Introduction

Research on the social investment state has increased in salience over the past two decades (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck and Hemerijk2017). We add to this burgeoning area of research by focusing specifically on early childhood education and care (ECEC) – ‘childcare’, ‘nursery education’ or other ‘pre-school’ provision for young children – which is seen as integral to the social investment state (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, de la Porte, Garritzmann and Pavolini2018; Lister, Reference Lister2003; Naumann, Reference Naumann2014). The provision of high quality childcare is expected to increase employment rates by allowing parents to engage in paid employment, and to benefit the cognitive and non-cognitive development of young children. Jenson (Reference Jenson, Bonoli and Natali2012: 23) has formulated social investment as a ‘package of policy design that is child-centred as well as employment friendly, and focused on investments in human capital’. ECEC is seen as a key element of the package, given its potential to improve children’s later educational attainment (e.g. Heckman, Reference Heckman2006; Sylva et al., Reference Sylva, Melhuish, Sammons, Siraj and Taggart2014; Thévenon, Reference Thévenon, Rindfuss and Choe2016), their literacy and numeracy scores (Filatriau et al., Reference Filatriau, Fougère and Tô2013; OECD, 2016a), and to make learning outcomes more equitable (Dumas and Lefranc, Reference Dumas and Lefranc2010; Esping-Andersen et al., Reference Esping-Andersen, Garfinkel, Han, Magnuson, Wagner and Waldfogel2012). By facilitating maternal employment, it has the potential to reduce child poverty and to enhance work-life balance (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck and Hemerijk2017; Lewis, Reference Lewis2009). However, in order to serve these functions ECEC must be affordable and high-quality, especially for disadvantaged children (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck and Myles2002).

ECEC has also had a high profile at the European level. The European Commission (EC) has recommended that it is viewed as ‘a social investment to address inequality and challenges faced by disadvantaged children’ (EC, 2013: para 2.2). It has stressed the importance of providing access to high quality, affordable ECEC, of curricular frameworks, staff competences (EC, 2011; 2013) and the need to ‘incentivise the participation of children from disadvantaged backgrounds (especially those below the age of three years) regardless of their parents’ labour market situation’ (EC, 2013: para 2.2).

Social investment is generally measured using public expenditure (e.g. Van Lancker, Reference Van Lancker2018). However, we argue that effective social investment in ECEC is dependent on meeting three conditions: availability, affordability and quality of provision. This raises the question of how best to construe these notions. Availability is generally understood in terms of participation in ECEC (EC, 2018), albeit that it fails to acknowledge logistical challenges to accessing childcare services (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Naumann and Koslowski2017). Affordability can be construed in terms of costs to parents (EC, 2018); this is associated not only with the extent of public financial support to subsidise the costs of ECEC but also the type of financial support: in particular, direct public funding of provision or funding parents directly (OECD, 2016b).

Staff qualifications are of fundamental importance as regards quality: there is a positive association between teacher qualifications and the quality of the early childhood learning environment. Furthermore, low child-to-staff ratios are associated with greater academic progress (Manning et al., Reference Manning, Garvis, Fleming and Wong2017). A common curriculum can play a crucial role in ensuring the quality of ECEC services and ensure more consistency within jurisdictions (OECD, 2015). Quality in turn depends on regulation, which can include mandates relating to staffing, the curriculum and inspection (cf. McLean, Reference McLean2014).

Achieving availability, affordability and quality in ECEC is dependent on central, regional and local government. In most European countries there is devolution of power and some form of decentralisation of authority and resources (Rodriguez-Pose and Gill, Reference Rodriguez-Pose and Gill2003). Where local government has the main responsibility for the provision and/or funding of ECEC, central government may require localities to meet certain costs out of their own resources and seek to prescribe how functions should be provided, e.g. staff ratios (Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith2002). It may also allow some autonomy in terms of functions provided – thus, the responsible authority may choose to prioritise (or not) the provision of ECEC, so affecting availability.

In privatised, market-based systems, under the control of central or regional government, where public funding follows the child, this may not be sufficient to ensure an adequate supply response in less profitable markets, so reducing availability and accessibility (Warner and Gradus, Reference Warner and Gradus2011). The quality of provision can also be hampered in market-based systems as a result of the type of public investments – direct public funding of provision or funding parents directly – the structure of subsidies to public and private providers, and ‘government reliance on private providers without strong regulatory regimes capable of ensuring high quality services’ (White and Friendly, Reference White and Friendly2012: 293). Market-based systems may also create the ‘potential for public funds to be leveraged for the purposes of private profit and gain rather than for the direct benefit of children and families’ (Adamson and Brennan, Reference Adamson and Brennan2014: 50). Indeed, concerns have been raised about the ability of private providers to deliver universal, high quality ECEC because of the inadequate regulatory regime (West et al., Reference West, Roberts and Noden2010).

In this paper we focus on social investment in ECEC in three European countries, England, France and Germany, which differ along various dimensions. In France, public expenditure on ECEC is high and has not changed significantly over the past two decades: it was 1.29% of GDP in 1998 and 1.27% in 2013. In both Germany and the UK, public expenditure has increased over the same period – from 0.39% to 0.58% in Germany and from 0.53% to 0.76% in the UK (OECD, 2016c). Turning to governance, France is a unitary state, Germany a federal state, and the UK a quasi-federal state (with England a constituent country). In federal systems, the local level is very much the responsibility of the regional level, whilst in unitary systems the centre has considerable ability to ‘change the rules of the intergovernmental game’; this is also the case in England where ‘local government’s place in the scheme of things is determined only by legislation and its interpretation’ (Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith2002: 92).

Whilst the level of public expenditure (which has long been high in France and has risen in England and Germany) is generally regarded as being key to social investment, it is also true that central, regional and local government are important – not only with regard to the amount of funding available but also the characteristics of that funding; the type of the provision; the allocation of funding to providers/parents (important for availability and affordability); and how provision is regulated (important for quality).

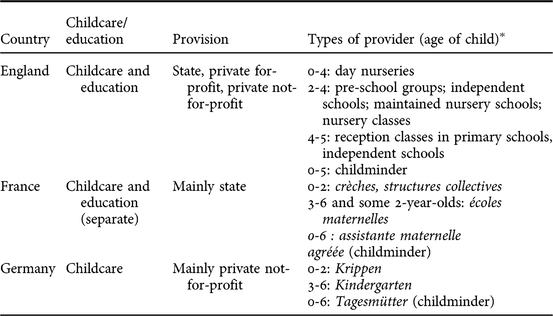

ECEC in the three countries also varies in terms of the longevity of the systems, the nature of the provision (public, private-for-profit/not-for-profit) and the systems in place (see Table 1). In France, there are separate systems of childcare and education. In Germany, there is a system of childcare prior to compulsory school, with kindergarten being classified as ‘care’ (Erziehung/Betreuung) not education. In England, the differentiation between care and education is blurred: The Childcare Act 2006 defines ‘childcare’ as any form of care for a young child including (a) education and (b) any other supervised activity. The countries thus have different systems in terms of the age of children served; the ‘care’ and ‘education’ balance; the nature of the provider; and the role played by the central state.

Table 1. Characteristics of ECEC and type of provision in England, France and Germany

* Compulsory school begins at 6 in France (until September 2019) and Germany, and the term after children reach 5 in England (but children normally start school in year in which they become 5 and enter reception class).

We seek to address four questions: what role is played by central, regional and local government in the provision, public funding and regulation of ECEC; what are the characteristics of public investment in ECEC; how do availability, affordability and quality compare between the three countries; under what conditions do public funding and regulation of ECEC lead to effective social investment? We argue that social investment can be deemed to be effective where levels of participation (an indicator of availability) are high for particular age groups; where costs take account of parents’ ability to pay if there are any fees (an indicator of affordability); and where staff are highly trained (a crucial indicator of quality).

In the next section, we provide an overview of policy development of ECEC in each country and the role of different levels of government in the provision, public funding and regulation of ECEC. We provide ‘thick’ descriptions (cf. Ryle, Reference Ryle1949) to uncover underlying complexities using government, parliamentary and official documents and statistics from individual countries together with secondary literature. In the case of Germany, because of large regional variation between Länder, we exemplify with reference to the city state of Berlin. We then analyse social investment in ECEC in terms of the availability, affordability and quality of provision. The final section analyses the relationship at a country level between policy, provision, funding and regulation on the one hand, and the availability, affordability and quality of ECEC on the other; it then compares countries in terms of the extent to which social investment can be deemed to be effective, and discusses the limitations of the concept.

Policy, provision, funding and regulation

England

Policy development

Historically, the UK has had a strong attachment to the male breadwinner model and to supporting women primarily as wives (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). This changed in the 1980s-1990s when the ‘male breadwinner/female part-time carer model’ became the ‘dominant cultural image’ (Pfau-Effinger, Reference Pfau-Effinger2005: 331). However, it was not until 1998 that a national policy of early years education and care was introduced. Up until that point, local authorities decided whether or not to provide nursery schools and nursery classes – those that did were predominantly in areas with a high percentage of women in the labour market. Local authorities also provided childcare in day nurseries – mainly for children deemed to be ‘in need’. Private for-profit and not-for-profit (voluntary) provision developed alongside state provision (Owen and Moss, Reference Owen and Moss1989; West and Noden, Reference West and Noden2019). In 1996, the Conservative government introduced a nursery education voucher scheme for four-year-olds; the voucher could be used for a part-time place, 33 weeks a year in either a maintained (local authority-funded) school or a private for-profit or not-for-profit childcare centre. In 1998, the Labour government (1997-2010) replaced the voucher with an entitlement to free part-time early education (West and Noden, Reference West and Noden2019) and also launched the National Childcare Strategy with the aim of raising quality and making childcare more affordable and accessible (DfEE, 1998; Daly, Reference Daly2012; Lister, Reference Lister2003). The main policy goals since 1998 have been oriented towards women’s work and increasing availability of provision on the one hand, and child development on the other, with the priority given to each varying over time (HL Select Committee on Affordable Childcare, 2015; Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2017).

Labour governments progressively extended the free part-time entitlement in EnglandFootnote 1 to three-year-olds and to 38 weeks a year; childminders also became eligible for government funding (Lewis and West, Reference Lewis and West2017). The Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government (2010-15) increased the entitlement further – to 15 hours a week and to the 40% most disadvantaged two-year-olds. As a result, expenditure increased by almost 40% between 2010–11 and 2014–15 (Sibieta, Reference Sibieta2015). In September 2017, the Conservative government (2015–) introduced an ‘extended entitlement’ of 15 hours a week free ‘childcare’ (i.e. 30 hours in total) for three- and four-year-olds with parents in work and earning at least the national minimum/living wage for 16 hours a week on average (DfE, 2018a).Footnote 2

Provision, funding and regulation

In England, the market, facilitated by central government, plays a pre-eminent role in the provision of publicly-funded ECEC. Local authorities have a duty under the Childcare Act 2006 to secure ‘prescribed early years provision free of charge’ (s7) and play the lead role in facilitating the ‘childcare market’. There is a mixed economy of private for-profit and not-for-profit providers and maintained nursery and primary schools (see Table 1). Although the mix varies between local authorities, there is a trend towards intensive marketisation and significant involvement of private corporate providers (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan, Cass, Himmelweit and Szebehely2012; Lloyd and Penn, Reference Lloyd and Penn2014; Naumann, Reference Naumann2011). In 2018, the majority of three-year-olds (65%) and disadvantaged two-year-olds (87%) benefiting from the ‘universal entitlement’ (15 hours) attended private (for-profit/not-for-profit) providers (including childminders), whilst the remainder attended maintained nursery classes/schools. Most four-year-olds (78%) on the other hand attended reception classes in maintained primary schools. The majority of those taking up the ‘extended entitlement’ attended private providers (DfE, 2018b).

Funding is controlled by central government, which distributes funds to local authorities for free early years provision. In 2017, an early years national funding formula was introduced (West and Noden, Reference West and Noden2019). This sets the hourly funding rates that each local authority is paid by central government to deliver the universal free entitlement (15 hours) and the ‘extended entitlement’ (15 hours for working parents) for three- and four-year-olds, together with the rate for disadvantaged two-year-olds. Local authorities are required by central government to fund any provider registered by the national inspection body, Ofsted (DfE, 2018c). They must allocate funds for three- and four-year-olds using a formula with a universal base rate for all providers and are allowed to add supplements of up to 10% including a mandatory supplement for deprivation (West and Noden, Reference West and Noden2019). Since 2015, an early years ‘pupil premium’ has been payable to providers for three- and four-year-olds from low income families (DfE, 2018d; West, Reference West2015). Funding is thus designed to provide a level playing field in the ECEC market for public and private (for-profit/not-for-profit) providers.

Central government makes limited funding available to support local authorities with capital costs. In 2016, £100m was awarded to enable nearly 400 providers to deliver ‘30 hours’ places (ESFA, 2017) but this required 25% co-funding, and central government cuts to local authority funding militated against this (e.g. Hounslow, 2017). In addition, capital funding of around £30m has been allocated to create new school-based nursery places, with the aim being to allocate funding to the most disadvantaged areas (DfE, 2018e).

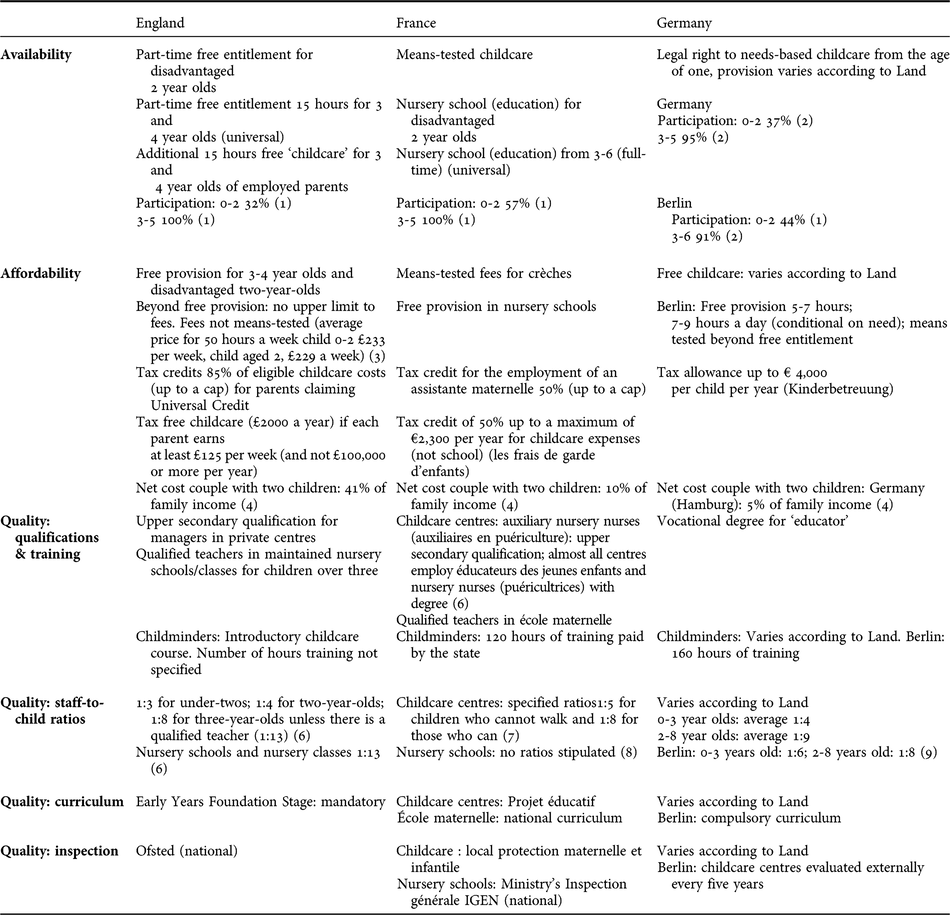

Beyond the government-funded free early years provision, fees for ECEC are determined by the provider. There is no maximum amount that a provider can charge and no means-testing, although parents on low incomes or in education/training can claim tax credits to assist with fees, and those on higher incomes can claim a government contribution to fees (see Table 2).

Table 2. Conditions for social investment in ECEC: Availability, affordability and quality

Notes: (1) OECD 2016c (2016 data) (2) Statistisches Bundesamt 2018a (3) Harding and Cottell Reference Harding and Cottell2018 (4) Net costs for a couple, for full-time care with two children one aged two and one aged three, at a typical childcare centre, as a percentage of family net income (2012) OECD, 2016c (5) EC/EACEA/Eurydice/Eurostat 2014 (6) DfE 2017 (7) Cnaf 2017 (8) IGEN and IGAENR, 2011 (9) Statistisches Bundesamt 2018b

Turning to regulation of ECEC, central government sets the rules for staff qualifications, ratios, the curriculum and inspection. In maintained nursery schools and nursery classes in primary schools a qualified school teacher must be employed. However, for other childcare centres – private for-profit/not-for-profit – the manager only needs to hold an appropriate upper secondary education level qualification (DfE, 2017). Childminders do not need formal qualifications, but are required to undertake limited training (see Table 2).

France

Policy development

French family policy is one of the oldest and most extensive in Europe (Martin, Reference Martin2010), characterised by stability and consensus (Thévenon, Reference Thévenon, Rindfuss and Choe2016), and family policies that have historically supported women as mothers and workers (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). There is a clear separation between childcare and early years education. The latter is longstanding with the école maternelle (nursery school), established toward the end of the 19th century (Norvez, Reference Norvez1990), having as its main goal child development via instruction, albeit that it ‘fuses’ education and childcare functions (Morgan, Reference Morgan2002: 115). Participation of two- to five-year-olds increased from 40% in 1950 to 70% in 1970 (IGEN/IGAENR, 2011). The childcare system, which expanded in the 1970s, followed the principle of universalism; the main policy goal since the mid-1980s has been the promotion of libre choix (free choice) in terms of work/family balance and female employment (Martin, Reference Martin2010). The dominant cultural model is that of ‘dual breadwinner/external childcare’, with childcare essentially the responsibility of institutions outside of the family (Pfau-Effinger, Reference Pfau-Effinger2005).

Since 2000, the government has increased expenditure on childcare centres (Fagnani, Reference Fagnani2012), with eight crèche expansion plans having been introduced by Conservative and Socialist governments (Caisse nationale des allocations familiales [Cnaf], 2017). The Socialist government (2013-17) aimed to create 275,000 additional places for children under three (100,000 in childcare centres, 100,000 with childminders, and 75,000 for two-year-olds in nursery schools); these targets were not in fact met for reasons that included a reduction in local government funding (Journal officiel (JO) Sénat, 2018).

Legislation enacted in 2013 prioritised the education of two-year-olds in écoles maternelles in disadvantaged areas and, in 2015, education priority policy was reformed with the introduction of priority networks (réseau d’éducation prioritaire (REP) and REP+) focusing on disadvantaged areas: a key measure was to increase participation of two-year-olds in écoles maternelles in these areas (to 30% and 50% respectively) (Cnaf, 2017). Under the Macron government 30,000 places in crèches are to be created and a ‘social mix bonus’ (bonus mixité sociale) is to be introduced with additional financial support provided to crèches accepting disadvantaged children. With effect from September 2019, the age at which compulsory education begins is to be reduced from six to three (Le Monde, 2018).

Provision, funding and regulation

Central and local government both contribute towards the costs of childcare facilities and écoles maternelles (Cnaf, 2017). The national Ministry has overall responsibility for the école maternelle, whilst the provision of childcare centres is decentralised to local authorities (communes), which, significantly, are not obliged to provide childcare facilities (Martin and Le Bihan, Reference Martin, Le Bihan, Scheiwe and Willekens2009). Unlike England, the majority of childcare centres are run by local authorities – only around 15% of crèche places (France Inter, 2018) are run by private organisations, with most having contracts with the Caisse d’allocations familiales (Satara-Bartko, Reference Satara-Bartko2018).

The capital funding made available by central government for the expansion of childcare centres is generous compared with England. The multiannual investment plan in place in 2017 for the development of crèches was for €850m. Each new place could benefit from a one-off central government subsidy, capped at 80% of the costs up to specified amounts, which were greater for communes with few childcare centres or low resource levels. To prevent childcare centres closing, subsidies for capital work (€19m per year) were also made available for providers (public and private) in receipt of public funding. In 2015, a fund was also introduced to support target groups (e.g. children with disabilities, living in poverty, rural and heavily urbanised areas) (Cnaf, 2017; JO Sénat, 2018). Further, the Macron government has announced that central government will subsidise up to 90% of the opening costs of crèches in priority areas (Le Monde, 2018).

In contrast to England, there is generous public funding to support parents. The principle of ‘double’ libre-choix gives parents the choice to care for their young child themselvesFootnote 3 or use extra-familial care. Another choice is between very diverse forms of care (Thévenon, Reference Thévenon2011), including collective and individual care. Indeed, the Complément de libre choix du mode de garde - Assistante maternelle contributes 85% of the costs toward employing a childminder (Service-Public.fr, 2018). The costs of a place in a collective childcare centre are subsidised by the state, with fees for collective childcare centres being set nationally (Fagnani, Reference Fagnani2012) on the basis of parents’ taxable income and family composition.

Turning to the regulatory framework, this is determined by central government and differs between école maternelles and crèches as regards staffing, the curriculum and inspection (see Table 2). For public and private crèches (Satara-Bartko, Reference Satara-Bartko2018) the overall framework is the same, but there is no common curriculum across the country. This is in contrast to the école maternelle, under the direct control of the Ministry, where there is a mandatory national curriculum and qualified teachers must be employed (with an agent territorial de service des écoles maternelles at certain times of day; Cnaf, 2017). Childminders do not need particular qualifications but must undertake specified training, which is more extensive than in England (see Table 2).

Germany

Policy development

In Germany, there are differences between childcare provision in Eastern and Western Germany reflecting different policies and norms prior to reunification in 1990. In Eastern Germany, under the Communist regime of the German Democratic Republic, childcare was well-developed, with the dominant cultural model being that of ‘dual breadwinner/state carer’; whilst in the Federal Republic of Germany, it was that of the ‘female as housewife and the male as breadwinner’ (Pfau-Effinger and Smidt, Reference Pfau-Effinger and Smidt2011: 222). Thus, in 1994 coverage rates for children up to three ranged from 54% in Brandenburg (Eastern Land) to 1% in Rheinland-Pfalz (Western Land) (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2004). Following German reunification, the offer of a place in a kindergarten for all children between three and six was accepted as a precondition for more liberal abortion laws (Kommers, Reference Kommers1994). Since then, the main policy goals have been oriented towards increasing women’s work, via increasing availability, facilitating the reconciliation of family and paid work for parents, and encouraging higher birth rates (Rüling, Reference Rüling2010; Blome, Reference Blome2017).

In 1996, a legal right to a childcare place was introduced; however, the number of hours was not specified. In 2002 the Social Democratic (SPD)-Green Coalition promoted the expansion of childcare. The government pledged grants of €8.5m between 2002-7 for federal states and local authorities (Bönker and Wollmann, Reference Bönker, Wollmann, Hoffmann-Martinot and Wollmann2006). The 2004 Day Care Expansion Act (Tagesbetreuungsausbaugesetz, TAG) required local authorities to provide enough places for children below three to meet demand, or as a minimum to make places available for children with parents in employment/training. Subsequently, the Christian Democratic (CDU)-SPD Coalition, enacted the 2008 Child Support Law (Kinderförderungsgesetz, Kifög) which introduced the right to a childcare place for children over one year of age. Since 2013, every child between the age of one and six has had the legal right to a place in a daycare centre or with a childminder (Tagesmütter); however, the number of hours is not specified, and a full-time place is not guaranteed (Schober, Reference Schober and León2014; Blome, Reference Blome2018).

Provision, funding and regulation

In Germany, responsibility for childcare is decentralised to individual Länder, with each Land having its own legislation and administration. The federal government provides financial support for national initiatives, such as expanding childcare services for children under three. In line with the principle of subsidiarity, public authorities are only obliged to provide childcare if non-governmental agencies are not able to do so. Accordingly, the main providers are private not-for-profit bodies (Freie Träger der Jugendhilfe), comprising welfare organisations, the churches, and other associations: in both Eastern and Western Länder, they provide around 60% of childcare places. Private for-profit providers, which are not entitled to receive public subsidies (unlike England), cater for only 4% of under-threes and 2% of three-to six-year-olds (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2018a); there are no restrictions on the fees they charge.

Policies regarding the provision of ECEC vary between Länder. In the city state of Berlin – which we use as an illustrative case – the administration publishes a call for tenders when provision is needed. Subject to certain conditions being met, the provider receives an operating license and is then eligible to receive public subsidies. In Berlin, eligible parents receive a voucher (Kita-Gutschein)Footnote 4 that they give to the childcare institution or childminder of their choice; this entitles the institution to receive public funding for the child. The value of the voucher varies according to the child’s age and the number of hours of care. Additional funds are provided for children with special needs, with a foreign language background and from selected disadvantaged districts. Each provider receives funds according to the same formula. The Berlin Senate also offers subsidies to providers for capital work.

All Länder assist with the costs of childcare. In all Länder, a minimum of three years of childcare before school is provided free of charge (Bock-Famulla et al., Reference Bock-Famulla, Strunz and Löhle2017). The fees for additional time vary according to the municipality: there is usually a scale of fees determined on the basis of factors such as parents’ income, although fees may be waived where the costs for parents would be deemed to result in unreasonable hardship. In Berlin, free provision was available for four years before school from 2016, and five years before from 2017; beyond this, parents had to pay fees according to their income, the age of the child and the number of siblings. Since 2018, all children have had the right to free part-time care (5-7 hours per day). If parents need more than 7 hours a day, they are required to prove their need (e.g. employment, training, family situation, pedagogical or social needs); parents only pay for food (€23 per month).

Turning to regulation, whilst staff qualifications are agreed nationally, the regional government determines ratios, inspection and training for childminders (see Table 2). In Berlin, to obtain an operating license the provider has to ensure that all employees are professionally and personally competent: only qualified staff (sozialpädagogische Fachkräfte) can be hiredFootnote 5 and the child-to-staff ratio must be appropriate. The premises must be suitable and the pedagogical approach deemed appropriate and based on the Berliner Bildungsprogramm (Berlin Education Programme). All publicly-funded centres must ensure that the educational goals defined by law are met, and the provider must offer healthy food (Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Familie, 2016). Whilst it is obligatory to follow the curriculum in Berlin, some Länder merely provide guidance, e.g. Hamburg (Preissing, Reference Preissing2012).

Meeting the conditions for effective social investment?

The different policies, provision, characteristics of funding and regulation raise questions about the extent to which the three countries meet the conditions for effective social investment in ECEC. In this section, we thus compare the countries with regard to the availability (in terms of participation and places), affordability (in terms of costs to parents) and quality of ECEC.

Availability: participation and places

In all three countries, participation in ECEC for children between the ages of three and five was almost universal in 2016 (OECD, 2016c). However, for children under three it was significantly lower in all three countries (see Table 2), with variation between countries albeit for different reasons.

In England, there is no national or local planning for ECEC provision. The majority of places for children under three are provided by the market and paid for by parents – with the exception of free places for disadvantaged two-year-olds. In 2018, only 40% of under-threes participated in formal ECEC (22% in private childcare centres) (DfE, 2018f). Furthermore, reductions in government funding levels for three- and four-year-olds have led to 44% of providers receiving less funding in real-terms in 2017/18 than in 2013/14 (Ceeda, 2018); this is tied in with the introduction of the early years national funding formula. Significantly, providers in some of the most deprived local authorities in England have had their hourly government-funding rates cut by 10% or more. Indeed, the average number of childcare places available to children under five fell by more than 20% in the most deprived areas of England between 2013/14 and 2017/18, whilst the number in the least-deprived areas increased by a third. Providers in more deprived areas are not able to attract as many privately-funded children and thus rely more heavily on income from government-funded places than providers in more advantaged areas (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2018).

In France, participation in ECEC of children under three was 57% in 2016 (OECD, 2016c). There is limited availability of places in childcare centres, with rural areas being particularly poorly served (Villaume and Legendre, Reference Villaume and Legendre2014); there is also regional variation with more places being available in the Paris region and metropolitan areas in the south east than others (Borderies, Reference Borderies2016). Furthermore, if there are shortages of places in childcare centres, local authorities may give priority to children whose parents are in work, and particularly to those in professional occupations needing a full-time place (Collombet, Reference Collombet2018), so reducing access to more disadvantaged families. The role played by local government is thus of fundamental importance when considering the availability of places.

Although provision for children aged three to six is universally available via the école maternelle, a small proportion of two-year-olds also attend: participation reached 35% in 1999 but declined progressively to 11% in 2012 (IGEN, 2014) before increasing to 12% in 2016. However, there is variation between départements in the provision of places for two-year-olds. In some regions, participation reaches over one in five (Cnaf, 2017) – indeed, some départements have more places for children under three in écoles maternelles than in crèches (Borderies, Reference Borderies2016). Such variation is related inextricably with decentralisation to the local level. Furthermore, although two-year-olds from disadvantaged families should be prioritised for a place in the école maternelle, they may not be, and children from more advantaged backgrounds may instead be admitted (IGEN, 2014; Ben Ali, Reference Ben Ali2012).

In Germany, where only 37% of children under three participated in formal ECEC in 2016 (OECD, 2016c), there is insufficient provision to meet parental demand (BMFSFJ, 2015). There is also regional variation: in 2016, the gap between supply and demand for children under three was 13 percentage points across the country: it was much lower in the Eastern than Western Länder – 7 versus 14 percentage points. The highest gaps were in two Western Länder, the city state of Bremen and Rheinland-Pfalz (20 and 16 percentage points respectively) (Alt et al., Reference Alt, Gesell, Hubert, Hüsken, Kuhnke and Lippert2017). The reasons for this can be related to the role played by regional government (see Discussion).

Affordability: costs to parents

The affordability of ECEC varies between countries. In England, ECEC costs for parents of children under three are high (see Table 2) and related to both insufficient government funding and unregulated fees (West et al., Reference West, Roberts and Noden2010); the centrality of the market is crucially important. Furthermore, parents in receipt of one key benefit, universal credit, who are eligible for up to 85% of childcare costs (up to specified amounts), must pay for childcare up-front and claim reimbursement from the government; this can leave households waiting many weeks to be reimbursed (HC Work and Pensions Committee, 2018). In a similar vein, in France parents who employ an assistante maternelle (childminder) must spend large sums of money to receive partial remuneration for the salary costs and tax credits (Villaume and Legendre, Reference Villaume and Legendre2014). With regard to crèches, even though fees are means-tested, costs are high unless both parents are in work (Thévenon, Reference Thévenon, Rindfuss and Choe2016). In Germany, whilst provision is not normally free, there is often a scale for fees that varies according to factors such as parents’ income. Significantly, from August 2019, a new law, Gute-KiTa-Gesetz (Good Childcare Act), requires all municipalities to apply this scale of fees and to waive the fees for parents in need.

Quality

Quality in terms of staff ratios and qualifications (which can be associated with ratios) varies between countries as do adherence to a common curriculum and inspection arrangements (see Table 2). Focusing on staff qualifications, a crucial indicator of quality (Manning et al., Reference Manning, Garvis, Fleming and Wong2017), there are clear differences between countries. In France, qualified teachers are employed in écoles maternelles, and most crèches employ staff with degree level qualifications. In England, only maintained nursery schools and nursery classes (not private providers) must employ qualified teachers. One consequence is that three- and four-year-old children from more disadvantaged areas have access to better-qualified staff, as they are more likely than those from richer areas to attend nursery classes (Gambaro et al., Reference Gambaro, Stewart and Waldfogel2015). In Germany, the majority of pedagogical staff in childcare centres in Western and Eastern Länder are pre-primary ‘educators’ (Erzieher/in) (73% and 87%) (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2018a), with a three-year post-secondary vocational qualification (OECD, 2016d).

In all three countries, training for childminders is limited. Although they only cater for a small proportion of children under three in England and Germany (8% and 5% respectively) (DfE, 2018f; Statistisches Bundesamt, 2018a), in France the percentage is 19% (Villaume and Legendre, Reference Villaume and Legendre2014) and there are concomitantly high levels of public expenditure on individual care – €5,044bn compared with €6,274bn on crèches/collective institutions in 2016 (Cnaf, 2017).

Discussion: Government, financing and (effective) social investment

In this final section, drawing on our previous findings, we analyse the relationship at a country level between policy, provision, funding and regulation on the one hand, and the availability, affordability and quality of ECEC on the other. We then compare and contrast the three countries in terms of the extent to which social investment in ECEC can be deemed to be effective.

Country-level analysis

In France, at the cultural level, childcare is essentially the responsibility of institutions outside of the family. This is most apparent for children aged three and over, with institutional provision being via the longstanding école maternelle part of the national education system. Participation is the norm even though attendance is not compulsory. Qualified teachers with degree level qualifications are employed, there is a common curriculum and a national inspection system. For children under three, the situation is different. Although disadvantaged two-year-olds should be prioritised for a place in the école maternelle, local discretion means that more advantaged children can be admitted instead. Childcare centres, in contrast to écoles maternelles are the responsibility of the local authority, which is not obliged to provide such facilities. This leads to geographical variation as regards availability. There is also discretion exercised at the local level, with disadvantaged children not necessarily being prioritised for a place. Moreover, the public subsidies are not sufficiently generous to ensure that formal childcare centres are affordable for parents on low incomes. Staff in crèches are not as highly qualified as teachers in écoles maternelles, but they are more qualified than assistantes maternelles (childminders) whose employment costs are subsidised by the state. Recent expansion of ECEC has taken this form, and has created a clear tension with attaining high quality ECEC.

In England, the role of central government and its reliance on marketised provision is key to understanding the availability, affordability and quality of ECEC. England, unlike France, was a laggard as regards the development of publicly-funded ECEC, with private (for-profit/not-for-profit) provision historically meeting the childcare needs of working mothers (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). Central government funding for universal part-time ECEC was first made available from the late-1990s. Since then, governments of different political complexions have promoted and fostered local childcare markets which are centrally controlled via regulation and funding (cf. Ranson, Reference Ranson2008; West, Reference West2015). Outside the free early years provision, costs to parents are high, with no parental means-testing unlike either France or Germany. There are no subsidies for parents with very young children who are not in work, so restricting access to ECEC for children below the age of two from the poorest backgrounds. Although the government is reliant on private (for-profit/not-for-profit) providers to deliver free ECEC, public funding is deemed insufficient by private providers. As a result, they seek to cross-subsidise via fees paid directly by parents for additional provision, where they are able to do so (West et al., Reference West, Roberts and Noden2010). Most central government capital funding to expand ECEC provision requires co-funding by local authorities. But severe cuts to local authority budgets have militated against contributions, so affecting availability. With respect to quality, whilst there is a ‘level playing field’ across private and public providers as regards public funding for free early years provision, and a common curriculum, there is no equivalence in terms of staff qualifications – unlike France and Berlin. This means that quality differs between providers of different types, with only maintained nursery schools and nursery classes (minority providers for children under three) being required to employ qualified teachers.

In Germany, the roles of central, regional and local governments and decentralisation are fundamental to understanding availability. The higher levels of childcare provision in the Eastern German Länder are associated with the historically high levels in the former East Germany where the dual breadwinner/state carer cultural model prevailed; this is in contrast to the former West Germany, where low levels of provision were related to the male breadwinner model. Cultural norms and institutional factors continue to be relevant with participation in, and institutional availability of, ECEC being higher in the Eastern than Western German Länder (Mätzke, Reference Mätzke2019; Blome, Reference Blome2018). Indeed, research suggests that federal subsidies have had faster results in the Eastern Länder, where local governments – unlike those in the Western German Länder – were able to rebuild the institutional model that was in place prior to reunification (Oliver and Mätzke, Reference Oliver and Mätzke2014). A further reason for the variation is that left-wing Länder governments have been willing to invest significantly more resources in the expansion of the public infrastructure of ECEC than their right-wing counterparts (Busemeyer and Seitzl, Reference Busemeyer and Seitzl2018). The regulation of childcare centres – and hence quality – varies regionally with respect to staff qualifications and adherence to curriculum guidelines. Turning to affordability, across Germany, unlike either France or England, the public subsidies – via free provision as in the case of Berlin, or means-testing, or the waiving of fees across Germany – can be seen to facilitate access for children from disadvantaged families.

Meeting the conditions for effective social investment in ECEC?

The question arises as to whether the conditions for effective social investment have been met in our case study countries. Strict financial investment, measured in terms of public expenditure, is far higher in France than in the other two countries. However, social investment as assessed in terms of availability, affordability, and quality of ECEC varies. This in turn is related to the role played by government (of different levels), the characteristics of financial investment, and the regulation of ECEC. Our case study countries vary along these dimensions, which can be seen to facilitate or create impediments to effective social investment in ECEC: this we define in terms of high levels of participation, costs to parents/carers that take account of parents’ ability to pay fees (if any), and quality provision (specifically, highly trained staff).

For children between three and the start of compulsory education, social investment can be deemed to be broadly effective in two countries, France and Germany, but not in England. The conditions of availability and affordability are broadly met in all three countries: participation is near universal (95% to 100%) and full- or part-time provision is available free of charge (albeit for differing amounts of time). However, only in France and Germany are the conditions for quality met, with well-qualified staff (with degrees) being the norm. This is not the case in England as private (for-profit/not-for-profit) childcare centres are not required to employ qualified teachers.

For children under three, social investment cannot be deemed to be effective in any country, albeit for different reasons. Participation is, unsurprisingly, much lower – indeed, across the EU in 2016, participation in ECEC reached 50% in only five countries (OECD, 2016c). France is the only case study country with this high level of participation, in line with cultural norms; but, even here, there is limited availability of childcare centres. Participation is much lower in Germany, although it is higher in the Eastern than Western Länder again reflecting differing cultural norms. In all three countries, parents are normally charged fees. Although in Germany and France these are mainly means-tested, in the latter the costs are high for less well-off parents, hampering access. In England, beyond the free provision, costs for parents are high as a result of the heavily marketised system, with no means-testing or controls on fees charged. In contrast to France and Germany, where staff qualifications in childcare centres are high, in England staff qualifications in private childcare centres are low. Training for childminders is minimal in all cases, but only in France are government subsidies paid directly to parents to assist families with employing childminders.

The issues of availability and affordability are crucially important when considering access to ECEC, as quantitative research suggests that differential uptake of ECEC by children from higher and lower income families is more the result of constraints on the ‘supply side’ by the state (e.g. policy design and insufficient levels of spending) than individual preferences and norms (Abrassart and Bonoli, Reference Abrassart and Bonoli2015; Pavolini and Van Lancker, Reference Pavolini and Van Lancker2018). Although efforts have been made to incentivise participation by children from low income families – via free provision, means-testing, tax credits and differential funding of providers – in all three countries, parents of children under three from lower income families are less likely than those from higher income families to use ECEC (OECD, 2016b; Schober and Spieß, Reference Schober and Spieß2013; Collombet, Reference Collombet2018). This in turn raises a further issue: namely, that parents who do not use childcare services may not do so because of logistical challenges such as ‘matching up the time and space constraints’ of services (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Naumann and Koslowski2017: 1383). The differing policy designs thus hinder effective social investment in ECEC for the most disadvantaged groups.

This in turn raises questions about the concept of social investment. Over the past two decades, expenditure on ECEC has increased in England and Germany and has remained high in France. However, public expenditure does not necessarily equate with effective social investment. What matters is how money is spent and on what. Thus, in England, although expenditure on ECEC has increased dramatically, the policy design has promoted private investment (Adamson and Brennan, Reference Adamson and Brennan2014) at the expense of both quality and affordability. And in France, although expenditure is high, direct government subsidies to parents to employ childminders, with minimal training, also militate against high quality and affordable ECEC. There are clearly tensions and contradictions between the goals of social investment in high quality ECEC and private investment in service delivery – either at an institutional or family level.

In conclusion, England, France and Germany vary in the extent to which they meet the conditions for effective social investment. The extent of social investment rests fundamentally on levels of funding, but its effectiveness also depends on the role played by central, regional and local government in terms of commitment to ECEC, especially with respect to the type of public investment in ECEC, and in a willingness to regulate to ensure high quality, which is particularly important for child development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.