Today, Congress hires fewer staffers, for lower pay, in an increasingly complex policymaking environment.Footnote 1 While congressional staff numbers have stagnated, the average congressional district population has increased by 52% since 1970.Footnote 2 Consequently, think tanks, political scientists and lawmakers have raised concerns over the “decimation and marginalisation of staff and research capacity” in Congress.Footnote 3 To these observers, an impoverished legislative branch raises the specter of constitutional imbalance and invites lobbyists to fill a vacuum of expertise.Footnote 4

Despite these concerns, political scientists face significant challenges if they wish to understand the consequences of an under-resourced legislature. While new studies of congressional capacity rely upon staff as a significant causal mechanism (Bolton and Thrower Reference Bolton and Thrower2015), few political scientists have directly analysed the value of congressional staff to lawmaking outcomes (Nyhan and Montgomery Reference Nyhan and Montgomery2015; Montgomery and Nyhan Reference Montgomery and Nyhan2017). Research on congressional capacity is scarce for good reason; personnel allowances are, with few exceptions, uniformly distributed across lawmakers, and office expenses equitably reflect geographic differences across electoral districts. Moreover, reductions in congressional resources tend to be rare, chamber-wide events, which leaves researchers with little individual-level variation and few empirical strategies to evaluate the political implications of an underfunded legislature.

To overcome this challenge, I analyse the abolition of legislative service organizations (LSOs) in the wake of the “Republican Revolution” of 1994. LSOs were voluntary membership organisations in the House of Representatives that, like modern caucuses (e.g. the Blue Dog Coalition), organised to advance their collective political ambitions.Footnote 5 Unlike modern caucuses, however, LSOs received official congressional resources, and many groups exclusively relied upon taxpayer dollars, rather than outside funds. Crucially, the abolition of LSOs stripped legislative resources from a subset of legislators within the House of Representatives, providing an opportunity to estimate the individual-level impact of losing congressional staff, office space and administrative services.

By investigating the abolition of LSOs, this research also speaks to a growing body of research on congressional factions (Koger et al. Reference Koger, Masket and Noel2009; DiSalvo Reference DiSalvo2012; Sin Reference Sin2014; Dewan and Squintani Reference Dewan and Squintani2015; Ragusa and Gaspar Reference Ragusa and Gaspar2016; Bloch Rubin Reference Bloch Rubin2017). While contemporary legislators and journalists viewed the abolition of LSOs as a significant power grab, this moment in the development of faction institutions has not yet been the subject of scholarly analysis. I argue that depriving legislative blocs of congressional resources pushed factions to look beyond Congress for political support. Withdrawing congressional funding for caucuses created strong incentives to improve ties with well-funded interest groups. As a result, organised blocs of lawmakers have deemphasised their role as research operations and constructed new institutions that more effectively appeal to donors and outside groups (Clarke Reference Clarke2017). In this sense, the design of modern factions, such as the House Freedom Caucus, can be traced to the abolition of LSOs.

To evaluate the consequences of dismantling an entire category of political institutions, I employ a within-member difference-in-difference design. Using archived Congressional Research Service reports, I estimate the cost of abolition to former LSO chairs. I find that LSO leaders became less influential lawmakers after their institutions were dismantled, while other, more informal caucuses (i.e. those that never received official resources) were unaffected by the Republican reform efforts. Following this analysis, I consider the divergent institutional adjustments adopted by the Democratic Study Group (DSG) and the Republican Study Committee (RSC) using a blend of political science scholarship, archival records available in the Library of Congress, and contemporary affiliates of each respective group.

Legislative service organizations

Informal legislative coalitions have long played a role in American politics and policymaking. In 1979, however, a subset of congressional caucuses were granted access to official resources in the U.S. House of Representatives. The certification of these LSOs marked a new period of institutional development for congressional factions, such as the DSG. LSOs were formally defined as “any congressional caucus, committee, coalition or similar group” which [1] was composed of legislators, [2] solely provided legislative services, [3] ran on public resources and [4] maintained a minimum level of sponsorship from House members (Richardson Reference Richardson1987, CRS-2). In short, LSOs facilitated the public policymaking efforts of legislative blocs. In contrast to more informal coalitions of legislators (e.g. the Congressional Boating Caucus), these organisations were generally well-funded institutions with full-time staff and official by-laws and internal procedures.

Caucuses that received LSO certification were able to construct a reliable system for collecting revenue from members. During this time period, lawmakers were afforded three distinct categories of funds – clerk-hire, official allowances and the congressional frank – to support their legislative and representational duties.Footnote 6 LSO members were able to directly funnel these House-appropriated resources towards the collective ambitions of their legislative bloc. In contrast to modern caucuses, LSO certification provided predictable revenue without expending additional time fund-raising for the bloc. As a result, certification created a flexible, efficient means for redistributing official House funds. For example, LSO leaders could employ no more than 18 full-time staffers to run both their personal district and D.C. operations, but through LSOs, these individuals could draw on contributed clerk-hire funds to hire staff committed to the bloc’s collective ambitions. Moreover, LSO members with surplus funds, which did not roll over annually, could simply redirect money to the group. These organisations were thus able to transfer official House resources towards the administrative costs of legislative coordination.Footnote 7

LSOs were particularly valuable to legislators, because these resources financed custom sources of information – often independent of traditional sources of congressional power – and a forum to coordinate parliamentary maneuver. As a member of the Congressional Steel Caucus put it, “it takes a formal mechanism” to accomplish group goals in congressional politics, and LSOs provided reliable dues, staff, and meeting space.Footnote 8 In this respect, LSOs had an advantage over the vast majority of informal associations in Congress (e.g. the Mushroom Caucus) that lacked an institutional framework.

Caucuses, broadly defined as voluntary congressional membership groups, have been the subject of political science research for decades (Caldwell Reference Caldwell1989; Vega Reference Vega1993; Hammond Reference Hammond2001; Lucas and Deutchman Reference Lucas and Deutchman2009; Miler Reference Miler2011; Ringe et al. Reference Ringe, Victor and Carman2013). By establishing new endogenous institutions, the most prominent LSO chairs circumvented traditional paths to legislative influence.Footnote 9 By the early 1990s, congressional leaders viewed the growing system of LSOs as a threat to their legislative influence: “a lot of committee chairmen are not happy with the increase in caucuses,” according to one lobbyist, because LSOs “almost compete with the committee system.”Footnote 10

LSOs varied in strength, size, policy domain and institutional capacity (Vega Reference Vega1993).Footnote 11 Smaller, issue-specific groups often remained dormant until legislation emerged that affected their narrow agenda. Larger groups routinely provided summary memos of complicated legislation, circulated talking points for salient issues, publicised alternative policy platforms and advanced their own budget proposals.Footnote 12 Naturally, LSOs received variable support for their political operations. For example, Figure 1 illustrates contributions to LSOs during Fiscal Year 1987. In sum, 26 LSOs raised what would be about $6.8 Million USD today, excluding cash reserves maintained by LSOs throughout this time. To put that figure in context, the DSG’s receipts generally exceeded those of the Blue Dog PAC, the political arm of a well-funded centrist caucus today. After adjusting for inflation, contributions to the DSG in 1987 surpassed the Blue Dog Coalition’s receipts in 1996, 1998 and 2000 combined.

Figure 1 Variation in contributions across LSOs. (Data Source: CRS Report, FY 1987). LSO, legislative service organizations.

Unsurprisingly, the flexible financing of legislative groups raised new legal questions. As early as 1981, reformers targeted several LSOs on charges of waste and unethical behaviour. For example, the Better Government Association found that several groups had used the ambiguous legal status of LSOs to effectively circumvent the House ethics code. Individual legislators could receive no more than $100 in gifts from lobbyists and other outside groups at the time, but several LSOs (e.g. the Travel and Tourism Caucus) had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars as an organisation – while maintaining a steady stream of public funding.Footnote 13 In response to these allegations, the House implemented regulations for all LSOs, including a prohibition on outside funds. The acquisition of congressional funds thus limited the necessity of outside fund-raising efforts and imposed regulations on a subset of caucuses. LSOs could support themselves with a direct dues system in the House, but accepting these funds foreclosed the possibility of raising outside funds. LSOs, particularly larger, ideological groups, continued to operate as an integral set of policymaking institutions for over a decade. But as the “Republican Revolution” swept through the American political landscape in 1994, these organisations would abruptly lose their primary means of funding staff and legislative research.

The abolition of LSOs

The new Republican majority removed LSOs almost immediately. On December 7, 1994, House Republicans voted to cut LSO funds. Days into the 104th Congress, the Rules were adopted with a section titled “Abolition of Legislative Service Organizations” (H.Res. 6, Section 222):

The establishment or continuation of any legislative service organization (as defined and authorized in the One Hundred Third Congress) shall be prohibited in the One Hundred Fourth Congress. The Committee on House Oversight shall take such steps as are necessary to ensure an orderly termination and accounting for funds of any legislative service organization in existence on January 3, 1995.

With that, the primary institution for ideological, regional and special interest factions was swiftly abolished with several justifications.

Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) described the move as one important component of a plan to “decisively shrink Congress.”Footnote 14 To the new Republican majority, the ties between LSOs and their ostensibly independent foundations – despite the regulations implemented in the 1980s – also threatened a congressional scandal in a key moment for conservative policymakers. Moreover, abolishing LSOs would make it easier to sell the Gerald Ford House Office building, demonstrating the frugal character of the new majority. Abolition was thus a low-cost gesture of good governance, careful budgeting, and ethical housekeeping that would make for positive press.

Unlike earlier reform attempts, however, many lawmakers and journalists viewed the abolition of LSOs as an attempt to concentrate power in the hands of Republican leadership. LSO leaders were outraged. The chairman of the DSG, for example, claimed that Speaker Gingrich had fundamentally upended House politics: “the centralization of control that the speaker has done such a good job of accomplishing included a centralization of information.”Footnote 15 Others echoed these concerns, arguing that the abolition of LSOs would reduce the quality of the information available to legislative blocs: “It’s like taking a functioning operation and putting it out in a shed. Everything is done in a less professional manner because we have no money, no staff.”Footnote 16 Other LSO leaders felt “really hamstrung,” because they “lost [their] own sources of information.”Footnote 17

Those that wished to abolish LSOs also justified their position on the grounds that LSOs were simply too effective. For example, Gary Lee (R-CA) argued that LSOs undermined a more centralised system under the direction of party and committee leaders:

… the House of Representatives has witnessed a new phenomenon – caucuses which acquire the advantage of permanent staff and independent financial support. As these units proliferate, they increasingly compete with and, on occasion, supplant the legitimate legislative process. […] In seeking to strengthen the process of policy deliberation, we should endeavor to enhance the framework of the institutional leadership and the committee structure. By continuing to permit LSO’s to receive congressional funding, we make it more difficult to achieve that goal.Footnote 18

Prominent allies of Speaker Gingrich did not dispute the centralisation of information that would follow LSO abolition. According to John Boehner (R-OH), “it is the responsibility of leadership to provide such information,” and Pat Roberts (R-KS) agreed: “We have subcommittee information, committee information, leadership information.”Footnote 19

In short, the new Republican majority cut off public funding for key legislative coalitions in the House immediately prior to one of the most active periods of lawmaking in modern history, and LSO leaders contested that the decision was intended to neutralise their influence in public policymaking.Footnote 20 By sharply disbanding a system of legislative institutions, the Republican leadership effectively stripped LSO chairs of resources thought to improve lawmaking capacity. The abolition of LSOs is thus expected to diminish LSO chairs’ relative influence in legislative politics. This largely exogenous moment of reform thus provides my central hypothesis:

LSO abolition hypothesis: LSO leaders will become less effective lawmakers after losing congressional resources (i.e. post-LSO abolition).

This decision also carried significant normative implications, as House leaders had effectively removed the “golden handcuffs” placed on pre-eminent legislative organisations and created new incentives to curry favour with outside groups.

Data and design

To test this hypothesis, I employ a within-member difference-in-difference design similar to those used in recent scholarship on congressional committee chairs (Berry and Fowler Reference Berry and Fowler2018). Using roughly three decades (1985–2014) of data on legislative effectiveness, I analyse the impact of reduced congressional resources on relative influence in the House of Representatives. More specifically, I estimate the following linear model:

$$\eqalign {{\rm Legislative}\;{\rm effectiveness}\;{\rm ranking}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} {\equals} \beta _{1} {\rm Treatment}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} {\plus}\beta _{2} {\rm Placebo}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} \cr {\plus}\gamma _{{(i)}} {\plus}\delta _{{(t)}} {\plus}{\varepsilon}_{{(it)}}.$$

$$\eqalign {{\rm Legislative}\;{\rm effectiveness}\;{\rm ranking}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} {\equals} \beta _{1} {\rm Treatment}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} {\plus}\beta _{2} {\rm Placebo}_{{{\rm (}it{\rm )}}} \cr {\plus}\gamma _{{(i)}} {\plus}\delta _{{(t)}} {\plus}{\varepsilon}_{{(it)}}.$$To understand the consequence of losing LSO resources, I begin with Volden and Wiseman (Reference Volden and Wiseman2014)’s Legislative Effectiveness Project. Volden and Wiseman (Reference Volden and Wiseman2014) scrape every public bill (H.R.) in the House of Representatives from 1973 to 2014 to construct a summary statistics of legislative productivity. Their measure – Legislative Effectiveness Scores (LES) – begins with a count of five key legislative outcomes: bill sponsorship, the number of sponsored bills that receive action in committee, the number of sponsored bills that receive action beyond committee, the number of sponsored bills that pass the House, and finally, the number of sponsored bills that become law. They then proceed to weight each of these counts by their impact on public policy outcomes. Commemorative bills are given lower weight than substantive bills, which, in turn, are given lower weight than substantive and significant bills.Footnote 21 This weighted metric is then normalised so that the average LES in each Congress is exactly 1.

To provide an intuitive interpretation of these scores, my primary dependent variable is a transformed version of Volden and Wiseman’s measure. More specifically, I rank order the LES for each House member in each Congress. Members with higher Legislative Effectiveness rankings(it) are more effective, and negative coefficients indicate a relative decline in legislative influence.Footnote 22 In additional analyses, I use the five underlying legislative outcomes (e.g. number of total sponsored bills) to better understand the nature of my results. Finally, I replicate my primary findings in the online Appendix using raw and logged legislative effectiveness scores.

My primary independent variable, Treatment(it), is a binary indicator for any legislator that experienced the “treatment” of reduced resources following the abolition of LSOs. More specifically, former LSO leaders serving after LSOs are abolished (1995–2014) are coded as 1. While complete membership data would provide a more precise estimate of the consequences of resource loss, LSOs were not required to maintain full membership data for their organisations. To maintain their LSO certification, however, leaders of these legislative blocs — those most likely to benefit from official group resources — were required to file paperwork with the Committee on House Administration. These data were later collected and supplemented in a series of Congressional Research Service analyses.Footnote 23 These reports were largely published by Sula P. Richardson between 1986 and 1999, which provides the foundation for a dataset covering a majority of the years that LSOs operated in Congress.Footnote 24

LSOs were the only subset of congressional caucuses to receive official House resources, but these organisations co-existed with a far larger number of unofficial groups (i.e. caucuses that were not certified as LSOs). Drawing on the same underlying CRS analyses, I code informal caucus leadership data to construct a Placebo(it) variable. Generally speaking, caucuses provide useful social networks and valuable sources of information to lawmakers (Ringe et al. Reference Ringe, Victor and Carman2013). Like LSOs, these groups vary in their apparent influence. For example, the Conservative Democratic Forum, or “Boll Weevils,” proved to be a key legislative bloc in securing President Reagan’s defense spending increases and tax cuts (Kriner and Reeves Reference Kriner and Reeves2015). On the other hand, a large number of informal caucuses were thought to be far less important by contemporary journalists. For example, the St. Petersburg Times, writing in 1995, remarked, “Unlike LSOs that Congress sharply restricted this year, the [Congressional Cowboy] Boot Caucus has no staff or funding, and no ideological cohesion. It’s simply a bunch of legislators who amble around in cowboy boots.” Nevertheless, many informal caucuses are thought to have provided a valuable network of legislators between 1979 and 1995. Crucially, these groups did not rely upon House resources. As a result, LSO and informal caucuses share common features, but only LSOs received the largely exogenous “treatment” of reduced resources in 104th Congress.

In the model above, γ (i) and δ (t) indicate legislator and time fixed effects, respectively. Given the panel structure of my data, all standard errors are clustered by individual legislator. By including γ (i), the model accounts for both observed and unobserved time-invariant attributes of lawmakers (e.g. innate political talent or ambition). Similarly, δ (t) control for observed and unobserved unit-invariant confounding variables (e.g. changes to the political environment that consistently affect all members of the House). The inclusion of both γ (i) and δ (t) amounts to a generalised difference-in-difference design. Importantly, this modelling strategy allows for systematic, pretreatment differences between my “treatment” and “control” groups. Difference-in-difference designs provide an average treatment effect for the treated, conditional on a key “parallel paths” assumption. In this case, the assumption requires that the average trends in legislative effectiveness of LSO leaders should run parallel to those that never led a congressional caucus prior to the abolition of LSOs.

Finally, I use the coarsened exact matching algorithm presented in Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2011) to preprocess my data. More specifically, I specify a vector of time- and unit-varying variables that are likely to affect both legislative effectiveness and individual prospects of LSO leadership. The coarsened exact matching algorithm uses this vector of possible confounding variables to pair observations across values for the Treatment(it) variable. Observations without a good match are pruned from the dataset in an attempt to provide a cleaner estimate of the causal effect of LSO abolition.Footnote 25 I include a fairly standard battery of variables believed to influence legislative effectiveness. Dichotomous indicators for Committee Chairs, Sub-Committee Chairs and members of Power Committees (i.e. Appropriations, Rules, and Ways and Means) are included, as these positions provide congressional resources, procedural authority, and prestige among political elites. To account for the distinct data generating processes of the two major parties as congressional control shifts, I also include a Majority Party Member (it) indicator, where values of “1” indicate legislator i is a member of the majority party in Congress t.Footnote 26 All control variables are provided by the Legislative Effectiveness Project. I rerun my analysis in Table A2 using a traditional control variable approach.Footnote 27

I turn next to my results. To recap, the LSO Abolition Hypothesis provides a directional prediction for the Treatment(it) variable; because former LSO chairs are stripped of valuable staff and resources, β 1 should be negative, indicating a reduction in relative legislative effectiveness. By contrast, the β 2 coefficient should not be significant. Informal caucus leaders – my Placebo(it) group – should not experience a shock to their legislative capacity after the 104th Congress.

Results

Before proceeding to the results of the difference-in-difference model, I consider the parallel paths assumption previously discussed. Figure 2 depicts two sets of linear trends with the x-axis denoting time and the y-axis denoting the average legislative effectiveness ranking of former LSO leaders and legislators without LSO leadership experience from 1987 to 2014.Footnote 28 The parallel paths assumption seems to have some support. LSO leaders had a slight advantage over their House colleagues, but both groups followed, roughly, the same trajectory before the abolition of LSOs. After the 104th Congress, the relative advantage afforded to LSO leaders significantly decreased.

Figure 2 Trends in average legislative effectiveness ranking. (Data: 1987–2014). LSO, legislative service organizations.

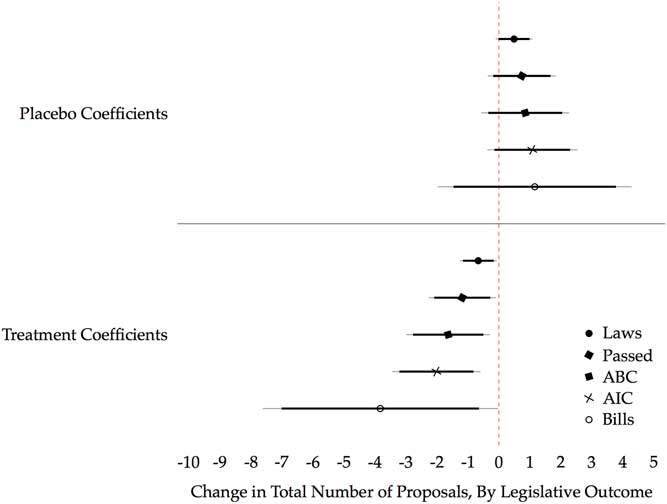

The results of the difference-in-difference analysis, presented in Figure 3, further support the LSO Abolition Hypothesis.Footnote 29 The abolition of LSOs significantly decreased the relative legislative effectiveness of former LSO chairs. More specifically, leaders of these previously funded blocs dropped approximately 85 positions in a rank ordering of the most effective lawmakers in the House (p<0.05, one-tailed test). By contrast, former leaders of informal congressional caucuses – i.e. those that were never certified LSOs – remained unaffected by the dramatic institutional changes implemented in the 104th Congress. Postestimation tests reveal that the difference between these coefficients is statistically significant. In short, former LSO leaders were significantly less influential after their organisation lost office space, direct congressional funding and the status of leading a recognised bloc of legislators in the House.

Figure 3 Former LSO leaders dropped in legislative effectiveness rankings. (difference-in-difference analysis with coarsened exact matching). LSO, legislative service organizations.

Next, I unpack the summary statistic provided by Volden and Wiseman (Reference Volden and Wiseman2014) and analyse the effect of LSO abolition on individual indicators of legislative productivity. Figure 4 reports the result of five models that use the same specification outlined in the previous section, with the exception of the dependent variables.Footnote 30 After being stripped of LSO resources, former LSO leaders sponsor fewer bills, although this is estimated with large standard errors.Footnote 31 Moreover, these lawmakers are less likely to see their sponsored proposals receive action in committee or find success on the floor. Across all five alternative dependent variables, the “Placebo” coefficient is, in general, indistinguishable from zero; the “Treatment” coefficients are negative and, in general, statistically significant. These results suggest that the cost of LSO abolition was not specific to drafting legislation. Losing congressional resources appears to have diminished LSO leaders’ ability to enact changes to public policy.

Figure 4 Former LSO leaders became less productive lawmakers. (difference-in-difference analyses with coarsened exact matching). LSO, legislative service organizations.

Legislative effectiveness scores are a new, intuitive and continuously updated measure of legislative influence, but Volden and Wiseman (Reference Volden and Wiseman2014) do not provide the only measure of relative or absolute policy success. Because the legislative effectiveness project does not utilise amendments in any way, I first turn to congressional network data (1973–2004) made available by Fowler (Reference Fowler2006a) and Fowler (Reference Fowler2006b). Figure 5 reports the impact of LSO abolition on the number of sponsored amendments that went on to pass in the House of Representatives. The coefficient for former LSO leaders is negative and statistically significant (p<0.05, one-tailed test), while we find a null result for caucus members that never received LSO certification. This finding is consistent with the findings using composite and disaggregated legislative effectiveness scores.

Figure 5 Former LSO leaders passed fewer sponsored amendments. (difference-in-difference analyses with coarsened exact matching). LSO, legislative service organizations.

Finally, I explore the impact of LSO abolition using four leading measures of legislative centrality available in the Fowler dataset. Figure 6 reports the results using closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, connectedness and eigenvector centrality, all of which are discussed at length in Fowler (Reference Fowler2006a). In each case, the coefficient for former LSO leaders is negative. By contrast, the coefficients for caucus leaders that did not depend on official House resources are consistently positive. The statistical significance of the treatment coefficient fluctuates across metrics, but the results in three of the four measures of legislative network centrality are statistically significant (p<0.05, one-tailed test).

Figure 6 Former LSO leaders became less central to legislative networks. (difference-in-difference analyses with coarsened exact matching). LSO, legislative service organizations.

Taken together, these results suggest that the reforms of the 104th Congress had a significant impact on power dynamics in the House of Representatives. By swiftly abolishing a category of legislative institutions, party leaders diminished the influence of those that led legislative blocs. Moreover, congressional caucuses that did not rely upon House resources appear to have been unaffected by these reforms, suggesting that congressional resources were a primary mechanism of LSO influence. In the section that follows, I detail the institutional decisions made by two prominent groups in the aftermath of the Republican reforms.

Institutional adjustments

LSOs responded to the abolition in distinct ways. In this section, I consider the divergent paths taken by the DSG and the RSC to adjust their legislative institutions. The DSG and RSC were chosen primarily due to the availability of archival data, primary sources, and high-quality research on their actions during this time period. It should be noted that the availability of qualitative resources speaks to the disproportionate influence of both factions and, in many ways, the two groups are outliers in their significance among LSOs. Nevertheless, the empirical results reported in the prior section are not dependent on the inclusion of these organisations (see the online Appendix). These two cases are intended to illustrate the importance of the funding structures available to LSOs and the consequences for cutting those funds in 1995.

The DSG

The DSG informally began as a loose coalition of liberal lawmakers in early 1957. In issuing their “Liberal Manifesto,” the liberal bloc sought to break through key veto points – namely an obstructionist bloc of Southerners – that had stalled, diluted, or defeated significant civil rights proposals. To overcome the powerful and intransigent Rules and Judiciary committees, the DSG would construct a subpartisan institution with incredible capacity to distribute information, coordinate legislative behaviour, and remove procedural barriers to the enactment of the Democratic Platform.

The DSG more formally organised in September 1959 with the explicit goal of counteracting the disproportionate negative agenda power of the Conservative Coalition (Jenkins and Monroe Reference Jenkins and Monroe2014). While the liberal group initially relied upon a part-time administrative assistant, the organisation would soon establish a regionally diverse Executive Committee, full-time staff, an orientation program for new legislators, a formal set of internal rules, and liaisons to broker deals with both the President and prominent Senate leaders. The group maintained a three-tiered membership system — a “whip list” a “dues list” and a “mailing list” — carefully managed by an elected hierarchy of faction leaders.Footnote 32 The DSG would continue to evolve in the years that followed. They created substantive task forces with the intention of providing a manageable forum for DSG action, while widening participation and utilising the pre-existing policy expertise of its members.Footnote 33 Initially, the DSG established a “resource pooling arrangement,” built on a turn-based system of clerk-hire contributions and annual dues to cover administrative costs and an unmarked office close to the Capitol.Footnote 34 The certification of LSOs in 1979, however, provided the DSG with an official account for congressional funds, a streamlined process for collecting dues, and premier office space in the Longworth House Office Building. LSO status afforded the bloc credibility among ideological allies and tangible resources to conduct their political operations.

At their peak, the DSG Executive Committee directed an expansive and highly respected research operation. Over a score of full-time staffers regularly issued 5- to 10-page fact sheets, supplemented by weekly legislative reports. These documents contained “the legislative history of a bill, the background of the substantive problem, an outline of the major provisions of the bill, the views of the Administration, probable amendments, and arguments for and against” the most salient proposal of the day (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Miller and Mann1974). In short, the DSG remained relevant through the provision of core services to a significant share of the Democratic Caucus. Legislators and observers alike came to rely upon DSG fact sheets to keep up with the tremendous business of the House:

For 35 years, the Democratic Study Group provided Cliff Notes for Congress […] Reporters bedeviled by everything from milk-marketing orders to the throw-weight of nuclear delivery systems could read DSG and feel reasonably confident they would not sound like morons at the end of the day.Footnote 35

The DSG also circulated more exclusive procedural analysis for votes deemed critical to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. For example, the DSG provided a list of parliamentary manoeuvres executed “to indicate some of the delaying tactics used by opponents [i.e. the Conservative Coalition] under the Calendar Wednesday procedure” along with a path to “prevent some of these manoeuvres.”Footnote 36

Past research suggests that the DSG whips system was indeed effective (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Miller and Mann1974). The DSG demonstrated relatively high levels of cohesion on roll-call votes across issue areas from 1955 to 1970, and, at least anecdotally, the faction’s unity was due to sophisticated parliamentary manoeuvres and high floor turnout. The bloc used the discharge petition, the “Calendar Wednesday” procedure, and several decentralising provisions (e.g. the “21-Day Rule,” adopted in 1965) to counteract the Conservative Coalition and free up a host of liberal proposals languishing in the Rules Committee.Footnote 37 Early legislative victories also provided credibility and prestige to members of the Executive Committee; one internal DSG memo noted the “growing tendency of the leadership to deal with DSG officers as spokesmen for a significant bloc of liberal votes, thereby achieving for the DSG a recognised “group identification” in the House.”Footnote 38 In sum, the group believed their success was due to “better coordination and organisation,” a “sharper definition” of issues key to marginal Republicans in urban districts, and the shrewd use of “parliamentary devices.”Footnote 39

The DSG Executive Committee, like committee chairs and party leaders, controlled a preeminent source of legislative information, directed a well-funded research operation, and managed a battle-tested whip system. The DSG Executive Committee was elected by dues-paying members, with the exception of past-chairmen who retained a permanent position. Election to the Executive Committee changed over time, but for the most part, the group was composed of a chairman, four vice chairmen, a secretary, a whip, a freshman representative, and ten regional representatives. If elections to the Executive Committee resulted in a tie, the DSG would pare the least competitive candidate and cast a new round of ballots. The DSG by-laws formally designed the Executive Committee as “the governing body of the Democratic Study Group” and granted authority to “take such actions as may be necessary to accomplish the operation of the organisation, and to protect the interests of DSG and the members thereof.”Footnote 40

By 1993, the DSG employed 22 full-time staff and collected dues from virtually all House Democrats. Some DSG services had even become a bipartisan staple in the House.Footnote 41 The size and institutional complexity of the DSG had increased significantly since their modest, informal coalition four decades earlier, but the DSG was, in some sense, a victim of its own success (Bloch Rubin Reference Bloch Rubin2017). The primary objectives of the DSG – breaking the Southern hold on the party and fulfilling many key policy proposals – were largely complete by the time Republicans took the House. In light of their success, the group reoriented from an insurgent, ideological faction to a broad-based research centre. While the DSG of the 1960s “served primarily as a whip for progressive legislation,” the LSO-certified DSG would be “focused on internal House reform and on providing research materials.”Footnote 42

The abolition of LSOs significantly reduced DSG leaders’ relative advantage among Democrats. Consider changes in the legislative behaviour of one such chair – Bob Wise (WV-02).Footnote 43 In the 103rd Congress, Rep. Wise was among the top 100 Democratic lawmakers passing major pieces of legislation in the House of Representatives (e.g. the Economic Development Reauthorization Act of 1994). In the 104th Congress, by contrast, none of Wise’s six proposals even received action in a committee. He was ranked 148 of 208 Democrats in the House, and he would continue to struggle with his initiatives until his retirement.

While much of Rep. Wise’s experience must be attributed to the Democrats new status as minority party in the House, the DSG – stripped of its sizable institutional apparatus – quickly conceded its comparative advantage among co-partisans. Figure 7 illustrates the percentage of sponsored bills that received action beyond committee for those that served as DSG members in the 103rd Congress and other rank-and-file Democrats (i.e. those that were not chairs, subchairs or members of the most powerful committees in the House).Footnote 44 The smoothed trajectories of these two groups before and after LSO abolition illustrate distinct patterns. Prior to the 104th Congress, members of the DSG consistently outperformed their rank-and-file counterparts in breaking their sponsored proposals free from committees. By contrast, the gap between those two groups closes significantly in the wake of LSO abolition.

Figure 7 Democratic study group lost their relative advantage in committees. (DSG Data Source: DSG Archives). LSO, legislative service organizations.

After the 104th Congress, the DSG was left searching for an alternative institutional arrangement. In some ways, this was a reversion to the early, rotating model employed by the DSG before LSOs were established, and concerned by the possibility of abolition, the DSG had been cultivating interest group relations for some time.Footnote 45 Eventually, the DSG established DSG Publications, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit corporation with a $5,000 annual subscription fee and 18 full-time staffers.Footnote 46 Before long, however, the House Oversight Committee ruled that House members should not exceed $500 in subscriptions for such services, foreclosing yet another revenue system.Footnote 47 In the end, the DSG sold its research operations to Congressional Quarterly and was otherwise subsumed in the larger Democratic Caucus.Footnote 48

The DSG was perhaps the most successful intraparty organisation in the history of the U.S. House.Footnote 49 After the abolition of LSOs, the organisation quickly collapsed. While several modern caucuses – e.g. the Progressive Caucus – can trace their institutional lineage to the DSG, each would be forced to more closely depend on outside groups for resources and establish complicated internal practices for funding their legislative staff.

The Republican Study Committee

Unlike the DSG, the conservative RSC ultimately succeeded in surviving the post-LSO era. Today, the RSC remains one of the largest and oldest congressional caucuses in the U.S. House of Representatives. Splinter groups, such as the House Freedom Caucus, have dominated congressional headlines, but the RSC has shown remarkable durability in the wake of the 1994 reform to caucus institutions.

Like the DSG, the RSC formally organized to offset the influence of moderate co-partisans (e.g. President Nixon, Minority Leader Gerald Ford) (Feulner Reference Feulner1983). Faced with a similar political dilemma, conservative Republicans explicitly modelled their organisation on the most successful LSO in the House. They sought to “establish among House Republicans a faction that could do for the Republican conservatives what the Democratic Study Group had done for the Democratic liberals” (Feulner Reference Feulner1983, p.57). The RSC would proceed to set up a dues system, hire full-time staff and establish a leadership structure. Their staff produced high-quality information on pending legislation and provided electoral resources to conservative candidates (Bloch Rubin Reference Bloch Rubin2017, p. 266). In short, RSC established a DSG-like system that grew their ranks within the Republican Conference and increased their capacity to mobilise a conservative alternative to both Democrats and moderate Republicans in the House.

RSC leaders fought alongside other prominent LSO leaders for several decades to preserve their institutional status, refuting the notion that abolition was merely a partisan affair with partisan consequences. Instead, LSOs were routinely defended as a check on absolute majoritarian power. For example, Tom DeLay (R-TX) pleaded with his Republican colleagues to preserve LSOs on 24 June 1992:

The Republican Study Committee will end if this [LSO reform proposal] becomes law. The Republican Study Committee has an excellent dedicated staff that does a lot of things for Members as they pool their resources: research, and they write bills and amendments. It supports our offices in moving these bills. It helps develop strategies that affect this legislation. It helps us put together coalitions and outside groups. Mr. Chairman, the worst thing that a minority could do is to eliminate the ability to pool our resources. The majority has huge staffs. The only way we have any opportunity to equal that staff is to be able to pool our resources so that we can advance our positions.Footnote 50

Over a decade earlier, RSC member Dick Schulze (R-PA) made a similar plea to preserve their LSO status, arguing, more specifically, that it was “absolutely imperative that the RSC be located on the Hill” and preserve the existing staffing arrangements afforded to LSOs.Footnote 51 Groups like the RSC were believed to be necessary precisely because they represented an internal, congressional institution free of the majority party’s centralising authority.

How was the RSC, specifically, affected by the abolition of LSOs? Thanks to data provided by Bloch Rubin (Reference Bloch Rubin2017), we can trace the RSC founders’ legislative success over time.Footnote 52 In short, it appears that the RSC founders were becoming steadily more influential among Republicans, but their rise among fellow GOP lawmakers came to a halt after their party took control of the House of Representatives and abolished LSOs. These descriptive patterns are consistent with the analysis in the prior section (Figure 4).

Figure 8 The relative effectiveness of RSC founders plateaus after the abolition of LSOs. (RSC Data Source: Bloch Rubin (Reference Bloch Rubin2017)). LSO, legislative service organizations; RSC, Republican Study Committee.

Like the DSG, prominent RSC members immediately sought new institutional arrangements in the wake of their organisation’s decertification. According to Ernest Istook (R-OK), the group quickly moved to “set up a structure of rotating the payroll for RSC employees from one office to the next, so that everyone was, in effect, sharing the cost but working within the new rules.”Footnote 53 This system proved to be significantly more complex and less generous than the arrangements under the LSO, which provided direct compensation to staffers through two official sources of money (i.e. clerk hire allowance and allowances for official expenses). Next, several members re-branded the organisation as the Conservative Action Team (CAT) – complete with “lapel pins featuring a roaring mountain lion” – and went to work resurrecting the institution.Footnote 54 The RSC would restore its original name, build strong ties to outside groups such as the Heritage Foundation, and nearly double its ranks just a few years later.

In retrospect, it is clear that the abolition of LSOs spared few, if any, taxpayer dollars. The Ford House Office Building — which was used to justify the removal of LSO office space — was never sold, and contributions to LSOs were never actually cut from congressional expenditures. Instead, money spent on LSO dues were occasionally rolled back into individual accounts. Party leaders were thus able to preserve these resources in the individual accounts of lawmakers and continue to undermine collective efforts to coordinate and produce legislative research. While fewer House resources were directed to the operational expenses of these blocs, the remaining funds were buried in a complicated rotation of personal accounts and, over time, supplemented by outside donations.

LSOs were largely valued because they remained under the direct control of elected officials. Some organisations successfully established a hybrid model that would survive the abolition of LSOs, while others failed to find their way in the wake of significant (if not total) reductions in revenue. In any case, caucuses have struggled to serve a simple clearinghouse function for elected members that wish to remain in control of valuable political information. As the RSC case illustrated, “the staff has continually functioned as a collection center for conservative ideas,” and would be “used as a conservative filter to digest and analyse policy materials and information from whatever source” (Feulner Reference Feulner1983, p.204). While LSOs provided a clean and direct means of funding such a research operation, the persistent demand for trustworthy information remains. Curry (Reference Curry2015) effectively summarises this critical point:

Contemporary lawmakers are not deprived of information; rather, the information encompassing their worlds is crushing and cacophonous. The challenge for them is not simply to accrue information but to identify the useful information within their time and resource constraints. A more accurate statement might be that the most difficult thing is for lawmakers to find relevant information that they can trust (Curry Reference Curry2015, p.47).

LSOs, and their hybrid successors, distil and aggregate valuable information. In coordinating their members and disseminating political research, these often-overlooked institutions have provided a comparative advantage to their members.

Nevertheless, Republican leadership abruptly dismantled a system of directly funded political institutions in the 104th Congress, and LSO chairs, accustomed to directing considerable resources towards their organisation’s legislative agenda, were sent scrambling for alternative financial arrangements. While the RSC still operates today, their relationships with outside groups became critical in light of the new House rules. Other blocs, even groups as large as the DSG, buckled under their new political constraints.

Conclusion

As the executive branch continues to expand its influence over public policy, political scientists have been more willing to weigh in on the consequences of an under-resourced legislative branch. This research examines a unique opportunity to evaluate the individual-level impact of congressional resources on legislative outcomes. I have found that the abolition of LSOs — an entire system of institutionalised legislative blocs — significantly reduced the relative influence of lawmakers invested in these organisations. These results are consistent with contemporary concerns as the reforms of the “Republican Revolution” were rolled out. More generally, this research reinforces the importance of informational advantages in the legislative affairs of the House (Curry Reference Curry2015).

LSO-certified organisations did not merely provide a simple means of funding staff; they provided an opportunity to cultivate valuable political resources. Entrepreneurial lawmakers were able to maintain direct control of political information, staffing, and other congressional advantages to overcome significant collective action problems. Members trusted the information distributed within these legislative organisations, because like-minded elected officials remained at the helm.

By dismantling these institutions, groups faced new incentives to experiment with innovative models of financing and organisation. The caucuses that would follow – from the New Democrat Coalition to the House Freedom Caucus – set out to establish tight relations with think tanks and activist organisations to augment their influence. Today, these organisations serve as a clearinghouse for varied outside groups.

In the end, Speaker Gingrich’s move to centralise information may have undermined the authority of party leadership. In de-certifying LSOs, Republicans also de-regulated an entire category of legislative caucuses. Some of these groups collapsed immediately. Others floundered temporarily and bounced back under a hybrid model that arguably provided greater independence to factions in the House of Representatives. Understanding the life-cycle of political institutions can thus shed light on present political conditions, but more research is still needed to understand the role of legislative coalitions in the House of Representatives. As Figure 9 shows, congressional caucuses became more common after the abolition of LSOs. The explosive growth of caucuses deserves greater scholarly attention, and this puzzling trend is further underscored by dramatic moments of party infighting in recent legislative sessions (e.g. the overthrow of Speaker Boehner). Journalists routinely draw on factions to understand congressional politics, but to date, political scientists have made relatively few theoretical and empirical contributions to our understanding of faction power in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Figure 9 The explosive growth of house caucuses after the abolition of LSOs. (Data Source: Glassman (Reference Glassman2017)). LSO, legislative service organizations.

So long as the United States has had political parties, congressional leaders have had to manage fault lines within their governing coalitions. Nevertheless, there is relatively little research on the development of faction institutions. This research provides a quantitative analysis of a watershed moment in the evolution of modern ideological factions. By investigating the abolition of LSOs, we are better equipped to understand intraparty politics in the House of Representatives. As the House Freedom Caucus continues to threaten insurrection within the ranks of the Republican majority, a solid understanding of faction institutions will allow us to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of subpartisan institutions in legislative politics.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X1800034X

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/G3BKWG

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Summer Research Fellowship of the University of Virginia for generously funding the archival data collection efforts for this project. Additional thanks to Bob Dilger of the CRS and former Congressman Robert Hurt's office for assistance with supplementary data collection efforts. I am extremely grateful to the following people for their excellent feedback: Jeff Jenkins, Craig Volden, Rachel Potter, Nolan McCarty, Jim Curry, the American Politics workshop at Princeton University, and all those involved with the review process at the JPP.