From around the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, photography was employed by the colonial state and industry to document their advances and successes in the colonies as well as create knowledge of and maintain power over the colonial subject. A marvel of Western technology, the camera was used and controlled by Westerners imag(in)ing the Orient: formulating pictorial narratives about the exotic landscape and people in the colonies and constructing stereotypical representations about race and ‘the wild’. Portraits of colonial subjects, both plain and genre scenes, were originally produced by itinerant foreign photographers and local studios to cater to the tourist demand for souvenirs as much as the curiosity of metropolitan audiences whom they reached as postcards, prints and book illustrations.

Postcolonial debates often focus on the intrusiveness and manipulating power of the ‘colonising camera’ and the ways power–knowledge relationships informed the formulation of a colonial visual culture in which the colonised were ‘othered’ without being able to take full control over their representation.Footnote 1 Whether privately or state-owned, much of such imagery is now part of ‘colonial’ collections kept in museums, libraries, archives and universities of former colonial powers, knowledge-producing institutions that defined what kind of historical memory would be preserved.Footnote 2 These metropolitan archives played a central role not only in the establishment of a narrative of colonial ‘othering’, but also in the formulation of national consciousness enhanced by feelings of colonial supremacy and pride.Footnote 3

The social life of such colonial imagery took a different turn within the developing culture of re-imag(in)ing the colonies which gained cross-disciplinary momentum in the postmodernist discourse of the 1980s, and the so-called ‘archival impulse’ of the following decade.Footnote 4 Overturning the authority of colonial rule, postcolonial scholarship has re-examined and re-contextualised colonial photographic material, displacing the emphasis from the coloniser looking at the colonised to the former colonial subjects, while exposing the artifice and contrivance of such archival records.

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, digitisation has also altered the performance of the colonial archive anew, making archival material accessible to a much wider and geographically dispersed audience beyond the confines of the physical archive. In the face of digital dematerialisation, debates around the physical attributes of photographs as objects, long overshadowed by image content and its indexical properties, have gained momentum.Footnote 5 A photograph's ‘material performance of the past’ — such as torn corners, scratches, marks, faded areas, fragility, verso, studio stamp, handwritten message — are indexical signs that form its biography and history.Footnote 6 Yet, the process of digitisation tends to deprive photographs of their social life as their biography and active role in history, inscribed in this very materiality, is often concealed behind the need for uniformity and archival taxonomy. ‘Normalisation’, so that digital surrogates are ‘readable’, and uniformity of size may often result in ‘misrepresenting the physical character and relationships objects held’ as well as concealing important information that may have not been originally scanned.Footnote 7 Along with concerns around preserving the material culture of archival records, the online open access publication of archival collections raises issues around ownership, authorship and copyright for repurposed archival material.Footnote 8

Arjun Appadurai argues that by dismantling the social history of things we retrieve the meaning that was originally inscribed in their forms, uses, trajectories and how different social encounters had structured and restructured them in different historical contexts. Appadurai highlights the fundamental and active role of objects in human relations over their physical role as mere artefacts.Footnote 9 By following the trajectory of things and their ability to move in and out of different sociohistorical contexts, we can see the shifts in their social, cultural and historical value over time.

This article seeks to examine the ‘social life’ of colonial photographs kept in Dutch museums and archives and the ways such imagery has been recently reconfigured, manipulated and repurposed by contemporary Southeast Asian artists to contest the use, truth value, authorship and ownership of the colonial archive. Recontextualised and repurposed online on different platforms, their work becomes part of the expanded postcolonial archive and proposes a reframing not only of the politics of colonial representation, but also of the validity and veracity of the photographic image as evidence and historical record. We specifically argue that the transition from the material colonial archive of the twentieth century to an expanded dematerialised postcolonial archive in the twenty-first century also makes possible a shift in power relations, allowing formerly colonised subjects to have unprecedented access to and control over the representation of their history.

‘Archivising’ the tourist imagination

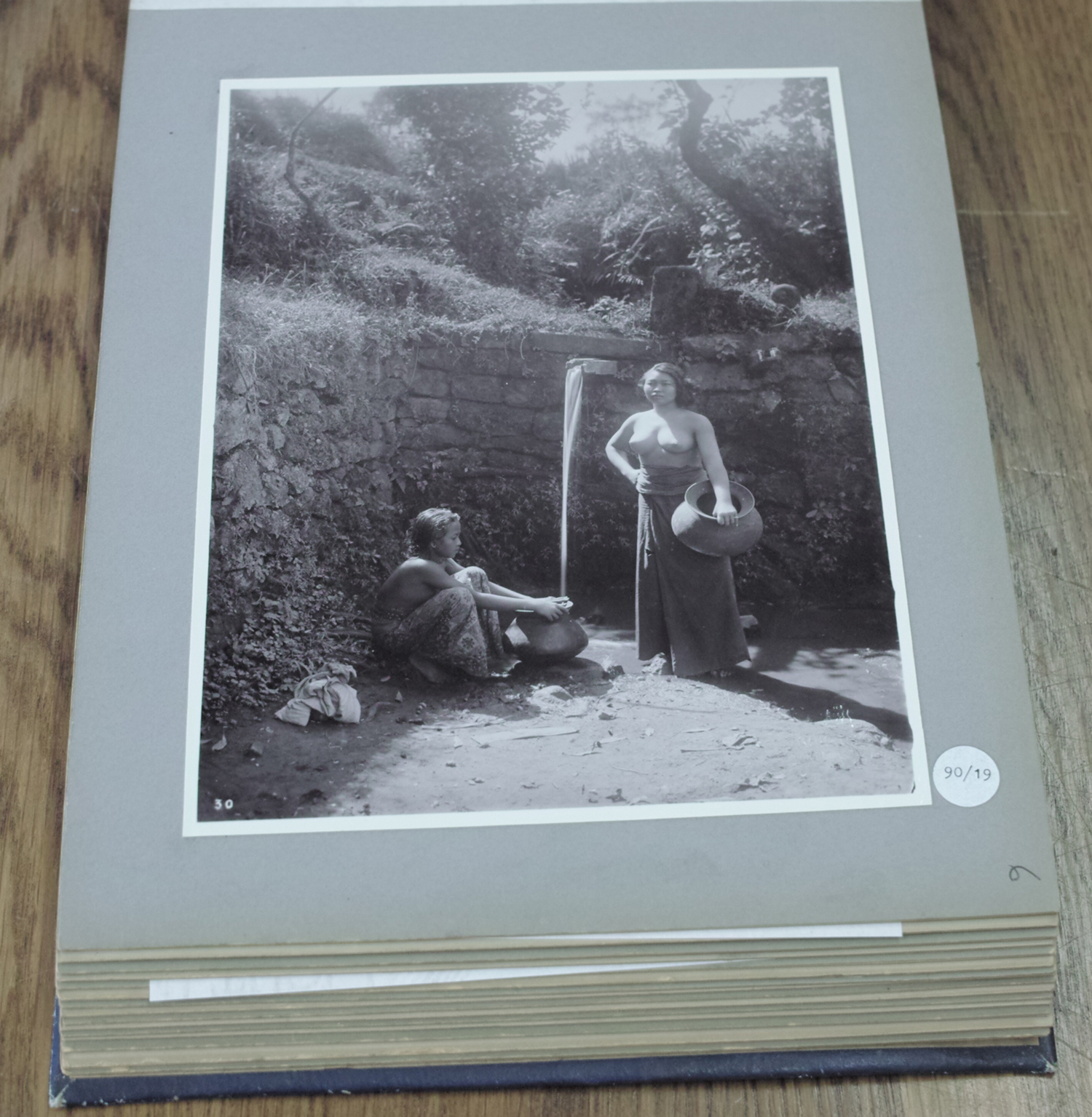

Two young Balinese women are captured while collecting water from a spring (fig. 1). A ray of sunlight penetrates the lush tropical vegetation to caress the bare breasts of the standing woman who looks as if she momentarily paused to pose for the photographer. She returns their gaze, looking back at the camera while her companion, sitting on the ground, timidly looks away. The portrait is a typical souvenir photograph produced by the commercial photographic studio Kurkdjian & Co., the initiative of the Armenian photographer Ohannes Kurkdjian (1851–1903), who having worked in Yerevan and Singapore, established a large commercial studio in Surabaya during the Dutch East Indies period. As the number of similarly themed photographs in the Kurkdjian & Co. atelier and other local studios’ collections indicates, bare-breasted Balinese women were a major attraction to foreign eyes. However, the photograph in fig. 1 is distinguishable from other images of scantily clad exotic women taken in local studios to be marketed as soft erotica.Footnote 10

Figure 1. Kurkdjian & Co. Photo Studio, ‘Two Balinese women at the well’, c.1905, from the album Bali, ALB-160, p. 5, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Coll. No. 60019067.

Although the photograph is credited to Kurkdjian & Co. Photo Studio, there is strong indication that the studio's portfolio of Balinese women was produced by Thilly Weissenborn (1889–1964), the first female Indonesian-born photographer in the Dutch East Indies. As Adrian Vickers wrote elsewhere, several series of photographs under the label of Kurkdjian & Co. Photo Studio, including photographs of Balinese subjects, were attributed to Weissenborn in 1914.Footnote 11 Indeed, Weissenborn's sensitivity to tropical light, which bore strong pictorialist undertones, is evident in the photograph in question.Footnote 12 Suggestions that the photograph's focus on the sitter's breasts manifests masculine gaze bias may be contradicted by the self-confidence of the young woman: standing firm, staring back at the camera operator, one hand on her hip and the other one carrying a terracotta water receptacle. Her pose states her refusal to be ‘othered’ as a passive object of erotic fantasy as much as the photographer's intention to showcase the women's ‘dignity and self-possession’, which characterised Weissenborn's photographs of Balinese women.Footnote 13 Nonetheless, such a naturalisation of the ‘exotic’ bare-breasted woman within local customs and daily life made the image appropriate for general sale, alongside photographs of landmark sites, landscapes, antiquities and local customs that comprised the portfolios that commercial photographic studios in the Dutch East Indies made available to clients and tourists.Footnote 14

The photograph in question is part of an album entitled Album Bali (c.1905) that originally belonged to the family of Antoine Pietermaat-Soesman, the general manager of the Kalibagor sugar factory in West Java between 1914 and 1928. Religious rituals, local customs and picturesque vistas of the island adorn the pages of the elaborately crafted album, painting an almost paradisiacal world.Footnote 15 The quality of the photographs and their uniform presentation suggest that this album was, most probably, commercially prepared by the Kurkdjian & Co. Photo Studio rather than compiled by the family. The photograph and the album made their way to the Colonial Museum in Amsterdam (subsequently renamed Tropenmuseum) in the 1920s when Pietermaat-Soesman's widow donated their albums.Footnote 16

The Tropenmuseum currently houses 2,744 photographic albums (around 175,000 photographs), 10,000 individual photographs, 80,000 negatives and 7,500 slides and stereo slides, most of which were donated by Dutch, European and Eurasian families that lived in the Dutch East Indies.Footnote 17 In the public domain of the museum, these private albums are no longer merely visual chronicles or tokens of a family's story in the colony. Their social value shifts as they become records of Dutch colonial history, visualising the history of the colonial state, the colony and photography, as the image in fig. 2 aptly illustrates.

Figure 2. Anon., Slide projection at the laboratory of the Colonial Institute's Tropical Hygiene Department, Amsterdam, 1920–40, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Coll. No. 60036893.

Decades after its production, the photograph of the two Balinese women was used in a lantern slide presentation in the Tropical Hygiene Department of the Colonial Institute (fig. 2). One can only assume that bare breasted and barefoot women using terracotta water containers to collect water for domestic purposes were used to illustrate the living conditions in the Dutch East Indies. In the early twentieth century, the introduction of the ‘Ethical Policy’ (Ethische Politiek, 1901–42) exposed poor living conditions and hygiene in the Dutch East Indies to the metropolitan public, with reports, photographs and films on the subject published, distributed and discussed in the Netherlands.Footnote 18 The photograph in fig. 1 is not part of the Ethical Policy's dossier though. Another print of this photograph exists in a commemorative album for the official visit of Governor General J.P. Graaf van Limburg Stirum to Surabaya in July 1917, also kept in the Tropenmuseum collection.Footnote 19

The original intention behind the making of the photograph in fig. 1 was to record local customs in Bali. In the Colonial Institute's Tropical Hygiene Department, the photograph was detached from the context of the souvenir album to offer visual evidence for a discussion that was in line with the campaign for better sanitary conditions and clean water in the colony. A close examination of the image in fig. 2 reveals that the clear-cut outline of the photograph of the two Balinese women does not match the uneven surface and creases of the projection screen, thus indicating that rather than being captured during the lecture, the image was skilfully inserted into the photographed scene in the darkroom. The reason behind the collaging was most probably the technical inability to sufficiently expose both the audience in the dark room and the projected image in detail onto a single negative. As such, we cannot be sure whether the photograph in fig. 1 was indeed projected during the lecture. Still, the fact remains that in the composite print in fig. 2 the use value of the photograph of the Balinese women was purposefully changed: instead of serving the tourist imagination, it highlighted Western ‘cleanliness supremacy’ then and in the future.Footnote 20

The abovementioned case is perhaps an exaggerated example of Jacques Derrida's proposition that the ‘technical structure of the archiving archive’, that is, the very methods and technologies of collecting, transmitting and preserving data, affect not only what is preserved for future reference but also the very knowledge that can be produced from archival records. And indeed, in this instance, almost literally, ‘archivisation produces as much as it records the event’.Footnote 21 The digitisation of the Tropenmuseum collections, available online in the new millennium as another mode of archivisation, offers new ways for knowledge production based on its archival records. The online platform facilitates access to diverse users who would not ordinarily have access to the physical archive in Amsterdam, whilst the properties of the digital proxies allow for further dissemination and repurposing of the archival record beyond its institutional context.

Mimicking the contextual and technical shift in the use and exhibition value of the photograph of the Balinese women, contemporary Thai photographer, Dow Wasiksiri created a hybrid image to underline the transformation of the photograph of the Balinese women from an exotic token in the family chronicle in the colony to an object of scientific enquiry in the metropolis. In this unpublished creative experiment, Wasiksiri replaces the original image of the Balinese women with an iconic colour photograph of the first plane crashing into one of the World Trade Centre towers on 11 September 2001. Wasiksiri inserted himself in the picture as a twenty-first century presenter, who informs his early-twentieth-century audience about the attack in New York City in 2001. Wasiksiri shifts the power–knowledge relations proposed in the original collage and claims agency for the educated Asian man in formal Western dress who showcases the ills of the West. The present is symbolised by the colour of the contemporary additions to the archival image: the artist as a speaker, the iconic image of the 2001 attack, and the digital projector. By using such overt digital manipulation, Wasiksiri is also visually commenting on the crude handcrafted manipulation of the original photograph in fig. 2, whilst questioning its authenticity and truth value as historical record and the authority of the archive as an institution. Considering that Wasiksiri spent almost twenty years studying, living and working in the West, the composite photograph may also be read as a comment on the artist's own position: an Asian man in traditionally Western ‘shoes’.

Wasiksiri's photograph is part of his series Past to the present and present to the past, the seeds of which were sown during the ten-day (Post)colonial Photography Workshop for invited Southeast Asian artists, facilitated by one of the authors, Alexander Supartono, in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2012. The workshop, one of the earliest of its kind in Southeast Asia, was organised in conjunction with the touring exhibition programme of the three-year research project Sweet and Sour Story of Sugar (2010–13). Initiated and managed by Noorderlicht Photography in the Netherlands, the project was a photographic investigation of the globalisation process through the commodity of sugar in the former Dutch Empire. It brought together colonial photographic material and specifically commissioned photographic work with a view to shedding new light on the mechanisms of economic and cultural globalisation through the development of the sugar industry in Indonesia, Brazil, Surinam and the Netherlands.Footnote 22 The aim of the workshop was to engage invited Southeast Asian artists working with photography to creatively reflect upon photographic practices in the Dutch colonies, drawing on photographic and contextual material from the collections of the Tropenmuseum and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the KITLV Archives in Leiden.Footnote 23

The twelve invited Southeast Asian artists and photographers were selected on the grounds of working with local archival material and/or themes relating to national and regional histories.Footnote 24 The artists’ collective dialogues led to a unique cross-fertilisation of ideas and practices that explored the interface of photography and (post)colonialism as well as the function and afterlife of the archival photograph in the colonial archive. These dialogues on the politics of (post)colonial re-presentation were further expanded as participating artists developed work using the abovementioned archival material that was subsequently disseminated online via different Web platforms and physically in art and photography festivals and museums in Europe and Asia.Footnote 25

In what follows, three bodies of work that merge the colonial past with the postcolonial present will be examined. Dow Wasiksiri, Yee-I-Lann and Agan Harahap capitalise upon the malleability and flexibility of digital archival records and the versatility of digital software to disrupt, subvert and reclaim agency in colonial representations. These artists revisit, adopt and adapt representational practices, mannerisms, iconographic clichés and commonplaces performed by foreign and local photographers in the colonial period to subvert history and memory.Footnote 26 By circulating their work across different physical and online platforms the artists also test Michel Foucault's definition of the archive as a system of ‘discursivity’ that defines the axis of what can be uttered and propose their own regime of truth.Footnote 27

‘Colonising the colonising camera’

In his series Past to the present and present to the past, Wasiksiri visually combines iconographic clichés of Dutch East Indies colonial society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and contemporary scenes of the new tourist industry in Southeast Asia. Confronted with such odd pictorial juxtapositions, viewers are asked to consider the role of photography in objectifying and defining ‘the other’ as did the artist himself during his intellectual and artistic formation away from his native Thailand.

The son of a Thai diplomat, Wasiksiri often moved cities and countries during his childhood. In 1963, his family moved to Canberra, Australia, only to move again, two years later, to Wellington, New Zealand, where he finished school and studied architectural design. It was there, at the age of 13, that his interest in photographic portraiture and popular culture began, interests that he would pursue more systematically after his move to Los Angeles in the late 1970s. During his studies in film, photography, radio and television in California, Wasiksiri was intrigued by the constructed photography practices showcased at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.Footnote 28 Californian artists tended to regard photography as ‘an art of invention’ rather than a ‘figment of the real world’, the kind of ‘snapshot’ photography promoted by Nathan Lyons or John Szarkowski's ‘New Documents’ celebrated at New York's Museum of Modern Art on the east coast.Footnote 29 Upon his return to Bangkok in the 1980s, Wasiksiri would adapt the Surrealist undertones and aesthetic extravaganza of American-constructed photography to his professional practice in fashion photography and magazine work under the name Studio Persona.

Having lived for many years outside Asia, Wasiksiri returned to his homeland with fresh eyes and a keen interest in exploring everyday life in Thailand, its native and imported cultures and historical legacies. Photography in Thailand in the 1980s was dominated by what Clare Veal has described as ‘Thai pictorialism’, an idiomatic camera-club style promoted by the Royal Photographic Society of Thailand since the 1950s in their intra-muros photography exhibitions and competitions.Footnote 30 Thai pictorialism promoted ‘attractive, beautiful, lovely and pleasing’Footnote 31 ways of rendering nature in images that would, in the words of the Society's president, ‘stir emotion’.Footnote 32 Aiming to humorously undermine this pictorial mainstream, Wasiksiri's project Urban who, initiated in the 1990s, purposefully encapsulated surrealist incidents in Bangkok's street life.

In the same spirit, the thematic series Local fashion around Kad Luang market (2010–12) explored the aesthetic and narrative opportunities of chance encounters. In this series Wasiksiri revisited the nineteenth-century device of the photo-booth (a portable white backdrop to isolate sitters within an outdoor setting) employed by itinerant photographers operating in colonial terrains.Footnote 33 The project originally started in the context of the centenary celebrations of the Kad Luang market in Chiang Mai, one of the largest in Thailand, but soon expanded to markets in neighbouring countries. Using colourful local fabrics and materials as backdrops, from vinyl to tablecloths sourced at market stalls, the artist asked passers-by to stop and pose for him while by-standers and market workers held the fabric as a makeshift photo-booth. Wasiksiri targeted people who were not interested in fashion as such, but who are ‘uniquely interesting’ themselves, and whose clothes combine eclectic styles and materials.Footnote 34 In one image, two men pose topless showcasing their elaborate tattoos and piercings, holding a yellow floral fabric stretched behind their backs and over their heads, while in another, two young women in traditional sarongs and branded bags look timidly at the camera against a purple-patterned cloth held high by two boys. Unlike nineteenth-century itinerant photographers, however, Wasiksiri did not conceal the artifice of his endeavour: his helpers and the market are visible at the edges of the backdrop. At the same time, he encompassed the chance elements and serendipity of street photography: a hasty passer-by walks into the frame in one instance; an impatient toddler walks out in another. This is where the influence of the American traditions of the street and the studio become visible, only to be undermined in Wasiksiri's pictorial idiom that is equally a clin d'oeil to the region's rich photographic history, referencing historical studio and in-situ portraits of indigenous folk marketed by local commercial studios for tourists.

This interest in the roots of Southeast Asian photography was accentuated in the series The oldest market in Chiang Mai (2012) in which the artist juxtaposed the triviality and colourfulness of the buzzing people's market and everyday street life with monochrome cut-out figures of studio portraits held by participating passers-by. With this intervention, Wasiksiri interrupted the presentness of the depicted contemporary scene by injecting the past into the present. At the same time, he also contested the truth value and seeming authenticity of the street photograph, an intervention that was a prelude to his next series Conversation with the past (2013) in which he revisited and subverted pictorial stereotypes in colonial studio portraiture.

In these composite studio portraits Wasiksiri inserted himself in saturated colour in the archival black-and-white photograph as an agent of the present but also a bearer of modernisation. In the photograph, ‘It's plastic but trust me’ (fig. 3), he invades a typical studio-based genre scene produced for the tourist market. A young Indonesian woman in traditional batik attire is kneeling on the floor before an unmistakably exotic painterly landscape punctuated by tall coconut trees.Footnote 35 She is depicted as a street vendor selling local fruit. This photograph is part of a studio portrait series depicting Javanese customs, produced by a local commercial photographic studio at the turn of the nineteenth century. Wearing a bright blue suit and contrasting red spectacles, Wasiksiri is kneeling before the woman offering to buy an apple using a gold credit card. The puzzled look on the face of the woman and the artist's purposely patronising posture and utterance complete the story. In another image entitled ‘Fancy a cup of Java’, Wasiksiri replaces an elderly female priest from the original photograph sitting cross-legged between two young Balinese women in a religious ceremony.Footnote 36 Carefully planted insignia of global capitalism punctuate the picture: a Starbucks cup and the McDonalds signature logo on a take-away food box make a visual comment on the Westernisation of Southeast Asia and how new mores are replacing old rituals for the younger generation. In the image ‘It comes with instructions’, Wasiksiri hands a branded toy figure to a young boy posing in Western attire and traditional hat (kopiah) next to his father against a Western-style backdrop complete with painted lamppost. Visualising the aspiration to Westernise the local social elite involved in the colonial enterprise, this studio portrait is the opposite of the practice of localising colonial subjects in ‘natural’ settings as exemplified in fig. 1.

Figure 3. Dow Wasiksiri, ‘It's plastic but trust me’, from the series Conversation with the past, 2013.

Unlike his previous series, Wasiksiri took advantage of the high definition digital copy of the archival photograph to insert his likeness almost seamlessly into the portraits; it is the use of colour that purposefully gives away the contrivance. Wasiksiri's exaggerated postures also direct the viewer to the artificiality and orchestration of the colonial studio portrait and how those often absurdly staged images formed the knowledge of the colony in family and corporate photographic albums and the colonial archive.

The question of agency and who has authority over whose representation becomes central in the series Reframing the present (2013), in which the device of an empty passepartout reframes, packages, suppresses and reveals layers of local history. In the work ‘Choose your history’, for example, a contemporary family of Muslim Javanese tourists are framed in front of the Hindu temple of Prambanan in Yogyakarta (fig. 4). Their gaze and posture indicate that they are posing for a souvenir picture, but the photographer they are returning their gaze to stands outside both frames. As it is today, posing in front of landmarks was common practice for the colonial-era foreign traveller, as was collecting picturesque views, often with indigenous folk to indicate scale and enhance local colour. Wasiksiri replaced the view of the monument with a painterly recreation of the exotic landscape and reframed the family in the colonial photographic studio surrounded by props that functioned as insignia of status in colonial society. It is this very use of the studio backdrop and props that indicates, as Appadurai has argued, the different claims of photographic representation in the colonial and postcolonial periods.Footnote 37 Moving from the plain, neutral backdrop that attested to the ‘documentary realism’ of the colonial gaze, the elaborate fictional backdrop of the postcolonial era offered sitters the opportunity to symbolically own what was unattainable to them in their social world.Footnote 38

Figure 4. Dow Wasiksiri, ‘Choose your history’, from the series Reframing the present, 2013.

In this complex narrative, the roles of medium and agency, in the presence of the studio camera, visible at the edges of the frame, in the artist's own hand holding the passepartout and the implied presence of the absent photographer, raise questions not only about the authorship and authority of (post)colonial representations. Looking outside the frame, the sitters appear as if they ignore the eye of the colonial camera. By placing them between two backdrops, a real and a painted one, Wasiksiri highlights how decolonised subjects revisit their past to reclaim their history.

In another work entitled ‘Disorientalism’, Wasikiri replaced the object of the tourist gaze in the present with a photograph from the colonial past (fig. 5). He montaged his photograph of a group of Western tourists in the Sultanate Palace of Yogyakarta and Kassian Cephas’ 1896 photograph of a tram bridge over the Progo River outside Yogyakarta.Footnote 39 The latter is taken from another Pietermaat-Soesman family album, this one entitled Views from different places featuring the family's journeys around Java visiting holiday resorts, relatives and friends. Most probably, the Pietermaat-Soesmans purchased Cephas’ photograph as a souvenir when they visited the city.

Figure 5. Dow Wasiksiri, ‘Disorientalism’, from the series Reframing the present, 2013.

In the original turn-of-the-century photograph, against the backdrop of modern engineering, that is, the iron bridge, Cephas staged three figures in the foreground to illustrate the hierarchy of colonial society: two Javanese, who sit on the ground, look up at the European, who looks over the bridge. This was not simply an image that catered to the aspirations of Cephas’ clientele. The Javanese Kassian Cephas was the first native Indonesian photographer in the service of the Yogyakarta court, and also worked for the Dutch Archaeological Union. In 1888, Cephas applied for himself and his sons to be granted legal status equivalent to Europeans.Footnote 40

Wasiksiri's twenty-first century photograph depicts a group of Western tourists inspecting the Yogyakarta Palace, whilst a Javanese man stands outside the frame oblivious to the scene on his right. In this elaborately composed picture, Wasiksiri contrasts the object/subject of the Western gaze: in the past, it was the modern infrastructure of the tram bridge for colonial industrialists; in the present it is the traditional architecture of the Sultanate Palace for tourists; in the past, the two Javanese men looked up at the Western man, while in the present the Javanese man ignores the Western tourists.

Wasiksiri recontextualises the domesticated industrial landscape from a family album into a public display. He confronts the Western tourist at leisure with a public discourse on the country's colonial past. Viewers are invited to examine the differences and similarities of their gazes: the colonial gaze over the industrialised colonial landscape and the tourist gaze in the present. This literal and metaphorical framing, whilst adding another layer to the photomontage, evokes the physical context of both photographs. The double framing, in which the local Javanese man stands in between frames, manifests another gaze: that of the viewers of this postcolonial reworking. Exposing the ideological contrivance of the archival records by re-enacting and de/reconstructing colonial portrait and landscape photographic practices, Wasiksiri endeavours to colonise the colonising camera, proposing a reversal of power.

Picturing power and the power of the picture

In the series Picturing power (2012), the Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann revisits the colonial use of the camera in claiming territory and creating knowledge about the colony. She investigates photography's embodiment in imperial power, manifested in different colonial projects: from documenting, registering and conquering unknown territories, to the celebration of the colony's modernisation and industrialisation.

Born in Malaysia, but having studied photography and cinematography in Australia in the early 1990s, Eurasian Yee revisits, time and again, Malaysia's unresolved national identity and its relationship with the colonial past. Yee belongs to the new generation of Southeast Asian artists who have embraced postmedia practices. Working with found photographs and collage since her student years, Yee also incorporates her working methods and expertise as a production designer and art director in the Malaysian film and television industry, in her hybrid photographic practice.

In the 1980s, Malaysian artist and art historian, Redza Piyadasa (1939–2007) used photo collage to explore different notions of ethnicity in Malaysia in his series Mamak family (1981) and Muslim family (1983). Yee's subsequent works purposely problematised Piyadasa's quest in unpacking ideas of ‘the authentic, the indigenous and the pure’ in historical and contemporary debates around Malaysian nationality and identity.Footnote 41 Yee's hybrid photo-based practice revolves more systematically around notions of gender, colonial repression, territorialism, nationhood, historical memory, global and local economies, migration and multiculturalism, social and personal (hi)stories, referencing and/or appropriating material from archives and mainstream culture, as well as everyday objects. Yee considers ideas of shared imagined communities and sociopolitical histories in the Southeast Asian region and the individual's place in this imaginary as in the series Malaysianna and Through rose-coloured glasses (2002), for which she used the archives of the Pakard Photo Studio, which produced commercial portraits for the migrant communities in Melaka since 1959. ‘Is there a collective imaginary narrative for Southeast Asia?’, asked her series Sulu stories (2005). Using the fluidity of the digital image, perhaps as a comment on the ‘seeming constructedness of modern Malaysia’,Footnote 42 these multi-layered, paradoxical tableaux re-imagine histories of migration, trading and the impact of colonial rule against the ethnic territorial narratives of Malaysia and the Philippines. Beverly Yong describes these imaginative topoi as Yee's fluid world ‘in which the act of self-imagination, self-mapping, and of empathy, is more crucial than ever’.Footnote 43

Towards similar ends, Yee repurposed John H. Lamprey's anthropometric photographs of a Malayan male (1868–69). As assistant secretary of the Ethnological Society of London and Librarian of the Royal Geographic Society, Lamprey used an ‘anthropometric’ system to study the anatomical characteristics of racial types. Subjects were to be photographed in frontal and profile positions in full nudity against a dark wooden backdrop featuring a lattice made of two-inch squares marked by silk threads. Reminiscent of the metrological grid systems used by artists in the depiction of the human body, this practice would allow ‘the study of all those peculiarities of contour which are so distinctly observable in each group […] which no verbal description can convey, and but few artists could delineate’.Footnote 44

Consisting of two diptychs based on Lamprey's original photograph now kept in the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain, Yee's work Study of Lamprey's Malayan male I & II (2009) uses appropriation, manipulation and performance to redirect the gaze of the colonised to the coloniser and challenge the power balance between them (fig. 6). In the first diptych, Yee gently manipulates the man's posture so that he stands straight and gazes back at the camera operator/viewer; his fist is clenched as if he is talking back. In the second diptych, the man has exited the frame leaving his white silhouette to visually converse with the artist who enters the image, but stands assertively outside the gridded photo-booth, refusing to be objectified. Yee challenges the authority of the colonial gaze from the position of an empowered Malaysian woman seeking justice.Footnote 45 The artist asserted that the presence of the naked ethnic identity of the Malayan male through his absence in our own time is most pertinent at a time when Malaysian society ‘is particularly obsessed with framing, measuring, indexing identities and subjugating its populace to notions of racial supremacy and otherness’.Footnote 46

Figure 6. Yee I-Lann, Study of Lamprey's Malayan male I & II (detail), 2009.

Whilst Wasiksiri's photomontages operate within the convention of photographic framing and perspective, Yee adopted a distinctively speculative spatial approach in her series Picturing power (2013). Against an elongated neutral picture plane, Yee re/decontextualised figures and imagery from photographs in Dutch colonial archives. In the picture ‘Wherein one cultivates cultural codes, the noble endeavours of mankind and thereby put it in its place’, she straightened the rigid and ordered sugar cane plantation as a bold horizontal line (fig. 7; background detail in fig. 8). Here, like her earlier series Horizon (2003), the optical device of the horizon is employed as ‘a point of negotiation of what is possible or might be imagined’.Footnote 47 Yee stated with reference to the series Horizon, which she described in retrospect as her way of trying to gain some perspective on what was to happen in the post-Mahathir years in Malaysia:

I would use the photographs to surrender the horizon to the ‘hyper-real’; the image would become my accomplice. I would put a horizon back into our landscape and see what it would tell us. […] I would stitch fragments together, heal wounds, join the imaginary with the symbolic.Footnote 48

Figure 7. Yee I-Lann, ‘Wherein one cultivates cultural codes, the noble endeavours of mankind and thereby put it in its place’, from the series Picturing power, 2013.

Figure 8. Yee I-Lann, ‘Wherein one cultivates cultural codes, the noble endeavours of mankind and thereby put it in its place’, from the series Picturing power, 2013 (detail).

In the foreground of the image in fig. 7, Yee connects the long, wavy, black hair of two Javanese women, who are delousing each other. Loose, floating hair is a recurrent symbol of emancipation for the women in Yee's narratives, as for instance, in the work ‘Huminodun’ from the Kinabalu series (2007), in which the long wavy hair of a pregnant woman dominates the dramatic rural landscape. Yee marks a space with these two lines where she inserts Dutch and Javanese figures in different activities: a group of Javanese folk engaged in pottery making; a Dutch supervisor sitting on a horse in front of a squatting Javanese male; and another Dutch man overseeing a cow cart laden with harvested cane (fig. 8). Stripped bare of the context provided by their original photographic frame and their use value, a practice common in anthropological and colonial endeavours as exemplified in the Dammann albums in the late nineteenth century,Footnote 49 the artist exposes the incongruous nature of staging in these genre scenes.

Modern agriculture, symbolised by the horizontal line of the cane plantation, contrasts with the activities of the Javanese women, who appear to spend their working hours looking after each other's hair (fig. 7). In the playfully long title Yee casts aspersions on the colonisers’ ideology of progress by focusing on a local pre-industrial activity, and the ‘cultural code’ of colonial photographic practices. She isolates pictorial idioms formulated within the sugar industry in a nondescript empty space in order to highlight the artifice and ideological baggage of colonial iconography. Javanese women delousing, for example, are a popular theme present in various photographic albums produced in the Dutch East Indies.Footnote 50 The Dutch man on the horse and the squatting Javanese man in the field are quintessential depictions of colonial power relations to be found in many colonial photographs. The extended and connected hair of these two women and the off-kilter blue plastic stool are ironic visual responses to such pictorial clichés.

The emptiness of the white picture plane in this series creates a geographical and temporal void so the viewer is called to re-examine colonial relations and stereotypes surviving in a non-linear, non-chronological narrative: the portrayal of colonisers as agents of progress juxtaposed with the locals foregrounded in their non-economically-productive habits exposes the ideological flaws of colonialism and the ‘ambivalent and contradictory status of these photographs as colonial fantasies’.Footnote 51

In the picture ‘Wherein one tables an indexical record of data-turned-assets and rules like the boss you now say that you are’ (2013) the space is defined by the colonial symbols of progress and modernisation par excellence: the railway line that traverses the frame and the imposing factory whose tall chimneys punctuate the horizon line (fig. 9). In the right-hand corner of the foreground, Yee ‘unfixes’ the image of a Caucasian man in white Western attire, sitting at a desk in what looks like an office. The man is Pietermaat-Soesman, and the photograph was taken in his home study to be included along with other photographs of his household and employees in the album Souvenir from Purwokerto and Kalibagor. In the original photograph, the walls are adorned with framed photographs of pristine tropical landscapes, of rice fields and rivers as well as Pietermaat-Soesman's portrait at the Kalibagor sugar factory. Yee replaced two of these photographs with a land taxation photograph and a botanical photograph. In doing so she brought colonial administrative and scientific activities into the industrialist's domestic space. In the reworked scene in the background, local barefooted men appear to work an imaginary land, some hoeing, some sowing, others gazing at the emptiness, being constantly supervised. In both photographs (figs. 7/8 and 9), the presence of the colonial overseers brings to the fore issues of domination and control of indigenous people that extend to the present day.

Figure 9. Yee I-Lann, ‘Wherein one tables an indexical record of data-turned-assets and rules like the boss you now say that you are’, from the series Picturing power, 2013.

Yee often uses the table, associated with the desk of the supervisor at the factory site, to symbolise control and power. This takes many forms: from the architectural drawing board in ‘Wherein one, in the name of knowledge, measures everything, gives it a name and publicises this thereby claiming it’ (2013), to the tables carried by locals amongst covered cameras on tripods while Caucasian men in Western attire pose throughout the frame in ‘Wherein one surreptitiously performs reconnaissance to collect views and freeze points of view to be reflective of one's own kind’ (2013) (fig. 10). The darkening cloths over the cameras that dominate the frame in the latter work not only cloak the devices, making them appear mysterious or even threatening to those being surveyed, but they also mystify the mechanism of representation, the knowledge of which belongs to the Western photographer sitting at his desk on the right-hand corner of the frame.

Figure 10. Yee I-Lann, ‘Wherein one surreptitiously performs reconnaissance to collect views and freeze points of view to be reflective of one's own kind’, from the series Picturing power, 2013.

In Picturing power Yee uses distance and proximity, both physical and metaphorical, to point to the ways that distance from the ‘other’ was a pointer of cultural distinction in colonial photography. The seeming objectivity of the ethnographic record is contaminated by staging and reenactment while the attempt to approach the colonial ‘other’ is cancelled by the cultural distance imposed by the very process of othering.Footnote 52 The physical scale of the series accentuates the ideological conundrums of colonialism: the closer the viewer gets, the greater the cultural distance.

History hoaxes

Agan Harahap creates parodic invocations of colonial iconography, using visual and factual fragments of authentic information seamlessly integrated with fictional elements that may reveal the falsity of his constructed images.

Having trained as a painter and graphic designer in Bandung, West Java, Indonesian Harahap moved to Jakarta in 2008 to work as a digital imaging artist in one of the largest commercial photographic studios in the Indonesian capital. His technical mastery in digital manipulation combined with artistic urgency resulted in a series of work entitled Octopus garden (2008), which was shortlisted for the Indonesian Art Award and exhibited in the National Gallery in Jakarta that same year. Inspired by The Beatles’ 1969 song Octopus's garden, the series consists of three black-and-white photographs taken in a studio setting, whereby the surrealist nature of the song is visualised in tongue-in-cheek staging: an octopus-headed female figure poses as a fashion model accompanied by another octopus, a jumping rabbit and flying white birds.Footnote 53 Harahap's constructed imagery admittedly targeted both social documentary practice, which had long been a dominant genre in the Indonesian photographic scene drawing on postwar humanist iconography, and commercial (advertising and lifestyle) photography. The artist's seamless doctoring technique equally built on a long tradition of image manipulation, from Calvert Richard Jones’ photograph of four Capuchin Friars in Malta in 1846, whose paper negative revealed an erased fifth person, to Henry Peach Robinson's composite tableaux in the late nineteenth century and Jeff Wall's ‘near documentary’ photographs.Footnote 54 Harahap's impetus towards staging and manipulation was also part and parcel of an emerging direction in South and Southeast Asian creative photography at the turn of the millennium, as traced, for instance, in the studio work of Pushpamala N. (India) and Wawi Navarozza (the Philippines) or Michael Shaowanasai's self-portraits in drag (Thailand). Footnote 55

Harahap's numerous solo exhibitions and participation in group exhibitions, art fairs, biennials and photography festivals in Southeast Asia and beyond testify to the appeal of his unorthodox fusion of reality and artifice, whether subverting iconic historical photographs or parodying the illusionism of contemporary celebrity culture by ‘Indonesianising’ international celebrities and public figures.

In his series Superhistory (2010), Harahap appropriated well-known photographs of landmark moments in world history in which he digitally integrated superheroes (fig. 11). If his seamless digital collages perplex the viewer seeing Spiderman taking active part in the invasion of Normandy, Darth Vader shadowing Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin at the Yalta Conference in 1945, or Superman overseeing the removal of artworks from Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria the same year, it is not to satirise or caricature history. In fact, the artist claims, he ‘loves history’.Footnote 56 Inspired not by comics but two popular video games amongst Indonesian youths, ‘Call of Duty’ and ‘Medal of Honour’, which draw on Second World War battles, Harahap uses references to past and present popular culture to comment upon the reinterpretation and commercialisation of history, asking ‘what if’.Footnote 57 Beyond the comic effect of the images that went viral as soon as they appeared on the artist's Flickr page, Harahap's hoaxes primarily point to the photograph's power to manipulate truth. The selection of historical photographs also reminds us that even before the advent of digital software retouching and re-enactment were skilfully used to change history. For instance, Stalin, Mao Tse-tung and Hitler had their enemies and those falling out of favour airbrushed from photographs whilst a second watch was notoriously removed from the hand of the soldier who raised the flag of the Soviet Union over the German Reichstag building in Yevgeny Khaldei's photograph, to conceal looting.

Figure 11. Agan Harahap, untitled, from the series Superhistory, 2010.

It was in the context of the abovementioned workshop in Yogyakarta that Harahap was introduced to archival colonial material from the Dutch East Indies for the first time, an encounter that informed the creation of a fictional colonial Mardijker Photo Studio a year later.Footnote 58 ‘Mardijker’, derived from the Sanskrit Mahardika (‘Liberated’), was the term used to describe the baptised former slaves and their descendants in Batavia (colonial Jakarta) who, working for the Portuguese, converted to Catholicism and subsequently to Protestantism under Dutch rule.Footnote 59 These populations embraced Western culture and religion, but their skin colour prohibited them from accessing a higher social status in colonial society. Harahap wittingly addresses this ‘in-between’ social identity in his fictional studio's ‘specialisation’, that is, inter-mixed portraits of Europeans and locals. In the same subversive spirit of questioning the authority of historical photographs, Harahap contests visual and cultural commonplaces in colonial studio portraiture, using digital manipulation to idealise socially conditioned stereotypical motifs in the representation of Europeans and locals alike.

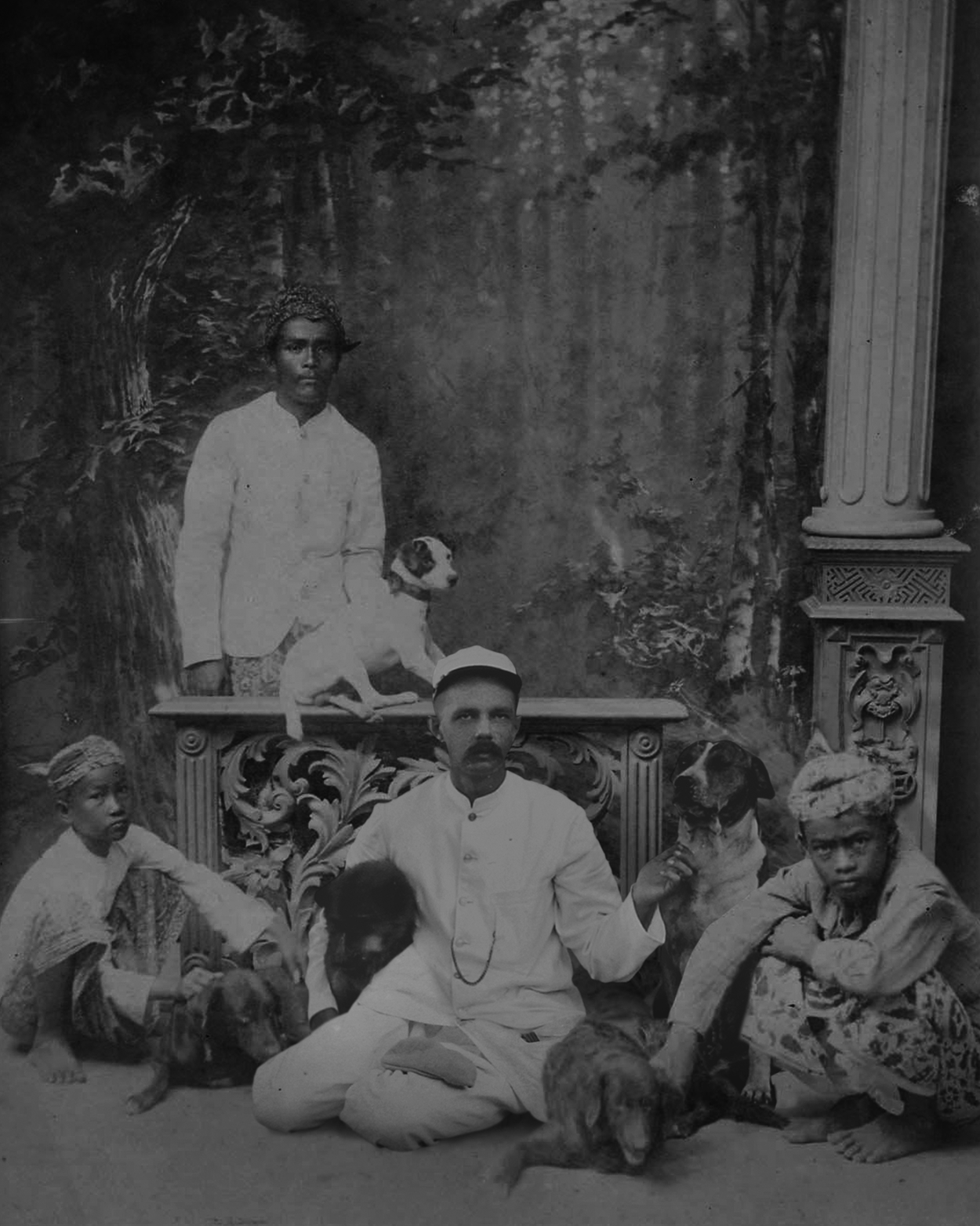

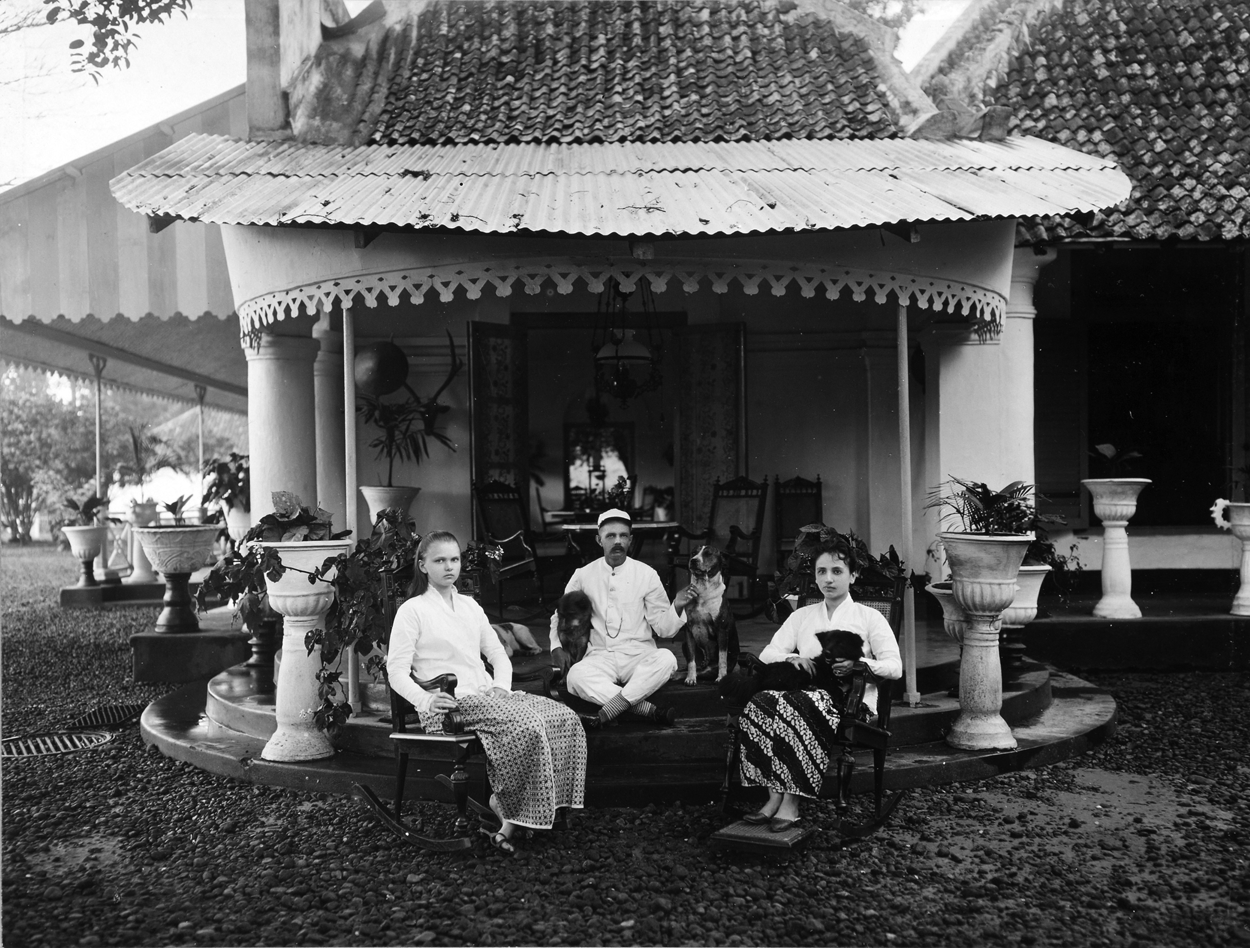

In the studio portrait in fig. 12, Harahap appropriates the in-situ portrait of the sugar factory director Jan Antoine Pietermaat-Soesman sitting cross-legged like a Javanese man holding his dogs at the porch of the family house in Kalibagor. This photograph is in Souvenir from Kalibagor, which, like other family albums of sugar industrialists in the Dutch East Indies, attests to the gradual disappearance of studio portraits in favour of outdoor portraits for the colonial elite. Mostly taken in their houses, these group portraits included numerous household members: family guests, friends, local helpers and family dogs that otherwise would be excluded in studio portraits.Footnote 60 The regular presence of dogs in those family albums (often with their names inscribed in the accompanying captions) indicates a particular social attitude toward animals as family pets, which often confused local helpers.Footnote 61 Harahap accompanied the image ‘Dog whisperer van Kalibagor’ with a short background story that explained how Jan Pietermaat-Soesman, who had been attacked by dogs when he was six years old, became a dog whisperer, contextualised with factual biographical information.

Figure 12. Agan Harahap, ‘Dog whisperer van Kalibagor’, from the series Mardijker Photo Studio, 2015.

In his reworking of the original photograph, Harahap reinstates the studio portrait in the Pietermaat-Soesman family chronicle, whereby the sugar factory's general manager poses with five dogs and three Javanese men in formal attire. By interchanging native and Western poses, the artist tries to destabilise, visually and culturally, the identity of the sitters and blur the boundaries between racial and social hierarchies. In the original photograph (fig. 13), Jan Pietermaat-Soesman assumes the patriarch's position, being placed at the compositional apex of a triangle with two women on either side. Harahap mocks this gendered logic by retaining Jan Pietermaat-Soesman in the compositional centre surrounded by dogs but modifying his sitting posture: instead of cross-legged, he now sits in the manner of Javanese women. In the studio photograph, the three Javanese men are presented confidently staring back at the camera as assistants to the high-profile industrialist, who, in a reversal of roles, is a dog whisperer. Once again, Harahap drew inspiration from the popularity of a local TV series on canine-behaviourists as owning a pet dog and employing a professional for its training is a symbol of social status in contemporary Indonesia. As such, Jan Pietermaat-Soesman's reworked portrait provides a critical link between colonial and postcolonial Indonesia, and the ways in which certain social hegemonies remain the same.

Figure 13. Unknown, ‘In the rotunda of the General Manager's house, Mr. and Mrs. Pietermaat and Ms. Mulder, a lodger’, c.1905, from the album ‘Souvenir from Poerwokerto and Kalibagor’, ALB-256, p. 5, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Coll. No. 60004317.

Whilst European families preferred in-situ group portraits to illustrate their domestic life, studio portraits of local subjects were primarily the projection of European curiosity, whether in the form of scientific inquiry, administrative necessity or for the mere purposes of one's personal collection.Footnote 62 Appadurai has argued that the colonial photo studio was equally the site for locals to ‘experiment with modernity’ and ‘documentary realism’ as the studio portraits of indigenous people were both ‘types’ and ‘tokens’.Footnote 63 Harahap addresses this ambivalent status of colonial studio portraits in ‘Sutirah: The first woman animal tamer’ (hereafter ‘Animal tamer’) (fig. 14).

Figure 14. Agan Harahap, ‘Sutirah: The first woman animal tamer ca. 1885, West Java’, from the series Mardijker Photo Studio, 2015.

In this composite portrait Harahap caricatures the colonial representation of the exotic woman and the exotic animal from the tropics. Sutirah is depicted in a Western-style white dress with her long black hair flowing down her chest, comfortably holding a crocodile as a pet, a clin d'oeil to the Europeans being photographed with their pet dogs. Staring back at the camera fearlessly holding the reptile, Sutirah's portrait does not conform to the usual colonial studio portraits of local women. Whilst in ‘Dog whisperer’ Harahap referenced modern pet culture in Indonesia, ‘Animal tamer’ draws upon myths about female figures with supernatural powers found in local folklore. In this light, both portraits operate within the same logic of merging tradition and modernity, the oriental and the occidental, index and icon, type and token.

Here, too, Harahap accompanied the portrait of Sutirah with fictional and factual information, providing along with his fictional heroine's invented date of birth and information about her talent for communicating with animals, reference to her collaboration with a real historical figure, the German-Dutch zoologist Carl Wilhelm Weber (1852–1937), who went on a scientific expedition to Sumatra in 1899. Unlike the generic captions of ‘type’ portraits that served to typecast anonymised individual subjects (e.g., ‘Javanese woman’, ‘Chinese blacksmith’, ‘Balinese dancer’), thus allowing for their commodification as ‘tokens’, the caption ‘Animal tamer’ is unique in offering a rich cultural context for the named individual.

Harahap has posted portraits from the Mardijker Photo Studio regularly on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter under the name of Sejarah_X (History_X). By using social media to discuss and further disseminate his pseudo-archival material, Harahap seeks to engage with audiences on a national, regional and international scale in order to reinvigorate discussions about colonialism. At the time of writing (May 2020), Sejarah_X had almost 30,000 Instagram followers, over 7,500 Twitter followers and approximately 1,700 Facebook followers. This interaction with diverse audiences online reveals different levels of knowledge of colonial history and consciousness about the truth value and authority of photographic representations among users. For instance, discussion threads for the Sutirah post range from questions of curiosity such as, ‘Is the crocodile her pet? It looks like one?’, to comments about the artifice of the portraits and the need to know one's own national history (fig. 15).

Figure 15. Screenshot of Agan Harahap's Sejarah_X Instagram page for ‘Sutirah’, 26 June 2017.

Capitalising on the momentum of social media in Southeast Asia, Harahap uses these new forms of sociality and personal revelation that enable users to untangle the mechanics of colonial archivisation, and the ways material is preserved and narrativised. By dematerialising his images for dissemination and using the possibilities of repurposing and public participation that Web 3.0 offers, Harahap interrupts the authority and integrity of the colonial archive, asking viewers to think twice about what it is that they see. He offers online users the opportunity to scrutinise, disseminate, exchange, manipulate and repurpose this material, an active process of civil engagement that requires awareness of colonial and postcolonial histories and may have a transformative impact on their own sense of identity and postcolonial ‘relational self’.Footnote 64 His work suggests that the postcolonial archive is modular and fluid and that is not just about material objects; it consists of all those behaviours that develop around such relationships and exchanges, online and offline.

As Deirdre McKay argues in regard to the increasing dissemination of historical images on Facebook in Southeast Asia, ‘it is not surprising that we find that the anxieties and insecurities of a digital and diasporic age are being assuaged by […] importing the past through historical images’.Footnote 65 The value of these images, she continues, ‘arises both from the image itself and its grouping, collection, juxtapositions and the possibilities of citing past images, variation, modification and future connections to make new norms for persons and their relations’.Footnote 66 Thus initiatives like Sejarah_X become fora to discuss historical cultural and ethnic clichés—with a view to opening a democratic public debate towards a shared/collective interpretation of local history in Southeast Asia that surpasses the law of the ‘arche’ of the archive. Harahap's Sejarah_X offers an alternative postcolonial archive in which notions of ownership, agency and authority are to be redefined collectively and individually.

None of the three artists discussed above had access to the original archival records they appropriated during and after the (Post)colonial Photography Workshop in 2012. They worked solely with the digital proxies made available in high resolution files by the archives in the Netherlands. They thus capitalised on the modularity, immateriality and versatility of the digital image to repurpose and alter colonial archival imagery. By doing so, they not only contest and reconfigure the use and truth value of colonial records: Wasiksiri's exaggerated re-enactments, Yee's decontextualised archival fragments, and Harahap's seamless visual hoaxes attest to the manipulability of archival records, both during their making and their process of archivisation. At the same time, they also call into question and reclaim the ownership of the colonial archive. Thai Wasiksiri and Malaysian Yee used photographic material from Dutch colonial archives to paint the bigger picture of colonialism in Southeast Asia, informed by their understanding of the making of national and colonial histories. Not surprisingly, Indonesian Harahap avoided the grand narratives of colonialism, the colonial gaze, race and power relations, to concentrate on the periphery of the cultural logic of colonialism by focusing on the everyday and the vernacular of colonial society in the Dutch East Indies. Disseminated beyond physical and geographical borders and remixed online, this work becomes part and parcel of an expanded postcolonial archive that moves from archiving the past to re-imag(in)ing a postcolonial future.