Introduction

Organisms living in the water column without the capacity to actively swim against the current are generally referred to as plankton. Arthropods are the most diverse group in the plankton, representing 50–70% of the total species diversity, however, despite their abundance in Recent ecosystems, planktonic arthropod species are very rare in the fossil record (Perrier et al., Reference Perrier, Williams and Siveter2015). Crustaceans are by far the most abundant arthropod group in the plankton, but as in arthropods in general, the fossil record of crustaceans is very sparse and is restricted to a few groups (see Haug and Haug, Reference Haug and Haug2017). Postmortem transport and morphological adaptations, such as the reduction of skeletal material, can be responsible for the reduced fossilization potential of these groups (Rigby and Milsom, Reference Rigby and Milsom2000).

The Araripe sedimentary basin in the northern region of Brazil has an exceptionally well-preserved fossil record of several groups, including insects, plants, fishes, and several tetrapod groups (e.g., Maisey, Reference Maisey1991; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Saraiva and Sayão2012; Bantim et al., Reference Bantim, Barros, Silva, Lima, Sayão and Saraiva2015; Oliveira and Kellner, Reference Oliveira and Kellner2017). Ongoing studies have revealed an increasing number of crustacean species—mostly shrimps—in this basin (Martins-Neto and Mezzalira, Reference Martins-Neto and Mezzalira1991; Maisey and Carvalho, Reference Maisey and Carvalho1995; Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Pralon and Gregati2009; Santana et al., Reference Santana, Pinheiro, da Silva and Saraiva2013; Pinheiro et al., Reference Pinheiro, Saraiva and Santana2014). Until now, two malacostracan planktonic species have been found in this basin: a zoea (Maisey and Carvalho, Reference Maisey and Carvalho1995) and the sergestid Paleomattea deliciosa Maisey and Carvalho, Reference Maisey and Carvalho1995 (Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Pralon and Gregati2009; Luque, Reference Luque2015).

Luciferidae is an extant family of planktonic shrimps with unusual morphology, such as reduced appendages and branchia, a compressed body, and a unique copulatory organ (Vereshchaka et al., Reference Vereshchaka, Olesen and Lunina2016). Luciferids are pelagic and commonly found in coastal areas, where they are an important component of the diet for several groups, including fishes (e.g., Sedberry and Cuellar, Reference Sedberry and Cuellar1993; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Haimovici and Palacios2005) and whale sharks (e.g., Rohner et al., Reference Rohner, Armstrong, Pierce, Prebble, Cagua, Cochran, Berumen. and Richardson2015). Until recently, this family was considered monotypic with Lucifer Thompson, Reference Thompson1829 as the only genus. However, a revision included the new genus Belzebub Vereshchaka, Olesen, and Lunina, Reference Vereshchaka, Olesen and Lunina2016 in the family (Vereshchaka et al., Reference Vereshchaka, Olesen and Lunina2016). Here, we describe and illustrate a new genus and species of Luciferidae, namely Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp., from the Araripe Basin, a remarkable first fossil species of the family.

Geological setting

The Araripe Basin is located in the northeast region of Brazil and includes areas of three different states of the Brazilian Federation: southwestern Ceará, northwestern Pernambuco, and eastern Piauí. It is an area of ~12,000 km2 and is the largest intratectonic basin in Brazil. Under the Chapada do Araripe, we found a stratigraphic sequence of ~1,000 m with pre-rift, sin-rift, and post-rift phases, including nine geological formations. These deposits are Devonian, Jurassic, and Cretaceous (Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Hessel, Guerra and Fara2007). Among the Cretaceous deposits, the Santana Group is a depositional sequence associated with the South Atlantic opening. This sequence comprises the Barbalha, Crato, Ipubi, and Romualdo formations (Assine et al., Reference Assine, Perinotto, Andriolli, Neumann, Mescolotti and Varejão2014). The Barbalha, Crato, and Ipubi formations are commonly associated with freshwater sediments, and the Romualdo Formation has the characteristics of a lagoon with fossil echinoids (Manso and Hessel, Reference Manso and Hessel2012). The Romualdo Formation is composed of layers of dark shale at the base that alternate with layers of fine-grained, poorly consolidated sandstone. Near the top of the formation, we found marl intervals with ichthyoliths and carbonate concretions preserving three-dimensional fossils and common fishes, as well as fossil imprints among the blade-like shale fragments and marls (Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Hessel, Guerra and Fara2007). Above the gypsum pack of the Ipubi Formation is an erosional disconformity, which is considered the boundary between Ipubi and Romualdo formations (Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Borrego, Cabrera and Dino2003). A sequence of shale with fossil impressions, mainly shrimps and some fishes, begins just above this disconformity. Unlike the three-dimensional shrimp fossils found in carbonate concretions, which do not preserve the ends of the body, impressions occurring in the shale are generally complete. The shrimp impressions in this level can be found throughout the southern part of the Araripe Basin in a layer ~80 cm thick. About 30 m above this facies, the shrimps Paleomattea deliciosa, Kellnerius jamacaruensis Santana et al., Reference Santana, Pinheiro, da Silva and Saraiva2013, and Araripenaeus timidus Pinheiro, Saraiva, and Santana, Reference Pinheiro, Saraiva and Santana2014, and the crab Araripecarcinus ferreirai Martins-Neto, Reference Martins-Neto1987, have been found. At the same level, the fossil imprint of Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. was found in calcareous shales with several specimens of Araripenaeus timidus and Paleomattea deliciosa in carbonate concretions of the Romualdo Formation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Stratigraphic profile and scheme of the Romualdo Formation (Cretaceous—Aptian/Albian) where the specimens were collected. Vertical exposure=32 m.

Materials and methods

The material studied here was collected in a mining site (Mineradora Serra Suposta), municipality of Trindade, Pernambuco State, 07°43'37.4''S, 040°32'26.8''W (Fig. 2). Descriptions, drawings, and photographs were made using a stereomicroscope Nikon SMZ 745T equipped with camera lucida and a Leica EZ4 W, both with digital camera attached. The software ISCapture 3.6.1 was used to take the measurements, all in millimeters (mm). The specimen of Belzebub faxoni (Borradaile, Reference Borradaile1915) used in the comparisons was stained with rose Bengal (Fig. 3).

Figure 2 Geographic position of the sampling site Trindade in the Araripe Basin, northeast Brazil. Colors indicate the different sequences of the Araripe Basin.

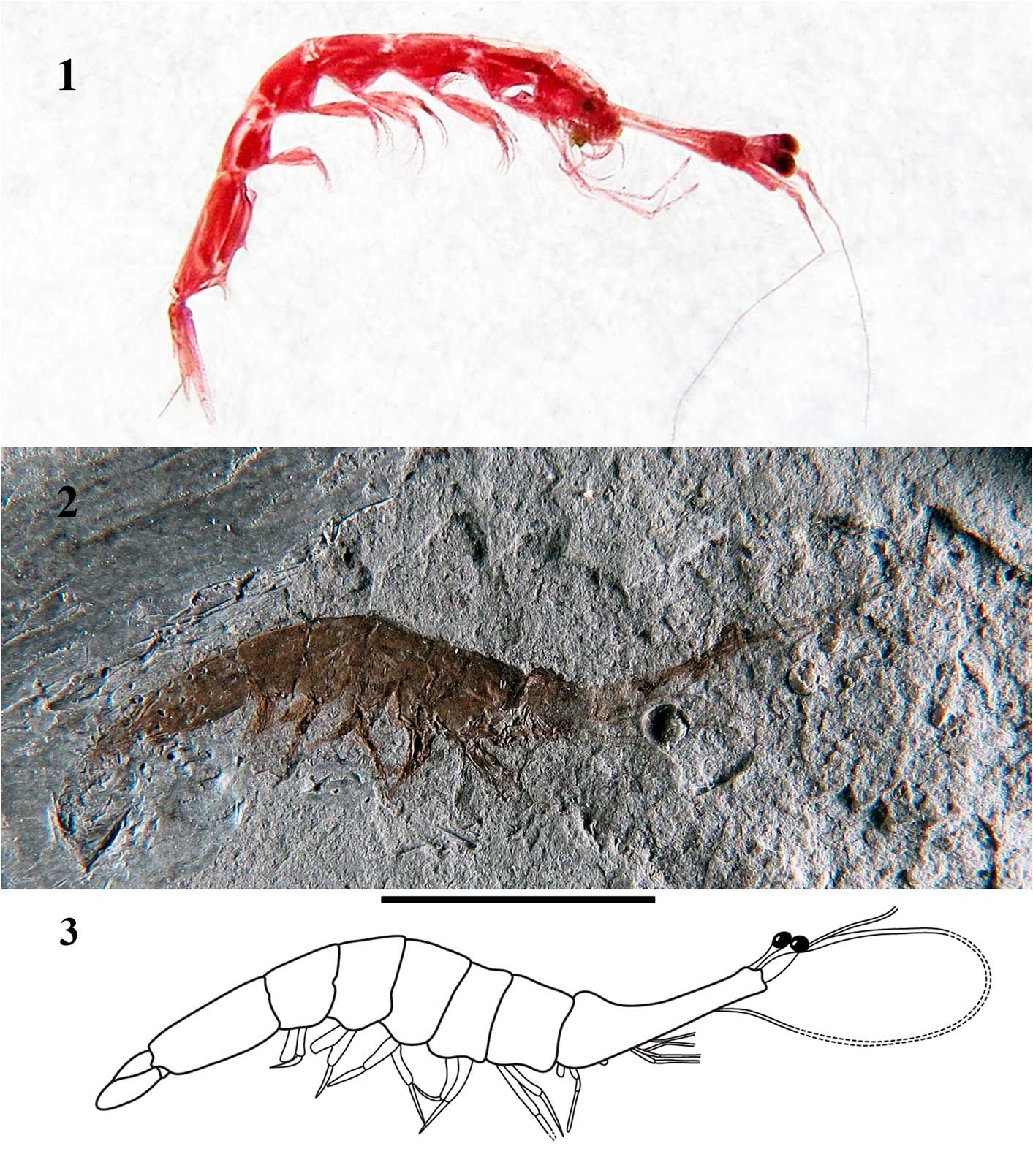

Figure 3 (1) Belzebub faxoni (Borradaile, Reference Borradaile1915) lateral view. (2, 3) Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. (LPU 1250A) from the Romualdo Formation, Cretaceous (Aptian/Albian), Araripe Basin: (2) lateral view of the holotype; (3) line drawing of the holotype. Dotted lines represent appendages not preserved. Scale bar: 5 mm. Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. dry, uncoated. Photos by: (1) A.P. Pinheiro, (2) W. Santana. Line drawing by W. Santana.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

The holotype material studied, described, and illustrated here is deposited in the Laboratório de Paleontologia da Universidade Regional do Cariri (LPU).

Systematic paleontology

Order Decapoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Suborder Dendrobranchiata Bate, Reference Bate1888

Superfamily Sergestoidea Dana, Reference Dana1852

Family Luciferidae De Haan, Reference De Haan1849

Genus Sume new genus

Type species

Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp.

Diagnosis.—

Eyestalks of moderate length, not reaching the end of scaphocerite; pleonal pleura overlapping protopods of pleopods, forming a rounded projection medially on somites two to four.

Etymology.—

Sumé, from the Tupi mythology, is a god that disappeared in the Atlantic Ocean. Gender masculine.

Remarks

Sume n. gen. presents several diagnostic characters of Luciferidae, including a carapace laterally compressed and anteriorly elongate, with the buccal frame widely separated from antennae and eyes; reduced thoracic appendages; and fourth and fifth pereopods absent. Among the Luciferidae, Sume n. gen. resembles Belzebub in its moderately long eyestalks that do not reach the end of the scaphocerites, while Lucifer has elongated eyestalks. Sume n. gen. can be differentiated from Belzebub based on the pleonal pleura overlapping the protopods of the pleopods, forming a rounded projection medially on somites two to four (pleonal pleura do not overlap the protopods of the pleopods, nor do they form a rounded projection medially on somites two to four in Belzebub).

Sume marcosi new species

Figure 4 Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. (LPU 1250A) from the Romualdo Formation, Cretaceous (Albian), Araripe Basin: (1) detail of the anterior region of the carapace showing the antennal flagelum; (2) detail of the carapace including eyes and maxillipeds (black arrow indicates the constriction near the buccal field); (3) detail of somites 1 to 4 of the pleon and pleopods; (4) detail of somites five and six of the pleon, pleopods of the fifth somite, telson and uropods. Scale bars: 1 mm. Specimen dry, uncoated. Photos by C. Schweitzer.

Holotype

LPU 1250A and 1250B.

Diagnosis.—

Same as for the genus.

Occurrence.—

The fossil studied here was collected in the Romualdo Formation, Santana Group, Araripe Basin in the town of Trindade, Pernambuco State. The age is Early Cretaceous (Aptian/Albian).

Description.—

Fossil preserved in lateral view. Total length from anterior margin of carapace to the posterior margin of telson 12.20 mm; carapace from anterior to posterior margins 3.56 mm; abdomen 8.64 mm from anterior margin of the first somite to posterior margin of the sixth somite. Carapace length ~3.5 times longer than its maximum height, with a constriction near the buccal field, tapering distally, laterally compressed, with ventral and dorsal margins smooth; posterior margin rounded ventrally. Rostrum not discernible. Antenna and antennule protopodites incompletely preserved, indiscernible, apparently without ornamentation, adjacent to ocular peduncle; with long incompletely preserved flagellum. Eye stalks and eyes apparent, cornea distinct. Second and third maxillipeds discernible, incompletely preserved, segmentation not perceptible, except for the right third maxilliped with one distinguishable segment. Pereiopods almost not preserved, except for one-third pereiopod with protopodite and two segments, very slender, other third and one second pereiopod with protopodite preserved, without ornamentation.Pleon with six somites, apparently without ornamentation; pleura overlapping protopods of pleopods, forming a rounded projection medially on somites two to four. First pleonal somite 1.3 times higher than long. Second pleonal somite 1.9 times higher than long. Third pleonal somite length ½ of its maximum height. Fourth pleonal somite length ⅓ of its maximum height. Fifth pleonal somite as long as its maximum height. Sixth pleonal somite elongated, 2.5 times longer than its maximum height, smooth in ventral margin, without ventral processes.Telson small, without visible ornamentation, with acute distal end. Pleopods well developed, well preserved, first pair longer, slightly decreasing in size to the fifth pair, with long protopodite; exopod or endopod preserved in at least one pleopod of each segment, without visible segmentation and ornamentarion. Petasma not discernible. Uropods incompletely preserved, endo and exopod indiscernible, apparently without ornamentation.

Etymology

This new species is named in honor of the great carcinologist and friend, Marcos Tavares, in recognition of his work and efforts to develop Brazilian carcinology.

Remarks

The family Luciferidae shows a reduction or loss of several morphological characters. Although the fossil presented here is very well preserved and is easily recognizable as a member of this family (see remarks section of the genus), characters that differentiate Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. from its congeners are not so readily recognizable. This is mostly due to the sparse preservation of appendages essential for identification (e.g., maxillipeds, antenna, and antennule) and the sexual dimorphism characteristic of the group, where males present several characteristics with taxonomic importance (e.g., petasma and ventral processes in the sixth pleonal somite). The petasma of the Luciferidae is one of the few well-sclerotized body parts, which suggests the holotype is probably a female, specifically due to the lack of petasma in the specimen studied here.

Sume marcosi n. gen. n. sp. is the first fossil Luciferidae known and one of the very few other Cretaceous Sergestoidea (e.g., Paleomatea deliciosa Maisey and Carvallho, 1995; Cretasergestes sahelalmaensis Garassino and Schweigert, Reference Garassino and Schweigert2006; and Mokaya changoensis Garassino et al., Reference Garassino, Vega, Calvillo-Canadell, Cevallos-Ferriz and Coutiño2013). According to Vereshchaka et al. (Reference Vereshchaka, Olesen and Lunina2016), the extant species of Lucifer are more oceanic, and Belzebub species are found mostly in the neritic zone. In this ecological context, it is surprising that a typically planktonic group could be so well fossilized. The resemblance between Sume n. gen. and Belzebub could be not only morphological but also ecological. The Romualdo Formation has lagoonal/coastal characteristics with repeated events of marine incursions (Saraiva et al., Reference Saraiva, Hessel, Guerra and Fara2007).

The Araripe sedimentary basin is one of the world’s most famous Cretaceous deposits with some of its strata (Santana Group) considered to be a fossil Lagerstätte (Nudds and Selden, Reference Nudds and Selden2008) due to the remarkable preservation of its fossils. The region, as pointed out by Martill (Reference Martill1989, p. 205), is “possibly the finest fossil locality in the world.” This unique confluence of soft-tissue preservation of small, delicate planktonic organisms allows researchers the unique opportunity to study the palaeoplanktonic Cretaceous fauna, as well as some key fossil species from groups not known until now.

Acknowledgments

We thank FUNCAP (Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e tecnológico), CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) and FAPESP (São Paulo Research Foundation), grant number 2013/01201-0, for financial support. We also thank R.C. da Costa (São Paulo State University, UNESP) for his help during specimen comparisons, and C. Schweitzer and R. Feldmann (Kent State University) for the help during figure preparations, discussions, and critical reading of the manuscript. Thanks to G. Oliveria (Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco) for the help during the field work and to D. Ribeiro (URCA) for the specimens preparation. This manuscript greatly benefitted from comments of the reviewer J. Luque (University of Alberta) and the Associate Editor T. Hegna (Western Illinois University).