I INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, geophysical survey and extensive excavation have revealed that Gabii, an ancient centre of Latium Vetus, was laid out in a planned, quasi-orthogonal pattern.Footnote 1 In view of the gradual and organic nature of the original growth of Gabii as a primary nucleated settlement out of the hut clusters or ‘leopard spots’ of the early Iron Age (during its urbanisation from the ninth to the sixth century b.c.e.), the regular plan of the mature, early republican city is indicative of an important transformational moment in its history.Footnote 2 It represents a definite break from previous patterns of occupation, and constitutes an anomaly in the regional context: the earliest wave of urban formation in Iron Age central Italy, to which Gabii belonged, inevitably tended to produce irregular urban fabrics, like Rome itself, due to long-term settlement growth and continuity.Footnote 3 The settlement and intramural burial data gathered by the Gabii Project now allow a fuller picture to be sketched of the circumstances surrounding the creation of this extraordinary urban grid. There are clear indications that most of the fifth century was characterised by a hiatus of occupation at the site, before the creation of the new city plan at the end of the fifth century, which necessarily involved significant spatial — and probably also socio-political — discontinuities with the previous settlement.

In this paper, we first summarise the archaeological evidence for the creation and dating of the quasi-orthogonal layout, and then consider the plan in a local and regional perspective. Based on this analysis, we suggest that the late fifth-century reorganisation of the city represents a moment of refoundation after a period of abandonment, and that the vicissitudes in the urban trajectory of Gabii are to be understood in connection with specific local events. Re-examining the relatively rich literary record dealing with the city and its relationship with Rome in the archaic and early republican periods, we offer a reassessment of the history of Gabii in the fifth century that focuses on two pivotal processes: at one end, the ritual devotio of the city by the Romans, an obscure event attested in antiquarian texts that has long been an interpretive crux in scholarship; and, at the other, the dynamics of early colonisation in Latium and the involvement of patrician clans and ‘warlords’ — specifically, in the case of Gabii, the gens Postumia. This new interpretation of the unfounding and refounding of Gabii not only has important implications for our understanding of the archaeology of the city and of early republican urbanism, it also sheds some interesting light on society, religion and interstate interactions during one of the ‘darkest’ ages in Roman history.Footnote 4

II THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

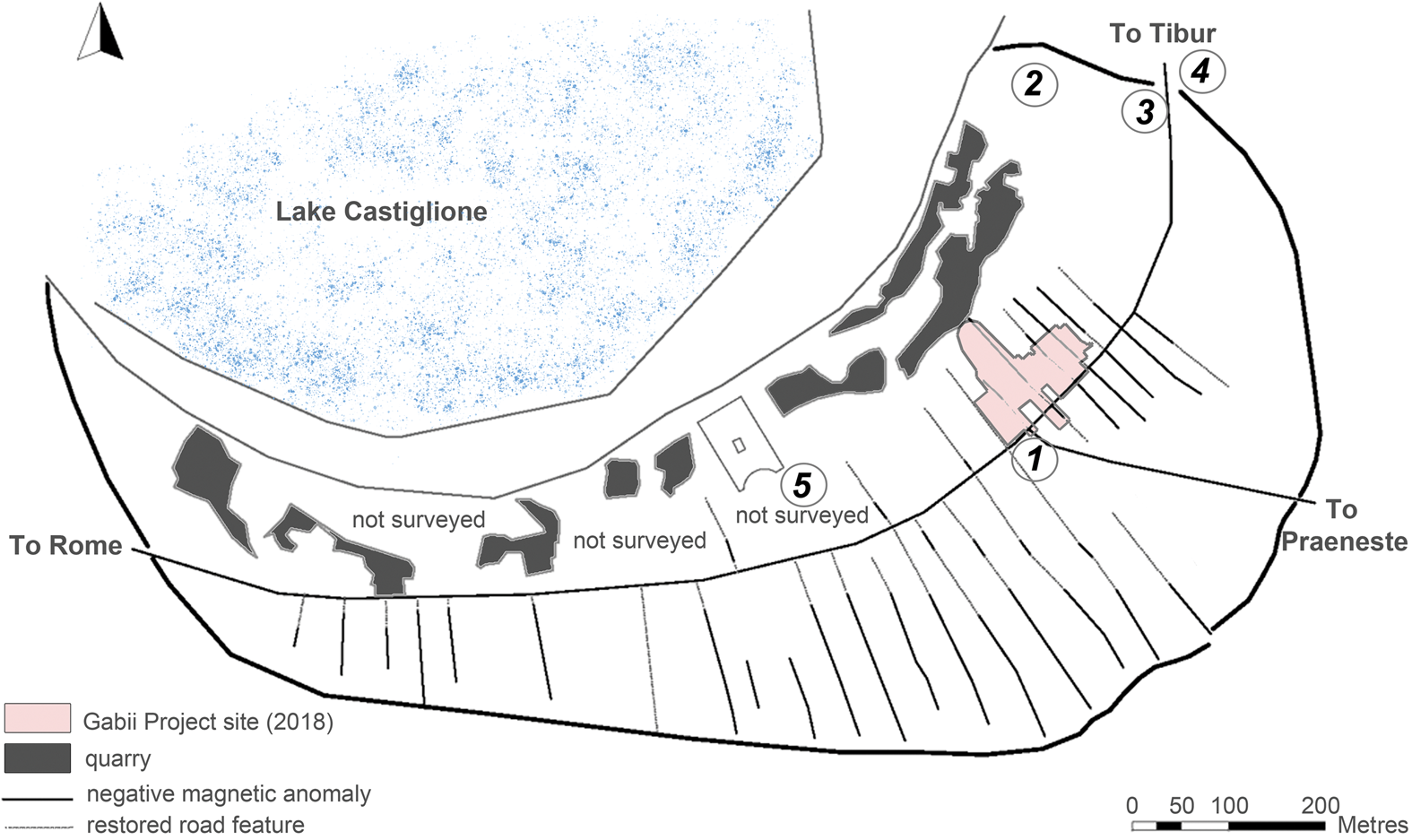

The urban plan of Gabii is centred on a main axial thoroughfare that bisects the area within the fortifications, adapting to the natural curvature of the south slope of the volcanic crater of Lake Castiglione. This trunk road corresponds to the intramural stretch of an old regional road coming from Rome, originally known as the Via Gabina, which approaches from the west the strategic narrow shelf of land bordered by the depression of Pantano Borghese to the south.Footnote 5 It then exited Gabii towards Corcolle and Tibur from a gate near the extra-urban ‘Santuario Orientale’ (Fig. 1). A 100 metre-long section was exposed by the state archaeological service (SSABAP Roma) in the 1990s in the so-called ‘Area Urbana’, south and west of the Gabii Project site, but its continuation to the north-east went unnoticed.Footnote 6 A series of roughly perpendicular roads branch off the thoroughfare at regular intervals, delimiting elongated city blocks that hug the truncated cone of the crater.Footnote 7 The only notable exception in the grid pattern is an east–west basalt paved road that departs at an odd angle from the Via Gabina in the direction of Praeneste (Via Praenestina), perhaps resulting from a later reorganisation of the regional road network.Footnote 8

FIG. 1. Restored city plan of Gabii, based on the interpretation of the magnetometer survey and corroborated by excavation. 1. Central intersection of roads from Tibur, Praeneste and Rome; 2. The arx and the so-called regia; 3. North-east gate in the fortifications; 4. ‘Santuario Orientale’; 5. Area of the Temple of ‘Juno’. (Drawing: M. Mogetta)

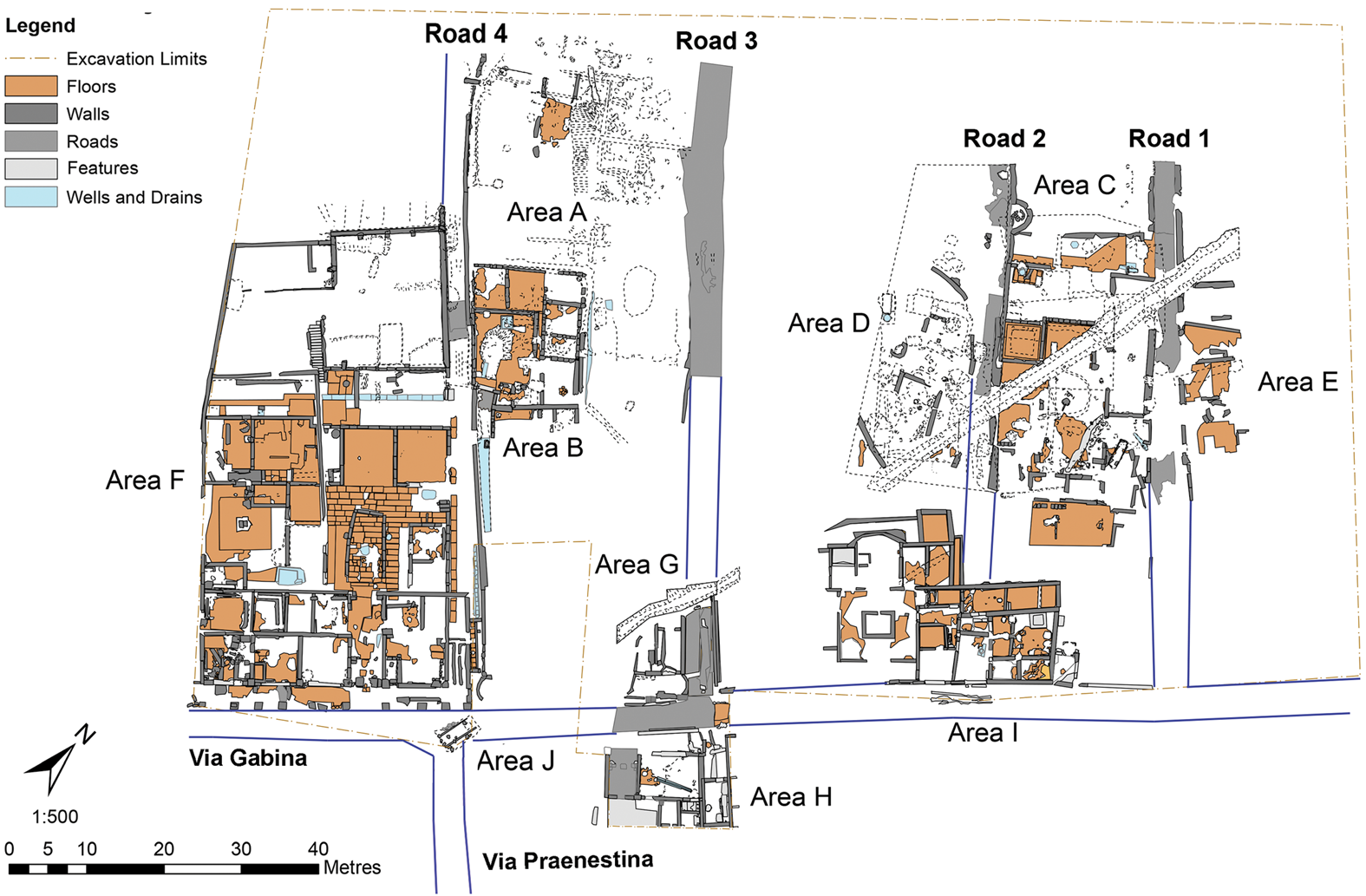

In explicating the process through which this new urban form came into being at Gabii, it is a logical preliminary hypothesis that, given its all-embracing and relatively uniform aspect, the quasi-orthogonal layout would have been planned formally as a unified whole, and that consequently its constituent roads would have been built simultaneously as part of a coordinated and centralised effort within the community. Accordingly, the dating of the initial construction of any given road ought to furnish a reliable chronology for the laying out of the entire urban network. Excavations within five contiguous city blocks near the intersection of the Via Gabina and Via Praenestina have yielded data from the broadly comparable stratigraphic sequences of the thoroughfare and four of the side streets running north from it (Roads 1–4), which allow a relatively precise date for the creation of the grid plan in the last quarter of the fifth century to be established (Fig. 2). We limit the discussion of the evidence here to only the original construction phase, proceeding road by road.Footnote 9

FIG. 2. Plan of the Gabii Project excavations, 2009–2018, showing the principal areas and roads under discussion. (After Mogetta et al. Reference Mogetta, Johnston, Naglak and D'Acri2019: fig. 2)

The earliest phase of the thoroughfare is represented by a negative feature cut into the natural bedrock. This basic road-construction technique is widespread and well attested throughout central Italy in the archaic period, and is generally referred to as a tagliata.Footnote 10 Subsequently, in the late fourth century, this relatively primitive phase was replaced by a succession of two roads consisting of thick preparation layers of gravel, crushed ceramic and earth (glarea) topped by a compact surface (via glareata); this glareate road in turn went out of use by the mid third century, when a basalt paved roadway was laid down.

Of the four side-streets that have been investigated, the excavated sequence of the easternmost (Road 1) is the best preserved. The first phase, again consisting of a tagliata (Road 11), was cut into the natural bedrock; this cut truncated a layer that contains no ceramic material dated later than the sixth century, which affords a rough terminus post quem (Fig. 3). At the other side of the chronological window, the tagliata roadway went out of use by the second half of the fourth century, when it was completely resurfaced with a thick layer of glarea (Fig. 4). Therefore, a date for the cutting of this tagliata at some point in the second half of the fifth century fits well with the stratigraphic evidence.

FIG. 3. View of the original cut into the bedrock to accommodate the first roadway (tagliata) of Road 11. (Photograph: Gabii Project)

FIG. 4. View of the subsequent mid-republican roadway of Road 13, with the transition between basalt pavement and gravel (via glareata) north of the Area C house. (Photograph: Gabii Project)

Although it is substantially less well preserved, Road 2 relates more clearly in its original construction to dramatic discontinuities with previous archaic features in the area, illuminating some of the complex dynamics bound up with the reorganisation of the urban fabric. Prior to the implantation of the grid plan, this sector of the city was occupied by a large domestic complex (known as the Area D compound), bounded by a stone precinct wall. A habitation sequence has been documented stretching from wattle-and-daub huts of the middle of the eighth century down to houses with stone foundations of the sixth century. Several rich infant burials testify to the elite status of the resident kin group.Footnote 11 Associated with the abandonment of this ancient compound in the last quarter of the sixth century are a number of exceptional late archaic tombs containing adult inhumation burials, generally without grave goods but dated on the basis of the stratigraphic sequence and typology to the first half of the fifth century.Footnote 12 When the new quasi-orthogonal plan, which does not respect the alignment of the earlier archaic structures, was created, Road 2 overlaid one of these tombs, which had been situated just outside the eastern wall of the northern room of the abandoned domestic structure (Fig. 5; Fig. 6).Footnote 13 About ten metres downhill (southeast) from this tomb, the roadway traversed another late archaic tomb, containing an infant burial with an assemblage of grave goods dating between the end of the sixth and the second quarter of the fifth century.Footnote 14 These inhumations provide a reasonably secure terminus post quem for the original phase of the plan.

FIG. 5. Composite plan of Road 2 showing the relationship of road features to the archaic occupation of Area D. (After Mogetta et al. Reference Mogetta, Johnston, Naglak and D'Acri2019: fig. 12)

FIG. 6. View of the partially excavated fill of the late archaic Tomb 41/42, subsequently traversed by Road 2 and covered by the western retaining wall of the road. (Photograph: Gabii Project)

The construction technique of Road 2 differs somewhat from the other side-streets. While there is a very shallow construction cut in the bedrock along the exposed length of the road, it is probable that this bedrock surface never served as a roadway. Instead, the original phase of the road (Road 21) must have been a via glareata laid down on the regularised bedrock, bordered on its western limit for part of its extent — where it ran alongside the ruins of the Area D compound — by a retaining wall built of irregular, unmortared stones. Along the eastern limit, the glareate road surface abutted a retaining wall built in a similar technique. On the basis of ceramic evidence, this construction activity can be dated to the end of the fifth century, which accords well with the terminus post quem established by the late archaic tombs.Footnote 15

The other side of the Area D city block is defined by Road 3. The first phase of this side street (Road 31) consisted of a tagliata cut into the natural bedrock, of comparable dimensions to Road 11.Footnote 16 By the middle of the third century at the very latest, a via glareata had been laid down within the old tagliata to elevate the level of the roadway (Road 32). The original construction of Road 3 appears to be connected with other major modifications made to the bedrock in the inhabited area immediately to the west (Area A). Previously, in the archaic phase, this space had been occupied by multiple hut structures that, based on the wealthy assemblages of grave goods found in the associated infant burials, belonged to elite kinship groups.Footnote 17 The obliteration of the occupation levels that must have preceded the creation of the city block bounded by Road 3 has been independently dated to not later than the fifth century.Footnote 18 The reoccupation of the area following the creation of the new layout consists of extensive levelling work, together with the repurposing of drainage channels and other cuts into the bedrock, which were made to respect the alignment of the orthogonal grid. These scanty features are tentatively interpreted as belonging to a mid-republican domus.Footnote 19 With sporadic exceptions like the previous site of the archaic compound in Area D that was left vacant, this period of urban development gradually filled in the city blocks and resulted, by the middle of the third century, in a considerably more continuous pattern of occupation across the site than had existed in the late archaic phase.Footnote 20

Separating this city block from Area F to the west, Road 4 intersects the Via Gabina at a central location within the general topography of Gabii, just north of the main junction with the Via Praenestina. The monumentalisation projects that transformed the important public areas to which it was adjacent — especially the multi-terraced building occupying the Area F city block — obscure most of the evidence for its first phases.Footnote 21 A compact glareate surface (Road 41) has been found to abut the eastern retaining wall of the upper terrace of the Area F complex; this roadway must have been created as part of the same building project, dating to the mid third century. There are traces of an earlier phase of the via glareata associated with the original doorway that opened into the courtyard of the ‘Tincu House’ immediately to the east, whose construction predates that of the Area F building by a generation or so.Footnote 22 The notable drop in the elevation of the underlying bedrock across the width of the roadway makes the existence of a pre-third-century tagliata below the visible glareate surfaces (which would correspond to the original phases of the other three side streets) almost certain.

In short, the cumulative evidence from these five city blocks and the first construction phase of their constituent roads provides a secure date for the establishment of the grid plan. It was laid out after a hiatus in the occupation of the city lasting several decades, as part of a unified undertaking in the last quarter of the fifth century, with successive phases of improvement throughout the mid-republican period.

III THE CREATION OF THE GRID PLAN IN ITS LOCAL AND REGIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT

Having established the layout and dating of the original phase of the intramural road network at Gabii, let us examine the archaeological background against which the city plan was created. Such a sweeping spatial reorganisation of the settlement, which must inevitably have had a comprehensive impact on land division and property allotment, could only have been the work of a strong political authority. Since this process involved profound discontinuities not only in the physical, but potentially also in the social fabric of the city, it is likely to have corresponded to a period of broader transition for the community. The transitional moment seemingly attested by the emergence of town planning may be connected with the nearly contemporaneous appearance of monumental public writing, evidenced by fragments of multiple inscriptions on stone dated to the second half of the fifth century. This momentary burst in epigraphic culture at Gabii has been interpreted as ‘a response to or mediation of significant social or political change’, which must have been closely bound up with ongoing processes of state formation.Footnote 23 But how did these new conditions arise? To answer this question, we review the evidence from excavations carried out at multiple locations within the settlement, which allows us to contextualise the creation of the grid in relation to the overall sequence of occupation. We then zoom out to a broader scale of analysis, in order to discuss the extent to which the case of Gabii is exceptional, or part of identifiable regional patterns of town planning, abandonment or major moments of rupture characterising the period.

As previously noted, the abandonment sequence of the Area D compound reflects major changes occurring during the fifth century. One of the early clusters of habitation in Gabii, belonging to an elite group whose roots reached back at least into the eighth century, the site was intentionally razed to the ground at the end of the sixth century, never to be reoccupied again. The stone building was replaced by a small group of rock-cut adult tombs, which may have been used by members of the previous residential unit, at least judging by the care with which the ruins were respected. The labour-intensive character of the graves speaks to the high social status of the individuals buried there. While the existence of a possibly contemporary infant tomb nearby could imply some continuity of habitation in the area, preliminary data indicates that in neighbouring Area C to the east (whose early occupation gravitated around the Area D nucleus) there is virtually no evidence for the fifth century. Rare Attic Red Figure pottery fragments spanning the fifth century come from secondary deposits in Area A, Area C and Area D, and suggest some form of elite activity (possibly funerary, though the lack of context does not allow firmer conclusions).Footnote 24 Thus, the fact remains that one of the main foci of interaction that had been embedded spatially in the landscape for centuries was abruptly abandoned, suggesting that some or all of its resident community had relocated elsewhere. This might not have been a unique case within Gabii, since another group of late archaic adult burials of a strikingly similar typology has been brought to light by the SSABAP Roma in the area between the Temple of ‘Juno’ and the so-called ‘Hamilton's Forum’, south-west of the Gabii Project excavations, although we have limited information regarding its possible relationship with earlier domestic structures.Footnote 25

Significantly, the Area D tomb cluster was put out of use just prior to the establishment of the grid, which completely obliterated any trace — and perhaps even any memory — of it.Footnote 26 The break with the previous pattern is evident also in the orientation of the new street system, which diverges from the main alignments of the archaic buildings that occupied the area. A similar situation has been documented in Area A, where early elite presence is signalled by rich Orientalising infant burials, and nearby in Area B. The fifth-century levelling of the archaic features there marks the final abandonment of yet another early habitation cluster. As a result of the process, the redevelopment of urban land in this sector of the settlement seems to bear no relationship with the pre-existing architecture.

This period witnessed discontinuities not only in elite domestic occupation, but also in the organisation of early public spaces, whose excavated levels suggest a significant shift from the archaic past (Fig. 1). On the so-called arx above the areas of the city on which our discussion has focused, a tripartite stone-built structure comparable in its architecture and decoration to the regia in the Roman forum — and thus interpreted as a seat of power — was emptied of its contents, partially razed and buried under a massive mound. The excavators date this intentional demolition activity to around the end of the sixth century.Footnote 27 The large-scale agger and fossa fortifications of the city, whose first monumental phase dates to the late seventh or early sixth century, was repaired in the late sixth or early fifth century. Another reconstruction followed in late fifth and fourth centuries, when the existing north-east gate connected with the Via Gabina was built (or rebuilt?), and a new exterior curtain in opus quadratum was added on the northern stretch.Footnote 28 Incidentally, this renovation independently confirms our dating of the layout, since the reconfiguration of the main gates of the pre-existing fortification circuit was dictated by the insertion of the street system. At the extraurban ‘Santuario Orientale’, a cult site established in the late eighth century, the first stone structure was destroyed by a fire in the first decade of the fifth century, and rebuilt on a completely different plan. The reconfiguration of the sanctuary, however, was almost immediately followed by a gap in ritual activity. Prestige offerings (including terracotta decorations) pick up again only at the beginning of the fourth century.Footnote 29 Finally, the same trend has been detected in the sacred area later occupied by the Temple of ‘Juno’, where there is a sharp decline from the end of the sixth century until the second half of the fourth; very little fifth-century material has been retrieved.Footnote 30 Taken together, these results provide substantial evidence of sudden contraction and abandonment occurring across the entire site with the transition from the late archaic to the early republican period. The occupation sequence at Gabii only shows signs of recovery in the early fourth century.

Taking the wider archaeological picture into consideration, the pattern observed at Gabii reveals certain unique features. At contemporary sites in the region, the archaeological record for the later fifth century is also generally poorly visible. A dearth of temple foundations from the 480s onwards has been noted for Rome.Footnote 31 Traditionally, the phenomenon of reduced building activity in both sacred and civic architecture has been interpreted as a sign of economic decline and social crisis during the early Republic, further exacerbated by warfare.Footnote 32 As alternative explanations, scholars have looked to the effects of deliberate policies of austerity, or to the fact that buildings of the regal period could still fulfil the necessary administrative functions.Footnote 33 More recently, however, it has been suggested that monumental construction projects begun at the end of the regal period continued well into the middle of the fifth century without any significant break.Footnote 34 A similar development has been proposed for Ardea, another top-tier urban centre of Latium, where the record for the main temples demonstrates public building efforts lasting throughout the first half of the fifth century, and perhaps even later.Footnote 35 In this context, the case of Gabii stands out for the relative sequence and spatial relationship between the obliteration of the archaic occupation, the appearance of clusters of intramural adult burials, the complete lack of building activities for most of the fifth century and the eventual establishment of the grid toward the end of this period.

There are few well documented cases of town-planning projects at major cities in central Italy with which to compare the Gabine evidence. At Tarquinia, a geophysical survey conducted on the western sector of the Civita has recorded a regular layout of parallel roads delimiting standardised orthogonal city blocks. Evidence from excavation suggests that this subdivision was part of a generalised reorganisation of the urban area carried out in the late sixth or early fifth century.Footnote 36 This is followed by a period of decline, which is mirrored by a drop in funerary evidence from the main cemetery areas in the later fifth century. The case of Pompeii in the fifth and early fourth century may provide another example of the same trend. Although the extent of the street network outside the major thoroughfares (Via del Vesuvio/Via Stabiana, another on alignment with Via di Mercurio, and Via Consolare; and the axis of Via Marina and Via dell'Abbondanza) is more elusive, and the subject of some speculation, the idea that the archaic settlement had a fully developed urban form is now commonly accepted.Footnote 37 The so-called Altstadt is now generally understood as resulting from the shrinking of the Samnite occupation within the confined area around the forum. In other words, at both Tarquinia and Pompeii the archaeological data for the contraction of the settlement clearly postdates the first consolidation of the urban grid, whereas the reverse process occurred at Gabii, with the establishment of the layout following a period of crisis.

The presence of funerary areas within the former boundaries of a once flourishing archaic town is rarely attested in the region of Gabii. An intriguing case is that of Satricum, where several nuclei of adult graves have been identified. A small necropolis is located along the so-called Via Sacra at the south-west corner of the temple on the acropolis, while a more extensive burial ground was found in the lower settlement at Macchia Santa Lucia. Noting the lack of contemporary domestic remains, the excavators combined the funerary evidence with the existence of a votive deposit near the temple containing materials ranging from the fifth to the second centuries. On this basis, they interpreted the pattern as a sign of the radical transformation from flourishing urban settlement into a mere pilgrimage site centred on the sanctuary, as a consequence of its alleged destruction by the Volscians in 488.Footnote 38 Only a small community of Latins would have remained at the site, burying their dead within what was no longer a city and thus free from religious or ideological constraints.Footnote 39 Subsequent discoveries on the acropolis and elsewhere in the settlement where erosion was less of a factor seemed to provide evidence for continued habitation of the site in the post-archaic period, undermining the previous reconstruction: the fifth-century site would have featured funerary areas in close proximity to domestic quarters, but would have been separated from them by the main roads.Footnote 40 The change in the pattern of use was attributed to Volscian occupation, which would explain the adoption of funerary practices at odds with the Latin tradition.Footnote 41 However, the latest finds from the lower town now include fifth- and fourth-century graves that are dug on top of the main road, showing that by the middle of the fifth century, or shortly after, large sectors of the archaic settlement and town plan had been turned into a burial ground. Because the lower course of the Via Sacra was no longer functioning, the excavators tentatively place the new Volscian settlement south of the site of the archaic town.Footnote 42

Similarly, the fifth-century inhumations at Gabii are indicative of a breakdown not only in the previous social and spatial order of the city, but in the symbolic order as well. The overall extent of the extraurban burial grounds that were in use during the archaic period is uncertain, but the available evidence suggests that clusters of adult tombs had developed during the period of city formation on three sides of the area later defined by the fortifications.Footnote 43 Burials of adults within the walls — and thus within the fixed sacred boundary — would have been unthinkable. Such an act violated an ancient and enduring taboo in Latin culture.Footnote 44 As in the case of Satricum, the impression is that this sacred boundary was no longer maintained and that, accordingly, as a properly defined urbs, Gabii had ceased to exist.

IV REASSESSING THE HISTORY OF GABII IN THE FIFTH CENTURY

In this light, the momentous change at the end of the fifth century represented by the new urban plan of Gabii appears tantamount to a refoundation of the city. Although in general terms the fifth-century decline at Gabii would seem to fit squarely within a broader archaeological phenomenon in contemporary central Italy, the actual settlement dynamics of growth, abandonment and repopulation revealed by detailed study of our dataset appear quite anomalous. To explain this exceptional sequence, in this section we critically revisit the textual evidence for Gabii in this period, with the aim of moving beyond overarching interpretive frameworks to a more specific attempt to situate and understand the developments that can be observed on the ground in their historical context. In order to reconstruct the history of late archaic and early republican Gabii, it is necessary to take into account two crucial events, and to consider the impact that these had not only on Gabii's relationship with Rome, but also concomitantly on its internal civic and urban configuration: the foedus Gabinum, a singularly important early treaty that granted Roman citizenship wholesale to the Gabine community; and the Roman devotio of the city of Gabii, an archaic dedicatory ritual in which an enemy community in its entirety was cursed and declared forfeit to the gods. At first glance, the antithetical nature of these interactions appears difficult to reconcile, and a coherent narrative that makes sense of them in relation to one another and to the broader dynamics within contemporary central Italy has remained elusive.Footnote 45 But the new evidence for the sweeping reorganisation of the city toward the end of the fifth century calls for a reappraisal of these events. Specifically, we suggest that the obscure devotio of Gabii, which has hitherto resisted secure dating or contextualisation, is to be placed at the beginning of fifth century, not long after the foedus Gabinum; and that the discontinuities of occupation across this period at Gabii that are prerequisite to the creation of the new urban plan might be interpreted as part of the catastrophic consequences of this ritualised unfounding of the city by the Romans.

Since the discussion of the devotio that follows will argue that such a ritual is to be understood in light of the establishment of the foedus Gabinum, it will be useful first to examine the treaty, its circumstances and its effects. Our evidence for the foedus comes entirely from a narrow span of time in the Augustan age, almost five centuries after the two rival city-states first concluded its terms. The antiquarian intellectual climate, augmented by the cultural and political programme of the princeps, promoted a renewed interest in the kinds of historical documents of which the archaic treaty between the Romans and the Gabines was a prime example. In his epistle to Augustus, written around 12 b.c.e., the poet Horace refers sardonically to the supposedly widespread contemporary attitude among the Romans that extolled ‘the treaty of the kings made on equal terms with the Gabines’ (foedera regum uel Gabiis… aequata) as one of the earliest ‘literary’ productions of the Romans, dictated by the Muses themselves atop the Alban Mount (Albano Musas in monte locutas).Footnote 46 Around the same time as the publication of the second book of Horace's Epistulae, C. Antistius Reginus, a moneyer from a gens that traced its origins to Gabii (and had woven its family traditions into the legendary history of early Roman–Gabine interactions) minted a coin commemorating the ancient foedus. The reverse of this aureus depicts two men — one clearly wearing the toga draped in the particular ritual fashion of the cinctus Gabinus — conducting a sacrifice upon an altar, together with a legend celebrating ‘the treaty of the Roman people with the Gabines’ (foedus populi Romani qum Gabinis).Footnote 47 Although the foedus Gabinum seems to have been very much ‘in the air’, the contemporary Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus is the only extant author to provide any details of its content and context. He claims that the terms were set down in writing upon a wooden shield covered in the hide of the ox that was sacrificed as part of the oath-taking ceremony when the treaty was ratified. Furthermore, he attests that this inscription, ‘written in ancient characters’ (γράμμασιν ἀρχαϊκοῖς ἐπιγεγραμμένη), remained displayed in the Augustan age as a ‘monument’ (μνημεῖον) within the temple of Semo Sancus.Footnote 48 With good reason, most scholars have accepted the autopsy of the historian, and the authenticity of the document.Footnote 49

It is possible to infer at least the general purview of the foedus from the somewhat oblique narrative of Dionysius. Its terms included guarantees to the Gabines of their autonomy (τήν τε πόλιν αὐτοῖς … τὴν ἰδίαν ἀποδιδόναι), continued possession of their territory (τὰς οὐσίας, ἃς ἔχουσι, συγχωρεῖν) and, most significantly, the rights of full citizenship at Rome (σὺν τούτοις τὴν Ῥωμαίων ἰσοπολιτείαν ἅπασι χαρίζεσθαι).Footnote 50 This remarkable ἰσοπολιτεία clause, which is consistent with Horace's characterisation of the treaty as a foedus aequum, is fundamentally important for the history of the expansion of the Roman citizenship.Footnote 51 Related to the incorporation of Gabii into the Roman political sphere, there seems to have been an additional, religious dimension. According to the lore of the augures publici, only in the territory of Gabii (ager Gabinus) could the same rituals be observed as in the territory of Rome (ager Romanus).Footnote 52 While our accounts do not explicitly trace the origins of these auspicia singularia back to the terms of the treaty, the establishment of uniquely close civic ties between the two communities is the most likely context in which such a provision that exceptionally privileges another Latin community in the public religion of the Roman state would have entered Roman augural practice. Thus, ἰσοπολιτεία and auspicia singularia were probably complementary and interrelated aspects of the foedus Gabinum.Footnote 53

As for the date and occasion of the foedus, the narrative of Dionysius weaves its enactment into the immediate aftermath (c. 510) of the infamous Roman capture of Gabii through the duplicitous stratagem of the trickster tyrant Tarquinius ‘Superbus’ and his son Sextus. But considerable circumspection is required, since much of the Tarquin episode smacks of later literary embellishments and fabrications within the Roman historiographical tradition.Footnote 54 Consequently, it is of limited explanatory value for understanding the genesis of the treaty. But, divorced from the particulars of the myths of the annalists upon which Dionysius drew, an approximate date around the end of the sixth or beginning of the fifth century can serve as a reasonable point of departure for attempting to determine the general historical setting of the foedus.Footnote 55 The basic concerns that the foedus aequum attempts to address, to the extent that they can be reconstructed, would seem to presuppose the existence of intercommunity conflict, or at least of underlying conditions generative of conflict, in which neither party was able to gain decisive advantage. Indeed, the terms of the treaty, which are remarkably advantageous for the Gabines, are inconsistent with an outright Roman capture of the city, whether by fraud or by force. Moreover, fragments of folk aetiologies preserved in the writings of Roman antiquarians lend further credence to what would be the natural assumption based on the realities of geographical proximity and the process of state formation: that there had been a longstanding rivalry between Rome and Gabii stretching back well into the archaic period and punctuated by intermittent violence, probably in the form of relatively small-scale raiding parties.Footnote 56 These considerations, combined with the scant evidence for the use of monumental public writing in archaic Rome, render it highly unlikely that the treaty dates before the middle of the sixth century at the very earliest; we may use this as a conservative terminus post quem. On the other side of the temporal window, the terms of the foedus Gabinum — especially the grant of ἰσοπολιτεία — are most intelligible at a point in time prior to the foedus Cassianum, the compact concluded between the Romans and the Latins following the Latin War, which resulted in the creation of the new Latin League with Rome at its head.Footnote 57 After this point, while bilateral treaties between Rome and the Latins did not become obsolete as an instrument of diplomacy, their use seems to have been reserved for the readmission of rebellious Latins into alliance with Rome, and their terms limited to the renewal of the societas and amicitia guaranteed under the foedus Cassianum.Footnote 58 So the foedus Gabinum can, in sum, be reasonably placed around or shortly before 500. Gabii, for a brief period of time before the Latin War, enjoyed an unparalleled status. Its good fortune was not to last.Footnote 59

From the foedus, let us turn now to the devotio. The sole textual evidence for the devotio of Gabii comes from an obscure but intriguing reference in the Saturnalia, a learned miscellany of Roman antiquarian lore written in the fifth century c.e. by the senator and high-ranking imperial office-holder Macrobius (Praetorian Prefect of Italy in 430). Following a discussion of old Roman customs relating to the besieging of cities and arcane beliefs in the importance of their tutelary divinities, Macrobius records the prayer formula by which dictatores and imperatores might, after calling forth the gods of the place through the related ceremony of evocatio, devote a city of the enemy to the proper chthonic deities. The commander would beseech these gods, as he performed the various elements of the ritual, to ‘take the city, its fields, the lives of its citizens and their lifetimes as cursed and doomed to destruction’ (uti uos eas urbes agrosque capita aetatesque eorum deuotas consecratasque habeatis).Footnote 60 In the course of his researches, Macrobius had found in early annalistic writers (prisci annales) that four central Italian cities had suffered this archaic ritual of devotio at the hands of the Romans: Fidenae, Veii, Fregellae and Gabii.Footnote 61 The author does not elaborate further on these events. Of these four cases, the devotio of Veii, around the beginning of the fourth century, is the best understood, both historically and archaeologically;Footnote 62 while the devotiones of Fidenae and Fregellae are otherwise unattested, the occasion of each can be reasonably conjectured.Footnote 63 For Gabii, the historical circumstances are more obscure.Footnote 64 Apart from the story of the duplicitous infiltration and takeover of the city by the Tarquins, an episode that is at least partly an annalistic invention, our extant texts preserve no memory of a Roman conquest of Gabii. In the period of Roman political transition around the end of the sixth century, it is possible that factional strife within the community of Gabii was a contributing factor in confrontations with newly emergent powers in Rome. Based on the material cultural evidence, at least some Gabine groups seem to have had close affiliations with the older monarchic authority, and in these changing circumstances, questions may have arisen about the validity — or utility — of the foedus.Footnote 65 The last recorded conflict between Rome and Gabii dates to the beginning of the fifth century, during the Latin War, in which the Gabines sided with the Latin states that had reconfigured and reoriented their alliances to exclude the former hegemon; after this event, Gabii temporarily fades from history, only to re-emerge onto the local stage over a century later as an ally of Rome in the war against the recalcitrant Latin city-state of Praeneste in the late 380s.Footnote 66 It must have been at this crucial moment, in the wake of the decisive victory of the Romans under the dictator A. Postumius at Lake Regillus, when the devotio of Gabii took place.Footnote 67 The battle was fought in the vicinity of Gabii, on the border of its territory.Footnote 68 It would thus be the first known instance of the ritual, a dubious distinction accorded to a city that, in many other respects, occupies such an exceptional place in the early history of Rome.

It is clear that the idea of the devotio, which entailed — certainly in theory and apparently in practice — the utter destruction of the city, is incompatible with the foedus Gabinum, the terms of which assume the continuance of Gabii as a political community in its own right. There is no tenable interpretation of the foedus as the final outcome of the same conflict that involved the devotio of the city. Therefore, the logical conclusion is that the devotio could only have happened at a point in time after the establishment of the treaty. Furthermore, it stands to reason that it was, in reality, the existence of the unique treaty between Rome and Gabii that made the disloyalty of the Gabines and their alliance with the rest of the Latin states against the Romans in the Latin War all the more bitter, and the extreme — and possibly innovative — punitive measure of the devotio all the more warranted. Indeed, the subsequent history of the Roman devotio suggests that it came to be reserved for only the most intractable cities, those enemies who might be adjudged to have incurred the wrath of the gods by the breaking of oaths and the violation of treaties: this is true of the other early republican cases of Fidenae (c. 426) and Veii (c. 396), as well as the later ‘archaising’ revivals of the ritual at Carthage (146), Corinth (146) and Fregellae (125). It seems that the extraordinary vengeance of Rome against Gabii was commensurate with the extraordinary rights and privileges that the city had previously been granted, and had faithlessly spurned.Footnote 69 Gabii was, moreover, a powerful and longstanding rival, which seems on some level to have supported the ousted political faction at Rome (leaving aside the vexed question of how exactly the events surrounding the end of the regal period are to be understood). Combined with its geographical proximity to the battlefield, it stood out as a logical target for this exemplary act of sacral retribution. Memories of the precipitous downfall of Gabii persisted: the frequent collocation of the three original early republican oppida devota — Gabii, Fidenae and Veii — in later writings as bywords for ruination and the catastrophe of a once great city is further suggestive of the lasting exemplum of the devotio that attached to their names and histories, even if the vague mentions in the extant accounts do not specifically identify their shared calamity as such.Footnote 70 This widespread, almost commonplace identification of Gabii with an archaic ruin in late republican and early imperial literature is particularly interesting since, in light of the extensive archaeological evidence from both public and private contexts for an impressive mid-republican resurgence, it is such a patent anachronism, which ignores all urban development subsequent to the ancient devastation. Such rhetorical uses of Gabii seem to reflect the degree to which the idea of the city was so inextricably intertwined with the memory of its devotio that no centralised urban planning of the fourth century, no monumental scenic architecture of the third century, no grand Hellenistic-style temple-theatre complex of the second century, could displace its deep-rooted identity as an oppidum devotum in the collective Roman imagination.Footnote 71

On this view, it is tempting to see in the belated dedication of the existing sanctuary of Semo Sancus on the Quirinal that housed the foedus Gabinum by Sp. Postumius in the next generation (c. 466) a link, as a kind of epilogue, to the story of the momentous ritual destruction of Gabii. As a monument, the shield inscribed with the treaty would inevitably have been viewed differently in the aftermath of the devotio, especially displayed as it was in a shrine to a divinity whose original sphere of responsibility seems to have comprised oaths and other compacts considered to be sacred and unalterably fixed.Footnote 72 It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the political actor interested in (re)shaping the complex meanings, memories and symbolic importance of this space was a member of the patrician gens Postumia, the clan to which the dictator belonged whom the historical tradition unanimously credits with the victory over the Latins at Lake Regillus — and who accordingly, if our interpretation of the occasion of the devotio of Gabii is correct, would have been responsible for the performance of the ritual. This familial connection may have been one of the principal motivations behind the formal consecration, after a long lapse of time, of the shrine of Semo Sancus, a central feature of which was a document that now stood as a memorial both to the self-inflicted reversal of fortune of an ally turned treacherous and to the achievement of the gens Postumia in exacting a kind of divine retribution.Footnote 73 Such an instrumental use of a temple (re)dedication to glorify the gens and consolidate its place within the shifting political landscape at Rome aligns with the other, more prominent religious building activities of the early fifth-century Postumii, while the interest in the ambivalent monument surrounding the foedus Gabinum also fits well into the narrative of the lasting involvement of the Postumii in the city of Gabii and the ager Gabinus, down into the third century.Footnote 74

If it can be plausibly argued on the basis of historical evidence that the city of Gabii underwent an extensive intentional destruction and a ritual unfounding in the form of a devotio at some point in the early fifth century, then we gain valuable contextualisation for the intriguing urban trajectory of fifth-century Gabii plotted independently by the archaeological evidence: the roughly contemporaneous obliteration of important buildings on the arx and at the extramural sanctuary and the abandonment of the elite domestic compounds around the beginning of the fifth century; the apparent hiatus in occupation activity in the middle of the fifth century, marked by the significant anomaly of the intramural inhumation of adults; and, finally, and most importantly for our purposes here, the creation of a radically innovative urban plan towards the end of the fifth century. It is possible to weave together the archaeological and the historical threads into a coherent, if tentative, narrative. Around the end of the sixth century, Gabii concluded a remarkable foedus aequum with Rome, the terms of which granted its citizens and territory a privileged political and religious status; after backing the ousted political faction at Rome and treacherously shifting its alliance to the Latin League shortly thereafter, it became the first city to suffer as retribution a devotio when the Romans, under the dictator A. Postumius, prevailed in battle nearby at Lake Regillus; the defeat of Gabii came to factor importantly into the self-promotion of the gens Postumia.Footnote 75 The city was destroyed and ritually unmade, and consequently abandoned for much of the fifth century. Different Gabine factions enjoyed divergent fates: certain clans, like the gens Antistia, which rose to some prominence at Rome within only a few decades, seem to have negotiated the tumultuous political landscape more successfully than others.Footnote 76 Some locals — perhaps subjected to forced migration elsewhere — returned to bury their dead among the ruins of the unfounded city. Within the habitation clusters of the Iron Age and archaic community, intramural funerary display had always represented an important strategy for both the construction and performance of identity and the creation of symbolic ties with the physical landscape.Footnote 77 After the city was depopulated, the practice clearly continued, albeit in different forms, into the mid fifth century, probably in order to maintain or construct a link with the past occupants. The removal of the sacred boundary of the city and its associated taboo against intramural burial by the ritual of the devotio opened up the potential to exploit adult inhumations as markers of ancestral places, taking over the function that infant burials had previously served in materialising physical and symbolic ownership. Non-locals are unlikely to have been interested in burying their dead with such care and in such close spatial connection with the old seats of power. But, as a political community, Gabii had become defunct, a kind of ghost town.Footnote 78 When the mountain peoples of the Aequi and Volsci descended into the Latin plain in the mid fifth century, the marauders encountered no resistance whatsoever in the territory of Gabii.Footnote 79 In the last quarter of the fifth century, however, occupation activity in the city resumed with a sudden intensity: on the direction of some central authority, the grid-planned streets were laid out simultaneously, completely obliterating features that had persisted even in the abandoned city as meaningful places of memory in the landscape; multiple public inscriptions on stone were set up, which clearly indicate the presence of powerful social actors and an intended civic audience. Thereafter, the community gradually came back to life. In the 380s, the re-emergent city was a bulwark for Rome against the depredations of Praeneste, and by the middle of the third century, it was a thriving urban centre once more.

Moving forward in time, as has been suggested at various points throughout this discussion, the political rivalries, imperial conquests, cultural developments and intellectual trends of subsequent generations fostered continued interest in the early history of Gabii, which was of such fundamental importance to the story of Rome itself. The beginnings of Roman historiography in the second century defined more clearly traditions that had long been propagated by the self-interested family agendas of the Postumii and their aristocratic competitors like the Fabii, as intensifying anxieties about problems like kingship and tyranny in republican society more broadly also drew attentions — and imaginations — to particularly salient episodes in the Gabine past that spoke meaningfully to the Roman present. A renewed fascination with archaic religious procedures must have surrounded the revival of the obsolete ritual of the devotio in 146, and lent richer significance to the prototypical fate of early republican Gabii in the works of contemporary annalists. This formative period undoubtedly (re)shaped Roman memories about Gabii. But the re-elaboration or invention of the tradition seems to have integrated and built upon certain underlying events and dynamics for which there is a high degree of plausibility, especially in light of the archaeological record, with which it generally aligns. Finally, in the late Republic and the Augustan age, the concomitant rise of antiquarianism and decline of the cities of old Latium proved to be an especially evocative combination in the case of Gabii: commentary on the physical ruins, venerable documents and originary customs of its bygone greatness became part of a new discourse of Roman identity.

To conclude this historical reassessment, our proposed interpretation of the new, planned city of Gabii is that it represents a refoundation after the rupture of the mid fifth century caused by the devotio. Even if one is hesitant to accept the identification of the occasion of the abandonment with this specific historical event, the clear discontinuity of occupation nonetheless raises important questions of the agency and motivations behind the revival of Gabii. If the process that we discern is the Gabine community reconstituting itself multiple generations after the trauma of destruction, then this would be an exceptionally uncommon and complex case of local resilience and initiative. If, on the other hand, this was a project conceived of and implemented by agents of Rome as the hegemonic power in Latium, which seems the more likely scenario, there would be, given its early date, interesting and important implications for the history of colonisation and planned urbanism in Roman Italy.Footnote 80

V THE REORGANISATION OF GABII AND EARLY REPUBLICAN COLONISATION

The integrated analysis of the stratigraphy of the street system and the sequence of occupation at Gabii allows us to characterise the tempo and modalities of its urban reorganisation with greater precision than is normally possible for most towns of Latium, where very little survives besides fortifications and temples for the early republican period. While early fifth-century renovations are well attested at nearby peer sites (for example, the city walls at Praeneste;Footnote 81 the temples at Ardea, discussed aboveFootnote 82), the case of Gabii stands out because of the nature of the hiatus between contemporary monumental construction projects and the actual establishment of the grid, which we can now assign with confidence to the end of the fifth century. The intermediate phase consists of small clusters of adult burials developing around abandoned elite habitation foci, a pattern that elsewhere in the region is only attested at sites that were defunctionalised as a result of warfare, as at Satricum (where the practice continued on a larger scale well into the fourth century). The complete obliteration of these archaic features by the road grid, together with the simultaneous appearance of a robust public epigraphic culture, has prompted us to re-examine the historical relationship between Gabii's unparalleled urban upheaval and the dynamics of the absorption of the old city into the Roman political sphere.

Given that the newly planned city of the late fifth century looks like the result of a kind of refoundation, which may implicate the involvement of the Romans in some capacity, it is worth considering the resettlement of Gabii in the broader context of early republican colonisation. Despite the fact that the city is not recorded explicitly among the priscae Latinae coloniae found in the literary texts, ‘colonisation’ is a useful preliminary approximation for the general changes under way at Gabii in this period.Footnote 83 Given the high degree of variability and inconsistency in the dynamics, results and records for these colonies, it seems that an inclusive approach — which admits the utility of comparison between settlements that are explicitly called coloniae in the surviving texts and those that are not, but share similar trajectories — is justified. In recent scholarship on early colonisation, there are two basic models for conceptualising the process: ‘a “statist” scenario, which postulates radical interventions in the colonised areas, planned and organised by the Roman political body’, and a decentred interpretation that places emphasis instead on the independent initiative of gentes and ‘warlords’ acting with more or less autonomy from Rome.Footnote 84 For the fifth century, at least, the ‘gens/warlord’ model increasingly seems to make the most sense of the range of available archaeological, epigraphic and literary evidence.Footnote 85 Given the rather poor archaeological visibility of early colonisation, the city plan of Gabii represents a potentially important contribution. Moreover, the idiosyncratic aspects of the form of the plan may offer further support for the argument that Rome was not actively or directly involved in the centralised creation of a coherent colonial model in the fifth century, and that there was a significant degree of local experimentation.

The close relationship between the patrician gens Postumia and Gabii is therefore of particular interest in thinking about the possible agency behind the reorganisation and reoccupation of the city. In the first half of the fifth century, the activities of the Postumii around Gabii would plausibly fit the model of gentilician warlords, operating in the interstices between state and private power. The dictator A. Postumius defeated Gabii and, if our interpretation is correct, performed the ritual devotio of the conquered city. A generation later, Sp. Postumius took a personal interest in carefully curating the memory of the treaty between Rome and Gabii. At this period, the gens seems to have possessed extensive property in the neighbourhood of Gabii, which can be deduced in part from the fact that beginning in the early fifth century, several generations of the most distinguished branch of the Postumii — the Alb(in)i — took the secondary cognomen Regillensis.Footnote 86 Although the historical accounts explain this name as an honorific and attribute its origins to A. Postumius’ victory at Lake Regillus, this is almost certainly an anachronistic interpretation. Like the identical cognomen of the contemporary patrician Claudii Sabini Regillenses, whose ancestral home was the Sabine town of Regillum, the name of the Postumii Alb(in)i is far more likely to have been toponymically derived, and to refer to a seat of landed power in the area of the Latin plain around Lake Regillus.Footnote 87 At least some of these holdings — presumably lying to the north and east of Regillus, between the lake and the city — were carved out of the former territory of Gabii, which extended southward to the border with the ager Tusculanus near Regillus; but it cannot be ruled out that the origins of the Postumii also lay in this region, and that this pre-existing local interest may have been intertwined with the leading role that A. Postumius took in the battle.

Down into the late fourth and early third centuries, the Postumii dominated the ager Gabinus almost in the fashion of feudal lords, blurring — and at times overstepping — in their archaic-style exercise of authority the boundaries between magistrate and patron. In 291, the consul L. Postumius Megellus assembled 2,000 Roman soldiers near Gabii and employed them to clear private land on his large ancestral estate in the ager Gabinus, detaining them for a long time in the unhealthy marshes (that until modern times characterised much of the hinterland of Gabii) and thereby ultimately contributing to the outbreak of an epidemic within the army.Footnote 88 Such despotic behaviour, which brought the arrogant Postumius into vocal conflict with the rest of the aristocracy, doubtless represents the persistence of early republican forms of clientage and labour exploitation, and reflects Postumius’ increasingly outmoded conception of his own individual power. In his subsequent defence before the Senate, he claimed that he was its master, not the other way around. These remnants of the extreme local autonomy and social dominance of the patrician gens, which are reminiscent of the situation of the ‘warlords’ active in fifth-century Latium, were probably especially resistant to change among certain elite families (like the Postumii) and on certain kinds of ancestral gentilician land (like the ager Gabinus).Footnote 89 There is a tradition, perhaps containing a kernel of relevant information, that associates the powerful members of the gens Postumia in the fifth century with large bands of followers, who could at times be mobilised for offensive (perhaps even semi-private) warfare through invoking alternative forms of personal authority. Ascribed to these Postumii is a commitment to maintaining older modes of distributing conquered territory that privileged the aristocratic gentes rather than the new plebeian element in the Roman military system.Footnote 90 Despite their reactionary tendencies, members of the clan could be flexible enough shrewdly to adapt the sway they wielded locally to changing political realities. A generation before Megellus’ transgressive activities in the ager Gabinus, his kinsman Sp. Postumius Albinus as consul in 334 had proposed the foundation of the important Latin colony at Cales, a measure that was intended in part to forestall disaffection among the plebs and win political favour for its proponents.Footnote 91 Based on the apparent presence of families of Gabine extraction among those enrolled as settlers at Cales, Postumius seems to have used this new, more formalised type of colonial scheme in rather traditional ways to reward his own personal clientelae.Footnote 92 It is, therefore, not implausible to imagine a significant degree of continuity in the topography of power in the ager Gabinus — centred around the Postumii — from the early Republic to the age of the Samnite Wars, and to see the resettlement of Gabii at the end of the fifth century as a process grounded in, and a function of, this gentilician power.Footnote 93 In this gens-oriented model of colonisation, the Postumii would have possessed both the requisite local authority to coordinate the centralised effort implicated by the new urban layout, and the vested interest in the reallocation and redistribution of property that the comprehensive replanning of the city entailed.

Although family agendas like those of the Postumii were highly influential in shaping the processes of early Roman expansion and colonisation, it remains to consider the possible motivations on the part of the broader republican decision-making apparatus that might have contributed to more generalised support for the reoccupation of Gabii.Footnote 94 Amidst the conditions that prevailed in Latium around the time of its refoundation, Gabii's geographical location lent it significant strategic value as a defence against both the unsettled Aequi and wayward Latin allies to the east. The colonia planted in the last quarter of the fifth century at the rebellious city of Labici, in the near vicinity of Gabii to the southeast, certainly attests to Roman concern with securing their hold on the region more firmly. Together with Gabii, it served as an important buffer in the 380s against the expanding hegemony of Praeneste, which maintained its own rival network of subsidiary oppida in this area of the Latin plain. The new city of Gabii may thus have originated contemporaneously with the colonia at Labici as a cognate response, negotiated between the interests of the clan and the ‘state’, to the same social and military pressures.Footnote 95 After peace was finally established in Latium at the end of the fourth century, Gabii became an important node in the social and religious networks of distinguished members of the local elite of Praeneste, perhaps mediating to some extent their interactions with Rome.Footnote 96

From the perspectives of both archaeology and history, then, the planned resettlement of Gabii at the end of the fifth century constitutes a valuable and complex new case study for understanding early republican urbanism. In particular, the distinct possibility of the long-term involvement of the Postumii in the city and its territory affords a rare opportunity for venturing a more fine-grained analysis of the general dynamics articulated in current models of ‘warlord’- and gens-oriented colonisation in this period.

VI CONCLUSIONS

Having re-evaluated, on the basis of the latest archaeological data, the idea of the quasi-orthogonal layout of Gabii as an outcome of an essentially independent long-term development (as had been initially hypothesised in previous publications), we have proposed a new reconstruction of the history of the interstate interactions between Rome and Gabii in the course of the fifth century, and offered an interpretation of the possible impacts of Rome's early expansion on the local urban trajectory. The details of the processes at work — which we have connected to moments of ritual unfounding (devotio) and planned resettlement (‘colonisation’) — and the precise role of particular social and political actors — like the gens Postumia — in the end of the old urban form and emergence of the new are, at present, beyond our ability to establish with certainty.Footnote 97 Other relevant aspects of the archaeological record of early republican Gabii still need to be elucidated in order to reach firmer conclusions about the first phase of occupation of the planned settlement. The material evidence from across the five contiguous city blocks excavated thus far is extremely scarce throughout the first half of the fourth century, so much so that the general impression we have is that of a site which for some time resembled an empty, subdivided box. This might be taken to indicate that the initial impact of this kind of gentilic ‘colonisation’, as opposed to later state-sponsored foundations, was comparatively limited in demographic terms. Another problematic aspect concerns the emergence of monumental civic infrastructure, which at the moment seems to represent the last addition to Gabii's urban landscape, lagging behind the development of private areas by at least a generation. This pattern is also typical of the urbanism and architecture of mid-republican colonial foundations. In a city in which we still do not even know the location of the original forum, our understanding of functional areas and zoning remains imperfect, making it difficult to contextualise properly the few known instances of public architecture and to define different traditions, especially in order to identify the influence or agency of Rome in these processes. Finally, a landscape perspective would complement the view from the urban centre and enable an analysis of the settlement patterns in the ager Gabinus during the transition into the post-archaic period, with the goal of assessing whether rural occupation was affected in similar ways.Footnote 98

But the main findings and conclusions that we have presented regarding the vicissitudes of early republican Gabii have important wider implications for the field. The possibility of now weaving the different threads of Gabii's archaeological sequence into a coherent narrative for a historical period (the ‘dark’ fifth century) surrounding which there is considerable scepticism, demonstrates the value of — and the need for — large-scale excavation and survey at sites that are part of the first wave of urbanisation in central Italy. The unparalleled contextual evidence that has been gathered in relation to the significant destruction and abandonment event has allowed us to revisit old problems and assumptions, and to write the first systematic history of the devotio of Gabii in light of the material record. Beyond Gabii, this history sheds new light on some crucial moments in the early Republic. As we have suggested, the intentional refoundation of Gabii after a hiatus in occupation is bound up with other interesting social and political dynamics that are the subject of much ongoing debate about the nature of early Roman expansion. While Gabii was exceptional in many ways, especially in terms of the settlement and burial patterns through the pivotal phase of transition, our detailed reconstruction of the events surrounding the remaking of the city contributes to the discussion by highlighting the actual mechanisms through which factionalism and private elite agendas influenced urban developments and interstate relationships in the core region of Roman hegemony, tracing the repercussions well into the period that followed the launch of the new colonisation programme after the final conquest of the Latins in 338. More broadly, the case study of Gabii can be taken as a starting -point for reassessing Roman attitudes towards the ‘unmaking’ of cities, and how this tool could be deployed in the context of the development of Roman imperialism.