Introduction

Laos and Cambodia are frequently considered to share a common destiny as comparatively sparsely populated buffer states squeezed between two much more powerful neighbours: Vietnam and Thailand. The two countries are also commonly seen in the context of regional mainland Southeast Asian political struggles, rather than in relation to their own political aspirations and struggles with neighbours.Footnote 1

Irredentism is the doctrine that people or territory should be controlled by a country that is ethnically or historically related to it. Indeed, irredentism is frequently complex, and generally can only be explained through examining relationships with others geographically and over history. There has been much written about irredentism in Laos and Cambodia. For the Lao, scholars commonly focus on irredentism in relation to its complex relationship between Laos and northeastern Thailand (Isan),Footnote 2 while for Cambodia irredentism is often emphasised with regard to Cambodia's relationships with Thailand and Vietnam, especially Kampuchea Krom in the Mekong Delta.Footnote 3 However, there has been much less written about irredentism as it relates specifically to Laos and Cambodia, the topic of this article.

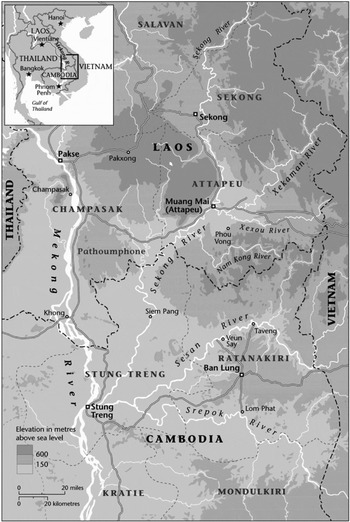

Here, I consider the factors particularly relevant for understanding the present circumstances along and across the Laos–Cambodia border (see Figure 1), trying to pay equal attention to the sensitivities on both sides of the border, without privileging one view over another. I examine how the Lao and Khmer have tended to mould historical events to fit with their nation-building discourses, both recognising the power of states and international boundaries to affect identities, and the importance of human agency in affecting the production of identities that are – in at least some ways – able to transcend international boundaries.

Figure 1. The Laos–Cambodia border region, 2010.

The Khmer in southern Laos

The Khmer clearly have a long history in what is now southern Laos and northeastern Cambodia.Footnote 4 The pre-Angkorian Khmer of the Chenla era inhabited the present-day border region between Laos and Cambodia during about the fifth to eighth centuries. It was during this period that the important temple of Vat Phou was built west of the Mekong River near Champasak Town, and there are a number of other stone ruins in Attapeu Province, as well as the Mun Valley in northeastern Thailand, that indicate the influence of Chenla. Between the ninth and fourteenth centuries, during the Angkor period, or golden age of Cambodian kings, Khmer domination of lowland parts of present-day Laos and Thailand increased.Footnote 5

The rise of the Lao

After the fourteenth century, Angkor began to suffer serious declines, mainly due to Siamese military victories against the Khmer,Footnote 6 and in 1353, King Fa Ngum's Kingdom of Lan Xang apparently extended southwards along the Mekong as far as the present border between Laos and Cambodia, although Khmer people still dominated the lowlands of what is now southern Laos.Footnote 7 The Khmer gradually moved south out of present-day Laos and northeastern Cambodia, or became assimilated as Lao. Much of today's ‘Lao’ population in southern Laos and northeastern Cambodia are also assimilated highlanders.Footnote 8 The Lao took advantage of the decline in Khmer power and pushed south.Footnote 9

The sixteenth century marked the expansion of Lao influence into the region. The King of Laos, Xetthathirat II, battled against Cambodia. However, there are some differences in the way the Lao and Khmer depict these events. The Khmer historian, Treung Ngia, bluntly commented, ‘For this period we have to rely on the Khmer chronicles because the Lao documents, whether written in Lao or French, provide no information at all.’Footnote 10 Treung writes about the Lao king challenging the Cambodian king to an elephant duel. The Khmer king accepted the challenge, but the Lao elephant was 4 metres high, compared to 3.5 metres for the Khmer pachyderm. Still, the Khmer elephant prevailed.Footnote 11

It was not until the first half of the seventeenth century that Lao immigration gained particular momentum,Footnote 12 even though there were apparently some setbacks.Footnote 13 Lao immigration to the south was particularly pursued by a well-known Buddhist from Vientiane known as Phra Phonsamek, or simply Phra Khou Khi Home (the monk whose excrement smells good). After falling out of favour with the king in Vientiane at the beginning of the eighteenth century, Phonsamek established the first Chao Muang, or principality chief, of what would later become known as Stung Treng (Sieng Teng in Lao). Later, upon arriving in Champasak to the north, he received a request from Nang Phao, the sovereign of the region, to take her place on the throne. However, his non-confrontational nature as a monk made it impossible for him to become a good administrator. Therefore, in 1713 he appointed Chao Soisysamout, or Chao Nokasat, who was also from Vientiane, as the first king of Champasak, thus beginning the golden age of Champasak.Footnote 14

However, during the reign of Chao Sayakouman, Chao Soisysamout's son, Champasak's independence was lost. In 1778, Siamese troops took control Champasak, forcing the kingdom to become Siam's vassal, and thus marking the beginning of the gradual decline of Champasak.Footnote 15

The arrival of the French

In the second half of the nineteenth century a number of French explorers, soldiers and officials visited what is today southern Laos and northeastern Cambodia, including Ernest Doudart de Lagrée and Francis Garnier in 1866, François-Jules Harmand in 1877, Étienne Aymonier in 1882–83, and various members of the famous Pavie Mission in the early 1890s.Footnote 16

In 1863 Cambodia became a protectorate of France, and in 1883 Annam too became one.Footnote 17 However, only after 1885 did the political climate in France make it possible to continue aggressive territorial expansion into Laos.Footnote 18

The Siamese royal court was concerned as France pressured them from the east and the south,Footnote 19 and in around 1885, the King of Champasak, Chao Nyoutithammathone, under the direction of Bangkok, ordered his relative, Chao Thammatheva (Ya Chao Tham)Footnote 20 to travel to the eastern hinterlands of the Sesan River Basin, in present-day Stung Treng and Ratanakiri Provinces,Footnote 21 to establish Siam's sovereignty in the area.Footnote 22

Ya Chao Tham is believed by both ethnic Lao and highlanders from the region to have dazzled the previously hostile inhabitants with his magical powers, many succumbing to his influence and beginning a period of ethnic Lao dominance.Footnote 23 The security that he provided opened up the Veun Say area to ethnic Lao immigration from present-day Champasak Province, Laos. His granddaughter's husband, Chao Thongbay, would later attempt to return Stung Treng to Laos.

In early April 1893 the French surprised the Siamese representative in Stung Treng and forcibly occupied the town.Footnote 24 Two months later, Monsieur Bastard, the commander of the French force, wrote to his superiors from Stung Treng. He strongly recommended against bringing Khmer people to administer Stung Treng, as Lao was the dominant language.Footnote 25

Tensions between the Siamese and the French continued to increase, climaxing with the well-known Pak Nam incident in July 1893, when two French warships blockaded the mouth of the Chao Phraya River near Bangkok, thus forcing the Siamese to sign over territories east of the Mekong River to the French on 3 October 1893.Footnote 26

The French reorganisation of the border region

Attapeu, Stung Treng and Siem Pang were initially established as a French colony administrated by Cochinchina.Footnote 27 However, as these new French possessions could only be reached by passing through either Annam or Cambodia, on 1 June 1895 the region was transferred to what was Lower Laos, with its capital based on Khong Island. Then, on 19 April 1899, Lower and Upper Laos were integrated into a single Laos with Vientiane as its capital.Footnote 28

On 9 August 1904, Monsieur Lamotte, who was assigned to investigate plans to redraw the border between Laos and Cambodia, wrote, in a telegram to his superiors, that Cambodia had requested that the Srepok River be made the northern limit of Cambodia. Lamotte suggested that Dak Lak, in the present-day Central Highlands of Vietnam, be given to Annam, and that Melouprey and Tonle Repou – the historical frontier with Champasak – be ceded to Cambodia. He reported that French officials in Laos agreed with this plan, but felt that the historical borders of Champasak should be maintained, following Khone Island and Tonle Repou. The French officials in Laos also wanted to keep Siem Pang in Laos, since there were just a few Cambodian settlements there.Footnote 29

In November 1904 Dak Lak was detached from Laos,Footnote 30 and in December 1904, Paul Beau, the Governor-General of Indochina, transferred Stung Treng from Laos to Cambodia, including Siem Pang.Footnote 31 Paul Beau wrote, ‘They [the Cambodians] have past national feelings and desires to regain past power.’Footnote 32 On 4 July 1905, Kontum and Ban Don were ceded from Laos to Annam, at least partially because the Lao officials in these areas had supported several revolts.Footnote 33

The French wanted to reduce the influence of Champasak, which was on the west bank of the Mekong and was, until February 1904, under Siamese control but which maintained strong cultural and trade ties with Stung Treng, Siem Pang and Veun Say.Footnote 34 Practicalities regarding the administration of the remote region also contributed to these decisions. One important justification was to satisfy the Cambodian royal court, which argued that the region should be returned to Cambodia. They also wanted Champasak and Attapeu to be transferred to them, but were only able to convince the French to give them Stung Treng.Footnote 35

The Cambodian claims were surprising, as there were very few ethnic Khmer people living in the region. For example, by the time the French occupation began only 10 Khmer were reported to be living in Attapeu (Martin Rathie, personal communication, 2006), and in Veun Say, which became Moulapoumok Province, Cambodia,Footnote 36 the Khmer population was only nine in 1912.Footnote 37 Highlanders made up most of the population of Moulapoumok, followed by a significant Lao population located along the Sesan River. Stung Treng and Siem Pang had somewhat larger ethnic Khmer populations (400 or 1 per cent, and 600 or 8.8 per cent respectivelyFootnote 38), due to the presence of some ethnic Khmer Khe villages there, but this was offset by a large ethnic Lao population.

It appears that Paul Beau's order to transfer Stung Treng to Cambodia was made illegally, without the permission of the Ministry of Colonies in France. However, this was not discovered until a colonial inspection was conducted in 1915, and by then it seemed impractical to reverse the decision.Footnote 39

Throughout much of the rest of the French colonial period, France relied heavily on the ethnic Lao inhabitants of Stung Treng to administer the region. In particular, Ya Chao Tham, the Champasak native, and grandson of the former king of Champasak, was particularly influential, and became the first Governor of Stung Treng in 1906.Footnote 40

During the French colonial period some efforts were made to demarcate the border between Laos and Cambodia, but the frontier was probably never fully demarcated, as both sides of the border were under French control, making precisely defining the border less of a priority than confirming Indochina's borders with Thailand.Footnote 41 Furthermore, much of the border was located in very remote regions, making its demarcation difficult and expensive, and its practical value for both sides limited. Also, considering the very limited human and financial resources that the French had in the border area, there were higher priorities.

Independence for Laos and Cambodia

While interviews with ethnic Lao living south of the border with Laos indicate that many in this group continued to regret the decision of the government of Cambodia to sever Stung Treng from Laos throughout the French colonial period,Footnote 42 this resentment was mediated by the influence that the ethnic Lao continued to have there, via Ya Chao Tham and his relatives.

In around 1930, Ya Chao Tham's grandson-in-law, Chao Thongbay – a royal from Champasak with strong trade relations with the ethnic Brao highlanders living along the border – and a small group of ethnic Lao people from Veun Say incited the highlanders of the lower Sesan River Basin to rebel against the French Cambodian authorities, in order to try to create the type of insecurity that would make it possible for Veun Say and Stung Treng to be reattached to Champasak. However, his plan was discovered before the revolt became serious, and Thongbay was arrested. He was eventually freed, but the French never allowed him to return to Cambodia from Champasak.Footnote 43

However, according to Chao Thongbay's grandson, Chao Singto Na Champassak, in 1945, when Champasak was temporarily part of Thailand, Chao Boun Oum Na Champassak asked Thongbay to return to Veun Say to again incite rebellion amongst the highlanders, so that Veun Say could be brought back under the control of Champasak. At around the same time leaders from northeastern Thailand reportedly came to Champasak to talk to Chao Boun Oum about joining with Champasak to create a new state. However, the Thai authorities crushed the secessionist movement in northeastern Thailand, and Thongbay was also unable to do as Chao Boun Oum asked, as he became sick soon afterwards and died during the same year.Footnote 44 ‘The old people used to say that this land was Lao’, reminisced Ya Chao Tham's great granddaughter in 2008 when I met her in Veun Say.Footnote 45

In the 1930s and 1940s, nationalist sentiments increased throughout the region – including in Laos and Cambodia – partially as a result of efforts by the French. For example, the Buddhist Institute in Phnom Penh was an important breeding ground for Cambodian nationalists, such as Son Ngoc Thanh, the future Prime Minister under the Japanese and leader of the Khmer Serei, and Tou Samouth, the future Secretary-General of the communist Khmer People's Revolutionary Party (KPRP).Footnote 46

In Cambodia the French only encouraged nationalist pride in the anachronistic context of the rediscovery of Angkorian civilisation, for which the French proclaimed responsibility, as they did not want to fuel Khmer hatred of the Vietnamese, which worked against their interests.

The French treated the Lao differently, as the Lao did not display as much of an aggressive dislike of the Vietnamese, although the small Lao elite were certainly critical of the French for opening up Vietnamese immigration into Laos in the 1930s.Footnote 47 However, the French recognised that promoting Lao irredentism in relation to claims over northeastern Thailand played to their advantage,Footnote 48 as they wanted to counter the Pan-Thai movement that was developing in Bangkok.Footnote 49

Nationalism, however, was particularly spurred as a result of the World War II, at which time the Japanese occupied French Indochina from mid-1940, and took full control of the country for a five-month period in March 1945. The Japanese showed people in Indochina that the French were not invincible.Footnote 50 In addition, Phibun Songkham's and Luang Wichit Wattakan's irredentist Pan-Thai movement was also extremely important in influencing Lao views regarding French power. French colonial hegemony was especially shown to be vulnerable between 1941 and 1946 when the Thais annexed Champasak and Sayaboury.Footnote 51 Still, the French were able to regain control over Indochina, despite opposition from nationalists and communists in Laos, Cambodia and especially in Vietnam.

France became embroiled in an increasingly bloody and costly conflict with Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh, and after the decisive loss at Dien Bien Phu in northern Vietnam, France was forced to give up full control of Indochina in 1954.Footnote 52

The border between independent Cambodia and Laos

In 1953, Sihanouk's Sangkum Reastr Niyum (People's Socialist Community) formed the Royal Cambodia Government (RCG), which was able to gain a firm control of Cambodia after the Geneva Accords of 1954 necessitated the withdrawal of the French. The Accords also ended armed conflict and then led to the withdrawal of the Viet Minh from Cambodia. Many of the Cambodian communists also relocated to Hanoi in 1954. Similarly, except for the provinces of Phongsaly and Sam Neua in northern Laos, which was allocated to the Pathet Lao communists as part of the 1954 Geneva Accords, Laos came under the control of the Royal Lao Government (RLG). Right-wing politicians, especially Chao Boun Oum, gained increasing control over southern Laos.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the political situations on both sides of the border resulted in increased tensions. On the Cambodian side, beginning in the late 1950s, the Sangkum government began an aggressive nation-building campaign in northeastern Cambodia, targeting the ethnic Lao and highlander populations. At the very beginning of the 1960s, Brao Kavet and Brao Umba living in the mountains along the border with Laos were largely resettled to the lowlands, where large villages were set up along the Sekong and Sesan Rivers.Footnote 53 Education was an important part of the government's strategy to Khmerise the border region, and ethnic Khmer teachers from the south were recruited to teach in strictly Khmer language schools set up for highlanders. The Sihanouk government also assigned Khmer teachers to Khmerise the Lao population in Stung Treng and Ratanakiri Provinces, the latter being created in 1959 and put under military administration.Footnote 54

A number of ethnic Lao former students recalled to me how, in the 1960s, speaking even a word of Lao in school was a punishable offence, whereas both Lao and Khmer were taught to ethnic Lao students during the latter years of the French colonial period. One former student told me that he had to stand in a sunny corner of the school for hours when he made the mistake of uttering a Lao word.Footnote 55 Another former student remembered that students were fined if they spoke Lao in school. In some places a special book existed. The first student each day who spoke Lao would be given the book, and if someone else did so later in the day, the book would be passed to that student, and so on. By the end of the day, whoever was holding the book would be fined.Footnote 56

For adults, punishment was imposed for speaking Lao in public places. In the late 1960s many ethnic Lao people from Stung Treng Town remember that anyone caught speaking Lao at the market would be fined 25 riel. They were, however, still permitted to speak Lao in houses or other private spaces. One ethnic Lao man from Siem Pang recalled being fined a couple of times after he had arrived in Stung Treng Town from his village.Footnote 57 However, it was hard to impose this rule in some places, such as Veun Say and Siem Pang.Footnote 58 One Lao recollected hearing about the anti-Lao language regulation, but said that many people in Veun Say could only speak Lao, making it unenforceable there.Footnote 59

Another part of the Sangkum's Khmerisation programme involved encouraging 600 Khmer families from central Cambodian provinces to move to the northeast. As part of the scheme, each family received 2 pairs of buffaloes, 1 pair of cows, 1 wagon, 1 ox-cart, land, wood to construct a house, and rice supplies for 3 years.Footnote 60 Three hundred Khmer families were also moved to Siem Pang District along the Sekong River in 1957, of which only about 100 ended up staying. In some cases, soldiers were encouraged to move to the border region with Laos to establish Khmer claims there. For example, in 1962, over 100 Khmer military families – mainly from Prey Veng Province in the south – established O Svay Village, Thalaboriwat District, Stung Treng Province, directly adjacent to the Laos' Khong District, Champasak Province. A monument to Sihanouk was built in the village. Some Khmer from the south were relocated to Km 8 Village near Stung Treng Town, and in the 1960s, Khmer soldiers were encouraged to immigrate to Ratanakiri Province.Footnote 61

These Khmerisation efforts were – not surprisingly – upsetting to the ethnic Lao population of northeastern Cambodia,Footnote 62 and the treatment of Lao people in Stung Treng also disturbed the Lao population in southern Laos. One ethnic Lao man originally from present-day Pathoumphone District, Champasak Province, but now living in Canada, told me that his grandfather and other old people used to tell younger people in the 1960s to be careful if they went to Stung Treng, as speaking Lao there was illegal. The Lao people in southern Laos were apparently quietly angry with what they understood to be the mistreatment of Lao people in Cambodia. They tended to blame Norodom Sihanouk for the perceived excesses of the Cambodian government, but these bad feelings were partially counter-balanced because Sihanouk was rumoured to have a Lao minor wife from Luang Phrabang, in northern Laos. In any case, the perceived poor treatment of Lao people in Stung Treng was well known amongst military and political leaders from southern Laos, and negatively affected relations between Sihanouk and right-wing leaders in Laos.Footnote 63

There were other issues. In early 1955, the Americans began to be dissatisfied with Sihanouk's neutralist policies and unwillingness to actively fight against communism. Therefore, together with Thailand, the US government began supporting Son Ngoc Thanh's Khmer Serei (Free Khmer) anti-Sihanouk forces, which at the time had their main base inside Thailand.Footnote 64

Sihanouk discovered, exposed and denounced a right-wing conspiracy against him in early 1959. The plan apparently involved setting up a secessionist state that would then link up with southern Lao provinces controlled by Chao Boun Oum to form a new free state, which would be immediately recognised by the US. This would permit the Americans to cut off the Indochina corridor through the control of territory stretching between Thailand and South Vietnam.Footnote 65 It is unclear how much truth there was to this conspiracy theory, but Sihanouk certainly believed it was true, and therefore it contributed to irredentist feelings.

In the 1960s the brilliant jurist and nationalist Khmer student Sarin Chhak wrote a political science doctoral dissertation in Paris, focusing on the borders between Cambodia and Laos and South Vietnam. His thesis was later published as a book.Footnote 66 Chhak argued not only that Stung Treng should be part of Cambodia, but also parts of present-day Laos, such as Attapeu, and from Vat Phou in Champasak south, since ruins there indicated that Khmers once inhabited areas north of the present Laos–Cambodia border. He emphasised that the territories that were previously occupied by Khmers, including the Pakse region (in present-day Laos), and areas lost to Vietnam, including Dak Lak Province, and areas of the Song Be, Tay Ninh, Go Dau Ha and Ha Tien further south should belong to Cambodia. Later he became Cambodia's Ambassador in Egypt, and in 1970 he became Foreign Minister for the Royal Government for the National Unification of Kampuchea (GRUNK), the pro-Sihanouk government in-exile established by a broad coalition of leftists and neutralists, based in Beijing, China.Footnote 67 He remained Foreign Minister for a short period even after Cambodia came under the full control of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, but without any real power. Chhak's thesis would later provide the Khmer Rouge with the ammunition that they needed to make claims regarding the borders with Vietnam and Laos.Footnote 68

In early March 1964, Sihanouk pressured the Lao neutralist Prime Minister, Souvanna Phouma, to recognise the Laos–Cambodia border, but Souvanna refused, since Laos wanted to maintain its historical claim over Stung Treng and the eastern highlands, including Ratanakiri. He claimed that the frontier had never been fully demarcated. The issue was made even more sensitive when residents of Stung Treng wrote letters to King Savang Vattana in Laos, complaining about how poorly they were being treated by the Sangkum government. Some of these letters may have been written by Khmer Rouge and Pathet Lao propaganda agents, or by Champasak loyalists, in order to damage relations between the two countries.Footnote 69 In any case, Souvanna's refusal upset Sihanouk, and he openly criticised Souvanna in a radio broadcast soon after he left Phnom Penh on 7 March.Footnote 70

Tensions continued over the next few years, as at the beginning of 1966 the Khmer Serei reportedly had one of its main bases in Stung Treng near the Lao border,Footnote 71 where it probably was being supported by right-wing elements in Laos.Footnote 72 However, in October 1967, during the Second Non-Aligned Movement conference held at Cairo, the neutralist Lao Foreign Minister Pheng Phongsavanh gave his Cambodian counterpart Prince Kanthol assurances that Laos had no territorial claims over Cambodia. This note, however, was repudiated on Pheng's return to Vientiane by right-wing colleagues in the RLG cabinet. Phoumy Nosavan, a southern Lao strongman, was amongst the most vocal critics.Footnote 73 When Sihanouk heard of this reversal, he sternly berated the Lao, claiming that they had become like the Thai, since diplomatic agreements with the RLG could apparently not be relied upon.Footnote 74

The December 1967 issue of Kambuja, a semi-state run magazine and mouthpiece of Sihanouk, included a feature entitled ‘Laos expansionist’, which complained about the ambiguity of the RLG's attitude in regard to the border with Cambodia. The article also discussed attempts by the Western media to generate hostility between the two nations, by frequently referring to the Laos–Cambodia frontier dispute.

Sihanouk was upset with the RLG's failure to deny that a dispute over the Lao recognition of the border with Cambodia existed. From Cambodian Embassy staff in Vientiane, Sihanouk learned that members of the powerful Abhay family from Khong Island sought to have the frontier readjusted in favour of Laos.Footnote 75 The article sought to make the Lao feel ashamed. The most alarming accusation was that Khmer Serei forces were receiving assistance from Kouprasit Abhay's right-wing forces in Laos. Sihanouk claimed that the Khmer Serei were being armed and trained in Tha Khek and Savannakhet, in south-central Laos, before infiltrating into Cambodia via Stung Treng Province. Sihanouk also accused Lao communists of providing the Khmer Rouge with supplies via the Sekong River.Footnote 76

On 23 March 1969, Souvanna Phouma took tentative steps to give Cambodia assurances regarding its territorial integrity, but he refused to provide a written guarantee. On the other hand, Souphanouvong and the communist Neo Lao Hak Xat took a position favourable to Sihanouk.Footnote 77 It appeared to Sihanouk that ‘estrangement’ between Phnom Penh and Vientiane was likely to continue, despite the ‘long history of amicable relations between the two countries’. Sihanouk had said in April that he was going to close down the Lao Embassy, but in a speech he made on 15 October, he reviewed relations with Cambodia and Laos and referred in complimentary terms to the new Lao representative in Phnom Penh.Footnote 78 It is unclear why his position shifted rapidly, but he may have felt that he had larger problems to deal with, and that keeping the lines of communication open with the RLG was advisable.

In the April 1969 edition of Kambuja an editorial appeared that was again critical of Lao claims over Stung Treng and Ratanakiri. The article pressured the RLG to recognise the borders and integrity of Cambodia.Footnote 79 Its main purpose was apparently to demonstrate lingering expansionist ambitions amongst the right-wing Lao elite.

Although Lon Nol and Sirik Matak orchestrated a successful coup d'état against Norodom Sihanouk in March 1970,Footnote 80 the Lon Nol regime had little involvement with border affairs between Cambodia and Laos, as just a month after the coup the northeast was abandoned by the Forces Armées Nationales Khmeres (FANK),Footnote 81 at the recommendation of the US government.Footnote 82

The Khmer Rouge

In the 1960s, the Khmer Rouge were themselves concerned by Lao irredentism and possible links to the Khmer Serei. Lingering irredentist tensions between rightist forces in Laos and Cambodia negatively affected Pathet Lao–Khmer Rouge relations. However, the Khmer Rouge's hatred was directed mainly at the Vietnamese, with the Lao being considered less problematic. This was the case in April 1975 when Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer RougeFootnote 83 and in December 1975 when the Pathet Lao gained full control of Laos.Footnote 84

Although Ben Kiernan argues that the Khmer Rouge had a racist element, especially towards the Vietnamese and, to a less extent, the Cham,Footnote 85 the Khmer Rouge considered many of the ethnic Lao people living in rural areas of northeastern Cambodia to be base people.Footnote 86 However, they prohibited the use of the Lao language in the 1970s, and Lao women were forced to wear black dresses like Khmer women. The Khmer Rouge also banned the growing of sticky rice, regarded as an essential element of Lao-ness.Footnote 87

Although overtures were made by the Lao government to the Cambodia government in 1975, with the Lao Foreign Minister, Phoune Sipraseuth, visiting Phnom Penh to discuss Laos' possible use of the Cambodian port of Kompong Som,Footnote 88 Khmer Rouge suspicions of the Pathet Lao grew, and the Khmer Rouge's Four Year Plan, issued in April 1976, discouraged Lao–Cambodian relations. Then, in July 1977, the situation further deteriorated after the prime ministers of Laos and Vietnam signed a 25-Year Treaty of Mutual Friendship and Cooperation. The Khmer Rouge leadership believed that the treaty would result in a sudden increase in Vietnamese migration into Laos. It also caused them to see the Pathet Lao as nothing more than the puppets of the North Vietnamese, what the Khmer Rouge might have become had they not exerted their independence from the Vietnamese Workers' Party. The Khmer Rouge's strategic assessment of Laos changed from being a relatively harmless bystander to becoming an active accomplice in the irredentist and revisionist machinations of the Vietnamese communists.Footnote 89

The irredentist historiography of the Khmer Rouge, inspired by the work of Sarin Chhak,Footnote 90 claimed that all territories in Laos and Thailand with Khmer language inscriptions were rightfully Cambodian. Potentially this was an area that stretched from Prachinburi in eastern Thailand and north to the Vientiane Plain.Footnote 91

Laos–Cambodia relations deteriorated considerably along the border, with Lao civilians, including fishermen in the Khone Falls area, being fired upon and killed indiscriminately by Khmer Rouge soldiers. Villagers in Attapeu report being shot at periodically by the Khmer Rouge, with some dying. The policy of Laos was to not shoot back, even if people were killed, as the Government of Laos (GoL) was having enough trouble fighting right-wing rebels without having to devote military resources to fighting the Khmer Rouge as well.Footnote 92

The decline of the Khmer Rouge

In late 1978, following years of Khmer Rouge violent attacks on villages in Vietnam, the Vietnamese army invaded Cambodia from Vietnam and Laos, quickly routing the Khmer Rouge and taking over Phnom Penh by early January 1979, forcing the leadership of the Khmer Rouge to flee to the Thai border to regroup.Footnote 93 During the 1980s Laos and Cambodia border problems declined, as both sides were strongly aligned with Vietnam. Border issues dwarfed the problems the Cambodia government and their Vietnamese allies had fighting the Khmer Rouge and other anti-Vietnamese rebels. For years the Khmer Rouge controlled much of the border region with Thailand and Laos, making the location of the border a moot point.Footnote 94

Since the end of the civil war

In 1998 the Khmer Rouge imploded, ending 30 years of extreme violence and civil war in Cambodia. Sihanouk and many other Cambodians claimed the loss of considerable Cambodian territory to the country's neighbours, particularly after the Vietnamese invasion in 1979. The border issue with Laos only heated up after the Khmer Rouge were no longer destabilising the border region. The issue also became increasingly important to Cambodian students and the media. This attention culminated in a series of student protests in Phnom Penh over alleged intrusions into their country by Vietnam, Thailand and Laos.Footnote 95 Even though most of those students had never actually visited Cambodia's border regions, it was the irredentist geographical imaginary of the nation that was important. The government led by Prime Minister Hun Sen did not condone these protests, and had always ruled out making any territorial demands against either Vietnam or Laos.Footnote 96

In July 1999, in response to increased border tensions, the Laotian Ambassador to Cambodia, Ly Southavilay, told Cambodian government representatives that his country had ‘no intention to violate Cambodian territory’. The Lao envoy called for joint efforts between the two countries to resolve their longstanding border dispute.Footnote 97

Following this overture, on 25 April 2000, Voice of America radio reported that the Prime Ministers of Laos and Cambodia, Sisavath Keobounphan and Hun Sen respectively, had pledged to define the border by the end of 2001. Both countries were eager to resolve the outstanding border dispute, especially since both had joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).Footnote 98 Then, on 1 June 2000, it was reported that both countries would jointly begin the demarcation process on 9 June, representing the first attempt in over 20 years to map the border.Footnote 99

However, initial hopes for a quick resolution were soon dashed, and by 2 January 2003, when the Sixth Meeting of Laos–Cambodia Joint Commission took place in Phnom Penh, the border question remained unresolved. In a joint statement, the Foreign Ministers, Hor Hamhong (Cambodia) and Somsavath Lengsavath (Laos) diplomatically expressed their appreciation to the operational groups and border survey teams for the survey and demarcation completed over 307 km, including the implantation of 46 temporary border pillars. They urged their Joint Border Commission to resolve the pending border issues and continue its operational survey so as to complete the permanent border demarcation as soon as possible.Footnote 100

On 27 February 2003, the King of Cambodia, Norodom Sihanouk, released a declaration about Cambodia's borders with Vietnam, Thailand and Laos. He complained that Co-Minister of Defence Prince Sisowath had said earlier that ‘the country's borders with Thailand, Vietnam and Laos remain unclear and delicate’. The king insisted that Cambodia's borders are clear and that nobody should say otherwise. Sihanouk also recommended that US military maps be consulted, since he believes that they clearly show Cambodia's border with its neighbours.Footnote 101

Indicative of the conflict between Laos and Cambodia, Sean Péngsè, the President of the Cambodian Border Committee, a private organisation based in France and run by former Cambodian refugees, wrote a letter to Norodom Ranariddh, President of the FUNCINPEC Party, on 1 April 2004 to express his concerns about Cambodia's borders, especially with Vietnam. However, he commented about the Laos–Cambodia border, that, ‘Laos rejects the delimitation of its borders with our country that was established by the former French colonial authority.’Footnote 102

On 19 January 2005, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Cambodia, Hor Namhong, met with the Lao Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs and head of the Laos–Cambodia border committee in Phnom Penh, at which time Hor Namhong expressed his appreciation that 86 per cent of the border issues between the two countries had already been worked out. He said that he hoped that the remaining points could be resolved soon.Footnote 103

On 31 March 2005, Prime Ministers Hun Sen and Bouasone Bouphavanh met in Vientiane and jointly expressed their appreciation of the progress made on border demarcation between the two countries. The Vientiane Times reported that so far 121 border markers, 86 per cent of the total, had been installed along the border.Footnote 104

However, on the same day, the retired King Sihanouk sent open letters to the governments of Vietnam, Thailand and Laos, writing,

The Cambodian people, all Khmer men and women both inside and outside of Cambodia who are not traitors to their homeland, request that you notably come to respect international law, the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements on Cambodia, and the U.N Charter, by accepting, with a fair play which will avoid you dishonor, to surrender to the current Cambodia the villages, lands, seas, and islands that you had stolen and took away from us.Footnote 105

Clearly, the position of Sihanouk was at odds with that of the Cambodian People's Party (CPP) and the Government of Cambodia (GoC).

At the end of April 2005, the Supreme National Council on Border Issues was created with seven members, headed by the retired king and including such political figures as opposition leader Sam Rainsy and Deputy Prime Minister Sok An of the CPP. The council was designed to help research border issues, provide advice to the government, and act as a watchdog on border disputes. On 11 May, Sihanouk chaired the first meeting of the council in Beijing, which was ostensibly organised to seek ways to resolve border conflicts with its neighbours, Vietnam, Thailand and Laos.Footnote 106 However, Sihanouk later commented, on his website, that,

To reach a consensus will be difficult as among the seven members of the council, there is one side who has clear position and sufficient proof on Cambodian territory that has been invaded by its neighbouring countries, whereas the other side is in a position to support 100 percent the royal government of Cambodia, and other members have no clear position.Footnote 107

Sihanouk was clearly referring to the opposition and the government respectively. Sam Rainsy was unsatisfied with what he saw as the GoC caving in to its neighbours' positions. Sok An and the CPP, however, supported efforts to resolve border issues with minimal upheaval.Footnote 108 The Cambodia Border Committee supported the position of Sihanouk.Footnote 109

There have been a number of points of disagreement over the Laos–Cambodia border, the most important being the border along the SekongFootnote 110 River between Attapeu and Stung Treng Provinces. The Cambodians claim that the mouth of the Nam Kong River constitutes the border on the east side of the Sekong River, whereas the Lao think the border is at the mouth of Dak Lao Stream, which is downstream from the Tangngao Stream, about 20–30 kilometres south of the mouth of the Nam Kong River. The Government of Cambodia (GoC) apparently tried to arrange for a Cambodian village to be established around Phai and Khanyou Islands, in the disputed area, but the GoL prohibited them from doing so. The settlers were told to leave the area because the place they wanted to settle was ‘Lao land’. The Lao military in Sanamxay District even considered taking military action, but calmer heads eventually prevailed. The Cambodians also withdrew. Lao villagers in Sanamxay claim that the Lao have always used the disputed land.Footnote 111 One ethnic Lao villager from Sompoy Village, Sanamxay District said that, ‘The area south of the Nam Kong River that the Cambodians want has always been part of Laos.’Footnote 112

In Sanamxay and Phouvong Districts in Attapeu, there has also been concern amongst ethnic Brao people living near the border that they would lose large amounts of territory situated south of the Nam Kong River and east of the Sekong River to the border with Vietnam.Footnote 113

Similarly, the redefining and marking of the international border between Khong District, Laos and Cambodia has resulted in dissatisfaction among local people. Part of the Xepian National Protected Area is now in Cambodia. The ethnic Lao village of Napakiap, in Khong District, is considered to be inside Cambodia, and much of the forests which were used by Lao villagers are now inside Cambodia, resulting in the area available for local people becoming quite limited. Illustrating the problem, in April 2005, ethnic Brao villagers in Phon Sa-at Village complained about how they had lost much of the land that they once used for fishing, hunting and Non-Timber Forest Product (NTFP) gathering. They claimed that they had been threatened with 50,000 Lao kip (about US$5) fines if they were caught on the other side of ‘the new border’.Footnote 114

In 2005, the GoC demanded that Lao soldiers based on what Cambodians claimed to be their land, withdraw immediately from the disputed area along the border between Siem Pang District, Stung Treng Province and Khong District, Champasak Province. In March 2005, the Phnom Penh Post reported that the Lao military had promised to leave Cambodian territory after negotiations took place between the governors in Stung Treng and Champasak Provinces. An unnamed Cambodian Ministry of Defence official stated that a Lao military base was 2–4 kilometres inside Cambodia.Footnote 115 The Lao press did not report on this incident.

Border negotiations

According to the ethnic Brao deputy district chief of Taveng District, Ratanakiri Province, and another Brao border policeman who works along the border, the Lao and Cambodians would like to use the 1945 French map of the border as a reference.Footnote 116 However, many question the veracity of this claim, and whether the map really is available in France.Footnote 117 In any case, it has not been found in either Cambodia or Laos. According to some, France does not want to provide their copy, for fear that Laos or Cambodia might accuse them of creating or altering the map more recently in favour of one side or the other. If there was another copy somewhere that could be used to verify that the 1945 map that the French have has not been altered, the French would, they claimed, be willing to provide it. Therefore, the two sides are, according to them, using the 1968 and 1973 maps as a temporary reference, until the time that the 1945 map can be found. In fact, this whole story may only be a rumour, but it is interesting how the French have become drawn into the border dispute.Footnote 118

Apparently most of the disputed areas are along the western border, while the eastern border between eastern Attapeu and eastern Ratanakiri has not been problematic. ‘Most problems are between Km 0 and Km 125, while from Km 125 to Km 145 there are none’, said the border policeman. He also claimed that the Cambodians had located a few cement border posts put up along the border during the time of the French. One is at the end of the Lalay (Heulay) Stream, while another was found in the Haling-Halang Mountain area. He stated that the mouth of the Nam Kong River is in Laos, but that the end of the Nam Kong is in Cambodia.Footnote 119

In February 2007, Dr Mongkhol Sasorith,Footnote 120 the legal advisor for the Department of Treaties and Legal Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Lao PDR, provided a somewhat different account of the Laos-Cambodia border dispute. He explained that the joint inspection of the Laos–Cambodia border initiated in 2000 had been completed, but that disagreements have prevented a final agreement between the two countries.Footnote 121

According to Dr Mongkhol, the French created a temporary border between Laos and Cambodia before 1945, but that its delineation was never completed. He explained that Laos and Cambodia have both agreed to base their determination of the border on French maps created between 1933 and 1953. The French apparently took the last set of aerial photos of the border area in 1952.Footnote 122

There are three places along the border that are still being disputed by both countries, claimed Dr Mongkhol. One is in the Xelamphao (Tonle Repou) part of the border, west of the Mekong River. There, the whole river was granted to Laos. He does not know for sure why this was the case, since there is no documentation about the reasoning behind the decision, but he suspects that it was given to Laos because Laos was giving up all of Stung Treng to Cambodia at the time the border was created. In any case, Cambodia has asked to be able to take drinking water for domestic uses from the Xelamphao River. The GoL is apparently willing to grant this to the Cambodians, but wants it to be clearly specified how much water can be taken from the river. For example, small-scale use might be acceptable, but the Lao do not want the Cambodians to extract water for large-scale irrigation projects, etc.Footnote 123

The second contested area is in the Dong Kralor/Kalor area, just east of the Mekong River. This is where Laos' national highway, Route No. 13, meets Route No. 7 in Cambodia. The only international border crossing point between Cambodia and Laos is located in this area. In particular, a 9 kilometre stretch of road near the border has been a source of disagreement.Footnote 124 In 2004–05, a conflict emerged regarding this section of the border. The Lao wanted to move the border crossing while the Cambodians insisted on maintaining the previous border crossing post. According to an ethnic Lao man working for the Stung Treng provincial government, military conflict almost broke out over this incident. He told me that the GoL authorised the construction of a new road to the border, but without seeking Cambodia's agreement. The Lao were supposed to stay within 500 metres of the border, in order to avoid being provocative. Twenty or 30 Lao soldiers simply escorted bulldozers to clear the forest for the road. They were 300 metres from the border when they saw some GoC officials and soldiers with guns who were, by coincidence, working on the Cambodia side of the border. The situation became tense, but the Cambodian side telephoned senior GoC officials, who in turn called senior GoL officials. Finally, the Lao backed off and road construction stopped.Footnote 125

The third area is probably the most contentious, and relates to the border between Attapeu and Stung Treng Province, east of the Sekong River, the area already discussed earlier. According to Dr Mongkhol, the border on the Sekong River is at Tamakhoi rapids in Sanamxay District, which is downstream from the Alai Stream. He claims that the land east of the Sekong River above those rapids is Lao territory, not Cambodian. However, Dr Mongkhol claims that the Cambodians believe the border is north of the Tangngao Stream, many kilometres upstream from the Tamakhoi rapids. Therefore, there is a chunk of land east of the Sekong River that both countries claim. Dr Mongkhol believes that most French maps support the Lao position, but that there is one French map that the Cambodians are using to justify theirs. Therefore, an agreement has so far not been possible. Dr Mongkhol is hoping that agreements on less controversial areas to the west will ultimately create the political space necessary to come to a final agreement.Footnote 126

It does appear that border relations between Laos and Cambodia have improved recently. This may be because of the increasing power of Hun Sen and the CPP, since they are more willing to work cooperatively with the Lao on border issues than other political parties in Cambodia. In addition, Norodom Ranariddh, who has been a vocal critic of Cambodian government immigration issues and border negotiations with Vietnam, and to a lesser extent Laos,Footnote 127 has become a less important player in Cambodian politics since starting up a new political party.

Indicative of the improved situation, the Dong Kalor border crossing dispute has been resolved, with the Laos and Cambodia governments agreeing to maintain the old border crossing point. The road along the border has been repaired and paved and the issue seems to have been resolved.

In addition, in June 2007 the governments of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam jointly agreed on the exact location of the tri-country border between the three countries,Footnote 128 further indicating that tensions along the border have subsided.Footnote 129 Most recently, at the end of May 2008, Var Kimhong, the chair of the Cambodia Government Border Committee, told the Phnom Penh Post that a final agreement with Laos regarding the border was expected to be achieved in June 2008. Kimhong said that only a few issues remained to be finalised. A senior official at the Lao Embassy in Cambodia also commented, ‘The Cambodia-Laos joint border committee has been working very smoothly and I think the relationship will get better in the future.’ Still, it appears that so far only 86 per cent of the border has been demarcated,Footnote 130 the same amount as was reported to have been completed 2.5 years earlier in early 2005. Only time will tell if a final agreement between Laos and Cambodia is really near, but as of early 2010, an agreement had yet to be announced.

One issue that has considerable potential to seriously damage relations between Cambodia and Laos are plans by the GoL to allow foreign companies to build a number of large hydroelectric dams near the border, including the Don Sahong Dam on the mainstream Mekong River, less than 1 kilometre north of the border, and a number of large dams in the Sekong River Basin in southern Laos, upstream from Stung Treng Province.Footnote 131 The Cambodian National Mekong Committee (CNMC) is unhappy with the GoL for failing to provide adequate or timely information about the dams planned in Laos, and their expected impacts on downstream parts of Cambodia.Footnote 132 While none of these dams have been built yet, tensions could rise considerably once they begin causing downstream impacts, which are expected to include significant water quality and hydrological changes and resultant negative impacts to the environment, especially important fisheries, and local livelihoods in Cambodia.Footnote 133

Irredentism and the Laos–Cambodia border

One of my first experiences with sensitivities surrounding the Laos-Cambodia border was in 1993, soon after I started living in Laos. The French non-governmental organisation (NGO), Écoles Sans Frontières (ESF), which was based in Vientiane, was preparing illustrated cartoon story books about each province in Laos. These books included important fables and short stories collected from each province. They were selected for publication by committees of local government officials. ESF was working on the book about Champasak Province, but publication was delayed. The French director of the project told me that the Ministry of Education had not approved the Champasak book. There was concern about the section dealing with the history of the ancient ruins of Vat Phou. Without fully realising the politics involved, ESF had explained that the Khom had constructed Vat Phou, a word mainly associated with the ancient Khmer, but which is sometimes used to describe highland peoples of the past. Officials in the Ministry took issue, as they were afraid that including such a statement could later be construed as Government of Laos (GoL) recognition that Champasak Province was once under the sovereignty of Cambodia, something that was not considered to be in the best interests of Laos. Instead, the officials at the Ministry wanted all mention of Khom or Khmer removed from the book. In the end, ESF was forced to comply. The book now claims that Vat Phou is an important part of Lao cultural heritage. The mix between Hindu and Buddhist civilisations is emphasised, and it is stated that the Cham were the first people to inhabit Champasak. The Khmer are not mentioned anywhere. The book also includes a map of Champa that shows its territory as extending to the ocean in present-day Vietnam, while incorporating much of present-day northeastern Cambodia. It is interesting that most Lao would prefer to historically link Champasak and Vat Phou to the Cham, even though most scholars feel that this is based mainly on the folk etymology of the name Champasak rather than historical reality. Perhaps this association between Champasak and the Cham is convenient for the Lao because the Cham are no longer significant as a people and thus have no potential claims over the region. In any case, the last sentence in the book claims Vat Phou to be Lao, stating, ‘Vat Phou is a symbol of Champasak Province and is the heritage of the Lao Nation…’Footnote 134

At a more local level, and as a result of Khmer claims that all places where Khmer inscriptions can be found should be part of Cambodia, some Lao people – apparently without GoL authorisation – destroyed ancient ruins in an attempt to remove evidence that might justify Khmer claims. For example, this happened in Houay Mo Village, Sanamxay District, Attapeu Province in around 2000 when villagers heard of Khmer irredentist claims about the presence of Khmer language inscriptions in southern Laos. A large flat rock slab (phalan hin in Lao) near a Sekong River rapid that had ancient Khmer inscriptions etched into it was smashed by unidentified people.Footnote 135

However, it is not just about Laos being sensitive about Cambodian claims to parts of southern Laos. Many Lao, especially older people, continue to claim that Stung Treng ‘is Lao’, referring to the large number of Lao first language speakers living in northeastern Cambodia, especially Stung Treng Province. They bemoan the decision by French colonial authorities to give Stung Treng to Cambodia at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 136 One woman from Veun Say, in Ratanakiri Province, told me, ‘This is only Cambodia in name.’Footnote 137 As Volker Grabowsky put it, many Lao feel betrayed ‘by the “loss” of Stung Treng or “Southern Champassak”’.Footnote 138 Symbolically, people in Laos frequently claim that Laos should extend as far as one can hear the sound of the traditional Lao bamboo pan-flute (khen in Lao).

Even considering recent high levels of Khmer immigration from other parts of the country into Stung Treng, it is still true that roughly half of the population of Stung Treng are ethnic Lao. Both Volker Grabowsky and Claire Escoffier greatly underestimate the ethnic Lao populations in northeastern Cambodia, especially in Stung Treng Province. They claim that there are 21 Lao villages in Stung Treng.Footnote 139 In fact, I have personally visited many more Lao villages in Stung Treng during various trips to the province since the early 1990s. Interviews with ethnic Lao people have indicated that there are actually more than three times that many villages with significant ethnic Lao populations.Footnote 140 There is also a substantial Lao population in Ratanakiri, and more minor Lao populations in Preah Vihear and Mondolkiri Provinces.Footnote 141 However, the ethnic Lao population in Cambodia is being increasingly Khmerised, especially as the national education system expands into remote ethnic Lao areas. Now, many ethnic Lao do not admit to having knowledge that much of northeastern Cambodia was once part of Laos. This may be true for much of the younger generation, of which at least some believe that their ancestors came from Laos but that the land they live on now has always been part of Cambodia. However, it is likely that many do realise that the region was once part of Laos but feel that it is politically untenable to acknowledge this.Footnote 142

I have been interacting closely with ethnic Lao people living on both sides of the border since the early 1990s when I lived in Hang Khone Village along the border between Champasak Province and Stung Treng Provinces, and since then I have also travelled to many parts of the province doing academic and NGO research on multiple occasions, more than it is possible to remember. Therefore, this research is, in many ways, a product of many years of low-intensity research. Yet, in some villages, especially in more remote areas, it is still common to hear ethnic Lao elders claim that Stung Treng (including Ratanakiri Province) was once part of Laos. However, the vast majority of the ethnic Lao there, even those who continue to value their Lao heritage, seem reconciled to their place as Cambodian citizens, and few express any explicit desire for any part of northeastern Cambodia to be reattached to Laos, or to even gain ethnic-based autonomy within Cambodia. However, other views do exist, even if they are not openly expressed.

This does not mean that irredentism is not still present in different forms. The situation for the ethnic Lao in Cambodia is complex. The ethnic Lao and Khmer in Stung Treng Province, especially Stung Treng Town, are particularly sensitive about the historical dominance of the Lao. For one, ethnic Lao people frequently prefer – or feel obliged – to refer to themselves as Khmer, even if their ancestors were all Lao and they use Lao as their first language. One ethnic Lao man in Stung Treng told me that people are afraid to admit that Stung Treng was once part of Laos because they do not want to ‘sia nayobai’ (betray government policy). During the Sihanouk period people were put in jail in Stung Treng and Phnom Penh for making such statements. He said that it is fine to talk about the Vietnamese and Chinese because they have samakhom (associations, registered organisations representing particular ethnic groups), but that it is different for the Lao.Footnote 143 This may be related to how the GoC has altered the discourses regarding the Lao population by officially labelling many of the ethnic Lao people born in Cambodia as Khmer, whereas only those actually born in Laos and who then immigrated to Cambodia are consistently referred to as Lao, even if they are already Cambodian citizens. Many ethnic Lao people born in Cambodia are classified as Khmer if they are Cambodian citizens, even if their first language is Lao. Some ethnic Lao citizens of Cambodia have also voluntarily adopted the Khmer identity.Footnote 144

The golden age of Angkor remains the defining period for most Khmer, and some Khmer believe that the Khmer kings once controlled at least as far north as the Vientiane Plain. While Xaifong, near Vientiane, was probably a Khmer settlement at the height of Angkorian power,Footnote 145 it was probably never an important base, and some have even questioned where the Khmer inscriptions there were moved from elsewhere. Furthermore, most of the Khmer expansion in what is now south-central Laos was probably west of the Mekong River.Footnote 146 In fact, it is unlikely that the Khmer ever controlled all the land as far north as Vientiane, including the mountainous hinterland areas to the east.Footnote 147 Instead, it may well be a product of Khmer irredentist historical creation. However, there are certainly many Khmer ruins in present-day Champasak and Attapeu Provinces in Laos, and this was used by some Khmer, including Sarin Chhak,Footnote 148 to justify why present-day southern Laos should rightfully be part of Cambodia, even though there are very few people in present-day southern Laos who exhibit Khmer-like cultural or linguistic characteristics, or self-identify as being Khmer.

Some Khmer believe that it would be better for Cambodia not to come to a border agreement with Laos. Some of those apparently justify resolving the border conflict with Vietnam because there are many more people in Vietnam compared to Cambodia, making a military struggle to regain more territory from Vietnam unrealistic for Cambodia. However, Laos has about 6 million inhabitants, less than Cambodia's estimated 14 million people. They see the Cambodian government's seemingly soft treatment of the border conflict with Laos as representing weakness. Cambodia, they believe, is in a numerically advantageous position, and should be more aggressive in ‘regaining more Cambodian territory’ from Laos. According to a Khmer friend, those who espouse such views ‘want to gain more land in the future’, and believe that coming to a border deal with Laos might make future military efforts to gain territory from Laos problematic. Waiting for future opportunities is what they advocate.Footnote 149 Many also believe, despite not visiting the border or any direct evidence, that the Lao have systematically shifted old French border posts to the south, to gain land from Cambodia.Footnote 150 It should, however, be recognised that accusing others of moving border markers is frequently a discursive strategy associated with irredentism.Footnote 151

The Khmer seem, in fact, to be more troubled with much of northeastern Cambodia once being part of Laos than are the ethnic Lao with being in Cambodia. Indicative of this, in 2003 I co-authored a report for the Ministry of Environment that dealt with the history of the ethnic Brao Umba and Brao Kavet people in relation to Virachey National Park, which is adjacent to the eastern border between Cambodia and Laos.Footnote 152 In explaining the history of the region, we mentioned that in 1905 Stung Treng had been taken from Laos and given to Cambodia. The director of Virachey took issue, and insisted that we remove any references to northeastern Cambodia previously being part of Laos in our report. We refused to knowingly alter this important historical fact. Finally, after extended negotiations that also involved other matters,Footnote 153 we agreed to alter our report to state that Stung Treng had been ‘given back’ to Cambodia. For the Khmer park director such a statement at least affirmed Cambodia's rightful possession of the northeast.

The way the ethnic Lao in Cambodia are depicted is a good indicator of national views. In the standard grade 12 social studies Khmer language textbook, there is a section about the ethnic groups of Cambodia.Footnote 154 It presents Cambodia as a multi-ethnic society, and promotes ethnic tolerance, but despite having sections about the Chinese, Vietnamese, Cham and ‘ethnic minorities’ (highlanders), there is absolutely no mention of ethnic Lao people living in Cambodia. It appears that the ethnic Lao in Cambodia have become the subjects of a discourse of silence; a discursive erasing of their presence from the country. It is hard to know exactly why the Lao have been subjected to this discourse of silence more than the Vietnamese and Chinese, but it may be because the Lao have historically been numerically more populous than the Khmer in northeastern Cambodia, thus representing a more important threat to Khmer land compared to the Vietnamese and Chinese, who can more easily be historically situated as newcomers. It may also be because the northeast is arguably the only part of Cambodia where the people are mainly ethnically linked to another country, thus going against the Cambodian view that most Khmer land has been taken by others. In any case, the tactic seems to have worked to some extent, as Jan Ovesen and Ing-Britt Trankell (2004)Footnote 155 discussed the same ethnic groups as the textbook, but failed to mention the Lao.

Irredentist ideas of this nature are frequently evident in Cambodian discourses. For example, a Khmer commented on a web chat site in 2008 that,

The truth is, the Khmer existed and inhabited mainland Southeast Asia before the Thais, Lao, Burmese and Vietnamese came along. The Thais and Lao came from China and settled down in our territory at the time of the Khmer empire.Footnote 156

In fact, this claim is not entirely untrue, but it is especially noteworthy that this is a very important point in the minds of many Khmer.

Some of the discourses that have emerged to Khmerise the Lao in Stung Treng are more surprising. A young ethnic Khmer man originally from central Cambodia but working for a local NGO in Stung Treng committed to cultural and environmental protection told me and another colleague, in Khmer, that all the people in Stung Treng were actually Khmer, not Lao. He claimed that the reason why so many of the villagers that they work with in the province speak Lao is because the Khmer Rouge forced them to speak Lao, and so they became used to it and still speak Lao today!Footnote 157 What we can say for certain is that the Khmer Rouge were intensely nationalist, and that while they sometimes tolerated the use of ethnic minority languages in the northeast, including Lao, their tendency was always to push for the increased adoption of Khmer, especially after 1975 when they gained full control of the country.Footnote 158 In fact, they forced many ethnic Lao people to speak Khmer, not the other way around. They certainly did not try to force ethnic Khmer people to speak Lao. At first, we thought that the story teller must be joking, but it soon became clear that he was quite serious. Even when we tried to explain that his story was implausible, he remained convinced that he was right.

In 2005, a year later, a Khmer language article appeared in the same NGO's Nature and Life Bulletin. It was titled, Why do Khmers in Stung Treng speak Lao? Footnote 159 The author(s) explain that 65 per cent of the population in Stung Treng speak Lao. They then ask, ‘Are these people ethnically Lao?’ Surprisingly, their answer is, ‘No’. Five reasons are given for this (none of which related to the Khmer Rouge argument presented by someone from the same organisation earlier). They include that (1) Lao people fled the civil war in Laos following 1954 when Cambodia achieved peace; (2) during the Pol Pot regime, Khmers fled to Laos; (3) Khmers use Lao language to trade with Lao speakers; (4) the education infrastructure in Cambodia was destroyed by the civil war, so people did not have the opportunity to learn Khmer; and (5) Cambodia and Laos share a common border. There is clearly an attempt to reconstruct ethnic Lao people as Khmer.

Later, the author(s) recommend that the government develop Stung Treng Province so that children can go to school and learn Khmer, that good teachers be provided and encouraged in Stung Treng, and that ‘provincial authorities need to take measures to get people to speak Khmer’.Footnote 160 The final sentence in the article, translated from Khmer, is ‘We hope that in the near future, all the people in Stung Treng will have the opportunity to use the Khmer language more in communicating with each other in an environment of happiness.’Footnote 161

Conclusions

Just over 100 years have passed since Stung Treng was removed from Laos and given to Cambodia, but the international border between the two countries is still not entirely clear, and both sides continue to retain irredentist views regarding the border. Some Lao, both in Laos and Cambodia, believe that Stung Treng should rightfully be part of Laos, while some Khmer in Cambodia contend that at least part of southern Laos should be part of Cambodia. Lao claims to Stung Treng are mainly based on the fact that the province was under Lao control in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and that there remains a substantial, but frequently under-recorded, Lao-speaking population in northeastern Cambodia. Khmer claims to southern Laos are more anachronistic, dating back to the presence of Khmer people in southern Laos during the Chenla and Angkor periods.

However, despite these often subtle irredentist feelings, in northeastern Cambodia most ethnic Lao people now largely see themselves as being legitimate members of the Cambodian nation, even if many also see their Lao cultural and linguistic heritage as important.Footnote 162 As Frederick Barth classically revealed, ethnic identity boundaries often shift to match the state-defined identity boundaries,Footnote 163 even if this has not entirely been the case for the ethnic Lao living in northeastern Cambodia, who have retained an element of human agency in identity. Most of the Lao in Cambodia identify both as being Cambodian at the national level, but also frequently as ethnic Lao and thus connected to Laos through ethnicity, if not nation. These ethnic Lao frequently travel to Laos, to meet friends and relatives, and to do business, thus being able to represent themselves in various ways, depending on the spaces that they are in. For example, they can represent themselves as Cambodian with the government, and when in Khmer dominated areas, while in private homes, villages dominated by Lao, and in Laos itself Lao identities can more easily flourish. There are Lao and Khmer spaces in Cambodia.

Despite the increasing integration of the Lao into Cambodia, the Cambodian government appears to have adopted a discourse of silence in relation to the ethnic Lao living in Cambodia, which involves various efforts to Khmerise the Lao. This contrasts with the discourses surrounding the Chinese, Vietnamese, Cham (Khmer Islam) and ethnic minority highlanders (Khmer Loeu) in Cambodia, groups that are openly acknowledged as being in Cambodia, and are viewed differently by the state in terms of their place in the country,Footnote 164 probably because the view of most Khmer about themselves as being victims of their neighbours is the most easily challenged historically and ethnically in Stung Treng, thus making it preferable to ignore the Lao issue entirely.

The lingering irredentist views on both sides of the border are not about to disappear, and are important for understanding the present situation on both sides of the Laos–Cambodia border. But neither are they likely to escalate to serious political or armed conflict in the foreseeable future, especially considering the relatively good relations between the Lao People's Revolutionary Party and the Cambodian People's Party. Furthermore, these parties have tended to have less irredentist views compared to Lao and Khmer rightist and neutralists, and the Khmer Rouge. However, potential problems related to large dams being planned in southern Laos and their downstream impacts in northeastern Cambodia could increase border tensions in the future.