A major objective of land use, forestry, and development policies in Southeast Asia over the twentieth century and beyond has been the replacement of swidden with other forms of production, ranging from wet rice paddies to commercial cash crops to forests, with governments spending hundreds of millions of dollars on anti-swidden interventions over the past half century. These have included resettlement and sedentarisation, prohibitions on specific practices (such as the use of fire), land-use zoning, subsidies and incentives, and propaganda and education campaigns, with specific tools and technologies to enable these interventions ranging from land-use maps, agricultural extension services, improved seeds, and state-built infrastructure, to name just a few. Local populations have resisted or acquiesced to these varying interventions in different ways as well, often depending on whether approaches were more coercive, like resettlement, or less interventionist, like subsidies for seeds.

Vietnam is a prime example of these issues. Two-thirds of its land area is sloping or mountainous, and for centuries, these landscapes have sustained agricultural production through swidden cultivation, mostly practised by Indigenous ethnic minority groups. Swidden (also sometimes referred to as shifting cultivation) refers to a diverse variety of agricultural practices, generally characterised by natural rain-fed conditions in areas not amenable to irrigation, in which fields are cleared through use of fire or other non-mechanised means, and on which a variety of crops are planted in cycles of use and fallow. Local practices of swidden, reflecting both myriad cultural beliefs and diverse local ecologies, have long provided a flexible means of production as economic, social and environmental circumstances shifted. Yet despite being widely disparate in practice, important for the livelihoods of millions of people, and adaptive over time, this form of agricultural cultivation has been viewed by the Vietnamese state as ‘backward’, inefficient, and a major driver of deforestation and land degradation.

Anti-swidden campaigns have been one of the most consistent development approaches applied to the uplands of Vietnam, yet have been seriously under-studied, with disparate and mostly brief discussion of these programmes in literatures ranging from agriculture and forestry to anthropology.Footnote 1 While resistance by targeted communities has been noted, as well as accommodations by local officials, there has not yet been an extended analysis of the historical range of these policies over time, how they have been organised and reorganised, and how their implementation has been shaped by competing visions of what swidden should be. This contrasts with recent work in other Southeast Asian countries, where anti-swidden policies have been examined in more depth.Footnote 2 Further, several major recent assessments of swidden practices and policies in Southeast Asia make very little reference to Vietnam, indicating that this case may not be as well-known or accessible to other Southeast Asian Studies scholars.Footnote 3

The reasoning behind long-standing campaigns against swidden throughout Southeast Asia is complex. Economic explanations, such as concerns that swiddeners required ‘more land than a peasant who cultivated the same piece of land year after year [which] made shifting cultivation extremely undesirable’, have been common.Footnote 4 The geographic areas where many swiddeners live are often in competition with other land uses, including the expansion of export agriculture; extractive industries like mining; or infrastructure works like hydroelectric dams, roads, and export zones.Footnote 5 Cultural politics also plays a role, as the peoples who swidden are often regarded as ‘others’ who are in need of state help to achieve reasonable living standards.Footnote 6 As Michael Dove has noted, ‘The swidden-based system of agriculture is regarded not merely as less good than the system of irrigated rice cultivation, but explicitly as something bad—irrational, destructive, and uncontrollable.’Footnote 7

The fact that ethnic minorities are the primary practitioners of swidden has also contributed to attempts to make these communities more ‘legible’ to development, seen in consistent discourses emphasising modernity and progress.Footnote 8 Environmental justifications, such as concerns over deforestation, biodiversity loss, land degradation, loss of ecosystem services and competition with conservation zones like protected areas and forest reserves have been particularly deployed in more recent years.Footnote 9 Such framings are omnipresent across Southeast Asia, and this article highlights how and where different justifications have been rolled out over time in Vietnam.

In this article, I outline a history of the policies and practices directed at eliminating or regulating swidden in Vietnam, examining the justifications used over time, how targets for interventions were selected and prioritised, what tools and technologies were deployed, and what the impacts and responses to these policies have been. The analysis presented here shows that the overall government goal to eliminate swidden has remained broadly constant for decades, even while successes as a direct result of policies were limited on the ground. There have been shifts over time in who should be targeted, in how reasons have been framed, and in ideas of how peoples practising swidden should be changed. I argue that these alterations are in part a response to internal debates on the efficacy of approaches, and partly due to the leeway available to local officials on the ground to shape and interpret policies. Interventions have also been altered by subversion and resistance against these policies by target populations themselves.

This interplay has resulted in a more realistic approach to swidden than is implied by dominant state discourses and has allowed officials to often turn a blind eye or paper over policy failures at the local level.Footnote 10 It may have also limited the ability of officials to use anti-swidden policy as a comprehensive state-building tool. At the same time, however, these frictional interactions have potentially also prolonged the overall anti-swidden campaigns by providing opportunities for the continual reinvention of policies, with shifting justifications and new tools over time, creating a constant cycle of intervention, resistance, alterations, re-justifications, and more interventions.

The analysis here is based on a range of sources and methods, including archival documents in the Centre des Archives d'Outre-Mer (CAOM) in Aix-en-Provence and the National Archives of Vietnam (NAV) 1 and 3 in Hanoi and NAV 4 in Dalat, as well as interviews with both upland swiddening communities and policymakers in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) and the Committee for Ethnic Minorities (CEM).Footnote 11 The documentary record is better for some regions than others, requiring an assessment of national policies to move around in space and time. While the focus does not allow for much detail regarding the diverse cultural practices and agricultural decisions that made up swidden systems on the ground, for state authorities, such details as who planted what and when did not much matter. Indeed, anti-swidden policies were usually organised so as to erase localised diversity and apply the same blunt tools in as many places as possible. For example, there was very little regional variation in the design of overall policies, despite a great variety of people and practices, from the high limestone mountains that border China to the basaltic plateau known as the Central Highlands. Yet the broadness of centralised directives often ended up creating the seeds of their own policy failures, and shifting the justifications for interventions over time allowed state authorities to paper over these failures and to find new reasons for anti-swidden policies to persist to this day.

French colonial approaches to swidden

French colonial administrators in Indochina were faced with an unfamiliar way of producing food in upland areas as swidden came under the regulatory gaze of the state. They adopted the term ‘rẫy’, a word of Tai origin, into their vocabulary as a generic term to describe what were in fact a wide range of practices.Footnote 12 For example, a 1915 document promulgating forest regulations in Tonkin noted that

Mountain populations, which have little land to cultivate, are used to ‘rays’; that is to say, to burning the forest after it has been cut down to sow rice or maize in the ashes. According to them they can grow good crops only in the new rays and they need the ashes to sow; it is for this purpose that each year they make new and destructive rays.Footnote 13

Officials also expressed dismay at those who were ‘essentially nomadic and do not hesitate to move on when their customs meet the slightest obstacle’.Footnote 14 The idea that swidden was a singular type of practice—the burning of primary forest, for which new fields were chosen every year, and which required constant ‘migration’—was a misunderstanding of the complexities of swidden, for which rotational practices were used that did not necessarily take place in primary but rather on secondary growth, and where villages were often fixed and did not ‘nomadically’ move.Footnote 15 Nonetheless, this misunderstanding and simplification of a variety of practices to one single type, seen primarily in small areas in Tonkin, would come to colour the justifications that French officials used across Indochina.

Colonial anti-swidden policies often encompassed economic, cultural, and environmental justifications, depending on location, and sometimes all three.Footnote 16 On the cultural side, the idea that highlanders were ‘indolent’ in their use of swidden, as compared with more productive and advanced wet rice cultivation that required laborious ploughing, was widespread.Footnote 17 Fitting with French ideas of a mission civilisatrice, improving these practices would promote modernity and development among those who most needed it.Footnote 18 On the economic side, swidden was considered a low productivity activity, only supplying subsistence goods.Footnote 19 The Forest Service in particular found swidden to inflict ‘incalculable damage’ on the financially valuable forests, and described swiddeners themselves as driven by ‘indifference’, ‘malevolence’ and ‘vandalism’.Footnote 20 The use of fire was considered a particularly egregious practice; it wasted timber, could rage out of control to damage land nearby, and post-ray landscapes did not regenerate back into rich forest.Footnote 21 In a theme to be repeated in later years, officials warned that if no action was taken, Indochina's forests would be lost within thirty years. Large expanses of the Indochinese landscape were presumed to have once been forest, but were now denuded and worthless: officials viewed these bare hills as the source of soil erosion, landslides, changes in local climate, and, most seriously, downstream flooding.Footnote 22

Given these projected dire outcomes, how was the state to regulate swidden? Several approaches were tried in different colonies, from legal restrictions to land-use zoning to financial incentives, all with limited reach and results. In Cochinchina's 1912 Forest Law, swidden could only be done ‘by special authorisation only in areas determined in advance by the Administrator and province chief, in agreement with the Forest Service’.Footnote 23 In Tonkin, swiddeners had to make a request to the Forest Service or the provincial authorities first, and those who cleared a ray field without permission or set fires near forests would be punished by 1 to 3 months in prison and a fine of 200–250 francs. Further, the village where such activities occurred would be held liable for the payment of the fine if the local headman ‘cannot prove that he has done everything possible to prevent the ray’.Footnote 24

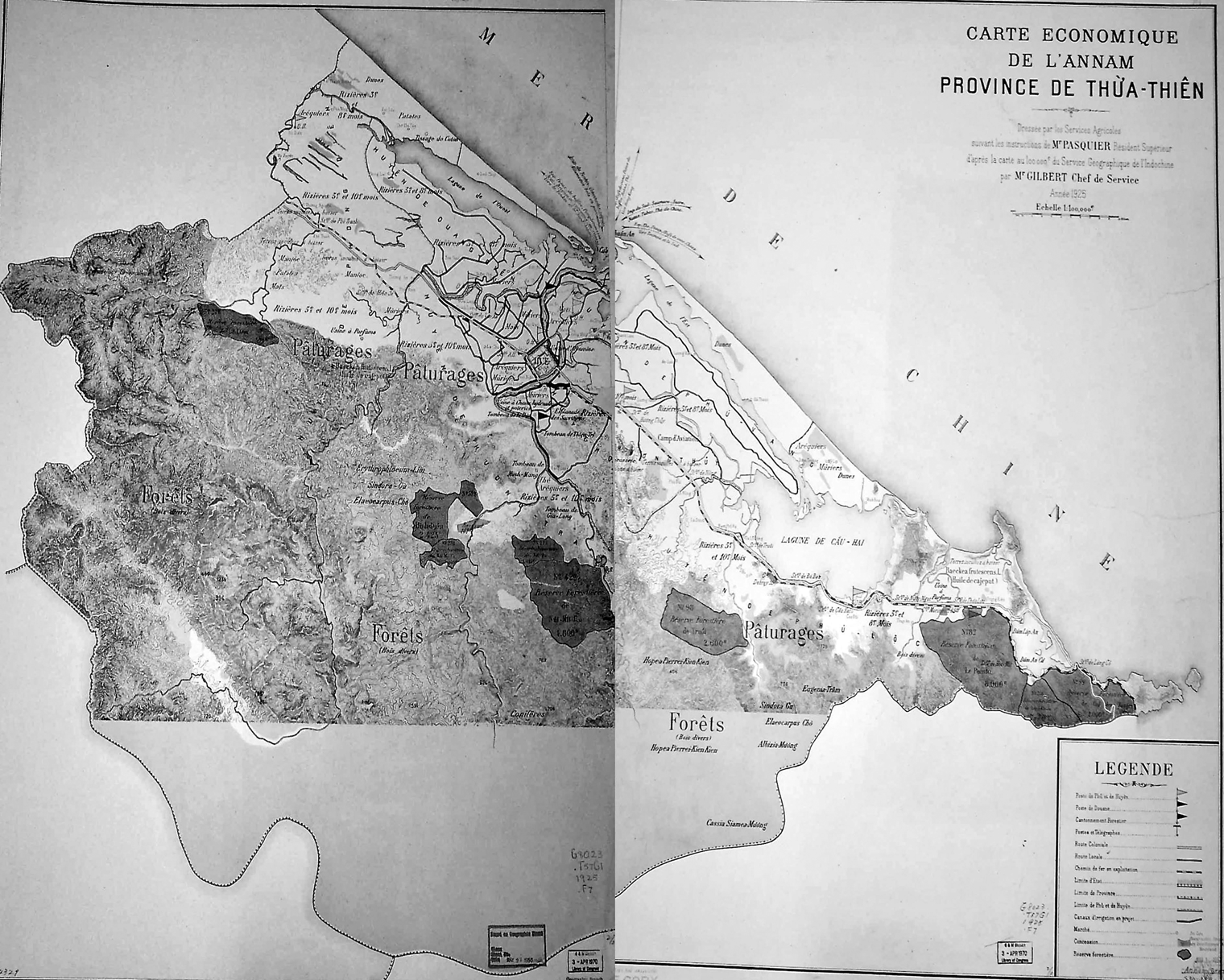

In addition to formal laws, other tools and technologies were used. Each colony's Forest Service created and mapped new forest reserves in an attempt to restrict access to the best quality timber and remove it from swiddeners’ access; the colony-wide Forest Law of 1930 reinforced that swidden was prohibited in any forests claimed by the state.Footnote 25 Detailed maps of ‘reserved’ forests were produced for each province (see fig. 1), and were remarkable for what they didn't show, often enclosing local land uses within vast stretches of ‘forêt’, with no acknowledgement of the production of agriculture in these areas.

Figure 1. Map of land use in province of Thừa Thiên, 1925.

Note: Dark areas are ‘reserved forests’, other shaded areas are general unreserved forests. Map produced by Service géographique de l'Indochine, Hanoi: Carte economique de l'Annam province de Thừa Thiên, 1926. Original map held at Geography & Map Reading Room, Library of Congress, LCCN: 93684329.

With different land uses more clearly zoned, fire control was also stressed. A manual produced for officials across Indochina advised them to ‘remove the advantage’ held by natives by deploying direct surveillance by local fire guards, restrictions on movement along paths where fires were frequent, creating fire-breaks and firewalls, and ‘rapid’ communication and publicity. Collective village punishments could be levied where fires still broke out, and in the case of catching someone in the act, there was the threat of loss of permits and user rights to forests. Other positive rewards and subsidies were encouraged for those villages free of fires, including tax reductions, granting of communal forest concessions, sponsoring village celebrations, or making gifts to pagodas. The manual also suggested propaganda posters and education campaigns, such as demonstration plots of land with a photograph taken every year to show the rich state of fire-free forests.Footnote 26

It fell primarily on the Residents of provinces and military territories to sort out competing visions of what ray was and exactly how it should be dealt with across different circumstances. Some were more avid about the task than others: the Residents of Sơn La were particular campaigners against swidden, encouraging superiors in Hanoi to take action, and asking that other nearby provinces emulate their practices. In 1918, Resident Bonnemain explained that he had sent to the six districts under his domain

a detailed circular, in which I remind them that there are obligatory forced labour punishments, according to the new code, for people who burn the forest. But I added that I do not want to rush … and that I first want to make a serious and complete inquiry into the means of replacing the ray fields with wet rice …. I have ordered all mandarins to make a careful visit of their constituencies, with a view to compiling a list of uncultivated lands which may be cultivated … [which] are more than enough to replace all the rays.Footnote 27

Bonnemain also suggested that the Tonkin government grant reductions in property taxes to those who transitioned from ray to wet rice and provide subsidies for the digging of canals and other irrigation works to further encourage this.Footnote 28

Other local Residents were less attentive or active, ranging from indifference to tolerance. In a few areas, local commissions were set up, with studies to be made of where ‘proposed areas for cultivation by ray will be allowed after clearing, with wet rice culture in lower areas and elsewhere corn, cassava, and yams’.Footnote 29 While these commissions still clearly favoured an eventual transition to wet rice cultivation, they also recognised that swidden could not be outlawed overnight as it served as the major means of subsistence food production. Indeed, the tolerance of some Residents toward swidden even led to conflicts between them and the Forest Service; for example, the Service in Lao Kay province wanted to put up posters around villages prohibiting destruction of reserved forests, but the local Resident recommended that the Service head instead undertake a ‘listening’ tour of the region, in order to ‘question the locals on the spot, receive their objections, encourage them to specify the advantages they wish to retain, and to delimit the lands they wish to occupy’.Footnote 30 The annoyed Forest Service chief wrote to the Resident Superior of Tonkin about his concern over this problematic approach, noting,

I will not mention again, because you know it, the theory of the influence of afforestation on the climatic equilibrium and, consequently, on the regulation of water. I will only say that, if we do not try to stop Evil where it is possible for us to do so, there is nothing to do but bow to the inevitability and caprices of Nature, and calmly await the floods with their disastrous effects … [T]olerance must have a limit and in any case the interests of the Annamese populations of the Delta [living downriver from the highlands] deserves consideration as well.Footnote 31

Archives from the colonial period do not allow us to fully understand the local responses to anti-swidden policies, but officials did acknowledge that ‘formal prohibition of making ray displeases’ locals, and the practice could only be rooted out if proper alternatives were presented that would change ‘their way of life, but not their livelihood’.Footnote 32 Other agricultural policies also may have inadvertently contributed to the persistence of swidden cultivation. For example, farmers of wet rice fields in Tonkin were subject to corvée labour obligations, and in one township of Sơn La province alone, 200 out of 750 households had given up rice fields and resumed upland cultivation to avoid corvée in 1906, and similar resistance might be expected to specific anti-swidden policies.Footnote 33 In the end, however, none of the anti-swidden laws nor local projects to move swiddeners toward wet rice production were successful in eradicating these practices, which persisted across the highlands to the end of French colonial rule.

Postcolonial states and swidden practices

Emergent policies in the DRV and RVN

As the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV, later North Vietnam) emerged after 1945, the first official document of the Communist Party to mention policies for swidden was put forward by the Central Committee's Fourth Plenum in 1948, which noted in a section on ‘Improving the People's Material and Moral Welfare’ the need to ‘encourage the elimination of swiddening and help in planning improvements to equipment, seedlings, and fertiliser; mobilise double-cropping of land’.Footnote 34 While this was motivated by a concern about increasing agricultural productivity, Party officials were also well aware of the need for solidarity with ethnic minority groups within the DRV-controlled resistance zones (and later the fragile postcolonial state), and the 1948 Plenum's conclusions notwithstanding, they took a primarily conciliatory approach to swidden, at least until later in the 1960s.

Open tolerance shaped these initial policies. For example, a local report from the Black River area of the DRV's Northwest in 1955 noted that officials should work directly with locals to determine the best methods for swiddens, choosing areas that were not too steep and had good soil or where advanced technology, such as fertilisers, could be applied.Footnote 35 Another publication aimed at local officials issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry in 1957 argued that swidden could be practised, but was in need of supervision and improvement: more productive modern varieties of seeds, replanting trees in old swiddens, and building fire-breaks around fields was recommended.Footnote 36 The report concluded that local officials should begin to compile information on population numbers, customs, existing rotational types, and other practices so that they could better understand (and potentially regulate) when and where swidden could take place.

A document produced by an anonymous officer in the Department of Water and Forests in the mid to late 1950s shows the conflicted feelings of administrators faced with multiple demands on forests. The report attempted to explain the phenomenon of swidden, understand colonial measures that had been taken against it, and discuss how it might be dealt with in the context of the new DRV. The author was sceptical of efforts undertaken by the French, particularly land-use zoning that had attempted to ‘reserve’ forests, and swidden regulations that did not recognise the fundamental needs of food production, considering these emblematic of the general oppression of colonialism. At the same time the author believed that swidden was evolutionarily ‘backwards’, and his solution was to treat swidden as an economic problem to be solved through the application of socialism and science.

If the majority of the mountain minorities farm swiddens … then swidden each year is A*D (area times people). If people farm swidden one year then abandon it and go to a different area, then the scope of swidden is very wide and eats up endless land … [What we can do to affect D] is the number of people who use swidden will be reduced by forestry, industrialisation, and other occupations which are developing …Then A, the area of swidden of each person, will get smaller when the productivity of each area has reached its maximum through advanced technology and most especially when economics has diversified … At that point, AD will have decreased gradually in the direction of the economies of the lowlands, and AD will come to reach zero.Footnote 37

The specific measures that the report recommended were to ‘raise consciousness’ around the benefits of keeping forests intact and the ‘harm of swidden to forests, a common asset, in [regulating the] system of climate, irrigation, etc.’. The author also recommended paying attention to the ‘many localities with different economies, cultures, societies and the level of patriotism and support for the Việt Minh in each area being different’, and thus there was a need to use ‘form and content that is appropriate with each locality, in each period, to gradually raise the consciousness of people from low to high, fixing a path for the work of leading and decreeing and eventually solving’. This would lead people to take the duty upon themselves to gradually reduce use of swidden to a minimum.

Yet while the author purportedly wanted to understand why swidden was used, and to collect ecological and cultural information so that any interventions would be appropriate for local areas, it is not clear that such information ever made it to Ministry decision-makers; the policies that eventually developed in the 1960s were not specific to regions or ethnicities. Further, the policies that were applied used a new tool of ‘sedentarisation’, or resettlement of individuals and communities, which had not been a focus before. For example, the Central Party Committee first officially broached ideas about using both sedentarisation (định cư) and ‘fixed cultivation’ (định canh) as a tool in Resolution 71/TW, dated 23 March 1963.Footnote 38 Sedentarisation was defined and used in different ways in localities, and could be as simple as building state-sponsored housing for a community where they already lived (‘settling them’), or as complex as forcing the movement of tens to hundreds of families to a location far away, where they may or may not have been provided with cleared fields and village amenities, depending on support levels. Thus, this move from a focus on altering production practices to restructuring living spaces as well marked a new turn in anti-swidden policy, and reflected the same misunderstanding that French officials had about swiddeners being nomadic that were often not based on reality or assessed using systematic means. Why state policy suddenly conflated swiddening with ‘nomadic’ movement, when research and writing in the 1950s clearly showed that swidden was an agricultural practice used by already-settled villages, is not clear, but is likely related to increasingly interventionist approaches to race, culture and society taking place across the DRV at this time.Footnote 39

Such approaches linking production and living standards also accorded with what was happening at approximately the same time in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam), where several programmes aimed at reducing swidden in the Central Highlands were developed in the First Republic period under President Ngô Đình Diệm. These included model gardens and agricultural camps, restrictions on burning to old forests only, fines for those who failed to follow guidance, and eventually, voluntary resettlement.Footnote 40 Despite the professed differences between North and South Vietnam, and between capitalism and socialism, a shared theme across both was the need for modernisation of swidden, and in the South, officials in Diệm's government believed that such improvement would help win hearts and minds for the regime.Footnote 41

In the North, swidden was also increasingly seen as an ineffective method for large-scale socialist agricultural production, and the first five-year plan (1960–65) had outlined how cooperatives and state farms for industrial crops would be used throughout the uplands and among ethnic minority peoples to ‘gradually transform their economy from an autarchic one into an all-sided economy producing many kinds of goods’, effectively eliminating swidden by development of alternatives and provisioning of incentives, as an anonymous author of the 1950s had once suggested.Footnote 42 Different industrial crops were planned out for specific areas: tea in Phú Thọ, Hà Giang, Yên Bái, and Sơn La provinces; hemp in ‘Meo areas’ (where Hmông people lived); star anise (hồi) in Lạng Sơn and cotton in Sơn La; tobacco, silk, and beans in Cao Bằng and Lạng Sơn; and bamboo shoots and stick lac (cánh kiến) in the Northwest (Tây Bắc) autonomous zone.Footnote 43 These state farms would supply produce to the state, raise money for the treasury, and serve as bases for building socialist citizens in a win-win-win. This approach of establishing cooperatives and state farms and urging voluntary resettlement to them (rather than forced sedentarisation, which would be understandably less popular) was quickly proclaimed a success. For example, in upland Yên Bái in 1963, 97 per cent of the population of 20,000 people were said to have joined a cooperative, with the area of swidden fields supposedly reduced by 75 per cent.Footnote 44 In reality, later analysis indicated that participation on state farms by ethnic minorities who had been targeted for sedentarisation was often extremely low; for example, Hoang Liên Sơn province only succeeded in settling 1 per cent of the target population on these farms.Footnote 45

By 1968, the first formal anti-swidden programme of the DRV was adopted through a Resolution of the Government Council no. 38-CP establishing the Fixed Cultivation and Sedentarisation Programme (Định Canh Định Cư, henceforth DCDC) under the Ministry of Forestry. Rather than the conciliatory tone of the previous decade, or the incentives of the state farms, the new DCDC approach was marked by prejudice and pejorative terms used to describe swidden, with purported ‘stagnant (trì trệ)’ and ‘backwards (lạc hậu)’ practices guaranteeing a ‘difficult (đau khổ)’ life, and that policies should have an ultimate goal to ‘stabilise (ổn định)’ communities, such as creating wet rice fields that would anchor populations to one place.Footnote 46 DCDC was also clearly aimed at replacing ‘scattered (rải rác)’ agricultural systems with those that were more legible and concentrated.Footnote 47 Yet such perspectives failed to see swidden as a culturally shaped and environmentally adaptive production method for sloping lands that satisfied preferences for certain foods, and which would be harder to change than simply substituting another form of agriculture or a new location.

Given financial limitations, the DCDC programme primarily deployed what was labelled as ‘mobilisation’ (vân động) to encourage targets to voluntarily relocate to new sites, particularly where households were in conflict with newly formed state farms or logging enterprises (known as State Forest Enterprises, SFEs), and such resettlement schemes had clear economic motivations as well as cultural ones. The state farms and SFEs themselves carried out the DCDC mandate by building infrastructure for resettled communities.Footnote 48 Successful resettlement relied on persuasion, family ties, appeals to patriotism, and propaganda about the dangers and unproductive nature of swidden. Despite financial constraints, 1.9 million people were targeted in the first years for such relocation, and reports and newspaper articles quickly praised the initiatives as positive political and social successes.Footnote 49

Yet interviews with villages that had been moved in the early years of DCDC confirmed that there was often little investment in the new sites, despite promises of wet rice fields and model modern houses, with tangible benefits often limited to basic tools or a small amount of cleared land. This resulted in many targeted communities simply returning back to their former areas where they could, or shifting into new lands if old fields were already incorporated into SFEs or state farms. Throughout the late 1960s to early 1970s, interviewees related mostly minimal changes in how swidden was actually practised, with some increasing incorporation of wet rice and cash crops, particularly near state farms where seeds could be obtained, and changes in tools towards more intensive cultivation (for example, moving from the use of fire and dibble sticks to animal draft power to clear and plant some fields), but little change to the overall extent of swidden fields or the many deeply-held cultural beliefs that remained grounded in such practices. Overall, the general wartime chaos in both the North and South (with displacement due to direct military conflicts, aerial bombing, or the desire to live nearer urban centres) usually had a stronger impact on choices of where to live and how and what to produce than anti-swidden policies, which were difficult to enforce in most areas outside close state control.Footnote 50

State socialism and swiddens in reunified Vietnam

After the reunification of North and South Vietnam into the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) in 1976, the primary justifications for eliminating swidden continued to be environmental factors and concerns about development. Cooperativisation, state farms and SFEs, and the DCDC programme were all expanded to the South in ways that mirrored their implementation in the North, with few adjustments for what might be different realities. Additionally, DCDC was explicitly linked to cultural and security justifications, including a need for surveillance and control of potentially unwilling new citizens, particularly given continuing threats from FULRO (Front Unifié de Lutte des Races Opprimées, the United Front for the Struggle of the Oppressed Races), an ethnic minority guerrilla force that operated in the Central Highlands during and after the war.Footnote 51 For example, in Đăk Lăk, a province in the former South, from 1970 to 1979 Adróng village in Krong Buk district moved three times to avoid armed conflicts, settling in 1979 near the new Ea Súp State Forest Enterprise, which claimed and controlled more than 300,000 ha of forest. In principle all land belonged to the SFE, and people in Adróng worked to harvest logs for the company, while (illegally) opening up their own swidden fields farther away. It wasn't until 1983 that DCDC investment was made in the village, which resulted in the clearing and presentation of 2.5 sào (1,250 m2) of agricultural land per household on the condition that longhouses were abandoned.Footnote 52 This was a common story, as the communal living of some ethnic groups in the former South was seen as politically suspect (officials worried that ties to clans would supersede ties to the new socialist state) and in addition to housing changes, policies were also adopted to abolish traditional customs associated with swidden, including buffalo sacrifices and harvest feasts—cultural practices stigmatised as ‘backward’ and ‘wasteful’.Footnote 53

The cooperative and planned economy models were not only extended to minority communities in the South, but across the region, including fitful and ultimately unsuccessful cooperatives in the rice-growing areas of the Mekong Delta.Footnote 54 The failures of socialist agriculture to rapidly transform the South were seen across both lowlands and highlands, where authorities complained of their inability to eliminate swidden or cultural beliefs associated with it. For example, by 1983, 93 per cent of families in Đăk Lăk were said to be working in cooperatives, but Party Secretary Trường Chinh complained that these were ‘in name only’, as the members ‘still rotate fields and burn the forest to make swiddens with backward tools and technology like in the past. In many places, collectivisation has occurred in only a small area to meet the duty toward the government, and the majority of the area is swidden fields.’ He estimated that swidden fields occupied three-fifths of the cultivated area of Đăk Lăk, accounting for two-fifths of total production, yet he considered this to be entirely wasteful, as ‘anyone can see that burning 1 hectare of forest will lose several hundred square metres of timber and many other forest products, all in order to get 1 ton of rice: that is crazy (điên rồ)!’Footnote 55

As Trường Chinh's concerns alluded to, the primary form of local resistance to anti-swidden policies was simply to continue the practice, albeit as far from the state's eyes as possible, which could be accomplished through making smaller fields tucked into other forests and being careful with the use of fire. Interlocutors in the former North suggested that such practices of ‘virtual’ or hidden resistance were common throughout the 1960s to 1990s, and communities in the South took up similar subterfuge after 1975. Villages continued to create and classify fields according to cultural custom and ecological conditions, planting assorted crops and allowing natural vegetation to grow back through fallow in complex ways (see fig. 2). Examples of persisting customs include practices of the Hmong of Yên Bái, where swidden fields were grouped into two types, ‘te sang’, or gently sloping lands, and ‘te tia’, the sides of high rocky mountains. For the Bahnar, their swidden fields (mir) were always placed on the side of a mountain with a low slope while dry fields (ro) and gardens (or) were cultivated intensively and not fallowed.Footnote 56 Preservation of cultural rituals around swidden could be seen as another form of resistance, as many different ethnic groups shared beliefs in a panoply of spirits associated with production, from spirits of the rice to nearby trees or mountains. For example, among the Vân Kiều, spirits (yang) that inhabited rice as well as surrounding forests required careful ceremonies, as well as a taboo on cutting or threshing hill rice mechanically, requiring that each grain in a swidden field be harvested by hand. For the Êdê, spirits related to nature needed the most propitiation for good harvests on the first day of opening swiddens, including the god of land (Lăn La), god of mountains (Chư), god of water (Ea) and god of rain (Ea Chan).Footnote 57 These rituals persisted throughout the postwar years for many groups, despite numerous attempts to outlaw or regulate them, and pejorative classifications of such beliefs as superstitions (mê tín).

Figure 2. Swidden field of a Katu household in Quảng Nam province, 2005. Sugarcane, cassava and taro are visible in the front, with bananas, palms, and other tree crops in the back, along with pepper and other lianas, as well as secondary forest growth on a fallowing hillside behind. Photograph by author.

Evaluations of DCDC's first 20 years revealed significant failures, reflecting the stagnating economic conditions typical of Vietnam nationwide in the 1980s, where all types of collective agriculture failed due to local resistance, not just those affecting swiddening minorities.Footnote 58 People often simply abandoned cooperatives they had joined, and a report from the Northwest reported drops of 50 per cent or more of Hmông workers at state farms producing tea and medicinal plants. Analysis of the 1968–86 period revealed that 41 per cent of targeted Hmông people had received some sort of DCDC intervention at the village level, only 1 per cent had moved to state farms, and 57 per cent never had any contact with DCDC.Footnote 59 The DCDC itself had been erratically funded throughout the postwar period, with promises of central funds not materialising, or jumps in funding one year to be followed by big reductions the next, leaving many projects unsustainable. Several different official reports mentioned the key figure that 30 per cent of targets were never affected or reached, indicating that it was seen as a good rule of thumb for localities to be acceptable to report, and the real figure for failures was likely much higher.Footnote 60

Đổi mới and the new economics of swidden

The opening of the Vietnamese economy in 1986 to market forces (đổi mới) instituted many changes, as cooperatives dissolved and individual households became the primary driver of agricultural production once again. These changes were reflected in the DCDC programme as well, which although it continued to operate with the overall goal of eliminating swidden, instituted some new tools and techniques, including land-use zoning and allocation, agricultural extension, and subsidies for seeds and inputs. Targets for change became much more specific: one report identified 159,000 households and named problematic ethnic groups, like the Hmông, Sila and Chu Ru.Footnote 61 Additional targets included 4,000 households living in areas prone to disasters and 20,000 households in protected forests and watersheds.Footnote 62

The administration of the programme was moved from the Ministry of Forestry to the Committee for Mountainous and Ethnic Minority Areas (CEMMA) in 1992, where it operated through district offices (Chi Cục DCDC), in turn placed under people's committees (local Party administrative bodies), under CEMMA's provincial offices, or other organisations like the Forest Ranger Service, leading to a lack of coordination and poor statistics on overall activities throughout this period. Total central government funding ranged from US$8.5–$10 million per year, with localities also contributing, totalling at least US$100 million throughout the 1990s.Footnote 63 Even though it had moved from the Ministry of Forestry, tree planting was a major component of DCDC, as it was combined with a programme known as 327 which emphasised afforestation and forest protection. The World Food Programme contributed nearly a quarter of the 327 programme budget (totalling around US$40 million a year), making it the first time that international donors had played a role in financing Vietnam's anti-swidden projects.

In line with the overall thrust of the đổi mới period, DCDC investment shifted from clearing resettlement sites and ‘mobilising’ families to relocate to investing in individual household agricultural production.Footnote 64 The collective work that swidden often required—such as labour reciprocity for clearing lands—was seen as a ‘poor motivation for creative production’, according to one local official.Footnote 65 Investments in improved agriculture varied across localities and depended on local officials’ assessments of needs, but often included infrastructure for irrigated and terraced rice fields; agricultural extension for suitable ‘highland models’ and soil erosion prevention; or the provision of credit and improved seeds, with a heavy emphasis on the role of modern science and technology. The average amount spent per household under DCDC in the 1990s was around VND4 million (US$260) per target, with some local reports noting that more than half the funding was spent on ‘administrative costs’.Footnote 66 Targeted communities had to donate in-kind contributions of labour as well, such as to build irrigation canals.

The programme largely operated on ‘project-based’ approaches (dự án), with overall guidelines suggesting the design of interventions that were ‘appropriate to local conditions’.Footnote 67 One example of a typical project was designed by a commune in Bảo Lộc district, which made an application to the province of Lâm Đồng for DCDC funding to invest in 17 predominantly ethnic Châu Mạ (or ‘Mạ’) villages with nearly 3,000 residents. The project proposal called for planting trees along the Đồng Nai river, investment in cash crops and livestock, building roads, and ‘replanning’ (‘quy hoạch lại’, a new term used instead of sedentarisation) villages out of forested areas over a six year period, and the commune requested VND18 billion (around US$1.67 million) in the proposal. Yet despite the more bottom-up design, the proposal did not have a clear sense of relationship between investment requests and changes in specific swidden practices, and read more like an attempt to get general development money from higher levels.Footnote 68

Other provinces in the 1990s also took the opportunity to redo land use planning and zoning as cooperatives dissolved and former state lands were allocated or claimed by individual households. As a result, who used what swidden fields could no longer be a community decision led by a customary leader (gìa làng) or other important elder. Rather, master land-use plans were prepared by teams from the provincial agriculture and forestry departments, describing present land use, settlements and populations, with suggested alternative land uses, and, where investment was possible, the proposed allocation of specific DCDC funds. The idea was that ‘comprehensive’ land planning would allow for new solutions to the old swidden problem.Footnote 69 For example, the land-use map in fig. 3 presents an idealised plan for a commune in Quảng Trị province in which every land-use type would be carefully delineated and plotted, with a mix of wet rice production as well as upland cash crops, which depending on location could include coffee, rubber, tea, or acacia. However, such detailed maps more often reflected wishes rather than reality, and financial constraints often limited more ambitious investments beyond these visions.

Figure 3. Land-use planning in the 1990s under DCDC for Hương Hoá district, Quảng Trị province

Note: Dark areas are zoned for forestry, while lighter areas are for agriculture, including wet rice and cash crops. Source: Summary of the Fixed Cultivation and Sedentarisation Pilot Project for Hương Hoá district, Quảng Trị province, 1991–2000 (Đồng Hởi: Quảng Trị People's Committee, 1990).

Yet major changes in swidden practices and extent occurred throughout this period as these land-use boundaries began to harden. Zoning agriculture and forestry as separate in these maps served to accelerate the conversion of swidden fields to permanent monocrop cultivation in many areas, such as coffee in the Central Highlands.Footnote 70 Other changes including moving from long-fallow to short-fallow for many communities as land-use options became more restricted.Footnote 71 By 1995, DCDC had also been integrated with the New Economic Zones (NEZ) programme in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), which moved lowland Vietnamese (known as Kinh) from overcrowded deltas to highland areas, with settlers often claiming fallowing swidden lands as they may have appeared unused to those who did not know better, and land-use conflicts were common in the 1990s and beyond.Footnote 72 Some Kinh migrants, who had been encouraged to move to the uplands by these programmes as ‘role models’ for minorities to take up wet rice agriculture, actually instead adopted swidden practices themselves, finding it a useful production model for steep slopes and relatively infertile soils.Footnote 73

Most justifications for the elimination of swidden were explicitly ecological at this period, as rapid deforestation rates, spurred by poor state forest management under socialism and the demands for timber in the đổi mới market economy, were instead blamed on shifting cultivation.Footnote 74 For example, a report from Hoang Liên Sơn province (combining present-day Lào Cai and Yên Bái provinces) noted dramatic declines in forest cover from 38 per cent to 8 per cent in one district as a result of swiddening, yet never mentioned the presence of SFEs as another potential driver of forest loss.Footnote 75 Many lands were gazetted for conservation and expansion of the protected areas system throughout the 1990s as well, often requiring the resettlement of households as agricultural fields were incorporated into nature reserves, with some families compensated, while others were not.Footnote 76 In one village in Đăk Lăk, authorities had instituted aggressive forest protection measures that denied Mnông farmers access to their swidden fields, and a village elder described these actions as ‘cruel (ác liệt)’, bemoaning that it would lead to rapid impoverishment of households.Footnote 77 Reports often noted food security declines in areas where swidden was administratively restricted.Footnote 78

Once again, some local officials were able to adaptively address conflicts through local flexibility and sympathy. In some districts, even within state-designated ‘forest land’, up to 20 per cent could be used for agricultural production, and where land allocation followed previous de facto rules influenced by community wishes, outcomes tended to avoid disputes.Footnote 79 Yet overall, by the end of the 1990s, there was little sense of progress or achievement in eliminating swidden. According to one assessment, there had been 527 total DCDC projects in the 1990s, which had resettled 36,890 households, while a different assessment noted that from 1990 to 2002, only 11,265 households were settled, giving some indication of how inaccurate statistics about this programme often were.Footnote 80 Nearly 75 per cent of respondents to a survey of DCDC investment areas reported that there had been no positive impact on their well-being, with major problems identified including poor quality of built infrastructure, poor soil quality for agriculture, and lack of consultation in programme design.Footnote 81 Yet disappointing outcomes continued to be blamed by Ministry of Agriculture officials on the fact that ‘a few localities and branches have not yet understood the problem, so they have not paid sufficient attention to results and outcomes are low’.Footnote 82

Internationalising anti-swidden policies

Poverty challenges in the new millennium

At the turn of the twenty-first century, policies toward swidden were re-labelled yet again and re-emerged as programmes for poverty reduction, as part of Vietnam's ambitious aims to meet the Millennium Development Goals. These approaches were also more internationalised, as they received substantial amounts of donor funding, extending the trend that began with the 327 programme. A national Hunger Elimination and Poverty Reduction (HEPR) strategy was approved by the prime minister in the late 1990s, and multiple ministries were charged with carrying out a series of investment programmes. While much of the funding was new, many of the programmes included were not; this included DCDC, which was merged in 2000 into a ‘Programme for Socio-Economic Development for Especially Difficult and Remote Communes’, more popularly known as Programme 135 (P135). P135 targeted more than 1,000 communes considered poor or ‘especially difficult’ and provided investment in roads, markets, health centres and schools, as well as continuing the previous eras’ focus on land allocation, agricultural extension, and sedentarisation. DCDC received US$2.2 million in funding between 2002 and 2004, making it the second smallest component of P135, dwarfed by the budget for commune infrastructure, which was 100 times larger.Footnote 83 For example, Nghệ An, a large province, only received around VND5.5 billion (around US$330,000) per year for DCDC as budgets tightened.Footnote 84

The new poverty-focus of DCDC shifted the programme toward more community development investment once again. But there was little clear sense of the relationship between swidden cultivation and poverty in programme documents, other than assumptions that people were poor because of swidden, rather than questioning whether people who were poor might be so because they were marginalised in general and had little access to land.Footnote 85 Localities receiving DCDC funds under P135 spent them on typical ‘development’ activities, including construction of roads, clearing of land for production, water and electricity systems, village cultural houses, schools and marketplaces, alongside a renewed interest in resettlement for remote populations, with officials describing their approach as one of ‘re-planning populations (quy hoạch bố trí lại dân cư)’ to move people closer to commune and village centres with incentives of money and infrastructure access.Footnote 86 This description deliberately avoided the concept of ‘resettlement’ (tái định cư) because international donors were a major source of the programme's funding, and many European funders had strict internal rules and safeguards for funding resettlement projects, although regional experiences show these rules were often violated.Footnote 87 Vietnamese officials tried to semantically avoid these problems by refusing to consider or call sedentarisation a form of resettlement, and thus safeguards such as household compensation at market levels for land lost, or compulsory informed consent and community participation in decision-making, did not apply, these officials successfully argued to donors.

P135 investments induced changes to swidden practices outside DCDC-targeted communities as well, through expanded availability of hybrid and improved varieties of seeds leading to intensification of upland plots for cash cropping, including favourable loans and priorities for state-owned or invested companies that contracted with smallholders.Footnote 88 Assistance programmes providing free or discounted high-yielding varieties (HYVs) led to steep declines in the use of local seeds; for example, in a survey across six upland communities, by 2005 households predominantly planted HYVs over local unimproved varieties, with 100 per cent of households reporting that subsidised prices were a key reason for this.Footnote 89

Declining swidden extent in many provinces could be seen in remotely sensed images by the early 2000s.Footnote 90 Across six provinces where households were surveyed in 2005 (table 1), 40 per cent of households reported a decline in their swidden area, and the primary reason given was anti-swidden policies; one province (Thanh Hoá) had re-zoned upland areas for plantations of acacia and permanent crops like cassava and sugarcane, while in neighbouring Nghệ An province, most households had lost their swidden lands to a protected forest reserve.

Table 1. Reasons for reduction in area of swidden in 2005 across six provinces

Source: Household survey by author, 2005.

As in other phases of the anti-swidden interventions, local officials served as key points of friction in implementation, which in the P135 era occurred primarily because of confusion: many branches of different ministries were involved, and there were no clear guidelines as to how areas should use the DCDC components. The lack of participation of lowest-level commune and village authorities, as well as of local people, often led to infrastructure, such as extensive irrigation channels and new marketplaces, being built poorly or in areas that were inappropriate, while households often had to contribute labour days to the projects that had already been decided at higher levels.Footnote 91 An internal report by one province revealed that of the 99 communes with DCDC investment from 1993 to 2005, the majority had met less than 50 per cent of overall targets as local officials diverted funds for other purposes, channelled kickbacks to shoddy contractors, or experienced other problems.Footnote 92 Still other localities used DCDC money as direct subsidies for poor households, providing free blankets, radios and other consumer goods, with little overall impact on production and no long-term effects.Footnote 93

Overall, despite the reconceptualisation of DCDC as a tool for poverty reduction, the programme showed little to no impact on poverty directly in assessments, and poverty rates for ethnic minorities barely budged after P135.Footnote 94 In some cases, there were reported increases in both land area used for swidden cultivation and in poverty in DCDC investment sites. This was because households who had moved closer to roads had lost income from livestock production with increased risks of animal disease.Footnote 95 Another explanation for why intensification of upland fields had not resulted in significant poverty reduction was that cash crops were sold unprocessed for relatively low value, and when combined with rising expenses for commodity inputs, meant that net incomes in many areas did not rise.Footnote 96

REDD+ and the threat of swidden to global climate

Despite the uneven success in identifying swidden as an environmental problem over previous decades, a UN-backed programme for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) emerged in the 2000s as a major new source of funding. REDD+ addresses loss of forests as a major factor in increasing carbon emissions that drive global climate change, with land use accounting for between 10–20 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. REDD+ participation requires countries to assess baseline trends and drivers of deforestation in anticipation of joining a global carbon market that would pay countries to invest in activities reducing deforestation. A focus on eliminating swidden has been included in Vietnam's REDD+ planning approaches presented in submissions to donors, with initial pilot projects focused on ethnic minority smallholder households, who have been targeted for awareness-raising activities and alternative agricultural investments to abandon swidden.Footnote 97

However, evidence remains thin that the expansion of swidden fields is a key driver of deforestation. For example, in 2013, as Vietnam began several REDD+ trial projects, out of the 27,253 cases of ‘forest violations’ that year recorded by the Forest Service, only 1,423 were cases of converting forests for swidden, while the rest were illegal loggers who had taken timber, agricultural enterprises who had illegally expanded, or developers who had damaged forests for infrastructure.Footnote 98 Further, anti-swidden programmes like P135 had accelerated the conversion of swidden fields to continuous permanent cultivation, which in turn likely also encouraged additional forest conversion for expanding demands for cash crops.Footnote 99

However, justifications for REDD+ as a pathway to eliminate swidden have continued to be prominent in many local plans. For example, at a January 2014 workshop on the progress of a REDD+ pilot in Điện Biên province, a mountainous area of Vietnam's far northwest, officials stated that the majority of provincial deforestation was due to swidden, as

[m]ost households are short of land, so they go and deforest [phá rừng, literally ‘destroy the forest’]; they don't do it all at once, they gradually nibble at forest edges that are close, a few meters each time, to expand their agricultural fields. So, if we compare with 5 years ago, we can see we have lost a large amount of forest this way. Each year we don't have close management; first is that swidden is needs to be managed, and we don't have a monitoring system to discover [violations] immediately.Footnote 100

The provincial officials even went so far as to present figures that 22,000 ha of forest had been recently lost to swidden alone, which contradicted an earlier presentation of satellite data that had estimated only 14,000 ha of land conversion from all causes.Footnote 101 Such problems highlighted the fact that accurate ‘figures on swidden are unreported, unavailable or ignored’, an issue that has persisted over the past decades.Footnote 102 Indeed, as a local official reported to a research team, ‘The existence of swidden means we did not do a good job. We cannot report on that.’Footnote 103

Discussion and conclusions

Despite variations in local conditions and practices; despite multiple changes and shifts in how policies were enacted; despite resistance from local populations; and despite consistent failures to achieve goals, anti-swidden policies have persisted in Vietnam. The justifications for why swidden should be stopped have been reinvented nearly every decade (table 2). Reasons have ranged from economic to cultural to environmental, with the balance shifting over time, and often multiple justifications simultaneously. While explicit justifications for these policies have evolved, cultural chauvinism has remained constant as an implicit driver: from a ‘mission civilisatrice’ under the French, socialist modernity under reunified Vietnam, and poverty alleviation under đổi mới, all these ideas were underpinned by a sense of the people practising swidden as insufficiently developed and culturally alien. Paternalism marked these approaches, the idea being that the state must guide and lead minorities to better choices and pathways. Another overall constant has been the search for political and cultural order in the highlands, achieved through maps of neatly plotted villages and land-use zones, roads and communication networks funded by anti-swidden programmes, and resettlement of villages out of the remotest areas. For many officials, sedentarisation meant stability meant security, no small thing for an emerging postcolonial and postwar state and socialist political system.

Table 2. Phases of anti-swidden policies in Vietnam

Sources: Le Duy Hung, ‘Some issues of fixed cultivation and sedentarisation of ethnic minority people in mountainous area of Vietnam’, The challenges of highland development in Vietnam, ed. A.T. Rambo, R. Reed, Le Trong Cuc and M. Digregorio (Honolulu: East-West Center, 1995), p. 65; MARD, Tải liệu Hội nghị tổng kết công tác định canh định cư giai đoạn 1990–2002 (Hanoi: MARD, 2004); Ministry of Forestry, ‘Báo cáo phương án đổi mới công tác định canh định cư’ (Hanoi: MOF, 1990); Lê Du Phong, Điểu tra tác động của chính sách định canh định cư xây dựng vùng kinh tế mới tới sản xuất và đời sống của đồng bào dân tộc miền núi ở một số tỉnh và những khuyến nghị (Hanoi: Đại Học Kinh tế Quốc Dân Hà Nội, 2004).

There have been other key recurring constants in anti-swidden policy over time, including the persistent misperceptions about what swidden was, and who practised it and why, what Michael Dove has identified as ‘the political economy of ignorance’.Footnote 104 Targets of policies were often subjective and arbitrary, depending on what agency was in charge at the time, and what indicators and definitions of ‘swidden’ and ‘settlement’ were in use.Footnote 105 Swidden often became a singular ‘thing’ that minorities did, with the concept taking on a life of its own, no longer referring to specific agricultural practices, but more a way of life that wasn't ethnically Kinh. Other constants in anti-swidden approaches have included opaque policy development not based on actual research or evidence, and involving little to no participation of local peoples themselves.Footnote 106 Such top-down conceptualisation was usually coupled with inadequate long-term funding and unclear instructions to localities, reflecting internal debates over the efficacy of different approaches. These resulted in overly generalised policies that failed to account for regional differences, the potential ecological adaptiveness of swidden, and its profoundly important role in cultural life.

The technologies and tools used to change swidden practices have also varied over time, including campaigns for resettlement; infrastructure and other hard investments; land-use planning; agricultural extension and technology; and propaganda and education. What tool was used when often reflected the tumultuous twentieth-century history of Vietnam: conciliatory attempts to improve but not eliminate swidden during times of war when solidarity was needed, more aggressive campaigns of resettlement and replanning in times of high socialism, and more reliance on market trends during the đổi mới period. The tools themselves were also deployed in different ways: maps were used by the French to classify large areas of state forests that ignored local claims, while they were used by post-đổi mới officials to try to create an idealised legible landscape full of specified local detail. Further, despite broad goals, most implementation was through one-off projects—a new village here, an irrigation system there—that were often not monitored over the long term. Programme evaluations were rudimentary and mostly qualitative, based on hitting targets, providing poor analysis of what interventions actually worked to reduce poverty or forest cover loss. These outcomes then raise the important question: Why have anti-swidden policies persisted for so long despite their obvious failures?

One explanation is that on-the-ground reactions altered the policies over time, contributing tweaks and changes, sometimes due to finances (more limited budgets meant more limited ambitions to change populations, or the need to seek new sources of funding, such as from international donors); due to local officials’ ability to temper and modify policies, as excessively intrusive policies might set off security concerns; and often due to frustrations of the subject populations themselves resisting unwanted interventions. The successive reshuffling of approaches, following projects that failed to meet goals, raises the question of why such ineffectual policies continued to be reproduced. The analysis here suggests that local people resisting and local officials rejigging kept anti-swidden approaches from being a more significant tool to reshape the uplands. Yet the friction encountered at local levels may have had the perverse effect of extending these anti-swidden policies and approaches. A complete and utter failure of a modernising, homogenising vision to eliminate swidden might have brought these policies to a halt, but instead, hiccups were overcome through programme alterations, different justifications, or new moving targets, all of which have kept the mechanisms going. For example, the ability to fold long-standing anti-swidden programmes into donor-funded projects, whether for poverty reduction or global climate protection, has allowed these to be repackaged for new funders and audiences, even as they often failed on the ground to increase prosperity or environmental protection.

What is the future of swidden in Vietnam? Despite decades of anti-swidden policy, it has not been eliminated. While it has been clearly declining in extent, particularly after the turn of the century, millions continue to rely on swidden practices, albeit much altered.Footnote 107 Complex cycles of rotation and fallow have been replaced by near-continuous cultivation or significantly shortened fallow in many areas, and crops grown in swiddens are less diverse, more reliant on hybrid seeds and inputs, and sold for markets.Footnote 108 Yet many other elements of swidden farming remain, including cultural practices like rain rituals, collective work parties, and preferences for local food varieties for consumption. In many fields, a lack of mechanisation and reliance on household labour, continued use of fallow cycles, or incorporation of native species still persist, particularly in areas that remain remote from roads (and surveillance), and among communities who have been able to resist top-down changes in land use. Such a conclusion that swidden is still important, although altered, aligns with other recent research in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.Footnote 109

While in other areas of the world, swiddeners have been presented as ‘true environmentalists’ for their adaptive Indigenous practices, this has not been prominent in Vietnam. None of the anti-swidden campaigns in Vietnam acknowledged the culturally-specific Indigenous relations with nature that swidden often encompasses, a situation that has likely been exacerbated by a lack of NGOs focusing on ethnic minority issues, although some voices have tried to highlight the potential environmental sustainability of swidden.Footnote 110 Nonetheless, the persistence of anti-swidden politics has also over time resulted in targets of interventions altering their own conceptions of subjectivity, with communities themselves often accepting the discourses and narratives about their social practices and lives as ‘backwards’. Such trends have clearly led to loss of Indigenous knowledge, social systems and community norms, and intergenerational learning, as interviewees often noted. Thus, the long-term consequences of anti-swidden policies may, in the end, indeed result in swidden's continuing decline, as it loses cultural meaning and importance in the lives of practitioners themselves.