The interaction between interest groups and political parties in most advanced democracies has become more open and contingent both within and across these countries in recent decades (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995; Thomas Reference Thomas2001). In their origins, parties and interest groups maintained very close and highly institutionalised relationships thanks to the creation of shared organisational structures, including joint committees and/or overlapping leadership, and the definition of a common strategy based on shared values and ideological principles (see Siaroff Reference Siaroff1999; Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012, for a review). However, with the consolidation of catch-all and, later, cartel parties, existing structural alliances have been transformed into a model characterised by the greater independence of both types of political organisations (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995). Indeed, political parties have become highly professionalised organisations that have drifted away from their ideological principles in order to maximise electoral rewards. Parties have become increasingly autonomous from interest groups as they seek to finance their political campaigns, win grassroots support to boost their social presence, coopt charismatic leaders and promote common ideas and policy goals. By the same token, interest groups have also become more professionalised as they have achieved financial autonomy, while their incentives to maintain strong ties with parties have weakened in a context of political disaffection and mistrust of political parties.

A growing body of research has contributed to the study of the interactions between interest groups and political parties in western democracies (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995; Allern et al. Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Heaney Reference Heaney, Maisel and Berry2010). Taken together, they stress that no single model can be applied to party-group links either within or across countries (Thomas Reference Thomas2001; Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012). In some cases, political parties have strong ties with a large variety of civil society groups (Yishai Reference Yishai2001); in others, interest groups have close links mostly with those parties with which they share common ideological goals or historical roots (Rasmussen and Lindeboom Reference Rasmussen and Lindeboom2013; Otjes and Rasmussen Reference Otjes and Rasmussen2017); while in others, these links are determined largely by political pragmatism and defined on an ad hoc basis (Thomas Reference Thomas2001; Marshall Reference Marshall2015). Overall, these studies have made a notable contribution to our understanding of interest group–party interactions across countries and over time. However, the extant research tells us little about the factors that determine the contingent nature of these interactions within countries.

This article seeks to go some way to filling this gap by analysing the circumstances in which interest groups contact political parties in order to exchange information, resources, know-how, opinions and policy views on everyday political issues (Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012). To do so, the article takes into account three specific explanatory variables, namely, party status, issue salience and interest-group resources. Thus, the article argues, first, that it is the mainstream parties that constitute the main target for interest groups. In a context of scarce resources, interest groups select the parties they contact in accordance with a party’s capacity and willingness to respond to their policy preferences. Mainstream parties play a dominant role in the policy-making process and, hence, have a greater capacity to impose their points of view and ways of thinking in that process; in contrast to other parties, they are more likely to adjust their initial policy programs to maximise electoral rewards (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006).

Second, the article argues that interest groups dealing with the most salient issues are more likely to contact political parties. In a context of agenda scarcity, policy actors prioritise issues taking into account the policy behaviour of other actors (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009: 44). Once an issue has been identified as important for most citizens, political parties are more likely to pay attention to that issue, as a way of showing their concern and/or of responding to citizen preferences (Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2009). Political parties are more open and willing to interact with interest groups in relation to salient issues because they can obtain valuable political information about the different views their constituents might hold on these issues. Additionally, political parties can obtain interest group expertise and technical information about the most efficient policy alternatives available to them or, more simply, they can demonstrate a concern for particular issues. We expect interest groups to take into account the opportunities that issue salience can generate to advance their policy goals by contacting a larger number of political parties. Finally, the article argues that interest groups with larger material resources are more likely to contact political parties.

The analysis draws on survey data related to interest groups in SpainFootnote 1 and on various datasets concerning agenda dynamics developed by the Quality of Democracy Research group (www.q-dem.com). In general, the article demonstrates that interest groups tend to interact with political parties on an ad hoc basis adhering to a pragmatic strategy that fits into what Thomas has identified as a “collaborative-pragmatic” model (Thomas Reference Thomas2001: 283). In Spain, as in other parliamentary democracies, including the UK, Germany and Sweden, long-standing connections between business groups and conservative parties, between trade unions and socialist parties and between cause-oriented groups (environment, gender rights, etc.) and different political parties (Fishman Reference Fishman1990; Hamman Reference Hamman and Thomas2001; Verge Reference Verge2012; Barberà et al. Reference Barberà, Barrio and Rodríguez2019) coexist alongside short-term forms of interaction. The article makes both a theoretical and empirical contribution to a field of research in which systematic empirical research is growing, albeit focused mainly on the organisational and ideological connections between interest groups and political parties over time and across countries (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995; Allern et al. Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Lisi Reference Lisi2018).

In developing this discussion, the rest of the article is structured as follows. The first section outlines the theoretical framework in which the study is undertaken and defines the hypotheses it seeks to test. Section two describes the data and explains the operationalisation of variables. Section three presents the main results, and the final section discusses them, identifying the main conclusions that can be drawn and suggesting lines for further research.

Interest group–political party interactions

Interest group–political party interactions have become more open and balanced in the last few decades (Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995). In their origins, many political parties were founded as, or were later to emerge from, interest groups – the case, for example, of labor parties and trade unions, conservative parties and business groups and religious parties and certain religious-oriented NGOs (Allern et al. Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Thomas Reference Thomas2001). For decades, political organisations of this kind were closely bound to one another. Mass political parties have long sought to build structural alliances with social groups as a means to mobilise the electoral support of the social, religious or ethnic segments of society they represent (Krouwel Reference Krouwel, Katz and Crotty2006: 254), to capture charismatic leaders and/or to generate economic, human and informational resources to promote common ideas and policy goals. Together with the party’s press and propaganda, interest groups were a key mechanism for winning grassroots support, communicating the party’s ideology and insulating particular segments of society from alternative views and ways of thinking about the economy, society and politics (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995).

Economic and social changes in most advanced democracies – primarily the consolidation of the welfare state and the rise of the middle class – altered the nature and purpose of interest group–political party links. With the consolidation of the catch-all and, later, the cartel parties (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995), political parties gradually became professionalised, capital-intensive organisations that abandoned their ideological positions in order to maximise electoral rewards. Thus, party–interest group interactions no longer pursued a common ideological goal, but rather sought to maximise their chances of political survival (Duverger Reference Duverger1954; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988). Gradually, political parties developed party platforms that were less ideologically oriented and more closely focused on issues and policy positions that appealed to the centre of the political spectrum. Against this backdrop, political parties began to diversify their interactions with interest groups as a way of maximising their chances of re-election. The political rewards associated with keeping strong ties with one specific trade union or business group disappeared in a context of electoral volatility and the decline of citizen involvement in traditional associations.

This transformation occurred in parallel with the proliferation of interest groups, especially nongovernmental associations, which were increasingly in competition with political parties and traditional economic groups (such as trade unions and professional associations) to represent citizen preferences in relation to a large number of issues. At the beginning of the twentieth century, interest groups were mainly socio-economic or producer interest groups that represented and defended the interests of those directly involved in the production process. These were mainly national associations confined to one policy area or economic sector. In contrast, by the mid-1990s, most interest organisations had already become diffuse interest groups, linked to broad constituencies (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008; Mair Reference Yishai2006; Jordan and Maloney Reference Jordan and Maloney2007). Increasingly, trade unions, business groups and professional associations have come to coexist alongside a growing number of other types of groups (most notably, nongovernmental organisations) that have established themselves as an alternative form of political participation in a political context characterised by political disaffection, the decline of party support and outbreaks of political corruption in some countries.

As a result, interest group–party interactions became more open and contingent than in previous decades (Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012). In most western democracies, the close ideological and organisational ties that once characterised party–interest group connections have gradually been complemented with alternative, more pragmatic forms of cooperation that vary over time and across and within countries. More and more interest groups and political parties combine their existing long-term relationships with other short-term forms of communication. Trade unions and business groups alike exchange political and technical information with political parties with which they share no common ideological positions or historical roots (including conservative or liberal parties) as a means of maximising their chances to impose their views and ways of thinking on policy outputs. Hence, the question emerges as to the circumstances under which interest groups are most likely to interact with political parties. In what follows, we seek to demonstrate that the probability of an interest group contacting a political party to exchange information, resources, know-how, opinions and policy views depends on three main factors: the party’s status, the salience of the issue at hand and the size of the group’s resources.

Party status

In a context of limited resources, interests groups have to select which political parties to contact in order to maximise their policy preferences. In doing so, interest groups take into account a party’s willingness to adapt its initial policy positions to alternative views and its capacity to impose policy preferences in the policy process (Thomas Reference Thomas2001: 17; Allern et al. Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Marshall Reference Marshall2015; De Bruycker Reference De Bruycker2016). Mainstream parties are the perfect target for interest groups for several reasons. First, such parties are more likely to adjust their policy programs so as to bring the party’s position more closely in line with public opinion as a means to maximise electoral rewards (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006). Mainstream parties, moreover, deal with a large number of economic and noneconomic issues and, traditionally, adopt a short-term electoral strategy based on ideological instability and the redefinition of a party’s policies after open negotiations with other policy actors.

Second, mainstream parties enjoy a dominant position in the policy-making process. They have the support of a large part of the electorate and, hence, occupy the majority of seats in Parliament, controlling most parliamentary activities. Moreover, they lead all phases of the legislative process and parliamentary oversight and occupy key positions on most parliamentary committees. Theirs is the final decision as to which bills should be discussed in each parliamentary session and before which parliamentary committee these bills will be discussed (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Chaqués Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués-Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015; Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016). Likewise, mainstream parties control government formation, participate in the determination and direction of government policy and are likely to attract more lobbying as they also occupy a prominent position in the news media (de Bruycker Reference De Bruycker2016; Baumgartner and Chaqués Bonafont Reference Baumgartner and ChaquésBonafont2015). Accordingly, we expect interest groups to be more likely to seek access to mainstream parties than they are to other parties (H1).

Issue salience

The more salient the issue, the greater the opportunity interest groups have to attract the attention of political parties (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). Capturing the attention of policy makers is a complex task under conditions of scarcity of attention, in which policy makers have neither the cognitive nor the institutional resources to pay attention to all issues deserving of consideration at any particular point in time. Indeed, politicians have to choose the specific issues on which to spend their time and resources, and this decision is very closely related to the policy behaviour of other actors. The expected willingness of a policy actor to pay attention to an issue and to spend resources in bringing about policy change (or preventing it) increases as other policy actors simultaneously pay attention to that issue (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009: 44).

A large body of research has demonstrated the interconnections across political agendas. Specifically, public responsiveness scholars (e.g. Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2009; Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009; Bertelli and John Reference Bertelli and John2013; among many others) demonstrate that policy-makers tend to follow citizens’ issue attention with marked variations across policy areas and political systems. Policy-makers change their issue priorities over time, adapting their party manifestos (Budge and Klingemann Reference Budge and Klingemann2001; Green-Pedersen and Walgrave 2014), control and legislative activities in parliament (Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2009; Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009; Chaqués Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués-Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015) and even the budget (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009), to take into account shifts in citizens’ issue attention. They do so as a means to show they care about the issues that most citizens consider as being the most critical for the nation, and hence, to maximise their electoral rewards.

Issue salience generates considerable incentives for political parties to listen to interest groups, primarily because the latter have the resources the former need to respond to citizens’ needs. In some circumstances, interest groups can provide up-to-date information and technical expertise or political information about constituencies’ preferences, while in others, they can be crucial allies for avoiding conflict and upholding social stability before and after policy implementation (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008; Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2012; Dür and Mateo Reference Dür and Mateo2016; Beyers and Braun Reference Beyers and Braun2016; Chaques-Bonafont and Muñoz Reference Chaqués-Bonafont and Muñoz2016). What is clear, however, is that whether the interests groups are promoting policy change or defending the status quo, they attempt to make the most of any opportunity generated by issue salience.

When interest groups mobilise, they seek access not only to those parties that share a similar ideology to their own but also to those that may have traditionally held opposite views. In so doing, they hope to maximise their chances of imposing their will in relation to policy outcomes and to show both current and potential members that they are working to represent their affiliates in the policy process, the latter being essential to ensure the group’s survival. In contrast, in periods when issues are deemed unimportant for the nation, a general climate of political inaction might be ushered in, during which interest groups will tend to be less active as they bide their time. Hence, we expect interest groups dealing with salient issues to be more likely to contact political parties than those that deal with less salient issues (H2).

Resources

Finally, the capacity of interest groups to interact with political parties depends to a large extent on the groups’ resources. Existing research finds that resource-rich interest groups have a greater capacity to contact political parties. Thus, interest groups that have more information resources, in terms of expertise and technical knowledge on specific issues (Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008, Chalmers Reference Chalmers2011; Klüver Reference Klüver2012) that represent a large number of citizens in relation to economic, social and political problems (Beyers et al. Reference Beyers, Eising and Maloney2008 and see Dür Reference Dür2008 for an overview); or that have a larger capacity to contribute to the parties’ political campaigns (Austen-Smith Reference Austen-Smith1993) are in a better position to win the attention of a greater number of parties.

In general, the literature suggests that material resources make a difference to lobbying strategies. The bigger the budget, the more financial resources, or the larger the permanent staff working for the organisation, the greater is the capacity of that interest group to engage in a wide variety of advocacy tactics, from establishing personal contacts with different political parties, to sending out mails, hiring consultants or submitting written comments on bills under discussion in the parliamentary arena (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2012). Existing research (see Kohler-Koch et al. Reference Kohler-Koch, Kotzian and Quittkat2017, for a review) also suggests that resource-rich interest groups have better access to the formal and informal structures of decisionmaking, and so can work more closely with public officials and other interest organisations that make up the policy community. In this way, interest groups can meet regularly with the governing party (or parties), exchange information about the evolution of policy problems and engage in discussions of varying degrees of intensity about the need to promote policy change.

However, enjoying greater access to policy-makers does not necessarily mean enjoying greater influence in policy outcomes. In their study of 98 cases of congressional policy-making in which interest groups were active, Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009) investigated whether the magnitude of the resources that interest groups devoted to lobbying activities was related to outcomes across policy areas. Their empirical analysis suggests a modest tendency for policy outcomes to favour those groups that made greater political action committee (PAC) contributions, incurred higher lobbying expenditures or which had a larger membership. In short, existing research indicates that resource-rich interest groups have access to a more diverse repertoire of contacts with political parties than do their counterparts working with a poorer set of resources. But empirical evidence is inconclusive with regard to the actual relationship between the size of interest group resources and their influence on policy outcomes (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009). Hence, we expect interest groups with more resources to be more likely to contact political parties than those with a poorer set of resources (H3).

Data

To test these hypotheses, we employ a self-administered online survey of interest groups in Spain. As no national registry of interest groups has been drawn up to date, we use the dataset constructed by the Quality of Democracy research group (www.q-dem.com), which includes 1,296 interest groups. The sample was selected by identifying all the NGOs, professional organisations, trade unions and business groups that have been active in governmental, parliamentary and media arenas over recent decades in Spain (see www.q-dem.com for details of the data collection process). For each interest group, two individual coders collected information about a large set of group features, including year of creation, financial and human resources, issues the organisation deals with and the type and number of members.

The 1,296 organisations making up the dataset were invited to take part in the online survey between December 2016 and May 2017. An email invitation and two email reminders were sent out to the respective CEOs. The questionnaire followed the design used in the Comparative Interest Groups Survey (https://www.cigsurvey.eu/) and has a 45-minute estimated completion time. It contains 54 questions structured into different areas: internal and organisational characteristics, resources, members, issue area involvement, strategies and activities and external and international relations. Given that only 22% of the organisations invited to participate in the study did so (N=284) and that of these only 141 completed more than 90% of the survey, we checked for nonresponse bias. To do so, we used a binary multivariate model to compare the proportional distribution of characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents. A similar model was used for a continuous variable examining the degree of incomplete responses (skipped questions and drop-offs), while a third model examined recall bias by assessing differences between reported and registered data for participation on government committees. For the 1,296 organisations in our sample frame, we have data about age (or years of experience), type of organisation, staff size and the number of government committees on which they have been invited to participate. We find no significant biases in our data (Table A1 in the Appendix).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

* Transformed from the following categories: Less than 10,000 euros (1), between 10,000 and 49,999 euros (2), between 50,000 and 99,999 euros (3), between 100,000 and 499,999 euros (4), between 500,000 and 1 million euros (5), and more than one million euros (6).

Empirical strategy

As we are interested in the attributes of both the political parties and the interest groups, we use a dyadic model in which the dependent variable is the contact (or no contact) between each interest group and party. The dyadic data are derived from responses to the question: “During the last 12 months, how often has your organization actively sought accessFootnote 2 to the following political parties? (1) Partido Popular (PP), (2) Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), (3) Izquierda Unida (IU), (4) Ciudadanos, (5) Partit Demòcrata Català (before Convergència i Unió or CiU), (6) Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV), (7) Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), (8) Podemos, (9) Other”. We coded each item as a binary outcome and transformed the data in order to represent all possible combinations of parties and interest group organisations. This means that we have 1,120 observations (8 parties x 140 organisations) clustered in 140 interest group organisations. Across the sample, 26 of the 140 interest groups reported not having contact with any party, while 26 reported having contacted all eight parties. Figure 1 summarises the frequency of contacts with each party.

Figure 1. Number of parties contacted.

Figure 1 and Table 1 show that the interest groups had more contacts with the main opposition party (PSOE) than they did with the governing party (PP), while they contacted the two main challenger parties (Ciudadanos and Podemos) with the same degree of frequency. This suggests that, in a situation of political uncertainty, in which decisionmaking is contingent on the formation of different winning coalitions, interest groups will lobby not only the mainstream parties but also those that at some point in the future may have a key role to play in passing legislative proposals or even winning the next election. This was especially the case of Spanish politics after Mariano Rajoy’s PP government won the 2015 and 2016 general elections with less than a third of the votes (i.e., they held roughly a third of the seats in the Congreso de los Diputados, Table A2). In such a context, no single party is able to veto political debate on a given issue – be it euthanasia, surrogate pregnancy or basic income – or to deny access to interest groups to give evidence about legislative proposals (Chaqués Bonafont and Muñoz Reference Chaqués-Bonafont and Muñoz2016). Thus, to avoid their policy positions being disregarded, interest groups diversify their lobbying strategies, contacting the main opposition party (PSOE), the governing party (PP) and those parties (Ciudadanos and Podemos) that may give them support some time during the term of office.

Table 2. Contact by issue salience, mainstream status and resources (clustered by interest group organisations)

Margins after logit.

Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

We have three main independent variables: party status, issue salience and interest group resources. Political parties were classified in two groups: (1) mainstream – which includes what Meguid (Reference Meguid2005: 352) defines as the typical government actors, or what de Vries and Hobolt (Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012: 250) refer to as parties that regularly alternate between government and opposition (here, this includes the conservative PP and the socialist PSOE, which have alternated in government since the consolidation of democracy down to the present day, i.e., from 1982 to 2018, each with an absolute majority of seats in the Congreso de los Diputados during half the period) and (2) nonmainstream parties, which include Ciudadanos – a center-right party, created in 2006, Podemos – a left-wing party created a few months before the 2014 European Parliament elections, and small and regional political parties, such as IU, CIU and the PNV (Orriols and Cordero Reference Orriols and Cordero2016). These last two played a key role in government formation throughout the nineties, giving support to the PP and PSOE governments for almost a decade (Chaqués Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués-Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015). The reactivation of secessionist demands in Catalonia, together with the emergence of Ciudadanos and Podemos, has limited the role of CiU and PNV as agenda settersFootnote 3 (Rodon and Hierro Reference Rodon and Hierro2016; Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016; Rodríguez-Teruel et al. Reference Rodríguez-Teruel, Barrio and Barberà2016; Palau and Muñoz Reference Palau, Muñoz, Di Giorgi and Ilonszki2018). During the period in which the survey was conducted, the PP governed with 36% of the seats of the Congreso de los Diputados, and with the explicit support of Ciudadanos and Coalición Canaria (see Table A2 in the Appendix for a summary). We also used seat share as an additional proxy of mainstream status.

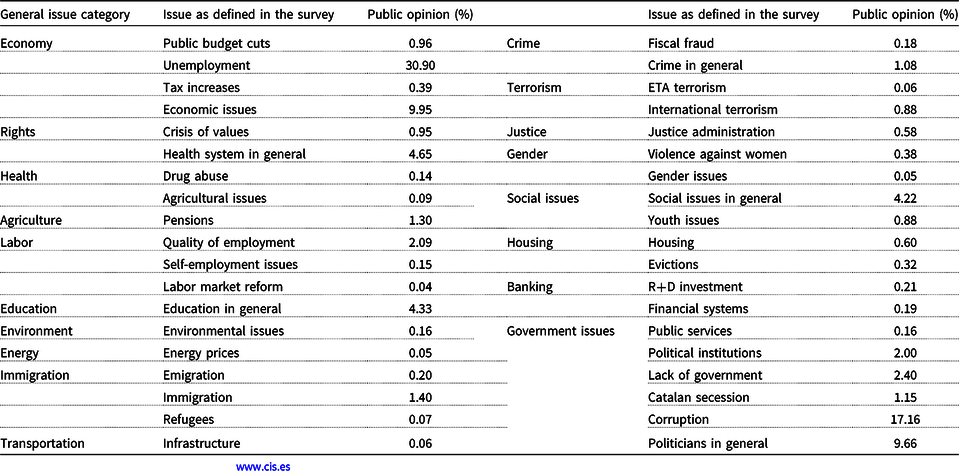

Issue salience was measured using public opinion poll results. Indeed, opinion polls have been used as an indicator of issue salience in many agenda setting studies (see Wlezien Reference Wlezien2005; Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009; Bertelli and John Reference Bertelli and John2013; among many others). Specifically, we use data from the monthly barometers (Barómetro de opinion) conducted among the general population by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) for the period 2016. The CIS reports annual series of citizens’ views about the ‘Most Important Problem’ (MIP) facing the nation. The question is an open, multi-answer question that provides information about individual citizen’s issue prioritisation: “What, in your opinion, is the most important problem facing Spain today? And the second? And the third?”

The operationalisation of the issue salience variable is as follows: first, we aggregated the MIP data, taking the average values for each of the 38 issues in the survey (see Table A3 in the Appendix). By way of example, on average, 30.9% of Spanish citizens identified unemployment as the most important issue for the nation in the period January–December 2016. Second, we identified and coded the issue priority for all interest groups according to the information provided on their website and/or in their statutes. Two individual coders identified the major issue and subissue addressed by the organisation, following the coding for policy issues in the Comparative Agendas Project (www.comparativeagendas.org).

Next, we assigned this measure of issue salience as defined by public opinion to each interest group in line with their own issue priority (see Table A3 in the Appendix). For example, an NGO dealing with gender issues in general is awarded an issue salience of 0.43 because 0.43% of Spanish citizens consider this issue to be the most important issue facing the nation. The same method was applied for the whole sample; thus, an interest group dealing with environmental issues has an issue salience of 0.16, while a group fighting against political corruption has a salience of 17.16, and so on. Some organisations address more than one of the issues listed in the MIP barometer. This is the case of umbrella trade unions or business groups. In this case, the overall measure is the sum of the individual saliences. For example, the overall issue salience score for a trade union is the sum of unemployment (30.9), public budget cuts (0.96), tax increases (0.39), economic issues (9.95), quality of employment (2.09), self-employment issues (0.15), pensions (1.3) and labour market reform (0.04) (see Table A3 in the Appendix)Footnote 4 .

Material resources are proxied using the group’s annual budget. The survey included the question “What was the annual operating budget of your organisation in 2015 in euros?” The response options were less than 10,000 euros (1); between 10,000 and 49,999 euros (2), between 50,000 and 99,999 euros (3), between 100,000 and 499,999 euros (4), between 500,000 and 1 million euros (5) and more than one million euros (6). We take these ordered categories as a continuous variable ranging from 1 (the lowest budget) to 6 (the highest budget) (mean=3.52, sd=1.64).

Finally, we control for the attributes of interest groups and political parties. In the case of the former, we include their age (measured in terms of the number of years since the creation of the organisation) and the type of group (Trade Unions, Business Organizations, NGOs or Professional Associations) (see Table A4 in the Appendix for a description). On the one hand, older groups may have more knowledge and informational resources as to how to deploy advocacy tactics and should have had more opportunities to establish contacts with political parties. On the other hand, trade unions and business groups traditionally have enjoyed greater access to formal decisionmaking venues than have professional organisations and NGOs (see, e.g., Berry Reference Berry1997; Schlozman et al. Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Fraussen and Halpin Reference Fraussen and Halpin2018). In the case of the political parties, we include their ideological position on the left-right scale (economic dimension), using the Chapel Hill Expert survey for the 2016 election and incumbency status. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all variables.

Results

To test the hypotheses discussed in the theoretical section, we regress the contact between interest groups and parties on party status, issue salience and resources. We include controls for interest group age and group type and for the ideology and incumbency status of the political parties. Overall, interest groups deploy their mobilisation strategies by taking into account party status – i.e., interest groups are about 20% more likely to contact mainstream parties than nonmainstream parties (models 1 and 4 in Table 2). This corroborates our initial hypothesis concerning party status. As expected, interest groups are more likely to contact parties that have a greater capacity to set the agenda and impose their views and ways of thinking on the policy process, deal with a larger number of issues, and which, traditionally, have been open to redefining their initial policy positions after open negotiations with other policy actors. To test for robustness, we also perform the analysis with the percentage of seats as a proxy of mainstream status, and results are found to be consistent. Models 2 and 6 in Table 2 show that the likelihood of interest groups contacting a political party increases significantly with the number of party seats. These results are quite similar to the findings of Otjes and Rasmussen (Reference Otjes and Rasmussen2017) for the case of Denmark and the Netherlands and to those of De Bruycker (Reference De Bruycker2016) and Marshall (Reference Marshall2015) for the case of the EU.

With regard to our hypothesis about issue salience, our results suggest that interest groups dealing with issues identified by most citizens as being the nation’s MIPs are more likely to contact political parties. Models 3, 5 and 6 show that issue salience significantly affects which interest groups contact political parties. The coefficient for issue salience is positive and significant when controlling for group and party attributes. Furthermore, interest groups dealing with issues of special concern for Spanish citizens – such as unemployment and political corruption – also contact a larger number of political parties (see Figure 2). This relationship is particularly strong for issues that include the economy – interest groups addressing economic issues contact an average of 6.9 parties – and corruption and unemployment – groups dealing with these issues contact an average of 5.5 parties. In contrast, groups dealing with nonsalient issues, such as agriculture, terrorism and environmental issues, contact on average three parties or less, a number well below the average number of parties to which interest groups seek access.

Figure 2. Number of parties that interest groups seek access to by issue salience (aggregate data by type of issue, N=15).

Overall, these results indicate that interest groups seek to take advantage of the opportunities issue salience generates to advance their policy goals. As discussed in previous sections, political parties are particularly open and willing to listen to interest groups on those issues that most citizens consider as being the nation’s MIPs because the parties need the interest groups’ technical expertise and/or political information about constituencies’ preferences. Interest groups define their mobilisation strategies accordingly, taking into account a party’s willingness to listen to them.

Finally, to test whether material resources make a difference to a group’s mobilisation strategies, we regress the number of times each political party is approached by an interest group on the interest group’s economic resources (Table 2). Model 4 shows interest groups with a bigger budget are significantly more likely to contact political parties. However, these results are not significant when controlling for other group attributes (models 5 and 6 in Table 2) (issue salience, age and group type) or party attributes (status, number of seats and ideology).

Overall, our results show that the likelihood of interest groups approaching political parties to exchange information, resources, know-how, opinions and policy views varies significantly depending on the party type, issue salience and the resources available to the interest group. That is, interest groups seek contact with political parties on an ad hoc basis adhering to a pragmatic strategy that parallels what Thomas (Reference Thomas2001:283) identifies as a “collaborative-pragmatic” model. The next question we seek to address, however, is whether this short-term group–party interaction coexists alongside existing long-term ideological relationships.

Previous research suggests that in Spain some types of interest group have traditionally allied along ideological lines with political parties (see Fishman Reference Fishman1990; Hamman Reference Hamman and Thomas2001; Verge Reference Verge2012, for a review). Structural and ideological factors, such as overlapping leadership and membership, partly explain the long-standing links between Spain’s two main trade unions – Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) – the business community, organised in two centralised employers’ federations – the Confederación Española de Organizaciones Empresariales (CEOE) and the Confederación Española de la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa (CEPYME) – and political parties. For decades, members of the socialist party (PSOE) and the far left party (IU) sat on the UGT and CCOO executive boards, respectively, while union leaders from the UGT and CCOO sat in the Spanish Parliament and even occupied posts in the PSOE Governments (Fishman Reference Fishman1990; Pérez Díaz Reference Pérez Díaz1997). Leadership overlaps also occur between members of the PP and members of the CEOE, different religious groups and professional associations, especially those related to the legal and health systems. In contrast, most NGOs, especially those working in the fields of rights-related issues, foreign aid and international cooperation traditionally have ties to left-wing parties, with the exception of certain NGOs dealing with issues such as moral questions and the victims of terrorist violence (Barberà et al. Reference Barberà, Barrio and Rodríguez2019; Molins et al. Reference Molins, Muñoz and Medina2016).

Our results indicate that party ideology does not significantly affect the likelihood of an interest group seeking to contact a political party. Overall, models 5 and 6 in Table 2 show that the coefficients for party ideology are not significant. To analyse in greater detail the importance of structural explanations in this case, we include interaction coefficients between ideology and the type of interest group in our model (Figure 3 and Table A5). Our results show that economic groups and professional associations interact significantly less with left-wing parties than they do with conservative parties, but these coefficients are not significant. In contrast, as Figure 3 illustrates, NGOs interact significantly more with left-wing parties than they do with other party types.

Figure 3. Predictive margins of interest group type.

Source: Chapel Hill Expert Survey.

In short, our results here point to the fact that the likelihood of an interest group contacting a political party depends on more than just structural and ideological factors. As has been found in the case of the EU (Marshall Reference Marshall2015; De Bruycker Reference De Bruycker2016), the Spanish case shows that interest groups may contact parties that are not their “natural allies” in either ideological or institutional terms in their efforts to influence policy outcomes. This is not to say that structural connections are irrelevant; on the contrary, our results indicate that interest groups tend to prioritise contacts with those parties with which they have maintained a long-standing relationship and a close ideological position. Yet, our findings also show that issue salience and party status are the only factors that can significantly predict interest groups’ decisions to interact with political parties.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that interest groups strategically define their mobilisation strategies vis-à-vis political parties by taking into account party status and issue salience. Mainstream parties are the primary target of interest groups essentially because they occupy a dominant position in the policy process and, also, because they are more open and willing to adapt their policy positions to changing conditions. Furthermore, we demonstrate that interest groups dealing with salient issues are more likely to contact political parties. Specifically, our results show that groups dealing with issues that most citizens consider as being the most important problems faced by the nation (in Spain, political corruption and unemployment) are more likely to engage in short-term forms of mobilisation with a larger number of parties than those groups dealing with nonsalient issues (for example, terrorism and agriculture).

Likewise, our results suggest that interest groups’ decisions to mobilise take into account a political party’s willingness to respond to political requests. Once an issue has attracted the attention of a majority of citizens, political parties are more willing to listen to a group’s policy positions in exchange for the technical and political information the group can provide. Similarly, we have shown that existing structural/ideological connections between political parties and interest group types are relevant, but that they do not significantly affect interest groups’ decisions to contact political parties. In Spain, as in other parliamentary democracies, including the UK, Germany or Sweden, long-standing connections between parties and interest groups seem to coexist with pragmatic forms of interaction (Thomas Reference Thomas2001; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995).

Overall, the analysis reported here contributes to a growing field of research aimed at gaining a better understanding of the conditions in which interest groups interact with political parties. To date, most of this literature has focused mainly on organisational, ideological and structural connections, overlooking what is often the contingent and dynamic nature of interest group–political party interactions. While this contribution is limited to the circumstances of a single country, it has nevertheless sought to advance our knowledge of group–party interactions by signaling and systematically analysing their contingent character. We have shown that such interactions cannot only be explained in terms of a structural narrative, but that they are also moderated by short-term factors, including issue salience and party status. However, these findings show the need to examine the dynamic and contingent character of interest group–political party interactions in greater depth. Further research is required to better understand to what extend interest groups, especially those with a larger set of resources, can determine which are the issues that most citizen’s consider are the most important issues for the nation; to what extend the nature of interest groups–party interactions apply to other contexts with different party systems and/or to identify whether some issues are more likely to provide interest groups with access to political parties.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the rest of the members of the Quality of Democracy research group, the interest groups that responded to the survey and all reviewers that provide comments aimed to improve the quality of this article. Also, we are grateful to the ICREA foundation and the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MEyC). This article is an output of the Project CSO-2015-69878-P of the MEyC.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/K0HGCE. Also data of the whole survey can be downloaded at www.q-dem.com

Appendix

Table A1. Analyses of nonresponse recall bias

Normalised values – odd ratios after logit in models 1 and 3.

Standard errors in parentheses.

* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Table A2. General features of the Spanish Political System, 1982–1997

Source: Adapted from Chaqués-Bonafont, Laura, A. Palau and Frank Baumgartner. 2015 Agenda Dynamics in Spain. London: Palgrave.

Note: PSOE (Partido Socialista Obrero Español), PP (Partido Popular), PCE (Partido Comunista de España), CDS (Centro Democrático y Social), EE (Euskadico Esquerra), CiU (Convergència i Unió), PNV (Partido Nacionalista Vasco), CC (Coalición Canaria), CHA (Chunta Aragonesa), ERC (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya), IU (Izquierda Unida), BNG (Bloque Nacionalista Gallego), UPN (Unión del Pueblo Navarro), PDeCAT (Partit Demócrata Català). Pedro Sánchez elected Presidente del Gobierno, the second of June 2018, after winning a motion of no-confidence.

Table A3. Issue salience

Source: Based on the CIS Barómetro de opinión (www.cis.es). Percentages are the average percentage of citizens that identified any of these issues as one of the most important problems faced by the nation in 2016 and during the first six months of 2017.

Table A4. Classification of interest groups

Table A5. Interaction between interest group type and party ideology

Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.