Contemporary analyses of Indigenous Peoples in Malaysia (be they majority or minority indigenous) as in other countries, have shown that biases emanating from colonial officials and politically acceptable local ideologues about ‘race’ and identity have been extended and reappropriated by officials and ideologues of postcolonial governments.Footnote 1 Indigenous characteristics and identities were mostly prescribed by outsiders depending on colonial geopolitical and economic interests and often fed by the needs of local elites and patrons as well as, to some extent, by members of other Indigenous groups who came into contact with them,Footnote 2 a pattern that has continued today. Historically, externally imposed names are at best unfamiliar to Indigenous Peoples themselves who tend to link their identities to a locality (for example, valleys, rivers, mountains, island groups) and at worst they are seen as pejorative by those being labelled.Footnote 3 I refer to this method of governing that involves the creation of discourses and practices about indigeneity as ethnicising.

In the postcolonial period, the positioning of identities,Footnote 4 namely being treated as a minority either through colonisation or by internally dominant groups or both, is key to being defined as Indigenous. For the subordinate groups in this heirarchy, being Indigenous also depends, however, on the management of their situation.Footnote 5

This article deals with the ethnicising of Indigenous identities by internally dominant Indigenous groups in Malaysia generally, and in Sabah in particular; and the strategies used by affected groups to make their claims to indigeneity viable. By doing so, the article engages with scholarly interest in understanding the complexities that drive Indigenous Peoples to make identity claims based on attachment to place, and the limits of such strategising.Footnote 6 Tania Li argues that claims about attachment to place supported by the conservation movement in the 1990s set limits on those ‘natives’ who largely ‘do not fit the places of recognition’ set by the conservation agenda (such as ‘natives in nature’ or being a natural part of a park).Footnote 7 However, as pointed out by Michael Dove,Footnote 8 despite academic hesitation, Indigenous Peoples persist with the making of such claims, perhaps because of material or symbolic gains made, even if small.Footnote 9 This conservation agenda of being tied to place as an environmental subject may be difficult for many Indigenous Peoples who have a history of movement, fragmentation, displacement, the root cause of which lies in insecurity of tenure, even if as in Sabah, native customary rights are acknowledged in the Sabah Land Ordinance of 1930.Footnote 10 For smaller groups of non-land based ‘Others’, such as some ‘Bajau’ and other groups who have remained relatively mobile at sea, other bases for claims-making have to be found.

In recent years, such limits might have been overcome by those who work in the area of environmental justice. At least in discourse, environmental justice (described below), has freed indigeneity from being solely tied to place. As well, the international discourses of environmental justice, including the Convention on Biological Diversity, have paved the way for addressing social injustice through the use of common law in land disputes.

In Malaysia, the ethnicising Bumiputra policy seeks to legitimise the centralisation of social and environmental control via the classification of the population as well as of natural resources in order to control access to, use and conservation of the latter. Categorisation as a ‘native’, a ‘Malay’ or a ‘non-Malay’ affects one's entitlements and privileges as a citizen of Malaysia. Similarly, conservation policy based on the identification and categorisation of forests and coastal or marine areas as forest reserves or national parks translates into the privileging of ‘modern’ usages allowed in these parks such as research and ecotourism. This goes hand in hand with the economic privileging of ‘modern’ usages of state-managed forest and marine resource areas for timber production, oil palm plantations, and aquaculture and large-scale commercial fishery, for example. By contrast, low importance is given to the production or collection of food or timber by resident hunter-gatherers or shifting cultivators or small-scale fishers as these activities are regarded as ‘consumption’ not ‘production for the market’. Ethnicisation, through the intersection of the bureaucratisation of the Bumiputra policy and conservation discourses and practices, has produced important effects regarding rights and privileges that are increasingly attracting scholarly interest.Footnote 11

By bureaucratisation we mean the classification of the various Indigenous Peoples of Sabah as Bumiputra who are simultaneously regarded in practice as having ‘different’ characteristics (from ‘Malayness’).Footnote 12 Ethnicisation through bureaucratisation is a political process that is rendered technical;Footnote 13 this involves converting political decisions concerning hierarchies of rights, privileges and access to natural resources based on particular assumptions about ‘race’ or religion into seemingly technical decisions using expert knowledge. Measures such as the gazetting of forest reserves, and the creation of ‘no take zones’ and community use zones in national or state parks, are often regarded by conservation bureaucrats (and by some environmental nongovernmental organisations or NGOs) as technical projects, that is, to be accomplished only by those deemed to be experts, usually through consultancies. In short, the political bureaucratisation of ethnicity, which produces both the dominant and ‘Other’ ethnicities in Malaysia, reproduces itself in the arena of conservation, which determines access to and use of natural resources.

Recent expansion of global environmental justice thinking and concerns steers clear of the ‘older’ practice of ‘fortress conservation’, which gave primacy to preserving landscapes in their pristine state for their biodiversity value. By contrast, environmental justice concerns have broadened conservation to include areas ‘where we live and play’, meaning landscapes that have long been used by Indigenous Peoples for their livelihoods and for meeting the needs of their cultural life. This expansion in conservation approaches has provided room to manoeuvre for two Indigenous groups in Sabah, the Murut and the ‘Bajau’.Footnote 14 For the land-based Murut, claims made based on areas where they ‘live and play’ are providing room to manoeuvre since their lifestyle, centred around swidden agriculture, has often been considered destructive by both state conservation bodies and by technically oriented NGOs alike. The forest landscapes they have long used for producing cash crops, hunting and wage labour can now be claimed as legitimate places for ‘living and playing’. The environmental justice framework therefore provides a potential escape from social injustices resulting from the conservation approaches of the 1980s and 1990s that reduced Indigenous Peoples to ‘natives living in nature’. The newer participatory approach to conservation believes that conservation can best be achieved if culture (encompassing both livelihoods and ways of life) is respected. Such an approach implies enhanced and wider participation in decision-making of a wider array of rights (for ‘stakeholders’) than has been previously accommodated.

Foucault's terminology of productive power appears applicable to the process of social construction of Indigenous identity/ies at the local level. It is the type of power that produces ‘pleasure’ through the active agency of individuals or organisations for building new networks and alliances (or destroying them); for the joy of discovering new capacity for drawing up alternative pathways for action; for forming new discourses and practices of identity formation (or in discouraging the formation of the same); and for imagining alternative indigenous futures (or for discouraging such imagination).Footnote 15 Consequently, we will examine briefly the productive power of Murut and ‘Bajau’ groups in reappropriating the effects of the Othering initiated during colonial times and continuing in the postcolonial period by state and civil society organisations via conservation programmes.

At this point it is important to note the role of civil society. Of interest are the kinds of identities being imagined by the environmental justice movement in Malaysia generally and Sabah more specifically as it reacts to fortress conservation, which traps Murut communities in state forest reserves while taking away or curtailing their traditional livelihoods, and as it turns away from fortress conservation, to engage in participatory conservation with the Bajau in the formation and running of the Tun Mustapha (Marine) Park.

Unlike many NGOs in Peninsular Malaysia, those in Sabah have established themselves in rural areas, some through peoples’ organisations.Footnote 16 Despite such creative means of engagement at the grassroots level, the many attempts at rejecting the Federal-backed ruling parties in power in favour of indigenous political parties have been successful only once, namely during the period of Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS) from 1986 to 1994, under the leadership of Pairin Kitingan; this was a period when the ethnicising Federal Bumiputra policy was heavily criticised in the state.

Consequently, we argue that Indigenous identity claims ought to be understood not only in terms of marginalisation and loss, but also for the opportunities they present that are grabbed, watched over or complained about. In Sabah, despite the presence of an active and mature NGO movement, the pattern of NGO involvement has been to work alongside the state rather than against it, which affects agendas of change that could be acceptably implemented.

Method

The environmental justice framework finds materiality in terms such as, among others, ‘multiple use forests’, ‘community-based natural resource management’ and ‘ecosystem based management’. We will focus on ecosystems management.Footnote 17 Ecosystems management requires a shift from managing a species at one level or scale, to managing the ecological integrity of ecosystems and landscapes. When working on a problem at any one level or scale, managers must seek the connections between all levels. The political aspect of ecosystems management implies respect for local resource managers, noting power differentials among stakeholders, and ‘experts’ having a more facilitating than controlling role in decision-making processes. Our case study of Indigenous Peoples’ involvement in positioning their identities, as with Ian Baird's discussion of whether ethnic Lao people in Cambodia should be considered indigenous,Footnote 18 is located in this broader initiative of making conservation more inclusive via the ecosystems management approach adopted by proponents of the Tun Mustapha Park.

This article draws on fieldwork conducted at different times over six years by both authors, for stretches of a few months each time, as well as observations made from living in Sabah. Specifically, the authors were variously involved as team leaders or members of a team in the following research projects concerning the implementation of natural resource rights and entitlements of Indigenous Peoples. First, the National Commission for Human Rights of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) in a 2011 enquiry into the status of customary lands in Malaysia, involving consultations with 20 peoples’ organisations throughout Sabah, culminating in 30 focus group discussions;Footnote 19 second (in the early 2000s, and continuing since 2014), the preparatory and consultation process that led to the founding of the Tun Mustapha Park (TMP) in 2016, to learn in depth the active agency of Indigenous Peoples in reconciling their livelihood needs, identity claims, and the bureaucratisation of the TMP (see Figure 1).Footnote 20 Finally, continuing involvement with NGO work in indigenous rights and in conservation through teaching and consultancy, culminated in ten in-depth interviews with members of relevant NGOs in 2013.Footnote 21

Figure 1. A Murut welcoming party greets the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia researchers, Sabah, 2011 (photograph by Fadzilah Majid Cooke).

Recent expansion in thinking about environmental justice confirms that the manipulation of people is rooted in the manipulation of nature for economic gain.Footnote 22 The concern of environmental justice as praxis now is about ‘vulnerabilities and the very functioning and resilience of communities’ because there is a link between the vulnerability of the community and the state of nature.Footnote 23 This link jibes with the identity claims of Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Asia, which, in general seems viable if based on ethnicity, culture or attachment to a place, even if some analysts have found such claims to have exclusionary limitations for those who do not fit the conservation slot.Footnote 24 For many environmental justice activists, these claims for place are sites of possibility for ‘creating a strong community vision’ that is ‘reflective of the diverse needs and cultures of the neighbourhood’.Footnote 25

Bumiputraism and the bureaucratisation of indigenous identities

Malaysia is a federation of thirteen states (nine in Peninsular or West Malaysia and two on the island of Borneo, Sarawak and Sabah — the latter two whose peoples prefer their region to be seen as equal in standing to West Malaysia), and three federal territories (Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, and Labuan). When Sabah and Sarawak, with their distinctive histories and populations, gained their independence through combining with Malaya to form Malaysia in 1963, they were given special legislative powers. Notably, while responsibility for ‘aborigine’ welfare throughout West Malaysia was under the Federal government, ‘native’ welfare remained in the hands of the governments of Sabah and Sarawak.Footnote 26

It is impossible to write about the engagement of the Murut and the ‘Bajau’ in reappropriating discourses and practices about their own Othering without contextualising such reappropriation within the larger framework of the making of majority and minority ethnicities. State ethnicisation fixes the identities of the population of Sabah into neat officially defined categories (see Table 1). In everyday life, self-identification of ethnicity (switching) is much more fluid because of a great deal of inter-ethnic and, to a lesser extent, inter-religious marriages.

Table 1: Official categorisation of population in Sabah by ethnicity, 2010

Source: Adapted from Department of Statistics Malaysia, Statistical Yearbook for Sabah, table 2.5: Total population by ethnic group and religion, Sabah and the Federal Territory of Labuan 2010 (Putrajaya: Dept. of Statistics, 2016), p. 10.

There are an estimated 132 distinct languages and close to as many dialects, among the Dusunic, Murutic and Paitanic language families of Sabah.Footnote 27 Intermarriage and general ethnic tolerance in the state means that the unofficial categorisation of ethnicity (or self-identification) is much more fluid. For example, the ‘Bajau’ category could include many who would otherwise be officially categorised as ‘Other Bumiputras’ — such as Tidung, Bonggi and others. The first author has personally met Bonggi of Pulau Banggi who refer to themselves as Bajau when living away from the island; Ubian, a Samal speaking group who in the Philippines would not call themselves ‘Bajau’ in view of the pejorative connotation of the word,Footnote 28 call themselves Bajau Ubian when they cross the border into Sabah. The first author also encountered villagers in the Segama Wetlands of eastern Sabah, of Tidung (from Indonesia) who could be relegated to the ‘Other Bumiputra’ category, but who called themselves Bajau to enhance their political clout. Similarly, Sino-Kadazan groups could, depending on their cultural exposure, identify themselves as Kadazan or Sino-Kadazan. As well, the Orang Sungei of the Upper Kinabatangan River, identify themselves as Tambonuo if Christian, or as Orang Sungei if Muslim, the latter most often residing in the Lower Kinabatangan and coastal areas of eastern Sabah. Some Orang Sungei who have Bajau ancestry could also call themselves Bajau (see interview below). Through migration, Tambonuo can now be found in the Tun Mustapha Park area at Pitas and in the Bengkoka Peninsula in northern Sabah.Footnote 29

Intermarriages were accepted, and even welcomed, historically in Sabah, including with ethnic Chinese, since it is not difficult to imagine that for the west coast Kadazan, Christianity and the early Chinese pioneers in Sabah who proved themselves to be viable agriculturists, traders and craftsmen were looked upon as the purveyors of modernisation.Footnote 30 Many Sabahan leaders, including the former chief minister, Pairin Kitingan, are married to ethnic Chinese. The first chief minister of Sabah, Donald (Fuad) Stevens, had Australian, Chinese and Dusun ancestry. As a result, there emerged in Sabah a category of individuals who are popularly known as Sino-Kadazan who have been accepted as ‘natives’ and are legally able to buy land.Footnote 31 In the east coast of Sabah, intermarriage was also common among early Chinese migrants and the local Orang Sungei as well as with ‘Bajau’ and Suluk. So questions about ethnic identity do not always solicit straightforward answers.

My father is Bajau, my mother Orang Sungei, my grandmother Chinese, and now I am living in an Orang Sungei village. So am I Bajau?Footnote 32

My parents were Sulug from southern Philippines, they came with the logging boom and worked in the timber camps. But I was born here (in the Lower Kinabatangan) and have never been to the Philippines. I married an Orang Sungei. The Orang Sungei want me to continue working with them in promoting ecotourism because I have been exposed to NGO and government networks through training.Footnote 33

In everyday life, most Indigenous Peoples in Sabah encounter the effects of the ‘Federal factor’ — namely, the effects of bureaucratisation of Bumiputraism through ethnic categorisation and intensified Islamisation (described below) which have implications for citizenship rights and privileges. The ‘Bajau’ and the Murut though have an additional effect to contend with, namely, the phenomenon of Kadazandusun dominance in education and the public service.

The state-level employment of Kadazandusun groups (less so Murut) is a prime site for exposure to bureaucratised ‘Malayness’. Such exposure provides a basis for defining who Kadazandusun are not (not Malay, not Muslim, and not the same as those from ‘Malaya’). After all, the underlying basis of Kadazandusun nationalism from the initial period of its development in the post-Second World War period (then known as Kadazan nationalism) to the present is a shared resentment of the dominance of what they term ‘Malaya’ (Peninsular Malaysia) dominance.Footnote 34

Many Kadazandusun groups have the early advantage of formal education even before the formation of Malaysia, with Catholic, and later Protestant churches playing a major role. By 1953 there were 40 Catholic schools and 6,000 students, a majority of whom were Indigenous, largely in western Sabah.Footnote 35 Consequently, by the 1950s and ‘60s, a small elite of educated Catholic Kadazandusun, in Sabah's west coast, some with links to colonial bureaucracies, confident in speaking and writing in their own language as well as in English, began to view Kadazan as a distinctive language, although the British administrators continued to regard the many languages as Dusun during the 1950s and beyond.Footnote 36 In an effort to be inclusive, the name Kadazandusun was coined but not at first accepted by Dusun groups who did not identify themselves as Kadazan. After the formation of Malaysia, education expanded geographically to the rest of Sabah, through the intensified government project of mass education for Bumiputras. Increased Federal government funding in education in Sabah produced results. Between 1971 and 1978 the number of students enrolled in secondary schools increased twofold, reaching 100,000 by the 1980s. Moreover, the number of Indigenous graduates increased from two to 2,338 in 1980.Footnote 37 So, in the field of education, being Bumiputra, even if non-Muslim, confers clear advantage, as there is additional support for such students from the state-linked Sabah Foundation (Yayasan Sabah).

Religion is a defining factor that differentiates middle-class Muslim Sabahans as well as non-Muslims from Muslim Malay Bumiputras of Peninsular Malaysia. A Sabahan Muslim writer defined Islam in Sabah as ‘more relaxed’ than the version in ‘Malaya’.Footnote 38 A Muslim middle-level civil servant in Sabah felt that despite going to a Catholic school as a child, he never felt in need of protection from other religions unlike the Muslims of Semenanjung (Peninsular Malaysia) who are often described by their political leaders as vulnerable and under threat from ‘other’ religions.Footnote 39 He felt that the bureaucratisation of Islam in Malaysia is making it difficult for Muslims in Sabah in their relationships with Christian Bumiputras, many among whom are related to them via marriage.

That the middle class could be a strong site for the deep impulse of ‘Sabah for Sabahans’ can be seen in the places where they work, especially in the recruitment and promotional practices of the bureaucracy and tertiary institutions and should be further investigated. One example of the ‘Sabah for Sabahans’ sentiment surfaced in the choice for a new vice chancellor for Universiti Malaysia Sabah to replace the incumbent whose term of service was ending in 2017. Since universities are federally funded, the campaign for the appointment of a Sabahan academic was meant for Federal government ears. The campaign for a Sabahan academic among the middle-class public went on for months, culminating in the involvement of the Sabah chief minister and a few other senior ministers, who showed their preference by pointing out that ‘there are many Sabahans who could do the job’.Footnote 40

The context for Bumiputraism needs to be presented here so that the contrast between the historical experience of Sabahans and groups in West Malaysia in terms of identity formation and religious and ethnic tolerance or intolerance can be better understood. The making of majority ethnicity via Bumiputraism has been written about by many, among them A.B. Shamsul, C.W. Watson, and Anthony Milner.Footnote 41 The process has its roots in the political construction of Malayness by Malay ideologues in the late colonial era and was endorsed by the leaving British in 1957, who had earlier decided that the ‘Malays’ were their chosen natives to be groomed and entrusted with continuing the task of governing when they departed. The ‘Malays’ were in effect comprised of many ethnic groups from the surrounding seas and lands, including Minangkabau, Bugis, Buweyan, Javanese, Rawa, Mandailing, and whose claims to being pure Malay were often contested.Footnote 42 There were also a range of views about what the new Malayan nation ought to be like. However, a conservative group of ideologues at the time won the argument for Malay privileges and special rights based on bangsa (‘race’) over other positions that aspired towards universal rights as in the idea of kebangsaan (nationhood), where it would be possible for non-Malays to be part of kebangsaan Melayu, even if they are not of bangsa Melayu (Malay ‘race’).

In the period after 1970, subsequent to what some would say to be ‘racially’ induced rioting in 1969, Malay dominance grew to become Malay hegemony with the institutionalisation of Malay economic privilege through the formation of government-linked development agencies, an administrative bureaucracy that is Malay-dominated, and an educational and cultural policy that promotes Malay language and Malay culture as ‘national’ culture.

Since the 1980s, bureaucratised Malayness has been felt to be under threat because of the increasing Islamisation especially within the middle class which could provide Malays with a larger, more unifying identity of the Umma (not only of bangsa). Feeling pressured to show its Islamic credentials to match the challenges posed by the opposition Islamic party Parti Islam seMalaysia (PAS), retaliatory policies of the government led to the increasing Islamisation of the bureaucracy and Islamic procedures being adopted in mass media, public life, and in increasing the machinery of the thought police for monitoring aspects of private life, culminating in the observation by some non-Muslim non-Malays that the state itself is reinforcing the Islamic resurgence, although the initial impetus could have originated from the middle classes.Footnote 43 Islamisation has provided official Malayness competition in terms of Malay identity formation, in the emphasis among Islamist ideologues that Malays are or should be members of the larger Umma, a pulse which is captured and reappropriated by bureaucratised institutional Islam.Footnote 44

Within this context, Indigenous identities in Sabah do not fit the Malay prescriptions of Bumiputra, so that the circle is felt by bureaucratic Islam to be incomplete. Intensified Islamisation was thought of by Federal and some Sabahan leaders as a way to try to make the non-Muslim natives ‘real Bumiputra’ or the Muslim natives ‘better’ Bumiputras, thus completing the circle so to speak, as is being done with the Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia.Footnote 45 While looking for a place to have lunch, an academic colleague from West Malaysia passing a Chinese restaurant full of Sabahan Muslim men and women, the women wearing headscarfs (tudung), commented: ‘They (the Muslims in Sabah) frequent coffee shops operated by Chinese and eat from the same plates formerly used by non-Muslims at restaurants at weddings, because their Islam is “different”.’Footnote 46

Much to official consternation, the spokespersons of Kadazandusun groups at various times have upheld the idea of their being the ‘definitive’ people of Sabah, thereby reappropriating the term used by the Mahathir Mohamad who years ago claimed that the Malays were the ‘definitive’ people of West Malaysia.Footnote 47 The pribumi category introduced in the 1980s was strongly opposed by leaders of non-Malay natives because of the potential of making all natives the same, with the possibility of non-Malay natives losing out on being the ‘definitive people’. It is clear that the discourse of being ‘native’ produced the power and pleasure of claiming exclusiveness. For the Murut and ‘Bajau’ peoples, the effects of bureaucratisation are more varied, arising from a less secure positioning with regard to identity and place in Sabah's social order.

The Murut, conservation and identity

The Murut, unlike the Kadazandusun, continued to be isolated from mainstream education, initially because of the tyranny of location, namely, living in the interior valleys that remained inaccessible partly because of early Murut resistance to colonial and outsider encroachment into their epistemological space and lifestyle.Footnote 48 Owen Rutter in the late nineteenth century made the observation that the Murut were ‘not as evolved’ as the Dusun in the hierarchy of sociocultural development, while the Murut themselves were not inclined to think of themselves as one Murut nation, and especially not of Dusunic origins.Footnote 49 Similarly, Thomas Rhys Williams, in a functionalist way, labelled the persistence of Murut resistance from the 1880s to 1915 culminating in the Rundum Rebellion, to an unstable element in Murut culture or an internal cultural disequilibrium that led to ‘nativistic’ movements.Footnote 50

Today, the Murut, who are largely Protestants, cannot make religion an instrument for aspiring to better treatment by the Malay-dominated bureaucracies (Federal) that manage Bumiputraism or by state-level bureaucracies that manage their forest or coastal environments. Because of the bureaucratisation of conservation, Murut territory in the interior of southwest Sabah was carved up by state conservation via the formation of forest reserves to be managed by the Sabah Forestry Department. Another section of the forests in southwest Sabah where the Murut have established customary rights has been converted to commercial pulp and paper plantations.Footnote 51 Bureaucratised conservation views natives living in forest reserves, their lifestyles and livelihoods based on shifting cultivation, as destructive — to be curtailed at best or prevented at worst — and often they are asked to resettle themselves elsewhere outside the forest reserves. In the logic of modern forest administration, reserves are meant for an hierarchy of use, priority being given to timber production followed by ‘modern activities’ such as scientific research and tourism.Footnote 52 The link between the survival of Indigenous lifestyles and the viability of cultural tourism is understood in some state conservation departments, but such an understanding has to struggle against the more established views of fortress conservation.

Experience with the Murut Tagol shows that more peaceful means than the ones adopted by their ancestors are being advanced to maintain their way of life, this time through conservation (see Figure 2).Footnote 53 They feel that they are trapped by the declared state forest reserves, the centralised control of fortress conservation, and ‘modern’ development priorities, in this instance for timber production. With the help of some NGOs, several strategies were developed, all within a framework of actions considered acceptable by the status quo. In Malaysia, civil society organisations have found it more efficient, in order to introduce alternative pathways and futures, to work alongside the state in view of its surveillance of non-state sectors.Footnote 54 This section and the next examine the extent to which environmental justice-informed conservation is providing opportunities for Indigenous Peoples to voice their claims and maintain their livelihoods.

Figure 2. Murut women whose villages are located in forest reserves, Sabah 2011 (photograph by Fadzilah Majid Cooke).

Upon the creation of forest reserves, in this instance Kuala Tomani, some villages were asked to vacate their areas, while others were allowed to stay, on condition they did not expand their shifting cultivation. Vigilant monitoring by the Sabah Forestry Department including warnings about arrest and jail terms resulted in the Murut in the area responding in one of three ways: moving out of the Kuala Tomani Forest Reserve or relocating to another Murut village; or staying put, but not daring to cultivate beyond the areas of their existing farms; or continuing to cultivate and opening new lands as of old. Among many who continue with their farming of dry rice interspersed with root crops together with cash crops of coffee and now rubber, there is a sense that they are not going against any state law.

Assisted by NGOs concerned with Indigenous rights, the villagers sent endless letters and appeals to Sabah state bureaucracies, to their political representatives, and to SUHAKAM, to defend a forest-based lifestyle entwined with their livelihood. Murut identity claims are based on getting state recognition for their status as ‘natives’ who are entitled to lands under individual Native Title or under Communal Title, and whose rights must be respected, even if they are in state forest reserves. Murut villagers patiently pointed out that they were living in the area before the formation of the Kuala Tomani Forest Reserve in 1986. The Murut appeals were likened by one villager as being treated ‘like a football’,Footnote 55 shunted from department to department, occasionally getting the attention of the political leadership, and once, the attention of the chief minister. Another villager who leads the group for claiming titles to their lands stated that:

We have been living here more than 50 years, some have moved from elsewhere when the forest reserve was formed in 1986 but we were here first. They did not see us when they formed the reserve. Villagers were frightened. How will we live? I went to see the NGOS, I went to seminars and met with YBs (our political representatives}. I learnt about what we can and cannot do. I made the conclusion to continue our way of life. We grow hill rice. We converted our cash crop from coffee to rubber because we can keep the rubber because Forestry Department thinks it is a non-timber forest product — not like oil palm — it is not a forest product, and we can sell it any time we need cash. … We are applying for village land so for the purpose of growing fruit trees and firewood. Both are allowable under the legislations. … I decided to continue farming. And not be frightened … many others followed.Footnote 56

The productive power of villages ‘trapped’ in the Kuala Tomani forest reserve is captured by the above interview. Alliances were made with NGOs, who organised paralegal training regarding Native Customary Rights, and provided assistance on how to make claims based on customary rights and place as described in the law. One crucial instrument was community mapping, where mental maps are translated onto paper using Global Positioning Systems technology, a language understood by the courts. Criteria used in community mapping which do not appear in most maps of state forest reserves include burial grounds, and evidence of occupation prior to the formation of the forest reserve — fruit trees, village houses or longhouses (if in Sarawak) and much more.Footnote 57 Villagers have learnt that while rubber trees are acceptable to the Sabah Forestry Department, oil palm is not considered a forest species. In 2013, after more than twenty years of wooing and pleading, no title had been issued from the ‘fortress’.

Other groups of Murut in the same Kuala Tomani Forest Reserve at Imahit village were less patient. They took their case against the Sabah Forestry Department to court using common law as has been done by many Indigenous groups before them. They lost their case at the Magistrate's Court, which meant that their rights were not recognised by the court as existing within the Forest Reserve, but won at the High Court, which ruled that rights can only be extinguished through a proper process and that no such process had been undertaken; however, the Murut finally lost again at the Appeals Court in 2013.Footnote 58

Nevertheless, ‘natives’ around the world (e.g., the Awas Tingni in Nicaragua, the Nisga'a in Canada, and the San in Botswana), as well as in Malaysia including Sabah, are taking action in the courts and many have won. As a result, many precedents have been created in various countries that customary rights ought to be respected as long as they have been established via legally acceptable means unique to each country. Such wins disrupt the entrenched view that native identities can be rebuilt elsewhere, in other territories and forests or when they are faced with deforestation and displacement for ‘development’.Footnote 59 This assumption can be seen in the contradiction in development policies which regard Indigenous lifestyles as an embarrassment to a modernising country, while simultaneously seeking to commodify Indigenous cultures for tourism purposes; both assume that Indigenous cultures are open to regeneration, without the natural resources upon which those cultures are based. Such an assumption explains why many national governments are resistant to international conventions that have the potential of changing or questioning this view, one of which is the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

Article 8 (j) of the CBD, is a bare-bones ‘framework’ Convention which holds general obligations that can be summarised thus: expanding conservation to include Indigenous Peoples’ participation through the principle of free and prior informed consent (FPIC) of the communities themselves; the protection of traditional knowledge, lifestyles and culture relevant to the conservation of biological diversity, as well as equitable sharing of benefits from conservation activities.Footnote 60 Lifestyles to be supported according to the Article are those embodying ‘traditional lifestyles’ as embodied in ‘traditional knowledge, innovations and practices …. That are relevant to conservation’. In this sense, while the Convention captures the conservation approach embraced by social movement organisations of the 1980s and 1990s earlier described which would not fit all Indigenous communities, it differs in terms of its participatory emphasis. In this instance, community participation is to be promoted through implementing FPIC.

Many NGOs are now working on implementing the FPIC concept in practice,Footnote 61 and it is a slow and difficult process, since getting formal consent has not been a familiar approach in a sociopolitical system that has tended to be top-down or in techno-speak, ‘administration by consensus’. In Malaysia generally and East Malaysia specifically, the record for promoting participatory approaches and protecting biological and cultural diversity has not been stellar.Footnote 62 Within the environmental justice framework, social injustice has occurred with the Murut losing out to short-term benefits (revenue generation from timber) against long-term rights to livelihood and territory (and by extension, identity). The solution, according to this framework, is to deal with social vulnerabilities and create capacities for social resilience. That the Murut have gained capital via NGOs in the environmental and indigenous rights movement is a clear example of praxis. For the Murut at Imahit, the win at the High Court (even if they lost at the higher Appeals Court) meant that the decision could join the list of precedents that have been created via common law, the first being the Mabo case in Australia, then the Sagong Tasi (Orang Asli) case in Peninsular Malaysia, among others.Footnote 63

The ‘Bajau’ and participatory conservation in Tun Mustapha Park

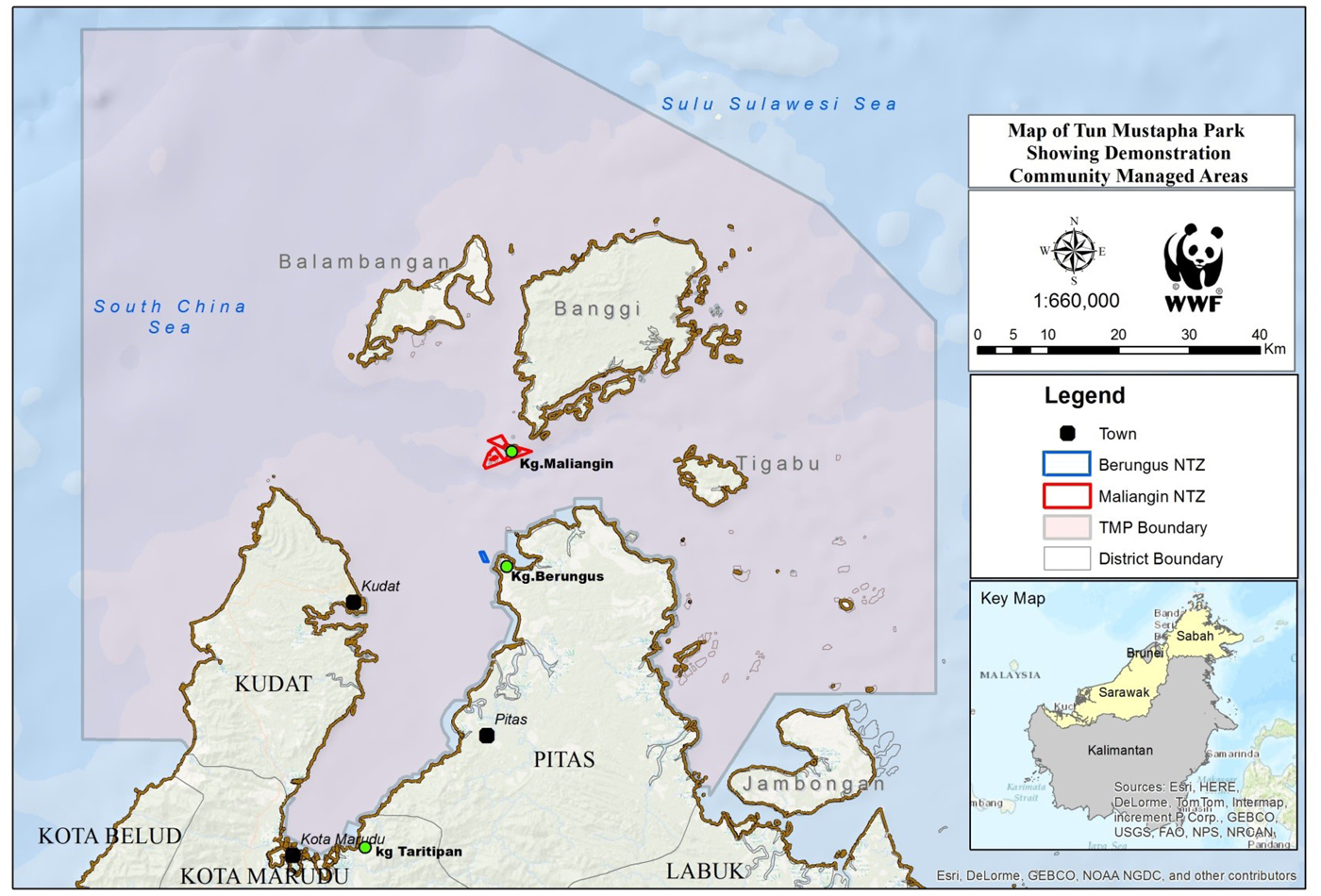

Officially established in 2016, and after 12 years of community consultation, the size of the Tun Mustapha Park (TMP) in northern Sabah was reduced from about 1.2 million hectares to slightly under 900 hectares of a multiple-use protected area. Nongovernmental organisations formed the bridge between official conservation and local communities living in the Park. No-take zones and community use zones were drawn and the mapping of natural resources completed. By contrast, the mapping of human populations was not systematically undertaken so that the distribution of ethnicities remains unknown, although a small-scale study in the Banggi Island chain confirmed that there were Bajau Ubian, and West Coast Bajau who dominate.Footnote 64

For some Bajau groups, exposure to bureaucratised ‘Malayness’ has produced opportunities when those categorised as ‘Bajau’ have become successful role models for others who belong to Muslim groups with smaller populations who otherwise would be officially categorised as ‘Other Bumiputras’ with not much political clout. For such small groups, masuk (entering; becoming) ‘Bajau’ is an essential element for being officially (re)classified as ‘natives’.Footnote 65 Since independence, the category ‘Bajau’ in Sabah has had state endorsement since it is the largest Muslim group, one whose political support is therefore important for the survival of any party in power (a vastly different connotation than the pejorative slang for ‘beggars’ associated with being ‘Bajau’ by Muslims in Manila and Davao because they are ‘not being Muslim enough’).Footnote 66 ‘Not being Muslim enough’ is also of concern to Sama di Laut, a small group of Bajau in Semporna on the east coast of Sabah, who settled in stilt houses in the 1960s and whose children try to overcome prejudice by being staunch Muslims.Footnote 67 The attraction for being ‘Bajau’ for Sama-speaking groups such as the Binaden and Ubian — who in the Philippines would not have identified themselves as Bajau — is driven by the view that ‘masuk Bajau’ is advantageous because of the clear Federal support being given in the history curriculum and textbooks produced by the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (the Malaysian Institute of Language and Literature). These textbooks have overturned the image of Bajau as untrustworthy, lawless kidnappers, replacing it instead with ‘Bajau’ having a history of defending Islam and of being ‘almost’ Malay for having an origin myth linked to the kingdom of Johor.

Similarly, many whose citizenship status is uncertain because of being undocumented (without the citizenship papers required by the state) or new Samal arrivals from the Philippines who would not normally refer to themselves as Bajau in that country, admit to being ‘Bajau’ to increase their chance of being included as ‘natives’.Footnote 68 Overall, Muslim coastal groups living in the Tun Mustapaha Park who are officially categorised as ‘Bajau’, hence Bumiputra, have a history of migration that transcend two modern nation-states, namely the Philippines and Malaysia. Most groups and individuals who conservationists deal with in the Banggi island chain and the Marudu Bay area of the Park (see Figure 3), were however, deemed citizens by virtue of having the Malaysian identity card (Mykad), although those who might not have the Mykad or new arrivals, would not normally attend meetings held with outsiders.Footnote 69

Figure 3. Map of Tun Mustapha Park showing demonstration (model) village and community-managed areas (no-take zones)

The implementation of ecosystems management at the Park meant enlisting as many coalition partners as possible, especially small-scale fishers. Steering as well as advisory committees were formed. The advisory committee membership was rotated largely among state natural resource and development agencies, the World Wide Fund for Nature Malaysia (WWF-Malaysia), district offices, university and private sector interests. Local communities were included only in the advisory committees (sustainable fisheries, sustainable development, ecotourism and recreation, coastal safety and security, communication, education and public awareness as well as community use zones). These committees have only an advisory role without substantive power to comment or make decisions.

Local small-scale fisher communities of Bajau Ubian, Binaden, Cagayan and others were not represented at the steering committee level because it was thought they were already well represented by the District Office and leaders of the Fishermen's Association. There was an assumption, therefore, that the District Office and Fishermen's Association, had at heart, the socioeconomic welfare of local communities, which could be inaccurate, as expressed by an Indigenous fisher:

I didn't know anything that there is a no fishing zone now, if I knew there was a meeting about this Park, I would have attended the meeting but I was not informed. I guess it is hard for people to come here due to our location … too far from town.Footnote 70

The fisher's statement reveals that it would be inaccurate to assume that they were well represented by government District Offices or the local Fishermen's Association, and it also shows that No-take zones (NTZs, marine protected areas) could be unpopular.

As a result of the consultation process many zones determining different usage were drawn up.Footnote 71 Two of the zones are of interest to this article, namely the community-use zone and the NTZ. The community use zones are fishing grounds used by local communities that are near the villages and that are usually used by them. There was also a scoring system used that is based on field data collected including village use, village population, sensitivity of the ecosystem, the presence of corals, mangroves, shipwrecks, sacred areas and fish aggregation areas. NTZs of interest to conservation are characterised by having good reefs and being of importance to the marine ecosystem. It goes without saying that these same areas are also good fishing grounds for local fishing communities. At times the interests of communities could coincide with that of conservation.

In the case of Berungus village it was suggested as a NTZ because it is like a family-owned reef. Berungus village, made up of Bajau Ubian fishers have been protecting their reef from damaging fishing methods more than ten years before we came in. As well, the reef area was in a good condition It was therefore considered worth protecting. So it makes sense to work with them in establishing a model village for community managed natural resources.Footnote 72

The Draft Plan of the Tun Mustapha Park envisioned management by consensus through committees. As it turned out the establishment of the NTZ could be fraught with internal and inter-community rivalry. The Berungus NTZ was opposed by other neighbouring communities who did not think that the Berungus area was a ‘private commons’ to be looked after by Bajau Ubian as an NTZ. With support from the Sabah Parks and the Fisheries Department, local wardens were appointed to monitor the area. The lack of understanding of ‘community’ in the making of environmental subjects has been well pointed out by Arun Agarwal and Clark Gibson.Footnote 73

Nevertheless, despite internal opposition and a flawed consultation process, the fact remains that the Park presents opportunities for local communities. For example, partly because of community needs, many zones marked as community use zones were taken out of the jurisdiction of Park management. Together with the return of some mangrove areas to the Sabah Forestry Department, the Park area was reduced from 1.1 million hectares to 898,763 hectares.

The appointed honorary wardens were also committed because they received acknowledgement from the local government, NGOs and politicians to manage the reef areas in their respective neigbourhoods. They also receive support from WWF-Malaysia in the form of facilities such as a boat and fuel for patrolling which they also use for fishing, a jetty, and training sessions to enhance their skills in managing the NTZ and ecotourism. ‘It's good that the NGOs are here at Berungus, the government departments became interested in us,’ said one fisherman.Footnote 74 It appears that conservation in addition to intensified Islamisation is another way that Ubian or Bajau Ubian as they call themselves, could improve their social standing, one which is now being emulated by an increasing number of communities in the Park who wish to have volunteer wardens appointed for their villages.

Conclusion

This article has shown how some Indigenous groups in Sabah experience the ‘Federal factor’ of bureaucratised Bumiputraism and Islamisation in different ways. We have shown how the bureaucratisation of Indigenous identities ‘fixes people’, ignoring the fluidity of self-identification. While conservation of the fortress variety excludes people, the inclusiveness of the environmental justice framework provides for the freeing up of images of Indigenous identities as forever tied to place and nature.

Environmental justice requires the recognition of the fluidity of Indigenous identities, so that a variety of landscapes are amenable to conservation, i.e. beyond pristine forests, coasts or seas, to places where ‘we live and play’. It takes a broader view about the relationship between Indigenous identity/ies, landscape and conservation so that the way people are treated in any society can be read from the way society treats nature. One example of improving relationships between humans and nature is via the FPIC concept. Melissa Marschke et al. suggest that working on increasing participation (in their case via environmentalism's interest in FPIC) is a path worth following for both research and practice.Footnote 75 Whether FPIC as a process can meet the needs of individuals and the collective is something to be investigated.

At least for the Murut, and proceeding from the reversal of the decision made by the High Court which upheld customary rights by virtue of prior occupation before the establishment of the forest reserve by the Apellate Court, an argument could be advanced using the FPIC concept. Two points might work in favour of the Murut. First, the Sabah Forestry Department acknowledged that the speed at which the new forest reserves were gazetted meant that ground verification was not conducted.Footnote 76 Second, Malaysia is signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity and in its periodic reports to the United Nations has acknowledged its obligations under the CBD. It is up to civil society to provide ‘reminders’ of Malaysia's obligations regarding FPIC.

Islamisation provides lowland Kadazandusun who have exposure to bureaucratised Islam, with productive power. It provides a basis for comparison of an imagined Kadazandusun sociocultural life about who they are not — not ‘Malayans’ and specifically not Malay. For some ‘Bajau’ groups, Islamisation provides an avenue for stepping up in the social ladder. Stepping up could further be enhanced by participating in environmental conservation through formal or informal appointments as trusted caretakers or stewards of the sea where they ‘work and play’; participation in conservation may also indicate an alternative avenue of power to the traditional one associated with being village head. In making such appointments, conservation NGOs might have gained pleasure in obtaining the support of community as well as state managers of natural resources. Might the informal ‘wardens’ appointed by NGOs at Berungus be gaining exclusive territory over an area of collective commons? The answers to these questions, which would require further investigation, could further sensitise us to why there was so much resentment to the informal power of surveillance given to the appointed community wardens.

NGOs involved in Indigenous rights and conservation movements in Sabah are themselves largely staffed by Bumiputras. They present Indigenous Peoples as being dependent on resources and have increasingly positioned themselves behind the conservationist calls for recognition of Indigenous ways of life as being threatened, and needing to be respected. We have argued that Indigenous Peoples have found leverage by emphasising indigeneity, through the environmental justice movement's concern for equity and participatory development.