Introduction

Extinct Hydrochoerinae (Caviidae, Cavioidea; sensu Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez, Reference Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez2017) known as ‘cardiomyines’ encompass medium-sized caviomorph rodents, mainly characterized by ever-growing teeth, p4 composed of three prisms, P4–M2 and m1–m3 formed by two heart-shaped prisms with accessory flexi/ids, M3 multiprismatic, and a broad palate (Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vucetich and Deschamps2014). They are first known from the middle Miocene of Patagonia (Vucetich and Pérez, Reference Vucetich and Pérez2011), reaching their greatest taxonomic diversity during the late Miocene–late Pliocene of Argentina (Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914; Kraglievich, 1927, Reference Kraglievich1940; Pascual, Reference Pascual1961; Pascual and Bondesio, Reference Pascual and Bondesio1963; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Ortega Hinojosa, Gondar and Tonni1966; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011), with additional reports from the Neogene of Bolivia (Anaya and MacFadden, Reference Anaya and MacFadden1995), Venezuela (Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Carlini, Aguilera and Sánchez-Villagra2010), and Brazil (Kerber et al., Reference Kerber, Negri, Ribeiro, Nasif, Souza-Filho and Ferigolo2017). Late Miocene and Pliocene ‘cardiomyines’ are represented by several species included in the genera Cardiomys, Caviodon Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1885 (including Lelongia Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1930b), Procardiomys Pascual, Reference Pascual1961, and Xenocardia Pascual and Bondesio, Reference Pascual and Bondesio1963, all of which are known from abundant cranial and dental remains. Traditionally, these genera were included within the subfamily Cardiomyinae of Caviidae (Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914; Pascual, Reference Pascual1961; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Ortega Hinojosa, Gondar and Tonni1966; Mones, Reference Mones1986; McKenna and Bell, Reference McKenna and Bell1997). Later, the cardiomyines were considered Hydrochoeridae (e.g., Vucetich and Pérez, Reference Vucetich and Pérez2011; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011). More recently, cladistic analyses (Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez, Reference Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez2017; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vallejo-Pareja, Carrillo and Jaramillo2017b) recovered Caviodon, Cardiomys, Xenocardia, and Procardiomys as basal Hydrochoerinae within the family Caviidae, but the monophyly of ‘Cardiomyinae’ (as originally defined) was not recognized. The postcranial anatomy of ‘cardiomyines’ is poorly known and their paleobiology was scarcely scrutinized. Only a few fragmentary postcranial bones of Caviodon cuyano Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011 (Pliocene of Mendoza Province) have been described (Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011). Moreover, the postcranium of these rodents was not used as source of characters either in systematic analyses or to infer probable locomotor behavior.

In this contribution, we present the first description of postcranial remains of Cardiomys. The specimen studied comes from the Chasicó Formation (late Miocene, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina) and represents the ‘cardiomyine’ with the most completely preserved postcranium known. We evaluate it from a paleobiological point of view and discus the systematic implications of its postcranial features.

Materials and methods

The new specimen of Cardiomys (MLP 29-IX-3-19) described here is represented by an isolated right M3 and associated postcranial remains. Molar morphology of this specimen was compared with specimens of Caviodon, Cardiomys, Xenocardia, and Procardiomys by direct observation or by comparison with published data (Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1885; Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914; Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1930b; Pascual, Reference Pascual1961; Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Ortega Hinojosa, Gondar and Tonni1966; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011; Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vucetich and Deschamps2014). The postcranial elements of specimen MLP 29-IX-3-19 were compared with the postcranium of the type specimen of Caviodon cuyano from the Aisol Formation (Pliocene, Mendoza Province), based on descriptions and illustrations provided by Vucetich et al. (Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011). We also compared the postcranial remains with extant species of all main lineages of Cavioidea (Supplemental Data 1). Dental nomenclature follows that of Pérez et al. (Reference Pérez, Vucetich and Deschamps2014). The osteological nomenclature follows that used by Candela and Picasso (Reference Candela and Picasso2008) and the International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature (2005). Most of the postcranial characters of cavioids used in the comparisons have been previously discussed by Candela and Picasso (Reference Candela and Picasso2008) and García-Esponda and Candela (Reference García-Esponda and Candela2016). The myological nomenclature and muscular system are based on Woods (Reference Woods1972) and García-Esponda and Candela (Reference García-Esponda and Candela2010). Locomotor habits and substrate preferences of present-day species follow Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Muñoz and García-Esponda2017).

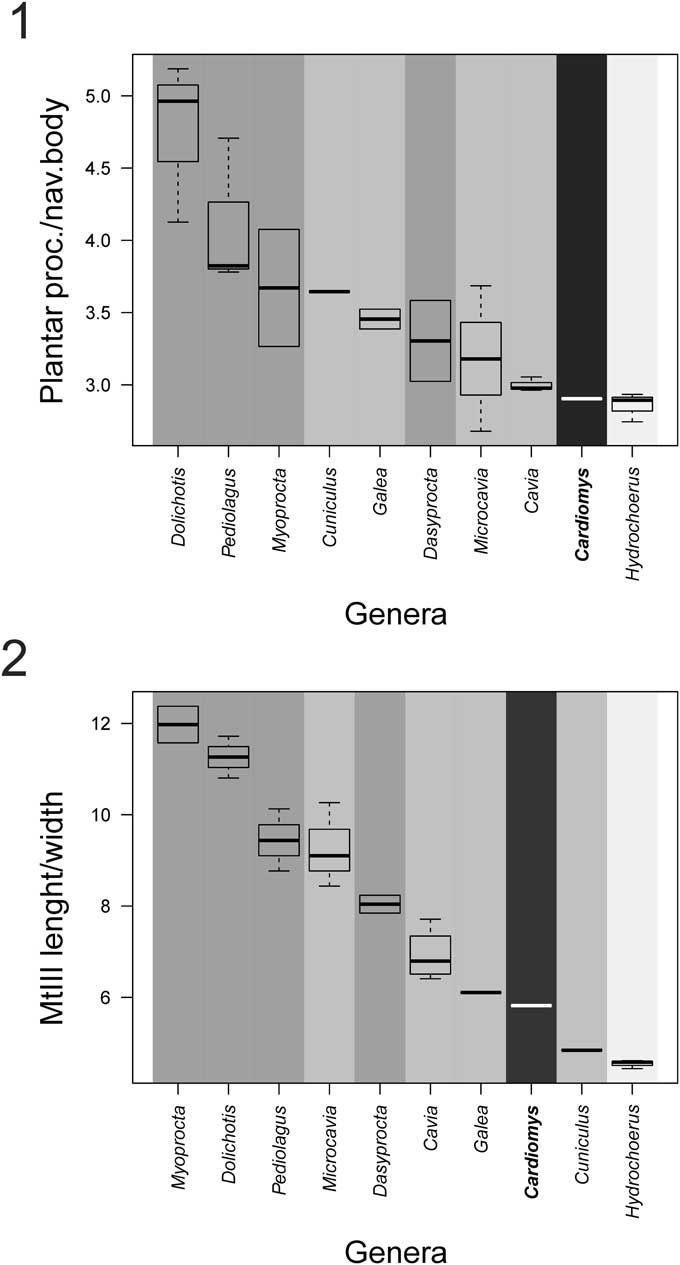

Four linear measurements were taken from photographs of the studied material using ImageJ 1.50i software (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012). The variables measured were navicular body length, plantar process of the navicular length, third metatarsal (Mt III) length, and Mt III width. Two indices were calculated: (1) plantar process of the navicular length/navicular body length, and (2) Mt III length/width. Each box plot was created in R software 3.1.5 (R Development Core Team, 2015).

Part of the morphological variation observed among cavioids was coded in six characters. Only those characters considered informative in the context of our taxon sample were included in the character mapping. Character state definitions are provided in Supplemental Data 2, and the resultant data matrix is provided as a TNT script in Supplemental Data 3. The evolution of these characters was mapped on the composite molecular-morphological phylogeny of Cavioidea provided by Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez (Reference Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez2017), which was simplified to living taxa and the extinct Cardiomys. Cladistic mapping was done with TNT 1.5 (Goloboff and Catalano, Reference Goloboff and Catalano2016). Four discrete character states were considered unordered whereas the remaining two characters were coded as continuous (Goloboff et al., Reference Goloboff, Mattoni and Quinteros2006), using the mean value for each terminal taxa.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The studied specimens are housed in the following collections: Museo de La Plata (MLP), La Plata, Argentina; Museo de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’ (MACN), Buenos, Aires, Argentina; zoological collection of Museo de Ciencias Naturales ‘P. Antonio Scasso’ (MPS-Z), San Nicolás, Argentina; Centro Nacional Patagónico (CNP), Puerto Madryn, Argentina; mammal collection of Museo Municipal de Ciencias Naturales ‘Lorenzo Scaglia’ (MMPMa), Mar del Plata, Argentina; American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), New York, New York, USA; Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (YPM), New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Order Rodentia Bowditch, Reference Bowditch1821

Suborder Hystricomorpha Brandt, Reference Brandt1855

Superfamily Cavioidea (Fischer von Waldheim, Reference Fischer von Waldheim1817) Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1930a

Family Caviidae Fischer von Waldheim, Reference Fischer von Waldheim1817

Subfamily Hydrochoerinae (Gray, Reference Gray1825) Gill, Reference Gill1872; Weber, Reference Weber1928 sensu Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1930a

Genus Cardiomys Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1885

Type species

Cardiomys cavinus Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1885, ‘Mesopotamiense’ (lower member of Ituzaingó Formation, late Miocene), Entre Ríos Province, northeast Argentina.

Cardiomys leufuensis Pérez, Deschamps, and Vucetich, 2017

Occurrence

Chasicó Locality, southwest Buenos Aires Province (Argentina); Arroyo Chasicó Formation, Chasicoan Stage/Age, late Miocene (see Tonni et al., Reference Tonni, Scillato-Yané, Cione and Carlini1998; Cione and Tonni, Reference Cione and Tonni2005; Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Schultz, Blasi, Heil, King and Hames2007).

Description

The M3 has four prisms separated by deep lingual flexi (Fig. 1). The first prism is the most anteroposteriorly compressed of all prisms; it displays a convex anterior border and a labial superficial flexus (sulcus). The second and third prisms are heart-shaped. The second prism has two labial flexi, somewhat deeper than that of the first prism. The third prism is anteroposteriorly wider than the second and displays a labial superficial sulcus on its anterior labial border. The fourth prism is labiolingually narrower than the other prisms and shows a posterior prolongation. Enamel is thicker on the lingual border of the prisms than on the labial side. This tooth would correspond to an adult individual because the diameters of its base and occlusal surfaces are approximately equal (Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011).

Figure 1 MLP 29-IX-3-19, right upper third molar of Cardiomys leufuensis in occlusal view. Scale bar=2 mm.

In general appearance, the distal portion of the humerus (Fig. 2.2) is similar to that of other cavioids. The olecranon fossa is perforated. The entepicondyle is moderately developed, showing an expansion similar to that of Hydrochoerus (Fig. 2.1) and Dasyprocta Illiger, Reference Illiger1811, but relatively larger than in caviines and dolichotines (Fig. 2.3) and smaller than that of Cuniculus Brisson, Reference Brisson1762. The distal articular surface of the humerus is relatively higher proximodistally than that of Cuniculus, similar to that of Hydrochoerus, and lower than that of Caviinae, Dolichotinae, and Dasyprocta. The capitular tail has a degree of differentiation similar to that of Hydrochoerus; compared to other cavioids, it is more lateromedially extended and differentiated from the capitulum. The trochlea is steeply angled. The lateral lip of the trochlea is well developed on the caudal facet of the articular surface, but cranially it ends abruptly.

Figure 2 (1–3) Cranial view of right humeri. (4–6) Proximal and cranial views of right radii. (7–9) Cranial and lateral views of left ulnae. (1, 4, 7) Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris (MPS-Z 142); (2, 5, 8) Cardiomys leufuensis (MLP 29-IX-3-19); (3, 6, 9) Dolichotis patagonum (MLP 249). Views 1, 3, and 4 are mirrored. c=capitulum; ce=capitular eminence; ct=capitular tail; ctf=capitular tail facet; en=entepicondyle; f=fovea; lcp=lateral coronoid process; mcp=medial coronoid process; o=olecranon; rn=radial notch; t=trochlea; tf=trochlear facet; tn=trochlear notch. Scale bars=10 mm.

As in other cavioids, the proximal extremity of the radius (Fig. 2.5) articulates cranially with respect to the ulna. The proximal articular surface of the radius is subquadrangular, being wide lateromedially and short craniocaudally. Among cavioids, this configuration is also seen in Cuniculus, Caviinae, and Hydrochoerus (Fig. 2.4), whereas in Dolichotinae (Fig. 2.6) and Dasyprocta, this articular surface is less lateromedially extended. The proximal articular surface has three distinct facets: a central facet, the fovea; a medial facet, the trochlear facet; and a lateral facet, the capitular tail facet. The fovea is the main facet of the radial head, articulating with the capitulum of the humerus. It has a somewhat triangular outline, resembling that of Hydrochoerus. The trochlear facet has a steep inclination from lateral to medial, showing a similar development to that of Caviinae and Dolichotinae but greater than that of Cuniculus and Dasyprocta. The fovea and the trochlear facet are separated by a crest, which ends in a spine, the capitular eminence, on the cranial border of the head of the radius. The capitular tail facet lies on the lateral side of the radial head, articulating with the capitular tail of the humerus when the elbow is flexed. This facet has an inclination from medial to lateral and is separated from the fovea by a crest. As in Hydrochoerus, the capitular tail facet is well differentiated from the fovea and to a greater degree than in caviines (in Dolichotinae, this facet is not differentiated from the fovea). In addition, the most lateral portion of the radial head is craniocaudally shorter with respect to the rest of the articular surface. This narrowing is similar to, although not as pronounced as, that of Hydrochoerus but greater than that of Caviinae. Although the ulnar facet is poorly preserved, it is relatively flat.

The ulna (Fig. 2.8) is not completely preserved, but it can be noticed that the olecranon process is as long as the trochlear notch, a condition also observed in other cavioids (with the exception of Dasyprocta, in which the olecranon process is relatively shorter). The medial coronoid process is well differentiated, but the lateral coronoid process is very reduced (Fig. 2.8). The latter condition is close to that of Hydrochoerus and Cuniculus, in which this process is absent, and differs from that of caviines, dolichotines (Fig. 2.9), and Dasyprocta, all of which have a well-developed lateral coronoid process. The radial notch is wide, as in other cavioids, reflecting a broad anterior contact with the radius. As in Cuniculus and Dasyprocta, this notch is represented by a single facet. On the contrary, in Hydrochoerus, dolichotines, and caviines, the radial notch is composed of two separated facets for articulation with the radius. As in most Cavioidea, the caudal border of the proximal portion of the ulna is straight. This contrasts with the condition observed in Hydrochoerus, in which the caudal border is more concave, as a consequence of its caudally oriented olecranon. As observed in most cavioids, the lateral surface of the ulnar shaft has a shallow fossa (area of origin of the m. abductor pollicis longus), which extends proximally to the level of the radial notch.

Bones of the left manus are only represented by the pisiform (which is similar in shape to that of the other cavioids) and a fragmentary proximal end of the fourth metacarpal.

Only a small portion of the left ischium is preserved. This portion comprises the cranial part of the body of the ischium, including part of the acetabulum. It also includes the cranial portion of the lesser sciatic notch. The ischiadic spine and the pulley where the tendon of m. obturator internus slides are similar to those of Hydrochoerus.

Only the distal portion of the right fibula is preserved. The articular facet for the tibia and astragalus, and the sulci for the mm. peronei are similar to those of Hydrochoerus.

The ectal facet of the calcaneus (Fig. 3.2) is somewhat obliquely oriented with respect to the longitudinal axis of the bone, facing distally. The sustentaculum bears a subcircular and flat facet that is obliquely oriented and faces dorsodistally. The tuber calcanei is not preserved. The peroneal tubercle is short and indistinct, as in other cavioids. The cuboid facet is concave in dorsoventral direction, facing medially, similar to that of Hydrochoerus. As in other cavioids, this facet is far distally located with respect to the sustentaculum.

Figure 3 Right feet in (1–3) dorsal and (4–6) plantar views. (1, 4) Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris (MPS-Z 142); (2, 5) Cardiomys leufuensis (MLP 29-IX-3-19); (3, 6) Dolichotis patagonum (MLP 249). a=astragalus; c=calcaneus; cu=cuboid; ec=ectocuneiform; me=mesocuneiform; Mt II–IV=second to fourth metatarsals; n=navicular; ppc=plantar process of the cuboid; ppn=plantar process of the navicular. Scale bars=10 mm.

The navicular is poorly preserved, represented by two portions: a part of the navicular body (Fig. 3.2) and the plantar process (Fig. 3.5). The facet for the astragalar head is less lateromedially extended than in Hydrochoerus (Fig. 3.1), similar to that of Dolichotis Desmarest, Reference Desmarest1820 (Fig. 3.3). The preserved portion of the body is relatively proximodistally longer than that of Hydrochoerus. The plantar process is similar to that of Hydrochoerus, being wider and relatively shorter than that of caviines, dolichotines, and Dasyprocta (Figs. 3.4, 3.6, 4.1).

Figure 4 Box plots of morphological indices of the pes in cavioid rodents. (1) Plantar process of the navicular length/navicular body length index; (2) third metatarsal length/width index. Dark grey=cursorial; middle grey=ambulatory; light gray,= swimming; black=unknown (see Candela et al., Reference Candela, Muñoz and García-Esponda2017).

The preserved portion of the cuboid indicates that, as in other cavioids, the dorsal face of this bone is smaller than the ectocuneiform (Fig. 3.2). The calcaneo-cuboid facet of the cuboid is also similar to that of other cavioids. The plantar process of this bone is robust (Fig. 3.5), similar to that of Hydrochoerus (Fig. 3.4) and caviines but somewhat more robust than that of Dolichotis (Fig. 3.6).

The ectocuneiform shows the typical plantar extension observed in other cavioids. Its dorsal surface has a subrectangular outline, being relatively proximodistally longer than that of Hydrochoerus but shorter than that of Dolichotis (Fig. 3.1–3.3).

The third metatarsal (Fig. 3.2) is relatively more gracile and elongated than that of Hydrochoerus (Fig. 3.1) and Cuniculus but more robust than that of Dolichotis (Fig. 3.3), Cavia Pallas, Reference Pallas1766, and Galea Meyen, Reference Meyen1833 (Fig. 4.2).

The preserved proximal portions of the second and fourth metatarsals (Fig. 3.2) are morphologically similar but slenderer than those of Hydrochoerus (Fig. 3.1). The proximal and middle phalanges of the third digit and the middle phalanx of the forth digit are slenderer than those of Hydrochoerus and morphologically similar to those of Caviodon.

Materials

MLP 29-IX-3-19, right M3, distal ends of both humeri, proximal portions of both ulnae, right radius without its distal end, proximal portion of the left radius, left pisiform, proximal end of the left fourth metacarpal, portion of the left ischium, distal end of the right fibula, right calcaneus and partially preserved right navicular, right ectocuneiform, poorly preserved right cuboid, right Mt III, proximal portions of right Mt II and Mt IV, right proximal and middle phalanges of the third digit and middle phalanx of the fourth digit of the pes.

Remarks

Specimen MLP 29-IX-3-19 is referred to Cardiomys because its M3 has four prisms, which are relatively anteroposteriorly wider and present relatively more superficial labial flexi (= sulci) than those of Caviodon and Xenocardia species (Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, Ortega Hinojosa, Gondar and Tonni1966; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Carlini, Aguilera and Sánchez-Villagra2010; Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Deschamps, Morgan and Forasiepi2011). Therefore, we excluded assignment to Caviodon australis Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1888 (Montehermosan, early Pliocene; Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914) and Caviodon pozzi Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1927 (Chapadmalalan, late Pliocene) as both species have M3 with more prisms and much more penetrating fissures. Xenocardia (Chasicoan?) was also eliminated as it also has more penetrating labial flexi and more delicate prisms (Vucetich et al., Reference Vucetich, Carlini, Aguilera and Sánchez-Villagra2010). Specimen MLP 29-IX-3-19 also differs from the type of Procardiomys martinoi Pascual, Reference Pascual1961 because the latter has an M3 with three lobes and a well-developed posterior projection (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vucetich and Deschamps2014). The M3 of the type of Cardiomys ameghinorum Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914 has four prims and one posterior projection (a fifth small lobe) that is well differentiated from the last prism by a lingual flexus. Specimen MLP 29-IX-3-19 differs from the type of this species because the fourth prism of M3 is narrower than the third and the posterior projection is continuous with the fourth prism. The M3 of the specimen MLP 29-IX-3-19 is very similar in size and general morphology (number and relative size of prisms, depth of labial flexi) to that of the type of Cardiomys leufuensis, but differs from it in the morphology of the second prism, which has two labial flexi in MLP 29-IX-3-19 and a straight labial side in C. leufuensis (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Deschamps and Vucetich2017a, fig. 6F). Besides this difference, all other shared features support the specific assignment of the MLP 29-IX-3-19 to C. leufuensis.

Discussion

Systematic considerations on the postcranial features

The phylogeny of Cavioidea has been based on molecular, cranial, and dental data while postcranial features have not been analyzed from a systematic point of view. Our study indicates that many postcranial features of Cardiomys are shared with other analyzed cavioids (proximal portion of radius cranially located with respect to the ulna, olecranon fossa perforated, distal articular humeral surface relatively high, radial head lateromedially extended and posteriorly flattened, distal portion of calcaneus extended, dorsal face of cuboid smaller than that of ectocuneiform). Character mapping (Fig. 5) indicates that the extreme reduction of the lateral coronoid process of the ulna (character state 31), presence of a greatly differentiated capitular tail of the humerus (character state 52), shortening of the Mt III (character 1), and shortening of the plantar process of the navicular (character 2) would be potential synapomorphies of Hydrochoerinae, in the context of Cavioidea. Thus, these characters support Cardiomys as within Hydrochoerinae, in agreement with phylogenetic hypothesis based on other morphological characters. Optimization of robustness of Mt III (character 1) shows that dolichotines have a more slender Mt III than the remaining cavioids, whereas the Hydrochoerinae display the most robust Mt III in the context of this group. Within the Hydrochoerinae, Mt III of Cardiomys is less robust than that of Hydrochoerus, closer to the ancestral condition of this clade. In the phylogenetic context of cavioids, the well-differentiated and craniodistally narrow capitular tail facet of the radius (character state 62) is a feature only present in Cardiomys and Hydrochoerus. However, ambiguous optimization of this feature at the node of the clade that contains Dolichotinae and Hydrochoerinae precludes us from inferring whether this feature could be a potential synapomorphy of Hydrochoerinae. Chasicoan hydrochoerines have been recognized as critical to understanding the early evolution of the group because they display dental features that anticipate the derived dentition of modern capybaras (Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vucetich and Deschamps2014). In agreement with this, some postcranial features of Cardiomys seem to be more generalized than those of modern capybaras (relatively more gracile and longer Mt III and phalanges and straight caudal border of the ulna). The presence of a single radial notch of the ulna (character 40) in Cardiomys would be a reversion to the plesiomorphic condition present in Cuniculus. A phylogenetic study based on wider taxon and character sampling could test whether the common features of Cardiomys and Hydrochoerus are synapomorphies of hydrochoerines and whether postcranial characters support Cardiomys as a basal hydrochoerine.

Figure 5 Mapping of six anatomical characters, as reconstructed using parsimony, onto the phylogeny of Cavioidea modified from Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez (Reference Madozzo-Jaén and Pérez2017). Only unambiguous character state optimizations are shown. For discrete characters (circles), numbers above branches indicate character number whereas those below are character states. For continuous characters, closed/open squares indicate an increase/decrease of the measurements (see Supplemental Data 3 for characters and character states).

Paleobiology based on postcranial features

The elbow joint of Cardiomys displays several features that indicate a relatively high stability and restricted rotational movements, as are observed in other cavioid rodents. A high humeral distal surface and a steeply angled trochlea, which contacts with the medially extended trochlear facet of the radius, restrict mediolateral mobility and increase stability at the elbow joint during flexion-extension (Argot, Reference Argot2001; Sargis, Reference Sargis2002; Candela and Picasso, Reference Candela and Picasso2008; Abello and Candela, Reference Abello and Candela2010). The markedly differentiated humeral capitular tail, which contacts with the laterally extended capitular tail facet of the radius during the flexion, also maximizes the stability at the humeroradial joint. The subrectangular radial head with a flattened caudal ulnar facet restricts the arc through which the radius may be rotated and prevents supination (Taylor, Reference Taylor1974; Szalay and Sargis, Reference Szalay and Sargis2001). The cranially located radial head with respect to the ulna also leads to a severe restriction of supination, indicating that the radius is more efficient in incurring loads at the humeroradial joint during locomotion (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins1973; Argot, Reference Argot2001; Sargis, Reference Sargis2002; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2003). These features would be effective for resisting mediolateral forces at the elbow joint, maximizing the stability of the humeroradial, radioulnar, and humeroulnar joints and restricting rotational movements. A perforated fossa and a relatively long olecranon (the attachment site for the m. triceps brachii) are features compatible with a strong extension of the forearm, which could be advantageous for digging or swimming (Hildebrand, Reference Hildebrand1985; Samuels and Van Valkenburgh, Reference Samuels and Van Valkenburgh2008). The orientation of the olecranon process with respect to the ulnar shaft has been related to the effectiveness of the lever arm of the triceps muscle, the primary extensor of the elbow joint, maximizing the action of this muscle at certain joint angles (Van Valkenburgh, Reference Van Valkenburgh1987; Drapeau, Reference Drapeau2004; Fujiwara, Reference Fujiwara2009). Therefore, the straight caudal border of the olecranon of Cardiomys suggests that this genus would have had a lower elbow joint angle during the stance phase of locomotion than Hydrochoerus, having a more crouched position of its forelimbs (Fujiwara, Reference Fujiwara2009). In addition, the caudally oriented olecranon of Hydrochoerus may represent a consequence of its larger body size, a condition that was also observed in other groups of mammals (e.g., Van Valkenburgh, Reference Van Valkenburgh1987; Drapeau, Reference Drapeau2004).

As in other cavioid rodents, the configuration of the ectal, sustentacular, and cuboid facets of the calcaneus indicates relatively high stabilization of the foot, restricting mediolateral movements and emphasizing flexion-extension. Likewise, the calcaneocuboid joint is more distally located with respect to the astragalonavicular joint, further restricting mediolateral movements (Candela and Picasso, Reference Candela and Picasso2008; Candela et al., Reference Candela, Muñoz and García-Esponda2017).

According to García-Esponda and Candela (Reference García-Esponda and Candela2016), the hind limb of the capybara differs from that of other semiaquatic rodents (see Samuels and Van Valkenburgh, Reference Samuels and Van Valkenburgh2008) in exhibiting a lower pes index, which could be related with an increment of the out-force generated by the foot during swimming. Cardiomys displays relatively longer and slenderer ectocuneiform, metatarsal III, and phalanges with respect to those of Hydrochoerus (Fig. 4). These features indicate that Cardiomys would have had a longer and more gracile foot than extant capybaras. Therefore, the pes of Cardiomys would not have reached the degree of swimming specialization exhibited by Hydrochoerus. In turn, Cardiomys would have had a shorter foot with respect to the cursorially adapted Dolichotis and Dasyprocta. This feature suggests that running adaptations were absent in Cardiomys.

In summary, in the context of the Cavioidea, the postcranial features of Cardiomys are interpreted neither as adaptations to highly specialized cursoriality, such as those of Dolichotis (Candela and Picasso, Reference Candela and Picasso2008; García-Esponda and Candela, Reference García-Esponda and Candela2010), nor as specializations to an aquatic mode of life. Cardiomys exhibits several features shared with other cavioids that allow us to consider it as a generalized ambulatory species.

Considering the morphology and relative size of the pes of the extinct hydrochoerines Cardiomys and Phugatherium Ameghino, Reference Ameghino1887 (= Protohydrochoerus Rovereto, Reference Rovereto1914, a large cursorial hydrochoerine from the late Miocene–early Pliocene of Argentina; Kraglievich, Reference Kraglievich1940), the shortening of the pes appears to be an acquisition of the more recent genus Hydrochoerus. Therefore, the origin of a semiaquatic lifestyle in capybaras is likely a recent (Pleistocene) adaptation in the context of the evolutionary history of Hydrochoerinae. Thus, we hypothesize that the morphology of Cardiomys represents an ancestral postcranial pattern of hydrochoerines.

Conclusions and final remarks

Features of Cardiomys are more similar to Hydrochoerus than to any other Cavioidea, which seems to be compatible with the phylogenetic information provided by dental and cranial data (e.g., Pérez et al., Reference Pérez, Vallejo-Pareja, Carrillo and Jaramillo2017b). Our results indicate that Cardiomys can be considered an ambulatory rodent. Like the dental structure, the postcranial features of these rodents show a more generalized morphology than extant capybaras. As recently proposed by García-Esponda and Candela (Reference García-Esponda and Candela2016), adaptations to semiaquatic habits would have occurred more recently in the evolution of the Hydrochoerus lineage.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank M. Reguero (MLP), P. Teta (MACN), D. Voglino (MPS-Z), I. Olivares (MLP), D. Verzi (MLP), U. Pardiñas (CNP), D. Romero (MMPMa), E. Westwig (AMNH), and K. Zyskowski (YPM) for access to collections under their care. Special thanks to the reviewers C.M. Deschamps and J.X. Samuels for their valuable suggestions and comments, which improve an earlier version of our manuscript.

Accessibility of supplemental data

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.f8h7h