Introduction

Ostracodes are small crustaceans with a calcified bivalved carapace that are easily preserved as fossils. The record of the group extends back to the Ordovician, which coupled with their abundant fossil record ecology and dispersal mechanisms makes them good index fossils for biostratigraphy (Meisch, Reference Meisch, Schwoerbel and Zwick2000; Horne, Reference Horne2002, Reference Horne, Whittaker and Hart2009; Sames, Reference Sames2011a, Reference Samesb, Reference Samesd; Sames and Horne, Reference Sames and Horne2012; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sha, Pan and Zuo2016, Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017; Do Carmo et al., Reference Do Carmo, Spigolon, Guimarães, Richter, Mendonça Filho, Xi, Caixeta and Leite2018). Cretaceous limnic ostracodes have been widely studied worldwide (e.g., Anderson, Reference Anderson1941, Reference Anderson1985; Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Horne, Reference Horne1995, Reference Horne2002, Reference Horne, Whittaker and Hart2009; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2006; Whatley and Bajpai, Reference Whatley and Bajpai2006; Khand et al., Reference Khand, Sames and Schudack2007; Do Carmo et al., Reference Do Carmo, Whatley, Queiroz Neto and Coimbra2008, Reference Do Carmo, Coimbra, Whatley, Antonietto and De Paiva Citon2013; Sames, Reference Sames2008, Reference Sames2011a, Reference Samesb; Antonietto et al., Reference Antonietto, Gobbo, Do Carmo, Assine, Fernandes and Silva2012; Poropat and Colin, Reference Poropat and Colin2012a, Reference Poropat and Colinb; Sames and Horne, Reference Sames and Horne2012; Ayress and Whatley, Reference Ayress and Whatley2014; Tomé et al., Reference Tomé, Lima Filho and Neumann2014; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Jugdernamjil, Huh and Khand2017). However, ostracode fossils from the early- to mid-Late Cretaceous remain less understood, despite strata of such age being broadly distributed throughout terrestrial successions in China.

The Songliao Basin in northeastern China is one of the largest nonmarine basins worldwide, with a continuous Cretaceous terrestrial sedimentary record (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Jia, Xie, Zhang, Feng and Cross2010; C. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Feng, Zhang, Huang, Cao, Wang and Zhao2013). Ostracode fossils are very abundant in Upper Cretaceous strata of the Songliao and provide unique materials to study Late Cretaceous limnic ostracode faunas (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014). An extensive taxonomic analysis of the ostracodes from the Songliao Basin has been conducted in the past 60 years, with plenty of species described (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Zhang and Zhang2007; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). More recent works, however, suggest diversity and endemicity in the Songliao (and other Chinese basins) has been overestimated (Khand et al., Reference Khand, Sames and Schudack2007; Horne, Reference Horne, Whittaker and Hart2009; Schudack and Schudack, Reference Schudack and Schudack2009; Sames, Reference Sames2011a, Reference Samesb; Y. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sha and Pan2013, Reference Wang, Sha, Pan and Zuo2016; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Xi, Sames, Do Carmo and Wan2018). This can be attributed to a myriad of mishandlings by previous authors, including: (1) descriptions, diagnoses, and illustrations frequently ambiguous; (2) ontogeny and potential sexual dimorphism of species often ignored; and/or (3) information from previous literature wrongly reproduced on remarks about these taxa. Furthermore, most research efforts in the Songliao have focused on central and northern portions of the basin (e.g., Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Zhang and Zhang2007; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Xi, Huang, Nie, Cao and Wan2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017).

There are few outcrops in Songliao Basin, so most records come from wells such as the ZKY2-1, D80, Xing-104, SK-1, and SK-2 of the continental scientific drilling program. The present work is a detailed taxonomic study of the Upper Cretaceous ostracode faunas recovered from sediments of members 1 and 2 of the Nenjiang (lower Santonian–lower Campanian) and the Sifangtai formations (upper Campanian) at the ZKY2-1 well in the southwestern region of the Songliao Basin. This study will provide important information for comparison of southern Songliao ostracode faunas with those from central and northern portions of the basin. It will also help clarify stratigraphic relationships between basins worldwide that are based on the biostratigraphical application of Late Cretaceous limnic ostracode taxa.

Geological setting

The lithologic record of the Songliao Basin mainly comprises fine clastic rocks intercalated with oil shales (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the Songliao Basin, the Upper Cretaceous strata have been subdivided into six formations, from older to younger: Quantou (K2q), Qingshankou (K2qn), Yaojia (K2y), Nenjiang (K2n), Sifangtai (K2s), and Mingshui (K2m) (e.g., Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhao, Scott, Wang, Feng, Huang and Xi2013; C. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sha and Pan2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Wan, Li and Li2019). The Cretaceous biota in the Songliao Basin includes ostracodes, spores and pollen, dinoflagellates, charophytes, spinicaudatans, gastropods, bivalves, fish, and dinosaurs (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhang and Cui1994; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chen, Wang, Han, Li and Wu1998; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012, Reference Xi2016; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhao, Scott, Wang, Feng, Huang and Xi2013).

The upper Santonian–middle Campanian Nenjiang Formation was deposited during the post-rift phase of the basin (He et al., Reference He, Deng, Wang, Pan and Zhu2012; Deng et al., Reference Deng, He, Pan and Zhu2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Jiang, Hinnov, Yang, Li, Wan and Wang2013; Wang and Chen, Reference Wang and Chen2015; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Wan, Li and Li2019; Yu et al., Reference Yu, He, Deng, Xi, Qin, Wan, Wang and Zhu2019). It is divided into five distinctive members, based on their lithofacies and fossil assemblages, respectively numbered 1–5. Member 1 comprises retrograding deltaic sediments that consist mainly of dark-gray or black mudstones and grayish to green silty mudstones intercalated with thin carbonates. Members 2–5 were deposited on a large lake environment formed under forced regression of progradational deltas (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Zhang and Fu2012). Member 2 is composed of grayish to black mudstones interbedded with black shales near its top and oil shales at the bottom; these shales are an important element of stratigraphic correlation in the whole basin as they indicate maximum-flooding surfaces (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Zhang and Fu2012; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012). Members 3–5 (not observable in the ZKY2-1 well) consist of grayish to black mudstones, gray argillaceous siltstones, and brownish-red mudstones and sandstones (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gao, Cheng, Wang, Wu, Wan, Yang and Wang2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017).

The age of the Sifangtai Formation is interpreted as late Campanian (Deng et al., Reference Deng, He, Pan and Zhu2013; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhao, Scott, Wang, Feng, Huang and Xi2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhang, Hinnov, Jiang, Yang, Li, Wan and Wang2014). The Sifangtai Formation comprises sedimentary facies that are predominantly representative of riverine and lacustrine systems, as well as other associated environments (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Wang, Wang and Gao2009). The lower part of the formation is characterized by red gravel-bearing siltstones with grayish to green pelitic siltstones that were deposited in meandering river systems. The middle part is composed of gray to black mudstones with some siltstone levels, deposited in shallow lake sediments. The upper part comprises red and greenish clastic sediments characteristic of floodplain sedimentary facies (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gao, Cheng, Wang, Wu, Wan, Yang and Wang2011; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014).

Locality information

The ZKY2-1 well is situated in the southwestern part (43°56′59″N, 122°33′45″E) of the Songliao Basin (Fig. 1). It consists of an Upper Cretaceous–Neogene sequence starting at the upper Quantou Formation and ending at the lower Taikang Formation (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Li, Wang, Li, Ao, Li, Sun, Li and Zhang2018). The lithology of the present samples (Fig. 2) is typical of members 1 and 2 of the Nenjiang Formation (primarily black or dark-gray silty mudstones) and of the lower Sifangtai Formation (grayish to green pelitic siltstones).

Figure 1. (1) Schematic map of the Songliao Basin, northeastern China, showing the distribution of first-order tectonic subunits (modified from Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002) and location of the ZKY2-1 well. (2) Lithological chart of the Upper Cretaceous of the Songliao (modified from Wang and Chen, Reference Wang and Chen2015). Sifangtai and Nenjiang formations (black in color) are investigated in this study.

Figure 2. Lithostratigraphy, sampled horizons, and occurrence of ostracode species in the studied section of the Nenjiang Formation in the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China. Sample numbers shown in the figure indicate those that contained fossils.

Materials and methods

One hundred two core samples were collected and analyzed from the ZKY2-1 well in the Songliao Basin. They were collected from the 1.0 to ~5.0 m interval and processed; 36 samples yielded fossils of ostracodes, 9 contained gastropods, and 11 bore charophytes.

Rock samples were fragmented then soaked in water or hydrogen peroxide for 12 hours. Following that, the fragmented content was washed through a series of sieves (pore sizes of 600, 250, 150, 90, and 53 μm) and later oven dried. Ostracode fossils were picked from dried samples under an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope. Selected specimens of each identified species (carapaces and/or valves) were coated with an ultrafine layer of gold in a Leica EM ACE600. These were then photographed on a Zeiss-SupraTM 55 field-emission scanning electron microscope at the State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology of the China University of Geosciences, located in Beijing, China.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

Samples were labeled as ZKY2-1-1 to 102. Illustrated specimens are housed in the Micropaleontology Laboratory of the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, in a collection specific for ostracodes. The prefix used is ZKY.O (“well name” dot “ostracode”) and numbers 1–35.

Systematic paleontology

The suprafamiliar classification follows Liebau (Reference Liebau2005) and Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), while the generic taxonomy is based on Khand (Reference Khand2000) and Do Carmo et al. (Reference Do Carmo, Coimbra, Whatley, Antonietto and De Paiva Citon2013). The morphological terminology is based on Sames (Reference Sames2011a, Reference Samesb, Reference Samesc). Abundance ranges of specimens are as follows: rare = fewer than 10, common = 10–30, frequent = 31–50, and abundant = more than 50 individuals.

Subclass Ostracoda Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Superorder Podocopomorpha Kozur, Reference Kozur1972

Order Podocopida Sars, Reference Sars1866

Suborder Cypridocopina Jones, Reference Jones1901

Superfamily Cypridoidea Baird, Reference Baird1845

Family Ilyocyprididae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900

Genus Ilyocyprimorpha Mandelstam in Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955

Type species

Ilyocyprimorpha palustris Mandelstam, Reference Mandelstam and Schneider1956.

Remarks

Mandelstam (in Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955) erected the Genus Ilyocyprimorpha on the basis of several morphological characters, such as a wide anterodorsal sulcus, an anterior crescent-shaped tooth at the left valve, and a feature that used to be called “inverse valve size relation” (right valve larger than the left one). However, this last concept is in disuse in ostracode taxonomy because further studies often tend to invalidate valve size relations previously established as norm for ostracode genera. This was keenly observed by Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), who found several instances where Ilyocyprimorpha species from China presented “normal valve size relation” (left valve larger than the right one).

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959, emend.

Figure 3.4–3.11

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 36, pl. 11, fig. 4a–e.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae; Hou and Chen, p. 98, pl. 23, fig. 3a–e.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae; Hao et al., p. 51, pl. 18, fig. 3a–f.

- pars Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea ordinata; Hao et al., p. 37, pl. 18, fig. 1a–c.

- 1976

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae; DOFEAD, p. 62, pl. 22, fig. 1a, b.

- 1976

Cypridea ordinata Ye in DOFEAD, p. 60, pl. 19, figs. 8a, 9b.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 624, pl. 260, figs. 3–6.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea ordinata; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 414, pl. 158, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae; Ye et al., p. 198, pl. 36, fig. 4a–c.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea ordinata; Ye et al., p. 167, pl. 15, fig. 1a, b.

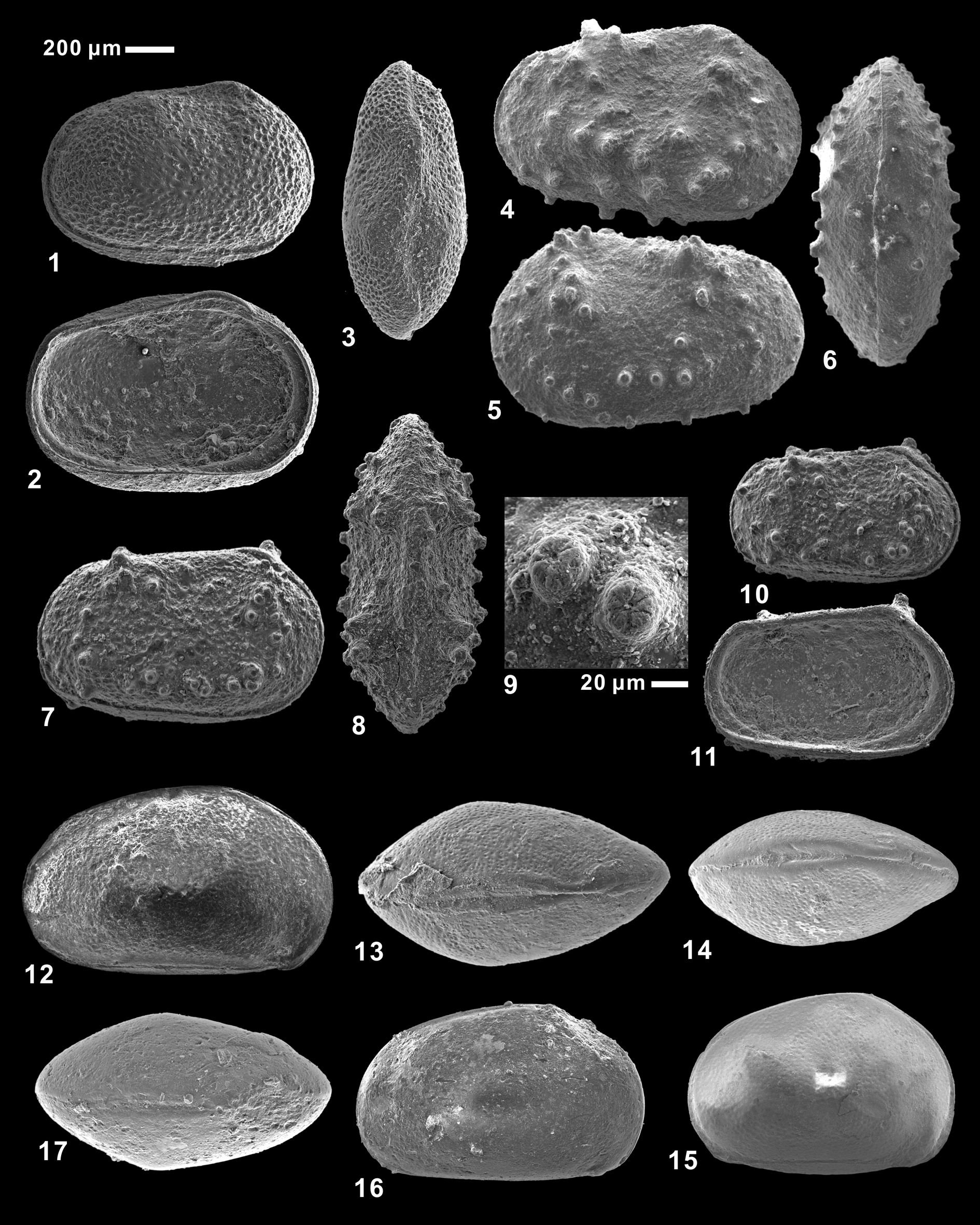

Figure 3. Photomicrographs of ostracode species recovered from the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China. (1–3) Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis Anderson, Reference Anderson1941: (1, 3) adult carapace (ZKY.O 16): (1) right view and (3) dorsal view; (2) adult left valve (ZKY.O 17), internal view. (4–11) Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959: (4–6) adult carapace (ZKY.O 18): (4) right view, (5) left view, and (6) ventral view; (7, 8) A-1 carapace (ZKY.O 19): (7) right view and (8) dorsal view; (9, 10) A-2? carapace (ZKY.O 20): (9) detail of one large tubercle showing its apical star-crossed pattern and (10) right view; (11) A-1 left valve (ZKY.O 21), internal view. (12–17) Cypridea acclinia Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959: (12, 13) male adult carapace (ZKY.O 25): (12) right view and (13) dorsal view; (14, 15) female adult carapace (ZKY.O 26): (14) dorsal view and (15) right view; (16, 17) male adult internal mold (ZKY.O 24): (16) right view and (17) dorsal view. (1–8, 10–17) Scale bars = 200 μm; (9) scale bar = 20 μm.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 14) from the Upper Cretaceous middle Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Diagnosis (emended)

A species of Ilyocyprimorpha distinguished by rounded, infracurvate anterior end; rounded, equicurvate posterior end; punctate to reticulated surface, bearing several tubercles in a horseshoe-shaped pattern opening toward the dorsal margin; three or four tubercles aligned in front of the anterodorsal sulcus on the left valve.

Occurrence

China: Jilin Province, cities of Gongzhuling and Baicheng and counties of Changling and Nongan; Heilongjiang Province, cities of Suihua, Anda, and Harbin; Songliao Basin, Nenjiang Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Member 2 of the Nenjiang Formation, Upper Cretaceous, upper Santonian–lower Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Description (emended)

Large, posteriorly tilted trapezoidal carapace in lateral view, with its greatest length at mid-height and greatest height at the anterocentral region, right at the anterior cardinal angle. Left valve larger than the right one, overlapping it along the free margin. Rounded, infracurvate anterior end; rounded, equicurvate posterior end. Almost straight, but not parallel, dorsal and ventral margins; dorsal margin inclined toward the posterior end ~10°–16°. Anterior cardinal angle at 132°–136°; rounded posterior cardinal angle at 117°–123°. Slight anterodorsal sulcus originated in the posterior margin and reaching downward up to mid-height. Carapace coarsely punctate tending toward reticulation, ornamented with massive tubercles with a star-crossed indentation at its apical portion, coupled with smaller, regular tubercles; together they form two horseshoe-shaped patterns that run from the dorsoanterior to the ventrocentral to the dorsoposterior regions of the valve, where the largest tubercles are observable (one or two of them, also in the dorsoanterior end); three or four tubercles aligned in front of the anterodorsal sulcus on the left valve. Dorsal view elliptical and tapering moderately toward both ends, with greatest width at the middle. In internal view, well-developed inner lamella, visible in both anterior and posterior ends; narrowly developed fused zone, selvage overlapping lamella. Compared with adults, juveniles present lower inclination of the hinge margin, weakly developed anterodorsal sulcus, and tubercles distributed mainly in a single row along the carapace surface.

Materials

One hundred two carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-53 sample, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.050–1.324 mm and height = 0.642–0.813 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959). Considering there was no original diagnosis in that work and that the studied material presents several well-preserved instars of the species, the present authors decided to propose a new one and description for the species. Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 is an index fossil of Member 2 of the Nenjiang Formation, easily identifiable by the double row of tubercles in the lateral surface of the carapace, forming a horseshoe-shaped pattern open toward the dorsal margin. Ye in Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974) described (as nomen nudum) a new species, Cypridea ordinata Ye, in DOFEAD, 1976 (formally published in DOFEAD, 1976), from the same Nenjiang Formation where Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae was described (in some previous cases, both were found in the same localities and age) (DOFEAD, 1976; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). However, Cypridea ordinata exhibits none of the morphological features traditionally associated with the Genus Cypridea Bosquet, Reference Bosquet1852 (e.g., beak, alveolus, and cyathus) (Do Carmo et al., Reference Do Carmo, Whatley, Queiroz Neto and Coimbra2008, Reference Do Carmo, Coimbra, Whatley, Antonietto and De Paiva Citon2013; Sames, Reference Sames2011a). Queiroz Neto et al. (Reference Queiroz Neto, Sames and Colin2014) mentioned Cypridea ordinata as a possible representative of the genus Kegelina Queiroz Neto, Sames, and Colin, Reference Queiroz Neto, Sames and Colin2014 despite Cypridea ordinata not displaying the weak cyathus that is diagnostic of Kegelina. Cypridea ordinata is very similar to Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae in lateral and dorsal views and internal features, although smaller and with fewer tubercles in the lateral surface. The analysis of specimens from the present work allowed us to establish a length/height plot (Fig. 4) that indicates both species are different instars (adult, A-1 and A-2?) of the same one. Therefore, we opt to designate Cypridea ordinata as a junior synonym of Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae.

Figure 4. Plot of length versus height of Ilyocyprimorpha netchaevae. Specimens in present work are from Member 2 of the Nenjiang Formation in the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China.

Genus Scabriculocypris Anderson, Reference Anderson1941

Type species

Scabriculocypris trapezoides Anderson, Reference Anderson1941.

Remarks

Anderson (Reference Anderson1941) established Scabriculocypris but did not assign it to a family. Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002) allocated this genus to the family Limnocypridae Mandelstam, 1948, but the name of this family is a nomen nudum (Sohn, Reference Sohn1979). Horne (Reference Horne2002) designated it to the family Cyprididae, common in Recent environemnts; however, representatives of this family usually are identified by analysis of soft parts (Meisch, Reference Meisch, Schwoerbel and Zwick2000), which are unknown in the fossil Scabriculocypris. Here, we follow Anderson and Bazley (Reference Anderson, Bazley and Anderson1971) and attribute Scabriculocypris to the family Ilyocyprididae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900 due to the suggestion of the presence of the highly diagnostic two dorsolateral sulci of that family.

Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis (Liu in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959)

Figure 3.1–3.3

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea liaukhenensis Liu in Netchaeva et al., p. 21, pl. 6, fig. 2a–c.

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea spongvosa Sou in Netchaeva et al., p. 27, pl. 8, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Harbinia lauta Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 45, pl. 14, fig. 6a–c.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea liaukhenensis; Hou and Chen, p. 72, pl. 15, fig. 5a–c.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea spongvosa; Hou and Chen, p. 76, pl. 16, fig. 4a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea liaukhenensis; Hao et al., p. 34, pl. 9, fig. 2a–c.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea spongvosa; Hao et al., p. 28, pl. 6, fig. 2a, b.

- 1976

Cypridea liaukhenensis; DOFEAD, p. 48, pl. 12, figs. 1–4.

- 1976

Cypridea spongvosa; DOFEAD, p. 48, pl. 12, fig. 5a, b.

- Reference Hou1984

Cypridea lauta; Hou, p. 22, pl. 1, figs. 7–9, pl. 2, fig. 1.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea spongvosa; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 463, pl. 172, figs. 10, 11.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Latonia liaukhenensis; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 654, pl. 280, figs. 16, 17.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea liaukhenensis; Ye et al., p. 164, pl. 12, fig. 1a–j.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea spongvosa; Ye et al., p. 164, pl. 12, fig. 2a–d.

- Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012

Cypridea liaukhenensis; Xi et al., p. 116, fig. 2.29.

- Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017

Latonia liaukhenensis; Wang et al., p. 181, figs. 4B, 6B–F.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 131) from the Upper Cretaceous middle Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

China: Jilin Province, cities of Gongzhuling, Baicheng, and Shuangliao and counties of Changling and Tongyu, and Heilongjiang Province, Suihua City; Songliao Basin, Nenjiang Formation, members 1–5, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). In the present work, Member 2 of the Nenjiang Formation, upper Santonian–lower Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

One hundred twenty-eight carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-53 sample, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.024–1.324 mm and height = 0.719–0.903 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). This species has most recently been reassigned to Latonia Mandelstam in Mandelstam and Schneider, Reference Mandelstam and Schneider1963 by Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). However, aside from the name being preoccupied by Latonia Meyer, Reference Meyer1843 (a genus of frogs), none of these species exhibits the diagnostic feature of Latonia: a row of small, pronounced spines around the free margins in both valves. Considering all that, and since specimens present several morphological characters (trapezoidal overall shape and presence of a shallow anterodorsal sulcus, lophodont-type hinge and widest anteriorly, and posteriorly free inner lamella) typical of Scabriculocypris, we decided to transfer Latonia liaukhenensis (Liu in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959) to the Genus Scabriculocypris Anderson, Reference Anderson1941. Cypridea spongvosa Sou in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 and Harbinia lauta Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959, described from the Upper Cretaceous of the Songliao Basin, share similar external features and size with Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis. Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017) considered specimens of Harbinia lauta with smaller size as juveniles of Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis. Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002) pointed out the original measurement of Harbinia lauta is incorrect; the proper measurement is presented in Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), and it corresponds to the size of Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis. Therefore, we regard Cypridea spongvosa and Harbinia lauta as synonyms of Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis. Anderson (Reference Anderson1941) described Scabriculocypris trapezoides Anderson, Reference Anderson1941 from England Purbeckian strata; it closely resembles Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis but has a smaller size and could be a juvenile form of Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis. However, since it is also from the Lower Cretaceous, with no occurrence through the entire Valanginian–Turonian interval, placing Scabriculocypris liaukhenensis as a junior synonym of Scabriculocypris trapezoides remains a dubious alternative.

Family Cyprideidae Martin, Reference Martin1940

Subfamily Cyprideinae Martin, Reference Martin1940

Genus Cypridea Bosquet, Reference Bosquet1852

Type species

Cypris granulosa Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1836 (designated by Sylvester-Bradley, Reference Sylvester-Bradley1949).

Cypridea acclinia Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959, emend.

Figure 3.12–3.17

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea acclinia Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., p. 11, pl. 3, fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea gunsulinensis Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 19, pl. 5, fig. 4a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea acclinia; Hao et al., p. 67, pl. 14, fig. 3a, b.

- 1976

Cypridea acclinia; DOFEAD, p. 41, pl. 8, fig. 4a, b.

- 1976

Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; DOFEAD, p. 41, pl. 8, figs. 1a, b, 2, 3.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea gunsulinensis; Ye et al., p. 161, pl. 10, fig. 1a–d.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea acclinia; Ye et al., p. 162, pl. 10, fig. 4a, b, pl. 11, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea gracila; Ye et al., p. 162, pl. 10, fig. 3a–d.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea gunsulinensis; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 423, pl. 161, figs. 9, 10.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea acclinia; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 423, pl. 161, figs. 7, 8.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 17) from the Upper Cretaceous lower Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

China: Jilin Province, Gongzhulin City and counties of Kaitong, Dehui, Huaide, and Changling; Songliao Basin, Nenjiang, Yaojia and Fulongquan formations, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation, lower–middle Santonian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Description (emended)

Large, suboval carapace in lateral view, with its greatest length at mid-height and greatest height at the anterodorsal region, right at the anterior cardinal angle. Left valve larger than the right one, overlapping it along the entire margin but more strongly along the ventral one. Subrounded, infracurvate anterior end; in the contact with the ventral margin, a very weakly developed beak is present, along with a very weakly developed alveolus. Subrounded, equicurvate posterior end; in the contact with the ventral margin, a very weakly developed cyathus is present, but only in female specimens. Substraight dorsal margin, inclined toward the posterior end on a 14°–16° angle; ventral margin varying from nearly straight in the left to convex in the right valve. Anterior cardinal angle at about 127°–134°; posterior cardinal angle at about 125°–131°. Lateral surface ornamented by widespread, very small and weak punctuation. In dorsal view, lightly fusiform and with greatest width at the posterocentral region, tapering moderately toward both ends; hinge margin incised, forming a dorsal furrow from the anterocentral to the centroposterior regions. Sexual dimorphism as follows: males are more elongated than females in both lateral and dorsal views, present less valve overlap in the ventral margin, and do not possess a visible cyathus.

Materials

Five hundred ninety carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-66 (17), ZKY2-1-67 (33), ZKY2-1-68 (36), ZKY2-1-70 (56), ZKY2-1-71 (38), ZKY2-1-72 (73), ZKY2-1-74 (96), ZKY2-1-75 (123), ZKY2-1-77 (86), and ZKY2-1-78 (32) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.097–1.321 mm and height = 0.700–0.894 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959). Variation in several morphological structures of Cypridea acclinia Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 has been previously mentioned in literature, including the inclination of the dorsal margin, length/height ratio, and smooth versus punctate ornamentation of the lateral surface of valves (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). Such variation can be explained by internal molds, which present smooth surfaces and different length/height ratios or shape due to the total or partial abrasion of the carapace in such specimens (Fig. 3.16, 3.17). When the carapace is present, specimens will often display their characteristic punctate ornamentation (Fig. 3.12–3.15). Specimens of Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 in DOFEAD (1976) and Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002) share the ornamentation of the carapace with Cypridea acclinia and are herein identified as such. Two morphotypes of Cypridea acclinia were observed on the basis of their length/height ratio, overlapping ratio in the ventral margin, and presence/absence of cyathus. Hanai (Reference Hanai1951) and Sames (Reference Sames2011a, Reference Samesb) pointed out this is a common feature that can be interpreted as sexual dimorphism, provided such specimens are found in the same stratigraphic level. Due to the present abundance of well-preserved specimens, the authors opted to redescribe Cypridea acclinia to account for such interpretations on sexual dimorphism. From the holotype image reillustrated by Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), Cypridea gunsulinensis Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 displays all the morphological characters we proposed, and the synonymy is here confirmed, despite Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959) pointing out that Cypridea gunsulinensis differs from Cypridea acclinia in terms of anterior cardinal angle at mid-dorsal. Such difference is considered to be caused by incorrectly taken scanning electron microscope (SEM) picture (e.g., placement angle of specimen).

Cypridea cavernosa Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955

Figure 5.1–5.6

- Reference Galeeva1955

Cypridea cavernosa Galeeva, p. 42, pl. 10, fig. 1a–g.

- Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970

Cypridea cavernosa; Szczechura and Błaszyk, p. 109, pl. 25, fig. 2a–c.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea cavernosa; Hao et al., p. 39, pl. 12, fig. 1a–g.

- 1976

Cypridea aff. C. cavernosa; DOFEAD, p. 50, pl. 14, figs. 1a, b, 2a, b.

- 1976

Cypridea rhamphoformis Ye in DOFEAD, p. 51, pl. 14, figs. 3a, b, 4a, b, 5, 6.

- Reference Ye, Gou, Hou, Cao, Zhōngshēngdài Huàshí and Cè1977

Cypridea (Cypridea) cf. C. cavernosa; Ye et al., p. 217, pl. 7, figs. 25a, b, 26a, b, 27a, b.

- Reference Gou, Cao and Ye1978

Cypridea cavernosa; Gou et al., p. 51, pl. 2, figs. 6, 7.

- Reference Hou, Ho and Ye1978

Cypridea (Cypridea) cavernosa; Hou et al., p. 172, pl. 6, figs. 27, 28.

- Reference Guan1978

Cypridea (Cypridea) cavernosa; Guan, p. 159, pl. 38, figs. 16, 17.

- Reference Cao1985

Cypridea (Cypridea) cavernosa; Cao, p. 190, pl. 3, figs. 2–4.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea cavernosa; Ye et al., p. 175, pl. 20, fig. 2a–g.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea cavernosa; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 434, pl. 185, figs. 1–10.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Liu, Zhang and Chen2003

Cypridea cavernosa; Ye et al., p. 69, pl. 2, fig. 3a–c, pl. 3, fig. 3a–c.

- Reference Wang2019

Cypridea cavernosa; Wang et al., p. 7, fig. 4A–X.

Figure 5. Photomicrographs of ostracode species recovered from the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China. (1–6) Cypridea cavernosa Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955: (1, 2) male adult carapace (ZKY.O 01): (1) right view and (2) dorsal view; (3) female adult carapace (ZKY.O 02), right view; (4, 5, 6) female adult carapace (ZKY.O 03): (4) dorsal view, (5) right view, and (6) anteroventral region of the right valve. (7–11) Cypridea lepida Ye in DOFEAD, 1976: (7–9) adult carapace (ZKY.O 12): (7) right view, (8) left view, and (9) dorsal view; (10, 11) compressed adult carapace (ZKY.O 13): (10) right view and (11) dorsal view. (12–15) Cypridea squalida Sou in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959: (12, 14) adult carapace (ZKY.O 04): (12) right view and (14) dorsal view; (13, 15) A-1 carapace (ZKY.O 05): (13) dorsal view and (15) right view. (1–5, 7–15) Scale bars = 200 μm; (6) scale bar = 20 μm.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 200-53) from the Upper Cretaceous Nemeget Formation, Mongolia (Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955), housed in the collections of the All-Russia Petroleum Research Exploration Institute (originally, the All-Union Petroleum Research and Geological-Prospecting Institute), Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Occurrence

Mongolia: Ömnögovi Province, Gobi Desert, Nemegt and Altan (“Ula IV”) mountains, and Bugeen Tsav and Nogon Tsav localities; Nemegt Basin, Nemegt Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978). China: Jilin Province, Baicheng City, Songliao Basin, Fulongquan, Mingshui and Sifangtai formations, Upper Cretaceous (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002); Qinghai Province, Minhe Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Hao, Reference Hao, Hanai, Ikeya and Ishizaki1988); and Shandong province, Jiaolai Basin, Jiaozhou Formation (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Zhang, Cao and Horne2019). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation and the Sifangtai Formation, lower Santonian–middle Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

One hundred seventy-nine carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-32 (54), ZKY2-1-77 (37), ZKY2-1-78 (42), ZKY2-1-89 (28), ZKY2-1-92 (9), and ZKY2-1-93 (9) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.15–1.34 mm and height = 0.69–0.76 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Galeeva (Reference Galeeva1955). The presently recovered specimens are assigned to Cypridea cavernosa Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955. While there are variations between speciemens from China and the holotype in Mongolia (especially in size and degree of tuberculation), such variations are caused by environmental factors (e.g., water chemistry, temperature, and so one) and have been proved to taxonomic insignificance in Cypridea by Nye et al. (Reference Nye, Feist–Burkhardt, Horne, Ross and Whittaker2008) and Sames (Reference Sames2011c). Cypridea rhamphoformis Ye in DOFEAD, 1976 and Cypridea aff. C. cavernosa Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955 (in DOFEAD, 1976) do not differ in terms of morphology from Cypridea cavernosa; therefore, they are considered junior synonyms of Cypridea cavernosa by the present authors. Specimens of Cypridea cavernosa are abundant and well preserved in samples of the ZKY2-1 well, meaning two morphotypes, male and female, are identifiable; the male morphotype is represented by less inflated (in dorsal view) and more elongated (in lateral view) specimens compared with the female morphotype.

Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Figure 6.1, 6.2

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., p. 18, pl. 5, fig. 1a–d.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea gracila; Hao et al., p. 20, pl. 1, fig. 3a–e.

- 1976

Cypridea ardua Sou in DOFEAD; p. 41, pl. 8, fig. 6a, b.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea ardua; Ye et al., p. 163, pl. 11, fig. 1a–h.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea gracila; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 462, pl. 169, figs. 11, 12.

Figure 6. Photomicrographs of ostracode species recovered from the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China. (1, 2) Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959, adult carapace (ZKY.O 27): (1) right view and (2) dorsal view. (3–6) Fabaeformiscandona? disjuncta (Hao in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974): (3, 4) male adult carapace (ZKY.O 28): (3) dorsal view and (4) right view; (5, 6) female adult carapace (ZKY.O 29): (5) right view and (6) dorsal view. (7–11) Lycopterocypris profunda Lübimova, Reference Lübimova1956: (7, 8) adult carapace (ZKY.O 06): (7) right view and (8) dorsal view; (9–11) A-2 carapace (ZKY.O 07): (9) detail of porecanals on the carapace surface, (10) right view, and (11) dorsal view. (12–15) Mongolocypris magna (Hou, Reference Hou1958): (12, 13) adult carapace (ZKY.O 23): (12) right view and (13) dorsal view; (14, 15) A-1 carapace (ZKY.O 22): (14) right view and (15) dorsal view. (1–8, 10–15) Scale bars = 200 μm; (9) scale bar = 20 μm.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 10) from the Upper Cretaceous lower Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

China: Jilin Province, cities of Gongzhuling, Yufu and, Tongyu, and Heilongjiang Province, cities of Duerbote and Anda; Songliao Basin, Nenjiang and Yaojia formations, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation, lower–middle Santonian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

One hundred thirty-two carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-67 (11), ZKY2-1-68 (12), ZKY2-1-71 (32), ZKY2-1-72 (63), and ZKY2-1-75 (14) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.102–1.281 mm and height = 0.706–0.784 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959). Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974) considered Cypridea ardua Sou in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 as a synonym of Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959, an interpretation later followed by Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002). However, Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959) described Cypridea ardua with a pronounced anterior cardinal angle, more distinct node at the central region of each valve, lesser length/height ratios, and smooth lateral surface of the carapace. The present specimens match the description of Cypridea gracila in all but the ornamentation, which is less prominent than in the type specimens of the species; some even present a smooth lateral surface, such as that observed in Cypridea ardua (but not the other features of this species). Sames (Reference Sames2011a) interpreted such features as being a post-deposition product of diagenesis. Several of the present specimens are molds, which are formed only after deposition; therefore, diagenesis might have played a role in the preservation of the smooth specimens herein found. It is also possible that such variations among specimens of Cypridea gracila and between this species and Cypridea ardua (more specifically, those in outline shape and width variation) might be a product of sexual dimorphism. If such evaluation proves correct, Cypridea ardua would have priority as the name of the species. Specimens of Cypridea ardua Sou in DOFEAD, 1976 and Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002), as informed by the synonymic list, have all the diagnostic features of Cypridea gracila Netchaeva in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 and so are regarded as Cypridea gracila.

Cypridea lepida Ye in DOFEAD, 1976

Figure 5.7–5.11

- 1976

Cypridea lepida Ye in DOFEAD, p. 45, pl. 11, figs. 3a, b, 6.

- 1976

Cypridea anonyma Ye in DOFEAD, p. 47, pl. 11, figs. 7a, 8.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea anonyma; Ye et al., p. 169, pl. 17, fig. 1c, d.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea lepida; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 419, pl. 160, figs. 5–7.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 0145) from the Upper Cretaceous Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (DOFEAD, 1976). Unfortunately, this specimen and other types of Cypridea lepida were lost.

Occurrence

China: Heilongjian Province, Anda City, Nenjiang Basin, Nenjiang Formation, Upper Cretaceous (DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Wan, Feng, Li, Feng, Jia, Jing and Si2011; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhao, Scott, Wang, Feng, Huang and Xi2013). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation and the Sifangtai Formation, lower Santonian–upper Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

One hundred forty-seven carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-20 (20), ZKY2-1-35 (5), ZKY2-1-64 (13), ZKY2-1-88 (42), ZKY2-1-89 (22), and ZKY2-1-95 (45) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.468–1.623 mm and height = 0.839–0.954 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Ye in DOFEAD (1976). Cypridea lepida Ye in DOFEAD, 1976 and Cypridea anonyma Ye in DOFEAD, 1976 were proposed in the same work. Despite being considered different at the time, both species exhibit quite similar morphology. This was first recognized by Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), and we follow that interpretation. Cypridea menevensis Anderson, Reference Anderson1939 from Wealden, England, shows quite similar shape and length/height ratio to Cypridea lepida but differs from the latter by smaller carapace size and inverse overlap.

Cypridea squalida Sou in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Figure 5.12–5.15

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea squalida Sou in Netchaeva et al., p. 28, pl. 9, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea squalida; Hou and Chen, p. 77, pl. 16, fig. 5a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea squalida; Hao et al., p. 29, pl. 6, fig. 7a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea tuberculorostrata Su in Hao et al., p. 33, pl. 8, fig. 2a–f.

- 1976

Cypridea squalida; DOFEAD, p. 44, pl. 10, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Szczechura1978

Cypridea cavernosa; Szczechura, p. 83, pl. 18, figs. 1–6, pl. 36, figs. 5, 6, pl. 37, fig. 10.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea squalida; Ye et al., p. 165, pl. 13, fig. 1a–e.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Cypridea tuberculorostrata; Ye et al., p. 171, pl. 18, fig. 1a–i.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea squalida Hou, Gou, and Che, p. 417, pl. 159, figs. 8–10.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Cypridea tuberculorostrata; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 420, pl. 184, figs. 9–13.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 68) from Upper Cretaceous lower Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

Mongolia: Ömnögovi Province, Gobi Desert, Nemegt and Altan (“Ula IV”) mountains and Bugeen Tsav and Nogon Tsav localities; Nemegt Basin, Nemegt Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978). China: Jilin Province, cities of Baicheng and Gongzhulin and Changling County, and Heilongjiang Province, cities of Hailaer and Anda; Sifangtai, Mingshui, and Nenjiang formations, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang and the Sifangtai formations, lower Santonian–upper Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

Seventy-three carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-14 (13), ZKY2-1-24 (27), and ZKY2-1-92 (33) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.167–1.493 mm and height = 0.742–0.897 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959). Cypridea tuberculorostrata Su in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974 from the Sifangtai and Mingshui formations, displays external features that are similar to Cypridea squalida Sou in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 but differs by presenting smaller tubercules in the posterior region and around the beak (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974). The holotype of the species was reillustrated by Hou et al. (Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002), and due to the SEM technique employed, it was possible to identify conspicuous, well-developed tubercules similar to those in Cypridea squalida. The growth and development of tubercules is a phenotypical trait strongly controlled by environmental factors; therefore, it varies widely from individual to individual, as observed by Do Carmo et al. (Reference Do Carmo, Whatley and Timberlake1999) for Theriosynoecum kirtlingtonense Bate, Reference Bate1965. On the basis of this assumption, we consider Cypridea tuberculorostrata as a junior synonym for Cypridea squalida. Specimens of Cypridea cavernosa Galeeva, Reference Galeeva1955 in Szczechura (Reference Szczechura1978), from the Nemegt Formation, also match the description of Cypridea squalida and therefore are included in the present synonymic list.

Subfamily Cypridinae Baird, Reference Baird1845

Genus Mongolocypris Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978

Type species

Cypridea distributa Stankevitch and Sochava, Reference Stankevitch and Sochava1974.

Mongolocypris magna (Hou, Reference Hou1958)

Figure 6.12–6.15

- Reference Hou1958

Cypridea (Pseudocypridina) magna Hou, p. 84, pl. 11, figs. 1, 2, 4, pl. 12, fig. 12.

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea grandicula Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 19, pl. 7, fig. 4a, b.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea (Pseudocypridina) magna; Hou and Chen, p. 86, pl. 15, fig. 1a, b, pl. 19, fig. 2a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea (Pseudocypridina) magna; Hao et al., p. 32, pl. 12, fig. 4.

- 1976

Cypridea magna; DOFEAD, p. 55, pl. 17, figs. 6a, b, 7.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Mongolocypris magna; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 531, pl. 237, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Mongolocypris magna; Ye et al., p. 180, pl. 24, fig. 1a–f.

- Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017

Mongolocypris magna; Wang et al., p. 176, figs. 3A–J, 4A.

Holotype

A carapace (NGP. 6253) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Jilin Province, China (Hou, Reference Hou1958), housed at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China.

Occurrence

Mongolia: Choyr Basin, Khalzan Uul Formation, upper member, Lower Cretaceous, Albian (Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2006). China: Songliao Basin, Nenjiang Formation, Upper Cretaceous, Santonian–Campanian (Hou, Reference Hou1958; Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Li, Wan, Jing, Huang, Colin, Wang and Si2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation, lower–middle Santonian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

One hundred forty-five carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-64 (36), ZKY2-1-92 (28), ZKY2-1-95 (58), and ZKY2-1-97 (23) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.478–2.123 mm and height = 0.768–1.244 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Sames, Liao, Xi and Pan2017). On the basis of the ontogenic analysis of Mongolocypris magna (Hou, Reference Hou1958) in that work, we have identified 58 adults and 87 A-1 juveniles in the present material. Compared with A-1 juveniles, adults present a more noticeable beak, a less distinct alveolus, and a narrower, infracurvate posterior end of the carapace in lateral view.

Mongolocypris tera (Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959)

Figure 7.1–7.3

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea tera Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 28, pl. 7, fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959

Cypridea porrecta Su in Netchaeva et al., p. 25, pl. 6, fig. 5a, b.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea tera; Hou and Chen, p. 77, pl. 16, fig. 6a, b.

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea porrecta; Hou and Chen, p. 75, pl. 16, fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea tera; Hao et al., p. 35, pl. 10, fig. 1a–d.

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea porrecta; Hao et al., p. 33, pl. 8, fig. 3a, c.

- 1976

Cypridea tera; DOFEAD, p. 54, pl. 15, figs. 1a, b, 2, 3, 4a, b, 5.

- 1976

Cypridea porrecta; DOFEAD, p. 46, pl. 11, fig. 1a, b.

- Reference Guan1978

Cypridea (Pseudocypridina) cf. C. tera; Guan, p. 161, pl. 40, figs. 1–3.

- Reference Hou1982

Cypridea (Pseudocypridina) tera; Hou et al., p. 145, pl. 58, figs. 9–12.

- Reference Zhao1985

Cypridea tera; Zhao, p. 117, pl. 1, figs. 22, 23.

- Reference Yang1985

Cypridea tera; Yang, p. 219, pl. 4, fig. 20.

- Reference Qi1988

Mongolocypris tera; Qi, p. 111, pl. 6, figs. 9–12.

- Reference Ye1994

Mongolocypris tera; Ye, p. 179, figs. 10B, 11B.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Mongolocypris tera; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 529, pl. 236, figs. 5, 6.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Mongolocypris porrecta; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 528, pl. 235, figs. 7, 8.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Mongolocypris tera; Ye et al., p. 179, pl. 23, fig. 3a–c.

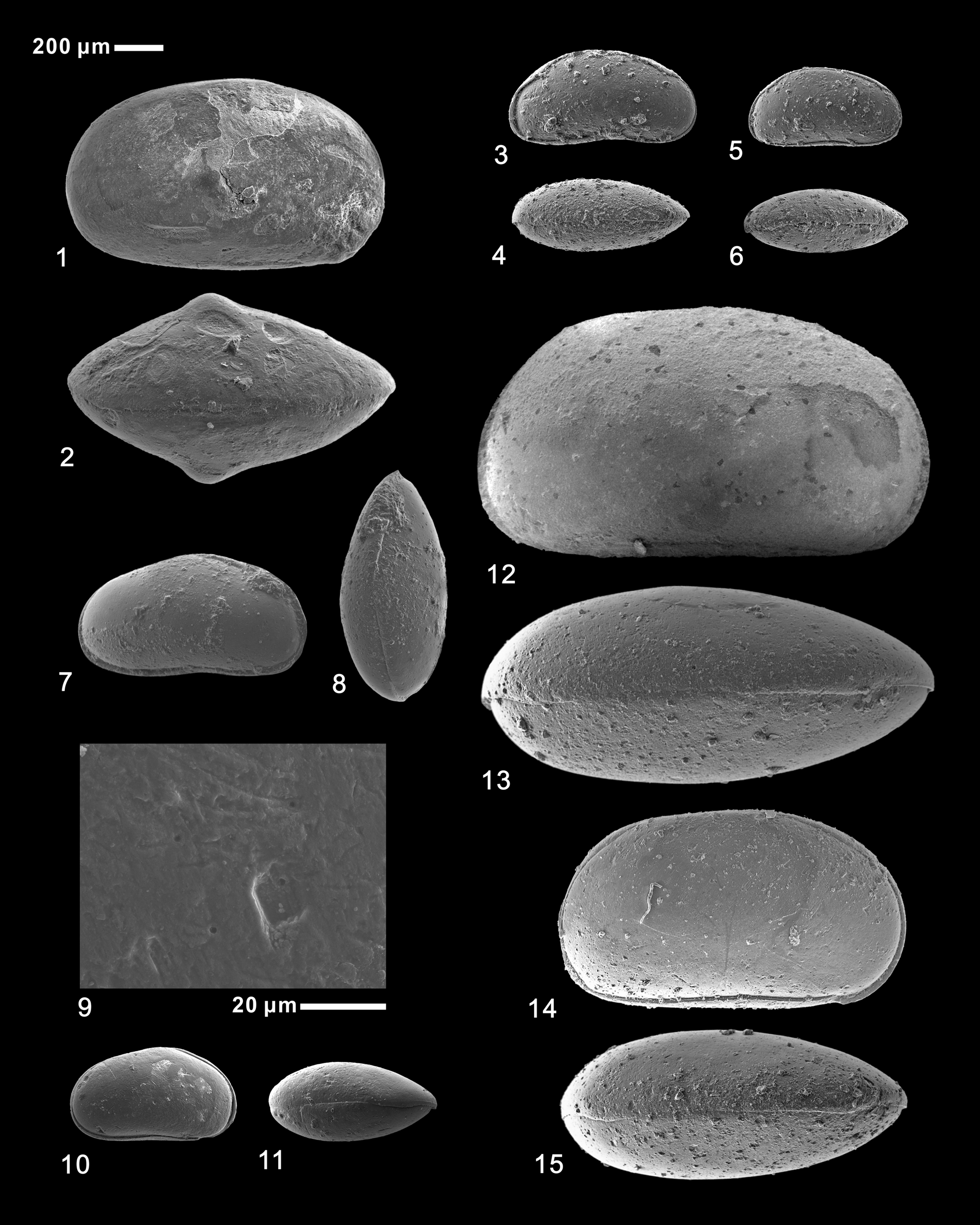

Figure 7. Photomicrographs of ostracode species recovered from the ZKY2-1 well, Songliao Basin, northeastern China. (1–3) Mongolocypris tera (Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959): adult carapace (ZKY.O 30): (1) right view, (2) left view, and (3) dorsal view. (4–7) Talicypridea obliquecostae (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970): (4, 6) adult carapace (ZKY.O 08): (4) right view and (6) detail of anterior zone with the rostrum-like process; (5, 7) adult carapace (ZKY.O 09): (5) dorsal view and (7) detail of the porecanals in posterior zone. (8–13) Talicypridea reticulata (Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978): (8–10) adult carapace (ZKY.O 10): (8) right view, (9) left view, and (10) dorsal view; (11–13) A-1 carapace (ZKY.O 11): (11) right view, (12) dorsal view, and (13) detail of the small tubercles with porecanal in posterior zone. (14–17) Renicypris renalata (Su in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974): (14) adult left valve (ZKY.O 14), left view; (15–17) adult carapace (ZKY.O 15): (15) left view, (16) dorsal view, and (17) detail of the ornamentation. (1–5, 8–12, 14–16) Scale bars = 200 μm; (6, 7, 13, 17) scale bars = 20 μm.

Holotype

A carapace (IGA. 159) from the Upper Cretaceous Yaojia Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

China: Jilin Province, Gongzhuling City, and counties of Changling and Qian'an, the Yaojia, Nenjiang, and Sifangtai formations; Heilongjian Province, cities of Duboerte and Anda, the Qingshankou and Yaojia formations; Songliao Basin, Upper Cretaceous (Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Xi et al., Reference Xi, Wan, Feng, Li, Feng, Jia, Jing and Si2011; Wan et al., Reference Wan, Zhao, Scott, Wang, Feng, Huang and Xi2013); Guangxi Province, Rong County, Upper Cretaceous (Guan, Reference Guan1978). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation, lower Santonian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

Sixty-six carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-93 samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 1.638–2.133 mm and height = 0.859–1.193 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Netchaeva et al. (Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959). Due to major morphological similarity between Mongolocypris tera (Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959) and Mongolocypris porrecta (Su in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959—which were also described from the Nenjiang Formation—we decided to include Mongolocypris porrecta in the synonymic list of Mongolocypris tera, since the latter's scientific name has priority over the former's.

Family Candonidae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900

Subfamily Candoninae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900

Genus Fabaeformiscandona? Krstič, Reference Krstič1972

Type species

Cypris fabaeformis Fischer, Reference Fischer1851.

Remarks

The species of Fabaeformiscandona are widely distributed throughout the Late Cenozoic and recent deposits. Most of them are identified on the basis of their anatomical characters (e.g., the number of setae on the protopod of the cleaning leg). For the fossil record, however, it is pratical to use shell morphological characteristics (e.g., well-developed posterodorsal lobe-like expansion of the left valve overlapping the right one, greatest height about half of the length, narrow inner lamella, and short but not thin pore canals) to distinguish them from other genera of Candoninae Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann1900 (Krstič, Reference Krstič1972).

Fabaeformiscandona? disjuncta (Hao in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974), emend.

Figure 6.3–6.6

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Candona disjuncta Hao in Hao et al., p. 69, pl. 26, fig. 5.

- 1976

Candona disjuncta; DOFEAD, p. 84, pl. 33, fig. 7.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Candona disjuncta; Ye et al., p. 241, pl. 62, fig. 3a–g.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Candona disjuncta; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 290, pl. 65, fig. 11, pl. 66, figs. 1–5.

- Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014

Candona disjuncta; Qu et al., p. 792, fig. 6.17.

- Reference Wang2019

Candona disjuncta; Wang et al., p. 11, fig. 7G.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 317) from the Upper Cretaceous Nenjiang Formation, Songliao Basin, China (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Occurrence

China: Heilongjiang Province, Daqing City, and Jilin Province, cities of Fuyu and Shuangliao and Changling County; Songliao Basin, Nenjiang Formation; Da'an City, Sifangtai and Mingshui formations, Upper Cretaceous (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; DOFEAD, 1976; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Zhang, Cao and Horne2019). In the present work, Member 1 of the Nenjiang Formation, lower–middle Santonian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Description (emended)

Nearly reniform carapace in lateral view and ovoid in dorsal view, with greatest length at the centroventral region and greatest height at the posterocentral region, which is nearly half of the length. Left valve larger than the right, with a well-developed elongated lobe-like expansion at posterodorsal and anterodorsal areas overlapping the latter one. Rounded, infracurvate anterior and posterior ends, the latter broader than the former. Convex dorsal margin, inclining more pronouncedly toward the anterior end. Convex ventral margin, but more strongly convex in the right valve. Anterior cardinal angle rounded and inconspicuous, curved at about 153°; posterior cardinal angle curved at about 130°. Smooth lateral surface, with porecanals throughout. Sexual dimorphism is present as follows: female individuals with shorter and more inflated carapace, with a broader posterior end and straighter ventral margin in the left valve compared with males.

Materials

Eighty-three carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-87 (16), ZKY2-1-92 (49), and ZKY2-1-93 (18) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 0.644–0.728 mm and height = 0.331–0.370 mm.

Remarks

The specific diagnosis follows Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974). Note that neither fossil records nor genetic divergence (Karanovic and Sitnikova, Reference Karanovic and Sitnikova2017) suggest the occurrence of Fabaeformiscandona Krstič, Reference Krstič1972 in the Upper Cretaceous. Karanovic and Sitnikova (Reference Karanovic and Sitnikova2017) indicated that the fossil record of the candonids from the Upper Cretaceous could be constituted by genera that were ancestors of the recent ones. From the fossil perspective, however, the major diagnostic characters, such as posterodorsal lobe-like expansion and length/height ratios, contribute to the studied species’ tentative placement in the genus Fabaeformiscandona. The authors opted to establish a new description for Fabaeformiscandona? disjuncta (Hao in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974) based on the unprecedented identification of sexual dimorphism in the species as well as the presence of the lobe-like expansion at posterodorsal and anterodorsal areas.

Family Cyprididae Baird, Reference Baird1845

Subfamily Eucypridinae Bronstein, Reference Bronstein [Bronshteyn]1947

Genus Lycopterocypris Mandelstam, Reference Mandelstam and Schneider1956

Type species

Cypris faba Egger, Reference Egger1910.

Lycopterocypris profunda Lübimova, Reference Lübimova1956

Figure 6.7–6.11

- Reference Lübimova1956

Lycopterocypris profunda Lübimova, p. 113, pl. 22, figs. 5a, 6.

- 1976

Lycopterocypris grandis Ye in DOFEAD, p. 74, pl. 29, figs. 2a, b, 3, 4.

- 1976

Lycopterocypris typicalis Ding in DOFEAD, p. 76, pl. 30, figs. 1a, b, 2a, b.

- 1976

Lycopterocypris pyriformis Ye in DOFEAD, p. 80, pl. 31, fig. 8a, b.

- ?Reference Szczechura1978

Lycopterocypris cf. L. profunda; Szczechura, p. 103, pl. 32, figs. 1, 2, pl. 36, fig. 7.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Lycopterocypris grandis; Ye et al., p. 217, pl. 49, fig. 2a–d.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Lycopterocypris typicalis; Ye et al., p. 218, pl. 49, fig. 4a–d.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Eucypris profunda; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 139, pl. 6, figs. 19–21.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Eucypris typicalis; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 145, pl. 8, figs. 13–16.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 271-17) from the Upper Cretaceous Sainshand Suite, Mongolia (Lübimova, Reference Lübimova1956), housed in the collections of the All-Russia Petroleum Research Exploration Institute (originally, the All-Union Petroleum Research and Geological-Prospecting Institute), Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Occurrence

Mongolia: Dornogovi Province, Gobi Desert; Sainshand Suite, Upper Cretaceous (Lübimova, Reference Lübimova1956). China: Nei Mongol Province, Erlianhaote City, Erliandabusu Formation; Heilongjiang Province, Anda City and Taikang County, Qingshankou Formation, Lower Cretaceous (DOFEAD, 1976; Hou at el., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002; Ye at el., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Sifangtai Formation, middle–upper Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

Fifty-five carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-17 (4), ZKY2-1-22 (27), ZKY2-1-27 (17), ZKY2-1-34 (2), ZKY2-1-49 (2), and ZKY2-1-49 (3) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length 0.667–0.914 mm and height 0.368–0.481mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Lübimova (Reference Lübimova1956). Three species, Lycopterocypris grandis Ye in DOFEAD, 1976, Lycopterocypris pyriformis Ye in DOFEAD, 1976, and Lycopterocypris typicalis Ding in DOFEAD, 1976, from Member 2 of the Qingshankou Formation, share with Lycopterocypris profunda Lübimova, Reference Lübimova1956 the general outline of the carapace and height/length ratio, which led the authors to place them in the synonymic list of Lycopterocypris profunda. Individuals of Lycopterocypris pyriformis present a carapace that is smaller and less convex in dorsal view and are considered respresentatives of a juvenile instar of Lycopterocypris profunda.

Subfamily Cyprinotinae? Bronstein, Reference Bronstein [Bronshteyn]1947

Genus Renicypris Ye in Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Type species

Cypridea parvita Ding in DOFEAD, 1976.

Remarks

The Genus Renicypris was erected by Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002), but because no internal features were observable so far in any species of Renicypris, it has not been placed in a family by previous works. On the basis of external features, such as its highly conspicuous valve ornamentation (a tightly packed tecellation of small pustules, reminiscent of the negative of a reticulation), Renicypris might be related to the genus Harbinia Tsao in Netchaeva et al., Reference Netchaeva, Liu, Su, Shou, Tian and Zhao1959 just as Kroemmelbeincypris Poropat and Colin, Reference Poropat and Colin2012b, although Harbinia and Renicypris lack the plicated lip observed in some species that could be attributed to Kroemmelbeincypris (such as Harbinia alta Antonietto et al., Reference Antonietto, Gobbo, Do Carmo, Assine, Fernandes and Silva2012). Following these assumptions, we place Renicypris tentatively (as was previously done to the morphologically similar Kroemmelbeincypris) in the subfamily Cyprinotinae Bronstein, Reference Bronstein [Bronshteyn]1947.

Renicypris renalata (Su in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974), emend.

Figure 7.14–7.17

- Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974

Cypridea? renalata Su in Hao et al., p. 43, pl. 14, fig. 5a–h.

- 1976

Cypridea parvita Ding in DOFEAD, p. 58, pl. 18, figs. 12a, b, 20a, b.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

G. indet. sp. indet.; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 523, pl. 211, figs. 28–37.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Quadracypris? parvita; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 578, pl. 226, figs. 31–34.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Renicypris parvita; Ye et al., p. 189, pl. 30, fig. 1a–c.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Renicypris renalata; Ye et al., p. 191, pl. 30, fig. 7a–d.

Holotype

A carapace (no. 256) from the Upper Cretaceous Sifangtai Formation, China (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974), housed at the Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing, China.

Diagnosis (emended)

A species of Renicypris distinguished by the following features: equicurvate to slightly supracurvate posterior margin and lateral surface ornamented with a tightly packed tecellation of small pustules, reminiscent of the negative of a reticulation, that turns into smooth surface in the anterior end and the posteroventral margin.

Occurrence

China, Upper Cretaceous, Songliao Basin: Jilin Province, Kailu County, Yaojia and Fulongquan formations, and Baicheng City, Sifangtai Formation (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974; Hou et al., Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002); Heilongjiang Province, Daqing City, Sifangtai Formation (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002). In the present work, Sifangtai Formation, middle–upper Campanian, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Description (emended)

Medium-sized, subreniform carapace in lateral view, with its greatest length at the central region and greatest height at the centroanterior region. Left valve larger than the right, overlapping it along the anterior end. Subrounded, slightly infracurvate anterior end. Equicurvate to slightly supracurvate posterior end. Rounded, obtuse anterior cardinal angle at about 160°; obtuse posterior cardinal angle at about 134°. Subconcave dorsal margin, inclined toward the posterior end at about 14°. Concave ventral margin, with its highest concavity at the oral region. Lateral surface ornamented with a tightly packed tecellation of small pustules, reminiscent of the negative of a reticulation, that turns into smooth surface in the anterior end and the posteroventral margin. In dorsal view, elliptical, with its greatest width at the posterocentral region, and gently tapering toward the anterior end.

Materials

Twenty-seven carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-25 (7), ZKY2-1-26 (6), ZKY2-1-28 (1), ZKY2-1-30 (2), and ZKY2-1-32 (11) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 0.594–0.654 mm and height = 0.368–0.406 mm.

Remarks

The identification follows Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002) due to the informal illustration of species in the original proposal by Su (in Hao et al., Reference Hao, Su, Li, Ruan and Yuan1974). However, the emendment of the species proposed by Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002) provided a very short and undetailed description and did not establish a diagnosis for it. Because the species is well preserved with unique ornamentation of small pustules and slightly supracurvate posterior margin, the present authors opted to redescribe the diagnosis and description. Specimens of Renicypris parvita (Ding in DOFEAD, 1976) and Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002) share almost all morphological traits with specimens described herein and therefore are included in the present synonymic list.

Subfamily Talicyprideinae Hou, Reference Hou1982

Genus Talicypridea Khand, Reference Khand1977

Type species

Cypridea biformata Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970.

Talicypridea obliquecostae (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970)

Figure 7.4–7.7

- Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970

Cypridea obliquecostae Szczechura and Błaszyk, p. 111, pl. 29, fig. 5a–c.

- Reference Szczechura1978

Nemegtia obliquecostae; Szczechura, p. 98, pl. 27, figs. 1–7, pl. 37, fig. 5.

- Reference Ye and Zhang1989

Talicypridea qingyuangangensis Ye in Ye and Zhang, p. 25, pl. 2, figs. 3, 4.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Talicypridea qingyuangangensis Ye in Ye et al., p. 185, pl. 27, fig. 4a, b.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Liu, Zhang and Chen2003

Talicypridea qingyuangangensis; Ye et al., p. 85, pl. 13, figs. 1a–c, 3, 4.

- Reference Liu, Huang and Ye2004

Talicypridea qingyuangangensis; Liu, Wang, and Ye, p. 313, pl. 1, fig. 9a, b.

- Reference Horne and Colin2005

Talicypridea obliquecostae; Horne and Colin, p. 30, pl. 2, figs. 7–9.

- ?Reference Khand, Sames and Schudack2007

Talicypridea neustruevae Khand, Sames, and Schudack, p. 74, pl. 1, figs. E, F.

- Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014

Talicypridea qingyuangangensis; Qu et al., p. 792, fig. 6.1.

- Reference Wang2019

Talicypridea obliquecostae; Wang et al., p. 9, fig. 6A–F.

Holotype

A carapace (Z. Pal. no. MgO/4) from the Upper Cretaceous, Nemegt Formation, Mongolia (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978), housed in the collections of the Institute of Paleobiology (originally, the Palaeozoological Institute) of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland.

Occurrence

Mongolia: Ömnögovi Province, Gobi Desert, Nemegt and Altan (“Ula IV”) mountains, Nemegt Basin, Nemegt Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970; Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978). China: Heilongjiang Province, Daqing City, Sifangtai and Mingshui formations, Upper Cretaceous (Ye at el., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002); Inner Mongolia, Hulun Buir City, Hailaer Basin, Qingyuangang Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Ye at el., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2003; Liu at el., Reference Liu, Huang and Ye2004); Shandong Province, Zhucheng City, Jiankou village, Jiaozhou Formation, upper Campanian–lower Maastrichtian (Wang at el., Reference Wang2019). In the present work, Sifangtai Formation, middle–upper Campanian, Upper Cretaceous, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Materials

Fifty-four carapaces recovered from the ZKY2-1-20 (16), ZKY2-1-22 (5), ZKY2-1-24 (21), ZKY2-1-27 (8), ZKY2-1-39 (1), and ZKY2-1-41 (3) samples, ZKY2-1 well, Qianjiadian Town, Tongliao City, Inner Mongolia, northeastern China.

Measurements

Length = 0.674–0.725 mm and height = 0.403–0.458 mm.

Remarks

Talicypridea obliquecostae (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970) has a rather complicated taxonomic history. Szczechura and Błaszyk (Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970) initially attributed this species to the genus Cypridea; due to lack of typical Cypridea morphological characters, such as beak, alveolus, and cyathus, Szczechura (Reference Szczechura1978) reassigned it to Nemegtia Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978. However, the description provided by that work for Nemegtia renders it virtually identical to a previously created genus, Talicypridea Khand, Reference Khand1977—which has been previously noted by Horne and Colin (Reference Horne and Colin2005) and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Li, Zhang, Cao and Horne2019) but never discussed on taxonomic remarks before. Talicypridea obliquecostae closely resembles Talicypridea neustruevae Khand, Sames, and Schudack, Reference Khand, Sames and Schudack2007, but the latter has a more ovate outline in lateral view, weakly developed spines on the lip, and a unique wavy ornamentation (these ornamentation elements were considered by Sames [Reference Sames2011c] of lower taxonomic significance, however). On that basis, Talicypridea neustruevae is included in the present synonymic list with reservations. Talicypridea qingyuangangensis Ye in Ye and Zhang, Reference Ye and Zhang1989 (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002, Reference Ye, Huang, Liu, Zhang and Chen2003; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Huang and Ye2004; Qu et al., Reference Qu, Xi, Li, Colin, Huang and Wan2014), however, displays all the diagnostic features of Talicypridea obliquecostae and is herein synonymized with Talicypridea obliquecostae.

Talicypridea reticulata (Szczechura, Reference Szczechura1978)

Figure 7.8–7.13

- Reference Hou and Chen1962

Cypridea amoena Liu in Hou and Chen, p. 68, pl. 14, fig. 5a, b.

- Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970

Cypridea sp. 1; Szczechura and Błaszyk, p. 112, pl. 28, fig. 4a–c.

- 1976

Cypridea amoena Liu in DOFEAD, p. 57, pl. 18, figs. 11a, b, 14a, b, 15a, b, 16, 17.

- Reference Szczechura1978

Nemegtia reticulata Szczechura, p. 96, pl. 26, figs. 1–7, pl. 37, figs. 4, 7A, B, 8B.

- Reference Hou, Ho and Ye1978

Cristocypridea reticulata; Hou et al., p. 178, pl. 15, figs. 15–23, 39–42.

- Reference Hou, Ho and Ye1978

Cristocypridea latiovata; Hou et al., p. 179, pl. 15, figs. 30–35.

- Reference Gou, Cao and Ye1978

Cristocypridea reticulata; Gou et al., p. 56, pl. 3, figs. 11, 12.

- Reference Hou1982

Cristocypridea aff. C. biformata (Szczechura and Błaszyk, Reference Szczechura and Błaszyk1970); Hou et al., p. 148, pl. 60, figs. 10–24.

- Reference Ye1982

Cristocypridea latiovata; Ye, p. 167, pl. 3, figs. 20–22.

- Reference Hao, Ruan, Zhou, Song, Yang, Cheng and Wei1983

Talicypridea reticulata; Hao et al., p. 105, pl. 19, figs. 4, 5.

- Reference Hao, Ruan, Zhou, Song, Yang, Cheng and Wei1983

Talicypridea latiovata Hao et al., p. 102, pl. 18, figs. 13–15.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Talicypridea reticulata; Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 543, pl. 213, figs. 12, 13.

- Reference Hou, Gou and Chen2002

Rhombicypridea latiovata (Hou in Hou et al., Reference Hou, Ho and Ye1978); Hou, Gou, and Chen, p. 554, pl. 218, figs. 6, 7.

- Reference Ye, Huang, Zhang and Chen2002

Talicypridea amoena; Ye et al., p. 187, pl. 28, fig. 1a–f.

- Reference Wang2019

Talicypridea reticulata; Wang et al., p. 11, fig. 6G–X.

Holotype