Introduction

Gamma Knife has long been considered the gold standard for radiosurgery of cranial lesions due to the high degree of accuracy of dose delivery. The model used at our clinic is a Gamma Knife Perfexion, which utilises 192 Co-60 sources divided into eight sectors each containing 24 sources.Reference Kendall, Ahmad and Algan 1 Each sector has four collimation options during treatment: 4 mm, 8 mm, 16 mm, and blocked, offering the ability to mix and match collimators so each shot is tailored to its use.

To maintain the highest standards of patient care, it is necessary for all practitioners within the radiation oncology group to continually assess current treatment methods against methods with new technology, weigh the pros and cons, and make a judgment on what is the best for patient treatment at their respective clinics. Due to advancements in processing power in recent years, it is now possible for computers to make more calculations per second than before. The increase in computing power allows us to introduce complexity in dose calculation algorithms to achieve dose calculations closer to reality. When these algorithms are introduced, they cannot be accepted solely based on theoretical advantage but must be rigorously tested to be trusted for patient care.

At our comprehensive cancer center, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is performed using a Leksell Gamma Knife Perfexion system made by Elekta (LGP, Elekta Instruments AB, Stockholm, Sweden) utilising the GammaPlan version 10 treatment planning system for treatment planning purposes. This treatment planning system offers two different dose calculation algorithms: the Tissue Maximum Ratio 10 (TMR10) algorithm and the convolution dose calculation algorithm. The primary difference between these algorithms is that the TMR10 algorithm models the skull and everything inside as having the exact same density of water, while the convolution algorithm uses Hounsfield units calculated from a computer tomography (CT) scan to find the varying electron densities of tissue and then take them into account during dose calculation.

The TMR10 algorithm replaces the TMR classic dose calculation algorithm released in GammaPlan version 10. 2 This algorithm is created using data from Monte Carlo calculations made with the Pegasos Monte Carlo system. The major advantage of the TMR10 algorithm over the TMR classic algorithm is that TMR10 has a more accurate geometrical model of cobalt sources and collimator channels within the Gamma Knife system, though it is expected that both algorithms produce similar results. Similar to the TMR classic algorithm, the TMR10 algorithm is a water-based dose calculation algorithm.

The convolution algorithm was released at the same time as the TMR10 algorithm. 3 It involves convolving the total energy released per unit mass (TERMA) with dose kernels pre-calculated by Pegasos Monte Carlo methods to describe the energy deposition within a volume of matter. Convolution algorithms are commonly used algorithms in radiotherapy, though the one within GammaPlan version 10 is heavily adapted to be specific to Gamma Knife by combining collapsed cone with pencil beam convolution methods along with ideas used in the TMR10 algorithm. The dose calculation is separated into two parts: dose from the primary scattered photons and dose from secondary or greater scattered photons. This algorithm takes into account tissue heterogeneities by scaling these kernels by the densities of tissue which are found through CT images.

These algorithms have been compared in previous studies.Reference Fallows, Wright, Harrold and Bownes 4 – Reference Xu, Bhatnagar and Bednarz 8 It was found that the convolution algorithm provided greater accuracy to films within a RANDO phantom to dose distributions than that with TMR10.Reference Fallows, Wright, Harrold and Bownes 4 This conclusion was supported by Nakazawa et al.,Reference Nakazawa, Komori, Shibamoto, Tsugawa, Mori and Kobayashi 5 who advocated the use of convolution algorithm to reduce dosimetric uncertainty. In another publication,Reference Osmancikova, Novotny, Solc and Pipek 6 it was found that convolution algorithm reduced 20% isodose volume by 5·3% when compared to the TMR10 algorithm. Another study revealed the convolution algorithm reducing dose to cochlea by 7% when compared to TMR10.Reference Rojas-villabona, Kitchen and Paddick 7 Treatment times were studied in one paper revealing an 8·4% larger average treatment times for identical prescriptions and shot arrangements when the convolution dose calculation was used compared to the TMR10 algorithm.Reference Xu, Bhatnagar and Bednarz 8

When implementing new dose calculation algorithms, special considerations must be given to the dose prescription. The traditional doses prescribed by radiation oncologists have been based on protocols using dose calculations where the entire scalp is treated as water. In this article, our goal is to compare the TMR10 and convolution algorithms used in Gamma Knife treatment planning to assess if the algorithms produce dosimetric differences large enough to have clinically significant outcomes.

Materials and Methods

For this IRB approved study, a total of 10 patients previously treated between 2007 and 2018 on the Leksell Gamma Knife 4C and Leksell Gamma Knife Perfexion systems were evaluated. Because the convolution algorithm requires knowledge of Hounsfield units, only patients who underwent CT scans as part of their treatment planning imaging were only eligible for this study. GammaPlan version 10 was used to generate all treatments. All patients were originally treated with the TMR10 algorithm. Prescription doses ranged from 16 to 22 Gy, prescribed to the 50% isodose line. A total of 5–36 shots were used to create each treatment plan. Identical shot placements, shot collimators, Gamma Knife 4C plug patterns and Gamma Knife Perfexion blocking patterns were used in plans calculated with both the TMR10 and convolution dose calculation algorithms. In addition, identical contour sets were used for plans calculated with TMR10 and convolution dose calculation algorithms. All patients had both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a CT performed before treatment with the head frame used for image registration during treatment planning. All structures other than the skull were contoured on the MRI contour set. At our clinic, we typically use spoiled gradient recalled-echo (SPGR) sequences to contour the optic nerves and chiasm, cochlea on T2 sequences and brainstem on either SPGR, T1 or T2 sequences. For our analysis, the skull volume was defined from the CT scan using auto-segmentation feature of the GammaPlan software and encompassed all tissues within the dose calculation volume. Prescribed doses were kept constant for both plans.

All dose volume histograms (DVHs) used in analysis were calculated by the treatment planning system. Structures analysed included the left and right cochlea, left and right optic nerve, optic chiasm, brainstem, skull and planning target volume. Minimum, mean, maximum and integral doses were used to compare treatment plans. The integral dose was taken by performing Simpson’s method of numerical integration through the Python programming language’s popular Scientific Python module. Maximum doses were taken from the DVH. For this study, mean dose was defined as the dose being received by 50% of maximum volume of structure. Minimum dose was taken as the maximum dose given to 100% of the examined structure. Each of these DVH parameters was then treated as a paired dataset between the TMR10 and convolution dose calculation algorithms to calculate statistical significance through the use of Student’s two-tailed t-test. All treatment plans were reviewed and approved by a single radiation oncologist.

Results

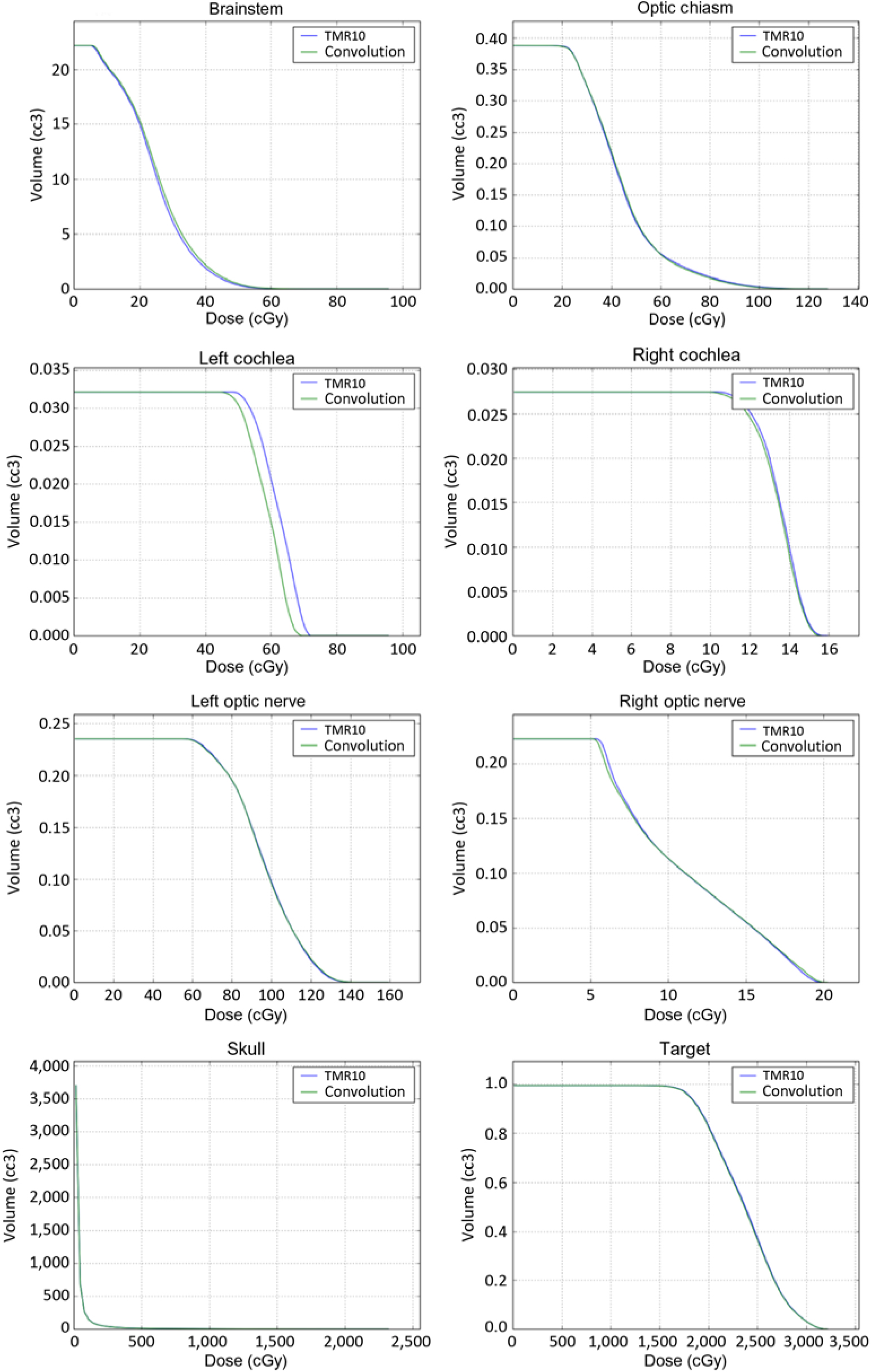

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. We analysed a total of ten patients, six males and four females with a median age of 63 years. Patient diseases included single brain metastasis, multiple brain metastases, arterial vascular malformation or meningioma. A typical DVH for each structure is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the primary differences between DVHs occurred in the tail of the DVH, but the DVHs did not vary significantly.

Figure 1. TMR10 and convolution DVHs for each critical structure from a typical patient.

Table 1. Patient characteristics for ten patients

The integral doses for the analysed structures are included in Table 2. For all structures, none of the statistical tests came out to be significant (p≥0·08). Additionally, for all the structures other than the brainstem and skull, the convolution algorithm gave a lower average integral dose when compared to that with the TMR10 algorithm.

Table 2. Average integral and average maximum doses (a) along with average mean and average minimum doses (b)

Average minimum, mean and maximum doses for structures are given in Table 2. The minimum average dose for the right cochlea was significantly smaller (p=0·04) when using the convolution algorithm (14·42 cGy) compared to the TMR10 algorithm (15·64 cGy). The difference in minimum dose was also statistically significant for the left cochlea (57·65 cGy vs. 53·73 cGy, p=0·05). For all critical organs other than cochlea, no statistically significant results were observed for minimum doses (p≥0·15), mean doses (p≥0·32) or maximum doses (p≥0·60).

Discussion

An accurate dose calculation when performing Gamma Knife radiosurgery depends on many factors. These include having accurate patient contours, the ability to characterise the radiation field of the treatment unit, the localisation between the imaging set and the head frame, and the algorithm selected for dose calculation. As computers increase in speed, it is natural to have increasingly complex dose calculation algorithms until a full Monte Carlo simulation is possible. The Convolution algorithm is a natural successor to the TMR10 algorithm, allowing the effects of heterogeneities to be accounted for. Due to the Gamma Knife system being used strictly for cranial treatments which is more uniform when compared to other treatment sites for radiotherapy and the time expense of taking an additional CT for each patient, adoption of the convolution algorithm has been slow. It is necessary to continually and critically assess every part of the patient treatment process and weigh the pros and cons of alternative techniques.

Switching from the TMR10 dose calculation algorithm to the convolution algorithm to calculate dose is not a simple change of algorithm but is accompanied by a change in workflow. An additional CT is added to the patient workflow in order to obtain Hounsfield units which are necessary to tissue heterogeneity corrections, but this does not replace the use of MRI which is necessary to segment soft tissues within the brain. A second major difference in workflow is how the patient’s skull is defined. When using solely MRI, bubble head measurements are performed and used to define the skull in 24 locations. When adding a CT, GammaPlan can auto segment the head based on the patient’s actual anatomy, creating a more accurate representation of the patient’s skull.

Our analysis did reveal subtle differences between the doses calculated by the TMR 10 algorithm and the convolution algorithm. When evaluating target coverage, the convolution algorithm resulted in a slightly lower calculated integral and minimum dose and a slightly higher calculated maximum and mean dose when compared to the TMR 10 algorithm. However, the magnitude of the differences in the calculated dose between the two algorithms was very small and essentially clinically insignificant. The differences between the two algorithms showed greater variations in the evaluation of the normal structures. In general, the convolution algorithm resulted in lower normal tissue doses when compared to the TMR 10 algorithm. This was especially true for the cochlea. This is likely related to multiple factors including the relatively small size of the cochlea as well as the fact that it is circumferentially surrounded by bone. Although this difference was statistically significant for the minimum doses received by the cochlea, the magnitude of the difference was still small, and essentially clinically not significant. The difference between the left and right cochlea likely related to the proximity of the target volume to one side compared to the other side.

Due to the small average differences found in our dosimetric comparison, authors recommend to use either the TMR10 algorithm or the convolution algorithm for dose calculation in Gamma Knife patients. Larger dose differences between algorithms were found when structures were close to the bone; therefore, authors also recommend that further study incorporating tumor proximity to the skull be investigated if convolution algorithm is necessary for a subset of Gamma Knife patients. These new studies could explain differences between results of our paper and previously referenced papers. For localisation, we found it more time efficient to perform localisation when using the MRI frame over the CT frame. Due to its increased complexity, the convolution algorithm took longer to perform dose calculations.

Conclusion

A comparison between our current treatment planning algorithm (TMR10) with the convolution algorithm was performed. No significant differences in DVH parameters were observed when results from Convolution algorithm were compared to that from the TMR10 algorithm. Thus we continue to use TMR algorithm for our patients in our clinic.

Acknowledgements

None.