for the early blind (b). WM = white matter; LH = left hemisphere; RH = right hemisphere; DMN = default mode network.

In blind subjects, there was reciprocal Granger causality between the DMN and the left working memory component, between the DMN and the right working memory component, and between the occipital component and left working memory component (Figure 3b). Granger causality from the right working memory component to the left working memory component was also detected.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the occipital cortex of the early blind was involved in a modality independent, core process of working memory by evaluating brain activities during working memory tasks with three different stimulus types. Furthermore, we observed that the alteration in the early blind was not only found in the local activities of the occipital cortex and DMN, but also in their network connectivity with other working memory components.

We found no significant performance difference between groups for all tasks. It may be attributed to the relatively easy task comprised of only three stimulus items in all modalities. To test whether the blind have superior skills in working memory or not, more difficult 3-back tasks with many stimulus items may be needed. Therefore, the current study does not clarify whether altered networks in the blind were needed for the excellence of auditory working memory, or whether additional circuits were recruited for auditory working memory even with a relatively low-level load to achieve normal performance in the early blind.

Working Memory Related Activation Networks in the Sighted

Our findings in the sighted demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe and cerebellum were commonly involved in working memory processing regardless of stimulus type. These findings are consistent with previous working memory studies which have shown that n-back working memory recruits multiple brain regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus (Smith & Jonides, Reference Smith and Jonides1997; Smith, Jonides, & Koeppe, Reference Smith, Jonides and Koeppe1996), parietal lobe (Braver et al., Reference Braver, Cohen, Nystrom, Jonides, Smith and Noll1997; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Perlstein, Braver, Nystrom, Noll, Jonides and Smith1997), and cerebellum (Desmond, Chen, & Shieh, Reference Desmond, Chen and Shieh2005). In particular, our finding of simultaneous involvement of the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe is similar those in previous verbal n-back studies (Braver et al., Reference Braver, Cohen, Nystrom, Jonides, Smith and Noll1997; Nixon, Lazarova, Hodinott-Hill, Gough, & Passingham, Reference Nixon, Lazarova, Hodinott-Hill, Gough and Passingham2004) and an auditory localization task (Martinkauppi, Rama, Aronen, Korvenoja, & Carlson, Reference Martinkauppi, Rama, Aronen, Korvenoja and Carlson2000).

A difference in working memory-related activations among the stimulus types was found only in the sighted, especially in the inferior frontal gyrus; activations were observed in the word and pitch 2-back tasks, but not in the sound-location 2-back task. This indicates that word and pitch working memories use a common phonological loop, as Baddeley proposed in his working memory model (Baddeley, Reference Baddeley2003; Baddeley & Hitch, Reference Baddeley, Hitch and Bower1974). Specifically, information maintenance by an articulate rehearsal process of the left dominant inferior frontal gyrus may contribute to both word and pitch 2-back memories, but not to sound-location 2-back memory in the sighted subjects. For the sound-location task, the sighted subjects might adopt more diverse strategies than word and pitch tasks. Although we could not exclude the possibility that some subjects used a verbal strategy even in the sound-location tasks (e.g., verbally labeling stimuli as left, right, and center), such strategic heterogeneity for the sound-location maintenance in the sighted people might lead to a decreased group-level statistical power in the left inferior frontal gyrus.

Working Memory Related Deactivation Networks in the Sighted

In the sighted people, the medial prefrontal cortex, PCC and precuneus were commonly deactivated during the 2-back tasks regardless of stimulus modalities. Like prefrontal and parietal activations, deactivation of the above-mentioned areas may also be related to high memory load during the 2-back task that requires a reallocation of attention from other brain activities (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Smith and Gevins1998). In fact, memory load-dependent deactivation during working memory in the sighted has been documented in many previous studies (Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Bertolino, Scarabino, Latorre, Blasi, Popolizio and Di Salle2006; Fransson, Reference Fransson2006; Fransson & Marrelec, Reference Fransson and Marrelec2008; Hampson et al., Reference Hampson, Driesen, Skudlarski, Gore and Constable2006; Salvador et al., Reference Salvador, Martinez, Pomarol-Clotet, Gomar, Vila, Sarro and Bullmore2008; Scheeringa et al., Reference Scheeringa, Petersson, Oostenveld, Norris, Hagoort and Bastiaansen2009). The main regions deactivated with increasing task load were the PCC/precuneus and ACC, as predicted by the model of the DMN (Gusnard et al., Reference Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman and Raichle2001; Raichle et al., Reference Raichle, MacLeod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001). Deactivation in the DMN regions seems to be intensified as the task increases the mental load and thus, demands more task-relevant attention (McKiernan, Kaufman, Kucera-Thompson, & Binder, Reference McKiernan, Kaufman, Kucera-Thompson and Binder2003; Singh & Fawcett, Reference Singh and Fawcett2008). Therefore, our results of deactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex, PCC and precuneus for all stimulus types are consistent with previous reports on load-dependent deactivation of the DMN.

Working Memory-Dependent Activation Networks in the Blind

The working memory-related regions in the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe and cerebellum were observed to be similar between the sighted and the blind. The biggest difference between groups was found in the occipital cortex. So far, several previous studies have shown involvements of the blind's occipital cortex in auditory processing such as auditory stimulus discrimination (Kujala et al., Reference Kujala, Alho, Kekoni, Hamalainen, Reinikainen, Salonen and Näätänen1995), auditory localization (Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Horwitz, Aziz-Sultan, Tian, Wessinger, Cohen and Rauschecker2000), and speech processing (Roder et al., Reference Roder, Stock, Bien, Neville and Rosler2002). The occipital cortex of the blind was also activated during mental imagery (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Sampaio, Mauss and Scheiber2004), semantic auditory language processing (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Diamond and McDermott2003), verbal memory (Amedi et al., Reference Amedi, Raz, Pianka, Malach and Zohary2003), and episodic retrieval (Raz et al., Reference Raz, Amedi and Zohary2005).

In the present study, we also observed increased occipital activation during working memory tasks regardless of stimulus types. These results support our hypothesis of the occipital involvement in modality independent, core working memory processes in the early blind. This hypothesis is supported by a transcranial magnetic stimulation study, which showed that the blind's occipital cortex was involved in high level verbal processing rather than phonological or articulatory processing during a verb-generation task (Amedi, Floel, Knecht, Zohary, & Cohen, Reference Amedi, Floel, Knecht, Zohary and Cohen2004). Leclerc, Segalowitz, Desjardins, Lassonde, and Lepore (Reference Leclerc, Segalowitz, Desjardins, Lassonde and Lepore2005) also noted that the occipital cortex of the blind was integrated into the auditory attention system, that is, a core system of working memory, based on greater electroencephalogram (EEG) coherence between fronto-central and occipital sites during a sound localization task. Since the occipital cortex was involved in all types of tasks regardless of task difficulty, the occipital cortex in the blind may not function as an additional supportive component that intermittently works only when tasks are difficult or complicated, but may work as a necessary component for working memory.

Working Memory Dependent Deactivation Networks in the Blind

Compared to the activation networks in the blind, the deactivation networks, especially the DMN, complicated the interpretation. It has been proposed that intrinsic brain activities under the default mode represent spontaneous, unconstrained cognition, as in stimulus-independent thought (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Norton, Van Horn, Wegner, Grafton and Macrae2007; McGuire, Paulesu, Frackowiak, & Frith, Reference McGuire, Paulesu, Frackowiak and Frith1996). In this context, intensified deactivation of the DMN in the blind, especially at the PCC, may be associated with their behavioral status, in that they more frequently experience the default mode state than the sighted because of their restricted behavior. That is, the blind may focus cognitive resources on a task by suppressing frequent but unconstrained thoughts.

In contrast to the above explanation based on the DMN involvement for spontaneous thoughts, regions within the DMN are also known to be activated by internally driven processes such as self-referential, or affective cognition (D'Argembeau et al., Reference D'Argembeau, Collette, Van der Linden, Laureys, Del Fiore, Degueldre and Salmon2005; Gusnard et al., Reference Gusnard, Akbudak, Shulman and Raichle2001; Wicker, Ruby, Royet, & Fonlupt, Reference Wicker, Ruby, Royet and Fonlupt2003) and future-oriented thoughts based on multiple episodic memories (Schacter & Addis, Reference Schacter and Addis2007). Therefore, intensified DMN deactivation during working memory in the early blind may also be attributable to altered utilization of the internally driven processes for the 2-back tasks.

Another explanation may be based on the difference in the attention reallocation in the blind. Working memory suffers most from competing stimuli that resemble the task at hand. For example, while visual distraction interferes with visual working memory, it has much less effect on auditory working memory (Della Sala, Gray, Baddeley, Allamano, & Wilson, Reference Della Sala, Gray, Baddeley, Allamano and Wilson1999). Accordingly, the blind may pay more attention to filtering auditory interference during auditory working memory processing because auditory information dominates their sensory input.

In addition to these interpretations, we cannot rule out the possibility that intensified deactivations in the DMN of the blind might just reflect the difference in imagination between the sighted and the blind in that it was remarkable only in the processing of verbal working memory. The nouns such as socks, pencil, and plate in the verbal task were highly imaginable, which raised the possibility that the sighted participants recalled images or activated visual-based semantic networks for these objects. Although blind people can use mental imagery on the basis of their experiences touching objects, such networks may be relatively underdeveloped in the blind. This possibility is supported by less obvious activation differences in the tone task and the lack of activation differences in the sound-location task between the sighted and the blind. However, it is not clear how imagination differentially involved in the 2-back and 0-back tasks in the sighted to make activation differences between these tasks less than that in the blind. Furthermore, it may not clearly explain the finding of deactivation of the DMN, regardless of stimulus imaginability, in all the verbal, non-verbal, and sound-location tasks in both sighted and blind people. Despite the possibility, we have to concede that these interpretations are only our speculation that requires further validation.

Alteration of Effective Connectivity Between Network Components for Working Memory

Among 30 independent components driven by ICA, we identified four working memory components, that is, the left and the right fronto-parietal components, DMN and occipital component. The two separated fronto-parietal networks located in each hemisphere were also found in previous studies (Damoiseaux et al., Reference Damoiseaux, Rombouts, Barkhof, Scheltens, Stam, Smith and Beckmann2006, Reference Damoiseaux, Beckmann, Arigita, Barkhof, Scheltens, Stam and Rombouts2008). According to Granger causality test, the blind had more connectivity among working memory components. Compared to the sighted, the blind showed bidirectional Granger causality between the DMN and both the left and right working memory components, which indicates a tighter and more reciprocal relationship between the DMN and traditional working memory circuits in the blind.

Note that the occipital component in the blind had a reciprocal connectivity only with the left working memory component, which was not found in the sighted. Furthermore, the inter-hemispheric effect of the fronto-parietal component was found only from the right to the left hemisphere compared to bidirectional effects in the sighted. These results are consistent with previous studies that showed left dominant occipital involvement in the verbal memory task (Amedi et al., Reference Amedi, Raz, Pianka, Malach and Zohary2003), and the auditory verb-generation task (Burton, Reference Burton2003). This left hemisphere dominance was also found in the occipital cortical thickness increase in the early blind (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Kim, Park, Oh, Lee and Kim2009). These results may indicate functional reorganization of the blind to use the left-dominant verbal processing efficiently to compensate for the visual deprivation.

So far, studies using various imaging techniques have revealed alterations in the cortical functional connectivity with the blind's occipital cortex. Transcranial magnetic stimulation was used to identify the connection between the occipital cortex and other sensory areas (Wittenberg, Werhahn, Wassermann, Herscovitch, & Cohen, Reference Wittenberg, Werhahn, Wassermann, Herscovitch and Cohen2004). A greater EEG coherence between the fronto-central and occipital sites during a sound localization task was observed in the blind (Leclerc et al., Reference Leclerc, Segalowitz, Desjardins, Lassonde and Lepore2005). Fujii, Tanabe, Kochiyama, and Sadato (Reference Fujii, Tanabe, Kochiyama and Sadato2009) observed a stronger and bidirectional occipital-parietal effective connection using dynamic causal modeling during a tactile Braille discrimination task. Klinge, Eippert, Roder, and Buchel (Reference Klinge, Eippert, Roder and Buchel2010) found stronger corticocortical connections from A1 to V1 in the blind during an auditory discrimination paradigm using dynamic causal modeling. These studies consistently reported increased functional connectivity in the occipital cortex in the blind, which was also found in the current study. Of note, increased connectivity between the occipital cortex and other brain regions was not observed during the resting state (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yu, Liang, Li, Tian, Zhou and Jiang2007; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Liu, Li, Zhou, Wang, Tian and Li2008) in contrast to enhanced connectivity during activation-based effective-connectivity studies in the blind (Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Tanabe, Kochiyama and Sadato2009; Klinge et al., Reference Klinge, Eippert, Roder and Buchel2010). This suggests that the occipital cortex of the blind is predominantly involved in attention demanding tasks (Liotti, Ryder, & Woldorff, Reference Liotti, Ryder and Woldorff1998; Roder, Rosler, Hennighausen, & Nacker, Reference Roder, Rosler, Hennighausen and Nacker1996; Stevens, Snodgrass, Schwartz, & Weaver, Reference Stevens, Snodgrass, Schwartz and Weaver2007). Therefore, the occipital cortex as well as the DMN may be involved in attention control in working memory processing.

Although the specific meaning of the connectivity increase in the blind still needs to be further investigated, the current results of activation and Granger causality test suggest that the occipital cortex of the early blind might not only undergo local functional reorganization but also reorganization of the network connectivity among working memory components. Furthermore, the DMN of the early blind was not only highly deactivated but also differently involved in working memory compared to the sighted.

In explaining the network alteration in the blind, an investigation of the anatomical connectivity in the blind would be highly informative. Indeed, diffusion tensor imaging studies have shown that the occipital cortex of the blind is found to have changes in white matter properties and in the anatomical connectivity with other brain regions (Park et al., Reference Park, Jeong, Kim, Kim, Park, Oh and Lee2007; Shu et al., Reference Shu, Liu, Li, Li, Yu and Jiang2009). Therefore, the anatomical basis of the network reorganization in the blind remains to be further researched.

Limitations of this Study

This study had several limitations. First, no standardized measures of general cognitive functioning were administered. However, since both groups had comparable higher education (14.5 and 14.8 years), we assume their cognitive functions were normal and similar. Second, to reduce the running time, we used 10 s-shorter block duration for 0-back tasks than 2-back tasks, and that might have affected the participants’ sustained attention. Although the duration difference would theoretically be a confounding factor, we regarded this difference as too short to reveal brain activation difference due to sustained attention. Third, to increase the reliability of the connectivity test and to find a common network connectivity difference across stimulus type, Granger causality test was applied to concatenated data. Therefore, further study with more time series for each stimulus type is needed to understand stimulus dependent functional connectivity. However, the current connectivity result delivers important information about the alteration in the working memory network, not only localized alteration within the occipital cortex and DMN.

Conclusion

In summary, the blind subjects showed alterations in the occipital cortex and DMN, and their effective connectivity in working memory processing. These findings suggest that the brain of the blind undergoes not only local functional reorganization of the occipital cortex and DMN but also reorganization of the cortical network as they adapt to the non-visual environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Basic Research Program of the Korea Science & Engineering Foundation (R0120050001052202006). There are no conflicts of interest.