I INTRODUCTION

There are limited sources to determine who learned to write in Italy in the centuries after writing was brought to the peninsula, and there is even less information on methods of education in this period. Most of the evidence on ancient elementary education practices comes from the Greek world, and particularly from Hellenistic and Roman Egypt.Footnote 1 The handful of Roman republican literary sources which refer to education are often understood to imply (a) that literacy was usually limited to elite boys; (b) that the early stages of education, such as learning the alphabet, were mainly undertaken in the home; and (c) that education only started to become more structured in Italy when Greek models were imported to Rome during the late Republic.Footnote 2 However, this picture is incomplete. Looking beyond Greek and Latin, the other languages of Italy provide valuable information about how writing was taught, who learned to write and the possibility of schooling outside the home in Italy.Footnote 3

This article examines the Venetic dedications to the goddess Reitia at the Este-Baratella sanctuary as evidence for elementary education in Italy in the fourth to second centuries b.c. These texts appear on dedicatory bronze writing implements — specifically, writing-tablets and styluses — inscribed with imitations of learners' exercises (or teachers' models) such as abecedaria, lists of consonants and groups of consonant clusters. Some of these texts seem to state that the abecedaria, rather than the bronze objects, are the main dedications, and as a result Reitia is sometimes described as the ‘goddess of writing’.Footnote 4 These unique inscribed votives are not often cited in wider discussions about ancient education, but they can provide key evidence for teaching and learning methods in Italy, the social groups who had access to basic literacy and learners' attitudes to acquiring literacy.

After an overview of the content, layout and main features of the dedications, I will explore how these objects function as votives, with reference to the wider Italian culture of votive dedications in this period. While no direct comparanda exist for the dedication of bronze writing implements with such elaborate writing exercises, this article will also explore other sites and texts in the ancient Mediterranean where alphabets appear in funerary and votive contexts, showing that there was a wide spectrum of dedicatory habits involving abecedaria and writing tools across the ancient Mediterranean. I will also suggest that the dedication of bronze writing-tablets and styluses was a specifically elite activity, and that other lower-cost parallel forms of dedication may have been performed at Este and elsewhere, such as the dedication of wooden writing-tablets.

Secondly, I will compare these Venetic texts to surviving Greek writing exercises of a similar period. This comparison will show that the Venetic texts fit into a wider Mediterranean context, and are a plausible representation of ancient education practices. As such, they are among the earliest pieces of extant evidence for the methods of teaching basic alphabetic literacy in Italy. A further thread which runs throughout this discussion is the strong link between Reitia, literacy and women. The large number of women named as dedicators in these texts suggests that women, or at least elite women, were actively engaged in the epigraphic habit of the city, and points towards an association between women and elementary literacy at this sanctuary site. This has important implications for our understanding of literacy in the Italian peninsula during this period, and suggests that elite women's literacy in pre-Roman and early Roman Italy may previously have been underestimated.

II DEDICATIONS TO REITIA

The Este-Baratella Sanctuary

Este and its neighbour Padua were the two largest urban centres in the Veneto region until the foundation of nearby Roman colonies in the second century b.c. (Fig. 1). The earliest extant inscriptionsFootnote 5 from Este are dedicatory and funerary inscriptions dated to the second half of the sixth century;Footnote 6 however, most of the inscriptions at Este in the Venetic alphabet date to 350–150 b.c. There is also a considerable corpus of Venetic inscriptions written in the Latin alphabet dating to 150–50 b.c. In total, around 250 extant Venetic inscriptions from Este survive.Footnote 7

FIG. 1. Map of the Veneto region and schematic of the locations of sanctuaries in Este, after Balista and Ruta Serafina Reference Balista and Ruta Serafini1992. (Drawing: author)

Venetic was written in an adapted form of the Etruscan alphabet. It also derived some additional letters from the Greek alphabet to replace the letters representing the voiced stops and the vowel /o/, which had been dropped from Etruscan writing very early.Footnote 8 Most of the writing system is common to the whole region, but some of the letter shapes used in different areas are distinctive — for example, the different shapes of the sign for /t/ in Este and Padua. There was no single moment of transmission of the alphabet: Venetic writers stayed in touch with developments in Etruscan writing, including the emergence of a complex system of punctuation to mark any syllables not conforming to a C(onsonant)V(owel) structure.Footnote 9 This system of punctuation was picked up in the Venetic writing system around the fifth century and then maintained until the first century b.c., far outliving its use in Etruscan.Footnote 10 Around the late second or early first century b.c., Venetic started to be written in the Latin alphabet, sometimes still maintaining its system of syllabic punctuation. After the settlement of Actium veterans at Este after 31 b.c., the written language of the site changed to Latin.

The city of Este was surrounded by five extramural sanctuaries (Fig. 1); the five sanctuaries each appear to have been dedicated to a different deity or set of deities.Footnote 11 It has been hypothesised, based on the kinds of votives, that each sanctuary was also the religious focus for a different social group.Footnote 12 For example, the dedications of female figurines and images of adult women may show that Baratella was the focus of cult activity for women;Footnote 13 however, this is speculative, as this is the only sanctuary to provide inscribed dedications which name the deity or the people involved in dedicatory practices there.Footnote 14 At Baratella, which was in active use as a sanctuary from the sixth century b.c. to the third century a.d.,Footnote 15 the deity was a goddess named Reitia.Footnote 16

The vast majority of the dedications at Este-Baratella are uninscribed.Footnote 17 These include bronze figurines, some of which depict human figures, especially equestrians. The Venetic-speaking area also had a tradition of dedicating bronze sheets, known as laminae, which were cut into shapes or inscribed with pictures (Fig. 2), some of which were local variants of the common ‘anatomical votive’ tradition found across Italy at this time.Footnote 18 Other dedications include three-dimensional bronze anatomical votives, which are similar to terracotta examples found elsewhere.Footnote 19 The Atestine use of bronze for types of votives which were typically made of other materials elsewhere in Italy will be revisited in Section III, below.

FIG. 2. Bronze anatomical laminae from Este-Baratella, Museo Nazionale Atestino. (Photograph: author)

Three main forms of inscribed dedication are found at the Baratella sanctuary: inscribed stone statue bases, bronze tablets and bronze styluses. The eleven small stone statue bases were all dedicated by men; the bronze statues originally attached to these pedestals no longer survive, but one inscription indicates that they were statues of horses.Footnote 20 These statue bases show an aspect of Reitia which is not linked to literacy or to women, and it is important to keep in mind that Baratella was a sanctuary with a range of purposes, though this article will focus on the bronze inscribed dedications.

Bronze Writing-tablets

This group of inscriptions is made up of bronze writing-tablets (Figs 3 and 4), presumably purpose-made for dedicating to the goddess Reitia or related deities at the Baratella sanctuary near Este.Footnote 21 Except for Es 29, they have all been dated to around 350–150 b.c., mainly based on the form of the Venetic alphabet which they use.Footnote 22 Es 29 is written in the Venetic language using the Roman alphabet, and is dated to around 150–50 b.c.; Es 27 includes a Latin-language dedication formula and a Latin writing exercise, and may date to 200–150 b.c. Nine of the tablets are near complete (Es 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31), while eight are more fragmentary (Es 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39); where the tablets are complete enough that their dimensions can be determined, they measure approximately 95–165 mm in width and 128–200 mm in length.Footnote 23 Some were found folded, so that there are lines of damage to the texts, and some surfaces were oxidised.Footnote 24 The most complete tablets are rectangular, or rectangular with a semi-circular ‘handle’ attached to one of the sides, mimicking real writing-tablets, to which bronze handles could be attached.Footnote 25

FIG. 3. Es 25 (350–150 b.c.), Museo Nazionale Atestino. (Photograph: author)

FIG. 4. Es 25 (350–150 b.c.). (Drawing: author)

The texts inscribed on the tablets contain a mixture of elements, some of which look like writing exercises, and some of which specify that the purpose of the text is dedicatory. There are five typical elements, which occur in various combinations:

(1) a list of consonants in alphabetical order, often with one vowel at the end to bring the total to sixteen;

(2) the formula a ke o, written upwards and usually repeated sixteen times;

(3) the alphabet, in alphabetical order;

(4) a list of consonant clusters which do not require syllabic punctuation;

(5) a dedication formula using the verb donasto ‘gave’, usually naming the dedicator and the deity, and sometimes giving additional circumstances of the dedication.

Element (1), the consonant list, runs v d h θ k l m n p ś r s t b g, and usually appears at the bottom of the tablet.Footnote 26 This includes θ which is a dead letter at Este and most other Venetic-speaking sites — that is, it is found in abecedaria but is never used to write words. This alphabetical order suggests the rote learning of a model alphabet, which persisted for at least several generations after θ dropped out of use. The Marsiliana d'Albegna abecedarium (discussed below, Section III) shows evidence of a similar phenomenon in Etruscan education. On several tablets (Es 23, 24, 25, 26), the list of consonants is divided up into a grid of sixteen boxes. Since there are only fifteen consonants in the Venetic alphabet, the last box is normally filled with one more sign. For Es 23 and 24, the extra sign is e, for Es 25 it is ii (probably representing the digraph for consonantal yod) and for Es 26 it is a. It is possible that the vowel was chosen at random, though the digraph <ii> is a choice that indicates that yod could be considered to be an extra consonant. This represents an adaptation of the (presumed) underlying Etruscan model to suit Venetic, since there was no phonemic consonantal yod in Etruscan.Footnote 27

Element (2) is the formula a ke o, which normally appears in lines 2–5 of the inscription: it appears as one line of the repeated letter a, a second line of k, a third line of e, and a fourth line of o, with each letter written sixteen times. The significance of these letters has been debated in past work. The most convincing explanation is that the formula is ‘A and O’, the first and last letters of the Venetic alphabet:Footnote 28 though ke lacks a clear etymology, its use as a coordinating conjunction is unambiguous.Footnote 29 The phrase may have some magical or ritual significance, rather than being a learners' exercise.Footnote 30

Element (3), the abecedarium, shows the full alphabetical order used in Venetic: a e v d h θ k l m n p ś r s t u b g o. As in element (1), the letter theta is included even though it was a dead letter at Este. While Es 23 is the only example of a tablet which preserves the full Venetic alphabet,Footnote 31 two examples, Es 29 and Es 27, probably from the latest end of this corpus, include the Roman alphabet. Es 29 consists only of a dedication formula and an abecedarium. As the inscription does not include y and z, it was probably written before the Augustan period: [a] b c d e f g h i k l m n o p q r s t v x. In the Roman alphabet on Es 27, the letters appear out of order, taking the letters from each end of the alphabet in turn and working towards the middle. This reconstruction was proposed by Prosdocimi on the basis of techniques described by Quintilian, who advised teachers to scramble the letters out of sequence to make sure they had been fully learned (see Section IV).Footnote 32 If this abecedarium is correctly reconstructed, then this represents key early evidence for Latin-language as well as Venetic-language elementary education at this site, as well as possible evidence for bilingual education.Footnote 33

Element (4), a list of consonant clusters, appears on most of the tablets (Es 23, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32, 33, 34, 39) in a similar but not identical order, and the clusters are not the same on every tablet.

Es 23: [v]hr vhn vhl vh dr dn [d]l θr θn θl kr <k> n kl kv mr mn ml pr pn pl śr śn śl sr sn sl tr tn tl br bn bl gr gn gl

Es 24: [v]hr vhn vhl vh dr dn dl θr θn θl kr kn kl kv mr mn m[l] pr pn pl śr [śn ś]l sr sn sl tr tn tl br bn [b]l gr gn gl

Es 25: vhr vhn vhl kr kn kl θr θn θl dr dn dl mr mn ml pr pn pl śr śn śl sr sn sl kr kn kl kv vh br bn bl gr gn gl

Es 26: vhr v[hn vhl vh] tr tn tl kr kn k[l mr mn ml] pr pn pl śr śn śl sr sn [sl] dr dn dl br bn bl gr gn gl kv

Es 31: [v]hr vhn vhl vh [dr dn dl θr θn θl kr k]n kl mr [m]n ml pr pn [pl śr śn śl sr sn sl tr] tn tl br bn bl gr gn g[l]

Es 32: ]sr sl t[n

Es 33: ]kn kr [

Es 34: [vhr vhn vhl vh? dr d]n dl θr θn θl kr k[n kl kv? mr mn ml pr pn pl śr śn] śl sr sn sl tr tn tl br bn bl g[r gn gl]

Es 39: [kl k]n kr [----- / ----- ś]l śn [śr ----- / -----] b[

These clusters are not randomly chosen: they are the consonant clusters which do not require special marking under the Venetic syllabic punctuation system.Footnote 34 This would, no doubt, have been something that required practice when learning to write in the Venetic alphabet, and therefore they make a very plausible writing exercise for learners. It is also possible that these clusters show some evidence of independent developments away from the Etruscan model for the exercise. For example, the sequence tends to have b- and g- clusters towards the end of the list, in accordance with Venetic rather than Etruscan alphabetical order, although the sequence is not always strictly alphabetical. That said, this cluster list may continue to adhere to an underlying Etruscan model in some respects, despite differences in Venetic writing habits. For example, there are no clusters with i/ii (yod) listed, although syllables like siio and tiio tend to be unpunctuated in Venetic texts.Footnote 35

In several examples (Es 23, 24, 25, 34), θ has been included in the list of consonant clusters despite its status as a dead letter. In Es 26, though, theta has been missed out, t has been moved to the position normally taken by theta and d has been moved to the position usually taken by t. The consonant cluster list in Es 26 therefore differs in alphabetical order from its consonant list, which includes theta. This may show the clash of two slightly different alphabetical orders which were current at the same time — the model alphabet vs the alphabet for everyday use — again perhaps showing signs of deliberate adaptation of the educational exercises to fit Venetic writing habits.

Element (5) is the dedicatory formula,Footnote 36 which most commonly consists of (a) a verb, usually dona.s.to ‘gave’ but also doto ‘gave’,Footnote 37 or the two coordinated verbs [do]na.s.to ke la.g.[s.to] (Es 27),Footnote 38 and (b) an accusative naming the inscription, usually mego ‘me’ or vda.n. ‘alphabet’.Footnote 39 Typically, the inscriptions also name a dedicator and the deity to whom they are dedicated, but these elements are not compulsory. A few mention relationships between individuals, such as <v>ḥratere.i. ‘brother’ (Es 28) and lo.u.derobo.s. ‘children’ (Es 45). Some also have additional information about the circumstances of the dedication, including phrases of uncertain meaning such as .o.p vo.l.tiio ‘because of a voluntary (act) (?)’ (*Es 125), o.p. vo.l.tiio leno ‘because of a voluntary act (?)’ (Es 27, Es 32, Es 44) and o.p. iorobo.s. ‘because of [dative plural noun]’ (Es 23, Es 69).Footnote 40 A typical formula (Es 23), naming both the dedicator and the divine recipient, reads as follows:

mego dona.s.to .e.b. vhaba.i.tśa pora.i. o.p iorobo.s.

I-acc.sing. give-aor.3.sing. unknown.abbreviation Fabaitśa-nom. Pora-dat. because.of unknown-dat.pl.

Fabaitśa gave me to Pora [abbreviation] because of [plural ?deity]

The layout of the text as a whole shows the prominence of the writing exercises in the text. The complete text of Es 23 (Figs 5 and 6) is as follows:Footnote 41

FIG. 5. Es 23 (350–150 b.c.), Museo Nazionale Atestino. (Photograph: author)

FIG. 6. Es 23 (350–150 b.c.). (Drawing: author)

This transcription starts at the top left of the drawing (see schematic in Fig. 7). There are several changes of direction — for example, a ke o is read across lines 2–4 — and of orientation, so that the tablet needs to be rotated to read all the elements.Footnote 42 Line 6, for example, turns a corner twice, and the reader would need to turn the tablet to read it easily. This may show how wax tablets were used by learners, but it is also possible that this was an elaboration of the writing exercises for decorative purposes or for some other reason connected to the process of dedication and was not typical of learners' writing.Footnote 43

FIG. 7. Schematic of direction of writing in Es 23. (Drawing: author)

Bronze Styluses

Another common form of dedication at the Baratella sanctuary is the bronze stylus.Footnote 44 There are twenty-five inscribed styluses, and many pseudo-inscribed examples. They are oversized, mostly ranging from 175 to 260 mm long, suggesting that they are purpose-made dedications rather than real styluses (see Section III); the largest examples would be heavy and unwieldly for everyday writing.Footnote 45 The styluses do not have the alphabets, consonant lists and consonant clusters found on the writing-tablets, but their dedicatory formulae are the same. A typical example is Es 44 (Figs 8 and 9):

mego doto vhu.g.siia votna śa.i.nate.i. re.i.tiia.i. o.p vo.l.tiio leno

I-acc.sing. give-aorist.3.sing. Fugsiia-nom. Votna-nom. Śainatis-dat. Reitiia-dat. because.of voluntary-instrumental.sing. act-instrumental.sing.

Fugsiia Votna gives me to Śainatis Reitia because of a voluntary act.

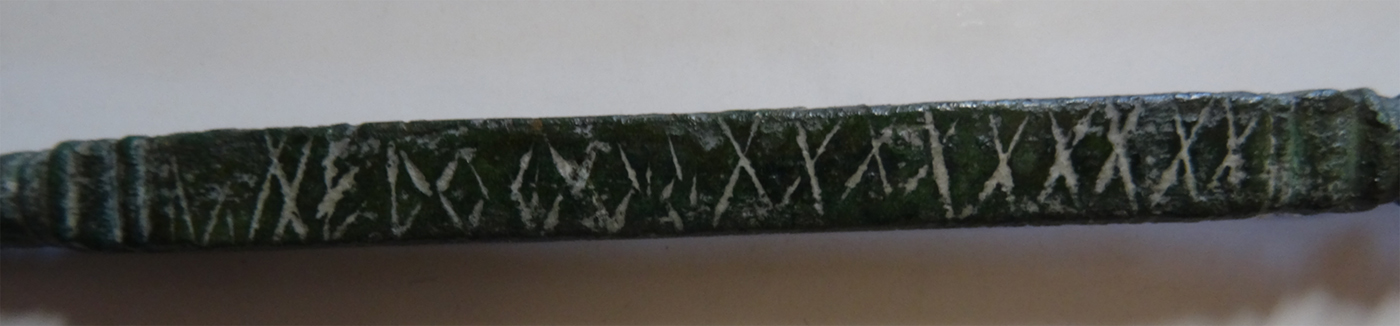

FIG. 8. Es 45 (350–150 b.c.), Museo Nazionale Atestino. (Photograph: author)

FIG. 9. Es 45 (350–150 b.c.), Museo Nazionale Atestino; close-up of side 4. (Photograph: author)

The pseudo-inscribed examples are decorated with symbols which, in some cases, look like repeated letters of the alphabet, such as the repetition of <XXXXX> (or, in Este's alphabet, ttttt) along the length of the stylus. In these cases, these may be real repetitions of significant letters of the alphabet rather than pseudo-writing, as we see on the writing-tablets with a ke o. If these letters are meant as t, its appearance on many of the styluses might be meaningful. Several of the inscribed examples of dedicatory styluses also have extra letters filling up empty space at the ends of lines, or filling the sides that are left uninscribed. For example, Es 45:

III WRITING AND WRITING TOOLS AS VOTIVE DEDICATIONS

DedicationsFootnote 46 come in many forms: two distinctions which are relevant to this discussion are (a) whether or not the votives were purpose-made for dedication, and (b) the occasion or stage in the human-divine relationship at which they were dedicated. I will argue that it is likely that the bronze tablets and styluses were purpose-made and represent only the most expensive and durable end of a wider practice of dedicating writing equipment at Este-Baratella and, perhaps, more widely in Italy. We cannot tell, however, whether they mark the achievement of basic literacy, an aspiration to learn or some other occasion.

Dedications of Writing Tools — Purpose-made or Non-purpose-made?

Votive dedications can be divided into ‘purpose-made’ and ‘non-purpose-made’ (to use Hughes' terminology).Footnote 47 ‘Purpose-made’ dedications are produced to be used as such, and have no previous existence. In many cases, these dedications were produced by craftsmen near the sanctuary, sometimes using mass-production techniques; they range from small and affordable to large and elaborate, but always involve an economic outlay for the dedicant. Non-purpose-made votives include personal belongings such as tools, clothing, jewellery, loom-weights, hairpins, toys, weapons, tools and hair, and whatever their intrinsic value, they do not normally involve any new economic outlay for the dedicant. Many non-purpose-made votives were of perishable material, and so these types of offering are often less archaeologically visible.Footnote 48 It is possible that some of the styluses were non-purpose-made votives. However, as shown above, it seems likely that these examples are purpose-made oversized reproductions, made specifically for dedication with flat sides with enough space for a clear dedicatory inscription. Purpose-made or non-purpose-made styluses made of other materials, such as wood or bone, may also have been dedicated but do not survive.

The bronze writing-tablets are more clearly purpose-made dedications — a bronze tablet of this kind could not genuinely be used for a writing exercise. However, the level of participation of the dedicant in the object's production is hard to gauge. In most of the extant examples, it would be possible for all of the writing apart from the dedicatory formula to come pre-prepared, with the formula added at the dedicant's request at the time of purchase. But it is also possible that the tablets were produced blank, and that the dedicant had more input into the exercises which were included, which might explain some of the differences in the abecedaria and lists of consonant clusters between the different tablets. The dedicatory formulae are often found in the middle of the text, and might have been difficult to add later — in Es 23 (Figs 5–7), the last four lines of exercises seem to have been written to fit around the dedication formula — suggesting that dedicators were involved in commissioning the whole text in some cases. It is also likely that these bronze writing-tablets constitute only the most enduring end of a wider practice of dedicating real waxed or wooden tablets, which might more plausibly have been written in the dedicator's own hand.

To support the hypothesis that the bronze writing-tablets were offered alongside analogous non-purpose-made dedications, we need to consider other evidence of writing and writing implements as dedications. The written word can have a power which makes it — and the tools that produce it — an appropriate dedication in its own right.Footnote 49 The dedication of writing implements is known from elsewhere in the ancient world. The literary evidence is meagre, and is mainly limited to epigram. For example, in the Greek Anthology, there are seven examples of dedications of writing tools (Anth. Pal. 6.63–8, 295). Six of these poems were composed much later, but the earliest and perhaps the original epigram on this theme is by Phanias, who is thought to have lived in Italy around the second or first century b.c.Footnote 50 The dedicated items mentioned include lead, pens, rulers, ink-wells and ink, all of which have clearly been heavily used: for example, pens are often described as ‘blackened’. This provides a clear non-purpose-made comparandum for the purpose-made oversized, inscribed styluses found at Este-Baratella.

Writing-tablets themselves are not mentioned as dedicated objects in the poems of the Greek Anthology. However, wax tablets would have been a common sight in many ancient sanctuaries because of their use as a written record of prayers or promises by the dedicants.Footnote 51 They were a cheaper alternative to stone inscriptions at many Roman sanctuaries, but their lack of survival means that their range of uses as votives is not fully understood.

When and Why Were Writing Materials Dedicated?

Votive offerings can be made before, during or after the god doing something favourable, or to commemorate various kinds of personal milestones.Footnote 52 In the Greek Anthology, the dedicants of writing materials are all male scribes retiring from work. But this is not the only time in one's life at which a dedication of writing materials might be made. It is possible that dedications of tools could also be made to celebrate a new or long-standing skill.Footnote 53 There are literary examples of dedications of items other than writing tools to celebrate literacy, or particularly outstanding achievements in literacy: for example, in an epigram by Asclepiades (c. third century b.c.), Konnaros has won a writing competition, apparently among relatively early learners, in which his handwriting has been particularly praised.Footnote 54 The dedication he makes to the Muses is not one of writing tools, but a comic mask which, perhaps, evokes the higher-level literary education he will go on to receive now that he has mastered this stage. Though the evidence is limited, this suggests that acquisition of literacy, or particularly outstanding achievements during elementary education, could conceivably be celebrated with dedications.Footnote 55

The timing of the dedications of the bronze Venetic writing-tablets is not clear: the dedications might be either aspirational or celebratory, but they are likely to have some connection to education. It is often, correctly, argued that the shapes of dedications should not be taken literally — e.g. an anatomical votive in the shape of an ear need not indicate ear-acheFootnote 56 — but dedications of writing materials were nevertheless chosen by the offerant to reflect something about their own life experience and their relationship with Reitia. Given that the main literary evidence for the dedication of writing materials is connected with professional writers, it would seem a stretch to claim that the dedicators of these texts had no involvement with literacy at all. In light of the available comparanda, we can at least say that it is possible that there was a wider practice at Este of dedicating writing tools to mark some kind of personal milestone, of which only the most expensive purpose-made bronze items survived.

Writing Exercises as Prestige Objects

The Atestine practice of dedicating writing exercises suggests that the exercises were considered worthy of being dedicated to a deity, but ancient examples of an explicitly high value being placed on learners' exercises are not particularly common. However, there are a few clear examples of abecedaria and writing exercises being deliberately placed in votive or other ceremonial contexts, and these are worth considering alongside the examples from Este-Baratella. The most famous replica of a writing-tablet is found in a funerary, rather than a dedicatory, context. The Marsiliana d'Albegna alphabet (Fig. 10) is an expensive, purpose-made replica of a writing-tablet, usually dated to the second or third quarter of the seventh century b.c.Footnote 57 The tablet is sometimes discussed as though it was a real writing-tablet which was buried with its user, because traces of wax remained on the central field when it was discovered.Footnote 58 However, its very small size (88 by 50 mm) makes this unlikely — it would be difficult for a learner to write more than one or two letters — and so it is more likely to have been purpose-made for burial.Footnote 59 The tablet was found alongside other ivory writing implements, including small styluses and erasers.Footnote 60 The alphabet written on the Marsiliana tablet is probably best understood as a copy of a ‘guide’ alphabet written on the frame of a writing-tablet to help the learner; this fits with the accounts of Plato and Quintilian, both of whom mention learners tracing example alphabets (see Section IV). This writing-tablet shows the prestige associated with writing implements in Etruria during this early period, and shows that copies of these objects were produced in Italy for ritual purposes.

FIG. 10. Marsiliana d'Albegna writing-tablet. (Drawing: author)

A number of other Etruscan texts show writing exercises on bucchero and other ceramic objects in elite burial contexts.Footnote 61 Some include short formulae naming the owner alongside the abecedarium, e.g. Ve 9.4, while others include more elaborate writing exercises. For example, the Formello amphora, a bucchero amphora found near Veii in the same high-status tomb as the famous Chigi vase, is inscribed with several texts: two abecedaria, a formula indicating that it was a gift, and additional text which has been interpreted variously as a magical formula or writing exercises combining the letters u a r z ś.Footnote 62

A few texts also show short series of syllables, suggesting writing exercises: for example, the bucchero ‘ink-well’ from Caere, probably some kind of flask, also found in a burial context (probably the Regolini and Galassi tomb).Footnote 63 This text has a full abecedarium, though q has been forgotten; b also faces backwards with respect to the other letters, suggesting that this is a learner's writing.Footnote 64 There then follows a series of syllabic exercises, combining each vowel (in the order i a u e) with each consonant, at first in alphabetical order, though order breaks down at the end of the sequence. Dead letters are excluded from this syllabary.Footnote 65 A small number of uninscribed bucchero imitations of writing-tablets have been found at Chiusi and other sites; they are usually associated with burial assemblages which include many other bucchero imitations of everyday objects.Footnote 66 These are in a ‘tabula ansata’ shape, with two notches on each long side so that the tablets could easily be tied together with string, mimicking a real wooden tablet. Looking beyond funerary contexts in Italy, evidence of votive writing exercises appears at the Etruscan sanctuary of Portonaccio near Veii in Latium. Large numbers of inscribed votives to Minerva, dating to the last quarter of the seventh century and the first half of the sixth century b.c., have been found, some of which are in the form of abecedaria; these texts have suggested to scholars that the sanctuary was a centre for the acquisition of literacy.Footnote 67

However, writing exercises in confirmed dedicatory contexts are rare. Scratched abecedaria on walls and small objects, such as those found at Pompeii (in both Oscan and Latin) and those found in the Greek-speaking world from the eighth century b.c. onwards, are usually interpreted as informal practice texts, and not as dedications.Footnote 68 It is possible that some of the abecedaria which have been identified as educational texts may have had a votive or other ritual purpose which has not been recognised by modern editors.Footnote 69

To find clear examples of the dedication of writing materials and exercises it is necessary to look outside Italy. A number of notable examples of this practice are found in the rock-cut sanctuaries of the Iberian Peninsula, using both the Greek alphabetFootnote 70 and the Iberian semi-syllabic script, which have been identified as alphabetic votives.Footnote 71 While none of these abecedaria are as complex as the writing exercises shown on the Este-Baratella tablets or the Etruscan bucchero vessels, they suggest that abecedaria could be used in votive contexts. Abecedaria in magical texts (mainly dated much later) might also qualify as examples of the use of the power of writing to communicate with a deity.Footnote 72

A particularly important example of the dedication of learners' writing exercises is the cult of Zeus Semios on Mount Hymettos near Athens.Footnote 73 At this sanctuary site, which consists of a deep hollow about 1.5 km from the peak, many small votive potsherds were dedicated. Two examples name the deity as Zeus Semios (‘Zeus of the Signs').Footnote 74 Most of the other sherds (c. 160) are inscribed with partial abecedaria, usually three or four letters long. In general, the appearance of the texts suggests inexperienced writers;Footnote 75 it is not clear whether they were purpose-made for dedication, or whether they were real writing exercises which were ceremonially discarded by their authors. The ostraka which bear the inscriptions are worthless in themselves, and several scholars have suggested that the writing itself is the key factor in creating a relationship with the deity.Footnote 76 Whatever the exact motivation of the dedicators, it has been argued that these dedicatory texts speak to the exceptional relationship that archaic Athens had with literacy, particularly during the period when writing was still a rare skill in the region.Footnote 77 However, as we have seen, not all votive practices connected to learning to write exist in societies where writing is a new technology, and it may be that these texts are later than they at first appear.Footnote 78

As this survey shows, there are no exact equivalents of the Venetic dedications to Reitia elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Although abecedaria, writing exercises and writing implements appear in burial and dedicatory contexts beyond the Veneto, it is only at Este that we seem to get such expensively and deliberately produced replicas of writing-tablets. This is a localised dedicatory practice which, nevertheless, we can see as part of a wider Mediterranean context in which writing, including learning to write, could be the focus of votive activity. It is plausible that Venetic practices included the dedication of wooden writing-tablets as non-purpose-made votives, similar to some of the ceramic examples found elsewhere, and that purpose-made bronze tablets were the most expensive extreme of a more varied and accessible set of votive practices. It is also possible communities elsewhere in Italy were dedicating real writing-tablets made of wood and wax. The difference between the various elites of Italy was not always the kind of written texts which they produced, but the materials on which they produced them, with profound effects for the archaeological record — see, for example, the vast differences in the preservation of written laws in different areas.Footnote 79 It is possible, therefore, that writing tools made of wood and wax were dedicated both at Este and elsewhere. Perhaps the people of Este were unusual not in dedicating writing materials, but in their extensive use of bronze for categories of votives which elsewhere were made of materials such as ceramic (cf. the writing exercises at Caere, bucchero ‘writing-tablets' at Chiusi and anatomical votives at many sites) or wood.

IV EVIDENCE FOR ELEMENTARY EDUCATION IN ITALY

Evidence for Writing Exercises

The interpretation of the votive dedications to Reitia in Section III relies, in part, on the texts on the bronze tablets being recognisable copies of the writing exercises completed by learners during their acquisition of literacy, or model exercises written by teachers. To judge the plausibility of this claim, we need to turn to comparative evidence from elsewhere in the ancient world. The few existing descriptions of the acquisition of basic literacy in Greek and Roman literature do not, in general, go into much detail about teaching techniques. As part of an extended metaphor, Plato describes schoolchildren of the fourth century tracing letters written faintly by their teachers (Prt. 326d) and progressing from learning their letters to reading works of poetry (325e); this process typically happened in childhood (326c).Footnote 80 Elsewhere, Plato's Socrates indicates that in Greek education the letters were learned first, and then combined into syllables (Tht. 202e–204a). Dionysius of Halicarnassus, writing in the time of Augustus, also describes the progression from letters to syllables to words (Comp. 25).

The evidence from Italy is limited, and there is little information about how people learned to write before the Augustan period.Footnote 81 In the first century a.d., Quintilian, drawing on Greek education, reiterates the idea that children should trace letters with their pen (Inst. 1.1.27). He mentions in addition the benefit of teaching the alphabet in a scrambled order, so that students have to recognise the shapes and not just the sequence (1.1.27).Footnote 82 It is possible that this practice is found in the Roman alphabet on tablet Es 27, if Prosdocimi's reconstruction is correct, and that the scrambling on this tablet is mainly educational rather than magical. Like Plato, Quintilian also emphasises the importance of the syllable — he says that every syllable must be learned individually, and that when children start to read words they should be encouraged to break them into syllables (1.1.30–3). In On Order, Augustine describes the sequence of education, from learning letters to learning syllables, as immutable.Footnote 83 This system is also implied in the description of the school day in the Colloquia Monacensia-Einsidlensia.Footnote 84 These passages give us a basic framework for how Greek and Roman elementary education might have progressed — from letters to syllables to poetry or other texts; they all emphasise that understanding different syllable structures was an important stage of the learning process. They do not, however, give us much detail about the exercises used at each stage — fortunately, extant epigraphic and papyrological evidence complements these accounts.

The many surviving school exercises from different educational levels show remarkable consistency across time and space.Footnote 85 Some of the most complete sets of basic literacy exercises from the ancient world are Hellenistic examples roughly contemporary with the Venetic dedications to Reitia.Footnote 86 For example, the text known as the ‘livre d’écolier’ (‘school-child's book’) is a series of papyrus fragments purchased in 1935,Footnote 87 dated to the final quarter of the third century b.c. based on the palaeography.Footnote 88 This book, and other comparable papyrological texts, gives us a much more complete idea of the system of exercises Plato and Quintilian had in mind when describing the learning process.Footnote 89 It also provides a useful point of reference for the Venetic dedications as examples of learners' texts. The text of the ‘livre d’écolier’ consists of a series of writing exercises, written out by a teacher as a pedagogical aid. The papyrus gives a series of tables, each building on the skills learned in the previous section. The first table is a list of open syllables, constructed by adding each consonant to each vowel in turn. This section is fragmentary but the pattern is clear from the remains of two of the columns:Footnote 90

The second table introduces closed syllables ending in <ν> and then closed syllables beginning with consonant clusters and ending in <σ>:Footnote 91

The text then goes on to give words of one syllable with several consonant clusters (some of which are nonsense words or onomatopoeia), followed by names of two, three, four and five syllables. The use of these single-syllable words is paralleled in educational texts elsewhere, such as a (possible) teacher's model and student's copy of the same exercise on an ostraka from southern Gaul in the third or second century b.c., which includes a partial abecedaria and the word κναξ, which is also found in the ‘livre d’écolier’ one-syllable word list.Footnote 92 The book's polysyllabic words and names are divided into syllables using punctuation. For example, Ο : δυσ : σευς and Τευ : κρος. It then proceeds to a small anthology of passages from poetry, including excerpts from Euripides, the Odyssey, new comedy and a selection of epigrams, and some word lists.Footnote 93

The pedagogy of Greek elementary education comes through clearly in this text and others like it.Footnote 94 The book may have begun with an alphabet or alphabets, but if it existed this section is now lost. However, we can see that the next stage after the acquisition of the alphabet is focused on the syllable. The syllable structures are made progressively more complex: teaching starts with the mechanical creation of every possible open syllable, then a few types of simple closed syllables, progressing towards syllables with multiple consonant clusters. In many cases, these syllables were ones which never or rarely occurred in real words.Footnote 95 Only when these different types of syllable were mastered did the student move on to multiple syllable words, in which the different syllables were clearly separated out by punctuation. Even in the first extract of the poetic anthology, the syllables are punctuated for the student. For example:Footnote 96

We see the same focus on syllable structure in the Venetic dedications to Reitia. These exercises do not cover the same section of the learning process as the Greek-focused ‘livre d’écolier’, but show a similar pedagogical framework. The Reitia inscriptions show that the next stage after learning the alphabet itself was to think about syllable structure and consonant clusters, rather than progressing straight from the alphabet to words. In the case of the Venetic writing system, there was a specific set of clusters which had to be rote-learned for the purposes of syllabic punctuation, and as a result the progression of the exercises is not exactly the same as those found in Egypt. Nevertheless, the similar focus on syllable structure and consonant clusters in both the Venetic dedications and a Greek learning aid suggests that the dedications are accurate copies of real writing exercises of the period.

Abecedaria and repeated letters are also commonly used in Greek learners' exercises. For example, we find the use of repeated letters in a papyrus example from the fifth or sixth century a.d., where the student has written α α α ελ η η η ελ ελ ελ ρ ρ ρ ρ ρ.Footnote 97 An even closer parallel is found, both in form and in chronology, in some examples from Greek settlements on the Black Sea from the fifth to the third centuries b.c., which show abecedaria, or just the repeated letters α β γ, enclosed in a grid just like in the Venetic tablets.Footnote 98 This suggests that some teachers may have provided grids to help very early learners to write clearly. Evidence from Egypt shows that wooden or waxed tablets, which could be passed around easily, were a common material for teachers' models, while students used ostraka or offcuts of papyrus;Footnote 99 one could argue, therefore, that the bronze Venetic tablets mimic teachers' models rather than student exercises.

At a slightly earlier period to both the Venetic examples and the Egyptian ‘livre d’écolier’, there is evidence of writing exercises in Etruria. Section III mentioned the syllable exercises which appear on bucchero objects, such as the flask from Caere with its model alphabet and open syllable sequence. None of the Etruscan lists of syllables is as complex as the exercises in the papyri or in the Venetic dedications.Footnote 100 These examples also cluster around the seventh and sixth centuries b.c., predating those from Este. Nevertheless, these examples show that writing exercises based on systematic series of syllables were used in Italy, and that elementary education at Este could plausibly be built on this system.

This is not to say that Venetic systems of education were directly reliant on the Greek or Etruscan worlds. As already noted, the Venetic writing system had peculiarities which necessitated certain types of exercises for learners, including the retention of exercises for learning syllabic punctuation for several centuries longer than in the Etruscan world. The texts also show signs of continued adaptation in the loss of dead letters and the changes to the alphabetical order in the exercises. However, these comparisons help us to put Venetic elementary education into its Italian and Mediterranean context as part of a wider culture of pedagogical practices.Footnote 101 It is plausible that the teaching of literacy in the Venetic world followed systems that were not dissimilar to those found in the Hellenistic world and Etruria, and that, as with the Venetic alphabet itself, there was ongoing interaction between these systems rather than a single point of transmission.

Who Learned to Write and Why?

In past scholarship, it has often been suggested that the most plausible explanation for the number of dedicatory writing implements at Este-Baratella is the presence of an important scribal school at Este, either at the sanctuary or nearby.Footnote 102 However, the large number of women's names in the nominative, which implies that women were frequent dedicators of these kinds of texts, makes scribal training less likely to be the only reason for these dedications.Footnote 103 Most of the texts have a named dedicator, although in some cases the dedicator's name is omitted on purpose or missing through damage. A few names cannot be reliably identified as male or female. Other names have damage which prevents us from seeing the morphological ending and therefore the gender of the name. Despite these problems, we can see that women are found as dedicators for three of the extant writing-tablets (versus eight men) and that only women are attested as dedicators of styluses. Some texts also have additional named persons who are ‘beneficiaries' of the dedication. The only example of this practice in the writing-tablets shows a male dedicator making a dedication to at least one male beneficiary (probably two). For the styluses, all but one of the beneficiaries are also female: the exception is Es 45, where a woman Egetora makes the dedication .<a > .i.mo.i. ke lo.u.derobo.s. ‘for Aimos and (their) children’.

Table 1 Male and female names in the dedications to Reitia.

The association between women and writing materials is particularly strong, since other kinds of objects dedicated to Reitia do not name women as their dedicators or beneficiaries. Most of the other inscribed dedications at Este, as mentioned in the introduction, are stone pedestals topped with bronze statues, probably mainly equestrian statues. All of these are dedicated by men, where a dedicator is named. The handful of inscribed dedications of other kinds (a bronze kantharos and two freestanding stones) are also dedicated by men. This sanctuary does not just show an association of women with Reitia — since Reitia had other strings to her bow — but an association of women with the specific aspect of the goddess relating to writing and learning to write. We do not know the gender of the dedicators of the uninscribed votives, such as the anatomical votives, but the majority of the statuettes, for example, show female figures, which may suggest women's involvement in other aspects of the sanctuary as well. Given this evidence, it is misleading to try to make scribal training the main focus of the dedicatory activity at Este-Baratella. This approach plays down the other facets of the goddess, as well as reducing the role of women as active participants in religious activity at the sanctuary.

The effect of this focus on scribal training has been to minimise elite Venetic women's participation in literacy and the epigraphic habit.Footnote 104 Instead, women should be re-centred in the analysis of votive practices at Este, both in their role as dedicators and in their association with the educational aspect of Reitia. Class is just as important as gender in understanding their role. As Cribiore has emphasised, ‘wealth and social status were even more determinant education factors for females than for males. A disproportionately high percentage of girls who completed the first educational level were elite, as compared to the more varied social backgrounds of male students.'Footnote 105 As argued above, the dedication of bronze votives was an elite activity, and may be the visible remains of a wider practice which included the dedication of wooden writing tools; the association of elite women with this practice fits with Cribiore's evidence.

At Este, a unusually high proportion of the surviving funerary monuments commemorate women, though they were still in the minority.Footnote 106 Although these monuments were not written by the women that they memorialise, this contributes to our picture of a culture in which women were highly involved in the epigraphic activity of the city, in contrast to many other regions.Footnote 107 The combination of women's visibility in dedications which explicitly reference learning to write and their frequent commemoration on gravestones also makes Este qualitatively different from areas of Italy where women's names are commonly found on gravestones but rarely in other kinds of written text. In these areas — such as the Paelignian-speaking area around Corfinium and Sulmo — it is easier to put the visibility of women down to the habits of elite display among their male relatives, who would have had primary responsibility for the burial.Footnote 108 It is not easy to make a similar case for women's participation in Reitia's cult: the role of dedicators in votive dedications is more participatory than the role of the deceased at a burial. I would argue that their involvement in dedicating writing-tablets indicates that women did learn to write, and that their dedications commemorated either their skill or (perhaps) their aspirations. Este, like parts of Etruria, may therefore have been a culture in which basic literacy among the elite was not so dependent on gender as it was in Greece and Rome.Footnote 109

The involvement of women in epigraphic culture has sometimes been treated as an incidental oddity, and perhaps a highly localised phenomenon peculiar to Este. Another approach, however, would be to look more broadly at literacy in the rest of first-millennium Italy, and to note that the Venetic dedications may be part of a wider network of evidence for women's writing. We should note, for example, that women and their daily activities are associated with writing from the earliest stages of alphabetic writing in Italy, particularly in Etruria.Footnote 110 From as early as the eighth century, spools, spindlewhorls and loom-weights — objects associated with textile production, and therefore with the economic activities of both elite and non-elite women — are found marked with Greek or Etruscan letters.Footnote 111 Another non-elite example is the late second-century b.c. Oscan/Latin bilingual inscription from Samnium, which shows two female tile-factory workers, probably slaves or freedwomen, using writing casually to inscribe short messages in the wet clay of a tile.Footnote 112 A text on a small bucchero perfume vase which might be characterised as ‘a short Etruscan poem’, signed by a woman, has been found at Caere and dated to the end of the seventh century.Footnote 113 There were strong links between the cultures of literacy in Etruria and the Veneto, and the participation of women in literacy may have been similar in the two regions.

More evidence exists for female participation in elementary education in the ancient world generally than is sometimes appreciated; the fact that many ancient authors were more interested in boys' education should not lead us to forget that in some places in the ancient world, women were regularly educated at elementary level. Cribiore cites an inscription from Xanthus, Lycia, in the second century a.d. which clearly mentions the availability of free education for both boys and girls — uptake from girls might have been lower, but the provision was available.Footnote 114 Eight of the eighty-seven references to ‘teachers' in the Egyptian papyri refer to women, although some of these may refer to people taking on apprentices rather than those teaching basic literacy specifically.Footnote 115 The famous first-century a.d. mummy of Hermione Grammatike, now in Girton College, Cambridge, is perhaps another example of a woman being named as a teacher.Footnote 116 The image of two girls on a fifth-century b.c. Attic kylix has also been used as evidence for Greek women attending school, although it is difficult to interpret this image.Footnote 117

Even in Roman Italy, where it is generally accepted that female literacy was much lower than male literacy, there is evidence that some non-elite women participated in education as both learners and teachers. A number of literary texts incidentally mention girls as pupils or readers.Footnote 118 In Apuleius' Metamorphoses one woman refers to another as a ‘school-mate’ or ‘fellow-pupil’ of hers.Footnote 119 Six examples of female pedagogues are known, four from Rome (CIL 6.4459, 6331, 9754, 9758), one in Samnium (CIL 9.6325) and one in Africa (CIL 8.1506);Footnote 120 one is also mentioned in the Oxyrhynchus papyri (P.Oxy. 50.3555). Pedagogues accompanied children to school, but also sat with them during lessons, helped them with their work and set additional exercises — this was a job with low pay and social status, but some skill was involved.Footnote 121 The inscriptional evidence reveals that this was a position which could be held by free or freed women (free: CIL 6.9754; freed: CIL 6.6331; others not stated) at various ages, assuming that at their death these women had been pedagogues recently (CIL 6.9758 died aged twenty-five; CIL 8.1506 died in her seventies). The inscription CIL 6.9754 seems to record two (or more) sisters commemorating their two pedagogues, one male and one female.Footnote 122

So, if the Venetic dedications are not necessarily the result of a scribal training school, can we associate them with any kind of education being provided outside the home? As shown above, writing exercises analogous with, though not identical to, those found on the dedication tablets at Este-Baratella are found in contexts elsewhere in the Mediterranean which suggests that they were part of the semi-organised elementary education of elite people, often assumed to be children, particularly boys. It is plausible that a similar system of teaching literacy to small groups was also in use in the Veneto in approximately the fourth to the second centuries b.c. Teaching may have occurred at the Baratella site itself, but need not have done. The names on the dedications suggest that these groups may have included girls as well as boys, and perhaps also married women with children, if Es 45 refers to the dedicator's own husband and children.Footnote 123 Although the Venetic sources only give direct evidence of elite dedicatory practices, it is possible that both men and women of other social groups learned to write and made dedications on perishable materials.

V CONCLUSIONS

The dedications to Reitia at Este-Baratella are a unique form of dedicatory practice, whether we interpret these dedications as celebrations of the end of the process of acquiring literacy, markers of educational milestones or aspirations to learn. They also give a rare insight into how basic literacy was taught in ancient Italy from the fourth to the second century b.c., both in Venetic and Latin. However, as evidence of both dedicatory and educational practices, the dedications to Reitia need to be seen in their wider Italian and Mediterranean context. As dedications, these texts are perhaps best seen as an unusually elaborate form of a practice found across many different languages and cultures in the ancient world. Examples from Greece, Iberia and elsewhere show that votive abecedaria could exist without more complex writing exercises; practices in Etruria are probably the closest match for the inscriptions at Este-Baratella. The Venetic evidence also provides a helpful counter-example to the idea that such dedications only occurred in Greece, or only in areas which had recently adopted alphabetic writing.

As educational texts, the Este-Baratella tablets are easiest to understand when seen as part of a wider network of individuals acquiring literacy across the Mediterranean, including in Etruria, Greece and Rome. By making these comparisons, we can build up a wider picture of the exercises that were used at the different stages of the acquisition of literacy, and how these exercises were adapted to the needs of different writing systems. On the whole, ancient education devoted considerable time to understanding the syllable and different syllabic structures, rather than progressing straight from letters to words. This was particularly important in writing systems like Venetic and Etruscan, where the syllable formed the basis of the punctuation system, but is also seen in Greek and Roman education.

Finally, the role of women in the production of these dedications should not be underestimated. Like any purpose-made dedication, the bronzes were probably not produced by the dedicators named on them; but those dedicators, whether male or female, did decide to commission a dedication in the form of a writing implement, and may have had input into the text. Although past scholarship has sometimes tried to minimise the roles of women, based on an assumption that their participation in literacy in ancient Italy must have been very low, these dedications provide evidence that some elite women at Este-Baratella were literate — or, at the very least, were active participants in a dedicatory practice which celebrated elementary literacy. The epigraphic habit of Este appears to be unique in some respects, and so it is very difficult to say what implications these texts have for female literacy in the rest of the Veneto or the rest of Italy. However, the Este-Baratella dedications do fit into a wider picture of women's engagement with literacy and education in Italy, which stretches back to the earliest stages of alphabetic writing.