In jealousy there is more self-love than love.

(La Rochefoucauld [1671] Reference La Rochefoucauld, Blackmore and Blackmore2007: 91)Introduction

‘Compersion’ is what non-monogamous people call the positive feelings about their partner's romantic intimacy with another person. Unlike ‘polyamory’, a neologism meaning many loves, compersion is not a portmanteau term. The story goes that it originated on an ouijia board in a San Franciscan commune (Glossary of Keristan English 1985). Over the past forty years the term has become a staple of discourse between non-monogamous people and has been defined variously as:

An emotion that is the opposite of jealousy. Compersion means to feel joy and delight when one's beloved loves or is being loved by another. (Anapol Reference Anapol2010: 121)

The joy at seeing one's partner(s) happily in love with others. It is not precisely the opposite of jealousy, but close. (Sheff Reference Sheff2014: 20)

Feelings of pleasure in response to a lover's romantic or sexual encounters outside the relationship. (Deri Reference Deri2015: 4)

A feeling of joy experienced when a partner takes pleasure from another romantic or sexual relationship. (Veaux and Rickert Reference Veaux and Rickert2014: 453)

The feeling of taking joy in the joy that others you love share among themselves, especially taking joy in the knowledge that your beloveds are expressing their love for one another. (cited in Klesse Reference Klesse2006: 580)

Acceptance of, and vicarious enjoyment for, a lover's joy. (Anderlini-D'Onofrio, cited in Taormino Reference Taormino2008: 175)

These definitions are my starting point as I work toward a detailed account of compersion. An account is needed because people disagree about the nature of compersion and how it relates to jealousy. For instance, the definitions above risk giving the same label to distinct phenomena. Precision is required if we are to understand whether compersion is valuable and how it can be cultivated. This precision can be attained by carefully distinguishing compersion from the other emotions and experiences lying within its ‘emotional parish’, to borrow Kristján Kristjánsson's phrase (Reference Kristjánsson2018: 75).

Compersion is an emotional ideal for most of the non-monogamous community (Sheff Reference Sheff2014: 68; Deri Reference Deri2015: 6). To other people, however, the idea is unfamiliar and controversial. Most people are committed deeply to monogamy as a structure of romantic life, and monogamous culture makes little provision for members of couples to flourish intimately with other people. Even people who contest monogamous norms are not immune to jealousy. Unsurprisingly, therefore, jealousy is often portrayed as ordinary, healthy, and useful. Jealousy also has philosophical advocates, with some even arguing it is a virtue. Against this background of monogamous norms, folk psychology, and philosophical argument, jealousy can seem like a solid feature of romantic life; something to be managed, not removed. When jealousy looks secure and even reasonable, compersion looks fragile and even outrageous.

I will make the case for compersion to build upon and vindicate the insight of the non-monogamous community. I will argue that compersion is an emotion that focuses on the flourishing of someone one cares about as a result of that person's interaction with other people. Compersion is therefore not akin to pride, vicarious enjoyment, or masochistic pleasure. People can cultivate compersion by softening their propensity to be jealous and by learning to pay attention to the flourishing of others. The former requires them to tackle their possessiveness and the beliefs that enshrine their entitlement and to temper their vulnerability. The latter requires sustained effort to redirect their attention. Both processes involve direct reasoning and indirect emotion management. I end the article with a critical examination of jealousy and a discussion of compersion's value. Jealousy should not be cultivated as an emotional disposition. First, its instrumental benefits are minor, unstable, and have to be traded against the harms of aggression. Second, arguments that conclude that jealousy is a virtue rest on contentious premises and overlook the practical question as to whether jealousy and compersion could be cultivated together.

Although ‘compersion’ was coined to describe the feelings of non-monogamous people, it is not confined to romantic life. Compersion also arises between friends, siblings, and colleagues. I focus on compersion in romantic contexts because it is arguably harder to feel toward a romantic partner as opposed to a friend, say, because of the social norms and ideals surrounding exclusivity, desire, and love; norms that exacerbate one's vulnerabilities and sense of entitlement. My argument will apply, however, with little modification to compersion in other contexts.

1. Compersion

1.1 Preliminaries

I shall not presuppose a specific theory of emotion but I will make the following assumptions. First, emotions are complex and typically involve a blend of cognitions, evaluations, feelings, and motivations (Ben-Ze'ev Reference Ben-Ze'ev2000). Each of these features, and the emotion overall, can be valenced, that is, described as positive or negative (Colombetti Reference Colombetti2005). Second, emotions are primarily distinguished in terms of their evaluative aspects. My fear of a snake, for instance, is a response to a slithering object, which I evaluate as dangerous and which I want to shy away from. This fear contrasts with the exhilaration of a herpetologist upon seeing the snake. For her, the snake appears of exciting scientific value. The herpetologist may have similar bodily feelings to me, however, such as a racing heart and breathlessness. The fact that similar feelings can be features of the different emotions of fear and exhilaration explains why the evaluative aspect of emotions is useful in characterizing emotions. Some philosophers argue that emotions resemble perceptions rather than judgments (Roberts Reference Roberts2003; Tappolet Reference Tappolet2016), whereas others dispute the perceptual comparison and argue that feelings are themselves imbued with evaluative intentionality (Goldie Reference Goldie2000; Helm Reference Helm2001). For my purposes we need only think that emotions are a complex of feeling and evaluation.

The evaluative aspects of emotional experiences are shaped by someone's concerns and desires. Many emotions, including jealousy and compersion, would not arise if people did not care about themselves, about their reputation or avoiding anxiety, say, and if they did not care about other people. There is room for debate about the nature of cares and how emotions are anchored in them. I favor Robert Roberts's ecumenical definition of a ‘concern’ that encompasses ‘desires and aversions, along with the attachment and interests from which many of our desires and aversions derive’ (Reference Roberts2003: 142).

1.2 The Emotion of Compersion

Compersion is an emotion even though its name is not widely known. People have attempted to name similar phenomena before, however. The obsolete English term ‘confelicity’, for example, was used by psychologists in the early twentieth century, occasionally as a translation of the German term ‘Mitfreude’, which itself is sometimes used to denote sympathetic joy (Saunders and Hall Reference Saunders and Hall1900: 581; Gesell Reference Gesell1906: 467). Some psychologists have recently used the neologism ‘synhedonia’ in a similar way (Royzman and Rozin Reference Royzman and Rozin2006).

Compersion also resembles the Latin verb ‘collaetare’, which refers to the activity of ‘rejoicing with’ others who rejoice (Rosenwein Reference Rosenwein2016: 102), and the Sanskrit term ‘mudita’, which describes one of the four important mental attitudes or brahma viharas that a Buddhist should cultivate. Mudita is often translated as ‘sympathetic joy’ or ‘joy with others’ (Miller Reference Miller1979).

In the philosophy literature, Aaron Ben-Ze'ev devised the term ‘happy-for’ to describe a positive emotion in response to the good fortune experienced by others (Reference Ben-Ze'ev2000: 353). This notion bears some resemblance to the space made by Aristotle, in the Rhetoric, for a positive emotion in response to ‘deserved good fortune’ as a complement to the other desert-sensitive emotions of compassion, indignation, and satisfied indignation (Aristotle Reference Waterfield and Yunis2018: 82 [1387b30]). There is no word for this in ancient Greek, so Kristján Kristjánsson terms this nameless emotion ‘gratulation’ (Kristjánsson Reference Kristjánsson2018: 25). Unlike the use of the terms confelicity, Mitfreude, synhedonia, collaetare, mudita, and happy-for, gratulation only encompasses emotional responses to deserved good fortune. When I discuss compersion's value, I will ask whether it should be thought of in a similar way.

People might ask why there is no common term for a positive emotion toward the happiness of others. An answer might lie in research that suggests people's engagement with the world is structured by an entrenched and broad negativity bias, where they give greater weight to negative events and possibilities than to positive ones (Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001; Rozin and Royzman Reference Rozin and Royzman2001). Given this bias, it is unsurprising that languages hypocognize positive emotions (Levy Reference Levy, Shweder and Le Vine1984).

Fundamentally, compersion is sensitive to how people fare; in particular, to their flourishing with other people. (Flourishing rather than happiness or taking pleasure in a relationship because a partner can be thriving even if the partner's own feelings are more neutral.) Someone feels good because their partner's other relationships contribute to their partner's life by harmonizing with their values or by offering intrinsically valuable goods.

To avoid misunderstandings, note that when people are compersive, the following obtains. First, they feel positive, they do not just believe that others fare well. Second, their positive feelings accompany a positive construal of the situation; compersion is unlike recalcitrant amusement (‘I should not be laughing, but . . .’). Third, they feel compersion about the situation of everyone involved; compersion does not just focus solely on their beloved. Compersion, like jealousy, focuses on a partner and a third party. The salience of these objects will vary in terms of their causal role in eliciting compersion and in their centrality to compersion's evaluative and cognitive aspects. Some people know little about their partner's partners, whereas others are much closer. Fourth, someone can be compersive without wanting what other people have. Compersion is therefore not ‘vicarious enjoyment for, a lover's joy’ (Anderlini-D'Onofrio cited in Taormino Reference Taormino2008: 175). People often pursue non-monogamy because of attractions or interests their beloved does not share. An asexual person, for example, may feel compersive when their allosexual partner has a sexual relationship with someone else. (Moreover, as many a pressured child athlete knows, people can enjoy things vicariously even when the active person does not.) Finally, when compersive, people feel good about a situation that the people involved also think is good. This condition distinguishes compersion from feelings like pride, because people may be proud that someone is non-monogamous without understanding how that person feels. Unlike pride, compersion requires people to understand the state of mind of others.

It is worth clarifying this last point. The ability to understand someone's state of mind has been called empathy, but many phenomena share this name (Batson Reference Batson, Decety and Ickes2009). The ability I have in mind, which is sometimes called ‘cognitive empathy’ (Eslinger Reference Eslinger1998), is not akin to having the same emotions as another person (Sober and Wilson Reference Sober and Wilson1998) or to having feelings for them. Similarly, understanding someone's state of mind may require, but is distinct from, processes of projecting/imagining oneself into another's situation (Lipps Reference Lipps1903; Batson Reference Batson1991) or imagining how one would fare in their shoes (Darwall Reference Darwall1998). Often it is obvious how others feel.

Compersion requires cognitive empathy because compersion reflects how other people flourish, and to understand whether another is flourishing is partly to understand that other's state of mind. Compersion also presupposes that someone can have feelings for another person. However, compersion does not require the other phenomena labelled empathy. A compersive person's emotional response only has to be congruent to that of the people it is about. The joy one feels toward the flourishing of others is not identical to how they feel, in quality and intensity. Similarly, my definition of compersion as a response to flourishing, rather than to another's joy, accommodates the fact that a flourishing person's emotions can change without the compersive person's feelings having to change, as they would do if compersion required them to mirror others’ emotions. Relatedly, it is not a necessary feature of compersion that one projects oneself into or imagines oneself in another's position as this would make it akin to vicarious enjoyment: a comparison I contested above.

Although compersion has been used to describe non-monogamous life, it is not confined to that context (Deri Reference Deri2015: 33). Monogamous people may feel compersion toward their ex-partners. Siblings, friends, colleagues, and sporting rivals may feel compersion toward each other when they flourish. Important contingent differences between social contexts will remain, however. Romantic and platonic relationships, for instance, are subject to different social norms and expectations, a point that will be relevant when I consider what is required to cultivate compersion.

2. Jealousy Transformed?

In this section, I distinguish compersion from a form of jealousy with which it may be confused. This distinction is vital if someone is to understand how to foster compersion and why it is valuable.

2.1 Jealousy

I endorse a widespread interpretation of jealousy as the emotion of being pained by a perceived threat from a third party to the attention of someone one cares about, and to which one feels entitled (Farrell Reference Farrell1980; Neu Reference Neu2000: 47; Ben-Ze'ev Reference Ben-Ze'ev2000: 289–97; Goldie Reference Goldie2000: 225; and Roberts Reference Roberts2003: 257–61). The role of a rival distinguishes jealousy from fear of loss or disappointment over loss; the sense of entitlement over the threatened affection distinguishes jealousy from envy as the affection of the other person is not simply something one wants but does not have, but something one thinks one ought to have.

The loose definition can be refined. It suffices to note that the nature of the pain in jealousy may vary in form and intensity, and there is disagreement about the nature of this pain. Kristjánsson, for example, thinks jealousy involves indignation (Reference Kristjánsson2018: 102–21). I favor an ecumenical approach that recognizes that at times jealousy feels like anger and at other times more like fear, sadness, or grief (e.g., Goldie Reference Goldie2000; Roberts Reference Roberts2003: 258). We should also note that what constitutes a threat will fluctuate between contexts and cultures; although the notion of a rival is suggestive of human agency, this may not be necessary. The care and affection involved in jealousy are not inherently sexual or romantic (someone can be jealous if his or her partner's violin gets all the attention), and the claim on another may fall short of socially supported entitlement.

Like compersion, jealousy typically has a primary and secondary object. Since people are concerned about the alienation of their partner's affections, the partner will typically occupy the main focus of the emotion, but partner and rival can occupy either role, or jealousy may focus on them both (Roberts Reference Roberts2003: 257).

At first blush, compersion and jealousy have a similar structure. They have a dual object and are elicited by situations where other people benefit from the attention of a person one cares about. The emotions seem to differ in terms of their affective valence: compersion feels good and jealousy bad. Together, these facts—similar structure, similar eliciting conditions, divergent felt quality—could make us think that compersion arises when jealousy is modified in a certain situation.

2.2. Jealousy and the Paradox of Horror

In an argument from analogy, Ronald de Sousa (Reference De Sousa, Grau and Smuts2017) argues compersion arises when jealousy is ‘transmuted’ to gain a new affective valence. He compares attempts to foster compersion with the so-called paradox of horror and with the pain syndrome asymbolia where people feel pain but are not troubled by it. To discuss the latter would raise thorny interpretive issues about philosophical analyses of asymbolia and the adequacy of his analogy. De Sousa endorses Nikola Grahek's (Reference Grahek2007) analysis of asymbolia, which has been forcefully critiqued, to my mind at least, by Colin Klein (Reference Klein2015: chapter 11).

I will focus, instead, on de Sousa's appeal to the paradox of horror. The apparent paradox centers on aesthetic contexts where people seem to enjoy depictions of situations that would normally horrify them. On this view, the revision of attitudes about monogamy to enter a new romantic context functions in a similar way to the theatrical setting and narrative structure of a play. Just as an aesthetic context helps people enjoy William Shakespeare's brutal revenge play Titus Andronicus, whose chaotic violence they would ordinarily abhor; changed attitudes toward romance help people feel compersive for their partner's intimacy with other people, which would normally generate jealousy.

De Sousa is right that to foster compersion people need to revise their attitudes about romance, but his argument from analogy misleads and obscures an important distinction between compersion and what I will call masochistic jealousy. To appreciate this distinction let us again consider Titus Andronicus. People who watch the bodies amassing on stage would agree that the play depicts cruelty. Since most theatergoers are not sadistic, they will experience a range of negative emotional responses to these scenes, not unbridled pleasure. These occasions are puzzling because people appear to enjoy the play despite the depictions of cruelty and partly in virtue of their resulting negative feelings.

How the enjoyment of horror is possible remains a matter of dispute (Smuts Reference Smuts2009) but instances of compersion are not like this. The crucial difference between knowing their beloved flourishes with other people and enjoying theatrical barbarity concerns the evaluative aspect of a person's emotional reactions. When people are compersive, they feel good about a situation which their emotion also construes as good; affective and evaluative valence align. In watching Titus, the evaluative and affective aspects of people's emotions diverge. While they might overall enjoy the tumult of anxiety and horror as Titus progresses, they never waver in their negative construal of murder and mutilation. Here, affective and evaluative valence diverge. Any plausible analysis of the enjoyment of horror must explain it in terms of these mixed valences.

The aesthetic context of tragic theatre does not alter how people emotionally evaluate cruelty. Yet when non-monogamous people embrace revised narratives about the nature of romance, this does alter the evaluative aspect of their emotional responses to their lover's flourishing with other people. Their partner's flourishing does not simply make them feel good, overall, but it is something they construe as good. Of course, much needs to be said about what such a context involves and whether occupying it is sufficient for these emotional changes, but the emotional shift from jealousy to compersion is not like the change at the heart of the paradox of horror.

2.3 Masochistic Jealousy

There are situations, however, where people do manage to modify the valence of their jealousy in a way that accords with de Sousa's analogy with the paradox of horror. Certain kinds of erotic context and framing narrative allow people to toy with jealousy, invoke it in others, and find it arousing (Perel Reference Perel2017: 99–100; cf. Farber Reference Farber, Boyers and Farber2000: 191). Nichi Hodgson's article in Men's Health magazine, ‘Use Jealousy to Improve Your Sex Life’ (Reference Hodgson2014), offers a representative example of popular psychological perspectives on erotized jealousy. She writes, ‘we all feel jealous from time to time and playing with those feelings can be exciting. In ‘jealousy play’, the aim is to push your partner to the edge of erotic distance from you, before drawing them back again—more lustful than ever.’ Jealousy is also central to some manifestations of the cuckold fetish and in other fantasies of humiliation or displacement (Block Reference Block and Blackwood2015). I will call these experiences masochistic jealousy because like other kinds of masochistic pleasure, from probing a wobbly tooth, endurance running, or aspects of BDSM, the negative feelings involved play a constitutive role: without them, the experience would not be the same or enjoyable in the same way. Colin Klein argues that masochistic experiences border on the unbearable but are nevertheless pleasant because they are novel, afford opportunities for self-control, and promote self-growth (Reference Block and Blackwood2015: 178). Masochistic jealousy fits Klein's model.

2.4 Between Jealousy and Compersion

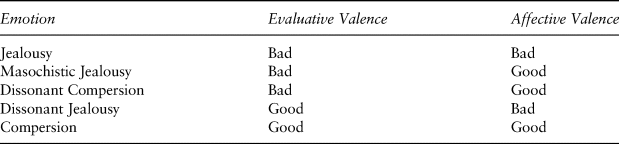

In distinguishing between compersion and masochistic jealousy we are better placed to understand how jealousy may give way to compersion and why compersion is valuable. I shall focus on the example of individuals emotional response to their partner's relationship with another person and also only consider the affective and evaluative valences of that response, therefore neglecting the beliefs and desires associated with the emotion. With this in mind, consider the following schema (Table 1).

This table charts a range of emotional responses to the situation. What I call ‘dissonant jealousy’ and compersion have the same evaluative valence; they present the extra relationships of a person's partner's as good. But these responses differ in terms of how they feel.

At the heart of dissonant jealousy is a tension between an individual's evaluation of their partner's flourishing with another person as good and their lingering negative feelings. Compersion feels actively good and is akin to joy. (I use ‘dissonant’, rather the standard notion of recalcitrant emotions (Brady Reference Brady2009), to capture a tension internal to an emotional experience. For example, dissonant fear of flying would involve the awareness that flying is dangerous combined with a nascent feeling of exhilaration. A recalcitrant fear of flying arises where we evaluate flying as dangerous and feel awful despite believing that flying is safe.)

Jealousy, masochistic jealousy, and dissonant compersion all involve negative evaluation of a partner's relationship. But these emotional responses also differ in terms of their felt quality. Jealousy is often painful and fraught. Masochistic jealousy and dissonant compersion, in contrast, feel good, but they do so in different ways. Depending on the final analysis of masochistic experiences, masochistic jealousy is likely to feel good precisely because it feels partly bad. Dissonant compersion, however, feels good despite the negative evaluation.

Due to their internal tensions, dissonant jealousy and dissonant compersion are complex experiences that can cause difficulties in relationships. Both emotional experiences are liable to be accompanied by metaemotions like surprise or sheepishness. Dissonant jealousy can also issue in passive aggression where there is a tension between individuals’ purportedly supportive approach and the way their negative feelings manifest in their behavior.

As the table above makes clear, there are several ways to fail to be compersive or jealous. We should therefore resist claiming that compersion and jealousy are opposites. Talk of emotional opposites is unhelpful because compersion will have a different opposite when we focus on its affective, evaluative, motivational, or overall moral valence.

Acknowledging this complexity helps us consider what is required in order to foster compersion: a question I answer in the next section. I grapple with this issue before asking whether compersion should be cultivated because a critic, in an application of ought implies can, might argue that people should only cultivate emotional dispositions they are able to cultivate, that compersion is psychologically implausible, and therefore that compersion ought not be cultivated. By offering a simple recipe for cultivating it, I hope to demystify compersion and show that it is readily achievable.

In section 4, I examine the value of compersion. Here it suffices to point out that if we do not distinguish compersion and masochistic jealousy and continue to regard compersion as an emotion that differs from jealousy only in terms of affective valence, then the value of compersion would seem to lie only in the fact that it feels good to the compersive person. To many people, especially non-monogamous people who praise compersion, this explanation of compersion's value is inadequate because at first blush the value of compersion lies in how it orients us to the flourishing of other people.

3. Cultivating Compersion

3.1 Preliminaries

The relationship between compersion and jealousy is complicated. People can respond in several ways to situations where a person they care about flourishes with others. Since avoiding jealousy is not the same as being compersive, two processes are typically required to cultivate compersion: (1) weakening jealous tendencies and (2) learning to attend to and appreciate the flourishing of others. These processes are neither necessary nor sufficient to experience compersion because some people may be effortlessly compersive and others may never fully outwit jealousy.

In considering the cultivation of compersion I am focusing on ‘affective dispositions’, not episodic emotions (Deonna and Teroni Reference Deonna and Teroni2012: 8). Are there general features that lead to the emergence of compersion as a settled disposition? As with any emotional work, like trying to be less angry, someone can progress toward becoming compersive while still experiencing episodic lapses into jealousy.

3.2 Why Does Jealousy Arise?

If we are to understand how to address jealousy, we need to understand why it arises. In the literature about jealousy, two core factors are often mentioned: vulnerability and entitlement. Some theorists think jealousy is underpinned by just one of these features. Jerome Neu, for example, thinks ‘for jealousy to exist all one needs is vulnerability’ as ‘one need not think one has a right to someone else's love in order to fear its loss’ (Neu Reference Neu2000: 57). His story of the origins of jealousy runs from attachment to possessiveness to anxiety, therefore neglecting the role of entitlement. For Davis (Reference Davis1936) and Robinson (Reference Robinson1997) jealousy rests on entitlement. As will become clear, however, both vulnerability and entitlement underpin jealousy. Only in adopting this approach can we understand why jealousy often resembles indignation not just panicked sadness, why entitlement is so entrenched, and why only addressing entitlement will rarely be sufficient to quell jealousy.

3.2.1 Vulnerability

Human vulnerability is complex, and this is not the place to account for it fully. People are vulnerable because of their embodied nature and their different capacities and social, political, and legal status (Mackenzie et al. Reference Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds2014). A dimension of vulnerability of relevance to jealousy, however, is people's broad dependence on others (Kittay Reference Kittay2013). As infants, people become attached to other people, that is, arationally oriented to them as sources of security (Bowlby Reference Bowlby1997, Reference Bowlby2005; Wonderly Reference Wonderly2016).

The attachment bond has three significant behavioral manifestations: the maintenance of proximity to an attachment figure, returning to the attachment figure as a safe haven, and using the attachment figure as a secure base (Hazan and Shaver Reference Hazan and Shaver1994). Infants, for instance, want to be close to their parents, return to them when afraid, and use them as a safe point of reference when exploring and learning. Attachment bonds structure adult relationships too as people turn to their friends and romantic partners for support (Hazan and Shaver Reference Hazan and Shaver1994; Feeney and Noller Reference Feeney and Noller1990; McCarthy Reference McCarthy1999).

More broadly, people's self-conception is highly relational because the roles that structure their practical activity, like being a teacher or parent, require complementary roles, like pupil or child, and some aspects of identity appear to presuppose the existence of supportive human practices and institutions (Lindemann Reference Lindemann2014). Many of the concepts and ideals people use to evaluate themselves and their actions also require them to compare themselves to other people.

Dependence is double-edged. One the one hand, contact with others brings people pleasure and contributes to their self-esteem, self-knowledge, and personal flourishing. On the other hand, dependence makes life risky. Because people have attachment bonds with others, their comfort and confidence can depend on those others’ availability and presence. Yet from infancy on, people experience their impotence as they are abandoned or harmed. These experiences can destabilize people's lives as they lose practical support and pleasurable company; such experiences may even destroy a person's sense of self depending on the kind of attachment (Neu Reference Neu2000: 63). People are vulnerable because of this dependency and often anxious when it becomes salient as it often does in romantic relationships where their connection to others can feel contingent and fragile.

3.2.2 Possessiveness and Entitlement

Managing dependence on other people is challenging. A widely accepted ideal of personal relationships is to balance the capacity for intimate emotional bonds with personal resilience and independence. Intimacy allows people to access, enjoy, and benefit from relationships and attachment to others; resilience allows people to navigate periods of isolation and ambivalence.

This balance is elusive for many reasons. Some of these reasons concern the lifecycle in general. Perhaps people's adult relationships have been shaped by the patterns of attachment grounded in their infancy. For example, attachment theorists describe different ‘styles’ of attachment to capture differences in how individuals behave to an attachment figure (Holmes Reference Holmes2001: 8). Around 35 percent of infants are ‘insecurely attached’, and this may shape later relationships (Holmes Reference Holmes1993: 432). Or perhaps traumatic personal events—bereavement, abandonment, abuse—altered individuals’ experience of intimacy. Factors like these can generate a reluctance or inability to form close relationships or can underpin sustained possessiveness whereby someone is overly reliant on the proximity and support of others.

Even reasonably secure people with little experience of trauma or tragedy will encounter stressors in life that undermine their resilience and confidence. The onset of illness, breakups, unfriendly workplaces, social isolation, disappointing friends, and so on, can knock people off balance, making them possessive for a time.

3.2.3 Entitlement

Possessiveness describes patterns of behavior and emotion in relationships. These patterns are to be distinguished from the normative attitudes aimed at justifying them, attitudes I shall call entitlement. Entitlement has two strands. First, individuals are entitled when they believe that they are justified in being possessive, that they have a legitimate complaint if they lack extensive proximity, attention, and support from others. Second, entitlement can structure people's beliefs about the character of the attention and support they receive from others, namely, that it is exclusive (not offered to others) or more extensive.

Entitlement is supported by a broad nexus of socially sustained norms and ideals, such as visions of romance and the good relationship, gender stereotypes, and notions of wellbeing and emotional health. These norms and ideals vary both within and across historical periods and social contexts, but when norms of entitlement are entrenched, they contribute to an environment that is not conducive to resilient, secure intimacy and where possessiveness is harder to avoid.

These norms and ideals do not ensnare everyone equally. For example, in societies shaped by patriarchy and misogyny, male entitlement towards the attention of women is rife. In turn, these norms can be amplified by racism and ableism, as when Asian women are viewed as subservient (Kim Reference Kim2011) or disabled people are viewed as lucky to have partners (Gill Reference Gill1996), such that entailment is manifested more by certain groups, for example, by able-bodied white heterosexual men.

Not everyone who is possessive is entitled. Infants can be possessive without having any beliefs about whether that is justified. Adults can be recalcitrantly possessive if they desire excessive attention while recognizing that their desire is not justified.

There is room for debate about what constitutes extensive proximity, attention, and support in the context of a relationship and about what constitutes sufficiently special attention. All romantic relationships require care, expectations, and norms of conduct. I cannot settle the question of what these are, however, and the notion of excess may be partly relative to individual relationships. (I write ‘partly’, not ‘wholly’, because people may commit to conceptions of entitlement that violate broader ethical constraints, such as a relationship where one person is fully subservient to the other.) Instead I am appealing to the intuitive distinction between a legitimate expectation of a partner's attention and support and its excessive forms. Violations of a legitimate expectation of care and attention can justify anger and indignation.

3.2.4 The Tripartite Underpinnings of Jealousy

Vulnerability leads to possessiveness, which is justified by entitlement. Taken together, these features underpin jealousy. To focus solely on vulnerability makes it hard to see why jealousy can have an angry edge; to focus solely on entitlement makes it hard to see why jealousy can engender panic rather than plain indignation.

We can better understand how to tackle jealousy if we view entitlement as a veneer over possessiveness, which in turn is a response to felt vulnerability. De Sousa's view, for instance, only captures half of this story. Although he rightly stresses the importance of reframing someone's beliefs about romantic life in order to address jealousy, his entitlement-busting view neglects the extent of individuals’ vulnerability and how vulnerability manifests in possessiveness. Because entitlement and vulnerability can diverge and since vulnerability, in particular, is often anchored in attachment that is resistant to direct reasoning, any successful attempt to tackle jealousy must be two-pronged.

3.3 Tackling Jealousy

Jealousy is a key barrier to being compersive. Other emotions and traits play a role too. Envious, hateful, or insensitive people will also struggle to be compersive, for instance, but jealousy is referenced most often. To address jealousy, people must interrogate their entitlement, and they must take steps to confront and manage their vulnerability. In practice, these distinct tasks intertwine.

To understand entitlement, someone must reflect on romantic concepts and ideals like commitment and exclusivity, to consider whether they endorse their prevailing social interpretations (Finn Reference Finn2012). But to grasp these concepts fully, someone must reflect holistically. To consider commitment, for example, they must contemplate communication, honesty, and power. In turn, to interrogate power is to consider social structures, identities, and norms, and to look at notions of consent, autonomy, misogyny, race, ability, and gender, and so on.

More personally, individuals must consider their expectations and boundaries (Barker Reference Barker2012). What do they want from a romantic relationship, and why do they want that? Are they beholden to social archetypes or personal quirks? Are they too dependent on others? What triggers their insecurity, and how can that be managed? What affirmation do they want from a partner?

Reflection cannot completely assuage jealousy because vulnerability originates in arational attachments and ongoing dependency, but we can tame jealousy's worst manifestations through indirect emotional management. In this sense, confronting vulnerability is like confronting fear: explicit thought only takes us so far. When I started rock climbing, for instance, I knew I was (relatively) safe, but I was nevertheless afraid. My fear was resistant to reasoning; indeed, it was often supported by my reasoning. Over time, however, I was able to reduce my fear by using common techniques: incremental exposure to heights, practicing controlled falls, breathing deeply to calm anxiety, and surrounding myself with supportive people.

Vulnerability can be addressed in a similar way. Imagine a previously monogamous couple beginning to explore polyamory. Like a scared climber, they can try to tackle their vulnerability. They may slowly expose themselves to situations where jealousy looms to foster resilience and practice good communication; they might talk honestly about their new romantic life to make it seem less threatening because jealousy, like fear, thrives on uncertainty; they can notice how they are gripped by particular thought patterns—‘what if she never comes back’— and alter their focus by seeking reassurance, and they can strive to maintain a nurturing home and community by talking to friends, make time for regular conversation, rethink how they organize their personal space, and practice rituals of affirmation and love. These practices are discussed frequently in self-help books for non-monogamous people (Barker Reference Barker2012; Mirk Reference Mirk2014; Taormino Reference Taormino2008; Veaux and Rickert Reference Veaux and Rickert2014), and draw upon on cognitive behavioral therapy and other forms of emotion regulation (Gross Reference Gross2013).

3.4 The Flourishing of Others

The second process that helps people foster compersion is that of attending to the flourishing of other people. It is one thing for them to stop ruminating on threats to themselves and quite another to actively appreciate the flourishing of other people. Therefore, alongside efforts to tame jealousy, people also need to cultivate what Iris Murdoch called a ‘patient, loving regard’ toward other people (Reference Murdoch2001: 39). This slow endeavor—part active reflection, part indirect nurturance—arguably involves moral imagination in several ways.

First, individuals can redirect their attention by asking of a situation: What does this experience mean to their partner and the other person? In focusing on these others’ good, in the plural, they are less likely to focus on their beloved's flourishing in a self-interested way.

Second, people will need to think carefully about when and why they view other people as rivals. People can be rivals: they can disregard someone's interests, downplay their importance, and seek to intrude upon and undermine their existing relationships. (Incidentally, such people are often motivated by their own jealousy.) However, I suspect it is rare that people encounter many actual rivals. Individuals regard others in this way and view social situations as competitive because of the prevalent social norms and ideals of the relationship and romance, which rarely portray nonexclusive forms of affection and concern. This instinctive response can be resisted if people avoid assuming another person is malicious or threatening merely in virtue of the fact that this person is a third party.

A way to do this, finally, is to think more richly about other people. People's quick, stereotypical, appraisal of another person is liable to dissolve when they come to appreciate that person's interests, personality, distinct history, and point of view. Since it is hard to feel good for people who are portrayed poorly, the ability to think empathetically is part of the required imaginative shift to cultivate compersion.

4. Compersion's Value

To foster compersion people must tackle their propensity to be jealous. A critic might agree that this is indeed part of how compersion is fostered but argue that people should not undertake this task because jealousy is valuable. If jealousy is valuable, people should not try to tackle their propensity to feel it.

In this section, I contest this line of argument. I will assume that jealousy often responds to the real possibility that people may lose the affection of someone their care about due to third parties. The more interesting issue concerns the overall value of jealousy. Recent defenses of jealousy as a disposition have focused on its instrumental and moral value.

These defenses are weak. In many cases compersion can play a similar instrumental role as jealousy with clear moral advantages. This is not to deny that some episodes of jealousy may occasionally be useful. Furthermore, even if jealousy is valuable, this does not preclude compersion also being of value, which raises questions about how the two emotional dispositions relate to each other and whether they can be actively cultivated at once. After considering these questions I will conclude that of the two dispositions, compersion is preferable. I think this conclusion applies to all relationships. However, it is conceivable that the value of jealousy and that of compersion may depend slightly on the kind of relationship in which they appear. Variables may include the extent to which the relationship involves attachment bonds and the extent to which the relationship is fragile or easy to leave.

4.1 Jealousy's Instrumental Value

Jealousy is often ascribed a range of instrumental benefits, particularly within the context of close relationships. Like clouds heralding rain, jealousy has been regarded as a sign that people care about their beloved (Neu Reference Neu2000: 63). This sign is purportedly useful for the beloved as they know their affection is cherished, but also for the jealous person, as their emotions help them realize how much they care about the beloved. This latter idea supposedly explains why some people seek to invoke jealousy in others. Experiences of jealousy are supposed to have other benefits. Perhaps the emotion acts as an erotic catalyst (Perel Reference Perel2017: 99–100), or it stops people becoming indifferent to each other (Ben-Ze'ev Reference Ben-Ze'ev2000: 324; Toohey Reference Toohey2014: 190), or it strengthens an existing relationship (Kristjánsson Reference Kristjánsson2002: 160) or promotes reflection (Pines Reference Pines1998: 199). If people value these various ends, then they have reason to value jealousy even if they accept that it can be painful in other ways.

I concede that jealousy sometimes functions in these ways. But should it be cultivated as a disposition? To answer that question, I must ask several other questions. First, is the connection between jealousy and these valued ends fragile? Second, is jealousy harmful or associated with negative outcomes people have reason to avoid? Third, are there other emotional dispositions which could serve the same ends? All three questions have affirmative answers.

To begin with, experiences of jealousy are volatile. In some people, they may invoke awareness of affection, prompt reflection, and improve relationships, but other reactions are equally likely. Jealousy can enflame anger and fuel blame, cause panic, and paralyze reflection; it can leave people feeling pathetic and wronged. Jealousy is hardly a universal aphrodisiac. These diverse reactions show that much has to go right if jealousy is to be beneficial. There is no clear connection between feeling jealous and flourishing relationships.

Second, there is evidence to suggest jealousy is directly connected to aggression and cruelty (DeSteno et. al Reference DeSteno, Valdesolo and Bartlett2006; Brainerd et al. Reference Brainerd, Hunter, Moore and Thompson1996). If this is correct, then any instrumental benefits of being jealous would have to be weighed against the potential for these harmful behaviors. Avoiding harm takes priority within close relationships where intimacy can exacerbate cruelty.

We can also ask why jealousy might act as a signal. The reason is that many people struggle to understand and communicate their feelings within intimate relationships. Not only do romantic ideals generally valorize subtle and implicit communication, but this is a gendered problem because emotional introspection and articulacy are not central to masculine ideals. But these norms and ideals and the inarticulacy they foster should be contested. After all, there is an easier and kinder way for people to let others know they care: tell them.

There is an additional ironic tension here, too, for the people best placed to reap instrumental benefits from jealousy without being aggressive, people who are prompted to reflect, are arguably those who are already well placed to reflect on their relationships, that is, emotionally astute people who can manage anger and who are supported by others. In other words, the instrumental benefits of jealousy are most readily available to the people who need them least.

Finally, compersion also offers the purported benefits of jealousy. People's compersion vividly signals that they care about another's flourishing, that they are not overly entitled, and that they are secure in their affections. Compersion does so, moreover, without the threat of aggression. Compersion also enriches relationships since positive emotional involvement in the flourishing of others spreads good feelings (Fredrickson Reference Fredrickson2013).

4.2 Jealousy and Mental Life

Another way to defend the value of jealousy is to look at its broader role in mental life. Some philosophers think jealousy plays an important developmental role and underpins aspects of personhood (Neu Reference Neu2000; Kristjánsson Reference Kristjánsson2002: 165). The general idea is that experiences of jealousy enable people to distinguish themselves from others through the policing of their entitlements by a kind of emotional assertion.

These views are prone to the genealogical fallacy. Although jealousy may play a developmental role in the formation of personhood, that fact does not speak to jealousy's continuing value. To avoid this worry, jealousy would have to be of ongoing importance.

Peter Goldie offers such a qualified defense of jealousy by focusing on its enduring place in mental life (Reference Goldie2000). He compares mental life to an ecological system where someone's beliefs, desires, and emotions are knotted together into a complex whole. If mental life is like this, then the removal of one part could have negative consequences, just as a dearth of worms can cause ecological collapse.

Goldie's view is unsound. Although he ostensibly offers a holistic view of mental life, Goldie tacitly presupposes that jealousy is indispensable. But why should someone think that? Just as ecological systems can be devastated by imbalances, so too mental life can be destabilized by jealousy. The importance of any species to an ecosystem depends on the wider structure of that system. Therefore, I could agree that jealousy is occasionally valuable while still thinking people ought to feel it less frequently. More strongly, I could accept the ecological metaphor but think that jealousy is akin to an invasive species rather than a useful creature: an emotion that causes more harm than good.

Goldie is right that if people became less jealous, they would be changed. But this change does not seem to be threatening identity in the way he supposes. People often change and aspire to become better people in many ways. Just as people would not feel threatened by the possibility of being more patient or resilient or less defensive, so too they should not fear becoming less jealous. Moreover, people appear to think that personhood is threatened more by negative, rather than positive, changes, especially by negative moral changes (Tobia Reference Tobia2015; Molouki and Bartels Reference Molouki and Bartels2017). Therefore, people's view about whether becoming less jealous threatens their identity may depend on whether they think jealousy is bad. In turn, there is evidence to think that issue is shaped by bias. In Ayala Pines's study, for example, ‘agreement about the positive effects of jealousy was significantly correlated with self-perception—the more jealous one perceived oneself to be, the more likely one was to agree with the positive effects of jealousy’ (Pines Reference Pines1998: 198).

4.3 Jealousy's Intrinsic Value

Other defenders of jealousy argue that it has intrinsic value. Someone might think, for instance, that jealousy is itself a virtue, or that it is part of love. Kristjánsson takes the first route. On his analysis, jealousy is a desert-based emotion, which involves the sense that a person deprives another of a favor the other is owed (Reference Kristjánsson2002; Reference Kristjánsson2018). For Kristjánsson, the failure to feel jealousy in many cases is, ‘the sign of such a lack of self-assertiveness and self-respect, such a cringing spirit of tolerance—not to mention lack of sensitivity to injustice—that it can only be deemed a moral failure on an Aristotelian account: a vice’ (Reference Kristjánsson2018: 117–18).

The idea that jealousy responds to legitimate forms of entitlement is common but controversial. I doubt that jealousy is a desert-based emotion. The notion of entitlement at the heart of my analysis of jealousy falls short of linking the loss of affection to a broader moral notion of justice and tracks, instead, the everyday linguistic difference between desert and entitlement. According to that distinction, desert is tied to personal character and actions, whereas entitlement is a matter of social norms, practices, and institutions (Feinberg Reference Feinberg, Pojman and McLeod1970: 86). People can be entitled to things that they do not deserve, and vice versa. Jealousy need only rest on people's sense of what relationships ordinarily entail, rather than on what they personally deserve. Conversely, people should not think of compersion as a response to the deserved flourishing of others. Compersion is therefore not akin to Kristjánsson's notion of gratulation (see above).

In thinking about compersion, entitlement is a better point of focus than desert because people might think that compersion is appropriate in situations where they recognize that they are not legitimately entitled to another person's affection or in situations where they have explicitly altered the framework of their relationship with another. Non-monogamous relationships offer good examples of the latter; since partners permit each other to explore extra relationships, they relinquish aspects of their sense of entitlement.

For the sake of argument, however, let us suppose that jealousy is sensitive to desert. Several important questions remain. First, it still remains an open question, from the standpoint of virtue, whether jealousy is morally good to feel. Justin D'Arms and Daniel Jacobson (Reference D'Arms and Jacobson2000) argue that the issue of whether an emotion responds appropriately to an object is orthogonal to the issue of whether it is good to feel, all things considered. Someone may have prudential or moral reasons to feel, or avoid feeling, emotions that it would be appropriate to feel. D'Arms and Jacobson offer an example of a warrior who is courageous because he fails to feel fear in a grave situation where it would be appropriate (Reference D'Arms and Jacobson2000: 85). Similarly, people often try to resist feeling schadenfreude or contempt in situations where they would be fitting. Like these cases, jealousy could track what people deserve, that is, be fitting without being virtuous.

This possibility is especially plausible in contexts of care and love for others. Many people feel that caring relationships ought not to track the demands of desert too closely, that special relationships justify partiality, including partiality of feeling. The ‘patient, loving regard’ of love is precisely a matter of people trying to avoid feeling things that would nonetheless be fitting to feel. People hope to avoid anger and frustration at their partner's petty wrongdoing, temper their blame, try to look upon situations with kindness and patience, and so on. A full defense of this idea lies beyond the scope of this article, but if I am right, then even fitting jealousy is not best thought of as a virtue.

Even if I am wrong, and jealousy is sensitive to deservingness, is fitting, and people ought to feel what it is fitting to feel, it would still have to be considered alongside compersion as both dispositions could be virtuous. People would then face complex questions about the practice of moral habituation involved in developing these traits.

On this view, to be jealous, is to be correctly attentive to the ways that a partner denies someone what that person deserves in tandem with others; to be compersive is to be correctly attentive to the ways a partner flourishes in tandem with others. Practically speaking, however, these two dispositions are in tension. People have selective vision and are vulnerable and often aggressive, so the deck is stacked against compersion. Therefore, it would be hard to cultivate compersion while also developing a nuanced sense of jealousy. Moreover, even if it were good to cultivate jealousy, the corresponding risks of getting it wrong, of being aggressive, or jealous in contexts where jealousy is not deserved outweigh the purported risks associated with compersion, such as Kristjánsson's ‘cringing spirit of tolerance’ (Reference Kristjánsson2018: 117–18). Even if both compersion and jealousy were virtues, which I doubt, people should still favor the active cultivation of compersion over jealousy.

5. Conclusion

People's emotional lives are often awash with uncertainty and tension. Perhaps they do not know what to feel, doubt whether their feelings are reasonable, or find that their emotions clash. These tensions are often the product of the fact that people care deeply for others but remain vulnerable and concerned for themselves. These tensions are common in romantic life, and this article has explored one of them: the opposition between jealousy and compersion.

Far from the niche concern of non-monogamists, compersion is widely important. I have focused on romantic contexts for it is there that the achievement of compersion is arguably most fragile, but the emotion needs to be explored more fully. Compersion responds to the flourishing of people individuals care about in the company of people other than those individuals. Compersion is not pride or vicarious enjoyment, nor does it resemble emotional experiences like the enjoyment of horror, disgust, or masochistic pleasure, where the modification of context enables people to revel in things they evaluate negatively. Instead, compersion is a response to other people doing well. It is not the only response, however. In line with my recipe for compersion, people may reflect on their sense of entitlement and broad understanding of romantic life, and they may tame the harsher manifestations of vulnerability while not being compersive. They may struggle with dissonant jealousy or endorse their romantic situation without any noticeable positive feeling.

In some corners of the non-monogamous community compersion is an emotional goal. But in romantic contexts people must be wary of demanding compersion of others and of criticizing themselves if the emotion does not arise. The odds are stacked against compersion at the moment. In societies where monogamy is normative, jealousy is an expected, normalized, and even praised emotion (Barker Reference Barker2005; Klesse Reference Klesse2006). Against this background, dissonant jealousy is notable. Although it feels good, compersion can be fleeting and fragile, and while people might want others to experience compersion, their failure to do so does not mean they lack love, affection, or commitment.

From the perspective of value, however, these responses are better than jealousy. The various defenses of jealousy miss the mark. There is no clear and unproblematic connection between jealousy and a flourishing relationship; jealousy is not an indispensable or untamable feature of mental life; jealousy is arguably not a virtue, and if jealousy were a virtue, it would still play second fiddle to the cultivation of compersion. Compersion, in contrast, offers many of the purported benefits of jealousy without the link to aggression and in a manner that shows care for another person. To invert La Rochefoucauld's maxim: In compersion there is more love than self-love.