BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Pelvic radiotherapy plays an important role in the treatment of women with cervical or endometrial cancer. Radiation for gynaecological cancer may be delivered internally (brachytherapy) and/or externally and may be given alone or in combination with surgery and/or chemotherapy. Treatment is often delivered with curative intent or in the adjuvant setting. Consequently, many women are living with the long-term effects of radiation treatment to the pelvis.

The occurrence of vaginal stenosis, or shortening and narrowing of the vagina following irradiation of the vaginal mucosa is well recognised. It is a chronic side effect resulting from the development of fibrotic tissue and adhesions, which may eventually compromise or obliterate normal vaginal capacity. Radiotherapy may also compromise the elasticity of the vaginal wall, decrease vaginal lubrication, and result in the development of telangectasia increasing the vagina’s susceptibility to trauma and infection.Reference Greimel, Winter, Kapp and Haas1

The impact of vaginal change following pelvic radiotherapy on a woman’s sexual health is well documented,Reference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2–Reference Bertelsen6 with studies demonstrating a link between the degree of vaginal stenosis and the severity of sexual dysfunction.Reference Abitbol and Davenport7–Reference Bergmark, Avall-Lundqvist, Dickman, Henningsohn and Steineck10 The physical development of scar tissue and adhesions may lead to dyspareunia and post coital bleeding. Psychological issues relating from anticipatory pain or fear of disease recurrence may also interfere with the normal sexual cycle resulting in an indirect effect on sexual health. It is the integration of physical and psychological changes following pelvic radiotherapy that requires complex, holistic management to optimise sexual rehabilitation.Reference Punt, Booth and Bruera11

Sexual health aside, a key aspect of maintaining a patent vagina facilitates optimal follow-up by ensuring the vaginal vault (for post hysterectomy patients) or the cervix can be adequately examined or visualised without causing significant discomfort.Reference Nunns, Williamson, Swaney and Davy12 This facilitates detection of central recurrences and therefore the best possible chance of salvage.

For those women who wish to maintain a patent vagina, either to optimise sexual function or facilitate vaginal examination, post radiotherapy vaginal dilation is imperative. This process separates the vaginal mucosa, breaks down developing adhesions (or fibrotic tissue), and expands the repairing vaginal tissue. This may be achieved either with regular intercourse or the use of vaginal dilators.Reference Denton and Maher13

In the literature, there remains a shallow evidence base for the optimal process of vaginal dilation. The time frame over which vaginal stenosis develops has been infrequently examined. Three studies have reported varying results. PomaReference Poma14 found the maximum development of scar tissue occurred at 3 months post-treatment while Flay and Matthews.Reference Flay and Matthews9 found 12 out of the 16 (73%) patients studied had significant stenosis at 6 weeks. In contrast, Hartman and Diddle.Reference Hartman and Diddle15 found that 6 out of 221 patients studied developed total vaginal obliteration within 1 month.

There is also a lack of evidence to define how long the vaginal dilators should be inserted for, however, several authors have made recommendations. Cartwright–AlcareseReference Cartwright-Alcarese5 suggest 10 minutes daily but at least three times a week. DecruzeReference Decruze, Guthrie and Magnani16 recommended daily insertions with no mention of length of insertion time.

In 2003, a Cochrane review of relevant literature addressing interventions for the physical aspects of sexual dysfunction following pelvic radiotherapy concluded that there was sufficient evidence available to support approval for the widespread provision of dilator information.Reference Denton and Maher13 The conclusions drawn from this review were the driving force behind the conception of national guidelines for the use of vaginal dilators and management of vaginal stenosis. The document, which was published in July 2005, was written by the National Gynaecological Oncology Nurse Forum with input from specialist nurses and researchers and reviewed by practitioners responsible for current service delivery.

The national guidelines recommended that women should begin using vaginal dilators within 2 weeks of completing radiotherapy, and that they should continue use indefinitely. The recommended frequency of use is three times a week and each insertion should last between 5 and 10 minutes.

Current practice

Since the national guidelines were published the information given within the author’s cancer centre has reflected the published recommended guidelines.

Following completion of all radical gynaecological radiotherapy treatment, women receive a dilator kit, written information, and a one-to-one interview with either the advanced practitioner or the Macmillan consultant radiographer in gynaecological oncology. The written information provided explains how to use the vaginal dilator and how often while the practitioner demonstrates how the dilator kit should be used. Women are advised to use the dilator for 5–10 minutes and at least two-three times per week. Currently no written information is given on sexual health issues or on the management of vaginal atrophy, although these issues should be discussed during the interview if appropriate.

There are no provisions made for a follow-up interview, although telephone contact details are given should the patient wish to discuss further. A psychosexual clinic, run by the author, is also available for the women to self refer if appropriate.

Justification for study

The guidelines have now been in place for almost 10 years with no evaluation of patient compliance to their recommendations. Earlier studies have suggested that patient compliance is low and some researchers have evaluated the impact of intervention on compliance rates. A small study by Schover et al. in 1989Reference Schover, Fife and Gershenson17 found only 4 (14%) of patients at 6 months were using dilation three times a week and at a year just one patient was found to be compliant.

In contrast a small Canadian study evaluated the impact of vaginal dilator compliance following intervention within a psychoeducational group Robinson et al.Reference Robinson, Faris and Scott18 They found that 46.6% of their study population (21/45) complied to some form of vaginal dilation (dilators or coitus) three times a week at 3 months in the intervention arm and only 5.6% in the control arm (brief counselling and written information). A prospective longitudinal study by Jeffries et al. also concluded that psychoeducational group intervention increased vaginal dilator compliance, supporting effectiveness of the information-motivation-behavioural skills model. 11.4% (3/26) of the intervention group dilated three times a week at 6 months compared to 4.7% (1/21) in the control group.Reference Jeffries, Robinson, Craighead and Keats19

The study by Robinson et al.Reference Robinson, Faris and Scott18 concluded that intervention, which not only provides information but also addresses motivational issues and behavioural skills, is more likely to have a positive impact on dilator compliance.

Hypothesis

Within the author’s cancer centre women receive information and support on the use of vaginal dilators in accordance with the national guidelines. However, an assumption of low patient compliance in following recommendations may be justified in light of previously published studies.Reference Robinson, Faris and Scott18,Reference Jeffries, Robinson, Craighead and Keats19 Design of an appropriate national, patient centred information leaflet with user input and individual counselling to address information-motivation-behavioural issues will ensure design and delivery of an optimal care package resulting in higher compliance rates and improved sexual health.

STUDY AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

Primary aim of study

The aim of the study was to evaluate the current compliance rate with the national recommendations on the use of vaginal dilators within a single large cancer centre. Compliance was defined as the use of vaginal dilators two-three times a week (or more) at 6 months post-treatment. Non-compliance was defined as vaginal dilation less than twice a week.

Secondary aims

To evaluate compliance at 12, 18, and 24 months and to identify any significant trends in compliance when measured against age, disease site, treatment modality, and vaginal symptoms.

Compliance was measured using a postal questionnaire which generated data on the frequency of vaginal dilator use, patient demographics, and vaginal symptoms.

ETHICS

Ethical approval was sought and gained through the integrated research application system and Cambridge University Hospitals National Health Service Trust Research and Development department. Patient and Trust confidentiality in accordance with Trust policy was maintained at all times. Data will be protected and stored in the Trust information technology department backed-up file servers for 10 years, as required by Trust policy.

A favourable opinion was awarded from the Essex 1 research ethics committee in July 2009.

METHODOLOGY

Study sample

The sensitive nature of this study in dealing with sexual issues and vaginal dilation may have potential to influence the validity and reliability of the outcome measures. Ensuring anonymity of the information gathered will facilitate the greatest possible patient confidence and therefore increase the reliability of information gained.

The primary outcome of the study was to evaluate the compliance rate with good precision as measured by the 95% confidence interval (CI). If the study included 130 women, then the compliance would be estimated with precision at most ± 10%, allowing for a 20% drop out. For example, a compliance rate of 50% would be estimated with 95% CI between 40% and 60%.

The statistical tool used for the power calculation was nQuery V4.0.

Statistical advice and assistance with power calculations was sought from the Centre for Applied Medical Statistics (CAMS), Cambridge.

Participants

Patients who had received pelvic radiotherapy and/or brachytherapy at Cambridge University Hospital for cervical or endometrial cancer between January 2006 and December 2008 were eligible for the study. Potential participants were identified using the radiotherapy patient record system, Lantis. In total 485 women were identified. Last clinic letters of each patient were then reviewed using the local electronic patient management (eMR) system. Patients who had died were identified and excluded from the study. Women with recurrent or progressive disease were also excluded from the study to minimise bias towards non-compliance or altered compliance as a result of active disease.

The hospital number of each eligible participant was entered in to a secure data base and then each potential participant was posted an information sheet inviting them to take part in the study, a questionnaire and a stamped addressed envelope.

Consent to enter the study was assumed if the participant completed and returned the questionnaire.

A total of 164 questionnaires were sent out between August 2009 and December 2009.

Materials

An 18-point postal questionnaire was designed to capture current dilator use, compliance, and vaginal symptoms. Points 1–4 related to demographics including age, disease site, and treatment type. Points 5–11 examined dilator use including time from end of treatment to first use, frequency of use during the first 6 months, and current use. Points 12–18 scored vaginal symptoms and were lifted from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) CX24 validated questionnaire with kind permission of EORTC.Reference Greimel, Winter, Kapp and Haas1 A pilot of five women was undertaken to ensure the questionnaire was fit for purpose.

A self-completed postal questionnaire methodology was chosen to offer anonymity and confidentiality due to the sensitive nature of the study. Since the sample size was already small, a postal study would allow patients discharged from follow-up to also be included therefore maximising the number of potential study participants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicargo, IL, USA). Advice was also sought from the CAMS, Cambridge University. Simple descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic details. Questions relating to vaginal dilator frequency used an ordinal scale for example 0 = no use or less than once a week, 1 = daily, 2 = alternate days or three times a week, 3 = twice a week, 4 = once a week. For the purpose of analysis this variable was collapsed in to two categories, compliant, and non-compliant (1, 2, and 3 coded as compliant. 0, 4 as non-compliant). One-at-a-time analysis was carried out to test if compliance was independent of age, treatment type, disease site or vaginal symptoms. Mann–Whitney U and Fisher’s exact test were used with p-values less than 0.05 regarded as statistically significant.

A one-sample χReference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 test was also performed to compare compliance rates obtained in this study with those presented in a previously published study.

RESULTS

Sample size

One hundred and sixty-four questionnaires were sent out with 46% (75/164) participants returning a completed questionnaire and one participant returning a blank questionnaire.

Out of the 75 completed questionnaires one participant had not been offered vaginal dilators and therefore has been excluded from the statistical analysis.

Missing data

Four patients did not answer questions about vaginal symptoms (vaginal irritation, bleeding, and discharge). One of these respondents had not been offered vaginal dilators. The remaining three patients were all compliant at 6 months. One further patient failed to detail frequency of use of dilators in the last 4 weeks; this patient was compliant at 6 months and did not have any vaginal symptoms.

Demographics

Seventy-four patients were included in data analysis. The demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The majority of participants 82.7% (62/74) were 50 years or older, and 74% (56/74) had been treated for carcinoma of the endometrium. The mean age was 63.24 (SD 13) with a range of 28–82 years. Brachytherapy was the most common treatment modality with 95% (70/74) having a surgical procedure. 85% (63/74) underwent a surgical procedure and just 2.7% (2/74) respondents had radiotherapy treatment alone.

Table 1. Demographics

BT, brachytherapy; CX, chemotherapy; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; S, surgery.

Most respondents had received treatment for endometrial cancer compared to cervical cancer, 74.3% (55/74) versus 25.7% (19/74), respectively. A χReference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 test for independence (with Yates continuity correction) indicated a statistically significant difference in age between the two disease sites. x Reference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 (1, n = 75) = 33.1, p = 0.000, ϕ = 0.705. This reflects the difference in peak incidence of endometrial cancer and cervical cancer.

Vaginal dilator use

98.7% (74/75) of respondents (95% CI 92.8% to 99.8%) had been offered vaginal dilators during or after their radiotherapy treatment with 93.2% (69/74) choosing to use dilators (CI 85.1 to 97.1%). Table 2 shows the time at which participants began dilator use with 70.2% (52/74) using dilators within 3 weeks of completing treatment (CI 59.1 to 79.5%) and 10.8% (8/74) patients beginning use at least 5 weeks after treatment (CI 5.6 to 19.9%). Table 3 demonstrates the start times for the 8 respondents who selected ‘other’.

Table 3. ‘Other’ start times

Figure 1 shows how often patients used their dilators in the first 6 months. With 52.7% (39/74) using them three or more times a week (CI 41.5 to 63.7%) and 89.2% (66/74) using dilators twice or more a week and therefore achieving compliance (CI 80.1 to 94.4%).

Figure 1. Frequency of vaginal dilator use during the first 6 months.

The ‘other’ category was selected by eight patients and Table 4 demonstrates the ‘other’ frequencies recorded. For statistical analysis a new table was created to re-categorise dilator frequency to include responses recorded in the ‘other’ category.

Table 4. Table incorporating ‘other’ category for frequency for first 6 months

Compliance and influencing factors

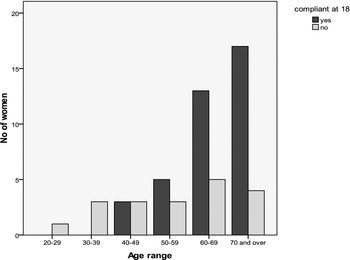

Figure 2 shows the number of compliant participants (using dilation two or more times per week) at 6 months against age.

Figure 2. Vaginal dilator compliance against age at 6 months.

It appears in this study that compliance at 6 months seems to be influenced by age (Table 5). The p-value of Fisher’s exact test (p = 0.029) does not tell us which age group is different, however, a simple trend can be seen in that six out of the eight cases of non-compliance occur in the youngest four age categories. This is in keeping with the p-value of the Mann–Whitney U test (p = 0.040) which suggests that age tends to be greater in the compliant group.

Table 5. Two-sided significance level for compliance at 6 months against age

Fisher’s exact test, two-sided significance level p = 0.029.

Mann–Whitney U test, exact 2 sided significance level p = 0.040.

Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney U test (Table 6) were carried out on vaginal irritation, vaginal discharge, and vaginal bleeding symptoms. It appears that vaginal dilator compliance at 6 months is not influenced by any of the reported vaginal symptoms.

Table 6. Fisher’s exact and Mann–Whitney U tests

RT, radiotherapy.

Fisher’s exact test was also performed for treatment received and type of cancer. Mann–Whitney tests were not performed on these variables since there were only two categories in each group (yes/no or cervix/endometrial).

It appears that the disease site does not influence compliance and the only treatment option that may be important in influencing compliance is brachytherapy. While this is not statistically significant at the 5% level, it does show a trend in this small sample size.

Compliance at 12, 18, and 24+ months

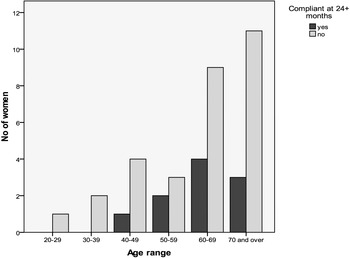

Dilator compliance was measured at 12, 18, and 24+ months. The number of participants within the study at each time point diminished due to lower numbers of women reaching the 12, 18, and 24-month follow-up period. Figures 3, 4, and 5 show compliance over the 12–24-month period against age.

Figure 3. Number of women compliant at 12 months. Total number of women included = 68.

Figure 4. Number of women compliant at 18 months. Total number of women included = 57.

Figure 5. Number of women compliant at 24+ months. Total number of women included = 40.

As follow-up time increases (Table 7) compliance is seen to decline, with only 25% (10/40) of women compliant at 24 months.

Table 7. Compliance 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 + months

DISCUSSION

Study limitations

The compliance estimation from this study is likely to be a biased over estimate of the true compliance rate. One hundred and sixty-four questionnaires were sent out and 75 (45.7%) returned. This is a low response rate, which is not altogether surprising considering the sensitive nature of the questions. Assuming that all those who did not respond were non-compliant users then a conservative estimation of vaginal dilator use is 40% (66/163) with a corresponding 95% CI of 35% to 50%. It is, however clear, that even using the conservative estimation of dilator use, women in this study were as compliant at 6 months as those randomised to intervention in previously published studies and demonstrated better compliance at 12, 18, and 24 months.

A better response rate may have been achieved using face to face interviews or if the questionnaire had been administered during a follow-up consultation. There were two reasons why this methodology was not used. First, conclusions from a study by Tourangeau and Yan found that participants may misreport or edit responses to questions of a sensitive nature, including sexual content, to avoid embarrassment in front of an interviewer.Reference Tourangeau and Yan20 Second, due to the small numbers of women still undergoing follow-up, it was felt that a greater cohort of patients would be available if those women who have been discharged were also included in the study.

Another limitation of this study is that compliance assessment was based on the participants self-reporting and it is, therefore, difficult to objectively verify the validity of the answers given.

Dilator compliance

Within the author’s centre vaginal dilation is recommended at a frequency of between two and three times per week while previous authors have defined compliance as dilating at least three times per week.Reference Robinson, Faris and Scott18,Reference Jeffries, Robinson, Craighead and Keats19 It is apparent from this, as with the previous studies, that compliance is much greater when defined as dilating two or more times a week compared with three or more times per week.

The results from this study have shown a significantly higher compliance rate at 6 months when compared to compliance in the non-intervention control groups in previously published studies. Jefferies et al.Reference Jeffries, Robinson, Craighead and Keats19 found that in the control group receiving written information alone, at 6 months, just 1/21 (4.7%) were using dilators three times a week and 4/21 (19%) twice weekly, compared to 43/74 (58%) dilating three times a week and 67/74 (91%) twice a week in this cohort of women.

A χReference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 goodness-of-fit test indicates there was a significant difference in the proportion of compliant women at 6 months identified in this study when compared with the previous study by Robinson et al., x Reference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 (1, n = 74) = 30.745, p < 0.000 when comparing the non-intervention group. When the test is repeated for the intervention group the discrepancy is smaller, however, the difference is still statistically significant. x Reference Stead, Fallowfield, Selby and Brown2 (1, n = 74) = 5.666, p < 0.017. For the purpose of this test, compliance was defined as three times a week to match that of the previously published study.

Robinson et al. found higher compliance rates than Jefferies et al. and Table 8 compares the results of all three studies based on compliance with vaginal dilation three times a week. It is interesting to observe that the mean ages for the two previously published studies are 42.9 and 46.5 years compared to 63.24 years in this study. One of the conclusions from the Robinson study was that in the absence of intervention compliance rates were higher in older women (41.5–73 years) when compared to younger women (28–41.5 years), 55.6% versus 5.6%. While in this study a statistically significant difference between age and compliance was observed, women under 42 years of age were compliant, and the eight patients who were non-compliant were found to be predominantly in the middling age group. If dilator use (and not compliance) is tabulated against age (Table 9) then it can be seen that all those who chose not to use vaginal dilators were also in the age range 40–59 years.

Table 8. Comparison of compliance between three studies against age

Table 9. Cross-tabulation of dilator use with age

This finding should be interpreted cautiously due to the small number of women in the younger age groups.

Of the five participants who opted not to use dilators at all, one ‘forgot to’ use them while the other four stated that they either ‘made me feel sick at the thought’, ‘did not appeal’, ‘did not like the feel of them’ or ‘could not get my head around them’. These women may have been sexually active but this was not explored in the scope of this study.

No statistically significant difference was seen when compliance was tested against vaginal symptoms or treatment modality. The treatment options delivered, however, were tested individually. It is well reported that there is a synergistic effect seen with multi-modality treatment and late effects of radiation treatmentReference Frykholm, Pahlman and Glimelius21,Reference Tan and Zahra22 and therefore it would be helpful to build a statistical model that would look at the interactions of different treatment combinations and whether there is an effect on dilator compliance. Due to the small data set used in this study such a model was not feasible. Robinson et al.Reference Robinson, Faris and Scott18 also concluded that compliance was independent of treatment modality, site of cancer, and hormonal status.

It is interesting to note that while compliance appears to be good at 6 months, much lower compliance rates are seen at 24 months, 89.2% (66/74) versus 25% (25/40).

This would suggest that a prospective, randomised study should be undertaken to evaluate the impact of intervention at 6 or 12 months post-treatment on the long-term compliance beyond 6 months. Jefferies et al.Reference Jeffries, Robinson, Craighead and Keats19 also found declining compliance with only 5/45% dilating at least once a week at 12 months and all had stopped by 18 months.

A key point relates to a lack of evidence supporting the frequency of dilator usage and further studies are needed to investigate the implications of frequency of use and the development of vaginal adhesions. If indeed vaginal dilation is effective when used two-three times a week, then evidence suggests that greater compliance rates will be achieved.

It appears that women within the authors centre are more compliant with vaginal dilator use than expected from the literature. One of the reasons for this finding may be due to the high profile given to feminine pelvic aftercare within the cancer centre. Women are routinely questioned about dilator activity at follow-up appointments which potentially could act as a trigger to continue use. Information regarding vaginal dilation is also delivered with an emphasis on facilitating adequate follow-up while sexual health is addressed in a holistic manner once the clinical, mechanical changes, and interventions have been discussed.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that compliance to vaginal dilators within the authors cancer centre is high at 6 months post-treatment when compared to previous studies. It is apparent that vaginal symptoms, disease site or treatment type do not have a significant influence on compliance. Age was the only single variable that had a statistically significant impact on vaginal dilator compliance. Dilator compliance appears to decline with time from completing treatment and this is a potential area for further investigation to identify interventions that may increase long-term compliance. However, there still remains a paucity of evidence surrounding the exact optimal use of vaginal dilators, particularly the frequency and length of time over which they need to be used. Further studies to investigate optimal use may provide a greater evidence base on which to instruct on the long-term need for vaginal dilator use.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr. Charlotte Coles, Rachel Kirby, Dr. Gill Whitfield, and Angela Duxbury for their comments and support. Funded by the College of Radiographers Industry Partner Scheme (CORIPS).