Stereotypes about Native Americans are common in popular culture, media, and education.Footnote 1 From movies to school projects, American Indians are often portrayed as historical figures in a romanticized world, people who lived long ago in harmony with nature. These stories and stereotypes, however, rarely include recognition of Native Americans as modern individuals living in contemporary times. How do average Americans view Native Americans? How knowledgeable are U.S. citizens about Native Americans and Native American histories and issues? Given the ubiquity of stereotypes about Native Americans in early childhood education and founding narratives of the United States, to what extent do individuals understand the contemporary reality and experiences of Native Americans? And, more importantly, how are their attitudes shaped and influenced?

Although research exists on discrimination and racial resentment toward Black and Latinx populations in the United States, Native Americans have been almost entirely excluded from the race and ethnic politics literature (McCulloch, Reference McCulloch1989; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2016; Wilmer, Reference Wilmer2016). This paper helps fill in gaps on public attitudes about discrimination and racial resentment toward Native Americans. This understanding is important for a number of reasons. First, as issues of racial injustice have gained national attention, it has become increasingly clear that people hold very different views of discrimination and who experiences discrimination. For some, discrimination is obvious and everywhere, and for others, it is very hard to believe. Understanding how and why people are able to acknowledge the experiences of minority groups is crucial to knowing how groups can build compassion and a better future. Second, understanding attitudes about Native Americans is important in its own right because of the unique history of genocide, displacement, and outright erasure of Native Americans in the course of American political development.

Many people in the United States have never met a Native American person and are somewhat unclear on whether Native Americans continue to exist as distinct groups today. At the same time, Americans' awareness of stereotypes and stories about Native Americans is very high. Moreover, most Americans assume they have a high sense of familiarity about Native American history and culture, but they actually have very little factual knowledge about it. How do people form attitudes about Native Americans in this context?

We examine these questions using new and original data from the Reclaiming Native Truth project conducted by First Nations Development Institute, a 41-year-old national Native American-led nonprofit organization. The goal of Reclaiming Native Truth was to explore for the first time what different groups of Americans—across socioeconomic, racial, geographic, gender, and generational cohorts—think and know about Native Americans and Native American issues (First Nations Development Institute and EchoHawk Consulting, 2018).Footnote 2 To this end, First Nations, with a team of technical and Native community advisors, collected original data consisting of two national surveys; 28 non-random opt-in focus groups, including two national online focus groups; and dozens of interviews with political elites, including politicians, congressional staff members, federal judges, and individuals working in philanthropy in 2017 and 2018.

We draw on a nationally representative survey of 3,200 individuals conducted from September 12 to 24, 2017, and qualitative focus group data with more than 200 people conducted from February to May 2017 (prior to our survey) in 10 states as part of the Reclaiming Native Truth project. The focus group data helped identify issues and themes that informed the development of the national survey to get a more systematic understanding of these attitudes. We explore how U.S. residents view Native Americans, focusing on (1) attitudes about Native American discrimination and (2) generalized feelings of resentment toward Native Americans. Together, these indicators allow us to test both the extent to which people recognize levels of discrimination that Native Americans face, and the extent to which they hold hostile and resentful views toward Native Americans. Because of the widespread nature of myths and stereotypes about Native Americans and the low levels of factual knowledge, this is an important distinction.

We find that political ideology (liberal versus conservative) and how much people use stereotypes are the factors most consistently associated with resentment and attitudes about discrimination. Stereotypes, both positive and negative, play a significant role in consistently predicting attitudes about Native Americans. But different direct personal experiences, levels of perceived and factual knowledge, socioeconomic indicators, and state contextual factors are not consistently associated with views of Native American discrimination and resentment. Knowing a Native American and having visited a reservation is associated with greater awareness of Native American discrimination but not always associated with having more or less Native American resentment. Racial and ethnic minorities and women are more willing to acknowledge Native American discrimination but are not consistently distinguishable from whites and males on our Native American resentment scale. Age and income are associated with Native American resentment but not views of Native American discrimination. Older individuals tend to hold more resentful attitudes toward Native Americans and individuals with higher levels of education are less likely to hold overtly hostile or resentful attitudes. These findings show that understanding resentment and discrimination are complex in the minds of most Americans. But ideology and stereotypes are consistent and powerful factors that shape how Americans view Native Americans today and in history.

In the sections that follow, we provide background on Native Americans in the United States, and an overview of scholarship on racism and discrimination, drawing attention to the scarcity of research on this topic and the substantial impact that discrimination has for Native peoples. Second, we draw on the race and ethnic politics literature to lay out our theory and hypotheses about public attitudes toward Native Americans. Third, we present our research design and data, followed by a discussion of the findings and implications.

1. Native Americans, discrimination, and resentment

Native American nations are legally defined as “domestic dependent nations” and interact with local, state, and federal governments uniquely and differently from other ethnic and racial groups in the United States (Deloria and Lytle, Reference Deloria and Lytle1984; Wilkins, Reference Wilkins1997, Reference Wilkins2010). For Native people, colonization and genocide have been the dominant frameworks used to understand the evolution of legal and policy doctrines created to transform Native identities; steal Native land, territories, and resources; and diminish Native governance powers (Williams, Reference Williams1990; Cook-Lynn, Reference Cook-Lynn2001; Wilkins and Lomawaima, Reference Wilkins and Lomawaima2001; Evans, Reference Evans2011; Getches et al., Reference Getches, Wilkinson, Williams and Fletcher2011; Dewees and Foxworth, Reference Dewees and Foxworth2013; Dunbar-Ortiz, Reference Dunbar-Ortiz2014; Meranto, Reference Meranto2014). In other countries, and increasingly in the United States, settler-colonialism has been a dominant framework for understanding ongoing systems of power created by settler populations that seek to repress, remove, and replace Indigenous peoples and cultures (Coombes, Reference Coombes2006; Barker, Reference Barker2009; Snelgrove et al., Reference Snelgrove, Dhamoon and Corntassel2014; Wadsworth, Reference Wadsworth2014; Strakosch, Reference Strakosch2019; Beauvais, Reference Beauvais2020, Reference Beauvais2021).

Although colonialism and settler colonialism are key frameworks many Indigenous scholars use to understand the interactions of Indigenous nations and settler-states, racism, stereotypes, and discrimination are all tools used to justify, maintain, and perpetuate systems of settler-colonialism against Indigenous peoples in the United States and beyond. Like other racial and ethnic minority groups in America, Native people are categorized and discriminated against because of how they look, where they live, what their cultural practices are, and more. In this paper, we are interested in understanding American attitudes about Native American discrimination and resentment and the factors shaping them.

1.1 Discrimination against Native Americans

Discrimination against Native Americans is real and measurable. We know crimes of hate are committed against Native people based on their racial and ethnic identification. In fact, in 2017, hate crimes against Native Americans rose by 63% from the previous year—a year when hate crimes overall rose by 17% nationally (FBI, 2018; Mathias, Reference Mathias2019). Many of these hate crimes occur in towns that are in close proximity to Native reservations (United States Commission on Civil Rights, 2015; Denetdale, Reference Denetdale2016). Native Americans also experience racism and discrimination in other institutional settings of American life, including in the criminal justice system (Tighe, Reference Tighe2014), education system (Indian Country Today, 2019), and foster care system (Ganasarajah et al., Reference Ganasarajah, Siegel and Sickmund2017).

One of the few national studies to document the levels of racism and discrimination that Native Americans face today is the Discrimination in America survey conducted by National Public Radio, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. They report that 75% of Native Americans believe that discrimination against Native Americans exists today and nearly one-third of Native Americans report discrimination in applying for employment, and in interactions with police and the courts. Native Americans also have higher personal experiences with violence, microaggressions, sexual harassment, and being called racial slurs (Findling et al., Reference Findling, Casey, Fryberg, Hafner, Blendon, Benson, Sayde and Miller2019). Discrimination is even more pervasive in majority Native American areas (Findling et al., Reference Findling2017).

Although research indicates that Native Americans experience high rates of discrimination and racism in everyday life, our focus group data suggest that many Americans really do not believe Native Americans face discrimination today. Focus group comments below suggest that Native American population size, lack of news coverage, lack of familiarity, and knowledge all feed the idea that Native people do not experience discrimination today.

“I think that Native Americans face less discrimination because they are less visible. When was the last time you encountered a Native American? And someone like Jessica Biel who claims to be .0001% Choctaw doesn't count.” (NY)

“I would say they don't face a great deal of discrimination because I have not heard about many situations that involve them.” (FL)

“I feel like Native Americans do not experience a great deal of discrimination mainly because I don't hear about it in the news. Maybe there is a bigger discrimination facing Native Americans, but it is not out in the media.” (MI)

Although there is evidence that many Americans do not understand contemporary Native American life, including their experiences with racism and discrimination, we know that Native people do experience discrimination and systemic racism in real and meaningful ways. In psychology, there is evidence that suggests non-Native individuals tend to invalidate, nullify, and exclude Native experiences of racism, discrimination, and settler colonialism, even in the face of evidence (Clarke, Reference Clarke2002). With this understanding as a starting point, we move on to consider how perceptions about Native Americans are formed.

1.2 Resentment toward Native Americans

Scholars of race and ethnic politics have made great strides in better understanding how discriminatory attitudes translate into political outcomes like support for public policies and social goods for historically marginalized and excluded groups. Moreover, scholars have identified that relative discrimination can motivate group political action (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Cepuran and Garcia-Rios2020). We also know that the dynamics of racism and discrimination have changed over time. Racism today is less about beliefs in biological group inferiority. Rather “new racism” is based on the idea that racial and ethnic groups violate norms of individualism, hard work, and other values associated with the Protestant work ethic (Kinder and Sears, Reference Kinder and Sears1981). Taking roots in the Black political experience, this “new racism” argues:

Opposition to policies designed to assist blacks was born out of a blend of traditional American moral values and anti-black affect. The result is a coherent set of beliefs including the sense that discrimination is no longer an obstacle for blacks, that their current lack of upward social mobility is caused by their unwillingness to work hard, that they demand too much of government, and that they have received more than they deserve (Hutchings and Valentino, Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004, 390).

Beyond the Black experience, this new form of racism, which includes symbolic or modern racism and racial resentment, is associated with generalized outgroup hostility and anti-Latino attitudes (Kalkan et al., Reference Kalkan, Layman and Uslaner2009; Kinder and Kam, Reference Kinder and Kam2010; Reny et al., Reference Reny, Valenzuela and Collingwood2020). But, we have very little understanding about what influences feelings of resentment and hostility toward Native Americans. Our focus group data highlights that many Americans do believe that Native Americans violate American norms of hard work and material wealth. The following are comments from focus group participants, many assuming that Native Americans do not pay taxes or that they receive special benefits, including goods and services, from both tribal and federal governments just for being Native American.

“If you can prove you are a percentage of Native blood you get a check every month…but you need to prove it to the tribe and they send it to the government. I know for a fact that it's true.” (CA)

“As long as you stay on the reservation, they give you a house and a truck. Once you go to the city, they cut you off.” (AZ)

They get “free healthcare, housing, money from casinos, no taxes, scholarships, cash assistance.” (NM)

“They are tax exempt. From what I understand, American Natives are not taxed on things the rest of us are taxed on. The government is not really their government because they were here first.” (FL)

The view that Native Americans violate norms associated with American values of hard work, individualism, and materialism (i.e., the Protestant work ethic) is not new and has always been part of the “White man's burden” or rather America's “Indian Problem” (Wax and Buchanan, Reference Wax and Buchanan1975; Cornell, Reference Cornell1990; Meranto, Reference Meranto2001; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2007). In sum, U.S. colonization is rooted in the theft of Indigenous lands and the need to extinguish Native American identities. Federal policies to extinguish Native American identities and forcibly assimilate Native Americans into American society intensified in the late 19th century. As Thomas Morgan, the appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs, noted in 1889:

Events demand the absorption of the Indians into our national life, not as Indians, but as American citizens. As soon as a wise conservatism will warrant it, the relations of the Indians to the Government must rest solely upon the full recognition of their individuality. Each Indian must be treated as a man, be allowed a man's rights and privileges, and be held to the performance of a man's obligations… He is not entitled to be supported in idleness. The Indians must conform to the white man's ways, peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must…tribal relations should be broken up, socialism destroyed, and the family and the autonomy of the individual substituted…the development of a personal sense of independence, and the universal adoption of the English language are means to this end (Morgan, Reference Morgan and Paul Prucha2000, 173–74).

As Morgan makes clear, Native identities, languages, cultural practices, and forms of social organization were seen as savage, uncivilized and a threat to the development of the American republic. Consequently, in an effort to transform Native American identities, the federal government outlawed Native cultural practices, used military intimidation to create systems of reward and punishment for Native Americans to access food and other goods, and empowered local Indian agents to discourage and punish Native people who committed “Indian offenses” (Cornell, Reference Cornell1990). Moreover, the federal government passed the General Allotment Act of 1887 to break up collective tribal land masses and force Native Americans to make “productive” use of land through farming and ranching (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien1993; Meranto, Reference Meranto2001; Wilkins and Stark, Reference Wilkins and Stark2017). The federal government and its missionary allies also saw education as a pathway to American civilization by directly targeting Native American children. Starting in the 1880s, boarding schools, located far from Native American communities, were opened and supported with federal dollars to remove Native American children (many times forcibly) from their homes. Native children arrived at boarding schools where their hair was cut, traditional clothing discarded, and Native languages banned, permitting little to no communication with families. The federal government thought that boarding schools would teach Native children the habits of civilization in an effort to “Kill the Indian, and Save the Man” (Adams, Reference Adams1995; Ellis, Reference Ellis1996; Archuleta et al., Reference Archuleta, Child and Lomawaima2000; Pember, Reference Pember2019).

This period of Native American history exemplifies how federal policymakers viewed Native American identities as a threat to the values of the newly developed American national identity. Native languages and cultural practices, communal land holdings, and overall refusal to adopt American ways of life were seen as a threat to American political development. From the late 19th century until the 1930s, Native nations lost over 138 million acres of land, approximately two-thirds of the land they had prior to the enactment of the General Allotment Act (Indian Land Tenure Foundation, N.D.). Moreover, thousands of Native children were taken from their homes, many suffering physical and sexual abuse, that resulted in lasting generational impacts on the mental and social health of Native peoples. Native people today view the policies passed during this period of American political development, targeting Native lands, identity and children, as genocide (Tinker, Reference Tinker1993; Cook-Lynn, Reference Cook-Lynn2001; Dunbar-Ortiz, Reference Dunbar-Ortiz2014; Smith, Reference Smith2015).

Despite these policies, Native people still maintain distinct cultural and political identities. But the idea that Native people violate the norms of what it means to be American has historical roots and, as the comments from our focus groups suggest, still persist today. We test the extent to which resentment toward Native Americans is alive today and shaped by a variety of social, psychological, and political factors. Since many people, unfortunately, are only loosely aware of historic or current realities for Native Americans, what attitudes do people hold and what factors shape those attitudes?

2. Theory and hypotheses

We argue that most peoples' perceptions about Native Americans are shaped in a context of high familiarity with romanticized versions of history and commonly held stereotypes, and very little factual knowledge. Under these conditions, people use shortcuts to inform their attitudes, including political ideology and both positive and negative stereotypes. EducationFootnote 3 and personal experiences with Native people also shape attitudes, but we expect there is little consistency in the relationship between personal experiences, socioeconomic, and contextual factors since most people base their perceptions of Native people on the shortcuts available to them.

Our survey tells us that there is a real disconnect between factual knowledge that individuals hold about Native Americans and self-assessed familiarity. The correlation between our measure of factual knowledge (based on responses to questions about Native American history and reality) and self-assessed familiarity (a 10-point scale ranging from extremely familiar to not at all familiar) is .15.Footnote 4 In other words, people are not very good at evaluating their own knowledge and most people overestimate how much they know and understand Native American experiences, history and present realities.

Because of social desirability (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Lau and Smith1990; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Mondak, Reference Mondak2000), individuals may overestimate their levels of knowledge about Native Americans. From our focus group interviews, it was clear that individuals lacked a large degree of factual knowledge about Native Americans and were resistant to changing their assumptions and false beliefs even in the face of new factual information. The conversations were mostly hypothetical, but very few focus group participants were able to accurately describe key aspects of Native history or current realities of Native people in the United States, in contrast to their readiness to talk about myths and fictional Native Americans. Although individuals tend to assess their own knowledge and expertise of Native American culture and history very highly, this self-assessed knowledge is likely overestimated and will have little or no effect on attitudes about Native American discrimination or resentment.

2.1 Political ideology

We expect political ideology to be directly associated with individual attitudes about Native Americans. Political ideologies are belief systems that shape judgments about politics and policy (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964). Ideology is not reflective of individual knowledge about politics or policy, but general evaluations about politics tend to be consistent with ideological identification (Jacoby, Reference Jacoby1991; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). No empirical literature connects ideology to attitudes about Native Americans but we do know that conservative individuals tend to have greater feelings of resentment toward certain minority groups because those groups violate core principles associated with conservative values (Gilens, Reference Gilens1996; Virtanen and Huddy, Reference Virtanen and Huddy1998; Feldman and Huddy, Reference Feldman and Huddy2005). Thus, there is reason to expect that conservatism will be associated with both less acknowledgment of Native American discrimination and also greater degrees of resentment toward Native Americans.

2.2 Native American stereotypes

General attitudes about Native Americans may be disproportionally influenced by stereotypes. People are very familiar with Native Americans as historical and invented figures from the past and hold an understanding of Native Americans in romanticized versions of frontier stories (Corntassel and Witmer, Reference Corntassel and Witmer2008). Conversations from our focus groups show that people are unapologetic in describing these stereotypes, mentioning Disney movies, feathers, and headdresses. Many people described their impressions of Native American people as spiritual and as having a special connection to the environment. For example, when individuals in our focus groups were asked to name the first thing that comes to mind when they think of Native Americans, some answers were:

“People who love the Earth and the things that come from it.” (NM)

“Nature. In tune with everything. Care for the land.” (AZ)

“Rich in faith. Spiritual rather than religious. Mystical.” (NM)

“Their way of life is different- their mother is mother earth, spiritual person.” (CA)

People were also forthcoming in their negative stereotypes, making quick associations with poverty and alcoholism. People readily reported contradictory stereotypes, in one sentence mentioning how Native Americans may be getting rich from Native American gaming but in the next instance discussing Native American poverty and alcoholism (First Nations Development Institute and EchoHawk Consulting, 2018). One stereotype that has been top of mind for Native Americans across the United States is the use of Native American mascots. Native Americans have continuously said that the use of Native Americans as mascots is inflammatory and racist and has significantly negative effects on the self-esteem and sense of worth for Native American children (Fryberg and Townsend, Reference Fryberg, Townsend, Adams, Biernat, Branscombe, Crandall and Wrightsman2008; Fryberg et al., Reference Fryberg, Markus, Oyserman and Stone2008, Reference Fryberg2020). Defenders of Native American mascots have said that the use of mascots honors Native Americans. As longtime defender of Native American mascots Dan Snyder notes, “I'd like them (Native Americans) to understand, as I think most do, that the name really means honor, respect” (ESPN News, 2014). In our focus groups, many individuals were suspicious or rejected Native American grievances about the use of Native American mascots noting:

“Wouldn't be surprised if they were complaining just to get some money out of it.” (FL)

“They have other things to worry about.” (NM)

“It's an honor. People don't name sports teams after wimpy things.” (AZ)

As our focus group data indicate, the stereotypes people hold of Native Americans are mixed. Stereotypes are dynamic cognitive tools that facilitate information processing. Some can be categorized as positive (Native Americans as close to nature and spiritual), and some are explicitly negative (Native Americans as mascots). We know that positive stereotypes are more subjective and negative stereotypes are more durable and elicit greater affective reactions to political issues (Gilens, Reference Gilens1996; Hurwitz and Peffley, Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1997; Burns and Gimpel, Reference Burns and Gimpel2000; Peffley and Hurwitz, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2002; Wood and Bartkowski, Reference Wood and Bartkowski2004).Footnote 5

Given this discussion, we expect that both positive and negative stereotypes will have effects on perceptions of Native Americans more generally. We expect that negative stereotypes will be associated with less willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination and greater resentment, whereas positive stereotypes will have the opposite effect.

2.3 Contact and personal experiences with Native Americans

Personal experience of knowing a Native person, or visiting a Native American reservation, may be an important counterweight to the more fictional information many people are exposed to. The idea that personal contact may reduce negative attitudes toward outgroups dates back to Allport's view that intergroup contact can reduce prejudice (Allport et al., Reference Allport1954). In line with this literature, contact with Native people and visiting Native communities may be a powerful force in the lives of individuals and shape more supportive attitudes about Native American people. Since Native people are a small percentage of the U.S. population and are depicted in negative and stereotypical ways in popular culture, actually knowing a Native person or having visited a reservation can reduce negative and prejudice views and behaviors of individuals.

2.4 Hypotheses

Based on these expectations, there are several specific hypotheses that we will test with our survey data. First, in thinking about what shapes views on discrimination, we expect the following: individuals with higher levels of education, more factual knowledge, and more personal contact and experience with Native Americans are more likely to acknowledge Native American discrimination. In contrast, conservative ideology and negative stereotypes will lead to less willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination.

We have the following expectations related to resentment toward Native Americans. First, we expect that knowledge and education will be associated with less resentment, as will holding more “positive” stereotypes of Native people. Holding negative stereotypes will be associated with greater resentment toward Native Americans. Familiarity, on the contrary, because it is so disconnected with factual knowledge, is unlikely to play a large role in shaping these attitudes. Finally, we expect conservatives to hold more resentment toward Native Americans as they do with other racial and ethnic minority groups.

3. Data and measures

To explore these hypotheses, we draw on a national telephone survey fielded in September 2017 as part of the Reclaiming Native Truth project. There were 3,200 respondents, age 18 and over from 49 states (there were no respondents from ND) and the District of Columbia. Each survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The probability survey included oversamples of African Americans (506), Hispanics (582), and Asian and Pacific Islanders (239), as well as oversamples in MI (253), MS (215), and NM (221).Footnote 6 Forty-eight percent of interviews were conducted on cell phones and all the interviews were conducted in English. To explore the factors that shape attitudes more rigorously, we use multilevel mixed-effects linear regression models to estimate the effect of both individual and state contextual factors on attitudes about Native Americans. Full question wording for indicators is included in the Appendix. We use multilevel models because our individual observations are clustered within states and this modeling strategy allows us to account for the clustered nature of the data (Bryk and Raudenbush, Reference Bryk and Raudenbush1992; Kreft and De Leeuw, Reference Kreft and de Leeuw1998; Steenbergen and Jones, Reference Steenbergen and Jones2002).

3.1 Dependent variables

We are interested in understanding public attitudes about Native Americans along two dimensions: the extent to which individuals acknowledge Native American discrimination and levels of resentment toward Native Americans.

3.1.1 Attitudes about discrimination

The first dependent variable in our analysis captures the extent to which individuals think Native Americans are discriminated against. Respondents were asked, “Do you believe Native Americans face a great deal of discrimination, a lot of discrimination, a moderate amount, a little, or none at all.”

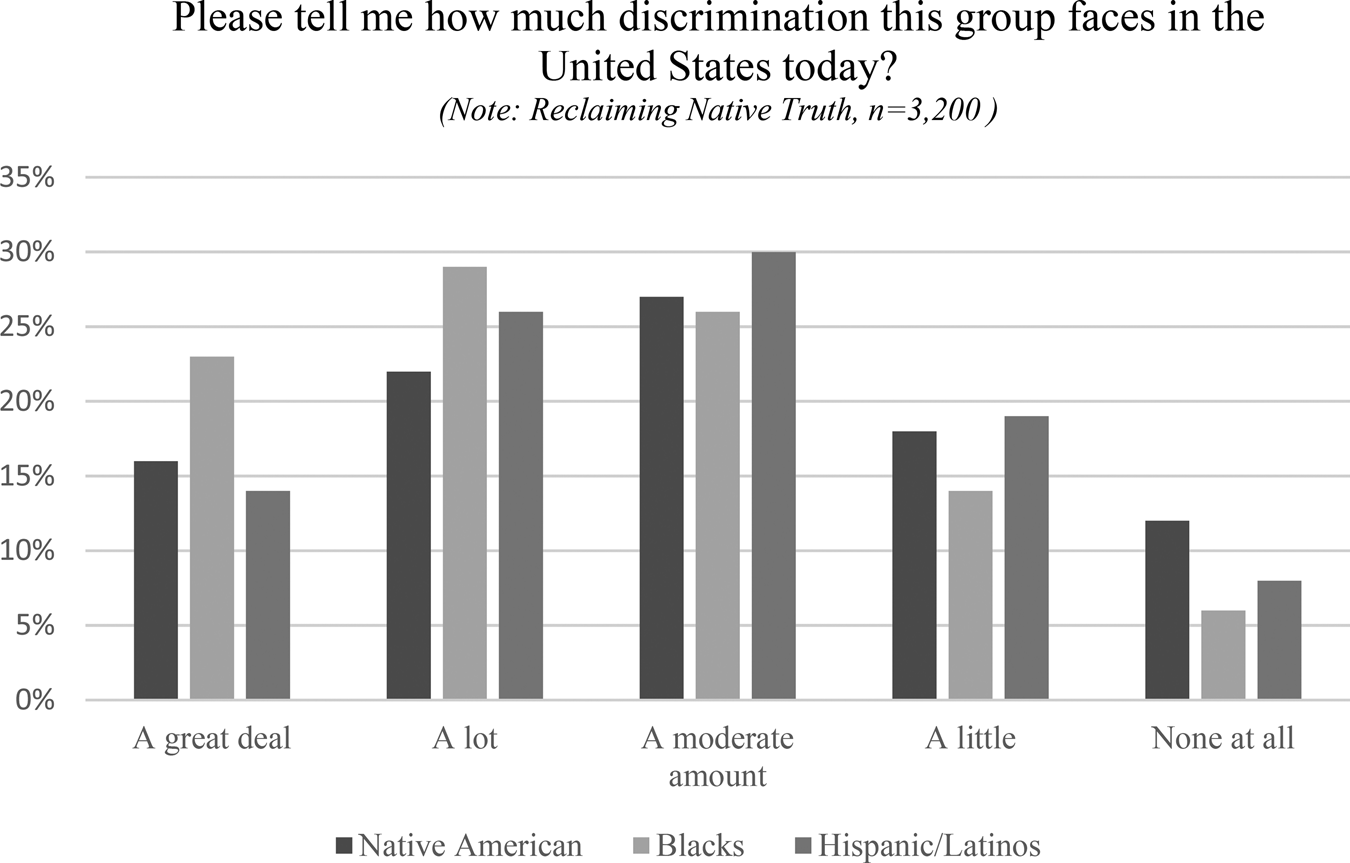

As discussed earlier, many individuals who participated in our focus groups assumed Native Americans did not experience much discrimination. Our survey data mirror similar public attitudes in that average Americans think Native Americans are discriminated against less than other racial and ethnic groups. As noted in Figure 1: Americans believe that Black people experience the highest levels of discrimination with 42% of respondents saying that Black people experience a great deal or a lot of discrimination; 40% of respondents say that Latinos experience a great deal or a lot of discrimination. This is compared to 38% of respondents who say that Native Americans experience a great deal or a lot of discrimination. Forty-nine percent of respondents believe that Latinos experience a moderate or a little amount of discrimination and 46% believe the same about Native Americans; and 12% percent of respondents believe that Native Americans experience no discrimination, the highest rating among all groups.Footnote 7

Figure 1. Attitudes on discrimination toward Native Americans.

3.1.2 Resentment toward Native Americans

We utilize an additive scale that taps different dimensions of resentment toward Native Americans, drawing on existing studies of racial resentment. We draw on the pathbreaking study of Beauvais (Reference Beauvais2020, Reference Beauvais2021) whose research has examined settler resentment toward Indigenous peoples in Canada. Our Native American resentment scale comprises four questions that ask about agreement with the following statements: (1) The United States has done enough already for Native American peoples and tribes, including providing free health care, welfare, and education, as well as millions of dollars from casinos. (2) What happened to Native Americans in this country is tragic, but we can't keep paying for something that happened centuries ago for the rest of time. (3) Other ethnic groups and minorities have experienced unfortunate injustices throughout our country's history, and while our government has taken steps to right some of those wrongs, it's unfair to give preference to one group over another. (4) America is a melting pot, and Native Americans will not enjoy all the benefits of this country until they leave their reservations and assimilate into the broader American culture, just like the Irish, Italians, and other groups have done. Respondents were asked to indicate agreeability with each of the four statements on a scale of 0–10, where 0 means strongly disagree and 10 means strongly agree. Combining these variables yields a new additive resentment toward Native Americans index that ranges from 0 to 40, and higher values are associated with greater feelings of resentment or hostility. These four indicators are highly correlated and produce a scale reliability correlation of .77. Figure 2 provides the distribution of this scale.

Figure 2. Resentment toward Native Americans histogram.

We acknowledge there is exciting scholarship emerging that questions the extent to which common measures associated with broader racial resentment apply to Indigenous populations. Since Indigenous conflict with settler societies is often based on disputes around land, treaties and natural resources, and preservation of Indigenous languages and cultures, different measures of resentment may be needed to reflect modern American/settler hostility toward Native Americans (Beauvais, Reference Beauvais2020, Reference Beauvais2021). But based on our focus groups and the explicit assimilation and cultural transformation goals of federal Indian policy, we believe our indicators are useful in tapping elements of modern Native American resentment.

3.2 Explanatory variables

To test our theoretical expectations, we utilize the following explanatory variables.

3.2.1 Self-proclaimed familiarity

We use the following indicator to capture self-proclaimed familiarity of Native Americans: “Many people are unfamiliar with much of Native American history and culture—how about you? On a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning not at all familiar, and 10 meaning extremely familiar, how would you rate your familiarity with the topic of Native American history and culture?” The mean level of self-proclaimed familiarity was 5.7.

3.2.2 Factual knowledge

Our factual knowledge measure is an additive measure based on responses to a series of true and false questions about Native Americans. For this, we asked: Please tell me if you believe this statement is almost certainly true, probably true, probably untrue, or almost certainly untrue. If you are not sure, just say so. The full questions are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Factual knowledge questions

Note: Answers were coded as correct if respondent said “true” or “probably true” for true statements and “untrue” or “probably untrue” for false statements.

All responses are recoded based on right and wrong answers to questions, where 1 is a right answer, and 0 is a wrong or don't know response. We then create an additive factual knowledge scale, ranging from 0 to 5, where higher values indicate greater correct responses to the questions stated. The mean for this variable is 1.9.

3.2.3 Positive stereotypes

To measure positive stereotypes of Native Americans, we use the following indicators: Please tell me whether you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements: “Native Americans are close to the land and fight to protect the environment” and “Compared to other Americans, Native Americans are a more spiritual people.” Higher vales indicate greater agreeability. In our survey, these questions were split into two samples and 1,425 individuals responded to the question about Native Americans being more spiritual and 1,490 responded to the question of Native people as close to land. We model the effects of these individual stereotypes separately.

3.2.4 Negative stereotypes

To measure negative stereotypes, we asked respondents the following utilizing the same agreeability scale: “Sports teams that use Native American mascots, such as the Cleveland Indians and Washington R*edsk*ins, honor Native Americans.”Footnote 8 As previously discussed, we know that stereotypes are harmful and damaging to Native Americans but may also boost non-Native American self-esteem. Moreover, research notes that Native Americans strongly oppose the use of Native American mascots (Fryberg et al., Reference Fryberg2020).

3.2.5 Personal contact and networks

We include two measures that capture personal experiences with Native Americans. The first asked respondents: Do you personally know or work with someone who is Native American? The second asks: Have you personally been to or visited a Native American or Indian reservation? These are dichotomous measures where 1 is coded as a yes to each question and 0 is a no to each respective question. In sum, 47% of our respondents report having personally been to or visited a reservation and 46% of respondents report knowing or working with a Native American.

3.2.6 Political ideology

We measure ideology as a dichotomous variable where individuals who self-report their ideology as a conservative are coded as a 1 and moderates and liberals are coded as a 0.

3.2.7 Individual demographics

We include a host of demographic control variables, including whether the respondent is a racial or ethnic minority (dichotomous) and respondent's reported level of education, age, income, and gender.

3.2.8 Contextual factors

We also include a number of contextual state-level variables that may have an effect on our outcomes. We include a continuous measure capturing the total state population that identifies as Native American taken from the American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Finally, we include a dichotomous American Indian gaming measure whereby a state that has any American Indian gaming is coded as a 1 and non-American Indian gaming states are coded as a 0.

4. Results

We first examine factors that shape willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination; then, we examine factors that shape resentment toward Native Americans. What factors explain perceptions of discrimination that Native Americans face? Table 2 shows our results. Model 1 includes the full sample of more than 2,000 people. Models 2 and 3 show the results based on the split sample because the stereotype questions are not asked to the full sample.

Table 2. Native American discrimination

Notes: Multilevel mixed-effects linear regression. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

First, turning to our knowledge measures. Both the factual knowledge indicator and the self-proclaimed knowledge of Native American variables are not significant. Contrary to our expectation, having more factual knowledge about Native Americans is not associated with increased views that Native Americans experience discrimination. The self-proclaimed knowledge variable is only significant in model 1 but is not associated with views of Native American discrimination in any other models.

In Table 2, we also see that both positive and negative stereotypes matter for public perceptions about Native American discrimination. Positive stereotypes in models 2 and 3—indicating that Native Americans are more spiritual or close to the land—are associated with greater willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination. Our indicator of negative Native American stereotypes (the belief that mascots honor Native Americans) is also negative and significant across all models. Individuals who believe mascots honor Native Americans tend to believe Native Americans do not face discrimination. In sum, our results indicate that both positive and negative stereotypes have a robust effect on shaping perceptions of Native American discrimination.

Knowing a Native American person and visiting a Native American reservation are both positive and significant in all models. Having visited a reservation and knowing a Native American person are associated with greater acknowledgment of Native American discrimination. This is consistent with existing research highlighting the positive benefits of cross-group contact and communication (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1978; Sigelman and Welch, Reference Sigelman and Welch1993; Pettigrew, Reference Pettigrew1998).

Political ideology also has a significant effect on views of Native American discrimination. Conservatives are less likely to acknowledge that Native Americans face discrimination. Liberals, on the contrary, are much more likely to acknowledge discrimination.Footnote 9 This finding is robust across all models in Table 2.

Members of other minority groups and women are more likely to acknowledge that Native Americans face higher levels of discrimination in all models. Age is only significant in model 2, indicating older people are more likely to acknowledge Native American discrimination. Income is only significant in model 3, and the negative coefficient notes that as income goes up, the willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination goes down. Aside from race and ethnicity, these results suggest that demographic and socioeconomic factors are not a consistent predictor of attitudes toward Native Americans.

Our contextual factors are not significant in any of the models with the exception of model 2. In this model, the coefficient the state has Indian gaming variable is negative and significant indicating that in states with Indian gaming, individuals are less willing to acknowledge Native American discrimination.

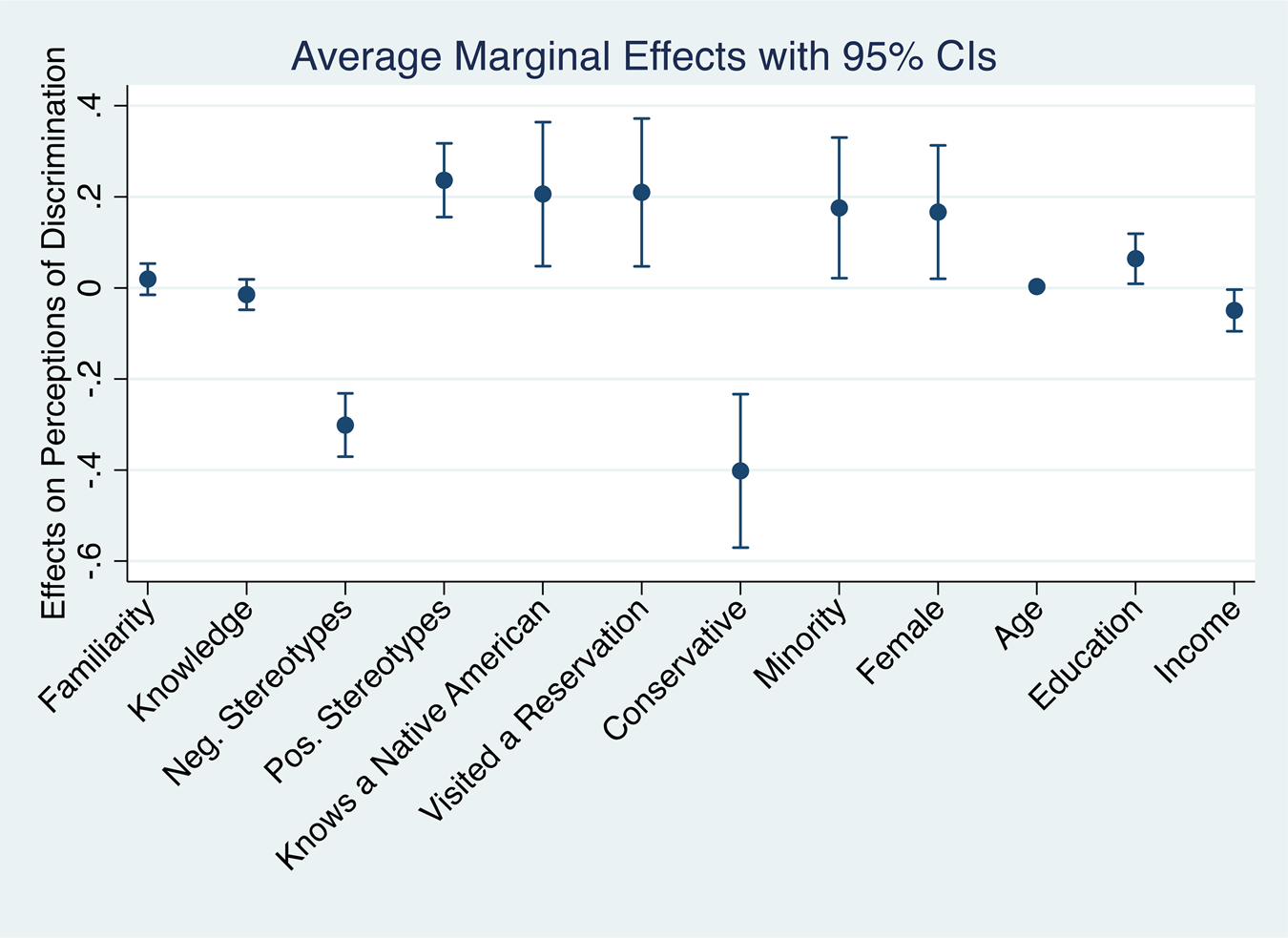

For comparison of the relative effects of these factors, we plot the marginal effects for our main variables from model 3 in Figure 3. The largest effects are from the negative stereotype variable (belief that mascots honor Native people) and the ideology variable, which shows that self-identified conservatives are much less likely to acknowledge discrimination than others. Familiarity and knowledge are not significant predictors of understanding discrimination, nor are age or income. Education also falls short of being a clear predictor of acknowledging discrimination. The people most likely to acknowledge discrimination are minorities, women, and people with some direct experience with Native Americans in their personal life or through visiting a reservation.

Figure 3. Native American discrimination (marginal effects). Note: This graph shows the linear predicted effect for each variable from the fixed portion of model 3, shown in full in Table 2. Bands around each point show the 95% confidence interval.

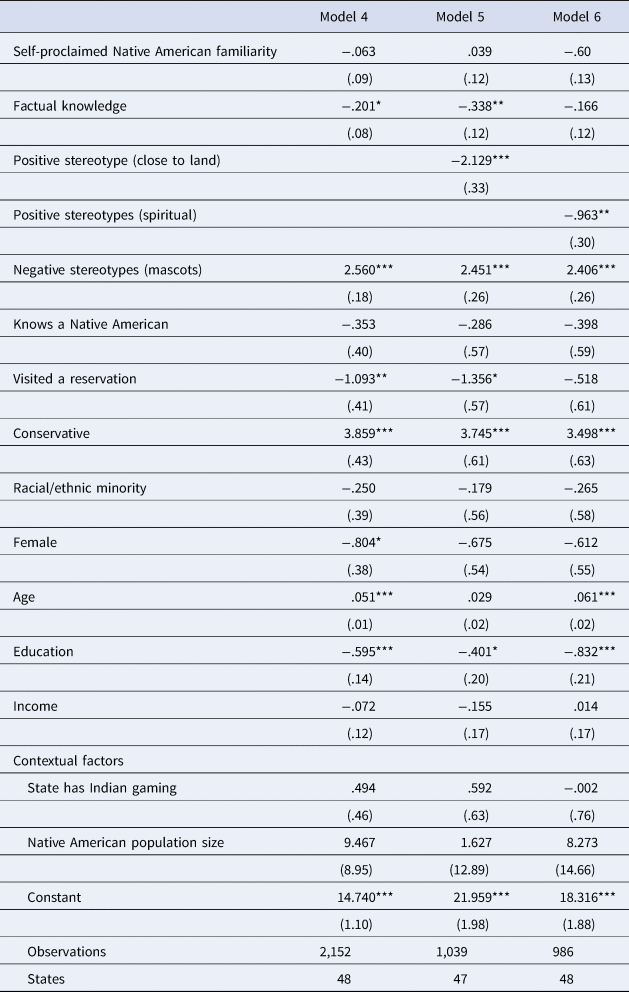

Next, we turn our attention to attitudes of resentment toward Native Americans, shown in Table 3, models 4 through 6. Again, as expected, self-proclaimed knowledge about Native Americans is not significant in any of our models. The coefficient on the factual knowledge scale is negative and significant in models 4 and 5 but is not significant in the full model (model 6), indicating that generally more factual knowledge is associated with lower levels of resentment toward Native Americans.

Table 3. Resentment toward Native Americans

Note: Multilevel mixed-effects linear regression. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Findings for our stereotype indicators are as expected: holding “positive” stereotypes of Native Americans is associated with lower levels of resentment toward Native Americans. But, individuals who believe negative stereotypes tend to have higher levels of Native American resentment.

Contact measures are more inconsistent in our resentment toward Native American models. Knowing a Native American does not have any statistically significant relationship with resentment toward Native Americans. But, having visited a Native American reservation is associated with less resentment toward Native Americans in all models except for model 6.

Similar to the perceptions of discrimination models, the coefficient on the conservative political ideology measure is significant and positive, indicating conservatives tend to have higher levels of resentment toward Native Americans. Liberals tend to have lower levels of resentment toward Native Americans.Footnote 10

The demographic factors are also inconsistent in our models looking at factors associated with resentment toward Native Americans. The racial and ethnic minority variable is not significant in any of the models, the female variable is negative and significant only in model 4, and age is positive and significant in models 4 and 6 indicating older individuals hold greater resentment toward Native Americans. Education is the only socioeconomic variable consistent across all models as shown in Table 3: as levels of education increase, Native American resentment decreases. The state contextual factors are not significant in any of the resentment toward Native American models.

Our results highlight that the willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination and having resentment toward Native Americans are shaped consistently by two factors. First, a variety of stereotypes shape American opinions about Native American discrimination and also levels of resentment toward Native Americans. On the one hand, individuals who hold more “positive” stereotypes are more willing to acknowledge Native American discrimination and have lower levels of resentment toward Native Americans. On the other hand, holding to negative stereotypes is associated with greater resentment toward Native Americans and less willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination.

Second, our results show that political ideology is a consistent predictor of attitudes toward Native Americans. Conservativism across our models is associated with greater hostility toward Native Americans: conservatives hold more resentment toward Native Americans and less willingness to acknowledge discrimination toward Native Americans. In sum, conservatives are less willing to acknowledge the hard realities of current Native American life and are more willing to believe that Native Americans violate perceived American values of hard work, individualism and materialism (i.e., protestant work ethic).

Having higher levels of factual knowledge is associated with lower levels of Native American resentment but has no effect on discrimination. Our measures of social contact, including knowing a Native American and visiting a reservation, are robust for willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination but only visiting a Native American reservation is associated with lower rates of resentment toward Native Americans. Our state contextual measures are also insignificant in most models.

Finally, demographic variables are inconsistent in explaining Native American discrimination and resentment. This is similar to the findings of Beauvais (Reference Beauvais2020), who finds that many demographic factors matter little in explaining resentment toward Indigenous peoples in Canada. In our discrimination models, race and gender are consistently associated with greater willingness to acknowledge Native American discrimination. But, in our models looking at resentment toward Native Americans, race and gender are not consistent predictors of resentment but age and education do matter in shaping attitudes about Native American resentment.

Figure 4 shows the marginal effects plot for the main variables in model 6 in Table 3. Looking at the marginal effects, the largest effects are associated with mascots and conservative ideology, both of which are associated with higher levels of resentment. Higher levels of education and holding positive stereotypes are associated with lower levels of resentment. And, minorities and women are no different from other people in their levels of resentment, even though they are more likely to acknowledge discrimination. Overall, it is clear that the strongest predictors of resentment are conservative ideology and holding negative stereotypes about Native Americans.

Figure 4. Resentment toward Native Americans (marginal effects). Note: This graph shows the linear predicted effect for each variable from the fixed portion of model 6, shown in full in Table 3. Bands around each point show the 95% confidence interval.

5. Discussion

Overall, our research shows that although many Americans have a high degree of self-proclaimed familiarity about Native Americans, they have very low factual knowledge and little personal experience with Native peoples. Factual knowledge is very important, however, in lowering hostile and resentful feelings toward Native Americans. This highlights that policies to improve factual education about Native Americans and advance factual knowledge about Native Americans in all aspects of American life may go far in improving public attitudes toward America's First Peoples.

Our findings also highlight that attitudes about Native American discrimination and resentment toward Native populations are shaped by political and psychological factors. Political ideology is a consistent predictor of both our dependent variables as were Native American stereotypes. Just as partisanship matters in shaping levels of resentment and hostility toward other racial and minority groups, the same trend persists for Native Americans.

Stereotypes of Native Americans are pervasive in American history and society. From early childhood on, Americans learn about Native people from American myth, textbooks, sports team mascots, toys, television programs, movies, and other popular cultural outlets (Fryberg and Townsend, Reference Fryberg, Townsend, Adams, Biernat, Branscombe, Crandall and Wrightsman2008; Fryberg et al., Reference Fryberg, Markus, Oyserman and Stone2008; Davis-Delano et al., Reference Davis-Delano, Gone and Fryberg2020). Stereotypes and portrayals of Native people have always served a political purpose. For example, European nations arrived to the “New World” with their own fears and prejudices and a hungry appetite for Indigenous land and resources. Consequently, European notions of “savagery” and “civilization” structured European interactions with and perceptions of Native America. But, stereotypes of the “ecological Indian” have also existed since first contact with European colonizers, seeing Native people as caretakers of the land for the preservation and use of European colonizers (TallBear, Reference TallBear2000; Harkin and Lewis, Reference Harkin and Lewis2007). These perceptions and narratives of Native America (no doubt at times contradictory) were used to justify genocide, war, and theft of Indigenous lands and resources (Berkhofer, Reference Berkhofer1978; Deloria, Reference Deloria1998; Dunbar-Ortiz and Gilio-Whitaker, Reference Dunbar-Ortiz and Gilio-Whitaker2016). Our findings demonstrate these stereotypes are still important in shaping attitudes toward Native Americans today.

It is difficult to overstate the extent to which Native history, culture, and identities have been brutalized and minimized in contemporary American popular culture and discourse. The inaccurate portrayals of Native people in diverse forms of media, myth and culture do have an effect on shaping how individuals view Native American people today. These inaccurate portrayals have led to stereotypes abound—all minimizing Native people in history and as full, modern, and current citizens of this country.

Race and ethnic politics scholars have a long way to go to understand how diverse groups, and American society at large, view Native Americans and their history and current issues. As diverse societies across the globe begin to grapple with historical inequities in their countries, how settlers view Indigenous populations will continue to be an exciting and important new area of study.

Appendix

Question wordings