One of the few nineteenth-century Malay descriptions of the reading majlis – a gathering of people to listen to someone read aloud from a manuscript, and perhaps take a turn themselves at reciting – appears in Safirin bin Usman Fadli's Hikayat anak pengajian.Footnote 1 A Batavian religious teacher, Safirin warned of the dangers of literary works, since ‘most of the stories contained in hikayat [prose narratives] are untrue and false and, therefore, they are unacceptable to the intellect and most harmful to the ignorant’. The sound of the recitation itself he held to be particularly perilous, since it had the power to induce among the weak of intellect ‘longing and love’, with the result that ‘people become mad’.Footnote 2 As Safirin notes, among those lacking in the rationality necessary to withstand the seductive powers of recitation are women: ‘To say nothing of women not having their hearts inflamed, when most men find that their hearts beat in time with the reader's voice as they listen to the hikayat's story.’Footnote 3 Going on to criticise a foolish reciter who allows himself to be carried away by the sound of his own voice, Safirin provides a clue as to what he considers the proper place of women in the gathering of readers. While reading aloud, Safirin claims, the ignorant reciter

listens intently to voices and movements behind the partition, inside the house in which the recitation of hikayat has been arranged. And the ignorant reciter thinks in his heart: ‘This must be women peeping from behind the partition in admiration of my voice. So crazy about it are they that they have stopped making coffee and frying bananas and sweet potato.’ This is what is on the mind of the shameless fool!Footnote 4

The brunt of Safirin's criticism is borne by this ignorant reciter, shown to be both vain and greedy. Safirin does not specifically treat the subject of women as readers or reciters, but in his depiction of the literary majlis, a woman's place is segregated and subordinate. She neither reads herself nor even sits in the room in which the recitation is taking place, but remains behind a screen or in the kitchen preparing food and drink for the men. Her relationship to literature is thus an illicit one, charged with prohibited erotic feelings for the male reciter's seductive voice, with all the perils that may bring — not least, a disruption in the supplies of refreshments.

Modern-day scholars of Malay literature also tend to assume that Malay women of the nineteenth-century were illiterate and uneducated, and that Malay literary culture was the preserve of men. In an article in Dewan Sastera, for instance, the Malaysian academic Jelani Harun asserts that, in the seventeenth century, ‘literacy, generally speaking, was only possessed by men’.Footnote 5 The Malaysian expert in Riau syair, Abu Hassan Sham, claims that the existence of syair (narrative poems) by women ‘shows that women in Penyengat in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were able to escape the image of mere secluded maidens or housewives and to stride towards giving birth to works, whether creative or didactic’.Footnote 6 The introduction to an edition of Syair Siti Zubaidah, by another Malaysian scholar, Abdul Mutalib Abdul Ghani, identifies one of the text's major themes to be female emancipation, ‘by which is meant that the tribe of Eve should not necessarily only play a role in the kitchen’.Footnote 7 In this view, women authors of syair are exceptional and progressive figures, breaking free from the shackles of tradition. Thus while Safirin bin Usman Fadli is at odds with his modern counterparts Abu Hassan Sham, Abdul Mutalib Abdul Ghani and Jelani Harun as to whether women ought to be confined to the kitchen, there is a consensus that so confined they were.

Other scholars of traditional Malay literature, however, have noted the presence of women readers. Drawing on the introductory verses to a manuscript from a mid-nineteenth-century Palembang lending library, Ulrich Kratz describes how the library's ‘male and female customers’ are ‘sitting close to the oil-lamp, bending over the manuscript, talking about the story while rolling it up and opening it again, holding it tight to the breast submerged deeply into text and conversation and plainly forgetting such trivialities as the fears expressed by the owner’.Footnote 8 Women are addressed directly in these introductory verses as ‘all you noble matrons’ when they are asked not to chew betel while reading.Footnote 9 As Kratz points out, the mention of women readers in these verses ‘is a very important inclusion, yet which is quite in line with the known fact that manuscripts very often were copied by women as well as by men’.Footnote 10 Here we have quite a different depiction of communal reading from that delineated by Safirin: the women are not behind the screen or in the kitchen, but gathered around the same oil lamp and the same manuscript as the men. It is likely that among the texts that these women readers pored over were romantic syair, or narrative poems, a genre often featuring female heroines and particularly popular in the nineteenth century. Vladimir Braginsky observes that this genre may have originated at least partly in the ‘tradition of Malay female court singers, biduan’, and that ‘the milieu of female palace singers, ladies-in-waiting and concubines of Malay rulers, as well as of their younger wives and relatives, was the preferred domain for the functioning of a considerable proportion of romantic syair. It is precisely in this domain and for this audience that they were often created, reflecting its ideals, norms and tastes.’Footnote 11 Along with such syair, there are also numerous extant didactic texts for women, attesting to a significant female reading public.

This divergence of opinion about women's literacy and engagement with literary activities in the early modern Malay world should be placed in the context of arguments about female literacy in Southeast Asia more generally. Two major recent studies of the region – Anthony Reid's Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce and Barbara Watson Andaya's The flaming womb – have very different views on the subject. Reid contends that, whereas literacy in many parts of the pre-modern world was the preserve of a small male elite, the situation in maritime Southeast Asia may have been quite different, with widespread literacy in indigenous scripts among both men and women.Footnote 12 He argues that trade and courtship were the impetus behind the unexpectedly high levels of literacy in pre-colonial Southeast Asia, particularly among women. Women engaged in trade, for which basic literacy and numeracy were essential. The exchange of love poems – especially the pantun, a four-line verse form – written on leaves or scraps of paper was an important part of courtship in South Sumatra and elsewhere. Strikingly, Reid puts forward the possibility that literacy declined from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries ‘because the more “modern” and universalist system of monastic education introduced by Islam and Christianity acted to suppress an older pattern of literacy of quite a different type’.Footnote 13

Watson Andaya, on the other hand, paints a bleaker picture, pointing to the dearth of written historical sources by women or expressing women's viewpoints.Footnote 14 In Watson Andaya's view, Reid is describing a form of literacy akin to that found among the Yao peoples in Hunan:

With a limited number of syllabic notations, a small vocabulary, and stock phrases, this script could be easily mastered and was employed to embroider lament songs on the fans or handkerchiefs that women exchanged as tokens of affection when (for instance) a bride left home to marry. In a context where formulaic writing is employed for very specific purposes, “reading” is more properly seen as memorized recitation, revealing much of culturally appropriate emotions but little of individual interiority.Footnote 15

In other words, the impressive literacy levels in indigenous scripts that Reid adduces for the Philippines and southern Sumatra do not imply “real” reading and writing but only a kind of frozen symbology. The surviving texts that this kind of literacy produces reveal only feminine formula rather than female experience. Nevertheless, Watson Andaya does note some exceptional women who managed to acquire an education, as well as female courtiers who may have been sources for court chronicles. The view here is not one of declining but of increasing literacy over the early modern period, with some trickle-down bonuses for women: ‘boys may have been the major beneficiaries as literacy was extended beyond elite circles, but as adults they were also inclined to educate their daughters’.Footnote 16 Finally, Watson Andaya attributes an increase in female literacy to foreign influence on southeast Asian cultures, such as VOC-sponsored schools for girls in seventeenth-century Ambon. ‘Throughout southeast Asia’, as she puts it, ‘there was still a persistent view that writing and reading were inappropriate skills for women.’Footnote 17

Female literacy and engagement with literary culture in the nineteenth-century Malay world may provide a counterpoint to these opposing scenarios. For the type of literacy under consideration here is by no means primitive, involving as it does the composition, recitation and copying of complex literary works, some composed of many hundreds of manuscript pages. Moreover, while female literacy was most common in elite circles, it was not a question of one or two exceptional women, or even of a single exceptional court. While all the known named female authors of the nineteenth-century Malay world come from the court of Penyengat, we will see that this is an effect of European philological intervention in the Malay manuscript tradition and that other centres, such as Banjar and Siak, were also home to literate and literary women. Female literary production in the nineteenth-century Malay world should not be seen as a sign of modernity, or as an eccentric activity undertaken by a few proto-feminists, or even as the sole preserve of members of the aristocracy, but as an accomplishment appropriate to educated women, including court attendants. Contradicting the commonly assumed association between modernity and female literacy, women's literacy and engagement with written literature has nothing necessarily to do with female emancipation or progress out of a patriarchal past.

I. Penyengat exceptionalism?

The existence of syair attributed to women from Riau has been noted by Abu Hassan Sham, Virginia Matheson and Edwin Wieringa, among others.Footnote 18 The only pre-twentieth-century texts in all of Malay literature to be attributed to named women authors are these Riau syair. Raja Safiah is said to be the author of Syair Kumbang Mengindra, Daeng Wuh of Syair Sultan Yahya, Raja Salihah of Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk, Raja Kalsom of Syair Saudagar Bodoh, Encik Kamariah of Syair Sultan Mahmud, Encik Tipah of Syair Sultan Marit and Encik Jamilah of Syair Yatim Nestapa. Three of these women belonged to a single family, that of the famed author of the Tuhfat al-Nafis, Raja Ali Haji bin Raja Ahmad: Raja Safiah and Raja Kalsom were his daughters and Raja Salihah was his sister. Was there something about Riau, or Penyengat, or indeed Raja Ali Haji himself that encouraged women's literary production? Two factors that set Penyengat apart from other Malay courts may have played a role in fostering women's engagement in literature there: the resurgence of syariah-minded Islam at the court of the Yamtuan Muda (the viceroy or under-king, who in theory ruled on behalf of the Malay Sultan in Lingga), and the Bugis heritage of the viceregal family. However, in the final analysis, neither of these factors can be adduced as the reason why all the named Malay female authors of the nineteenth century came from Penyengat. Ironically enough, as we shall see, this is because of the intervention of Dutch philologists in the Malay manuscript tradition.

The Bugis indeed had well-developed traditions of historiography and of palace women's involvement in the transmission of texts. A Dutch missionary searching for manuscripts in mid-nineteenth century south Sulawesi observed that:

In general the Native women, especially the female chiefs, are much more expert in Bugis literature than the men … Finally I looked no longer for the guru [religious teachers], but only for the pasura, i.e. those who occupy themselves with reading the sura or writings … One finds such people only among the chiefly women and similar old women who have been associated with the court for a long time.Footnote 19

But though the Penyengat aristocracy were proud of their Bugis origins, the cultural style and indeed the language of the court were Malay. In general, literary works from Penyengat appear to show no connection to Bugis forms. Raja Ali Haji's Tuhfat al-Nafis, while distinct from much of the Malay tradition, is shaped by Arabic rather than Bugis historiography.

Bugis cultural mores with regard to the position of women may be evident in the prominent role played in the early nineteenth century by Engku Puteri, daughter of one Yamtuan Muda, sister of another, and wife of Sultan Mahmud. As well as being the custodian of the royal regalia, financing her younger brother's pilgrimage to Mecca, acting as a mediator between warring Bugis factions and playing a key role in brokering dynastic marriages, Engku Puteri also commissioned at least three literary works: Syair Tengku Selangor, Syair Perang Johor and Kisah Engku Puteri.Footnote 20 The first relates the visit of Tengku SelangorFootnote 21 to the Dutch Assistant Resident Walbeehm in Penyengat. The author, one Encik Ismail bin Datuk Kerkun, states on the first page of the manuscript that:

It is striking to see Engku Puteri referred to as tuan penghulu (leader) and seri paduka (royal highness), words which are not used to describe her in Raja Ali Haji's Tuhfat al-nafis, where her role in dynastic affairs is thoroughly domesticated.Footnote 23 There is no doubt in Syair Tengku Selangor that her commands were to be taken seriously. According to the former Indian army officer Peter Begbie, Engku Puteri was also the patron of Haji Abdul Wahab, who ‘went to Pulo Pinigad, where he sought and obtained the countenance of Tuankoo Pootri, the most influential of the widows of the deceased Sulthaun, and became the High Priest of herself and the Royal Family, as well as that of the nobility’.Footnote 24 Haji Abdul Wahab is said to have translated the text now known as Hikayat Ghulam from Arabic into Malay, subsequently copied for Walbeehm and now in the Leiden collection.Footnote 25 All four of these texts survived only because of their connection to Walbeehm, so it is possible that there were more texts commissioned by Engku Puteri, or indeed by other royal women, that are now lost.

Yet even the striking prominence of Engku Puteri in public life may not be a specifically Bugis trait. Royal women who played central roles in politics and literature alike can be found elsewhere in island Southeast Asia. In eighteenth-century Java, Ratu Pakubuwana was an important figure at the court of her grandson, Pakubuwana II. As M.C. Ricklefs has shown, Ratu Pakubuwana commissioned texts as a way of advancing her agenda at court.Footnote 26 Like Engku Puteri, Ratu Pakubuwana derived much of her authority from her exalted lineage and personal spiritual prowess. Both women controlled access to the royal regalia, crucial for conveying dynastic legitimacy. Another example of a royal woman acting as a literary patron comes from seventeenth-century Aceh, where Taj al-‘Alam, ruling in her own right as the daughter of one king and the widow of another, commissioned a work on religious law, Mir'at al-tullab, from the Sumatran scholar Abdul Rauf al-Singkili. The next Acehnese queen, Inayat Shah, commissioned two works from him: Risalat adab murid akan syeikh and Sharh hadith arba'in, a commentary on a hadith collection.Footnote 27 Other religious works commissioned by the Acehnese queens are said to include Tibyan fi ma'rifat al-adyan, Kifayat al-muhtajin and Akhbar al-akhirat fi ahwal al-qiyamah.Footnote 28 This suggests that the production of literary works at the behest of a spiritually and politically important woman was not unheard of in the royal courts of maritime Southeast Asia.

The other feature of Penyengat that distinguished it from other Malay royal centres was its position in the vanguard of what Dobbin, in the Minangkabau context, has termed ‘Islamic revivalism’.Footnote 29 One of the chief ideologues of this revival was Raja Ali Haji. Born in 1809, the son of Raja Ahmad and grandson of Raja Haji, Raja Ali Haji spent several years in the Middle East and soon became, in the words of the Dutch Resident Netscher, ‘a scholar of great renown among his countrymen’.Footnote 30 After his cousin Raja Ali bin Raja Ja'afar became Yamtuan Muda in 1845, Raja Ali Haji became his advisor, both in matters of religion and in dealings with the Lingga court. He was also a leading member of the Naqshbandiyya Sufi order in Penyengat, headed by another cousin.Footnote 31 The Naqshbandiyya was opposed to innovation (bid'ah) and favoured engagement with the state through the provision of guidance to those in power.Footnote 32 This combination of theological conservatism and political cooperation is readily recognisable in Raja Ali Haji's works. No doubt with Raja Ali Haji's backing, the Yamtuan Muda banned gambling, cockfighting, the wearing of gold and silk, and the recitation of licentious pantun, so that, as the Tuhfat records, ‘there was nothing unseemly in the state’.Footnote 33 Though the idea that Raja Ali Haji was uniformly hostile to Europeans has been debunked by Jan van der Putten, it is nevertheless fair to characterise him, as Peter Riddell does, as ‘an arch conservative in his views’.Footnote 34

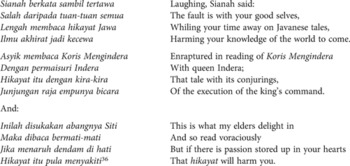

Raja Ali Haji's views on women and literacy may be gleaned from his didactic poem for women, Syair Siti Sianah. The eponymous heroine is a virtuous and pious woman and an exemplary wife. Her preferred reading material is the Qur'an and al-Ghazali's Ihya ‘ulum al-din, but her backsliding friends are stubbornly attached to the old romances like Hikayat Koris Mengindera.Footnote 35

It would seem from Syair Siti Sianah that Raja Ali Haji was in favour of female literacy, so long as women readers devoted themselves to religious texts — which those readers manifestly failed to do.

A closer look at Raja Ali Haji's views on women reveals them to be bracingly conservative — that is to say, rather more characteristic of the Middle East than of the Malay world. His collection of maxims known as Gurindam dua belas advises male readers to find a wife ‘who is able to submit’.Footnote 37 Addressing women, his tone is even more ominous: ‘the Lord of Glory will be wrathful / [if] you do not obey your husband's commands’. Rather, a wife should render her husband loyal and sincere service, bakti.Footnote 38 In Syair Siti Sianah, Raja Ali Haji condemns women's claims to their own property, persons or husbands, giving divine sanction to polygamy, female subservience and the use of violence against disobedient wives. Syair Siti Sianah teaches women the limitations of their rights and the onerousness of their responsibilities towards their husbands. In the section titled ‘the proper conduct of a wife towards her husband’, among the failings singled out for censure are public demonstrations of distress at the news that the husband has taken another wife, turning the face away or scowling at him, speaking harshly and refusing sex.Footnote 39 In Raja Ali Haji's didactic poem for men, Syair suluh pegawai, the sole stricture placed on the husband, in contrast, is that he refrained from striking his wife on the face.Footnote 40

On the whole, it would seem that Raja Ali Haji and the revivalist Islam he espoused would not have been especially conducive to female literacy and literary production. The syariah-minded bent of the Penyengat court also helps to explain why female literary production there took the form it did: narrative poems that bear many of the features of the old romances but eschew explicit sexual content or un-Islamic practice, and relentlessly stress the importance of the heroine's bakti towards her husband. Nevertheless, that Raja Ali Haji viewed learning to read as a part of a woman's religious duty is a significant feature that will be returned to below. Once a girl learned to read, of course, it would have been difficult to keep her to purely religious and morally improving works. There was a manuscript of Hikayat Koris Mengindera in Raja Ali Haji's own house, copied by women of the household.Footnote 41

Rather than Bugis ancestry or revivalist Islam, it was the presence of Von de Wall and his fellow philologist H.C. Klinkert that explains why Penyengat is exceptional in the Malay world as the home of all the known Malay women authors. In the Malay manuscript tradition, authors of romantic syair, male or female, did not have the same authority as authors of religious or dynastic works, such that even their names are rarely preserved. As Klinkert lamented in 1866 with regard to the syair manuscripts he collected, ‘[f]or most of the MSS I am unable to mention either the name of the authors, or the time of composition, or the place of origin, for these are unknown’.Footnote 42 For the most part, Malay secular literature must do without authors. The knowledge that Syair Sultan Yahya is attributed to Daeng Wuh, and that she was a woman attached to the Penyengat court, is entirely due to the intervention of Klinkert in the usually anonymous manuscript tradition. Six of the seven known women authors of syair come from Klinkert.Footnote 43

Klinkert's attention to provenance seems to have been unusual among European collectors, highlighted by Van Ronkel's belief, when he was compiling a catalogue of the Batavia Society's manuscript holdings in 1909, that information about previous owners and places of origin was irrelevant.Footnote 44 Just as unusual was Klinkert's interest in the low prestige texts of the Malay tradition: almost 60 per cent of his manuscripts, now held in the Leiden University library, are copies of romantic syair and hikayat. This attention to secular literature may have been prompted by his need to master a more literary style of Malay. He was engaged in translating the Bible into Malay, and had in fact already completed one version. The missionary society deemed its language too demotic, too redolent of urban Semarang, and therefore sent him to Riau.Footnote 45 It seems that he intended his translation to be both accessible and literary, and it is possible that his interest in syair – the popular form par excellence – should be seen in this context.Footnote 46

The name of the seventh woman author also comes from a Dutch philologist, Hermann von de Wall, who recorded on his copy of the manuscript that Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk was composed by Raja Salihah.Footnote 47Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk appeared in print in the Dutch journal Tijdschrift voor Neerlands Indië in 1847. In this published version, Raja Ali Haji is given as the author, on the basis of a letter sent by him to the journal's editor, Roorda van Eysinga, in which Raja Ali Haji refers to ‘Hikayat Sultan Abdul Muluk which I myself have versified in Johor Malay’.Footnote 48 Von de Wall lived for a time in Riau and knew Raja Ali Haji and his family circumstances very well; thus it is unlikely he would have made an error about the authorship of the poem. The Batavian publisher, Roorda van Eysinga, on the other hand, does not seem to have ever travelled to Penyengat or to have met Raja Ali Haji. Presumably, Raja Ali Haji or someone else in his family gave the manuscript to Von de Wall some time after the latter's arrival in Riau in 1857 and also gave him the name of Raja Salihah. One hypothesis is that Raja Ali Haji is the author, while Raja Salihah was the scribe who made Von de Wall's copy. In a letter to Von de Wall, Raja Ali Haji wrote of a manuscript that he was sending his Dutch friend, that it ‘is a text in refined Malay, though the calligraphy is defective and many of the words are defective, because it is a woman's writing’.Footnote 49 Both Raja Ali Haji and Haji Ibrahim complained about the difficulty and expense of finding competent copyists for the work they were doing for Von de Wall's dictionary.Footnote 50 Is it possible that Raja Ali Haji pressed some of his female relatives into working in his home scriptorium? Certainly he gave texts copied by women to Von de Wall as gifts (such as Surat Kurais) and loaned texts composed by women (such as his daughter Raja Kalsum's Syair Saudagar Bodoh) to Klinkert's own scribes to copy.

However, the alternative that Raja Salihah was responsible for a prose version or a different verse version of Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk which her brother revised or appropriated for publication seems on balance more likely. Raja Ali Haji was the indisputable author of numerous works, including many syair. However, none of the other syair belongs to the romantic adventure genre. Though they are often humorous – and in the case of Syair suluh pegawai distinctly ribald – they all convey didactic messages about religious practice or law. With its completely different subject matter and much greater length, Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk sits rather oddly among Raja Ali Haji's other syair. It is also the most likely of all his known works to appeal to a European audience captivated by Oriental literature (Goethe's West-östlicher Diwan appeared in 1819, Lane's English translation of the Arabian Nights in 1839). In 1838, Van Eysinga published in Holland a Dutch version of Syair Ken Tambuhan, which he recommended to his readers as a specimen of poetry ‘encountered among peoples who, being neither literate nor civilized, express themselves naturally, following quite artlessly the promptings of their feeling and imagination’: truly a Romantic recommendation.Footnote 51 One cannot therefore quite imagine Van Eysinga thrilling to the explanations in Raja Ali Haji's Syair Siti Sianah the necessity for ritual ablutions following a woman's menstrual period or to the risqué situations that arise from too-hurried divorce in his Syair Suluh Pegawai.Footnote 52 It is likely that, as Braginsky suggests, Syair Sultan Abdul Muluk or a hikayat of that title was composed, read and copied by the women of Raja Ali Haji's household and that Raja Ali Haji may have appropriated and reworked it.Footnote 53

The crucial intervention of Klinkert and Von de Wall underscores the fact that although all the known female authors came from Riau, these are not all the possible female authors. As Virginia Woolf observed, ‘Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.’Footnote 54 Traditional Malay literature is well furnished with anonymous texts, and it should not be assumed that they are all by men. Many texts – especially from genres which were considered ephemeral, like the romantic syair – will not have survived. The Malay manuscripts that are kept in libraries and archives today cannot be taken to be a complete or accurate representation of Malay literary culture, even of the relatively recent nineteenth century.Footnote 55 That the best evidence for female authors and copyists comes from Penyengat should not be taken to mean that such women were only to be found there. After all, Klinkert also collected manuscripts copied by women in Siak and Lingga. Ironically enough, it is only when women authors and copyists are mentioned in passing in documents exchanged between men that a female authorial presence in traditional Malay literature can be proven.

II. Women writers, readers and copyists beyond Penyengat

Literary depictions of aristocratic women from earlier times often mention their skills of writing and recitation. An impeccably educated princess in the sixteenth-century or earlier Hikayat bayan budiman is described as ‘erudite, knowledgeable about the art of syair, writing in a good hand, and possessing an understanding of astronomy’.Footnote 56 The heroine of Hikayat Putra Jaya Pati is depicted reading a Panji tale, while a court lady in Hikayat Isma Yatim is said to own a copy of Hikayat Inderaputra.Footnote 57 In Syair Sultan Yahya, the heroine Siti Jauhar Manikam studies religious texts and is able to recite the Qur'an in a pleasing voice.Footnote 58 The heroine of Syair Saudagar Bodoh even has the Qur'an memorised.Footnote 59 A syair from nineteenth-century Batavia by Muhammad Bakir (nephew of Safirin bin Usman Fadli, whom we have already encountered) has as its cast of characters a group of anthropomorphised fruits. The heroine is Anggur (Grape) and her companions include Rambutan, Duku and Cempedak. It seems clear that Muhammad Bakir, a man in the book trade who presumably knew his customers well,Footnote 60 is playing on a stereotype of women readers. As the syair observes,

All women enjoy hikayat

Reading syair and any kind of narrative

At all times and at every moment

For each one knows her letters.Footnote 61

The depiction of women's reading in literary texts is obviously idealised, a quality to accompany the heroines' always peerless beauty and occasional ability to fly. No less idealised is their choice of texts: romantic prose narratives show her reading other romantic prose narratives, while in the more strongly Islamised Penyengat syair she reads only the Qur'an.Footnote 62 Documentary sources, however, show that women reading and writing – for pleasure or spiritual profit – were not merely literary tropes.

Colophons and accession records of manuscript collections indicate that women often owned books and circulated them between themselves, sometimes for a fee. Based on her research in Kedah, Kelantan and Terengganu, as well as recent offers of sales of manuscripts to the Malaysian National Library, Siti Hawa Haji Salleh remarks that hikayat were frequently read by palace women.Footnote 63 Indeed, better data on ownership may be gleaned from the catalogues of the younger manuscript collections – such as those in Malaysia and Indonesia – than from the older European collections. Although the manuscripts themselves do not usually date from much before the late nineteenth century, they provide information about a chirographic tradition that was still alive, if not flourishing, when they were copied. Among the manuscripts owned by women and now in the collection of Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka are a 1910 copy of Hikayat Koris Mengindera that belonged to al-Hajjah Mariam binti Muhammad Amin, Laksamana Perak;Footnote 64Syair Dewa Syah Syarif donated by Cik Soda in 1963; Syair Raja Muda Perlis purchased from Sharifah Hanum binti Syed Hamzah; Syair Sultan Mansur bought from Tengku Zamzam; and three fragments of Hikayat Syamsul Anwar that belonged to Tengku Zamzam, Sharifah Mastura binti Syed Shahabudin and Tengku Kalthum binti Sultan Abdul Hamid.Footnote 65 In the Malaysian National Library's holdings are a Kitab tawhid, owned and possibly copied by Encik Zainab binti Tuan Khatib Abdul Karim al-Sambawa; Bayan al-shirk, copied by Encik Aminah; and Doa kanzil ‘arasy owned by Hajjah Fatimah binti al-Marhum Tuan Haji Abdul Hamid.Footnote 66 Other religious texts owned by women – suggesting that the depiction of them reading only romances is not quite the truth – are the didactic compendia of Nyonya Sawang, including tales directed at women, such as Hikayat Darma Ta'siah and Hikayat Fatimah bersuami; a similar compendium of religious works belonging to Nyonya Halimah; and Tarikah ‘Alawiyyah belonging to Nyonya Tasnim.Footnote 67 The women's names confirm that, for the most part, they belonged to the most privileged strata of society — princesses and daughters of high court officials, sayyids and religious notables.

How books circulated within this elite group is suggested by a note at the end of Klinkert's manuscript of Hikayat Syah Firman, one of eight bought from a selir or secondary wife of the Yamtuan Muda of Siak:

Hikayat Tuan Puteri Nurlela was borrowed by Rasyimah on the fourth day of Rabia’ al-Awwal in the Dutch year 1863, and was read for two nights. Just before the third night it was returned to its owner. For that we express our profuse thanks, because we greatly enjoyed hearing about the exploits of Syah Firman and his brother, together with his wives Tuan Puteri Indrasuka and Tuan Puteri Nurlela Cahaya.Footnote 68

Another example of a text transmitted by a network of royal women is Hikayat Syamsul Anwar, written by Raja Aisyah Sulaiman, a granddaughter of Raja Ali Haji, in 1890. Out of the five surviving manuscript copies of the text, three come from royal women.Footnote 69 The three fragments suggest that the text was literally parcelled out between various women. The conclusion of this manuscript traces its copying history: ‘This was composed by Raja Aisyah binti Raja Haji Sulaiman, Raja Pulau Penyengat, and copied by her humble close companion on the 14th of August, 1917, which equates with the first of Syawal, 1325. And the hikayat was copied once more by this humble servant in Alor Setar, the town of the country of Kedah, and was completed at 12.30 on Friday, the 18th of Dhu'l-Hijjah, 1351 [1933].’Footnote 70 The Kuala Terengganu manuscript of Hikayat Syamsul Anwar demonstrates a similar movement between royal women. Its colophon states that the hikayat was copied in Singapore in 1917 from a copy belonging to Tengku Fatimah Puteri al-Marhum Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor. Further on, the readers are informed that Tengku Ampuan Mariam had asked permission from Tengku Fatimah to copy the manuscript and, that being granted, wrote it out into 33 notebooks in 1947. The manuscript, therefore, would seem to have come from Raja Aisyah or the Yamtuan Muda family in the first instance, before passing to and perhaps being copied by the Johor princess, and from there going to the Terengganu princess. Ties of blood are obviously important in the transfer of the manuscript — the three royal families of Terengganu, Johor and Riau were related. Just as significant is the absence of the print medium and of intervention by male relatives. Manuscripts evidently circulated through the personal connections between royal women, and were copied by the women themselves. Tengku Ampuan Mariam owned a number of other manuscripts, including Hikayat Isma Yatim, and also compiled a handbook of Terengganu court dance.Footnote 71 Rather than being a modern innovation, Tengku Ampuan Mariam's interest in belles-lettres was more probably part of a long-established tradition: literature, like dance, was a courtly pastime appropriate to royal women. Although these copies date from the dying days of the Malay manuscript tradition, it stands to reason that if Tengku Ampuan Mariam was willing to copy a manuscript by hand as late as 1947, when printed reading material was widely available, such a practice would have been even more widespread a century before.

Of course, manuscripts were not always loaned disinterestedly — another common way for them to circulate was by being rented out for a fee. Encik Wuk binti Tuan Bilal Abu of Penyengat owned a copy of Syair Sultan Mansur (Klinkert 129) which she sold for 6 ringgit and 2 rupiah in 1863, as the buyer noted at the beginning of the manuscript. This new owner also warned that one should not allow the manuscript to be copied since ‘it is difficult to find and seldom available to buy, [and] because in this work a very beautiful story is related and of ten other copies not a single one is complete’.Footnote 72 Manuscripts were obviously a valuable commodity, and owners did not scruple to restrict their circulation in order to maintain their rarity.

Apart from the surviving manuscripts attributed to or copied or owned by women, there are significant numbers of nineteenth-century letters by and from women still extant.Footnote 73 Literacy among women was not restricted to the aristocracy, judging by the letters from Maimunah at Siak Seri Inderapura to her father; from the brother and sister Ambon and Soenah in Pasuruan to their sister; from a wife in Malacca to a younger brother in Siak; from Kumpul and Maimunah of Siak again to their brother Encik Anbu in Rantau, among others.Footnote 74 The six letters sent by a Bengkulu woman to John Marsden in the late eighteenth century show, as Kratz writes, that she ‘was a person of some education, even if it cannot be established presently if they were put to paper by Ence’ Lena personally or were perhaps written with the help of a professional scribe'.Footnote 75 Of course, these letters could have been written by male relatives or professional letter-writers, but there seems to be no need to assume that a priori. While some letters were written by scribes, such as one from from the wife of Tunku Raja Muda Selangor to Francis Light,Footnote 76 there is no need to assume that she was illiterate. Just as a modern secretary might take a letter for his or her superior, Lebai Abdul Khatib took down Tunku Raja Muda's wife's directives regarding the shipment of tin, cloth and rice she was sending to Light. There are also extant letters from Siti Sabariah Cahaya Alam of Kedah to Light, from William Farquhar to Tengku Puteri Riau (1819), Sultanah Siti Fatimah of Pamanah, southern Sulawesi, to Farquhar (1822) and from the Dutch Resident of Riau, C.P. Elout, to Tengku Puteri again.Footnote 77 As evidence not only of elite women's literacy but also of their involvement in trade and administration, these letters make an important modification to the assumption that nineteenth-century Malay women were cut off from the world of business and government. Another source which suggests that women sent and received letters is the tarasul, or letter-writing manual. At least one such manual contained models of letters to sisters, wives, mothers and lovers.Footnote 78 Love letters, indeed, were a major epistolatory genre.Footnote 79 Examining undeliverable letters from the van der Tuuk collection, van der Putten remarks on several examples from women, including ‘wives writing to their husbands urging them to come home’.Footnote 80 An early nineteenth-century manuscript now in the British Library is a sample of the sort of verses appropriate for a love letter. These are pantun, the genre par excellence of Malay amorous poetry, recited in courtship games or scribbled on scraps of paper or leaves and smuggled between lovers. A reference to paper (‘Dutch paper carried by the wind / Yellowy white, let my mistress receive it’)Footnote 81 suggest that the verses were intended to be delivered by letter, not orally. Obviously, Surat kirim presupposes that the beloved could read, or at the very least had access to a literate confidante.

A further important source for women's literacy in the Malay world are the earliest census reports to take note of literacy, the 1920 and 1930 censuses of Netherlands India and the 1921 census of British Malaya. Reid points out that the censuses of Netherlands India ‘recorded the highest literacy anywhere in Indonesia not in those provinces where the modern school system was most widespread (North Sulawesi and Ambon) but in the Lampung districts of southern Sumatra. In 1930, 45 percent of adult men and 34 percent of adult women could write, and in contrast to the usual “modern” pattern the older age groups had higher literacy than the younger.’Footnote 82 Of course, 1930 was not 1830, and in any case the colonial census must be handled with care. As Reid observes, there may have been a bias in favour of the languages and scripts known to the census takers, thus tending to suppress figures for local scripts.Footnote 83 Moreover, if the data were obtained by interviews with male heads of households it would then be particularly suspect in the case of female literacy. Yet both of these possible biases would tend to suppress rather than exaggerate the number of female literates.

The Netherlands India censuses are particularly interesting in light of the findings of the Census of British Malaya, which also recorded levels of female literacy so high that the official report deemed them ‘unduly’ so and cast aspersions on the abilities of the census takers.Footnote 84 The census surveyed 15 large towns in the Malay Peninsula and gave percentages of the Malay male and female population who were literate. The highest rate of Malay female literacy was in Klang, at 22.4 per cent, with Telok Anson not far behind at 21.9 per cent. On average, 13.1 per cent of Malay women in these 15 towns were literate, as compared to 41.2 per cent of Malay men, giving a ratio of male to female literates of 1:3.1. This is an unusually high level of literacy for communities in which a formal education system had yet to reach the vast majority of the population. Accordingly, Nathan, the author of the official report, concluded that its findings had to be false:

In all the towns of the Federated Malay States, however, except Kampar, the number of females returned as literate is so large compared with the figures for Singapore, Penang and Malacca that considerable doubt must be felt as to the accuracy of the returns. The percentage of literates in the female population of Ceylon towns was 35.2 in 1921, but Ceylon is far in advance of Malaya in the matter of female education.Footnote 85

In other words, Nathan believed that women achieved literacy only through the colonial school system. In the Federated Malay States, this system was not much to speak of, therefore women's literacy must be low and the census returns flawed. In combination with the Netherlands India censuses, however, a far more plausible explanation is that high levels of female literacy in Malay society had little to do with colonial schooling.

Rather than being a result of modernity, female literacy in the Malay world must be explained otherwise. The census data comes of course from the early twentieth century, but given the other evidence, the existence of literate women can be extrapolated into the nineteenth century and earlier. In 1890s Banjar, for instance, Den Hamer described a community of women readers and manuscript copyists who almost certainly never sat behind a desk in a Dutch school. They are, he wrote, ‘mostly women, who write down the syair with pen and ink on Dutch paper. With a mistar it is lined, that is a small board with cords stretched across it. A smooth pressure of the hand creates the lines. There are also many women who are able to read but cannot write.’Footnote 86 These women were engaged in copying out passages of syair to be recited during the vigil kept on the night of a birth.Footnote 87 Writing of the great boom in Malay commercial book printing that took place in 1880s and 1890s Singapore, Proudfoot notes that this ‘great upsurge … cannot have been accompanied by a commensurate rise in literacy rates. It follows that even at the low levels of literacy obtaining in the nineteenth century, there was an unfulfilled capacity for the consumption of literary material.’Footnote 88 Van der Putten has asked how Malay-language printing could have flourished if, as colonial and later studies have assumed, Malays were living in a ‘dark world of illiteracy’.Footnote 89 The implication must be that, if commercial publishers in Singapore felt confident enough to put out some 50,000 books in 1890 alone,Footnote 90 literacy rates in the late nineteenth-century Malay world were not as low as has been assumed. There were enough literates to create a printing boom, and enough literate women to make texts intended for women readers the most frequently republished of all.Footnote 91 But if this was the case, how did this reading public come into being?

III. Islam and female literacy in the Malay world

It has been suggested that Islam may have played the definitive role in the spread of literacy outside courtly and priestly circles, and even to have been the prerequisite for the development of written Malay literature.Footnote 92 Islam's emphasis on the ability to recite the Qur'an meant that reading – that is, the ability to recognise the Arabic alphabet and produce the corresponding sounds – was required of all believers.Footnote 93 Much of the evidence for female literacy in the Malay world reviewed above comes from court centres that were also, almost by definition, centres of Islamic learning. Might the relatively high levels of female literacy be due to the influence of Islam itself? How did Islam affect the transmission of female literacy in the Malay world?

A glance at the situation in other Islamic cultures might be helpful, though statistics are difficult to come by and making the comparison to the Malay case is not straightforward. Women's education in Egypt is, fortunately, relatively well mapped. Here, according to Baron:

Daughters of the ulama and others had occasionally been taught by tutors in medieval times, and this pattern persisted into the early nineteenth century. Edward Lane found in the 1830s that although female children were seldom taught to read and write, a shaykha (learned woman) sometimes instructed the girls of the wealthiest families, and that a few middle-class girls attended school with boys. The central text for these lessons was the Qur'an … If taught to read at all — and few were — women were taught in order to read religious works.Footnote 94

By the first half of the nineteenth century members of the religious establishment had begun to lend their voices to promoting female education, but even so, the rates remained dismal.Footnote 95 An 1897 census in Egypt indicated that 8 per cent of men and 0.2 per cent of women were literate.Footnote 96 In other words, for every literate woman there were 40 literate men. Literacy rates for women rose markedly – up 50 per cent by 1907 – with the spread of state-sponsored education for girls.Footnote 97 The Netherlands Indies census suggests that, while literacy as a whole was more restricted in Riau in 1930 (5.56 per cent) than in Egypt in 1897 (about 8 per cent), the ratio of male to female literates was far more favourable in Riau (1:10) than in Egypt (1:40). This suggests that gender was less of a barrier in attaining the skills of reading and writing in Riau than it was in Egypt. While the spread of a more syariah-minded form of Islam through the Malay world in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may have tended to work against older cultural patterns that encouraged female literacy, girls still seem to have learned to read as a central component of their basic religious education.Footnote 98 The greater authority and autonomy accorded women in the Malay world, as opposed to the Middle East, must have played the definitive role.

Nevertheless, it seems likely that when girls in places such as Penyengat learned to read it was as part of their religious education. The ‘traditional system’, as described by Tucker for Egypt, has many resonances for the Malay case: ‘girls, particularly the daughters of literate parents, commonly studied with boys, at least until they reached age ten or twelve, in many of the kuttabs scattered throughout the country, or, if their parents could afford it, with private tutors at home’.Footnote 99 Private tutoring seems to be implied in a marginal verse in Raja Ali Haji's Syair Siti Sianah, cautioning against allowing one's daughters to study Qur'an reading with a male teacher.Footnote 100 By implication, then, women were available to provide such instruction, like the two Malay women in 1850s Penang who supported themselves by teaching.Footnote 101 Of course, Abdullah bin Abdul Qadir Munsyi recorded in his famous memoir that it was his paternal grandmother, Pariaci, who first taught him the rudiments of writing and that she ran a school where over 200 students, both boys and girls, studied Qur'an reading and other subjects: ‘All sorts of people studied with her; some studied writing, others studied letters and Malay, each according to his or her wishes. Almost all the children in Malacca came to study with her.’Footnote 102 Whereas Watson Andaya cites Pariaci as an example of how a woman acquired literacy thanks to her literate (and presumably enlightened) father,Footnote 103 what the Hikayat Abdullah reports is rather the striking fact that the man identified as the founder of modern Malay literature learnt to read and write from a woman.

More recent anecdotal evidence confirms the pattern of early childhood education – for both boys and girls – being provided by women teachers. In his memoirs of growing up in an aristocratic Negeri Sembilan family at the beginning of the twentieth century, Tan Sri Datuk Dr Mohamad Said relates how he was sent to Qur'an reading classes taught by two women, Wan Neng and Wan Teh. He is careful to point out that these early teachers, with whom he studied until he completed the Qur'an at the age of nine, ‘had no special qualifications, and could not be considered authorities on how each word of the Koran should be pronounced’.Footnote 104 Having escaped from Wan Neng's ‘unsparing use of the rattan’, he passed on to more highly qualified male teachers, who had either studied in Mecca or were affiliated with revered religious leaders, in the company of other boys of good family.Footnote 105 It seems that the boys – exclusively – who continued on to further study then passed to a more highly qualified man for religious instruction, or, with the establishment of the colonial educational system, to a secular school. Women teachers could not, it seems, aspire to the same kind of status as their male counterparts. Based on van den Berg's report on Islamic education in the Netherlands Indies in 1885, Dhofier writes that female students were enrolled in the two basic levels of schooling, but ‘only male students were permitted’ to attend pesantren, the highest level.Footnote 106 The traditional system turned out girls with enough literacy to read and write, and in some cases to educate other children in turn, but barred them from further progression.

Though girls in the Malay world learned to read and write Jawi for their religious benefit, often they seem to have used this knowledge to read romances. We have already seen how both Raja Ali Haji, in his polemic against romance in Syair Siti Sianah, and Muhammad Bakir, in his depiction of hikayat-crazed female fruits in Syair buah-buahan, associated women readers with secular romance. Tan Sri Mohamad Said recalls that his grandmother, mother and two aunts ‘were all avid readers of hikayat and syair’.Footnote 107 A certain Hikayat Bustaman was the favoured reading material of his aunt and his rattan-wielding Qur'an teachers: ‘one day my aunt Khatijah showed me a beautifully hand-written copy of this hikayat which she had, with the greatest difficulty, succeeded in borrowing from Sharifah Rogayah, the mother of my Koran-reading teachers, Wan Teh and Wan Neng’.Footnote 108 It is an eloquent testimony of the way women acquired literacy that, barred from higher education, they turned instead to hikayat and syair. Of course, women continued to engage with religious discourse: Mohamad Said recalls how his grandmother, mother and aunt frequently discussed religious subjects,Footnote 109 and, as we have seen, there are several surviving religious manuscripts that were copied or belonged to women readers. Indeed, apart from prose and verse romances, there is a substantial corpus of nineteenth-century Malay didactic literature for women, attesting once again to a significant female audience.

IV. Conclusion

Women in the nineteenth-century Malay world were not restricted to eavesdropping on men's hikayat recitation. They read, copied and indeed composed their own texts. They were both patrons and hirers of manuscripts. Far from being an exclusively Penyengat phenomenon, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries women readers, owners and copyists of manuscripts could be found across the Malay world: in Banjar, Palembang, Siak, Lingga, Bengkulu, Batavia, Kedah, Kelantan, Selangor, Terengganu, Perak and Johor. The assumption that literacy was the sole preserve of men in the pre- or early modern Malay world is unfounded. While the type of secular literacy in indigenous scripts that Reid describes for south Sumatra, the Philippines and Bali is not the same as literacy in Jawi, the literate women of the nineteenth-century Malay world suggest that the older pattern had adapted and transformed into a new form. Though girls now learned to read and write ostensibly for religious purposes, female literacy was relatively common — even unusually so. The view that female literacy occurred only in very exceptional cases and that no ‘distinctively’ female texts can be found may be unduly pessimistic, at least in the Malay case. The literate and literary women of the nineteenth-century Malay world produced a large number of still extant texts, ranging from magical guides to compendia of didactic tales to romantic syair and hikayat, much of which have yet to be examined for what they may reveal of women's history.