Introduction

Certain formations in the Ordovician System contain multiple genera of conulariids (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa), the identities and relative abundances of which show substantial paleogeographical variation, especially between low-latitude terranes such as Laurentia and high latitude Gondwanan and peri-Gondwanan terranes and areas (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996, Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022; Van Iten, Reference Van Iten2012; Robson and Young, Reference Robson and Young2013; Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020; Van Iten and Lefebvre, Reference Van Iten and Lefebvre2020). Coupled with paleogeographical variation in generic diversity (Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004), such patterns suggest that Late Ordovician conulariid faunas were highly differentiated and might also have exhibited a global latitudinal diversity gradient. To be sure, faunal migration between Ordovician terranes probably did occur (e.g., Sumrall and Zamora, Reference Sumrall and Zamora2011; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015), although it might also be worthwhile to investigate the possible role of vicariance in the origin and distribution of conulariids and other taxa. Furthermore, inspection of global paleogeographical maps (e.g., Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017, fig. 6.1, 6.2) suggests that as additional Ordovician localities receive close or closer scrutiny, range extensions of conulariids, both paleogeographical and stratigraphical, are likely to be detected. This prediction was born out, for example, by the discovery of Conulariella Bouček, Reference Bouček1928, originally known from the Lower and Middle Ordovician of northwest France and Bohemia, in the Lower Ordovician Tonggao Formation of South China (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Muir, Botting, Zhang and Li2013) and by the realization, first reported in this article, that Climacoconus sinclairi Van Iten, Fitzke, and Cox, Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996, originally described from the Upper Ordovician (Katian) Maquoketa Formation in the Upper Mississippi Valley (cratonic North America), probably also occurs in the Lower to Middle Ordovician Yeongheung Formation (Choi, Reference Choi2018) of Korea. This conclusion is based on a comparison of illustrations of this species presented by Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996) with illustrations of specimens identified as Climacoconus sp. by Choi and Jeong (Reference Choi and Jeong1990, fig. 2), the first authors to report the presence of Climacoconus Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1942 in present-day Asia. Their discovery, which extended the known stratigraphical range of Climacoconus appreciably downward, potentially involves multiple low-latitude terranes, including Laurentia, South China, and Siberia, which were probably faunally connected to each other by shallow ocean currents (see e.g., Barnes, Reference Barnes, Webby, Paris, Droser and Jacobi2004, fig. 7.1). The discovery of Conulariella in South China extends the known paleogeographical range of this genus from high southern to tropical paleolatitudes, with possible shelf (epeiric) sea connections mainly along the western margin of Gondwana (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Muir, Botting, Zhang and Li2013, fig. 5).

Detailed studies of conulariids from Ordovician strata in the Moroccan Anti-Atlas, then a part of south-polar Gondwana, have revealed that portions of the Lower Ordovician (Tremadocian–Floian) Fezouata Formation and the Upper Ordovician (Katian) Upper Tiouririne Formation contain exceptionally abundant and/or well-preserved conulariids collectively distributed among the genera Archaeoconularia Bouček, Reference Bouček and Schindewolf1939, Eoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1944, and Pseudoconularia Bouček, Reference Bouček and Schindewolf1939 (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Muir, Simões, Leme, Marques and Yoder2016b, Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022). All three genera also occur in Ordovician strata of Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia (cratonic North America plus Scotland), but in these terranes, Archaeoconularia tends to be a minor element, whereas in Morocco and other parts of south polar Gondwana, it is the dominant genus. Additionally, the genus Anaconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952, previously known from quartz siltstones and sandstones in the Upper Ordovician (Sandbian) Libeň and Letná formations in the Prague Basin of Bohemia (Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004; Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020), is present as well in quartz sandstones in the Upper Tiouririne Formation (Katian) of Morocco (Fig. 1). Also in Morocco, Archaeoconularia and Eoconularia commonly occur in monospecific mass associations, in some cases with heavy encrustation by edrioasteroids/brachiopods and/or strong preferential alignment in sandy storm deposits (Archaeoconularia; Upper Tiouririne Formation) or with evident attachment of the minute apex to conspecific individuals (Eoconularia; Fezouata Shale). In the Upper Tiouririne Formation, extremely rare, three-dimensional Pseudoconularia appear to have been buried in situ, with the apertural (oral) end of the periderm facing obliquely upward. Together with data on the paleogeographical distributions and relative abundances of other invertebrate taxa, the unique combination of numerically dominant versus subsidiary conulariid genera from the Upper Ordovician of south-polar Gondwana and peri-Gondwana has been thought to support the hypothesis of broad oceanic separation of this region from low- or mid-latitude paleocontinents, e.g., Baltica and Laurentia (Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015). However, during the late Katian to earliest Hirnantian, biogeographical links at the generic level were established between Baltica and the Prague Basin, then situated within the outer shelf of Gondwana (Lajblová and Kraft, Reference Lajblová and Kraft2018 and references therein), although probably without the formation of a migration route to the shallower shelf in the southernmost polar paleolatitudes.

Figure 1. Anaconularia anomala (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867) from the Upper Ordovician (upper Berounian–ca. Katian 1/2) Upper Tiouririne Formation in the eastern Anti-Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco (MGM 7570X): (1) lateral view of the two exposed faces, preserved as internal molds and with the slightly elevated, nonsulcate corner between them flanked by the two sulcate facial midlines; (2) detail of the facial midline and two corners of the left face in (1). Photographs oriented with apertural end of the specimen at top. Specimen preserved in a slab of quartz sandstone collected by one of the authors (JCG-M). Scale bars = 10 mm (1), 5 mm (2).

Three species of conulariids are described herein from the Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) Taddrist Formation in the central Anti-Atlas of southern Morocco (Fig. 2). Destombes (in Destombes et al., Reference Destombes, Hollard, Willefert and Holland1985) was the first author to note the presence of conulariids in this formation, and later Rábano et al. (Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014, p. 367), Zamora et al. (Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015, p. 5), and Reich et al. (Reference Reich, Sprinkle, Lefebvre, Rössner and Zamora2017, p. 739) reported the presence of ‘Exoconularia sp.’ in the strata here studied. Compared to the global record of Upper Ordovician conulariids (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022), that of the Middle Ordovician is sparse (Table 1), owing in part to the absence of this series in cratonic North America, which was then largely emergent. The present study is the first detailed and comprehensive investigation of a conulariid assemblage from any part of the Middle Ordovician of North Africa. In addition to a single species each of Archaeoconularia and Pseudoconularia, silty noduliferous shales in the lower part of the Taddrist Formation contain Glyptoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952, an extremely rare, highly autapomorphic genus that was previously known only from Upper Ordovician (Sandbian–Katian) rocks in the central and eastern parts of cratonic North America (Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996; Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004). Specimens belonging to the other two genera are most similar to species originally described from Middle and Upper Ordovician shales in the Prague Basin in the Czech Republic (see Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020 and references therein), then a part of peri-Gondwana. All of the conulariids from the Taddrist Formation are characterized by excellent preservation of the organo-phosphatic periderm, which displays with exceptional clarity the minute details of the external ornament.

Figure 2. Geographical and geological setting of the study locality: (1) map indicating the position of the Moroccan Anti-Atlas in Africa; (2) geological sketch map of the central and eastern Anti-Atlas, showing the position of the fossil locality (star); (3) sketch map of the area around the conulariid site (star). Modified after Rábano et al. (Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014).

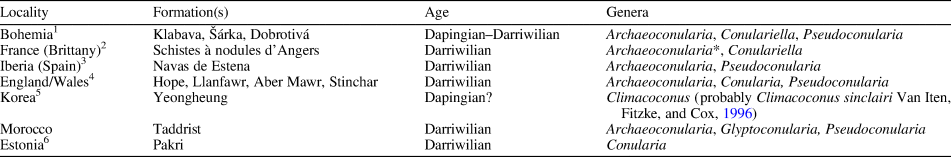

Table 1. Global occurrences of Middle Ordovician (Dapingian–Darriwilian) conulariids. 1 = Bruthansová and Van Iten (Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020); 2 = Pillet and Beaulieu (Reference Pillet and Beaulieu1998), Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Muir, Botting, Zhang and Li2013); 3 = Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Sá, Harper and Bruce2016a); 4 = Sendino and Darrell (Reference Sendino and Darrell2008), personal communication, L. Muir and J. Botting, 2021; 5 = Choi and Jeong (Reference Choi and Jeong1990); 6 = personal communication, O. Vinn, 2021; * = genus previously and incorrectly identified as Pseudoconularia by Pillet and Beaulieu (Reference Pillet and Beaulieu1998).

Geological setting

The studied conulariids were collected by one of us (JCG-M) at the Battou locality, located 23 km southwest of the city of Alnif in the Anti-Atlas Mountains of southeastern Morocco (Fig. 2). From this same locality, Rábano et al. (Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014), Zamora et al. (Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015), and Reich et al. (Reference Reich, Sprinkle, Lefebvre, Rössner and Zamora2017) described, respectively, a new illaenid trilobite, a new isocrinid crinoid, and a new cyclocystoid echinozoan. The conulariids were obtained from two beds of sandy micaceous shale bearing fossiliferous nodules, with each bed measuring to 1.5 m thick. The beds lie ~5 and 38 m, respectively, above the basal oolitic ironstone horizon (the so-called Imi-n'Tourza ironstone bed) defining the locally transgressive base of the Taddrist Formation. This stratigraphic unit was originally described by Destombes (in Destombes et al., Reference Destombes, Hollard, Willefert and Holland1985) and then mapped and redescribed more precisely in the study area by Destombes (Reference Destombes2006). According to this author, the formation is ~65 m thick, with the lowermost 30 m consisting predominantly of argillaceous sandstone grading upward into 35 m of white sandstone. The top of the formation is marked by a sharp contact with quartzite of the overlying Bou-Zeroual Formation, which despite its modest local thickness of 15 m, is an important morphostructural element in the study area.

The two noduliferous beds in the lower part of the Taddrist Formation contain identical assemblages of trilobites, mollusks, echinoderms, cnidarians, and ichnofossils. The single specimen of Glyptoconularia was collected from the lower bed, whereas the rare graptolite remains noted by Rábano et al. (Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014, p. 367) have been found only in the upper bed. The Middle Ordovician graptolite Didymograptus murchisoni (Beck in Murchison, Reference Murchison1839) occurs in strata below and above the Taddrist Formation, ranging from the top of the underlying Tachilla Formation to the basal part of the overlying Bou-Zeroual Formation, and thus places the conulariid-bearing study beds unambiguously in the upper Darriwilian (Gutiérrez-Marco et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Destombes, Rábano, Aceñolaza, Sarmiento and San José2003; Álvaro et al., Reference Álvaro, Benharref, Destombes, Gutiérrez-Marco, Hunter, Lefebvre, van Roy, Zamora, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022) at the Dw 2/3 boundary of Bergström et al. (Reference Bergström, Chen, Gutiérrez-Marco and Dronov2009). In terms of the Bohemo-Iberian chronostratigraphic scale for the southern polar paleolatitudes of Gondwana (Gutiérrez-Marco et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Sá, Rábano, Sarmiento, Garcia-Bellido, Bernárdez, Lorenzo, Villas, Jiménez-Sánchez, Colmenar and Zamora2015, Reference Gutiérrez-Marco, Sá, Garcia-Bellido and Rábano2017), the conulariid-bearing fossil beds of the Taddrist Formation are referred to the upper Oretanian regional stage.

Material and methods

The present study is based on direct examination of 14 identifiable conulariid specimens from the Taddrist Formation as well as a larger number of comparison specimens from Europe and North America in the paleontological collections of the following institutions: the Geological Survey of Canada (Ottawa; Glyptoconularia); the State University of Iowa (Iowa City; Glyptoconularia); the American Museum of Natural History (New York; Glyptoconularia); the New York State Museum (Albany; Glyptoconularia); the Hunterian Museum (Glasgow; Archaeoconularia and Pseudoconularia); The Natural History Museum (London; Archaeoconularia and Pseudoconularia); and the National Museum of the Czech Republic (Prague; Archaeoconularia and Pseudoconularia). Direct examination of European and North American specimens was supplemented by quantitative data and illustrations by Barrande (Reference Barrande1867), Bouček (Reference Bouček1928), Reed (Reference Reed1933), Sinclair (Reference Sinclair1941, Reference Sinclair1944), Begg (Reference Begg1946), Lamont (Reference Lamont1946), Hessland (Reference Hessland1949), Sayar (Reference Sayar1964), and Serpagli (Reference Serpagli1970).

Illustrated specimens from the Taddrist Formation were whitened with magnesium oxide and photographed with a millimetric scale bar using a Canon EOS 5D digital camera equipped with a Canon Compact-Macro 5D 100 mm EF. Figures including photographs were assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS6 extended. Figure 2 was assembled using Corel-Draw (ver. 12).

Anatomical terminology used herein generally follows precedents by Sinclair (Reference Sinclair1940, Reference Sinclair1942, Reference Sinclair1952), Moore and Harrington (Reference Moore, Harrington and Moore1956), Van Iten (Reference Van Iten1992), and Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996). All species are left in open nomenclature at levels between order and genus, because previously erected families and subfamilies (Moore and Harrington, Reference Moore, Harrington and Moore1956; Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952 and references therein) are probably polyphyletic (Leme et al., Reference Leme, Simões, Marques and Van Iten2008; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Burkey, Leme and Marques2014, Reference Van Iten, Muir, Simões, Leme, Marques and Yoder2016b).

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The 14 conulariid specimens from the Taddrist Formation, plus the single additional specimen from the Upper Tiouririne Formation, are housed in the paleontological collection of the Museo Geominero (Madrid, Spain) under repository numbers MGM 7555X–7568X (specimens from the Taddrist Formation) and 7570X (specimen from the Upper Tiouririne Formation). Two North American specimens cited herein are housed in the paleontological collection of the Geological Survey of Canada (Ottawa) under repository numbers GSC 94782 and 94783.

Systematic paleontology

Phylum Cnidaria Verrill, Reference Verrill1865

Subphylum Medusozoa Peterson, Reference Peterson, Larwood and Rosen1979

Class Scyphozoa Götte, Reference Götte1887

Order Conulariida Miller and Gurley, Reference Miller and Gurley1896

Genus Glyptoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952

Type species

Conularia gracile Hall, Reference Hall1847 from the Upper Ordovician (Katian 1/2) of the USA (northeastern Iowa and eastern New York State) and Canada (Saint Lawrence Valley, Québec).

Emended diagnosis

Faces and corner sulcus exhibiting well-defined, mutually contiguous, narrow longitudinal files of very short, closely spaced, straight or adaperturally arching transverse ridges (corrugations).

Remarks

The present diagnosis is more precise than that of Van Iten (Reference Van Iten and Landing1994), noting the presence of the very short transverse ridges in the corner sulcus as well as on the faces, and focuses on the single unique, gross anatomical feature (narrow longitudinal files of very short transverse ridges) of the two component species.

Glyptoconularia antiatlasica new species

Figure 3

Holotype

The holotype, reposited in the paleontological collection of the Museo Geominero in Madrid, Spain (MGM 7555X).

Figure 3. Holotype (MGM 7555X) of Glyptoconularia antiatlasica n. sp. from the Middle Ordovician (late Darriwilian 2) Taddrist Formation of southern Morocco: (1) oblique side views of two faces and the intervening corner (centered); (2) oblique side views of the other two faces and intervening corner (centered); (3) view looking down on the truncated apertural end; (4) view looking down on the truncated apical end; (5) side view of the best-preserved face in (1); (6) detail of the corner sulcus in (1), with areas preserving the crescentic transverse ridges within the sulcus indicated by black arrows; (7) detail of the area in box (a) in (1), showing patches of nonexfoliated periderm (mainly near the upper left-hand corner) and a narrow transverse band of crowded and subdued transverse ridges corresponding to an interval of probable stunted growth (near the bottom of the photograph); (8) detail of the area in box (b) in (2), showing largely nonexfoliated periderm partially covered by a thin veneer of lighter-colored, acid resistant mineral matter (facial midline indicated by white arrow); (9) detail of the area in box (c) in (2), showing the finely sulcate facial midline (white arrow). Photographs oriented with apertural end of the specimen at top. Scale bars = 5 mm (1–5), 2 mm (6–9).

Diagnosis

Glyptoconularia lacking an internal carina or other thickening at the corners of the periderm and with relatively coarse transverse ridges.

Occurrence

Silty noduliferous shales in the lower part of the Taddrist Formation (upper Oretanian regional stage, in beds equivalent to the upper Darriwilian 2 global substage) in the central Moroccan Anti-Atlas (Battou locality of Rábano et al., Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014). The geographic coordinates of the locality are Lat. 30̊55’13”N, Long. 5̊15’9”W.

Description

Single straight, three-dimensional (inflated), well-preserved partial periderm measuring ~45 mm in length (Fig. 3.1, 3.2); specimen truncated below apertural margin and far above apex (Fig. 3.3, 3.4), variably exfoliated (Fig. 3.7), largely covered by very thin crust of acid-resistant rock matrix (Fig. 3.8). Corners and facial midline sulcate, with corner sulcus (Fig. 3.6) substantially broader and deeper than very weak midline sulcus (Fig. 3.9); internal carina absent along both facial midline and corners. Faces nearly equal in width, with maximum single face width of ~14–15 mm near apertural end and minimum single face width of ~10 mm near apical end; angle of divergence of two corners bordering a given face variable, ranging from ~10° in places in apical half of specimen to essentially 0° near apertural end (Fig. 3.5). Regular longitudinal files of very short, adaperturally arching or (less frequently) straight transverse ridges generally numbering ~2–2.5 per 2 mm on faces proper (Fig. 3.6–3.9); two files present within corner sulcus; files bordered by slender longitudinal ridges that can exhibit a weak furrow where exfoliated (Fig. 3.7). Transverse ridges within a given file generally numbering ~2–4 per mm on faces proper and ~4 per mm within corner sulcus (Fig. 3.6–3.9); ends of transverse ridges in adjoining files offset or contiguous; narrow transverse bands of densely crowded and subdued transverse ridges present in a few places (Fig. 3.7); relief of transverse ridges significantly less pronounced at or near exterior surface of periderm than in deeper lamellae. Schott (apical wall) absent.

Etymology

Named after the famous fossiliferous region of the Anti-Atlas Mountain range of southern Morocco, where the type specimen comes from.

Comparisons

The type specimen of the new species is ~1.5 times broader than the type specimen of Glyptoconularia gracilis (Hall, Reference Hall1847) (see Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994, pl. 1a), previously the only known species in the genus. This difference suggests that the new specimen was originally longer than G. gracilis or that it is preserved closer to the aperture. Unlike the eight currently reposited specimens of Glyptoconularia from North America (Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996), the single specimen from Morocco preserves portions of all four faces and is three dimensional as opposed to flattened and/or fragmentary. Anatomically, G. antiatlasica n. sp. differs from G. gracilis in lacking an internal carina at the corners of the periderm and in having somewhat coarser transverse ridges, although the latter difference could be owing to the holotype of G. antiatlasica n. sp. being preserved closer to the aperture, toward which the ornament of conulariids commonly coarsens. Both species exhibit narrow transverse bands of localized crowding and diminution of the very short transverse ridges, which in the corner sulcus are arranged in two longitudinal files and are more closely spaced than on the faces (see also Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994, pl. 1c). Such bands could represent intervals of stunted extensional growth along the apertural margin.

Remarks

Glyptoconularia is a highly autapomorphic genus having a peculiar, chain-mail-like ornament that is difficult to homologize with features of other conulariids, the faces of which commonly exhibit adaperturally arcuate transverse ribs and/or transverse rows of circular nodes (Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994). One possibility, consistent with the hypothesis that the nearest relatives of conulariids are the coronate scyphozoans (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Leme, Simões, Marques and Collins2006b), is that the very short transverse ridges of Glyptoconularia are highly modified transverse ribs. Exfoliation of the holotype specimen of G. antiatlasica n. sp. has revealed that the relief of the facial ornament is appreciably greater in deep lamellae than in those near the external surface of the periderm (Fig. 3.7). This difference is not quite as apparent in specimens of G. gracilis.

According to the phylogenetic analyses of Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Burkey, Leme and Marques2014, Reference Van Iten, Muir, Simões, Leme, Marques and Yoder2016b), Glyptoconularia gracilis is a member of a subclade of conulariids that also includes the type species of Archaeoconularia, Exoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952, Baccaconularia Hughes, Gunderson, and Weedon, Reference Hughes, Gunderson and Weedon2000, and Anaconularia. Now, however, Glyptoconularia consists of two known species, making it (presumably) a minor clade in its own right.

As noted above, Glyptoconularia was previously known exclusively from Upper Ordovician strata in the central and eastern portions of cratonic North America, where it is represented by fewer than ten reposited specimens (Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996; Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004). Sendino and Darrell (Reference Sendino and Darrell2009, fig. 1) showed the genus possibly ranging upward into the Lower Jurassic, but they did not present or cite any supporting evidence. In the USA, Glyptoconularia occurs in the Elgin Member of the Maquoketa Formation (early–mid Richmondian, Katian 2; Bergström and MacKenzie, Reference Bergström, MacKenzie, Ludvigson and Bunker2005) in northeastern Iowa, and in the Dolgeville and lower Utica formations (Chatfieldian, Katian 1; Brett and Baird, Reference Brett, Baird, Mitchell and Jacobi2002) in east-central New York State. In Canada, it has been found at two localities, each of which has yielded a single reposited specimen. One of these (GSC 94782) was collected by G.W. Sinclair from “shales of Upper Trenton age on the Jacques Cartier River, near Pont Rouge, County Pontneuf” (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1948, p. 269). This site is situated ~18 km west of Québec City, Québec. The shales, which Sinclair sampled intensively in 1945, are now part of the Pont Rouge Formation in the lower Trenton Group (Clark and Globensky, Reference Clark and Globensky1973), the age of which is Chatfieldian to Edenian, or Katian 1 (Gbadeyan and Dix, Reference Gbadeyan and Dix2013; Candela, Reference Candela2015). The exact provenance of the second specimen (GSC 94783), also collected by Sinclair, is problematic. According to Sinclair (Reference Sinclair1948, p. 269), the specimen is from “a limestone of Tetreauville age, 3 miles west of Ste. Elisabeth, County Joliette [southernmost Québec].” However, according to the geological map of this area (Clark and Globensky, Reference Clark and Globensky1976), the locality as characterized by Sinclair is situated above sandstones in the middle part of the Cambrian Potsdam Group, outcrops of which are absent. The nearest Ordovician outcrops are located ~3 mi south-southwest of St. Elisabeth (the proper French name is now Sainte-Élisabeth), where strata of the Leray and Lowville formations (mid- to upper Black River Group; Sandbian) and the Ouareau and Deschambault formations (lower Trenton Group; Katian 1) are exposed. If the conulariid was found in the lower Trenton Group, then it is equivalent in age (Katian 1) to GSC 94782 from the Pont Rouge Formation. Whatever the case, based on the currently known fossil record of Glyptoconularia, which as indicated above is scant, the earliest possible age for this genus in North America is Sandbian (if it turns out to be present in the Black River Group). However, examination of acid digestion residues of carbonate rocks, a procedure which has yielded submicroscopic fragments of conulariids from the Lower Silurian Visby Beds of Gotland, Sweden (Jerre, Reference Jerre1993) and the Brainard and Elgin members of the Maquoketa Formation (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996, Reference Van Iten, Lichtenwalter, Leme and Simões2006a), might well extend the known stratigraphical range of Glyptoconularia. Indeed, among the several hundred conulariid fragments recovered by Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996) from micritic limestones in the Elgin Member, 22 belonged to Glyptoconularia. Therefore, and like many other conulariids, Glyptoconularia was susceptible to postmortem breakup.

Genus Archaeoconularia Bouček, Reference Bouček and Schindewolf1939

Type species

Conularia insignis Barrande, Reference Barrande1867 from the Lower to Upper Ordovician (upper Tremadocian to Hirnantian) of Bohemia, Czech Republic.

Archaeoconularia cf. A. exquisita (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867)

Figure 4.1–4.6

- cf. Reference Barrande1867

Conularia exquisita Barrande, p. 37, pl. 4, figs. 1–14.

- cf. Reference Bouček1928

Conularia exquisita; Bouček, p. 70, pl. 2, figs. 1–10.

- Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014

Exoconularia sp.; Rábano et al., p. 367.

- Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015

Exoconularia sp.; Zamora et al., p. 5.

- Reference Reich, Sprinkle, Lefebvre, Rössner and Zamora2017

Exoconularia sp.; Reich et al., p. 739.

Figure 4. Archaeoconularia cf. A. exquisita (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867) and Pseudoconularia cf. P. grandissima (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867) from the Middle Ordovician (late Darriwilian 2) Taddrist Formation of southern Morocco: (1–6) Archaeoconularia cf. A. exquisita: (1, 2) MGM 7556X: (1) view of a single face; (2) detail of (1), showing several pairs of subtle, discontinuous, accessory longitudinal lines or sulci straddling the facial midline in the exfoliated lower (apical) portion of the specimen; (3) MGM 7557X, detail of the facial midline and nodes; (4–6) MGM 7558X: (4) view of the two exposed faces of the specimen; (5) detail of the central portion of (4) (centered on a corner sulcus); (6) detail of the right portion of the left face in (5), showing the two-dimensional cubic closest packing of the distinct circular nodes; (7, 8) P. cf. P. grandissima (MGM 7568X): (7) view of the exposed portion of the entire specimen; (8) detail of (7), showing the distinct, longitudinally elongate nodes. Photographs oriented with apertural end of the specimens at top. Scale bars = 5 mm (1, 2, 4, 5, 7), 2 mm (3, 6, 8).

Occurrence

Silty noduliferous shales in the lower part of the Taddrist Formation (upper Oretanian regional stage, in beds equivalent to the upper Darriwilian 2 global substage) in the central Moroccan Anti-Atlas (Battou locality of Rábano et al., Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014).

Description

Specimens inflated or compressed, variably exfoliated, truncated below apertural margin and well above apex, ranging in length from ~35–60 mm (Fig. 4.1, 4.4). Faces approximately equal in width (Fig. 4.4). Corners and facial midline continuously sulcate, with the two corners bounding a given face diverging adaperturally at ~7–15°; corner and midline sulci unthickened, noncarinate, approximately equal in width and depth (Fig. 4.3). Accessory longitudinal lines or sulci absent in outermost lamellae but discernable in deeper lamellae (Fig. 4.2) as discontinuous subtle lines or furrows near facial midline. Nodes distinct (Fig. 4.6), moderately large, circular, arrayed in clearly defined, rectilinear longitudinal files and in less distinct, undulatory transverse rows which arch very gently adapertureward (Fig. 4.3, 4.5); pattern of arrangement of the nodes most closely resembling two-dimensional cubic closest packing, with 5–12 nodes per mm in both longitudinal files and transverse rows on faces proper, possibly with to ~20 per mm within corner sulcus. Schott (apical wall) absent.

Materials

MGM 7556X–7567X (12 specimens).

Remarks and comparisons

Archaeoconularia, recently redefined (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022) to include species previously assigned to Exoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952, ranges with certainty from the Lower Ordovician (Tremadocian) to the middle Silurian (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1948; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Burkey, Leme and Marques2014, Reference Van Iten, Muir, Simões, Leme, Marques and Yoder2016b). The single feature previously thought to distinguish the two genera, namely the presence in Exoconularia of ‘accessory longitudinal [sulci]’ (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952), is an artifact of exfoliation in specimens that in all other respects are most similar to the type species of Archaeoconularia. During the Early Ordovician, the genus was already present in Avalonia, Bohemia, and South China, and by Late Ordovician times, its range extended from high southern (Morocco) to tropical (Laurentia) latitudes (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022).

The specimens from the Taddrist Formation appear to be most similar to Archaeoconularia exquisita from the Middle and Upper Ordovician (Upper Darriwilian–Sandbian) of the Prague Basin (Bohemia), where it is recorded from shales in the Dobrotivá, Libeň, and Zahořany formations (Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020). Like the Taddrist Formation specimens, A. exquisita from Bohemia exhibits a pair of accessory longitudinal sulci in deep lamellae, has circular nodes (in shallow lamellae) that (locally) exhibit two-dimensional, cubic closest packing and lacks any kind of internal carina or thickening along the facial midline and corners, the angle of divergence of which is greatest near the apex. The most obvious difference between them is that in the Moroccan specimens, the distance between the nodes in the longitudinal files is nearly everywhere the same as that in the transverse rows. Although some taxonomists might regard this as grounds for erecting a new species, we here believe that alternative hypotheses, e.g., that the Moroccan specimens represent a subspecies or ecophenotypic variant of A. exquisita, cannot presently be ruled out.

Genus Pseudoconularia Bouček, Reference Bouček and Schindewolf1939

Type species

Conularia grandissima Barrande, Reference Barrande1867 from the Middle and Upper Ordovician (Dapingian to Katian) of Bohemia, Czech Republic.

Pseudoconularia cf. P. grandissima (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867)

Figure 4.7, 4.8

- cf. Reference Barrande1867

Conularia grandissima Barrande, p. 40, pl. 3, pl. 7, figs. 6–8.

- cf. Reference Bouček1928

Conularia grandissima; Bouček, p. 92, pl. 7, figs. 1–3, 15.

- cf. Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022

Pseudoconularia cf. grandissima; Van Iten et al., p. 19, figs. 6a, b, 9.

Occurrence

Silty noduliferous shales in the lower part of the Taddrist Formation (upper Oretanian regional stage, in beds equivalent to the upper Darriwilian 2 global substage) in the central Moroccan Anti-Atlas (Battou locality of Rábano et al., Reference Rábano, Gutiérrez-Marco and García-Bellido2014).

Description

Large fragment of a single face measuring ~55 mm in length along oral-aboral axis (Fig. 4.7). Sulcate corners and elevated facial midline without internal carina. Apical angle unknown. Longitudinally elongate nodes 4–6 per mm in the transverse rows and 1 or 2 per mm in the longitudinal files (Fig. 4.8). Schott (apical wall) absent.

Material

MGM 7568X (one specimen).

Remarks

Pseudoconularia, characterized by greatly elongated, longitudinally aligned nodes and an outwardly folded facial midline, is a relatively abundant component of conulariid faunas in Middle and Upper Ordovician shales of Bohemia, where it is generally associated with Archaeoconularia (Barrande, Reference Barrande1867; Bouček, Reference Bouček1928; see also Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020, table 1). In the Ordovician of Morocco, it appears to be extremely rare, with the only previously documented occurrence (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022) consisting of a single specimen from the basalmost part of the Upper Ordovician (Katian) Upper Tiouririne Formation. However, unlike specimens from Bohemia, which are invariably flattened, the two currently known Moroccan specimens are three-dimensional and the preservation of the ornament is excellent.

Van Iten et al. (Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Muir, Simões, Leme, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022) opined that Pseudoconularia might be oversplit, and indeed the single specimen here described appears to fall within the range of variation exhibited by Bohemian specimens, specifically in the geometry and spacing (both longitudinal and lateral) of the nodes. This seems hardly surprising given the proximity of Morocco to Bohemia at that time (e.g., Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017).

Discussion

Together with the results of the present investigation, the most recent studies of Lower and Middle Ordovician conulariids (Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Muir, Botting, Zhang and Li2013, Reference Van Iten, Gutiérrez-Marco, Sá, Harper and Bruce2016a, Reference Van Iten, Muir, Simões, Leme, Marques and Yoderb; Bruthansová and Van Iten, Reference Bruthansová and Van Iten2020; Van Iten and Lefebvre, Reference Van Iten and Lefebvre2020) have underscored the widespread distribution of Archaeoconularia, which ranged from high southern to low paleolatitudes (from south-polar Gondwana to South China) and was the numerically dominant genus at a number of high-latitude Gondwanan and adjacent peri-Gondwanan localities. In some of these places, e.g., Bohemia and central Spain, abundant Archaeoconularia are associated with less common (but still relatively numerous) Pseudoconularia (Table 1). The same two genera are present in Middle Ordovician dark shales of Avalonia (England and Wales), which however also contain Conularia Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1821. Conularia might be the only genus of conulariids present in the Middle Ordovician of Estonia, then a part of the paleocontinent of Baltica. Archaeoconularia is first recorded in Laurentia from the Late Ordovician (Sandbian 1) Holsten Formation of Tennessee (cratonic North America; Van Iten and Vyhlasová, Reference Van Iten, Vyhlasová, Webby, Droser and Paris2004), whereas the only record of Pseudoconularia is in the Farden Member of the Late Ordovician (Rawtheyan, Katian 4) South Threave Formation of Scotland, then situated on the eastern margin of Laurentia and facing Avalonia across the narrow Iapetus Ocean. In this famous rock unit, exposed near the town of Girvan, Pseudoconularia is associated with Archaeoconularia, Conularia, and Ctenoconularia Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1952.

As noted above, Glyptoconularia previously was known only from Upper Ordovician (Katian 1/2 and possibly Sandbian) strata, specifically dark shales and biomicrites (Van Iten, Reference Van Iten and Landing1994; Van Iten et al., Reference Van Iten, Fitzke and Cox1996) in the eastern and central portions of cratonic North America, which lay astride the paleoequator (e.g., Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017, fig. 6.6). At present, then, and based on a very small macrofossil sample, Glyptoconularia first occurs in late Darriwilian strata in Morocco, then in beds of Katian 1 (or possibly Sandbian 2) age in the eastern part of cratonic North America (Saint Lawrence Valley, Québec) and lastly in strata of Katian 2 age in the central part of this paleocontinent (upper Mississippi Valley, USA). Should additional sampling demonstrate that this sequence of first appearances is robust, then the occurrence of Glyptoconularia in the Middle Ordovician of Morocco will add to previously documented evidence (e.g., Fortey and Cocks, Reference Fortey and Cocks2003; Sumrall and Zamora, Reference Sumrall and Zamora2011; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Rahman and Ausich2015) of cross-latitudinal faunal migration from West Gondwana to Laurentia. One possible scenario is that Glyptoconularia first originated at polar latitudes on Gondwana and then dispersed into adjoining Avalonia, or (alternatively) that it existed over an area comprising North Africa and Avalonia, before this microcontinent detached from Gondwana and began to drift toward the equator during the late Early Ordovician (Cocks and Fortey, Reference Cocks, Fortey and Bassett2009; Torsvik and Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). During this northward transit, Glyptoconularia might have inhabited the cooler and deeper waters along the margin of Avalonia, finally arriving in Laurentia during the well-known ‘provincial breakdown’ (Fortey, Reference Fortey and Bruton1984) associated with the closing of the Iapetus Ocean in the Late Ordovician. More specifically, Glyptoconularia could have arrived in Laurentia along with the many other, originally high-latitude, Gondwanan/peri-Gondwanan taxa, including various bivalves, rhynchonelliform brachiopods, trilobites, and echinoderms, which invaded shallow shelf habitats near the eastern margin of Laurentia during the Sandbian-Katian transition interval (see Lefebvre et al., Reference Lefebvre, Nohejlová, Martin, Kašička, Zicha, Gutiérrez-Marco, Hunter, Álvaro, Lefebvre, van Roy and Zamora2022 and references therein). This invasion was facilitated by the upwelling of cool bottom waters over portions of Laurentia affected by crustal loading and subsidence associated with the Taconic Orogeny. In addition to Glyptoconularia, Archaeoconularia, and Pseudoconularia, both of which are known to have been present in Middle Ordovician Avalonia (Table 1), might also have arrived in Laurentia during this event. If this scenario is true, then the origin of the two species of Glyptoconularia could have been a vicariance event (rather than a consequence of dispersal), with G. gracilis possibly arising in Avalonia. Given the extreme rarity of the genus, it would not (perhaps) be surprising if it were to pop up someday as a lone specimen in an outcrop in England or Wales.

Conclusions

Recent prospecting in Ordovician strata of the Moroccan Anti-Atlas has produced a total of five genera of conulariids (Anaconularia, Archaeoconularia, Glyptoconularia, Eoconularia, and Pseudoconularia), two of which (Archaeoconularia and Eoconularia) locally occur in great abundance. Silty noduliferous shale in the lower part of the late Darriwilian Taddrist Formation (Central Anti-Atlas) contains a unique assemblage of three genera, two of which (Archaeoconularia and Pseudoconularia) are widespread in south-polar Gondwana/peri-Gondwana, and one of which (Glyptoconularia) was previously known only from the Upper Ordovician (Katian 1/2) of central and eastern cratonic North America. Low-latitude and south-polar conulariid assemblages remain distinct from one other, but now intriguing connections between these formerly widely separated faunas are even more evident. Conulariids have never received the degree of attention devoted to major groups of invertebrate fossils, but if recent developments in conulariid paleobiogeography tell us anything, it is that continued work in this area promises to contribute both to the understanding of Ordovician paleogeography and the evolutionary and ecological histories of conulariids.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. Alonso (UCM) for photography of the conulariid specimens, and to J. Cabo (Navas de Estena, Spain) and J. Martín (Collado Mediano, Spain) for their assistance to J.C.G.-M. during fieldwork in Morocco. The authors are particularly grateful to J. Bruthansová (National Museum of Prague, Czech Republic) and G. Young (Manitoba Museum Invertebrate Paleontology and University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada) for reviewing the manuscript and making many helpful remarks. Permission to examine type and other reposited specimens of Archaeoconularia, Glyptoconularia, and Pseudoconularia was granted by M. Coyne (Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa), J. Darrell and C. Sendino (The Natural History Museum, London), J. Liston (Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, UK), L. Amati (New York State Museum, Albany), N. Eldredge (American Museum of Natural History, New York), T. Adrain (University of Iowa, Iowa City), and S. Menéndez (IGME-CSIC, Madrid). Names of conulariid-bearing formations in the Middle Ordovician of England and Wales were kindly supplied by L. Muir and J. Botting (Cardiff, UK). This work was supported by Project CGL2017-87631-P of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (to J.C.G.-M.). It is also a contribution to IGCP Project 735 (Rocks and the Rise of Ordovician Life).