In spite of American Indians' unique history, complicated relationship with the American government and the Caucasian population, and distinctive culture contemporary scholarship offers few scientific analyses of their engagement in American politics. In recent years, a number of analytic efforts examine the political orientations and participation of the growing Latino and Asian populations in the United States, and since the 1970s African-Americans have received frequent attention from social scientists.Footnote 1 National surveys have not allowed for rigorous empirical analysis of the political orientations and involvement of American Indians. This research pursues two goals. First, to begin to fill the gap in the discipline's understanding of the voter registration and political knowledge of Native Americans. Second, to determine if the concepts and theories employed to explain engagement in American politics provide analytic leverage when applied to American Indians. While a number of research efforts have focused on Native Americans' participation in reservation politics, empirical analyses of their involvement in American national, state, and local politics are rare.Footnote 2 Engagement in American politics may be distinct from involvement in tribal politics.

This research finds that American Indians exhibit lower rates of political knowledge of American politics compared to Caucasians, and register to vote at a rate lower than that of African-Americans and Caucasians but similar to that of Hispanics and Asians.Footnote 3 Similar to other marginalized populations, American Indians exhibit less political knowledge and lower voter registration rates after controlling for well-established causal variables. American Indians' attentiveness to American politics is similar to that evident among African-Americans and Hispanics, but less than that of Asians and Caucasians. While one would wish to see higher levels of political engagement among American Indians (as one would for all Americans), American Indian involvement in politics is far from dire, their levels of political knowledge and voter registration are only slightly less than that of the Caucasian population. This research also finds that military service elevates the political attentiveness and voter registration of American Indians, significantly more so than it does for Caucasians. As it does for other marginalized populations, military service appears to provide American Indians with resources that increase their political knowledge and voter registration. This finding is particularly noteworthy given American Indians' high rate of military service.

1. Political engagement

Why should we investigate the political engagement of American Indians? The health of a democracy depends on the engagement of its citizenry. Nearly all scholars maintain that citizen engagement enhances democracy (Barber Reference Barber1984; Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). With high levels of information attainment and political participation students of democracy can be more confident that citizens exercise their participatory rights in a manner that serves their interests as well as that for the nation considered collectively. Absent attentiveness to politics, citizens lack the information necessary to form substantive preferences on issues relevant to the nation as a whole or to themselves. Politically informed citizens are better able to participate in rational discourse. Moreover, to the extent less informed citizens are unable to articulate preferences, concerns, and interests that align with their own self-interest, they are unlikely to attain effective representation in the political process, an outcome likely to advantage better-informed citizens. Without political engagement, especially absent electoral participation, candidates for office have little reason to give much weight to citizens' preferences or concerns.

Scholarly concern for the involvement of minority populations is especially acute.Footnote 4 Minority populations hold lower levels of income and educational attainment, face discrimination when seeking employment and housing, and have few fellow co-ethnics occupying positions of authority in government.Footnote 5 As American Indians comprise a small proportion of the U.S. population compared to Caucasians, Hispanics, and African-Americans, there are theoretical reasons to believe political parties and interest groups direct weaker mobilization efforts toward them.Footnote 6 Several states' Voter ID laws prompted some commentators to accuse political elites of attempting to depress American Indian voter turnout. In 2018, American Indian tribes in ND accused Republican state officials of passing identification laws intended to suppress American Indian turnout (Astor Reference Astor2018). As minorities confront significant barriers to integration into the mainstream of society, one worries that limited political participation leads to diminished gains in income, educational attainment, and political standing.

Scholars posit that political engagement is a function of the costs associated with involvement, both with regard to the cognitive resources that facilitate the acquisition and integration of information as well as the availability and clarity of information provided by the political environment (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995; Leighley and Nagler Reference Leighley and Nagler2013).Footnote 7 Citizens with attributes that make learning from the political environment easier are in a better position to engage in the political process. For example, citizens with higher levels of educational attainment are better equipped to process information from the political world, and thus more likely to vote, follow politics, and talk about politics with friends (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). An individual's social environment may provide encouragement, or even pressure, for political involvement. A social environment that pressures an individual to participate provides a cost—experienced as guilt or regret—for failing to participate politically (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008). Greater incorporation into American society leads to adoption and internalization of norms that serve to encourage political engagement (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011). For American Indians, tribal leaders and the reservation itself may encourage and support their participation.

Scholars focusing on marginalized populations draw on each group's unique experience in the United States to understand variation in participation, demonstrating that marginalized groups' participation can come close to that of Caucasians in spite of lower levels of income and education. For example, Harris (Reference Harris1999) describes the key role played by churches for mobilizing African-Americans by providing support, pressure, and cues to African-Americans, thereby elevating their turnout beyond what one expects given their education and income attainment. McAdam (Reference McAdam1982) documents how churches, colleges, and other organizations have shaped protest activity by African-Americans. Scholars have also focused on the relevance of group identity and group consciousness for elevating minority political participation (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981). Other researchers documents how political threat mobilizes minority populations (Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003; Towler and Parker Reference Towler and Parker2018).

While the aforementioned factors can elevate turnout of marginalized populations research finds that their turnout remains below that of Caucasians, and that simply being a member of a marginalized population leads to lower involvement. Several scholars maintain that the fact that in only a few electoral contests will a minority population's vote make a difference for determining the outcome leads to lower turnout (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Leighley Reference Leighley2001; Fraga Reference Fraga2018). Members of minority populations will feel disempowered, and political elites will make little effort to mobilize them, leading to lower involvement even after controlling for well-established causal variables.

Citizens may practice a wide variety of activities that fall under the label of political engagement. These activities can vary in their legality, resource requirements (time, energy, cognitive, and monetary), social acceptance, and specificity of message, among other characteristics. While researchers have utilized numerous measures of political engagement (self-reported frequency of discussing politics, watching television news, attention to political campaigns, etc.) I concentrate on voter registration and knowledge of American politics. Elected officials and candidates who aspire to higher office have little reason to care about the concerns or preferences of citizens who frequently discuss politics or routinely read the newspaper. Matters are different when it comes to voters. Politicians should feel pressure to consider seriously the preferences and concerns of citizens registered to vote. This is especially relevant for American Indians, who have struggled to attain voting rights.

Political knowledge also deserves special priority over other measures of attentiveness to politics, especially those that rely on respondents' self-reports. While political knowledge as a measure of citizens' engagement is not without its weaknesses, it is probably the best measure for identifying chronic attentiveness to politics.Footnote 8 Citizens with high levels of political knowledge are more likely to organize their values, issues, and candidate preferences in a logical fashion; that is, they are more likely to construct candidate preferences in a manner consistent with their issue and value preferences (Bartels Reference Bartels1996; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2006). Self-reports of involvement are likely inflated by respondents' attempts to create a favorable impression of themselves. Additionally, a problem with some measures of political engagement is that citizens may differ in their interpretation of the stimuli presented in the survey question (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer1991).

2. Prior research on American Indian political engagement

Many inquiries on American Indians' political behavior and attitudes rely on surveys restricted to narrow geographical portions of the United States. Min and Savage (Reference Min and Savage2012; Reference Min and Savage2014) relied on a survey of Eastern OK to study American Indians partisanship, finding they are likely to identify as Democrats, vote for Democratic candidates, hold economically populist positions and be religiously conservative. Doherty (Reference Doherty1994) depended on aggregate-level data from seven states to examine American Indians partisanship.

Duffy (Reference Duffy1997) utilizes a survey from a small portion of the United States to examine American Indian patriotism, finding significant variation, with some Indians considering themselves tribal citizens only, but others holding a strong identity as U.S. citizens. Richards and Soherr-Hadwiger (Reference Richards and Soherr-Hadwiger1996) analyze aggregate data from small portions of the United States to determine that development of the American Indian gaming industry has resulted in an increase in campaign contributions, especially from middle-age respondents. More due to computational limits than sampling constraints, Peterson (Reference Peterson1997) utilized 1990 and 1992 Current Population data from seven states to model the turnout rates for American Indians, finding that simply self-identifying as an American Indian leads to lower turnout. While contributing to our understanding of American Indian political behavior, the unrepresentativeness of the samples employed by these scholars limits the generalizability of their findings.

Recently, a few scholars have utilized national surveys to examine American Indian political behavior and opinions. Relying on the U.S. Current Population Survey, Huyser et al. (Reference Huyser, Sanchez and Vargas2016) provide a rigorous empirical study of the voter registration of the American Indian population by comparing them to the Caucasian, Hispanic, and African-American populations. The CPS survey prompt asks respondents whether they were “not registered to vote due to a lack of interest,” not simply whether or not the respondent was registered. Surveyors permitted respondents to answer negatively if they were not registered to vote but for a reason other than a lack of interest. Individuals who did not register to vote but not due to a lack of interest are treated the same as respondents who claim to have registered to vote. Respondents may have not registered to vote due to a recent change in residence, to express dissatisfaction with national, state, or local politics, because they do not consider themselves U.S. citizens, because they did not know how to register to vote, or for some other reason. Huyser et al. find that marriage, education, and household size are important predictors of political participation. In addition to employing a different measure of voter registration, this research examines American Indians' political knowledge, and the role of military service for influencing political engagement. Other recent examples of scholarly research that utilizes national surveys to study American Indian political behavior and attitudes include Herrick (Reference Herrick2018) on the presence of the gender gap for partisanship (resembles the rest of the United States), and Koch (Reference Koch2016), who finds that American Indians disproportionately self-identify as Democrat and non-partisan.Footnote 9

3. American Indian sovereignty

There are several reasons to suspect American Indians will be less involved in American Politics even after one takes account of their lower levels of income and educational attainment. The U.S. Constitution, several U.S. court decisions, and numerous treaties affirm American Indian sovereignty. Some American Indians express a desire to maintain cultural distinctiveness, a characteristic that might reduce their integration into American society, and thus political involvement (Wilkins and Stark Reference Wilkins and Stark2018). Deloria (Reference Deloria1979) stresses that American Indian sovereignty not only implies jurisdiction over their affairs but also maintenance of cultural distinctiveness. Scholars cite the un-incorporation of Asians and Hispanics into American society as an explanation for their lower levels of political involvement (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011). Factors that enhance American Indian assimilation into mainstream American society, such as military service, may explain variation in their political engagement.

Issues relevant to American Indians bring them into conflict with federal, state, and local governments, motivating them to seek adjudication from state and federal courts on the interpretation of treaties signed by governments and Indian tribes (Evans Reference Evans2011). Relatedly, while the term “sovereignty” is often invoked to convey the relationship between American Indians and the U.S. government some believe usage of that term fails to capture the complexity of the relationship between American Indians and the non-Indian population, as well as federal, state, and local governments (Deloria Reference Deloria1979; Corntassel and Witmer Reference Corntassel and Witmer2008; Wilkins and Stark Reference Wilkins and Stark2018).Footnote 10 According to this point of view, American Indians recognize that they are not autonomous residents but dependent on the U.S. government and society for the provision of resources and protection. In recent decades, Indian tribes have lobbied federal, state, and local governments over the taxation of revenue generated from sales on reservations, disputes over land and water usage issues, and on the provision of infrastructure to support casinos (Witmer and Boehmke Reference Witmer and Boehmke2007; Evans Reference Evans2011). The mobilization efforts of political elites in the course of these battles may enhance American Indians' political participation. However, prior research on the political participation of marginalized populations claims engagement will be low even after one takes into account socio-economic characteristics due to political parties' weaker mobilization efforts stemming from the size of the marginalized population (Leighley Reference Leighley2001; Fraga Reference Fraga2018).

4. Military service, political knowledge, and voter registration

Citizens who served in the military vote and volunteer for community service at a higher rate than those who have not served (Ellison Reference Ellison1992; Leal Reference Leal1999 Reference Leal2003; Mettler Reference Mettler2005; Teigen Reference Teigen2006; Nesbit and Reingold Reference Nesbit and Reingold2011). The importance of military service for voter registration and political knowledge is especially pertinent in light of the high rate of service for American Indians relative to whites, African-Americans, Hispanics, and Asians (Holiday et al. Reference Holiday, Bell, Klein and Wells2006).Footnote 11 Additionally, researchers document that military service exerts a larger effect on the political involvement of marginalized populations (Leal Reference Leal1999; Parker Reference Parker2009). Scholars offer a variety of reasons as to why military service boosts political participation.Footnote 12 Military service provides training that enhances an individual's skill set, may elevate patriotism and one's sense of civic duty, each of which may then increase the likelihood of political participation. Military service may make participants more aware of the importance of government policy and politics.

Military service is preceded by military training, an intense, all-encompassing, demanding, and rigorous process that generally occurs when individuals are young adults, a point in the life-cycle when experiences powerfully shape attitudes and behaviors for years to come (Lovell and Stiehm Reference Lovell, Hicks Stiehm and Sigel1988). A key component of military training is team building, individuals learn to trust and serve their fellow soldiers, regardless of race, class, gender, religion, or any other demographic or personality difference. By instilling feelings of mutual trust, service, and protection within each individual, military training constructs cohesive, effective units with high morale. Military training aims to develop a belief in the importance of duty, honor, and loyalty to country (Lovell and Stiehm Reference Lovell, Hicks Stiehm and Sigel1988). These effects may be more consequential for individuals from marginalized communities as they are less incorporated into mainstream society. Leal's (Reference Leal1999) research found that the impact of military service on political participation is greater for Hispanics than for Caucasians, introducing the possibility that military service's influence on voter registration and political knowledge is greater for American Indians than Caucasians. Groups that are less incorporated into American society may benefit more from a training process that instills feelings of national identity, patriotism, and trust in fellow soldiers. Thus, I theorize that military service more powerfully increases the likelihood of voter registration and political knowledge for American Indians compared to Caucasians.

This research tests two hypotheses on the political involvement of American Indians.

Hypothesis 1 American Indians will exhibit lower less knowledge of American politics and voter registration compared to Caucasians even after taking account of other factors.

Hypothesis 2 Military service will exert a stronger effect on the political knowledge and voter registration rate of American Indians compared to Caucasians.

5. Data

A significant hurdle facing quantitative analysis of the political views and behaviors of the American Indian population is attaining samples of sufficient size to conduct rigorous, reliable analysis. The American National Election Studies has periodically over-sampled the African-American and Hispanic populations in the United States, providing scholars with sufficiently large samples for analysis. Additionally, surveys have been conducted on the African-American, Hispanic, and (less frequently) Asian populations of the United States, also allowing for the scientific analysis of their opinions and behaviors.Footnote 13 Unfortunately, scholars have been unable to assemble comparable samples for the study of the political behavior and attitudes of the American Indian population. The 2004 and 2008 National Annenberg Election Study (NAES) gathered large samples of the population of the 48 contiguous states.Footnote 14 Each year, NAES interviewed approximately 50–300 respondents daily from early January to the day before the presidential election. Combining the 2004 and 2008 surveys produces a sample of 139,389 respondents, 1,645 of whom self-identified as American Indian when asked to indicate their race.

The 2004 and 2008 NAES include a battery of survey items to measure citizens' political knowledge and voter registration. The NAES survey recorded respondents' answers to three questions to identify their political knowledge; combining the number of correct responses to these questions produces a four-point measure of political knowledge. Voter registration was attained by a simple question asking whether or not the respondent was registered to vote at the time of the interview. The NAES did not present every survey question to every respondent in 2004 and 2008; however, combining the two surveys provides a sufficient number of cases to permit reliable statistical analysis. Appendix A contains a complete listing of the variables used in this study, including question wording, recoding strategy, response values, and relative frequency values for each response. Appendix B contains a correlation matrix that includes all variables, and Appendix C is a table allowing for comparison of the proportion of Caucasians, African-Americans, Asians, and American Indians in the combined 2004 and 2008 NAES with the 2010 census. The NAES survey appears to over-sample Caucasians, and thus under-sample minority populations. For purposes of this research, I am primarily interested in differences between marginalized sub-populations, and comparing the American Indian population to the Caucasian population.

6. Voter registration and political knowledge: bivariate analysis

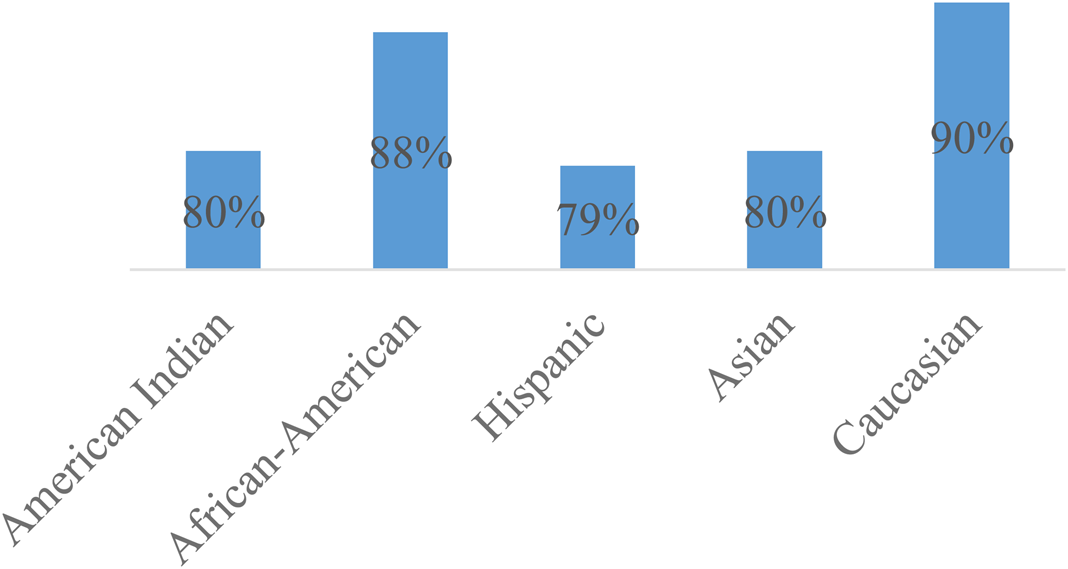

In order to place American Indians' voter registration and political knowledge in perspective I compare them to African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Caucasians. These results are presented in bar charts with means (for political knowledge) or proportions (for voter registration) in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Political knowledge (0–3). Note: χ2 for relationship between Indian/white and political knowledge = 126.52 (df = 3), significant at .05.

Figure 2. Registered to vote. Note: χ2 for relationship between Indian/white and registration = 92.74 (df = 1), significant at .05.

American Indians reveal lower levels of political knowledge and voter registration compared to Caucasians, the differences reach statistical significance at the .05 level or less (chi-square test). Generally, American Indians are involved in American politics at a rate equal to that of other minorities with the notable exceptions of the voter registration rate of African-Americans and the political knowledge of Asians. American Indians' voter registration rate is similar to that of Asians and Hispanics but lower than that of African-Americans and Caucasians. American Indians' political knowledge is similar to that held by Hispanics and African-Americans, but less than that of Asians and Caucasians. In fact, the mean for American Indians' political knowledge (1.50) is equivalent to the mean of the other four groups (1.57).

7. Multivariate analysis

A precise, rigorous estimate of the impact of being an American Indian on political knowledge and voter registration requires multivariate analysis. For estimation of these models dummy variables for respondent self-identified racial group membership (American Indian, Hispanic, African-American, and Asian) are included, Caucasian serves as the excluded category. Two of the minority populations (Hispanics and African-Americans) with whom American Indians are compared hold low levels of educational and income attainment, characteristics associated with skill development and social integration, and thus linked to engagement in American politics. Following the “cost model” of political engagement discussed earlier, in addition to educational and income attainment, measures of age, gender, union membership, military service, whether the respondent was born in the United States, and marital status are also included in the model to control for the effects of other determinants of political knowledge and voter registration. Prior research determines that women are less psychologically engaged in politics than men, married folks are more attentive to politics than single people, and that with increasing age comes increasing attentiveness to politics, each increasing the likelihood of political involvement (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Hansen1993; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Lehman Schlozman and Brady1995).

To estimate the influence of military service on political knowledge and voter registration two dummy variables are entered into the model, one for whether the respondent claims previous or current military service, another for whether the respondent's spouse indicates previous or current military service because what effects an individual may also impact one's spouse (Stoker and Jennings Reference Stoker and Jennings1995). Also included is a variable for whether the respondent lived in a 2004 or 2008 battleground state, as well as whether the respondent's state allowed citizens to register to vote on Election Day. Each of these variables should increase political knowledge and the likelihood of voter registration. While the analysis is, of course, limited to citizens, those born in the United States are likely to be more integrated into American society than individuals born abroad, and thus more likely to participate and follow the political process (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011). Although the dependent variables capture different aspects of political engagement, the same set of predictors are included to fully saturate each model. As the analysis is performed on the combined 2004 and 2008 NAES surveys, a dummy variable for respondents interviewed in 2008 is also included. Voter registration is a dichotomous variable, thus multivariate probit is the appropriate estimation technique. Political knowledge is an ordinal measure, requiring multivariate ordered probit. One-tail tests are employed as it is expected being an American Indians leads to lower rates of voter registration and political knowledge. Table 1 shows the results of the multivariate analysis.

Table 1. Determinants of political knowledge and voter registration

Note: Ordered probit coefficients are used for the model of political knowledge; probit coefficients estimated self-reported voter registration. Political knowledge is a four-point variable where 0 indicates the respondent could not answer any questions presented by the survey interviewer, and three indicates all questions were correctly answered. Standard errors are in parentheses. *Signifies significant at .05 level (one-tail test), **.01 level (one-tail test). Coefficients and standard errors for full model presented in on-line Appendix D.

Compared to Caucasians, being an American Indian contributes to lower levels of political knowledge and voter registration. Being African-American, Hispanic, or Asian also contributes to lower levels of political knowledge. Probably attesting to their politicized status within American politics and the mobilization efforts directed at them, being African-American leads to an increased likelihood of registering to vote, the only minority group with a positive coefficient. Black/white conflict in the United States is long standing, made salient repeatedly by candidates from both political parties and political commentators from both sides of the ideological divide, as well as by numerous interest groups. The politicization of their status leads to elevated turnout (Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Fraga Reference Fraga2018). Hispanics and Asians, many of whom are recent arrivals to the United States, and thus not fully incorporated into American society, reveal lower levels of political knowledge and voter registration in American politics compared to African-Americans and Caucasians, and similar to that evident for American Indians. These results confirm hypothesis 1: after taking account of standard explanatory variables, American Indians reveal lower levels of political knowledge and lower rates of voter registration than Caucasians.

Voting, of course, is a crucial form of participation, perhaps the most important, as it is the means for common citizens to exercise control over the direction of policy and hold elected officials accountable. If we set other variables to their means, being an American Indian reduces the likelihood an individual registers to vote by 3% compared to Caucasians. The effect is less than that for being Asian (5%), and larger than that for being Hispanic (2%). Being African-American leads to a 4% increase in the likelihood of registering to vote. Being an American Indian—after controlling for other covariates, each set to their mean—leads to a 6% reduction in the likelihood of answering all four political knowledge questions correctly compared to a Caucasian. The size of this reduction is equivalent to that evident for Asians (6%), and less than that for African-Americans (9%) and Hispanics (9%).

8. Military service

American Indians provide military service at a rate higher than that of the rest of the population (Holiday et al. Reference Holiday, Bell, Klein and Wells2006). According to the combined 2004/2008 NAES survey, 21% of American Indians either currently or previously served in the military. The corresponding percentages for whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians are 16, 14, 8, and 7%, respectively. Leal (Reference Leal1999) finds that military service exerts a larger impact on the political engagement of Hispanics than Caucasians; leading one to hypothesize that military service may influence political involvement more for American Indians compared to whites. A reasonable theoretical explanation is that Hispanics are less integrated into American society, and military service facilitates their incorporation. The same process may occur for American Indians.

Masuoka and Junn (Reference Masuoka and Junn2013) assert the need for a “comparative-relational” approach to estimate the impact of independent variables for explaining the preferences and behavior of marginalized populations. This approach allows for a separate intercept for each group, as well as placing the researcher in a better position to identify differences in the role of each causal variable for each group. Following this approach, I estimate separate models of voter registration and political knowledge for American Indians, whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians to determine if military service exercises unique effects for American Indians. These estimates are given in Tables 2 and 3. The large number of cases available allows for specification of a model with interaction terms that match each of the demographic predictors (education, income, marital status, etc.) with whether the respondent identified American Indian as his or her race. The results from the model with interaction terms, presented in on-line Appendix E, are substantively identical to those produced when separate analysis is performed for each group. As voter registration is a dichotomous measure probit is the appropriate analytic technique, for political knowledge ordered probit is employed. I concentrate on the results from the models given in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2. Determinants of political knowledge, by race

Note: Entries are ordered probit coefficients; standard errors are in parentheses. *Signifies significant at .05 level (one-tail test), **.01 level (one-tail test). Political knowledge is a four-point variable where 0 indicates the respondent could not answer any questions presented by the survey interviewer, and three indicates all questions were correctly answered.

Table 3. Models of voter registration, by race

Note: Entries are probit coefficients; standard errors are in parentheses. *Signifies significant at .05 level (one-tail test), **.01 level (one-tail test).

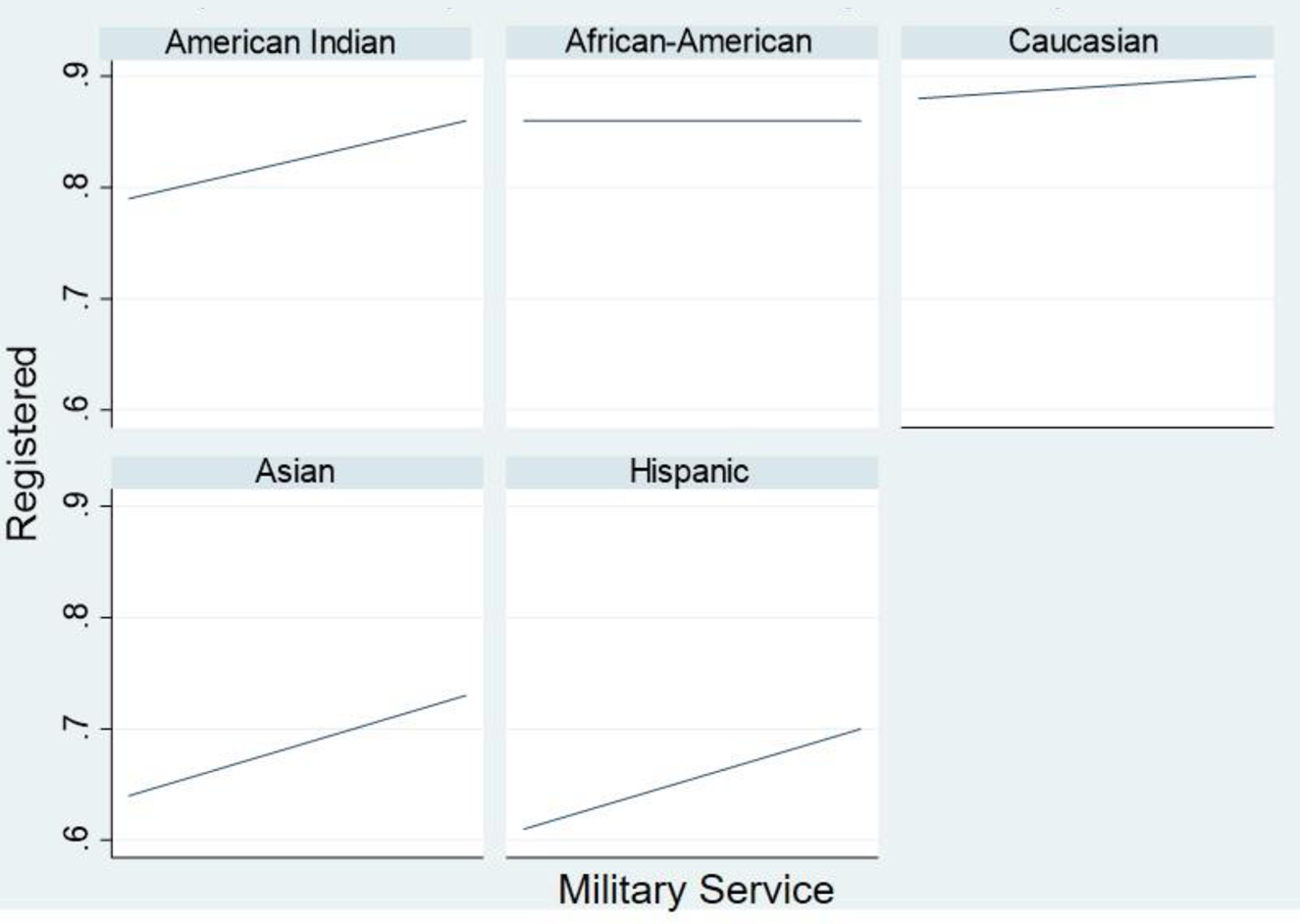

For political knowledge, the coefficient for military service for American Indians is considerably larger than that for other groups, double the size of the second largest coefficient (blacks), and four times larger than that for whites. The coefficients for military service for Hispanics and Asians fail to attain statistical significance; spousal military service does attain significance for Hispanics but not for whites or any other marginalized group. Military service significantly elevates the political knowledge of American Indians, exerting stronger effects for them than for any of the other groups. Military service increases the likelihood of voter registration for all groups with the exception of African-Americans. The effect is essentially the same for American Indians, Asians, and Hispanics; a statistically significant but small effect is present for whites. As African-Americans already have a fairly high rate of voter registration, military service may not be able to provide any benefit. For whites, already well-incorporated into mainstream society, military service does not elevate voter registration. For American Indians, military service enhances both political knowledge and the likelihood of voter registration, confirming hypothesis 2.

In Figures 3 and 4 graphs—derived from the estimates of Tables 2 and 3—illustrating the impact of military service for increasing the likelihood of answering correctly all three political knowledge questions as well as for the likelihood of registering to vote for American Indians, African-Americans, Caucasians, Asians, and Hispanics are shown. For American Indians, military service increases the probability of answering all three political knowledge items accurately by an additional 6%. The impact of military service on political knowledge for American Indians is equivalent to that for Hispanics and Asians, and considerably larger than that for whites and blacks. For African-Americans, no effect is evident. For whites, military service increases the chances an individual registered to vote by 2%. For American Indians, Hispanics, and Asians military service increases the likelihood of registration by an additional 7%. The registration rate for American Indians with military service is identical to that of whites, 88%.

Figure 3. Impact of military service on voter registration, by race. Note: Lines depict change in probability respondent registered to vote (Y axis) due to military service (X axis), by race.

Figure 4. Impact of military service on political knowledge, by race. Note: Lines depict change in probability respondent answers all political knowledge questions correctly (Y axis) due to military service (X axis), by race.

Parenthetically, note that the coefficient for age for registering to vote reaches statistical significance but is smaller than for any of the other groups (approximately half the size). An examination of the data in its bivariate form makes concrete that the difference in voter registration between younger Native Americans and the rest of the population is smaller than that between older Native Americans and the non-Indian population. For respondents aged 18–30, and those 31–40 years of age, there is a 3% difference in reported registration between Indians and non-Indians. The differences between Indians and Non-Indians for ages 41–50, 51–60, and 61 and above are larger: 9, 6, and 6%, respectively. Data limitations prevent a more rigorous analysis of this pattern. One can only speculate that younger American Indians may be establishing a voting habit at a rate that reduces the difference between their turnout compared to that of the non-Indian population.

The impact of military service on American Indians' political knowledge and voter registration is strong, consistent, and positive, elevating their likelihood of registering to vote more than it does for Caucasians and African-Americans. Military service also raises political knowledge significantly. There are strong theoretical reasons, supported by past research (Leal Reference Leal2003), that increases in feelings of patriotism and incorporation contribute to greater political engagement for marginalized populations.

9. Conclusion

American Indians exhibit a level of voter registration and political knowledge lower than that of the Caucasian population, but similar to that of the Hispanic and Asian populations in the United States. Compared to African-Americans, American Indians display a similar level of political knowledge but a lower level of voter registration. Relative to African-Americans, theoretical studies suggest Native Americans are not a target of major parties' mobilization efforts due to their small size. At least with regard to their registration rates and political knowledge, American Indians are as engaged in American politics as Hispanics and Asians, but less than African-Americans.

Prior theorizing on strategic mobilization suggests that American Indians draw weaker efforts from the American political parties as they constitute 1% of the U.S. population (Bartels Reference Bartels and Geer1998; Leighley Reference Leighley2001; Fraga Reference Fraga2018). However, perhaps an opportunity is present in states where American Indians constitute a larger proportion of the population for political parties to enhance their share of the electoral vote by making stronger efforts to link themselves to American Indians. Witmer (Reference Witmer, Kreider and Baladino2015) argues that it is valuable to identify the issues important to American Indians as candidates supporting these positions tend to do well among American Indians. To explore if America Indian voter registration was higher in states with larger proportions of American Indians, the multivariate models were re-estimated with measures of the proportion of each state's population included as independent variables. The coefficient for this variable did reach statistical significance in the model for voter registration, but the coefficient was negatively signed, supporting the assertion that a larger proportion of American Indians within a state leads to lower rates of voter registration. Perhaps in states with large American Indian populations American Indians maintain more distinct, separate communities. Most tellingly, the five states with the largest American Indian populations as a proportion of a state's population are heavily Republican (MT, ND, OK, SD, and WY), places where state-wide races are not competitive. Given American Indians disproportionately identify with the Democratic Party (Koch Reference Koch2016), some American Indians may see little to gain by voting in states where the Republican Party is dominant. As the Democratic Party has only a small chance of prevailing in states with high proportions of American Indians, they may lack the resources or motivation to generate robust mobilization efforts. Even with substantial American Indian turnout the Republican Party is likely to win state-wide contests in these states. Fraga (Reference Fraga2018) asserts that minority populations exhibit lower rates of turnout as they do not expect higher turnout to make a difference in most electoral contests. Alternatively, the lower rate of voter turnout in these states may result from successful demobilization efforts by the dominant Republican Party. As American Indians' level of educational attainment and income rises their turnout should improve (Johansen Reference Johansen, Kreider and Baladino2015).

American Indians resemble other minority populations in American politics in terms of lower rates of voter registration and attentiveness to American politics, with the notable exception of African-Americans, who demonstrate a higher rate of voter registration. This occurs even after taking account of the standard demographic variables that commonly explain engagement. This result is consistent with the argument that minority populations often believe their participation is unlikely to make much of a difference. Moreover, military service elevates the participation of American Indians as it does for other minority groups. Future research may investigate more thoroughly if there is a particular aspect of military training that influences the political engagement of minority populations. Researchers should also concentrate on other forms of national service that are commonly practiced by younger adults to determine if these activities also elevate political participation. Additionally, this research examined only two forms of political involvement. Future research should seek to determine if the findings presented here hold for other American Indians' involvement in other types of political engagement.

For many marginalized groups in America society, societal institutions elevate political engagement above what it would be otherwise if these citizens' participation depended solely on their levels of education and income, as well as their capacity to play the role of a pivotal group for determining election outcomes. For African-Americans, churches, historically black colleges, military service, and political organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League prompt higher levels of political participation. For Hispanics, military service and a variety of Hispanic organizations supply group members with the skills and orientations to increase their involvement in American politics. Military service plays a similar role for American Indians, elevating their voter registration and political knowledge above what it might be otherwise.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2020.43