The notion that Capitolia were a standard feature of Roman urbanism in the Western provinces, a model exported from Rome itself, is central to many influential studies of Roman urbanism. Over the last 160 years, studies on provincial Capitolia specifically and Roman cities generally have argued or assumed that Capitolia were common or normal features of Roman cities in the central and western Mediterranean, and of colonies in particular; that they typically stood on or overlooking fora and were planned on a common axis with them; and that they can be recognized by their tripartite cella and high podium.Footnote 1 While notes of caution or indeed doubt on several of these points have from time to time been sounded, those authors who have questioned some of these points have maintained others, and the general idea is alive and well today. This paper aims to show how slender are the foundations of that view, and argues that far from being a normal feature of urbanism propagated by Rome, Capitolia in the provinces are a regionally patchy phenomenon, whose popularity was locally driven and developed gradually over time; and that they may not in fact have been especially common outside Italy and North Africa. Although they were closely identified with rituals honouring Roman emperors and the Roman state, their localized popularity requires local explanations.

I CAPITOLIA, COLONIES AND URBAN FORM: THE CREATION OF A MYTH

The history of scholarship on Capitolia is an illuminating place to start. The idea that Capitolia are a standard feature of Roman colonies goes back at least to Du Cange's Glossarium Mediae et Infimae Latinitatis, published in 1737. In his entry under Capitolium, Du Cange gives a list of so-called Capitolia in early medieval sources and paraphrases Aulus Gellius' comment that ‘colonies seem to be as it were small replicas and in a sense likenesses’ of the Roman people (‘… populi Romani, cuius istae coloniae quasi effigies paruae simulacraque esse quaedam videntur’),Footnote 2 with an added gloss that they therefore had theatres, baths and Capitolia:

Non sola porro duntaxat Roma Capitolium habuit, sed et aliae complures ex majoribus, illius exemplo, atque adeo in ipsa Gallia urbes, et ex iis illae potissimum quae Coloniae populi Romani erant: nam ut ait Gellius: erant Coloniae quasi effigies parvae Populi Romani, eoque jure habebant Theatra, Thermas et Capitolia.

Moreover, it was not only Rome that had a Capitolium, but also very many others of the more important cities, after the model of Rome, and especially in Gaul itself; and among them especially those which were colonies of the Roman people: for as Gellius says: ‘colonies were so to speak little images of the Roman people, and by that right they had theatres, baths and Capitolia.’

Du Cange presented his paraphrase as though it were Gellius' actual text,Footnote 3 with predictable confusion for later scholars who did not check the original; it encouraged a subsequent and widespread misinterpretation of Gellius' passage as suggesting that colonies were physical replicas of Rome — Gellius was in fact talking about the institutional and juridical similarities, not any physical resemblance — and in several widely-read later works, from early studies of provincial Capitolia by Braun and the entry on Capitolia in Daremberg and Saglio's very influential Dictionnaire des antiquités, to scholarship of the 1960s,Footnote 4 it is assumed or stated that Gellius himself had said that Roman colonies had theatres, baths and Capitolia as a matter of course.

Du Cange also noted, however — as had Scipio Maffei a few years before him, in 1732Footnote 5 — that in early medieval sources the sense of the term Capitolium meant a pagan temple in general (‘templum paganorum, vel locus ubi sacrificare cogebantur Christiani’), and sometimes acquired the broader meaning of ‘citadel’ or ‘fortress’.Footnote 6 St Jerome, for instance, discussing the city of Babylon in his early fifth-century commentary on Isaiah, includes this description of the famous tower: ‘But the Arx, that is to say, the Capitolium of that city, is a tower that was built after the Flood, said to be four [Roman] miles high … they describe marble temples there, golden statues, streets shining with jewels and gold, and many other things that seem almost incredible.’Footnote 7 Clearly the word here evokes not a temple but a citadel, on the model of the Capitoline Hill, and Isidore of Seville (Etym.) makes this clear, offering the definition: ‘arx [id est] capitolium.’

Long after Maffei and Du Cange's observations, the first work devoted to the question of provincial Capitolia was by Braun in 1849 (Table 1, see Appendix), but it is rather slight and vitiated by its uncritical use of sources, including Du Cange and the Acta Sanctorum.Footnote 8 Twenty years later, Castan's work on the supposed Capitolium of Vesontio (Besançon) provided the first systematic attempt at a treatment of provincial Capitolia, listing eleven in Italy, five in Gaul, one in Germany, four in the East and three in Africa (Table 1).Footnote 9 It predates much archaeological work in North Africa, so it misses many examples there, and also omits the Greek inscriptions from Asia Minor.Footnote 10 From the examples he identified, Castan argued that provincial Capitolia were a privilege accorded by the imperial government exclusively to colonies.Footnote 11 Although he was evidently trying to find a clear-cut schema for provincial Capitolia, he did note that despite the precepts of Vitruvius (De Arch. 1.7), Capitolia were not always built on eminences.Footnote 12

Oscar Kuhfeldt's dissertation De Capitoliis imperi romani (1883) expanded the number of identifications of provincial Capitolia (Table 1). He discussed sources (inscriptions, coins, ancient writers, the Acta Sanctorum, and medieval documents which, typically, preserve a form of the word ‘Capitolium’ in place- or property-names), then individual sites with what he regarded as Capitolia first in Italy and then in Spain, Africa, Greece and Thrace, Asia, and finally Gaul. Justifiably, he considered epigraphy and the remains of temples as the best sources, but he also drew attention to coins of the eastern Empire (issues of Aphrodisias and Heliopolis) with Latin inscriptions, mentioning Kapetolia (Capitoline Games).Footnote 13

Just as Maffei and Du Cange had pointed to the late antique extension of the term Capitolium to mean ‘citadel’, Kuhfeldt noted, as had Maffei 150 years earlier, that in Late Antiquity Capitolium seems to have become a simple synonym for pagan Roman religion or temples in general, by contrast with Christianity and churches.Footnote 14 How early this usage began among Christian writers is unclear; Cyprian in the mid-third century opposes the Church to the Capitolium, and seems to be using the word in this more general sense.Footnote 15 A passage of Tertullian's De Corona (12.3; early third century) could be taken either way:

Ecce annua votorum nuncupatio, quid videtur? prima in principiis, secunda in Capitoliis. Accipe, post loca, et uerba : ‘Tunc tibi, Iuppiter, bouem cornibus auro decoratis uouemus esse futurum.’

And then the annual taking of vows, how does that seem? First in the camp head-quarters, then in the Capitolia. Attend to the words as well as the places: ‘We vow, Jupiter, that you shall have an ox with horns decorated in gold.’

If Capitoliis is here meant in its original sense, this passage might provide important evidence for the widespread existence of Capitolia in the provinces and their rôle in offical cult linked to public displays of loyalty to the emperor. But doubts arise: Tertullian may be simply extrapolating from Carthage (which we know did have a Capitolium), and in any case he needed a polysyllabic word to balance principiis to effect a strong clausula at the end of the sentence; templis would not work in the same way. The sacrifice is to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and certainly where Capitolia existed we can be sure that the annual sacrifice for the health of the emperor did take place in them; but it is possible that in other cities such sacrifices took place in other temples, for example of Jupiter alone. It is difficult to use this passage as certain evidence for the ubiquity of Capitolia, and indeed the nineteenth-century Ante-Nicene Fathers edition translates the word simply as ‘temples’, in accordance with other early Christian usage:

Lo the yearly public pronouncing of vows, what does that bear on its face to be? It takes place first in the part of the camp where the general's tent is, and then in the temples. In addition to the places, observe the words also: ‘We vow that you, O Jupiter, will then have an ox with gold-decorated horns.’Footnote 16

Irrespective of the precise interpretation of this passage, the corollary of the changes in meaning in late antique and medieval usage, seen by Scipio Maffei but not always followed through by Du Cange or subsequent scholars, is that references to Capitolia in hagiographic sources, medieval charters or toponyms are not reliable evidence for the existence of a Capitolium in the sense of a Roman temple to the Capitoline Triad. The Acta Sanctorum, frequently cited in discussions of provincial Capitolia, are especially unreliable.Footnote 17

Kuhfeldt urged extreme caution when using late sources generally and the Acta Sanctorum in particular.Footnote 18 Nonetheless, he still accepted some identifications of Capitolia based on those sources. He believed that Capitolia were common, even universal in Italy under the Empire,Footnote 19 and he accepted rather too readily the evidence from the East — coins from Antioch in Caria showing Zeus Kapetolios depict him with Victoria and Fortuna, not Juno and Minerva; priests of Zeus Kapetolios at Nysa and Smyrna, and a dedication to Zeus Kapetolios at Teos, while attesting the cult of Jupiter Capitolinus (as Zeus Kapetolios), do not quite add up to hard evidence for a temple of the Capitoline Triad.Footnote 20 Kuhfeldt also assumed that the link between Capitolia and coloniae was significant and worth exploring; each entry in his study has something on the status (colonial or otherwise) of each town. He realized, however, that Castan was incorrect to maintain that only coloniae could have Capitolia; municipia could have them too.Footnote 21 Nevertheless, he believed that more coloniae than municipia had Capitolia, and that this was because colonies were Gellius' quasi effigies parvaeque simulacra; indeed, he claims that major cities in provinces are those with Capitolia, to be like a second Rome for the province.Footnote 22

Kuhfeldt's publication prompted Castan to produce a new study, with a revised and expanded list of provincial Capitolia, including several North African examples attested in inscriptions discovered since his first essay, in which he reaffirmed his view that only colonies could have Capitolia.Footnote 23 Kuhfeldt's and Castan's studies, and the conclusion that Capitolia were standard features of colonies (whether or not limited to them), were picked up by the great encyclopaedic tradition of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and lists of provincial Capitolia were repeated (sometimes with slight variations) in the entries on Iuppiter by E. Aust in Roscher's Ausführliches Lexicon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie Footnote 24 and on Capitolium in Ettore de Ruggiero's Dizionario epigrafico di antichitá romane,Footnote 25 both accepting uncritically the evidence of the Acta Sanctorum. Saglio's entry in the Dictionnaire des antiquités (1887) aligned itself firmly with Castan's view on the special, even juridical, association between Capitolia and colonial foundations, perpetuating the error initiated by Du Cange: ‘Si maintenant on remarque que, parmi les villes actuellement connues pour avoir possédé un capitole, il n'en est guère pour lesquelles on ne soit assuré qu'elles étaient des colonies, on sera disposé à admettre que pour elles la construction d'un capitole ne fut pas seulement une imitation ambitieuse de Rome, mais la loi même de leur fondation, puisqu'elles avaient reçu avec leur institution et leur droit, les dieux et le culte de la métropole. «Les colonies, dit Aulu-Gelle étaient comme des images réduites de la cité romaine, et c'est pourquoi elles avaient le droit d'avoir comme Rome des théâtres, des thermes et aussi des capitoles.»’Footnote 26 The entry in Pauly-Wissowa (1897) was more judicious, distinguishing cautiously between the different categories of evidence and noting that the hagiographical sources are less secure. Despite noting the total absence of true Capitolia in the East, with the sole exceptions of Hadrian's Aelia Capitolina and the probably Constantinian Capitolium built for his New Rome, it maintained the by then traditional idea that there was a significant association with colonial status (while admitting some exceptions).

At the end of the nineteenth century René Cagnat and Paul Gauckler provided a list of inscriptions and descriptions of possible or certain Capitolia in Tunisia, which consolidated the evidence then known; this is of particular value for the architectural descriptions and drawings and photographs of some temples now destroyed or since heavily restored, but offers no analysis or synthesis.Footnote 27 Also in 1899, J. Toutain published his Étude sur les Capitoles provinciaux de l'empire romain, an article which updated the lists of provincial Capitolia drawn up by Kuhfeldt and Castan, rejecting the more dubious examples founded on medieval toponyms, but adding some new discoveries on the basis largely of epigraphic evidence and drawing on Cagnat and Gauckler. He erroneously considered temples to Jupiter Capitolinus as Capitolia, and so included Antioch in Syria, of the second century b.c., and Panticapaeum on the Cimmerian Bosphorus, second century a.d.; but in general his discussion here and in his later summary in Les cultes païens is cautious and sensible.Footnote 28 Toutain notes that Braun relied uncritically on late texts such as the Acta Sanctorum, as Castan and Kuhfeldt had argued; but he critiques Castan and Kuhfeldt too for their over-reliance on late charters and toponyms which do not predate a.d. 1000, by which time ‘Capitolium’ was being used probably exclusively in its medieval sense of citadel or a pagan temple in general. He also pointed out that no law or custom restricted Capitolia to colonies (contra Castan), since they are found in municipia and peregrine cities too.Footnote 29 He realized that a triple cella is not in itself evidence of a triple cult,Footnote 30 but he accepted the idea that provincial Capitolia copied Rome in form, or at least in concept (‘un désir évident de rappeler plus ou moins exactement le Capitole romain’).Footnote 31 He makes several interesting observations on the geographical distribution of attested Capitolia: they are found in Africa, Spain, and Gaul, and are rare on the Danube and absent in the Germanies, but dedications of Capitoline cult without temples are the reverse — few in Africa, rare in Spain and Gaul, numerous along the Rhine, in the Pannonias and in Dacia.Footnote 32

In their authoritative handbook on Roman archaeology (1916), Cagnat and Chapot cemented the by then increasingly common view that Capitolia were part of a standard package of urban features to which Roman cities, and not just colonies, aspired: ‘Aussi les villes de province, colonies, municipes et même cités pérégrines, s'empressaient-elles, dès qu'elles le pouvaient, d’éléver à la triade Capitoline un sanctuaire, image de celui de la capitale. On en a trouvé dans de nombreuses localités. Le type qu'on imitait était, naturellement, le Capitole de Rome, dont on connaît très bien le plan; c'est celui du temple toscan. La cella était divisée en trois chambres, disposées parallèlement dans le sens de la longeur; au centre celle de Jupiter, la principale; à droite pour qui regardait l'édifice, la chapelle de Junon, à gauche, celle de Minerve.'Footnote 33

The view that Capitolia had a special colonial significance proved remarkably hard to dislodge. In 1941 Michelangelo Cagiano de Azevedo attempted to revisit the subject, and to update the studies of Braun, Kuhfeldt and Castan on the basis of the excavation finds made over half a century or so since Castan wrote. He swelled the list to a claimed 130 or more Capitolia, but most of these were identified on very flimsy grounds — the mere presence of a triple cella, or a high podium, or a commanding position was often sufficient for him. His list is so uncritically inclusive as to be of little value. Nevertheless, his study both reflected the standard view that Capitolia were very common in the Western Empire and especially in colonies, and helped to reinforce it.

In 1950 Ugo Bianchi published a study of the Capitoline cult which took a more restrained view than Cagiano de Azevedo on the number of provincial Capitolia (Table 1), and sought to identify a chronological development in the association between Capitolia and colonies. He argued that after Signia, the oldest Capitolia belonged to the second century b.c., and all were in cities of colonial status. Capitolia were built particularly in colonies in the first century of empire, but in the second century a.d. and at the start of the third numerous Capitolia were built in cities of varied status, especially in Africa, but particularly in cities which had in some measure assimilated the civil and religious institutions of Rome. He saw Capitolia as an official, ‘national’ cult: ‘un Capitolium fu molto di più che un tempio qualsiasi dedicato alla divinità del Campidoglio; esso, imagine ridotto ma fedele, dal punto di vista strutturale, e, più, cultuale, del santuario urbano, fu la sede del culto cittadino della triade capitolina, culto proprio di ogni città che avesse assume le istituzioni e le costumanze di Roma, perchè rappresentava appunto il culto nazionale per eccellenza del popolo romano.’Footnote 34

In his studies of Cosa, which had a profound influence on studies of Roman urbanism and on Roman colonies throughout the second half of the twentieth century,Footnote 35 Frank Brown simply assumed that Cosa's temple on the arx was a Capitolium, apparently on the basis of its lofty position and its triple cella, but he never offered any hard evidence for the identification.Footnote 36 This fitted his view that Cosa was a mini-Rome, which meant that the Capitolium had to be a copy of the one at Rome.Footnote 37 Grimal's survey of Roman cities (1954) declares succinctly that ‘De même qu’à Rome le Temple de Jupiter Très Bon et Très Grand, associé à Minerve et à Juno, domine le Forum romain, il n'est guère de forum provincial qui ne comporte aussi son “Capitole”, consacré à la même triade.'Footnote 38

Ian Barton's survey of ‘Capitoline temples in Italy and the Provinces’ for Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt (1982) was a more careful reassessment of Cagiano de Azevedo and Bianchi's lists, with some updating, and a useful full list of the various African examples (Table 1). A particular strength of the work is that he points out the numerous exceptions to the standard view; but he nevertheless remains reluctant to abandon that view completely — many Capitolia do not have a triple or tripartite cella, and there are non-Capitoline temples that do have one, but he still sees a triple cella as a defining feature (see further below); he acknowledges that there is no real connection between colonial status and the possession of a Capitoline temple, but in discussion of individual temples still attempts to find such a link.

This attitude is reflected in subsequent scholarship: studies on forum-temple complexes in the Western provinces by Todd (1985), Gros (1987), and Blutstein-Latrémolière (1991) assumed that many temples on fora were necessarily Capitolia, and then used this assumption to argue that Capitolia were normally placed in dominant positions on the forum; in reality, few or none of the examples they used can be shown to be Capitolia.Footnote 39 In 1995 Gargola could affirm: ‘… Roman colonies possessed certain highly standardized elements. From the fourth century, the urban core was organized around a square or forum and a high place or arx, and clustered around those places (and elsewhere in the town) was a range of public buildings and temples, including a Capitolium patterned after the temples of Jupiter Best and Greatest on the Capitol at Rome.’ He goes on to cite Cosa as an example.Footnote 40

A Capitolium, then, is still widely seen as a reproduction of the original Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill at Rome (Fig. 1), with a schematic replication of the spatial relationship between that temple and the Forum Romanum which lay beneath it: according to the Oxford Classical Dictionary, ‘Both hill and the temple of Jupiter were reproduced in many cities of Italy and (especially the Western) provinces’.Footnote 41 And as Todd puts it, ‘The most prominent site in the city must be reserved for the Capitoline Triad, according to Vitruvius (1.7.1), presumably to echo the siting of the Capitolium in Rome itself. What topography could not provide was often afforded by a high podium …’Footnote 42 Much of this standard view persists in the entry on Capitolia in Brill's New Pauly (2003), and in a recent Blackwell's Companion of 2006.Footnote 43

FIG. 1. Rome, alternative reconstructions of the Capitolium: (a) plan by E. Gjerstad; (b) plan by G. Cifani; (c) axonometric drawing by J. W. Stamper; (d) plan by A. Mura Sommella (Arata, op. cit. (n. 64), figs 28, 29, 30 and 31).

Furthermore, despite the various studies that from Kuhfeldt and Toutain onwardsFootnote 44 have pointed out that there is no real correlation between the distribution of known Capitolia and the colonial status of Roman cities, the idea that Capitolia are a standard feature of a Roman urban package, and a particular feature of colonies, based ultimately on the misreading of Aulus Gellius,Footnote 45 has proved surprisingly tenacious.Footnote 46 Paul Zanker, in an article published in 2000 on ‘The city as symbol: Rome and the creation of an urban image’, still sees Capitolia as central elements of Republican colonies in Italy: ‘This main road going through the city leads to, or past, the Capitolium situated at the intersection of cardo and decumanus … The gathering place of the community lies in front of the Capitolium. … it is clear that the orientation of the Capitolium at the central square of the city, which would later become such a common feature and indeed canonical in Italy and the western provinces, is already implicit in this early city plan.’Footnote 47 He develops this idea for Augustan colonies: ‘The long-distance road traversing the city implies a sense of belonging to a large entity. The same is true of the siting of the Capitolium in the center of the community, which clearly defines it, both for the locals themselves and for visitors, as belonging to Rome. In early times in particular, this novel form of city plan, made more evident through repetition, must have taken on the character of a deliberate message.’Footnote 48

At the same time, the wider interpretation of coloniae as ‘mini-Romes’, at least in a physical sense, has been persuasively challenged in recent years: in essays that both appeared in 2000, for instance, Fentress disassembled the supposed colonial type-site of Cosa, and Bispham used a case-study of Ostia to suggest that there were few ‘“deliberately prescriptive” processes’ in the foundation of Republican colonies;Footnote 49 some years later, Bispham tackled mid-Republican colonialism more holistically, suggesting that: ‘“Little Romes”, founded after ritual ploughing, and kitted out with a standard topography and infrastructure which recall the urbs (city), have … to be treated for what they are, namely late-republican and Augustan discourses, which evolved in the context of re-shaping an identity for a far-flung and recently divided empire.’Footnote 50 The relationship between Capitolia and colonial foundation has been called into question as part of this reassessment (usually without reference to the earlier debate between Kuhfeldt, Castan and Toutain): Fentress points out that the supposed Capitolium at Cosa was built long after the colony's foundation,Footnote 51 and Bispham notes that ‘Ostia may never have had a Capitolium’,Footnote 52 as well as rejecting those identified at Cosa and Minturnae.Footnote 53 Beyond Italy, Beard, North and Price deny an ‘immutable blueprint’ for religious activity in Rome's colonies abroad, and note that while ‘some coloniae certainly built Capitolia immediately at the time of their foundation: there are second-century b.c. coloniae in Spain with their own Capitolia’, others chose to build them ‘only later if at all’.Footnote 54

Nonetheless, the link between Capitolia and the Roman legal status of a city persists in the scholarship. Although Bispham convincingly refutes this connection for the mid-Republic, even for him ‘by the late Republic the Capitoline Triad had established itself as the normative model of Roman colonial cult’,Footnote 55 and he sees a Capitolium built at Luna shortly after its foundation in 177 b.c. as an example of the way in which ‘it was becoming unthinkable that a Roman colony should not have a temple to the Capitoline Triad’.Footnote 56 With regard to the Imperial period, Beard, North and Price suggest that from the second century a.d. the Capitoline cult ‘that in the first century a.d. had been confined to coloniae (and Rome itself) was taken over by municipia as part of their display of Roman status’; they deal with exceptions by suggesting that ‘that sequence may also be reversed; and on more than one occasion we can see the building of a Capitolium as part of a claim for Roman status (rather than a boast of Roman status already acquired)’.Footnote 57 Looking in particular at Africa, van Andringa has recently suggested that: ‘It is no surprise, therefore, to see that in the provinces of Africa, most of the Capitolia were constructed in the second and the beginning of the third centuries ad, the period when most of the cities were promoted to the status of municipium and or colony. At Sabratha the successive procurement of the status of municipium and then colony was further sanctioned by the construction of an imposing Capitolium in the monumental center that already contained a temple to Liber Pater and Serapis. At Cuicul (Djemila) it seems that the Capitolium was built at the time of the colony's foundation, under Nerva or Trajan.’Footnote 58

Like Toutain,Footnote 59 we do not see any clear and consistent link between the construction of Capitolia and the award of colonial or municipal status, whether from the beginning or developing over time. We agree with Bispham that the evidence for Republican Capitolia at Cosa, Minturnae and Ostia is negligible, but we would go further: we see no better evidence for Luna, the Spanish Republican colonies or Sabratha; there is more (if still very incomplete) evidence for Cuicul, but we would date the temple so identified there substantially later than the colony's initial urbanization.Footnote 60 In fact, certain evidence for Capitolia is not common in Italy, and is rarer still in most provinces, with the exception of Africa where they clearly flourished — for a limited period of time. This is difficult to reconcile with the idea that Capitolia are a standard feature of the Roman colonial or more generally urban model. Our argument in the following pages aims to show the fragility of the evidence on which this view rests; the certain examples of Capitolia are far fewer than the major studies accept, and even recent scholarship has interpreted the wider significance of the phenomenon within the parameters originally established by Du Cange, Braun, Castan and Kuhfeldt. A number of our basic points were adumbrated by Barton; so entrenched, however, was the view of Capitolia as a standard feature of Roman urbanism that he sought to explain the points we raise below as exceptions, rather than following through the implication that they in fact overthrow the traditional view. None of our arguments is intended to suggest that Capitolia were not of great importance or that they did not display a strong symbolic link with Rome. Indeed, the late antique use of the term to mean pagan temples in general, or citadel, is testimony to the symbolic power of the Capitolium of Rome as appreciated throughout the provinces. Our point is to show that this has nothing to do with Republican or early Imperial colonization, or with the colonial status of cities; and that the idea of a Capitolium on a high point of town, or dominating the forum, was not the standard, centrally propagated, item of Roman town planning that it has frequently been presented as being. In fact, we would argue that they may in many respects have been unusual, and that instead of one overarching explanation for the foundation of Capitolia, such as a city's legal status, there will have been local reasons for why they become popular in particular regions. We turn now to the problem of how Capitolia can be identified, and then survey the evidence for Capitolia in Italy, in the provinces outside Africa, and finally in Africa.Footnote 61

II IDENTIFYING CAPITOLIA

One easy way to identify Capitolia is to look for buildings that are already labelled as such in inscriptions or texts.Footnote 62 The first Capitolium that we hear of in Rome — the Capitolium Vetus — was, according to Varro, a shrine (sacellum) on the Quirinal to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, which was ‘older than the temple that was built on the Capitoline’.Footnote 63 It seems that it was soon superseded: Pliny says that Tarquinius Priscus began (inchoaverit) the Capitolium on what became the Capitoline hill with the spoils from Apiolae (3.70).Footnote 64 As the quotation from Varro shows, the word is also used — in a transferred sense, if Varro both is right in saying that the Capitolium Vetus was the older building, and should be understood as implying that it was called a Capitolium even at that timeFootnote 65 — for the southern crest of the Capitoline hill (as opposed to the Arx) on which the second temple was built. The Capitoline Temple built by Tarquinius Priscus was destroyed in the civil war between Sulla and Marius in 83 b.c., and rebuilt by Q. Lutatius Catulus on the original foundations; and this temple in turn was destroyed when Vespasian's troops besieged Vitellius' forces on the Capitol in a.d. 69. Vespasian rebuilt it, but it was destroyed again in the fire of a.d. 80 and rebuilt by Domitian, the new temple being dedicated in a.d. 89.Footnote 66 The precise design and appearance of these various versions is a matter of dispute — reliefs and coins variously represent the temple as either hexastyle or tetrastyle, the latter probably being a device to allow the doors of the three cellae to be shown more clearly.Footnote 67 Dionysius of Halicarnassus describes the temple as having a deep porch with three rows of columns, and a triple cella (Jupiter in the centre, flanked by Juno on his right and Minerva on his left).Footnote 68 The early temple had a low, heavy roof, and the rebuilding by Catulus attempted to remove this defect, within the limitations imposed by the religious necessity of rebuilding on exactly the same foundations.

There are some literary and rather more epigraphic attestations of the word Capitolium used of temples outside Rome, and the traditional assumption — which we largely share, with the reservations about late antique and later texts described above — is that as at Rome, these were temples dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus with subsidiary cults to Juno Regina and to Minerva.

A set of criteria to identify Capitolia which are not so labelled is laid out by Ian Barton in his 1982 survey of ‘Capitoline temples’:Footnote 69 the presence of cult statues of the three divinities ‘conforming to the traditional pattern of a seated Iuppiter flanked by Minerva (on his right) and Iuno (on his left)’;Footnote 70 a dedication to the Capitoline Triad; the form of the building itself; and a dominating situation, either in the highest place or in the centre of the town.Footnote 71 All these principles however require some qualification.

The presence of cult statues of the three divinities seems to us a sound indicator of a Capitolium, though we would emphasize that a representation of just one of the three divinities does not necessarily point to this particular kind of temple; it is the combination that is distinctive. Furthermore, a dedication to the Capitoline Triad — Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno Regina, and Minerva (often Minerva Augusta) — in the context of a primary building inscription can indeed be regarded as evidence for the identification of that building as a temple and a Capitolium. All three divinities should be mentioned, however, or be straightforwardly restorable. Examples of individual dedications and temples to Juno ReginaFootnote 72 or Minerva AugustaFootnote 73 alone are insufficient to identify Capitolia.

Nor is the dedication of a temple to Jupiter Optimus Maximus necessarily a reference to Jupiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus; he also comes in other versions. Jupiter Optimus Maximus Dolichenus was the object of a second-century a.d. cult that spread from Commagene to the Aventine,Footnote 74 Jupiter Optimus Maximus Heliopolitanus was worshipped at Baalbek, and at Deir el-Qalak, overlooking Berytus, there is a dedication to Jupiter Optimus Maximus Balmarcod (‘Lord of Dances’).Footnote 75 A less exotic example comes from Capua, where the Tabula Peutingeriana locates the sanctuary of ‘Iovis Tifatinus’. Three dedications found on the summit of Monte Tifata itself include one simply to Jupiter Tifatinus, dated palaeographically to as early as the mid-first century b.c., one from around the second century a.d. to IOT — Jupiter Optimus Tifatinus, and one, from around the first century a.d., to IOMT — Jupiter Optimus Maximus Tifatinus.Footnote 76 Although his hilltop location invites comparison with that of Jupiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus, this Jupiter Optimus Maximus is not just not Capitoline, but, as with those in Asia, positively marked as non-Capitoline. The single instance that we have found in which a building explicitly identified as a Capitolium by its building inscription is dedicated to a variant incarnation of Jupiter is the Tetrarchic Capitolium at Segermes in North Africa. Here the temple was dedicated to Jupiter Conservator, Juno Regina and Miner[va Augusta], and in this case the particular epithet for Jupiter is explicable by assimilation to the imperial propaganda of the period, including Diocletian's identification with Jupiter and the emphasis on Jupiter Conservator on contemporary coinage.Footnote 77

We would also stress, with Kuhfeldt and Barton,Footnote 78 that the presence of a dedication by itself, outside the context of a particular building and not obviously a building inscription, cannot be taken as evidence that there was such a building. We must distinguish between the mere existence of Capitoline cult, or the popularity of the Capitoline Triad, and the construction of temples dedicated to them.

We find the other characteristics that Barton calls into service in the identification of Capitolia less convincing. Firstly, there are problems with the idea that the design of a Capitolium should necessarily recall the one in Rome. According to Barton this means a high podium approached by steps, a pronaos with columns, and a cella capable of containing the three cult statues.Footnote 79 This would certainly make sense, but there is actually very little positive evidence for the model — not only because there are so few authenticated Capitolia outside Africa to check, but also because there are so many temples in Italy and Africa that are demonstrably not Capitolia but which have a high podium, frontal emphasis, a pronaos defined by columns, and a cella large enough to house the three statues: by the Augustan period this is the standard type in the Western Mediterranean. Moreover, the variety of designs of provincial temples which are certainly Capitolia, including tetrastyle and hexastyle examples, and with a wide variety of cella arrangements, argues against the idea that all provincial Capitolia were intended to resemble physically the Capitolium in Rome.

To narrow the field down, a tripartite cella is often taken as a defining characteristic of a Capitolium,Footnote 80 an arrangement attested for the temple at Rome.Footnote 81 For Barton himself, the cella of a Capitolium is ‘often, but not necessarily, physically divided into three longtitudinal divisions’,Footnote 82 and although he accepts that it does not have to be thus physically divided, he sometimes uses a physical division in part or in whole to identify a Capitolium that is otherwise entirely unattested.Footnote 83 But this simply does not work: a tripartite cella is described by Vitruvius as the norm for all ‘Tuscan’ temples,Footnote 84 and it is in fact the preferred design in many larger central Italian temples during the Republic, such as the second-century b.c. temple of the Dioscuri at Cori, and the great temple at Pietrabbondante, which would make a surprising Capitolium (Fig. 2).Footnote 85 Outside Italy, the Qasr al-Bint at Nabatean Petra has a tripartite cella, as does the temple of Artemis at Parthian Dura Europos, to take just two striking examples. As we discuss below, however, none of the certain Capitolia in Africa demonstrably has a triple cella, although several have tripartite substructures. At Dougga, for instance, while three temples besides the Capitolium (those of Mercury, Tellus and Saturn) have a triple cella,Footnote 86 the Capitolium itself has a single cella with three bays for the cult statues (Fig. 3).Footnote 87 In many cases the identification of a triple cella is in fact based on the existence of three vaulted chambers in the substructures of the temple podium; the extrapolation from these to a three-chambered cella above is logical, but not certain.Footnote 88

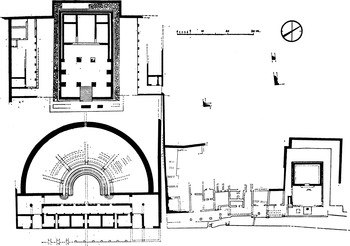

FIG. 2. Pietrabbondante: plan of the temple with a triple cella (not a Capitolium) above the theatre (M. J. Strazzulla, Il Santuario sannitico di Pietrabbondante (1973), fig. 1).

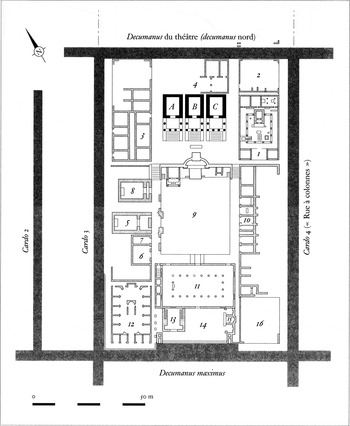

FIG. 3. Dougga: plan of the forum and Capitolium (Poinssot, op. cit. (n. 265), fig. 2).

Nor does the dominating situation of a temple — either on high or on a podium — seem persuasive evidence; at least, not by itself. The notion of the Capitolium occupying the highest place in a town is extrapolated both from the topographical situation at Rome and from the famous passage in Vitruvius where he advises his readers looking to build a fortified town on where to site the public buildings:

aedibus vero sacris, quorum deorum maxime in tutela civitas videtur esse, et Ioui et Iunoni et Mineruae, in excelsissimo loco unde moenium maxima pars conspiciatur areae distribuantur. Footnote 89

But for the sacred shrines of those gods under whose particular protection the community is thought to be, [and] for Jupiter and Juno and Minerva, the sites should be distributed on the very highest point commanding a view of the greater part of the walls of the city.

The purely modern idea that Capitolia dominate the forum surely derives in great part from the more general idea of domination expressed in this passage, but Vitruvius is claiming here to describe an ideal, not the situation in any existing city: he was an aspiring architect of the Roman imagination at least as much as of Roman colonies.Footnote 90 Vitruvius' image of a temple to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva on a great height within the city does seem to map in a general sense onto the picture at Rome itself, and it is an interesting question how much Vitruvius' description of the ideal new city is in fact a rhetorical re-description of the old one.Footnote 91 It is worth noting, however, that the model's implicit comparison with the temple in Rome towering above its own forum is difficult to reconcile with the actual alignment of that building; while the Capitolium at Rome was certainly visible from the Forum Romanum, it was significantly off-axis from its alignment, and over time an increasing number of other temples came to dominate the Forum more immediately.

Furthermore, while plenty of Italian cities did have temples in high places by the time Vitruvius was writing, for none of these is there good independent evidence identifying those temples as Capitolia. For instance although a Republican-period Capitolium was identified by Frank Brown on the ‘Arx’ at Cosa, as noted above, this was part of what Fentress has shown to be his desire to see Cosa as a mini-Rome; Brown's positive identification based on the temple's high location and its form, including a tripartite cella, which for him recalls (but does not reproduce) that of the Capitolium at Rome, has been comprehensively refuted by Bispham.Footnote 92

In this paper we take the only definite markers of a Capitolium to be (1) a clear description as a Capitolium in a building inscription, or (2) a building inscription with a dedication to at least two of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno and Minerva (with the third restorable in a lacuna), or (3) the remains of cult statues likely to represent at least two of those divinities associated with a temple structure. We then use these attested examples to reassess the distribution, form and urban placement of provincial Capitolia. The Capitolia that we regard as certain or probable are summarized in the final column of Table 1 and mapped in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4. Distribution map of certain and likely Capitolia. (Map by Jack Hanson)

III CAPITOLIA IN ITALY

Judging by these conservative criteria, Capitolia are not found in great numbers in Italian towns. There are references to only two Italian Capitolia outside Rome in ancient literary sources before the early Middle Ages (though of course we should not expect detailed topographical information from our Rome-focused literary sources): Suetonius tells us about a statue at Beneventum which is in Capitolio,Footnote 93 and twice refers to a Capitolium at Capua, dedicated by Tiberius on his way to Capri in a.d. 26, which is also mentioned (as Capitolia) by Silius Italicus.Footnote 94 Five more Capitolia are referred to in inscriptions from Italy, at Marruvium Marsorum,Footnote 95 Falerio in Piceno,Footnote 96 Histonium in Samnio,Footnote 97 Verona,Footnote 98 and Formiae.Footnote 99 None of these is a building inscription, but it seems certain that the references are to local Capitolia. Two more cases are less certain: a small altar at Faesulae concerns the restitutio of a Capitolium,Footnote 100 and a recently published later first-century a.d. inscription from Herculaneum mentions a refectio of a Capitolium:Footnote 101 in both cases the reference could be to a local temple, or to the temple in Rome. The inscription from Faesulae is particularly interesting because here, uniquely outside Africa, we find the name ‘Capitolium’ applied to a temple on an inscription in association with a dedication to the Capitoline Triad.Footnote 102 None of these nine Capitolia can be identified for certain with a particular building, though a partially excavated temple with tripartite foundations to the north of the forum at Verona and dated in its earliest phase to the second half of the first century b.c. has recently been published in detail as the city's Capitolium (Fig. 5).Footnote 103

FIG. 5. Plan of the forum and probable Capitolium at Verona. The Capitolium, at the top of the figure, is enclosed within a porticus triplex and the foundation arrangements indicate a deep porch with three rows of columns, recalling the Capitolium at Rome (Cavalieri Manasse, op. cit. (n. 39), Tav. 2).

This identification of the Capitolium at Verona can be regarded as probable. The late fourth-century inscription mentioned above records that a senator transferred a statue that had been lying in the Capitolium and re-erected it in the forum: ‘statuam in Capitolio diu iacentem in celeberrimo foro loco constitui iussit.’ Cavalieri Manasse's detailed publication of the remains of a massive temple enclosed in a U-shaped portico in an area immediately north-west of and dominating the forum and occupying a space equivalent to a city block shows how the foundations clearly reflect the load-bearing elements above; the temple had a particularly deep porch, with three rows of columns, represented at foundation level by piers linked by walls and separated by void spaces. Cavalieri Manasse reconstructs the substructures as divided with a triple barrel vault on the basis of the traces of a wall stub (which would separate the central from the north-east unit) in the foundations aligned with the columns of the porch; the load-bearing arrangement of the rest of the foundations would in this instance reasonably suggest that the cella above was tripartite.Footnote 104 The porch with three rows of columns does seem to recall the arrangement of the Capitolium at Rome itself, although, as noted above, the exact reconstruction of that is still a matter for controversy. There is nothing explicit to identify this temple as the Capitolium, but given the epigraphic attestation of a Capitolium at Verona (possibly close to the forum),Footnote 105 it seems very plausible; the discovery in the area of the temple podium of a statue base with a dedication to Jupiter Optimus Maximus by the ordo Veronensium also provides support for this view.Footnote 106

One other building can, on our criteria, be definitely identified as a Capitolium, at least from the Flavian period, although it is nowhere named as such: this is the third-century b.c. temple with a high podium on the forum at Cumae that acquired a tripartite cella in a reconstruction dated in recent excavations to the late first century a.d. (Fig. 6).Footnote 107 Crucially, colossal heads of Minerva and Juno were found here, evidently from cult statues, and the colossal Jupiter known as the ‘Gigante di Palazzo’ discovered around 1640 may well come from this temple as well.Footnote 108 A similar situation may be found at Aquinum, near Frosinone in Lazio: two colossal and expressionless female heads were reported during the 1827 excavation of a temple with a tripartite cella in the highest part of the town. But they have now disappeared, and so without sight of them we are not as confident as the excavators in identifying them as Athena (i.e. Minerva) and Juno.Footnote 109

FIG. 6. Cumae: plan of Flavian phase temple with tripartite cella. S1, S2, S5 and S6 are the locations of 1994 excavation trenches (Gasparri et al., op. cit. (n. 107), fig. 3 p. 46).

One other known temple is associated with the name ‘Capitolium’, at least in a medieval context: the temple with late Republican and early Imperial phases, both of which had tripartite foundations from which a triple-cella arrangement has been extrapolated,Footnote 110 under the now-demolished church of S. Maria in Campidoglio in Florence, fronting the Roman forum. In this case the combined evidence of the toponym, the location on the forum and the probably triple cella make the identification attractive. However, as noted above, such medieval toponyms are by no means a certain guide: the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, known from its building inscription to have been dedicated to Gaius and Lucius Caesar, was by the fifteenth century flanked by the chapel of St Étienne-du-Capitole; and we have seen how in the Middle Ages the term Capitolium might mean ‘citadel’, or simply ‘temple’.Footnote 111

The Capitoline identification has also been suggested for many other temples excavated in Italy, usually on the basis of their (more or less certain) tripartite cella, or their topographical location; we will pause here over only the best known examples. The case for a Capitolium at Ostia rests on a dedication to Mars that was found in Rome, in which one A. Ostiensis Asclepiades describes himself as aeditu(u)s Capitoli.Footnote 112 This could well be a reference to the Capitolium in Rome itself, although Meiggs argues that ‘since the name recurs in the roll of members of the familia publica of Ostia, and since his dedication was made to them, it is reasonably certain that the Capitolium in question is Ostian’.Footnote 113 It is often further assumed on the grounds of its ‘size and dominating position’ that the Hadrianic temple on a high podium at one end of the forum at Ostia is the Capitolium mentioned in this inscription.Footnote 114 If this edifice is a Capitolium, it is interesting that it has a single cella; the raised podium at the back of the cella on which one or more cult statues presumably stood consists of a triple-vaulted substructure, although there is no direct evidence for how many statues it supported.Footnote 115 It is also interesting that in the first century a.d., when two smaller temples stood on the site of the Hadrianic ‘Capitolium’,Footnote 116 it may have been the Tiberian temple of Roma and Augustus at the other end of the forum that more strikingly dominated the public space in terms of visual axiality, as at Lepcis Magna (discussed further below).

A second example is the single-cella temple that sits on a high podium at the north end of the forum at Pompeii (Fig. 7). The phasing is very complex, but it is generally agreed that the first phase belongs to the second century b.c., before the Sullan colony; that there was a major restructuring at some time in the first century b.c. (dated by Second Style painting in the cella) that is not necessarily to be connected with the foundation of the Sullan colony; and that there was then a third phase, accompanied by restuccoing and the repaving of the pronaos.Footnote 117 The substructures of the podium consist of vaulted chambers in a tripartite alignment, but even if these were to imply a tripartite cella above, they belong to the first phase of the temple, before the Sullan colony, and cannot therefore be used to identify the temple as a Capitolium connected with that colony.Footnote 118 In the second and third phases the cella was certainly not divided into three, although as in the supposed Capitolium at Ostia, there are three small vaulted chambers, identified as favissae, in a podium at the back of the cella that originally supported the cult statue(s). They measure 1.66–69 by 1.83–85m, and one has to stoop to enter the door.Footnote 119 These triple favissae do not imply a triple cult, but simply a multiplication of small secure strongrooms under the statue base — which might or might not have supported three statues.

FIG. 7. Plan of the Temple of Jupiter at Pompeii (L. Richardson, Pompeii: An Architectural History (1988), fig. 19).

The consensus is that the temple was originally dedicated to Jupiter but was rededicated as a Capitolium when, or after, the Sullan colony was founded.Footnote 120 According to Barton this identification as a Capitolium is unequivocal,Footnote 121 but we cannot agree. The evidence consists of the remains of a colossal seated cult statue of Jupiter, over 5.5 m tall,Footnote 122 and a marble plaque with a dedication to Jupiter Optimus Maximus for the well-being of the emperor Gaius, which dates it to a.d. 37.Footnote 123 However, there is no evidence for dedications to or statues of Juno and Minerva,Footnote 124 and even the identification of the temple with Jupiter Optimus Maximus is uncertain: the dedication to him was written on the back of an earlier Greek dedication from 3 b.c., by a Gaius Iulius Hephaistion to Zeus Phrygios. A temple of Jupiter this definitely was, whether simply Jupiter, or Phrygian or Optimus Maximus, but there is no solid evidence for the identification of it as a Capitolium; once again, this identification seems to be a product of the widespread view that colonies had Capitolia in their fora. The assertion found in some standard reference works that Vitruvius (3.2.5) refers to the Capitolium of Pompeii is based on a mistranslation.Footnote 125

The claim of the temple on the forum at Brixia (Brescia) to be a Capitolium has often been advanced,Footnote 126 on the basis of its three cellae accessed by a single staircase, and its dominant position overlooking the forum, but the evidence does not go much beyond that. A fragment of a colossal seated male statue, well over life-size (5 m high), might be Jupiter, or any of several other male deities; but a head of Minerva in archaizing style is much smaller (life-size).Footnote 127 The inscription across the façade has the imperial titulature of Vespasian (a.d. 73), and little room for anything else;Footnote 128 this and the extraordinary cache of gilt-bronze statues of members of the imperial family from the Flavian period to the mid-third century, and a bronze Victory writing on a shield,Footnote 129 raise the possibility that this temple had something to do with the imperial cult (not in itself necessarily incompatible with the idea of a Capitolium). This was certainly Brixia's main and most impressive temple, but that fact in itself does not force its identification as a Capitolium. Similarly, the identification of the so-called Capitolium at Luna is based solely on its plan and location — the presumed reconstruction of a triple cella on top of the surviving foundations, set within a U-shaped colonnade overlooking the forum and separated from it by a transverse streetFootnote 130 — but this is a common late Republican or Imperial arrangement in which other cults are also attested.Footnote 131

There is at present no positive evidence to identify any other temple in Italy as a Capitolium. Of the nineteen Italian Capitolia outside Rome identified in Barton's 1982 survey, then, we would accept as certain only eight (Beneventum, Capua, Cumae, Formiae, Falerio in Piceno, Histonium in Samnio, Marruvium Marsorum, and Verona). To only two of these can we with some confidence attach a specific building (at Cumae, and probably Verona), though of course the continued urbanization on the sites of most Roman cities means that few temples of any kind survive. Inscriptions at Faesulae and Herculaneum might refer either to Capitolia there or to the one at Rome, and evidence that has been presented for a few further identifications of existing buildings — at Aquinum, Brixia, Florentia, Luna, Ostia, and Pompeii — is either problematic or less than compelling, and we can see no positive evidence at all for Barton's identifications of Capitolia at Asisium, Liternum, Minturnae, Teate Marrucinorum, Tergeste or Terracina, nor for those identifications made by others at Aquileia, Aosta, Bologna, Capua, Nesazion, Pola, Pozzuoli, Privernum, Scolacium, and Grumentum.Footnote 132

Our findings underline among other things how difficult it is to say much about the standard topographical position or design of Capitolia in Italy. Only at Cumae and probably Verona do we have both a Capitolium and the forum; the temple is on the forum there, however, as it is in the less certain cases of Florentia, Ostia, Pompeii, and Brixia (though in the latter three examples the position of the temple on the forum has been used as part of the argument for their identification, which cannot then be used in turn to help establish the idea that Capitolia were normally on the forum). Again, the temple at Cumae was given a triple cella in its late first-century a.d. reconstruction, but with no definite comparanda there is no clear reason to think that this was the norm.

More importantly, our proposed reduction in the number of confidently identifiable examples in Italy exposes the lack of evidence for the supposed relationship between Capitolia and the award of colonial status, at least on the Italian evidence; breaking the link between colonization and Capitolia puts another nail in the coffin of the approach to Rome's Italian colonies that sees them as mimicking the capital. Seven of our eight certain Capitolia in Italy became Roman colonies at some point — Marruvium (like Herculaneum) remained a municipium — but in the only case where the temple can be confidently dated, at Cumae, the dates show no certain correlation with colonial foundation or status.Footnote 133 The recent excavations there have shown the Capitolium to have fourth-century b.c., Augustan and Flavian phases;Footnote 134 Cumae was given civitas sine suffragio in 338 b.c., and granted colonial status under Augustus,Footnote 135 either of which might but need not be related to building phases of the temple, although the excavators date the reconstruction of the cella into a tripartite structure to the Flavian phase.Footnote 136 By contrast, the colony at Capua was founded in 83 b.c., and increased several times, but not in the reign of Tiberius, who dedicated the temple there in a.d. 26.

IV PROVINCIAL CAPITOLIA

There are very few certain Capitolia in Roman provinces other than Africa, and as in Italy none of those that do exist can be shown to date from earlier than the Julio-Claudian period; most of them are much later. In Britain, there is no evidence for Capitolia; British cities tend to have forum-basilica complexes without temples in the forum at all, as at London, Silchester and Lincoln.Footnote 137 Despite a substantial number of dedications to the Capitoline Triad in some Western provinces, the situation found in Britain is in fact the norm. There is, for instance, good evidence for only two Capitoline temples in Spain, at Hispalis (Sevilla), where a fragmentary inscription mentions a [st]atuam in Capit[olio],Footnote 138 and Tarraco (Tarragona), a second-century dedication to a curator Capitoli.Footnote 139 Neither can yet be identified with certainty with any physical remains; a very partially excavated structure next to the lower forum at Tarraco has recently been interpreted as the podium of a temple with a triple cella, which is then assumed to be the Capitolium mentioned in the inscription, but others have wished to see the Capitolium as being located in the higher part of the city.Footnote 140

At Baelo Claudia the three side-by-side temples erected as an integrated structure on a terrace overlooking the forum have usually been identified as a kind of composite Capitolium (Fig. 8), like the complex at Sufetula in North Africa,Footnote 141 but triple temple structures on the forum need not form a Capitolium; they are rare and we know of no cases in which they definitely do. At Baelo the easternmost of the three temples contained a statue of a seated goddess, which may be Juno; fragments of statuary in the western temple also indicate a female deity, unidentifiable; but togate statues were added to the statue plinth in the central temple which apparently represent imperial portraits and thus suggest an admixture of imperial cult — again, not necessarily incompatible with the idea of a Capitolium. Perhaps the strongest argument in favour of the possible interpretation of the temples at Baelo as a Capitolium complex is the altar arrangement on the esplanade in front of the three temples; a single base seems to have supported three stone altars (two of which were actually discovered) in front of the central temple, and this may imply a common ritual of sacrifice to all three divinities in the temples — but even if so, that would not necessarily imply that they were the Capitoline Triad.Footnote 142 Against the view that together they constituted a Capitolium, it has recently been argued that the three temples display neither architectural nor chronological unity: the central and western temple are dated c. a.d. 50, the eastern temple c. a.d. 65; architectural mouldings and dimensions are different, and the central temple is somewhat smaller than the others, which would certainly be unexpected in a Capitoline complex. Bendala Galán thus argues that these are three separate temples arranged in a row, and further suggests that this disposition is traceable to Punic influence.Footnote 143

FIG. 8. Baelo Claudia: plan of triple temple complex overlooking forum (Bonneville et al., op. cit. (n. 141), fig. 4).

For the rest of Spain, there are no certain examples, although Capitolia have been claimed for numerous sites. Blutstein-Latrémolière's study on ‘Les places capitolines’, for example, although it notes the shortcomings of earlier works and the unreliability of medieval toponyms, is nevertheless vitiated by the fact that in the numerous temple precincts or temple-forum complexes it discusses, not a single temple is proven to be a Capitolium.Footnote 144 Previous identifications of the temples under discussion as Capitolia are simply accepted, usually on the basis of nothing more than a (definite or supposed) tripartite cella and/or a location on the forum (e.g. Emporiae/Ampurias, Pollentia, Saguntum,Footnote 145 Mérida, Corduba, Tarraco, and Italica); and on the basis of this, a whole new category of ‘Capitoline fora’ is invented, defined by the fact that there is a Capitoline temple on the forum. The circularity of the argument should be obvious. Gros, likewise, accepts that the temples of the first half of the second century b.c. whose foundations have been discovered at Saguntum and Italica are Capitolia because they have a triple cella and their proportions conform to the schema of Tuscan temples;Footnote 146 but as noted above, that is the standard Italic type for many temples in Italy in the second century b.c., which provides the model for Republican Spain, and proves nothing about their specific dedications.

In Gaul, however, there are three positive identifications from literary sources, of which one can certainly be accepted; the late date of the others, written at a time when ‘Capitolium’ had begun to be used sometimes to mean ‘citadel’ or ‘temple’ generally, may raise doubts. Eumenius mentions a Capitolium at Augustodunum (Autun) in his late third-century Panegyric; and the fact that he distinguishes it from a temple of Apollo and specifically lists Jupiter, Juno and Minerva confirms that we really are dealing with a temple of the Capitoline Triad here.Footnote 147 In the fifth century, however, Sidonius describes the fate of St Saturninus at Tolosa (Toulouse): ‘Of these [martyrs] may he be the first theme of my hymn who held the bishop's throne at Toulouse and was flung headlong from the topmost step of the Capitolia’ (note the plural); a variant of the story is also given by Gregory of Tours in the sixth century.Footnote 148 A large temple on the Place Esquirol has been identified as this Capitolium,Footnote 149 but there is no hard evidence to link it specifically to the Capitoline Triad. At Narbo Martius too, Sidonius Apollinaris lists not a Capitolium, but Capitolia, among the city's attractions, apparently part of a wider tendency in this author to use plural for singular — or is the late usage meaning ‘temples’ already manifesting itself here?Footnote 150 There is little concrete to relate this comment to the temple situated above the Roman forum on Les Moulinassès that has been labelled a Capitolium since the eleventh century, though excavations have shown this to be a very large temple (larger than the Capitolia at Timgad or Cirta) with a triple division of the podium, and architectural elements in Carrara marble.Footnote 151 A dedication which may be to Jupiter Optimus Maximus — only a part of the M is extant — was discovered in the excavations of 1883,Footnote 152 dedicated by a sevir Augustalis, as were others also found in the same circumstances, which may in turn point to a link between the Capitolium — if the medieval toponym is really enough to establish this identification — and imperial cult worship, as Gayraud suggests.Footnote 153

In Ödenburg in Austria (ancient Scarbantia, Pannonia) the marble fragments of three second-century colossal seated statues of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, some two-and-a-third times life-size, were found in a single-cella temple 9.8 m wide, with three deep niches of which the central one was 2 m wide, during the construction of the town hall in 1894. They must surely represent the cult statues of the Capitolium of Scarbantia; significantly, fragments of a seated imperial statue at the same scale were also found with them, suggesting here also some association between Capitoline and imperial cults. The cult statues had been deliberately smashed into pieces, an action attributed by Praschniker, not unreasonably, to late antique Christians.Footnote 154 At Savaria, also in Pannonia, excavations for the foundations of a cathedral in 1777 uncovered the torso of a colossal statue of Jupiter and another of Minerva, and a fragmentary third large statue (since lost), presumably Juno.Footnote 155 Again, these must be the cult statues from a Capitolium, and their position in the centre of the early modern town appears to reflect a central position in the ancient town too.

A third site in Pannonia, Arrabona (modern Raab), is worth mentioning: an inscription from here records the repair of a temple to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno Regina, Minerva, Liber Pater, Diana and ceterisq(ue) dibus (sic) by a cornicularius of Legion I and his wife; this temple seems in fact to be a Pantheon of sorts, dedicated to all the gods, but the Capitoline Triad are named first.Footnote 156 Finally, the evidence for the claimed Capitolium at Gorsium (Tac, Hungary) is not compelling.Footnote 157

In other Western provinces, there are no certain examples. A ‘Capitolium’ at Aalen in Rhaetia was restored in a.d. 208, but the inscription recording the event makes it clear that this was a shrine in the principia of the army camp, not a civic temple.Footnote 158 A dedication to I. O. M., Juno Regina and Minerva at Troesmis in Moesia Inferior is unlikely to be a building inscription.Footnote 159 A temple with three cellae on the forum at Aenona in Dalmatia, near which was found a statue of Juno, presents a possibility.Footnote 160 The late first-century a.d. temple under the church of Sankt Maria im Kapitol in Cologne is intriguing on the grounds, as at Florentia, of the medieval toponym S. Maria in Capitolio, although with the same reservations noted above in relation to that example;Footnote 161 the surviving foundation walls indicate three vaulted chambers in the substructures of the cella.Footnote 162 This may be a Capitolium, though as we have noted, triple-vaulted substructures need not necessarily imply a tripartite division of the cella above, and in any case a triple cella is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for an identification. If this is a Capitolium, then its location well away from the forum in the south-east of the city is worth noting.Footnote 163

In the Eastern provinces there were Capitolia at Jerusalem and Constantinople, Oxyrhynchus, and possibly Cyrene, and although the widespread evidence for the cult of Zeus Kapetolios (Jupiter Capitolinus) must be distinguished from temples of the Capitoline Triad (below), it is in the East that the ideological significance of Capitolia as a physical reminder of Rome is clearest.

Hadrian's refoundation of Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina, with a temple to Zeus Kapitolios on the Temple Mount, was a blatant imposition of Roman religion and urbanism onto Jewish sacred space that provoked the Bar Kochba revolt in a.d. 132.Footnote 164 Among the Hadrianic coinage of Aelia Capitolina is a bronze ?dupondius issue showing Jupiter seated in a distyle structure, flanked by Juno and Minerva (both standing), suggesting that the temple of Zeus Kapitolios here was indeed, as the new name of the city would also suggest, a true Capitolium.Footnote 165

A Capitolium is attested at Constantinople,Footnote 166 and is said in one of the manuscripts of Hesychius to be a Constantinian foundation, along with lavish houses which he built κατὰ μίμησιν Ῥώμης, ‘in imitation of Rome’.Footnote 167 It seems that it was part of a necessary cultural package in refounding the new Rome at Constantinople. Nothing is known of its design or appearance; Janin argues it lay between the Forum Bovis and the Philadelphion, along the south side of the Mese at the junction with the street from the Golden Gate, probably on a height in what is now the Şahzade quarter of Istanbul.Footnote 168 Hesychius also mentions Constantine's repair of the pagan temples and the building of a number of churches, reflecting the religious ambivalence of his construction programme. The use of the Capitolium at Constantinople as a temple of the Triad can hardly have outlasted the closure of pagan temples in the fourth century, and in the early fifth century it had become Christianized at least to the extent of having a cross placed on the top of it (although it is nowhere referred to as a church), which fell down in a violent storm in a.d. 407.Footnote 169 It subsequently became — or perhaps had already become — a sort of university: a law of 27 February 425 refers to an auditorium there and makes provision for teaching in it of Latin, by three professors of rhetoric and ten of grammar, and of Greek, by five sophists and ten grammarians; in addition, there was a professor of philosophy and two professors of law.Footnote 170 The fifth-century Latin grammarian Cledonius taught here, and makes reference to an incident in a class in the Capitolium.Footnote 171

At Cyrene, the temple of Zeus immediately south of the agora was rebuilt in the Roman period after the Jewish Revolt, as a tetrastyle, prostyle temple. An almost completely reconstructable cult statue of a standing Zeus was found within the single cella, over life-size in Parian marble, with sceptre, aegis and eagle, and fallen from its base (3.60 m wide with a Hadrianic inscription of a.d. 139 referring to Hadrian's rebuilding or redecoration of the city and tois agalmasin — the statues which stood on the base). Controversy reigns over whether fragments of two other statues, one of Athena and the other of another female, whether mortal or divine is unclear, are to be considered associated with the Zeus. Found by Smith and Porcher in 1861, they are now in the British Museum; their findspots are not closely recorded, but seem to have been either in or very near this temple.Footnote 172 Some have identified the three statues together as the Capitoline Triad;Footnote 173 Chamoux on the other hand points out that all three statues are of different scales (their heights are: Zeus, 2.18 m high; Athena (headless), 1.44 m; and the other statue (also headless), 1.63 m); and that Zeus represented with the aegis is associated on coins with the legend Zeus Soter/Jupiter Conservator and that one of a pair of altars nearby was dedicated to Zeus Soter; he proposes that the base may have held a pair of statues of Zeus Soter and Athena Soteira.Footnote 174 Tempting as it is to see this temple as a Capitolium, and its conversion from a prior temple of Zeus in the rebuilding of Cyrene after the Jewish Revolt as an act of ideological significance similar to Hadrian's Aelia Capitolina at Jerusalem, this is pure hypothesis and other interpretations of the temple are possible or even likely.

In the other Eastern provinces no surviving remains can be identified as Capitolia, and although there are several examples in the written sources of temples to Zeus Kapitolios, that is to say Jupiter Capitolinus, it is not clear how many of these included the worship of Juno and Minerva as well. At Antioch in Syria Antiochus IV Epiphanes began a temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, evidently as a statement of loyalty to Rome, with lavish gold panelling internally, but it was left unfinished on his death in 164 b.c.;Footnote 175 it was subsequently completed or restored by Tiberius.Footnote 176 The account (anonymous and undated) of the martyrdom of Julian, Basilissa, Celsus and their companions refers to a Capitolium at a city called Antioch, which might be any of the fourteen Antiochs in the East but may well be Antioch in Syria as it also lays stress on the gold and silver panelling of the temple; that we are dealing with a Capitolium to the full triad (at least in the mind of the author of the text) and not simply of Jupiter Capitolinus is shown by the explicit mention of electrum and gold statues inside it of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.Footnote 177 Coins of Antiochia in Caria struck under Antoninus Pius, with the legend Zeus Kapitolios Antiocheon, show Jupiter in a tetrastyle temple, holding a Victory in his right hand and a spear in his left; it is significant here that Juno and Minerva are not shown, and this is probably a cult of Jupiter Capitolinus alone.Footnote 178 Similarly, priests of Zeus Kapetolios are attested at Smyrna,Footnote 179 and Nysa in Caria,Footnote 180 and there are indications of his cult also at Teos (Lydia),Footnote 181 but none of this evidence suggests the cult, still less a temple, of the Capitoline Triad. Finally, Pausanias mentions a temple at Corinth: ‘above the theatre (ὑπὲρ δὲ τὸ θεατρόν) is a temple to Zeus called Kapetolios in the language of the Romans; in the Greek tongue this might be rendered Zeus Koryphaios’ (i.e. Zeus the Highest).Footnote 182

The Oxyrhynchus papyri contain several references to a Kapitolion in the city,Footnote 183 including a payment of 2,500 drachmas to the contractors for the doors of the Kapitolion, in the late second century.Footnote 184 A document dated a.d. 261 is an offer to lease the workshop below the east colonnade of the Kapitolion with a view to opening a tavern.Footnote 185 This suggests that the Kapitolion here may have stood in its own colonnaded precinct. From the third century, we possess an invitation from one Serapion to a feast in the Kapitolion to celebrate the epikrisis of his son.Footnote 186 Two documents of a.d. 325 record proceedings before the logistes, held πρὸς τῷ Καπιτωλί![]() , ‘in front of the Kapitolion’.Footnote 187 That the Kapitolion was a place for the transaction of civic business appears to be confirmed by an early fourth-century papyrus from the Oxyrhynchite nome mentioning a forthcoming sale of land belonging to the fiscus which is to be held, according to custom, in the Kapitolion, doubtless at Oxyrhynchus itself.Footnote 188 From Tebtunis, a third-century a.d. petition refers to land owned by the city and by Zeus Kapitolios, which may either be temple lands or refer to the function of the Kapitolion as a city treasury, as at Oxyrhynchus, and also at Carthage, Cirta and Theveste in North Africa (see below).Footnote 189 At Arsinoe there is a set of accounts from a.d. 215 for the temple to Zeus Kapitolios, where rituals with particular reference to Rome were celebrated, such as holidays celebrating anniversaries of the accession of the emperor and the foundation of Rome, on which the statues of gods and men were hung with garlands (cf. Tertullian, de Corona 12.3, discussed above); a colossal statue of Caracalla was also erected in the temple.Footnote 190 There is, however, no mention in these accounts of Juno or Minerva.

, ‘in front of the Kapitolion’.Footnote 187 That the Kapitolion was a place for the transaction of civic business appears to be confirmed by an early fourth-century papyrus from the Oxyrhynchite nome mentioning a forthcoming sale of land belonging to the fiscus which is to be held, according to custom, in the Kapitolion, doubtless at Oxyrhynchus itself.Footnote 188 From Tebtunis, a third-century a.d. petition refers to land owned by the city and by Zeus Kapitolios, which may either be temple lands or refer to the function of the Kapitolion as a city treasury, as at Oxyrhynchus, and also at Carthage, Cirta and Theveste in North Africa (see below).Footnote 189 At Arsinoe there is a set of accounts from a.d. 215 for the temple to Zeus Kapitolios, where rituals with particular reference to Rome were celebrated, such as holidays celebrating anniversaries of the accession of the emperor and the foundation of Rome, on which the statues of gods and men were hung with garlands (cf. Tertullian, de Corona 12.3, discussed above); a colossal statue of Caracalla was also erected in the temple.Footnote 190 There is, however, no mention in these accounts of Juno or Minerva.

Of the non-African provincial Capitolia, then, we accept Hispalis and Tarraco in Spain, Augustodunum, and, with the terminological hesitation outlined above, those at Narbo, and Tolosa in Gaul; Savaria and Scarbantia in Pannonia; perhaps Cologne in Germany; and certainly Jerusalem and Constantinople, and Oxyrhnchus. Antioch, Corinth, Arsinoe and Tebtunis are possibilities, depending on whether one should equate a temple of Zeus Kapitolios with a Capitolium. We find no compelling evidence for those suggested at Aenona, Brigantium and Virunum,Footnote 191 and are equally unconvinced by claims for Xanten and Zara.Footnote 192 Presumably there were in fact more Capitolia than this in the provinces: we admit the possibilities of the other examples claimed by Barton, but we are simply arguing that there are very few credibly attested Capitolia, and we question the wider assumptions that have resulted from more optimistic identifications that see them as a regular and necessary part of a Roman urban model exported from Italy, or one that was regularly included to reify a symbolic link with Rome. As in Italy, a link between Capitolia and provincial colonies (or municipia) is unclear: Tolosa remained a civitas throughout its existence, and only at Jerusalem and Constantinople can we see an association with something like colonial foundation, but these are both special circumstances where the ideological loading of the Capitolia built there goes far beyond normal colonial foundations. While these cases stress the importance of the symbolic attachment between provincial Capitolia and Rome, it is significant that in neither case does the city seem to have had a Capitolium before the reigns of Hadrian and Constantine respectively. Furthermore, there is too little evidence on the location of the definitively identified Capitolia to establish a close and regular link between Capitolia and forum space in the provinces outside Italy.

V AFRICAN CAPITOLIA

In the North African provinces there is more evidence for Capitolia — evidence that both marks Africa out as special, but also confirms the lack of correlation between Capitolia and colonial status, and that Capitolia are not a regular feature of city foundations in the Roman Empire, or even necessarily of urban development. Rather, they seem to result from particular local circumstances and initiatives.