On a visit to New York in May 1897, Elizabeth Howell Smith (Mrs. Edward Laban Smith) of Cripple Creek, Colorado, spoke openly of her opposition to equal suffrage in her home state. She hoped her experience in Colorado would sway her sisters in New York to heed her warnings and refrain from demanding suffrage. “In no section on this broad continent are women so hampered in attempting public affairs as in the West, and in no other sections do the lines of life fall so crooked to the housewife,” she lamented. “I vote because the right of suffrage has been thrust on me, and I feel to shirk it would be like shirking any other serious duty,” Smith asserted, claiming others like her felt the same. “Hearing this so repeatedly, you get the idea that even those who do vote do it under protest.”Footnote 1 Regardless, they voted. Smith's experience as a voting anti-suffragist was not unique to her. Although they had waged extensive campaigns against equal suffrage, once it passed in their states, anti-suffragists in the American West begrudgingly exercised their right to vote in hopes of neutralizing the influence of “immoral” women. As equal suffrage expanded, the Western anti-suffragist strategy became the strategy of anti-suffragists everywhere and would eventually become the foundation for conservative women's activism well into the twentieth century.

In the limited historiography of the American anti-suffrage movement, scholars have largely focused on the leadership, strategy, and rhetoric of anti-suffragists in the East. Each historian has found a new way to contribute to our understanding of the movement by helping us to learn who the anti-suffragists were, where they came from, and what shaped their ideas, largely by concentrating on one particular state organization or their rhetorical styles.Footnote 2 However, as suffrage scholars like Rebecca Mead, Sara Egge, and others have demonstrated, region matters for the history of the suffrage movement and so it should in the study of the anti-suffrage activists.Footnote 3 Mead's work is especially important as it was the first to examine the women's suffrage movement in detail in the American West. And although scholars have recognized the importance of the West in suffrage activism, few have made the connection between the American West and the anti-suffrage movement.

The most recent history of anti-suffrage activists, Susan Goodier's 2013 No Votes for Women, traces the history of the New York Anti-Suffrage Association, the predecessor of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS). Goodier correctly argues that “New York anti-suffragists had dominated the suffrage battle at the national level even before they organized” the national alliance in 1911.Footnote 4 She also argues that the NAOWS was, indeed, a reactionary organization when, in response to the 1917 New York referendum, they encouraged their women members “to vote as the state's ‘anti-socialist, anti-radical force.’”Footnote 5 However, the implication in her conclusion is that the NAOWS had waited six years to promote local electoral activism. Because she focuses on New York anti-suffragists, Goodier misses that, in the American West, anti-suffragists had long—albeit, unhappily—accepted their new responsibilities as voters.

Anti-suffrage scholars have examined the rhetoric of anti-suffragists and their ideological opposition to suffrage, but have done little to connect that rhetoric to their post-suffrage strategy of electoral activism. For example, in Splintered Sisterhood, Susan Marshall asks why anti-suffragism existed as opposed to how anti-suffragists operated. Marshall concludes, “Progressive reforms such as woman suffrage would further diminish its [the conservative urban elite] power and endanger particularly women's status as political appointees, society volunteers, and custodians of propriety.”Footnote 6 In “Better Citizens Without the Ballot,” Manuela Thurner argues that female anti-suffragists actually and “ideologically ventured considerably beyond the domestic sphere in their effort to forestall women's enfranchisement, portraying themselves as very much in line with and in favor of turn-of-the-century progressive reform and female activism.”Footnote 7

In this essay, I address the ideology and the reactionary strategy of anti-suffragism after suffrage laws were passed. The evolution of these women from anti-suffragist to suffragist began as a direct result of suffrage success in the American West. This article explores three episodes of anti-suffrage activism that coalesced around the passage of suffrage in western states: Colorado (1893), California (1911), and Oklahoma (1918). They represent important moments in the history of western suffrage prior to the ratification of the national amendment in 1920, but they also represent pivotal moments in the development of the anti-suffrage movement broadly. Colorado's equal suffrage amendment in 1893 inspired New York anti-suffragists to formally organize their state organization, the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage in 1895.Footnote 8 Once Colorado voters had granted women equal suffrage, anti-suffragists pointed to it as an example of all the failures of woman suffrage, hoping they could prevent other states from passing equal suffrage amendments. When California passed equal suffrage in 1911, it caused a paradigm shift for the anti-suffragist movement. Local anti-suffragists encouraged like-minded women to vote, regardless of their stance on the vote. Furthermore, California's suffrage amendment resulted in the establishment of the national anti-suffrage organization. Oklahoma signified a different moment for anti-suffragists. By the time Oklahoma became an equal suffrage state in 1918, even New York, with its major anti-suffrage organizations, had become an equal suffrage state. Anti-suffragists faced new challenges in their fight to preserve their ideal America, including the perceived threat of feminism and their fear of the ratification of a national amendment. Anti-suffragists, therefore, were becoming suffragists in their own right. Indeed, by then, they were voting, registering other voters, and even running for office. This is best exemplified when, in 1921, Oklahoma voters elected Alice Robertson, an anti-suffragist, to be their first congresswoman. The anti-suffragist strategy of self-preservation had transitioned from statewide efforts to the national movement and from an explicitly anti-suffrage to an anti-feminist stance.

Colorado

In the mid-nineteenth century, when the Wyoming and Utah territorial legislatures passed equal suffrage measures, anti-suffragists did not believe it was necessary to panic or organize extensive counter campaigns. After all, these were territories with relatively small populations, and they could argue it did not necessarily represent the will of the people. Instead, anti-suffragists still held out hope that they could be more influential than territorial legislatures. However, when Colorado became an equal suffrage state through a referendum in 1893, it proved that the suffrage movement was, at least in the West, gaining momentum. The next year, women in New York formally organized in an effort to halt this momentum, gathering “12,000 names of women over 21” who agreed to stand united against women's suffrage.Footnote 9 By April 1895, the official anti-suffrage movement was born, most notably the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, which was the largest anti-suffragist association in the country.Footnote 10

While they organized against suffrage in the East, anti-suffragists in the newest western suffrage state had a different and more difficult choice to make. For instance, in 1893, Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer was living in Colorado. The former New York socialite and one of the nation's leading critics of architecture had achieved some fame after being hired to write about The World's Columbian Exposition for Century magazine.Footnote 11 Her editorial resulted in new writing projects, all leading her further west, where she landed in the newly equal suffrage state of Colorado. Soon after arriving, she had her first voting experience. Though she did not approve of woman suffrage, Van Rensselaer voted, “because it is the law.”Footnote 12 She went so far as to vote Republican, even though during her time in New York, she supported the Democrats and was friends with President and Mrs. Cleveland. But in Colorado, the choice was primarily between Republicans and Populists, and as a result, she chose to support the Republicans, believing—as most anti-suffragists did—that Populists represented a more radical political agenda. Although anti-suffragists feared that only the “bad” women would vote, Van Rensselaer's sense of duty proved otherwise. Still, she used her experience to malign women's voting.

She described her voting experience as “very silly.” She was able to register without anyone confirming her identity or even being asked how long she had lived in the state. It seemed to confirm to her the disorder of woman suffrage. Upon hearing that wealthy women in her home state of New York were entertaining the idea of demanding woman suffrage, Van Rensselaer decided to write a series of anti-suffrage essays in an effort to convince them that it was not worth their time or efforts. In May 1894, she submitted six essays to the New York World, and they would later be published as an influential pamphlet by the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage entitled Should We Ask for the Suffrage? Footnote 13 “The women of Colorado were granted the suffrage before they really wanted it,” she began her first essay, “and just now it seems to some that the women of New York need to be careful lest a similar experience be theirs as well.”Footnote 14 Indeed, she used her own experiences in Colorado to give her authority on the subject.

Van Rensselaer, who later held office within the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage,Footnote 15 made what would become typical anti-suffragist arguments against woman suffrage. The woman's vote was unnecessary, she argued, and it was not what the country's founding fathers had wanted for the citizenry. Most importantly, women had to keep their homes while men had to support those homes, and voting undermined these clear gender roles. These gender roles were key to the preservation of the family. She acknowledged that due to exceptional circumstances, some women had to assume part of a man's work of protecting the home. “But this is a misfortune, not an opportunity,” she concluded.Footnote 16 While this served as a summation for how she felt about suffrage, it certainly did not stop her from participating in it, and that is significant. As she wrote to her friend and Century editor Richard Gilder, her son pressured her to vote “as a revenge for the way I have talked good citizenship to him ever since he was born!”Footnote 17 It was her sense duty to the law and her obligation as a mother that sent her to the polling place.

In what many considered the summation of the anti-suffragist platform, Helen Kendrick Johnson, another New York anti-suffragist, wrote extensively about the failures of woman suffrage in her book, Woman and the Republic: A Survey of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States and a Discussion of the Claims and Arguments of its Foremost Advocates (1897). Johnson examined states and territories with woman suffrage and used her findings to argue that woman suffrage failed democracies. She, too, used women's experiences in Colorado to make her point. “A friend said to me some time ago,” she wrote, “‘You know that I have been a Suffragist. I am most thoroughly converted. I have been three months in Colorado. It is enough to cure anyone.’”Footnote 18 In her discussion of the Centennial State, Johnson tied woman suffrage with the Populist movement and declared, “Neither that movement nor its results present triumphant democracy.”Footnote 19 In other words, woman suffrage was connected to radical politics and was a failure.

It was certainly not the entire West that was plagued by radicalism. As Johnson noted in the previous presidential election, Californians (living in a male suffrage state) had the sound mind to vote “for authority against anarchy” while Colorado voted “against sound money and sound Americanism.”Footnote 20 However, Johnson criticized Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho—all with woman suffrage at that point—or their willingness to experiment with Populist ideas, such as the equal coinage of silver. The Populist movement challenged the principles of American democracy, as did women's suffrage. And, she concluded, although good women like Mariana Van Rensselaer could and did vote, there simply was not enough of these good women to prevent this kind of radical political behavior from happening.

For the next two decades, anti-suffragists followed Van Rensselaer and Johnson and continued to point to Colorado as the ultimate example of how woman suffrage was politically and socially damaging. As more state anti-suffrage organizations were established throughout the country, anti-suffragists organized campaigns dedicated to revealing the failures of suffrage. They published pamphlets, wrote editorials, delivered speeches, and even testified before Congress warning that equal suffrage perverted not only government but also the family and gender roles. Women were suddenly masculine, and men were feminine—lacking an awareness of their gender identity. According to one anti-suffragist who testified before Congress in 1909, as she “passed from polling place to polling place in the city of Denver … there was an utter absence of sex consciousness on the part of men and women.”Footnote 21 This corruption of gender roles allowed for women of all classes, races, and backgrounds to participate in the political process, they warned. A few years later, anti-suffragist Margaret Robinson of Massachusetts wrote to the New York Times about Colorado's equal suffrage laws, complaining that “woman suffrage enables the undesirable element, which always gets out its vote, to gain control.”Footnote 22

Critics of equal suffrage in Colorado believed there were two victims of equal suffrage: the home and the state. One anti-suffragist argued, in a 1912 article entitled “Failure of Suffrage in CO; Why it Fails,” that equal suffrage did not create laws “that particularly or notably elevated the race or enhanced the conditions of living in Colorado.”Footnote 23 From the home, women carried the kind of influence necessary to maintain the integrity and morality of American society without having to fully enter it. Women suffragists were all “misguided” in believing they could leave their children in the morning “for what they thought was the uplift of the race, while the race itself, represented by their children at home, was being looked after in an indifferent way by proxy.” The anonymous writer also claimed that despite having woman suffrage for over a decade, Colorado had done nothing to end prostitution, claiming, “The social evil has not disappeared.” Juvenile delinquency and divorce rates were on the rise. Furthermore, voting rights “alienated many good women from the work of the home and the pleasures and responsibilities of wives and mothers.”Footnote 24 Colorado stood as a warning to women.

California

Motivated by their victory in Colorado, suffragists pushed for the vote in other western states. They successfully campaigned for women suffrage in Idaho in 1896, but they had also set their sights on California. Its large population would make for a significant victory for the suffrage movement. But after an embarrassing defeat in 1896,Footnote 25 as Susan Englander in California Women and Politics reminds us, suffragists struggled to start again. “The state body constructed during the [1896] campaign wasted away to a mere skeleton.”Footnote 26 However, California suffragists soon found themselves with new local leaders: clubwomen.Footnote 27 In the early 1900s, clubwomen were key to progressive reforms in California, but class issues led them to conflict with members of unions and the working class, the same divide that cost the suffragists their victory in 1896. It could not happen again in 1911.Footnote 28 But as Englander points out, those differences persisted, regardless of numerous attempts to bridge the gap. Instead of unifying, these groups settled for a fragile coalition to support suffrage, even if for very different reasons.Footnote 29

In editorials and public speeches, anti-suffragists hoped to convince California's male voters that woman suffrage failed elsewhere. Among them was Los Angeles Times columnist and a founding member of the Southern California Woman's Press Club, Dora Oliphant Coe. Coe emerged as a leading voice in the California anti-suffragist movement, but her columns also appeared in newspapers across the country. Like other anti-suffragists, Coe believed woman suffrage was anti-democratic and an unnecessary burden. In a speech to the Printers Board of Trade in July 1911, she delivered a “brilliant address” in which she “pleaded with the sixty-five men present not to enforce the responsibility of the franchise upon the members of her sex.”Footnote 30 According to Coe, California women could accomplish more “in matters of charity, sanitation, and needed forms … simply as women than they can as citizens.”Footnote 31 Furthermore, the cause of equality was a challenge to American identity. “I wish to say also that most of the women who are clamoring equal rights are very unpatriotic.”Footnote 32 She continued, “I do not only consider these women undeserving of the franchise, but I think that any man who would countenance such a sentiment is unworthy to be called a true American.”Footnote 33

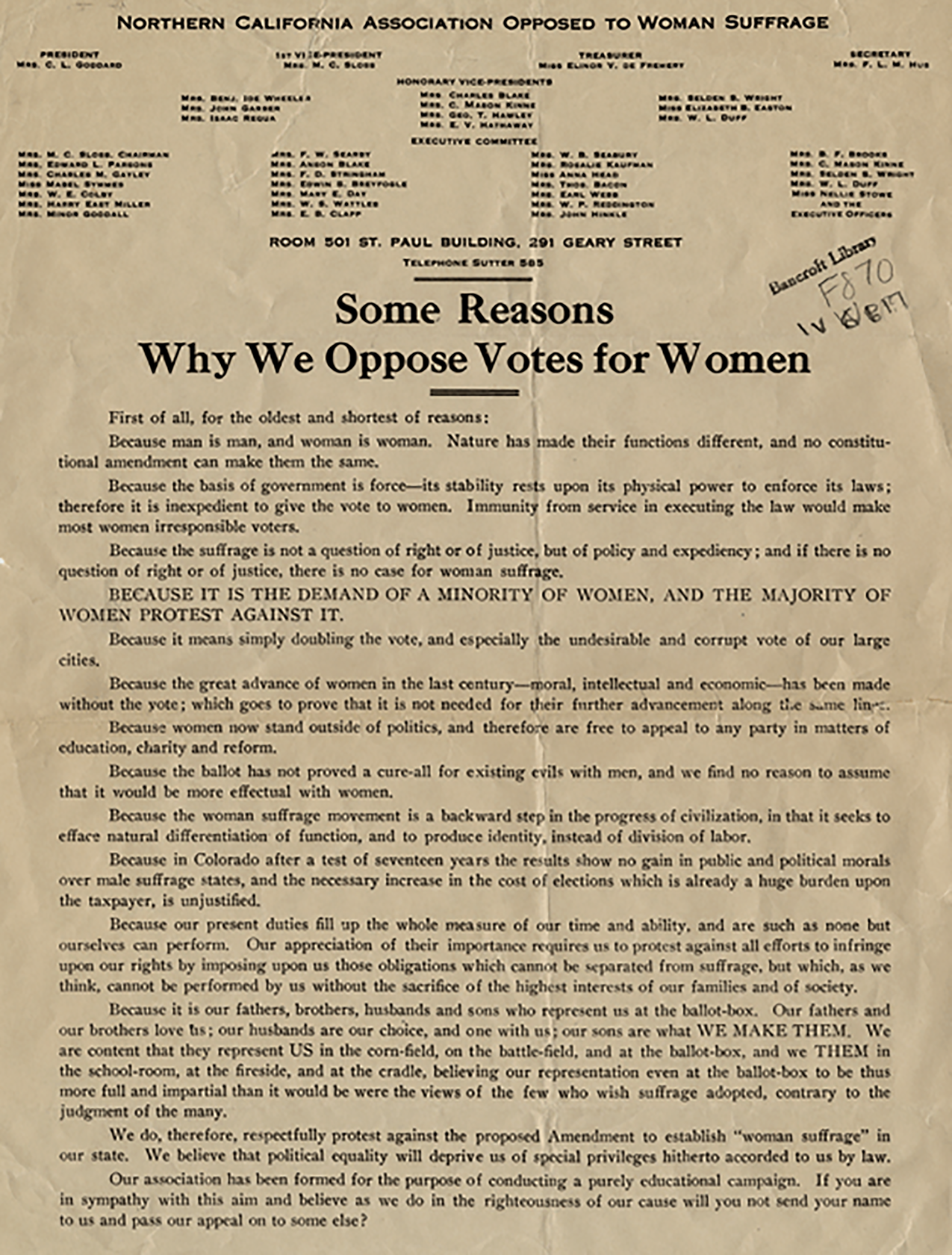

Coe used the anti-suffrage strategy of highlighting the supposed failures and the unnecessity of women's suffrage in other western suffrage states as reasons why California should reject the equal suffrage referenda. She disagreed with suffragists who asserted that women's votes would purify politics and argued that politics were already working. “An anti-suffragist,” Coe reminded her readers, “is one who believes that the present regulations of the franchise are better than the proposed change would be.” According to Coe, women and children were already better protected in California where only men voted than anywhere else in the United States. This included the equal suffrage state of Colorado, of course, “where women have voted for eighteen years.” The men of California had passed laws ensuring that factories had sanitary conditions, she argued, but “no such restrictions exist in Colorado.” Furthermore, “the punishment for the mistreatment of young girls in California is five years, but only two in Colorado.”Footnote 34 Why then would California need equal suffrage, when clearly it had done so much already without it, she asked readers? (fig. 1).

Figure 1. The Northern California Association to Woman Suffrage, led entirely by women, used Colorado as a reason to oppose woman suffrage because “after a test of seventeen years the results show no gain in public and political morals over male suffrage states.”

“Some Reasons Why We Oppose Votes for Women,” A Centennial Celebration: California Women and the Vote, Pf F870.W6P17, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

California anti-suffragists received support from women outside of the state. Mrs. William Force Scott, chairman of the New York Anti-Suffrage Association Publicity Committee, traveled to the West Coast to help with the campaign. As she described it, she had been forced in an “anomalous position” of leaving her home and traveling 3,000 miles “to appear in public in order to convince people that a woman should not leave her home, should not go abroad on political missions, and should not make herself conspicuous in public.” At the end of this article, however, readers learn that Scott had appeared “before every session of her State's Legislature for the last fourteen years”Footnote 35 to oppose woman suffrage. Scott's cross-country trip was not an anomaly. It was another example of anti-suffrage activism.

Scott issued Californians the typical anti-suffragist warnings: suffrage had not resolved any issues where it had been passed in other areas in the West. Instead, suffrage had made things much worse. “Woman suffrage in Colorado,” she declared, “amounts to a curious obsession. The men yield to the women rather than fight with them, because their [the women's] methods are despicable.” She countered suffrage arguments that women would improve politics by claiming that the “social evil,” by which she meant prostitution, not only persisted in Colorado, but—it was “as bad as it is in any city in the United States.” Indeed, Scott hoped “the men of the West will think well before they sacrifice the East … and before they commit future generations to a gigantic blunder from which retreat will be so difficult a wait until suffrage has made good.” Scott's implication here is crucial in our understanding of why she traveled 3,000 miles in the first place: to lose the West—particularly California—to equal suffrage meant that the East was increasingly vulnerable.

To the dismay of anti-suffragists, the men of California approved equal suffrage in October 1911. Anti-suffragists once again had to face the reality that suffrage would not simply disappear. Their movement, however, could. After all, the largest state in the West and one of the largest in the country had just added thousands of women of different races and classes to its voter rolls. California anti-suffragists, then, considered becoming their own version of voters. Anti-suffragists at the grassroots level in suffrage states could either choose to remain observers while other women made political decisions, or they could vote and encourage other women who shared their values to vote as well. National anti-suffragist leaders responded by increasing their efforts to stop suffrage momentum. In December 1911, Josephine Jewell Dodge, president of the NYSAOWS, resigned her position to become the first president of the newly organized National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. The organization began to publish a national newsletter, The Woman Patriot.Footnote 36

However reluctant to accept this new responsibility, California anti-suffragists like Dora Coe believed that women like her taking up the vote was the only way to preserve the traditional American family. After all, as Coe warned, “The amendment giving to women the right to vote does not specify that only the intelligent, moral woman shall have the ballot.”Footnote 37 She worried that with suffrage, all women—educated and uneducated, wealthy and poor, white and nonwhite—would have the same influence at the polling place. This was not entirely true, as there were restrictions preventing all women from voting.Footnote 38 However, women's suffrage implied that non-white, working class women shared a status of political equality with wealthy white women. It was worrying enough that “all classes of men” had the right to vote; it was still more troubling that the “wife of the uneducated laborer” would have the same opportunity.Footnote 39

Voting was certainly not what Coe and other California anti-suffragists wanted, although suffragists reported that they had “converted.” In a statement quoted in a special anti-suffrage section of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle edited by Josephine Dodge, Coe responded forcefully that this was not the case. Coe expressed her frustration at her political choice, writing: “I am more opposed to woman suffrage than I ever was I voted, but I told them as I handed my ballot that that was the last vote I would cast until I was given a chance to vote against woman suffrage.”Footnote 40 Despite her exasperation with equal suffrage, she continued to vote. In fact, she began to demand that other conservative women do the same.

Although the new responsibility was not welcome, she conceded, it was their burden to bear. In a column aptly titled “And Now What?,” Coe insisted that conservative women must now vote in every election to, at the very least, counteract “the other powers of evil.”Footnote 41 “Since the women of California have been corralled by politics and no longer may roam at will over the free hills,” Coe begrudgingly wrote, “now every right-minded, every conscientious, every patriotic woman must get into the harness and go to work.”Footnote 42 She did not believe that there were “more bad women than good”; however, she feared that woman suffrage would bring a “toxin, which is poisoning the roots of State life in each woman suffrage commonwealth.” This toxin of equal rights could only be negated by anti-suffragists who—even with great reluctance—voted “to be loyal to her State and forget her personal feelings.”Footnote 43 If they wanted to protect their values and preserve their country, they had no choice. “It is no longer a question of ‘I want to vote’ or ‘I don't want to vote,’” Dora Coe wrote. “It is simply and emphatically, ‘I must vote.’”Footnote 44

From Anti-Suffrage to Anti-Feminist

As suffrage expanded across the country anti-suffragists feared the rise of radical ideologies, such as socialism, communism, and a new threat to the twentieth century: feminism. “In its [feminism] early uses,” historian Nancy Cott reminds us, “the word had shock value and an encompassing yet unspecified referentiality.”Footnote 45 As the term became more popular, self-identifying feminists “welcomed the idea of radical and irreverent behavior.”Footnote 46 Cott explains, “As a movement of consciousness, Feminism intended to transform the ideas of submission and femininity that had been inculcated in women; the suffrage movement provided a ready vehicle for propagating this vision with imagination and ingenuity.”Footnote 47 As feminists blatantly challenged the traditional roles of women—anti-suffragists felt they had no choice but to get involved to save social order.

From 1893 to 1918, state after state—seventeen in total and most in the American West—passed full equal suffrage laws,Footnote 48 including one that jarred leaders of the national anti-suffrage movement. In 1917, the state of New York became an equal suffrage state, the largest in the East and a tremendous victory for the suffrage movement. “They [suffragists] were well organized and highly proficient,” writes Susan Goodier, “which allowed them to make the ‘most of their ‘patriotic’ contributions in public meetings, parades, and press releases.”Footnote 49 These patriotic contributions during the war effort won the support of President Woodrow Wilson, who then urged New Yorkers to pass equal suffrage measures. Soon after, the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage met for their annual convention where Alice Chittenden “encouraged anti-suffragists ‘to line up with the several political parties.’”Footnote 50

Some anti-suffragists agreed and formed the Voters Anti-Suffrage Party. Former antis like Mary Guthrie Kilbreth emerged as clear leaders in the movement. Though Kilbreth never married, she believed, as did many other anti-suffragists, that suffragists were fighting to disrupt the stability of the American family.Footnote 51 Active with anti-suffragists across New York, Kilbreth served as the third president of the NAOWS and the editor of The Woman Patriot.Footnote 52 After the state of New York passed equal suffrage in 1917, the NAOWS and the newly formed Voters’ Anti-Suffrage Party moved their headquarters into one building; their two mottos were painted on opposite walls. One motto read, “Politics are bad for women and women are bad for politics.” But on the other side of the room, the motto included instructions for voter registration. Kilbreth led both organizations.Footnote 53

Although the vote had been “thrust” upon them, anti-suffragists used the political tool they resented as a means to protect their nation. There was far too much at stake not to vote. “Anti-Suffrage,” wrote Frances Benson, secretary of the New York Anti-Suffrage Association, “has always meant anti-feminism, anti-Socialism, anti-radicalism, anti-Bolshevism, anti-internationalism, though the casually informed are but just finding it out.”Footnote 54 Even after ratification of the Susan B. Anthony amendment in August 1920, anti-suffragists were convinced their fight had just begun.Footnote 55 Feminism, as one pointed out, was a particularly troubling ideology for anti-suffragists, as it “is based on the destruction of the family.”Footnote 56 As a threat to the cornerstone of American society, feminism was seen as a gateway to the destruction of the country as a whole.

Still, anti-suffragists continued to fight back against the amendment, demanding congressional hearings and even supporting a lawsuit that challenged the constitutionality of the Nineteenth Amendment. In one particular instance, a Mrs. George Arnold Frick of Baltimore led a delegation of anti-suffragists to Congress in hopes of testifying before the Resolution Committee about how they believed a national suffrage amendment was a violation of states’ rights. However, their request was denied. “Everybody else was given a hearing, including even Negroes and Chinamen and Koreans—but the hearing was refused by Carter Glass on the grounds that … it was ‘against the policy of the party to hear the anti-suffragists.’”Footnote 57 When Congress would not listen, they placed their hopes in the Supreme Court justices. “But if the Supreme Court decides that there is no Nineteenth Amendment, at least ninety per cent of the seasoned politicians in both parties will heave a great sigh of relief,” one anti-suffragist wrote.Footnote 58 And when the court upheld the amendment, anti-suffragists had no choice but to accept it and refigure their political purpose.

Many former antis followed the lead of their sisters from suffrage states claiming that as protectors of the home and nation, they had no choice but to embrace a more public, political role that included both voting and even running for office. Their actions were essential to save the society. “It will be the duty of anti-suffragists,” one writer argued in The Woman Patriot, “to see that efforts to make double suffrage a complete success by transforming both sexes into weak neaters [sic] will be thwarted.”Footnote 59 After all, the writer continued, equal suffrage was a “culmination of decadence which has been steadily indicated by the race suicide, divorce and breakup of the home and by federalism.”Footnote 60 Once again the precedent for anti-suffragist strategy came from a western state, this time, Oklahoma.

Oklahoma

For fifty years, Edith Cherry Johnson worked as the society editor and weekly columnist for the Daily Oklahoman, where she regularly cautioned her readers to protect their families and their homes. Prior to equal suffrage, Johnson believed a woman's sole responsibility was to see to the needs of her husband and family.Footnote 61 “It makes little difference,” Johnson wrote, “what a big figure you cut in the world, if you cut a poor one at home.”Footnote 62 In extenuating circumstances such as war, Johnson urged her readers to prioritize the needs of the country over their personal desires for such things as equal suffrage. She castigated the suffragists: “It makes us feel that too many women are losing a proper sense of values, if they ever had it, that they are supremely selfish in their aims.”Footnote 63 That women would still demand equal rights while the world was at war baffled Johnson, but it also cemented her feelings that feminism and political activity were self-serving and radical. Feminists might be happier elsewhere, Johnson suggested. “Women seem to have found it in Russia where they have succeeded, for the time being at least, in repudiating their ancient responsibilities.”Footnote 64

Two months after Oklahoma voters passed equal suffrage in November 1918, Edith Johnson confessed her continued doubts about women's suffrage to her readers, but she also admitted the possibilities of the vote. “I have feared that women would not take more trouble to find out for whom they were voting than have the men.”Footnote 65 Like other anti-suffragists, she expressed a fear that women would lose their virtue and femininity if they became involved in politics. What if they became corrupted? But what if they chose not to vote, thereby forfeiting a “good” vote, or chose to not educate themselves and voted ignorant of the issues? Yet, whether Johnson supported it or not, equal suffrage was now a reality in Oklahoma. She, like so many other anti-suffragists, would have to adjust. And in doing so, she saw the potential for positive results.

But if [women] will now accept the obligation of citizenship—it is that rather than a privilege—in the spirit that they have promised, if they will turn from trivialities to the serious and intelligent consideration of the numerous political and social problems that confront us, then I will say, let women have generous part in the administration of government.Footnote 66

As long as they resisted the temptation for politics to corrupt them, Johnson posited, voting women could elevate government. However, if voting women forgot their “lady-hood,” they risked degrading themselves “in the estimation of men.”Footnote 67

By remaining focused on the task assigned to them, continued Johnson in a January 1919 editorial, women could be the moral leaders of American politics. Their femininity and even their motherhood would be assets to their insights as voters. “The woman who has the mental and moral balance, the unselfish impulse and the keen sense of duty to make a good wife and mother,” Johnson wrote, “is the very woman who ought to vote. …”Footnote 68 It was Johnson's hope that such women would perform their “sacred” duties to “purify politics.” After all, she claimed, “former opponents of woman suffrage do not want to see their judgment vindicated.”Footnote 69 This particular former opponent of woman suffrage went on to say that a woman who could vote but did not was “a slacker. She is not a good citizen or a patriot.”Footnote 70

Unlike Edith Cherry Johnson, Alice Robertson, the vice president of the Oklahoma Anti-Suffrage Association, could not count herself among the anti-suffragists who were quick to get behind the equal suffrage momentum in 1918. Robertson had lived a rather public life, owning a popular cafeteria in her hometown of Muskogee, Oklahoma, and was once appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt to serve as the Postmaster General for Muskogee. But when local Republican leaders approached her to run for Congress in 1920, she did not believe her popularity was enough to win in a Democratic stronghold. Her fear was not entirely baseless. In 1916, before Oklahoma women could even vote, local Republicans had nominated Robertson for county superintendent of public instruction, and she had lost. Furthermore, as a woman who once actively campaigned against women's political activity, running for public office would seem to be against everything for which Robertson stood. Still, “the men have thrust the vote on us and now I am going to see whether they mean it,” Robertson declared.Footnote 71

While she argued that the political arena was no place for women, Robertson, like most anti-suffragists, seemed quite familiar with the current political climate. She understood that in order to win the election, she would need to present herself in a unique way that would draw attention away from her opponent, the longtime incumbent William N. Hastings. She took advantage of the classified section in local newspapers to place campaign ads while simultaneously promoting her cafeteria. “We do not find ‘business as usual,’ but better than usual,” one ad declared, “and we wonder vaguely if the increase is caused by a pardonable curiosity to see the one and only woman candidate for Congress.”Footnote 72 Rather than make speeches or campaign around town, Robertson “would sit down with voters at their table … and talk politics” in the domestic sphere.Footnote 73 This strategy also played to anti-suffragists’ idea of women's special social role.

In November 1920, just three months after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, Alice Robertson became the first woman elected to Congress from Oklahoma (one of the three women to serve in the institution that term).Footnote 74 Her victory drew applause from conservative women locally and nationally. While they resented the political activism of suffragists, members of the NAOWS praised Robertson's election as “a personal tribute to an individual, not an affair of woman's suffrage.”Footnote 75 They were comforted by their belief that politically “extreme” women would not vote for someone like Robertson. As Daily Oklahoman columnist Edith Johnson approvingly wrote, Robertson would not be a “much made-over and flattered woman” who was too concerned about “getting her hand kissed” as she suggested the first woman elected to Congress, Jeannette Rankin of Montana had.Footnote 76 Moreover, at sixty-six years old, Robertson was at an age when “passions have cooled,” therefore allowing her to “bring to her work pure reason, a heart whose interests will be undivided and a nature undisturbed by romantic” interests.Footnote 77

Robertson's election also caused anti-suffragists to wonder if perhaps more conservative women should run for office. According to some anti-suffragists, Congressmen were not willing to challenge women. “It may be better to have a real woman or two in the place of the sort of males who are ‘afraid of women,’” wrote one anti-suffragist.Footnote 78 Robertson was something of an ideal politically active woman for anti-suffragists. Conservative and unwilling to challenge men's authority, Robertson occupied office as the “conscience keeper” of the House of Representatives, just as women were “the conscience keepers and conscience quickeners” for their families.Footnote 79 Robertson represented to anti-suffragists a “real woman,” holding “‘a man's job’ recently held down by hundreds of women-ruled politicians.”Footnote 80

Indeed, Robertson took her role as “conscience keeper” very seriously. She hired Benjamin E. Cook, a war veteran from Muskogee, to work as her secretary because “men like to talk things over with other men.”Footnote 81 Such choices helped define Robertson's career as a congresswoman. She never politicked for or even created her own political policies. Rather, she believed her responsibility was to intervene when the American way of life was under attack from threats like socialism and feminism, while simultaneously holding her male colleagues accountable to a high standard. “Miss Alice does her own thinking and follows her own convictions,” one anti-suffragist wrote.Footnote 82 They believed that this discouraged feminists from seeing Robertson as a true representative for women's issues in Congress, in the sense that she would not be an advocate for a feminist manifesto. Nothing demonstrated this better than her vote against the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Bill.

In July 1921, Texas Senator Morris Sheppard (D) and Iowa Congressman Horace Towner (R) sponsored a maternity bill intended to reduce infant and maternal mortality. The Sheppard-Towner Maternity Bill also served as a political ploy. Historian Nancy Woloch describes the bill as “an expensive measure … enacted by an overwhelming majority of congressmen, all anxious to curry favor with women constituents.” It proposed to use federal funds to match states’ funds for prenatal and child health clinics as well as information on nutrition and hygiene, midwife training, and visiting nurses for pregnant women and new mothers. Aid would be focused on rural areas because most urban centers already had such welfare agencies.Footnote 83

The bill proved attractive even to typically conservative senators and congressmen, with the exception of one: “Miss Alice” of Oklahoma. Robertson described the bill as “paternalistic,” claiming it would “overthrow the American family” and was “Bolshevistic in some of its features.”Footnote 84 More importantly, Robertson believed that the women who championed the bill were trying to avoid the responsibility of motherhood and manipulate American society to carry the responsibility instead. Women, according to Robertson, were taking advantage of men's ignorance of pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood to accomplish their goal.

Leaders of the National Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage agreed. They argued that the Sheppard-Towner Maternity Bill was a feminist attempt to “control … the nation's mothers and babies.”Footnote 85 The one person they could count as an ally was a woman who served in Congress. Alice Robertson and other anti-suffragists met with President Warren G. Harding in the White House to discuss their opposition to the Maternity Bill, as well as other bills they opposed. NAOWS president Mary Kilbreth claimed their purpose in meeting with Harding was “to present him certain facts about this left wing legislation which is so protected by propaganda that we were advised to go to the President direct with our evidence.”Footnote 86 Kilbreth had once declared that politics was no place for women, but she was willing to enter the fray when she believed it was necessary. Despite the efforts of Robertson and the NAOWS, the bill passed.

The West as a Catalyst

The anti-suffragist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries organized and responded to the successes of the woman suffrage movement that occurred in the American West. The largest state organization, the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, was established in 1894, just after Colorado became an equal suffrage state. Using Colorado to demonstrate the failure of woman suffrage, anti-suffragists believed they could successfully stop suffrage momentum and felt this strategy was vindicated after California rejected equal suffrage measures in 1896.

However, when California passed woman suffrage in October 1911, anti-suffragists at the local level faced a new dilemma: either they could resist the vote or they could embrace it. Resistance, they believed, risked allowing political radicalism and immorality to dominate and destroy their nation. But if they embraced it, they would not only protect their country, they could lead it. The latter model is exactly what they would find in Alice Robertson from Oklahoma.

Still, the anti-suffragist response to the West was not strictly local. State chapters across the country were created as a result of what happened in the West. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was established because of suffrage in the West. The expansion of the anti-suffrage movement was closely connected to the success of western suffrage. Anti-suffragist strategy and rhetoric relied on how suffrage worked in the West, or at least anti-suffrage perceptions of it. In other words, women's suffrage in the West served as a catalyst for the anti-suffragist movement.

This particular chapter of women's history also served as the predecessor to the more successful conservative women's movement: anti-feminism. Embracing the right to vote—even if begrudgingly—permitted conservative women in the mid-twentieth century to use the public and private spaces of politics and home to promote their anti-feminist agenda. Indeed, the conservative movement that emerged after World War II was composed of, as Lisa McGirr describes it, a “strange mixture of traditionalists and modernity, a combination that suggests the adaptability, resilience, and, thus perhaps, intractability of the Right in American life.”Footnote 87 While McGirr's study focuses primarily on the postwar conservative movement in California, her work demonstrates that, although the strategy had evolved from the turn of the century, the conservative rhetoric remained largely the same. With a foundation established by the anti-suffragists, anti-feminist leaders then worked to unite a national movement with strong grassroots support, much like their suffrage counterparts had done in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.