Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 calls for the eradication of poverty in all its forms by 2030. Shame lies at the heart of poverty. In his seminal work on the capabilities approach, Amartya Sen argued that the ability to go without shame is a key capability and therefore forms part of any notion of absolute poverty (Zavaleta, Reference Zavaleta2007). Empirical explorations of the ‘poverty-shame nexus’ find that poverty is a universally shameful experience (Walker, Reference Walker2014; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Kyomuhendo, Chase, Choudhry, Gubrium, Nicola, Lodemel, Mathew, Mwiine, Pellissery and Ming2013).

Social protection has firmly established itself as one of the key policy areas in the fight against poverty in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Devereux et al., Reference Devereux, Roelen and Ulrichs2016). Many LMICs are investing in the establishment of social protection systems, aiming to provide a coherent and interlinked set of contributory and non-contributory programmes that provide a minimum level of income security through the life cycle (EC, 2015). These developments are in line with SDG target 1.3, calling for the implementation of nationally appropriate social protection systems and the achievement of substantial coverage of the poor and vulnerable. Non-contributory interventions are core to this effort and have expanded rapidly in the last two decades, with many more people now covered by social assistance such as old-age pensions, child grants and disability benefits (ILO, 2017).

Interventions have the potential to both alleviate and reinforce the poverty-shame cycle (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Greater ability to meet basic needs and to participate in social activities can improve dignity and instil confidence and self-respect (Molyneux et al., Reference Molyneux, Jones and Samuels2016). An expanding evidence base on social assistance attests to positive psychosocial effects (Attah et al., Reference Attah, Barca, Kardan, MacAuslan, Merttens and Pellerano2016). Nevertheless, such impacts are often rendered serendipitous side-effects rather than central issues of focus. At the same time, design and implementation of social assistance, and the wider discourse within which it takes place, can instigate stigma and shame (Roelen, Reference Roelen2017). Despite the centrality of stigma within research on welfare in high-income countries (HICs) (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016; Pinker, Reference Pinker1971; Spicker, Reference Spicker1984), it remains relatively unexplored within debates of incipient social protection systems in LMICs (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014).

This article aims to explore and critically discuss the role of social assistance in LMICs in negating poverty-induced shame or reinforcing a ‘spoiled identity’ (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963) associated with receiving social assistance. Analysis is informed by a comprehensive review of literature on social assistance in LMICs in relation to issues of dignity, stigma and shame. We focus on social assistance for two reasons: (i) the expansion of social protection in LMICs has primarily been concentrated in social assistance, and (ii) schemes’ non-contributory and often narrowly poverty-targeted nature has particular implications regarding stigma and shame. Social assistance interventions include (but are not exclusive to) unconditional cash transfers, conditional cash transfers, public works programmes and more comprehensive anti-poverty programmes such as ‘graduation programmes’.

This article seeks to contribute to academic discourse and policy debate in LMICs by giving centrality to issues that lie at the core of poverty but are currently peripheral to research and policy making in development context. Doing so is an inherently interdisciplinary exercise, gleaning understandings from across psychology, sociology, political science and philosophy. It also crosses the Global North and Global South divide by framing our assessment in LMICs against longstanding literature in HICs and by linking to global debates in social policy, notably targeting and conditionality.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: firstly, we unpack the concepts of shame and stigma. Secondly, we offer a schematic overview of linkages between social assistance, shame and stigma. Thirdly, we interrogate the role of social protection in breaking or reproducing shame and stigma in LMICs. Finally, we reflect on policy and research implications.

Understanding shame and stigma

Understandings of shame and stigma differ across disciplines, each offering vital insights for unpacking the linkages between shame, stigma and social assistance.

Shame

In psychology, shame is classed as a ‘self-conscious emotion’ that involves a process of self-reflection and self-evaluation (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007). Shame can be distinguished from other self-conscious emotions such as guilt as it constitutes a negative evaluation of the ‘self’. Guilt, in contrast, represents a negative evaluation of one’s actions. The key distinction is “whether the individual places a differential emphasis on a bad self (“I did that horrible thing”) versus a bad behaviour (“I did that horrible thing”)” (Tangney, Reference Tangney1996) (p. 742). Shame, and the associated sense of worthlessness, primarily leads to negative coping behaviours, including (i) hiding, dissociation and turning away from responsibilities (as opposed to amending and taking responsibility), (ii) self-oriented distress (as opposed to other-oriented empathy), (iii) anger and aggression, and (iv) psychological problems such as depression (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007). In contrast, guilt generally results in tension, remorse and regret and can motivate individuals to take responsibility for their actions (ibid), and make amends or incentivise positive behaviour.

Sociologists emphasise the inherent social nature of shame, and the importance of understanding the context in which it arises (Scheff, Reference Scheff2000). In his theory on the ‘looking-glass self’, Cooley proposes that the individual sense of self emerges through social relations, and that the imagined judgement by others represents a true reflection of their self (Scheff, Reference Scheff2003). As such, every social interaction has the potential to lead to shame or (the opposite emotion of) pride, with shame signalling disconnect and alienation (Scheff, Reference Scheff2014). The shift towards individualism away from the idea of complex personal and social relationships in many modern societies can lead to disconnect and alienation, and thereby to contribute to the ubiquity of shame (Scheff, Reference Scheff2014).

The moral function of shame and its role in incentivising desirable behaviour has been the subject of extensive debate within philosophy (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2004). Shame – and the desire to avoid it – has long been recognised as promoting socially responsible behaviour and therefore playing a vital role in the advancement of society (Van Vliet, Reference Van Vliet2008). This regulatory function of shame appears to cut across cultures and contexts (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Yet others point to shame’s morally dubious function as its effectiveness in terms of promoting pro-social behaviour is disputable (Teroni and Bruun, Reference Teroni and Bruun2011). Nussbaum (Reference Nussbaum2004) developed various arguments against the use of shame as a punitive or regulatory measure, including its ambiguous role in history, spurious effectiveness and risk of institutionalising shame and stigma.

It is important to point out that these various disciplinary understandings of shame are by no means universal or unambiguous. The experience of shame may be deemed to have positive valence, particularly in more collectivist societies such as in South East Asia (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). In China, for example, shame is more prevalent and therefore more commonly felt, but is also more acceptable than other emotions such as anger (Wong and Tsai 2007). Nevertheless, Engel (Reference Engel2017) warns against a binary understanding of shame in ‘Western’ or more individualist societies versus ‘non-Western’ or more collectivist contexts as this may lead to the oversimplified extrapolation that the use of shame is more acceptable in developing versus developed contexts. Indeed, research in seven countries across ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ societies – including China and South Korea – highlights the overwhelmingly negative experience and moral judgement that accompanies experiences of shame and being shamed (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014; Walker, Reference Walker2014).

Stigma

Stigma may be considered a key mechanism through which shame is produced. In his seminal work on stigma, Goffman (Reference Goffman1963) posits that stigma denotes an attribute that is discreditable, leading to a ‘spoiled identity’. Other definitions have referred to stigma representing a characteristic that is different from ‘normal’ and triggers disapproval or devaluation in certain social contexts (Bos, Pryor, Reeder, and Stutterheim, Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013; Link and Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001) with those being stigmatised somehow deemed to be less human (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963). Stigmatisation constitutes others’ responses to stigma and can be overt, such as avoidance and humiliation, as well as more subtle, including lack of eye contact (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013). This, in turn, interacts with ‘potential internalization of the negative beliefs and feelings associated with the stigmatised condition’ (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013: 2), understood as self-stigma or indeed shame. Others have referred to enacted and felt stigma (Scambler, Reference Scambler2018) to distinguish between stigma and shame respectively.

The extent to which stigma is a vehicle for shame is contested. Goffman (Reference Goffman1963) states that managing stigma or its visibility, such us through avoiding ‘stigma symbols’ and investing in ‘disidentifiers’, almost inevitably leads to feelings of failure in relation to the self. It follows that shame becomes a central possibility in the face of stigma (ibid). However, strong identity of self and contestation of the devaluation of others means that shame may not follow stigma (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016), and coping with stigma may lead to more positive ‘goal-oriented behaviour’ (Van Laar and Levin, Reference Van Laar, Levin, Levin and Van Laar2005).

Nevertheless, as pointed out by Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001), the fact that outcomes of stigma may differ from one person to the next does not negate that it is a ‘persistent predicament’ that needs to be addressed. Indeed, while the extent to which the effects of stigma culminate into shame may depend on the individual (Van Laar and Levin, Reference Van Laar, Levin, Levin and Van Laar2005), discounting its importance renders invisible the processes and structures that produce and legitimise shame. Structural stigma denotes the mechanism through which stigmatisation is legitimised and institutionalised, and through which devaluation of otherness becomes engrained in society’s ideologies (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013; Walker and Chase, Reference Walker and Chase2014).

Framing the linkages between social assistance, shame and stigma

Building on interdisciplinary understandings of shame and stigma, we explore how social assistance may negate shame and contribute to greater dignity but also how receipt may be marked by stigma and shame. We consider social assistance separately from other strands of social protection – notably social insurance and labour market policies – due to its distinct features of providing non-contributory support to often narrowly targeted groups. These features hold direct links to understandings and narratives of deservingness with implications for stigma and shame.

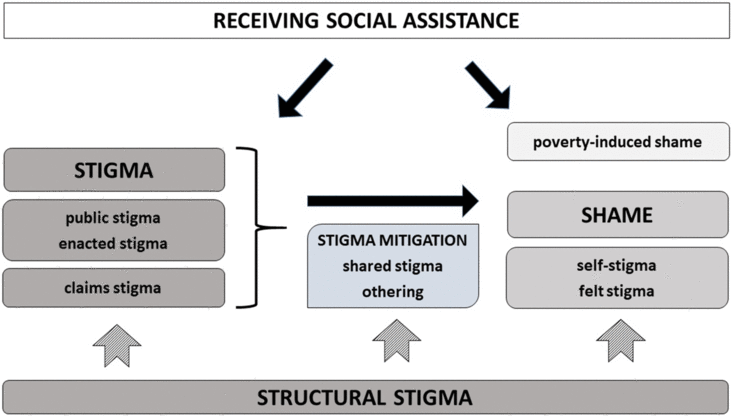

Figure 1 offers a schematic representation of linkages between social assistance, shame and stigma.

Figure 1 Framing the linkages between social assistance, shame and stigma

In exploring the relationship between social assistance and shame, we follow psychological discourse, taking shame to constitute a primarily negative emotion that is associated with the internalisation of negative beliefs about the self (Tangney, Reference Tangney1996). Given the strong connection between poverty and receipt of social assistance, this includes both shame as a result of living in poverty, or poverty-induced shame (Walker, Reference Walker2014), and internalised feelings of stigma associated with receiving social assistance, in line with the notions of self-stigma (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013) and felt stigma (Scambler, Reference Scambler2018). Social assistance may directly reduce poverty-induced shame and enhance dignity through its provision of income security (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge, Schmidt and Pellerano2016), and indirectly impact shame through stigma associated with receipt of social assistance (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014).

Being a beneficiary of social assistance could denote a stigma, with the receipt of social assistance signifying a devalued identity and making one ‘discreditable’ (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963). We distinguish between two types of stigmatisation: (i) stigmatisation through others’ emotional and behavioural reactions to the stigma, also referred to as public stigma (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013) and enacted stigma (Scambler, Reference Scambler2018) and (ii) stigmatisation through the process of receiving social assistance benefits, also referred to as claims stigma (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016) or treatment stigma (Stuber and Schlesinger, 2006). A well-established literature from HICs attests to the widespread negative public attitudes towards those receiving welfare, particularly when those in receipt of welfare are considered to be less deserving (Larsen, Reference Larsen2008). Design and delivery of social assistance can serve as important vehicles for stigma, both directly (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016; Roelen, Reference Roelen2017; Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018) and through their interaction with public attitudes of deservingness (Larsen, Reference Larsen2008).

The link between stigma and shame is tenuous (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016). Individual coping mechanisms and a strong identity of self may counteract the effects of stigma (Van Laar and Levin, Reference Van Laar, Levin, Levin and Van Laar2005). Sharing the stigma of receiving social assistance – so-called ‘shared stigma’ (Van Laar et al., Reference Van Laar, Derks and Ellemers2013) – or the process of distancing oneself from others also receiving benefits – referred to as ‘othering’ (Lister, Reference Lister2004) – may also act as strategies for mitigating stigma associated with social assistance receipt.

Finally, structural stigma denotes the wider societal framing within which the manifestation of shame and process of stigmatisation is legitimised and institutionalised (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013). Structural stigma of those living in poverty and receiving social assistance may manifest itself through political ideologies, policy framing, media narratives and popular discourse (Walker and Chase, Reference Walker and Chase2014), and interacts with stigma and shame at all levels. As argued by Tyler and Slater (Reference Tyler and Slater2018), the cultural and political economy of stigma are crucial in the (re)production of social inequalities, and any attempt to tackle such inequalities needs to engage with the social and political side of stigma.

Receiving social assistance in LMICs: the interface between shame and stigma

We move on to interrogate the role of social assistance in (re)producing or counteracting shame and stigma, assessing the role of social assistance in LMICs in negating shame and enhancing dignity, or constituting a shameful experience.

Social assistance: counteracting shame or a shameful experience

A review of empirical evidence provides powerful testimony to the role of social assistance in counteracting poverty-induced shame. Research widely suggests that living in poverty in LMICs is a shameful experience (Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Patel, Schafft, Rademacher and Koch-Schulte2000). A recent multi-country study found that living in poverty is commonly associated with feelings of inferiority, embarrassment and humiliation (Chase and Bantebya-Kyomuhendo, Reference Chase, Bantebya-Kyomuhendo, Chase and Bantebya-Kyomuhendo2014). Quantitative studies confirm this picture. Using quality of life survey data from Chile, Hojman and Miranda (Reference Hojman and Miranda2018) show that shame-proneness is more prevalent in the lower quintiles of the income distribution. Dornan and Oganda Portela (Reference Dornan and Oganda Portela2016) find consistent links between lower levels of household consumption and higher self-reported feelings of shame among 12-year old children in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam.

A rapidly expanding evidence base indicates that social assistance can be powerful in avoiding or countering shame by instilling a sense of dignity and improving psychosocial wellbeing (Attah et al., Reference Attah, Barca, Kardan, MacAuslan, Merttens and Pellerano2016). These effects are primarily mediated through poverty reduction (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge, Schmidt and Pellerano2016), and can be referred to as indirect income effects (Roelen et al., Reference Roelen, Delap, Jones and Karki Chettri2017). Experiences across LMICs indicate that a regular inflow of cash can reduce stress and improve mental health (Samuels and Stavropoulou, Reference Samuels and Stavropoulou2016). Empirical evidence also attests to the way in which poverty reduction as a result of social assistance strengthens the notion of self through being able to meet one’s own expectations about the self and what it should be capable of. In relation to South Africa’s Child Support Grant (CSG) Hochfeld and Plagerson (Reference Hochfeld and Plagerson2011) observed that: “Grants were seen as a tool to counteract the shame associated with not being able to provide for one’s children” (p. 56).

We can understand social assistance’ positive effects through the lens of Goffman’s notion of ‘disidentifiers’ (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963). Social assistance beneficiaries often invest in improving physical appearance. Female participants in a comprehensive anti-poverty programme in Burundi invested cash in wax print clothing as it allowed them to participate in activities with dignity (Devereux et al., Reference Devereux, Roelen, Sabates, Stoelinga and Dyevre2015). Transfers from the Social Cash Transfers (SCT) in Malawi and CSG in South Africa were used for the purchase of clothing and self-care products in a bid to counter public stigma (Adato et al., Reference Adato, Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler2016; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Tsoka, Reichert and Hussaini2010). The ability to invest in disidentifiers of poverty serves as an important mechanism through which social assistance affords dignity and counteracts poverty-induced shame.

However, findings are not unequivocally positive. In China, the Minimum Living Security System (MLSS) was found to negatively impact psychological health of its recipients, including low self-confidence and self-satisfaction, as a result of widespread welfare stigmatisation (Qi and Wu, Reference Qi and Wu2018). We note however that this is the only study in our review of literature from LMICs that reports a systemic negative relationship between the receipt of social assistance and a negative evaluation of the ‘self’.

Social assistance: triggering public or enacted stigma

Public or enacted stigma directed towards those in receipt of social assistance is a widely documented and well-researched phenomenon in HICs. Work by Pinker (Reference Pinker1971) and Spicker (Reference Spicker1984) discuss the instrumental use of stigma as a disincentive for claiming benefits, framing stigma as a form of violence and grave injustice inflicted upon welfare recipients. Oorschot (Reference Oorschot2000) and Larsen (Reference Larsen2008) explore public attitudes towards welfare recipients and their deservingness, and the bidirectional effect of such attitudes on stigma associated with welfare receipt. More recent research by Patrick (Reference Patrick2016) and Garthwaite (Reference Garthwaite2016) in the UK offer compelling accounts of widespread negative attitudes and strong negative effects of stigma on psychological wellbeing of out-of-work claimants and food bank users.

Emerging research suggests that stigma is a feature of social assistance receipt in countries with more incipient social protection systems. Research in China, India, Pakistan and Uganda finds that shame is a common experience for those benefiting from anti-poverty interventions, including social assistance (Gubrium, Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014; Qi and Wu, Reference Qi and Wu2018). In South Africa, which has a longer history of social protection, communities’ negative views of CSG recipients were found to lead to erosion of dignity (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Noble, Ntshongwana, Neves and Barnes2014). Nevertheless, evidence with respect to public stigma directed at those receiving social assistance in LMICs is thin on the ground, leading to a large gap in our understanding of the public response to those receiving social assistance and whether or not pervasive levels of public stigma as observed in HICs play out in similar ways in LMICs.

Social assistance: inducing claims stigma

The ways in which social assistance is designed and delivered can constitute powerful mechanisms or mediators for the transmission of stigma (Baumberg, Reference Baumberg2016; Roelen, Reference Roelen2017). We explore three distinct policy features that have been explored in LMICs with potentially far-reaching repercussions, namely targeting, conditionality and service delivery.

Targeting

The extent to which interventions should be targeted to narrowly defined groups or distributed universally to populations at large is one of the most contentious issues in social assistance. While research in HICs has highlighted the importance of notions of deservingness in relation to deciding which groups are to be eligible for support (Oorschot, Reference Oorschot2000), discussions in LMICs tend to adopt a more technical lens. Proponents of targeting emphasise the importance of redistribution, particularly in contexts of limited resources and equity, but opponents highlight issues of paternalism, exclusion and stigma (Devereux, Reference Devereux2016). Recent reviews of targeting found stigma and shame to be substantial psychosocial costs associated with targeting (Devereux et al., Reference Devereux, Masset, Sabates-Wheeler, Samson, Rivas and te Lintelo2017), and to deter take-up of benefits (White, Reference White2017). The risk of exclusion and stigma effects play into calls for universal provision of social protection (Kidd, Reference Kidd2017), and are core to calls for Universal Basic Income (UBI) (Standing, Reference Standing2017).

Evidence from LMICs indicates that stigma is sometimes used instrumentally within the process of targeting. Self-targeting mechanisms rely on stigma to ensure that only the most vulnerable will apply (Coady et al., Reference Coady, Grosh and Hoddinott2004). In India, stigma associated with the use of Fair Price Shops, along with their location, ensured that they were accessed only by the poor (White, Reference White2017). The government of Madhya Pradesh state in India explicitly attempted to discourage eligible households from applying for social protection by painting houses of those eligible to read ‘I am poor’ (Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014).

Stigma also emerges as an inadvertent by-product of the targeting process itself, but with harmful consequences no less. In China, verification of applicants to the urban dibao social assistance scheme can include a community inspection process that asks community members to call out non-eligibility, giving rise to concerns about stigma effects (Yan, Reference Yan, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Eligibility criteria for Pakistan’s Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) extended only to ‘ever-married women’ with children (Choudry, Reference Choudry, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014), thereby paying lip service to stigmatisation of an already marginalised group.

By and large, however, literature on experiences with targeting in LMICs lacks engagement with respect to issues of stigma and shame. Instead, studies point more commonly towards the social divisiveness as a result of poverty targeting (Ellis, 2012).

Conditionality

Conditionality refers to behavioural requirements attached to the receipt of transfers aimed at achieving behaviour change (Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018). Its use has been extensively studied and debated in HICs, including its (lack of) effectiveness in instigating positive change (Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018), negative effects on mental health (Davis, Reference Davis2019), the way in which it undermines citizens’ autonomy (Curchin, Reference Curchin2019) and its interaction with attitudes towards deservingness (Oorschot, Reference Oorschot2000).

In LMICs, conditionality has become a popular component of social assistance. Following the emergence of conditional cash transfers (CCTs) in the mid-1990s, almost all countries in Latin America now operate at least one such programme (Cookson, Reference Cookson2018). These programmes commonly require recipients to take up services for the benefit of their children, such as sending them to school or attending health check-ups. They have been found to have positive effects on consumption, diet and use of services (Bastagli et al., Reference Bastagli, Hagen-Zanker, Harman, Barca, Sturge, Schmidt and Pellerano2016; Fiszbein and Schady, Reference Fiszbein and Schady2009; Lagarde et al., Reference Lagarde, Haines and Palmer2007).

In line with debates in HICs, conditionality is also highly contested in LMICs and grounded in concerns about the individualisation of poverty and the focus on monitoring and control of behaviour. In her analysis of Peru’s CCT, Cookson (Reference Cookson2018) finds that conditionality relieves the state of responsibility while it at the same time gives credence to the notion that children’s deprivations are a result of parents’ bad behaviour. This individualisation of poverty offers fertile ground for stigma and shame. Recipients may internalise failure to comply with conditions, or to improve outcomes for their children and themselves. In turn, service providers may tap into these dynamics to monitor and enforce compliance with conditions (Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018). Gubrium (Reference Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014) suggest that it is likely that the imposition of conditionality in anti-poverty policy settings heightens the shame that is experienced by policy recipients.

However, available empirical evidence does not unequivocally support this notion. Research in Lesotho and Malawi indicates that young people experience stigma and shame as a result of receiving ‘free money’, and would prefer to work in return for their cash transfer (Ansell et al., Reference Ansell, Blerk, Robson, Hajdu, Mwathunga, Hlabana and Hemsteede2019). By and large, literature on CCTs has overlooked notions of stigma and shame.

Service delivery

Service delivery can serve as a vehicle for stigma, but may also increase self-esteem and counter shame (Cookson, Reference Cookson2018). A supportive approach to case management within a programme in Burundi was found to reinforce positive psychosocial effects following reduced poverty (Roelen and Devereux, Reference Roelen and Devereux2019). However, female CCT beneficiaries in Peru were found to face prejudice and derogatory treatment at the hands of programme staff on a regular basis (Cookson, Reference Cookson2018). Testimonies by female CSG recipients in South Africa indicate that many women feel mistreated and stigmatised by programme staff, sometimes leading them to forego the cash transfers in order to avoid pejorative treatment (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Noble, Ntshongwana, Neves and Barnes2014). In India, recipients of the PDS in-kind transfer programme reported that they were constantly confronted with demeaning treatment from bureaucrats, and emphasised the need to adopt coping mechanisms to mitigate the shame that they felt as a result (Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014).

Stigma effects can also be observed in relation to delivery of transfers, which often still happens physically on ‘pay-days’ in central locations within the community. Studies in India, Peru and South Africa found that many hours of queuing and waiting in public spaces to collect transfers produced great shame and humiliation (Cookson, Reference Cookson2018; Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Noble, Ntshongwana, Neves and Barnes2014). Recipients of PDS food transfers in India also noted the humiliation of repeated visits to designated shops to procure grain of such poor quality that it was deemed only appropriate for animal consumption (Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Less overt mechanisms of payments, such as digital transfers, may help to reduce stigma effects (Hojman and Miranda, Reference Hojman and Miranda2018).

Social assistance: sharing stigma

‘Shared stigma’ and ‘othering’ may interrupt the link between stigma associated with the receipt of social assistance. Shared stigma – i.e. having a stigma in common – can give rise to a shared identity that may help boost a sense of self (Van Laar et al., Reference Van Laar, Derks and Ellemers2013). This does not always hold true, however, and stigma may also arise from when those with a shared identity hold negative stereotypes about the stigma that they hold in common (Van Laar and Levin, Reference Van Laar, Levin, Levin and Van Laar2005). The process of distancing oneself from others in the same situation, also referred to as ‘othering’, is widely observed in relation to poverty (Lister, Reference Lister2004), and may also occur among social assistance beneficiaries. As noted by Baumberg (Reference Baumberg2016), beneficiaries may subscribe to the idea that receiving social protection constitutes a devalued identity but believe that this does not apply to them.

We can observe some evidence for these mechanisms in LMICs. Beneficiaries of the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) in Pakistan indicated that they didn’t feel ashamed to receive support as they considered wider economic structures to be responsible for their situation (Choudry, Reference Choudry, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Similarly, mothers receiving the CSG in South Africa attributed their need for income support to lack of well-paid jobs and considered themselves to be deserving (Hochfeld and Plagerson, Reference Hochfeld and Plagerson2011). Seeking solace in a shared devalued identity or actively seeking to drive a wedge between the stigma and one’s own identity can act as stigma mediators, and delink stigma from shame.

Social assistance: institutionalising stigma

Structural stigma refers to how economic and political systems as well as societal belief and value systems interact to legitimise or potentially instrumentalise stigmatisation of those with a devalued identity (Tyler and Slater, Reference Tyler and Slater2018). In relation to social assistance, this represents the extent to which discourse at a societal level holds people in receipt of social assistance responsible for their situation In the US and UK, for example, ideas of an ‘underclass’ and ‘culture of poverty’ took hold in the 1980s and continue to dominate perceptions and popular debate regarding poverty and welfare (Lister, Reference Lister2004; Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018), leading to widespread demonization of welfare recipients.

Contexts of social, economic and political power serve the institutional and ideological legitimisation of shame and stigma (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Pryor, Reeder and Stutterheim2013), yet this role of power has been largely overlooked (Link and Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001). As highlighted by Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001), stigma exists by the virtue of power: “stigmatisation is entirely contingent on access to social, economic, and political power that allows the identification of differentness […] and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion and discrimination” (p. 367). Neoliberal paradigms that cast poverty and need for social assistance as a result of moral deficiency on behalf of individuals directly play into this power and the legitimisation of stigmatisation (Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2018). Indeed, experiences in HICs show that strong ideological commitment to work as a moral duty as well as to the idea that welfare dependency represents a personal failure is likely to feed into structural stigma (Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018).

Experiences from LMICs that have gone through economic reform followed by rapid poverty reduction but coupled with rising levels of inequality illustrate how structural stigma may take hold. In China, for example, modernisation and greater focus on socioeconomic status has meant that those left behind by economic growth, and particularly those living in urban poverty, have become increasingly viewed as failed individuals displaying dysfunctional behaviour (Yan, Reference Yan, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Scholarly writing and media have come to express strong concern over welfare dependency, feeding into negative stereotyping and stigma (ibid). Pellissery et al. (Reference Pellissery, Lodemel, Gubrium, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014) discuss how framing of anti-poverty policies can be an important vehicle for shame with large inequalities, strong social stratification, market-driven development and conditionality opening the doors to blame and shame of those living in poverty and in receipt of support.

Current policy rhetoric in various low-income countries (LICs) suggests alignment with neoliberal perspectives that posit the role of the state as offering temporary support to those most deserving but ultimately place the responsibility of moving out of poverty with the individual. Governments in Ethiopia and Rwanda, for example, are committed to the objective of ‘graduation’ and ensuring that the majority of people living in poverty are weaned off long-term support (Devereux and Ulrichs, Reference Devereux and Ulrichs2015). More widely, the notion of ‘productive inclusion’ emphasises the role of social assistance in unlocking people’s productive potential and reducing poverty by focusing on micro-entrepreneurship and livelihoods (Mariotti et al., Reference Mariotti, Ulrichs and Harman2016). Notwithstanding the potential of such support in affecting positive change (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Duflo, Goldberg, Karlan, Osei, Parienté, Shapiro, Thuysbaert and Udry2015), this highly individualised discourse negates structural constraints that lock people into poverty, thereby opening up ground for structural stigma.

Rights-based language and practice underpinning social protection may serve as an important antidote to structural stigma, and subsequently to stigma at all other levels (Yan, Reference Yan, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). Nevertheless, experiences from India and South Africa, two countries that are commonly praised for their rights-based approach to social protection with major programmes being underpinned by legislation (Kaltenborn et al., Reference Kaltenborn, Abdulai, Roelen and Hague2017), show that such an approach is no guarantee for stigma-free policy. Public discourse emphasises the moral unworthiness of recipients with popular adaptations of programme names in local languages, such as the reference to ‘lazy work scheme’ for MNREGA in India (Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014). CSG recipients in South Africa looking down on other recipients and considering them undeserving of support (Hochfeld and Plagerson, Reference Hochfeld and Plagerson2011) is emblematic of the pervasiveness of negative stereotypes. This is in line with work by Oorschot (Reference Oorschot2000) and Larsen (Reference Larsen2008) in HICs, finding that public attitudes towards welfare recipients are strongly influenced by perceptions of deservingness and ways in which policy design confirms or counters such perceptions.

Discussion

The analysis of empirical evidence from across LMICs suggests that social assistance presents a two-edged sword in relation to shame and stigma. The provision of regular cash transfers allows for investing in disidentifiers and can lead to greater dignity. Nevertheless, stigma associated with receipt of social assistance is a reality, and interacts with ubiquitous poverty-induced shame. This poses a concern for intrinsic and instrumental reasons: beneficiaries’ dignity is undermined and their psychosocial wellbeing undercut, thereby potentially offsetting programmes’ positive effects on poverty and wellbeing. The analysis suggests a need for social assistance in LMICs to place greater emphasis on issues of stigma and shame.

Programme design and delivery needs to be assessed through a shame and stigma lens, seeking to understand how interventions may re(produce) claims stigma and seeking to break the cycle. While targeting and conditionality emerge as strong conduits for stigma and shame in HICs, the evidence is less unequivocal in LMICs. Given the scarce evidence base, it is unclear whether this is a reflection of reality or an artefact of the existing knowledge gaps.

Literature does offer pointers for minimising stigma enacted through service delivery. Pragmatic solutions include less overt targeting and payment procedures (Hojman and Miranda, Reference Hojman and Miranda2018), such as digital solutions for payments of transfers, thereby reducing the exposure of stigmatised individuals. Similarly, the extent to which frontline staff are trained to positively interact with social protection beneficiaries, particularly in the face of structural and public stigma, will be crucial.

Nevertheless, one could argue that such practical solutions merely act as palliative measures: while they may negate the effects of stigma and reduce the potential for shame, they fail to address wider discourse and popular narratives that constitute socially, culturally and institutionally engrained patterns of structural stigma. Social assistance that counters shame and safeguards dignity may require a recast of its underlying principles, most notably in relation to targeting and conditionality. Universalism has been proposed as a key principle for recasting debates and understandings of deservingness, and as vital for counteracting neoliberal systems of redistribution that instrumentalise and legitimise shame (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2015; Standing, Reference Standing2017). However, as noted above, the current evidence from LMICs offers limited insight into the shape of form or structural stigma.

Indeed the knowledge base regarding shame and stigma in relation to social assistance in LMICs is grossly inadequate. Knowledge gaps operate at two levels: firstly, the current information base is dominated by experiences from middle-income countries (MICs), as the review in this article clearly demonstrates. This is not surprising as programmes have a longer history and are larger in scale. Although these experiences allow for extraction of broad lessons, it leaves the linkages between shame, stigma and social protection in LICs largely unexplored. Secondly, evidence is currently predominantly qualitative in nature, offering limited insight into the scale of stigma and shame, and how they may affect groups differently. Stigma and shame may be a reality for many more beneficiaries than we know, undermining their ability to harness the benefits of support. Both knowledge gaps require urgent attention because as social protection systems grow and expand, stigma and shame may become more engrained, and thereby even more problematic.

It should also be noted that while this article has focused quite narrowly on stigma and shame in the interface with social assistance, they are likely to overlap with other stigmas (Spicker, Reference Spicker1988). This holds particularly true in relation to poverty, as those living in poverty are also often part of other disenfranchised groups that carry a stigma of their own, such as disabled people, lower caste groups or ethnic groups that represent a demographic minority or are otherwise economically, socially of politically marginalised. Analogous to Kabeer’s notion of ‘intersecting inequalities’ (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer2010), we can think of ‘intersecting stigma’. Much recent debate in relation to poverty reduction has centred on the need to acknowledge people’s multiple disadvantages in order to achieve SDG 1 that calls for eradication of poverty in all its forms. In advancing the study of stigma and shame in relation to poverty, and the role of social assistance in breaking the poverty-shame cycle, greater understandings of ‘intersecting stigma’ is necessary.

Gender emerges as a notable element of intersecting stigma. The review of experiences across LMICs, including India, Peru and South Africa, highlights that stigma effects associated with delivery of transfers have a strongly gendered dimension. In their role as primary caregivers, women are either explicitly targeted by programmes or end up being the ones queueing to receive services (Cookson, Reference Cookson2018; Pellissery and Mathew, Reference Pellissery, Mathew, Gubrium, Pellissery and Lodemel2014; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Noble, Ntshongwana, Neves and Barnes2014). The fact that social assistance often plays into rather than challenges gender norms has been noted elsewhere (Holmes and Jones, Reference Holmes and Jones2013), with an increased burden of paid and unpaid work responsibilities being one consequence. Greater vulnerability to stigma proves another consequence of women’s roles in take-up of social assistance.

Finally, the lack of evidence regarding structural stigma mirrors concerns voiced by scholars in HICs. Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001) highlighted that research on stigma primarily takes an individual and interpersonal focus, overlooking wider societal and power structures that accommodate stigma and stigmatisation. In relation to welfare policy in the UK, Tyler and Slater (Reference Tyler and Slater2018) observed that studies overlook the cultural and political economy underpinning stigma, thereby limiting understandings of how stigma contributes to social classification and marginalisation. Larsen (Reference Larsen2008) argued that a mechanical understanding of public attitudes towards welfare overlooks the role of institutional design in re(producing) negative stereotypes and narratives. This article shows that understandings of structural stigma in LMICs are few and far between, both in terms of its scale and underpinning dynamics, representing a failure to acknowledge the role of power and thereby the mechanisms that underpin stigma and shame’s reproduction. Future research is required, particularly in contexts of dropping poverty rates but increasing inequality that may serve as fertile ground for stigma.

Conclusion

This article aimed to offer a critical interrogation of the role of social assistance in the interface between poverty, shame and stigma in LMICs. Despite a rapid expansion of the evidence base of the many impacts of social assistance, knowledge of and debates about its relation to shame and stigma remain thin on the ground. This stands in stark contrast to scholarship on poverty and welfare in HICs, to which issues of stigma and shame are central. This article built on the wide literature on shame and stigma from across disciplinary divides, emerging evidence on poverty, shame and social protection from across LMICs and scholarship in HICs in an effort to begin filling the void. In doing so, it advances academic and policy-oriented debates in relation to an ever-growing policy arena within these countries.

We find that positive and negative effects of social assistance in relation to stigma and shame co-exist, and that programmes have the potential to both break and reinforce the poverty-shame cycle. Social assistance has strong positive effects on psychosocial outcomes and can reduce poverty-induced shame directly. Nevertheless, this observation does not serve to negate the reality of stigma and shame for many in receipt of social assistance, and the ways in which design and delivery of interventions is intimately connected with public and structural stigma. Given their potential as conduits for stigma and shame, our analysis adds to current debates and growing ethical and moral concerns about targeting and conditionality within social protection.

The available evidence does not allow for judging whether social assistance receipt in LMICs overwhelmingly negates or plays into shame and stigma. However, making social protection more shame proof (Lister, Reference Lister2015) proves vital, particularly as many countries are working towards SDG target 1.3 of establishing nationally appropriate social protection systems. Doing so requires (i) awareness-creation of how interventions serve to reproduce shame and stigma but also have the potential to disrupt the cycles of stigma and shame; (ii) exploration of options for design and delivery options that minimise or counter stigmatisation; and, most fundamentally, (iii) engagement with ideological and political discourse about poverty and social assistance that are central to stigma and shame at any level.