Introduction

The trilobite genus Liostracina Monke, Reference Monke1903, holds an important place in Cambrian stratigraphy and trilobite systematics. Liostracina has a relatively short stratigraphic range through the upper part of the Miaolingian Series (Guzhangian Stage). In South China, Liostracina bella Lin and Zhou in Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin and Zhou1983, serves as the eponymic species for the Liostracina bella Zone of polymerid trilobite zonation, which is equivalent to the lower part of the Linguagnostus reconditus Zone through the Glyptagnostus reticulatus Zone of agnostoid zonation (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004b). Liostracina bella, however, does not range through the entire zone; it ranges as high as the Glyptagnostus stolidotus Zone of agnostoid zonation (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a, Reference Peng, Babcock and Linb), having its last known appearance a few meters below the base of the Furongian Series (Paibian Stage). The first appearance of the agnostoid trilobite G. reticulatus is the primary chronostratigraphic marker for the base of the Paibian Series, but L. bella and congeneric species serve as important secondary chronostratigraphic guides for the uppermost Miaolingian and the Miaolingian-Furongian boundary interval (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a, Reference Peng, Babcock and Linb, Reference Peng, Babcock, Robison, Lin, Rees and Saltzmanc). In terms of systematics and its phylogenetics, Liostracina provided crucial evidence for transferring the superfamily Trinucleoidea to the order Asaphida (Fortey and Chatterton, Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988).

Liostracina was erected by Monke (Reference Monke1903) on the basis of disarticulated cranidia, librigenae, and pygidia from the Kushan Formation (Cambrian) in Shandong Province, North China, with Liostracina krausei Monke, Reference Monke1903, as type species. Monke's original material is presumed to be lost. Subsequently, species of Liostracina were reported from a wide range of East Gondwanan localities, including a variety of provinces in northern, northeastern, and southern China (Liaoning, Qinghai, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Henan, Jiangsu, Anhui, and Hunan), plus South Korea, Australia, and Antarctica (Walcott, Reference Walcott1913; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935, Reference Kobayashi1962; Resser and Endo, Reference Resser, Endo, Endo and Resser1937; Endo, Reference Endo1944; Zhu, Reference Zhu1959, Reference Zhu1960; Egorova et al., Reference Egorova, Xiang, Li, Nan and Guo1963; Öpik, Reference Öpik1967; Nan, Reference Nan1980; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin and Zhou1983; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983; Zhang and Wang, Reference Zhang and Wang1985; Zhang and Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu1986; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xiang, Liu and Meng1995; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a; Jago and Cooper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007; Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011; Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018). Except for a single, enrolled degree 2 meraspis from the Sesong Formation of South Korea (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011) and some protaspides from the Kushan Formation of Shandong, North China (Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014), all previously illustrated material consists of disarticulated sclerites. All assigned species are late Guzhangian in age.

The generic concept of Liostracina has been discussed by numerous authors (e.g., Walcott, Reference Walcott1913; Raymond, Reference Raymond1937; Resser and Endo, Reference Resser, Endo, Endo and Resser1937; Endo, Reference Endo1944; Howell in Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Henningsmoen, Howell, Jaanusson, Lochman-Balk and Moore1959; Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1962; Öpik, Reference Öpik1967; Zhang and Jell, Reference Zhang and Jell1987; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Jago and Begg1996; Jago and Cooper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007; Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014), resulting in a detailed understanding of the dorsal morphologies of the cephalon and pygidium and the stratigraphic occurrence for the genus. However, its ventral characters have, until now, remained incompletely known. The thoracic morphology in the holaspid period has remained completely unknown also until now.

This paper documents a new species, Liostracina fuluensis n. sp., from the Cambrian (Miaolingian; Guzhangian in southeastern Yunnan, South China). The studied material comprises a large collection of specimens that collectively illustrate the entire dorsal and ventral exoskeletal morphology of holaspids. This new material allows a more complete understanding of the generic concept. Importantly, it serves to clarify our understanding of the ventral cephalic morphology. This leads us to reassign the genus Liostracina and the family Liostracinidae from the order Asaphida sensu Fortey (Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997) or the order Trinucleida sensu Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) to Ptychopariida, where it had been classified for many years previously. New material shows that a holaspid Liostracina has a rostral suture and a pair of connective sutures defining a narrow rostral plate; a natant hypostomal condition; eight segments in the thorax, with the first four segments each having a facet and c-shaped doublure, and the remaining segments having short bar-shaped doublures; and a linear doublure on the pygidium.

Geologic setting

Fossils reported here were collected from exposures of the middle member of the Longha Formation on the north side of rural highway Y028, ~1 km northwest of Fulu Village (Fig. 1.4) and ~15 km southeast of Tianpeng Township, Funing County, southeastern Yunnan Province, South China (Fig. 1). The Tianpeng-Fulu area is home to a number of stratotype sections for named Cambrian lithostratigraphic units. In ascending order, they are the Tianpeng, Longha, Tangjiaba, and Bocaitian formations (Fig. 1.4, 1.5). Locally, Cambrian strata are unconformably overlain by a Devonian succession, the Yujiang and Ping'en formations (Fig. 1.4).

Figure 1. (1–4), Maps showing the locations of some exceptionally preserved Cambrian biotas in southeastern Yunnan and northwestern Guangxi provinces, South China (1–3), including Fulu Village, where the studied material was collected; and the geology of Fulu area, Tianpeng, Funing, southeastern Yunnan (4). (5), Stratigraphic column for the Longha Formation in the Xiaozhai-Renjia-Fulu area, Yunnan, showing position of the Fulu biota and occurrence of the new species Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. TP Fm = Tianpeng Formation, TJB Fm = Tangjiaba Formation.

In addition to specimens of Liostracina fuluensis n. sp., the Longha Formation at the Fulu Village locality yields other polymerid trilobites, agnostoid trilobites, echinoderms, brachiopods, large bivalved arthropods, bradoriids, priapulid worms, hyoliths, macroalgae, and trace fossils. This assemblage, the Fulu Biota, was recently reported by Peng et al. (Reference Peng, Yang, Liu, Zhu, Sun, Zamora, Mao and Zhang2020). Trilobites of the Fulu Biota at Fulu Village are commonly found as articulated exoskeletons. Co-occurring polymerid trilobites include Bergeronites sp., Blackwelderia sp., Damesops sp., Monkaspis sp., Paracoosia asiatica (Mansuy, Reference Mansuy1916), Palaeadotes hunanensis (Yang in Zhou and Liu, Reference Zhou and Liu1977), Teinistion sp., Torifera, and an undetermined shumardiid. Co-occurring agnostoids include Agnostus sp., Ammagnostus wangcunensis Peng and Robison, Reference Peng and Robison2000, Clavagnostus spinosus (Resser, Reference Resser1938), Hadragnostus modestus (Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944), and Kormagnostus minutus (Schrank, Reference Schrank1975). The agnostoid assemblage is indicative of the upper Proagnostus bulbus to lower Linguagnostus reconditus zones (Guzhangian Stage).

Materials and methods

Materials

All studied specimens were collected from a 2.5-m-thick interval low in the middle member of the Cambrian Longha Formation of the Fulu section, Yunnan. At this locality, the rock is mainly a dark marlstone that weathers into brownish yellow mudstone or shale. The interval is divided into eight subintervals, each ~30 cm in thickness. More than 200 specimens were available for this study, including 57 complete exoskeletons, among which two are enrolled, 17 are incomplete exoskeletons (12 cephala or cranidia plus complete or partial thoraxes, and five thoracopygons), 22 cephala, 102 cranidia, eight librigenae, and three pygidia. Studied specimens are preserved in pelitic rock that has been subjected to tectonic deformation (Figs. 2.2, 2.6, 3.12, 3.13). Post-burial deformation, however, has been minor for most specimens (see information on retrodeformation under “Methods”).

Methods

Specimens were photographed under a Zeiss stereomicroscope (Model Axio Zoom V16) having a digital head (AxioCamMrM) and a circle light around the lens providing uniform lighting. Sometimes an additional light was added to provide directional lighting from the upper left. Because of shale preservation, most specimens were photographed in color to avoid permanent contamination by inking. Some specimens were photographed a second time, after first being pigmented with black ink and coated with a light dusting of magnesium oxide. Photographs made from counterpart slabs (external molds of the trilobite fossils) were produced by making black (ink-infused) latex molds and coating then with a light dusting of magnesium oxide. Images were processed using automatic color, contrast, and tonality functions in Adobe Photoshop CS6 software. The illustration of a cephalon in Figure 3.9, which was originally black in color, was changed to brown using a color-balance function. Images of some specimens in Figures 2 and 3 were retrodeformed by using a free-deformation function of the Photoshop software (for principle and technique, see Hughes, Reference Hughes and Harper1999). Retrodeformation in all instances has been minor, as indicated by retrodeformation ellipses accompanying each of the altered images.

Figure 2. Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. from the Longha Formation, Guzhangian, Fulu area, southeastern Yunnan; white arrowhead indicates the posterior margin of thorax; abbreviations: e, eye; es, eye socle; pd, pygidial doublure; pl, palpebral lobe; td, thoracic doublure. (1, 2, 4–8) ventral views; (3, 9–13) dorsal views; (1), NIGP 173732, external mold of degree 7 meraspid exoskeleton; (2, 3) NIGP 173733, degree 7 meraspid exoskeleton, external mold and latex cast, retrodeformation with inferred strain ellipse; (4–6, 9) NIGP173734, 173735, 173736, external mold of holaspid exoskeleton, (9) is latex cast of (6), retrodeformation with inferred strain ellipse; (7, 10, 13) NIGP 173737, external mold of holaspid exoskeleton lacking lateral and anterior cephalic borders, (10) is latex cast of (7), retrodeformation with inferred strain ellipse, (13) is partial enlargement of (10), note the eye is possibly preserved; (8, 11) NIGP 173738, external mold and latex cast of holaspid exoskeleton with partly preserved lateral and anterior border; (12) NIGP 173739, loosely enrolled holaspid exoskeleton, inferred to be postmortem folding. All scale bars represent 2 mm.

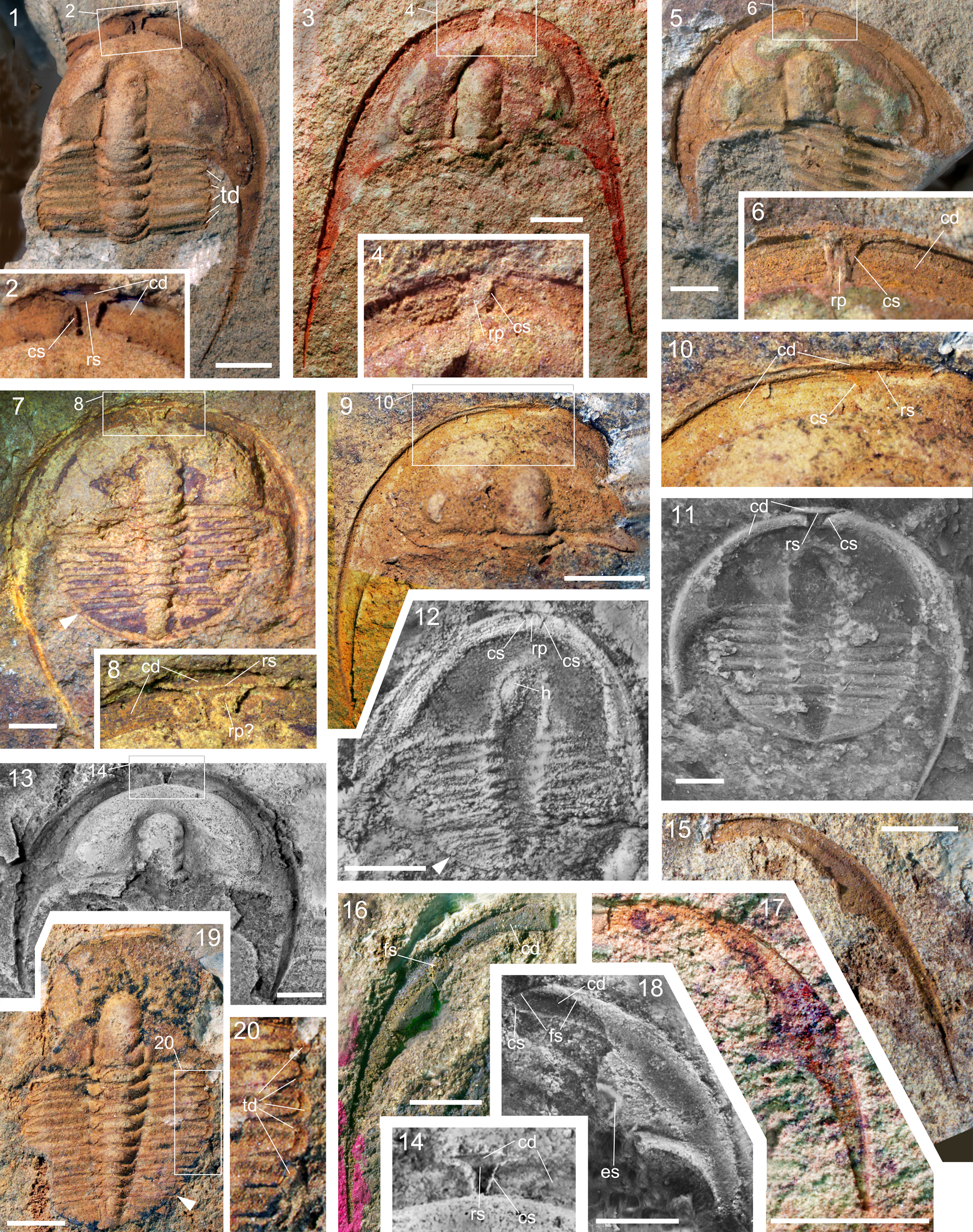

Figure 3. Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. from the Longha Formation, Guzhangian, Fulu area, southeastern Yunnan; white arrowhead indicates posterior margin of thorax; abbreviations: cd, cephalic doublure; e, eye; es, eye socle; f, facet; pl, palpebral lobe; td, thoracic doublure; (1, 2) ventral views; (3, 4, 8–13) dorsal views; (5–7) lateral, anterior, and anterolateral views; (1, 4–8) NIGP 173740, external mold of holaspid exoskeleton (1) and latex cast (4–8), retrodeformation with inferred strain ellipse; (8) is partial enlargement of the thoracic pleural tips (1), showing differentiation of the anterior and posterior sections; (2, 3) holotype NIGP 171341, external mold of holaspid exoskeleton and latex cast; (9) NIGP 173741, latex cast of cephalon lacking left librigena, retrodeformation with inferred strain ellipse; note the long baccula; (10, 11) NIGP 173742, incomplete exoskeleton lacking pygidium and having a broken cephalon; (11) is partial enlargement of (10), showing possible visual surface of holochroal eye with small, closely spaced lenses; (12, 13) NIGP 173743, 173744, cranidia, showing post-burial deformation by vertical and transverse compression, respectively; note each has a short baccula; (14) NIGP 173745, pygidium. All scale bars represent 2 mm.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All illustrated specimens are deposited in the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Nanjing, China, and prefixed NIGP.

Systematic paleontology

Terminology

Morphologic terminology generally follows that of Whittington and Kelly (Reference Whittington, Kelly and Kaesler1997). Use of “glabella” here excludes the occipital ring. “Long” and “short” are used with reference to longitudinal (sagittal, sag., and exsagittal, exs.) dimensions, and “broad” (or “wide”) and “narrow” are used with reference to transverse (tr.) dimensions (see Whittington, Reference Whittington and Kaesler1997, p. O2).

Class Trilobita Walch, Reference Walch1771

Order Ptychopariida Swinnerton, Reference Swinnerton1915

Suborder Ptychopariina Richter, Reference Richter, Dittler, Joos, Korschelt, Linek, Oltmanns and Schaum1933

Superfamily Liostracinoidea Raymond, Reference Raymond1937

Family Liostracinidae Raymond, Reference Raymond1937

Type genus

Liostracina Monke, Reference Monke1903.

Diagnosis

Ptychopariid trilobite having parallel-sided or forward-tapering glabella; small, posteriorly placed palpebral lobes; strongly convex fixigena; variably expressed median furrow in preglabellar area; bacculae variably sized or absent; and opisthoparian facial suture; ventral cephalon has submarginal rostral suture, rostral plate with closely or widely spaced connective sutures; natant hypostomal condition.

Remarks

The diagnosis of Howell (in Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Henningsmoen, Howell, Jaanusson, Lochman-Balk and Moore1959) is emended here to include newer information, especially information reported herein. Howell (Reference Howell, Harrington, Henningsmoen, Howell, Jaanusson, Lochman-Balk and Moore1959) included the family Liostracinidae Raymond, Reference Raymond1937, together with the family Emmrichellidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935, in the superfamily Emmrichellacea Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935 (order Ptychopariida Swinnerton, Reference Swinnerton1915). The concept of the family Liostracinidae was discussed in detail by Öpik (Reference Öpik1967). Öpik (Reference Öpik1967) included the trilobite family Liostracinidae in the suborder Ptychopariina. He also proposed the superfamily Liostracinoidea, embracing only the family Liostracinidae. On the basis of the dorsal morphology and newly ascertained ventral features of Liostracina, and on the presence of a connective suture and rostral plate in Doremataspis (which is also assigned to the family Liostracinidae), Öpik's (Reference Öpik1967) assignment is followed here.

Fortey and Chatterton (Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988) referred the Liostracinidae to the superfamily Trinucleoidea, which was then classified in the suborder Asaphina. The Asaphina was elevated to order level, as the order Asaphida, by Fortey (Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997), and this assignment was followed by Adrain (Reference Adrain and Zhang2011). As discussed below, assignment of the Liostracinidae to the Asaphida implies the presence of a ventral median suture in Liostracina, the type genus, however new evidence presented here shows that Liostracina lacks that character. Instead, the presence of a rostral plate and natant hypostomal attachment in Liostracina prompts assignment to the order Ptychopariida, which is essentially the same as Öpik's (Reference Öpik1967) suggestion.

Differences of opinion exist on whether to recognize the Ptychopariida as a formal taxonomic entity. Adrain (Reference Adrain and Zhang2011), for example, argued for abandoning use of the terms order Ptychopariida, suborder Ptychopariina, and superfamily Ptychoparioidea, because he considered these taxa to be polyphyletic. In so doing, he assigned 58 families to an order Uncertain (Incertae Ordinis). Most of the families assigned to an uncertain order were previously included in the order Ptychopariida. Lieberman and Karim (Reference Lieberman and Karim2010) and Paterson (Reference Paterson2020) likewise questioned the practicality of recognizing the order Ptychopariida. Alternatively, Yuan et al. (Reference Yuan, Li, Mu, Lin and Zhu2012, Reference Yuan, Zhang and Zhu2016), Laibl et al. (Reference Laibl, Fatka, Crônier and Budil2014), Esteve (Reference Esteve2015), Krylov (Reference Krylov2018), and Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020), among others, recently have argued for continued recognition of the order Ptychopariida. Bignon et al. (2020, p. 1062) noted the “Ptychopariida still exists as an order even if it only includes the genus Ptychoparia, unless it can be demonstrated conclusively that it is a junior synonym of another order.”

Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) elevated Trinucleoidea to ordinal status. They included the family Liostracinidae in the order Trinucleida, as they construed it, and the results of their cladistic analysis showed that the liostracinids are the sister group to all other trinucleoids. That cladistic work supports a common ancestry for trinucleoids and some ptychopariids that lie outside the Asaphida. The topology of their strict consensus tree shows the Liostracinidae in a position between more-basal Ptychopariida and more-derived Trinucleida, indicating that the trinucleids also share a close relationship with ptychopariids.

As information presented here now shows, inclusion of the Liostracinidae in the concept of Trinucleida as construed by Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) is unacceptable because some important characters, ones characteristic of ptychopariids (e.g., the presence of a median preglabellar furrow, a ventral assembly comprising a rostral suture, a rostral plate, and a natant hypostome), were not coded into the data set. In addition, some characters considered synapomorphies of ptychopariids are now recognized as present in Liostracina. These characters, which include the absence of a ventral median suture, a non-asaphoid-type protaspis, a glabellar node situated on the occipital ring, and a parallel-sided anterior section of the facial suture, were interpreted as features of early trinucleids by Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020). Unambiguous trinucleids, such as dionids, raphiophorids, and trinucleids, lack these characters. The median preglabellar furrow is known in some ptychopariids (e.g., Xilingxia Lu in Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lu, Zhu, Qian, Lin, Zhou, Zhang and Yuan1980; Paleonelsonia sulcata Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Zhu2016), and a parallel-sided anterior section of the facial suture is known in a number of ptychopariid species. Finally, inclusion of Liostracinidae in the Trinucleoidea by Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) seems related to a mistaken understanding of the ventral median suture in Liostracina. By regarding L. simesi Jago and Cooper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005, as a rostellum-bearing species, and L. volens Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, as a median-suture-bearing species, L. simesi can be inferred to show a rostral plate condition intermediate between ptychopariids and L. volens (Bignon et al., Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020, p. 1070). As discussed below, however, the medial suture is actually absent in both species, meaning that L. simesi does not exhibit a transitional character state.

Historically, more than one-third of trilobite families have been assigned to the order Ptychopariida, which raises considerable issues related to our understanding of phylogenetic relationships. The Ptychopariida has undergone several revisions since its original conception, and is now commonly considered to be a paraphyletic or polyphyletic group (Babcock, Reference Babcock1994; Cotton, Reference Cotton2001; Lieberman and Karim, Reference Lieberman and Karim2010; Adrain, Reference Adrain and Zhang2011; Bignon et al., Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020; Paterson, Reference Paterson2020). A thorough restudy of the ‘ptychopariids’ is long overdue, and it will undoubtedly lead to significant revision of the concept of the group. Pending further information bearing on the phylogenetic relations among ‘ptychopariids,’ here we provisionally assign Liostracinidae to the Ptychopariida because the characteristics of this family revealed by this study are most similar to those occurring in taxa among classic ptychopariids. The natant hypostomal condition and rostral plate, in particular, suggest an affinity with some taxa assigned to the order. Those characters, combined with others (e.g., median preglabellar furrow, lack of a ventral median suture, a non-asaphoid-type protaspis, which is inferred from a congeneric species, and a parallel-sided anterior section of the facial suture), strengthen that indication of affinity.

According to Jell and Adrain (Reference Jell and Adrain2003), the family Liostracinidae embraces four genera: Liostracina Monke, Reference Monke1903; Aplexura Rozova, Reference Rozova1963; Doremataspis Öpik, Reference Öpik1967; and Lynaspis Öpik, Reference Öpik1967. Another genus, Gibbura Varlamov et al., Reference Varlamov, Pak and Rozova2005, was added to the family since the time of Jell and Adrain's (Reference Jell and Adrain2003) work. Among these taxa, Aplexura and Gibbura, both from Yakutia (Siberia), Russia, are here excluded from the family. Aplexura is based on a single species, A. pallida Rozova, Reference Rozova1963, which is known only from the holotype cranidium (Rozova, Reference Rozova1963, p. 13–14, pl. 1, fig. 18). Gibbura is based a single species, G. lepida (Lazarenko, Reference Lazarenko1968), which originally was assigned to Aplexura by Lazarenko (Reference Lazarenko1968, p. 177). Both genera differ from all other liostracinid genera in having a prominent preglabellar boss, a subquadrate glabella that is truncated rather than rounded or acutely rounded anteriorly, and an ocular ridge having its abaxial end immediately posterior to the preglabellar furrow rather than well behind it. Based on current information, Liostracina, Doremataspis, and Lynaspis should be retained in the family Liostracinidae.

Genus Liostracina Monke, Reference Monke1903

Type species

Liostracina krausei Monke, Reference Monke1903 (p. 114, pl. 3, figs. 10–17) from the Neodrepanura Zone, Kushan Formation, near Yanzhuang, Shandong, North China.

Other species

Liostracina volens Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, (p. 353–355, pl. 35, figs. 1–5) from the O'Hara Shale and Georgina Limestone, Georgina Basin, western Queensland, Australia; Liostracina nolens Öpik, Reference Öpik1967 (p. 355, pl. 35, figs. 6, 7) from the Georgina Limestone, Georgina Basin, western Queensland, Australia; Liostracina bella Lin and Zhou in Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin and Zhou1983 (p. 407, pl. 3, figs. 7–10) from the Tuanshan Formation, southern Jiangsu, China; Liostracina bilimbata Zhang in Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983 (p. 200, pl. 67, figs. 4, 5) from the Kushan Formation, northern Anhui, China; Liostracina qingyangensis Qian and Qiu in Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983 (p. 201, pl. 67, fig. 1) from the Tuanshan Formation, southern Anhui; Liostracina suixiensis Bi in Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983 (p. 201, pl. 67, fig. 2) from the Kushan Formation, northern Anhui, China; Liostracina simesi Jago and Cooper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005 (p. 671, fig. 4A–E) from the Spurs Formation, Northern Victoria Land, Antarctica; Liostracina kaulbacki Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007 (p. 32, fig. 13), from the Skewthope Formation, Bonaparte Basin, Australia; Liostracina tangwangzhaiensis Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014 (p. 398, figs. 1, 2) from the Kushan Formation, Tangwangzhai, Changqing, Shandong, North China; Liostracina joyceae Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018 (p. 41, fig. 20) from the Shannon Formation, Amadeus Basin, Northern Territory, Australia; Liostracina cf. L. nolens Öpik sensu Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Jago and Begg1996 (p. 381, fig. 6V, W) from the Molar Formation, Northern Victoria Land, Antarctica; Liostracina sp. sensu Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011 (p. S6, sup. fig. S7) from the Sesong Formation, Jikdong, South Korea; Liostracina cf. L. kaulbacki Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007, sensu Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018 (p. 44, fig. 21) from the Shannon Formation, Amadeus Basin, Northern Territory, Australia; Liostracina sp. sensu Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018 (p. 46, fig. 22) from the Shannon Formation, Amadeus Basin, Northern Territory, Australia; and Liostracina fuluensis n. sp.

Three species are questionably assigned to the genus: Liostracina? pauper Resser and Endo, Reference Resser, Endo, Endo and Resser1937 (p. 239, pl. 45, fig. 10); L.? paupiforme Endo, Reference Endo1944 (p. 78, fig. 17) from the Changhia (=Taitzu) Formation, Liaoning, China; and Liostracina bifurcata Zhang in Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983 (p. 200, pl. 67, fig. 3) from the Kushan Formation, northern Jiangsu, China. Liostracina? pauper and L.? paupiforme have short preglabellar fields. They were questionably assigned to Liostracina originally, and we concur with the assignments. Liostracina bifurcata has an anteriorly truncated and an unusually bifurcated eye ridge. In these respects, it differs from other species assigned to Liostracina. As noted by Park et al. (2014, p. 398), each of these species is represented by a single and poorly preserved cranidium. Two tiny cranidia from the DuNoir Limestone, Wyoming, USA, assigned as cf. Liostracina sp. by Lochman and Hu (Reference Lochman and Hu1961, p. 142, pl. 30, figs. 49, 50), appear to be erroneously assigned to this genus because the material has a highly convex cranidium, an anteriorly located palpebral lobe, a short preglabellar field, and a proportionately long glabella.

Diagnosis

Cephalon, excluding genal spines, lunate or semicircular; cranidium with moderately long (sag.) frontal area; median preglabellar furrow weak, variably incised or effaced; glabella slightly tapering forward to parallel-sided, acutely to obtusely rounded anteriorly, with three pairs of short, distinct to effaced lateral furrows; bacculae obliterated to distinct; palpebral lobe small, located posteriorly; eye ridge weak to distinct, gently oblique rearward; facial suture opisthoparian; rostral suture submarginal, connective sutures closely spaced, defining narrow rostral plate; librigenal spine broad proximally, with border ridge and slender, ribbon-like edge. Thorax of eight segments, fulcrate anteriorly and nonfulcrate posteriorly. Pygidium transversely subtriangular, with transverse pleural and interpleural furrows and upturned lateral and posterior borders. Surface smooth, granulate, or wrinkled on preocular field.

Remarks

The diagnosis is emended based on all known species referred to Liostracina. Previously, Monke (Reference Monke1903) provided a detailed description on Liostracina krausei, the type species, which formed the basis for understanding the generic concept; Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Qian and Zhu1963, p. 121) published a brief diagnosis; and Öpik (Reference Öpik1967) discussed the genus, as then known, in detail. New information provided here relates to the thoracic morphology and the ventral cephalic structure.

Liostracina is a distinctive ptychopariid trilobite that has a median preglabellar furrow on the dorsal side and rostral and connective sutures on the ventral side. The ventral connective sutures are closely spaced, and define a narrow rostral plate. Liostracina differs from Doremataspis by the presence of median preglabellar furrow, the narrower anterior area of fixigena, the more anteriorly placed palpebral lobe, and much smaller rostral plate in ventral side. Lynaspis bears a median preglabellar furrow, but differs in having an undivided anterior area of fixigena and more divergent anterior branch of facial suture. In Liostracina, the median preglabellar furrow on the dorsal side is variable in length and degree of incision. The preglabellar median furrow is commonly well defined, complete to nearly complete in L. bella, L. bilimbata, and L. volens (Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, pl. 35, figs. 1–3; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin and Zhou1983, pl. 3, figs. 7, 8; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a, pl. 61, figs. 6, 11, pl. 62, figs. 2, 4), faint and incomplete in L. qingyangensis, L. simesi, L. suixiensis, L. tangwangzhaiensis, L. joyceae, and L. cf. L. kaulbacki (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Lu, Zhu, Bi, Lin, Zhou, Zhang, Qian, Ju, Han and Wei1983, pl. 67, figs. 1, 2; Jago and Copper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005, fig. 4A, B, D; Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014, figs. 1.1, 2; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018, figs. 20, 21), and effaced in L. kaulbacki (Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007, fig. 13A–G). The distinctness or relative effacement of the bacculae, lateral glabellar furrows, and eye ridges varies among and sometimes within species of Liostracina. The bacculae are well defined in most species, but obscure in L. tangwangzhaiensis (Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014, fig. 2.20) and absent in L. kaulbacki and L. sp. sensu Park and Choi (Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007, fig. 13A–G; Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S7.1, S7.5, S7.8). In L. fuluensis n. sp., the length of bacculae varies intraspecifically. The lateral glabellar furrows, especially the S1 and S2 furrows, are clearly defined in some species, but faint or effaced in others. The eye ridge is well defined in most species, but obscure or absent in L. tangwangzhaiensis and L. kaulbacki.

Liostracina fuluensis new species

Figures 2–7

- Reference Peng, Yang, Liu, Zhu, Sun, Zamora, Mao and Zhang2020

Liostracina sp., Peng et al., p. 456, fig. 3O.

Figure 7. Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. from the Longha Formation, Guzhangian, Fulu area, southeastern Yunnan; specimens showing ventral structure; white arrowhead indicates the posterior margin of thorax; for abbreviations see caption of Figure 4; (1, 3, 7–9, 11, 12) ventral views, (2, 4–6, 10) dorsal views; (1) NIGP 173769, degree 5 meraspid exoskeleton lacking cranidium; (2, 3) NIGP 173770, degree 6 meraspid exoskeleton with cephalic doublure, (3) is the reversed image of (2) in gray tone; (4, 7) NIGP 173771, degree 6 meraspid exoskeleton with cephalic doublure and missing cranidium, (7) is latex cast of (4); (5, 8) NIGP 173772, partly disarticulated, holaspid exoskeleton with cephalic doublure and latex cast; (6, 9) NIGP 173773, holaspid exoskeleton and latex cast, with cephalic doublure; (10–12) NIGP 173774, holaspid exoskeleton (10) and latex cast (11, 12), with cephalic doublure. All scale bars represent 2 mm.

Holotype

NIGP 171341, external mold of exoskeleton (Fig. 3.2, 3.3) from the upper part of the middle member of the Longha Formation, Fulu, Funing, Yunnan, China.

Paratypes

NIGP 173732–173774, including 26 variously complete, figured exoskeletons, seven cephala, five cranidia, four librigenae, and one pygidium, from the same location and stratigraphic interval as the holotype.

Diagnosis

A species of Liostracina with long preglabellar area, incomplete and weakly defined median preglabellar furrow, weakly to well-defined eye ridge, and baccula; facets present on anterior four thoracic pleurae.

Occurrence

Lower part of the middle member of the Longha Formation, equivalent to the upper Proagnostus bulbus and lower Linguagnostus reconditus zones.

Description

Exoskeleton subrounded, about as long as wide; axis narrow, occupying 0.78–0.80 sagittal length of exoskeleton. Cephalon large, lunate in outline (or semicircular if the librigenal spines are excluded), occupying a little more than one-half exoskeletal length. Glabella moderately convex, tapering slightly forward or parallel-sided, acutely rounded to rounded anteriorly, occupying about one-half cephalic length; with three pairs of straight lateral furrows, equally spaced; S1 and S2 weak to deeply incised, gently oblique rearward; S3 faint; occipital ring long (sag.), slightly shortened abaxially, about one-fourth of sagittal length of glabella, with curved posterior margin and faint or effaced occipital node; occipital furrow transverse; baccula distinct to faint, long, oval, distinct from glabella. Median preglabellar furrow incomplete, weak. Anterior border convex, smoothly curved, defined by shallow and long (sag., exs.) anterior border furrow; preocular field of fixigena long and broad, occupying more than one-half fixigenal length (exs.); palpebral lobe reniform, located posteriorly; eye ridge usually distinct, rarely weak, at angle of ~75° to sagittal line; palpebral and postocular areas grade gently to axial furrow; posterior border furrow prominent, posterior cranidial border short (exs.), uniform in length; anterior branch of facial suture diverges, then curves inward and forward, continuing onto ventral side; posterior branch short, diverging at angle of ~40° to sagittal line. Librigena half as wide as cranidium, exsagittal length including spine greater than sagittal length of exoskeleton; genal spine broad proximally, curving inward as it extends posteriorly, with convex ridge on lateral and posterior borders.

Ventrally, cephalic doublure is short and wide anteriorly, bounded posteriorly by submarginal stenoptychopariid rostral suture; lateral cephalic (or librigenal) doublure widest at posterior margin of cephalon, narrowing gently both anteriorly to connective suture and posteriorly to tip of librigenal spine; paired connective sutures are closely spaced, straight or gently curved, parallel or at an acute angle to sagittal line, and define a narrow, subtrapezoidal or rectangular rostral plate.

Hypostome in natant condition, shield-shaped, with gently inflated middle body comprising oval anterior lobe, faint middle furrow, and apparently semicircular posterior; lateral border narrow and convex; posterior border not well known, probably with rounded posterior margin.

Holaspid thorax with eight segments; axis moderately convex, nearly as wide as pleural area anteriorly but progressively narrowing posteriorly; pleurae of low convexity; anterior four segments with pointed tips and facets; fifth segment may have incomplete facet; posterior three or four segments with straight tips. Ventral thoracic doublure c-shaped on anterior four segments (Figs 4, 5.16, 6.1, 6.20, 7.11), narrow and thin (tr.), bar-shaped on posterior four segments.

Figure 4. Reconstruction of Liostracina fuluensis n. sp.; dorsal exoskeleton (left) and ventral exoskeleton (right). Sculpture on preocular fields and terrace ridges on cephalic doublure are omitted. Abbreviations for this figure and Figures 5–7: cd, cephalic doublure; cs, connective suture; e, eye; es, eye socle; f, facet; fs, facial suture; h, hypostome; pd, pygidium doublure; pl, palpebral lobe; rp, rostral plate; rs, rostral suture; td, thoracic doublure. Scale bar represents 2 mm.

Figure 5. Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. from the Longha Formation, Guzhangian, Fulu area, southeastern Yunnan; specimens showing ventral structure; white arrowhead indicates the posterior margin of thorax; for abbreviations see caption of Figure 4; (1, 2, 4–10, 12) dorsal views; (3, 11, 13–16) ventral views; (1) NIGP 173746, degree 7 meraspid exoskeleton with cephalic doublure; (2, 3) NIGP 173747, external mold of degree 7 meraspid exoskeleton and latex cast with cephalic doublure; (4) NIGP 173748, enrolled holaspid exoskeleton; (5) NIGP 173749, exoskeleton with cephalic doublure; note the right librigena has moved inward slightly, resulting in a narrow look to the rostral plate; (6, 7) NIGP173750, cephalon bearing two thoracic segments, with doublure; note specimen seems to be compressed transversely, resulting a narrow look to the rostral plate; (8, 9, 14, 15) NIGP 173751, 173752, holaspid exoskeleton with cephalic doublure, (14) is the latex cast of (8), and (15) is latex cast of (9); (10, 11) NIGP 173753, cranidium and its latex cast, showing a long baccula; (12) NIGP 173754, cranidium; (13) NIGP 173755, latex cast of cranidium; (16) NIGP 173756, latex cast of incomplete exoskeleton lacking the right librigena and having a displaced left librigena. All scale bars represent 2 mm.

Figure 6. Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. from the Longha Formation, Guzhangian, Fulu area, southeastern Yunnan; specimens showing ventral structure; white arrowhead indicates the posterior margin of thorax; for abbreviations see caption of Figure 4; (1–10, 13, 14, 18–20) dorsal views; (11, 12, 15–17) ventral views; (1, 2) NIGP 173757, external mold of holaspid cephalon with cephalic doublure, six thoracic segments and broken left librigena; (3, 4) NIGP 173758, holaspid cephalon with cephalic doublure; (5, 6) NIGP 173759, holaspid cephalon with cephalic doublure, five inverted thoracic segments, and missing occipital ring; (7, 8, 11) NIGP 173760, holaspid exoskeleton (7, 8) and latex cast with cephalic doublure (11); (9, 10) NIGP 173761, cephalon missing the right librigena; (12) NIGP 173762, latex cast of holaspid exoskeleton; (13, 14) NIGP 173763, latex cast of cephalon with cephalic doublure and lacking occipital ring; (15–17) NIGP 173764, 173765, 173766, doublure of librigena, note the straight adaxial tip; (18) NIGP 173767, latex cast of librigena; (19, 20) NIGP 173768, exoskeleton lacking the librigenae, and enlargement of part of the same specimen. All scale bars represent 2 mm.

Pygidium of low convexity, subtriangular in outline, wide and short, with upturned lateral and posterior border. Axis conical, faintly divided into three rings and a terminal piece that reaches almost to posterior border furrow. Pleural field flat, with faint, transverse pleural and interpleural furrows. Pygidial doublure forms a narrow ridge rim.

Dorsal surface mostly smooth, except for preocular field, which is covered with radial wrinkles; doublure of librigena bears fine terrace ridges.

Etymology

After Fulu Village, Funing County, southeastern Yunnan Province; site of the section yielding the Fulu Biota, including this species.

Remarks

The new species is most similar to Liostracina volens Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, from Australia, but differs in having a broader (sag, exsag.) anterior cranidial border, shallower border furrow, and an incomplete, less-distinct median preglabellar furrow. The new species also appears to differ from L. volens in having a longer preglabellar area in large holaspides. In L. fuluensis n. sp., the proportional length of the preglabellar area varies from 0.74–0.95 of the glabellar length (excluding occipital ring), and in most specimens it is more than 0.80 of the glabellar length. For comparison, the holotype cranidium of L. volens (Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, pl. 35, fig. 1), has a proportionate length of 0.70–0.72. The new species differs further in having three pairs of lateral glabellar furrows with S1 and S2 strongly incised, a much shallower and wider (sag., exs.) anterior cranidial border, and an incomplete preglabellar median furrow. In L. volens, there are only two pairs of shallow glabellar furrows, the anterior border furrow is narrow (sag., exs.) and deeply incised and the preglabellar median furrow is longer, nearly reaching to the anterior cranidial furrow.

The long preglabellar area of L. fuluensis n. sp. also helps differentiate the new species from some other congeneric species that have shorter preglabellar areas. Liostracina kaulbacki, L. suixiensis, L. simesi, L. krausei, and L. joyceae and all have proportionate preglabellar lengths of <0.70 (~0.48 in L. kaulbacki, ~0.65 in L. simesi, ~0.68 in both L. bilimbata and L. suixiensis, ~0.69 in L. krausei, and ~0.58 to ~0.69 in L. joyceae).

Liostracina nolens, L. simesi, and L. joyceae differ from L. fuluensis n. sp. in having granulate sculpture dorsally, whereas L. tangwangzhaiensis, L. kaulbacki, and L. krausei show greater degrees of effacement. Liostracina bella and L. qingyangensis are easily distinguished from L. fuluensis n. sp. by having a curved ridge immediately behind the anterior cranidial border furrow.

Discussion

Ventral structures in Liostracina.—Previously, little was known of the ventral cephalic structure of Liostracina. When Liostracina was erected, Monke (Reference Monke1903, pl. 3, fig.12) illustrated an external mold of a cranidium of L. krausei, the type species, in ventral view. The specimen bears a short but wide anterior portion of the cephalic doublure. Subsequently, Öpik (Reference Öpik1967, pl. 35, figs. 4, 5) figured doublures of two separated librigenae of L. volens. Each librigena bears a straight adaxial tip anteriorly; they appear close to the sagittal line of the cranidium. Based on the presence of a rostral plate and connective suture in Doremataspis, another liostracinid genus, Öpik (Reference Öpik1967, p. 357) inferred that if a rostral plate were present in Liostracina, “it should be a small piece because of near-midline extent of doublure of free check, as seen in Liostracina krausei Monke and L. volens sp. nov.” However, Fortey and Chatterton (Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988) interpreted the librigenal tip of L. volens as a ventral median suture and disregarded the other ventral features recorded by Monke (Reference Monke1903) and inferred by Öpik (Reference Öpik1967). The work by Monke (Reference Monke1903) and Öpik (Reference Öpik1967) implies the presence of a rostral plate rather than a median suture.

The presence of a rostral plate is affirmed by the new material of L. fuluensis n. sp. Specimens of L. fuluensis n. sp. show the anterior portion of the cephalic doublure (Fig. 5.9–5.13, 5.15, 5.16) to be identical with the homologous structure illustrated by Monke (Reference Monke1903), and show the adaxial tips of the librigenae to be identical with the homologous structures illustrated by Öpik (Reference Öpik1967; see Fig. 6.15–6.17). As shown schematically in Figure 4 (right), the anterior portion of the cephalic doublure is bounded by a submarginal rostral suture and the librigenal adaxial tip terminates at a connective suture. The paired connective sutures are closely spaced, defining a narrow rostral plate medially on the cephalic doublure (Figs. 5.1–5.8, 5.14, 5.15, 6.1–6.14, 7). Judging from the presence of a similar short and wide anterior portion of the cephalic doublure in L. krausei, and from a similar adxial tip in L. volens, this pattern of ventral structure was present in these Liostracina species as well.

Two Liostracina species illustrated by Park and Choi (Reference Park and Choi2011) from Korea show ventral cephalic structures that appear essentially identical to those in L. fuluensis n. sp. A degree 2 meraspid of L. simesi bears a rostral plate and connective sutures (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S6.27–32). Park and Choi (Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S6.15) interpreted the subtriangular “space” on the cephalic doublure of this specimen as the location of the rostral plate, whereas it was interpreted as that of a rostellum by Bignon et al. (2020, p. 1070). However, magnifying their image of the anteromedial part of the cephalic doublure (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S6.32) shows that the connective sutures are separated and that there is a broken rostral plate still in place between the sutures. The rostral plate looks to be inverted-subtrapezoidal rather than subtriangular in shape, with a short, parallel-sided posterior part and a largely broken anterior part. The paired connective sutures are rather curved, with the right one being more obscure on the image. Associated librigena illustrated by Park and Choi (Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S6.15–20) have oblique and gently curved adaxial tips, which tends to confirm this reinterpretation of the ventral structure with a rostral plate in L. simesi. New observations indicate that the Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020)'s interpretation of the ventral arrangement of L. simesi is incorrect. Furthermore, a cranidium illustrated in ventral view (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S6.13) shows a short, wide anterior portion of the cephalic doublure, similar to Monke's (Reference Monke1903, pl. 3, fig.12) figure, and similar to specimens illustrated here (Fig. 5.9–5.12, 5.15, 5.16). A specimen assigned as Liostracina sp. (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011) likewise shows an oblique, curved connective suture in separated librigenae and on the cephalic doublure of a cranidium (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S7.4, S7.6). We agree that the “peculiar ventral structure” in a specimen of L. sp. (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. fig. S7.7–12) is a rostral plate; it is now slightly out of place (moved rearward).

The new material reveals L. fuluensiis n. sp. to have a simple hypostome in natant condition (Figs. 4.1, 6.12, 7). Both the hypostomal morphology and the attachment condition are comparable to those of ptychopariid trilobites. Prior to this report, the hypostome and its attachment condition were unknown for Liostracina. In assigning Liostracina as a primitive asaphid, Fortey and Chatterton (1988, p. 211–212) relied on other characters, such as the tapering glabella and the presence of a preglabellar field. New information about the ventral morphology indicates instead that Liostracina has a characteristic ptychopariid morphology.

Reassignment of Liostracina and family Liostracinidae.—Liostracina was first assigned to the family Liostracinidae Raymond (Reference Raymond1937), with Liostracina as the type genus. The family Liostracinidae has been widely accepted by most subsequent authors (e.g., Zhu, Reference Zhu1959; Öpik, Reference Öpik1967; Zhou and Liu, Reference Zhou and Liu1977; Lin and Zhou in Lin et al., Reference Lin, Lin and Zhou1983; Zhang and Jell, Reference Zhang and Jell1987; Zhu and Wittke, Reference Zhu and Wittke1989; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a; Jago and Cooper, Reference Jago and Cooper2005; Shergold et al., Reference Shergold, Laurie and Shergold2007; Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011; Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Paterson and Brock2018). Moore (Reference Moore and Moore1959), and then Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi1962), assigned Liostracina to a different family, the Emmrichellidae. Both the Liostracinidae and the Emmrichellidae were commonly classified in the suborder Ptychopariina. However, based on the conjectural presence of a ventral median suture in Liostracina volens, and the morphological similarity between Cambrian Liostracina and the Early Ordovician (Tremadocian) trinucleoidean Oremetopus Brögger, Reference Brögger1898, Fortey and Chatterton (Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988) reassigned Liostracina as a primitive asaphid, and considered the Liostracinidae to be a sister group to post-Cambrian trinucleoideans. Fortey and Chatterton (Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988) classified the superfamily Trinucleoidea Hawle and Corda, Reference Hawle and Corda1847, within the suborder Asaphina Salter, Reference Salter1864. Characters present in Liostracina and the Liostracinidae such as the tapering glabella and the presence of a preglabellar field, which are characteristic of ptychopariids, were inferred to be primitive characters of asaphids. Afterward, Fortey (Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997) elevated the suborder Asaphina to order level (as Asaphida); this classification has been followed by subsequent authors (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004a; Adrian, Reference Adrain and Zhang2011; Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014).

Classification of Liostracina (and the family Liostracinidae) as an asaphid (Fortey and Chatterton, Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988) was rooted in the interpretation of an “undoubted median suture” on the ventral doublure of Liostracina. A ventral median suture is a synapomorphy for the order Asaphida. This interpretation of a median suture in Liostracina, in turn, hinged on the presence of a straight adaxial tip in a separated librigena (Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, pl. 35, fig. 4). New evidence, from L. fuluensis n. sp., shows that a straight adaxial tip in a librigena is ambiguous evidence of a median suture because it can also occur in taxa having a narrow rostral plate. This possibility, previously discussed by Öpik (Reference Öpik1967) for L. volens, is now verified in L. fuluensis n. sp. (Fig. 6.15–6.17). As discussed above, connective sutures, rather than a median suture, are also present in L. simesi and L. sp. from the Sesong Formation, South Korea. An illustrated specimen of L. sp. from the Sesong Formation also appears to have a displaced rostral plate (Park and Choi, Reference Park and Choi2011, sup. figs. S6.31, S6.32, S7.9–12).

Based on a single librigena claimed to have “rounded corners” on doublure, Öpik inferred that Auritama trilunata Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, bears a small, triangular rostellum placed in front of ventral median suture (Öpik, Reference Öpik1967, pl. 15, fig. 1; text-fig. 75). Such conjecture of both rostellum and median suture lacks support by direct evidence on the cephalic doublure and the “rounded corners” could be a false appearance caused by the notably convex doublure. Based on disarticulated librigenae of Tsinania canens (Walcott, Reference Walcott1905), Park and Choi (Reference Park and Choi2009) suggested that the ventral median suture has a polyphyletic origin, and argued that the order Asaphida should be defined exclusively by the presence of the asaphoid protaspis. Those conclusions lead Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) to consider the ventral median suture to be homoplastic across Trilobita, formed in separate pathways. The new material of Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. reported here demonstrates that the axial tip of a disarticulated librigena is an unreliable proxy for interpreting whether or not a median suture was present. As such, there is no direct evidence of a median suture in either A. trilunata or T. canens. As a corollary, the idea that the median suture evolved multiple times lacks support from both species.

The presence of a rostral plate and connective sutures, combined with the absence of a ventral median suture in at least three species of Liostracina, indicates that Liostracina and the Liostracinidae should be reassigned from the Asaphida and the Trinucleoidea sensu Fortey (Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997). Liostracina and Liostracinidae also should be reassigned from Trinucleida sensu Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020). Overall, the morphology of Liostracina includes an opisthoparian facial suture, a long preglabellar field, a non-pyriform glabella, and a parallel-sided anterior section of the facial suture on the dorsal side. In addition, presence of a rostral plate, connective sutures, and a natant hypostomal condition on the ventral side are all more consistent with assignment to the Ptychopariida (as currently construed, pending further reevaluation). In their Bayesian tip-dating clock phylogenetic tree of Cambrian trilobites, Paterson et al. (2019, figs. 1, 2) grouped Liostracina and Prodamesella Zhang, Reference Zhang1957, together. Their Bayesian strict clock tree shows that Liostracina is sister taxon to a clade consisting of Jiulongshania, Fenghuanella, Oligometopus, and Parakoldinioidia (Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Edgecombe and Lee2019, fig. 2), and their parsimony tree shows that Liostracina is sister taxon to Fenghuanella (Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Edgecombe and Lee2019, fig. 3). Prodamesella, Fenghuanella, and Jiulongshania are regarded as ptychopariids (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock and Lin2004b; Peng, Reference Peng, Zhou and Zhen2008; Park et al., Reference Park, Han, Bai and Choi2008; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Li, Mu, Lin and Zhu2012) and by implication, Liostracina also should be considered a ptychopariid. As shown by the strict clock tree, Oligometopus and Parakoldinioidia are less related to Liostracina than Fenghuanella, and are now classified as taxa of order uncertain (Fortey, Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Choi2008; Adrian, Reference Adrain and Zhang2011). We agree with Bignon et al. (2020, p. 1074) in regarding the Liostracinidae as monophyletic, but, as discussed above, reject their view that the family is a sister taxon to all other families of their order Trinucleida. There appears to be little evidence of a close relationship between Liostracina and trinucleoidean trilobites.

Classification of Liostracina and the Liostracinidae in the order Ptychopariida is further supported by morphology of the protaspides of Liostracina tangwangzhaiensis from North China (Park et al., Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014), which have a characteristic ptychopariid aspect, including a nearly flat dorsal exoskeleton (see Fortey and Chatterton, Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988, pl. 17, figs. 13, 16; Chatterton and Speyer, Reference Chatterton, Speyer and Kaesler1997, figs. 170.6, 170.7). In contrast, protaspides of most known Ordovician trinucleoideans have a characteristic ‘asaphoid protaspis’ morphology: inflated, and rather globular in shape. Six different types of trinucleoid protaspides were recognized by Bignon et al. (2020, fig. 3; see also Fortey and Chatterton, Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988; Chatterton et al., Reference Chatterton, Edgecombe, Speyer, Hunt and Fortey1994; Chatterton and Speyer, Reference Chatterton, Speyer and Kaesler1997; Fortey, Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997). The asaphoid protaspis (i.e., commutavi protaspis, as termed by Park and Kihm, Reference Park and Kihm2015; non-adult-like protaspis of Bignon et al., Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) is regarded as synapomorphic for either the order Asaphida (Fortey and Chatterton, Reference Fortey and Chatterton1988; Chatterton et al., Reference Chatterton, Edgecombe, Speyer, Hunt and Fortey1994; Fortey, Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997) or the true Trinucleida, and Liostracina does not have an asaphoid protaspis.

We agree with Park et al. (Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014) in recognizing significant morphological differences between the protaspides of Cambrian Liostracina and protaspides of post-Cambrian trinucleoideans. However, their interpretation that the flattened, non-asaphoid protaspis of Liostracina as a plesiomorphic condition for the Trinucleoidea was predicated on the prevailing view that Liostracina was a primitive trinucleoidean. Also, the concept expressed by Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) that the globular protaspides of the Asaphida and Trinucleida are not homologous was based on the phylogenetic position of Liostracina (as a basal trinucleid), which does not possess a globular protaspis. Reassignment of Liostracina as a ptychopariid reduces the likelihood of these phylogenetic scenarios. It is more plausible to consider the globular protaspid morphology of Ordovician trinucleoideans to be homologous with the asaphoid protaspis morphology of asaphids.

Park et al. (Reference Park, Kihm, Kang and Choi2014) suggested that the Trinucleoidea should be excluded from the order Asaphida based on interpretations about the Liostracinidae. In following this suggestion, Bignon et al. (Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020) excluded the subfamily Trinucleoidea from the Asaphida and elevated it to ordinal status as the order Trinucleida. Our new material suggests that the Liostracinidae should be excluded not only from the Asaphida but also from the superfamily Trinucleoida/order Trinucleidea. Removing the Liostracinidae from the superfamily Trinucleoidea and order Trinucleida eliminates the rationale for these reassignments. Pending a fuller evaluation of the systematic position of the Trinucleoidea (sensu stricto) or Trinucleida (sensu stricto), the presence of an asaphoid-type protaspis (commutavi protaspis) in trinucleoideans/trinucleids, suggests that reassignment of this group to the Asaphida is the best option at the present time (see Chatterton et al., Reference Chatterton, Edgecombe, Speyer, Hunt and Fortey1994; Fortey, Reference Fortey and Kaesler1997; Bignon et al., Reference Bignon, Waisfeld, Vaccari and Chatterton2020).

Conclusions

The new material assigned as Liostracina fuluensis n. sp. allows a fuller understanding of both the dorsal and ventral features of Liostracina. It reveals the genus to be characterized by having an opisthoparian facial suture on the dorsal side. Ventrally, a submarginal, stenoptychopariid rostral suture, closely spaced connective sutures separating a narrow rostral plate, and a natant hypostomal attachment condition are present. The new material indicates that the previously hypothesized ventral median suture does not exist.

Regarding the genus Liostracina as a primitive trinucleoidean and classifying the family Liostracinidae in the order Asaphida are unwarranted based on the available evidence. The arrangements of the dorsal and ventral structures, combined with the non-asaphoid protaspis of Liostracina, suggest that the genus and the family are ptychopariid, rather than asaphid, trilobites. As such, the Liostracinidae should be excluded from the superfamily Trinucleoidea, as well as from the order Asaphida, and should be reassigned to the order Ptychopariida.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yin B.-A. and Mo X.-X. from the Guangxi Institute of Geological Survey, Liu F. and Liu Z.-F., the residents of Balang Village of Jianhe County, Guizhou Province, for their assistance with field work. We also thank J. Paterson and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful reviews. The editorial work of B. Hunda and N. Hughes also helped to improve this manuscript. Peng S.-C. acknowledges support from the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy (grant number 20191101), the Institute of Geological Survey of China and the National Commission on Stratigraphy of China (grant number DD20190009). Yang X.-F. acknowledges support from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant numbers 41562001, 42162001). Zhu X.-J. acknowledges support from National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant numbers 41672002, 41672028). Liu Y. acknowledges support from National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (grant numbers 41861134032). This is a contribution to the IGCP 668 project “The Stratigraphic and Magmatic History of Early Paleozoic Equatorial Gondwana and its Associated Evolutionary Dynamics.”