Introduction

Elite polarisation is as an increasingly common phenomenon in many western democracies (Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). Studies examining the policy implications of elite polarisation usually focus on the political arena in which political conflicts over policy are dealt with, new policies are crafted and existing policies are changed (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006). However, enquiries of stability and change solely focussing on policy decisions provide only a partial assessment of the implications of elite polarisation. They do not tell us whether, and how, elite polarisation influences policy practice, i.e. the day-to-day application of formally unchanged policies. These questions need to be answered in order to obtain a more complete picture of the ways in which increasing elite polarisation changes western democracies.

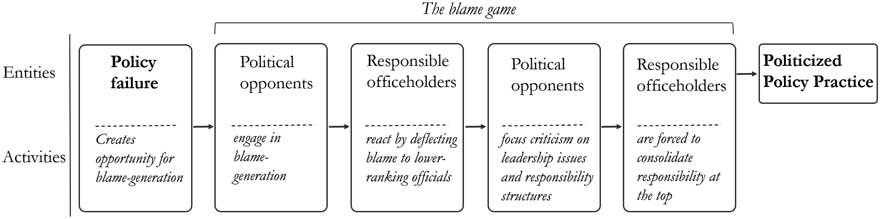

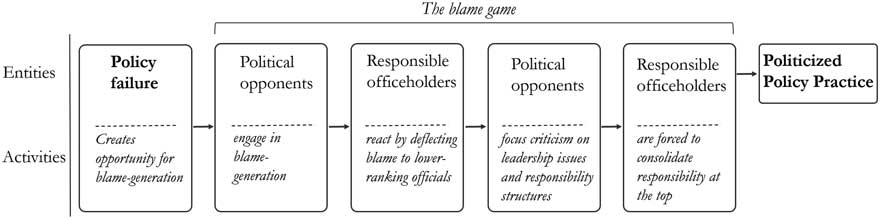

This article aims to contribute to a more complete assessment of this subject by exposing and explaining a hitherto neglected but highly important causal mechanism between political elites engaging in blame generation and changes in policy practice: policy failures provide opportunities for political elites to generate blame directed at politically responsible officeholders. Strategic interactions during “blame games” expose problem-centred, quiet policy practice to public scrutiny and criticism. Organisational adaptations made in response make responsibility travel upwards and concentrate it “at the top” – in the hands of vote-seeking officeholders. Responsibility concentration at the top makes it more likely that policy practice is driven by the material interests of officeholders who need to protect their reputation and career from public blame. A more politicised policy practice can make an important difference for policy target populations and damage output legitimacy (Scharpf Reference Scharpf2003).

To illustrate this mechanism, I develop an analytical account of the Swiss “Carlos” case, a media-induced blame game triggered by a nationally televised film on a 17-year-old youth offender in a costly therapy setting. The film caused a blame game that went on for several months and was one of the most discussed domestic policy issues in Switzerland in 2013/2014 (Schranz Reference Schranz2015). The Carlos case provides a rather sobering account of how blame generation by political elites influences policy practice. Although at first sight consensus institutions seem to fence the blame game and foreclose major policy change, a closer examination reveals that blame generation by political elites leads to increasingly politicised policy practice.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The next section reflects on the behavioural adaptations of political elites to a more polarised political climate, drawing on the literature on blame avoidance (Weaver Reference Weaver1986; Hood Reference Hood2011; Hinterleitner and Sager Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2016). In the empirical section, after chronicling the major events of the case under study, I develop an analytical account of how policy failure-induced blame games can lead to politicised policy practice. The subsequent section reflects on the behavioural adaptations that constitute a politicised policy practice and provides insights on the generalisability of the identified mechanism. In the conclusion, I highlight avenues for future research and reflect on the changing face of western democracies in the light of this article’s findings.

Behavioural adaptations to a polarised climate: a microperspective

The majority of studies analysing the policy implications of elite polarisation examines how elite polarisation influences policy formulation and policy change (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009; Barber and McCarty Reference Barber and McCarty2015). Although some studies assert that intensified political conflict can produce policy change (Fischer Reference Fischer2014), they also suggest that the checks and balances enshrined in political systems, such as majority requirements or consensual rules and practices, prove to be quite resilient and serve as bulwarks against more extreme policies (Binder Reference Binder2003; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009). Like every analytical approach that highlights “some aspects of the political world at the expense of others”, a focus on the political arena comes at the expense of the myriad, often gradual and piecemeal, ways in which policies can change – even in the absence of “big legislative changes” (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014, 644). Against this background, it is little surprising that the impact of elite polarisation on policy practice, i.e. the day-to-day application of (formally unchanged) policies, is not taken into account in existing studies. This neglect is problematic, as changes in policy practice can make a large difference for policy target populations and damage output legitimacy if policies are applied in ways that negatively influence their effectiveness (Scharpf Reference Scharpf2003). Change in policy practice is facilitated by the room for decisional discretion, which most policies provide, and those who apply a policy in a concrete case can exploit according to their needs (Lipsky Reference Lipsky2010; Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). Accordingly, this article starts from the assumption that a more fine-grained perspective that focusses on policy practice can provide for a more comprehensive assessment of the policy implications of elite polarisation.

To account for the impact of elite polarisation on policy practice, I adopt a microperspective and consider the decision-making calculations and behavioural adaptations of political elites operating under polarised conditions. Elite polarization describes a growing ideological divide between political opponents, more extreme policy positions, and, accordingly, fewer possibilities for compromise (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006; Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009). Under polarised conditions, political elites increasingly respond to media-induced scandalisations, engage in personal attacks and negative messaging, and generate blame directed at their political opponents as these strategies appear more credible in the light of a gridlocked political system (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006; Weaver Reference Weaver2013; Flinders Reference Flinders2014; Nai and Walter Reference Nai and Walter2015).

Seen against this background, policy failures can be conceived as “blaming opportunities” on which political elites can capitalise. In order to generate blame, they can point to and exaggerate the negative aspects exposed by a policy failure, ascribe the failure to the conduct of their partisan opponents (Mortensen Reference Mortensen2012; Reference Mortensen2016; Hinterleitner and Sager Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015) and, if possible, frame the whole issue in moralistic, ideological terms (Brändström and Kuipers Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003). However, not all policy failures hold equal potential for blame generation as they attract different levels of attention from the mass public. As several researchers have shown, whether an incident develops into a politicised policy failure is primarily a matter of construction (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Edelman Reference Edelman1988) and depends to a large degree on issue characteristics (Brändström and Kuipers Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003; Brändström et al. Reference Brändström, Kuipers and Daléus2008). Drawing on insights from studies examining the potential of policies to move public opinion (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007), one can theorise the characteristics of a policy that make incidents particularly amenable to blame generation.

Specifically, a policy’s proximity and visibility to mass publics should predetermine the potential scope for and the incentives of political opponents to engage in blame generation. Proximity describes the extent to which a policy “exists as a tangible presence affecting people’s lives in immediate, concrete ways” (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007, 121). The more proximate a policy is to the mass public, the more “policy knowledge” about design features and technical details the latter possesses. For a proximate policy, the public is better able to evaluate policy performance without having to rely too heavily on media and elite interpretations (Zucker Reference Zucker1978; Soroka Reference Soroka2002). With growing distance between the policy and the majority of the public, the leeway for elites to frame a policy according to their own specific needs increases. This creates possibilities for political opponents to produce a mass feedback process by blaming responsible officeholders for a policy failure. Visibility concerns the extent to which a policy is salient or appears severe to the mass public and exists as an object of conscious evaluation (Brändström and Kuipers Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003; Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007). Blame generation for a highly visible policy failure is likely to produce a stronger feedback from the mass public than for a less visible policy failure. In short, a policy’s proximity and visibility to the mass public allow us to understand the feedback processes that a policy failure is likely to produce if political opponents use it to generate blame directed at responsible officeholders.

How do responsible officeholders react to blame generated by their opponents? The blame-avoidance literature suggests that in situations where actors face blame they prioritise their material interests over more ideational motives, as “blame avoiding behavior in situations that mandate such behavior is a precondition for pursuing other policy motivations in situations that do not compel that behavior” (Weaver Reference Weaver1986, 377–378). In order to deal with blame emerging from a policy failure, officeholders can rely on presentational strategies to shape public impressions and frame the public debate about the politicised policy failure (Hood Reference Hood2011).Footnote 1 On one hand, officeholders can try to defend the policy by relativising its perceived failure and emphasising its achievements (hereinafter policy-defense strategy). On the other hand, officeholders can try to shift blame within their responsibility sphere – namely, to lower-ranked bureaucrats – who are less exposed to public scrutiny than officeholders bearing direct political responsibility (hereinafter blame-deflection strategy). Confronted with considerable blame, the blame-deflection strategy should be more promising than the policy-defence strategy. Once a policy failure has been successfully politicised, responsible politicians run the risk of becoming personally associated with the failure if they do not decide to deflect blame (Brändström and Kuipers Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003). This should even apply for officeholders whose institutional position is very safe, as for them too blame holds reputation-damaging potential.

As soon as responsible officeholders blame downwards, the operational level comes into focus, producing pressures for the adjustment of rules and procedures (Brändström and Kuipers Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003). However, existing studies neither give definitive answers as to whether and when these pressures lead to actual changes of rules and procedures nor whether such changes have an effect on policy practice. Although various blame game dynamics such as framing contests between competing actors (Boin et al. Reference Boin, Hart and McConnell2009), the type and choice of blame-avoidance strategy (Weaver Reference Weaver1986; Hood et al. Reference Hood, Jennings, Dixon, Hogwood and Beeston2009; Mortensen Reference Mortensen2012; Hinterleitner and Sager Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015; Hood et al. Reference Hood, Jennings and Copeland2016), public attribution of responsibility and blame (McGraw Reference McGraw1991; Mortensen Reference Mortensen2013) or the role of the media in so-called “feeding frenzies” (Sabato Reference Sabato2000) have been studied in detail (for an overview see Hinterleitner Reference Hinterleitner2015), it is as yet unclear whether the choice of strategy and the strategic interactions between officeholders and their political opponents within blame games have an effect on policy practice or leave the application of policies undisturbed. The remainder of this article attempts to show that blame deflection to the operational level exposes policy practice to public scrutiny and criticism. Organisational adaptations made in response make responsibility travel upwards and concentrate it “at the top” – in the hands of vote-seeking officeholders. Responsibility concentration at the top makes it more likely that policy practice is driven by the material motives of officeholders who need to protect their goals from blame.

Research design

I apply the method of causal process tracing to the Swiss Carlos case to develop an analytical account of how blame games driven by politicised policy failures lead to changes in policy practice (Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2015a; Kay and Baker Reference Kay and Baker2015). Process tracing is particularly apt for empirically assessing the relationship between politicised policy failures and consequences for policy practice, as these are rather remote phenomena linked through multiple steps. Process tracing also allows for capturing the various interaction effects that one is likely to observe during blame games (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2006; Hall Reference Hall2006). The multiple steps that connect politicised policy failures to policy practice can be conceptualised as entities engaging in activities, where activities transmit causal forces from one step to the next (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2013).

In the Carlos case, the various steps of the mechanism are particularly visible, and appropriate evidence allows for the development of a convincing explanation (Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2015b). Detailed causal-process observations allow to establish causality between the different steps of the mechanism (Brady and Collier Reference Brady and Collier2010). The following analysis applies a “staged design” to accommodate the fact that existing research does not allow to specify every step of the mechanism ex ante (Checkel and Bennett Reference Checkel and Bennett2015). For establishing causality between the steps leading from a policy failure through its politicisation to blame deflection, the case analysis proceeds deductively to test whether entities engage in activities as expected from theory. Implications for policy practice are then assessed in a more inductive way. In accordance with recent calls for more analytic transparency in process tracing research (Fairfield Reference Fairfield2015), parts of the case analysis that contain key pieces of evidence are indented. By showcasing evidence in this way, the analytic account aims to strike a balance between readability and “seeing process tracing in action” (Checkel and Bennett Reference Checkel and Bennett2015).

As for other western political systems, researchers have diagnosed an increased level of elite polarisation in Switzerland (Bochsler et al. Reference Bochsler, Hänggli and Häusermann2015). In fact, the Swiss consensus system is no longer considered an outlier in terms of elite polarisation (Vatter Reference Vatter2008; Sciarini et al. Reference Sciarini, Manuel and Denise2015). As the following analysis reveals, the blame game of the Carlos case can be seen as an example of the increased conflict in the Swiss political system. Despite marked changes affecting the political arena, the Swiss political system is still characterised by many veto points that provide opportunities to block policy change (Immergut Reference Immergut1990; Fischer Reference Fischer2014). Against this background, the Carlos case can be considered a least-likely case. If blame generation by political elites during a policy failure leads to changes in policy practice in the Swiss context, there is good reason to expect that the exposed mechanism is not a “Swiss peculiarity”, but should be present in other democracies as well (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2015).

The following analysis draws on a vast volume of qualitative data gleaned from the comprehensive media coverage by three large Swiss newspapers – NZZ, Tages-Anzeiger and Blick Footnote 2 – and TV reports between August 2013 and September 2014, official reports by enquiry commissions, transcripts of parliamentary debates, expert reports, media analyses and background literature. An additional expert interview was conducted with a specialist in Swiss Juvenile Law in order to clarify the legal conclusions. The data were systematically coded with NVivo 10 and analysed in accordance with qualitative research standards (Blatter and Haverland Reference Blatter and Haverland2012). In a first step, the various interactive steps of the blame game were reconstructed, and from the public accounts of involved actors their strategy profile was inferred. The influence of contextual conditions on incentive structures and strategy choices of involved actors were subsequently captured. The two-step coding strategy allowed to develop a context-sensitive, mechanism-based account of the analysed blame game (Falleti and Lynch Reference Falleti and Lynch2009).

Next, I briefly chronicle the case, followed by a description of the Swiss juvenile justice policy (JJP) in terms of policy distance and visibility, which helps explain the politicisation process and the incentive structures of actors participating in the blame game. This allows me, in a second analytical step, to explain the strategic choices made by participating actors during the blame game and the consequences for policy practice that result therefrom. In a third analytical step, I theorise the context in which the mechanism is likely to unfold.

The Carlos case

The Carlos case concerns a repeat juvenile offender, referred to in the media as “Carlos”, who lived in the city of Zurich and, in 2011, at the age of 16, committed a knife attack that nearly killed another adolescent. The conviction for this knife attack was the last in a series of 34 convictions. Having exhausted all other available sanctions provided for by the JJP to no avail, following an expert opinion, Carlos was placed in a special therapy setting where he lived 24/7 together with a personal custodian. These settings are supposed to reintegrate youth offenders into society and teach them to live a responsible life. The setting was the first successful measure ever tried on Carlos and produced no major incidents for more than a year. In August 2013, Swiss National Television broadcast a film about the lower youth advocate (LYA) directly responsible for Carlos. The film drew heavily on his most prominent case at that time – the therapy setting for Carlos. Although the setting was pictured as a success, the film revealed lots of delicate details such as the Thai boxing training that Carlos attended to learn to accept authority, as well as the monthly costs of the therapy totalling almost 30,000 Swiss francs. Two days later, on August 27, the largest tabloid newspaper in Switzerland ran the story, portraying the setting as a shocking and scandalous example of a soft, “leftish” legal practice and an utter waste of taxpayer money. The front-page story triggered a process of scandalisation during which media outlets attempted to outdo one another to uncover new details about the setting, many of which were factually incorrect or misrepresented. As a reaction to public and media outrage, the cantonal authorities terminated the therapy setting three days later and returned Carlos to a closed institution. After trying to ride out the blame coming from the public, media and political actors for almost two weeks and muzzling the LYA, the latter’s superior, the upper youth advocate and the Minister of Justice (MoJ) of the canton of Zurich, held a press conference to explain their handling of the affair. During the press conference, both officeholders took a tough stance on the LYA and blamed mainly him for the wrong impression transported by the (allegedly unauthorised) film. Although they were at pains to lightheartedly re-frame the issue by portraying the Carlos case as a rare exception, they admitted some minor mistakes concerning cost control and presented some quick fixes. However, their main strategic move was to blame the LYA and to deflect all responsibility while claiming to be utterly uninvolved in the case and uninformed as to the details. The tough stance on the LYA was subsequently reinforced by the MoJ during press interviews, where he explicitly presented himself as a strong leader and continued to blame the LYA, whose dismissal was not necessary only because he was due to retire in any case. Although these moves initially seemed to deflect the blame from politically exposed officeholders, as the media focussed on the LYA and expressed approval for his dismissal, an earlier strategic move – the abrupt termination of the therapy setting – boomeranged on the politically responsible officeholders. Once legal experts had begun to criticise the authorities for terminating the setting due to media and political pressure and portrayed this step as a strategic, but unlawful, move to calm the media, the Swiss Federal Court in February 2014 issued a ruling that the termination was indeed unlawful, prompting the cantonal authorities to immediately reinstate the setting. When the cantonal parliament subsequently discussed the case in April 2014, the MoJ was blamed both for his lack of leadership and his unlawful move by nearly all parties. Put on the spot by the populist stance of the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), which, in Switzerland’s proportional voting system is the strongest party both at the national level and in the canton of Zurich in terms of voter share, all major parties found little to gain in defending and justifying the amply successful JJP. Instead, they concentrated their criticism on the lack of leadership and involvement of the MoJ and the fuzzy governance structures over which he had presided and which he, if not deliberately contrived, had tolerated. In the meantime, pushing responsibility down to the bottom was widely conceived as a cowardly blame-avoidance move. Backed by two commission reports, all parties across the board pressed for organisational changes and tighter and less opaque responsibility structures. However, with the exception of the populist right, the parties opposed a parliamentary enquiry commission, which would have granted the parliament far-reaching rights to further investigate the issue and would have allowed the SVP to protract the blame game. At the national level, the parliament also vetoed a motion submitted by the SVP that had asked the executive to tighten the JJP.

At first glance, the case conveys the impression that institutional rules and practices served as a bulwark against policy change, confirming accounts that suggest that the effects of elite polarisation on policy are mediated by checks and balances. Both at the cantonal and the national level, the SVP was ultimately unsuccessful in using parliamentary instruments to change policy. In the end, an inflated media-induced blame game was worn down by consensus-oriented forces and led merely to some minor organisational adjustments. With the LYA sidelined and the MoJ voted out of office several months later, consequences emanating from the blame game were predominantly of a personal nature.

Case analysis

By looking beyond legislative changes, one can show that organisational and behavioural adjustments made in the course of and in response to the blame game led to considerable changes in policy practice.

Successful blame generation

The JJP deviates from outdated concepts of youth offenders as ordinary criminals whose misdeeds must be punished and atoned. Its primary goals are the protection, education and the (re)integration of young offenders into society (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2011). The JJP is a national policy that has to be implemented and applied by the cantons. Cantonal authorities have ample discretion in designing and applying concrete measures in any given case. In the canton of Zurich, where the Carlos case took place, the upper youth advocacy delegates ample decision-making authority to the LYAs in charge of respective cases. LYAs can choose from the appropriate measures in a problem-oriented way, without being dependent on the authorisation by the senior youth advocacy in each case [Finance Commission of the Canton of Zurich (FIKO) 2014]. There is no comprehensive system of case controlling, which would provide the upper youth advocacy an overview of specific cases, the measures applied in each case, and the running costs thereof. Decision-making authority is clearly situated at the bottom – in the hands of experts who possess ample case knowledge and whose decisionmaking is not driven by electoral concerns. Experts widely agree that the JJP allows for quiet, problem-centred policy practice (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2011). Although in the Carlos case this approach allowed to prescribe a successful therapy setting, the latter was interpreted quite differently by the mass public when the media reported about its details. Political elites were able to frame the expensive therapy setting as a blatant instance of policy failure and accused the politically responsible officeholders for tolerating a soft, “leftish” legal practice and wasting taxpayer money.

A characterisation of the JJP in terms of proximity and visibility explains why political opponents succeeded in politicising the expensive therapy setting. Set within this framework, the JJP appears as a distant-visible policy. Distant-visible policies have the potential “to elicit rapt attention and powerful emotion, but their design features and material effects slip easily from public view because they lack concrete presence in most people’s lives” (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007, 122). Acts of violence committed by juveniles frequently attract public attention and spark calls for a “zero-tolerance” approach to juveniles. In recent years, several aggravated assaults on civilians committed by juveniles elicited public outcry and increased the visibility of the JJP in Switzerland (Urwyler and Nett Reference Urwyler and Nett2012, 20–25). Media coverage increasingly focusses on the particular measures that are applied in concrete cases (Urwyler and Nett Reference Urwyler and Nett2012, 26–27). However, high visibility does not imply that the mass public is properly informed about the functioning of the JJP. In a country like Switzerland, which has a very low juvenile crime rate, the JJP is very distant to most people’s daily lives. Juvenile crime is mostly perceived through the media (Urwyler and Nett Reference Urwyler and Nett2012, 22). Distant policies such as the JJP are considered emblematic by the mass public for the more general stance the state adopts towards specific problems. By placing Carlos in a “luxurious” therapy setting instead of in jail, the JJP appeared to treat youth offenders more as victims than as ordinary criminals, thus adopting a positive connotation of policy targets (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). This allowed parts of the media and the conservative right to portray the state’s approach to fighting crime and ensuring public order as too lax. Key pieces of evidence are as follows:

Public accounts during the first phase of the blame game illustrate how the distance and the visibility of the JJP allowed the conservative right to politicise the expensive therapy setting and generate blame directed at responsible officeholders. Distance allowed the conservative right to portray juvenile crime as a rampant problem which threatened public security (e.g. Blick 2013; Cantonal Parliament of Zurich 2013; NZZ 2013a; Tages-Anzeiger 2013c). Visibility allowed to adopt an “enough is enough” rhetoric which brought the treatment of Carlos in line with earlier instances of soft, “leftish” legal practice which the state could no longer afford (e.g. Cantonal Parliament of Zurich 2013; NZZ 2013b, 2013d; Tages-Anzeiger 2013a).

Blame game dynamics

At the beginning of the blame game, when the special setting was rapidly scandalised by the media and political opponents began to blame responsible officeholders, the latter had a choice set that essentially consisted of two presentational strategies. They could either defend the policy and its successful application in the concrete case by pointing to its success so far, equally high or even higher costs for alternative measures in closed institutions and potentially reduced follow-up costs, or make use of the blame-deflection strategy by shifting blame to lower-ranking actors. As the application of the JJP in the concrete case had been successfully framed by political opponents as an instance of soft, “leftish” legal practice, efforts to defend the costly therapy setting were unlikely to be successful. In fact, the responsible officeholders clearly opted for the blame-deflection strategy. Their early strategic move to terminate the special setting and to return Carlos to a closed institution set the blame game on a predetermined track that was difficult to leave during later phases. As its termination transported the implicit admission of officeholders that the setting was indeed “wrong” and “too expensive”, at the press conference one week later and in subsequent interviews, the responsible officeholders reinforced their early move and deflected blame onto the LYA. Key pieces of evidence are as follows:

Next to their clearly discernible blame-deflection moves (e.g. NZZ 2013c; Tages-Anzeiger 2013b), statements by the upper youth advocate allow to infer that the responsible officeholders had explicitly pondered, but then rejected, the policy-defense strategy. In the face of blame, he and the MoJ had considered the Carlos case to be “not communicable” and the media as “unstoppable” (Ninck Reference Ninck2014).

How did political opponents react to this strategic move by the responsible officeholders? They could by all means have continued to criticise the JJP for its lax conception and treatment of youth offenders, but in order to increase their political power, they tried instead to damage politically responsible officeholders. That is why political opponents increasingly concentrated their criticism on the concrete actions made by responsible officeholders before and during the blame game. Although political opponents, led by the SVP, continued to criticise the policy and asked for it to be tightened, they predominantly blamed the MoJ and the upper youth advocate for the lack of political leadership and the toleration of fuzzy governance structures, which had been exposed by the strategic move of officeholders to deflect blame and assure their lack of involvement and information.

Consequences for policy practice

Political opponents’ claims for tighter leadership, stronger involvement of politically responsible actors and less opaque responsibility structures greatly resonated within the political system and led responsible officeholders to make organisational adaptations. Cantonal authorities were required to implement a rigorous case controlling, requiring them to list the measures applied and the costs thereof for every young offender. Therapy settings as a whole, as well as all the measures contained and recommended by LYAs must now be authorised by the upper youth advocacy. These organisational adaptations made responsibility travel upwards, concentrating it in the hands of politically responsible officeholders. Evidence suggests that these organisational adaptations had important implications for policy practice. After having sidelined the LYA, the MoJ and the upper youth advocate were directly responsible for the treatment of Carlos. Key pieces of evidence are as follows:

In order to avoid (further) blame, they applied the JJP in a stricter way by preventing the reactivation of the therapy setting several times, despite the recommendation of the following youth advocate and a cheaper offer by the company which had organised the setting before its termination (Ninck Reference Ninck2014; see also NZZ 2013e; Tages-Anzeiger 2013d). The setting was reintroduced only after the Swiss Federal Court had issued a ruling that the termination was indeed unlawful.

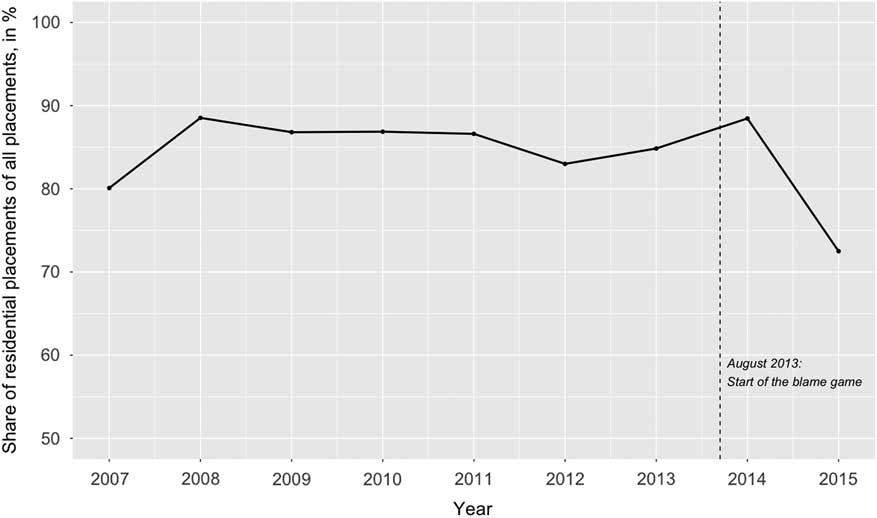

The blame game of the Carlos case did not only lead to behavioural adaptations of actors directly involved in the blame game but also had wider implications for the application of the JJP. The Swiss juvenile crime statistic [Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS) 2016] publishes data on the overall number and type of imposed measures in Switzerland on an annual basis. Unfortunately, these data pose several limitations to meaningful statistical analysis. First, the number of specific blame-attracting measures such as therapy settings cannot be identified, because available data permits us only to differentiate between two types of stationary treatments: placements in closed institutions and residential placements in asylums or in supervised living communities, of which the therapy setting for Carlos is a particular form (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2011). Although these numbers are generally considered accurate (Urwyler and Nett Reference Urwyler and Nett2012), one must bear in mind that cantonal authorities have ample discretion to distinguish and categorise their measures.Footnote 3 Second, with 2015, there is only one data point available in which changes in policy practice can be examined. This is particularly problematic as placements can only be imposed after verdicts have acquired the force of law (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2011). This process can take considerable time, especially in case of an appeal. Data for 2015 may thus underestimate the extent of change to policy practice in response to the Carlos blame game. Finally, the choice of measures may also be influenced by developments that cannot be controlled for with available data.

Despite these data limitations, a look at placement decisions in combination with statements from LYAs suggests that the JJP is now applied in a stricter manner in Switzerland. For severe juvenile offenders whose re-socialisation LYAs deem unlikely or impossible in their usual living environment, the JJP allows to either prescribe a placement in a closed institution or a residential placement. Their considerable costs and the danger that the youth offender escapes or commits additional crimes during treatment make residential placements particularly vulnerable to blame generation. Placements in closed institutions, on the contrary, exhibit a stronger punishment character and come without the risk for officeholders that a youth offender attracts negative coverage by committing additional crimes in the public realm. Key pieces of evidence are as follows:

Figure 1 reveals that from 2007 (first year with available data) until 2014, the percentage share of residential placements of all placements in Switzerland fluctuated only slightly (SD: 2.9 percentage points). In 2015, the first year in which the effect of the Carlos blame game on policy practice should be visible, the share of residential placements decreased by 16 percentage points, thus clearly exceeding the standard deviation for the years 2007–2014. In other words, the Carlos blame game is followed by a marked decline in the prescription of residential placements. The confidence that the identified decline in the prescription of residential placements is actually a reaction to the Carlos blame game is strengthened by statements of those who apply the JJP. Practicing youth advocates indicate that the more critical public assessment of the JJP caused by controversies like the Carlos case and the resulting fear of negative reactions from the media are increasingly influencing the choice of measures (Urwyler and Nett Reference Urwyler and Nett2012; Mez Reference Mez2015).

Figure 1 The development of the share of residential placements of all placements in % in Switzerland, 2007–2015. Source: BFS (2016).

Taken together, the evidence provided here indicates that the blame game of the Carlos case led to considerable changes in policy practice.

The mechanism leading to politicised policy practice and its contextualisation

The blame game covered here exposes a mechanism through which blame generation by political elites during a policy failure leads to changes in policy practice. The mechanism begins with a policy failure that provides a “blaming opportunity” for political opponents. If a policy failure occurs in a distant-visible policy area, political opponents should successfully politicise the failure as mass feedback to blame generation is strong. Confronted with blame from political opponents, responsible officeholders have only very few possibilities to defend the policy, and will therefore choose to deflect blame to lower-ranking officials. This move draws attention and blame to leadership issues and responsibility structures. Responsible officeholders subsequently react by implementing organisational adaptations that make responsibility travel upwards. As the case study has revealed, upward-travelling responsibility is not without consequences, but engenders changes in policy practice on a wider scale. Figure 2 pictures the exposed mechanism in the form of a causal graph (cf. Waldner Reference Waldner2015).

Figure 2 The causal mechanism between policy failures and politicised policy practice.

Responsibility concentration “at the top” makes it more likely that policy practice is driven by the material motives of vote-seeking officeholders who need to protect their goals from blame. An interesting and potentially far-reaching finding that emerged from the analysis is that a blame game of the type covered here cannot only lead to behavioural adaptations by officeholders involved in the blame game but also by officeholders who apply the JJP in other cases. Taken together, these behavioural adaptations constitute what can be termed “politicised policy practice”. The latter describes the application of a policy that is not necessarily driven by case-specific requirements, but by the motivation to provide political opponents with as small a “blaming opportunity” as possible. It is important to note that both politically responsible officeholders and lower-ranking bureaucrats should develop this motivation as both types of actors are likely to face blame during a blame game. Politically responsible officeholders (e.g. ministers of justice in other cantons) may be eager to avoid a comparable blame game developing in their responsibility sphere, and thus opt to tighten strings and exert stronger influence on the choice of measures. Lower-ranking bureaucrats may also respond in an anticipatory manner as they fear blame deflection and, consequently, bring policy practice in line with political pressure – even without the interference of their political superiors (cf. also Lipsky Reference Lipsky2010).

Whether the relationship between blame generation by political elites and politicised policy practice has implications beyond the analysed case depends on the generalisability of the identified mechanism. As Bennett and Checkel state, because “causal mechanisms are operationalized in specific cases, and process-tracing is a within-case method of analysis, generalization can be problematic” (Reference Bennett and Checkel2015b, 13). Whether a mechanism unfolds as expected depends on the presence of contextual conditions. Relevant contextual conditions are those aspects of a setting (e.g. temporal, spatial, institutional) “which allow the mechanism to produce the outcome” (Falleti and Lynch Reference Falleti and Lynch2009, 1152). To identify contextual conditions that enable the unfolding of the mechanism, one can ask whether there was the possibility that an entity might not have engaged in the activity posited by the mechanism. Asking this question automatically shifts one’s analytical focus to the contextual conditions that must be present so that an entity acts in the way implied by the mechanism (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2013). The case analysis revealed four important contextual conditions that provide clues for generalisability and delineate avenues for future research.

Policy characteristics

Policy failures provide “blaming opportunities” for political opponents. Whether the latter actually succeed at politicising the failure and at directing significant blame at responsible officeholders should crucially depend on the distance and visibility of a policy. The case analysis has shown that these policy characteristics have behavioural effects by influencing the public feedback to a policy failure and the investment decisions of political opponents into blame generation (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2014). Distant-visible policies produce particularly strong feedback effects where political and media elites enjoy ample leeway to engage in blame generation, as the policy is salient to the public and the latter depends on elite and media frames for interpretation (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007). Accordingly, possibilities and incentives to engage in blame generation are high. Provided a failure in a distant-visible policy area, we should expect successful blame-generating attempts by political elites.

Resources

Apart from an incentive for blame generation and existing possibilities to do so, political elites must also have adequate resources at their disposal. Access to media, party strength and time allotted for speaking in parliament are important resources for political elites to successfully engage in blame generation. Because of the fact that, with the SVP, the main blame generator in the blame game was unusually strong, one could expect that political elites operating in other contexts do not dispose of adequate resources to generate enough blame pressure. This could be a hasty conclusion, however. Established elites that traditionally relied on more civil and issue-based means in political discourse are now increasingly also engaging in activities such as excessive blame generation (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006). Moreover, radical fringe parties may be able to influence public discourse above their weight by creating a “populist undertow” that entices stronger (and originally more moderate) actors to give in to blame generating temptations for fear of being overtaken by more radical competitors. Finally, the transformation of mass media that is taking place in many western countries provides actors willing to engage in blame generation with a powerful tool. Increasingly, media and parts of the political system pull together, creating a phenomenon commonly referred to as the “tabloidization of political discourse” (Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni2008; Mudde Reference Mudde2013). This provides increasingly large numbers of instances in which political elites find favourable “discursive opportunity structures” for blame generation (Koopmans and Olzak Reference Koopmans and Olzak2004). These developments suggest that also in other western political systems political elites should dispose of enough resources to create significant blame pressure directed at responsible officeholders.

Opportunities to halt a blame game

Whether blame pressure makes responsible officeholders shift blame downwards and address issues of leadership and responsibility in response also depends on the absence of possibilities to terminate the blame game in between. In the Carlos case, the MoJ was part of a collective government and could not be prompted to resign. In other settings, however, heads of government may be able to bring a blame game to a halt by forcing a responsible minister to resign. A timely resignation or demotion of the responsible officeholder may be able to absorb blame and prevent an intensive focus on policy practice, limiting public pressure for organisational adaptations that make responsibility travel upwards. In fact, personal consequences in the course of policy failure-induced blame games may act as an antidote to policy change and thereby protect policy practice from public and political scrutiny. After all, the literature supports the claim that ministerial resignations can be strategically applied to increase government popularity (Dewan and Dowding Reference Dewan and Dowding2005). Personal consequences in the form of demotions and resignations may serve as pressure valves that stymie attacks from opponents, and thereby help calm blame games. Further studies are required to decide whether the identified mechanism unfolds differently or breaks down in settings where timely resignations of politically responsible officeholders are possible.

Decisional discretion

A politicised policy practice can only develop if those involved in the application of the policy have enough decisional discretion to apply the policy in a less blame-attracting way. In the case covered here, officeholders possessed ample leeway in choosing between different policy measures (Aebersold Reference Aebersold2011; FIKO 2014). Without decisional discretion, the motivation to provide political opponents with as small a blaming opportunity as possible should not manifest itself in a politicised policy practice.

The initial effort to identify contextual conditions under which the identified mechanism is most likely to be found has revealed that a policy’s distance and visibility to the mass public, the resources of political elites to engage in blame generation, possibilities to precociously terminate a blame game and decisional discretion in policy practice should be decisive in this regard. Although generalisations from a single case are necessarily limited and contextual conditions, which may be necessary for the mechanism to function in other cases, have not been exhaustively discussed here, a comparative look at the aforementioned contextual conditions suggests that the mechanism should not be highly idiosyncratic, but should be present in other western democracies as well.

Conclusion

This article has exposed and explained a hitherto neglected but highly important mechanism through which politicised policy failures can lead to increasingly politicised policy practice. Policy characteristics in terms of distance and visibility to mass publics, as well as the incentives and resources of political elites to engage in blame generation for a policy failure, explain the dynamics within blame games that, in turn, exact organisational and behavioural changes that help institutionalise a more politicised policy practice.

This article has shown the potential gain of analysing blame games as distinct phenomena that tell us how political systems react and adapt to increased elite polarisation. Importantly, the connection of the complex dynamics within blame games with different types of policy consequences allows to obtain a more complete picture of the ways in which increasing elite polarisation changes western democracies.

This analytic approach has led to the discovery of a link between blame generation in the political sphere on the one hand and policy practice on the other, which promises to produce new insights. For much research studying the interrelations between “politics” and “policy”, “policy” actually comprises policy formulation and adoption but eclipses the day-to-day application of policies already in place. As the findings of this article indicate, any approach that neglects adaptations in policy practice may fail to account for important consequences of increased blame generation that make a huge difference for policy target populations and may damage output legitimacy if policies are applied in ways that negatively influence their effectiveness.

To substantiate this claim, future conceptual and empirical studies are necessary. A research agenda for the study of politicised policy practice in western democracies should consider three important dimensions. First, it should identify policy areas in which incidents frequently become the object of blame generation by political elites. Second, it should categorise policy areas according to the extent of decisional discretion they provide, as the latter represents a prerequisite for applying a policy in less blame-attracting ways. Finally, within particular policy areas, policy measures must be categorised according to their “blameworthiness”. Insights on the concrete empirical manifestations of politicised policy practice in different policy areas and on the diffusion of politicised policy practice across policy areas should quickly enhance our understanding of this phenomenon. By looking at changes in the application of a single policy instrument (placements) and by covering a single combination of policy characteristics (distance and visibility), this article has only made a first step in these regards.

Politicised policy practice may have profound implications for our understanding of the policy orientations of western democracies. For consensus democracies, which are said to have kinder and gentler public policy orientations than majoritarian systems (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012), politicised policy practice is of particular importance. In areas marked by more politicised policy practice, where officeholders apply policies in stricter ways to avoid blame generation, consensus democracies stop being so kind and gentle.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Fritz Sager, Iris Stucki, Jonas Weber, Stefan Wittwer, the three anonymous reviewers and the editors of the Journal of Public Policy for their valuable comments. This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant Number 100018_153111).