Introduction

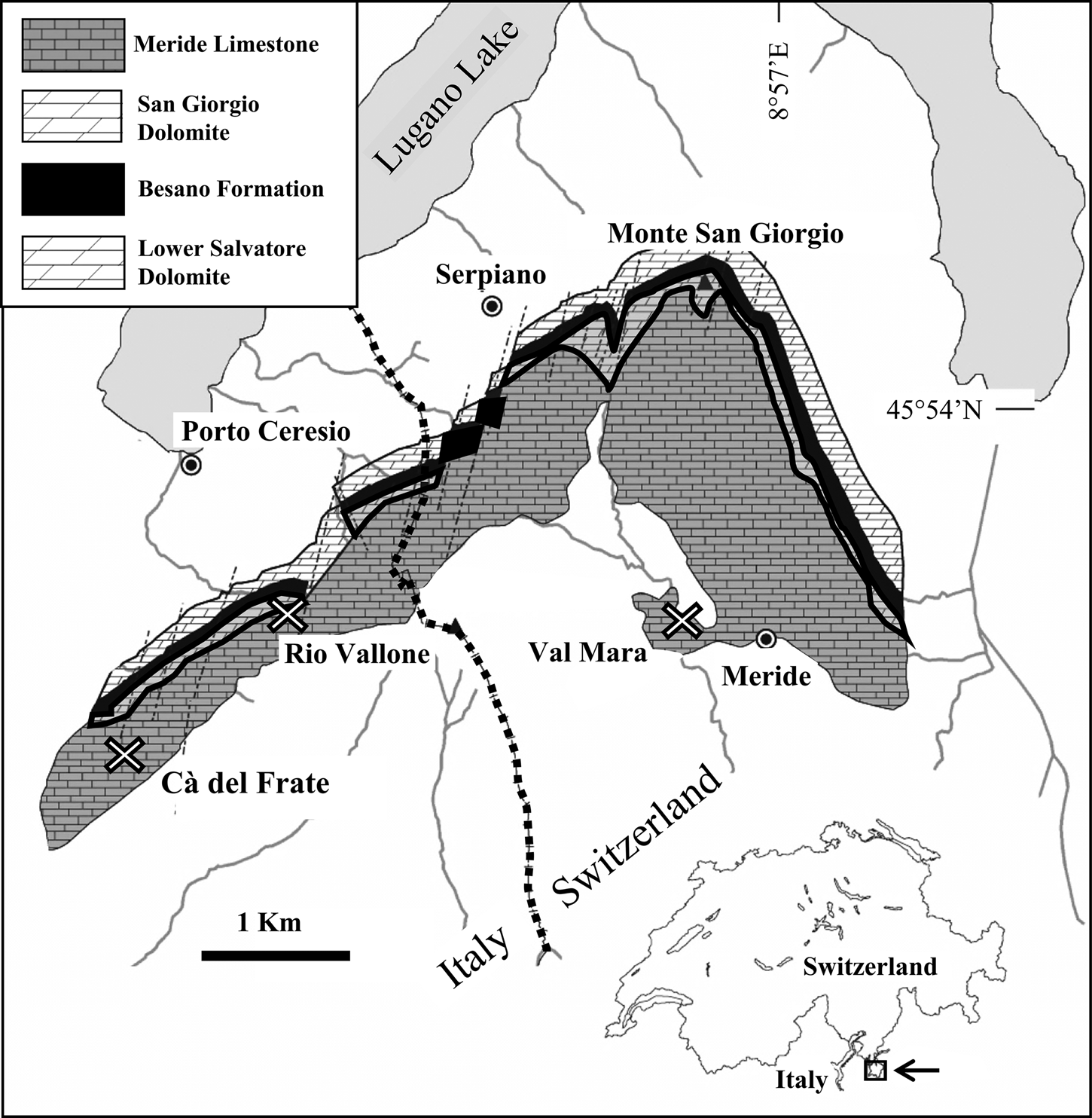

The Middle Triassic localities of the Monte San Giorgio area in Lombardy (northern Italy) and Canton Ticino (southern Switzerland) are sites where marine deposits have been studied through mining and scientific excavations over a period of more than 170 years. They are among the most important locations providing a well-preserved record of Middle Triassic marine life. Because of great interest, the Swiss side of Monte San Giorgio was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List in July 2003; in August 2010 it became a transboundary site after the extension to the Italian outcrops (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Map of the Monte San Giorgio area showing the Middle Triassic sequence with locations (X) of the sites Cà del Frate, Rio Vallone, and Val Mara (from Stockar, Reference Stockar2010, modified) and stratigraphic distribution of the insect fossils from Monte San Giorgio (right).

Several excavations have been made in the past decades in Switzerland by the Università degli Studi di Milano and the Paleontological Institute and Museum of the University of Zürich, in cooperation with the Cantonal Museum of Natural History of Lugano, and in Italy by the Università degli Studi di Milano, in cooperation with the Museo Insubrico di Storia Naturale di Clivio and Induno Olona, and by the Museum of Natural History of Milan.

The discoveries from the ‘Kalkschieferzone’ (see Geological setting) include many well-preserved specimens of fish, reptiles, arthropods, and rare plants (Tintori and Renesto, Reference Tintori and Renesto1983, Reference Tintori and Renesto1990; Tintori, Reference Tintori1990a, Reference Tintorib, Reference Tintori and Robbac; Renesto, Reference Renesto1993; Lombardo, Reference Lombardo1999, Reference Lombardo2001; Tintori and Lombardo, Reference Tintori, Lombardo, Arratia and Schultze1999, Reference Tintori and Lombardo2007; Krzeminski and Lombardo, Reference Krzeminski and Lombardo2001; Renesto et al., Reference Renesto, Lombardo, Tintori and Danini2003; Bechly and Stockar, Reference Bechly and Stockar2011; Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012; Strada et al., Reference Strada, Montagna and Tintori2014; Montagna et al., Reference Montagna, Haug, Strada, Haug, Felber and Tintori2017). Part of the collected material is still waiting for preparation or is under study.

International consideration focused on the Monte San Giorgio fossiliferous levels during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and during the past 15 years several new Middle Triassic marine Lagerstätten were discovered outside Europe, mainly in southern China (Motani et al., Reference Motani, Jiang, Tintori, Sun, Hao, Boyd, Hinic-Frlog, Schmitz, Shin and Sun2008; Tintori et al., Reference Tintori, Hitij, Jiang, Lombardo and Sun2014). As in the Monte San Giorgio area, the discoveries include many fully articulated specimens of reptiles, fishes, and arthropods.

The Xingyi Fauna from the Zhugampo Member of the Falang Formation, outcropping in a large area encompassing Xingyi (Guizhou Province), Fuyuan, and Luoping (Yunnan Province), is probably the closest in age to the Kalkschieferzone in the Monte San Giorgio area (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Motani, Hao, Rieppel, Sun, Tintori, Sun and Schmitz2009; Zou et al., Reference Zou, Balini, Jiang, Tintori, Sun and Sun2015). A recent detailed excavation has been carried out near Nimaigu (Wusha, Xingyi) to settle the stratigraphic distribution of the several vertebrate taxa so far described (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Sang, Diao, Motani and Tintori2012; Tintori et al., Reference Tintori, Sun, Lombardo, Jiang, Ji and Motani2012) from that fossiliferous level. Not all of the already known Xingyi Fauna taxa were collected during such an excavation, and for several reptile and fish taxa, the actual stratigraphic position is not yet ascertained in the series. However, two different assemblages can be recognized (Tintori et al., Reference Tintori, Hitij, Jiang, Lombardo and Sun2014), and the lower one yields also the lophogastrid mysidaceans described by Taylor, Schram, and Shen (Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001) as Schimperella acanthocercus from a site near Dinxiao, about 30 km from Nimaigu. Following Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Cheng, Lipps and Granier2009), and as observed during the May 2017 excavations (personal observation, A.T., 2017), these lophogastrids are mostly on mass mortality surfaces (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Cheng, Lipps and Granier2009, fig. 7). They are found in the Xingyi area together with the pachypleurosaur Keichousaurus (=Kweichousaurus in Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Cheng, Lipps and Granier2009), which characterizes the Lower Assemblage of the Xingyi fauna together with Habroichthys and Asialepidotus, fishes that are considered as marine (Tintori et al., Reference Tintori, Jiang, Motani, Sun, Ji, Zou and Ma2013). Thus, this assemblage is clearly marine as it includes marine reptiles (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Sang, Diao, Motani and Tintori2012) and rare ammonoids (personal observation, A.T., 2017). By contrast, the fossiliferous level of the Zhuganpo Member is made of well-bedded limestone, marly limestone, and mudstone at the top of massive limestones deposited on a carbonate platform, and the upper part of the level itself is very rich in ammonoids, crinoids, and daonellids (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Jiang, Motani, Ni, Sun, Tintori, Xiao, Zhou, Ji and Fu2018). The lower assemblage of the Xingyi Fauna has a few more taxa in common with the Kalkschieferzone fauna, such as the fishes Peltopleurus and Saurichthys and the sauropterygian Lariosaurus, all of them being quite widespread all along the Tethys during most of the Middle Triassic.

More recently, Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017) reported lophogastrid mysidaceans from the late Anisian Luoping Fauna (Member II of the Guanling Formation), Yunnan Province, where Fu et al. (Reference Fu, Wilson, Jiang, Sun, Hao and Sun2010) and Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Zhang, Zhou, Xie, Huang and Wen2012) previously described, respectively, Isopoda and Decapoda. Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017) described a new genus, Yunnanocopia, with two new species, Y. grandis and Y. longicauda, and a third possible new species was left in open nomenclature.

However, although in the past years following these new finds a major shift in the Triassic paleontological research from western to eastern Tethys has been recorded, not all the western Tethys fossils have been described yet. Apart from the new taxon herein described, it should be noted that Pelsonian (middle Anisian) specimens attributed to the lophogastrid Schimperella sp. have been recently found also in the Slovenian Alps (Križnar and Hitij, Reference Križnar and Hitij2010), and early Ladinian crustaceans (Thylacocephala and Decapoda) have been recorded in the northern Grigna Mountain in Italy (Tintori, Reference Tintori2013).

Geological setting

During the Middle Triassic, a thick sequence of up to 1,000 meters of limestones, dolomites, and organic shales was deposited in small basins along the western Tethys margin such as that at Monte San Giorgio (Fig. 2). There, several distinct stratigraphic units can be recognized, the most fossiliferous of which are the upper Anisian–lower Ladinian Besano Formation and the Ladinian Meride Limestone. During the late Anisian, there was also deposition of the widespread shallow-water carbonates of the Lower San Salvatore Dolomite (Zorn, Reference Zorn1971) that surrounded the Besano Formation lagoon. In the latest Anisian and Ladinian of the Monte San Giorgio area, the formation of an intraplatform basin with restricted circulation (Furrer, Reference Furrer1995) resulted in the alternate deposition of black shales and dolomites of the Besano Formation (once named Grenzbitumenzone by German researchers, e.g., Frauenfelder, Reference Frauenfelder1916). Later, after the shallow-water San Giorgio Dolomite, the deposition of the well-bedded and/or laminated limestones and marly limestones of the Meride Limestone took place.

Figure 2. Stratigraphic column from Stockar (Reference Stockar2010, modified) with distribution of Vicluvia (black bar). TS = type series.

The lower Meride Limestone (Furrer, Reference Furrer1995) begins with finely laminated limestones and ends with a dolomitized level, whereas the overlying upper Meride Limestone is a sequence of alternating well-bedded limestones and marlstones with increasing clay content toward the top. The uppermost 120 meters of the unit were named Kalkschieferzone by Senn (Reference Senn1924) and yield, among others, most of the fossils described in this paper. The age of the Kalkschieferzone was stated as late Ladinian on the basis of its palynological content (Scheuring, Reference Scheuring1978). Although no ammonoids or conodonts have been found, this age is supported by the fish assemblage (Tintori, Reference Tintori1998; Tintori and Lombardo, Reference Tintori, Lombardo, Arratia and Schultze1999), which is very similar to that found in the Perledo Member of the Perledo–Varenna Formation. Recently, Stockar et al. (Reference Stockar, Baumgartner and Condon2012) suggested a somewhat older age of the Kalkschieferzone, still in the late Ladinian but around its base.

This sequence records life in a tropical lagoon, sheltered and partially separated from the open sea, where water stratification periodically provided bottom anoxic conditions, allowing the preservation of organism remains and the accumulation of organic matter (Tintori, Reference Tintori1990a; Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012). Inferring by analysis of oil-source rock correlation, the Besano Formation and the Meride Limestone are the best oil-prone source rocks in the western Po Plain (Riva et al., Reference Riva, Salvatori, Cavaliere, Ricchiuto and Novelli1985; Bernasconi and Riva, Reference Bernasconi, Riva and Spencer1993).

These formations represent a regressive sequence with the filling of a lagoon, from true marine conditions to a probably unstable environment, with brackish or freshwater horizons, suggested in the uppermost part (the Kalkschiferzone) by the presence of clay, conchostracans, and insects (Tintori, Reference Tintori and Robba1990c; Strada et al., Reference Strada, Montagna and Tintori2014).

The Kalkschieferzone provides about 20 fish species (Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012), the most common of which are very small actinopterygians such as Prohalecites (Tintori, Reference Tintori1990a). Others include Peltopleurus (Lombardo, Reference Lombardo, Tintori, Felber, Danini, Moratto, Pacor and Tentor1999) and the nothosaurid Lariosaurus (Tintori and Renesto, Reference Tintori and Renesto1990; Renesto et al., Reference Renesto, Lombardo, Tintori and Danini2003). It also provides insects (Krzeminski and Lombardo, Reference Krzeminski and Lombardo2001; Bechly and Stockar, Reference Bechly and Stockar2011; Strada et al., Reference Strada, Montagna and Tintori2014; Montagna et al., Reference Montagna, Haug, Strada, Haug, Felber and Tintori2017), the conchostracan Laxitextella (= Palaeolimnadia sp. in Tintori, Reference Tintori and Robba1990c) indicating the periodic influence of freshwater (Tintori, Reference Tintori and Robba1990c; Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012), and rare terrestrial plants (Wirz, Reference Wirz1945; Stockar and Kustatscher, Reference Stockar and Kustatscher2010; personal observation, A.T., 1996–2003). The biota of the Kalkschieferzone lived in a tropical climate subject to strong seasonal changes, with mainly marine conditions with possibly brackish and/or freshwater short periods (Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012).

The beds yielding the specimens of the type series (CMISN specimens) of the new genus and new species Vicluvia lombardoae, here described, belong to the middle Kalkschieferzone outcropping in the Italian locality of Cà del Frate (village of Viggiù, Varese province; 45°53′01.43″N, 8°53′59.52″E).

The locality of Cà del Frate was already mentioned by De Alessandri (Reference De Alessandri1910) in his monograph on Triassic fishes, but it is only since the beginning of the 1980s that systematic field work with bed-by-bed sampling has been conducted by a group of the Milano University supported by the local Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Induno Olona (now Museo Insubrico di Storia Naturale di Clivio/Induno Olona).

The Cà del Frate fauna has been the subject of many studies; fishes, rare reptiles, and numerous crustaceans have been found. About 4,000 fishes, some specimens of the marine reptile Lariosaurus, and thousands of crustaceans belonging to the genera Vicluvia n. gen. and Laxitextella, mostly concentrated in mass mortality surfaces, have been collected during several field seasons in the years 1981–1997 (Tintori and Renesto, Reference Tintori and Renesto1983, Reference Tintori and Renesto1990; Tintori, Reference Tintori1990a, Reference Tintorib, Reference Tintori and Robbac; Renesto, Reference Renesto1993; Lombardo, Reference Lombardo1999, Reference Lombardo2001; Tintori and Lombardo, Reference Tintori, Lombardo, Arratia and Schultze1999; Renesto et al., Reference Renesto, Lombardo, Tintori and Danini2003).

Other specimens of Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. (CMISN specimens) came from the excavation at site D in the lower Kalkschieferzone in Val Mara, near the village of Meride (Mendrisio, Canton Ticino, Switzerland; 45°53′33.90″N, 8°56′47.04″E) (Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012). During the years 1997–2003, a joint project financed by the Cantonal Museum of Natural History in Lugano (MCSN) and operated by the Milano University allowed the collection of a few hundred fishes, several insects, and the same crustaceans as in Cà del Frate. The fossiliferous level of site D is placed between layer 102 of Scheuring (Reference Scheuring1978) and layer 60 of Wirz (Reference Wirz1945).

Both the investigated sections consist of a few meters of thin-bedded laminated limestones and marly limestones with minor marlstones and calcareous marlstones. Although most specimens have been collected during the detailed excavation, the oldest occurrence of the new species indicated by a single specimen, CMISN 1207, comes from just a few meters above the boundary between the San Giorgio Dolomite and the Meride Limestone, along the Rio Vallone near Porto Ceresio (Varese, Italy; 45°53′33.75″N; 8°54′40.29″E). This specimen is not included in the type series, being more ancient than the two main assemblages, and neither are the Swiss specimens that are somewhat older (uppermost part of the lower Kalkschieferzone) than the type series.

Materials and methods

Many hundreds of specimens were studied using a stereomicroscope equipped with a camera lucida drawing arm; measurements were taken with a caliper. To enhance details, some specimens were moistened with alcohol.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The examined specimens are deposited in Civico Museo Insubrico di Storia Naturale, Clivio, Italy (CMISN; formerly Museo di Storia Naturale di Induno Olona, Induno Olona, Italy [MSNIO]) and in Museo Cantonale di Storia Naturale di Lugano, Switzerland (MCSN).

Systematic paleontology

Class Malacostraca Latreille, Reference Latreille1802

Order Lophogastrida Boas, Reference Boas1883

Family Eucopiidae Sars, Reference Sars and Nartes1885

Remarks

Mysidaceans (s.l.) are shrimp-like malacostracans including more than 100 genera, with more than 1,000 species. Today they have a worldwide distribution. The majority of species inhabit coastal and open seawater, whereas a few species are adapted to freshwater. Several taxa are also described from different groundwater habitats and marine and anchialine caves. Following the classification proposed by Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001), mysidaceans include the extant Orders Mysida Haworth, Reference Haworth1825 and Lophogastrida Boas, Reference Boas1883 and the extinct Pygocephalomorpha Beurlen, Reference Beurlen1930.

The splitting of Mysidacea, together with the elevation of each former mysid suborder to order level, was previously proposed by Schram (Reference Schram1984, Reference Schram1986) and by Brusca and Brusca (Reference Brusca and Brusca1990) and was later accepted by Martin and Davis (Reference Martin and Davis2001). Probably because of the poor sclerotization of the shield, the reports of some fossil mysidacean groups are rare. In addition, most mysidaceans are quite small and thus not easy to collect during fieldwork, although, at least for the Triassic, they may occur in a great number.

Hessler (Reference Hessler and Moore1969) reported for Mysida (s.l.) the genera Schimperella Bill, Reference Bill1914 and Francocaris Broili, Reference Broili1917, from the Upper Jurassic of Germany. Nevertheless, according to Schram (Reference Schram1986), Francocaris grimmi Broili, Reference Broili1917, from the Jurassic Solnhofen limestones of Bavaria, is poorly understood, and this does not permit a clear assignment.

Of the two families of Lophogastrida, Lophogastridae Sars, Reference Sars1857 and Eucopiidae, the family Lophogastridae is represented in the fossil record solely by the late Middle Jurassic form Lophogaster volutensis Secretan and Riou, Reference Secretan and Riou1986 from La Voulte-sur-Rhone in France. Other supposed lophogastrids, Dollocaris ingens Van Straelen, Reference Van Straelen1923 and Kilianicaris lerichei Van Straelen, Reference Van Straelen1923, have since been assigned to Thylacocephala Pinna et al., Reference Pinna, Arduini, Pesarini and Teruzzi1982 (Benton, Reference Benton1993). Schram (Reference Schram1986) suggested a real lophogastridan affinity for Schimperella, assigning it to the family Eucopiidae together with Eucopia praecursor Secretan and Riou, Reference Secretan and Riou1986 of La Voulte-sur-Rhone.

Bill (Reference Bill1914) erected Schimperella to include two new species of mysidacean (s.l.), S. beneckei and S. kessleri, both from the lower Anisian (Middle Triassic) of Alsace (France). Schimperella was placed in Lophogastrida by Schram (Reference Schram1986) on the basis of the absence of a statocyst, the well-developed pleopods and pereiopods, the small abdominal pleurae, and the lophogastrid-like shield. Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001) supported this lophogastridan affinity and proposed a new diagnosis for Schimperella.

Until now, the genus has included two valid species, S. beneckei (with S. kessleri as junior synonym following Benton, Reference Benton1993) and S. acanthocercus Taylor, Schram, and Yan-Bin, Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001 from the late Ladinian Zhuganpo Member of the Falang Formation (Guizhou Province, southern China). The generic assignment of this last species should be now considered uncertain and in need of revision (see details in the discussion of the new species V. lombardoae).

Križna and Hitij (Reference Križnar and Hitij2010) reported Schimperella sp. also from the middle Anisian Strelovec Formation in Slovenia.

Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017) erected Yunnanocopia from the late Anisian Luoping Biota. Yunnanocopia includes two formally defined species, Y. grandis and Y. longicauda, and possibly a third left in open nomenclature. The specimens were recovered from two quarries in the middle part of Member II of the Guanling Formation, Luoping County, Yunnan Province (Feldmann et al., Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie and Maguire2016). All the previous Triassic lophogastrids appear to be very common, with a vertical distribution varying from a few dozen centimeters for S. acanthocercus to several hundred meters for the new taxon herein described. In light of the direct collecting by one of us (A.T.) in both Monte San Gorgio (this paper) and the Xingyi areas, preservation and average size of the specimens can be very different from bed to bed. For a better definition of new species, a stratophenetic approach should be applied where possible to avoid misinterpretation of differences in the samples due only to taphonomic processes among specimens coming from different levels.

Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017) considered Yunnanocopia the oldest occurrence of mysidaceans; nevertheless, the assemblage with Schimperella beneckei from the ‘Grès à Voltzia’ Formation in France should be older. According to Gall and Grauvogel-Stamm (Reference Gall and Grauvogel-Stamm2005), evidence of an early Anisian age for the Grès à Voltzia is given by conchostracans, foraminifers, and the occurrence of the bivalve Myophoria vulgaris. Recently, the Luoping Fauna has been dated to 242 Ma, thus toward the Anisian/Ladinian boundary (Tintori et al., Reference Tintori, Lombardo and Kustatscher2016).

Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017) assigned Yunnanocopia to Eucopiidae, thus including in this family three fossil genera: Eucopia Dana, Reference Dana1852; Schimperella, and Yunnanocopia. We agree with the considerations related to Eucopiidae reported by Feldmann et al. Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017 and, due to the similarities among Vicluvia and the other fossil genera included in the family, we tentatively assigned Vicluvia to the Eucopiidae with a sufficient degree of confidence.

Genus Vicluvia new genus

Type species

Vicluvia lombardoae new genus new species.

Diagnosis

As for the type species by monotypy.

Occurrence

In the type area, the Monte San Giorgio, the new taxon has been recorded in both Italy and Switzerland from the Meride Limestone (Ladinian), with the Kalkschieferzone (upper member) being by far the richest horizon. In the Kanton Graubünden, the lower Ladinian Prosanto Formation also yields rare specimens.

Etymology

The name, here in feminine gender, derives from Vicluvium, an ancient Latin name of Viggiù, the village where the type locality of the type species is located.

Remarks

Vicluvia differs from Schimperella mainly in the shape of the shield (Fig. 3), precervical and cervical grooves, antennal scale, and telson. Vicluvia exhibits a short shield, dorsally covering the first five thoracomeres; the two transverse grooves are dorsally vanishing and with their branches regularly arcing axially toward the posterior margin of the shield. In Schimperella, the shield does not cover dorsally all thoracic segments, and the transverse cervical groove is continuous and straight. In Vicluvia, the antennal scale is quite large but not like in Schimperella, where it is extremely large and obovate. Vicluvia exhibits a distally rounded telson whereas in Schimperella, the telson has a truncate distal margin.

Figure 3. Tentative reconstruction of Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp.

Vicluvia differs from Yunnanocopia mainly in the shape of the precervical and cervical grooves (Fig. 4), in the size of the antennal scale, in the presence of antennular lamina (males), in the pleonal pleurae, and in the shape of telson. In Vicluvia, the branches of both the precervical and cervical grooves are parallel and regularly arcing axially toward the posterior margin of the shield; in Yunnanocopia, the two branches of the precervical groove are inclined posterolaterally and those of the cervical groove are concave forward. The antennal scales of Vicluvia are more than half the length of the shield, and the scales together are as wide as the shield; thus, they are larger than those of Yunnanocopia. Pleonal pleurae are moderately well developed in Vicluvia, whereas they are strongly reduced or absent in Yunnanocopia. Many specimens of Vicluvia, probably males, exhibit a setose lamina (appendix masculine?) in the last peduncular segment of the antennule (basis), which is absent in Yunnanocopia. Vicluvia could have a diaeresis on the distally rounded telson, but this feature, hardly visible in a few specimens, could be an artefact due to bad preservation. In Yunnanocopia, uropods lack any indication of having been setose, although this could be due to bad preservation.

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the anterior body (dorsal view) in (1) Schimperella, (2) Vicluvia, and (3)Yunnannocopia.

Vicluvia lombardoae new species

Figures 5, 6

- Reference Tintori and Brambilla1991

Schimperella; Tintori and Brambilla, p. 65.

- Reference Bürgin, Eichenberger, Furrer and Schanz?1991

Coleoiden, Burgin et al., p. 102, fig. 2.

- Reference Bürgin, Eichenberger, Furrer and Schanz?1991

Schimperella beneckei Bill, Reference Bill1914; Burgin et al., p. 103, fig. 3.

- Reference Furrer1995

Schimperella beneckei; Furrer, p. 839, fig. 7b.

- Reference Lombardo1999

Schimperella; Lombardo et al., p. 103.

- Reference Gozzi, Lombardo and Larghi2003

Schimperella n. sp.; Gozzi, Lombardo, and Larghi, p. 1.

- Reference Lombardo, Tintori and Tona2012

Schimperella; Lombardo, Tintori, and Tona, p. 2004.

Figure 5. Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. from the Meride Limestone, Ladinian, Besnasca/Cà del Frate, Viggiù, Italy. (1, 2) Paratype CMISN 1192: (1) part; (2) counterpart. (3–5) Paratype CMISN 1206: (3) general view; (4) details of tail fan; (5) explanations. (6–9) Holotype CMISN 1179: (6) part; (7) counterpart; (8) details of tail fan; (9) explanations. CG = cervical groove; E = eye; En = endopod; Ex = exopod; PCG = precervical groove; S = antennal scale; T = telson. Scale bars = 5 mm.

Figure 6. Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. from the Meride Limestone, Ladinian, Besnasca/Cà del Frate, Viggiù, Italy. (1, 2) Paratype CMISN 1193: (1) details of pereiopods; (2) explanations. (3–5) Paratype CMISN 1203: (3) general view; (4) details of shield; (5) explanations. (6) Paratype CMISN 1180, details of the pleopods. (7–9) Paratype CMISN 1207: (7) details of the appendices; (8) general view; (9) counterpart. (10) Paratype CMISN 1195, general view. AP = antennular peduncle; CG = cervical groove; D = dactylus; E = eye; L = lamina; P = propodus; PCG = precervical groove; Pl = pleopods; Pr = pereiopods; S = antennal scale. Scale bars = 5 mm.

Holotype

CMISN 1179 (part and counterpart). Paratypes: CMISN 1180–1185, 1186 (part and counterpart), 1187 (part and counterpart), 1188 (part and counterpart), 1189–1191, 1192 (part and counterpart), 1193–1199, 1200 (part and counterpart), 1201 (part and counterpart), 1202–1206.

Diagnosis

Shield short; two or three thoracic segments exposed dorsally; two transverse grooves laterally visible and dorsally vanishing with their branches arcing axially toward the posterior margin of the shield. Antennal scale large, ovate to lanceolate, and setose; a rounded setose lamina, at least in males, is present on the third antennular segment. Dactylus in the pereiopodal endopods long and narrow with a nail on its distal end and strong spines throughout the interior margin. Telson with rounded apex; telson and uropods setose.

Occurrence

From early Ladinian to late Ladinian (Middle Triassic) on the base of the palynological content (Scheuring, Reference Scheuring1978) and isotopic dating (Stockar et al., Reference Stockar, Baumgartner and Condon2012). The type horizon is the middle Kalkschieferzone (upper member of the Meride Limestone) of late Ladinian age and the type locality is Besnasca/Cà del Frate (Viggiù, Varese, Italy).

Description

Body medium in length, excluding antennae and antennulae, sometimes slightly exceeding 35 mm (30 mm in the holotype, CMISN 1179; 15 mm in CMISN 1185; 19 mm in CMISN 1203; 33 mm in CMISN 1192; 36 mm in CMISN 1186).

The cephalothorax (including the antennal scale) is less than half the total body length (nearly 45%) and the shield is less than one-third of the total body length. Dorsally (where it is shortest for its concave posterior margin) it covers approximately two-thirds of the cephalothorax length. The tail fan is less than one-sixth of the total body length. The cephalothorax, tubular in shape, is approximately 15–17 mm long in mature specimens (e.g., 15 in CMISN 1179, 16 mm in CMISN 1192).

The shield generally shows dorsally some thoracic sternites (e.g., dorsally preserved specimens CMISN 1179, 1191, 1195, 1203, 1204). The shield is concavely curved along its posterior dorsal margin, and its lateral and posterior margins are free from the body. It was probably connected to the cephalothorax only in the anteriormost end. It is possibly produced in a short, wide, triangular rostrum, scarcely visible in only a few specimens (e.g., CMISN 1206, 1204). The shield anteriorly exhibits two transverse grooves. The most anterior one, the precervical groove, which is distinguishable in some specimens (e.g., CMISN 1186, 1179, 1203), is placed near the frontal margin (less than 1 mm from the frontal margin in the mature specimens). The second one, the cervical groove, is placed nearly 2 mm from the anterior margin in the mature specimens (e.g., 1.5 mm in CMISN 1203, 1.9 mm in CMISN 1179). Both these grooves are dorsally vanishing and their two branches arc axially toward the posterior margin of the shield, becoming longitudinal in orientation (e.g., CMISN 1186, 1179, 1191, 1192, 1203). The shield is very short, dorsally covering not more than thoracomeres (thoracic somites; T) 1–5, whereas at least T6–T8 are dorsally visible (e.g., CMISN 1191, 1203, 1206).

The endophragmal skeleton is exceptionally well preserved in several ventrally oriented specimens (e.g., CMISN 1204) or in dorsally oriented specimens that are partially decorticated. The posteriormost margin of each thoracic sternite is visible in some specimens as a robust ridge (e.g., CMISN 1191). Small anteriorly directed projections are present on these ridges immediately adjacent to the median margin of coxal holes at the median point (e.g., CMISN 1191). Some specimens (e.g., CMISN 1204) show well-preserved coxal holes, having a slightly compressed circular shape.

The pleon reaches approximately 15–19 mm in some mature specimens (e.g., CMISN 1179, 1192), the width rarely exceeding 4 mm. Pleomeres (pleonal somites; A) 1–4 are of equal length; A5 and A6 become progressively longer such that A6 is almost double the length of A1. Pleurae are present on A1–A5, absent on A6. Pleurae of A1 are rounded and laterally oriented; pleurae of A2–A6 also rounded by becoming progressively more posteriorly directed toward tail end of animal (e.g., CMISN 1186, 1192). Some specimens show traces of the abdominal muscles and of the gut (mid- and hindgut, e.g., CMISN 1185, 1194, 1203).

The antennules are biflagellate, and the antennular peduncle is composed of three basal segments. The first segment is the longest, approximately three times the second one (e.g., CMISN 1182, 1185, 1196, 1203). The third segment, pentagonal in outline, exhibits on the inner-distal margin of some well-preserved specimens (e.g., CMISN 1187, 1189, 1199, 1203) a lamina, possibly a masculine appendix, with a rounded and setose margin. It also exhibits, in the external frontal margin, two very long flagella nearly as long as the total body length. The antennal peduncle is not well visible because of the superimposition and compression of the elements and the most common dorsal orientation of the specimens; it is possibly shorter than the antennular peduncle, but with a flagellum more robust than the antennular ones. The antennal scales are large and cover the antennal and antennular peduncles (in the dorsally and ventrally oriented specimens, respectively). The antennal scales are ovate to lanceolate, with the longest axis longitudinal to the body, with a longitudinal median carina and a possible transverse suture on the distal rounded frontal margin (e.g., CMISN 1187, 1195). The outer margin is naked and thickened, the internal one setose (e.g., CMISN 1187). The eyes are bulbous and relatively large compared to the size of the whole body.

The distal segments of the pereiopodal endopods are often well preserved (e.g., CMISN 1193, 1197, 1200, 1207). They exhibit a long, narrow, and pointed dactylus with a furrow in the middle, strong spines throughout the interior margin (~9–12 on the mature specimen CMISN 1207) with the strongest on its distal end. The propodus is subrectangular (distally wider, nearly as long as the dactylus) while the carpus, hardly visible, is short (possibly half the length of the propodus). Merus, ischium, and preischium poorly visible. The pereiopodal exopods, hardly distinguishable on few specimens, possibly exhibit a single elongate flagellum. The pleopods, not always visible, are made up of a rectangular segment and two narrow, annulate rami, the anteriormost being more robust and longer than the other (e.g., CMISN 1180, 1181, 1192). They reach almost 3.5 mm in length in adults (e.g., CMISN 1192), and the posterior ones are slightly shorter than those near the anterior end of the pleon.

The tail fan is made up of the telson and a pair of biramous uropods. The exopods are elongate and triangular, exhibit a diaeresis, and are highly setose distally (e.g., CMISN 1185). The lobate endopods, highly setose distally, are slightly shorter than the exopods but are longer than the telson. Because of the superimposition and compression of the elements in the examined specimens, it is not clear whether the endopods have a diaeresis. The telson, distinctly visible in two exceptionally well-preserved specimens (CMISN 1179, 1206), is subrectangular and elongate with a rounded and highly setose distal end. The telson is also ornamented by a pair of curved longitudinal grooves, concave side facing laterally; in the holotype it reaches a maximum size of 2.5 mm in length and 1.3 mm in width at its base.

The body proportions change during growth (allometric growth), and most of the ontogenetic variations are related to enlargement of the shield and elongation of the pleon compared to the tail fan. The ratio of the shield to the tail fan is less than 1.4 in juvenile specimens (smaller individuals, less than 20 mm in size) and more than 1.6 in adult specimens (larger individuals, more than 30 mm in size).

Etymology

The name honors Cristina Lombardo (Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra ‘A. Desio,’ Università degli Studi di Milano) for her work on the Kalkschieferzone fauna.

Materials

Specimen CMISN 1207 from the Rio Vallone near Porto Ceresio and many hundred topotypes reposed in the same CMISN (without catalog number) from Besnasca/Cà del Frate (Viggiù, Varese, Italy). Hundreds of specimens from site D in the lower Kalkschieferzone in Val Mara, near the village of Meride (Mendrisio, Canton Ticino, Switzerland) and deposited in the MCSN were also examined. A few of the Val Mara specimens (from bed A and collected in 1996) were considered particularly informative, so they were given repository numbers (MCSN 3173–3184).

State of preservation

In these laminate limestones, the decay of crustacean skeletons is reduced, so even delicate structures such as pleopods and antennae are usually well preserved. As pointed out by Montagna et al. (Reference Montagna, Haug, Strada, Haug, Felber and Tintori2017), the very nice preservation of arthropods was probably due to the presence of microbial films at the bottom, quickly sealing the dead organism and allowing also quite common phosphatization of soft tissues in arthropods. However, as beds rich in Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. are recorded from a thick stratigraphic interval, size can vary from bed to bed, as for the overall preservation quality. Furthermore, the specimens are preserved in a variety of orientations, and this has a substantial impact on the outline and proportions of specimens.

Orientations vary from lateral to dorsoventral, with every intermediate; some specimens are twisted, with the main body regions seen in different orientations. This confirms that the animals were rather delicate and the exoskeleton was poorly sclerotized and susceptible to postmortem distortion.

Remarks

Benton (Reference Benton1993) stated the synonymy for the two species erected by Bill (Reference Bill1914) in the genus Schimperella: S. beneckei and S. kessleri. Gall (Reference Gall1971) had previously hinted at this suggestion, noting that the differences between the two species, in terms of the degree of cephalothorax cover provided by the shield, may be explained by taphonomical deformations. The uncertain status of S. kessleri was discussed also by Schram (Reference Schram1986) and Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001); the correct status of this species could only be definitively defined by examination of the original materials, but it seems to be missing (fide Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001). In agreement with Feldmann et al. (Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie and Maguire2016), the original illustrations of S. kessleri (Bill, Reference Bill1914, pl. 16, figs. 3, 4) suggest that this species may be the female counterpart of S. beneckei. Regardless, there are few similarities between Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. and Schimperella beneckei. In addition to the characters of generic rank, Vicluvia lombardoae differs from Schimperella in the dactylus, which is longer, sharp, and armed with strong spines in Vicluvia.

The specimens figured and identified by Bürgin et al. (Reference Bürgin, Eichenberger, Furrer and Schanz1991) as coleoidean arms (p. 102, fig. 2) and S. beneckei (p. 103, fig. 3) belong to Vicluvia lombardoae because they show the diagnostic characters of the armed dactylus and rounded telson.

The taxonomic assignment of the most recent species attributed to Schimperella, S. acanthocercus Taylor, Schram, and Yan-Bin, Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001, based on specimens from the Ladinian Falang Formation (southwestern China), will be revised (personal communication, A. Tintori, 2019) in light of new, better-preserved specimens recently collected from the same unit in both the type locality and the Nimaigu (Wusha of Xingyi) excavation site (personal observation, A.T., 2016–2017). The specimens studied by Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Schram and Yan-Bin2001) seem not preserved enough for a confident generic assignment considering the diagnostic relevance of the shield shape and precervical and cervical grooves in Schimperella, Yunnannocopia, and Vicluvia. There are only a few resemblances between Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. and Schimperella acanthocercus. The antennular peduncle of S. acanthocercus is simpler than that of Vicluvia lombardoae and does not exhibit the masculine process on the third peduncular segment.

In addition to the characters of the more generic rank, Vicluvia lombardoae differs from Yunnanocopia grandis Feldmann et al., Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017 and Y. longicauda Feldmann et al., Reference Feldmann, Schweitzer, Hu, Huang, Zhou, Zhang, Wen, Xie, Schram and Jones2017 in the longer dactylus, which is sharp and armed with strong spines.

Discussion

Crustaceans are among the least-known invertebrates from the Middle Triassic rocks of the studied area. The first crustacean reported from the Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio was the penaeid Antrimpos mirigiolensis Etter, Reference Etter1994. The same unit, outcropping at Sasso Caldo near Besano (Italy), provided thylacocephalans (Affer and Teruzzi, Reference Affer and Teruzzi1999).

A new macruran decapod, Meridecaris ladinica Stockar and Garassino, Reference Stockar and Garassino2013, was described from the lowermost part of the upper Meride Limestone, from an interval informally introduced as ‘Sceltrich beds’ by Stockar et al. (Reference Stockar, Adatte, Baumgartner and Föllmi2013). In the same paper, Stockar and Garassino (Reference Stockar and Garassino2013) reported the presence of two further specimens of natant decapods from the Besano Formation at Sasso Caldo site; they are still undescribed.

In the youngest fossiliferous unit of the Monte San Giorgio, the Kalkschieferzone, besides ostracods and the conchostracan Laxitextella (Tintori and Brambilla, Reference Tintori and Brambilla1991; i.e., Palaeolimnadia sp. in Tintori, Reference Tintori and Robba1990c), only the mysidacean (s.l.) Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. is a common crustacean (Figs. 4–6).

Until now, only one specimen of decapod was reported from the Kalkschieferzone and tentatively assigned by Larghi and Tintori (Reference Larghi and Tintori2007) to the ‘wastebasket genus’ Antrimpos Münster, Reference Münster1839.

The accumulation of layers of mass mortality of Vicluvia lombardoae n. gen. n. sp. could reflect normal population dynamics, corresponding to seasonal variations in physical factors and/or in reproductive cycles. It is important to keep in mind that these surfaces are usually devoid of any other organic remains, no fishes or conchostracans having been recorded (personal observation, A.T., 1996–2003). Fluctuations in environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, oxygen, and phytoplankton biomass influence the seasonal patterns of variation in populations of many modern crustaceans. Mysidaceans living in estuarine transitional environments show temporal variations in population structure, which have a salinity-related reproductive significance (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Jones and Greenwood1989; Azeiteiro et al., Reference Azeiteiro, Jesus and Marques1999, Reference Azeiteiro, Fonseca and Marques2001). Although reproduction seems continuous throughout the year in many species, some observations show peaks in connection with variations of salinity (Azeiteiro et al., Reference Azeiteiro, Jesus and Marques1999, Reference Azeiteiro, Fonseca and Marques2001). Sudden seasonal increase in freshwater supply decreases salinity, whereas high temperatures in the dry months increase it; during these seasonal changes, mature mysids disappear from the population as their progeny develop (Azeiteiro et al., Reference Azeiteiro, Jesus and Marques1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Lombardo, who was for many years field director in the fossil localities of Cà del Frate and Val Mara and responsible for collecting the large number of specimens here examined. The MSNIO (now CMISN) and the MCSN in Lugano supported the excavation in the Cà del Frate and Val Mara sites, respectively. G. Teruzzi allowed comparison with the material stored in the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano. We thank the referees C. Schweitzer and J. Haug for careful reading of the manuscript and for their valuable comments. We thank J. Jin, T. Wappler, and J. Kastigar for the editorial and stylistic revision of the manuscript and E. Barnes for the English revision. We also acknowledge all the people who helped during the fieldwork.