In 2009, when Najib Razak was appointed prime minister of Malaysia, he announced a slew of policy reforms, which included his attempt to reduce, if not end, corruption, patronage, and rent-seeking. Najib introduced the 1Malaysia slogan, his endeavour to create an inclusive nation, though he was unsuccessful in his attempt to end ethnically-based affirmative action in business, which research had long indicated as undermining domestic investment by entrepreneurial minorities.Footnote 1 In spite of these initiatives, during the 2013 general election, the ruling multiparty coalition, Barisan Nasional (Barisan, or National Front), led by Najib's party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), lost the popular vote but regained power by winning the most number of seats in Parliament.Footnote 2 Najib blamed ethnic minorities for not supporting his government and went on to introduce his own version of an ethnically-based affirmative action, the Bumiputera Economic Empowerment Policy.Footnote 3 Najib instructed the numerous state-owned enterprises (SOEs), referred to in Malaysia as government-linked companies (GLCs) to accelerate the involvement of Bumiputeras in the corporate sector, primarily through the award of government-generated rents. Najib was well aware that this policy would hamper domestic investment, potentially harming economic growth and further undermining UMNO in future elections.

Fortunately for Najib, that same year, the People's Republic of China introduced its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),Footnote 4 a policy that would have significant bearing on foreign investment flows in Malaysia. When China's president Xi Jinping visited Malaysia in October 2013, he and Najib agreed to build on their bilateral trade ties.Footnote 5 This partnership focused on China's investments in Malaysia and funding of infrastructure projects linked to the BRI. Subsequently, in 2015, another major event occurred that undermined investor confidence in Malaysia. The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal broke, further necessitating foreign investment flows, with China again emerging as a major source.Footnote 6

The state–state relations between Malaysia and China, which served to build business ties between enterprises from both countries, was primarily a consequence of this confluence of events, contributing to the need for the leaders of two dominant parties, UMNO and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), to combine forces to pursue their respective economic and political objectives. As a result, novel state–business relations (SBRs) emerged in Malaysia. While government-to-government funded projects primarily involved SOEs from both sides on a public-led basis, these novel SBRs, however, involved Malaysian SOEs and private enterprises favoured by UMNO, at either the federal or state level, working with Chinese SOEs and private enterprises favoured by the CCP, at either the national or provincial level, to implement BRI projects on a public-led, private-led, or private-public-led basis.

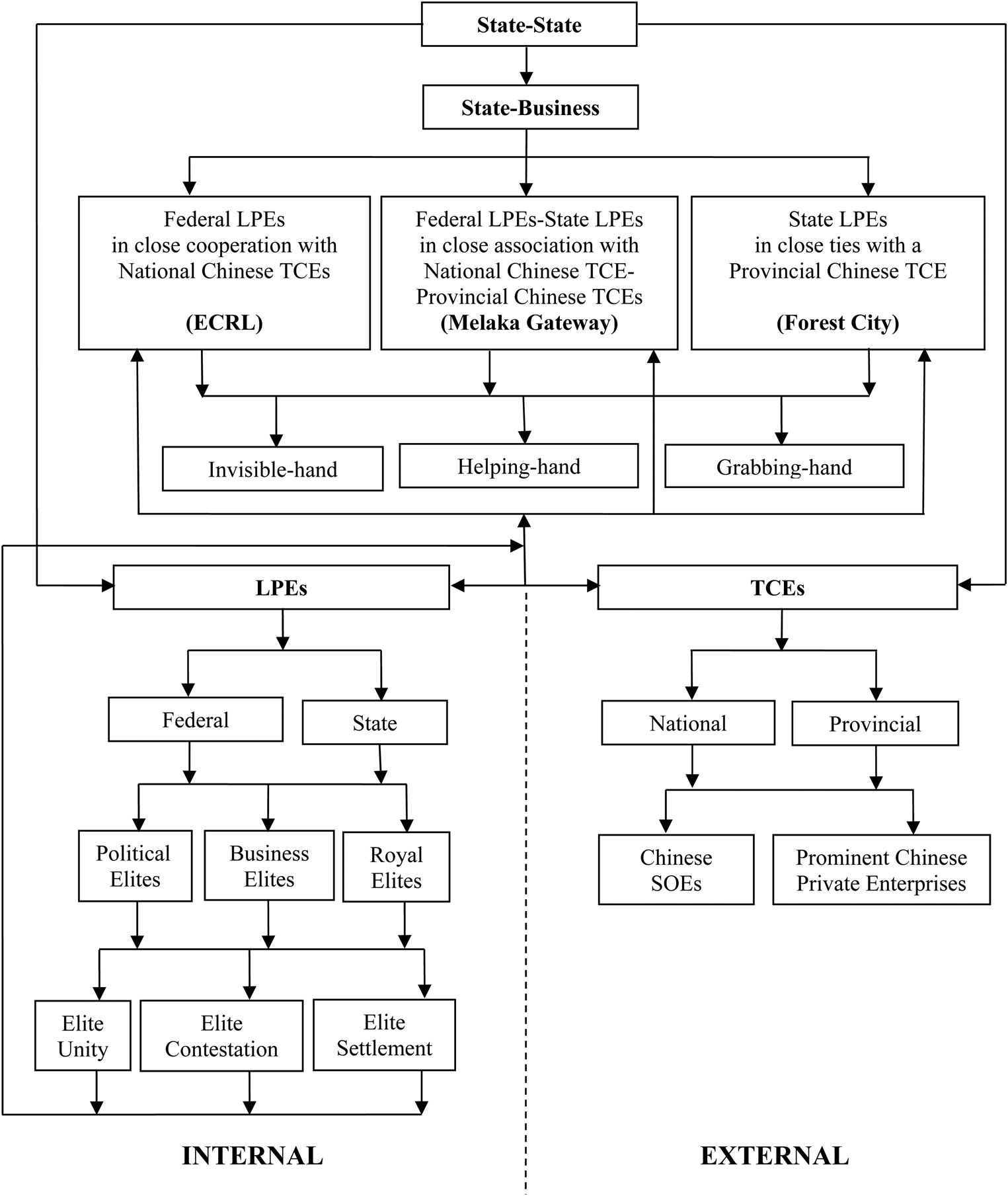

This article argues that China's BRI projects in Malaysia, based on state–state relations, shaped how local power elites (LPEs) collaborated with Chinese transnational corporate elites (TCEs). These LPEs, being key actors in the state, worked with Chinese TCEs, both SOEs and well-connected private enterprises. As a result, SBRs spawned through these BRI projects and driven by LPE-TCE links had diverse forms: federal LPEs in partnership with national Chinese TCEs; federal LPEs–state LPEs in alliance with national Chinese TCE–provincial Chinese TCEs; and state LPEs in collaboration with a provincial Chinese TCE.

Resource reallocationFootnote 7 is the most direct method employed by LPEs to shape economic development.Footnote 8 LPEs can design different SBRs, redistributing resources in a cooperative and productive manner that generates employment and fosters new industries.Footnote 9 Alternatively, LPEs can act in a predatory manner, redirecting resources away from national development objectives for their own benefit, rendering ineffective the SBRs created by them.Footnote 10

In the literature, conventional SBRs are defined as relations between domestic public and private sectors.Footnote 11 Studies based on an institutionalist approach stress the competency of bureaucrats to cultivate effective SBRs to generate economic growth.Footnote 12 In the context of this study, when two dominant parties forge state–state relations to build business ties for their respective enterprises to implement BRI projects, and this results in novel SBRs driven by different LPEs, not bureaucrats, in close collaboration with different Chinese TCEs, a key puzzle emerges: What are the outcomes and implications of these novel SBRs? Are they effective from a growth-enhancing perspective, or do they merely result in wastage of scarce resources?

There is a need to understand theoretically how state–state relations shape LPE-TCE ties that lead to different SBRs. Moreover, BRI projects in Malaysia have been implemented by different LPEs in partnership with different Chinese TCEs, frequently on a non-transparent basis, shaped by dominant parties from both countries. This study thus adds a fresh political dimension, that is, state–state relations, not dealt with in the SBR literature, indicating the need to move beyond the conventional institutionalist emphasis on bureaucratic competency for economic growth, and where state–business ties are relatively fixed and stable.

Three BRI-related projects implemented in Malaysia have been selected as case studies, the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), Melaka Gateway, and Forest City. The primary reason for selecting these mega projects, each with a multibillion ringgit contract value, was due to their potentially significant impact on the national economy, as well as the political variations that they point to about unique SBRs, at the federal or state level. These case studies offer insights into how state–state relations shape different LPE–TCE links that contribute to a variety of novel SBRs.

However, the scope of this study is limited to examining the background of key actors in the dominant Malaysian LPE groups only, not the Chinese TCEs. Furthermore, this study is limited to major economic and political events that unfolded between October 2013 and May 2018,Footnote 13 when this phenomenon of state–state relations between dominant parties emerged. This study draws data from field research and secondary sources.Footnote 14 The sections that follow comprise a theoretical review of SBRs, case studies, and lessons learnt, with a conclusion about the implications of such state–state relations on economic growth.

Emergence of unique SBRs

State–state relations for business

When Malaysia adopted a conventional form of SBR under the New Economic Policy (NEP), introduced in 1970, it was characterised by extensive state intervention in the economy, leading to what was termed as bureaucratic capitalism.Footnote 15 This SBR form subsequently evolved in diverse ways in the 1980s,Footnote 16 organised around the political and business interests of UMNO elites,Footnote 17 contributing to the phenomenon of political business.Footnote 18 However, many of these poorly-managed but politically well-connected private firms were bailed out or nationalised when the Asian currency crisis occurred in 1997, leaving the government with ownership and control of a huge number of GLCs.Footnote 19 After China introduced the BRI in 2013, the UMNO-led government appeared to focus on GLC-SOE ties, with an involvement also of politically-inclined private firms. This was done by allowing SOEs and some little-known but well-connected Malaysian private firms, usually proxies of different LPEs, to collaborate with different Chinese TCEs, to implement BRI projects. Between 2014 and 2016, when Malaysia suffered from an economic slowdown amid the 1MDB scandal, this resulted in different LPEs that had vested commercial interests in the private sector, at the federal or state level, desperately seeking out new sources of foreign direct investment (FDI), primarily from China. This indicated that there was a switch in focus by the UMNO-led government on SBR forms, one that again favoured the private sector, as another avenue to draw in FDI from China. These investments were meant to stimulate speedy economic recovery, as well as overcome the unfolding crisis.Footnote 20

China's state-driven economy was primarily organised around the CCP, which controlled different types of Chinese transnational corporations that included SOEs and well-connected private enterprises, both expected by the state to drive its large outward investment initiative.Footnote 21 In 2015, with China confronted with an economic slowdown due to excess production capacity and reduced domestic construction activities, the government accelerated its overseas funding and investment, first initiated under its ‘Going Out’ economic policy in 1999.Footnote 22 Well-endowed Chinese SOEs and politically-connected private enterprises were encouraged to play the role of TCEs by embarking on an overseas market expansion drive under the BRI agenda.

The BRI-related infrastructure development plans proposed in Malaysia served to support the intent of Chinese TCEs to secure access to foreign ventures. This confluence of policy plans in China and Malaysia—as well as the need to deal with the 1MDB crisis—led to the forging of state–state relations for business, which, in turn, led to the creation of novel SBRs in Malaysia to implement BRI projects. These SBR forms entailed close cooperation between different LPEs and Chinese TCEs, favoured by the UMNO and CCP leaderships, respectively, for the implementation of these projects.

LPE–TCE links

While political and business elites have long been seen as two dominant LPE groups with the capacity to influence public policies,Footnote 23 in Malaysia, members of royal houses are another important LPE group. Hence, there are three dominant local elites that have shaped SBRs, facilitated by state–state relations, in BRI projects in Malaysia. First, the political elites, primarily UMNO leaders with the power to promulgate policies that contribute to economic growth, along with avenues to serve their vested interests; second, the business elites, who are corporate figures with close ties to political elites, allowing them to determine how policies are shaped; and finally, the royalty, in the nine states led by sultans. Although the role of the sultans in government is ceremonial, the appointment of the chief ministers of these states is still subject to their consent, allowing them the means to influence policymaking.Footnote 24

UMNO's history is replete with intra-elite feuds, contributing to various forms of elite settlement.Footnote 25 These intra-elite disputes have partly contributed to changing SBR forms. For example, while UMNO was actively involved in business in the 1970s, following factional strife in 1987, party leaders resorted to using proxies to hold party assets. By the early 1990s, politicians had emerged as owners of major publicly-listed enterprises, due primarily to the abuse of the privatisation of SOEs.Footnote 26 Business elites were similarly divided, linked as many of them were to different political elites, a state–business tie that was imperative if they hoped to secure access to government-generated rents. With the rise and fall of political elites, the presence of politicians as major corporate figures has diminished, while numerous once-prominent business elites no longer feature as corporate captains. Similarly, members of royal houses who had emerged as owners of leading enterprises in the 1990s no longer command a noteworthy corporate presence, giving way to royalty whose commercial ventures are led by their business allies.

However, an analysis of these dominant LPE groups in Malaysia is only good at explaining issues from an internal perspective. More recent studies have focused attention on the transnationalisation of corporate elites.Footnote 27 In particular, Chinese SOEs and well-connected Chinese private enterprises (rather than individual elites), who play the key role in this process, have been defined as Chinese TCEs.Footnote 28 Although well-connected private enterprises in China may not have state entities as their shareholders, this does not imply lack of state control. Large outward investments by these enterprises still need state approval, rather than mere registration,Footnote 29 while these enterprises also appear quite subservient to the strong central state. There has been little discussion in the literature of the crafting of business ties between LPEs and Chinese TCEs to create novel SBRs from the recipient country's perspective,Footnote 30 particularly after this phenomenon of state–state relations emerged.

SBRs and types of power

SBRs can take the form of formal and regular coordination, or informal ad hoc interactions. Their scope may comprise the whole economy, or targeted sectors (in this case, mega projects), types of firms, and policy processes.Footnote 31 They generally involve highly organised relationships, but in some cases they are characterised by loose ties between the state and business. In numerous cases, formal acts by key institutions matter most, but in many cases, informal arrangements, norms, and agreements dominate.Footnote 32

According to Dirk Willem te Velde, effective or collaborative SBRs play a helpful role in developing the economy of a country, mainly by dealing with two concerns: first, there are market failures, whereby the market alone cannot achieve an optimal allocation of resources; and second, there are state failures, whereby state actors like bureaucrats may not be able to address market failures on their own.Footnote 33 In other words, effective or collaborative SBRs for economic growth are characterised by well-constructed policies, with synergistic and productive relations between the state and business.

On the other hand, ineffective or collusive SBRs in a particular country that lacks the Weberian-type bureaucracy are characterised by rent-seeking behaviour, with the capture of key institutions by influential LPEs, who include both political and business elites.Footnote 34 When SBRs are collusive,Footnote 35 mostly on an informal, ad hoc, and predatory manner, these LPEs may use state apparatuses for particular benefit. In other words, they are not used for collective goals, or to improve efficiency, or to further economic growth.Footnote 36

According to Doris Fuchs and Markus Lederer,Footnote 37 infrastructural power in SBRs is determined by the underlying economic structures, policies, and organisational procedures of the state over the business sector. They further claim that instrumental power in SBRs is determined by the influence that key business actors have over other corporate enterprises, in order to set the agenda before any interaction between the state and business takes place. Alberto Lemma and Dirk te Velde go on to argue that the outcomes of SBRs are determined by three concepts: first, the ‘invisible-hand’, where, the role of the state is limited to providing public goods, leaving allocative decisions to the private sector; second, the ‘helping-hand’, where bureaucrats actively promote private sector activity, support some firms and eliminate others, pursue specific policies, and have close ties with private firms; and third, the ‘grabbing-hand’, where members of the state are less organised as they pursue their own agenda. In the grabbing-hand mode, the government is led by politicians who are usually above the law, while political elites employ their power to extract rents.Footnote 38 In theory, the rationale for effective SBRs to develop an economy is that an invisible-hand provides sub-optimal outcomes, and a grabbing-hand leads to ineffective outcomes, but a helping-hand is an effective way in which state and business can interact.Footnote 39

Figure 1 is based on concepts adopted from the work of Nana de Graaff and Bastiaan van Apeldoorn, on Chinese TCEs,Footnote 40 as well as John Higley and Michael G. Burton, on inter- and intra-elite relationships.Footnote 41 Complementing their ideas are issues extracted from SBR-related theories, taking into account the work of Fuchs and Lederer, on different types of power,Footnote 42 and Lemma and Te Velde, on different growth-enhancing and rentier-type outcomes.Footnote 43 The concept of LPEs (political, business, and royal elites) is combined with that of TCEs (China's SOEs and prominent Chinese private enterprises), linked and shaped by state–state relations forged by two dominant parties (UMNO and CCP). In the case of Malaysia, through the shaping of different LPE–TCE links, novel SBRs were created by state–state relations, in order to implement three BRI projects (ECRL, Melaka Gateway and Forest City). The variations in these novel SBRs were partly contributed by inter- and intra-elite relationships of different LPEs (elite unity, elite contestations and elite settlements); and types of power of different LPEs (infrastructural-based or instrumental-based). Although these SBRs were an outcome of state–state relations forged by two dominant parties, they were operationalised by different LPE–TCE links at various levels. Since a variety of LPEs and TCEs fashioned these SBRs, diverse types of institutional architectures were created. These SBRs would, in turn, lead to different growth-enhancing and rentier-type outcomes (that is, the invisible-hand, helping-hand, or grabbing-hand) for each project, which could have major implications for the Malaysian economy, as well as its political system, as the case studies indicate.

Figure 1. Institutional architecture: State-state ties, SBRs, and power elites

Sources: Lemma and Te Velde, ‘State-business relations'; Fuchs and Lederer, ‘The power of business'; De Graaff and Van Apeldoorn, ‘US–China relations'; Higley and Burton, ‘The elite variable’.

Case studies

East Coast Rail Link (ECRL)

In 2007, when an SBR was first created for the East Coast Rail Link, it began as an invisible-hand during the planning stage under the Abdullah administration.Footnote 44 The project was driven by the East Coast Economic Region Development Council, to bridge the economic divide between the east and west coasts of the peninsula.Footnote 45 However, the project could not take off then, partly due to fiscal constraints.

In 2016, the Najib administration announced that the 688 km long ECRL would be revived under a state–state initiative, as this project was also in line with Xi's BRI agenda.Footnote 46 Malaysia Rail Link Sendirian Berhad (MRL), a federal GLC, then appointed China Communication Construction Co. Ltd (CCCC), a national SOE, as the contractor for the RM55 billion project on a public-led basis, with a huge soft loan from China.Footnote 47 The project was now driven by a few dominant LPEs closely linked to Najib. Inevitably, as work on the ECRL began, it evolved into one with the features of a ‘grabbing-hand’.

The politics surrounding ECRL commenced in 2015, after Najib was implicated in the 1MDB scandal. This scandal was a serious problem for UMNO, as it revealed that RM2.6 billion had been transferred to Najib, presumably from 1MDB for distribution as political funds in the 13th General Election.Footnote 48 Since UMNO feared that this exposé would undermine its chances in the next general election, due by 2018, this scandal became the root cause of a split between party leaders. The situation became worse when Najib purged his deputy, Muhyiddin Yassin, from UMNO in June 2016. Najib then actively moved to unite UMNO elites. By November 2016, the ECRL project, now to be implemented at a much-inflated cost, was seen as an attempt to secure funds from China to rescue 1MDB,Footnote 49 while an avenue was created to distribute construction works to Bumiputera subcontractors potentially linked to UMNO members.Footnote 50 The project was also expected to help stimulate economic growth, while fending off further attacks by rival elites, thus maintaining regime stability.

Figure 2 indicates the institutional architecture created when federal-level LPEs cooperated with national-level Chinese TCEs to forge a particular type of SBR for ECRL. This institutional architecture was based on a single-tier structure at the federal level only, involving a contractual relationship between a Malaysian GLC and Chinese SOEs. It was operationalised by a few dominant LPEs, specifically Najib (political, UMNO), Rahman Dahlan (political, UMNO), and Jho Low (business, Jynwel Capital). In the SBR for this project, infrastructural power was in play, primarily centred on Najib as UMNO's president and prime minister-cum-finance minister. This power had allowed Najib to instruct his ministry's holding company, Minister of Finance Incorporated (MoF Inc.), to establish MRL as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to undertake ECRL with a soft loan from the EXIM Bank of China, based on a sovereign guarantee provided by the Malaysian government.Footnote 51

Figure 2. ECRL: Federal LPEs with national Chinese TCEs as an SBR form

The huge increase in the ECRL's cost was reportedly because additional funds from this project were to be channelled to Najib to deal with the 1MDB crisis, while Najib was said to be advised by Low on matters pertaining to 1MDB's debts.Footnote 52 According to a reliable source from CCCC's Malaysia office, who spoke on condition of anonymity, Low was well-versed in international finance and Mandarin, thus playing a crucial role in this project.Footnote 53 MRL, under the coordination of the Economic Planning Unit minister, Rahman, then attached to the Prime Minister's Department, was instructed by Najib to appoint CCCC as the contractor to implement the ECRL.Footnote 54 The project subsequently bypassed parliamentary oversight, as it was undertaken by an SPV and listed as an off-budget financing project.Footnote 55 Even key UMNO leaders in Najib's cabinet were unaware of the ECRL's funding details, as later revealed by then youth and sports minister, Khairy Jamaluddin.Footnote 56

Hence, a reshaping of a conventional SBR form for a government-to-government project, one usually driven by bureaucrats, had occurred. With Najib's infrastructural power, he had hijacked a government-to-government project to create a novel SBR by incorporating an SPV outside the reach of Parliament, in order to serve his own agenda to rescue 1MDB, as well as to raise political funds, among other matters. This particular SBR would probably not have been created if the 1MDB scandal had not occurred. It appeared that Najib's infrastructural power had also emboldened Chinese SOEs to bypass bureaucratic institutions in Malaysia, whereby they just sought a one-stop endorsement from the Prime Minister's Department. In this case, state–state relations were direct, since the project was public-led. The state in these countries was led by two strongmen, Najib and Xi.

This project was primarily a predatory act that denied a helping-hand by bureaucrats wishing to assess its commercial viability. However, had the ECRL's budget been capped at the estimated RM30 to 35 billion,Footnote 57 rather than the much-inflated RM55 billion, with a soft loan from China at an attractive interest rate,Footnote 58 it potentially served to develop under-industrialised regions in the peninsula, with beneficial economic growth in the long run.

Melaka Gateway

Unlike the ECRL, a national-level project funded by the federal government, Melaka Gateway was a state-level project funded by the private sector. However, this project was under the jurisdiction of the state's chief minister, whose role included land allocation for infrastructure and property development. This project was also driven by the federal government's desire to turn Melaka into an international tourism, maritime, and high-end property hub.Footnote 59

When Melaka Gateway was first proposed in 2010, the state government was then led by chief minister Ali Rustam. In 2015, foreign investment for the project from Singapore, South Korea, Australia, and United Arab Emirates was withdrawn abruptly, amid the unfolding 1MDB scandal.Footnote 60 In 2016, the Melaka state government, now under a different chief minister, Idris Haron, promptly announced that Melaka Gateway would proceed on a state–state basis with China, given that it was in line with the CCP's BRI policy.Footnote 61 A little known but politically well-connected Melaka-based private enterprise, KAJD Sendirian Berhad, was to tie-up with Powerchina International, Shenzen Yantian Port, and Rizhao Port—Chinese SOEs at either the national or provincial level—to jointly develop the RM43 billion project on a private-led basis.Footnote 62 The project was now driven by a few dominant LPEs closely linked to UMNO, with evidence of grabbing-hand features.

The politics surrounding Melaka Gateway commenced in June 2013, when Idris Haron replaced Ali Rustam as chief minister. According to a key Melaka UMNO politician, this change of state leadership had resulted in a political feud between Ali and Idris.Footnote 63 Ali moved to wrest back the chief minister post, while Idris was serious about Melaka Gateway, as its implementation served as an important avenue for him to raise political funds and gain the support of UMNO members. In 2016, Najib allowed Idris to implement the project to help him fend off threats from Ali, as well as stimulate economic growth by drawing in foreign investment. Implementation of the project would also ensure Idris’ loyalty to Najib, helping the prime minister maintain regime stability, at a time when he was encountering serious criticism over the 1MDB scandal.

Figure 3 indicates the institutional architecture created for Melaka Gateway, involving federal- and state-level LPEs in alliance with national- and provincial-level Chinese TCEs as another type of SBR, one rather different from that fashioned for the ECRL. This institutional architecture was based on a double-tier structure that cut across both federal and state levels, with links externally to Chinese enterprises. It was operationalised by a few dominant LPEs, specifically Idris (political, UMNO) and Michelle Ong (business, KAJD) at the state level, as well as the leader of Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA),Footnote 64 Liow Tiong Lai, and Najib (political, UMNO) at the federal level.

Figure 3. Melaka Gateway: Federal LPEs-state LPEs with national Chinese TCE-provincial Chinese TCEs as an SBR form

In the SBR for this project, power was shifted away from Najib, as consented by him, and centred on Idris, who now had the infrastructural power to pursue his political intent to check Ali. This was imperative for Idris as Ali was also closely linked to Ong, when KAJD secured land reclamation rights for the 1,366 acres (553 ha) earmarked for the project in 2010.Footnote 65 Ong began cultivating links with Idris after he replaced Ali. She also had close ties with Liow, who was then transport minister.Footnote 66 In fact, Liow had good contacts with Chinese SOEs, given that his ministry was in charge of issuing new port licences throughout Malaysia.Footnote 67

Idris’ infrastructural power facilitated the appointment of the little-known KAJD, rather than established GLCs or other leading Malaysian private developers,Footnote 68 as the joint-venture partner for Powerchina. Powerchina's representatives were part of the business delegation led by Chinese premier Li Keqiang, when he visited Melaka in November 2015, to promote the joint development of this project.Footnote 69 Powerchina-KAJD later invited another two experienced provincial-level Chinese port operators, Yantian and Rizhao, to develop a strategic deep-sea port under the BRI, which was not in the original master plan, but in line with the port alliance agreement signed by both countries in 2015.Footnote 70 With Idris’ infrastructural power, he appeared willing to allow a piece of freehold land under KAJD's reclamation right to be majority-owned by the Chinese SOE.Footnote 71 Powerchina-KAJD subsequently entered into a supplementary agreement with Yantian-Rizhao to develop a RM8 billion deep-sea port,Footnote 72 primarily to be operated by Chinese SOEs, but with great potential to become a naval base.Footnote 73

A reshaping had occurred of an old SBR form for Melaka Gateway, created by Ali, a previous state-level leader. This new SBR was pushed through by Idris, with Najib's consent, to serve their vested political interests before the 14th General Election. This SBR was shaped by a political feud between two state-level UMNO leaders, with an attempt by Idris to raise political funds and wrest power from an existing party warlord, Ali. This was done with the aid of a federal leader, Najib, who also wanted to curb the power of this warlord in order to maintain regime stability. Meanwhile, it appeared that KAJD was willing to deal with such politics, given the potentially high returns from this project, more so since it was funded by Chinese SOEs. However, while this project's implementation was based on Idris’ infrastructural power, it was also greatly dependent on Powerchina's instrumental power. Moreover, in this case, the state–state relations were different from those of the ECRL since it was private-led. The states in these countries were represented by Idris, Liow, and Najib for Malaysia and some mainland Chinese business actors,Footnote 74 who appeared to be covertly controlled by the CCP.

From the outset, Melaka Gateway was primarily a project with a strong predatory dimension. There is no evidence of a helping-hand by bureaucrats to assess the project's commercial viability. However, Melaka Gateway, funded through investments from China on a private-led basis, still served as an opportunity for Malaysia to develop the state into a high-yield international tourism and property development hub in the long run.

Forest City

In 2006, Iskandar Malaysia in the southernmost peninsular state of Johor was promoted by the Abdullah administration as a special economic zone to be developed by the national sovereign wealth fund, Khazanah Nasional Berhad, with the intention of making it an alternative to neighbouring Singapore.Footnote 75 However, foreign investments for Iskandar Malaysia slowed, following the 2008 global financial crisis. In 2014, the Sultan of Johor announced that Forest City should be considered as part of Iskandar Malaysia.Footnote 76 A well-connected local private enterprise, Esplanade Danga 88 Sendirian Berhad, an SPV formed by the Sultan, along with Johor's investment arm, Kumpulan Prasarana Rakyat Johor Sendirian Berhad (KPRJ), and Daing Malek Daing Rahaman, were to tie-up with Country Garden, a leading Chinese property developer, to develop the US$100 billion project on a private-public-led basis with investment from China.Footnote 77 Unlike the ECRL and Melaka Gateway, this project was not driven by UMNO, but a few dominant LPEs reportedly closely linked to the Sultan.Footnote 78

The political considerations surrounding Forest City, to accommodate the Sultan, commenced in June 2013, when Khaled Nordin was appointed as Johor's chief minister. This appointment, in turn, had resulted in a political feud between Khaled and Daing,Footnote 79 a member of the state UMNO elite and a personal friend and business partner of the Sultan.Footnote 80 Meanwhile, after the UMNO-led government lost its two-thirds majority in Parliament during the 2013 General Election, coupled with the flare-up of the 1MDB scandal in 2015, Najib's position as prime minister was deeply shaken, with the Malay rulers speaking out openly on core issues undermining the country. To curb these unfavourable events that could destabilise his administration, Najib sought to rebuild ties with the Sultan, as well as tone down the feud between Khaled and Daing.

Figure 4 outlines the institutional architecture for Forest City, where state-level LPEs cooperated with a provincial-level Chinese TCE to create another type of SBR, one vastly different from those employed for the ECRL and Melaka Gateway. This institutional architecture was based on a single-tier structure at the state level only, with links externally to a Chinese private enterprise. It was operationalised by a few dominant LPEs, that is, the Sultan (royal, through Esplanade Danga 88), Khaled (political, UMNO-cum-KPRJ), Daing (politician-cum-businessman, UMNO-cum-Esplanade Danga 88), and Lim Kang Hoo (business, through his firm IWH Berhad),Footnote 81 reportedly another business associate of the Sultan.Footnote 82 In this SBR, power was not with Najib or Khaled, but centred on the Sultan, who had secured the 1,386 ha land reclamation right for the project in November 2013. The Sultan incorporated Esplanade Danga 88, majority-owned by him, with KPRJ and Daing as minor shareholders. He then asked Lim to approach Country Garden to jointly develop Forest City. Country Garden's founder, Yang Guoqiang, was closely linked to Lim, whose company, IWH, had sold a huge tract of land at Danga Bay to Country Garden in December 2012.Footnote 83 Lim's key partner in IWH was KPRJ. Although Country Garden was a Chinese private enterprise, this did not imply lack of state control, as large outward investments like Forest City still need state approval, rather than mere registration.Footnote 84

Figure 4. Forest City: State LPEs with a provincial Chinese TCE as an SBR form

Esplanade Danga 88 subsequently entered into a joint-venture with Country Garden to establish Country Garden Pacificview Sendirian Berhad (CGPV) to develop the project, with almost 90 per cent of its residential properties to be sold to mainland Chinese buyers only, as their prices were out of reach of locals.Footnote 85 Mahathir warned that this could eventually turn Forest City into a ‘foreigner's territory’.Footnote 86 Meanwhile, according to a source from Country Garden's Malaysia office, it appeared that Yang was favoured by CCP leaders, otherwise he would not have been allowed to invest in this massive project.Footnote 87 In early 2017, strict capital control measures were imposed by Beijing in order to curb the outflow of funds by Chinese enterprises.Footnote 88 Yet, during this period, the progress of Forest City was not undermined. Instead, Phase 1 was completed ahead of schedule.Footnote 89

A conventional SBR form for a public-led project in Johor would normally fall under the jurisdiction of the state's chief minister, and usually be driven by the state-owned KPRJ. However, the Sultan of Johor took over from UMNO elites the role as key actor in the state to implement this specific project, aided by the fact that the party was weak amid the 1MDB scandal, with its state-level leaders in a serious feud. This situation contributed to a novel SBR form, with the Sultan driving Forest City expeditiously on a private-public-led basis. Nevertheless, implementation of this project was not based solely on the Sultan's—and Country Garden's—instrumental power; it was also dependent on Khaled's infrastructural power to ensure the relevant state authorities approved the necessary applications for implementation of the project.

In Forest City, state–state relations were vastly different from that of the ECRL and Melaka Gateway, since this project was private-public-led. While Malaysia was represented by the Sultan, China was not officially represented here. Yang, however, appeared to have the backing of the CCP, as he was implementing a project, Forest City, which was in line with Xi's BRI agenda to promote people-to-people relations in the region.Footnote 90

Although Forest City has a grabbing-hand feature, it clearly has a productive dimension too, with more than 17,000 residential units sold by April 2017 under Phase 1,Footnote 91 though recent data was not available partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This BRI-related project, which also includes a huge high-tech industrial park to be developed in subsequent phases, could well serve as an opportunity for Malaysia to develop an industrial region that will rival Singapore in the long run.

Lessons learnt

Public-led, private-led, private-public-led

There are fundamental differences in the SBRs created through these three BRI projects. In the ECRL, which was public-led, state-state relations that shaped the LPE-TCE link were direct, seen in UMNO's dictate that MRL should serve as Malaysia's lead enterprise, with the CCP determining CCCC's presence in the project on a direct-negotiated basis without tender. Both states played an active role in creating a unique SBR. China played a crucial role in ensuring the project went ahead with a soft loan from EXIM Bank of China, and CCCC's requisite expertise.

Since Melaka Gateway was private-led, state–state relations were different, and indirect. The presence of UMNO in KAJD and that of the CCP in the provincial Chinese SOEs was not explicit. Although CCP leaders were not officially present in these BRI ventures, these enterprises had to seek the Party's consent before they were allowed to invest in such massive projects. Inevitably, both states were active in determining the shape of the LPE-TCE link, creating another form of SBR. The state was represented by Idris, Liow, and Najib for Malaysia and in China by some business actors, who appeared to be covertly controlled by the CCP. This contributed to the little-known but politically well-connected KAJD's tie-up with Powerchina, Yantian, and Rizhao to implement the Melaka Gateway project, with investment from China.

In the private-public-led Forest City, state–state relations were vastly different, one that was far more indirect. UMNO's presence, via KPRJ, in Esplanade Danga 88, though explicit, was not significant, whereas the CCP's presence in the provincial Chinese property developer was not clear. In this LPE-TCE link, another SBR form emerged. While the state of Malaysia was represented by the Sultan, the state of China was not represented here, though Yang appeared to be favoured by the CCP, otherwise he would not have been allowed to invest in this massive project. This contributed to Esplanade Danga 88's tie-up with Country Garden to implement Forest City, with funds from China.

Different types of power

Power in the case of the ECRL SBR was infrastructural-based and centred on Najib, as he was then UMNO's president, as well as prime minister-cum-finance minister. Since the ECRL was public-led, implementation of the project was shaped by Najib, who decided whether to go ahead with it. Only one type of power existed in the ECRL case.

In the Melaka Gateway project, power was also infrastructural, but one that was skewed towards Idris, not Najib. After Najib's position was weakened by the 1MDB scandal, Idris, as the chief minister of Melaka, a state with no sultan, secured a major say in the project, with Najib's consent. However, since Melaka Gateway was private-led, while Idris’ infrastructural power over authority approvals was crucial, implementation of the project was dependent on the instrumental power of Powerchina, who decided whether to go ahead with it, since KAJD was financially weak, with authorised paid-up capital of only RM10 million.Footnote 92 Unlike the ECRL, both types of power coexisted in the Melaka Gateway project.

In the Forest City development, the power was instrumental, one that was not with Prime Minister Najib or Chief Minister Khaled, but skewed towards the Sultan of Johor. The Sultan had hegemonic control over the state government led by Khaled, after UMNO was weakened by a serious feud among its state-level leaders, and it was his decision whether to go ahead with the project. Country Garden agreed to this form of SBR for long-term business gain. However, since Forest City was private-public-led, implementation of the project was also dependent on Khaled's infrastructural power for authority approvals. Similar to the case of the Melaka Gateway project, both types of power coexisted in Forest City.

Varied institutional architectures

In the SBR for the ECRL, a single-tier institutional architecture was employed at the federal level only, with power centred on Najib. The links to Chinese enterprises were within the full control of the prime minister. Government decision-making processes were prompt. This SBR was uncomplicated because it involved state-owned companies from both countries, at either the federal or national level, which were directly controlled by two strongmen, Najib and Xi.

In the Melaka Gateway SBR, with power centred on Idris, a double-tier institutional architecture was employed that cut across both federal and state levels, with links externally to Chinese enterprises, though still within the realm of UMNO. However, UMNO did not have full control over Melaka Gateway to dictate the agenda, as implementation of this project was dependent on Powerchina's instrumental power. Government decision-making processes were thus not as efficient, compared to the ECRL. This SBR was complex because it involved a state-level local private enterprise that was linked to UMNO and the MCA, working with national- and provincial-level Chinese SOEs that were either directly or indirectly controlled by the CCP.

In Forest City, with power centred on the Sultan, a single-tier SBR-based institutional architecture at the state level was created, with links externally to a Chinese enterprise, and beyond UMNO's control. Though the implementation of Forest City was dependent on the Sultan's—and Country Garden's—instrumental power, Khaled's infrastructural power was needed for authority approvals. Surprisingly, government decision-making processes were more efficient than the ECRL, because UMNO's role as the dominant party was passive, rendering almost irrelevant its involvement in the project. This SBR was not straightforward because it involved a state-level local private enterprise that was directly controlled by the Sultan, but also linked to UMNO, with a provincial-level Chinese private enterprise that was indirectly controlled by the CCP. This made the Johor-based SBR far more complex than those created for the ECRL and Melaka Gateway projects.

Funding

The East Coast Rail Link project secured a soft loan instead of foreign investment from China, which meant a huge outflow of repayment funds from Malaysia in future. Najib made the decision to go ahead with this form of project funding. In the Melaka Gateway project, despite secure investment from China, a huge bridging finance was needed for the land reclamation works needed to get the project started. This was dependent on the financial strength of Powerchina, given that KAJD's financial standing was weak. Inevitably, it was Powerchina who decided whether to go ahead with this form of project funding. In Forest City, though investment from China was expected, as in the case of Melaka Gateway, bridging finance was needed for the land reclamation works. This was dependent on the financial strength of both Country Garden and the Sultan of Johor, given that the latter's financial standing was quite strong.Footnote 93 Hence, both of them decided whether to go ahead with this form of project funding.

Different SBRs driven by varied LPEs determined the diverse funding sources employed. Unlike the ECRL, which was public-led, there were no major Chinese state-owned banks involved in the Melaka Gateway and Forest City projects, since they were private-led and private-public-led, respectively. This implied that the LPEs and TCEs in both cases had to find their own sources of funding from the private sector, based on the commercial viability of their projects, though Melaka Gateway and Forest City were also crucial projects closely tied to Xi's BRI agenda.

Money politics

The SBR that emerged from the ECRL was shaped by Najib's need to rescue 1MDB, as well as raise funds for distribution to UMNO members to curb internal dissent. ECRL subcontracts could be distributed to UMNO members and politically sympathetic business elites. In this SBR, Najib decided who got what, while Low, his business proxy, was subservient to him, since the project was public-led. The Melaka Gateway SBR was shaped by the political feud between Idris and Ali, one that served as an avenue to secure money to, once again, consolidate power within UMNO. Michelle Ong, their business proxy, was subservient to them, though the project was private-led. The Forest City SBR was shaped by the political feud between Khaled and Daing, as well as constitutional rights conferred on the Sultan,Footnote 94 who challenged UMNO's hegemony in his state. The Sultan decided who got what, while the state's chief minister Khaled was subservient to him, though the project was private-public-led.

SBRs, productive outcomes, and spillovers

Although the outcomes of all three SBRs had the hallmarks of a grabbing-hand, which theoretically is associated with rent-seeking that would lead to ineffective and predatory outcomes, the empirical evidence reveals that they had potentially productive outcomes. In the case of the ECRL, an invisible-hand SBR was first created in 2007. However, it evolved into a grabbing-hand in 2016, under Najib. There appeared little in the way of bureaucratic helping-hands to assess the project's feasibility. While the outcome of this project, in the short run, was deemed ineffective and predatory, the project, in the long run, was potentially effective. Indeed, serious allegations of corruption, which deeply undermined the viability of the ECRL, partly contributed to the collapse of the UMNO-led government in May 2018.

In Melaka Gateway, an SBR was first created with an invisible-hand in 2010. However, a preponderance of grabbing-hand features, involving key political elites at both state and federal levels, emerged in 2016. This shift from an invisible-hand to a grabbing-hand stifled the implementation of Melaka Gateway, as Powerchina's keen interest in the project appeared to have diminished. This was also because the project was funded by the private sector, and KAJD did not have the necessary instrumental power to undertake such a massive venture by itself.

In Forest City, an SBR was first created for Iskandar Malaysia with an invisible-hand in 2006. There was also a helping-hand involved for this project in 2014, given that the Sultan of Johor had secured Khaled's support to exercise his infrastructural power to obtain assistance from bureaucrats to get Forest City implemented expeditiously. Consequently, the outcome of this project was deemed effective, though with some predatory features. In fact, this perceived effectiveness of the project in the short run had partly contributed to the rapid progress of the project, with Phase 1 completed ahead of schedule, amid China's capital control measures in 2017, and more project funding successfully raised through Sukuk bonds in April 2020.

The SBR created for Forest City was far more profitable for the Malaysian and Chinese private enterprises involved, while the ECRL's SBR primarily served the political fundraising of UMNO elites. The Melaka Gateway's SBR's growth potential was undermined by the number of LPEs and TCEs involved at various levels, with UMNO elites in a serious feud for control of the Melaka government. The differences in the effectiveness of these SBRs, which provided productive outcomes in the short run, were due to a combination of factors. These included the nature of the project initiative (either public-led, private-led, or private-public-led), form of institutional architecture (either single-tier or double-tier), and degree of control by UMNO (either full, little, or none), which in turn determined the efficiency of decision-making processes in each case.

The spillover effects from the East Coast Rail Link are arguably the most significant for Malaysia in the long run, given that the railway will cut across four peninsular states. The ECRL will provide a crucial economic and transportation link between these states and the federal capital, as well as promote special transit-oriented development (TOD)Footnote 95 projects around major stations along the rail route. There will be similar considerable spillover effects from Forest City in the long run. Although the high-end property development is limited to an area of 1,386 ha, the project also comprises a huge high-tech industrial park, which has the potential to attract foreign investment. However, the spillover effects from Melaka Gateway will be far less significant than the ECRL and Forest City in the long run, given that the high-end tourism and property development project is confined to an area of 553 ha, and primarily aimed at the Melaka state economy.

Conclusion

Novel SBRs emanating from state–state relations between Malaysia and China, constructed by different LPE-TCE links to implement BRI projects in Malaysia, were shaped to pursue the political and economic plans of leaders of the two dominant parties, UMNO and the CCP (though the latter is arguably not simply the dominant but the sole party). A key feature of these SBRs is that they were all characterised by serious differences between LPEs, with differing forms of elite settlement. These LPE feuds and settlement needs, as well as power reconfigurations, altered planning and implementation of economic policies in Malaysia, from those that were originally of the ‘invisible-hand’ type into those that tended to the ‘grabbing-hand’. The implementation of these projects in Malaysia was also shaped variously by state-level politics, including royalty in the Johor case, as well as national business scandals, matters that potentially could undermine regime stability. Elite settlement took different forms, primarily by distributing rents to UMNO members to enhance its political support before the 2018 general election.

Power relationships differed too, as each of the Belt and Road-linked projects was either public-led, private-led, or private-public-led. Power in each SBR was either infrastructural-based, instrumental-based, or both. As a result, the institutional architecture in each SBR was different, either single-tiered or double-tiered, with varied project funding in each case—state, private, or a mix of both, through soft loans or foreign investment. The economic outcomes for each SBR also differed, with evidence of productive and predatory features. In each case, bureaucrats had little or no influence in the shaping of these SBRs. However, the actions of political elites were conditioned by their desire to adopt plans characterised by both rentier and development strategies. In these development strategies, dictated by power elites, what was crucial was the role of GLCs or SOEs. In the SBRs that were created, it was obvious that the control that state leaders had over GLCs or SOEs determined the scale and funding of the projects.

These variations in each SBR imply that the state is not a monolithic entity.Footnote 96 The dominant party in Malaysia, UMNO, had to include key LPEs in the different institutional architectures of SBRs that were created, as they had the capacity to shape political and economic outcomes. Within these institutional architectures, LPEs had varying degrees of autonomy, as well as their own interests, including the desire to attain or maintain power. Najib's infrastructural power was derived from his position as UMNO's president and prime minister-cum-finance minister, but he had to enact a system of subcontracting to party members to consolidate power during a serious UMNO factional dispute amid the 1MDB scandal. Idris’ infrastructural power was with the consent of Najib, as he was the UMNO-appointed chief minister. On the other hand, the Johor Sultan's instrumental power was derived from his ties with domestic business elites, personal wealth, as well as his influential, though officially ceremonial, position in the state. Despite the Sultan being independent of UMNO, with Khaled as a weak chief minister, a state-level GLC, KPRJ, had to be accommodated in Forest City, suggesting an element of elite settlement. Evidently, relationships between political and business elites in ECRL and Melaka Gateway, centring on infrastructural power, were vastly different from those between royal, political, and business elites in Forest City, centring on instrumental power. With two distinct sources of power in these SBRs, diverse LPEs then cooperated with different types of Chinese TCEs to implement BRI projects, based on different forms of institutional architecture, as well as varied sources of funding.

While the infrastructural power in the East Coast Rail Link and Melaka Gateway projects appeared to serve productive development outcomes, adhering to a long-institutionalised politicised business environment in Malaysia since the 1980s,Footnote 97 predatory features involving money politics in UMNO prevailed. Moreover, the slow progress of both projects suggest that infrastructural power was less effective in promoting economic growth in the short run, as LPEs were primarily motivated by the need to secure quick access to money to win elections, consolidate political support, and personally enrich themselves. On the other hand, instrumental power in Forest City appeared to be good for the project, as it was functioning outside the realm of major political institutions. UMNO's debilitating money politics was not present here. Furthermore, the rapid progress of Phase 1 of the project suggest that instrumental power was far more effective than infrastructural power in promoting economic growth in the short run. Unlike political elites, business elites have to register profits consistently in order to survive, suggesting that if both infrastructural and instrumental powers had been deployed properly in the first place, particularly with the help of bureaucrats and well-monitored by relevant oversight agencies, all three projects would likely have had effective and productive outcomes in the long run as well.

Crucially too, important variations in funding, determined also by the LPEs in each of these cases of state–state relations, were a factor that fashioned the resulting form of state-business relations. One common point emerged, namely, that all these SBRs aimed to promote economic growth in the long run, suggesting a productive nature to the ties, in spite of the evident rent-seeking involved. Furthermore, there was an expectation by CCP leaders of effective economic outcomes, since these BRI projects in Malaysia had potentially synergistic effects, provided productive relations between Chinese SOEs and the domestic business sector were forged.

As demonstrated in this study of three projects launched by Malaysia and China, SBRs can be extremely heterogeneous, with domestic political crises shaping links between foreign enterprises and government leaders. Local power elites, as key actors in the state, play an important role in shaping how projects proposed by transnational corporate elites are implemented. These complex LPE-TCE combinations can lead to a variety of SBR forms, shaped also by the nature of the projects. The wide range of government-linked companies or state-owned enterprises available to dominant parties are another crucial dimension of multifaceted SBRs, a core factor in determining if major projects can have productive or predatory outcomes, indeed even a combination of both.