Introduction

Many contemporary societal challenges seem to span various policy boundaries. They cross domains – arenas in which issues such as agriculture or defence traditionally have been addressed, steered and governed – and levels – levels of government within an established territory, with interacting authority structures – that range from the global to the local levels (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1991; Berkes Reference Berkes2002; Koppenjan and Klijn Reference Koppenjan and Klijn2004; Briassoulis Reference Briassoulis2011; Peters Reference Peters2015; Boin and Lodge 2016). Climate change, for example, is increasingly addressed from multiple levels – municipal to global – and occupies multiple policy domains – from agriculture to environment. Another example of a crosscutting issue is enduring poverty. To address this challenge, all member states of the UN unanimously adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the implementation of which implies coordination among various domains and levels (Hajer et al. Reference Hajer, Nilsson, Raworth, Bakker, Berkhout, de Boer, Rockström, Ludwig and Kok2015). Traditional policy domains and levels are increasingly considered inadequate to accommodate the complexities and uncertainties inherent to contemporary societal problems (Rittel and Webber Reference Rittel and Webber1973; Kettl Reference Kettl2006; Head Reference Head2008; Candel and Biesbroek Reference Candel and Biesbroek2016). Consequently, policy processes are viewed to progressively crosscut the boundaries of policy domains and levels (Williams Reference Williams2002; Jochim and May Reference Jochim and May2010; May et al. Reference May, Jochim and Pump2013). Policy boundaries are understood here as constructed separations or demarcations used to understand and categorise policy issues (see O’Flynn et al. Reference O’Flynn, Blackman and Halligan2013). Hence, boundaries are an analytical rather than a demarcated empirical construct, which implies that it is not always evident where one domain ends and another begins (Nohrstedt and Weible Reference Nohrstedt and Weible2010, see also discussions in Abbott Reference Abbott1995).

The process of spanning various policy boundaries excites scholarly interest, reflected in attention for related concepts, including boundary-spanning policy regimes (Jochim and May Reference Jochim and May2010), policy integration (Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Davies and van der Grijp2009; Candel and Biesbroek Reference Candel and Biesbroek2016) and horizontal management (Peters Reference Peters2015). This literature often refers to the importance of policy entrepreneurs – understood broadly as (semi) public or private actors undertaking a set of strategies towards certain policy outcomes (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003; Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Vergari2009; Zahariadis and Exadaktylos Reference Zahariadis and Exadaktylos2016) – in the process of crossing policy boundaries. Some authors suggest that policy entrepreneurs strengthen policy support among policy fields by forging linkages among different arenas (May and Winter Reference May and Winter2009). Other studies highlight how policy entrepreneurs adapt arguments from across policy boundaries to strengthen their advocacy efforts and by doing so drive the diffusion of knowledge across horizontal and vertical boundaries (Jones and Jenkins‐Smith Reference Jones and Jenkins‐Smith2009; Pump Reference Pump2011). Peters (Reference Peters2015) demonstrates how strategies of policy entrepreneurs are essential in the politics of working across policy areas, for instance, by creating sufficiently powerful ideas to make policy coordination effective, something that happened with homeland security in the aftermath of 9/11.

Although the literature suggests that policy entrepreneurs play an important role in the crossing of policy boundaries, we have limited understanding of the actual process through which policy entrepreneurs cross boundaries and about the conditions for, and implications of, boundary-crossing. Following the study by Pettigrew (Reference Pettigrew1997), we understand process as a “sequence of individual and collective events, actions, and activities unfolding over time in context”. As such, we argue that the actions of entrepreneurs have implications, which drive policy processes, while simultaneously these actions are embedded in and enabled and constrained by certain contextual conditions (see also Garud et al. Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007; Oborn et al. Reference Oborn, Barrett and Exworthy2011). The outcomes of these processes are generally seen as some form of policy change (Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Vergari2009). Such a processual approach avoids an idiosyncratic study of actions of individuals detached from their environment, and necessitates the analysis of conditions, strategies (i.e. the actions of entrepreneurs) and implications. In this study, we are therefore interested in the conditions under which entrepreneurs engage in crossboundary strategies. For example, a lack of knowledge within government around a particular issue might create a void for policy entrepreneurs to fill. This knowledge is important to be able to co-create an environment in which crossboundary challenges can be addressed with the help of policy entrepreneurs. Moreover, insights in the crossboundary strategies of policy entrepreneurs is of crucial importance as it contributes to understanding and applying tactics to foster crossboundary processes within those contexts. Strategies are understood here as (sets of) activities, manoeuvres or actions of a particular kind for a particular purpose [Grinyer and Spender (1979) cited in Wernham Reference Wernham1985; Zahariadis and Exadaktylos Reference Zahariadis and Exadaktylos2016]. These outputs can include changes in policy paradigms, policy systems or policy instruments and decision-making procedures. Finally, knowledge about the implications of crossboundary strategies of policy entrepreneurs is of interest as it may allow for a better understanding of how strategies contribute to specific policy outcomes. For example, whereas crossboundary strategies may lead to increased support for entrepreneurs’ proposals, it may equally excite opposition.

To deepen our understanding of the crossboundary strategies by policy entrepreneurs, the conditions under which they undertake these strategies and the implications of their actions, we systematically review the large body of policy entrepreneurship literature. The article is structured as follows. First, we explain the methods deployed for undertaking the systematic literature review (second section). We then report the results of our study by presenting a general characterisation of the literature (third section). We then turn to presenting crossboundary strategies in the literature and examining the directions, functions and types of strategies mentioned (fourth section). This is followed by presenting the conditions for crossboundary strategies (fifth section) and the implications of crossboundary strategies (sixth section). Finally, we argue that policy entrepreneurs use several crossboundary strategies, cross various policy boundaries and do so for different functions (seventh section).

Methodology

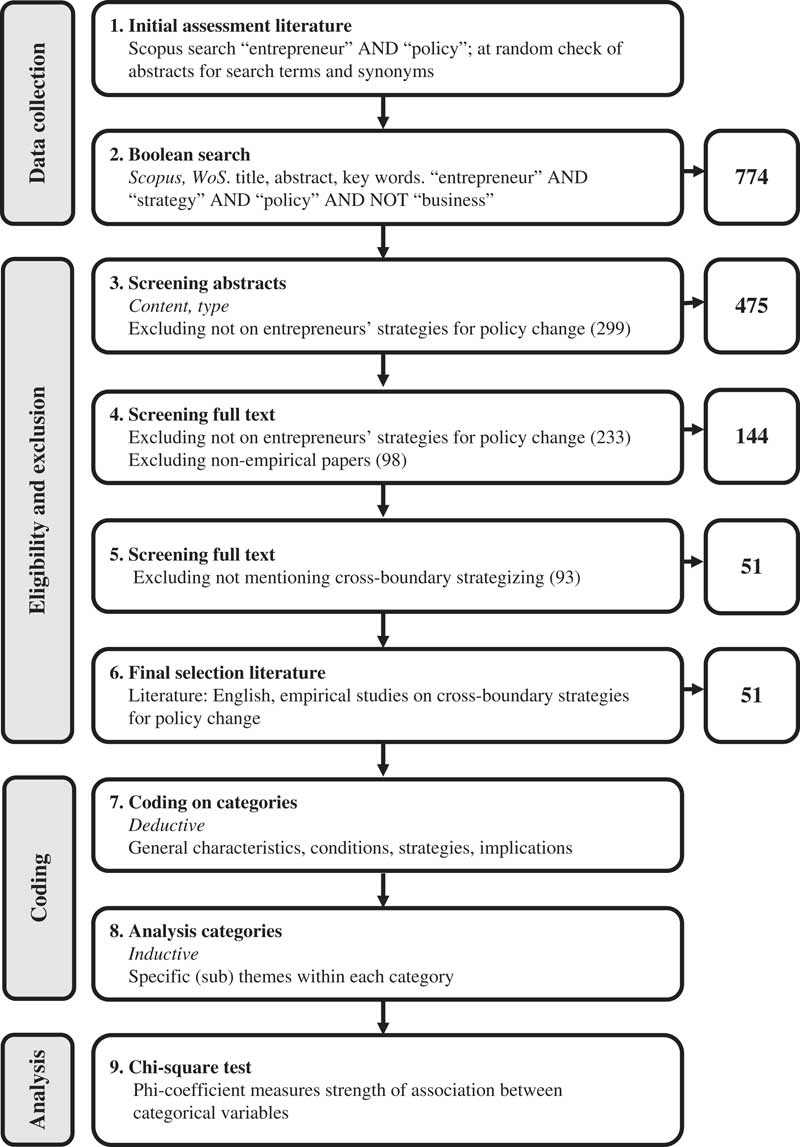

The systematic review is used here to a qualitative approach to the literature that combines a systematic and transparent data collection process and an open and inductive process to analyse data (Petticrew and Roberts Reference Petticrew and Roberts2006; Gough et al. Reference Gough, Oliver and Thomas2012). In this section, we provide an overview of the steps taken in the review process, following the PRISMA protocol for systematic reviews (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2009); see also Figure 1. See annex 1 for more detailed background on the steps taken.

FIGURE 1 The systematic review process.

Data collection

To identify eligible studies, we conducted an electronic search in Scopus and Web of Knowledge, the two largest electronic scientific databases for the social sciences (Falagas et al. Reference Falagas, Pitsouni, Malietzis and Pappas2008). We conducted our search in September 2016, and did not use any year delineation. We selected keyword, title and abstract information as sources for electronic searching. The literature on policy entrepreneurs is extensive, scattered over various disciplines and approaches, and uses different modifiers, including policy, institutional and norm entrepreneur (Petridou Reference Petridou2014). Given the explorative nature of this article and to avoid sampling bias, we include any type of entrepreneurship towards policy change. Consequently, we used a broad search string consisting of “entrepreneur”, “strategy” and “policy”. Articles on business entrepreneurs were excluded, given the focus of this article on policy change. We did so through the Boolean NOT operator, followed by a list of terms associated with business (“corporate”, “enterprise”, “business”). To determine the level of search precision, we sampled 10% of the excluded literature (332 of 3.317 studies) and estimated the amount of falsely excluded studies by screening the abstracts. The exclusion criteria resulted in 1.5% of falsely excluded studies, which we found to be an acceptable percentage. Only English articles were considered for language proficiency reasons. The Boolean search revealed a total of 774 articles for full review.

Eligibility criteria and exclusion of studies

We assessed the abstracts of 774 articles on the basis of the content of the studies: they had to address policy entrepreneurs’ strategies for policy change. Strategies are defined as (sets of) activities, manoeuvres or actions of a particular kind and for a particular purpose, available to the entrepreneur (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1991, Brouwer Reference Brouwer2015). We excluded 299 studies that did not focus on entrepreneurial strategies (e.g. on characteristics of entrepreneurs). As it is impossible to assess all literature on the basis of its abstract, we thereafter screened the full text of the remaining 475 studies, again on the basis of their focus on strategies for policy change. In this round, we excluded 233 studies that were not about policy entrepreneurship or strategies. We also selected on the basis of study design: only empirical articles that used primary data were included, in order to review findings based on direct observations and exclude theoretical and interpretative extrapolations (excluding 93 studies). This resulted in a list of 144 studies suitable for full-text reading and analysis. We conducted a full-text exploration on the selection of 144 studies to select the articles discussing crossboundary strategies. We only included articles that make explicit reference to entrepreneurial strategies across policy boundaries of level and domains. Crossboundary strategies are understood as activities whereby the entrepreneur targets a domain or level different from where he/she is positioned, or links multiple domains or levels. This resulted in 51 relevant studies for review. Although this number may seem rather small, given the wealth of studies on policy entrepreneurship it is an acceptable sample for a review with an explorative character (Intindola et al. Reference Intindola, Weisinger and Gomez2016).

Data abstraction process: the coding of studies

To analyse the qualitative data in the sampled articles, we deployed an interpretive synthesis, to organise concepts identified in the studies into an umbrella theoretical structure by identifying recurring or prominent topics in the literature and summarising main findings under different concepts (Dixon-Woods et al. Reference Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young and Sutton2005). To do so, we designed a data extraction protocol and table to summarise and capture the content of the selected 51 articles (see annex 1). We captured the general and background characteristics of each study (year, author, topic and regional focus, type of entrepreneur). We subsequently coded each study for three categories related to the research question discussed in the introduction. First, we coded for crossboundary strategies: (sets of) activities, manoeuvres or actions of a particular kind and for a particular purpose, whereby the entrepreneur targets a domain or level different from where he/she is positioned, or links multiple domains or levels. Second, we coded for conditions, to be understood as (one of) the premise(s) upon which the appearance, occurrence and/or manifestation of the crossboundary strategising depends. Third, we coded for implications, the consequence(s) following from and directly dependent on the strategies of the entrepreneur.

Using Atlas.ti 7 we conducted a thematic analysis of the evidence to identify prominent or recurring (sub)themes within each category, based on our interpretation of the evidence (Dixon-Woods et al. Reference Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young and Sutton2005). To safeguard the quality of our analysis, we discussed interpretations of categories and (sub)themes among the researchers on a regular basis. Table 1 provides an overview of the different categories (sub)themes and definitions.

TABLE 1 Code categories and (sub)themes with definitions

The variables from the data extraction table were imported in IBM SPSS 22 to enable qualitative and quantitative analysis of the relationship between and co-occurrence of our variables.

Data analysis: the φ-coefficient

To understand the linkages between the different characteristics of strategies – type, direction and function – we conducted a χ 2 test to calculate the φ-coefficient. The φ-coefficient is a measure of the strength of association between two categorical variables, with an interpretation similar to other correlation coefficients. Its value ranges from −1 for a perfect negative association to +1 for a perfect positive association (Field Reference Field2009).

Limitations

Although systematic reviews have great advantages over traditional reviews, there are limitations to be considered. By selecting scientific, peer-reviewed English literature, this study excludes other literature that might have contributed to our understanding of crossboundary entrepreneurial strategies, such as PhD theses or other sources not in the databases used. Although a systematic analysis of the literature limits bias and increases transparency of the process, the thematic analysis of evidence leaves open a certain level of interpretation and is limited in transparency. We have attempted to limit this bias by reporting on our thematic analysis and by discussing interpretation among the author team. Ideally a systematic review would set a benchmark regarding quality appraisal of studies included. However, because of limited reporting on methods and the great variety of quality judgements among different disciplines, trainings and preferences, it is unfeasible to identify best practices (Paterson and Canam Reference Paterson and Canam2001). Moreover, different research questions in the selected articles require different approaches and methods. We accept these as limitations to the research and discuss the implications in the final sections of the article.

Characterising the literature

This section presents the general characteristics of the literature on policy entrepreneurship. The majority of the 51 selected studies is a single-case study (78%) with a few studies comparing multiple cases of policy entrepreneurship in a crossboundary setting. The majority of studies fails to report on study design and methodology entirely (31%); only 18% of the studies contain a separate methods section (i.e. description of case selection, data collection, analysis). The methods used most include interviewing (67%) and document study (47%). Other methods include survey (7%) and observation (7%). Regarding analysis (addressed by only 18% of studies), studies refer mostly to coding (14%); others use statistics (4%) and social network analysis (4%). Figure 2a presents the amount of publications per year and illustrates an increase in studies that cover crossboundary entrepreneurial strategies – in line with a general trend in publications, and publications on policy entrepreneurship (Petridou Reference Petridou2014). Most studies cover topics such as environment and water, security and climate (Figure 2b), which cover issues typically indicated as “wicked” or complex, such as terrorism, water management and climate change adaptation (see, for instance, Jochim and May Reference Jochim and May2010; Peters Reference Peters2015). The types of actors acting as policy entrepreneurs predominantly include political actors, administrative actors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (Figure 2c). The studies included in our analysis predominantly take a supranational focus (32%, of which 26% focusses on the European Union), followed by a national (29%), subnational (26%) and lastly global focus (13%) (Figure 2d). As for national-level studies, 16% of the articles focus on the United States (US) and 6% of the articles discuss policy entrepreneurship in China. Most articles focus on high-income countries (65%), followed by middle-income countries (18%). Very few studies (4%) focus on low-income countries, and some studies focus on a mix (13%). Moreover, it seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon to focus on policy entrepreneurship in lower-income countries (Cairney and Jones Reference Cairney and Jones2016); the majority of studies until 2012 focussed on high-income countries, and from 2012 onwards authors increasingly seem to study policy entrepreneurship in middle- and lower-income countries.

FIGURE 2 (a) Articles published per year; (b) topics covered in articles; (c) actors as entrepreneurs in articles; (d) level targeted by the entrepreneur in articles.

Policy entrepreneurs are predominantly state actors: political (28%) and administration (24%), followed by NGOs (21%). The studies we analyse discuss administration and political actors as policy entrepreneurs mostly in high-income countries, and NGOs as entrepreneurs in low-income countries. In middle-income countries, entrepreneurship is mostly undertaken by political actors and NGOs.

In the following synthesis sections, we present a processual analysis of policy entrepreneurship towards policy change by focussing on crossboundary strategies. To contextualise these strategies, we subsequently focus on the contextual conditions in which crossboundary strategies are embedded, and the contextual implications of crossboundary strategies.

Crossboundary strategies

We now turn to a discussion of the crossboundary strategies mentioned in our sample of the literature. We found a large number of strategies reported in the literature, which we clustered in three main constitutive elements of crossboundary strategies – types of strategies such as framing and coalition-building; directions of strategies: horizontal, vertical or diagonal; and functions of strategies, such as expanding or shifting the issue arena. See Table 2 for an overview of the strengths of associations between directions, functions and strategies.

TABLE 2 Phi-coefficients for strategies, functions and directions

Note: Percentages refer to the amount of cells with an expected count less than 5. As this study is an exploration of the literature, we accepted this limitation, but decided to publish the percentage of cells that have an expected count lower than 5. All cells in grey have an expected count less than 5.

*, **, ***Significant at 0.10, 0.05, 0.01, respectively.

Types of crossboundary strategies

Despite the different topics, contexts and types of actors as policy entrepreneurs, the literature analysed discusses a variety of strategies, which we cluster into five categories: issue promotion, issue framing, coalition-building, manipulating institutions and leading by example.

The first category of crossboundary strategies is issue promotion. Issue promotion refers to the actions of policy entrepreneurs that contribute to issue visibility, including publishing articles, giving speeches, voicing ideas in discussions and advising other stakeholders across boundaries (Font and Subirats Reference Font and Subirats2010; Brouwer and Biermann Reference Brouwer and Biermann2011). This is the strategy most mentioned: 56 times in 28 of the articles. In our sample of articles, issue promotion has a weak positive association with vertical boundary-crossing (0.33), and negatively with horizontal (−0.26) and diagonal boundary-crossing (−0.19), suggesting that policy entrepreneurs promote issues in other levels and domains rather than across horizontal or diagonal boundaries. One example of issue creation in vertical direction is by Boekhorst et al. (Reference Boekhorst, Smits, Yu, Li, Lei and Zhang2010), who show the role of the World Wildlife Fund in promoting integrated river basin management in China. The authors exemplify how local stakeholders promoted an Integrated River Basin Management approach at various regional events and through various media channels and organised a roundtable for stakeholders at the regional level, to expand the issue arena to also include the regional level. We find a weak positive association in the literature between issue promoting and expanding the issue arena (0.12).

A second category of crossboundary strategies is building coalitions. This refers to identifying contacts, building teams and points for cooperation and forming coalitions across the boundaries of levels and/or domains (Mintrom and Norman Reference Mintrom and Vergari2009; Brouwer and Biermann Reference Brouwer and Biermann2011). Coalition-building is mentioned 35 times in 24 articles. This strategy is not significantly associated with any particular direction of boundary-crossing; however, our sample illustrates how policy entrepreneurs deploy coalition-building strategies mostly in relation to vertical boundary-crossing (23). In terms of the function of crossing boundaries, in the literature coalition-building is mostly associated with expanding the issue arena (0.20), and negatively with integrating issue arenas (−0.18). This is illustrated for instance by Douglas et al. (Reference Douglas, Raudla and Hartley2015), who discuss the diffusion of drug courts in the US and report how individuals from the municipal government founded the National Association of Drug Court Professionals to promote the concept of drug courts, share information among different states, develop guiding principles and lobby Congress. The entrepreneurs thereby expanded the issue of drug courts to higher policy levels.

A third category discussed in the selected articles is manipulating or transforming institutions. This includes the actions of policy entrepreneurs to alter the distribution of authority and power and/or transform existing institutions (Meijerink and Huitema Reference Meijerink and Huitema2010; Ackrill et al. Reference Ackrill, Kay and Zahariadis2013; Zahariadis and Exadaktylos Reference Zahariadis and Exadaktylos2016). This strategy is discussed in the literature 22 times in 20 different articles. There is no significant association between institutional transformation and the direction of boundary-crossing. The articles in our sample discuss policy entrepreneurs who deploy institutional manipulation tactics mainly in association with expanding the issue arena (0.21). For example, Newman (Reference Newman2008) explains how national data privacy authorities pushed the EU to adopt data privacy policies by threatening to block trans-border data flows if countries would not accept legislation to protect citizens’ privacy. As such, the national data privacy authorities used the power granted to them as institutions at the national level to influence affairs at the regional level by exerting power over inactive policymakers. Institutional transformation is not associated significantly with any particular direction, meaning that it is used for horizontal, vertical and diagonal boundary-crossing.

The fourth category of crossboundary strategies is issue framing. Framing broadly refers to the use of narratives and stories to make sense of an issue by selecting particular relevant aspects, connecting them into a sensible whole and delineating issue boundaries (Stone Reference Stone2002; Dewulf et al. Reference Dewulf, Craps, Bouwen, Taillieu and Pahl-Wostl2005). This strategy is discussed 25 times in 20 different articles. Framing is linked to idea promotion; the distinction we make is based on the author’s delineation of the action – for example, is the frame or the promotion action described. Framing is in the sample of literature positively associated with horizontal (0.30) and diagonal (0.29) boundary-crossing, and thus policy entrepreneurs mainly frame their issues across different domain boundaries. Through framing, policy entrepreneurs seem to integrate issue arenas, given the weak positive association (0.19). An example includes a study by Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015) on the establishment of a donor-side REDD+ initiative in Norway as a result of two environmental NGOs joining forces and linking their respective issues of concern. In their attempt to convince the government of forest protection, they sent letters to the Prime Minister, and the Ministries of Finance, Foreign Affairs and International Development, wherein they presented rainforest preservation as a solution to climate change. Eventually, and in reaction to this letter, the government of Norway establishes the International Climate and Forest Initiative whose objective is to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) resulting from deforestation in developing countries (Hermansen Reference Hermansen2015).

The fifth and last category of crossboundary strategies we found in the literature is leading by example: undertaking pilot programmes, using an exemplar policy, or testing preferred policy changes at a different policy level or across domain boundaries (Huitema and Meijerink Reference Huitema and Meijerink2009). This strategy is discussed 11 times in nine different articles. Most studies discuss this strategy in relation to vertical boundary-crossing (10), although we found no significant association. Only in one instance is diagonal boundary-crossing discussed: policy entrepreneurs within the local water department use pilot projects to convince other departments at the national level to join their initiative (Uittenbroek et al. Reference Uittenbroek, Janssen-Jansen and Runhaar2016). Leading by example is predominantly discussed in relation to expanding the issue arena (9), although there is no significant association. Meijerink and Huitema (Reference Meijerink and Huitema2010) for instance discuss how policy entrepreneurs use smaller-scale implementation to gain experience with the proposed policy. They highlight how in the Netherlands policy entrepreneurs first introduced “Plan Stork” as a pilot programme before the adoption of the generic “Space for the River” policies to gain experience.

Directions of crossboundary strategies

The literature discusses three directions in which policy entrepreneurs cross policy boundaries: vertical, horizontal and diagonal.

Vertical boundary-crossing refers to policy entrepreneurs deploying strategies that crosscut the boundaries between different policy levels – for example, between the regional EU level and the national level. Vertical strategies occur 114 times in 43 of the articles – some studies mention multiple vertical crossboundary strategies. Vertical boundary-crossing can occur both top-down and bottom-up, although most studies mention strategies towards higher policy levels (83) and far less to lower policy levels (28). In the literature, vertical boundary-crossing is mainly associated with expanding the issue arena (0.18) and with issue promotion (0.33). An example of vertical boundary-crossing through issue promotion is the inclusion of actors in Spain who lodged complaints with the EU to challenge the dominant domestic water agenda in Spain. As a result, the European Commission sent a letter to Spain’s Ministry of Environment to express its concern with Spain’s water management (Font and Subirats Reference Font and Subirats2010).

The second direction, horizontal boundary-crossing, refers to strategies that crosscut the boundaries between administrative policy domains and issue departments within the same policy level. Horizontal strategies occur 27 times in the literature, in 20 different studies. Horizontal boundary-crossing is in the literature mostly associated with strategies of issue framing (0.43). An example includes the work of Diez (Reference Diez2010), who discusses how an alliance of actors working in different federal bureaucratic agencies in Mexico developed arguments to counter homophobia, and convince the government and the public at large of the need of a gay-rights campaign. They did so by means of framing homophobia (1) as an obstacle to fight AIDS to involve the public health sector, and (2) as a human rights issue, thereby prohibiting discrimination against homosexuals. Moreover, horizontal boundary-crossing is significantly associated in the literature with integrating issue arenas (0.30).

The third direction is diagonal boundary-crossing, which refers to the activities that cross both horizontal and vertical boundaries simultaneously. This crossboundary direction is mentioned seven times in seven different articles. The literature moderately associates this direction with framing strategies (0.29), but there is no association with any of the functions of crossing boundaries. An example of diagonal boundary-crossing is provided by Kugelberg et al. (Reference Kugelberg, Jönsson and Yngve2012). They study the process of Slovenian National Food and Nutrition Policy development, and report how the policy entrepreneur within the WHO European Region on public health wanted to engage the Slovenian Ministry of Agriculture in the development of this policy, and proposed to undertake the EU Common Agriculture Policy impact assessment, which would benefit the Ministry. The entrepreneur thereby convinced the Ministry to become engaged in the policy process (Kugelberg et al. Reference Kugelberg, Jönsson and Yngve2012).

Functions of crossboundary strategies

We found that the analysed literature mentions three functions of crossboundary strategies: to expand the issue arena to additional domains and/or levels, shift the issue arena to a different domain or level or integrate an additional issue arena into the original or a new issue arena.

The first function, which occurred most in the literature (105 times in 36 of the articles), is expanding the issue arena by involving an additional level, domain or both. Our findings show that arena expansion is weakly associated with vertical boundary-crossing (0.18). The strategies discussed to expand the issue arena are predominantly issue promotion (0.32). For instance, DeFranco et al. (Reference De Franco, Meyer and Smith2015) report how the UN Special Advisor for Genocide Prevention met with EU key figures to persuade them to prioritise the so-called Responsibility to Protect (R2P), a global political commitment endorsed by all UN member states to prevent genocide, war crimes and ethnic cleansing, in order for the EU to take a more active role.

The second function of crossboundary strategies is for policy entrepreneurs to shift the issue arena from the arena in which it was addressed to a new or different arena at a different domain or level, so as to shift jurisdiction over the issue. This is often referred to in the literature as “venue shopping”: finding an arena that provides the best prospects for achieving one’s preferred policies (Pralle Reference Pralle2003; Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010). This function is discussed 27 times in 16 of the articles. The analysed literature suggests that shifting issue arenas is not associated with any direction or strategy in particular; shifting issue arenas is thus expected to be done through various strategies and in different directions. An example of shifting issue arenas is provided by Perkmann and Spicer (Reference Perkmann and Spicer2007), who discuss how local authorities situated close to European borders promoted the coordination across borders between different municipalities with the European Union, in order for the EU to support transnational cooperation across borders.

The third function of crossboundary strategies is the integration of domains, levels or both into the original issue arena or combine them into a newly established arena. This strategy is discussed 13 times in nine articles. Integration of issue arenas occurs significantly in association with horizontal boundary-crossing (0.30) and through strategies of institutional manipulation (0.20) and framing (0.19). An example is the work of Carter and Jacobs (Reference Carter and Jacobs2014), who explain the emergence of the UK Climate Change and Energy Policy. This study discusses how the UK Secretary of State at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs created a new government institution, the Inter Departmental office for Climate Change (OCC), which they handed over the responsibility for the development of a climate change bill. The OCC united and represented all main departments affecting GHG emissions including environment, energy, business and overseas development (Carter and Jacobs Reference Carter and Jacobs2014). As such, policy entrepreneurs established a new institution to integrate different policy domains and have them address the issue of climate change jointly.

Conditions for crossboundary strategies

The crossboundary strategies policy entrepreneurs employ do not happen in a vacuum. Strategies are embedded in contextual conditions, which codetermine their appearance. The literature refers to several different types of conditions for policy entrepreneurs to engage in crossboundary strategies. Conditions refer to the structural premises that affect the manifestation of crossboundary strategies (Blavoukos and Bourantonis Reference Blavoukos and Bourantonis2011). We clustered these in six main categories.

The first set of conditions for crossboundary strategies refers to institutional overlap, for instance, if the authority over the issue is with different levels and/or domains (Zito Reference Zito2001; Newman Reference Newman2008; Ackrill and Kay Reference Ackrill and Kay2011; Maltby Reference Maltby2013). This condition is mentioned predominantly in relation to EU policy processes whereby authority over certain issues is distributed among different Directorates-General, with nondiscrete and undecided power levels between them. The articles report the functionality of this overlap as it provides opportunities to entrepreneurs to pick the arena most appealing to exert their influence (see also Meijerink and Huitema Reference Meijerink and Huitema2010). This condition is also discussed in relation to vertical boundary-crossing. For instance, the literature presents how in some government systems, such as Canada, different levels of government have become increasingly involved in overlapping areas of public policy. Consequently, policy entrepreneurs may move freely from one level to another in an attempt to find the level at which they can try most advantageously to achieve their desired outcome (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Pralle Reference Pralle2006).

A second condition mentioned in the literature is that the issue is interpreted as requiring a multisector or level approach. If that view is perceived as salient, legitimate and credible, this facilitates entrepreneurs to cross boundaries along similar lines. Rosen and Olsson (Reference Rosen and Olsson2013), for instance, argue that because marine ecosystem management requires an integrated approach – as the drivers of degradation often transcend policy sectors and nation state boundaries – policy entrepreneurs crossed policy domain boundaries.

A third condition mentioned in the literature is the existence of a power vacuum or knowledge gap around an issue. This situation might occur when an issue is newly introduced within a certain policy level or domain, or when uncertainties around an issue lead to a failure in addressing the issue (Palmer Reference Palmer2010). The power vacuum creates an opportunity space for opportunists looking to further their aims (Tomlins Reference Tomlins1997). Policy entrepreneurs might use this window of opportunity (Black and Hwang Reference Black and Hwang2012). The literature also reports how this vacuum might be caused by a process of devolution (Forbes Reference Forbes2012). Decentralised authority might lead to local authorities lacking the knowledge and resources to address the issue in question. These conditions might force local authorities to look for support in terms of finance, knowledge and expertise and may reach out to external experts – such as policy entrepreneurs – for support. The inverse is also possible. When a certain issue is increasingly addressed from the supranational level, policy entrepreneurs might realise that when they are to have an impact they must strategise towards a higher policy level (Verger Reference Verger2012).

Fourth, the literature shows how conditions to cross boundaries may exist when (related) problems enter the political agenda of a level or domain that is different from the issue arena. These “focussing events” offer the opportunity for entrepreneurs to get relevant actors involved. Bjorkdahl (Reference Bjorkdahl2013) exemplifies how Sweden reached for the EU and UN as suitable arenas for the promotion of conflict prevention as their norm would find resonance with the contexts of the regional EU and global UN arena. In the case of the UN, Sweden linked its idea of conflict prevention to the UN doctrine on the R2P. As such Sweden managed to find fertile ground for its notion.

Fifth, conducive conditions at a different level or domain may also be used to exert pressure on the issue arena. Multiple studies mention how policy entrepreneurs refer to policies at higher governmental level to force the issue level to abide by stronger regulations. An example is the work of Diez (Reference Diez2010) discussed earlier that shows how policy entrepreneurs in Mexico battled for the acceptance of homosexuality and referred to international norms of (sexual) human rights to put pressure on the government (Diez Reference Diez2010).

Finally, policy entrepreneurs require various resources including support, finance and knowledge. When these resources are lacking in one issue arena, policy entrepreneurs can use crossboundary strategies to seek additional resources at other levels or domains. In the above-discussed case of acceptance of homosexuals in Mexico, support was mainly lacking. Mexico was contending with high levels of homophobia, and policy entrepreneurs promoting sexual rights had very little room for manoeuvre. Consequently, policy entrepreneurs moved both vertically, making reference to international norms, and horizontally, framing homophobia as a threat to public health, because discrimination and taboo on homosexuality would deter homosexuals from having themselves tested, in order to raise support and put pressure on policymakers (Diez Reference Diez2010).

Implications of crossboundary strategies

Policy entrepreneurs engaging in crossboundary activities do this for various reasons. However, apart from the known motives of increase in resources – money, knowledge, support – or successful policy change there are additional consequences and implications involved in deploying crossboundary strategies. We define implications as the consequences following from and directly dependent on crossboundary strategies. The literature we analysed discusses various implications.

The first implication is that raising awareness and support might also equally raise opposition to the policy entrepreneur’s proposal. As such, crossing boundaries might backfire on the entrepreneur, triggering effective counter-mobilisation, leading to stalemate, stability or delay instead of change (Diez Reference Diez2010; Verger Reference Verger2012; Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2015; Budabin Reference Budabin2015; Orchard and Gillies Reference Orchard and Gillies2015). Orchard and Gillies (Reference Orchard and Gillies2015) discuss the role of the US presidency in refugee protection in the early 20th century. They show that the President aims to raise support for his cause with the international community, in an attempt to sidestep opposition at the domestic level. This exposed his proposal to a range of other states’ interests and constraints, raising opposition and limiting his ability to pursue normative change (Orchard and Gillies Reference Orchard and Gillies2015).

A second implication of crossboundary strategies is that when an entrepreneur assembles institutions from different levels and/or domains to collaborate, this might have implications for governance and leadership. The literature analysed lists several of these implications including competition over leadership (Gorton et al. Reference Gorton, Lowe and Zellei2005; Forbes Reference Forbes2012; Alimi Reference Alimi2015), confusion in management (Newman Reference Newman2008) or reluctance to collaborate from the side of some parties involved (Mukhtarov et al. Reference Mukhtarov, Brock, Janssen and Guignier2013; Uittenbroek et al. Reference Uittenbroek, Janssen-Jansen and Runhaar2016). Uittenbroek et al. (Reference Uittenbroek, Janssen-Jansen and Runhaar2016), for example, discuss how the water department of Philadelphia, USA, for the implementation of the green storm water infrastructure needed to collaborate with other municipal departments. Although the water department reached out, other departments increasingly proved unsure about the value and hence were reluctant to collaborate.

A third frequently reported implication of crossboundary strategies is that involving multiple arenas in a large network might be too cumbersome and overloading for collective policy action. Miskel and Song (Reference Miskel and Song2004), for example, discuss the passing of the Reading First initiative in the US and find that involving multiple arenas in large networks to achieve specific policy innovations might sometimes compromise collective policy action, because too many actors from different levels and domains slowed down the process. The authors suggest small networks or close circles within larger networks to attain the desired policy objectives in a more efficient manner (Miskel and Song Reference Miskel and Song2004).

Fourth, crossing policy boundaries into additional or different arenas may be costly in terms of resources (Pralle Reference Pralle2006; Rosen and Olsson Reference Rosen and Olsson2013; Alimi Reference Alimi2015). Pralle (Reference Pralle2006), for example, discusses the policy process around domestic use of pesticides. She describes how policy entrepreneurs needed additional resources upon diversifying their target arenas to include both national and local levels. Therefore, she concludes, small and resource-poor interest groups have little possibilities of undertaking crossboundary strategies (Pralle Reference Pralle2006). Nevertheless, crossing into additional domains or levels might also raise new resources. Several articles describe how the efforts of entrepreneurs led to an increase in knowledge, expertise, finance and time (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Raudla and Hartley2015; Heinze et al. Reference Heinze, Banaszak‐Holl and Babiak2016).

A fifth and last implication of crossing boundaries reported in the literature is when a policy entrepreneur enters an arena where it has no traditional authority or reputation it may lead to issues regarding trust, legitimacy and authority (Newman Reference Newman2008; Forbes Reference Forbes2012; Arieli and Cohen Reference Arieli and Cohen2013; Mukhtarov et al. Reference Mukhtarov, Brock, Janssen and Guignier2013; Alimi Reference Alimi2015). To illustrate this, Alimi (Reference Alimi2015) discusses the development of a global drug policy and describes how in this process a multistakeholder partnership around the promotion of global drug policy called itself a “global mission” as a strategic line in order to pretend to a certain level of legitimacy to create a global process (Alimi Reference Alimi2015). At the same time, crossing boundaries might also lead to enhanced trust and legitimacy (Arieli and Cohen Reference Arieli and Cohen2013; Budabin Reference Budabin2015; Heinze et al. Reference Heinze, Banaszak‐Holl and Babiak2016). Heinze et al. (Reference Heinze, Banaszak‐Holl and Babiak2016), for example, argue that collaboration across policy boundaries actually fostered trust and legitimacy between the involved institutions.

Discussion

We started this article with the observation that many contemporary challenges transcend the boundaries of policy levels and domains, and that policy entrepreneurs are assumed to play an important role in bridging these boundaries. This systematic review is an exploration of the literature on policy entrepreneurship, to inquire how crossboundary strategies of policy entrepreneurship are covered. We have looked specifically at the directions, functions and types of strategies; the conditions under which policy entrepreneurs engage in crossboundary strategies; and the implications of their actions. In this section, we present four main findings and identify directions for future research.

We find that the literature on policy entrepreneurship pays limited explicit analytical or conceptual attention to crossboundary strategies. An exception is the notion of “venue shopping”, “venue shifting” or “venue manipulation” (Pralle Reference Pralle2006; Boekhorst et al. Reference Boekhorst, Smits, Yu, Li, Lei and Zhang2010; Meijerink and Huitema Reference Meijerink and Huitema2010; Mukhtarov et al. Reference Mukhtarov, Brock, Janssen and Guignier2013; Boasson and Wettestad Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014; Carter and Jacobs Reference Carter and Jacobs2014), an activity related to shifting the decision-making authority to a different arena, which is discussed not only in the policy entrepreneurship literature but also more broadly in relation to the policy process literature, most importantly punctuated equilibrium theory (Pralle Reference Pralle2003; Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010). The increasing number of articles addressing boundary-crossing in our sample might well be aligned to the increasing attention for crosscutting policy issues.

Most studies analysed differ in terms of their set-up (e.g. testing theory versus explaining outcome), adjectives for entrepreneur (e.g. policy, norm, political) and disciplinary focus (e.g. international relations, environmental studies). This is not unique for crossboundary entrepreneurship, as we see similar patterns in the wider entrepreneurship literature (Petridou Reference Petridou2014). However, as a consequence of this variety, our sample of articles is very diverse. Our key elements of boundary-crossing processes – conditions, strategies and implications – function as a framework to organise this wide variety of articles. Through deploying the framework, we identify certain patterns and general observations in the selected literature. We find that the type of crossboundary strategy mentioned most is issue promotion, followed by coalition-building and issue framing. Other reviews on the policy entrepreneurship literature more generally show similar insights by stressing the key role of the dissemination and framing of new ideas, building coalitions, providing examples and manipulating institutions (Mintrom and Vergari 1996; Meijerink and Huitema Reference Meijerink and Huitema2010; Brouwer Reference Brouwer2015; Petridou et al. Reference Petridou, Narbutaité Aflaki and Miles2015). Our review adds to these observations a quantified analysis of the occurrence of different strategies in the literature on policy entrepreneurship, which allows for stronger conclusions. With regard to the direction of strategies, our sample of literature mentions vertical boundary-crossing much more often than horizontal boundary-crossing. It appears that the foremost important function of crossboundary strategies is to expand the issue arena. The literature also demonstrates certain patterns regarding the co-occurrence of types, directions and functions of strategies, of which two are most apparent. First, issue promotion is in the literature predominantly associated with vertical boundary-crossing and expanding issue arenas. Policy entrepreneurs are thus likely to deploy issue promotion strategies to expand the issue arena to different – lower or higher – policy levels. This dynamic shows similarities to the concepts of “uploading” and “downloading” of policy ideas in the policy process literature. For instance, Meijerink and Wiering (Reference Meijerink and Wiering2009) discuss how river basin management as a concept has moved from the level of municipalities and states to a multi-level focus also involving the supranational (European Union) level, and explain this by referring to uploading and downloading of this concept through change agents – in our case policy entrepreneurs (see also Zito Reference Zito2013). Second, framing is associated mostly with horizontal boundary-crossing and with shifting issue arenas, meaning that policy entrepreneurs are likely to use framing strategies to shift the arena where their issue of concern is discussed to a different policy domain. Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010) in their explanation on stability and change in American policy discuss how framing can contribute to the shifting of societal understanding about climate change, thereby shifting the government’s understanding of issues, and subsequently change understanding of the jurisdiction or authority over climate change, for instance, by involving health and environment committees. Studies on entrepreneurship across boundaries might thus capitalise on notions of uploading and downloading and the punctuated equilibrium approach to further their conceptual understanding. At the same time, policy entrepreneurship can enrich other policy process theories by providing a micro-level focus on policy change.

Our research has contextualised policy entrepreneurship by identifying conditions under which policy entrepreneurs are likely to engage in crossboundary action, and implications of their endeavours. With the exception of some attempts, many policy entrepreneurship studies have either embraced contextual conditions by adopting in-depth case study methods, which inevitably reduce possibilities of making inferences beyond the single case, or ignored contextual conditions by creating decontextualised lists of possible strategies. Despite the diversity in articles, we manage to cluster different sets of conditions that influence the strategies and implications, including institutional overlap, issue interpretation, power vacuum, related issues entering a different political agenda, stronger regulations at a different level and lacking resources. Our article is a modest effort in the direction of better understanding under what conditions entrepreneurs engage in crossboundary strategies.

The clusters of implications we distil from the literature include raising opposition, increased competition over leadership, augmented complexity hindering collective action, raised costs and resources, and issues regarding trust, legitimacy and authority. These implications resemble some of the issues acknowledged in the organisational, leadership and collaborations literature, whereby various actors from different sectors, domains or levels are brought together. Leadership studies acknowledge the important role of leadership to cross boundaries, while reporting how these kind of collaborative efforts may run into various difficulties and challenges regarding authority, trust and legitimacy and competing institutional logics (Bäckstrand Reference Bäckstrand2006; Noble and Jones Reference Noble and Jones2006; Crosby and Bryson Reference Crosby and Bryson2010; Head and Alford Reference Head and Alford2015). The literature identifies forging agreement and building trust and legitimacy as important aspects of crossboundary initiatives, but tells us little about the mechanisms through which this can be done. Organisational literature has particular focus on the institutional context in which entrepreneurial strategies are embedded. This is illustrated, for instance, by Khan et al.’s (Reference Khan, Munir and Willmott2007) study on unintended consequences of entrepreneurship. Organisational studies also highlight how entrepreneurship involving a diverse audience might complicate legitimacy and support (Lounsbury and Glynn Reference Lounsbury and Glynn2001; Garud et al. Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007). This research on entrepreneurial strategies is an effort towards providing insight in the micro-level processes of crossing policy boundaries.

Unfortunately, we were unable to find causal or significant connections between conditions, strategies and implications. This is attributable to a lack of significant associations between these variables, which can at least partly be ascribed to what Goggin (Reference Goggin1986) refers to as the “too few cases/too many variables” problem. This demonstrates the richness in variety of different strategies, deployed by different actors, in different contexts. The level of variation in variables outstrips by any order of magnitude the number of cases, meaning there is too much variation in variables to make useful and reliable inferences about the relationship between variables (Goggin Reference Goggin1986). Moreover, the majority of articles we analysed is based on a single-case study. Despite the richness provided through thick description and thorough analysis of the subject matter (Reus-Smit and Snidal Reference Reus-Smit and Snidal2010), this design complicates pronunciation upon the role of contextual conditions and their impact on the selection of strategies and therefore run the risk of having little explanatory range (King et al. Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994). This variation illustrates the current state of the boundary-crossing policy entrepreneurship literature. Bringing some convergence in these debates and identifying key lessons and/or general recommendations for research and practice would require further maturing of the field in terms of types of cases, theories and methods used, as well as a shift from inductive studies to more theory testing types of studies that confirm (or disprove) findings from earlier studies on the valuable strategies, implications and contexts. One possible solution to further our knowledge by identifying linkages between conditions, strategies and implications would be to use methods such as Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) to systematically combine and contrast cases to identify causation, and eliminate other explanatory variables. These methods allow for complex causation by assessing multiple (combinations of) variables by their necessary or sufficient contribution to the phenomenon to be explained (Rihoux and Ragin Reference Rihoux and Ragin2009). Future research applying methods such as QCA could further enhance our understanding of the relationship between conditions, strategies and implications and help determine in which situation policy entrepreneurs will deploy what kind of strategies, and what the implications of their actions will be.

Our findings raise new questions and observations for further investigation. First, entrepreneurs may not always explicitly aim to cross boundaries; it can also be a side effect or strategy to get what they want. Notwithstanding their motivation, however, these activities may contribute to dismantling the boundaries between levels or domains. Although it is beyond the scope of this article, it would be valuable to identify the extent to which policy entrepreneurs are aware of the opportunities and constraints offered by different policy levels and domains. Conditions such as issue interpretation highlight the role of the psychology and motives of entrepreneurs to engage in crossboundary strategies. It is not only the actual context but also the entrepreneur’s perception of that context that informs behaviour. Future research could benefit from linking to the organisational psychology literature, which focusses on the motivations of the actor in context to better understand the conditions and the entrepreneurs’ perceptions of conditions vis-à-vis crossboundary strategies (see, for instance, Palich and Bagby Reference Palich and Bagby1995; Shane et al. Reference Shane, Locke and Collins2003).

Second and related, to investigate the opportunities and possibilities for entrepreneurs to undertake crossboundary activities, it is essential to further look into the characteristics and background of entrepreneurs that undertake crossboundary strategies. Are certain connections or linkages required for entrepreneurs to cross boundaries? To what extent is the power position of the entrepreneur a determinant for successful crossboundary activities? Is access to certain resources required to enable crossboundary strategies? These and related questions are vital to further our comprehension of how entrepreneurs are an integral part of addressing complex societal problems.

Conclusion

The starting point of this article was the interest in the role of policy entrepreneurs in the process of transcending the boundaries of policy levels and domains. Through a systematic review of 51 peer-reviewed studies, we explored how policy entrepreneurs cross multiple policy boundaries by looking at the directions, functions and types of strategies; the conditions under which policy entrepreneurs engage in crossboundary strategies; and the implications of their crossboundary actions. Despite the assumed importance of policy entrepreneurs in the bridging of policy boundaries, the literature on policy entrepreneurship pays limited conceptual attention to crossboundary strategies. On the basis of our systematic review, we conclude that policy entrepreneurs predominantly deploy strategies of issue promotion, issue framing and coalition-building. This is particularly done by crossing vertical boundaries between policy levels, although the literature also mentions the crossing of horizontal boundaries. By crossing boundaries, policy entrepreneurs either expand the issue arena, shift the issue arena or integrate issue arenas across boundaries. We conclude that there are certain types, directions and functions of strategies co-occurring more frequently than others, suggesting that generalisable patterns are emerging. The literature has increasingly addressed contextual conditions and implications of crossboundary entrepreneurship, but we conclude that there is still much to gain from future research that scrutinises the relationship between conditions, strategies and implications. Further research on policy entrepreneurship across boundaries is crucial if we are to address current complex problems including migration, terrorism, climate change and sustainable development. Not only will it increase our understanding of how policy processes can be influenced at the micro-level, it will also offer tools to create a viable context to address complex challenges, and knowledge about the potential implications of crossboundary endeavours to minimise the implications of entrepreneurship that hinder its endeavours.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the previous draft of the article. Replication materials are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/M8NGVF

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000053