In a neatly organized scrapbook, Lucretia del Valle Grady (1893–1971) documented her life's political trajectory through newspaper clippings she gathered over the years. One 1928 profile celebrated her prominent “Spanish” heritage in California, her theatrical career in Los Angeles, her father's political influence and activity as well as her work for women's suffrage. Concluding with her leadership in the San Francisco Bay Area's club movement, the profile highlighted her ideas about citizenship: “Citizenship is not a matter of sex, and men and women should both work together rather than in separate units.” While Lucretia espoused the equality of men and women and the notion of ‘working together,’ her political organizing almost exclusively focused on women.

This essay charts Lucretia's political trajectory from 1910 until 1940, a period shaped by varying ideas and experiences surrounding women's citizenship. While 1920 looms large as a “defining” moment in the history of women's suffrage, the political work of Lucretia del Valle reminds us that singular dates and campaigns seldomly capture the full scope of women's political philosophies and activities. Lucretia's political aspirations and organizing arose from her Spanish-Mexican heritage and demonstrate that the path to empowerment originated in a variety of spaces not usually associated with the familiar narratives of suffrage. Her story illuminates that cultural background shaped women's distinct notions of civic duty and understandings of citizenship. In her own family, Lucretia saw Californios holding public political power and witnessed women as landowners and heads of households. Moreover, as a Californian, Lucretia came of age with universal suffrage in that state, turning eighteen in 1911. She understood “universal” suffrage as women's natural right fundamentally rooted in their humanity.

Lucretia del Valle Grady was born on October 18, 1892, in Los Angeles. Her mother, Helen “Nellie” White, a widow and native of Southern California, was the daughter of a prominent merchant and rancher who founded the city of Pomona. Lucretia's father, Reginaldo del Valle, traced his California roots to the late eighteenth-century Spanish-Mexican settlers of Los Angeles. While Lucretia was born into a bicultural family, Californio cultural practices defined her household. Nellie converted to Catholicism and the couple raised Lucretia as culturally Catholic. Although Lucretia left a record predominantly in English, her subtle and sporadic use of Spanish salutations and “sayings” as well as correspondence and interaction with her grandmother, Ysabel Varela del Valle, suggest that Lucretia felt comfortable with Spanish language or was likely bilingual. The family resided at 3508 S. Figueroa Street just south of Downtown Los Angeles, surrounded by a diverse community of neighbors and family members. She attended Los Angeles High School and then enrolled at the University of Southern California and later had theatrical training at Egan Dramatic School in Los Angeles.Footnote 1

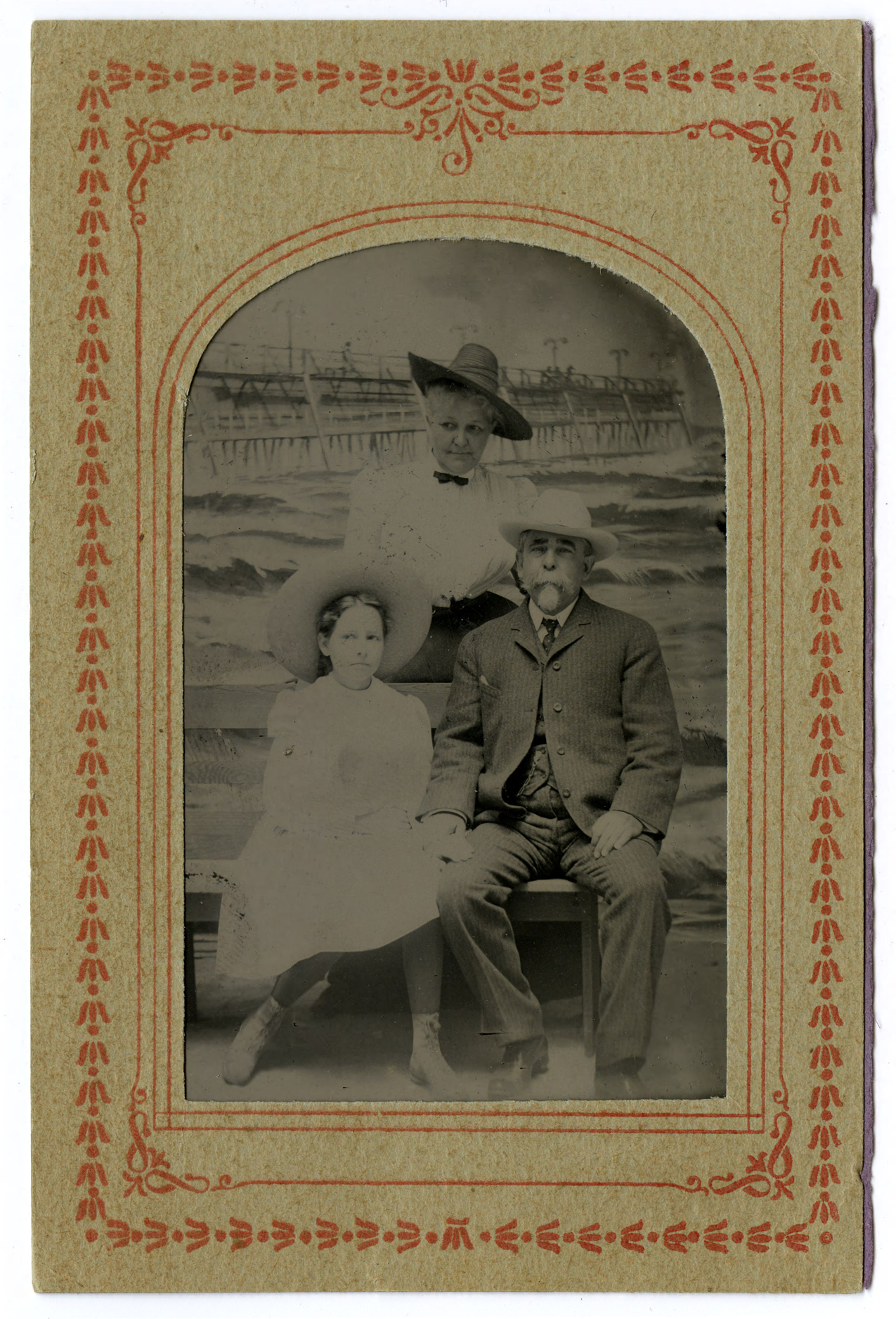

Visits to Rancho Camulos, the vast del Valle rancho held by the family since the 1830s, were an important part of Lucretia's upbringing and helped her to forge a close relationship with her paternal grandmother, Ysabel del Valle. Her grandmother gave her a model of women's power within family networks, business ventures, and civic duty in the late nineteenth century. Born in 1834, Ysabel came from the Avila family of Los Angeles, settlers that arrived in Los Angeles in 1783. She married Ygnacio del Valle, the last Mexican alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles. After U.S. conquest, the del Valles downtown plaza adobe came to serve as a civic hub for, among other things, political meetings for Los Angeles Democrats. However, as American migrants and eager settlers eyed seemingly vacant land, the del Valles moved to their rancho, located in the Santa Clarita Valley. Lucretia often spent summer vacations and school holidays there. Widowed in 1880s, Ysabel managed Rancho Camulos with her daughter, Josefa del Valle Forster. They oversaw numerous business ventures, including the negotiation for a Santa Fe Railroad depot at Rancho Camulos and the harvesting of diverse crops including beans, olives, grapes for wine, and citrus. Ysabel represented generations of Spanish-Mexican women who exercised their rights as landowners, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders. Like her plaza home during the 1850s, the rancho became a social hub. Known throughout the region for hosting large crowds of visitors from all walks of life, Ysabel served as a central figure in Californio society (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Lucretia del Valle seated with her parents, Reginaldo del Valle and Helen White, in early 1900s.

Lucretia's father, Reginaldo, also influenced her in important ways. A political figure and public servant, his own political development occurred at a moment of great political change for Spanish-Mexican residents in California.Footnote 2 Elected to the state assembly in 1880, he was as the only representative of Spanish-Mexican heritage when he took office.Footnote 3 Reginaldo and other Californios forged a political identity that historian Rosina Lozano argues drew on their position as “treaty citizens.” They were Spanish-Mexican residents of the areas conquered by the United States in the Mexican American War (1846–1848) who secured citizenship and land rights through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Lozano explains that “Treaty citizens became the first group of people considered ambiguously white to gain collective citizenship in the United States.”Footnote 4 Although Californios like the del Valles often had mixed race backgrounds that included Indigenous, Mestizo, African, and European heritage, their status as “treaty citizens” made them legally “white.”Footnote 5 They nonetheless maintained distinct Spanish-Mexican cultural practices especially the Spanish language and Catholic religion.Footnote 6

This family heritage of citizenship, public service, and women's civic prominence contributed to Lucretia's political awareness and served as a foundation that enabled her to envision her own place in society as defined by citizenship and civic engagement. Two further experiences in Lucretia's early adulthood reveal her confidence and willingness to take on prominent public roles. Politically symbolic, each furthered her own ambitions for leadership and advocacy but also contributed to larger claims of belonging by Spanish-Mexican Americans.

In 1912, Lucretia took the lead role of Senora Yorba in John Stevens McGroarty's famous Mission Play. Her family's well-known “Spanish” past gave the play authenticity, while translating her historical legacy through a play palatable to white American audiences afforded Lucretia authority and opportunity. The Mission Play contributed to the phenomenon Carey McWilliams called the “Spanish fantasy past.” While historians have suggested that a romanticized past was an Anglo creation, the del Valle family invested as stockholders in the play and supported its version of U.S. history in which their past was also celebrated as uniquely American. It was a political statement of belonging in which the Spanish-speaking Catholic missionaries brought “civilization” to California, giving contemporary Spanish-Mexicans a claim to belonging and citizenship in the state. Lucretia herself also gained fame as an actress and prominence that she used to engage in other civic projects.Footnote 7

In a second more explicitly political action, Lucretia joined her father on his visit to Nogales, Mexico, as special U.S. envoy to research factions of the Mexican Revolution.Footnote 8 Selected for his linguistic ability and cultural background as strengths for the position, this opportunity seemed to meet Reginaldo's ambition for a diplomatic position in Mexico, a goal of his since 1893 when he campaigned for the post of ambassador.Footnote 9 National newspaper coverage of Lucretia profiled her as an example of women's diplomatic participation. One article stated: “beautiful Los Angeles girl is joining her eloquence to that of her father … in an effort to bring peace among the warring factions, whose ancestral blood is Castilian like her own.”Footnote 10 Her Spanish ancestry added an exotic touch that strategically ignored any indigenous or mestizo roots for either Lucretia or Mexico.

Lucretia gave the article prominence in her scrapbook, suggesting the significance of the trip in her life. The article recognized both her talents and her heritage, asserting that Lucretia's role was more than that of a daughter accompanying her father; “Significance is lent to the rumor that Miss Del Valle is acting as the direct assistant of her father by the haste with which she left Los Angeles.”Footnote 11 When Reginaldo's report contradicted the Wilson administration's desired course of action, the secretary of state dismissed him as too biased. Instead they dispatched another envoy unfamiliar with Mexico and contended “a complete lack of knowledge of the Mexican context an advantage.”Footnote 12 The political dynamics in Mexico and the Wilson administration must have been noteworthy for Lucretia, and she certainly found meaning in “assisting” her father with “diplomatic” effort. Elements of leadership and diplomacy shaped her ambitions for similar opportunities. They also forged a sense of how she envisioned the possible ways for political participation. In addition, the Wilson administration's derision of the del Valle's cultural heritage as a “disadvantage” points to the careful associations Lucretia and del Valle's would have in declaring certain cultural associations, such as with “Mexican” elements. In contrast, Lucretia's return to the Mission Play after her diplomatic assignment shows that, indeed, the ideas imbued in the play and its cultural association performance was indeed acceptable, safe, and celebrated.Footnote 13

Upon Lucretia's return to the Mission Play in 1916, she agreed to participate in its national tour. While Lucretia's initial participation in the Mission Play capitalized on her cultural authority, her time on the national tour pointed to a shift toward a growing ambition for leadership. In her correspondence with Southern California regional booster Charles Fletcher Lummis, she shared her frustration with management of the play. While in Sacramento—a city she characterized as “mediocrity at its worst”—she questioned the director's promotion. In her words, “… as to press work, he [John Steven McGroarty] is quite set and cannot see the need. As far as I can see we haven't had any and it makes my slightly commercial spirit groan, for this play is reeking [sic] with glorious, dignified romantic get over material …”Footnote 14 In Omaha, she and other cast members had to forego their salary due to financial troubles. Lucretia took charge, writing promotional ads in local newspapers.Footnote 15 She wrote her half-sister, Helen, “unless instant approval was met with in Chicago, the outlook for the remaining portion of the tour was dubious.”Footnote 16 The play was not met with “instant approval” and Chicago was its last stop.

Despite the failed tour, Chicago presented Lucretia with other opportunities. She enrolled in philosophy and economic courses at the University of Chicago. Lummis reacted to her news, which she clearly expected to shock him, “I haven't fainted at your announcement of matriculation at the Chicago University.”Footnote 17 He understood her ambitious nature and her potential, contending that such courses “… ought to help you not only in your present work, but in the more important things you hope to do …” He continued, “There is so much really constructive work everywhere … and there are people who ought to be doing it—chiefly women who want to do something and have nothing else to do, who don't do anything better worthwhile … than reforming with kid gloves.”Footnote 18 Taking a jab at clubwomen who prefer the comfort of reform, a work that can be done carefully and delicately, Lummis knew that Lucretia believed in a political engagement with more rigor, more challenge, and possibly more outside realms of comfort.

As had her experience in Mexico, courses at the university nurtured her interest in politics. Returning to Los Angeles in early 1917, Lucretia donned a new cropped hairstyle and left the Mission Play. She spent time circulating through social circles of varying political interests.Footnote 19 She attended weekly dinners at Lummis's home El Alisol, enjoying the company of a wide range of artists, intellectuals, and socialites. On one occasion, Lucretia shared the table with Dr. Margaret Chung—a USC graduate and the first Chinese American physician (fig. 2).Footnote 20

Figure 2. Portrait of Lucretia del Valle, ca. 1920s.

With her mind still on politics, Lucretia decided to pursue graduate studies at Columbia University's Department of Political Philosophy in the fall of 1917. In New York, she expected to study politics—stating she was prepared for “studying nine hours a day”—not engage in it.Footnote 21 As a Californian, Lucretia had enjoyed the privilege and right of suffrage since 1911; however, she, like other women from the West, found herself disenfranchised in New York. Enraged with her loss of status as a citizen, Lucretia felt the impulse “of putting theory to the test” and wrote Lummis:

This is not a letter but a request—Suffrage or the need for it here is more than visible its plain and the attack is worse than dead its bloodless … I want to know if you don't think I should do platform work this winter for suffrage?Footnote 22

The New York suffrage movement was key battleground for the national struggle for universal suffrage and Lucretia joined the fight, channeling her energies in two ways. First, she focused on strategies to increase the appeal and promotion of their cause using her talent as a performer. She complained to Lummis that “the women speakers here couldn't convert a California Jack rabbit and at least I have style …”Footnote 23 Lucretia's harsh assessment of the “bloodless” attack focused on delivery and style, not the message. Public speaking and taking to the streets proved to be key efforts to gaining support for suffrage.Footnote 24 Lucretia understood that her seven years of experience on stage placed her at a key advantage to do platform work. As Margaret Finnegan in Selling Suffrage explains, “suffragists increasingly saw themselves as public performers capable of appropriating that space and manipulating impressions of themselves and the cause.”Footnote 25 While accustomed to public performance, she faced a tougher audience and more was at stake when speaking about suffrage. Platform work not only had to be entertaining, but it also had to “overwhelm onlookers’ negative impression of women voters.”Footnote 26

In addition, promoting suffrage through her public speaking, Lucretia also focused on organizing women who had lost suffrage by moving to New York. She coordinated a meeting with another Californian friend, Inez Cassidy, “of all the former women residents of suffrage states who have lost their right.” At the meeting they discussed plans “to participate in the big suffrage parade” held that fall.Footnote 27 The connection between women of the East and women of the West was notable and Lucretia picked up on the sentiment.Footnote 28 These new directions for Lucretia's theatrical talents clearly marked a change in her personal as well as political trajectory. While in New York she declined offers to return to the theater. In fact, she never again performed on stage. She also left no record of continued efforts for suffrage. In fact, the record suggests her involvement was brief and temporary while she was in New York and disenfranchised.

While in New York, Lucretia married economics professor Henry Grady—an old friend she knew from California. Lummis joked that “Grady was the PhD she got at Columbia.”Footnote 29 After her marriage, Lucretia continued to use “del Valle” in her name, highlighting her Spanish-Mexican heritage while she traversed the East Coast and throughout her subsequent moves abroad. Initially, however, the couple moved into a Manhattan apartment, but Lucretia confessed that she did not expect to stay very long in a “NY cage. The open air of California means living to me.”Footnote 30 California was not in the cards for the couple; rather they moved to London where Henry took a position as U.S. trade commissioner for the United States. While in London, Lucretia enrolled at the London School of Economics to continue her studies and continued some degree of activism of women's issues, such as marching for universal suffrage in London.Footnote 31

By 1928 Lucretia and Henry returned to California and settled in Berkeley with their first two children, Reginaldo and Patricia. Henry became dean of UC Berkeley's School of Commerce while Lucretia swiftly picked up an active calendar working in the Bay Area club movement.Footnote 32 Lucretia quickly took on a variety of leadership positions in local clubs and organizations including the Democratic Club of California, Political Science Club of Northern California, International Affairs of the Women's Club Federation, Women's City Club of Berkeley, Berkeley's branch of the League of American Pen-Women, as well as the little theater movement in Berkeley (to name just a few).Footnote 33

Her efforts and energies focused on “politically” based organizations with intellectual or academic underpinnings. With suffrage secure across the nation, the question facing former suffragists was how to put their franchise to work, locally and nationally. As scholar Ellen DuBois argues, some drew a distinction between “voting” and “politics,” because an “aversion to practicing politics was women's horror of political parties …”Footnote 34 Lucretia did not have this fear, likely as a result of her family's history with the Democratic Party. It is significant that in this period she did not turn to reform work nor culturally focused campaigns, as she had in her early years with the Mission Play. Moreover, club work was not a “recreational activity” for Lucretia. She firmly believed it was space to carry out critical organizing on political issues. Rather, motherhood, as in one local feature titled “In Club Women's World: Her Home and Her Children,” was her “favorite hobby,” while her social and political engagement was her work.Footnote 35

In 1927, a local San Francisco Bay Area newspaper published Lucretia's response to the question, “Why I am a Clubwoman.” She opened with a question, “Who in this intensely interesting day of social and political experimenting can sit complacently by playing merely a passive part in the world drama?” She set the global stage and world that emerged out of World War I as her context for women's club work and its possibilities. She explained, “It is a world born of new alliances—peoples of the earth articulate for the first time, impressing their desires on the social structure: new mechanical impetus too powerful to be comprehended.” Lucretia noted the exciting possibilities of the rupture in old regimes and the emergence of new nation-states in the post-Great War period that connected the formerly disenfranchised and disengaged. “[L]ast but not least,” she advocated for “the social and political voice of the women of the world, voicing in no uncertain terms the fact that she means to add her fight of cooperation to the now existing social order.” Clearly Lucretia saw suffrage not just as a mission accomplished but as a catalyst to shape the political landscape. According to Lucretia, club work offered a good place for women to engage in political work and their public role as citizens.

Historians have debated about whether the 1920s were a moment of decline or of increased possibility for feminist activism that seemed to reach an apex with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Lucretia's club work exemplifies how former suffragists continued their work in politics. Following ratification, women now looked to enter traditionally “male institutions,” especially political parties and legislative bodies.Footnote 36 Lucretia's choice to use club work to engaged with those institutions suggests she envisioned a way that they could be solidly led and organized by women like herself. For example, in September 1929 she served as the Berkeley committee chair for the First Annual East Bay “Woman's Day.” She characterized the event not as a “eulogy” for women's work, but a formal recognition of women's equal status with men and their political possibilities. She stated that it was an opportunity to “take stock of the accomplishments of women with a view to the further extension of her participation.” Speakers included women in art, music, literature, and business with discussions on international affairs. She believed the event would “emphasize the right of women to be considered on equality with men as intelligent, responsible citizens in a great commonwealth and co-workers in the fast-changing world.”Footnote 37

During the Great Depression, some of her work became more formalized when she was elected chairperson for the National Recovery Administration's (NRA) Women's Committee in the Bay Area. As a strategist for “unemployed self-help,” Lucretia gained support and momentum for a “labor for goods” exchange program that had originated in Southern California. Lucretia led the Bay Area efforts with intensity and saw it as a program that went beyond “charity work.” She envisioned the movement as not only self-help but also as lessons in civic engagement and leadership. At one of the events she chaired, she mapped out her recommendations about leadership and organizing in starting new barter groups. She advised, “Don't let your barter group be formed from the outside; let it grow up around the need. Second, don't invest one person with too much authority. Third, rotate your leadership.”Footnote 38The barter program originated in Compton, California, and Lucretia was instrumental in launching the program in the Bay Area. Strategizing to “marshal civic forces,” Lucretia organized the San Francisco Cooperative Barter Association and created what we today would call a pop-up service that included a “clothing section, a beauty shop, and sewing room where women can learn to repair and make clothing.”Footnote 39

Due to her club connections and NRA work, Lucretia rose in the ranks of the Democratic National Committee. She started as a vocal advocate for Al Smith in the 1928 presidential election and subsequently served as a member of the California delegation that year as well as 1936 and 1940. In 1936, she, along with seven other women, was named vice chair and reported to Mary “Molly” W. Dewson, head of the Women's Division of the DNC. In 1937 she served as a member of the Democratic National Committee from California.Footnote 40

While on this national stage, Lucretia deployed all she had learned in her years of diplomacy and club work and party leaders took note. Before Lucretia took on the work, Dewson described the California campaign as “an impossible situation” as the party had no state head of the women's division. She was grateful for del Valle Grady's skills, giving her much latitude in contacting DNC officials. “Lighting a fire” under them was Lucretia's “forte. I can count on you,” she wrote. Lucretia's correspondence with Dewson reveals that she knew her value to the party noting, for example, that she had the ability to mobilize support. “All of the women, but three, are very personal friends of mine most of them twenty years who understand my peculiar status of authority in this particular state.” That “peculiar status of authority” likely meant her impressive reputation as a clubwoman in Northern California and as a member of the del Valle family and well-known performer in Southern California. She was correct. The Roosevelt campaign indeed relied on Lucretia and other women like her in different states. Their work transformed Democratic Party politics and women's participation, which expanded from 73,000 women in 1936 to 109,000 women in 1940.Footnote 41 The experience for Lucretia was equally transformative. She became close friends with Eleanor Roosevelt, and her work for the party likely helped secure her husband the position of assistant secretary of state in Roosevelt's cabinet in 1939. In a report on his appointment that both diminished and praised her, Time magazine observed that “Besides his ability and geniality, Dr. Grady at 57 is famed also for his high-powered, jet-haired Spanish-blooded little wife: Lucretia del Valle Grady, vice chairman … of the Democratic National Committee.”Footnote 42 Lucretia and her family relocated where she charmed DC society with her stories of California and continued her political work.

CONCLUSION

Lucretia continued to serve as a Democratic National Convention delegate. In 1944, she became a president elector for California. Nor was her political work limited to the United States. While her husband served as U.S. ambassador to India (1947–48), Greece (1948–50), and Iran (1950–51), she always brought a vision and action points for addressing women's rights in each of those respective countries.Footnote 43 Years of world travel and diplomacy gave her authority to serve as a spokesperson for women's rights in the United Nations Women's Forum and serve as a leader in the international organization's Women's Conference. Lucretia del Valle coalesced the multiple facets of her life. She shaped multiple worlds and was a product of them as well. In 1986, family biographer Wallace Smith called her the “Last of the Señoritas,” a reference that paints her as a relic of a bygone era.Footnote 44 However, as charted in this profile, her trajectory from a stage actress to modern suffragist to political operative suggests that she played many roles, took on many stages, and revealed the many possibilities of political participation both before and after 1920.