A few days before the 1886 U.S. congressional election, Jerry O’Brien, a day laborer at the Union Iron Works Shipyard in San Francisco, looked up from his workbench to see a famous face coming through the door. State Assemblyman Charles Felton walked in as if he owned the place, an impression reinforced in the minds of the laborers who saw him by the sudden appearance of the yard foreman at Felton’s side. The foreman, a man named Arnold, had hired O’Brien and most of the other laborers in the yard. O’Brien watched as Arnold introduced the assemblyman to all the men he had hired, reminding them that Felton was running for Congress and “it was in the interest of the laboring man” to vote for him. Felton’s election, Arnold said, “means work for some of the men. Work for a couple of years.” Felton won, but his opponent challenged the legitimacy of the election before the House Committee on Elections. Among other crimes, the contested election case charged that Arnold and Felton’s joint appearance at the Union Iron Works Shipyard had intimidated the workers into voting for Felton. O’Brien was one of the men sworn in to testify in the case. He explained the reality of the situation: he and the other laborers had “understood that they were to vote for Mr. Felton,” or they would be discharged “in a very bad condition.” They were all, O’Brien said, “dependent for their support of themselves and their families upon the wages” paid out each week by the foreman who strode arm in arm through the foundry with the Republican candidate for Congress. How could they refuse him? During the last three decades of the nineteenth century, thousands of American men who worked for wages encountered similar subtle threats, felt the same fear of penury, and cast ballots they did not believe in to save their jobs.Footnote 1

This article assesses how and why the economic intimidation of voters became a nationwide crisis between 1873 and 1900. When considering workplace coercion in the Gilded Age, scholars tend to focus on union busting and exploitative employment practices—control over the workplace. This article explores how employers played on the precariousness of their employees to extend their control from the workplace to the polling place. This kind of economic voter intimidation was not an entirely new development in the 1870s. Individuals and parties seeking to corrupt elections before the Civil War typically relied on threats of violence or ballot fraud, but the 1840s and 1850s did see several instances of economic voter intimidation.Footnote 2 After the Civil War, bankers, employers, and landowners in the South used violent and economic methods of intimidation against African American voters almost as soon as they won their freedom in an effort to stop them from voting Republican.Footnote 3 After the Panic of 1873, however, the nation slipped into a deep recession and the growing ranks of wage-workingmen throughout the country confronted unprecedented economic uncertainty. With Democrats and Republicans locked in close conflict over critical issues from race relations to tariff protections, employers exploited their workers’ economic fears to control their votes. They relied on two methods to unduly influence the votes of their employees: they threatened to discharge them for voting the wrong way, and they sought to physically control their behavior on election day to make voting the wrong way difficult or impossible. These two methods of coercion recurred in industries in every region and were used by employers to inflate vote totals for both Democrats and Republicans. They were especially effective in company towns, where employers enjoyed the same autocratic power over housing, stores, and polling places that all employers had over the workplace itself.

When scholars have studied economic voter intimidation, they have often mistakenly treated all employer-employee interactions at the polls as a form of bribery.Footnote 4 Although bribery was widespread, when a laborer like Jerry O’Brien chose to cast a ballot he did not believe in to keep his paycheck, he did not stand to gain something illegitimately; rather, he was at risk of losing the wages he had already earned through his labor. He was being coerced.Footnote 5 Employers’ efforts to coerce their employees at the polls in the late nineteenth century shaped elections, damaged livelihoods, and eroded the promise of American democracy even for those who were ostensibly privileged by their gender and race. While African American voters were subjected to economic intimidation before 1873, the extension of similar practices to white workingmen during the 1870s fed a crisis atmosphere.

When the economic intimidation of white workingmen began to affect elections throughout the nation, legislators of both major parties, newspaper publishers, and socialist and labor reformers began to advocate for fundamental election reforms. They reacted so strongly because economic voter intimidation’s threat to white wage-workingmen’s independence fit into their preexisting fears over the future of universal manhood suffrage in an industrial nation.Footnote 6 For labor advocates and workers themselves, workplace coercion offered conclusive proof that industrial capitalism undermined their standing as equal citizens. Reformers and politicians fought for secret ballot reforms to separate workplaces from polling places in an effort to save democracy from capitalism, or vice versa. While papers and politicians debated the meaning of economic voter intimidation, employers throughout the nation opened a new front in the conflict between labor and capital by tying layoffs to votes and watching workingmen at the polls.

Coercion and the Labor Question

Well before the Civil War, as noted by historian James Connolly, wealthy and propertied Americans began to fear that the disruptions associated with precarious wage-work could damage the smooth functioning of business and government.Footnote 7 Those fears reached new heights in the 1870s and 1880s because they intersected with the ongoing national debate over the relationship between democracy and wage labor capitalism. Historian Rosanne Currarino described this “labor question” that obsessed workingmen, reformers, and politicians in the Gilded Age as a struggle over “how to reconcile a permanent class of wage-workers with a nominally republican society.”Footnote 8 The logic of universal male suffrage held that voting-age men were by definition economically and politically independent citizens capable of casting a ballot of their own choice. Yet as the promise of eventual economic independence—which was central to the predominant free labor ideology—increasingly proved hollow in the decades after the war, the “intensifying dissatisfaction” of wage-workingmen grew exponentially.Footnote 9 Men of all races who labored for wages in the United States experienced the last three decades of the nineteenth century as an era of “proletarianization, drastic economic instability, worker unrest, and a volatile job market.”Footnote 10 Workingmen’s precariousness fed back into their vulnerability at the polls. As a Senate committee investigating Massachusetts elections in the late 1870s explained, employers who desired to were able to control their employees’ votes by “pressing upon the necessities of workmen.”Footnote 11

The right to be free from “coercion without due process of law” and the ability to exercise “the right to suffrage” were, legal historian Barbara Young Welke argued, core privileges of being white, male, and able to provide for oneself in the nineteenth century.Footnote 12 Thousands of Americans who experienced or observed economic voter intimidation in the 1870s and 1880s feared that capitalism and universal manhood suffrage could not coexist if white men’s political rights could be held hostage by their employers. Politicians and reform advocates dismissed economic coercion as a nuisance problem when it mostly affected African Americans; when it struck white workers with full force during the “Long Depression” of the 1870, ’80s, and ’90s, however, economic voter intimidation suddenly assumed the dimensions of a crisis.Footnote 13

As early as 1867, newspapers and congressional investigations reported that employers were threatening the “means of subsistence” of newly enfranchised African Americans if they tried to vote Republican. They continued to do so for decades. In 1876, the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean newspaper described workplace coercion as one part of the “intricate machinery of intimidation, restraint, and violence” that Democrats used to control elections in southern states.Footnote 14 As one Georgia voter testified in a contested election case in 1892, it had become “the custom” across the South for “those working in large industrial institutions” to vote the way their employers directed them for fear of discharge.Footnote 15 Many white Americans, however, rationalized the economic intimidation of African Americans by arguing that their racial inferiority made them more susceptible to intimidation. African Americans, one letter writer to the New-York Tribune explained in 1877, had a “habit of servility and dependence” that rendered them dangerous holders of the suffrage.Footnote 16 White men, because of their presumed racial superiority, were not supposed to be vulnerable to these kinds of economic threats on election day.

As thousands of white men began encountering coercion at their workplaces during the 1870s, however, it became impossible to sustain the delusion of white manhood’s superiority. Many Americans began to worry that the precariousness of these ostensibly politically privileged men could threaten the existence of democracy or capitalism, or both. A socialist organizer and machinist named T. J. Morgan appeared before a congressional committee in Chicago in 1879 to explain that he believed the federal government should assume ownership of “the railroads and telegraphs of the country” as a way to stop those companies from intimidating their workers. He acknowledged that government control could lead to abuses, but such abuses paled in comparison to “the iron hand of physical force” that private employers used to control the votes of their employees.Footnote 17 A Chicago iron-molder named George Rogers made the opposite argument to the committee: if the government took over the railroads, steamboat lines, and telegraph companies, Rogers claimed, then “the party in power would control their votes … and by and by there would be no right of franchise in this country at all.”Footnote 18 Wherever they came down on the issue of the nationalization of private industry, workingmen were convinced that economic voter intimidation was a pervasive problem that demanded federal attention. It was such a serious issue, they argued, that the federal government should take economic voter intimidation into account when making nationwide economic policy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: An example of a typical ballot of the era for a midterm election in 1878. Note the prominent placement of the word “Regular” at the top of the ticket, emphasizing that these are the official candidates of the party. Factions often split off during this era and printed their own tickets, going by names such as “State Democracy” or “Independent Republicans.” 1878 Massachusetts Democratic Ballot, Collection of Election Ballots: 1827–1889, American Antiquarian Society, Box 2, Folder 2.

The destructive consequences of economic voter intimidation contributed to and shaped the labor upheavals that roiled the nation during the 1880s. A Union army veteran named James H. Blood explained in a letter to a Senate investigative committee in 1883 that economic voter intimidation was driving workingmen to express their political grievances violently rather than politically. “The natural order of industrial development,” Blood argued, had undermined the ability of workers to make “necessary reforms … through the means already provided; that is, the ballot.” Using their political rights to advocate reform was their first choice, but employer coercion was rapidly eroding that option. As Blood explained to the committee, workers were aware that their opportunities to improve their economic and social standing through legal political avenues were “becoming fewer year by year as corporations acquire[d] more and more the control of the votes of their employees.” Blood hoped that “despite the intimidation to which they will be subjected,” workers would unify to “assert their interests” peaceably.Footnote 19 But he left no doubt as to the strength of the forces opposing laboring men. The more votes employers captured, the more difficult reform would become. As a different workingman told the same committee, “our only equality is our ballot.”Footnote 20 Workingmen’s political equality was precious to them. If laboring men lost their belief “in the popular ability to obtain, through the ballot, whatever is worth having,” then, as journalist George Frederic Parsons worried in the Atlantic Monthly in 1886, they would turn to socialism.Footnote 21 As a “great upheaval” of over 1,400 strikes swept the nation that year, Parsons had every reason to believe that workers who did not trust in peaceful, democratic reform would reenact the revolutionary violence of the 1871 Paris Commune.Footnote 22

Parsons and others who warned of the threat of economic voter intimidation were concerned that it would convert labor advocacy into radical revolution by convincing working-class men that they could not gain reform peacefully by winning elections. Between 1873 and 1890, a chorus of union leaders and reform advocates testified before investigative committees and in contested congressional election cases that coercion posed a serious threat to national stability.Footnote 23 The editorial and news pages of labor newspapers were filled with calls for laborers to fight back against the threat of undue influence by corporations.Footnote 24 The crisis rapidly made its way into the party platforms of radical leftist parties, most notably the Socialistic Labor Party, which expressed concern in its platforms throughout the 1880s that inequalities in industrial life could “destroy liberty because the economical subjection of the wage-workers to the owners of the means of production leads immediately to their political dependence upon the same sources.”Footnote 25 Everywhere they could, workingmen raised the alarm about the threat that employers’ coercion posed to their own independence and to the government and industry of the nation. In their pleas for help, workingmen decried two nonviolent coercive techniques that employers used to control their votes that their economic precariousness had rendered them helpless against: discharge threats and poll observation.

The Discharge Threat

The core of economic voter intimidation was the threat of discharge from employment. The form and seriousness of the threat varied, but its mechanics remained relatively constant. Although economic voter intimidation had taken place in isolated elections throughout American history, the disastrous Panic of 1873 and the precarious economic conditions it ushered in for the next twenty or so years dramatically increased the incidence of coercion. As historian Heather Cox Richardson described, “competition for jobs in a flooded labor market meant below subsistence wages for many unskilled workers.”Footnote 26 In those economic conditions, getting fired on election day could very well mean a starving winter for a working-class man’s family. The Labor Herald, the Knights of Labor’s official newspaper in Richmond, Virginia, asked workingmen in 1886: “how many weeks of enforced idleness separate you from utter destitution?”Footnote 27 Many Americans during the Gilded Age would have answered that only a week or two of unemployment separated them from penury. The desperate economic context of these men could render nearly any expression by their bosses of their political leanings into a threat.

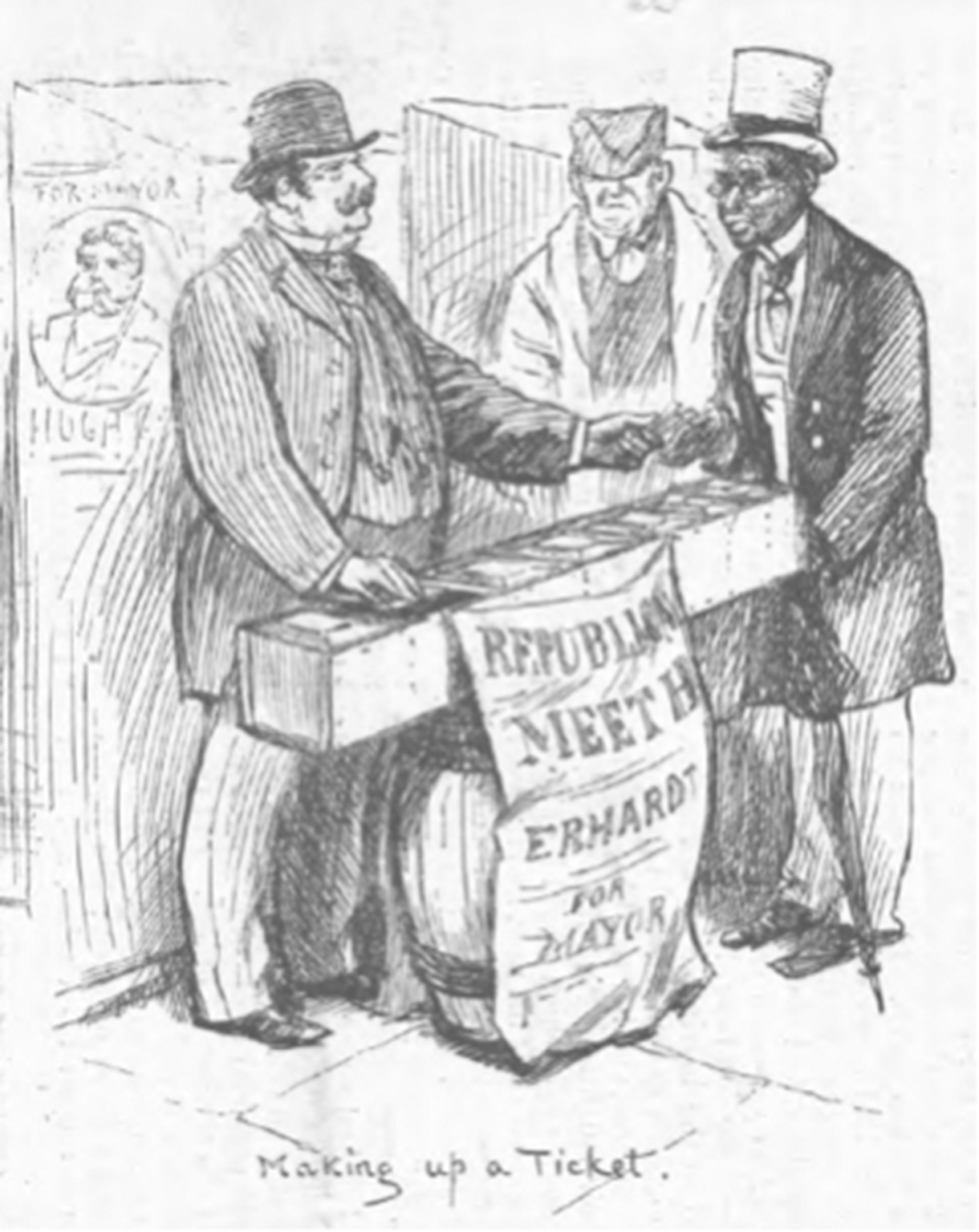

Depending on the employer, the industry, and the employee’s ethnicity, such threats were made subtly or forcefully. The most forceful threats are not difficult to discern in the historical record, nor were they confusing to contemporary observers. For example, when a labor leader testified to a congressional committee that laborers in Chicago could not exercise their ballots freely, Congressman Henry Dickey of Ohio incredulously asked if the man really meant that the “corporations who employ them threaten to discharge them if they do not vote in a particular manner?” When the witness answered in the affirmative, Dickey denounced the practice as a despicable form of “bulldozing.”Footnote 28 In 1888, the New York Times censured “all kinds of covert threats” including firings, mill and factory closings, and the replacement of workers with immigrants. The Republican bosses of New York, so the Democratic-leaning Times claimed, used these threats “to frighten the laboring men into giving up their independent right of suffrage.” The Times noted that such methods were “clearly ‘intimidation’ within the meaning of the law” and should be treated just as seriously as election day violence by state and federal officials.Footnote 29 By the 1880s, Democratic and Republican newspapers and politicians acknowledged that threatening a voter’s job was a criminal violation of their political rights. They did not, however, have a plan for how to stop it (Figure 2).

Figure 2: One vignette from Harper’s Weekly’s 1888 “Scenes and Incidents of Election Day in New York.” The magazine published a similar illustration after each presidential election. In this case the drawing shows a Republican ticket pusher handing a ballot to a well-dressed man of color while a heavyset and somewhat rumpled white man looks on. The absolute lack of privacy depicted in this scene is entirely typical of the process of selecting a ballot before the introduction of the secret ballot. W.A. Rogers, “Scenes and Incidents of Election Day in New York,” Harper’s Weekly, November 17, 1888, 876.

The road work crews in Portland, Maine, experienced a particularly overt form of discharge threat from their foremen during a congressional election in 1880. The workers were terrified of losing their jobs just as the awful New England winter arrived, but at least one man resisted the entreaties of his boss and chose to go home instead of voting for a Republican ticket he did not support. The rest of the road workers dutifully took the ballots handed to them by their bosses and trudged to the polls. As they left the job site, their overseer called after them: “Mind how you vote, boys; vote for your bread and butter. If you cut my throat now I’ll cut yours hereafter. I am on your track and will camp on it.” With this threat ringing in their ears, a bricklayer whispered to the Democratic poll workers they passed that “this is not the ballot I would vote could I help it.” But what could he and his coworkers do? One of the foremen came with them to the polls. He stood just five feet away as they slipped their open ballots into the box, each of them knowing, as one laborer later testified in the election contestation, that the foreman had “no use giving me work if I went against his party.”Footnote 30

Discharge threats were effective on a far larger scale than a dozen or so outdoor laborers in Maine. John McAulif, a socialist and engineer, told a congressional investigating committee that thousands of workers in Chicago were “under threat of being discharged unless they vote as their employers dictate.” Employers as diverse as the street railways, the gas company, the stockyards and packing houses, and building contractors, he claimed, bulldozed their workers regularly. And since “discharge from employment means want of bread and consequent misery to the workingmen” in a difficult labor market, he believed that these efforts were generally effective. McAulif calculated that “out of fifty-five or sixty thousand voters in Chicago there are from fifteen to twenty thousand of them who are bulldozed.”Footnote 31 It is difficult to know whether McAulif’s calculations were accurate, but no one sought to refute the central premise of his testimony: discharge threats existed on a large scale and in a variety of industries (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A copy of a “political pay envelope” allegedly given to the Waterbury Evening Democrat by an employee of the Farrell Foundry and Machine company during the 1888 presidential election. “Protection Envelopes,” Waterbury Evening Democrat (Waterbury, CT), October 4, 1888.

More subtle discharge threats, however, often fell into a legal gray area, subject to debate over whether they were intimidation or just conversation. Threatening large numbers of workers at once required far more subtlety than the road work foremen in Maine exercised in their little fiefdom. The story related by Jerry O’Brien, the laborer in the Union Iron Works Shipyard in San Francisco that served as the opening anecdote for this article, is a good example of how an ostensibly gentle suggestion from a man in a position of power could shape the votes of hundreds of workers. The shipyard foreman told his employees that voting for Felton, the Republican candidate, would mean jobs for some of the men for two years. The shipyard workers had no reason to disbelieve him. Whether such suggestions counted as intimidation was the subject of endless debate and recrimination in the contested election case brought by the losing candidate in that election. The superintendent of the shipyard, Irving M. Scott, unequivocally denied that he had illicitly tilted the scales toward Felton. When pressed, Scott declared that in his shipyard, “there is no such thing as intimidation so far as men’s votes were concerned.” However, he did not deny inviting the Republican candidate to visit the foundry floor, offering in his defense only that he had extended the invitation to other candidates as well. Far more damningly, while Scott maintained that his foreman would never have “used any intimidation because it is against our rules,” he confirmed that the foreman probably had said that Felton would bring work to the shipyard, because “all good congressmen would.”Footnote 32 No one had explicitly stated that workers would be fired if they voted the wrong way, but the wage-workingmen who were the targets of such persuasion believed that discharges awaited anyone who went against their bosses’ political choice. That belief was just as powerful as an explicit threat.Footnote 33

Discharge threats in factories could also be concealed as part of so-called “campaigns of education,” particularly when campaign issues aligned with the concerns of large employers. During the 1880s, educational campaigns—efforts to sway voters by convincing them that one side or another offered greater economic benefits or protection to them individually—gradually replaced the marches and rallies common to popular politics in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 34 The democratic rituals of the popular style had always seemed to exude a stench of graft to the primarily upper-middle-class reformers who advocated for “pocketbook”-focused educational campaigns. In 1889, the former Democratic governor of Ohio, George Hoadly, described a campaign of education as the only “legitimate method of political warfare.” But in endorsing more issue-based campaigning, he overlooked how employers could conceal coercive demands within otherwise “honorable and legitimate” campaign messages.Footnote 35

Republican bosses used seemingly educational messages concerning the omnipresent tariff issue of the 1880s to launder coercive messages targeted at their employees. For example, laborers arrived for work in the Sanford Mills in Maine one morning just before the 1880 federal election to find their workplace plastered in notices announcing, as one worker reported, “if the Democrats came in power it would necessitate the shutting down of their mills.”Footnote 36 Another witness testified that one of his coworkers switched his vote to the Republicans because he was afraid that he would “probably lose [his] job … if he voted the democratic ticket.” Others, having seen the placards in the mill, worried more generally that “if the Democrats succeeded in electing the next House and President that the tariff would be taken off, and the mills be forced to shut down.”Footnote 37 The witness himself seemed unsure whether what he was recounting constituted illegal voter tampering, but it was certainly not the reasoned appeal to votes that reformers believed an educational campaign to be. He concluded that the workers were “probably more or less” intimidated by the tariff messages from their bosses as they were worried that losing their jobs would lead to penury.Footnote 38 Similar incidents of tariff-related propaganda in workplaces that workers interpreted as veiled threats to their livelihoods occurred throughout the decade of the 1880s in New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York.Footnote 39

While most discharge threats originated with employers who had a personal or economic stake in an election, coercive pressure could also be transmitted from parties or candidates to employers and then on to employees. The case of Robert F. Jennings, a white tobacco warehouse worker in Danville, Virginia, in 1882 provides a telling example. Jennings was a strong supporter of the biracial Readjuster Party. He had shrugged off Democratic efforts to change his political allegiance until one day when he arrived at work to find that if he wanted to keep his job, he would need to change his vote. His bosses had sought to steer clear of politics until representatives of the local Democratic Party told them in no uncertain terms that if they did not discharge Jennings, then “their discounts should be cut off at the bank and … tobacco would not be sent to their warehouse.” The “coercion and ostracism” levied against Jennings’ employers and through them on him proved too much for him to bear and he was soon seen marching in a Democratic rally by Readjuster-leaning voters.Footnote 40

Discharge threats were less common outside industrial workspaces, but they still cropped up in congressional investigations and newspaper reports. In Virginia in 1888, the forty or fifty employees of the Stewart Land and Cattle Company “had been given to understand that they must vote the Democratic ticket or lose their places.” However, as in industrial sites like the Union Iron Works, the subtle nature of the discharge threat made it difficult for the Virginia ranch hands to prove their case. The Republican contestant who had lost the election produced witnesses who testified that it was “generally understood in the community” that giving up their vote to the whims of their bosses was “one of the conditions of employment” that all ranch hands had been forced to accept.Footnote 41 Agricultural coercion was not limited to the South. A reporter writing about Michigan elections for the Nation in 1889 noted seemingly without concern or surprise that “the farmer’s ‘help’ of to-day is a very different sort of personage from the farmer’s ‘hired man’ of ante-bellum days.” In the new economy of the 1880s, the reporter wrote, a prosperous farmer expected that his “‘help’ will go with him to the polls and vote as he directs.”Footnote 42 If they refused, the farmer would presumably find other help during the harvest.

Employers and employees saw discharge threats as so effective at controlling workers’ votes that bosses often felt comfortable openly bragging about their successes. A construction boss in Portland, Maine, proudly told a business acquaintance he ran into on the street after the 1880 congressional election that he had driven dozens of men to vote for the Republican candidate by asking them “where they got their bread and butter” and threatening to look elsewhere for labor if they took a Democratic ticket.Footnote 43 Recounted as part of a contested congressional election case, the most noteworthy element of the otherwise standard discharge threat is the remarkably casual nature of the boss’s confession—particularly as the man he confessed to was known to be a close, personal friend and political supporter of the Democratic candidate!

Observation and Control on Election Day

A discharge threat could be issued days or weeks before election day and repeated as often as seemed necessary. Because they did not have to be issued at the polls, they were especially difficult to combat through anti-intimidation law. But a threat, even an existential threat delivered multiple times, is only effective when it is enforced. To back up their threats, employers throughout the country developed a repertoire of election day tactics to impress upon their employees just how extensively they controlled their lives. By pairing subtle or overt discharge threats in advance of an election with direct control or observation of employees on election day, bosses were able to control their employees’ political expression. Many election day tactics often seemed friendly or unimportant when shorn of context, providing employers with legal cover during the frequent congressional and journalistic investigations into electoral shenanigans during the 1870s and ’80s. Workers subject to such methods, however, were well aware of their coercive intent.

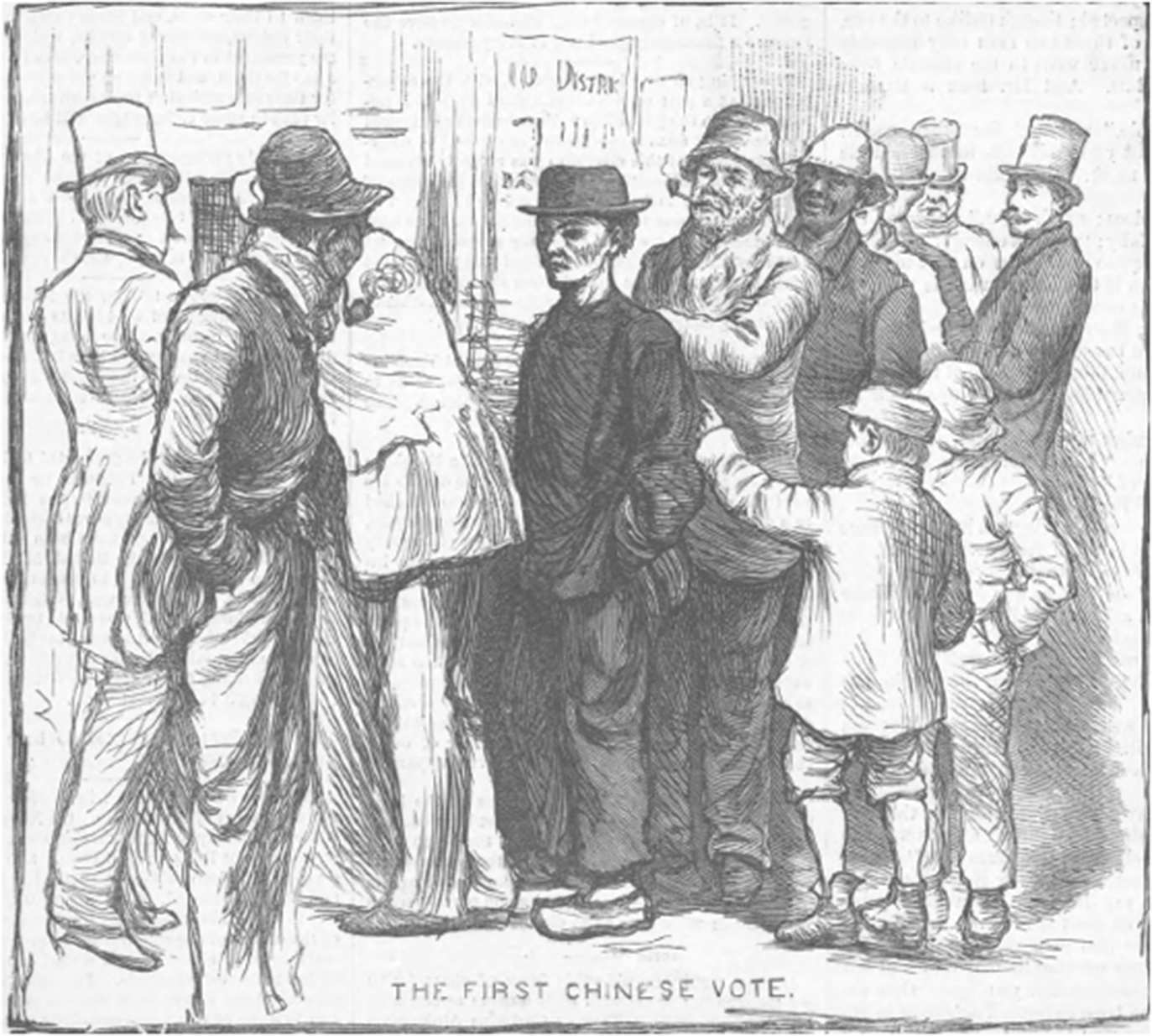

Perhaps the most common element in testimony of economic intimidation in any large workplace was the offer by a boss or foreman to their employees of a free ride to vote. Modern scholarship has sometimes erred in classifying these offers to “send a carriage to bring the voter to the polls” as a benign element of parties’ get-out-the-vote campaigns.Footnote 44 Sometimes they were indeed friendly gestures, but in workplaces where employers sought to leverage their economic power for political purposes, the physical control inherent in a company-provided wagon ride to the polls offered a powerful vector for coercion. The simple but effective “starch factory system” in Oswego, New York, involved the factory bosses “getting their employees to the polls on election day and watching them there until they vote.”Footnote 45 Control of when and how their workers got to the polls made the second half of the system—watching and controlling how they voted—far easier as bosses were able to make their way “down to the polls first” as the wagons were being readied to see that their men took the right tickets (Figure 4).Footnote 46

Figure 4: This balloting scene from the 1880 version of the Harper’s Weekly election day illustration depicts a Chinese man in line to cast a ballot. Though the illustrator was interested in the ethnic identity of the voter, this depiction of the polling place is typical of the lack of privacy for voters while casting a ballot. Standing just to the left of the polling window is a well-dressed man in a top hat seemingly watching each ballot as it goes in the box. S.G. McCutcheon, “Scenes and Incidents of Election Day in New York,” Harper’s Weekly, November 13, 1880, 728.

With a little coordination, employers could enjoy near total control of the circumstances in which their employees voted. In Minneapolis, Minnesota, employees who worked on the railroad, at the state’s largest woolen mill, and at the largest agricultural implements factory testified in 1880 that on election days, their bosses carried out a “system of coercion and intimidation” to control their votes. Much as in Oswego, the foreman or employer marched their men to the polls, where “ballots were there placed in their hands, folded, and voted by the employees without being opened.” In the case of the laborers at the North Star Woolen Mills, they were escorted to the polls and watched over by the son of the mill owner, whose presence impressed on them that they would “lose their means of subsistence” if they voted the wrong way. The bosses knew the political leanings of their employees intimately; those they suspected of having strong opposing views or who might cause a scene at the polls were simply kept on the job all day and not permitted to take time off to vote. The presence of “large numbers of employers of labor” at the polls in Minneapolis attracted the attention of Democratic poll watchers. One poll watcher tried to talk to the line of laborers to see how they were voting but was cut off by one of the bosses who declared that “he had brought the men there himself, and that most of the workmen voted as their employers wanted them to.” This was undoubtedly true. Workers “whose means of life depended upon the good-will of those who employed them” had few options when their bosses stood over them at the polls.Footnote 47

If they were careful, control of when and how their workers went to the polls gave employers the ability to prevent opponents or election observers from asking awkward questions of their employees or otherwise interfering with their coercive techniques. One man running for municipal office in San Mateo, California, in 1886 believed that the powerful Spring Valley Water Company was intimidating its employees into voting against him. He dispatched a man to the polls “to go there and see that everything was conducted fairly and to look after my interests.” The attempt to discover voter intimidation failed, however, when the poll watcher arrived at nine in the morning to find that the company’s workers had, at the behest of their foremen, “all voted before he got there!”Footnote 48

Control of employees on election day could even outweigh the efforts of white supremacists to prevent African Americans from voting in the post-Reconstruction South. In Petersburg, Virginia, in 1896, the city police stretched a rope around the polls. A Republican ward heeler testified in a contested congressional election case that white men “voted as they came up” to the polls, while African American men were “kept back and prevented from voting in preference to the whites, presumably in hope that they would give up and leave.” The exception to this system emerged when the eight African American men who worked at the local city asylum were marched by their boss to the polls. These men were ushered around the rope and allowed to enter the polls immediately. Within ten minutes, they had all voted Democratic and begun their walk back to the asylum. When asked how these eight African American men were able to circumvent the racial politics of Virginia so adroitly, the witness explained that the asylum workers had not truly been able to make an independent political choice: “they have to vote, generally, the Democratic ticket to keep their positions.”Footnote 49 The example of the asylum workers demonstrates how one form of coercion could be layered atop another. The presence of their boss at the polls and his implied discharge threat, coupled with the barriers that all African Americans faced at the polls, meant that the asylum workers must have felt that they had no option but to cast the chosen ballot of their boss. It may not have been the ballot of their choice, but they were well aware that if they opposed their boss’s wishes, then they would lose their jobs and assuredly be banished beyond the rope around the polls that African Americans were rarely allowed to cross.

Mechanisms of election day control could be effective no matter the scale. Jeremiah O. Brion, a carriage driver, woke up on election Tuesday in 1880 in Portland, Maine, with the intent of casting his ballot for the Republican incumbent, Thomas Brackett Reed. Brion’s employer had other plans. That morning, Brion arrived at his boss’s home, readied the carriage, and was immediately dispatched on a thirty-mile round trip to the town of Yarmouth. Afraid “to disobey lest he be discharged,” Brion made the trip as quickly as he could but failed to make it back to his precinct in time to cast his ballot.Footnote 50 Employers’ control of their employees’ work hours, even in a relatively unstructured job like carriage driving, gave them the ability to prevent their employees from voting at all.

Everyone in this era seemed to have a story or two of economic intimidation to share. The permeation of knowledge about these methods into the minds of workers made it easier for bosses to intimidate them come election day. As a factory worker in upstate New York testified during an 1878 contested congressional election case, it was “common talk upon the public streets” that factory bosses intimidated their employees at the polls.Footnote 51 In Scranton, Pennsylvania, the foreman of a local coal mine posted himself across the street from the polls and made certain that everyone heard him when he yelled out “we will have to see to that fellow” each time he spotted a miner voting the wrong ticket.Footnote 52 The lack of secrecy was no accident. By the 1880s, employers could invoke a wide-ranging repertoire of methods of economic intimidation, comfortable in the knowledge that their workers were well aware of the existence and effectiveness of these methods. Even after the introduction of the secret ballot and other reforms made intimidation at the polls far more difficult, the knowledge possessed by nearly every American worker of what employers had in the past done to their employees was in and of itself a powerful coercive tool. Workers who were aware that colleagues in similar circumstances had lost their jobs on account of their votes were less likely to oppose even subtle political suggestions from their bosses.

“In the Very Air of Almaden”: The Company Town

The methods of economic intimidation practiced in company towns were similar to those used in less totalizing workplaces. The primary difference was that employers in company towns had more levers of coercion to use against their employees, rendering economic voter intimidation even more overt and effective. In company towns, employers dictated the employment, housing, shopping, and movement of their employees. Two elections in particular shed a great deal of light on voter coercion in company towns. A case from Northern California in 1886 detailed the methods of intimidation, bribery, and undue influence practiced in Almaden, the company town of the New Almaden Quicksilver Mine, while a Senate investigative committee unearthed similar techniques in the mill towns of Massachusetts in 1878–79.

The contested congressional election case of Frank J. Sullivan (D) v. Charles N. Felton (R) that contains the story of the company town of Almaden owes its unprecedented wealth of evidence to the loser’s extraordinarily high opinion of himself. Eschewing modesty, Sullivan described himself in an open letter to prominent congressmen as “a type of the perfect man … the very model of prodigious strength, combined with perfect symmetry.”Footnote 53 Whether or not he was perfectly symmetrical, Sullivan was an attorney by trade and thus managed to avoid the expense of outside counsel by conducting many of the depositions himself. With few financial constraints and a damaged ego desperately in need of salving, Sullivan tramped the length of the district, from San Francisco to Santa Cruz, interviewing anyone who had a story to tell about the election he had lost. Sullivan found himself spending much of his time in San Jose, the nearest open town to Almaden, where thousands of native-born, Cornish, and Mexican laborers toiled in the mercury mines and trudged home every day to shacks owned by their employers. Though he was ultimately unable to convince the House Committee on Elections to overturn the election result, Sullivan deposed hundreds of miners, former miners, teamsters, shopworkers, and delivery boys who had passed through Almaden in the previous decade, creating an extensive record of the coercive methods used by employers in the company towns of the Gilded Age.Footnote 54

The mechanics of election day in Almaden resembled those of coercive workplaces throughout the nation, remarkable only because of the extent of control over workers that the company town provided the bosses. Voters heading to the polls picked up their ballots from the company store, which was entirely controlled by the mine. Ballots for both parties were available at the store counter, but they were of noticeably different shades. Witnesses testified that when Almaden employees handed their ballots to the ostensibly nonpartisan inspector at the polls, he would “hold the ballot in his hand” and read off the voter’s name for the clerk before depositing it in the ballot box. The color difference was readily visible to all during this process. Meanwhile, the mine’s cashier stood inside the polling place holding a book containing the names of all the registered voters in the mine. A negative mark from his pencil was widely believed to lead to instant dismissal (Figure 5).Footnote 55

Figure 5: This Harper’s Weekly cartoon from 1888 depicts ticket pushers in New York City. It is a highly stylized image: the candidates themselves are handing out ballots from booths emblazoned with derogatory and embarrassing banners while a parade of “Independent Voters of New York” representing men of all classes confidently wave off their entreaties. Exaggerations aside, the cartoon shows in broad terms what ticket pushing outside the polls looked like. William Allen Rogers, “The Irrepressible Independent,” Harper’s Weekly, October 20, 1888, 803.

Sullivan charged that the very nature of the company town was destructive of political independence. He argued that “any body of men that will submit” to such an exploitative system as the company town “would necessarily surrender the franchises to the owners of that or any other mine.” Former employees confirmed that “freedom of contract … action … sale … purchase or … expression are utterly unknown” among the miners. To those willing to testify, the mine seemed a “kind of serfdom” or “slave pen.” When one of Felton’s attorneys asked a former employee if he had ever been a slave, he replied “no sir, never, only while I was in Almaden.” Rhetoric of slavery, lack of control, and dependence fills the testimony about Almaden. In one telling exchange, Sullivan asked a teamster named George Corey, who made regular deliveries to the mine store, whether it was “understood by all the people there” that voter intimidation was “in the very air of Almaden?” “Yes sir. By all,” Corey replied.Footnote 56

The testimony that Sullivan collected presented an awful picture of labor conditions in Almaden. Quite reasonably, one of Felton’s attorneys asked a laborer who had worked in Almaden for years and had testified that he gave up his vote and put his life at risk in the poisonous mercury tunnels why, “if it was such a terrible place that a man … would be willing to work there again?” The miner helplessly replied that “poverty will make a man do most anything.” Unable to find other work, he was willing to sacrifice his vote and potentially his health for a living wage. For miners who relied on Almaden as the only stable source of employment nearby, being discharged “and thereby prevented from being able to support themselves or their wives or children,” as Sullivan put it, was an existential concern.Footnote 57

In mill towns of Massachusetts, political freedom was subject to restrictions similar to the mining towns of California. Coercion of voters in these mill towns in the late 1870s became a nationwide scandal and resulted in an extensive investigation by a Democratic-controlled Senate committee. The report that the committee produced ran nearly 500 pages and contained extensive documentation “that employers of labor in those states coerced their employees to vote as the employers wished, and that deprivation of employment was the penalty for refusal to do so.”Footnote 58 Perhaps the most compelling testimony came from a former state representative, James H. Mellen, who described how little control over his life a mill worker in Massachusetts really possessed: “the operative lives in a tenement, belonging to the manufacturer; his wages are small; his wife probably works in the mill; his children probably work in the mill.”Footnote 59 Any employee who seemed “fractious, or opposed to voting in the way that these people dictate,” Mellen explained, would find himself and his family “turned out of the mill, out of the tenement, and out of the means of earning a livelihood.”Footnote 60 The investigation rapidly focused on these mill towns, uncovering extensive evidence of how bosses exploited the dependency of their workers to subvert their vote.

Control of housing and employment meant that bosses found it relatively easy to control their employees’ political expression in these mill towns. During the 1878 gubernatorial election, a retired war veteran named Terrence Kennedy lived with his son and relatives, most of whom worked in the Manchaug Mill in western Massachusetts. Kennedy tried to organize a speech in favor of Benjamin Butler, a renegade former Democrat and former Republican running on a pro-labor platform.Footnote 61 Even though he was not employed directly by the company, the mill owned the tenement his family lived in, and the mill owner decided to make an example of them. Eviction and discharge notices were delivered to the Kennedy family before the election to impress on their neighbors the seriousness of defying the company come election time. Still, the family was allowed to stay in town through the election and its eligible voters were permitted to freely cast their ballots. Their individual votes were less important to their bosses than their presence as living and breathing symbols of the consequences of exercising political freedom in a company town. With employment and housing in town directly controlled by the company, the family was forced to resettle miles away. One eviction notice was sufficient to cow the other Butler-leaning workers. These “men who had families dependent upon them” snuck over at night to tell their beleaguered colleague that they still wished to vote their consciences but that “it was coming near winter and they did not wish to lose their jobs.”Footnote 62 After all, on election day in Manchaug, standing next to the polls handing out the company approved ticket and watching how everyone voted was the Manchaug Mill bookkeeper.Footnote 63

The Senate committee investigating the conduct of elections in New England received far more complaints of employee intimidation from small mill towns like Manchaug than it did from larger towns and cities. In his testimony, former state congressman Mellen explained that this disparity existed because manufacturers were “more in dread of public opinion” in cities than they were in company towns “where a single individual is almost an autocrat” and no independent newspaper was available.Footnote 64 Days later, the tiny town of Douglas, Massachusetts, provided the committee with a compelling example of the dynamics Mellen had described. The Douglas Axe Manufacturing Company provided employment for all 300 workingmen in town. Coincidentally, the poll workers, ticket pushers, and vote challengers in Douglas were exclusively made up of the foremen and salaried employees of the company.Footnote 65 One foreman stationed himself just in front of the polls where each employee carrying their ballot “would have to pass under his eyes.”Footnote 66 Few made the choice to offend their employers. Though one of the poll-watching foremen joked to the committee that he would not “undertake to dictate to the men in the shop … they are axe makers” and claimed that if he made a political suggestion to which they were averse he “would get the worst of it,” he dramatically underrated the power he held over his employees in such a town.Footnote 67 Even if the threat that his presence at the polls implied was solely economic, unemployment and homelessness in the winters of 1878 and 1879 was far from a pleasant prospect. Such threats worked in part because the isolation of workers in company towns in Massachusetts meant that there was little opportunity for vulnerable workingmen to rally support or find alternative employment.

Helpful in concealing the destructive nature of economic voter intimidation in company towns was how innocuous it could seem when shorn of context. Peter J. McGuire, the president of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, explained to a Senate committee how economic coercion operated in the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company mill town in Manchester, New Hampshire, in the early 1880s. The bosses were careful, McGuire explained, to avoid “direct intimidation—coming to a man and saying, ‘you must do this or else be discharged.’” Instead, every employee in the mill was told “that his boss or his overseer is going to vote such and such a ticket. He is told that more than once probably, more than once a week perhaps, until the election day comes, and then his ticket is watched very closely to see how he votes.” Though no threats of violence were levied against the workers, “the system of intimidation is so wily and subtle that a man hardly feels it, but still he is made conscious of it.” As in Almaden and Douglas, the mill bosses controlled the context in which their employees worked, lived, and voted. That control guaranteed that the Amoskeag workers went to the polls with no doubt in their minds that when winter came and discharges became necessary, “a great many of them will occur among those who have not voted the ticket that their overseers desired.”Footnote 68

Not all bosses in company towns enjoyed such extensive control over their employees as in Almaden and the mill towns of New England. But even without exhibiting direct control of housing, leisure activities, or newspapers, simple geography frequently endowed employers with powerful levers of coercion. In such cases, the isolation inherent in itinerant extractive industries, especially in the West, combined with restrictive registration laws to provide employers with more than enough leverage to subvert their employees’ political freedoms. Newspapers supporting both parties detailed how mine owners moved workers to new work sites outside of their home districts just days before elections.Footnote 69 As most counties and municipalities mandated that voters reside there for a certain amount of time before an election in order to vote, large corporations could disenfranchise workers who lived in company towns with disturbing ease by simply shifting their work and living sites to a different company town. These job transfers on or before election day took advantage of the workers’ economic precarity to deny them their vote. Such methods were all the more effective when levied against men living in company towns like mining camps, as they risked losing their homes as well as their livelihoods if they protested.

During the 1884 federal elections in northern Ohio, a precinct known as Kelley’s Island provided an example of how company town coercion could become violent. Kelley’s Island, located in Lake Erie just north of Sandusky, is now mostly a quaint tourist destination, but in the late 1880s it was home to a large stone quarry owned by the eponymous Norman Kelley. Concerned about the effects of Democratic tariff policies on his business, Kelley threatened to discharge half of his seventy employees if the Democrats won, though he emphasized that he would “naturally expect to retain those who voted for our interest and their own” when the discharges began. Isolated on a small island with no other prospects for employment in their trade should they be discharged, the quarrymen faced the same threat to home and community as did those in company towns where bosses directly owned their homes. The seriousness of Kelley’s threat provoked resistance. A stonecutter and Democratic poll watcher named Nicholas Smith confronted Kelley at the ballot box while he was heckling his employees. Demanding to know “why don’t you let your men have their own free will?” Smith shoved Kelley, precipitating a short fistfight but failing to remove Kelley from his poll-side observation post.Footnote 70

Economic voter intimidation cases, especially in the North, rarely involved violence even as mild as that which broke out between Kelley and Smith. National newspapers seized on this lack of violence to dismiss the significance of economic coercion, often with shocking flippancy. In December 1878, the New York Times reported on intimidation in the mill towns of Massachusetts with caustic sarcasm. Quoting witness testimony before the Senate committee, the Times noted that “the employees of the Manchaug Mills were actually ‘watched’ at the polls … they had been watched, which was truly dreadful.”Footnote 71 Lest readers think that the paper was taking the threat of economic voter intimidation seriously, the article remarked that no one “had heard of a Democratic voter being taken into the mill cellar and flogged, nor of employees being warned to leave the county on pain of death.”Footnote 72 Months later, the Times repeated its dismissal of the coercive nature of economic voter intimidation, this time comparing electoral coercion in Massachusetts to “the terrors of the South Carolina shotgun and the lashes of Louisiana.”Footnote 73 Tongue firmly in cheek, the paper asked whether Butler-voting mill workers had been “strangled in their own looms,” or lured “into the wilds of Boston Common, and brutally drowned in the historic frog-pond.” The forms of coercion practiced in these company towns—threatening families, denying equal political access, and firing recalcitrant workers—were an object of derision to the Times, which dismissed these “various methods” by putting the phrase in sarcastic scare quotes.Footnote 74 Similarly, the Boston Herald noted seemingly without alarm in 1878 that there would probably be “a good deal of bulldozing … of a civilized type,” meaning nonviolent coercion, during the upcoming election. The paper emphasized that employers would take care to ensure that the election would be “managed with decorum, adorned by noble sentiments” and without overt threats of violence.Footnote 75 In company towns like Manchaug and Douglas, subtle threats were perhaps all that was required to unduly influence a voter. Dependent as they were on their bosses for employment and housing, mill workers were in no position to deny even the “civilized” methods of the Massachusetts bulldozers.

Conclusion

Economic voter intimidation posed a real threat to American democracy in the 1870s, ’80s, and ’90s. As employers intimidated employees in workplaces across the country, politicians and reform and labor advocates grew terrified that white workingmen could be vulnerable to the same methods of coercion that African Americans confronted in the South. They worried that if white wage-working voters lost their economic and political independence, then the radical predictions of socialists and anarchists that industrial capitalism and mass democracy could not peacefully coexist would be confirmed. The omnipresence of discharge threats and election day observation in states across the nation gave the seemingly abstract “labor question” real form and serious consequences. The challenge that wage-labor capitalism posed to democracy could not be easily dismissed when employers were exploiting their workers’ economic dependence to control their votes in workplaces of all kinds and in every region of the country.

The massive increase in workplace coercion produced an unknowable number of illegitimate election results, contributing to the widespread sense that Gilded Age political culture was pervaded with corruption. Labor advocates and municipal reformers responded by seeking to disrupt the second half of the coercion equation—they blocked employers’ ability to observe their employees at the polls by enacting secret ballot laws. Beginning with Massachusetts in 1888, states in the North and West turned to the secret ballot in large measure to stop economic voter intimidation. Southern states, however, lagged far behind in their passage of secret ballot laws, in part because southern politicians did not perceive the economic coercion of African American voters to be an existential threat to American democracy.Footnote 76

The most dramatic demonstration of how pervasive the crisis of economic voter intimidation was in the Gilded Age emerged from the Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York. In 1891, barely a year after the state passed its first secret ballot law, a prisoner asked a professor teaching a course in practical ethics “as to the culpability of a voter who yields to the dictation of his employer as to how he shall cast his ballot.” The prisoner did not think that “a man should be blamed for sacrificing his political opinion to keep his place of employment.” The unnamed prisoner knew the kinds of pressures that a boss could levy against a desperate worker, but he was unsure whether the fault lay with the employer or the employee. The professor acknowledged the relevance of the question: “there was doubtless a great deal of undue influence exerted by employers over those who were dependent upon them for their bread and butter.” One prisoner disagreed, insisting that “yielding to such dictation was only another form of selling one’s vote” and that the employee was at fault for his greed. Others claimed that sacrificing their votes for their jobs undermined their manliness. But several prisoners argued that the “choice between voting as their employers said and being turned out” was not much of a choice at all. Workingmen in the Gilded Age were economically precarious and had little legal protection at the polls. Discharge could plunge them into poverty, homelessness, and eventually perhaps prison. When their bosses threatened to fire a workingman if he did not vote as directed, one prisoner reasoned, “what else could a man do?”Footnote 77