Introduction

The events at the Permian-Triassic boundary profoundly changed the evolutionary history of Earth's biota (Sepkoski, Reference Sepkoski1981; Erwin, Reference Erwin1994). Foraminifera were among the major faunal groups severely affected by these events, and several distinct Permian foraminiferal assemblages became extinct at the end of the Permian Period. Following this end-Permian mass extinction, the largest biotic and ecological crisis of the Phanerozoic (Raup and Sepkoski, Reference Raup and Sepkoski1982; Bambach, Reference Bambach2006; Payne and Clapham, Reference Payne and Clapham2012), recovery of foraminifera and other benthic marine organisms was delayed and interrupted by ongoing adverse environmental conditions as well as several distinct environmental crises (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Maher, Altıner, Kelley, Kump, Lehrmann, Silva-Tamayo, Weaver, Yu and Payne2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Romaniello, Algeo, Lau, Clapham, Richoz, Hermann, Smith, Horacek and Anbar2018). Due to the complexity of environmental change and biological response during the extended recovery interval, which lasted into the Middle Triassic (Hallam, Reference Hallam1991; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Summers, Rego, Altıner, Wei, Yu and Lehrmann2011; Chen and Benton, Reference Chen and Benton2012), detailed taxonomic study and fine-scale time resolution are required to establish the pattern of recovery and its relationship to environmental change.

Foraminifera are well suited to the study of recovery dynamics due to their diversity and abundance in Lower and Middle Triassic carbonates. The Triassic foraminiferal fauna of the Great Bank of Guizhou, an isolated carbonate platform of latest Permian to Late Triassic age within the Nanpanjiang Basin of south China, are particularly advantageous for this purpose. Foraminifera are abundant in many samples, distributed throughout stratigraphic sections exceeding 2000 m in thickness, and preserved in depositional environments from platform interior to basin margin (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei and Knoll2006, Reference Payne, Summers, Rego, Altıner, Wei, Yu and Lehrmann2011; Song et al., Reference Song, Wignall, Chen, Tong, Bond, Lai, Zhao, Jiang, Yan, Niu, Chen, Yang and Wang2011a).

The Great Bank of Guizhou, studied in five different measured sections, namely Dawen (PDW), Dajiang (PDJ), Middle Triassic Dajiang (MDJ), Guandao (PDG), and Upper Guandao (PUG), contains well-diversified Early to early Late Triassic benthic foraminifera assemblages. Under the Phylum Foraminifera, the studied foraminifera assemblages belong to classes Miliolata, Textulariata, Fusulinata, Nodosariata, and to an uncertain class housing the involutinid- and robertinid-type foraminifera.

During the second half of the last century, several authors described and documented Early to Middle Triassic foraminiferal taxa (Ho, Reference Ho1959; Luperto, Reference Luperto1965; Pantić, Reference Pantić1965; Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić1966; Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969; Baud et al., Reference Baud, Zaninetti and Brönnimann1971, Reference Baud, Brönnimann and Zaninetti1974; Premoli Silva, Reference Premoli Silva1971; Brönnimann and Zaninetti, Reference Brönnimann and Zaninetti1972; Brönnimann et al., Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti, Bozorgnia and Huberb, Reference Brönnimann, Cadet and Zaninetti1973a, Reference Brönnimann, Cadet and Zaninettib, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti, Moshtaghian and Huberc, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti, Moshtaghian and Huber1974; Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Bozorgnia and Huber1972a, Reference Zaninetti, Brönnimann and Baudb, Reference Zaninetti, Brönnimann and Baudc, Reference Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Huber and Moshtaghian1978, Reference Zaninetti, Rettori and Martini1994; Efimova, Reference Efimova1974; Gazdzicki et al., Reference Gazdzicki, Trammer and Zwidzka1975; Stampfli et al., Reference Stampfli, Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Jenny-Deshusses and Stampfli-Vuille1976; Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Gazdzicki and Smit, Reference Gazdzicki and Smit1977; Dağer, Reference Dağer1978a; Trifonova, Reference Trifonova1978a, Reference Trifonovab, Reference Trifonovac, Reference Trifonova1992, Reference Trifonova1993, Reference Trifonova1994; Čatalov and Trifonova, Reference Čatalov and Trifonova1979; Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981; Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Borza and Samuel1983; He, Reference He1984, Reference He1988, Reference He1993; Orovecz-Scheffer, Reference Orovecz-Scheffer1987; Benjamini, Reference Benjamini1988; He and Wang, Reference He and Wang1990; He and Cai, Reference He and Cai1991; Altıner and Koçyiğit, Reference Altıner and Koçyiğit1993; Rettori et al., Reference Rettori, Angiolini and Muttoni1994; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995). Some selected genera directly from the late Paleozoic in the definition of their new taxa, such as Rectocornuspira (now Postcladella), Cornuspira (previously described as Cyclogyra), Permodiscus, Endothyra, and Earlandia, therefore studies relating Early Triassic foraminiferal taxa to the Permian-Triassic mass extinction event were carried out only rarely prior to the end of the last century (Nakazawa et al., Reference Nakazawa, Kapoor, Ishii, Bando, Okimura and Tokuoka1975; Altıner et al., Reference Altıner, Baud, Guex and Stampfli1980; Taraz et al., Reference Taraz, Golshani, Nakazawa, Shimizu, Bando, Ishii, Murata, Okimura, Sakagami, Nakamura and Tokuoka1981; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Chen, Wang, Rui, Liao, Bando, Ishii, Nakazawa and Nakamura1984; Neri and Pasini, Reference Neri and Pasini1985; Pasini, Reference Pasini1985; Broglio Loriga et al., Reference Broglio Loriga, Neri, Pasini and Posenato1988; Cirilli et al., Reference Cirilli, Pirini Radrizzani, Ponton and Radrizzani1998).

As the importance of the Permian-Triassic boundary mass extinction within the evolution of Phanerozoic marine ecosystems became clear (Sepkoski, Reference Sepkoski1981; Raup and Sepkoski, Reference Raup and Sepkoski1982; Wignall and Hallam, Reference Wignall and Hallam1992; Erwin, Reference Erwin1993), research into the causes and mechanisms of the mass extinction and controls on subsequent biotic recovery accelerated (Erwin, Reference Erwin1994, Reference Erwin2007; Rampino and Adler, Reference Rampino and Adler1998; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Wang, Wang, Shang, Cao and Erwin2000; Tong and Shi, Reference Tong and Shi2000; Leven and Korchagin, Reference Leven and Korchagin2001; Wignall and Newton, Reference Wignall and Newton2003; Altıner et al., Reference Altıner, Groves and Özkan-Altıner2005; Groves and Altıner, Reference Groves and Altıner2005; Kaiho et al., Reference Kaiho, Kajiwara, Chen and Gorjan2006; Song et al., Reference Song, Tong, Zhang, Wang and Chen2007, Reference Song, Wignall, Chen, Tong, Bond, Lai, Zhao, Jiang, Yan, Niu, Chen, Yang and Wang2011a, Reference Song, Wignall, Tong and Yin2013; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Feng, Lai, Baud and Tong2007; Algeo et al., Reference Algeo, Chen, Fraiser and Twitchet2011; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Summers, Rego, Altıner, Wei, Yu and Lehrmann2011; Rego et al., Reference Rego, Wang, Altıner and Payne2012). As part of this previous research, the evolution of foraminifera in the Lower to Middle Triassic stratigraphy has been studied to understand extinction and recovery dynamics. Foraminiferal paleontologists and stratigraphers started to trace and document foraminifera along measured sections encompassing the Permian-Triassic boundary and to include data from other disciplines in order to improve their foraminifera-based chronology (Broglio Loriga and Cassinis, Reference Broglio Loriga, Cassinis, Sweet, Zunyi, Dickins and Hongfu2003; Ünal et al., Reference Ünal, Altıner, Yilmaz and Özkan-Altıner2003; Altıner et al., Reference Altıner, Groves and Özkan-Altıner2005; Groves et al., Reference Groves, Altıner and Rettori2005, Reference Groves, Rettori, Payne, Boyce and Altıner2007; Mohtat-Aghai and Vachard, Reference Mohtat-Aghai and Vachard2005; Angiolini et al., Reference Angiolini, Carabelli, Nicora, Crasquin-Soleau, Marcoux and Rettori2007; Théry et al., Reference Théry, Vachard, Dansart, Álvaro, Aretz, Boulvain, Munnecke, Vachard and Vennin2007; Vuks, Reference Vuks2007; Galfetti et al., Reference Galfetti, Bucher, Martini, Hochuli, Weissert, Crasquin-Soleau, Brayard, Goudmand, Brühwiler and Goudun2008; Maurer et al., Reference Maurer, Rettori and Martini2008; Korchagin, Reference Korchagin2011; Krainer and Vachard, Reference Krainer and Vachard2011; Nestell et al., Reference Nestell, Kolar-Jurkovšek, Jurkovšek and Aljinović2011; Song et al., Reference Song, Tong and Chen2011b, Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015, Reference Song, Tong, Wignall, Luo, Tian, Song, Huang and Chu2016, Reference Song, Wignall and Dunhill2018; Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015).

The purpose of this study is to give a comprehensive taxonomic account of the Early to Middle Triassic foraminifera from the Great Bank of Guizhou, including descriptions of one new genus and three new species recovered. In addition, the occurrence patterns of the taxa along measured stratigraphic sections are used to develop a foraminiferal biostratigraphic framework for the Lower Triassic through Anisian interval. This biostratigraphic study excludes the Ladinian and Carnian stages of the measured sections because the foraminiferal data recovered from these stages are more fragmentary due to a combination of unfavorable facies and poor preservation in collected samples. The occurrence patterns are further used to assess the recovery of foraminifera following the end-Permian mass extinction within an Early to Middle Triassic timescale calibrated by conodonts.

Geological setting and studied stratigraphic sections

The foraminiferal study is based on samples from five stratigraphic sections measured on outcrops of the Great Bank of Guizhou (GBG), an isolated carbonate platform of latest Permian to earliest Late Triassic age located in the Nanpanjiang Basin of the Yangtze Block, southern China (Fig. 1). The Nanpanjiang Basin was a deep-marine embayment in the southern margin of the south China tectonic block and is bordered by the Yangtze Platform, a vast shallow-marine carbonate platform that stretched across south China. The GBG initiated in the latest Permian during a relative rise in sea level that drowned much of the Yangtze Platform (Fig. 1.1; Lehrmann, Reference Lehrmann1993; Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Wei and Enos1998, Reference Lehrmann, Payne, Enos, Montgomery, Wei, Yu, Xiao and Orchard2005, Reference Lehrmann, Donghong, Enos, Minzoni, Ellwood, Orchard, Zhang, Wei, Dillett, Koenig, Steffen, Druke, Druke, Kessel and Newkirk2007, Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004, Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei and Knoll2006). Uppermost Permian skeletal carbonates of the Wujiaping Formation underlie the platform interior, whereas fine-grained siliciclastics of the uppermost Permian Dalong Formation underlie the Permian/Triassic transition beneath Lower Triassic slope facies. During the Early Triassic, the depositional setting of the GBG was a low-relief bank with oolite shoals developed at the margin, a shallow subtidal to peritidal interior, and slopes dominated by hemipelagic carbonate mud intercalated with thin carbonate turbidites and debris flows shed from the margin (Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Wei and Enos1998, Reference Lehrmann, Payne, Enos, Montgomery, Wei, Yu, Xiao and Orchard2005). Recently, reconstruction of the GBG in the latest Permian to Early Triassic interval has been partly revised by Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Lehrmann, Yu, Jost, Meyer, Lau, Altıner, Li, Minzoni, Schaal and Payne2020), who defined three stages of development. These authors considered the latest Permian–Smithian interval as the initiation and low-relief bank stages, and the Smithian to late Spathian interval as the aggrading and steepening stage. The Lower Triassic platform interior consists of shallow-marine carbonates of the Daye Formation overlain by dolomitized shallow-marine carbonates of the Anshun Formation. The Lower Triassic shales, micritic carbonates, carbonate turbidites, and allodapic breccias of the slope belong to the Luolou Formation. In the Middle Triassic, Anisian Tubiphytes reefs rimmed the outer margin and slope of the GBG while peritidal conditions continued in the interior (Fig. 1.2). The platform subsequently developed a high-relief escarpment during Ladinian. The escarpment profile continued until the early Carnian, when the GBG drowned due to accelerated tectonic subsidence and was subsequently buried by siliciclastic turbidites (Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Wei and Enos1998, Reference Lehrmann, Payne, Enos, Montgomery, Wei, Yu, Xiao and Orchard2005). The Middle Triassic shallow-marine carbonates of the platform interior belong to the Yangliujing Formation, and the Middle Triassic slope carbonates belong to the Xinyang Formation. The Upper Triassic siliciclastic turbidites of the Bianyang Formation filled the remaining accommodation in the basin and, ultimately, buried the platform top.

Figure 1. (1) Early Triassic paleogeographic map (Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Wei and Enos1998; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004). Hash pattern indicates the Nanpanjiang Basin and brick pattern indicates the Yangtze Platform and GBG. (2) Schematic cross section of the Great Bank of the Guizhou, illustrating the locations of Dawen, Dajiang, Middle Triassic Dajiang, Guandao, and Upper Guandao sections within the platform architecture.

The studied stratigraphic sections span a range of depositional environments. Three of the studied sections—the Dawen, Dajiang, and Middle Triassic Dajiang sections—are located in the platform interior (Fig. 1.2). Both the Dawen and Dajiang sections cover the stratigraphic interval from Griesbachian to Smithian. The Middle Triassic Dajiang section consists of four short sections (~20 m) measured at intervals through a part of the thick carbonate platform spanning from the Pelsonian (mid Anisian) to Ladinian. The Guandao and Upper Guandao sections, representing the slope and basin-margin environments, cover the entire Griesbachian–lower Carnian interval (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Stratigraphic columns of measured sections. Timescale is constrained by conodont occurrence data and physical stratigraphic and carbon isotope correlations between the basin margin and the platform interior (Payne et al., Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004; Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015; Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Lehrmann, Yu, Jost, Meyer, Lau, Altıner, Li, Minzoni, Schaal and Payne2020). 1–12 = Biozones of foraminifera (for biozone names see Fig. 21). Gray vertical bar indicates intervals devoid of foraminifera.

Materials

From the stratigraphic sections measured in the Great Bank of Guizhou, we collected a total of 1106 samples for lithostratigraphy, facies analysis, isotope stratigraphy, conodont and foraminiferal taxonomy, and biostratigraphy. From the samples displaying fossil fragments and suitable carbonate facies, 598 thin sections were prepared for the foraminifera, 246 of which contained at least one foraminifer. The total number of foraminifera specimens is >2500, of which 351 were illustrated in the figures of this paper.

Foraminifera recovered from the samples were first used in a genus-level study by Payne et al. (Reference Payne, Summers, Rego, Altıner, Wei, Yu and Lehrmann2011). These authors carried out a study on the Early–Middle Triassic trends in diversity, evenness, and size of the foraminifers to investigate the tempo and mode of biotic recovery. The current study concentrates, with a different scope and resolution, on species-level taxonomic description with many illustrations, construction of a new biostratigraphic scheme calibrated by conodonts, and a discussion of species-level recovery of Early–Middle Triassic foraminifera, with attention to phyletic relationships.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types, figures, and other specimens examined in this study are deposited in the thin section laboratory of the Department of Geological Sciences, Stanford University, with the following catalog abbreviations: Dawen (PDW), Dajiang (PDJ), Middle Triassic Dajiang (MDJ), Guandao (PGD) and upper Guandao (PUG) sections.

Systematic paleontology

Demir Altıner and Jonathan L. Payne

As indicated by Vachard (Reference Vachard2016, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018) the current classification of foraminifera based on wall microstructure disagrees with the results of molecular phylogenetic studies of extant species (e.g., Pawlowski et al., Reference Pawlowski, Holzmann and Tyszka2013). However, molecular results remain difficult to reconcile with the Paleozoic–Mesozoic fossil record. In this study, the Triassic foraminifera of the Great Bank of Guizhou have been classified at first in distinct populations at species rank, and then placed into reasonable categories at the genus level based on wall structure and composition and other morphological characters. Despite uncertainties in higher taxonomic ranks, we consider most of the families used in the Triassic foraminiferal paleontology to be adequate for recognized genera and species. However, intermediate taxonomic ranks, including superfamily, suborder, and order, are less stable in their use across studies and have not been used in this study. For the largest groups of foraminifera, classified based on wall microstructure and assigned class rank, we have largely followed Vachard (Reference Vachard2016, Reference Vachard, Lucas and Shen2018) and Cavalier-Smith (Reference Cavalier-Smith2002, Reference Cavalier-Smith2003), the latter of whom demonstrated that foraminifera constitute a phylum or subphylum.

Class Miliolata Saidova, Reference Saidova1981

Remarks

One of the dominant groups of Early–Middle Triassic foraminifera on the Great Bank of Guizhou is the bilocular Miliolata, consisting of Cornuspiridae, Arenovidalinidae, Meandrospiridae, Hoyenellidae, and Agathamminidae and the primitive multilocular miliolid families Ophthalmiidae, Quinquelloculinidae, and Galeanellidae.

Family Cornuspiridae Schultze, Reference Schultze1854

Subfamily Cornuspirinae Schultze, Reference Schultze1854

Genus Postcladella Krainer and Vachard, Reference Krainer and Vachard2011

Postcladella kalhori (Brönnimann, Zaninetti, and Bozorgnia, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a)

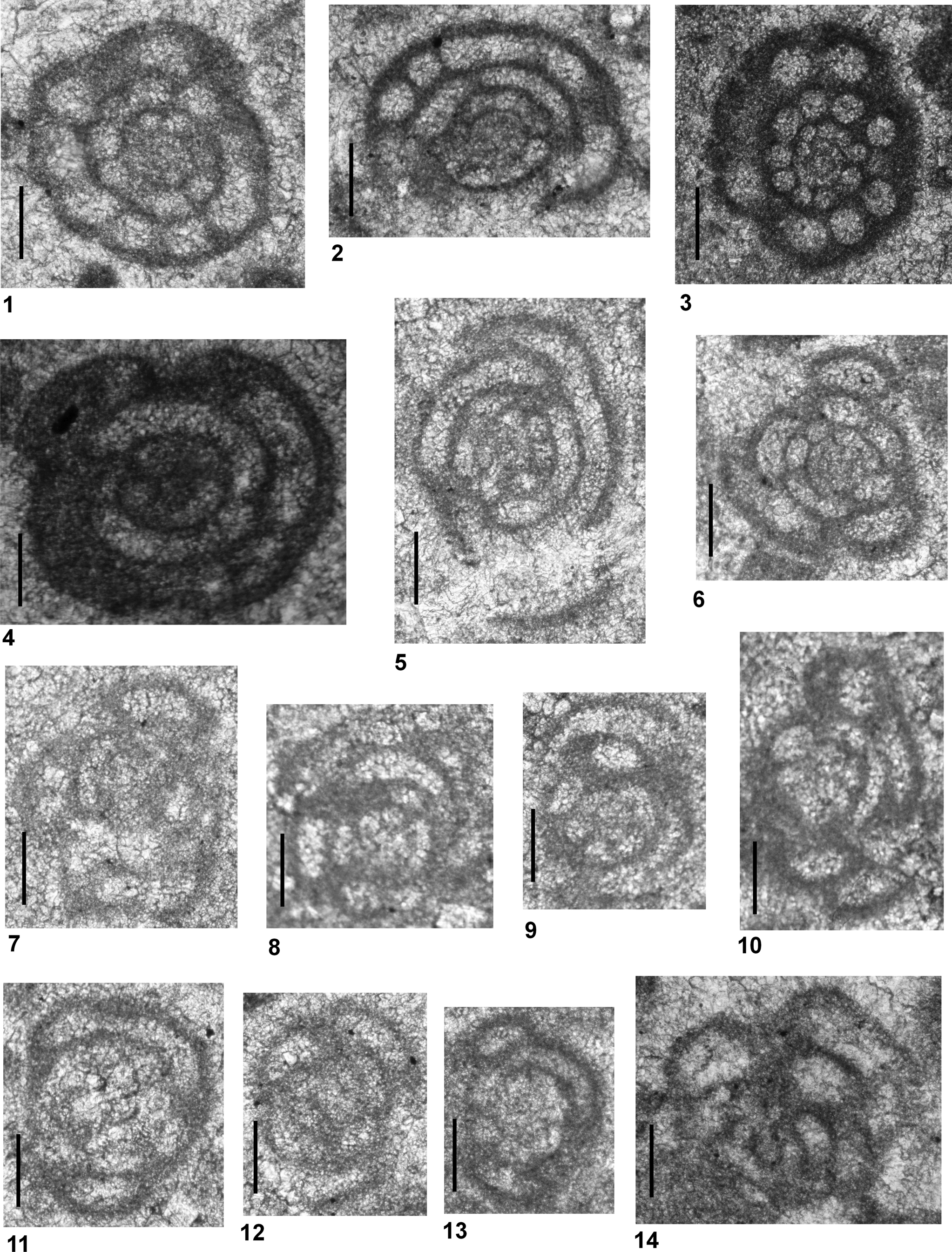

Figure 3.1–3.26

Figure 3. All specimens are from Dawen (PDW) and Dajiang (PDJ) sections. (1–26) Postcladella kalhori (Brönnimann, Zaninetti, and Bozorgnia, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a); (27–38) Postcladella grandis (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981). (1, 2, 22) PDW-011; (3) PDJ-164; (4, 7, 18–21, 25, 27, 30–32, 34) PDJ-174; (5) PDJ-178; (6, 17, 23, 24, 29) PDW-108; (8, 9) PDJ-157; (10, 11) PDW-099; (12, 28, 33, 36) PDW-118; (13) PDJ-162; (14) PDJ-200; (15) PDW-087; (16) PDJ-161; (26) PDW-123; (35) PDJ-170; (37) PDJ-158; (38) PDW-126. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Remarks

There is currently disagreement regarding the taxonomy of Early Triassic cornuspirin taxa, which is one of the most common foraminiferal groups in basal Triassic strata. Two of the frequently cited taxa, Rectocornuspira kalhori and Cyclogyra? mahajeri, were described by Brönnimann et al. (Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a). The primary difference between these two taxa, commonly encountered in axial sections, is that the lumen of the final whorl of C.? mahajeri overlaps laterally onto the previous coil. Brönnimann et al. (Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a) added that this character distinguishes this species from the axially slender and strongly biumbilicate planispiral stage of R. kalhori. This approach was altered by Gaillot and Vachard (Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007, p. 84), who considered Early Triassic Rectocornuspira as an uncoiled Cornuspira and stated that ‘Rectocornuspira would correspond to Cornuspira with a morphological adaptation, more or less developed, depending on the local or regional ecological parameters.’ This interpretation did not take into account the morphological difference between the kalhori and mahajeri populations.

Although the reasons given by Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011) were correct for the creation of their new genus Postcladella for the kalhori population, these authors did not consider the morphological difference between kalhori and mahajeri populations as a valid criterion for distinguishing between the species, and therefore synonymized these two taxa under Postcladella. More recently, Nestell et al. (Reference Nestell, Kolar-Jurkovšek, Jurkovšek and Aljinović2011), describing the foraminifera from the Permian–Triassic transition in Slovenia, rejected Postcladella of Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011), illustrated all P. kalhori populations as ‘Cornuspira’ mahajeri, and considered Postcladella (given as ‘Rectocornuspira’) to be a teratologic form of Cornuspira, following Gaillot and Vachard (Reference Gaillot and Vachard2007). In Nestell et al. (Reference Nestell, Nestell, Ellwood, Wardlaw, Basu, Ghosh, Lan, Rowe, Hunt, Tomkin and Ratcliffe2015), the kalhori population took priority over the mahajeri population, and was illustrated and described under the agglutinated genus Ammodiscus. The basis of this taxonomic reassignment was explained as the absence of calcium carbonate and the presence of a significant amount of elemental carbon, along with oxygen and silica in the walls of kalhori specimens. In our view, however, these authors did not sufficiently discuss the diagenetic processes that could have affected the tests of the kalhori specimens. Specifically, it is possible that the specimens illustrated from the washed conodont residues do not display the originally preserved wall. Therefore, in this study, we consider Postcladella as a valid genus and Postcladella kalhori as a porcelaneous form belonging to the Class Miliolata.

Cornuspirins recognized in the Chinese samples consist of three species within the studied interval. Among these taxa, the individuals assigned to the Postcladella kalhori population (Fig. 3.1–3.26) are nearly identical to types described under the genus Rectocornuspira by Brönnimann et al. (Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a); however, the size variation in the Chinese forms is much greater. The diameter of the coiled portion reaches up to 160 μm, as noted previously in Altıner and Zaninetti (Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981). The number of whorls, reaching to 2.5 or 3 in some specimens, is also greater than in the type specimens, which display 1.5–2 whorls. Previously, P. kalhori was generally reported from the microbialite-bearing successions from the base of the Triassic (Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995 and the references therein). In the more recent literature, P. kalhori has been reported as Cornuspira mahajeri from the Griesbachian of Antalya Nappes, Turkey (Angiolini et al., Reference Angiolini, Carabelli, Nicora, Crasquin-Soleau, Marcoux and Rettori2007); Alborz Mountains, Iran (Angiolini et al., Reference Angiolini, Checconi, Gaetani and Rettori2010); western Slovenia (Nestell et al., Reference Nestell, Kolar-Jurkovšek, Jurkovšek and Aljinović2011); the Dead Sea region, Jordan (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Stephenson, Nicora, Rettori, Borlengi and Perri2016); and from the Nanpanjiang basin, south China (Bagherpour et al., Reference Bagherpour, Bucher, Baud, Brosse, Vennemann, Martini and Goudun2017). Hips (Reference Hips1996) reported P. kalhori from the Spathian of northern Hungary, but did not satisfactorily illustrate these forms. The associated forms illustrated as Cyclogyra mahajeri were misidentified and belong to Pseudoammodiscus (formerly known as Ammodiscus). The same problem has also occurred in the description of material from Israel. Korngreen et al. (Reference Korngreen, Orlov-Labkovsky, Bialik and Benjamini2013) mentioned the presence of P. kalhori in strata of later Early Triassic age, but these forms were not illustrated in their study. Postcladella also has been partly misidentified in Rossignol et al. (Reference Rossignol, Bourquin, Hallot, Poujol, Debard, Martini, Villeneuve, Cornée, Brayard and Roger2018) from northern Vietnam. Their figure 11C and 11E illustrated specimens that are Glomospirella vulgaris Ho, Reference Ho1959, not Postcladella (Rossignol et al., Reference Rossignol, Bourquin, Hallot, Poujol, Debard, Martini, Villeneuve, Cornée, Brayard and Roger2018, fig. 11E is associated with Arenovidalina sp.).

In both the Dawen and Daijiang sections, P. kalhori ranges from the base of Griesbachian to the lowermost Dienerian (Figs. 5, 6). The stratigraphic range in the Chinese sections is indistinguishable from the range given in Rettori (Reference Rettori1995). In several recent studies, including Crasquin-Soleau et al. (Reference Crasquin-Soleau, Richoz, Marcoux, Angiolini, Nicora and Baud2002, Reference Crasquin-Soleau, Marcoux, Angiolini, Richoz, Nicora, Baud and Bertho2004) from the Antalya Nappes, Turkey, Song et al. (Reference Song, Tong, Chen, Yang and Wang2009, Reference Song, Tong, Wignall, Luo, Tian, Song, Huang and Chu2016), Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chen, Wang, Tong, Song and Chen2011), and Dai et al. (Reference Dai, Song, Wignall, Jia, Bai, Wang, Chen and Tian2018) from south China, and Kolar-Jurkovšek et al. (Reference Kolar-Jurkovšek, Jurkovšek, Nestell and Aljinović2018) from western Slovenia, the stratigraphic range of P. kalhori has been partially studied in stratigraphic sections covering only a few meters of the base of Triassic and reported as Griesbachian based on conodont zones. Galfetti et al. (Reference Galfetti, Bucher, Martini, Hochuli, Weissert, Crasquin-Soleau, Brayard, Goudmand, Brühwiler and Goudun2008) reported the full range as Griesbachian to Dienerian from the Nanpanjiang Basin, similar to the range given in this study. Some authors reported this interval simply as Induan (Insalaco et al., Reference Insalaco, Virgone, Courme, Gaillot, Kamali, Moallemi, Loftpour and Monibi2006 from southern Iran; Powell et al., Reference Powell, Nicora, Perri, Rettori, Posenato, Stephenson, Masri, Borlenghi and Gennari2019 from Jordan). Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011) reported the stratigraphic distribution of P. kalhori from the Werfen Formation (southern Austria) also as Induan, based on Broglio Loriga et al. (Reference Broglio Loriga, Góczán, Haas, Lenner, Neri, Orovecz-Scheffer, Posenato, Szabó and Makk1990), and added that this species also could be present in the Olenekian. However, neither in Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011) nor other studies have properly illustrated the kalhori population from well-dated Olenekian strata.

Postcladella grandis (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981)

Figures 3.27–3.38, 4.1–4.16

Figure 4. All specimens are from Dawen (PDW) and Dajiang (PDJ) sections. (1–16) Postcladella grandis (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981); (17) Cornuspira mahajeri? (Brönnimann, Zaninetti, and Bozorgnia, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a). (1, 17) PDW-108; (2) PDJ-178; (3) PDW-102; (4, 6) PDW-096; (5) PDJ-164; (7, 10, 11, 13–15) PDW-118; (8, 16) PDW-123; (9) PDJ-158; (12) PDJ-157. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Remarks

The other species that we recognize in the Chinese material also belongs to the genus Postcladella. Introduced by Altıner and Zaninetti (Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981) from Turkey, R. kalhori f. grandis was raised by Lehrmann et al. (Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015) to a species rank under the genus Postcladella. Cyclogyra nov. sp.? of Resch (Reference Resch1979) and Rectocornuspira reschi of Orovecz-Scheffer (Reference Orovecz-Scheffer1983) were considered as synonyms of Postcladella grandis (Figs. 3.27–3.38, 4.1–4.16). Although Rettori (Reference Rettori1995) considered Postcladella grandis to be a synonym of P. kalhori, the former species is easily distinguished from the latter by the larger size of the tubular chamber, which is nearly twice that of P. kalhori in every step of its ontogeny, and the larger diameter of the coiled portion of the test. In addition, the first appearance of P. grandis always postdates that of P. kalhori in south China, Turkey, and the Transdanubian Range of Hungary (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981; Orovecz-Scheffer, Reference Orovecz-Scheffer1987; Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015). Postcladella grandis was also illustrated or described from other studies in the Tethyan belt. For example, the specimens illustrated as R. kalhori in Brönnimann et al. (Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a, pl. 4, fig. 15) and Cyclogyra? mahajeri in Brönnimann et al. (Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a, pl. 4, fig. 18) should be assigned to P. grandis. Forms from Austria illustrated by Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011, pl. 5, figs. 9, 10, 14) are referable to P. grandis. Cyclogyra? mahajeri illustrated from the Alborz Mountains, Iran by Stampfli et al. (Reference Stampfli, Zaninetti, Brönnimann, Jenny-Deshusses and Stampfli-Vuille1976) is P. grandis. In addition, P. grandis has been illustrated as both C.? mahajeri and R. kalhori in Orovecz-Scheffer (Reference Orovecz-Scheffer1987).

The stratigraphic range of P. grandis is much shorter than the range of P. kalhori (Figs. 5, 6). The first occurrence of P. grandis is higher in the Griesbachian in China than in Turkey (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981), and its last occurrence is just below the Griesbachian-Dienerian boundary in the Dawen and Daijiang sections. The stratigraphic range of C. mahajeri? is similar to that of P. kalhori, as stated by Rettori (Reference Rettori1995). Forms close to this species are present both in Dawen and Dajiang sections, within the interval corresponding to the stratigraphic range of P. grandis.

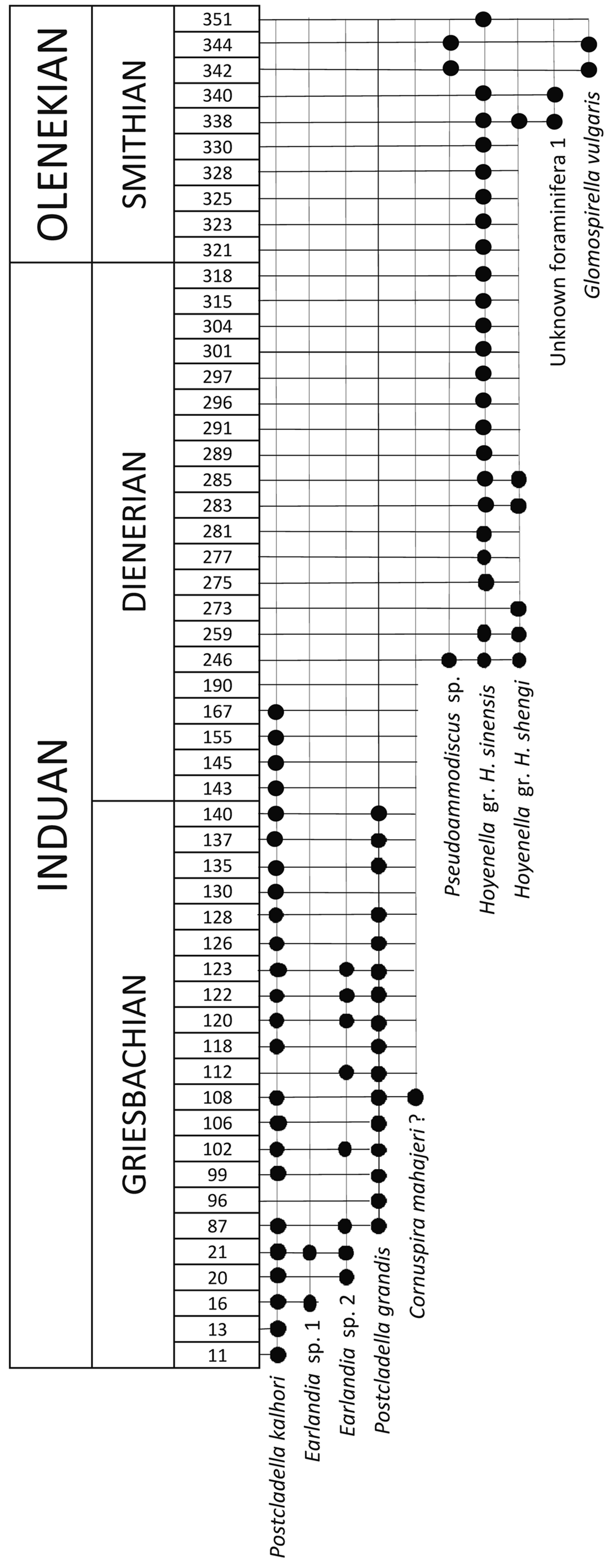

Figure 5. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa at Dawen measured section (barren samples not shown). Because the goal of the figure is to illustrate the occurrences and co-occurrences of species for the purpose of chronostratigraphy, only fossiliferous samples are included along with sample numbers. For stratigraphic positions of illustrated samples, we refer readers to Figure 2.

Figure 6. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa at Dajiang measured section (barren samples not shown). In this section, samples numbered less than 44 were collected from the Permian strata and are not considered in this study.

Genus Cornuspira Schultz, Reference Schultze1854

Cornuspira mahajeri? (Brönnimann, Zaninetti, and Bozorgnia, Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a)

Figure 4.15

Remarks

Rarely recorded forms assigned to Cornuspira mahajeri? (Fig. 4.15) in this study differ from the types (given as Cyclogyra? mahajeri by Brönnimann et al., Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti and Bozorgnia1972a) in having slightly larger dimensions of the test and the lumen of the final whorl covering the previous whorl in a less-pronounced way.

Subfamily Calcivertellinae Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich, Tappan and Moore1964

Genus Planiinvoluta Leischner, Reference Leischner1961

Planiinvoluta? mesotriasica Baud, Zaninetti, and Brönnimann, Reference Baud, Zaninetti and Brönnimann1971

Figure 7.1–7.7

Figure 7. All specimens are from Guandao (PGD), Upper Guandao (PUG) and Middle Triassic Dajiang (MDJ) sections. (1–7) Planiinvoluta? mesotriasica Baud, Zaninetti, and Brönnimann, Reference Baud, Zaninetti and Brönnimann1971; (8–13) Arenovidalina weii n. sp.; (14, 15) Arenovidalina abriolense (Luperto, Reference Luperto1965); (16–20) Meandrospira pusilla (Ho, Reference Ho1959); (21–24, 26) Meandrospira cheni (Ho, Reference Ho1959); (25, 27–32) Meandrospira dinarica Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić1966. (1) MDJ-025; (2) PUG-065; (3, 5) PUG-085; (4) MDJ-039; (6, 32) PUG-054; (7) MDJ-035; (8) PGD-131; (9) PGD-112 (holotype); (10) PGD-111; (11) PGD-109; (12, 13) PGD-096; (14) PUG-051; (15) PUG-089; (16) MDJ-007; (17, 19) PGD-174; (18) PUG-012; (20, 31) PUG-009; (21) PGD-151; (22) PGD-168; (23) PGD-154; (24, 26) PGD-157; (25) PGD-226; (27) MDJ-019; (28) PUG-027; (29) PGD-215; (30) PUG-023. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Remarks

The subfamily Calcivertellinae, a group of tubular, porcelaneous foraminifera, is represented only by Planiinvoluta? mesotriasica (Fig. 7.1–7.7) in the studied material. The size of the proloculus, diameter of the tubular chamber, and the test are similar to those of the types originally described by Baud et al. (Reference Baud, Zaninetti and Brönnimann1971). However, the genus attribution remains unclear because the individuals belonging to this species never display a proper planispirally enrolled second chamber as described by Leischner (Reference Leischner1961). In the recent literature, P.? mesotriasica has been clearly illustrated in Altıner and Koçyiğit (Reference Altıner and Koçyiğit1993) and Okay et al. (Reference Okay, Altıner and Kiliç2015) from the Anisian of central and northern Anatolia (Turkey), and in Fugagnoli and Posenato (Reference Fugagnoli and Posenato2004) from northern Italy. The specimens illustrated as Meandrospira? sp. from western Kyushu, Japan, by Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Martini and Zaninetti2005) are most probably sections of P.? mesotriasica. The stratigraphic range of P.? mesotriasica is from Bithynian to Illyrian in the Upper Guandao section and Illyrian in the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Figs. 8–10).

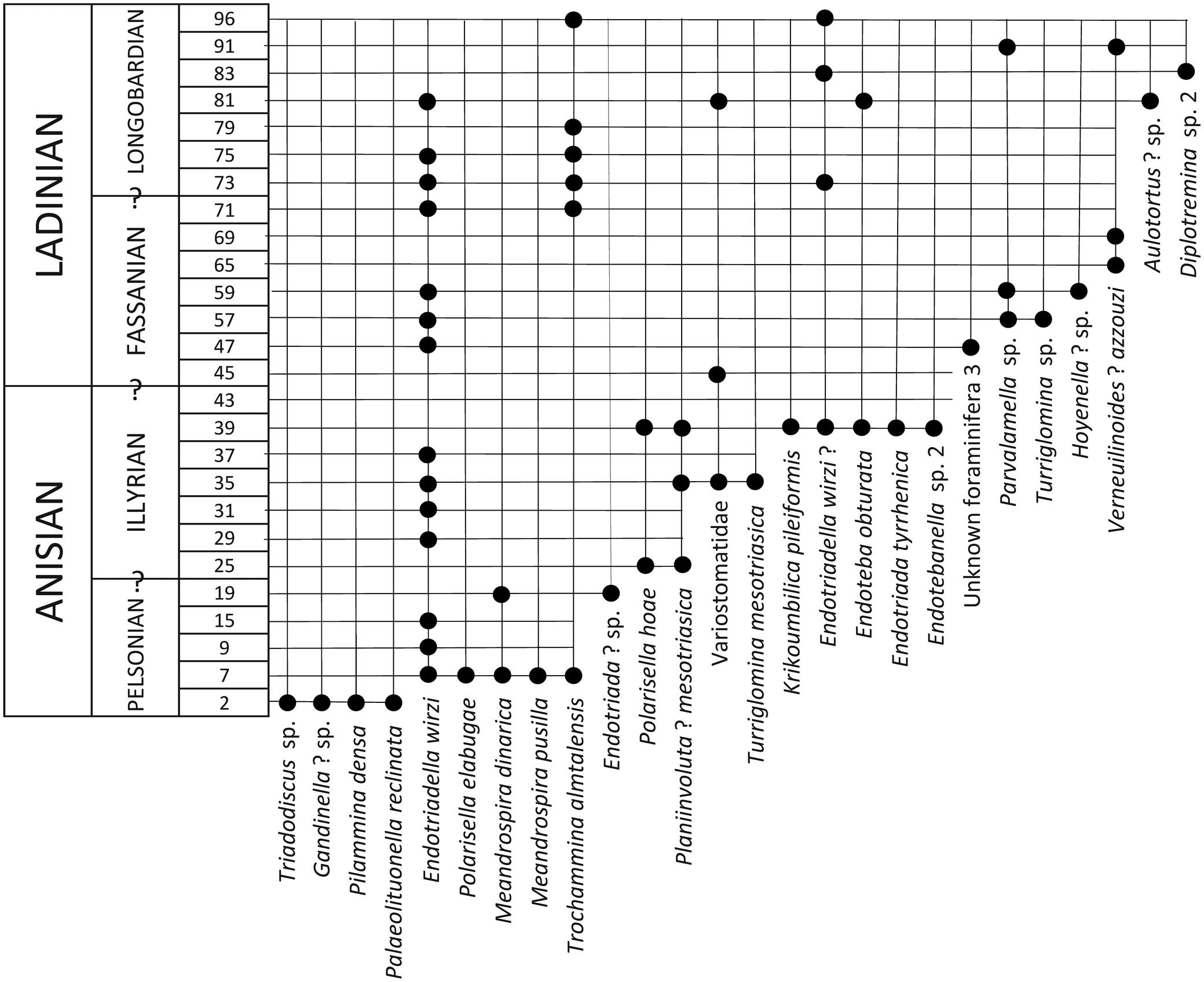

Figure 8. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa in the lower part of Upper Guandao section (barren samples not shown). OL.: Olenekian; Spat.: Spathian.

Figure 9. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa in the upper part of Upper Guandao section (barren samples not shown).

Figure 10. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa at Middle Triassic Dajiang measured section (barren samples not shown).

Family Arenovidalinidae Zaninetti and Rettori in Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Rettori, He and Martini1991

Subfamily Arenovidalininae Zaninetti and Rettori in Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Rettori, He and Martini1991

Genus Arenovidalina Ho, 1959

Type species

Arenovidalina chialingchiangensis Ho, Reference Ho1959, from the Triassic Chialingkiang Limestone of South Szechuan, China.

Arenovidalina abriolense (Luperto, Reference Luperto1965) Figure 7.14, 7.15

Remarks

Two species from the subfamily Arenovidalininae, Arenovidalina abriolense (Luperto, Reference Luperto1965) (Fig. 7.14, 7.15) and Arenovidalina weii n. sp. (Fig. 7.8–7.13), are present in the Chinese sections. Arenovidalina abriolense, previously defined as a Permian form and thus placed under the genus Hemigordius by Luperto (Reference Luperto1965), was later placed in the genus Ophthalmidum by Ciarapica et al. (Reference Ciarapica, Cirilli, Martini, Rettori, Salvini-Bonnard and Zaninetti1990). Consisting of a proloculus followed by an undivided second chamber, the abriolense population does not carry the primitively developed multilocular character of the genus Ophthalmidium, and is therefore placed under the genus Arenovidalina in this study. Arenovidalina abriolense differs from the two other, similar-looking species of Arenovidalina, A. chialingchiangensis Ho, Reference Ho1959 and A. amylovoluta Ho, Reference Ho1959 (Ho, Reference Ho1959; Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Okay et al., Reference Okay, Altıner and Kiliç2015) in having a more tightly enrolled and slowly growing second chamber. In Senowbari-Daryan et al. (Reference Senowbari-Daryan, Zühlke, Bachtädt and Flügel1993), Ophthalmidium (=Arenovidalina) chialingchiangensis illustrated from the Anisian of the northern Dolomites, Italy, belongs to A. abriolense. Some specimens illustrated as Ophthalmidium spp. from the Anisian of western Kyushu, Japan, are referable to A. abriolense (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini and Zaninetti2005). Ophthalmidium abriolense illustrated in Velledits et al. (Reference Velledits, Péró, Blau, Senowbari-Daryan, Kovács, Piros, Pocsai, Szúgyi-Simon, Dumitrica and Palfy2011) from NE Hungary is Eoophthalmidium tricki Langer, Reference Langer1968. The stratigraphic range of A. abriolense is Anisian (Aegean) to Carnian (Cordevolian) in the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9). The description of the other Arenovidalina species, A. weii n. sp., is given below.

Arenovidalina weii new species

Figure 7.8–7.13

- ?1990

Arenovidalina amylovoluta Ho; Baroz et al., pl. 4, figs. 8, 9.

Holotype

PGD-112 (Fig. 7.9).

Diagnosis

A laterally compressed Arenovidalina species with a maximum of four whorls, becoming evolute in the late stage of the ontogeny.

Occurrence

Smithian, Guandao section of the Great Bank of Guizhou, Nanpanjiang Basin, south China, Sample PGD-112 (Figs. 2, 11).

Figure 11. Stratigraphic occurrences of foraminiferal taxa at Guandao measured section (barren samples not shown).

Description

Test is laterally compressed and consists of a relatively large proloculus and a maximum number of four planispiral whorls rapidly increasing in height. The coiling, involute in the earlier 2.5 whorls, becomes evolute in the last 1.5 whorls (Fig. 7.9). A possible dimorphism is present in the population (Fig. 7.10). In microspheric forms, the number of whorls increases to five and the test displays a slight deviation in the axis of coiling in the initial 1–2 whorls. The wall is originally porcelaneous and appears slightly granular due to recrystallization. It is relatively thicker when compared with the volume of the test.

Etymology

This new species is dedicated to Dr. Jiayong Wei of the Guizhou Geological Survey, China, who made great contributions to the understanding of the geology of the Nanpanjiang Basin.

Materials

Samples PGD-96, 109, 111, 112, 131 (Smithian). More than 20 specimens. Six of these specimens, including the holotype, are illustrated in Figure 7.8–7.13.

Microfossil association

In the samples collected from the Smithian, Arenovidalina weii n. sp. is associated with Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis, H. gr. H. shengi, Glomospirella vulgaris, Pseudoammodiscus sp., Praetriadodiscus zaninettiae Altıner and Payne, Reference Altıner and Payne2017, and P. tappanae Altıner and Payne, Reference Altıner and Payne2017.

Dimensions

Diameter of proloculus: 50–55 μm. Diameter of test: 360–420 μm. Width of test: 100–115 μm. W/D ratio: 0.24–0.32. Height of last whorl (only lumen): 55–60 μm. Thickness of wall: 10–14 μm.

Remarks

Arenovidalina weii n. sp. is probably the oldest Arenovidalina species known in the Triassic stratigraphy. It differs from the two other well-known species, A. chialingchiangensis and A. amylovoluta, in having a nearly parallel-sided, compressed test and few whorls, which increase rapidly in height and become evolute toward the end of the ontogeny. The specimens illustrated as Arenovidalina amylovoluta by Baroz et al. (Reference Baroz, Martini and Zaninetti1990) from Greece probably belong to our A. weii n. sp. population. These forms are similar to A. weii n. sp. in having highly compressed axial profiles and evolute last whorls, but they contain more whorls and a smaller proloculus. Arenovidalina sp. illustrated by Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1996) from the Anisian of the Kanto Mountains, Japan, is also characterized by involute earlier whorls and evolute later whorls. However, the D/W ratio is greater in the Japanese forms. Finally, the microfacies photographs illustrated by Song et al. (Reference Song, Tong, Wignall, Luo, Tian, Song, Huang and Chu2016, fig. 9c) from the Smithian of south China contain sections of A. weii n. sp.

Family Meandrospiridae Saidova, Reference Saidova1981 emend. Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Ciarapica, Martini, Salvini-Bonnard and Rettori1987a

Subfamily Meandrospirinae Saidova, Reference Saidova1981 emend. Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Ciarapica, Martini, Salvini-Bonnard and Rettori1987a

Remarks

Meandrospirin foraminifera of the Great Bank of Guizhou are classified under two genera, Meandrospira and Meandrospiranella. The validity of the former genus in the Triassic stratigraphy has been questioned recently by Ueno et al. (Reference Ueno, Miyahigashi and Martini2018), who suggested the replacement of Meandrospira with Citaella, which was originally described by Premoli Silva (Reference Premoli Silva1964). These authors concluded that Citaella, Meandrospira, and Streblospira are meandrospiral homeomorphs that appeared independently at different times in the evolutionary history of the class Miliolata. In contrast, we argue that Triassic Meandrospira was derived as a Lazarus taxon from Permian Streblospira, as argued by Groves and Altıner (Reference Groves and Altıner2005) and Altıner et al. (Reference Altıner, Groves and Özkan-Altıner2005). Recently, Streblospira (S. minima) Kotljar et al., Reference Kotljar, Zakharov, Koczyrkevica, Chedija, Vuks and Guseva1984 has been illustrated from the Changhsingian of western Slovenia by Kolar-Jurkovšek et al. (Reference Kolar-Jurkovšek, Jurkovšek, Nestell and Aljinović2018). Previous findings of Streblospira within middle and upper Permian strata (Kotljar et al., Reference Kotljar, Zakharov, Koczyrkevica, Chedija, Vuks and Guseva1984; Şahin et al., Reference Şahin, Altıner and Ercengiz2012) demonstrate that the genus was not confined to lower Permian strata, as was supposed by Ueno et al. (Reference Ueno, Miyahigashi and Martini2018). Furthermore, we consider that the ‘absence’ of Meandrospira in post-Anisian to Jurassic rocks may not indicate the ‘phylogenetical isolation’ of ‘Citaella’ in the Early to Middle Triassic. Tubular foraminifera might survive as rare members of communities, confined to narrow ecological and/or environmental niches before becoming more common again in a much younger time interval, as in Meandrospira (Charollais et al., Reference Charollais, Brönnimann and Zaninetti1966; Altıner, Reference Altıner1991; Ivanova and Kołodziej, Reference Ivanova and Kołodziej2010). Because the ancestor of Cretaceous Meandrospira is not known from the Cretaceous, we take the more conservative route and continue to use Meandrospira in Triassic foraminiferal taxonomy.

Genus Meandrospira Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1946

Type species

Meandrospira washitensis Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1946, from the Lower Cretaceous Washita Group of southern Oklahoma and northern Texas, USA.

Meandrospira pusilla (Ho, Reference Ho1959)

Figure 7.16–7.20

Remarks

From the Meandrospira population in the Chinese material, the well-known species M. pusilla (Ho, Reference Ho1959) (Fig. 7.16–7.20), characterized by 1.5–2 whorls and a tightly coiled spire consisting of 8–9 sections of the zig-zag bends of the meandering second tubular chamber in the last whorl, is nearly identical to the holotype described by Ho (Reference Ho1959). Meandrospira pusilla was extensively reported from the whole Tethyan Belt (Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995). More recently, it has been reported from southern Austria by Krainer and Vachard (Reference Krainer and Vachard2011) and from Jordan by Powell et al. (Reference Powell, Stephenson, Nicora, Rettori, Borlengi and Perri2016). Some of the specimens illustrated as M. pusilla from the Qingyan section of south China by Song et al. (Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015) belong to M. dinarica Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić1966.

Meandrospira pusilla ranges from the Spathian to the Bithynian in the Guandao and Upper Guandao sections (Figs. 8, 11). It is also present in the Pelsonian of the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Fig. 10). In the Smithian of the Daijiang section (Fig. 6), forms identified as ‘transitional to Meandrospira’ could also be included in the population of M. pusilla. Meandrospira cheni is strictly confined to the Spathian in the Guandao section (Fig. 11). Meandrospira? deformata has been recognized from the Pelsonian to lower Illyrian of the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 8).

Meandrospira cheni (Ho, Reference Ho1959)

Figure 7.21–7.24, 7.26

Remarks

Meandrospira cheni (Ho, Reference Ho1959) (Fig. 7.21–7.24, 7.26), a similarly coiled but larger form than M. pusilla, differs from M. pusilla in having fewer (6–8) zig-zag bends of the meandering second tubular chamber. Our specimens are nearly identical to forms illustrated as the cheni population in Ho (Reference Ho1959) and He (Reference He1993) from China. Some of the M. pusilla sections illustrated from Julfa, northwestern Iran, by Baud et al. (Reference Baud, Brönnimann and Zaninetti1974) belong to M. cheni. The specimen illustrated from Hydra (Greece) by Rettori et al. (Reference Rettori, Angiolini and Muttoni1994) is probably an Endoteba section. Meandrospira cheni also has been reported from the Spathian of Israel (Korngreen et al., Reference Korngreen, Orlov-Labkovsky, Bialik and Benjamini2013) and the northern Arab Emirates (Maurer et al., Reference Maurer, Rettori and Martini2008).

Meandrospira dinarica Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić1966

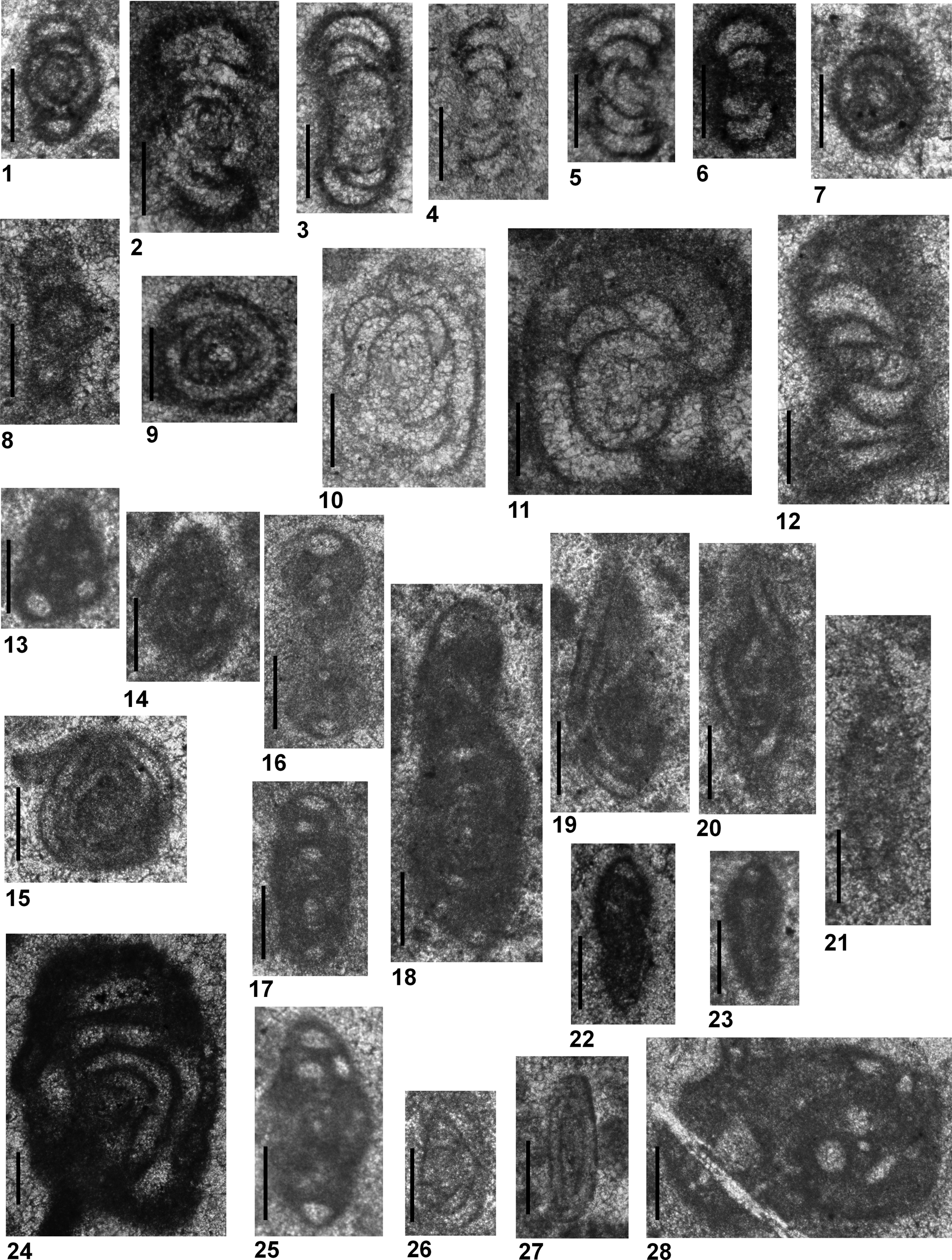

Figures 7.25, 7.27–7.32, 12.1–12.4

Figure 12. All specimens are from Guandao (PGD) and Upper Guandao (PUG) sections. (1–4) Meandrospira dinarica Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić, Reference Kochansky-Devidé and Pantić1966 (5–13) Meandrospira? enosi n. sp.; (14) Meandrospira? deformata Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967. (1) PUG-037; (2) PUG-031; (3) PGD-212; (4) PUG-019; (5–12) PGD-176; (13) PGD-174; (14) PUG-054. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Remarks

The other well-established species of Meandrospira, M. dinarica (Figs. 7.25, 7.27–7.32, 12.1–12.4), consisting of 8–10 sections of the second tubular chamber in the last whorl, is characterized by rectangular outlines of the sections of the tubular chamber in the equatorial plane. Meandrospira dinarica is one of the most widely cited Anisian species in the Tethyan Belt (Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995). In more recent literature, it has been reported from the Anisian of Japan (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1996; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini and Zaninetti2005), Thailand (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini, Rettori, Zaninetti, Ratanasthien, Saegusa and Nakaya2006), Laos (Miyahigashi et al., Reference Miyahigashi, Hara, Hisada, Nakano, Charoentitirat, Charusiri, Khamphoveng, Martini and Ueno2017), Vietnam (Martini et al., Reference Martini, Zaninetti, Cornée, Villeneuve, Tran and Ta1998), northern Italy (Fugagnoli and Posenato, Reference Fugagnoli and Posenato2004; Berra et al., Reference Berra, Rettori and Bassi2005), and Hungary (Velledits et al., Reference Velledits, Péró, Blau, Senowbari-Daryan, Kovács, Piros, Pocsai, Szúgyi-Simon, Dumitrica and Palfy2011). Korchagin (Reference Korchagin2008) identified M. dinarica as M. cheni from Pamirs. Tian et al. (Reference Tian, Tong, Algeo, Song, Song, Chu, Shi and Bottjer2014), based on Song et al. (Reference Song, Wignall, Chen, Tong, Bond, Lai, Zhao, Jiang, Yan, Niu, Chen, Yang and Wang2011a), reported earliest M. dinarica from the Smithian–Spathian interval of south China. This unusual report is probably the result of a taxonomic misidentification. Both M. pusilla and M. cheni might have been misidentified as M. dinarica (see also Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015).

Meandrospira dinarica, whose first appearance nearly coincides with the Olenekian-Anisian boundary, extends from the Aegean to the Pelsonian in the Guandao and Upper Guandao sections (Figs. 8, 11). It also occurs in the Pelsonian of the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Fig. 10). From the Meandrospiranella side, M. cf. M. samueli is found in the uppermost Aegean, whereas M. irregularis? occurs in the Pelsonian to lowermost Illyrian of the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 8).

Meandrospira? deformata Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967

Figures 12.14, 13.1–13.4

Figure 13. All specimens are from Dawen (PDW), Dajiang (PDJ), Middle Triassic Dajiang (MDJ), Guandao (PGD), and Upper Guandao (PUG) sections. (1–4) Meandrospira? deformata Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967; (5) Meandrospiranella cf. M. samueli Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967; (6) Meandrospiranella irregularis? Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967; (7–9) Turriglomina mesotriasica (Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1968); (10–13) Turriglomina cf. T. magna (Urošević, Reference Urošević1977); (14) Turriglomina carnica Dağer, Reference Dağer1978b; (15–33) Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis (Ho, Reference Ho1959). (1, 4) PUG-067; (2, 3) PUG-069; (5) PUG-014; (6) PUG-057; (7) PUG-089; (8) PUG-091; (9) MDJ-35; (10) PUG-055; (11) PUG-077; (12) PUG-075; (13) PUG-085; (14) PUG-145; (15, 33) PDW-285; (16) PGD-101; (17) PGD-087; (18) PDW-281; (19) PDW-275; (20, 30) PGD-090; (21) PDW-259; (22) PGD-151; (23) PGD-176; (24) PDJ-302; (25) PDJ-313; (26–28) PDJ-303; (29) PDJ-281; (31) PDW-315; (32) PGD-168. Scale bars = 100μm.

Remarks

Meandrospira? deformata Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967 (Figs. 12.14, 13.1–13.4), a doubtful member of the genus Meandrospira, is characterized by an irregularly coiled meandering second chamber throughout its ontogeny. After the type description of Salaj et al. (Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967), M.? deformata has been reported from the Anisian of Slovenia (Flügel et al., Reference Flügel, Ramovš and Bucur1994), Japan (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1996), Pamirs (Korchagin, Reference Korchagin2008), and more recently from Laos (Miyahigashi et al., Reference Miyahigashi, Hara, Hisada, Nakano, Charoentitirat, Charusiri, Khamphoveng, Martini and Ueno2017) as Citaella? deformata.

Meandrospira? enosi new species

Figure 12.5–12.13

Holotype

PGD-176 (Fig. 12.5).

Diagnosis

A meandrospirin species characterized by an initial Meandrospira stage followed by oscillating whorls, but not zig-zag bends, of the tubular chamber.

Occurrence

Spathian, Guandao section of the Great Bank of Guizhou, Nanpanjiang Basin, south China, PGD-176 (Figs. 2, 11).

Description

Following a globular and small proloculus, the initial stage of the new species is typically coiled like a Meandrospira with three whorls. The height of the tubular chamber increases rather rapidly in the final whorl of this stage and, generally, seven sections of zig-zag bends of the second tubular chamber are present in the last whorl. Later in the ontogeny, coiling changes its style and direction. This stage is characterized by 1.5 oscillating whorls, generally arranged perpendicular to the axis of coiling of the Meandrospira stage. The wall is porcelaneous, similar to the other Meandrospira species in this study.

Etymology

This new species is dedicated to Prof. Dr. Paul Enos from the University of Kansas, USA, for his contributions to the Permian–Triassic carbonates in China.

Materials

Samples PGD-171, 176, 178, 181 (Spathian). More than 20 specimens. Nine of these specimens are illustrated in Figure 12.5–12.13.

Microfossil association

In the Spathian samples, the new species co-occurs with Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis, Meandrospira pusilla, Meandrospira cheni, Trochammina sp. 1, Verneuilinoides? azzouzi (Salaj, Reference Salaj1978), Endoteba bithynica Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Martini, Rettori and Zaninetti1994, Endotebanella kocaeliensis (Dağer, Reference Dağer1978b), Krikoumbilica pileiformis He, Reference He1984, Variostoma sp. 2, and Diplotremina sp. 2.

Dimensions

Diameter of proloculus: 36–50 μm. Diameter of test: 280–340 μm. Height of the last whorl (only lumen): 36–40 μm. Thickness of wall: 15–18 μm.

Remarks

Meandrospira? enosi n. sp., probably derived from M. cheni, is easily distinguished from the other Meandrospira species of the Lower–Middle Triassic by the coiling in the second stage of its ontogeny, characterized by oscillating whorls of the second tubular chamber arranged perpendicular to the coiling axis of the Meandrospira stage. The genus Meandrovoluta, described by Fugagnoli et al. (Reference Fugagnoli, Giannetti and Rettori2003) from the Liassic of the southern Alps, Italy, is morphologically close to M.? enosi n. sp. The coiling style of our new species differs from Meandrovoluta in two ways: (1) Meandrovoluta is characterized by a more irregularly coiled, widely meandering tubular chamber in the second stage of its morphology, whereas M.? enosi n. sp. is characterized by a tubular chamber coiled simply in oscillating whorls; and (2) the Meandrospira-like stage is irregular and complicated in the holotype of Meandrovoluta, whereas this stage is more Meandrospira-like in the M.? enosi n. sp. population, even morphologically close to M. cheni. We remain uncertain whether a new genus should be created to house forms such as the enosi population within meandrospirin foraminifera.

Genus Meandrospiranella Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967

Meandrospiranella cf. M. samueli Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967

Figure 13.5

Remarks

Species doubtfully attributed to Meandrospiranella are rare and sporadic in the Chinese material. Meandrospiranella cf. M. samueli Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967 (Fig. 13.5) is an incomplete specimen lacking the uncoiled portion. Flügel et al. (Reference Flügel, Ramovš and Bucur1994) illustrated a form similar to ours from the Pelsonian of Slovenia. Zaninetti et al. (Reference Zaninetti, Brönnimann and Baud1972c), from Switzerland, and Baroz et al. (Reference Baroz, Martini and Zaninetti1990), from Greece, illustrated specimens very similar to the holotype. Meandrospiranella samueli illustrated by Velledits et al. (Reference Velledits, Péró, Blau, Senowbari-Daryan, Kovács, Piros, Pocsai, Szúgyi-Simon, Dumitrica and Palfy2011) from the Anisian of Hungary probably belongs neither to the genus nor to the species of this form. The illustrated specimen is characterized by a granular wall, biserial chambers in the uncoiled portion, and an unrecognizable coiled portion. Meandrospiranella irregularis? Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967 (Fig. 13.6) is characterized by a well-defined, broadly meandering, uncoiled portion that has not been illustrated in the holotype (Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967).

Subfamily Turriglomininae Zaninetti in Limogni et al., Reference Limogni, Panzanelli-Fratoni, Ciarapica, Cirilli, Martini, Salvini-Bonnard and Zaninetti1987

Genus Turriglomina Zaninetti in Limogni et al., Reference Limogni, Panzanelli-Fratoni, Ciarapica, Cirilli, Martini, Salvini-Bonnard and Zaninetti1987

Remarks

Characterized by an initial meandrospiroid or glomospiroid stage followed by a tightly coiled helicoidal stage consisting of numerous whorls, the genus Turriglomina is composed of three species in the Triassic of the Great Bank of Guizhou. Turriglomina mesotriasica (Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1968) (Fig. 13.7–13.9), as described by Koehn-Zaninetti (Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969), consists of a slender test with up to 14 tightly coiled whorls. Turriglomina mesotriasica has been extensively reported from the Triassic deposits of the Tethyan Belt (Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995). In more recent literature, Emmerich et al. (Reference Emmerich, Zamparelli, Bechstädt and Zühlke2005) reported this form from the Illyrian to Ladinian of the Latemar (Dolomites, Italy). Song et al. (Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015) illustrated this species (given as Turritellella mesotriasica) from the Qingyan section of south China. However, the form illustrated by Song et al. (Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015) does not display the slender aspect of T. mesotriasica and should be corrected as T. conica He, Reference He1984 from Guizhou, south China. Turriglomina cf. T. magna (Urošević, Reference Urošević1977) (Fig. 13.10–13.13), a relatively larger form, is always found as incomplete oblique sections. Here we note that T. guangxiensis described by He and Cai (Reference He and Cai1991) from the Middle Triassic of Guangxi, China, is a synonym of T. magna. Turriglomina carnica Dağer, Reference Dağer1978b is very rare and recognized in oblique sections with spiny extensions from the periphery of the test (Fig. 13.14).

Turriglomina mesotriasica ranges from the upper Pelsonian to the base of the Carnian (Cordevolian) in the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9). It occurs also in the Illyrian of the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Fig. 10). Turriglomina cf. T. magna has been recognized in the upper Pelsonian–Illyrian, whereas T. carnica occurs rarely in the Carnian of the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9)

Turriglomina mesotriasica (Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1968)

Figure 13.7–13.9

Remarks

Koehn-Zaninetti (Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1968) published a condensed version of Koehn-Zaninetti (Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969) with the same title in which she reported the new taxa that she discovered in this paper. Although these taxa were also described as new in 1969 (her main work) we give priority to the 1968 publication. See additional remarks under Genus Turriglomina.

Turriglomina cf. T. magna (Urošević, Reference Urošević1977)

Figure 13.10–13.13

Remarks

See Remarks under Genus Turriglomina.

Remarks

See Remarks under Genus Turriglomina.

Remarks

A variety of sections belonging to the genus Hoyenella, characterized by an ovoid to discoidal test with a large globular proloculus, an early stage coiled in several different planes, and a planispirally coiled later stage, have been grouped under two distinct and two questionable populations.

Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis (Ho, Reference Ho1959)

Figures 13.15–13.33, 14.1

Remarks

Although nearly all early hoyenellid forms of Early to Middle Triassic age (Glomospirella sinensis var. rara Ho, Reference Ho1959, Glomospirella facilis Ho, Reference Ho1959, and Glomospirella shengi Ho, Reference Ho1959; Glomospirella elbursorum Brönnimann et al., Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti, Bozorgnia and Huber1972b and Palaeonubecularia minuta Brönnimann et al., Reference Brönnimann, Zaninetti, Bozorgnia and Huber1972b; and Calcitornella gebzensis Dağer, Reference Dağer1978b) have been synonymized under Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis by Rettori (Reference Rettori1994, Reference Rettori1995), we distinguish two main hoyenellid groups in the material of the Great Bank of Guizhou. Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis (Figs. 13.15–13.33, 14.1) differs from H. gr. H. shengi (Fig. 14.2–14.9) by its more voluminous irregularly coiled early stage, whereas in the H. gr. H. shengi population, planispiral coiling in the later stage is more prominent. In addition to taxa synonymized under H. gr. H. sinensis by Rettori (Reference Rettori1995), we also consider Glomospira roesingi Blau et al., Reference Blau, Wenzel, Senff and Lukas1995, described from the Scythian–Anisian of Germany, as a synonym of H. gr. H. sinensis based on the similarity of the wall composition and the coiling of the tubular chamber.

Figure 14. All specimens are from Dawen (PDW), Dajiang (PDJ), Guandao (PGD), and Upper Guandao (PUG) sections. (1) Hoyenella gr. H. sinensis (Ho, Reference Ho1959); (2–9) Hoyenella gr. H. shengi (Ho, Reference Ho1959); (10) Hoyenella? sp. 1; (11, 12) Hoyenella? sp. 2; (13, 14) Agathammina? sp.; (15) Ophthalmidium exiguum Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969; (16–18) Ophthalmidium sp. 1; (19–21) Ophthalmidium sp. 2; (22, 23) Ophthalmidium sp. 3; (24) Ophthalmidium? sp. 5; (25) Ophthalmidium sp. 4; (26) Gsollbergella? sp.1; (27) Gsollbergella? sp. 2; (28) Galeanella sp. (1, 7) PGD-090; (2, 6) PDW-273; (3) PUG-009; (4, 5) PDW-259; (8) PGD-096; (9) PDJ-302; (10) PUG-027; (11) PGD-226; (12) PUG-101; (13, 14, 17–20, 23) PUG-143; (15) PUG-109; (16, 25) PUG-137; (21) PUG-131; (22) PUG-047; (24) PGD-217; (26) PUG-097; (27) PUG-087; (28) PUG-139. Scale bars = 100 μm.

In the Dajiang and Dawen sections (Figs. 5, 6), H. gr. H. sinensis and H. gr. H. shengi make their first appearances in the upper Dienerian strata. In the Guandao section these species range up to the Bithynian (Fig. 11), whereas in the Upper Guandao section they range into the Illyrian (Fig. 8). In Israel (Korngreen et al., Reference Korngreen, Orlov-Labkovsky, Bialik and Benjamini2013), Kashmir Valley, India (Baud and Bhat, Reference Baud and Bhat2014), and south China (Galfetti et al., Reference Galfetti, Bucher, Martini, Hochuli, Weissert, Crasquin-Soleau, Brayard, Goudmand, Brühwiler and Goudun2008) the first appearance of H. gr. H. sinensis also has been reported as Dienerian in successions that are well dated by conodonts.

Hoyenella gr. H. shengi (Ho, Reference Ho1959)

Figure 14.2–14.9

Remarks

Two other, questionable hoyenellid species, H.? sp. 1 (Fig. 14.10) and H.? sp. 2 (Fig. 14.11, 14.12), characterized by more complicated coiling of the tubular chamber, are rare. Hoyenella? sp. 1 has been recorded from the uppermost Bithynian in the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 8).

Hoyenella? sp. 2

Figure 14.11, 14.12

Remarks

See Remarks under Hoyenella? sp. 1. Hoyenella? sp. 2 ranges from the Bithynian to lower Ladinian (Fassanian) in the Guandao and Upper Guandao sections (Figs. 9, 11).

Family Agathamminidae Ciarapica, Cirilli, and Zaninetti in Ciarapica et al., Reference Ciarapica, Cirilli, Passeri, Trincianti and Zaninetti1987

Genus Agathammina Neumayr, Reference Neumayr1887

Agathammina? sp.

Figure 14.13, 14.14

Remarks

Oblique sections of some coiled bilocular forms with a probable Quinqueloculina-like arrangement of the tubular chamber are reported as Agathammina? sp. (Fig. 14.13, 14.14) from the Upper Guandao section. Such forms range from the Ladinian (Fassanian) to the Carnian (Cordevolian) (Fig. 9).

Family Ophthalmidiidae Wiesner, Reference Wiesner1920

Genus Ophthalmidium Kübler and Zwingli, Reference Kübler and Zwingli1870

Ophthalmidium exiguum Koehn-Zaninetti, Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969

Figure 14.15

Remarks

Identical to forms described by Koehn-Zaninetti (Reference Koehn-Zaninetti1969), Ophthalmidium exiguum is characterized by tests of small dimensions, thin wall, and chambers half-whorl long in the adult. It has been recorded from the Longobardian (Upper Ladinian) of the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 9). Typical sections of O. exiguum have been illustrated from the Ladinian to Carnian of Turkey (Altıner and Zaninetti, Reference Altıner and Zaninetti1981) and China (He and Wang, Reference He and Wang1990). Forms reported more recently from the Anisian of the southern Alps (Italy) by Faletti and Ivanova (Reference Faletti and Ivanova2003) and the Qingyan section of south China by Song et al. (Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015) do not belong to the population of O. exiguum. They should be attributed to the lineage of Eoophthalmidium tricki, described by Langer (Reference Langer1968; see also Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Okay et al., Reference Okay, Altıner and Kiliç2015). The rest of the ophthalmidiid fauna consists of five different populations.

Ophthalmidium sp. 1

Figure 14.16–14.18

Remarks

Ophthalmidium sp. 1 is recognized in robust axial sections, tends to uncoil toward the end of its ontogeny, and ranges from Longobardian (Ladinian) to Cordevolian (Carnian) in the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 9).

Ophthalmidium sp. 2

Figure 14.19–14.21

Remarks

Ophthalmidium sp. 2, characterized by an elongate ellipsoidal test with narrow tubular chambers and a slightly sigmoidal coiling, also ranges from Longobardian to Cordevolian in the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 9).

Ophthalmidium sp. 3

Figure 14.22, 14.23

Remarks

Small and slightly biumbilicate tests of Ophthalmidium sp. 3 have been recorded from the Pelsonian to Cordevolian interval of the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9).

Ophthalmidium sp. 4

Figure 14.25

Remarks

Ophthalmidium sp. 4, with a losangic outline, is also found in the Cordevolian of the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 9).

Ophthalmidium? sp. 5

Figure 14.24

Remarks

Ophthalmidium? sp. 5 (Fig. 14.24) is quite close to Eoophthalmidium of Langer (Reference Langer1968), with a cornuspirine tubular second chamber in early whorls and gradually shortened chambers in the adult similar to the illustrations given in Okay et al. (Reference Okay, Altıner and Kiliç2015; see also Zaninetti and Brönnimann, Reference Zaninetti and Brönnimann1969). This form occurs in the Bithynian of the Guandao section (Fig. 11).

Family Quinqueloculinidae Cushman, Reference Cushman1917

Genus Gsollbergella Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1979

Gsollbergella? sp. 1

Figure 14.26

Remarks

Questionable forms assigned to Gsollbergella? sp. 1 (Fig. 14.26) and G.? sp. 2 (Fig. 14.27), characterized by incipient divisions in the tubular chamber, have been recognized in the Fassanian (lower Ladinian) and Pelsonian to Illyrian (Anisian), respectively, of the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9). However, transverse sections of such forms are not known, and only a quinqueloculine-type coiling would enable confident assignment to the genus Gsollbergella.

Gsollbergella? sp. 2

Figure 14.27

Remarks

See Remarks under Gsollbergella? sp. 1.

Family Galeanellidae Zaninetti et al., Reference Zaninetti, Altıner, Dağer and Ducret1982

Genus Galeanella Kristan, Reference Kristan1958

Galeanella sp.

Figure 14.28

Remarks

A primitive form of the genus Galeanella, G. sp., characterized by a thick perforated wall and probably with a biloculine chamber arrangement, has been recorded in the Cordevolian (lower Carnian) strata of the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 9). According to Zaninetti, Martini, and Altıner (Reference Zaninetti, Martini and Altıner1992) and Zaninetti and Martini (Reference Zaninetti and Martini1993), the earliest representatives of the genus Galeanella appeared early in the Carnian. This unusual Galeanella has also been illustrated by He and Wang (Reference He and Wang1990) from the Carnian of south China. The Chinese specimen could be considered as one of the earliest Galeanella populations.

Class Textulariata Mikhalevich, Reference Mikhalevich1980

Remarks

In the Great Bank of Guizhou, Textulariata is quite diverse and composed of the bilocular family Ammodiscidae and several multilocular families, namely Trochamminidae, Reophacidae, Spiroplectamminidae, Placopsilinidae, Verneulinidae, Cuneolinidae, Piallinidae, and Textulariidae.

Family Ammodiscidae Reuss, Reference Reuss1862

Subfamily Glomospirellinae Ciarapica and Zaninetti, Reference Ciarapica and Zaninetti1985

Genus Gandinella Ciarapica and Zaninetti, Reference Ciarapica and Zaninetti1985

Gandinella? sp.

Figure 15.12

Figure 15. All specimens are from Dawen (PDW), Dajiang (PDJ), Middle Triassic Dajiang (MDJ), Guandao (PGD), and Upper Guandao (PUG) sections. (1–5) Glomospirella vulgaris Ho, Reference Ho1959; (6, 7) Glomospirella sp. 1; (8, 9) Glomospirella sp. 2 (Glomospirella lampangensis? Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini, Rettori, Zaninetti, Ratanasthien, Saegusa and Nakaya2006); (10, 11) Glomospira sp. (Pilammina praedensa? Urošević, Reference Urošević1988); (12) Gandinella? sp.; (13–20) Pilammina densa Pantić, Reference Pantić1965; (21–24) Pilammina densa? Pantić, Reference Pantić1965; (25–27) Pilamminella grandis Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967. (1, 2) PDJ-319; (3) PGD-131; (4) PDW-342; (5) PGD-096; (6, 19–22) PUG-029; (7) PUG-054; (8, 9) PGD-236; (10) PDJ-302; (11) PDJ-303; (12) MDJ-02; (13) PUG-063; (14) PUG-059; (15) PUG-054; (16) PUG-045; (17) PUG-037; (18) PGD-217; (23) PUG-015; (24) PUG-051; (25, 26) PUG-027; (27) PUG-033. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Remarks

In the subfamily Glomospirellinae, forms tending to display a sigmoidal coiling following a streptospiral early stage are reported as Gandinella? sp. Such forms have been discovered in the Pelsonian substage of the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Fig. 10).

Genus Glomospira Rzehak, Reference Rzehak1885

Glomospira sp.

Figure 15.10, 15.11

Remarks

Glomospira sp., recorded from the Smithian of the Dajiang section (Fig. 6), is characterized by small, entirely streptospiral tests, nearly identical to forms illustrated as G. regularis by Ho (Reference Ho1959). Rettori (Reference Rettori1995) placed such forms in synonymy under Pilammina praedensa Urošević, Reference Urošević1988.

Genus Glomospirella Plummer, Reference Plummer1945

Glomospirella vulgaris Ho, Reference Ho1959

Figure 15.1–15.5

Remarks

The genus Glomospirella is represented by three different populations. Among these, G. vulgaris consists of a deuteroloculus describing an initial streptospiral coiling with 3–5 whorls and then a planispiral coiling tending to become slightly sigmoidal in the adult. It has been recorded in the Smithian of the Dawen (Fig. 5), Dajiang (Fig. 6), and Guandao (Fig. 11) sections. In the recent literature, Glomospirella illustrated by Song et al. (Reference Song, Tong and Chen2011b) from the Olenekian of the Yangtze Block is probably G. vulgaris. In addition, most of the forms illustrated as Hoyenella spp. by Song et al. (Reference Song, Tong, Wignall, Luo, Tian, Song, Huang and Chu2016) in the facies photographs of the Olenekian of south China should also be referred to G. vulgaris. From the European side, G. vulgaris described from the Anisian of Poland and Slovakia by Rychliński et al. (Reference Rychliński, Ivanova, Zaglarz and Bucur2013) should be referred either to Gandinella or Glomospirella.

Glomospirella sp. 1

Figure 15.6, 15.7

Remarks

Glomospirella sp. 1, recorded from the uppermost Bithynian to Longobardian interval of the Upper Guandao section (Figs. 8, 9), is characterized by a tightly coiled deuteroloculus with a smaller chamber height, similar to the morphology of Glomospira tenuifistula described by Ho (Reference Ho1959). However, this form has a Glomospirella-like planispiral stage and more compressed axial sections.

Glomospirella sp. 2

Figure 15.8, 15.9

Remarks

The other Glomospirella population, G. sp. 2, is also distinct, with its pronounced streptospiral stage occupying more than half of the volume of the test and tightly coiled, oscillating to planispiral two or three whorls. Glomospirella sp. 2 is morphologically very close to Glomospirella lampangensis Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini, Rettori, Zaninetti, Ratanasthien, Saegusa and Nakaya2006, which was described from northern Thailand. However, more material is required in order to decide on the degree of similarity in coiling between our G. sp. 2 and G. lampangensis. This form appears in the Aegean close to the Olenekian-Anisian boundary in the Guandao section and ranges into the Bithynian (Fig. 11).

Subfamily Pilammininae Martini, Vachard, and Zaninetti, Reference Martini, Vachard and Zaninetti1995

Genus Pilammina Pantić, Reference Pantić1965

Pilammina densa Pantić, Reference Pantić1965

Figure 15.13–15.20

Remarks

In the ammodiscid foraminiferal fauna, the main biostratigraphic markers in the Triassic stratigraphy belong to genera such as Pilammina and Pilamminella. Pilammina densa Pantić, Reference Pantić1965 has been reported from the Anisian by many authors (e.g., Baud et al., Reference Baud, Zaninetti and Brönnimann1971; Premoli Silva, Reference Premoli Silva1971; Brönnimann et al., Reference Brönnimann, Cadet and Zaninetti1973a, Reference Brönnimann, Cadet and Zaninettib; Gazdzicki et al., Reference Gazdzicki, Trammer and Zwidzka1975; Zaninetti, Reference Zaninetti1976; Dağer, Reference Dağer1978a; Trifonova, Reference Trifonova1978a; Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Borza and Samuel1983; He, Reference He1984; He and Wang, Reference He and Wang1990; Altıner and Koçyiğit, Reference Altıner and Koçyiğit1993; Rettori, Reference Rettori1995; Bucur et al., Reference Bucur, Strutinski and Paica1997; de Bono et al., Reference de Bono, Martini, Zaninetti, Hirsch, Stampfli and Vavassis2001; Fugagnoli and Posenato, Reference Fugagnoli and Posenato2004; Berra et al., Reference Berra, Rettori and Bassi2005; Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Martini and Zaninetti2005, Reference Kobayashi, Martini, Rettori, Zaninetti, Ratanasthien, Saegusa and Nakaya2006; Marquez, Reference Marquez2005; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Summers, Rego, Altıner, Wei, Yu and Lehrmann2011; Velledits et al., Reference Velledits, Péró, Blau, Senowbari-Daryan, Kovács, Piros, Pocsai, Szúgyi-Simon, Dumitrica and Palfy2011; Song et al., Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015; Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015; Miyahigashi et al., Reference Miyahigashi, Hara, Hisada, Nakano, Charoentitirat, Charusiri, Khamphoveng, Martini and Ueno2017). It is mainly characterized by numerous streptospirally and tightly coiled whorls with planes of coiling changing slowly (Fig. 15.13–15.20).

In the Guandao and Upper Guandao sections (Figs. 8, 11), P. densa ranges from the Bithynian to the Pelsonian, as calibrated with conodonts (Lehrmann et al., Reference Lehrmann, Stepchinski, Altıner, Orchard, Montgomery, Enos, Ellwood, Bowring, Ramezani, Wang, Wei, Yu, Griffiths, Minzoni, Schall, Li, Meyer and Payne2015). It has been recorded in the Pelsonian of the Middle Triassic Dajiang section (Fig. 10). The first appearance of P. densa nearly coincides with the Aegean/Bithynian boundary, consistent with reporting by Song et al. (Reference Song, Wang, Tong, Chen, Tian, Song and Chu2015). Although the P. densa Zone has been assigned to the late Anisian in western Tethyan domains (See Rettori, Reference Martini, Rettori, Urošević and Zaninetti1995 and the references therein), this form has never been recorded from the upper Anisian (Illyrian) in the Chinese sections.

Pilammina densa? Pantić, Reference Pantić1965

Figure 15.21–15.24

Remarks

Smaller forms with numerous whorls describing partly a sigmoidal coiling (Fig. 15.21, 15.22) and displaying a quadrangular profile (Fig. 15.23, 15.24) have been questionably assigned to P. densa. Similar forms were reported by Flügel et al. (Reference Flügel, Ramovš and Bucur1994) as Glomospira? sp. cf. G.? micas He and Yue, Reference He and Yue1987 from the Pelsonian of Slovenia. Pilammina densa? of this study is also close to some specimens illustrated as P. densa from the Anisian of Malaysia by Gazdzicki and Smit (Reference Gazdzicki and Smit1977) and Greece by Rettori et al. (Reference Rettori, Angiolini and Muttoni1994).

Genus Pilamminella Salaj, Reference Salaj1978

Pilamminella grandis Salaj in Salaj et al., Reference Salaj, Biely and Bistricky1967

Figure 15.25–15.27

Remarks

The genus Pilamminella is represented by P. grandis in the Chinese material. This form is characterized by tests consisting of oscillating to planispiral whorls in the adult following a tightly coiled Pilammina-like stage. Rettori (Reference Rettori1995) considered this form as a synonym of P. semiplana; however, P. grandis differs from this form in the absence of sigmoidal coiling in the initial stage and rather less tightly coiled whorls in the planispiral stage. Some sections of foraminifera illustrated as Glomospira densa or Glomospira sp. by Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1996) from the Anisian of the Kanto Mountains, Japan, belong to P. grandis. Similarly, P. grandis has been reported from Japan as Glomospirella irregularis in Kobayashi et al. (Reference Kobayashi, Martini and Zaninetti2005). Bucur et al. (Reference Bucur, Strutinski and Paica1997) extensively illustrated P. grandis from the Anisian of the southern Carpathians in Romania. In relatively recent literature, P. grandis has been reported as P. semiplana, following Rettori (Reference Rettori1995), from the Anisian of northern Italy by Fugagnoli and Posenato (Reference Fugagnoli and Posenato2004) and Berra et al. (Reference Berra, Rettori and Bassi2005). Pilamminella grandis ranges from Aegean to Pelsonian in the Upper Guandao section (Fig. 8) and Aegean to Bithynian in the Guandao section (Fig. 11).

Subfamily Tolypammininae Cushman, Reference Cushman1928

Genus Tolypammina Rhumbler, Reference Rhumbler1895

Tolypammina gregaria Wendt, Reference Wendt1969

Figure 16.1