The Ethical Policy, which the colonial administration in the Netherlands Indies adopted as a guideline at the beginning of the twentieth century, was not only aimed at uplifting and developing ‘native’ society: it went hand in hand with large-scale military expeditions. The Dutch mission to bring ‘modern civilisation’ to the archipelago was based on the idea that the ‘uplifting’ of the population could only be achieved by establishing firm colonial control. Therefore, the Dutch ‘white man's burden’, or mission civilisatrice, was in large parts of the archipelago accompanied by intimidating violence, creating a regime of fear that resonated in local memory for years to come.Footnote 1

Most historians have considered the late-colonial state that the Dutch established in the Indonesian archipelago after 1900 as self-evident, needing no further explanation. Yet, it is amazing that such a vast archipelago, populated by more than 60 million people in 1930, could be governed by only a handful of Europeans. At that time the European population consisted of 240,000 people and formed only 0.4 per cent of the total population, while the heart of the colonial state consisted of a Civil Service of approximately 100,000 people, 15 per cent of whom at the most were European.Footnote 2

The establishment of a state of violence is not the principal explanation for the relative ease with which a small European minority controlled the archipelago. More important was the efficient way in which the colonial administration employed a system of indirect rule both on Java and in most parts of the so-called Outer Islands. As Heather Sutherland explained in her study on the indigenous administrative elite (Pangreh Pradja) on Java, an incorporated aristocracy provided colonial authority a ‘traditional’ face.Footnote 3 Although indirect rule gave the impression of maintaining the status quo, sociologist J.A.A. van Doorn emphasised the interventionist and innovative capacity of the late-colonial state. In his book De laatste eeuw van Indië [The last century of the Indies], he outlined the colonial administration as a technocratic project, in which agricultural extension, expansion of irrigation, railways, education, healthcare and credit banking formed key elements. Moreover, the colonial administration aimed at systematically rearranging social relations through a paternalistic form of social engineering. According to Van Doorn, the innovative engineer eager to implement developmental blueprints, and not the conservative administrator wanting to maintain the traditional forms of authority, was the role model for the ambitions of the late-colonial state.Footnote 4

Taken together, violence, indirect rule and an interventionist technocracy may seem to provide a sufficient explanation for the degree to which the Dutch succeeded in maintaining their hold on the ‘Tropical Netherlands’ until 1942. Central to this approach is that the success of the colonial state is exclusively attributed to the administrative agency of the Dutch authorities. However, such a top-down perspective fails to consider the essential role played by indigenous (lower) middle classes in sustaining the colonial system.

The political importance of these middle classes has been emphasised because they were seen as the breeding ground of the nationalist movement. Prefiguring an idea launched by Benedict Anderson, Dutch anthropologist Jan van Baal described how the rise of the nationalist movement, originating from the urban middle classes, developed within the confines of the colonial state.Footnote 5 Already in 1976, Van Baal emphasised that for the nationalist movement the colonial boundaries formed the natural borders of the new nation. These middle classes consisted of lower civil servants, teachers, medical personnel, railway employees, clerks of European companies and journalists. By leaving their former, local surroundings, the colonial state was becoming their new habitat.

In most of the literature there seems to be a consensus about the logical and linear connection between the rise of indigenous urban middle classes as a motor for either modernisation (Willem Frederik Wertheim) or modernity (Adrian Vickers), and the rise of the nationalist movement.Footnote 6 But this sequence of urbanisation, rising middle class, and the spread of modernity and nationalism, obscures two important features concerning the nature of these indigenous middle classes.

First, the radical nationalist movement of the 1920s and 1930s formed a minority amidst many other organisations striving after less radical goals. Hans van Miert was right when he stated that the historiography of Indonesian nationalism has a teleological nature, due to which more moderate, culturally or regionally oriented organisations tend to be overlooked. In contrast to mainstream historiography, in which secular nationalism is depicted as a coherent and inevitable development, he describes a fragmented field in which a variety of regional, cultural and religious organisations operated, which were less radical than the nationalistic parties led by Soekarno, Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir.Footnote 7

Van Miert was not the first to point to the blind spots in nationalist historiography. In an important, but little-noticed, article William O'Malley had already questioned the way that nationalist historiography had monopolised the past.Footnote 8 The nuance O'Malley wanted to bring forward was completely overshadowed in 1983 by Anderson's Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism.Footnote 9 This offers a streamlined narrative, in which regional organisations (Jong Java, Jong Sumatranen Bond, etc.) eventually gave way to a successful secular nationalism under the leadership of Soekarno. However, O'Malley had pointed out that among the followers of the radical nationalist organisations there was primarily an anti-colonial attitude rather than an outspoken pro-nationalist conviction. Moreover, he showed that on a regional level moderate organisations were able to mobilise many more followers than the radical nationalists. As an example, O'Malley mentioned the Pagoejoeban Pasoendan in West Java and the Pakempalan Kawoelo Ngajogjakarta in Central Java. Apart from serving socio-economic interests, these organisations were mainly culturally oriented and regionally anchored. According to the principle that the winner takes all, Indonesian nationalist historiography eventually monopolised the past for itself. In doing so it obscured internal differences within the nationalist movement, while it ignored less radical mass organisations with a cultural and regional orientation, which had in the late colonial period a much larger following.

Second, the linear nationalist approach also conceals the fact that the majority of the indigenous native middle classes were not primarily interested in joining the nationalist movement. Instead, it is my hypothesis that they were primarily interested in modernity. What they aimed at in the first place was not a nation, but a lifestyle. And access to such a lifestyle could be obtained by joining the framework of the colonial system and in doing so consolidating the colonial regime. The connection between embracing a modern lifestyle and supporting the colonial regime could be very direct: for the majority of the indigenous students, higher education was expected to result in an appointment with the government.Footnote 10

In 1930, at least half a million people belonged to the higher and lower native middle classes in the Netherlands Indies, while about half of them had some proficiency in the Dutch language. The vast majority of the indigenous middle classes were connected to the colonial state because they had either a government job or were employed by an institution closely related to the colonial state.Footnote 11 This is not a large amount of people compared with the estimated workforce of 20 million people at that time, but it was this subaltern group in particular that sustained the colonial system.

The relations between a regime and its subjects are complex and cannot exclusively be understood in strict institutional terms. Recent anthropological studies on the nature of the state emphasise the informal interface between state and society and in particular the way in which the state is embedded in society.Footnote 12 Such an approach is relevant to understanding the political importance of the indigenous middle classes in the Netherlands Indies. They were positioned in the border area between colonial state and society, where they anchored the regime into society. It was in the same border area where they were confronted with the appearance of modernity, to which they actively gave shape in their own lives.

I am fully aware of the fact that modernity is a fashionable container concept. It refers to ideas derived from the Enlightenment; it is closely connected to the development of capitalism and it is particularly expressed in urban surroundings. Modernity refers to the role of the individual and to equality, to notions of development, progress and mobility; it creates room for the new. It has been suggested that apart from a hegemonic Western modernity, separate colonial modernities or alternative modernities could exist. Historian Frederick Cooper objects to such a differentiation, because it suggests that these alternative forms were derived from an original and, by implication, superior western modernity. Instead, he prefers to investigate how certain groups of people in very specific situations claim particular aspects of modernity and give shape to it.Footnote 13

Elsbeth Locher-Scholten rightly points out that for many people in Asia the West was not the sole source of modernity: Japan offered equally important examples. Miriam Silverberg and Harry Harootunian offer excellent studies of how Japanese middle classes appropriated modernity in the pre-war period.Footnote 14 Harootunian emphasises that modernity took shape in everyday life, in fashion, media, transport, work, leisure and family life. Because most people experienced modernity in this everyday context, we need to make everyday life the object of research.

Silverberg and Harootunian based their analysis on extensive studies on daily life by Japanese researchers in the pre-war period. Compared with the many sources on Japan, research on this topic in the Netherlands Indies and Indonesia is, however, very scarce. For this reason the following remarks on this subject regarding the Netherlands Indies are necessarily of a preliminary and hypothetical nature.

In Women and the colonial state, Locher-Scholten addresses the problematic nature of the notion of ‘colonial citizenship’. According to her, this concept should not be understood in a political sense, because the civil rights of colonial subjects were very limited. Therefore she places ‘colonial citizenship’ in a wider cultural context and sees the colonial state as a cultural project in which modernity played a key role.Footnote 15 This approach is helpful because it offers an opportunity to get away from the teleological perspective of nationalist historiography, and to look instead at the way in which the middle classes wanted to participate in a new modern lifestyle within the framework of the colonial state. Despite the risk of creating conceptual confusion, I propose to use the term ‘cultural citizenship’ in this context.

Coined by Renato Rosaldo, the term ‘cultural citizenship’ was primarily used to identify the position of ethnic minorities and other marginalised groups in the United States and in Southeast Asia and to explore their possibilities to achieve empowerment and emancipation.Footnote 16 Whereas full citizenship refers to law, equality, and the rights and duties of the individual, cultural citizenship stands, according to Rosaldo, respectively for culture, difference, and the identity of marginalised groups. This is not the place to discuss the problematic relationship between legal citizenship and cultural diversity in contemporary contexts.Footnote 17 My intention is to move the notion of cultural citizenship back in time to the late colonial period. In the context of the Netherlands Indies cultural citizenship should not be applied to marginalised ethnic minorities but to the indigenous middle classes who inhabited the very centre of the late colonial state. In contrast to the small and predominantly white minority who ruled the colony, these middle classes were denied access to political power. Through educational programmes and commercial advertisements they were, however, explicitly invited to abandon traditional habits and to become the new cultural citizens of the colony. Colonial citizenship was therefore primarily cultural citizenship.

There is, in contrast to the conventional historiographical sequence of urban middle classes, modernity and nationalism leading towards resistance and revolution, room for an alternative approach in which urban middle classes, modernity, everyday life and the colonial state formed the key components of cultural citizenship. To get a first impression of the way in which modernity took shape in the everyday life of the indigenous middle classes in the Netherlands Indies, I suggest to look at advertisements and school posters as expressions of what Ann Stoler – be it in a different context – has called ‘an education of desire’.Footnote 18 In the late colonial period the indigenous middle classes were exposed to a desirable lifestyle, which they could acquire through the purchase of particular objects and specific ways of doing things. It is my hypothesis that through advertisements and school posters the indigenous middle classes were not only introduced to new lifestyles, but the pictures also reinforced the interests of the colonial regime.Footnote 19

The following advertisements are drawn from the magazine Pandji Poestaka from the first quarter of 1940.Footnote 20 The magazine, which appeared twice a week, was published by the publishing house Balai Poestaka. With a circulation of 7,000 copies it reached the higher indigenous middle classes, informing them about international developments, the appointment of high civil servants, agricultural policy, cultural heritage and the Dutch royal family. The advertisements in Pandji Poestaka refer explicitly to a modern lifestyle.

Just as everywhere else in the world, smoking cigarettes (Illustration 1) was one of the regular attributes of a modern lifestyle of men (also see Illustrations 2, 4, 7 and 11). Wearing a tie was also a sign of distinction and modernity (see Illustrations 2, 5 and 6).

Illustration 1. Advertisement for Van Nelle tobacco (Pandji Poestaka 1–2, 1940)

The cigarette-smoking man in the next advertisement for Droste Cacao (Illustration 2) represents in several ways the new self-conscious cultural citizen of the colony. Drinking Droste Cacao (‘Don't bring the wrong brand.’ ‘Yes sir.’) in a public place was an expression of a modern urban lifestyle. The way the man is dressed (with a tie) and sits cross-legged, displaying his fancy shoes, in the company of an educated woman (wearing spectacles), is in sharp contrast to the bare-footed waiter whose body language represents tradition and submission. The customer's black peci (cap) does not denote nationalist convictions. Instead, he is a cultural citizen of the colony who has adopted in a relaxed manner the habits of his white overlords.

Illustration 2. Advertisement for Droste Cacao (Pandji Poestaka 85, 1932)

When women featured as the main characters in advertisements other criteria applied. Beauty and cleanliness were most important, and Colgate toothpaste promised a fresh breath, white and strong teeth and an attractive smile, if women would brush their teeth twice a day (Illustration 3).

Illustration 3. Advertisement for Colgate toothpaste (Pandji Poestaka 18, 1940)

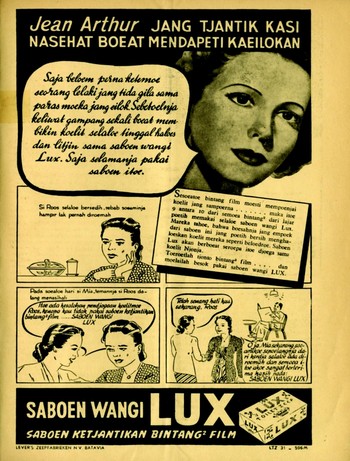

Cleanliness and hygiene were presented as crucial to a good marriage. Roos was greatly worried that her husband was not interested in her any longer and she took her friend Mia's advice – and that of film star Jean Arthur – to use perfumed Lux soap – just as nine out of ten movie stars do. Lux makes a woman's skin soft like velvet. To her relief, Roos found that her husband now came home straight after work, and, as we see in the background, was clearly content (Illustration 4).

Illustration 4. Advertisement for Lux perfumed soap (Pandji Poestaka 23, 1940)

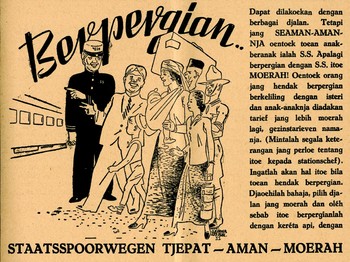

In many publications the train was used as an outstanding symbol of modern times. The impressive technology promised a new experience of movement and velocity. With the slogan: ‘Quick, safe and cheap’, families were invited to make trips at a special family rate (Illustration 5).

Illustration 5. Advertisement for national railways (Pandji Poestaka 17, 1940)

The new transport system was attended by a new time regime using timetables that required clocks and watches.Footnote 21 As the advertisement for watches of Merak (patented in London, made in Switzerland) says: The railways are a great enterprise for which knowing the right time is the most essential condition, reason why this station master from West Java should have a reliable watch. At the same time the advertisement suggests that people wanting to be up to date and keep pace with the times do not want to waste precious time and should purchase a watch that is modern, cheap and strong, and guaranteed to last a lifetime (Illustration 6).

Illustration 6. Advertisement for a watch (Pandji Poestaka 3, 1940)

As was already shown in Illustrations 3 and 4, nuclear families played a central part in a new, modern style of living. In the Philips advert (Illustration 7) we can see a happy family sitting together around the table in full harmony under the shining radiance of electric light.Footnote 22 Mother is sewing, father is smoking and reading the paper – his eye is probably caught by an advert for Philips bulbs – and their little daughter is reading too. The composition has a very Dutch ring and most likely an advert with a Dutch family served as a model for this illustration. Ironically, the girl in this drawing has fair hair, an unintended reference to the magic of modernity.

Illustration 7. Advertisement for Philips bulbs (Pandji Poestaka 10, 1940)

The caption beneath the illustration says in colloquial Malay that Philips bulbs produce more light, require less electricity, last longer, and consequently are cheaper. So the emphasis is on the affordability of the product, while at the same time the illustration is a good example of domesticated modernity. Here we see an image that the colonial authorities and the bulbs manufacturer promoted to the middle classes and that reflected bourgeois virtues.

The above is only a limited anthology from a few issues of the magazine Pandji Poestaka. More research is needed to see whether other magazines, a bit further away from the authorities' influence, display a different type of advertisement. A preliminary survey suggests, however, that most advertisements were rather evenly distributed among different magazines.Footnote 23

In contrast to the appearance of the global modern girl in the 1920s – who could be recognised by her bobbed hair, painted lips and an elongated body and who challenged the traditional order by disregarding her role as mother and wife – Barbara Hatley and Susan Blackburn conclude that in various women's magazines appearing in the 1930s in the Netherlands Indies much emphasis was put on the importance of cleanliness and hygiene and on the central role of women in the nuclear family.Footnote 24 The new nuclear family functioned as a vehicle of modernity, because it showed no links with the traditional world and the extended family with all its obligations.

It is interesting to look in this respect at magazines that were not radical in character but were read by relatively large segments of middle-class women.Footnote 25 The magazine Bale Warti Wanito Oetomo, which was affiliated with Boedi Oetomo, reflects in its articles and advertisements the efforts of Javanese upper-middle-class women to be loyal ‘soul mates’ of their husbands, responsible mothers of their children with an emphasis on the need to provide a balanced upbringing, and as active agents in the shaping of modern households.Footnote 26 The advertisement (in Javanese) for the modern telephone is a telling example of this ambition (Illustration 8). The mother phones the local pharmacy and asks to send someone to pick up a prescription. At the bottom of the advertisement the doctor comments: ‘Well, what a coincidence that you have a telephone. Without a telephone this would have taken much more time.’ At the right side an anonymous narrator says that the woman happens to have a telephone, the reason why she could call the doctor when her child fell ill, and then call the pharmacy (‘the medicine house’) to pick up the prescription. Taken together, this demonstrates how quick help for her child can be organised.

Illustration 8. Advertisement for the telephone (Bale Warti Wanito Oetomo, 2 Jan. 1937)

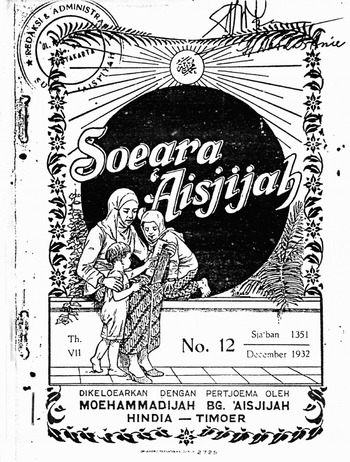

The magazine of the women's organisation of Muhammadiyah, Soeara ‘Aisjijah, demonstrates how modernist Muslim women gave shape to modernity by distancing themselves from the conservative influences of both adat (local customs) and the dangers of western decadence, personified by the image of the modern girl.Footnote 27 Like other magazines Soeara ‘Aisjijah emphasised the centrality of the household. Apart from a very ambivalent attitude towards polygamy, which was formally accepted but at the same time marginalised as much as possible, education for children and women was seen as an essential condition in order to participate in modern society.

Although we usually associate the wearing of jilbab with post-1979 Indonesia, the two advertisements from Soeara ‘Aisjijah indicate an early modelling of a ‘correct’ presentation of the female self. The advertisements in Soeara ‘Aisjijah form, therefore, an interesting contrast with the following Dutch-created images of women and schoolchildren, which are all shown in western dress. Illustrations 9 and 10 show clearly that modernist Muslims made serious efforts to determine their own trajectory towards a distinct modern lifestyle.

Illustration 9. Cover of Soeara ‘Aisjijah (7 Dec. 1932) emphasising the role of the educating mother

Illustration 10. Advertisement for a modern textile shop (Soeara ‘Aisjijah, 16 Aug. 1941)

Just like advertisements in which the iconic modern girl appeared, advertisements and articles in women's magazines formed in various ways a central tool for schooling consumers in the cultural practices of modernity.Footnote 28 Advertisements can, in this respect, be seen as a particular curriculum of an education of desire. Similar examples can be found in a series of school posters that were used at Hollandsch-Inlandsche Scholen (Dutch native schools) (HIS) and Hollandsch-Chineesche Scholen (Dutch Chinese schools) (HCS) to teach Dutch to indigenous and Chinese-Indonesian children (Illustrations 11, 12 and 13). According to Dutch novelist Hella Haasse, the posters made by advertisement artist Frits van Bemmel represented an idealised reality, the Indies of progress that the ethical politicians dreamed of, which served for the pupils as an image of the future to be striven for.Footnote 29 The posters are given a cheerful radiance by the light colours used, without directly showing the unequal power relationships of the colonial regime.

The posters show a rosy image of the indigenous middle classes and emphasise the nuclear family as a cornerstone of society and bearer of stability, cleanliness and order. Again, father is reading the newspaper (Illustration 11). And again, we see the family sitting together round the table, on the back veranda, with the backyard looking tidy and neat (Illustration 12). Servants in traditional dress, who are excluded from cultural citizenship, help to give these pictures a colonial flavour.

If we walk into the street we see the apotheosis of modernity in which various means of transport and communication are at the service of the indigenous middle classes (Illustration 13). More strongly even, Europeans are virtually absent. We see a stylised world exclusively inhabited by cultural citizens sustaining the continuity of the colony.

Illustration 11. Front yard (Hella Haasse, Bij de les: Schoolplaten van Nederlands-Indië [Amsterdam/Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Contact, 2004], pp. 78–9)

Illustration 12. Back veranda (Hella Haasse, Bij de les: Schoolplaten van Nederlands-Indië [Amsterdam/Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Contact, 2004], p. 76)

Illustration 13. Post office and station (Hella Haasse, Bij de les: Schoolplaten van Nederlands-Indië [Amsterdam/Antwerpen: Uitgeverij Contact, 2004], p. 83)

As Rudolf Mrazek rightly observed: ‘[T]he classroom, more than anything, made one wish to look to a window; even a picture on the classroom wall made one wish that the picture were a window, a break in the wall.’Footnote 30 If we try to imagine that these posters were such windows in the wall, we see in Illustration 13 how two Chinese schoolchildren looked at an imagined future as cultural citizens. It is the ultimate colonial order in which the Europeans are invisible, because the indigenous middle classes have internalised peace and order as qualities of their own (future) character. The fact is, though, that most people still walk barefooted, for the distinction from the absent Europeans should stay obvious.

A brief glance at school textbooks reveals that the images of the posters were to a large extent reproduced in the curriculum. In the second volume of Djalan ke Barat/Weg tot het Westen [The way to the West], for instance, we learn Dutch sentences about clothing, the household, traffic, the railway station, etc. Among the topics of various exercises is the story of the father who comes home from work in his office and changes his clothes. While mother serves tea, father lights a cigar. Then father changes clothes again, puts his hat on, takes his walking stick and goes to the shop.Footnote 31

In another textbook (Illustration 14) the European schoolmaster pays a visit to the parents of his pupils whose father reads the newspaper. In the next scene mother serves lemonade, while father, who looks like the father on the posters, presents a cigar.Footnote 32

Illustration 14. Schoolmaster pays a visit to the parents of his pupils (W. Stavast and G. Kok, Ons eigen boek [Groningen/Den Haag/Weltevreden: J. B. Wolters, 1930], p. 26)

The advertisements and school posters show us imposed ideas about modernity and cultural citizenship within a colonial context, but do not tell us anything about the way this was experienced by members of the indigenous middle classes. It is my hypothesis that this image wielded an enormous appeal on the members of the (lower) middle classes in the colony which helped them to formulate their own ideas about progress and modernity and lifestyle that expressed these notions.

An interesting problem is that, apart from advertisements and posters the (lower) middle classes left few visible traces. I doubt whether they wrote diaries, or possessed photograph albums with family pictures. Moreover, colonial photography was more interested in documenting official cultural heritage such as temples, dances and things labelled adat. A search for relevant images in the photograph collection of the Royal Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV) – which contains 100,000 photographs – had a disappointing result. There are a limited number of photographs taken in offices, where we see middle-class employees at work (Illustration 15). For the rest we get glimpses of people, literally in passing, either on a bicycle (the vehicle of the cultural citizen; Illustration 16), as bystanders, or as anonymous visitors to the yearly fair, Pasar Gambir, in the centre of Batavia.Footnote 33 Note the centrality of cigarettes in Illustration 17.

Illustration 15. Office of the archive of the Department of Interior, Batavia 1933 (Royal Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies [KITLV] collection: 36224)

Illustration 16. Man on a bicycle, at Oude Tamarindelaan, Batavia, 1941 (photograph by M. Ali, Dinas Tata Bangunan dan Pemugaran collection, Jakarta)

Illustration 17. Visitors to Pasar Gambir, Batavia, 1930 (Royal Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies [KITLV] collection: 16580)

Despite their marginal existence in colonial archives, the urban indigenous middle classes played a crucial role in sustaining the colonial regime. Already in 1960 Robert van Niel pointed to the fact that in the 1920s Dutch colonial policy aimed to make a deliberate distinction between the mass of the indigenous peoples and the westernised middle classes. The so-called ‘native communities’ had to be controlled through collective adat rule, whereas the rising and individualised middle class required a different approach. Access to the political domain was, of course, denied to them, and in judicial terms all indigenous peoples were excluded from European law. However, the middle classes were allowed to enter the western cultural sphere.Footnote 34 Through efforts to incorporate the middle classes in terms of culture, or lifestyles, into the colonial system, the cultural citizen was born.

Despite the invitation by advertisements and school posters to become cultural citizens of the colony, the trajectory towards this new socio-cultural destination was not a smooth one. Members of the middle classes aspiring to participate in progress and modernity faced racial boundaries and uncertainty and confusion about the making of the new nuclear family.

The rise of the indigenous middle classes was paralleled by a widening racial divide between cultural citizens and the European ruling class. Two telling anecdotes from both sides of the divide show the extent to which apartheid was on the rise during the late colonial period, while there was at the same time consensus about a shared point of concern.

The first comes from the letters of the Dutch ‘expat family’ Kuyck in Batavia. When they visit Pasar Gambir in September 1929 (see Illustration 17), they suddenly experience the proximity of the new cultural citizens. On 1 October 1929, Mrs Kuyck writes:

‘It is remarkable how differently the natives behave lately. They are not hostile, but many of them consider themselves completely equal to the Europeans. At Pasar Gambir I watched with Wouter (her son) a wooden submarine with a real periscope […] I happened to stand next to some natives and when it was our turn to look through the periscope, one of them said to my surprise in impeccable Dutch, ‘You must lift the boy, madam, he is too small to see anything.’ And another, who saw that I held a handkerchief in front of Wouters face – because I found it a sickening idea that so many people before us had looked through the periscope – said; ‘Yes, madam, the glass is probably dirty.’ They were not rude at all, but, mind you, in the past it would not have crossed the mind of a native to address a European woman. When we left we saw a couple of native women and men at the entrance. They looked so neat and civilized […] When we walked by I heard, again to my big surprise, that they spoke Dutch among themselves. ‘Do you go to Kramat? Can we give you a ride?’Footnote 35

The scene at Pasar Gambir shows that there were only a few places left where Europeans and the new cultural citizens could meet. Mrs Kuyk was amazed about the extent to which these ‘natives’ had appropriated the Dutch language but she took for granted that they apparently shared a similar concern about hygiene.

From the other side of the divide the following observation is made in a Dutch language article in Bale Warti Wanito Oetomo in 1938 signed by ‘Sk.’. The author starts by referring to an article written by ‘Helen’ in the journal Mataram. Because her djongos (houseboy) was not available, Helen had to go to the post office herself one day to send a money order. To her dismay she had to wait in a queue with natives behind and in front of her. She could not stand the smell of these people. Although she was willing to acknowledge that these natives were also human beings, she considered it an assault on European prestige to be so close to the dirty bodies of these people. Therefore she proposed to establish separate queues for natives and Europeans.

After reading this article Mrs ‘Sk.’ was infuriated. European women should realise that they also smell because of heavy perspiration and the consumption of cheese. And that the expensive silk dresses of these women smell as well because one cannot clean them regularly. Talking about civilisation, when friends of Mrs ‘Sk.’ visited the Netherlands they were harassed by lower-class street kids, which would have been unthinkable in the Indies. However, the readers should also learn from Helen's article, and admit that ‘we’ actually lack cleanliness and hygiene! It is therefore ‘our’ duty to care for the hygiene of one's body and in our households. The derogative term ‘dirty native’ should not just be interpreted as an insult, but as a challenge to demonstrate the opposite. In the last part of her article, which, as it happens, is placed next to an advertisement for Camay soap, ‘used by millions of women in Europe and America’, Mrs ‘Sk.’ expresses her gratitude for what the West has brought – hygiene, education, beautiful roads – but she reminds her readers not to imitate Western decadence.Footnote 36

There is, again, consensus about the importance of hygiene, which is accompanied by a growing self-consciousness about the way these cultural citizens gave shape to modernity without losing self-respect.

Modernity not only manifested itself in brightly coloured new lifestyles, but also caused doubt and confusion when it actually came to efforts to establish a nuclear family. These aspects have hardly been investigated and source material is scarce. Malay literature offers a few starting points. Well known is the novel Belenggu by Armijn Pané, in which the story of failed love relationships serves to contemplate modernity's failure to provide freedom.Footnote 37 The protagonists do free themselves of each other, but in the end they are irrevocably confronted with existential loneliness.

The isolated position of the individual in the modern world also plays a central role in cheap popular dime novels, which literati who were close to the prestigious colonial publishing house Balai Poestaka looked down upon. Henk Maier has shown that this genre of cheap novels offers insights in the way in which writers tried to cross the dividing lines between various ethnic groups in society.Footnote 38 These are often tragic love affairs in which lovers cannot reach each other or lose each other again. Against the background of cinemas, restaurants, tennis courts and taxis, love relationships between people of different ethnic backgrounds inevitably run aground. At the same time the protagonists criticise Dutch arrogance, as well as the emptiness of nationalism and the excesses of modern life. For modernity implied abandoning old patterns and a precarious search for new forms. It is therefore my hypothesis that these novels show that the new nuclear family was not a guaranteed success formula for a modern life, because finding a new lifestyle proved to be a complicated and risky adventure.

If we turn away from the teleological historiography of the nationalist success story, we get a much better view of the cultural dynamics of late colonial society and the way in which the indigenous middle classes were interwoven with the colonial system. We may also see that nationalism was an aspect of a much broader movement that aspired to achieve modernity, which was instrumental in order to become cultural citizens of the colony.Footnote 39 Efforts to achieve modernity in term of new lifestyles did not occur exclusively in the Netherlands Indies. In Burma the appearance of modern women who looked very much like the new modern girl had several effects. It underlined a new autonomy for women by questioning existing gender identities, and it embodied efforts to modernise without purely imitating the West. However, nationalists depicted modern Burmese women as a threat to their cause because they acted as agents of capitalist consumerism.Footnote 40 It would be interesting to investigate in more detail who actually represented the modern girl in the Netherlands Indies, and what role Indo-European citizens played in this context.Footnote 41 Another question concerns the extent to which gender identities among the cultural citizens of the Netherlands Indies have actually shifted.

Things went in a different direction in Thailand. At the end of the 1930s, the military leader Phibum Songkhram forced a ‘westernising behavioural revolution’ upon the Thai citizens by ordering them to wear Western clothing, to sit on chairs, to use forks and spoons, to join clubs, and to applaud at shows; men had to kiss their wives before going off to work, women were obliged to appear in public with hats and gloves, citizens should visit exhibitions to learn about modern art, and the legal system emphasised the importance of modern monogamous marriages.Footnote 42

Whereas the Thai example illustrates the state's interest in fashioning modernity, research by the Indonesian historian Agus Suwignyo shows how members of the indigenous middle classes in the Netherlands Indies were the main actors whose ambition it was to become cultural citizens of the colony. They did not primarily focus on the nationalist case, but preferred instead a promising career within the colonial state. Many alumni of the Hollandsch-Inlandsche Kweekschool dreamed of upward mobility within the colonial system. They were taken by surprise by the sudden independence of Indonesia, which many people experienced as a breaking of the dam, causing turmoil and offering new opportunities for upward mobility.Footnote 43

After the revolution the cultural citizens became full citizens. In 1950 the indigenous middle classes had become all of a sudden part of the new upper middle class of the Indonesian nation. On an advertisement for Palmboom margarine from 1953, we encounter some of them in a cocktail party, where men in suits enjoy drinks and sandwiches and listen to the radio, while the women, in traditional dress, discuss the superior quality of Palmboom margarine (Illustration 18).

Illustration 18. Advertisement for Palmboom margarine (Ipphos Report, Djakarta: Ipphos Coy. Ltd, vol. 5, 13, 1953)

The advertisement for Palmboom margarine resembles a series of snapshots, as if we witness the cocktail party through the lens of a camera. At this point interesting parallels can indeed be drawn with the rise of photography in Indonesia. In her recent book on popular photography in Indonesia, Karen Strassler elaborates how individual Indonesians placed themselves though photography in a narrative of national modernity, and how they came to see themselves as Indonesians.Footnote 44 It would be interesting to pay more attention to the way advertisements and photography interacted, for both advertisements and popular photography created images that circulated widely and provided imaginative resources on the basis of which people could shape their identities.