Global mass migration was one of the defining features of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. Between 1870 and 1930, more than 30 million immigrants entered the United States, with 1.2 million entering in 1914 alone. By 1930, there were more than 14 million foreign-born residents in the United States, representing as much as 14.4 percent of the total U.S. population.Footnote 1

But intense xenophobia also defined the era. Within the same period, numerous anti-immigrant organizations, politicians, and writers promoted the idea that immigrants were serious economic, racial, political, and cultural threats to the United States. Congress responded by passing a series of federal immigration laws that barred growing numbers of immigrants from entering the United States and strengthened the federal government's capacity to inspect, detain, track, and deport them. These included the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the national origins quotas put in place by immigration restriction acts in 1921 and 1924.

Not just an expression of racism and white supremacy, the drive to restrict immigration was rooted in the same reformist impulses to ban child labor, regulate the railroads and the monopolies, clean up urban slums, combat political corruption, and advocate for temperance. Laissez-faire policies toward immigration, reformers believed, gave big business, steamship companies, and corrupt politicians access to cheap labor and immigrant votes. Progressives such as Jacob Riis thought that battling the societal, economic, and political ills plaguing America—like immigration—required new regulations and an active class of reformers.Footnote 2 But shaped by eugenics, pseudoscientific racism, and the desire to maintain white (Anglo-Saxon) supremacy, many of the progressives’ recommended immigration “reforms” only legitimized discrimination in immigration policy and ended up subverting the very ideals and American values they were purportedly acting to preserve.

American historians have always recognized the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era as a high point of American xenophobia. They have noted how immigration plummeted under the forty-year reign of the national origins quotas. The United States would not reopen its gates until after the 1965 Immigration Act abolished the quotas and banned discrimination in immigration law. This is the standard timeline that immigration historians and others have used to explain the rise (in 1924) and fall (in 1965) of xenophobia in the United States. It has been established in our historiography by scholars such as John Higham, whose 1955 classic, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (updated and revised in several editions until 2002), helped generations of historians understand what he called “nativism”—the “antiforeign spirit” targeting European immigrants from 1880 to 1924.Footnote 3 As Higham explained, nativism was a consequence of American social, economic, and political “anxieties” that rose and fell with “successive eras of crisis and confidence in public opinion.” Thus, confidence in the early 1880s helped to limit the anti-immigrant impulse, while crisis in the 1890s allowed it to flourish. Recovery in the early twentieth century diminished it, returning crises from 1915 to the mid-1920s brought it back, and so forth. Nativism was finally defeated, Higham explained, “when the long depression … lifted, social anxieties relaxed, and urban renewal flowered” after the 1930s.Footnote 4

Extending this framework even further, other historians have gone on to describe the 1965 Immigration Act as the final nail in xenophobia's coffin. The law embodied what historian Roger Daniels has called a “high-water mark in a national consensus of egalitarianism” and a “reassertion and return to the nation's liberal tradition in immigration.”Footnote 5 Legal scholar Gabriel Chin argues that the law was passed with a “racial egalitarian motivation” and took “a revolutionary step toward non-discriminatory immigration laws.”Footnote 6 Historian Nathan Glazer went so far as to claim that the act “marked the disappearance from [f]ederal law of crucial distinctions on the basis of race and national origin.” The nation agreed, he continued, that “there would be no effort to control the future ethnic and racial character of the American population and rejected the claim that some racial and ethnic groups were more suited to be Americans than others.”Footnote 7 Higham would declare in 2000 that “from the 1930s to the 1980s, the question of the stranger never assumed any strong shape or clear significance.”Footnote 8 As late as 2002, just as Arab and Muslim American communities were facing an onslaught of government surveillance and harassment and were the victims of violent hate crimes following the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Higham would offer the astounding pronouncement that nativism had collapsed in America and that “no revival of a nativist or racist ideology” had replaced the triumph of American liberalism of the civil rights era. That he made this statement even as he himself used racially charged language to describe “a flood of Mexican immigrants … overrunning black neighborhoods” seemed unproblematic to him.Footnote 9

Higham's interpretation of the rise and fall of nativism might have been a fitting explanation of the evolving status of the European immigrants who were the primary subjects of Strangers in the Land. They had been “racial inferiors” in the 1920s, but had transitioned to become builders of our “nation of immigrants” in the 1960s. But Higham's interpretation certainly does not work for non-European immigrants. In this timeline's march toward equality, there is no place for the mass deportations of Mexican Americans during the 1930s; the removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II; “Operation Wetback” in 1954; the new restrictions placed on immigration from the Western Hemisphere in the 1965 Immigration Act; the so-called “war” against so-called illegal immigrants beginning in the 1990s; the resurgence of Islamophobia in the early twenty-first century; or the Trump administration's pledges to build a wall, deport millions, and ban Muslims.

It is now clear that instead of marking the end of xenophobia in America, the 1965 Immigration Act launched the beginning of a new and different story about how xenophobia functions and why it is thriving today. The framing of xenophobia as a force that rises and falls has left us unprepared to fully explain how xenophobia can exist and flourish during times of peace and war, economic prosperity and depression, low and high immigration, and racial struggle and racial progress. It also prevents us from seeing how xenophobia has become institutionalized and normalized in the United States today. Xenophobia has never gone away. Like racism, it has simply evolved and adapted. Over the decades, generations of anti-immigrant leaders, politicians, and citizens have molded xenophobia to fit new contexts, identify new threats, and enact new solutions to the “problem” of immigration.

Defining Xenophobia

In order to make sense of how xenophobia works in the United States in both the past and present, we need a major redefinition of American xenophobia. Coming from the Greek words xenos, which translates to “stranger,” and phobos, which means either “fear” or “flight,” “xenophobia” literally means fear and hatred of foreigners and those perceived to be foreign. Beyond the literal translation, however, there is no single or uniformly agreed-upon definition of the term as used in academic, popular, or human rights discourses. Broadly speaking, psychologists tend to focus on the psychology of fear and view xenophobia as an exclusionary logic—a discriminatory ideology. Sociologists gravitate toward framing xenophobia as a social system that maintains and constructs social and cultural boundaries.Footnote 10 These interdisciplinary frameworks suggest that we must not only study what xenophobia has meant, but also what it has done.

I draw from all of these approaches to identify xenophobia as both ideology and action. It is an irrational fear, hatred, and hostility toward immigrants, refugees, or others considered “foreign” as threats. It is also a form of racism that has functioned alongside slavery, settler colonialism, conquest, segregation, and white supremacy as a function of institutionalized discrimination that has shaped so much of American history. Indians, enslaved Africans, and free blacks were the first “others”. How immigrants have fit into this existing racial hierarchy and nation-building process has shaped our welcome of and aversion to them from the colonial era to the present. Their “foreignness” has always been the primary basis for xenophobic attitudes and action. But that “foreignness” has itself rested on multiple, intersecting classifications, such as race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, gender, sexual orientation, and class.Footnote 11

Like racism, xenophobia is a system of power that is used to divide, control, and dominate. One of the ways it does so in the United States is by promoting an exclusive form of American nationalism and a narrow definition of who is “American” and, equally important, who is not. Xenophobia has thus worked hand in hand with racism and white supremacy to support preferential treatment of so-called “natives” (i.e., white Anglo-Saxon Protestant settlers and their descendants) over foreigners, and promotes a nativism that purports to put “Americans” first. While most scholars use the terms “xenophobia” and “nativism” interchangeably to describe anti-immigrant sentiment, I suggest that we take a different approach by critically examining the strategic use of the label “native” by xenophobes. Because the United States is a settler colonial society with birthright citizenship laws, who is considered a “native” has been crucially important from its inception. It has determined rights to land (economic power), the vote (political power), and the symbolic cultural power of being recognized as rightfully present in the country. As used in xenophobia, “native” status has had little basis in actual indigenous roots. Rather, it was a deliberate act of appropriation by mid-nineteenth-century white Protestant settlers who seized the “native” label from indigenous peoples and claimed it for themselves in order to exert dominance over both Native Americans and new immigrants. In this way, American nativism simultaneously disempowered indigenous peoples and foreigners. While most scholarly and popular uses of “nativism” obscure xenophobia's use in maintaining both settler colonialism and anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, future scholarship should do more to address these gaps and connect Native American and immigration histories.Footnote 12

Another important facet of American xenophobia is how it has succeeded through repetition. Because of the diversity of immigrants in America and the way immigration has been part of the United States’ ongoing processes of racial formation, American xenophobia has built on the demonization of existing immigrant threats to mobilize public opinion and policy against new ones. During and after the successful exclusion of Chinese immigrants in the late nineteenth century, for example, groups that were considered to be “just like” the Chinese, such as Japanese, Koreans, South Asians, and Filipinos, were similarly condemned to immigration restriction and exclusion. Similarly, all Latinx peoples have found themselves tainted by the “illegal alien” label that was initially used to refer to and demonize Mexican immigrants, and the “radical Muslim terrorist” label has been indiscriminately applied to Muslim and Muslim-appearing individuals regardless of their actual faith. All of these campaigns build upon and intersect with each other.

Lastly, xenophobia sanctions discrimination that targets immigrants and refugees. This includes unjustly exploiting, segregating, excluding, criminalizing, and removing them from the United States, and it has amplified economic and racial inequality, social exclusion, and religious intolerance. Attacks on immigrants have consistently threatened core civil and political rights upon which American democracy is built and have degraded American citizenship. The strain and violence of xenophobia has had generational consequences for some immigrant communities.Footnote 13 Even amidst near-constant immigration to the United States, xenophobia has become deeply embedded in our laws, our politics, our culture, and our world view.

Xenophobic Thought and Policy in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

When we employ this definition of xenophobia, we can easily recognize the Gilded Age and Progressive Era as one of the most important periods shaping the history of American xenophobia. It was during this time that xenophobia became a part of our mainstream political culture and intellectual thought and was legitimized in policy. The connection between xenophobia and the Gilded Age and Progressive Era works the other way around as well: xenophobia drove some of the most defining features of the period—namely, the expanded capacity and power of the nation-state and the growth of U.S. global power and influence.

To dive deeper into these ideas, let us first explore xenophobia's growing power to shape public attitudes, popular culture, and science during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. To do that, we need Madison Grant.

Madison Grant would be the first to admit that he came from “good stock.” His family had long established roots in the country and he made his rounds among the other lordly patricians in Manhattan society. He was a wealthy sportsman and hunter, a charter member of the Society of Colonial Wars, founder and later chairman of the New York Zoological Society. He was a published author whose early works included a series on North American animals like the moose, caribou, and Rocky Mountain goat. But he is best known for his “racial history of Europe” published in 1916, The Passing of the Great Race.

Grant drew upon decades of pseudoscientific racial thinking that categorized humanity into different racial groups and ordered them into a strict hierarchy based on intellect, ability, and morality. According to Grant and other race thinkers of the time, these human abilities and characteristics were inherited and could not be “obliterated or greatly modified by a change of environment.”Footnote 14 For Grant, the centrality of race thus meant to “admit inevitably [to] the existence of superiority in one race and of inferiority in another.”Footnote 15

Grant sorted all European peoples into three groups: Nordics, Alpines, and Mediterraneans. Taking note of linguistics, physical features, and cephalic index, he argued that each group was a distinctive race and thus possessed (and inherited) distinct moral, social, and intellectual characteristics that made some more fit to lead than others. The Nordic race from northern and western Europe, for example, was “long skulled, very tall, fair skinned with blond or brown hair and light-colored eyes,” and was, by far, the superior race. “The Nordics are,” Grant explained, “all over the world, a race of soldiers, sailors, adventurers, and explorers, but above all, of rulers, organizers, and aristocrats.”Footnote 16 These abilities, he maintained, contrasted sharply with any of the other European races.

The Mediterranean race from southern Europe was also long skulled like the Nordics, but “the absolute size of the skull” was significantly smaller. They had “very dark or black” eyes and hair and “the skin [was] more or less swarthy.” They were shorter than the Nordic race and their “musculature and bony framework [was] weak.” The Mediterranean race was “inferior in bodily stamina” to the Nordic race, but Grant conceded that it was superior in the (feminine) fields of art. The Alpine race from central and eastern Europe was a race of peasants, “round skulled, of medium height and sturdy build.” They, too, lacked the abilities of the Nordic race, and were the lowest of the European races.Footnote 17

Using this theory of Nordic (Anglo-Saxon) racial superiority, Grant went on to make strong arguments against immigration. According to him, unlimited immigration coupled with Americans’ naive belief in the “melting pot” theory of assimilation was causing the nation to fall into serious decline. America had been full of greatness when the population was mostly Nordic. “But now swarms of Alpine, Mediterranean, and Jewish hybrids threaten to extinguish the old stock unless it reasserts its class and racial pride by shutting them out.”Footnote 18

New immigrants were literally driving out what Grant and others called “native” (i.e., white Anglo-Saxon Protestant, or WASP) Americans in the countryside and in the cities. As a result, immigration was causing “race suicide,” the lowering of the birth rate amongst white Anglo Saxon Protestant Americans, and the “passing” of the Nordic race that had made America great. “The poorer classes of Colonial stock, where they still exist, will not bring children into the world to compete in the labor market with the Slovak, the Italian, the Syrian and the Jew,” Grant explained. And if they did not resist this displacement, the “native American,” just like real Native Americans, would ” entirely disappear” in some large sections of the country. This would be a disaster not only for the “great” Nordic race, but for the United States as a whole, for only the Nordics could truly lead the country during these troubled times. This was neither a matter of “racial pride” nor “racial prejudice,” he insisted, but rather “a matter of love of country.”Footnote 19

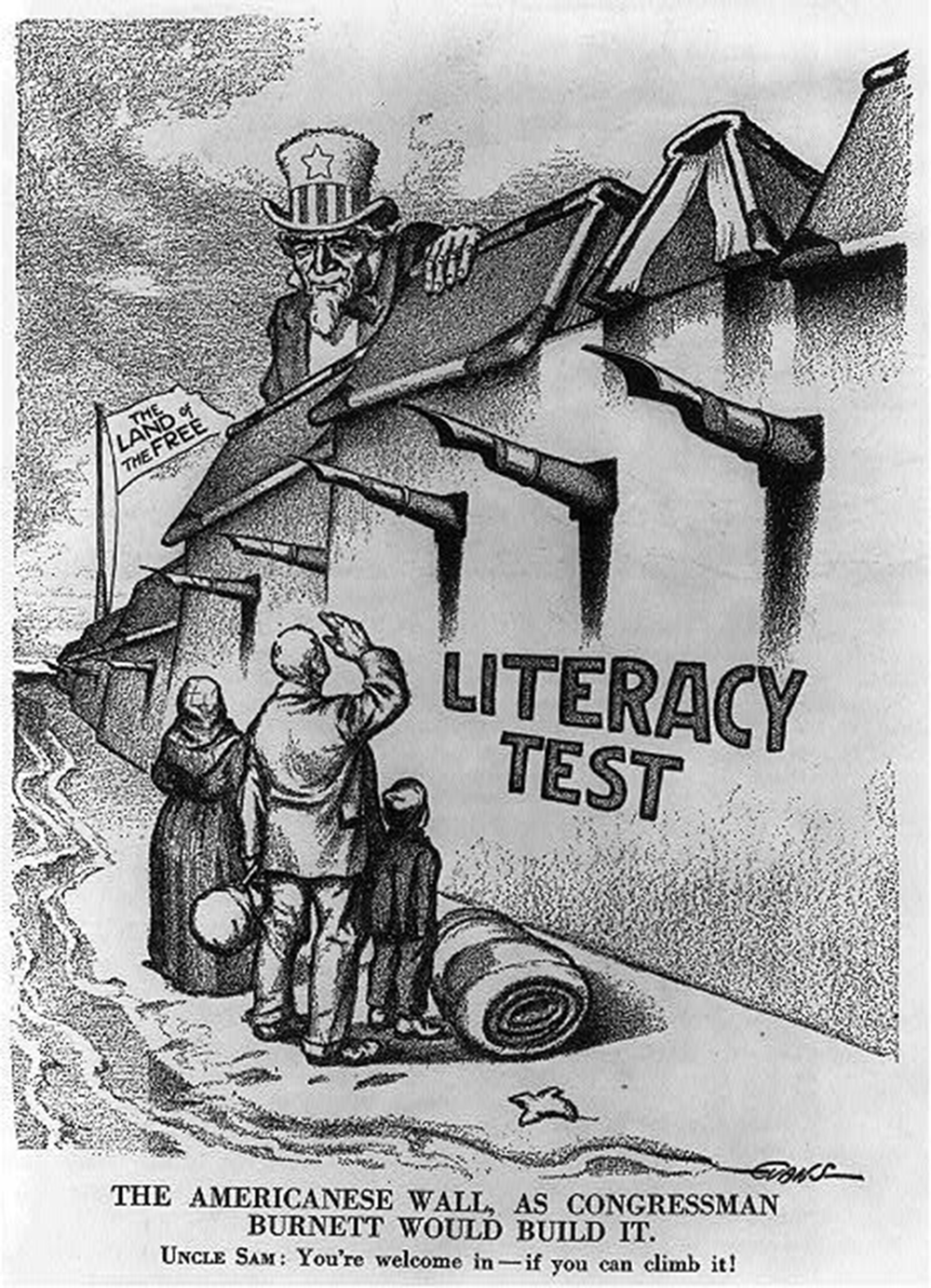

Figure 1. Xenophobia has often used the language of natural disasters to define immigration as a threat. In this 1903 illustration published in Judge magazine, Uncle Sam clings to the shore defending the United States while the “high tide” of “riffraff immigration” threatens to flood the country. Several different immigrant threats are represented among the invasion: paupers, illiterates, anarchists, outlaws, degenerates, criminals, and members of the mafia, all male and all drawn in stereotypical fashion to represent southern and eastern Europeans, Mexicans, and Chinese immigrants. Cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, “The High Tide of Immigration—A National Menace,” Judge, Aug. 22, 1903. Courtesy of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

Madison Grant was not the first voice to raise the alarm against the new immigrants. In the 1880s, Protestant clergyman Josiah Strong spoke staunchly against the many perils of immigration—crime, low morals, and downtrodden cities—that threatened the safety of the nation and civilization itself.Footnote 20 In the 1890s, the Boston-based Immigration Restriction League called attention to the “immigration question” involving southern and eastern European immigrants who, it said, were illiterate, did not try to assimilate or become Americanized, and were prone to radicalism. According to the League, the swelling ranks of the unemployed and the criminals in the country could all be blamed on immigration.Footnote 21

By 1907, the U.S. government was concerned enough to commission a massive study on immigration led by U.S. Senator William P. Dillingham, two other senators, three members of Congress, and three other citizens appointed by President William Howard Taft. The resulting forty-one volume report of the Dillingham Commission and its Dictionary of Races or Peoples, published in 1911, offered a definitive list of races and ethnic groups, their general characteristics, and their physiognomies, and ranked them according to desirability. It recommended major transformations in immigration policy. Moving forward, the commission proposed, the United States should ensure that both the “quality and quantity” of immigration be managed “as not to make too difficult the process of assimilation.”Footnote 22

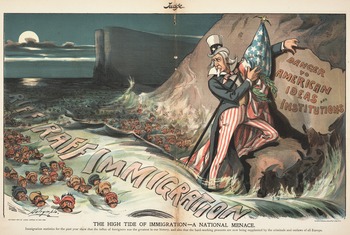

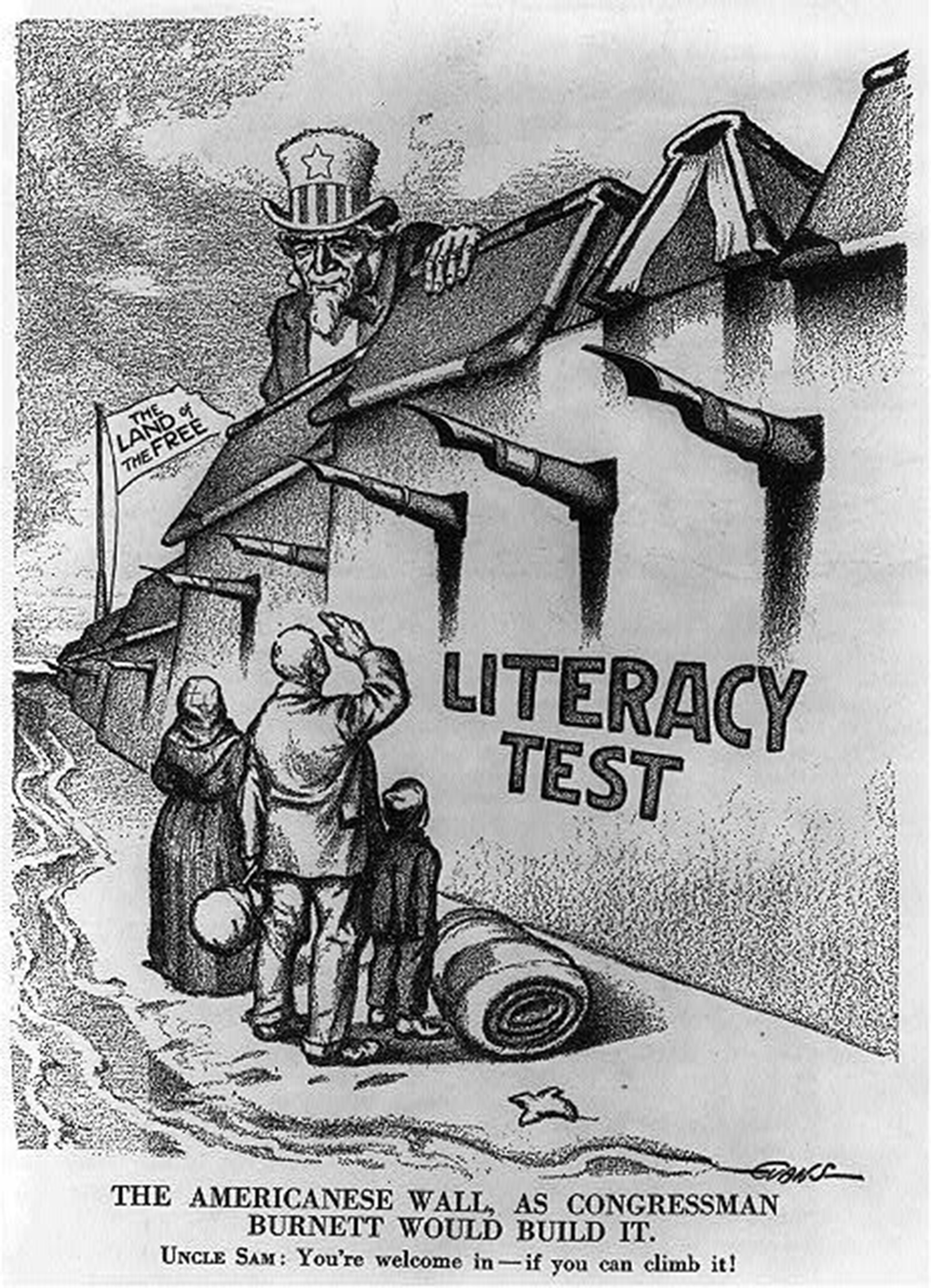

Figure 2. The literacy test that the Immigration Restriction League had long championed as a means of restricting immigration from southern and eastern Europe was finally passed as part of the 1917 Immigration Act, sponsored by Alabama Congressman John Lawson Burnett. In this cartoon, Uncle Sam peers over the “Americanese Wall” built with books and armed with ink pens. Cartoon by Raymond O. Evans, Puck, Mar. 25, 1916. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

During and after World War I, there were many speaking out against immigration. But Madison Grant was the most powerful. The Passing of the Great Race was hugely popular and influential. First published in 1916 with a preface written by noted eugenicist Henry Fairfield Osborn, it went through four editions in five years. The book shaped American public opinion and public policy, most notably in racializing the new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe as inferior and dangerous. In the years leading up to World War I, xenophobia and the argument to restrict immigration went hand in hand with a vigilant nationalism in the United States.Footnote 23

In 1917, Congress passed—over a presidential veto—the Immigration Act of 1917, the epitome of anti-immigrant sentiment in a nation that was then gripped with the hysteria of “100% Americanism” during World War I. The new law barred all foreigners who lacked basic reading ability in their native language and served as the first serious effort to restrict European immigrants. It also imposed increased head taxes and prohibited immigrants with disabilities, diseases, or any characteristics that the state determined to interfere with their ability “to earn a living.” It excluded “polygamists,” anarchists, prostitutes, and those opposed to “organized government.” Lastly, the law created an Asiatic Barred Zone encompassing much of East, South, and Southeast Asia, from which all immigrants would be banned.Footnote 24

The Red Scare of 1919 added to the xenophobia already growing in the country by promoting the idea that foreign ideologies like Bolshevism were being brought to the United States by hordes of unassimilable foreigners who threatened American institutions and ideals. By 1921, The Passing of the Great Race was in its fourth edition, and Grant could claim that his book's purpose to rouse his fellow Americans to “the overwhelming importance of race and to the folly of the ‘melting pot’ theory” had been thoroughly accomplished.Footnote 25 In 1921, Congress passed the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921 to cut immigration, limiting annual admissions to 355,000 and establishing admission quotas based on nationality (known as “national origins”), which privileged immigrants from northern and western Europe and discriminated against those from southern and eastern Europe. Grant could not help but gloat. The “immigration of undesirable races and peoples,” he wrote in 1921, had been stopped.Footnote 26 Three years later, the Immigration Act of 1924 reduced annual admissions to 165,000 and redesigned the national origins quotas to limit the slots available to southern and eastern European immigrants even further. Immigration of “aliens ineligible for citizenship”—a code word for Asians—was also prohibited. No restrictions were placed on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, but two days after the Immigration Act was passed, Congress established the U.S. Border Patrol to enforce immigration law along both the northern and southern borders of the United States.Footnote 27

Through Madison Grant, the Immigration Restriction League, and others, xenophobia thus moved from the extreme to the mainstream of American popular culture, thought, science, and politics, and was legitimized as an engine of federal immigration laws.

Building the Xenophobic State

The second way in which xenophobia drove some of the most important forces shaping the Gilded Age and Progressive Era was through expanding the capacity and power of the nation-state over foreigners outside and inside the United States. It is important to remember that from its founding, American immigration policy was, as Aristide Zolberg put it, one that sought to create a “nation by design.” Americans actively devised policies that shaped the country's overall population and served its goals as a settler colonial nation. Early policies, including colonial and state poor laws that regulated the admission and deportation of destitute foreigners, helped to lay the foundation for federal immigration policy.Footnote 28 The first law to establish modern federal control over immigration was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. This law and the Supreme Court's 1889 ruling on its constitutionality established the United States’ sovereign right to regulate foreigners into and within the nation.Footnote 29 A few months after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, another law, the 1882 Immigration Act, became the nation's first general immigration law, barring “convicts, lunatics, and persons likely to become public charges.”Footnote 30

The Chinese Exclusion Act ushered in drastic changes to immigration regulation and set the foundation for twentieth-century policies designed to inspect and process newly arriving immigrants and control potentially dangerous immigrants already in the country. First, it initiated the establishment of the country's first federal immigrant inspectors. “Chinese Inspectors,” under the auspices of the U.S. Customs Service, were the first to be authorized to act as immigration officials on behalf of the federal government. General immigrant inspectors would later be established under the Bureau of Immigration in 1894.Footnote 31

Second, the enforcement of the Chinese exclusion laws set in motion the federal government's first attempts to identify and record the movements, occupations, and familial relationships of immigrants, returning residents, and native-born citizens through registration documents, certificates of identity, and voluminous interviews with individuals and their families. Section four of the Chinese Exclusion Act established “certificates of registration” for departing laborers. This laborer's return certificate was the first reentry document issued to an immigrant group by the federal government, and it served as an equivalent passport facilitating reentry into the country. Chinese remained the only immigrant group required to hold such reentry permits (or passports) until 1924, when the new Immigration Act of that year issued—but did not require—reentry permits for other aliens.Footnote 32

Eventually, all Chinese residents (not just laborers) already in the country were required to possess “certificates of residence” and “certificates of identity” that served as proof of their legal entry and lawful right to remain in the country. These became the precursors to documents now commonly known as green cards. Any person of Chinese descent, including U.S. citizens, found within the jurisdiction of the United States without a certificate of residence was to be “deemed and adjudged to be unlawfully in the United States” and was vulnerable to arrest and deportation.Footnote 33 No other immigrant group was required to hold documents proving their lawful residence until 1928, when “immigrant identification cards” were first issued to new immigrants arriving for permanent residence.Footnote 34

The Chinese Exclusion Act set another precedent by defining illegal immigration as a criminal offense and specifically naming deportation as the punishment for this offense. It declared that any person who secured certificates of identity fraudulently or through impersonation was to be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, fined $1,000, and imprisoned for up to five years. Any persons who knowingly aided and abetted the landing of “any Chinese person not lawfully entitled to enter the United States” could also be charged with a misdemeanor, fined, and imprisoned for up to one year. Defining and punishing illegal immigration directly led to the establishment of the country's first modern deportation laws as well, and one of the final sections of the Chinese Exclusion Act declared that “any Chinese person found unlawfully within the United States shall be caused to be removed therefrom to the country from whence he came.”Footnote 35 Deportation became further entrenched in the Immigration Act of 1882, the first general immigration law that applied to all aliens. This law provided for the deportation of criminals and further established unlimited federal power (as opposed to individual states) in determining the excludability and deportability of aliens.Footnote 36

Nine years later, the complete federalization of immigration control was achieved through the Immigration Act of 1891. This law placed all immigration regulation in the hands of the federal government under the control of the federal superintendent of immigration in the Treasury Department and appointed federal commissioners of immigration at all major ports. The construction of the immigration station at Ellis Island began soon thereafter.Footnote 37

By 1930, U.S. immigration policy had been transformed from a loose set of policies targeting a few select groups to a broad array of laws that excluded or restricted numerous categories of immigrants. And the federal government had created and expanded the mechanisms not only to sift newcomers at the nation's ports and borders, but also to track them as they moved homes, changed jobs, returned to their homelands for visits, sponsored in family members, and to deport them, en masse, if necessary.

Xenophobia and American Global Power

One last way in which American xenophobia helped to shape key aspects of the Gilded Age and the Progressive era was as a part of America's growing global power and influence. The United States was the first amongst the world's nations to enact racist immigration policies with its prohibition on black immigrants in 1803 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. As American xenophobia grew to target other groups and as immigration enforcement became more exacting, U.S. global leadership in immigration regulation continued to increase in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This happened in two ways. First, Americans actively participated and helped lead some of the transnational and international organizations and networks that promoted and facilitated similar restrictionist immigration policies abroad. In the early twentieth century, American labor leaders traveled to Canada to establish branches of the anti-Asian organizations already active in the United States and helped to incite the anti-Asian riots in Vancouver in 1907. During the 1920s, California newspaperman V.S. McClatchy helped spread the anti-Japanese “Yellow Peril” message through publications in English and Spanish in North and South America.Footnote 38 Eugenicist Harry Laughlin's congressional testimony in the 1920s helped shape the national origins quota system in the United States. Laughlin later teamed up with Cuban colleagues to advance similar immigration policies in Latin America in the 1930s.Footnote 39

The second way that America exerted its global leadership was by example. The United States first helped identify certain populations (African Americans, American Indians, Asians, Mexicans, Jews, southern and eastern Europeans, and Muslims) as globally problematic—as dangerous not only to the United States but to white supremacy worldwide. Then the United States created innovative laws and administrative procedures to exclude, restrict, interrogate, detain, and deport immigrants.

The U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act became a landmark expression of national sovereignty over immigration. Colonies and nations from Victoria and New South Wales (Australia) to Canada, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela all followed with restrictive Chinese immigration laws of their own, building what Aristide Zolberg called the “Great Wall Against China.”Footnote 40 Between 1887 and 1918, countries including the Netherlands, Sweden, Argentina, and Chile asserted their “sovereign right” to exclude other immigrants as well. Venezuela barred all non-Europeans. Haiti, Costa Rica, and Panama denied admission to Syrians. Colombia's law prohibiting the immigration of all “dangerous aliens” was perhaps the broadest.Footnote 41

The domino effect of U.S. immigration policy was not a coincidence. As many scholars such as David FitzGerald and David Cook-Martín have demonstrated, the U.S. immigration regime became a general template or reference point for immigration policy around the world. Over time, countries converged on similar policies even if they had very different levels and types of immigration, political systems, and labor markets. Because the United States was the first to enact such an extensive system of immigration policy, it became the de facto global leader. This was not simply a matter of explicit replication; it was also through inspiration and by example. Many nations started with the U.S. model of xenophobia and racist immigration laws and then reshaped them to serve their own unique purposes.Footnote 42

This tradition of American leadership continued into the twentieth century. The work of global leaders in eugenics like Lothrop Stoddard helped to inform immigration laws throughout the anglophone world. Britain, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand all instituted policies to screen immigrants for their “hereditary fitness,” for example.Footnote 43 In 1930s Germany, the Nazis frequently praised the United States for standing “at the forefront of race-based lawmaking” not only through Jim Crow segregation, but also through its immigration and naturalization laws and the creation of de jure and de facto second-class citizenship for African Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and the subjects of American colonies like Filipinos.Footnote 44 In his unpublished sequel to Mein Kampf drafted in 1928, Adolf Hitler interpreted (and applauded) the 1924 Immigration Act as an effort to exclude the “foreign body” of “strangers to the blood” of the ruling race. The United States had finally cast off its silly prior commitment to the “melting pot,” first by excluding the Chinese, then the Japanese, and then by recommitting itself to being a “Nordic-German” state, he believed. In doing so, the United States became, in Hitler's view, a racial model for Europe.Footnote 45

Madison Grant's explicit racism fell out of favor and scientific racism lost its credibility during and after World War II and the condemnation of Nazi Germany's genocidal regime. Support for liberalizing U.S. immigration laws began in the post–World War II era and peaked during the civil rights movement. By prohibiting discrimination in immigration law, the 1965 Immigration Act represented an important turning point. Nevertheless, xenophobia endured alongside civil rights. This brand of xenophobia—what I call “colorblind xenophobia”—was purportedly race-neutral and was accepted by both mainstream political parties, but was still based on an acceptance and promotion of white supremacy in immigration law and disproportionately impacted immigrants of color.Footnote 46

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a new American xenophobia targeting the Mexican “illegal” immigrant and the Muslim “terrorist” emerged to operate under the cloak of colorblind campaigns for law and order and national security. Part of the larger rollback in civil rights, the growth in mass incarceration, and the domestic fallout from the war on terror, this new xenophobia, including Islamophobia, has been a bipartisan project. And it has spurred laws that limit the freedom of immigrants already in the United States, militarize the U.S.-Mexico border, and sustain a new deportation and detention regime. These policies have impacted not only immigrants and members of minority communities; by broadening the definition of “enemies” in the U.S. war on terror, the boundaries between “immigrant” and “citizen” have blurred. And both groups have become increasingly subjected to new tools and processes of national security measures that undermine key features of American democracy for all Americans.

Today, the U.S. government continues to exert its global leadership in enacting and enforcing racist immigration policies, often in order to serve its own gatekeeping needs. U.S. agencies regularly cooperate with border enforcement agencies in other countries and regions, sharing information, technology, training, and more. The United States has helped shape (and fund) a “Southern Border Program” that aims to regulate migration from Central America into Mexico, and then into the United States. The program was established in 2014 following the arrival of more than 36,000 unaccompanied children, mostly from Central America, who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border over a four-month period.Footnote 47 Under the administration of Donald J. Trump, the U.S. government turned to coercion and the threat of a trade war with Mexico to achieve U.S. immigration policy goals. In the spring of 2018, President Trump reiterated a “get tough” message to Mexico and threatened to send the U.S. military to the border to prevent the so-called “caravan” of Central Americans heading north. The next year, the president threatened to impose tariffs on all goods imported from Mexico until undocumented migration across the southern border ended. At the same time, the administration implemented a “Remain in Mexico” policy that returned tens of thousands of asylum-seekers to Mexico to wait for their hearings in U.S. immigration court and began a “metering” program to limit the number of people who could seek asylum into the United States.Footnote 48

Xenophobia Then and Now

The election of Donald J. Trump to the presidency and voters’ endorsement of his xenophobic and nativistic “America First” campaign represents the latest—and perhaps greatest—turning point in America's long history of xenophobia. From the campaign trail beginning in 2015 to his first official State of the Union address in 2018, Trump has promoted a consistently xenophobic message about immigration. He describes a United States under siege from “open borders” that have allowed “drugs and gangs” to “break into our country” and “pour into our most vulnerable communities.” He warns of “millions of low-wage workers” who “compete for jobs and wages” against the “working poor.” He links the vicious murders of innocent Americans to the migration of unaccompanied children who “took advantage of glaring loopholes in our laws,” a reference to the increased level of asylum-seekers arriving as minors at the U.S.-Mexico border.Footnote 49

Many aspects of Trump's xenophobia are echoes from the past. Like xenophobia from earlier eras, Trump's is rooted in racism. One year into his presidency, for example, the president referred to Haiti, El Salvador, and African nations as “shithole countries” in an Oval Office meeting with lawmakers. His xenophobia also draws on America's long tradition of white supremacy. In the same meeting, he suggested that the United States bring in more people from countries like Norway. In the same State of the Union speech in 2018, Trump stated that “Americans are dreamers too,” a tagline already popular with white nationalists that redeploys undocumented immigrants’ term “dreamer” to refer to (white) American citizens instead.Footnote 50

With increased crackdowns on undocumented immigrants, new bans, and proposals to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border and restrict both refugees and legal immigrants, xenophobia is becoming further entrenched in American law and culture from the highest office in the land. Unfortunately, the long history of American xenophobia shows that Donald Trump is not an exception. Nor is he the sole cause of new xenophobia. He is a consequence of older patterns, an extreme expression of a xenophobia that has become a normal, mainstream, and defining characteristic of America. Trump—with his uniquely undisciplined communications style—has only laid bare the xenophobia, racism, and nativism that has defined America since its founding. In this way, Trump is a twenty-first century Madison Grant propelling the United States country toward a perilous and uncertain future. As was the case during the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, Trump-era immigration policy has already turned the United States toward restriction and deportation.

The Trump era will eventually end. And while many will likely celebrate its demise and a “return to normalcy,” let us not blind ourselves to the fact that regardless of who is in the White House, xenophobia has long been “normal” in the United States, and has been a constant force shaping American life. It has not been an aberration or an exception in our history. It has been a persistent and defining feature.

Rethinking American history as a history of xenophobia reveals just what is at stake today. Targeting the most vulnerable among us, subjecting them to unequal treatment under the law, and denying them full constitutional rights has ended up threatening democratic values and human rights globally. Only by fully understanding the genealogy of xenophobia—along with its causes, expressions, and consequences—can we successfully challenge it. We need to illuminate why and how xenophobia works, who profits from it, and what is at stake.

However, it is equally important to remember that xenophobia has never gone unchallenged. Throughout US history, immigrants and their allies have spoken out against xenophobia in multiple ways. In doing so, they have embraced and embodied the core American ideals and values that xenophobia threatens. During the congressional debates over the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, for example, George Frisbie Hoar, a Republican senator from Massachusetts, gave an extraordinary speech that denounced the discriminatory measure. Hoar, who had been a longtime defender of African American civil rights, Native American treaty rights, and women's suffrage, argued that the exclusion of Chinese from America was nothing more than “the old race prejudice which has so often played its hateful and bloody part in history.” The Declaration of Independence, he continued, did not allow the government to interfere with an individual's desire “to go everywhere on the surface of the earth that his welfare may require.”Footnote 51

The next decade, John Fitzgerald, congressman for the 11th District in Boston, bristled as he listened to his colleagues condemn the “inferior” foreigners being allowed into the United States. He was further outraged when his colleague from Massachusetts, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, introduced a literacy bill in 1896 that would have excluded Fitzgerald's own mother, an illiterate immigrant from Ireland. In a speech on the House floor, Fitzgerald registered his utter opposition to the bill. “It is fashionable today to cry out against the immigration of the Hungarian, the Italian, and the Jew,” he declared, “but I think that the man who comes to this country for the first time—to a strange land without friends and without employment—is bound to make a good citizen.” Lodge reportedly confronted him at the Capitol and asked him, “Do you think the Jews or the Italians have any right in this country?” “As much as your father or mine,” Fitzgerald replied. “It was only a difference of a few ships.”Footnote 52

Writers and playwrights such as Israel Zangwill, Mary Antin, and Carlos Bulosan used their novels and plays to humanize immigrants and appeal to Americans’ commitment to equality. Social workers like Jane Addams worked tirelessly on behalf of immigrants and helped them integrate into American society. The American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born challenged the repression, detention, and expulsion of immigrants beginning in the 1930s and continued its work through the 1980s.

In these ways, immigrants and their allies, along with advocates and everyday Americans, challenged the most pernicious expressions and acts of xenophobia and appealed for justice. Sometimes they were successful. May their examples serve as inspiration to us all who seek to challenge xenophobia in our own time.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the author's 2018 Distinguished Historian Address, presented at the Society for Historians of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (SHGAPE) luncheon at the annual meeting of the Organization for American Historians, Apr. 13, 2018, Sacramento, California.