Introduction

More than 150 years after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution formally abolished slavery in the United States (US), de facto practices of slavery continue to exist and thrive. Modern-day slavery has a new name – “human trafficking” – and the illicitness of slavery has pushed the act of enslavement into the dark, often allowing the US public to believe that slavery no longer exists.Footnote 1 Although the magnitude of the problem is difficult to determine with great precision given slavery is a covert practice, recent estimates of the scope of contemporary slavery reveal that human trafficking is widespread. The 2016 Global Slavery Index claims that 20.9 million victims is too conservative of an estimate, and that 45.8 million are living in some form of modern slavery globally today (Walk Free Foundation 2014).

Anti-trafficking activists and policymakers have deployed a number of strategies to remedy the potential misconception that slavery does not exist today (US Department of State 2014). However, anti-trafficking activists and state actors have used an inconsistent definition and framing of human trafficking. Lack of agreement on the definition of human trafficking has complicated and, at times, undermined anti-trafficking efforts (Jahic and Finckenauer Reference Kempadoo and Doezema2005).

The historical roots of the discussion of human trafficking can be traced to a concern about the smuggling and “white enslavement” of women for sexual exploitation (Morcom and Schloenhardt 2011; Carr et al. Reference Carr, Milgram, Kim and Warnath2014). Since then, the discussion of human trafficking has grown to encompass a broader picture of subversion, which is neutral with respect to gender and type of exploitation. In conjunction with this broader conceptualisation, human trafficking is now often referred to as slavery. For instance, then President Obama noted that “the outrage, of human trafficking … must be called by its true name—modern slavery”.Footnote 2

The changes in the policy definition leave several important questions to be answered. How is human trafficking currently defined by the public? How did contemporary (mis)understanding of human trafficking develop in the US? And what are the public opinion consequences of this (mis)-understanding? The first half of the article demonstrates that there is confusion around what qualifies as human trafficking. Namely, we show that the definition of human trafficking has evolved over time to become nearly synonymous with slavery; however, programmatic efforts to combat human trafficking have centred on a legacy definition of human trafficking – the smuggling and enslavement of women for sexual exploitation – rather than the current definition of human trafficking. We conduct a qualitative study of a new data set comprising all registered programmatic anti-trafficking efforts in the US. Human trafficking tends to be represented by issue-area elites in a fairly singular manner, creating an archetype of a human trafficking victim as a sexually exploited foreign woman. Trafficking victims who are not women, and neither sexually exploited nor smuggled, are often being overlooked in programming about human trafficking.

It is perhaps not surprising then that there is public misunderstanding of what human trafficking looks like today. The qualitative analysis of nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) is followed with a quantitative analysis leveraging both a nationally representative survey and a laboratory experiment to uncover current public understanding of the human trafficking issue. We administer a knowledge quiz to a nationally representative sample to determine contemporary understanding of the human trafficking issue, and find that human trafficking is also primarily understood by the public as a sex and smuggling issue. This conclusion is validated with a laboratory experiment.

In the second half of the article, we examine the most common ways in which human trafficking has been portrayed in mainstream media over the past five decades, and its public opinion consequences. In studying media coverage on human trafficking over time, we find that human trafficking has been politicised as a forced labour issue, a foreign issue, an immigration issue, a gendered, sex-exploitation issue and a security issue. Although there is a range of messaging strategies used by the media, we find that the media portrayals have been fairly singular. Similar to NGOs, media elites have focused on the sexual exploitation of women, as opposed to other forms of exploitation, as well as the foreignness of the issue area (e.g. human trafficking occurring overseas or among nonnatives within the US). Not surprisingly, the focus of media portrayals is consistent with how the public understands human trafficking and the focus of nongovernmental actors.

Given that the archetype of a human trafficking victim among the public is a sexually exploited, foreign woman, what policy responses would arise if alternative perspectives were more salient? We experimentally explore how exposure to each of the primary messaging frames used in mainstream media translate to public opinion shifts. Namely, we examine whether the salience of human trafficking as a broader exploitation issue in a wide range of sectors, a domestic (as opposed to foreign) issue, an immigration issue, a security issue or a gendered sexual exploitation issue, affects public support for anti-trafficking policy and programmatic response strategies. We find that at present an emphasis on sex trafficking does not elevate concerns about human trafficking or increase policy responsiveness, whereas attention to victims of labour trafficking only slightly elevates policy responsiveness. Stressing domestic victims (e.g. the nonforeignness of human trafficking) and the national security aspects of human trafficking are more powerful in catalysing wider support for anti-trafficking efforts.

The human trafficking policy landscape

Although the term “human trafficking” was introduced over a century ago, its current legal definition is relatively new. How has contemporary dialogue among elite actors shifted over time? In addition, does public understanding of human trafficking reflect a legacy definition of human trafficking or today’s definition of human trafficking? Before diving into these questions, we examine how the definition of human trafficking has evolved over time, and what contemporary trafficking looks like today.

Historical overview of US anti-human trafficking policy

Human trafficking was first introduced in the context of white slavery. The 1904 International Agreement for the Suppression of White Slave TrafficFootnote 3 and the 1910 Convention on White Slave TrafficFootnote 4 both used the term “trafficking” to denote the cross-border movement of white women and girls by force, deceit or drugs for the purposes of commercial sexual exploitation (Doezema 1999). According to the study by Doezema, the 20th century trafficking victim was “a white woman, victim of the animal lusts of the dark races” (Reference Doezema1998, 44). The same year, the US Congress passed the White Slave Traffic Act in 1910, also known as the Mann Act, which sought to maintain the morality and purity of white women by prohibiting women from crossing state lines for immoral purposes and criminalised interracial couples (Saunders and Soderlund Reference Simmons and Lloyd2003; Desyllas Reference Doezema2007).

Many historians argue that the discussion of “white slavery” was triggered by the increased number of women migrants, including prostitutes, from Europe seeking work abroad (Doezema 1999). According to Guy, for many Europeans, “it was inconceivable that their female compatriots would willingly submit to sexual commerce with foreign, racially varied men” (Reference Hilgartner and Bosk1992, 203). In one way or another, it was viewed that these women must have been trapped and victimised. Therefore, European women in foreign bordellos were construed as “white slaves” rather than common prostitutes. The very name “white slavery” can be considered racially charged, as it implied that slavery of white women was of a different and worse sort than “black slavery”, and in America this distinction was explicitly used to downplay the experience of black slaves (Grittner Reference Guy1990). Subsequent anti-immigrant bills were partially propelled by this concern that white women would be subjected to slavery (Doezema Reference Druckman2002; Desyllas Reference Doezema2007).

The issue of human trafficking began to shift slightly in its focus through the course of the 20th century. The 1921 International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Girls omitted reference to the “white slave trade”, and recognised that a victim of trafficking could be of any race, and include male children (but not male adults), thereby expanding the definition of human trafficking.Footnote 5 The 1933 International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women of the Full Age, however, restricted the definition of human trafficking again, focussing on the transfer of women across nation-state borders. A gendered conception of a human trafficking victim along with a typecasting of human trafficking as a smuggling issue involving sexual exploitation was recultivated with the 1933 convention.Footnote 6 However, the 1949 International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others looked to extend the scope of the “white slave” traffic agreements.Footnote 7 Namely, the convention used language that was neutral with regard to race, gender and age, and removed the transnational element of trafficking. Nevertheless, the focus on commercial sexual exploitation remained. The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against WomenFootnote 8 further reaffirmed the linkage between trafficking in women and forced prostitution.

In 2000, the concept of human trafficking was legally broadened to make it a term that is now more synonymous with slavery in general rather than the “white slavery” of women and children across borders for the sex industry (Morcom and Schloenhardt 2011). Today, the definition of human trafficking is not restricted to those of a particular age, gender, race or ethnicity; those who moved across borders; or those exploited in a particular industry. According to the 2000 Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (or the Palermo Protocol), human trafficking is defined as follows:

“Trafficking in persons” shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.Footnote 9

In the same year the Palermo Protocol was passed, the US passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA), the cornerstone of federal human trafficking legislation in the US. TVPA (H.R. 3244) was passed by the US Congress with bipartisan support (371-1 vote in the House and 95-0 vote in the Senate), and signed into public law (P.L. 106-386) on 28 October 2000. This law, along with the Trafficking Victim Protection Reauthorization Act of 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2013, aimed to establish a number of mechanisms to combat human trafficking both domestically and globally (US Department of State 2015). The US used an expansive definition akin to the Palermo Protocol, defining human trafficking as the illicit enslavement of individuals for commercial sex or any labour or services induced by force, fraud or coercion (106th US Congress Reference Desyllas2000). The definition is distinct from human smuggling – the illegal movement of people across state borders – and prostitution. According to today’s definitions and laws, individuals who have neither been smuggled nor sexually exploited can be deemed human trafficking victims.

The passage of TVPA in 2000 allowed for the legal alignment of labour trafficking with sex trafficking for the first time. Since the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, other measures were passed as additional protections against labour abuses. Peonage, or forced labour to pay a debt, existed before the emancipation of American slaves, but became quite prominent in the Southeast after the 13th Amendment freed the slaves (Ransom and Sutch Reference Rieger1972; Berlin Reference Berlin1976; McDonald and McWhiney Reference Morcom and Schloenhardt1980). Antipeonage laws were passed with other reconstruction legislation in 1867 (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Milgram, Kim and Warnath2014). Further legislation (18 U.S.C. § 1584) was passed in 1948, to expand these efforts to include involuntary servitude: “an employer’s coercive conduct intended to compel the labor of another against his or her will” (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Milgram, Kim and Warnath2014, 43).Footnote 10 Although peonage and involuntary servitude would today be considered trafficking offences, until TVPA, these labour abuses were not formally considered as such. The recognition of forced labour as human trafficking officially linked human trafficking with measures to prevent both peonage and involuntary servitude, and also expanded legal authority to combat forced labour beyond the protections that antipeonage and involuntary servitude regulations could provide.Footnote 11

Composition of human trafficking

Unfortunately, precisely establishing human trafficking prevalence by sector and demographic group is challenging for several reasons. First, human trafficking is a crime that renders any activity illicit, and hence hidden (Gozdziak and Collett Reference Gulati2005). Second, accurately identifying human trafficking victims is difficult because of ethical concerns surrounding victim interviews, the tendency of victims to be members of hidden populations (e.g. sex workers, undocumented immigrants) and disagreements with regard to estimating human trafficking (Danailova-Trainor and Laczko Reference McCombs2010; Gould Reference Grittner2010). Measurement problems abound, with researchers and service providers disagreeing on how to determine what labour abuse cases count as human trafficking (Free the Slaves Reference Gozdziak and Collett2004; Laczko Reference McCallum2007; Zhang Reference Zhang2012). For instance, if a person is being partially paid and verbally abused such that the person feels unable to leave his/her job, should s/he be deemed a human trafficking victim? Third, to the extent that there is disagreement on the definition of human trafficking between communities, reporting will not reflect a uniform legal definition.

However, although precise measurement of human trafficking is difficult, extant research on human trafficking prevalence reveals that the number of human trafficking victims who are not sex trafficking victims is significant. Some of the best estimates of the frequency of human trafficking and the identity of victims suggest that subjecting individuals to sex trafficking is not the dominant form of the crime. The International Labour Organization (Reference Kandathil2012) estimates that out of 20.9 million victims worldwide in 2012, 22% are victims of sexual exploitation, and hence victims of sex trafficking, and 68% are exploited in activities such as agriculture, construction, domestic work and manufacture, which are cases of labour trafficking.Footnote 12 , Footnote 13

A review of US anti-human trafficking policy suggests that human trafficking legally evolved from a gendered issue of white women smuggled into sexual slavery to a broader issue that affects a diverse set of people being exploited for nonsexual exploitation in addition to sexual exploitation. Although there are measurement challenges, there is consensus that a nontrivial number of human trafficking victims are not sexually exploited women, raising the concern that an important subset of human trafficking cases are being neglected if a disproportionate focus of anti-trafficking activities focus on sex trafficking. In the next section, we scrutinise the programmatic efforts of NGOs combating trafficking to assess whether the legacy of human trafficking as sex trafficking remains a significant feature of how anti-trafficking efforts are approached.

Elite representation, public perceptions and (mis)conceptions of human trafficking

The history of human trafficking and anti-trafficking efforts indicates how human trafficking is a cross-cutting issue and related to prostitution, immigration, labour and organised crime. Because human trafficking is such a multidimensional problem, what qualifies as human trafficking and the critical aspects of the problem can be framed and described in varied ways. In addition, with policy issues such as human trafficking, the public understands them through the framing that policy elites offer (Entman Reference Feingold1993). Informational frames allow for individuals to understand and interpret an issue (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Druckman Reference Entman2004; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). Descriptions of policies through different frames or messaging strategies can change how individuals interpret the policy issue, but also how willing individuals are to support various policies around that issue (Druckman Reference Druckman and Kam2001). This is particularly true for policies related to crime (Zaller Reference Zaller1992; McCombs Reference McEntire, Leiby and Krain2004; Baum and Potter Reference Baum and Potter2008). Responses to a criminal activity such as human trafficking are especially sensitive to the framing strategy used to describe these activities because most individuals have little direct experience with criminal activities (Surrette 1992; Potter and Kappeler Reference Raymond and Hughes1998).

Political elites can use frames in a strategic manner, using them to sway the public on socio-political issues, and there has been documentation that organisations often frame issues to gain attention and increase potential for action (Klandermans Reference Laczko1988). Non-NGOs can be considered a part of the “policy elite” (Brysk Reference Brysk1993; Hertel 2006; Becker Reference Becker2012; Wong Reference Wong2012; McEntire et al. 2015), as they can set the agenda, and guide the course of the national conversation on policy issues (Hilgartner and Bosk Reference Jahic and Finckenauer1988; Chandler Reference Chandler2001). Specifically, NGOs can use targeted messages to change both public opinion and to influence policy (Kingdon Reference Koettl1984; Burstein Reference Burstein1991), particularly NGOs working on human rights issues (McEntire et al. 2015). In covering human trafficking, which can be considered a human rights issue, media has often turned to human trafficking organisations for information. For example, Gulati (Reference Hertel2011) documents that nearly 30% of newspaper articles in his sample cited NGOs and activists as their sources and that anti-trafficking organisations triggered about 14% of the articles through releasing reports or discussing government reports.

The following analyses examine what policy elites involved in combating human trafficking (nongovernmental actors) have focussed on in their anti-trafficking efforts, and demonstrate that public understanding of human trafficking mirrors those efforts. First, we introduce an original data set of organisations that work on combatting human trafficking, and show that registered anti-human trafficking organisations that operate and address human trafficking in the US demonstrate a clear and consistent focus on the foreignness of the human trafficking problem (e.g. human trafficking victims involve nonnative individuals) and on the sexual exploitation of women. Second, we leverage the following two studies to underscore that public opinion on human trafficking reflects the singular focus of policy elites on the smuggling of sexually exploited women: (1) a knowledge quiz from a nationally representative sample; and (2) an experiment that assesses whether a description of a human trafficking victim is actually categorised as such within a laboratory study. The two studies confirm what the study of the NGO landscape in the US suggests – there is a misperception that human trafficking is equivalent to sex trafficking and that smuggling is intimately intertwined with the human trafficking issue.

Study 1: NGOs on human trafficking

Procedures and design

We created a database of 294 NGOs registered as having an anti-trafficking mission with the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) by November 2015.Footnote 14 We classified each organisation based on the type of trafficking on which it focuses (sex or labour). The coding was based upon (1) organisations’ self-reports on their target population and mission in their registration process; and (2) information collected from each organisation’s website and direct correspondence with the organisation.Footnote 15 Finally, we collected data on the year the organisation was founded from the organisation’s website or through direct personal contact if the date was not listed. Founding dates ranged from 1849 to 2015. Out of the 294 organisations, 250 organisations were successfully coded.Footnote 16

Results

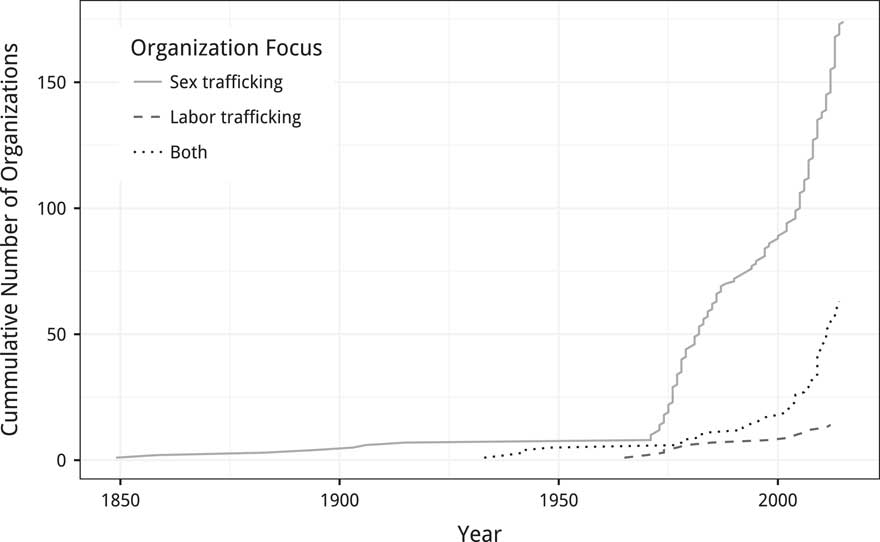

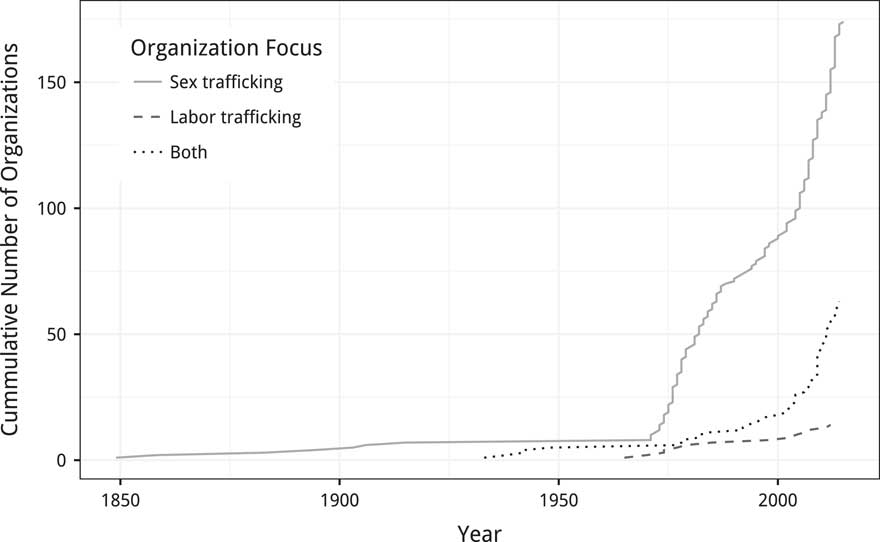

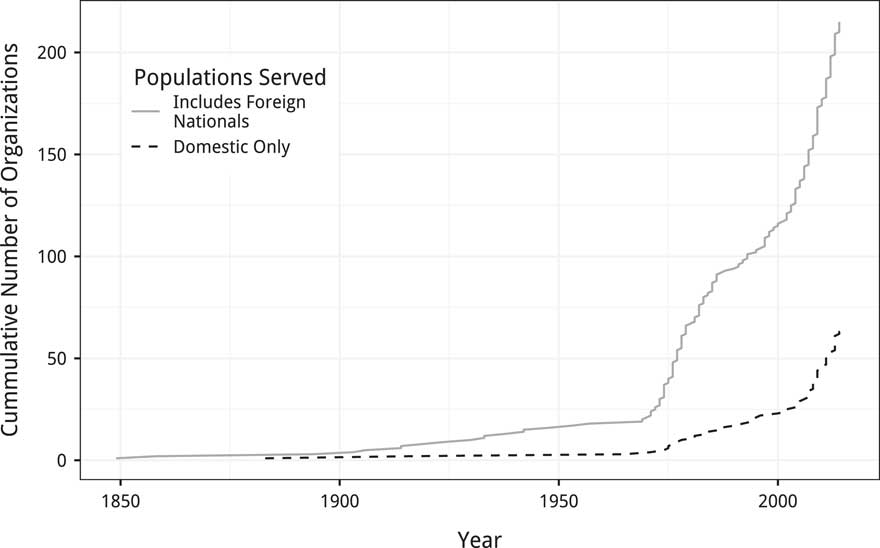

Figure 1 depicts the cumulative number of organisations that were founded each year, based on the type of trafficking the organisations focus on. We consider organisations that focus on sex trafficking exclusively, both sex and labour trafficking and labour trafficking exclusively. Throughout the history of nonprofit work on human trafficking, the majority of anti-trafficking organisations have focussed exclusively on sex trafficking. Before 1970, there were only seven organisations focussing only on sex trafficking. However, after 1970, an average of 3.8 organisations focussing on sex trafficking exclusively were founded each year, resulting in 173 organisations focussing on sex trafficking exclusively. In contrast, a total of 63 organisations were founded that focus on both sex and labour trafficking. These organisations began to increase in number in the 1970s as well (only five were founded before 1970), but the growth of organisations focussing on both sex and labour trafficking (0.3 organisations a year) was more modest than the growth of organisations focussing on sex trafficking alone. Even after 2000, the year in which federal legislation on human trafficking passed and the point of the most visible increase in organisations focussing on human trafficking, organisations that explicitly tackle labour trafficking were founded at a rate of only one every three years (0.4 a year). Finally, organisations focussing on labour trafficking alone are relatively rare. There are only 14 organisations in the registry that focus on labour trafficking alone. Five of these organisations were founded in the 1970s and six were founded after 2000.

Figure 1 Nongovernmental human trafficking organisations.

Figure 2 graphs the cumulative number of organisations based on whether the organisation focuses on foreign-born populations or not. We use this as a proxy for whether organisations focus on international (foreign nationals) or domestic (US citizens and legal permanent residents) trafficking, as organisations that focus exclusively on domestic populations can be identified; however, organisations that focus on foreign nationals may also serve domestic populations. Of the organisations in the registry, foreign nationals are the focus of 215 organisations. In contrast, 64 organisations were founded that focus exclusively on domestic trafficking in the same period. The number of organisations with a domestic focus start to increase more consistently after 2000, although organisations aiding foreign-born individuals have been increasing steadily since the 1970s. The average number of new organisations that focus on domestic trafficking before 2000 is 0.44 per year, whereas after 2000 it is 2.73 per year. This is still notably lower than the entire period average for organisations that serve foreign nationals, which is 2.28 organisations founded per year before 2000 and 6.60 per year in the period after 2000.

Figure 2 Nongovernmental human trafficking organisations.

As a whole, organisations founded to combat human trafficking primarily focus on sex trafficking. One possibility is to conclude that these data reflect that a greater portion of trafficking victims are trafficked for sex, creating a higher demand for organisations focussing exclusively on sex trafficking. However, as we note above, basic supply and demand do not necessarily explain the almost singular focus on sex trafficking rather than labour trafficking. Similarly, estimates of international and domestic trafficking suggest an overrepresentation of international-focussed organisations. The US Department of Justice estimates that there are between 14,500 and 17,000 human trafficking victims in the US each year (DOJ et al. Reference Druckman2006). Estimates for US citizens being trafficked are much more tenuous (Clawson et al. Reference Clawson, Dutch, Solomon and Grace2009). However, of the victims identified in 2015 by Polaris, 8,676 were US citizens and 7,885 were foreign nationals (Polaris Reference Ransom and Sutch2016).

The observation that sex trafficking and smuggling cases makes up the bulk of anti-trafficking programmatic efforts within the US perhaps reflects the history of how human trafficking has been defined. The focal areas of anti-trafficking organisations mirror contents of early policy discussions and definitions of human trafficking that singularly focus on the smuggling of women for sexual slavery (Feingold Reference Gould2005; Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman2005). If many of the NGO actors in the space continue to have a narrow definition of human trafficking, subsequent policy efforts and public discussions on human trafficking will probably neglect domestic trafficking and important aspects of human trafficking beyond sexual slavery.

Study 2 (online survey): human trafficking knowledge quiz

Procedures and design

A nationally representative online survey was administered in March 2015 through Survey Sampling International (SSI) to 2,135 people.Footnote 17 The median age in the sample is 47.3, 51% of the sample is female, 76% of the sample is white and 74% identify with a religion. The median household has an income in the $50,000–$74,999 range. In all, 37.5% of the sample identifies more with the Democrat party and 40.1% of the sample identifies more with the Republican party.Footnote 18 A summary of the demographic characteristics of the study sample can be found in Table B.1 in Online Appendix B.Footnote 19

Each respondent completed a battery of nine true/false questions to gauge the level of information they have on the issue of human trafficking. The full knowledge quiz battery of the questionnaire is provided in Online Appendix C. In this way, we can look to see whether the typical American’s understanding of human trafficking matches reality.

Results

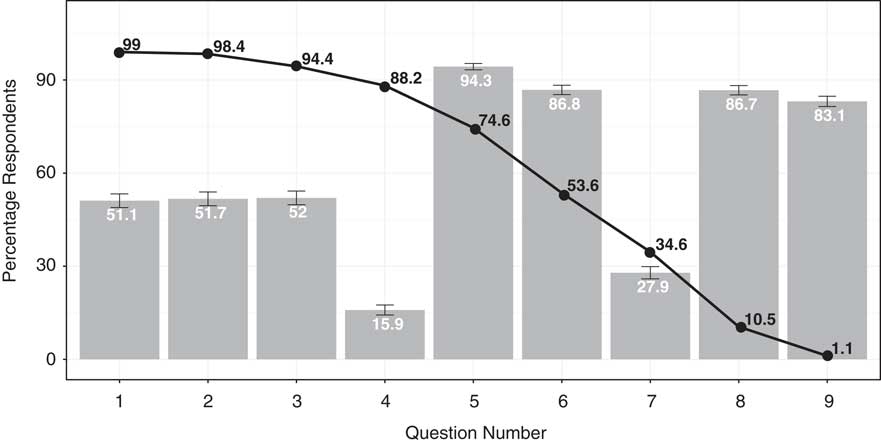

Figure 3 displays two pieces of information: (1) the share of respondents who correctly answered each individual question; and (2) the share of respondents who answered a particular number of questions correctly (a cumulative percentage). Over half of the sample answered at least five out of the nine questions correctly. There are four questions that nearly the entire sample answered correctly (over 83%), which are enumerated below:

∙ Question 5: Human trafficking is a form of slavery. (True)Footnote 20

∙ Question 6: Pimping a minor is sex trafficking. (True)

∙ Question 8: You can’t be trafficked if you knowingly entered the US illegally. (False)

∙ Question 9: You can’t be trafficked if you knowingly engaged in prostitution. (False)

Figure 3 Correct responses to human trafficking quiz. Note: The bar graph depicts the percentage of respondents who correctly answered each question. The line graph denotes the cumulative percentage of respondents who answered each number of questions correctly.

For the most part, the general population is relatively well-versed on issues of human trafficking involving sex work, which comports with our finding that sex trafficking has dominated print media and NGOs activity. Given that human trafficking has been linked with smuggling and foreigners, it is also not surprising that the average American correctly believes that it is possible for an illegal immigrant to be a human trafficking victim. In addition, the notion that human trafficking is a form of slavery has caught on in the mind of the average citizen.

However, there are two questions that respondents generally answer incorrectly. Those questions are as follows:

∙Question 4: The vast majority of human trafficking victims are females. (False)

∙Question 7: Human trafficking is another word for smuggling. (False)

The first notable misunderstanding – that the majority of human trafficking victims are women (Question 4) – is unsurprising given our earlier policy and NGO analyses. Legislation and reporting on sex trafficking and an emphasis on women as victims results in a public that believes that most victims of human trafficking are women. The second pervasive misunderstanding (Question 7) is consistent with a focus on foreign nationals seen in our analyses of anti-trafficking organisations and a legacy definition of human trafficking emphasising illegal cross-border movement. The association of entry into the country through illegal means with immigrants who have been trafficked likely leads to a misunderstanding about the distinctions between human trafficking and smuggling.

Study 3 (lab experiment): (mis)categorising victims

Procedures and design

We further examine how human trafficking is understood by executing a study in a behavioural lab of a major research university to assess general perceptions around human trafficking. The study was conducted between 8 and 16 November 2012, and 436 individuals participated. Summary statistics of the student sample for a range of demographic characteristics – age, gender, income, race/ethnicity, religiosity, interest in political news, party identification and political knowledge – can be found in Table D.1 in Online Appendix D.Footnote 21 As this study targeted college students, 93% of the sample are between the ages of 18 and 22 years. The average respondent answered five out of eight political knowledge questions correctly, 71% of our study sample are white, 80% identify with a religious faith and the median respondent has a household income of $150,000 or more. The sample is diverse with respect to gender (51% female) and party identification (41.84% identifies more with the Republican Party and 51.26% identifies more with the Democratic Party).

Although a student population is not necessarily nationally representative, experimental studies from a student sample can still be illuminating and are not inherently a problem for experimental research (Druckman and Kam Reference Farrell and Fahy2011). If treatment effects are not moderated by student and nonstudent status (e.g. there are homogeneous treatment effects), then the results of our convenience student sample are generalisable to nonstudent populations. Our nationally representative sample described in Study 2 indicated that human trafficking knowledge is not moderated by age, and, to our knowledge, there is no theoretical reason why a human trafficking cue should have a stronger impact on undergraduate students compared with nonstudents.Footnote 22 Moreover, we replicated this study with a nationally representative sample in another country context, and found nearly identical effects.Footnote 23

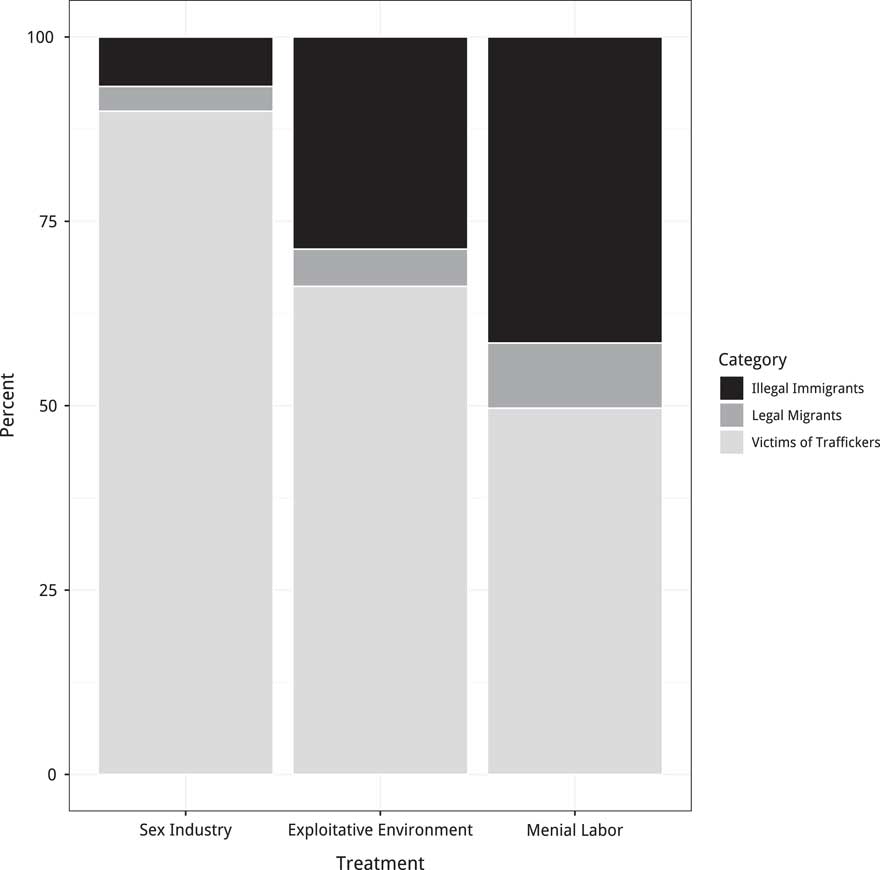

To assess whether a single industry dominates people’s perception about when human trafficking occurs, we exogenously manipulated the context in which the human trafficking victim is working. Namely, respondents were asked to read one of three variations of a statement, where each manipulation is indicated in brackets: “As you may know, many persons who pay agents to be transported from one country to another end up being deceived and coerced to take work in [the sex industry/exploitative environments/menial labor] when they reach their destination”. The statement was immediately followed by the question “How would you describe these individuals?” (response options: “Illegal immigrants”, “Legal migrants”, “Victims of traffickers” and “Other”). All three variations would qualify as a description of a potential human trafficking victim, as the type of work is not part of the definition of trafficking, whereas coercion is integral to the definition. To ensure that random assignment of the treatment conditions were successful, we confirm that there is balance across treatment conditions for each of our demographic variables noted above (see Table D.2 in Online Appendix D).

Results

When the description of the foreign human trafficking victim involves the sex industry, 89.9% correctly categorise the victim as a human trafficking victim, 6.7% describe the victim as an illegal immigrant and 3.4% categorise the victim as a legal migrant. In contrast, when the description of the victim mentions “exploitative environments” rather than the sex industry, only 66.2% of our sample categorise the victim as a human trafficking victim, and 28.8 and 5.0% categorise the victim as an illegal immigrant and legal migrant, respectively. Finally, when the word “exploitative” is removed and the nature of the work is “menial labour,” the share of individuals who categorise the victim as a human trafficking victim drops to 49.7%. Moreover, the victims described in the provided statement are more likely to be viewed as illegal immigrants (41.5%) or legal migrants (8.8%). The results of the study are summarised in Figure 4, and we find that the labor industry significantly impacts the extent to which victims are identified as human trafficking victims, first and foremost (χ 2=57.65, p<0.001).Footnote 24 This result shows that people strongly link sex trafficking with human trafficking, and the sex trade cues individuals into thinking that a particular victim is indeed a human trafficking victim. As such, human trafficking victims who are not exploited in the sex industry are more likely to be mis-categorised, and not considered human trafficking victims. Moreover, when a respondent does not view the foreign individuals as a human trafficking victim, the sense that the statement describes “illegal immigrants” is consistently higher than the sense that the statement describes “legal migrants”. This provides evidence that when an individual thinks about foreign victims, there is a sense that the smuggling of “illegal” immigrants dominates legal movement. Note that there is nothing illegal about using a third-party agency to assist with movement (e.g. a travel agency or a work placement agency). This comports with what we find in the knowledge quiz study discussed above: sex trafficking is perceived to be a problem that mostly affects women, and smuggling is intertwined with people’s understanding of the human trafficking process.

Figure 4 Categorising victims by industry. Note: The bar graph depicts the percentage of respondents who identified the victim population as illegal immigrants, legal migrants, or victims of traffickers by each of the three treatment conditions.

The evolution of human trafficking messaging strategies and implications for public opinion

While the previous section demonstrated that both policy elites and the public reflect a limited view of trafficking, what might a fuller description of human trafficking look like? In addition, how would support for combating human trafficking and anti-trafficking policy be affected if alternative human trafficking messaging strategies were used? We have found that there is a tendency to conflate sex trafficking with human trafficking among NGOs and the public. Does the overemphasis on sex trafficking and smuggling mean undermobilisation of the public around the issue? Or, as some suggest, might a focus on cross-border sex trafficking effectively mobilise the public around the issue? We are interested not only in the impacts of the different messages on concern for human trafficking, but also on how the different messages affect an individual’s propensity to act against human trafficking and support future government anti-trafficking policies.

First, we use a comprehensive corpus of newspaper articles on human trafficking to document the content of public information of human trafficking and the main context of the descriptions of human trafficking. As argued in Farrell and Fahy, “media representations of human trafficking problems, both in response to and in furtherance of claims makers at different stages, illustrate publicly accepted definitions of and solutions to the problem” (2009, 618). Tracing the primary topics of media discussions on human trafficking allows us to follow the core attributes of how human trafficking is represented to, and hence understood by, the public.

We then use a survey experiment to determine what, if any, effect a broader messaging strategy might have on garnering support for anti-trafficking efforts and policies. Despite the broad focus on sex trafficking we identified above, our study concludes that shining a light on sex trafficking and the smuggling of foreign nationals does not catalyse support for public policies beyond what a generic message on human trafficking accomplishes, and that anti-trafficking efforts might be better served by broadening the focus, highlighting the security threats that human trafficking poses and emphasising that it is also a domestic problem affecting US citizens.

Study 1: mass media coverage on human trafficking

Procedures and design

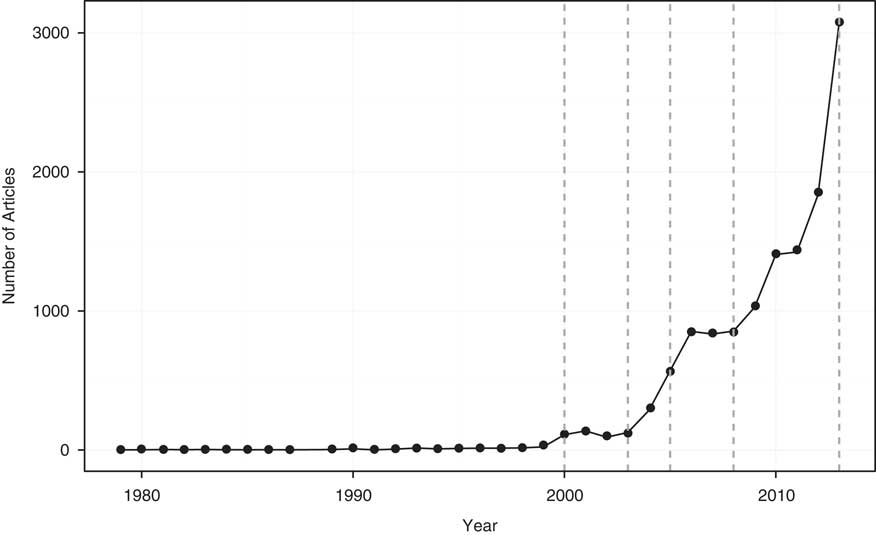

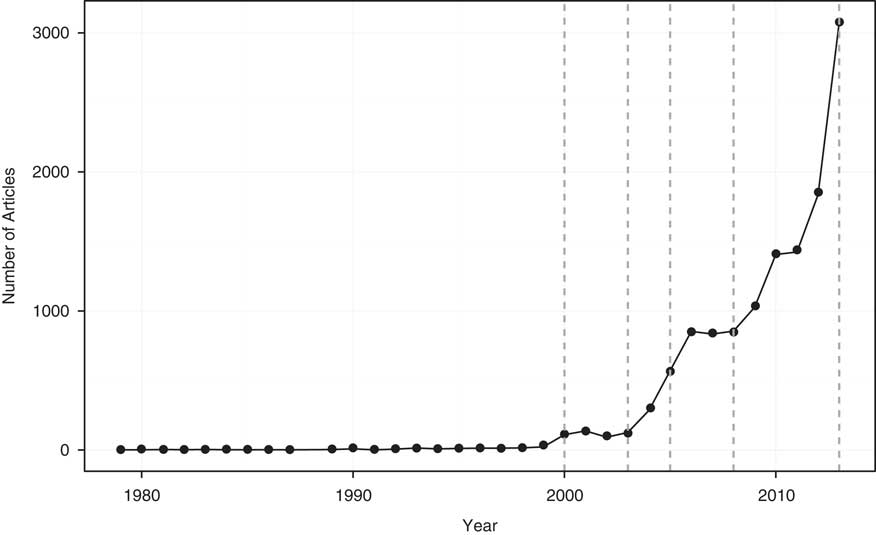

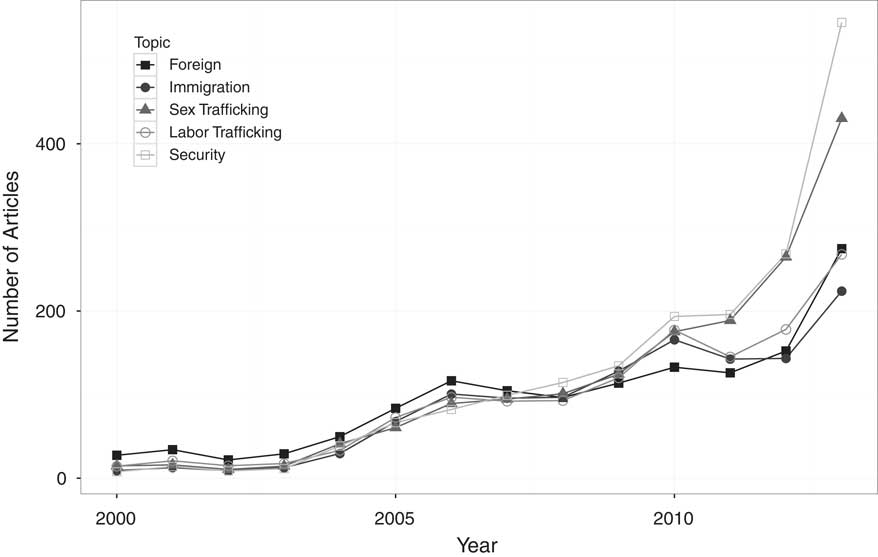

What are the dominant messaging frames used to inform the public about human trafficking? Here, we investigate the possible ways that the media might represent human trafficking to the public. To that end, we compiled a corpus of 12,763 newspaper articles published in the US from 1979 through 2013. The articles were obtained from the search query “human trafficking” on LexisNexis, and the search was constrained to articles published in newspapers in the US. The search extended back through 1967, but no newspaper articles were found before 1979.Footnote 25 Figure 5 shows the distribution of the number of newspaper articles by the year they were published. Between 1979 and 1989, there were very few articles published about human trafficking – an average of 1.8 articles per year. The number of articles between 1990 and 1994 increased slightly to 7.4 articles a year, and doubled between 1995 and 1999. In the next decade, the number of newspaper articles published about human trafficking increased exponentially. While in 2000 there were 110 articles, in 2005 there were 870, and in 2013 there were 3,077 articles published about human trafficking. The sparse level of articles about human trafficking before 2000 and the immediate growth in articles about human trafficking after 2000 is consistent with other investigations into human trafficking conducted between 1990 and 2000 (Farrell and Fahy 2009; Gulati Reference Hertel2011).

Figure 5 Number of articles on human trafficking in United States (US) print media. Note: The dashed lines reflect when the first US legislation on human trafficking, Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, was passed (2000), and when this legislation was reauthorised – 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2013.

The increase in the level of public discourse follows the timing of public policy activity. The first slight increase occurs in 2000, which is when the Palermo Protocol and TVPA were established. Each renewal of TVPA was also accompanied with a jump in the amount of articles on human trafficking in the US. As such, the date in which TVPA was passed (2000) and the dates of each renewal (2003, 2006, 2008 and 2013) are indicated on the graph with a dashed vertical line in Figure 5. Because the formal legal definition of human trafficking in the US was established in 2000, and there is an exponential increase in the articles on human trafficking after 1999, we focus our remaining analysis on the articles released in 2000 and thereafter.Footnote 26

To determine the content of the articles, we used Latent Direchlet Allocation (LDA), a topic modelling algorithm that allows us to divide the articles based on a selected number of topics (Blei et al. Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003). LDA allows a corpus to be divided into different groups or topics, and uses individual word counts to serve as an attribute of one of the document topics.Footnote 27 The topic model produces five substantive topics. These are listed in Table 1, along with the words that form each topic.Footnote 28

Table 1 Topics

Results

Figure 6 presents the results of this analysis. The proportion of each topic is averaged for each year, and then multiplied by the number of articles in each year. As such, each data point represents the average number of the articles that reflect each individual topic by year. Initially, the conversation around human trafficking was dominated by discussions on foreignness of human trafficking. Articles about immigration, sex and labour trafficking are equally represented as secondary issues, and the fewest number of articles discuss security. By 2008, articles focussing on security began to dominate the discussion. Although articles focusing on sex trafficking do not ever form the largest proportion of articles, these articles are one of the most represented topics in most years. In addition, by the end of the time period of analysis, articles focusing on sex trafficking are the second most common topic. Together, the sex trafficking and security topics form about 35% of the topics discussed in the articles on human trafficking in 2013. In contrast, while labour trafficking articles are only slightly less prevalent in 2000, by 2012 they are among the least representative of the topics. In addition, the “immigration” topic was just as frequently discussed as the “sex trafficking” topic at the beginning of the time period, but became the least covered topic after 2010.

Figure 6 Average number of articles per year by topic.

Overall, the changes in topic representation over time demonstrate that the conversation around human trafficking has exponentially increased in the past decade. A text analysis of media portrayals provide information that reflects patterns we saw in the analyses of anti-trafficking organisations. First, the prevalence of articles discussing sex trafficking and labour trafficking comports with the prevalence of organisations that focus on sex trafficking over labour trafficking. Namely, discussions on sex trafficking overshadow that of labour trafficking. In addition, the prominence of articles focused on immigration and the foreign aspects of human trafficking is consistent with the perspective that human trafficking and smuggling are inextricably connected. The dominant topic is “security”. Starting in 2012, this is the most common topic, which reveals that the criminal and security aspect of the issue has become increasingly salient over time. In addition, this analysis reveals that there is a multidimensionality to the human trafficking problem that has created space for human trafficking to be framed as (1) a gendered sex trafficking issue; (2) a labour and human rights issue, where the focus is on protecting the human rights of all individuals, and ensure that they are not put into slave-like conditions, regardless of sector; (3) a security issue; (4) an issue of immigration and transnational movement; and (5) a foreign issue rather than a local issue.

Study 2 (online study): the impact of messaging

We now present the results of a survey experiment that investigates how alternative messages may shift public concern for anti-trafficking efforts and support for various anti-trafficking policies. Using the five frames discovered in the media discussions of human trafficking, we investigate whether a messaging strategy that pushes beyond the sexual exploitation of smuggled women has consequences for levels of public supports combating human trafficking.

Procedures and design

This survey experiment tests the relative impact of each of the five dominant messaging themes of human trafficking that we found in the analyses of US print media on an individual’s programmatic and policy preferences related to human trafficking. We embedded this experiment in the nationally representative survey used in Study 1 (see Appendix G for full demographic information).Footnote 29 There are two main portions of the survey experiment.

First, we randomly assigned respondents to receive one of the six conditions defining human trafficking described in Table 2. One condition is the control case, which does not provide a particular messaging frame, and the five treatment conditions define human trafficking with one of the five dominant messaging frames we found through our text analyses of US newspaper articles. The control message contains only basic information about human trafficking. The five treatment groups receive the same information as the control condition, with an additional two sentences that emphasise the particular topic as an important contributor to human trafficking. The frame is also emphasised in the article’s title. The treatment is designed to prime the respondents to think of human trafficking as a national security issue, a human rights and labour issue, a women’s rights (or sex trafficking) issue, a problem due to immigration and a local (rather than foreign) problem.Footnote 30

Table 2 Experimental treatments

Note: Each subject was randomly assigned one of these newspaper articles. Each article began with the sentences found in the control. The other treatments included the sentences listed here in addition to the treatment. Each article also contained a by-line for S. Johnson.

US=United States.

Second, we asked a series of questions to capture respondents’ programmatic and policy preferences related to human trafficking, starting with a question on whether the policy area should be prioritised. More specifically, we asked: “There are many issues facing our country today, and choices have to be made about how to prioritize them. How would you say that the federal government should prioritize anti-trafficking policies and programs?” (response options range from “It should not be a priority at all” to “It should be a top priority”).

We also assessed how willing each respondent is to take actions to combat human trafficking and how likely they were to support specific government policies. To best summarise the data on programmatic and policy preferences, we created two separate indices: one to estimate the behavioural effects of the message frames, and the other to estimate the impact each frame has on changing opinion on government policy.

The behavioural questions, which comprise seven questions (see Online Appendix F for exact question wordings), asked respondents to consider what they, personally, would do to fight human trafficking. This question battery includes questions on the respondent’s likelihood to call the police about trafficking, stop purchasing goods created with illegal labour practices, lobby for an anti-trafficking bill, vote for an elected official who supports anti-trafficking efforts and volunteer time or donate money to anti-trafficking organisation (response options for these questions are on a five-point scale from “Not at all likely” to “Extremely likely” to perform the action discussed).

To estimate attitudes about public policy, we use eight questions that ask about the importance of increasing penalties for traffickers, legalising prostitution, increasing law enforcement training and efforts, reforming border control, ensuring corporate responsibility with respect to fair labour practices and preventing government corruption (response options are provided on a five-point scale ranging from “Not at all important” to “Extremely important”). The exact question wording for each of these outcome measures is noted in Online Appendix F.

We constructed each of the two indices by first averaging the relevant battery of questions. The summary statistics for each index are reported in Table B.1 in Online Appendix B. The respondent behaviour index gives a very high internal consistency score (α=0.88). The government policy index yields a slightly lower score (α=0.80), but is still a highly consistent measure of opinions on government policies.Footnote 31

While Table B.1 in Online Appendix B reports the summary statistics for the priority measure and the demographic measures in raw form, each of these three outcome measures were recoded to range from 0 to 1 for all analyses.Footnote 32 Thus, we can easily interpret a regression coefficient associated with an independent variable as representing a 100*β percentage-point increase in the dependent variable associated with moving from the lowest to highest possible value of the given independent variable.

To ensure that this survey experiment was properly implemented, we examined whether treatments groups are balanced on each demographic statistic (see Table G.3 in Online Appendix G). Overall, random assignment was successful; there is balance on all but one pretreatment demographic measure, including political identification, income, gender, race and education. Given that there is imbalance on age, we present results with and without controls for demographics characteristics, and find that the effect sizes are not sensitive to the inclusion and exclusion of demographic controls.

Results

To better understand the effect of each of the messaging frames, we estimate a regression model to assess the relative effects of the various treatments against that of the control. Table 3 reports the effect of each treatment condition, where the omitted category is the control condition, to examine how messages change citizens’ understanding of how important it is for the government to address human trafficking [columns (1) and (2)], motivation to take action [columns (3) and (4)] and support levels for anti-trafficking policies [columns (5) and (6)].

Table 3 Messaging experiment results

Note: The dependent variable in columns 1 and 2 indicates how much of a priority human trafficking should be. The dependent variable in columns 3 and 4 is the index compiled from behavioural questions asked to the respondent. The dependent variable in columns 5 and 6 is the index compiled from questions on which government policies respondents would support.

Regression standard errors are in parentheses.

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

This analytical exercise shows that the messages that surround human trafficking have an impact on how much human trafficking should be prioritised by the state, the types of behaviours they are willing to take and support for government policies. The domestic and security messaging consistently and significantly increase the perceived level of importance of human trafficking, and motivation to act and support policy measures to combat human trafficking. Our analyses of US print media showed that there has been an emphasis that human trafficking is a foreign problem. The domestic message may be more impactful as it contains information that counters potential priors that human trafficking is not a domestic issue; emphasising that human trafficking can occur locally decreases the distance between the respondents and the issue.

With respect to the efficacy of security, this effect is consistent with findings that repackaging human trafficking from a human rights issue to a crime and security issue triggered greater state-level response (Simmons and Lloyd Reference Surrette2015). This study shows that framing human trafficking as a crime or security issue can also positively shift public attitudes and behaviours. The domestic and security messages both convey a sense that human trafficking may have an impact that might directly affect them, either because of the proximity to them or the potential impact on the crime in this country.Footnote 33 Interestingly, messages that convey information about the victims of the crime and the type of victimisation (labour trafficking, sex trafficking and issues around legal migration) do nothing beyond a generic message about human trafficking.

Discussion

In 2000, the global community created an official definition for human trafficking that encompassed many transnational crime problems (Simmons and Lloyd Reference Surrette2015). Contemporary laws on human trafficking have expanded the concept of trafficking in persons to be neutral with respect to gender, age, race, sector of exploitation (to move beyond sex exploitation), and smuggling is not necessarily part of the recognised victimisation process. However, given a long history of defining human trafficking as smuggling for sexual exploitation, the programmatic focus of human trafficking organisations on sex trafficking and foreign victims specifically, and media coverage on human trafficking emphasising sex trafficking over other forms of trafficking, we find that contemporary public understanding of the human trafficking issue is substantially more narrow than the definition of human trafficking contained in current federal and international laws. This misperception is not necessarily problematic from the perspective of eliciting widespread support for ending human trafficking. Nevertheless, there are implications with respect to levels of support for anti-trafficking policy and programmatic response strategies. Shining a light on other facets of human trafficking – the fact that human trafficking is an issue of security and affects domestic citizens – has the potential to increase public response to the issue.

In this article, we first document that anti-trafficking efforts disproportionately focus on sex trafficking and foreign nationals, and that the public shares a narrow understanding of human trafficking. We examine how anti-trafficking organisations focus their attention on sex versus labour trafficking, as well as international/foreign versus domestic trafficking. These analyses indicate a persistent focus on sex trafficking and international trafficking. Then, we demonstrate that public understanding of human trafficking reflects this overemphasis of sex trafficking through a knowledge quiz of a nationally representative sample, as well as a laboratory experiment.Footnote 34 We also show that trafficking is perceived by the public as nearly synonymous with smuggling. These findings are consistent the prevalence of themes of immigration and foreign trafficking in media portrayals, and the focus of anti-trafficking organisations on foreign nationals.

Second, we explore the range of ways in which human trafficking has been portrayed over time, and the impact of each prominent portrayal on support for anti-trafficking efforts in a survey experiment. The various forms of human trafficking, as well as a legacy definition that focusses on women and prostitution, have created space for human trafficking to be redefined and interpreted in alternative ways, and at times misinterpreted (Jahic and Finckenauer Reference Kempadoo and Doezema2005). Through an analysis of print media over the past five decades, we find that human trafficking can be, and has been, politicised as a human rights or forced labour issue, a foreign issue, an immigration issue, a gendered, sex-exploitation issue and a security issue. The relative impact of the five different messages indicates that support can be enhanced with certain types of messaging strategies. Seeing human trafficking as sex trafficking, general labour/human rights issue or an immigration issue does not necessarily translate to greater activism or a demand for policy change. Interestingly, highlighting that human trafficking includes exploitation that is not sexual in nature does not positively or negatively alter public support. However, emphasising that human trafficking is a local problem (downplaying that human trafficking is a foreign issue that takes place abroad and/or involves immigrants if it takes place within the US border) and a security issue elicits a greater demand for policy action and increased motivation to take actions to combat trafficking.

These results have important implications for those attempting to sway public opinion or alter the policy space on human trafficking. Through an emphasis of proximity to the issue and emphasis on the security harms of the issue to a country as a whole, there are increases in both an individual’s desire to be active in combating trafficking and increases in demands for government action. Thus, although the current emphasis of sex trafficking follows from historical development of the policy space, perhaps because sex trafficking is already top of mind for the public when hearing the words human trafficking, emphasising sex trafficking does not galvanise action as well as other strategies might.

Although emphasising sex trafficking, labour trafficking and immigration do not necessarily translate to more support for government policies, there is no decline in public support for anti-trafficking efforts by emphasising these aspects of the trafficking problem. However, it is important to conduct further research on the effects of each messaging strategy on support for actual policies that experts deem as helpful in mitigating particular forms of trafficking. For instance, Feingold (Reference Gould2005) argues that restricting immigration results in increases in transnational trafficking. Would information about trafficking victims being smuggled into the country make support for more open immigration policies more palatable?

Although the focus on the sexual exploitation of women does not reduce support for anti-trafficking efforts, it has had an impact on domestic anti-trafficking policies. For instance, TVPA and the renewals of TVPA have been criticised as being disproportionately focussed on women and sex trafficking (Bishop Reference Bishop2003; Kandathil Reference Kingdon2005; Soderlund 2005; Rieger Reference Scarpa2006). The initial TVPA was passed in conjunction with the “Violence Against Women Act” (VAWA). Moreover, much of the language used in the discussions of the passage of TVPA involved sex trafficking. According to Carr et al., “to listen to legislators explain the need for TVPA, one might think that human trafficking only happened to women and girls from other countries and that it only involved sex trafficking, not labor trafficking” (Reference Carr, Milgram, Kim and Warnath2014, 112). The reauthorisation of TVPA in 2013 was again attached to VAWA; the reauthorisation was passed as an amendment to the “Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act” signalling that human trafficking and women’s rights go hand in hand.Footnote 35 In addition, because most of the benefits for victims included in TVPA are those for foreign nationals, there is similarly an emphasis on the foreignness of human trafficking (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Milgram, Kim and Warnath2014). As this example elucidates, future research on the specific policy prescriptions that accompany each of the prominent messaging strategies is necessary.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Paulette Lloyd for helpful discussions and comments. Carolyn Buys, Felicia Hanitio, Melissa Marts, Guilherme Russo, Frank Tota, Michael Zuch, Claire Evans and Bryce Williams-Tuggle provided excellent research assistance.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000107