The United States has witnessed a return of Islamophobia following the proliferation of ISIS and continued focus on Muslims as members of a religion that some say is not compatible with Western values. In Europe, anti-Muslim sentiment has been prominent for years (Strabac and Listhaug Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008), and is on the rise following the tragic Charlie Hebdo shooting. These events, even in different Western contexts, continue to feed into thinking that Islam and Western democratic values are incompatible despite the recent scholarly evidence arguing that mosque attendance encourages political participation in the United States (Ayers and Hofstetter Reference Ayers and Hofstetter2008; Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011; Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Oskooii Reference Oskooii2015) and in other Western contexts (Oskooii and Dana Reference Oskooii and Dana2017). Much of this sentiment is connected with the negative framing of Muslims and Islam in the U.S. news (Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2015).

Whether or not American Muslims vote and participate in politics, a strong sentiment prevails that religious Muslims and the Islamic faith tradition do not share the ideology and attitudes consistent with American democratic values. For example, the American Freedom Defense Initiative held a festival outside Dallas, TX in May 2015 encouraging participants to draw racialized cartoons of the prophet Mohammed as un-American. Sadly, when the event in TX ended in more violence with two Muslim men shooting a security guard outside the event in protest, event organizers, news media, and others concluded that Islamic teachings and traditions cannot support American values such as free speech. This viewpoint has seemingly grown more mainstream. Donald J. Trump, while the 2016 Republican presidential nominee, called for a complete ban on Muslims immigrating to the United States arguing that Islamic law “authorizes such atrocities as murder against non-believers who won't convert, beheadings and more unthinkable acts that pose great harm to Americans, especially women.”Footnote 1

Despite the politicization of Islam as radical and extreme and thus incompatible with American form of democratic ideals, scholars have demonstrated empirically that Islam, like other faith traditions in the United States, is often positively associated with greater levels civic engagement (Schoettmer Reference Schoettmer2015), political participation (Choi, Gasim, and Patterson Reference Choi, Gasim and Patterson2011; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2009; Read Reference Read2015), as well as a lower likelihood of supporting politically motivated violence (Acevedo and Chaudhary Reference Acevedo and Chaudhary2015). Looking at Muslims outside the United States, Dana (Reference Dana2017) points out that increased interactions, especially travel to the West and having relatives living in the West, allows for more positive feelings in the Arab world toward the West. Despite these contributions, we argue that two important gaps remain in this literature.

First, scholarly research needs a more complete measure of religiosity that captures the multiple dimensions of the concept. As Layman (Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001) points out, religiosity contains three distinct dimensions; belonging, behaving, and believing. For the most part, the empirical studies that currently exist do not capture each of the three dimensions of religiosity. Empirical studies of Muslims in the United States tend to focus primarily on the behaving dimension as captured by mosque attendance (Jamal Reference Jamal2005). Those that do have additional dimensions (e.g. Ayers Reference Ayers2007; Ayers and Hofstetter Reference Ayers and Hofstetter2008; Read Reference Read2015; Schoettmer Reference Schoettmer2015), do not sufficiently capture all three of the dimensions and tend to show inconsistent results between religiosity and measures of political integration. Thus, the literature here is often limited by not having the full panoply of religiosity variables for Muslims that we often ask of Christians in the United States.

A second gap is that the existing literature tends to measure only political participation (Jamal Reference Jamal2005), civic engagement (Read Reference Read2015; Schoettmer Reference Schoettmer2015), or political attitudes (Ayers Reference Ayers2007), and has overlooked the more theoretical question of whether religious Muslims believe their faith is consistent with American democratic values. While some have studied concepts such as political tolerance (Djupe and Calfano Reference Djupe and Calfano2012) or the use of politically motivated violence (Acevedo and Chaudhary Reference Acevedo and Chaudhary2015), we are not aware of any studies that empirically measure the conditions under which Muslim Americans think their religious beliefs are fully compatible with American democratic norms. Rather than trying to draw inferences, we address the issue head-on with a new, and direct question about views towards the compatibility of Islamic faith and American democratic values.

To provide insight into these important questions, we fielded a self-administered public opinion survey of Muslim Americans that contained multiple questions corresponding to Layman's (Reference Layman1997) conceptualization of religiosity and a new dependent variable to measure the ideological belief system of religious Muslims. We also measure non-electoral acts of political participation, which are not reliant on whether someone voted or not.

In short, we find that Muslims with higher levels of religiosity, across all three of Layman's dimensions, are more likely to believe the Islamic religious system and its teachings are compatible with American democratic principles. Further, we show empirical support that two out of the three dimensions (behaving and belonging) of religiosity positively associate with greater levels of non-electoral political participation. Despite the political rhetoric and continued marginalization and discrimination towards Muslims, the most religious followers of Islam in the United States feel a strong compatibility between Islamic teaching and U.S. democratic principles.

RELIGION, DEMOCRACY, AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

The relationships between religion, democratic principles, civic engagement, and political participation in the United States are well studied in political science, most notably Verba, Schlozman, and Brady (Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) and Putnam and Campbell (Reference Putnam and Campbell2010). Religion and religious practice more broadly is a sustaining and moderating factor for individualism and prosperity—key components for success in the American democratic system (Putnam and Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2010).

Much of the current research understands these connections through three distinct dimensions: belonging, belief, and behavior (Layman Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001; Olson and Warber Reference Olson and Warber2008). Belonging refers to identification with a particular faith (Layman Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001); belief suggests day-to-day guidance and interpretation of religious texts (Kelly and Morgan Reference Kelly and Morgan2008; McDaniel and Ellison Reference McDaniel and Ellison2008; Wilcox Reference Wilcox1986); and behaving relates acts such as church attendance, prayers, etc. (Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009; Kellstedt et al. Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth, Smidt, Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996; Smidt Reference Smidt2013; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2014).

Considered together, the “three B's” serve as an ideal measure of religiosity since they move beyond unitary measures that tend to offer incomplete accounts. This measure is informative because it captures much more than simple church attendance, self-reported religious belief, or denomination. Instead of focusing on any single dimension or assuming a single dimension is impervious to another dimension of religiosity, incorporating each of these three aspects together offers a more comprehensive and complete measure of religious enterprise and one that should be used across religious traditions. Because of these benefits, we seek to examine how these dimensions of religiosity impact key attitudinal and behavioral among Muslims in the United States.

In terms of “behavior,” the positive relationship between religious institution attendance and political engagement is prominent in the literature, for both White Americans and members of minority groups (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Cassel Reference Cassel1999; Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). These findings signal that religious institutions are not simply places of worship for the sake of worship, but rather communities that exert political and social influence. People who attend services (worship, prayer, etc.) are exposed to clergy and fellow participants whereas those who do not attend any type of service are not exposed. Exposure is not limited to only formal sanctioned activities, but also includes informal social events, such as coffee or tea with a fellow congregant (Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009).

The variation in engagement and faith traditions is generally explained through institutional differences (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). In one study, protestant churches offered more opportunities for member involvement, which facilitated the acquisition and development of certain skills and resources necessary to engage in the political system (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Djupe and Gilbert (Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009) extend this and suggest that formal and informal social networks influence behavior beyond church pews.

The sense of “Belonging” as a component of religiosity is also linked to civic engagement (Kellstedt et al. Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth, Smidt, Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996; Layman Reference Layman2001). According to Layman (Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001) belonging refers to affiliation or identification with a particular faith tradition. Central to the aspect of belonging is involvement, which can be defined as the extent of one's affiliation or identification. The extent of affiliation varies among studies; however, as Kellstedt et al. (Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth, Smidt, Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996) suggest, even negligible affiliation with a religious community is sufficient for a positive effect on political behaviors. Belonging also encompasses the idea of shared identification with others in your religious community, not just the direct belonging to your church, but the larger sense of common belonging and common identity with those of your same specific faith (Jeanrond Reference Jeanrond and Cornille2002; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2006).

Layman's (Reference Layman1997) third component of religiosity, “Believing,” also demonstrates a positive effect on civic engagement and political attitudes (Kellstedt et al. Reference Kellstedt, Green, Guth, Smidt, Green, Guth, Smidt and Kellstedt1996; Layman Reference Layman2001; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela2014). This component of religiosity relates to the incorporation of religious principles in one's daily life. This may include how much one relies on religious guidance from clergy or the sacred text in their daily life (Kelly and Morgan Reference Kelly and Morgan2008; McDaniel and Ellison Reference McDaniel and Ellison2008; Wilcox Reference Wilcox1986). In one analysis, Wilcox (Reference Wilcox1986) found a positive relationship between doctrinal fundamentalism and political participation. According to the study, those who applied dogmatic doctrines in their life participated at higher levels than those who followed formal doctrines less.

MUSLIM AMERICAN POLITICAL ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS

Given the ongoing debates about Muslim integration and Islam's compatibility with the American democratic process, we want to examine the conditions under which variation in levels of religiosity is associated with perceptions of compatibility and acts of political participation.

In terms of political participation, the link with Islam's has been well documented in the literature (Ayers and Hofstetter Reference Ayers and Hofstetter2008; Choi, Gasim, and Patterson Reference Choi, Gasim and Patterson2011; Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011; Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2009; Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Read Reference Read2007, Reference Read2015). However, existing studies of American Muslims tend to not incorporate the multi-dimensional concept of religiosity discussed above and how variation in religiosity associates with participatory acts.

Thus far, most scholarship has looked at single dimensions of religiosity in relation to participatory acts. For example, considerable attention has been paid to the role of mosque participation and attendance on one's civic and political engagement (Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011; Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Read Reference Read2015). Here, the connection is simple. The more Muslims attend Friday prayer services, the more likely they are to engage in the political system. Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii (Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011) find strong support between mosque attendance (behaving) and political engagement and Muslim integration into U.S. society.

Yet, Jamal (Reference Jamal2005) points out that frequency of mosque attendance likely promotes a perception of group consciousness, or the belief that what happens in one's life is connected to group as a whole. Unfortunately, Jamal (Reference Jamal2005) does not test this dimension of religiosity, which falls under the belonging dimensions of Layman's (Reference Layman2001) definition. While Jamal's early findings are critical in spurring this subfield, without additional variables measuring believing or belonging, we cannot be sure if it is the mosque itself, personal religiosity, or sense of belonging that drives political participation.

Muslims attend mosque for both spiritual and civic/community events. As Cesari (Reference Cesari2013) points out, mosque attendance alone may not be a sufficient measure for religiosity. If this is the case, we need to consider both the role of mosque attendance as a behavior in connection with perceptions of belonging to the group as well as measures of believing. According to Layman (Reference Layman2001) behaving and belonging are distinct dimensions and although they likely correlate, they cannot be substituted for one another.

Read (Reference Read2015) considers the relationship between subjective religious identity (believing), political religious identity, and organizational religious identity (behaving) and participation in civic activities of Arab Muslims in 2001 and 2004. Though she tests for two of the three dimensions of religiosity, believing and behaving, she only finds that organizational religiosity (behaving) is associated with increased civic participation across the entire sample, consistent with Jamal's (Reference Jamal2005) and Dana's, Barreto, and Oskooii (Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011) previous work. It is surprising that subjective religious identity (believing) was not associated with the outcome, though the data come from a post-9/11 environment when attitudes may have been in flux.

Related to religious identity (belonging), research by Oskooii (Reference Oskooii2015) suggests that perceived political discrimination can motivate political participation. He finds that American Muslims who perceive political discrimination targeted against them because of their religion, such as airport Transportation Security Administration racial profiling, are more likely to be politically active. While this is in part religious, Oskooii (Reference Oskooii2015) also controls for mosque attendance in his models, which he finds is a strong predictor of participation.

In terms of testing the attitudinal dimension of civic integration, that is the perception that Islam and American democratic values are compatible, less work has been done in this area. Acevedo and Chaudhary (Reference Acevedo and Chaudhary2015), for example, examine how religiosity impacts American Muslims’ attitudes toward suicide bombings. They suggest that religiosity is negatively associated with support for suicide bombings, yet only consider two of the three dimensions (believing and behaving). In their evidence, they show only the believing dimension, as measured by the respondent's perceived authoritativeness of the Qu'ran, is associated with a lower likelihood of supporting suicide bombings. Though informative and moving toward the direction of examining attitudes of Muslims, the authors note that there is already widespread disapproval of politically motivated violence in the sample. Further, only one of four “believing” variables is significant, the others are not only insignificant, but the direction of the coefficient is positive, suggesting that greater levels of believing could drive up support for politically motivated violence. Of course, we do not think this is the case, but rather wish to push back on Acevedo and Chaudhary (Reference Acevedo and Chaudhary2015) in two ways. First, as claimed above, religiosity is multi-dimensional and needs to be considered as such. Second, there are a number of reasons to expect that Muslims answering questions with serious criminal and legal implications are likely strongly biased towards legal and socially desirable outcomes. We think questions about political violence are extremely difficult to assess and rather the focus should be on broader questions about the degree of compatibility between Islamic faith and American democratic values.

Another set of studies focus on how individual level factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES), relate to political integration among American Muslims (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2009; Jamal Reference Jamal, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; Read Reference Read2007, Reference Read2015). Jalalzai (Reference Jalalzai2009) notes that participation has increased since 9/11 due to increasing interest in politics and suggests that age, education, and nativity are the primary drivers for participation, much like we see in the general U.S. population. Looking for evidence that religion and religiosity impact Muslims’ participation, a number of studies were unable to find direct support in their analysis (Jamal Reference Jamal, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; Read Reference Read2007). Instead, like Jalalzai (Reference Jalalzai2009), Jamal (Reference Jamal, Wolfe and Katznelson2010), and Read (Reference Read2007) suggest standard SES indicators are the strongest and readily available determinants of participation among Muslims. Read (Reference Read2007) suggests that high rates of participation relate to Arab Muslims’ relatively high socioeconomic positions, but also points out that Arab women also enjoy relatively high levels of political engagement.

Of course, SES factors are important correlates for participation, but these tell us little about the underlying attitudes Muslims possesses regarding religiosity and thus, are poor measures to examine the extent of participation among the U.S. Muslim population.

To fill these voids, we test the conditions under which variation in religiosity based on the Layman's (Reference Layman2001) multi-dimensional concept accounts for perceptions of compatibility and acts of political participation. By focusing on the “Three B's”: Believing, Behaving, Belonging, we are able to provide a more complete picture of the relationship between Islam and its followers and American democratic principles as well as participation within the U.S. political system.

While we think there are many similarities across most religions and most religious followers in the United States, scholars such as Swaine (Reference Swaine1996; Reference Swaine2001) have pointed out that some religious traditions, such as Quakers and Amish may appear to withdraw from mainstream American society as they practice their faith. Skeptics and critics of Islam believe its teachings and principles are not compatible with American values. Thus, in the next section, we outline arguments why the mythic “class of civilizations” thesis that scholar such as Huntington (Reference Huntington1996) and Lewis (Reference Lewis1990) had predicted are unlikely. In fact, we predict that the most religious Muslims are those with the strongest perceptions of compatibility and the most likely to participate in the U.S. system. In the next section, we outline a set of theoretical augments regarding why Muslim's with the highest level of religiosity should be the most likely to perceive compatibility and engage directly by participating in the U.S. system.

WHY MUSLIM RELIGIOSITY ENCOURAGES INTEGRATION IN THE UNITED STATES

Those with a high sense of religiosity are likely to have a close and personal connection to Islam (Steenbrink Reference Steenbrink1990). Tadayyun (Arabic for “religiosity”), is often equated with the degree of devoutness and practice of Islam. Those with a high sense of tadayyun are likely to be the most familiar with Hadith, most often read the Qu'ran, regularly attend prayer services at the mosque, and have a strong sense of shared community with other Muslims. Tadayyun maps on directly to multi-dimensional concept of religiosity from Layman (Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001) that suggests it is necessary to explore the connection between Islam and attitudes towards democratic values.

We argue that religiosity and Islam are linked with a sense of respect for the codes and values of non-Muslim societies. Why? Because the Qu'ran, Hadith, and the Prophet Mohammad ask Muslims to uphold the social contracts of non-Muslim societies, so long as they are free to practice their religion. In the United States, a country with little to no governmental prohibitions on religious expression or practice, Islam suggests political incorporation is an acceptable, if not desirable outcome. Our argument builds heavily on existing research by March (Reference March2006; Reference March2007).

March acknowledges that a cursory review of Islamic texts will reveal “prohibitions on submitting to the authority of non-Muslims states, serving in their armies, contributing to their strength or welfare, participating in their political systems,” (Reference March2007, 236). However, such a conclusion would not be based on a comprehensive review of Islamic doctrines, nor would it be based on an in-depth understanding of how Islam is interpreted and practiced by the most devout. In contrast, March argues that “even pre-modern Islamic legal discourses affirm a certain set of values and principles… chief among these is the insistence within Islamic jurisprudence on the inviolability of contracts,” (236), and he provides the example of the American social contract.

Many Muslim jurists and texts clearly state that it is reasonable for Muslims to reside in non-Muslims societies so long as the non-Muslim society does not prevent the manifesting of Islam (Abdul Rauf Reference Abdul Rauf2004; March Reference March2007). Through an extensive review of Islamic texts, March concludes that “not only is it permitted to reside in a non-Muslim polity, but also it is permitted to do so while being subject to and obeying non-Muslim law,” (Reference March2007, 243). This obligation is rooted in a religious following of the spirit and letter of Islam. Among Muslims living in the United States, we should expect then, the most religiously devout, those with a high degree of Tadayyun, to support and affirm the American social contract and thus possesses high levels of civic engagement. In other words, religiosity may encourage Muslims to support the political system in the United States.

Therefore, our argument rests on the notion that the Muslim who is more knowledgeable of Islam, the Muslim who reads the Qu'ran, the Muslim who knows the stories of the Prophets, the Muslim who attends mosque, and the Muslim who feels they are connected with and have a lot in common with other Muslims is more likely to reject conflict-based theories and sensational components of Islam and instead embrace the full context of Islam, which allows for Muslims to uphold laws, practices, and values of their host society (Abdul Rauf Reference Abdul Rauf2004) as well as participate in the political processes. March argues that those with an in-depth knowledge, belief in, and understanding of Islam will frequently cite the story of Prophet Yusuf who served as an appointed minister to the non-Muslim Pharaoh of Egypt as support for compatibility. March cites a statement by al-Shanqiti as evidence, “there is nothing prohibited in Muslims’ participating in elections run in non-Muslim countries, especially when such participation accrues benefits to Muslims or wards off harm” (Reference al-Shanqiti2006). More than not prohibiting political incorporation, some argue that the more religious Muslims would understand they have a duty to support the political system in the United States, and to participate themselves in order to show care for others, as well as to help improve the position of Muslims in society (Ali Reference Ali2004; al-Shanqiti Reference al-Shanqiti2003). To sum, religious scholars, political philosophers, as well as non-empirical and empirical investigations demonstrate no apparent disagreement between Islam and Western democratic practices, Muslims living in non-Islamic states, and Muslim participation in non-Islamic political practices.

As March and other Islamic thinkers have pointed out, there is a strong precedent embedded in Islamic teachings to participate and incorporate into non-Islamic societies. In terms of empirical support for incorporation, Bilici (Reference Bilici2011) provides a typology to explain how Muslims integrate into the U.S. polity.

Our review of the literature provides theoretical support that the most religious Muslims should be those most likely to perceive compatibility between Islam and U.S. democratic values. They also should be more likely to participate within the U.S. system. We theorize that Islam is not unlike other religious traditions in the United States. Like many other faith traditions, we think Islam encourages integration, good citizenship, being a good community member, and positively relates to outcomes such as civic engagement and political participation (Espenshade and Ramakrishnan Reference Espenshade and Ramakrishnan2001; Hochschild and Mollenkopf Reference Hochschild and Mollenkopf2010). Yet, given the politicization of Islam and the rise of Islamophobia, Muslims and the Islamic tradition have been equated as religious outsiders, incapable of being a part of the U.S. polity. We aim to provide a more complete picture of the relationship between Islam and the United States, one that is as old as the United States (Dana and Franklin Reference Dana, Franklin, Pintak and Franklin's2013). To accomplish this, we measure an important attitudinal dimension needed in the research as well as utilize a more sophisticated measure of religiosity to show precisely how religiosity relates to perceptions of compatibly and political participation. We construct our hypotheses around each of Layman's religiosity dimensions.

H1: American Muslims with higher religious guidance and knowledge of Islam (believing) are more likely to think Islamic teachings are compatible with American democratic values and are more likely to participate.

H2: American Muslims with higher mosque involvement and those who practice Sadakah (behaving) are more likely to think Islamic teachings are compatible with American democratic values and are more likely to participate.

H3: American Muslims with higher shared commonality with fellow Muslims (belonging) are more likely to think Islamic teachings are compatible with American democratic values and are more likely to participate.

We are attempting to explain under what conditions Muslims in the United States believe Islamic teachings encourage integration into the American democratic system as well as participate in the political process. We suggest a model of political incorporation and participation that goes beyond just attending Mosque service. Like other faith traditions, attendance is one ingredient necessary for political behaviors and perceptions of compatibility. We theorize that those who demonstrate high levels of religiosity across all three dimensions are most likely to perceive that their faith tradition is fully compatible with American democratic principles and participate in meaningful ways.

DATA AND METHODS

To address the issue of attitudinal compatibility between Islam and political incorporation in the United States, we implemented a unique public opinion survey of Muslim Americans. Scholars familiar with the study of Muslim Americans as well as racial and ethnic politics know well that little empirical data exists regarding Muslims in the United States. Among the MAPS/Zogby polls and Pew Research Center polls that do exist, none contained the precise questions we are interested in analyzing—the belief among Muslims that Islamic teachings are consistent with the American democratic values. Thus, we fielded an original survey of Muslims Americans in 22 locations across the United States. The sample represents a diverse cross-section of American cities and the Muslim population, including interview sites in the East, West, and Midwest, as well as the major Muslim population centers in the United States. Our sample includes large numbers of Arab, Asian, and (U.S. born) African American Muslim respondents, making it quite representative of the overall U.S. Muslim population, which contains great diversity (Dana Reference Dana2011).

One significant advantage that our survey has over previous efforts is that respondents were recruited face-to-face, and subjects then self-administered the survey. Research assistantsFootnote 2 handed out clipboards to participants who completed the survey in their own privacy. Giving the concerns in the American Muslim community over surveillance, telephone surveys may introduce considerable social acquiescence and social desirability bias. Considerable research has demonstrated that attitudes on sensitive topics are more truthfully given in private self-administered surveys (Krysan Reference Krysan1998), and that minorities are likely to moderate their attitudes when being interviewed by non-whites, the typical method in telephone surveys (Davis Reference Davis1997; Krysan and Couper Reference Krysan and Couper2003).

Participants were selected using a traditional skip pattern to randomize recruitment and could chose to answer the survey in English, Arabic, or Farsi. Naturally, drawing a sample of Muslims in the United States is not easy or efficient given their relatively small population. To address this concern, the survey was implemented at 22 randomly selected locations across 11 U.S. cities. Interviews were gathered at a mix of religious and non-religious locations from Islamic community centers to festivals at a city's downtown convention center.Footnote 3 In total, 1,410 surveys were completed across the 11 locations, and the demographics of our sample closely match those reported in a recent Pew survey of Muslim AmericansFootnote 4 (see Appendix for sample characteristics).

Given that our sample is drawn in part from religious centers and community festivals, the reader may question if there is any inherent bias. We are confident in our sample selection for two specific reasons. First, our sample still demonstrates a range of religious diversity. While attending the mosque and the prayer of Eid are descriptively religious practices, they are also cultural and social practices, just as attending Sunday church services or Easter Mass are both religious and cultural events for Christian and Catholic Americans. In response to a question about the importance of religion in their daily life, 50% stated religion was very important, 38% stated it was somewhat important, and 12% stated not too important. Likewise, when asked how involved they were with their local mosque, 26% said very active, 40% said somewhat, 20% said not much, and 13% said not at all active. Given the variation on these two key variables, we are quite confident that our sample provides the appropriate mix of religiously oriented Muslims, and at the same time providing a spectrum of religiosity that ranges from very low to very high. Second, we are actually interested in the more religious Muslim population, given the nature of our research question. Scholars, pundits, and journalists who state that Islam is not compatible often point to the more orthodox segment of the Islamic population as the source of tension. Thus, it is important that we sample the Muslim population in the United States that continues to practice their religion, as opposed to a sample that is predominantly secularized.

Dependent Variable

To assess political incorporation among Muslim Americans we examine both theoretical and applied measures. First, we ask respondents to rate the compatibility between Islam and the American democrat system. We asked respondents, “As a Muslim living in the U.S., do you think Islamic teachings are compatible with participation in the American political system?” and the possible answer choices were: yes, very much / yes, somewhat / only a little / not at all. Overall, 34% answered very much, 32% somewhat, 21% only a little, and 13% not at all. Second, we asked whether they engaged in political participation: “During 2006, did you participate in any of these activities? Community meeting / Rally or protest / Write letter to public official / Donation to political candidate or campaign / Vote in November 2006 election.” Based on their yes/no answer to these questions we created an index of political participation. About one-fourth of our sample stated they were not citizens, so we excluded voting, resulting in a four-item index that ranged from 0–4.Footnote 5 The index has a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of .7117. Ordered logit regression is used and standard errors are clustered at the state level.

Independent Variables

The key independent variables that we are interested in revolve around the degree of religiosity among our Muslim respondents. Since we measure religiosity using Layman's (Reference Layman1997; Reference Layman2001) “believing,” “behaving,” “belonging,” participants in the survey were asked about religious guidance or the extent to which they followed the Quran and Hadith in their daily lives (believing), know Islam or whether the respondent knew a factual question about months in the Islamic calendar (believing), mosque attendance or the level of participation in Mosque-related activities and religious alms-giving (behaving), practice Sadakah or whether the respondent engaged in the practice of Sadakah in the past (behaving), Sunni whether the respondent identified as Sunni (belonging),Footnote 6 and Muslim commonality or the level of commonality degree and whether or not they felt their fate is connected to other Muslims in the United States (belonging). We are confident that the measures of religiosity we present here among American Muslims are consistent with the broader scholarship on religion and politics and provide a mechanism to test our hypotheses. More importantly, we believe that these measures fully consider all the dimensions of religiosity as well as add the attitudinal component of belonging that has been frequently identified, but not empirically verified in much of the previous literature (Jamal Reference Jamal2005; Read Reference Read2007).

While our main focus is on these six religiosity variables, we also include many standard demographic and expected control variables. Since perceived discrimination is particularly relevant among racial and ethnic minority groups, we include a variable, airport discrimination, for whether respondents believe airport security measures are targeted towards Muslims (1), or to all American equally (0). Next we include a series of demographic dummy variables for whether the respondent is Black or Asian (Arab is the comparison group), Sunni Muslim, foreign born, a U.S. citizen, and if they speak mostly English at home. Finally, we include many standard predictors of political participation such as age, income, education, gender, news consumption, and length of time in the community (see Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

FINDINGS

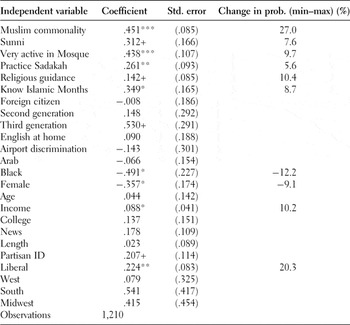

In Table 1 we present results for the regression estimating support for the idea that Islamic teachings are compatible with the values of American democracy. In addition to the ordered logit coefficients, which are quite difficult to interpret on their own, we report changes in predicted probability for significant variables to better assess the impact that each independent variable has on the outcome.

Table 1. Is Islam compatible with participation in American democracy? Ordered logit regression results and changes in predicted probability

Note: +p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Standard Errors in parentheses.

The results in Table 1 suggest that each dimension of religiosity is positively related to the belief that Islam is compatible with the democratic values of the American political system.

In terms of believing (Hypothesis 1), we find that Muslim Americans with a high degree of religious guidance in their personal lives to be significantly (p < .10) more likely to view the teachings of Islam as compatible with participation in American democracy. In fact, Muslims who state that they follow the Qu'ran and Hadith “very much” in their daily lives are 10.4% more likely to support political participation in America compared with Muslims who stated religion plays no role in their daily life. The second believing variable, know Islam, also has a positive and significant (p < .05) association with attitudes towards compatibility. Muslims who are more knowledgeable about Islam are 8.7% more likely to perceive compatibility between the two systems.

Next, we examine the role of behaving as measured by mosque attendance and the practice of Sadakah (Hypothesis 2) on perceptions of commonality. American Muslims who are very involved in the activities of the mosque are significantly (p < .001) more likely to believe Islam is compatible. In fact, the most active Muslims in our sample are 9.7% more likely to believe in compatibility. Practicing Sadakah is associated with a 5.6% and statistically significant (p < .01) increase in the likelihood of believing Islam is compatible with participation in the American democratic system.

In terms of belonging as measured by perceptions of Muslims’ commonality with one another as well as whether respondent is Sunni (Hypothesis 3), Muslims who feel they have very much in common with other Muslims are 27.0% more likely (p < .001) to support the compatibility thesis than those who thought Muslims had nothing in common with one another. Identifying as Sunni is positively and significantly (p < .10) associated with perceptions of compatibility. Those who identify as Sunni are 7.6% more likely to perceive compatibility than those are not Sunni, all else equal.

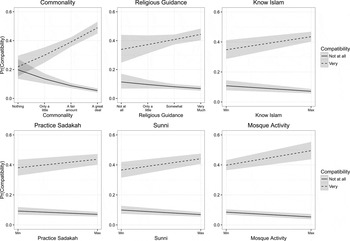

Figure 1 visualizes the association between each independent variable and perceptions of compatibility. As the figure shows, each of the key independent variables are positively associated with an increase in the probability of believing that Islam is compatible with American democratic values. The dashed line shows the probability that a respondent strongly supports compatibility between the two systems whereas the solid lines show the predicted probabilities that a respondent does not perceive compatibility between Islam and U.S. democratic values. As the values of each variable increase from the minimum to maximum, the probability that a respondent supports compatibility is positive across each of the variables as indicated by the dashed line. As the solid lines show, feelings of incompatibility are less likely under conditions where the religiosity variables are highest.

Figure 1. Predicted perceptions of compatibility between Islam and American Democratic Ideals for key explanatory variables.

While each of these independent variables has an effect on their own, all else equal, in reality they likely do not operate in insolation. In Figure 2 we show how changes in each variable simultaneously are associated with changes in the probability of support for commonality. We begin by estimating the probability that a respondent thinks the teachings of Islam are very much compatible with American democratic principles, assuming the minimum response to each of the six religiosity questions. As the left panel of Figure 2 shows, a respondent in this condition has a probability of .07 of perceiving strong compatibility between the two systems. When the religiosity variables are moved to their highest value, the respondent has a predicted probability of .63 of believing that Islam is very compatible with the U.S. system.Footnote 7 This change in the level of religiosity corresponds to a .53-point change in probability in perceiving that the two systems are very much compatible. In the right panel of Figure 2, we show the relationship between religiosity and feelings that Islam is not compatible. Respondents with the lowest level of religiosity have a probability of .45 of perceiving that Islam is not compatible. Among those with the highest level of religiosity, the probability of thinking Islam is not compatible drops to .024. A change from the minimum value of religiosity to the highest level is associated with a .42 drop in probability of perceiving that Islam and the United States are incompatible. American Muslim respondents with low levels of religiosity are much more likely to believe U.S. democratic ideals and Islam are incompatible and those with the highest level of religiosity are much more likely to believe in compatibility.

Figure 2. Predicted perception of compatibility between Islam and American Democratic Ideals given changes in degree of religiosity.

Religiosity and Political Participation

The results presented in Table 1 are important because they examine the extent to which Muslims support the idea of political participation in the United States. To complement the analysis and to provide a more complete picture the relationship between the three dimensions of religiosity and political incorporation, we now present a set of findings regarding the connection between religiosity and political participation.

As many scholars of immigrant politics have concluded, electoral forms of political participation are not always informative among Asian Americans (Lien, Conway, and Wong Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2004) and Latinos (Barreto and Muñoz Reference Barreto and Muñoz2003). Likewise, in her study of Muslim political engagement in New York City, Jamal (Reference Jamal2005) notes that due to a large foreign-born and non-citizen population, voting is not the best measure of Muslim political participation. Similar to Jamal (Reference Jamal2005),Footnote 8 we limit our political participation variable to four meaningful non-electoral acts: during 2006 did you attend a (1) community meeting; (2) rally or protest; (3) write letter to a public official; or (4) donate to a political candidate or campaign. This measure has good variation for both foreign and native-born Muslims.Footnote 9 We create a count variable ranging from 0 to 4 and rely on Poisson regression to estimate the event-count model (Cameron and Trivedi Reference Cameron and Trivedi1998).

Turning to the regression results, there is consistency between Tables 1 and 2. First, among the six religiosity variables, we find that three exert a positive and significant influence on political participation and that two of the three dimensions of religiosity positively impact political participation. The variables Muslim commonality (belong), mosque involvement (behave), and practice Sadakah (behave) are all positively and significantly associated with political participation. Our finding for mosque involvement mirrors that of Jamal's (Reference Jamal2005) New York City study as well as Dana, Barreto, and Oskooii (Reference Dana, Barreto and Oskooii2011) who rely on a national sample of Muslims. Muslims who are very involved in their mosque are about 51.5% more likely to participate compared with those who are not at all involved. Those who practice Sadakah are 51.2% more likely to participate. With respect to Muslim commonality, we find those who think Muslims have a great deal in common with each other to be 34.1% more likely to participate, a finding similar to Latino participation and group identity by Sanchez (Reference Sanchez2006).

Table 2. Religiosity and Muslim American Political Participation Poisson regression results and changes in predicted probabilities

Note: +p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Standard Errors in parentheses.

However, not all of our religiosity variables have a positive relationship with political participation. Interestingly, religious guidance and know Islam, both measuring the believing dimension, which has a positive effect on feeling Islam to be compatible with American democratic principles, has a negative impact on measured political participation. We also see that the variable Sunni has a significant and negative influence on political participation. What explains such a discrepancy? Though we delve into this more in during the discussion and conclusion, as suggested by March (Reference March2006; Reference March2007; Reference March2011) and Abdul Rauf (Reference Abdul Rauf2004), the teachings of Islam do not necessarily compel political participation, rather they permit it. Actual participation is left up to the respondent to choose what is right for themselves. In other words, Islam permits participation, but does not require it. Looking at the other three key independent variables; however, we can still conclude that increased religiosity among Muslims leads to greater political participation in the United States.

As we did with Model 1, we examine the impact of each religiosity variable on the predicted number of electoral acts. In Figure 3, we see that not all the religiosity variables impact the number of predicted acts among Muslims in our sample. Consistent with Table 2, commonalty, mosque attendance, and practice of Saddakah are positively related to increased number of political acts. Muslims in the sample with the lowest level perception of commonality are predicted to engage in less than one act (.88) whereas those who perceive the most commonality are predicted to engage in 1.22 acts, a nearly 50% increase. Similarly, mosque attendance also has nearly 50% increase in the number of predicted acts of participation simply by moving from the lowest level of mosque attendance to the highest level. Finally, practicing Saddakah is associated with almost a 75% increase in the number predicted acts. Low levels are associated with 79 number of acts and high levels are associated with 1.31 political acts.

Figure 3. Predicted number of political acts given changes in key independent variables.

Next, looking at the immigrant-based variables in Table 2, we show that as compared with foreign-born non-citizens, foreign-born naturalized citizens are significantly more likely to engage in political participation in the United States. Second and third generation U.S. born Muslims are even more likely to participate, providing robust support for the generational assimilation theory.Footnote 10 Even as second and third generation Muslims continue to practice their religion and observe Islamic customs, they are actively incorporating into the U.S. political system, measured by multiple acts of political participation. Holding all other values constant, second generation Muslims are 63.1% more likely to participate, and third generation respondents are 47.3% more likely to participate in American politics.

With regard to demographic and control variables, household income has a positive and significant effect on participation as we would expect (age and education is positive, but not statistically significant). Not surprising, interest in politics, measured by how closely respondents followed news about the elections, resulted in a greater likelihood of participating in politics. As compared with Arabs (the omitted comparison category) Black and Asian Muslims were statistically less likely to participate. As the largest population of the Muslim American community, Arab Americans may be the focus of more civic engagement and mobilization drives, and therefore more likely to participate than other Muslims.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This purpose of this paper is to employ the multi-dimensional concept of religiosity and test the compatibility between Islamic teachings and U.S. democratic values and how the variation in levels of religiosity impacts political participation among American Muslims. Though the inherent incompatibility continues to dominate political discussions, our findings add to the growing body of literature that this is not the case. Instead, we have shown that Islam's effect on political integration and political participation is quite similar to other faith traditions in the United States as well as other immigrant-based communities. In contrast to previous scholarship, we employ a research design that allows us to further explore the belonging components of religiosity as well as consider the attitudinal sense of compatibility.

Data analyses demonstrate that Muslims with a high degree of religiosity are significantly more likely to believe Islamic teachings are compatible with political participation in the United States, and further, they are significantly more likely to report engaging in multiple acts of political participation in the United States. In contrast, Muslims with the lowest measure of religiosity were much more isolated from the American political system, and thus less likely to believe that the two systems are compatible. We add to the body of literature that suggests as a religion and as a culture, Islam is not in conflict with the core values of American participatory democracy (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2009; Jamal Reference Jamal, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; Read Reference Read2007, Reference Read2015).

These findings are also consistent with numerous studies that demonstrate clear relationships between religious activity and civic engagement. In terms of Layman's (Reference Layman1997) “behaving,” similar to other religious groups where attendance is important, Muslims who attend mosque more frequently are more likely to support compatibility and participate in political acts (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Cassel Reference Cassel1999; Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Attendance in religious communities exerts political influence through clergy and fellow participants. For Muslims, increased exposure can create opportunities to increase social capital (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009; Putnam Reference Putnam2000). Just as Christian churches have helped promote political participation among White and Black Americans (Djupe and Gilbert Reference Djupe, Gilbert, Leege and Wald2009; Harris Reference Harris1994; Rozell and Wilcox Reference Rozell and Wilcox1997), and the Catholic Church for Latinos (Lee and Pachon Reference Lee and Pachon2007), the mosque helps promote incorporation, and support for political participation among Muslims.

In terms of Layman's (Reference Layman1997) “belonging” we examine feelings of commonality with other Muslim's. Though scholars have attributed the importance of feelings of identification with members of their religious tradition, we suggest that Muslim commonality is especially important. Islam is a religion, and therefore Muslims are considered a religious group. However, this is not the entirety of their social identification. In addition to sharing a common religion, Muslim Americans can be viewed as an ethnic minority group, which has much more in common than just religion. In fact, a recent empirical study of Muslim political participation in the United States by Jalalzai (Reference Jalalzai2009) focused exclusively on racial/ethnic demographic variables as predictors of participation, suggesting strongly that variable such as nativity and race do matter. Similar arguments were made about Jewish and Catholic Americans in the early 1900s (Goldstein and Goldscheider Reference Goldstein and Goldscheider1968; Gordon Reference Gordon1964). Jews and Catholics were at the same time, immigrants, minorities, and a religious group (Herberg Reference Herberg1955). Today, the same can be said for Muslim Americans. In addition to outlining the relevance of religiosity to Muslim political incorporation, it is equally important to analyze Muslims as a minority group and through the lens of racial and ethnic politics literature. As our findings demonstrate, Muslim commonality was a strong driver of attitudes toward compatibility and an important indicator for likelihood of participation, a finding Jamal (Reference Jamal2005) concluded, but did not test directly given data limitations.

The importance of sacred text and following religious tenets in one's day-to-day life, Layman's (Reference Layman1997) “believing,” was, at first glance, the most troubling finding. Though religious guidance was a positive and significant indicator of support for attitudinal compatibility, it was also a strong negative driver of political participation. We suggest it furthers our hypothesis that the most devout, those with the highest religiosity, support compatibility. A more thorough review of Islam suggests this apparent inconsistency is actually consistent with the beliefs and practices of some very devout Muslims. As suggested by March (Reference March2006; Reference March2007; Reference March2011) and Abdul Rauf (Reference Abdul Rauf2004), the teachings of Islam and the prophet Mohammad instruct Muslims to respect and uphold the customs and laws when they find themselves in non-Muslim societies. The findings suggest that Muslims who make the Qu'ran and Hadith a very significant part of their daily life, are considerably more likely to support the notion that Islam is compatible with political participation in the United States. However, this support or respect of the civic culture in the United States, does not necessarily translate into direct civic engagement in the sense of active participation. Instead, such Muslims may be described as having a very personal and devout relationship with Islam, in which their spirituality provides sustenance. Although, getting involved in political affairs in the United States would not conflict with Islam, political participation would not add to their individual practice of Hadith. Thus they choose to remain as spectators, perhaps even cheering fans, but they do not take the field and participate.

In addition to these key points regarding religion and politics, we have argued and demonstrated that Muslims follow a pattern of political incorporation similar to other immigrant-based minority groups. With each successive generation in the United States, Muslim Americans exhibit closer ties to the American political system by their endorsement of the democratic process (Bloemraad Reference Bloemraad2006). Beginning with foreign-born citizens, as Muslims gain admittance into the political apparatus of the United States, they appear to embrace democratic values, a trend that continues for second and third generation Muslims in the United States (Espenshade and Ramakrishnan Reference Espenshade and Ramakrishnan2001; Hochschild and Mollenkopf Reference Hochschild and Mollenkopf2010).

Ultimately, the Muslim community, the mosque, and Islam as a religious tradition should be viewed as sources of political incorporation into the U.S. polity. Muslims who think they have very little in common with other Muslims and not well integrated into the local or national Muslim community are consistently more skeptical about political participation. Similarly, those who are not at all involved in their mosque are among the least likely to participate.

As the Muslim American population continues to grow, many will question the degree to which Muslims are incorporated into the social and political structures in the United States. Especially as the global war on terrorism expands, voices here in the United States will remain doubtful about the ability of persons of Muslims faith to support American values. Our findings suggest that Islam is a source of integration into American political participation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the collaborators of the Muslim American Public Opinion Survey and The American Muslim Research Institute (AMRI) at University of Washington Bothell. We also received helpful feedback and suggestions from Youssef Chouhoud, Nazita Lajevardi, Stephen El-Khatib, Kassra Oskoii, and Loren Collingwood.

APPENDIX

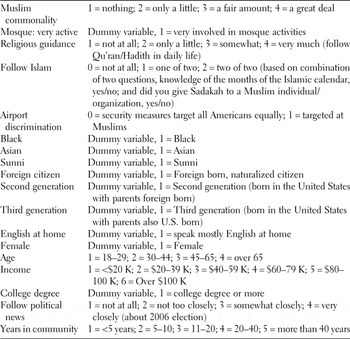

Table A1. Construction of independent variables in analysis

Table A2. Demographic characteristics of Muslim American Survey

The first variable, Muslim commonality, measures how much a respondent thinks they have in common with our Muslims living in the United States, and ranges from nothing (a value of 1) to a great deal (a value of 4). Given the great diversity within the Muslim population, this variable puts emphasis on the religious-community connection that Muslims do or do not have with one another.

The second variable in this series is mosque attendance, and we introduce two dummy variables for the upper and lower bounds of mosque attendance, very involved and not at all involved, leaving two middle categories of somewhat and not too much as the omitted comparison groups. We wanted to introduce these two dummy variables to capture the potential non-linearity of the relationship between mosque involvement and attitudes towards political incorporation. For example, it might be that Muslims who are extremely involved and active within the mosque embrace political participation, or they could reject it as too secular. At the same time, those who never attend the mosque except for an occasional prayer service, might be more “Americanized” and be inclined to participate. In order to test for both of these possible effects we include mosque attendance as two dummy variables in the compatibility model. However, in the political participation model we include mosque attendance as a single categorical variable in line with research by Jamal (Reference Jamal2005), which specifically examined the impact of mosque attendance on political engagement. In order to compare our results with hers, it is necessary to keep the variable consistent (for which the question wording is identical).

The next religious-based independent variable, which we call religious guidance, is based on the question, “How much do you follow the Qu'ran and Hadith in your daily life? Very much / Somewhat / Only a little / Not at all.” This variable is important because it assesses the degree to which Muslims bring Islam into their personal, and daily lives, as opposed to a once a week experience for Friday prayers in the mosque. The subpopulation that stated “very much” is of particular interest, because they are the source of conflicting opinions on Muslims and incorporation into the West. One the one hand, Huntington and Lewis clearly state religiously devout Muslims reject the rule of misbelievers. On the other hand, March and Abdul Rauf argue that obedient practitioners of the Qu'ran and Hadith would be quick to support the ideals of a democratic society.

Finally, we include a variable called follow Islam, which measures the knowledge and actual practice of Islamic teachings. This variable is constructed based on the following two questions in the survey: “Which is not a month in the Islamic calendar?” and “During 2006 did you provide Sadakah to a Muslim individual or organization?” The first question about the Islamic calendar presented four possible options, and respondents were re-coded as simply correct or incorrect. Among our sample, 79% knew which month was not in the Islamic calendar. The second question about Sadakah determines practice. Sadakah (or sometimes zakat), means voluntary charity and is one of the pillars of Islam. According to the Qu'ran Muslims are required to give Sadakah every year. In our sample, two-thirds of respondents practiced Sadakah. Thus in combination, the variable follow Islam is a measure of how closely the respondent knows and follows the pillars of the religion.