Introduction

Today’s welfare states consist of multifarious instruments and provisions for the social protection of people. However, these complex welfare systems are under pressure. On the one hand, the welfare state has recently reached its «silver age» as new social and financial demands put pressure on governments to retrench and restructure existing social provisions (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001; Shahidi, 2015). On the other hand, welfare state reforms have been influenced by a logic of social investment that focuses on the generation of work incentives and activation (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Fossati, 2018). A more fundamental reform of the welfare state that has recently gained attention is the universal basic income (BI) scheme. A BI is an “income granted to all members of society as a right without means testing or conditions” (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 26). Most importantly, it is “independent of other sources of income (or wealth), employment or willingness to work, or living situation” (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004: 521; Pateman, Reference Pateman2004; see also Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs1992, Reference Van Parijs1995, Reference Van Parijs2004). Because such a reform would fundamentally deviate from the basic principles that undergird today’s welfare states –namely, prior contribution and reciprocity – the idea of a basic income has often been dismissed as politically unrealistic. Critics expect that popular support for it would be insufficient and cast doubt on its legitimacy and sustainability in case of implementation (Elster, Reference Elster1986; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2017).

Nevertheless, the majority of existing studies on the subject have discussed basic income from a theoretical or normative perspective (e.g. Elster, Reference Elster1986; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2017; Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs1992, Reference Van Parijs1995, Reference Van Parijs2004). Empirically, we know very little about popular support for BI schemes. Very few studies have actually investigated public opinion on such schemes, and even fewer have shed light on the conditions under which broad popular support for this provision could be expected (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006; Liebig and Mau, Reference Liebig, Mau and Standing2004; Pfeifer, Reference Pfeifer2009; see also recent data from the eighth round of the European Social Survey). Moreover, as we argue below, recent survey-based studies may severely overestimate actual public support for BI schemes and could thus lead to incorrect conclusions about how realistic the introduction of such schemes is. This is because instead of considering specific proposals with potential trade-offs and contingencies, existing surveys use general single-item questions, exploring agreement with the introduction of a BI or support for the state providing a basic income to all citizens. In this article, we therefore ask:

Is there popular support for basic income schemes, and to what extent does citizens’ support depend on the exact design of such a scheme and the context in which this policy is embedded?

We seek to provide a better understanding of BI support and the contingencies of this support by using conjoint experiments conducted in two countries: Finland and Switzerland. Conjoint analysis has recently gained popularity because it allows to conceptualize preferences and decisions as multidimensional choices (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Dermont, 2018). We argue that this is particularly advantageous when analyzing preferences towards new (even hypothetical) policies that are characterized by various and varying attributes (e.g. benefits, costs, eligibility criteria etc.).

We investigate citizens’ preferences in the two countries in which the introduction of a basic income scheme has recently been discussed most intensely (De Wispelaere, Reference De Wispelaere2016), and where, thus, at least some public debate has occurred. A focus on Switzerland and Finland and a comparison of these two cases enables us to gain insight into citizens’ support for BI schemes in different welfare state contexts, and in light of differently framed public debates. Thus, the present study contributes to the limited empirical literature on basic income. Some researchers have argued that research on BI schemes has not been “keeping up” with the increased interest that the issue has received in the political discourse (De Wispelaere, Reference De Wispelaere2016). By conceptualizing public support for BI schemes as a result of multidimensional choices, and by analyzing citizens’ preferences with a sophisticated experimental design, our study brings the research on BI up to speed both conceptually and methodologically.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section presents our theoretical framework and the existing research that it is based on. We then introduce our methodological approach, the data we use, and the operationalization of the concepts we deploy. The following section presents and discusses our empirical findings. The study concludes with a summary of the most important results and conclusions.

Theoretical background

Koistinen and Perkiö (Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 30) identify four dimensions crucial to the understanding of the political success or failure of a proposal for BI: (1) the qualities of the innovation itself, (2) the actors involved in the process and their positions, (3) culture, and (4) the economic and political context. According to the authors (2014: 29), these four factors explain the “drivers and barriers” of thirteen BI variants that were discussed in Finland over the last decades. Whereas the main conclusion of Koistinen and Perkiö’s work is that BI proposals can take many forms, we argue that their approach can also be applied fruitfully – from a cross-sectional comparative perspective – to an analysis of public support for BI proposals. On the one hand, dimensions (2), (3), and (4) refer to potential contextual differences. Citizens’ preferences for BI proposals may differ across countries because cultural differences and the economic and political conditions within each country may affect the configuration and preferences of the actors involved. In contrast, dimension (1) indicates that citizens’ support for BI proposals may inherently depend on the specific design of a BI proposal.

In the following sections, we use these two perspectives – the specific design of a BI proposal and the context within which it is introduced – to structure our theoretical discussion and the subsequent empirical analysis. First and foremost, the policy design perspective suggests that some characteristics inherent to BI proposals will affect the public support the proposals enjoy in a general way, i.e. quite independently of the political, cultural, or economic context they are introduced in. For this reason, we proceed by discussing the various elements of BI schemes and deriving hypotheses about how the specific design of BI proposals is related to their public support. Given that we have only two cases, we do not seek to formulate and test hypotheses based on the contextual perspective. However, discussing several characteristics of Finland and Switzerland helps us to present our two cases and form some expectations about the potential differences in BI support between the two countries.

The innovation of a basic income

A BI scheme mainly differs from typical welfare schemes in three respects (De Wispelaere and Morales, Reference De Wispelaere and Morales2016: 521 f.). First, BI schemes do not target households; rather, they are typically directly calculated and paid to an individual in the form of an income stream. Second, the coverage of BI schemes exceeds that of any other income support scheme. Third, and most importantly, in contrast to most welfare programs, BI is not contingent on employment or a person’s willingness to work.

However, the specific design of BI schemes can vary greatly (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004; Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014; Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004). De Wispelaere and Stirton (Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004: 267) provide a theoretical and conceptual discussion of the different dimensions and variants of BI proposals and they argue that empirical research on the subject should take this variety in BI designs into account (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004: 267). We make use of this recommendation at the individual level and assume that citizens’ support for a BI proposal is contingent on its specific characteristics, i.e. how exactly it is designed and what its goals are.

We thereby concentrate on the aspects of BI schemes that most directly influence the goals and implications of each scheme: namely, its universality, conditionality, uniformity, and adequacy (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004).Footnote 1 This choice reflects a recent shift in the discussions prevalent among proponents of basic income provisions, away from a rather normative debate on the welfare paradigm towards an evaluation of what the best or preferred variant of a BI scheme would be (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). Thus, at the citizen level, we identify three elements that help us differentiate between different BI variants: (1) the level of a basic income, (2) its degree of universality with respect to non-nationals, and (3) how the BI combines with other welfare schemes (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004).

(1) The level of a basic income

De Wispelaere and Stirton (Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004) have argued that BI proposals differ in their adequacy, i.e., the extent to which a BI proposal has the capacity to satisfy basic needs. This observation naturally raises the question how an appropriate level of BI is to be defined (ibid.: 271). A related question has to do with how BI schemes treat children (De Wispelaere and Morales, Reference De Wispelaere and Morales2016; Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004). Typically, most BI propositions set different levels for children and adults (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004). The discussion above makes it clear that the goals of each BI scheme can be quite different from those of others and, accordingly, the proposed BI levels can factor such differences in. In other words, the size of a BI depends on the goal of the possible reform. For example, the provision may be meant as a transfer guaranteeing subsistence at a low level or as an income that enables the development of those depending on the income. Moreover, other factors, such as the specific context (i.e. living costs, regional opportunities) in which the measure is introduced, will affect the level of BI. We can thus conclude that citizens’ preferences for a BI scheme will depend on the level of the basic income. However, formulating expectations about whether a more generous or a more limited BI will be preferred is not a straightforward task. Most importantly, the evaluation of these proposals will be strongly related to the goals attributed to the BI scheme. If such a program is conceptualized as an austerity measure, then a low-level BI should be preferred over more generous variants. Conversely, the opposite should be true if the BI scheme is considered as a means to compensate citizens for changing economic, and particularly labor market, conditions (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 35). Hence, we hypothesize that the level of a BI affects citizens’ evaluation decisively, but whether citizens – on average – prefer a high or a low level of BI is an empirical question:

H1: Preferences towards a BI scheme depend on the level of the payment.

(2) The degree of universalism with respect to non-nationals

According to De Wispelaere and Stirton (Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004), the degree of universality is another crucial feature of BI proposals. Universality is mainly concerned with coverage, i.e. the size of the population covered by the BI scheme. The crucial debate on this feature has to do with whether, and under what conditions, non-nationals (i.e. resident non-citizens) are eligible to receive a BI (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004). While the literature on welfare state provisions in general has repeatedly raised similar questions, the dilemma is even more pronounced when a basic income scheme is concerned (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006). Bay and Pederson (Reference Bay and Pedersen2006) have shown that Norwegian survey respondents’ support for a BI scheme significantly drops when they are explicitly informed that the scheme also includes non-citizens. This issue may be of particular importance in an “Age of Migration” (Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012) when questions of solidarity and deservingness (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006) and their relationship with support for the welfare state and anti-immigrant feelings are brought to the fore (Shutes, 2018; de Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2013; Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012; van der Waal et al., Reference van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, de Koster and Manevska2010). Recent studies in the field have found that increasingly, citizens tend to support more exclusive welfare state policies that treat nationals and non-nationals differently. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Citizens will prefer BI proposals that are more restrictive towards non-nationals compared to more universal proposals.

(3) Basic income and other welfare schemes

Another important aspect of BI proposals is whether a BI would replace or complement other social benefits, mainly social assistance and unemployment benefits. This issue relates to the distinction between proposals for a partial BI where the amount paid is not sufficient without an income from other sources, and offers of a full BI that would suffice to cover all living expenses (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 30). These different models go hand in hand with varying ideological views (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). Neo-conservatives have repeatedly asked for a single welfare state scheme, i.e. a full BI that would replace all other programs (and if paid at a rather low level, might result in lower overall social expenditures; Murray, Reference Murray2008: 2). In contrast, social-democratic forces argue that a (partial) BI scheme should always be accompanied by other types of social assistance (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004: 271). Based on these considerations, we hypothesize that citizens’ preferences towards a BI scheme will be influenced by whether and how other social assistance schemes will be affected by the introduction of a BI. Again, whether citizens in a specific context prefer one variant or another is an open question.

H3: Preferences towards a BI scheme are related to whether other not social benefits complement the BI.

A related question focuses on how a BI would be financed. Some authors argue that a BI may join other public expenses and be funded out of a pool of revenues collected from a variety of sources (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004: 10). Others think that a specifically earmarked funding source, such as a very broadly defined income tax or a massively expanded value-added tax, would be necessary, especially in the case of generous BI schemes (ibid.). As De Wispelaere (Reference De Wispelaere2016: 138) argues, the need for additional funding, and any potential increases in the value-added tax, in particular, may strongly reduce public support for a BI scheme. Conversely, Gingrich (Reference Gingrich, Kumlin and Stadelmann-Steffen2014) has argued that direct taxes on income or revenue are more salient to citizens than indirect taxes, such as VAT, for welfare policies in general. Thus, direct income and revenue taxes are perceived as costlier and more inescapable than indirect ones, and may therefore more strongly affect public support for BI proposals. Given the nuances of these findings, we formulate a general hypothesis:

H4: Citizens’ support for BI proposals depends on the type of funding undergirding the provision.

The influence of context

Various researchers have emphasized that the success or failure of a specific proposal and the definition of its crucial elements depend on the context in which the debate on BI occurs. For example, De Wispelaere and Stirton (Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004) have argued that support for BI schemes largely depends on the “surrounding policy context.” Similarly, Koistinen and Perkiö (Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 30) have emphasized the importance of cultural contingencies: a BI proposal must be in accordance with existing values, norms, and sensibilities. Moreover, a specific variant of a BI may have different real-world implications and effects in different contexts, depending on its interaction with already existing policies (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004).

Some researchers have argued that the high degree of solidarity and support for generous social protections in Scandinavian welfare states provide good conditions for the acceptance of BI schemes that rely heavily on solidarity and mutual trust (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006; De Wispelaere and Morales, Reference De Wispelaere and Morales2016). Conversely, in liberal and conservative welfare states, basic income schemes are typically perceived as a departure from the prevailing philosophy of social benefits based on means-testing or premised upon the idea that citizens must make contributions to the system before receiving social benefits. These perceptions could lead us to expect that citizens living in social democratic welfare states have different preferences toward the provision of a basic income and its design than citizens who live in less generous welfare state contexts. However, as several studies have emphasized, the strong work ethic underlying the Nordic welfare model and the belief that full employment and an egalitarian wage structure can be supported through a combination of adequate economic and labour market policies starkly contrast with the idea of unconditionality (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006; De Wispelaere and Morales, Reference De Wispelaere and Morales2016; Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014).

Moreover, the political goal behind a BI scheme and the way public debate is framed on the introduction of a BI scheme also affect how citizens evaluate the features of BI schemes (Chong and Druckman, 2007). The initiators of a BI scheme have agenda-setting power, because their proposal will define the perspective from which a BI scheme will be discussed and evaluated.

Thus, citizens’ preferences towards BI proposals may vary across contexts, mostly due to pre-existing welfare policies, but also if the framing of the actual and previous discussions on BI schemes differ considerably (see also Sloman, 2018). In other words, to account for this potential contextual heterogeneity, it is reasonable to test our hypotheses in different contexts. If the same preference pattern with respect to policy design can be found in such different environments, we could conclude that some characteristics inherent to BI schemes trigger public opposition or support.

Research Design

Based on these considerations about contextual differences and an unfamiliarity with the issue, our analysis focuses on two countries in which the idea of BI has recently been discussed in the broader context of their political process (see also Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014). More than anywhere else, in these countries the discussion of a BI is not hypothetical and utopian, but has opened a public debate on concrete proposals. These conditions are most advantageous to studying citizens’ preferences regarding BI schemes. At the same time, these two countries are significantly different from one another. Not only do they exhibit different pre-existing welfare policies, the framing of the current debate on BI also differs, as the following summaries of the state of discussion in these two countries illustrate. Relatedly, recent survey data illustrates that public opinion on the introduction of a BI scheme varies considerably between the two countries. Whereas in Finland, a majority of citizens tends to perceive BI favourably, the Swiss population ranks among Europe’s most skeptical about this provision, with a majority rejecting the idea of a BI (see Figure A1).

Since the 1980s, Finland has discussed several approaches to introducing a universal BI scheme using more than a dozen different models (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014). Although all the proposals to introduce a BI in Finland have so far failed to gain a political majority (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014), Finland would be a most likely case as far as the introduction of a basic income is concerned. Not only does the country have a long tradition of universal welfare policies, it has also witnessed a long-standing discussion of the idea of basic income in its academic and political discourse since the 1970s. Moreover, the idea has received support from important political, social, and academic actors. At the very beginning of these discussions, it was actors from the academic or left-green political field who launched initiatives in favor of a BI. More recently, the idea has received increasing support from larger political parties with different ideological backgrounds (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 35). The most recent example was a BI experiment announced by the center-right Finnish government in October 2015 that was intended to examine the effect of a BI on work incentives. In a first step that started in January 2017, 2,000 unemployed persons were randomly selected to receive a basic income of 560 Euros per month for a duration of two years (Kangas, Reference Kangas2016). This level of BI is lower than the unemployment benefits the participants had previously been entitled to, but the treatment group receives the money unconditionally for the whole two years, even if they find a new job during this period. Overall, the BI variant implemented in the experiment is more closely associated with a liberal perspective on BI than a progressive one.Footnote 2

In the course of preparing the experiment, population surveys revealed a relatively strong support for a basic income project, with 69% of respondents reporting that they were generally in favour of a basic income (Kangas, Reference Kangas2016: 9 f.). Voters from the Swedish People’s Party (SPP), the Green League, and the Left alliance were most sympathetic to the proposal for a BI, and the lowest support was found among voters of the National Coalition Party and the Christian Democrats. However, even in these latter groups of voters, supporters of BI were a majority. Interestingly, voters of the Social Democratic Party also exhibited high approval rates, despite the fact that their party leaders were more skeptical about the experiment.

In Switzerland, the issue was put on the political agenda by a popular initiative that sought to introduce a basic income scheme in Switzerland. A non-political committee supported by artists initiated the proposal for a BI, but only received weak support from the established political system. All major parties rejected the initiative, and the government feared the consequences that such a measure would bear on the economy and the social security system, arguing that a BI would greatly restructure the state and the economy. While the initiative did not explicitly define the precise design of the BI scheme, the initiators implicitly proposed a progressive form of a sizeable BI of about 2,500 CHF per month in their campaign activities and explanations. Although the popular initiative was rejected in the June 2016 ballot, roughly 23% of voters cast a “yes” vote, which is considerable given the low support that the initiative garnered among the political elite. Survey analyses carried out in the aftermath of the vote revealed that “yes” voters argued that inequality should be reduced and the relation between the economy and society should be rethought, whereas opponents of the proposal questioned its financial sustainability and assumed that people’s incentives to work would be reduced (Caroni, Reference Caroni2017; Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, De Rocchi, Kurer and Widmer2016).

Data

We collected the data used in the present study just after the national ballot vote on the BI initiative in June 2016 (Switzerland) and shortly after the publication of the Kela report in December 2016 (Finland) (Kangas, Reference Kangas2016). This timing implies that at the time of the survey, citizens’ awareness of the issue was as high as possible, and voters – at least and most clearly in Switzerland – had gone through an opinion formation process with respect to the idea of a BI. Roughly 1,000 individuals completed the survey in both countries. Survey participants were recruited from country-specific online panels through Qualtrics, and the demographic and structural composition of the final sample generally corresponds to the Swiss and Finnish resident populations (see Table A1 in the Appendix). The only exception to the general representativeness of the study is that older respondents are underrepresented in Switzerland, which might be caused by the use of online surveys.

The online survey included a series of standard socio-economic, socio-demographic, and ideological questions, but the core element was a conjoint module designed to capture individual preferences towards varying BI schemes. The following results are based on this module, which is explained in more detail in the following paragraph.

The methodological approach: A conjoint analysis

Methodologically, the present study follows Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) in using a fully randomized conjoint design. This technique has recently gained increased attention in the political science literature, but remains under-utilized in comparative welfare state research. More precisely, in this factorial survey experiment respondents rate different policy proposals that are described by six attributes (see also Liebig and Mau, Reference Liebig, Mau and Standing2004 for a similar approach). These attributes refer to the four dimensions of BI schemes discussed in the theoretical part: namely, the level of a basic income (for adults and children); the degree of universality with respect to non-citizens; and the interplay with other welfare schemes. An additional aspect that we consider has to do with the source of funding for the BI scheme. Note that indirectly we also integrate two of the more technical/administrative aspects of BI schemes but keep them constant (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). On the one hand, the size of the monthly payment implies that the presented BI proposals constitute income streams rather than stocks. Moreover, given that amounts are stipulated for both adults and children, the individual rather than the household is the standard unit.

The levels of these attributes are randomly varied to generate different BI proposals (see Table A2). Since each respondent was exposed to seven paired policy proposals – i.e. we had seven measurements per respondent – we were able to collect enough information on all varying attribute combinations.

Using this innovative research design has several advantages. First, in contrast to single-item questions (e.g. “Overall, would you be against or in favor of having a basic income scheme in your country?”), this survey type takes into account how the specific design of a BI influences support. As discussed in the theoretical discussion, BI schemes have “many faces.” Moreover, the dimensions of a BI scheme may be combined in different ways to shape the goals and the desired effects of the reform (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). Hence, preferences for BI proposals correspond to multidimensional choices – a specific proposal consists of various elements, some of which an individual may like and others reject. Therefore, conjoint analysis produces more valid and nuanced information on respondents’ preferences towards BI schemes.

Second and relatedly, previous research has shown that even though the idea of a BI has received quite ample popular support, concrete proposals are evaluated much more critically. This pattern has been attributed to the diversity observable in the design and orientation of the BI schemes (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004). This pattern fits the concept of “qualified support” (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Gray and Haggett2005; Dermont, 2018), whereby citizens may like the general idea of a BI, but oppose specific proposals for good and varying reasons (see also Noguera and De Wispelaere, Reference Noguera and De Wispelaere2006). A conjoint design enables us to take these qualifications into account by asking individuals to rate concrete proposals that indeed vary with respect to their design and orientation.

Third, since in the conjoint experiment we collect individual preferences on a series of varying BI proposals, we increase the comparability of responses across individuals but also across countries. To a certain extent, the design detaches individual responses from what these individuals “have in mind” due to the current debates in their country, since respondents are confronted with varying and potentially unfamiliar proposals. Better still, since we know the response corresponding to each concrete BI design, we can control for what respondents “had in mind” when providing their responses. This advantage may be particularly relevant when analyzing preferences towards new or hypothetical policies like the basic income. Regarding the latter, citizens have no real-world experiences and possibly limited knowledge that they can build their opinions upon. It is therefore relevant to specify potential trade-offs and contingencies into the survey questions.

To contextualize the stated preferences experiment, we explicitly asked respondents to envisage their decision as a hypothetical vote that would occur the following Sunday. For each paired policy variant, respondents had to indicate the likelihood that they would approve the proposed variant in a referendum on a scale from 0 to 100 percent in decimal steps. Although an experiment never has the same consequences as a real-world vote, and therefore, by definition, has its advantages mainly with respect to internal rather than external validity, we argue that the chosen conjoint design enables us to come as close as possible to measuring real-world support in a survey context. Providing the context of a ballot vote involves a behavioural component, i.e. it encourages respondents to think about real-world consequences and what they would do in such a voting situation. We admit that this framing is best suited for the Swiss study, where citizens are familiar with this kind of personal decision-making due to the frequency of direct-democratic ballots. However, when interpreting the results, we need to consider that the Finnish respondents were less acquainted with this voting situation.

Empirical Results

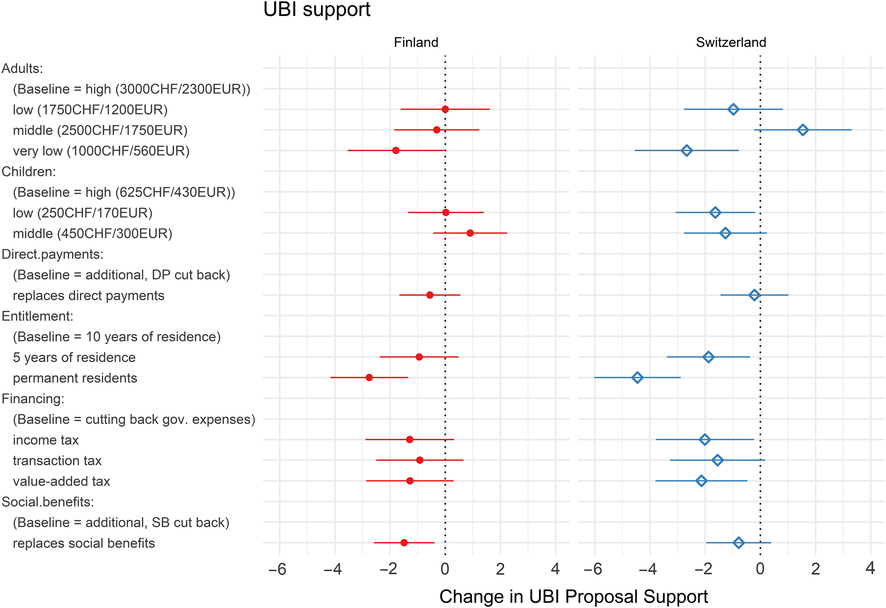

Our main interest is whether the characteristics of different BI proposals systematically influence the level of support they enjoy. For this purpose, Fig. 1 presents the average marginal component effects (AMCE) of the attributes characterizing a BI proposal. The AMCE represent the “marginal effect of an attribute averaged over the joint distribution of the remaining attributes” (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014: 10).

As Fig. 1 illustrates, the plots for the two countries have a similar pattern. The most consistent effect is the treatment of non-nationals. In accordance with our expectation (Hypothesis 2), the more restrictive a BI proposal is with respect to resident non-citizens, the more strongly citizens support it. Hence, this finding lends support to the view that concerns about solidarity and inclusion are increasingly important in welfare state debates in general, and may be of pronounced relevance as far as a basic income is concerned (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006).

However, not all variants of a BI require the same degree of solidarity. A generously designed BI implies stronger redistributive effects, and thus, an increased need for solidarity. In contrast, a BI conceptualized as an austerity measure may decrease society’s solidarity with the poor. This raises the question whether, against the backdrop of the findings about non-nationals, people prefer BI variants with a low level of redistribution and solidarity in general. Our estimations imply that this is not the case. Citizens in both countries prefer more generous variants of a BI to more limited variants. This pattern is particularly pronounced in Switzerland where a generous monthly basic income of 2,500 CHF garners the highest support. In the context of the popular initiative and campaign, citizens implicitly understood this to be the amount in the BI proposal, despite the fact that the actual text produced by the initiative did not explicitly mention it. Hence, our finding may point to the fact that public opinion was influenced by the variant most strongly present in the discussion. Accordingly, the preference for a generous variant of BI is also reflected in the level of payment meant for children. Conversely, in Finland, a high level of payment is less of a trigger for support. However, despite the government’s intention to test a BI in a rather liberal way, Finnish citizens also prefer more generous variants to their most restrictive counterparts. This finding is supported by both the conjoint analysis, i.e. the AMCE of policy attributes, and the individual-level results. Interestingly, in Finland, left-wing individuals also are most supportive of BI proposals, despite the current “liberal” approach. Thus, not only do our results confirm Hypothesis 1 that the level of payment influences preferences towards a BI, they also suggest that citizens in both countries are not sympathetic to a very minimalistic, liberal version of a BI, but rather prefer more generous, progressive proposals.

Given these findings, two other results are of particular interest. First, citizens exhibit higher levels of support for a BI that exists alongside other social benefits (Hypothesis 3). Proposals for a BI that would replace all other social benefits tend to receive lower levels of support (however, this AMCE is only significant in the Finnish case). It must be noted that the wording in the conjoint module did not specify what “other benefits” refers to. Based on the discussions that had taken place in the two countries, which had mostly focused on social assistance and unemployment benefits, we assume that respondents had these core benefits in mind, but probably not more specific benefits, such as payments during maternal/parental leave or family allowances. The potential replacement of direct agricultural payments – which must be seen as an issue peculiar to the Swiss caseFootnote 3 – does not affect our respondents’ evaluation of the proposals for a BI.

Moreover, and related to Hypothesis 4, citizens do not have clear preferences regarding the (potential) funding of a (generous) BI, but tend to prefer proposals that finance potential costs by cutting back other government expenditures. We interpret the limited importance of this attribute to mean that people believe the arguments advanced by the proponents of the Swiss initiative and the Finnish government: namely, that a basic income would be cost neutral or even allow for the government to save some of the funds currently financing alternative welfare schemes. In contrast, the likely trade-off between people’s preferred generous BI variants coesxisting along other social benefits and the tax levels required to make them sustainable seems to bear no impact on respondents’ opinion formation.

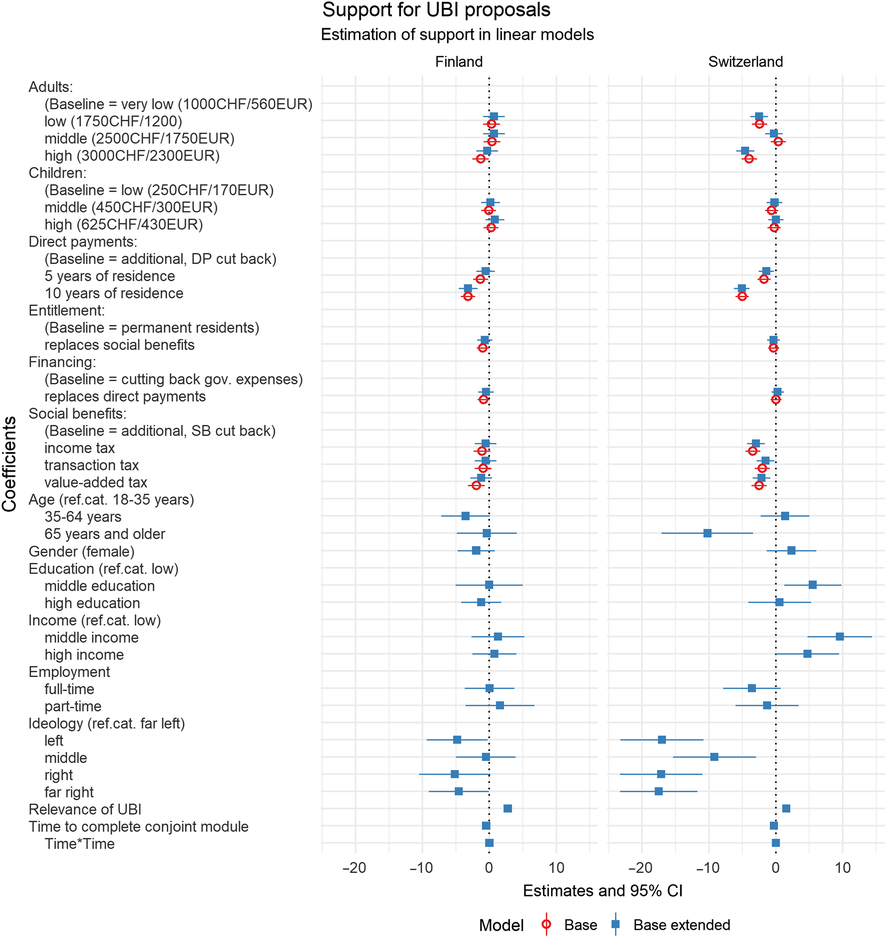

Overall, so far, our results indicate that the “qualities of the innovation itself” (Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014: 30), i.e. its policy design, are relevant to the level of citizen support that concrete BI proposals enjoy. Moreover, very similar preference structures with respect to the generosity of a BI scheme, the inclusion of non-nationals, and the combination of BI with other welfare state benefits can be observed in both countries, despite their many differences. Thus, whereas citizens in Finland and Switzerland may have different levels of general support for BI proposals (as documented in the eighth round of the European Social Survey), they tend to evaluate the different elements of a concrete BI scheme in a rather similar fashion. The idea of rather stable and generic individual preference structures receives further support from additional analyses in which we tested for group-specific preference patterns related to gender, age, income, education, and left-right placement. These models demonstrate that the different groups do not significantly vary in how they evaluate the various elements of our BI proposals, and that the previously described patterns are highly stable. The results across different ideological groups can serve as an example here (see Figure A2, and other models in the Supplementary Materials). Our results show that right-leaning individuals in both countries do not prefer a liberal, low BI that would be expected to be in line with their ideological background. Rather, if they prefer any form of basic income, they prefer it to be quite generous. In addition, left-leaning respondents who have repeatedly shown more openness towards immigrants prefer variants of a BI that are restrictive with respect to non-nationals, similar to the preferences of citizens from the political center and right. These findings corroborate the argument that some characteristics inherent to proposals for BI and their related logic are relevant to the support these proposals enjoy across citizens.

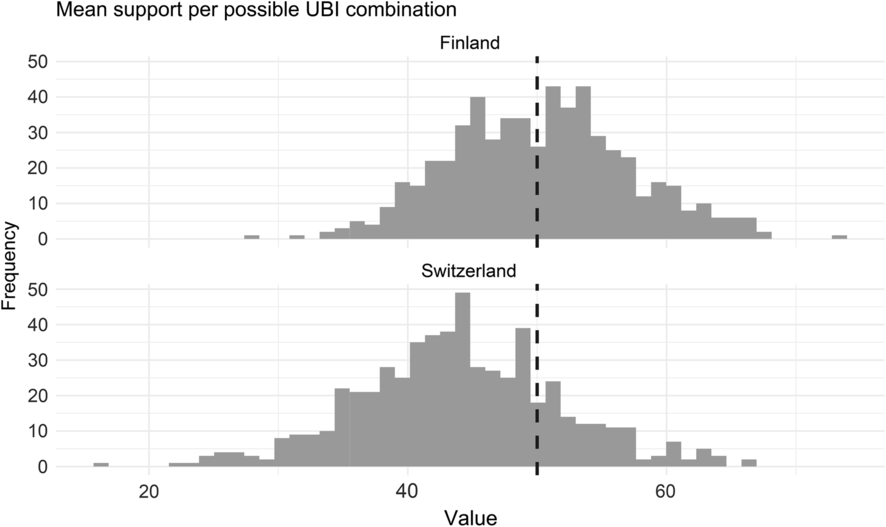

However, despite the fact that the preference structures associated with the preferred version of a BI scheme do not greatly vary across groups and contexts, the general level of support for BI proposals does vary. Figure 2 shows that support for BI proposals, measured as the mean probability of voting in favour of a respective proposal at the ballot, varies between the two countries (as well as across proposals, i.e. the different combinations of policy characteristics). In Switzerland, a majority of the hypothetical proposals received a mean support lower than 50%, which suggests that they would most likely be rejected rather than accepted. Only one in five possible proposals had a mean support over 50%. The respective share is considerably higher in Finland with 51% of all proposals garnering a mean support of over 50%. This suggests that Finnish citizens support more variants of a BI. This finding goes hand in hand with a higher general support for BI in Finland (50.2%, see Supplementary Materials) than in Switzerland where all possible combinations of a BI have a mean support of only 43.9%. Whereas we cannot directly compare these results to recent survey data from the European Social Survey, our findings lend further support to the idea that the single-item questions used in standard surveys may lead to an overly optimistic image of popular support for BI schemes. For example, according to the ESS data, a majority of Finnish respondents (rather) supports the introduction of a BI scheme in their country. However, our analysis suggests that such majority support is contingent on the design of the proposal and can only be expected for about half of all possible variants.

Relatedly, another country difference concerns the association between individual-level characteristics and the level of support. The inclusion of further individual-level variables in the hierarchical model in addition to the various policy attributes already included reveals that these personal characteristics are much more strongly related to BI support in Switzerland than in Finland. Whereas in Switzerland the observed pattern confirms that left-wing voters and individuals with low income and education are the strongest proponents of a BI, very few individual charateristics are significantly related to support for a BI in the Finnish sample.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated citizens’ attitudes towards the idea of a basic income, and most importantly, whether both the specific design of a BI scheme and also the context in which it is proposed impact the level of support it enjoys. Using conjoint experiments, we tested our hypotheses in Finland and Switzerland – two countries in which citizens have recently discussed the introduction of a basic income scheme most intensely and where important differences related to existing welfare policies and the framing of the BI debate exist.

Our main finding suggests that whereas the general levels of support for BI proposals in Finland and Switzerland differ, preferences for policy design are highly consistent both across these countries and across social and ideological groups within them. This result implies that the fundamental logic of specific BI proposals – in particular, the liberal or progressive goals behind them and the treatment of non-nationals – generates quite general individual reactions that are independent of context. More precisely, our conjoint analyses reveal that citizens in both countries do not support the idea of a liberal BI income that could serve as an austerity measure for welfare state retrenchment and restructuring. Instead, they tend to favour more generous schemes that do not totally replace, but rather complement, other social benefits. Moreover, the most consistent cross-country trigger of support for a BI proposal is a restrictive access for non-nationals. This finding may point to one of the crucial challenges to the introduction of a BI. In the “Age of Migration” (Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012), questions of solidarity and deservingness (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006) as well as their relationship with support for the welfare state and anti-immigrant feelings have gained increased prominence (de Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2013; Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012; van der Waal et al., Reference van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, de Koster and Manevska2010). The well documented dilemma between citizens’ demands for generous welfare state benefits for those in need and their preference for limited benefits for migrants may be of even higher relevance as far as a BI is concerned. Another challenge to the introduction of a BI scheme seems to relate to its funding. Our results suggest that, just like many proponents of BI schemes, citizens like to assume that a BI could be financed without levying new or additional taxes. Although this possibility is very unlikely for the generous variant citizens prefer, respondents do not seem to fully engage with this potential trade-off when forming their opinions on different BI variants.

Nevertheless, the comparison between Finland and Switzerland provides interesting insights. As previously mentioned, in general Finnish respondents are more sympathetic to BI schemes. Theoretically, this finding confirms the argument that the status quo affects the level of support for reforms such as the introduction of a BI. In particular, in Switzerland a BI would contrast with existing policies more starkly than in Finland, where welfare policies have been characterized by the principle of universalism for a long time (Bay and Pedersen, Reference Bay and Pedersen2006; De Wispelaere and Morales, Reference De Wispelaere and Morales2016). In this vein, the experimental approach corroborates the general pattern found in recent ESS data, the most comprehensive comparative data available on European support for a BI. However, it cautions against a potential pitfall of using these data. It suggests that general survey questions tend to overstate actual popular support because they miss important qualifications on individuals’ support. Moreover, the individual characteristics of respondents are more influential in explaining support for a BI in Switzerland than in Finland. Similarly, in Switzerland, preferences for the design of a BI scheme seem to reflect the current debate more strongly, whereas in Finland, the dominant liberal activation frame does not factor into citizens’ preferences. These country differences may imply that citizens’ attitudes and preferences towards BI proposals may also depend on the status quo (i.e. existent welfare states) and the differing political systems and processes at place in the countries considering the introduction of this scheme.

The latter conclusion points to one of the limits of our study. Whereas we have argued that the comparison of Switzerland and Finland might provide a better understanding of how differences in current welfare systems influence attitudes towards BI proposals, our study’s potential in providing a complete picture of these dynamics eventually seems limited. When comparing only two countries, it is difficult to identify systematic differences in general. The present analysis suggests that the difference in our respondents’ previous engagement with the BI issue (e.g. having thought about and made a decision on a specific initiative on a ballot vs. having potentially followed a rather academic and administrative debate without much personal involvement) may have hampered comparability. This limitation entails several implications for future research on BI, in particular, and social policy reforms, in general. First, when approaching individual attitudes towards the welfare state from a comparative perspective, future studies need to consider that citizens’ roles in reform processes will vary. Whether citizens are directly involved as veto players, or not, may not only affect the real-world reform process but could also influence what they tell us in a survey. In Switzerland, shortly after the vote, citizens were able and willing to differentiate between different proposals. In contrast, in Finland, the weaker associations between policy (and individual) characteristics and preferences for BI proposals may be a reflection of the administrative and academic nature of the debate, in which regular citizens were much less involved. Moreover, expanding a study like ours to additional and more diverse country contexts will surely be relevant to learning more about how current welfare arrangements affect public opinion on future welfare state models and reforms. In particular, an interesting question has to do with whether differences in the general level of support for programs can also be observed across countries belonging to different welfare state models, while preference structures – i.e. individual reactions to crucial dimensions of the welfare state measures, such as the degree of universality, the level of redistribution, or costs and funding – are stable across contexts.

Acknowledgements

We thank discussants and participants at the 2017 General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) in Oslo and at the 2018 Annual Conference of the Swiss Political Science Association (SPSA) in Geneva for their remarks on this work and Ana Petrova for linguistic assistance.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000412

Appendix

Figure 1. Policy attributes and the probability of support. Note: Average Marginal Component Effect (mean and 95% confidence interval). Full results can be found in the supplemental material.

TABLE A1. Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Figure 2. Mean support for UBI proposals. Distribution of the mean support per concept. A concept is a specific combination of policy characteristics.

TABLE A2. Attribute List and Levels Used in the Conjoint Analysis

Figure A1. Attitudes towards a basic income scheme in Europe. Source: ESS 2016, round 8.

Figure A2. Conjoint analysis contingent on ideological group. Note: AMCE by ideological groups, separately estimated results for Finland and Switzerland.