I

The Historia Augusta has yet to yield its secrets.Footnote 1 Despite more than a century of intensive work on the pseudonymous collection of imperial biographies, from Hadrian to Carus and his sons, ostensibly written by six different authors under Diocletian and Constantine, basic facts about the work remain in contention. Since Hermann Dessau's fundamental study in 1889, almost everyone agrees that it was written by a single author in the later fourth century.Footnote 2 But when exactly was it written, by whom, and (most importantly) to what end? What is the purpose of its elaborate and fantastical frame, and what is the relationship of truth to fiction in its enterprise? Why does it have a large gap, the ‘great lacuna’, between Gordian III and Valerian, where there ought to be the lives of such undoubtedly important emperors as Phillip the Arab and Decius? Is it another authorial conceit? Such questions have attracted voluminous and often stormy debate. In comparison to the effort spent pursuing these puzzles, less attention over the past century has been paid to investigating the text. On this subject, a century-long consensus has been reached, as represented in Hohl's 1927 Teubner edition and the ongoing multi-editor Budé edition: the most authoritative source is a ninth-century manuscript alleged to have been written in Italy, BAV Pal. lat. 899 (P), which generated almost the entire tradition including two important copies, the ninth-century Bamberg Msc. 54 (B), from Fulda, and the early fourteenth-century Paris lat. 5816 (L), later owned and annotated by Petrarch.Footnote 3

The only possible exception to this broad dependence on P is a heavily interpolated and lacunose group of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century manuscripts dubbed Σ, which some have claimed is descended from a distinct tradition.Footnote 4 Σ poses particularly difficult challenges. It offers countless small corrections to minor corruptions in P as well as significant bits of non-P text, especially in the Life of Aurelian. However, it also often provides no help where P is most corrupt and an independent source would offer the greatest assistance. This fact led Susan Ballou, in her seminal study in 1914 on the manuscript tradition of the HA, to conclude that Σ is simply derived from P.Footnote 5 Unfortunately, her analysis rested on an erroneous dating of the correcting hands in P, and is not credible in the terms in which she proposed it.Footnote 6 Nonetheless, her essential insight (building on a suggestion by Hermann Peter), that Σ does not perform the role that we would expect of a manuscript independent of P, remains valid.Footnote 7 Examples of this can be seen in the lacunose passages in the Lives of the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni. Consider just one of them (Gal. 1.1). Here P is so lacunose as to offer little in the way of sense:

exercitus mu…………………….duces erat…………………….

meror……………….imperator…………………………in persida

……………………………………………………ior omnium…..

quod gallienus na……………….paterfactosic……………………/ (P, f. 154r)

This kind of lacuna arises from copying a damaged exemplar where the scribe attempted to represent graphically the characters he could pick out with a rough approximation of their place in the line.Footnote 8 Σ merely stitches together the loose ends in P to extract some modicum of sense, omitting everything too corrupt to fix:

exercitus murmurabant duces erat omnium meror quod imperator romanus in persida serviliter teneretur.Footnote 9

We would expect a tradition wholly independent of P to offer text which could explain the fragments in P and generally respect the lengths of the lacunae left by P's scribe. Σ offers no such text. Hence, even if Σ must have some elements independent of P, it seems still closely restrained by P's limitations.

In this study, I will argue that that a different strand of the manuscript tradition can be gleaned from a fifteenth-century edition of the text printed in Venice, reintroducing a theory first proposed in 1904. By comparing its textual innovations against P with a fourteenth-century historian, Giovanni Colonna, I will show that the tradition represented in that edition must go back to more than a century before print. I will then introduce a new manuscript of two lives in the HA which offers a text independent of P and Σ, but instead represents the source of Colonna and the Venice edition. This discovery will shed new light not only on particular problems in the text of the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni — and tell us something new about the historian Dexippus — but also on one of the most curious and controverted features of the whole collection, the great lacuna between Gordian III and Valerian, covering the emperors during the momentous decade between 254 and 264.

II

In 1904, Edwin Patzig proposed a possible new source for the text of the HA, the second printed edition, produced in Venice in 1489 at the undistinguished house of Bernardino di Novara.Footnote 10 This edition contains five additions of a sentence or more in the Lives of Alexander Severus, Maximus and Balbinus and the Two Valerians.

A. After Alex. 68.1 amplissimus: Pomponius legum peritissimus, Alphenus, Aphricanus, Florentinus, Martianus, Callistratus, Hermogenes, Venuleius, Triphonius, Metianus, Celsus, Proculus, Modestinus: hi omnes iuris professores discipuli fuere splendidissimi Papiniani, et Alexandri imperatoris familiares et socii, ut scribunt Acholius et Marius Maximus

Pomponius, the most expert lawyer, Alphenus, Africanus, Florentinus, Martianus, Callistratus, Hermogenes, Venuleius, Triphonius, Metianus, Celsus, Proculus, Modestinus. All of these jurists were students of the most famous Papinian, close friends and companions of the Emperor Alexander, as Acholius and Marius Maximus record.

B. After Max. Balb. 15.7: nec reticendum est quod Maximus cum et sibi et Balbino deferretur iudicio senatus imperium Balbino dixisse fertur ut Herodianus dicit: ‘quid tu Balbine et ego merebimur cum hanc tam immanem belluam exitio dederimus?’ cumque Balbinus dixisset ‘senatus populique Romani feruentissimum amorem et orbis terrarum’ dixisse fertur Maximus: ‘uereor ne militum odium sentiamus et mortem’.

Nor should we be silent about what Maximus reportedly declared to Balbinus when the Empire was passed to him and Balbinus by the judgement of the Senate, as Herodian relates: ‘Balbinus, what will you and I earn by destroying this savage monster?’And when Balbinus said, ‘The warmest regard of the Senate and the Roman People, and the whole world’, Maximus reportedly declared, ‘I fear that we will experience the hatred of the soldiers — and death.’

C. After Max. Balb. 18.2: sed Fortunatiano credamus qui dicit Pupienum dictum nomine suo, cognomine uero paterno Maximum ut omnium stupore legentium aboliti uideantur

But I should give credence to Fortunatian who says that he was called Pupienus as his own name, but Maximus from his father's cognomen, so that . . . [the last phrase is corrupt].

D. and E. Two passages in Val. discussed below

Besides these lengthy supplements, there are multiple additions of several words, such as at Max. Balb. 3.4 and Gal. 16.1. Most significant of all the 1489 edition's features is its version of the Lives of the Two Valerians. The life in ed. Ven. begins with a line nowhere to be found in the P or Σ traditions, which then proceeds directly into the vulgate Val. 5.1 cuius:

Valerianus imperator, nobilis genere, patre Valerio, censor antea, et per dignitatum omnes gradus suis temporibus ad maximum in terris culmen ascendens (Val. 5.1) cuius per annos …

The Emperor Valerian, of noble birth, his father Valerius, a censor beforehand, who climbed through every rank of office in due course up to the highest pinnacle on earth …

After this comes Val. 5.1 through 7.1 superatus est, followed by another paragraph not in P:

Victus est enim a Sapore rege Persarum, dum ductu cuiusdam sui ducis, cui summam o bellicarum rerum agendarum commiserat, seu fraude seu aduersa fortuna in ea esset loca deductus ubi nec uigor nec disciplina quin caperetur militaris quicquam ualore potuit. Captus igitur in dicionem Saporis peruenit, quem cum gloriosae uictoriae sucessu minus honorifice quam deceret elatus superbo et elato animo detineret seque rursum Romanorum rege ne uili et abiecto mancipio loqueretur. Litteras ab amicis regibus qui et ei contra Valerianum fauerant plerasque missas accepit, quarum seriem Iulius refert.Footnote 11

We then at last arrive at what is now Val. 1.1, which continues up to 5.1 Valeriano before proceeding to 7.1 nunc.

To put it another way, what we see is the long passage from Val. 1.1 to 5.1 Valeriano transposed from the beginning of the life to the middle, with the addition of top and tail passages not in P. Patzig argued that there is no reason to doubt the authenticity of the missing passages, and that the deviant arrangement of the Two Valerians in the ed. Ven. offers a better parallel structure to the Life of Claudius than the arrangement in P, Σ and the modern editions.Footnote 12 Hence, he concluded, we should see the text of the ed. Ven. as offering the testimony of some lost manuscript independent of P. This should not not have been especially controversial: there is a lengthy passage of over 500 lines found in all the manuscripts but omitted by mistake in the editio princeps, which stretches from the end of the Quadriga tyrannorum through the first four sections of the Life of Carus (Quad. tyr. 15.10 et Numerianum … Car. 4.7 si ita est). Since this passage is found in the ed. Ven., and not the editio princeps, it must have been using some manuscript source.

Patzig's daring and original hypothesis did not go unnoticed. Hermann Peter, at the time the most recent editor of the HA, replied with a damning rebuke several years later.Footnote 13 He argued that, in fact, the structure of the Two Valerians in P more closely mirrored that of the Claudius and that the additions in the ed. Ven. could be paralleled elsewhere in the extant text. For example, Peter points out nobilis genere and censor antea in the first Val. passage is paralleled by Val. 5.7 censorem … nobilis sanguine. But the situation is not nearly so clear elsewhere: patre Valerio, for example, would seem to offer unique information about Valerian's father, but there is Probus 5.2: Valerium Flaccinum, adulescentem nobilem, parentem Valeriani. In the HA, parens means ‘kinsman’ and not ‘parent’, including in a passage just a few lines later (Probus 6.2) where parens is contrasted with pater. Hence, patre Valerio could be giving us ‘authentic’ information, true or not, or it could simply be a misunderstanding of the line from Probus. More difficult would be dignitatis omnes gradus … ad maximum in terris culmen which uses the authentic late antique terminology of ascent through dignitates to the maximum culmen, and necessarily implies that Valerian had already held a consulship, which is true, and not a widely disseminated fact.Footnote 14 Peter's rebuttal was unfair and ultimately unconvincing: leaving aside the exegetical question of the structure of the Claudius, the fact that the additions parallel material elsewhere in the HA could just as well be considered a testament to their authenticity, since the work as a whole is nothing if not repetitive. He failed to even mention the fact that the ed. Ven. must have had a manuscript source, as we can see from its printing of the missing passage in the Life of Carus, rendering his conclusion particularly flawed:

Jedenfalls ist die Hoffnung hier eine von P unabhängige Quelle der Überlieferung entdeckt zu haben fehlgeschlagen, und das Suchen nach einer solchen wird fortgesetzt werden müssen.Footnote 15

Peter's prestige carried the day, despite the weakness of his rebuttal. His successor as editor of the HA, Ernst Hohl, in 1913 made up for these weaknesses with a detailed examination of the ed. Ven., concluding that its readings, where it varied from the manuscripts, were the result purely of conjecture. As a consequence, Patzig's theory would have to wait more than a century for vindication.

In 2016, Rino Modonutti published a sensational discovery, that the lengthy list of jurists transmitted after Alex. 68.1 only in ed. Ven. can be found, almost entire and in the same context, in the Mare historiarum, a universal history written by a Dominican scholar Giovanni Colonna around the middle of fourteenth century.Footnote 16

Quorum primus et principalis fuit famosus ille Ulpianus, famosissimus iuris consultus, Fabius Sabinus, Cato sui temporis, Helius Gordianus, Iulius Paulus iuris consultus, Clodius Venacius qui fuit e aetate orator amplissimus, Pomponius iuris consultus, Africanus, Calistrathes, Hermogenes, Venuleius, Triphonius, Metianus, Celsus, Proculus, Modestinus, hii tres omnes iures consulti, Cathilius Severus. (ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 242)

Of these, the first and foremost was the famous Ulpian, a most famous jurisconsult, Fabius Sabinus, the Cato of his day, Helius Gordianus, Julius Paulus the jurisconsult, Clodius Venacius, who was the most renowned orator of the age, Pomponius the jurisconsult, Africanus, Callistrates, Hermogenes, Venuleius, Triphonius, Metianus, Celsus, Proculus, Modestinus, these three all jurisconsults, Catilius Severus.

Those listed above in italics are found only in the ed. Ven., and as Modonutti concludes, demonstrate that the tradition of the Historia Augusta in the fourteenth century is considerably more complex than has been supposed. Indeed, Modonutti goes on to show, some of the jurists only found in that list are also mentioned in the Historia imperialis of Giovanni de Matoci (†1337), the mansionarius of Verona who made substantial corrections to P, and the De viris illustribus of Guiglielmo da Pastrengo (†1362).Footnote 17

Modonutti did not, however, extend his inquiry to the other added passages in the ed. Ven. In the Life of Valerian, Colonna clearly had a text which began like the ed. Ven. with the same sentence. Since, Modonutti's edition only extends to Alexander Severus, I quote from the autograph manuscript (Florence, BML MS Edili 173):Footnote 18

Edili 173, f. 194r: Fuit autem hic Valerianus genere nobilis patre Valerio, et qui per omnes dignitatum gradus ad imperium venit.

Venice 1489, beginning of Val.: Valerianus imperator, nobilis genere, patre Valerio, censor antea et per dignitatum omnes gradus suis.

Edili 173, f. 194v: ubi nec uigor nec disciplina militaris nihil sibi ualuit

Venice 1489, after Val. 7.1: ubi nec uigor nec disciplina quin caperetur militaris quicquam ualore potuit.

We can also confirm this on the basis of individual readings, if we look particularly at the passage in the Life of Carus where the ed. Ven. is the editio princeps.Footnote 19

1.2 senatus et populi post sententia Ven. Colonna : senatus ac populo post gubernacula P Σ

1.3 e om. P hab. Σ Ven. Colonna

2.3 regione P1 religione PL Ven. Colonna

2.5 quadam P quodam Ven. Σ Colonna

2.5 tumebat boni P timebat boni Σ tunc boni habuerat Ven. tunc boni habuerit Colonna

3.3 ni his P (in his L) nihil Ven. Σ Colonna

3.4 ad om. P1 hab. PL Σ Ven. Colonna

Patzig's intuition was entirely correct. The ed. Ven. of 1489 must be based on a manuscript source which goes back more than a century to a time in which the HA was barely known and very few manuscripts existed. There is no other explanation which can account for its agreement with Colonna. It could not have been interpolated from the Mare historiarum because Colonna shows awareness of the additional passages, but does not always reproduce them in full. Indeed, in the case of the second addition in the Val., he uses less than one sentence of the text.

One must, however, introduce a complication. The ed. Ven. was based on the editio princeps, printed at Milan in 1475. The Milan edition was based (directly or through an intermediary) on two sources: a mid fourteenth-century copy of P, Paris lat. 5816 (L), which was subsequently owned and annotated by Petrarch, and an unidentified Σ manuscript.Footnote 20 The proofs of its primary derivation from L are legion. One noteworthy case is in Maximus and Balbinus 16.2–3:

Maximus, quem Pupienum plerique putant, summae[t] tenuitatis sed uirtutis amplissim <a>e fuit. sub his pugnatum est a Carpis contra Moesos. fuit et Scyt <h>ici belli princip um, fuit et Histriae excidium eo tempore, ut autem Dexippus dicit, Histricae ciuitatis. (Hohl 2.70; P, f. 151r)

Maximus, whom most people think is Pupienus, was of extremely modest means, but of great virtue. Under them, there was a war of the Carpi against the Moesians, and the beginning of the Scythian war, and the fall of Istria at the same time, or as Dexippus says, the Istrian city.

The scribe of L made a saut du même au même error, confounded by the repetition of fuit.

Maximus quem puppienum plerique putant summe extenuitatis sed virtutis amplissime fuit. et scitici belli principium fuit. et hystrie excidium eo tempore. Vt autem dexippus dicit hystrice civitatis. (L, f. 71r)

This omission is reproduced in the Milan edition.

Maximus quem Pupienum plaerique putant: summe extenuitatis sed virtutis amplissimae fuit: & scithici belli principium fuit & histriae excidium eo tempore. Vt autem Desippus dicit Histricae civitatis. (unpaginated)

Such an error is very unlikely to arise independently, and Ballou has amassed considerable other evidence that L is the ultimate origin of the editio princeps of 1475.Footnote 21 This same omission is found in the ed. Ven. Yet another example can be seen in the lacunose passage in Gal. 1.1 discussed above. The editio princeps presents the Σ text unaltered, and the ed. Ven. prints the same with the addition of a single word.

exercitus murmurabant duces erat (add. ingens Ven.) omnium meror quod imperator romanus in persida serviliter teneretur

Beyond dramatic instances like these, the same conclusion can be reached by just a cursory glance of the hundreds of readings in which the ed. Ven. agrees with the editio princeps against both P and Σ.Footnote 22 Hence, the text of the ed. Ven. is an amalgamation of the editio princeps with the unknown manuscript source, and cannot be considered by itself an uncontaminated witness to that source.

In a similar way, Colonna's Mare historiarum is not a text of the HA, but an original historical work. Even though it is very likely that Colonna only had one manuscript of the HA, we cannot suppose that Colonna did not alter, supplement and paraphrase as he saw fit. So neither the ed. Ven. nor Colonna on their own can be considered a sure guide to the lost tradition of the HA, but the ed. Ven. only where it disagrees with the editio princeps in a significant fashion (that is, excluding the typographic solecisms to which the printer was especially prone), and Colonna only where he agrees with another source for the text of the HA. To make full and efficacious use of this tradition, we would want a manuscript of the HA itself of the sort that Colonna and the Venice editor had recourse to.Footnote 23 Such an uncontaminated witness to this tradition does indeed survive, at least for two of the lives, in a previously unexamined fifteenth-century manuscript now in Erlangen.

III

Erlangen, Universitätsbibliothek MS 647 (E) is a manuscript on paper, consisting of fifty-nine folios, written in the later fifteenth century. It contains:

f.1br: Lorenzo Valla, de libero arbitrio, inc. Maxime vellem, Garsia Episcoporum doctissime … Ends imperfectly (106, p. 49 Chomarat), f. 15v: multum ad corroborationem fidei fidei [sic]. Ed. J. Chomarat, Lorenzo Valla. Dialogue sur le libre-arbitre, Paris, 1983.

ff. 16r–22v: Blank.

f. 23r: Letter of Bishop Johan von Eich to Bernhard von Waring, prior of Tegernsee, inc. Iohannes dei gratia Sancte Aureatensis alias Eystetensis episcopus religioso et docto monacho fratri Bernardo priori Sancti Quirini in Tegernsee … f. 36r: per infinita secula seculorum. Amen, with FINIS added in a later hand.

ff. 36v–38v: Blank.

f. 39r: Historia Augusta, Lives of the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni, inc. (rubr.) Trebellii pollionis liber Valerianus pater et Valerianus filius incipit feliciter. Valerianus imperator patre Valerio censor antea et per dignitatum omnes gradus suis temporibus ad maximum in terris ascendens cuius per annos … f. 52r: mimis scurrisque uixisse. The beginning of the main text begins with a crude four-line initial V in red, with the main text following in the customary brown ink.

ff. 52v–57v: Blank.

f. 58r: Giovanni Antonio Campano, letter to Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini, without heading, greeting or attribution, inc. Centum xxxvi Quintiliani declamationes ad te nuper e germania missas … f. 59r ignorem futurum. See the Rome (not Venice) 1495 Opera omnia of Campano, printed by Eucharius Silber, ff. 63v–64v.

f. 59v. Blank.

Besides these existing texts, the first folio (f. 1r) contains a list of contents indicating that a number of texts has been lost, including Cornelius Tacitus, De situ Germanorum and Daretes [sic] Frigius before the HA lives and Quaedam super tragedias Senece after. Beneath this list of contents comes the name Iohannis Mendel. The list of contents is in Johan Mendel's hand, as Mariarosa Cortesi has shown.Footnote 24 Mendel was a canon of Regensburg, and provost in Eichstätt under the same Bishop Johann von Eych who wrote the second item. He died in 1484, which gives us an absolute terminus ante quem for the volume.Footnote 25 None of the items, however, postdate 1471, and there is very good reason to fix its writing around that date.

The key to understanding the second part of this miscellany perhaps lies in the last item, the letter of Giannantonio Campano. I know of no other manuscript copies of Campano's letter (and the copy here is textually superior to that which eventually appeared in print).Footnote 26 It is almost certainly written in his hand — compare the letter in ASV Armarium t. 10, f. 209rFootnote 27 and the fragmentary biography of Federico da Montefeltro in Urb. Lat. 1022 which has been claimed to be part autograph. The fact that it contains no salutation, valediction or attribution may well mark it out as a work in progress. While the section from the HA which precedes the letter is in a different hand, we have other reasons to connect earlier items in the volume with Campano. First, he is well known as a reader of Tacitus’ Germania, which he used extensively in an oration he composed for the Diet of Regensburg (but never delivered), in which he appealed to the pristine nobility and virtue of the Germans.Footnote 28 Second, the volume is wrapped in a parchment sheet containing curial documents, including one issued at Siena in 1460 (when it is known that Campano was in Siena) dealing with affairs in Münster and Bratislava. Hence, it seems as if the second half of the original volume, from Tacitus to the end, belonged originally to Campano, and Mendel added the text at the beginning when the volume came into his possession. What is interesting is that the manuscript seems to be a German production and to have remained in Germany since being written: it is not merely associated with Campano, but is a relic of his German adventure, whose destination was none other than Regensburg. As a canon of Regensbug, Mendel may well have attended the synod, which could explain how the volume ended up in his possession. To find a connection between Campano and Mendel is not wholly surprising: Mendel's friend Johann Tröster was an intimate of Enea Silvio Piccolomini (the future Pope Pius II), patron of Campano and the dignitary in whose retinue he travelled to Regensburg, as was Mendel's bishop Johann von Eyck.Footnote 29

As a working hypothesis, then, the text of HA in the Erlangen manuscript was discovered somewhere in Germany by Campano. After all, as a good fifteenth-century humanist, he filled his free hours with manuscript hunting.Footnote 30 Somewhere in Germany he found the old manuscript of the Minor Declamations documented in the final item in the Erlangen volume. He found another containing a relatively rare patristic text, Victorinus’ De generatione diuini uerbi (more commonly known as Ad Candidum Arrianum), written litteris peruetustis, which he sent to Pope Sixtus IV, with a letter:

Cum nonnullas Germaniae bibliothecas nuper euoluerem, libellum inueni litteris quidem scriptum peruetustis, uerum situ atque puluere ita consumptum, ut iam legi uix, nisi magna cum diligentia, posset.Footnote 31

Recently when I was browsing several German libraries, I found a little book written in very old script, but so worn away by mould and dust, that it could scarcely be read, save with great concentration.

Another old manuscript, whose contents he does not identify, was sent to Alfonso of Aragon, with a letter containing a lively description of these libraries and their (unappreciated) contents: ‘a great abundance of extremely old books is found in all of Germany’ (magna copia librorum vetustissimorum in tota Germania est.)Footnote 32 Hence, even if we do not know what monasteries Campano visited, it is entirely plausible that he visited one with an old HA manuscript.

This could also explain why the manuscript only contains two lives. Following this reconstruction, Campano would not have had much time for copying or having copies made, as his party was either travelling on to Regensburg on a fairly tight schedule, or he was still in the cardinal's service at the Diet, or they were rushing home after the death of Pope Paul II.Footnote 33 The first thing any sensible person looks for in an unreported manuscript of Juvenal is the ‘Oxford lines’, thirty-four lines interposed in the Sixth Satire, preserved ‘only in a single manuscript of average quality’.Footnote 34 In the same way, anyone who knew anything about the HA would immediately have searched to see if the great lacuna was filled. Failing that, the next thing to check would be the state of the lacunose passages in the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni. Campano was not just a poet and diplomat, but a keen student of Roman history, who oversaw the editio princeps of Suetonius (Rome, 1470). He certainly would have been familiar with the HA, known exactly where to look and which sections he would want copied if necessity forced him to be selective. That would explain why we have only those two lives.

Campano would have found much to excite his interest. To begin with, the title in the very first line. One exceptional feature of the Life of the Two Valerians in the ed. Ven. (which Patzig did not remark upon) is the title and attribution. Unlike P, Σ and the editio princeps, it attributes the Lives of the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni explicitly (and ‘correctly’) to Trebellius Pollio. These lives had previously been attributed to a different one of the six HA authors, Capitolinus, due to a codicological problem in P's archetype. The Two Valerians is the first life after the great lacuna and is imperfect at the beginning. On f. 152r of P, what we find is the end of the Lives of Maximus and Balbinus and the imperfect beginning of the Lives of the Two Valerians, with the following explicit — incipit:

maximus sive pupienus et balbinus iuli capitolini explicit

incipit eiusdem valeriani duo

What must have happened is the loss of the previous lives explicitly attributed to Trebellius, and hence eiusdem was misinterpreted to mean Capitolinus and not Trebellius Pollio. This directly inspired the simple title Eiusdem Valeriani duo in the editio princeps. In the ed. Ven. we find quite a different title, with the ‘correct’ attribution to Trebellius Pollio: Trevelii Pollionis Valerianus pater & filius. Given that the beginning of the Two Valerians is different in the ed. Ven. and derived from its lost manuscript source, we should presume that this strand alone preserved the name of the ‘genuine’ — if that term has any meaning in discussing the attribution of HA lives — author of the life.

This is almost precisely the title found in the Erlangen manuscript (f. 39r): Trebellii pollionis liber Valerianus pater et Valerianus filius incipit feliciter.Footnote 35 Since the Erlangen manuscript (which I will call E) predates the ed. Ven. by some two decades, this must be our earliest witness of the attribution of the Two Valerians to Trebellius.

The text that follows is the same as found in the ed. Ven.:

Valerianus imperator, nobilis genere, patre Valerio, censor antea, et per dignitatum omnes gradus suis temporibus ad maximum in terris culmen ascendens (Val. 5.1) cuius …

After 7.1 superatus est, we find the same passage as in the ed. Ven. albeit in a less corrupt form:

Victus est enim a Sapore rege persarum, dum ductu cuiusdam sui ducis cui summam omnium bellicarum rerum agendarum commiserat, seu fraude seu aduersa fortuna in ea esset loca deductus ubi nec uigor nec disciplina quin caperetur militaris quicquam ualere potuit Captus igitur in dicionem Saporis peruenit, quem, cum gloriosae uictoriae sucessu nimis honorifice quam deceret elatus, superbo inflatoque animo detineret seque usurum Romanorum rege ut uili et abiecto mancipio loqueretur. Litteras ab amicis regibus qui et ei contra Valerianum fauerant plerasque missas accepit. Quarundam seriem Iulius refert.

ualere : ualore Ven. nimis : minus Ven. elatus . . . animo : elatus superbo et elato animo Ven. usurum : rursum Ven. ut : ne Ven. faverant : faerant E (a.c.) quarundam : quarum Ven.

For he was conquered by Shapur, the king of the Persians, when he was led by the guidance of one of his generals, to whom he had granted the authority for running the whole campaign, either by trickery or bad luck into a position where neither strength nor military discipline could do anything to prevent his being captured. He was captured therefore, and fell into the power of Shapur, who was puffed up with pride at the success of this victory, rather less honourably than was appropriate and with proud and haughty intention held him, and declared that he would use the king of the Romans as base and vile slave. He received quite a few letters from kings allied to him who, who were even on his side against Valerian. Julius records a whole series of these.

In one of these cases, one can already glean that the text of E is closer to Colonna than the Venice edition: a form of the verb valere is in both E and Colonna where the ed. Ven. has the noun valore. This holds true throughout the text. For example, E and Colonna give the names of the first two kings who wrote to Shapur on Valerian's behalf as Vesonius and Vellenius, where the ed. Ven. gives Belsolus and Valerius. (P and the editio princeps have vel solus and Velenus.)

Like any other manuscript, E has idiosyncrasies in its text, but we can use the other two sources for this tradition to help control for them. Agreements between E and either the ed. Ven. (against the editio princeps) or Colonna should represent the reading of the alternate tradition. A selected list:

The Lives of the Two Valerians

6.2 post senatus add. consulti E Colonna

6.3 aestimabis : extimabis E Colonna

6.3 manere in curia P Σ Ven. : in curia manere E Colonna

6.7 de militibus de senatu P Σ Ven. : de senatu de militibus E Colonna

1.2 posterisque E posteris P1 Med. et posteris P corr. posterisve Σ posteriusque Ven.

1.3 saepe E Σ Ven. mepe P1 nempe P corr. Med.

2.2 quid ad P Σ Med. quid habet et E Ven.

4.3 reges E Ven. regis P Σ Med.

The Lives of the Two Gallieni

1.1 post imperium add. et E Ven. om. P

2.1 occupauitque : atque E Ven.

2.5 post uenit add. deinde E Ven. om. P Σ Med.

3.9 uotiuumque E Σ Ven. uotiuum P Med.

4.6 gessit E Colonna gerit P

5.5 una E Colonna uno P

5.6 Illyricum E Ven. om. P Σ Med.

9.3 stupefacto E Colonna obstupefacto P

11.7 epithalamion : epistola miono P Med. epistola mioni Σ epithalamium E Ven.

12.6 post Persico add. et E Ven. om. P Σ Med.

13.2 tum E Σ Ven. cum P Med.

16.1 tyrannos esse passus est Romanum dehonestantes imperium E Ven. tyrannos uastari fecit P Σ Med. (suppl. per ante tyrannos Baehrens) cf. Alex. 2.2.

17.1 dixit ille sciebam patrem meum esse mortalem E Ven. nec defuit an ille se dixit sciebam patrem meum esse mortalem P Med. nec defuit cum ille sic dixit sciebam patrem meum esse mortalem Σ del. ut gloss. Hohl

21.5 annis E Ven. anno P Σ Med.

20.3 constillatosque E Ven. costilatosque P Med. costulatosque Σ.

All of these readings will deserve careful attention from the next editor of the HA. Let us focus on just one example: P's costilatosque in Gal. 20.3, an adjective used to describe what are some obviously rather splendid belts (baltei). The lexica consider costilatus as an adjective probably meaning ‘ribbed’, despite the fact that this is the only attestation of the word.Footnote 36 While the reading constillatosque in E and the ed. Ven. is not flawless, it points us to what must be the intended word, constellatosque or ‘jewelled’, which appears in several early editions, such as Boxhorn's Leiden edition (printed in 1631), and provides an easy palaeographic explanation for P's reading.

Nonetheless, our direct evidence for the tradition represented by E, the ed. Ven. and Colonna does not extend further back than the fourteenth century. To demonstrate that its text represents an even earlier tradition, we need to find occasional agreements with P in its earliest state. P's exemplar undoubtedly had its flaws, and it is inevitable that some of them would eventually be corrected conjecturally. A manuscript descending from the same source as P would show some of these errors. And this is indeed what we find. Proper names are particularly useful for this sort of analysis. At Val. 4.1, P and E share the reading Albini for Albani, which is found in Σ and was added into P by a corrector before L was copied. Likewise, E consistently calls the general Macrianus — Macrinus; so too, in a number of instances, does the main hand in P. However, in some of these cases P (for example, Gal. 1.2 and 3.2) was corrected very early on, before B was copied from P in the later ninth century. The same can be said for the reading Carrenis in E and P's first hand, which was soon corrected to Charrenis (Gal. 10.3). Outside of names, E shares with the first hand of P the reading gubernaret at Gal. 2.2, which was soon corrected in P to gubernabat; and eterni for externi at Gal. 9.2, which was corrected in P before L was copied.

This takes the origin of the tradition of E, the ed. Ven. and Colonna back to well before the fourteenth century, back to the time of P and its archetype. Strictly speaking, however, this may demonstrate the antiquity of E's text, but does not prove its independence of P. The standard of proof for independence is undoubtedly high. At Gal. 19.5, Salmasius first noted that a word must have dropped out, probably after anno: multi eum imperii sui anno periisse dixerunt. The sense demands nono, but there is no indication of anything missing in P, Σ or the early editions. But in E, we find a gap the space of several characters immediately following anno. If the scribe had recognised that another word was needed, why did he not supply one? Such lacunae, as have seen, were designed to represent how the source manuscript with illegible text appeared to the eye, with the goal of being able to fill in the gaps if another copy should turn up. Hence it looks as if E was copied from a manuscript which had a word rendered illegible by physical damage following anno.

Even more revealing, then, is E's text of the lacunose passages in P. Leaving intratextual lacunae of the sort we find in the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni is an important scribal practice, particularly in the early Middle Ages.Footnote 37 This indeed happened with Cicero's De oratore, which is extant with a lacunose text in two ninth-century northern manuscripts, Harley 2376 and Avranches 238. From these spring the whole medieval tradition. Unknown for centuries, however, there remained a manuscript of a completely separate tradition housed at the cathedral of Lodi. Discovered by Landriani in 1421, this manuscript was used to make the text of Cicero whole.Footnote 38

These lacunae could be transmitted through generations of copies, as indeed can be seen in the manuscripts descended from P. But in the case of P itself, we have good reason to believe that it was copied directly from the damaged archetype. On f. 154v (reproduced as passage C below), the writing is extremely compressed in the two lines before the lacunose passage, and at least the last half line before is certainly written in a different hand, given it uses an ri ligature seen nowhere else in the codex. Multiple hands active around lacunae are a feature that can be observed in the manuscripts of Ammianus as well.Footnote 39 As discussed above, one of the prime pieces of evidence against Σ's independence from P is its treatment of the lacunose passages. Hence examining these passages in E will shed light on its relationship to P and/or its archetype.

In two instances, E transmits less text than P. First, Gal. 5.6:

This would be difficult to explain if E were ultimately derived from P. Likewise, at Gal. 1.1 P begins the lacunose passage after exercitus with the truncated mur wholly absent in E. But in all other cases, E presents more text than P, with its supplements mostly corresponding to the shape of P's lacunae. In Table 1 (‘The Lacunose Passages in P and E’), I present the text as it appears in the manuscripts, with the actual line divisions and original readings, erroneous or not (I use / for line breaks, // for page breaks and ignore all later corrections in P).

Table 1. The Lacunose Passages in P and E

Unlike Σ's supplements, E's text corresponds with roughly the amount of text missing in P and provides new and substantive information. The ed. Ven. provides little assistance, mostly reproducing the Σ supplements from the editio princeps, albeit with occasional divergences which agree with E (the addition of ingens in Passage B, quoted above, and saevitum for victum in Passage E). Colonna, however, provides a strong parallel for E's version of Passage B, despite his paraphrasing:

Edili 173, f. 194v: sed Galienus Valeriani filius homo natura lascivior comperta patris captivitate gaudebat, iocabatur cum esset omnium ingens meror quod Romanorum princeps captivitate persicha teneretur.

Hence the treatment of the lacunose passages is not due to the fifteenth-century scribe of E, but rather goes back to the earlier tradition.

On the surface, then, it very much looks like a parallel case to Cicero's De oratore, where gaps in one tradition can be filled by recourse to another. Indeed, what is particularly interesting is that E's text appears not so much to supplement P, but to represent a different visual interpretation of a single hard-to-read archetype. Different eyes will be able to make out different elements of damaged texts. Despite all this, a determined sceptic could dismiss this filling as mere supplementation, early, perhaps, but supplementation all the same.Footnote 40 To prove with certainty the independence of E from P, what we need is to find a unique reading in E which must contain inherited rather than innovated truth — that is, a correct reading which is beyond conjecture.

Gal. 13.8 contains a rather compressed and confused account of a barbarian invasion into Greece and its subsequent repulsion by an Athenian force. In P it reads as follows:

atque inde Cyzicum et Asiam, deinceps Achaiam omnem vastarunt et ab Atheniensibus duce Dexippo, scriptore horum temporum, victi sunt.Footnote 41

There are no apparent problems with this passages — the manuscript tradition of P and Σ and the early printed editions display no variants, beyond some difficulty with the orthography of Cyzicum and the form of the verb vastarunt — and the sense is immediately clear and obvious. And yet this passage has hung under a cloud of suspicion for more than a hundred years. The event described is the Herulian invasion of Greece in 268. While our surviving historical accounts do not shed much light on this event, the archaeological record demonstrates the traumatic impact of the incursion.Footnote 42

The general and historian mentioned, Dexippus, happens to be a reasonably well known person.Footnote 43 His writings may mostly be lost — although the spectacular discovery of the Vienna palimpsest has provided substantial sections — but his career left a mark on the physical fabric of Athens.Footnote 44 A number of surviving inscriptions detail his career in great detail, including IG II2 2931, 3198, 3667, 3671 and especially 3669. We know the succession of offices Dexippus held: basileus, eponymous archon, kratistos, a priesthood at Eleusis, agonothete and panegyriarch of the Panathenaic games. The final inscription (which includes the most detailed sequence of offices) was erected by Dexippus’ sons and postdates the Herulian invasion, yet it makes no mention of Dexippus’ starring role. As Fergus Millar put it, ‘we could hardly guess from this inscription that Dexippus had ever seen military action’.Footnote 45 Instead, its real focus is on Dexippus’ achievement as a writer of history, as a chronicler of the barbarian invasion, rather than as the general who led the glorious resistance. The only evidence we have for Dexippus’ military career is this passage in the HA.

It is not entirely implausible for the HA to transmit valuable information about Dexippus, since it relied more or less extensively on Dexippus’ historical work. T. D. Barnes argued some forty years ago that the major source for the Two Gallieni is Dexippus, and the new Vienna fragments have offered additional corroboration for this view.Footnote 46 Nonetheless, it remains rather remarkable that no one saw fit to commemorate his military achievements in Athens.Footnote 47

In 1897, J. Bergman recognised the fundamental implausibility of the HA's claim and proposed a simple solution: instead of duce Dexippo, what if the original read indice Dexippo or docente Dexippo?Footnote 48 Nine decades later, powerful arguments against the HA's account were assembled by de Ste. Croix.Footnote 49 In general, modern scholars have remained sceptical (and perhaps, at times, overly sceptical) of ‘facts’ found in the HA alone.Footnote 50 In this anomalous case, however, they have generally accepted the testimony of the HA without corroboration. For many of them, the decisive factor has been simply the lack of any manuscript support for Bergman's emendation.Footnote 51

The Erlangen manuscript offers a dramatic confirmation of Bergman's instinct (f. 48r):

atque inde Cyzicum et Asiam, deinceps Achaiam omnem vastarunt et ab Atheniensium duce ut scribit Thesipus horum temporum scriptor.Footnote 52

There is simply no way that a fourteenth- or fifteenth-century scholar would have had any difficulty with the line as transmitted in P. There is nothing fundamentally implausible about the idea of a single figure being both a general and an historian: witness Thucydides and Caesar. Instead, the doubt arises because of the particularities of Dexippus’ life and career, which only came to be known with the publication of the inscriptions from Athens, centuries after E was written. No evidence available in the Renaissance would motivate tampering, so E's text ought roughly to represent the archetypal reading.

Thus, even under the most stringent conditions, I have shown the independence of the tradition represented by Colonna, E and the Venice edition. This allows the text to be restored in four out of the six lacunose passages, adding in total some twenty lines. For the Life of the Two Valerians, we also have the two new added passages, Valerianus imperator… and Victus est enim… . Of course, just because they are derived from a source independent of P does not make them authentic, and I do have some doubts about the authenticity of the first one in its current form.Footnote 53 Throughout the two lives where E is extant, there are some hundred new readings which will require close examination by the HA's next editor, and across the rest of the text there are hundreds more readings from Colonna and the ed. Ven. which need to be recorded and considered, in addition to the three new passages from Maximus and Balbinus and Alexander.

IV

So far, we have found a new tradition for the text of the HA. The immediate question that arises, then, is what impact this new tradition has on our understanding of P, its correctors and its relationship to Σ? To give one example, Matoci supplied a line in the gutter of f. 71v of P (Caracalla 8.2): eumque cum Severo professum sub Scaevola et Severo in advocatione fisci successisse. There has been debate about the authenticity of this supplement, since Mommsen rejected it as a spurious interpolation.Footnote 54 Even so, it could hardly be Matoci's invention, given the detailed knowledge of the Roman political system this line implies. It is also found in Colonna.

hic fuit ille Papinianus famosissimus iuris consultus qui fuerat Severo amicissimus atque cum eo sub Scevola iuris consulto professus fuerat, cui postea in advocationem fisci successit (ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 220).Footnote 55

As a result, this line must derive from the non-P tradition, and Matoci must have had access to it. So too there are multiple phrases and sentences transmitted in Σ alone, such as:

At Aelius 5.9: atque ad verbum memor iterasse fertur.

After Alex. Sev. 56.10 victoriam: de Germanis speramus per te victoriam

After Tacitus 16.8 studio: satisfeci claudam istud volumen

After Aur. 19.4 beneficiis: inserviendum deorum immortalium praeceptis

After Aur. 19.5 opem dei: deorum quae numquam cuiquam turpis est

After Aur. 19.6 perquirite: patrimis matrimisque pueris carmen indicite. Nos sumptumsacris, nos apparatum sacrificiis. Nos aras tumultuarias indicemus.

After Aur. 29.3 nos est: sed hoc falsum fuit

The authenticity of these supplements has been debated. Thomson has strongly defended the authenticity of the addition in 19.6 on basically irrefutable historical grounds.Footnote 56 I would add to that demonstration, that two of these (Alex. Sev. 56.10 and Tac. 16.8) look like saut du même au même omissions, which makes it very unlikely that they were faked. One of these passages, at least (Aur. 19.5), must have been in Colonna's text:

Edili 173 151r: rogabat inperator <deorum> opem que numquam cuique turpis estFootnote 57

In addition, Modonutti has already shown that in a large number of individual cases, Colonna has what we otherwise know as Σ readings.Footnote 58

And yet, when we turn to the treatment of the lacunose passages in Val. and Gal. discussed above, Σ, as we have seen, presents stitched up versions of P, with nary a trace of the text in E and Colonna. There are other indications as well: besides additional passages, Σ contains a large number of omissions. Some of these omissions seem to correspond ever so closely to physical features in P. The eye of the scribe of Σ's archetype had a habit of wandering down to the next line before he had finished the previous one. So at Claudius 14.5 Σ (with the partial exception of one manuscript) omits balteum … uncialem, where P has (f. 179r; I have put in bold the text in Σ):

auream cumacum cypream unam . Balteum argentum auratum

unum . anulum bigem me unum . uncialem; brachialem unam

At Tacitus 14.4, Σ omits haec….ostendit, where P appears as follows (f. 199r):

usque quaenam effusionem ineo fratres frugi reprehendite . haec ipsa imperan

di cupiditas aliis eummoribus ostendit . fuisse quam fratrem duo igitur principes

At Tyr. Trig. 18.3, Σ omits ut…imperaret, where P has (f. 168v):

multa et sumpsisse illum purpuram . ut moreromano imperaret

exercitum duxisse

Finally, at Quadriga 3.6, Σ omits per…pretium; compare P (f. 208v):

taceoita domumelicum iovioptimo maximo consecratum perdeterrimum princi

pem et ministerium libidinis factum vi detur pretium . Fuit tamen firmus

In other cases, Σ omits phrases which begin a line in P, such as at Probus 15.1, where it omits the ago dis immortalibus at line beginning in P (205r); Probus 23.3, where it skips nusquam lituus audiendus, a phrase at line beginning in P (f. 207v); and Carus 17.7, where it jumps over longum….dicere where in P (f. 215v) the line begins with -gum. In another case, it looks like Σ has omitted a whole line in P, and excised the surrounding nonsense. At Macrin. 4.1 Σ omits varium…dixisset; compare P (f. 92r):

crino quidem insenatu multi quando nuntiatumest variumhelio

gabalum imperatorem cum iam caesarem alexandrum senatus di

xisset ea dicta sunt appareat nobilem sordidum spurcum fuisse

Once the line was skipped, the nonsense word variumhelioxisset would be all that remained, and would be a prime candidate for deletion.

It is not just deletions. On f. 151r at Maximus and Balbinus 16.6, P reads duorum⋅/gordianorum⋅/inafrica, with the two ⋅/ signs indicating transpositions. The scribe of B was probably correct to interpret these as meaning that in Africa should be placed before Gordianorum; that is, that Gordianorum should have its place swapped with in Africa to make duorum in Africa Gordianorum (f. 150r). This is a subtle change, so it is not especially suprising that L's scribe missed the transposition and just wrote P's original duorum Gordianorum in Africa (f. 75r), which ensured that this was the reading in all the editions up to Peter's. The scribe of Σ's archetype instead understood the two marks to be attached to duorum and in Africa, and so placed in Africa before duorum Gordianorum. This is obviously incorrect, but it is a mistake that only could have arisen from reading P itself: it cannot be a coincidence that Σ has a transposition just where P marks one, and that its reading could only arise from a misunderstanding of P's correction.

One final indication of Σ's derivation from P can be found at the beginning of the Two Valerians. Here Σ follows P's arrangment with the letters to Shapur first, but with an additional passage at the beginning.Footnote 59 It is a combination of Eutropius 9.7 and Orosius 7.22.4, with what appears to be a deal of tenuous extrapolation from the life of Valerian. Even so, a few words show the influence of the extra passages in E and the ed. Ven.: nobilis, per multas dignitates ac officia, incauto suorum ducto.Footnote 60 This suggests that the scribe of Σ's archetype must have been copying from a manuscript with P's arrangement of the life, but did not want to let the additional material in his other source to go to waste, and so combined it with his other historical sources to make a bridge passage.Footnote 61

The nature of Σ can thus be best explained as being descended from P but contaminated from the source of Colonna's text of the HA. P, after all, is not the only known early manuscript of the text. There is also the B, but that is a copy of P, and so hardly useful for finding an independent source. In addition, we know from the Murbach library catalogue that there was a manuscript of the text present there before the middle of the ninth century, and we have a single folio from this manuscript preserved in Nuremberg (fr. lat. 7).Footnote 62 One folio is not enough to say much about the Murbach text, but we have an underexploited resource for recovering many of its readings: the Basel edition of 1518, printed by the famous house of Froben.

Froben had heard of the old manuscript of the Historia Augusta, and as he was preparing the edition with Erasmus, the ostensible editor, he wrote to the Abbot of Murbach, Georg von Masmünster (George de Masevaux), to try and obtain the codex. No answer came, and in the winter of 1518, they began printing the text. After, however, all the lives up to Diadumenus (in the order of the first edition) had been printed, eight quires in total, Froben at last got his hands on the manuscript.Footnote 63 At the same time, Froben finally managed to obtain a copy of Egnatius’ 1516 edition from Venice at the Frankfurt book fair held the week before Easter, the first week of April 1518. Reprinting would have been disastrous, financially speaking. So instead Froben decided to print a collation of the Egnatius and the Murbacensis against the text which had already been printed. These collations shed further light on Σ. At Ael. 2.5, Froben reports the Murbacensis read durativum for P's duraturum — certainly an error, since durativum has very little claim to being a Latin word in use before the Middle Ages.Footnote 64 Σ has the same reading. The same can be said for Ael. 6.3 incubuimus where P reads incuibimus (later banalised by the corrector to incumbimus), Ael. 7.5 adoptionem where P reads adoptationem, and other passages as well:

Marc. Aur. 12.4 egerat M Σ] gerit gerat P

Comm. 8.6 8.6 qui M Σ] cui P

Comm. 2.9 lenonum M Σ] lelomihi P1

Comm. 18.16 imperante M Σ] imperatore Bas. imperantem P

We can also confirm this from the Nuremberg fragment, which reads piscinam correctly with Σ against P's pircinam at Comm. 11.3. Of course, these readings and the bulk of the other examples not adduced here are correct readings against errors in P, and so provide no sure evidence of influence. Durativum, however, as an extremely idiosyncratic error, is sufficient to secure the connection between M and Σ.

There are connections between M and Colonna as well. Take the following three reasons:

Marc. Ant. 22.4 tot et talium . . . tot et tales M] tot talium . . . tot tales Bas. P

Colonna, ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 165: tot et talium … tot et tales

Comm. 2.9 lenonum minister ut probris M] lebronum ministeriis probris Bas. lelomihi minister ut probris P1 lenonum minister ut probris P corr. Σ lebronum minister inprobis L

Colonna, ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 190: In palatio autem inperiali mulierculas forme pulcrioris instituit ad prostibulorum formam ac pudicitie ludibrium, onnibus undique conuocatis lenonibus, tenebat

Comm. 17.1 Q. Aemilius M] Quintus Aelius Bas. Quintius Aemilius P

Colonna, ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 195: Quintus Aemilius

The third of these is obviously the weakest. The first is fairly minute, but strongly suggestive of some relationship between M and Colonna. The middle one clinches the case. Colonna has, of course, completely rephrased the passage. There can be no doubt, however, that his text of the HA read lenonum. P read the absolute nonsense lelomihi, not improved by L's lebronum, which passed into the early printed editions, and no one managed to record the correct meaning until Σ came along, and P was corrected from a Σ manuscript.

The foregoing might seem a slight evidentiary basis, but this is because Froben's collations, as a guide to M's readings, are frustrating to say the least. Comparing the Basel edition with the extant Nuremberg fragment, we can conclude that Froben caught less than half of the divergences between his codex and his edition. He was also not collating M against P, but rather against his own edition, which was based on the Venice 1489, based in turn on the editio princeps which was based on a combination of L and an unknown Σ manuscript. They also only run up through the first third, or so, of the text. For the rest of the text (including, unfortunately, the two lives transmitted in E), all we have is Froben's claim that the Murbach manuscript was used for the rest of the text. In point of fact, almost all of the divergences between the Basel edition and its source in the Venice 1489 edition after Diadumenus are taken from Egnatius’ 1516 edition. Even so, there are a couple of suggestive readings:

Gal. 7.7: principe E Bas.] principem P Σ Med. Ven. Egn.

Gal. 11.4: pace P Σ Med. Ven. Egn.] aetate E Bas.

While the first of these is hardly conclusive, the second is almost definitive, since the 1518 edition prints in the margin als. pace, or ‘in the other, pace’, which is the reading of P, Σ and all the other editions, including that of Egnatius. A glance at the other marginal variants in the edition for the Lives of the Two Valeriani and the Two Gallieni show how these annotations functioned:

Val. 1.5 remotioribus in marg. Alius. Interioribus

remotioribus Egn. interioribus PEΣ Med. Ven.

Gal. 4.8 Corinthum in marg. Alius. Astacum

Astacum Egn. Contum PE conthum Σ (corinthum R) corinthum Med. Ven.

Gal. 13.8 Macedoniam, Moesiam in marg. Alius. Achenoniam, Boetiam

Macedonaniam moesiam Egn. achenoniam boetiam PE Med. Ven. anthenoniam moesiam Σ

In the first and last, Erasmus decided to print Egnatius’ emendations in place of the reading of his base text from the Venice edition, while in the second he records Egnatius’ (palmary) conjecture in the margin, printing his received text. None of these cases give us any certain information on the readings of the Murbacensis, since they can all be accounted for by means of the two other sources we know were used: the ed. Ven. and Egnatius. But we cannot otherwise account for aetate at Gal. 11.4. The only place the editor could have taken aetate from is the Murbach manuscript. Now aetate is certainly an error, referring as it does to Antoninus Pius, who was, after all, over fifty when he became emperor. But the phrase adulta fecerat pace could easily have led to aetate, even though it does not actually make sense in context. Hence, we have here a shared error between M and E.

Perhaps there is a reason for this. As discussed above, we know a good deal about Campano's journey to the North and back. On the return journey, the party headed straight down the Rhine valley, from Heidelberg to Hagenau to Strasbourg to Breisach, and on to Basel.Footnote 65 This itinerary — undertaken at considerable haste, one might add, since they made the more than 1,250 km to Rome in fewer than forty days — would have taken them within probably less than 20 km of the Abbey of Murbach. Obviously this is simply conjecture, but Campano would have had the means to have seen, or to have sent a factotum to examine, the Murbach manuscript.Footnote 66

So the outlines of a coherent picture of the non-P source for the text of the HA begins to emerge. Filling it out is beyond the scope of the present study. Suffice it to say here that we have cleared up the mystery of Σ. It is not itself a source for the text independent of P, but was contaminated from such a source. Hence, all Σ readings do need to be considered, and when they agree with Colonna, or the Venice 1489 (where it differs from the editio princeps), or Froben's Murbach collations or the Basel 1518 (where it differs from the previous editions), they should be regarded as a reflection of the non-P source. As consequential as these conclusions may be, this new tradition of the text of the HA has another feature which can provide new insight into the nature of the work itself.

V

Now that we have shown the independence of the tradition of Colonna, E, the ed. Ven., the Murbach manuscript etc., we can use their evidence to understand something about the transmission of the text before P, which in turn will overturn a widely accepted theory about the nature of the work. Besides new passages, this tradition offers a significant transposition in the Two Valerians. I do not intend here to rehash the arguments of Patzig and Peter on which arrangement of material is more consistent with the other lives of the HA. Instead, let us look at this transposition as a codicological feature.

We have a very precise notion of the physical characteristics of P's archetype, due to the disorder of gatherings afflicting the Alexander, the Two Maximini and the Maximus and Balbinus, as well as the transposed passage in the Carus representing an archetypal folio. Folios first. The latter passage, Carus 13.1 Augustum to 15.5 nullam, which is transposed in P after 2.2 felicitas, consists of 1,965 characters without spaces. This is the most direct evidence we have for the length of a folio in P's archetype. There is, however, a less direct piece of evidence. In the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni, the lives which directly follow the great lacuna, there are found the six intratextual lacunae caused by illegible text in the archetype. Successive lacunae like this usually are caused by physical damage, afflicting the tops or bottoms of pages.Footnote 67 Indeed, were there any doubt that these lacunae tell us something about the physical characteristics of the archetype, one only needs to calculate the amount of text between the lacunose passages:

Between the first two lacunae, Val. 8.4–Gal. 8.1: 256 characters

Between the second and third, Gall. 1.1–1.2: 315 characters

Between the third and fourth, Gall. 2.4–5: 257 characters

Between fifth and sixth, Gall. 4.3–4.4: 351 characters

This regularity indicates that something more than indiscriminate calamity dictated where the damage occurred. Everyone acknowledges that the displaced passage in the Carus (of 1,965 characters) represents an archetypal folio. The amount of text between the two sequences, that is between the fourth and fifth, from Gall. 2.1 quae contra to 4.2 imperator, is 2,039 characters. It makes good codicological sense for the amount of space between these two sequences to make a folio, whether or not a single folio actually intervenes, since we would expect physical damage to occur at roughly the same places on the page.

Likewise, Colonna, E and the ed. Ven. do not begin with the letters of the eastern kings to Shapur (Val. 1.1 Sapori to 4.4 Persici) pleading for Valerian's release, but rather with Valerian's appointment to the censorship by Decius (Val. 5.1 cuius – 7.1 superatus est), followed by a bridge passage not in P, and then proceeding to the letters. In other words, the difference between these two is where Val. 1.1 Sapori to 4.4 Persici is placed. That passage consists of 2,059 characters, exactly in the range of a folio in P's archetype. Hence, neither the independent tradition nor the scribe of P should be accused of wilfully rationalising or recasting the text, as alleged by Patzig and Peter. The question instead is where a loose folio should be inserted into the text.

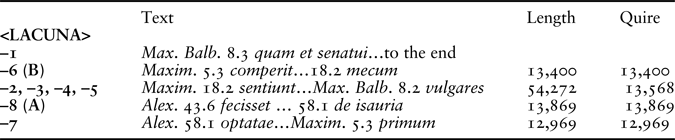

Let us move from folios to quires. We know quite a bit about the gatherings in P's archetype due to the fact that two gatherings were copied in the wrong place. This happens right before the great lacuna. We can count back eight gatherings, although we do not know the length of the final gathering with certainty, since (as I will show) we do not know if text was lost. Two of these gatherings were copied out of order in P, which Ballou dubbed A, Alex. 43.6 fecisset … 58.1 de isauria, and B, Maxim. 5.3 comperit…18.2 mecum. We know these are gatherings, since they are almost identical in length (13,869 and 13,400 characters respectively), and consistent with what we know was the length of individual folios (1,700–2,000 characters). The order of text in P up to the lacuna is as follows: Alex. 58.1 optatae…Maxim. 5.3 primum, Alex. 43.6 fecisset … 58.1 de isauria (B), Maxim. 18.2 sentiunt…Max. Balb. 8.2 vulgares, Maxim. 5.3 comperit…18.2 mecum (A), and then finally Max. Balb. 8.3 quam et senatui…to the end of the life. These various chunks of text are all consistent with gatherings. Alex. 58.1 to Maxim. 5.3 is 12,969 characters, and the long passage Maxim. 18.2 to Max. Balb. 8.2 is 54,272 characters, which divides evenly into four gatherings averaging 13,568 characters. Hence, we know almost exactly the codicology of the eight gatherings preceding the lacuna in P's exemplar. The following table gives one model of how the gatherings before the great lacuna are arranged in P with the sequence of numbers giving the correct order, counting backwards from the from the great lacuna, the length of each block of text in characters and what that entails for the length of quires.

This disarrangement affects only P. Σ has the correct order, whether through inheritance or innovation. Colonna also seems to have had the correct order, since he narrates Alexander Severus’ campaigns as follows (ff. 142v–143r, ed. Modonutti Reference Modonutti2013: 249):

(Alex. 58.1) Preterea in Mauritania Tigina per Furium Celsum res prospere geste sunt et in Illyrico per Macrinum et in Armenia per Iulium Palmatium legatum. (Alex. 59.1) Igitur post belli gloriam, cum Rome apud populum et apud senatum civiliter vivendo nimium Alexander amaretur, ad bellum Germanicum proficisci voluit:Footnote 68

Caution is in order, because Colonna constantly rearranges his source texts, but this passage looks like a straightforward summary of a passage from the Historia Augusta. And yet if Colonna's manuscript of the HA had P's arrangement of gatherings, the second half of the passage (on 115v in P), from Igitur post would have occurred some ten folios before the first half (concluding on f. 125r).

Matoci, the industrious corrector of P, laboured mightily to restore the correct order to P. At the beginning of passage B, on f. 120r, he writes, ‘Vitam maximini et filii eius valde confusam et cum grandi labore reduc[trimmed] ad semitam veritatis sic colige.’ What he proposes is that B, which he takes (correctly) as beginning with comperit Alexandrum and (incorrectly) as ending with Max. Balb. 8.3 nomine nuncuparunt at the top of f. 148v (instead of with Alex. 18.2 mecum, which is two lines from the bottom of f. 148r), should be transposed before Alex. 58.1 vario tempore, which is very close to where it belongs, two words later, before optatae. For passage A, on f. 106r, he provides a signe-de-renvoi and notes, ‘Require sequentia ubi est signum supra hic notatum in vita Maximini. Et incipit sic Occiso heliogabalo etc.’Footnote 69 So he mistakes the start of A as beginning with Occiso Heligabalo ubi primum, the four words preceding A, which begins with fecisset. More importantly, however, he restores A to a curious position earlier in the text, right before Alex. 15.6 negotia et. This is what we find in L, the manuscript copied from P after Matoci's correction and before the later refinements (f. 52rb):

…(Alex. 15.5) capitali pena adfecit. (Maximin. 5.3) Occiso Heliogabalo ubi primum (Alex. 43.7) fecisset et templare reliquia deserenda. (Alex. 44.1) In iocis…Footnote 70

This arrangement was maintained in the Milan editio princeps, derived primarily from L, and in the ed. Ven., which simply copied it from the editio princeps.

The same is true with passage B, Maximin. 5.3 comperit Alexandrum … 18.2 omnes qui mecum, which in P was copied into the middle of the Life of Maximus and Balbinus, right between 8.2 homines vulgares and quam et senatui. Matoci's attempt to fix the problem accidentally scooped up a little bit of Max. Balb. 8.2–3:

quam et senatui acceptissimam et sibi aduersissimam esse credebant. quare factum est, ut diximus, ut Gordianum adulescentulum principem peterent, qui statim factus est. nec prius permissi sunt ad Palatium stipatis armatis ire quam nepotem Gordiani Caesaris nomine nuncuparunt.

Matoci's solution was picked up by L, which on f. 73r goes directly from 8.2 homines vulgares to 8.4 his gestis, with the missing bit (concluding with the end of passage A, vario tempore etiam cum de Isauria) found on f. 63vb in the middle of the Two Maximini 18.2 between mecum (with Matoci's sunt added) and et Gordianos. This arrangement is followed by the editio princeps with the wider passage from Maximus and Balbinus on f. 96r, but the orphaned middle section (Max. Balb. 8.2–3) considerably earlier on f. 84v.

In the ed. Ven, this orphaned bit of Maximus and Balbinus remained lost, trapped in the The Lives of the Two Maximini, producing the following text, a hopeless amalgam of materials from three different lives (f. 115r):

(Maximin. 18.2) Sanctissimi autem p. c. illi qui & Romulum & Caesarem occiderunt: me hostem iudicaverunt: cum pro his pugnarem: & ipsis vincerem: nec solum me: sed etiam vos: & omnes qui mecum sunt: (Max. Balb. 8.2) quos & senatui acceptissimos: & sibi adversissimos esse credebant. (Max. Balb. 8.3) Quare factum est: ut diximus: ut Gordianum adulescentulum principem peterent: qui statim factus est. Nec prius permissi sunt ad Palatium stipatis armatis ire: quam nepotem Gordiani Caesaris nomine nuncuparent. (Alex. Sev. 58.1) Vario tempore cum etiam de Isauria (Maximin. 18.2) sentiunt & Gordianos, patrem ac filium Augustos vocarent.

Something remarkable, however, has happened to the text of the original passage (Max. Balb. 8.2–3, ed. Ven. f. 120v), which has no parallel in the editio princeps or any of the known manuscripts.

(Max. Balb. 3.2) Egressi igitur e senatu: primum capitolium ascenderunt: ac rem divinam fecerunt. (Max. Balb. 8.2) Sed dum in capitolio rem divinam faciunt. populus ro. imperio Maximi contradixit: timebant enim severitatem eius homines vulgares. (Max. Balb. 8.3) Quare factum est: ut gordianum adolescentulum principem peterent: qui statim factus est: nec prius permissi sunt ad palatium stipatis armis ire: quam nepotem gordiani Caesaris nomine nuncuparent. (Max. Balb. 3.3) Deinde ad rostra populum convocarunt.Footnote 71

Two things stand out here. First, the orphan bit which is printed five pages earlier in Venice 1489 is printed again here, albeit lacking quam et senatui acceptissimam et sibi adversissimam esse credebant. There is no evidence whatsoever that the Venice editor was even aware of the problem of the transposition — much less had the capacity to fix it. What we see here is typically agglutinative: we know the editor had a manuscript source he used in addition to the editio princeps, that manuscript source must have had Max. Balb. 8.3 where it belongs after 8.2, and he cheerfully and obliviously printed the same bit twice in two different places using both of his sources. But equally remarkable is the fact that the whole affected passage, 8.2–3, is itself transposed to between Max. Balb. 3.2 and 3.3.Footnote 72 It can hardly be coincidence that where one of the destructively rogue gatherings of P's archetype happened to land finds itself on unstable footing.

It helps that the order found in the Venice edition could be original. The HA is here following Herodian quite closely, and the reordered narrative fits Herodian's much better than P's order (7.10.5–9). Indeed, in this case we may find a rare tell-tale sign of disturbance in the original text of P, which actually reads at 8.3 ‘quare factum est ut diximus’, seemingly to smooth over the lack of chronology. Finally, to clinch the matter, the subtraction of 8.2–3 still gives good sense to the surrounding passage:

(Max. Balb. 8.1) Decretis ergo omnibus imperatoriis honoribus atque insignibus, percepta tribunicia potestate, iure proconsulari, pontificatu (-tum P) maximo, patris etiam patriae nomine inierunt imperium. (Max. Balb. 8.4) His gestis celebratisque sacris, datis ludis scaenicis ludisque circensibus gladiatorio etiam munere, Maximus susceptis votis in Capitolio ad bellum contra Maximinum missus est cum exercitu ingenti, praetorianis Romae manentibus.Footnote 73

The purpose here, however, is not to advocate for one reading or the other, but rather to demonstrate that, first, the other manuscript source did not have the same disorder as that found in P, L and the editio princeps, and second, that this tradition has its own signs of disorder not found in the other tradition. It also frustrates attempts to identify the precise length of the final gathering before the great lacuna, since we do not know where the passage it falls into ought to be placed within Maximus and Balbinus.

Indeed, confusion continues up to the last line of that gathering, where the Venice edition closes with text not in P:

(Max. Balb. 18.1) Haec epistola probat Pupienum eundem esse, qui a plerisque Maximus dicitur nomine paterno. Si quidem per haec tempora apud Graecos non facile Puppienus, apud Latinos non facile Maximus inveniatur, et ea, quae gesta sunt contra Maximinum, modo a Puppieno modo a Maximo acta dicantur. sed Fortunatiano credamus, qui dicit Pupienum dictum nomine suo, cognomine uero paterno Maximum, ut omnium stupore legentium aboliti uideantur.Footnote 74

It is highly unlikely that the final sentence, not found in P, with its citation of an authority introduced earlier (Max. Balb. 4.5), and the flagrant nonsense of its last four words, is an invention of the Venice editor. Only excessive regard for P could produce such an opinion. As we have seen, the Venice edition relies on a manuscript source which could go back to P's archetype, and so there is no reason not see this as an omission in P itself. This also has a direct bearing on the question of gatherings. A single sentence makes a scant difference in the length of a gathering, but if there was text at the end of Maximus and Balbinus that P does not transmit (perhaps due to illegibility arising from physical damage), there may well have been more of it than the single corrupt sentence found in the ed. Ven. Hence we should be doubly cautious in extrapolating the length of the last gathering or gatherings before the great lacuna.

As we have seen, the eight or so gatherings preceding the great lacuna exhibit a considerable amount of textual and codicological turmoil, none more so than the final gathering.Footnote 75 Here a gathering from much earlier in the codex which is the source of the whole tradition was inserted, and the text itself is in chaos, to such a degree that we can gain no clear picture of what it was like when it was whole. The same holds true of the gathering after the lacuna. The folia were disarranged — there is no clarity on where the text even begins. Further, all the intratextual lacunae in the Two Valerians and Two Gallieni seem to occur in what would have been the first gathering: from the beginning of the Two Valerians through the last of lacunose passages (Gall. 4.4 Gallienus) there are some 10,400 characters, which leaves more than enough space to make up for the missing text.

Obviously the manuscript had suffered much. It was disbound and had loose folios as well. What sort of disaster afflicted the Maximus and Balbinus cannot be guessed, nor can the malady afflicting both the Two Valerians and the Two Gallieni, although, given the codicological regularity of the damage, fire and water are strong candidates. It is almost as if it was precisely at this point the manuscript was subjected to some extreme trauma, which spilled out over into the neighbouring gatherings, centred around the lives of Maximus and Balbinus and the Two Valerians. This is significant, because it is between these two lives that we are missing a decade's worth of lives, stretching from 244 to 253 (or 260), covering the four emperors Philip the Arab, Decius, Trebonianus Gallus and Aemilianus, the ‘great lacuna’ mentioned above.

Conventional opinion has for many years held that the great lacuna is a deceit cooked up by the crazed author of the HA. ‘It is a triumph of modern scholarship on the Historia Augusta’, writes Rohrbacher, ‘to have demonstrated that this lacuna is not just the unexceptional result of textual dislocations common in ancient manuscripts, but is actually the purposeful construction of our creative author.’Footnote 76

There are two different theories that posit that the lacuna is a deliberate feature. The first was proposed by Casaubon, who proposed that the compositor of the corpus was a Christian, and omitted the lives ‘driven by fervour of Christian piety to hatred of the Decii’ (‘pietatis Christianae fervore impulsum in Deciorum odium’).Footnote 77 This ‘suppression theory’ continues to find adherents.Footnote 78 However most scholars do not consider the missing lives to have been suppressed in the course of their transmission, but rather suppose that they were never written at all, a theory which in its most popular form goes back to A. R. Birley. Birley argued that:

in order to avoid dealing with the reigns of Decius and Valerian, in which major persecutions of the Church took place, and of Philip, a supposedly philochristian emperor, the author of the HA served up his work with a deliberate lacuna.Footnote 79

All sorts of other reasons have been introduced in the years since, such as the end of Herodian's history, the lack of source material in general, the author's reverence for the emperor Julian, or imitation of fragmentary texts. Birley and his successors have catalogued how frequently the author of the HA discusses physical books before the lacuna, how most of the facts known about these emperors are already included in other lives, indeed how coded messages elsewhere in the text contain the author's confession of the hoax.Footnote 80

Too much ingenuity and toil have been spent for nothing. The state of the text shows without any question that the archetype suffered a considerable trauma, centred almost exactly on the lacuna. The very last line before the lacuna is not transmitted by P, but solely by the other tradition. After the lacuna, we have another line not in P, and an errant folio from a gathering which toward the end suffered heavy physical damage resulting in the intratextual lacunae. How does it happen that the parts of the work affected most severely by codicological problems and physical damage just happen to be the text on both sides of a fake lacuna? Evidence like this cannot be manufactured. Arguments that the lacuna is authorial do not need to be addressed individually: they represent special pleading.

This discovery also casts strong doubt on the suppression theory. It is conceivable that the damage could have been caused by the dismemberment of the archetypal codex to remove the offending lives. It would not explain, however, why the confusion reaches so far back into the work, nor can it explain what looks to be physical damage at the end of the first gathering after the lacuna. More importantly, this theory cannot account for why half of the (very positive) Life of Valerian remains.