Introduction

The Permian-Triassic mass extinction was the most severe extinction event in Earth's history, causing more than 90% of marine organisms to become extinct (Erwin, Reference Erwin1994; Song et al., Reference Song, Wignall, Tong and Yin2013). Brachiopoda were among the most abundant benthos in the Paleozoic ocean, but they were no longer the dominant group of benthos after the Permian-Triassic crisis (Sun and Shen, Reference Sun, Shen, Rong and Fang2004; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho and George2005b; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Zhang, Li, Mu and Xie2006a; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ton, Song, Luo, Huang and Xiang2015; Carlson, Reference Carlson2016; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Shen, Shi, Fan, Zhang, Qiao and Zeng2016). The Early Triassic brachiopods, except the surviving Permian-type brachiopods from the Permian-Triassic boundary and early Griesbachian (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho and George2005a, Reference Chen, Kaiho and Georgeb; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Shen, Shi, Fan, Zhang, Qiao and Zeng2016), are rare worldwide (Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, Reference Dagys1993; Ager, Reference Ager1988; Ager and Sun, Reference Ager and Sun1988; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho and George2005b; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Shen, Shi, Fan, Zhang, Qiao and Zeng2016), with only 18 species (including seven undefined species) recorded in Griesbachian strata (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a, Reference Bittnerb; Newell and Kummel, Reference Newell and Kummel1942; Dagys, Reference Dagys1965, Reference Dagys1974; Shen and He, Reference Shen and He1994; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shi and Kaiho2002; F.Y. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Dai and Song2017; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Song, Wignall, Jia, Bai, Wang, Chen and Tian2018), four species (including one undefined species) recorded in Dienerian strata (Dagys, Reference Dagys1965; Hoover, Reference Hoover1979; Shigeta et al., Reference Shigeta, Zakharov, Maeda and Popov2009; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Wasmer and Bucher2013; Zakharov and Popov, Reference Zakharov and Popov2014), and 36 species (including seven undefined species) recorded in Olenekian strata (Girty, Reference Girty1927; Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Feng and Jiang, Reference Feng and Jiang1978; Hoover, Reference Hoover1979; Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Hu and Chen1981; Chen, Reference Chen1983; Xu and Liu, Reference Xu, Liu, Yang, Xu, Wu, He, Liu and Yin1983; Iordan, Reference Iordan1993; Shigeta et al., Reference Shigeta, Zakharov, Maeda and Popov2009; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Wasmer and Bucher2013, Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Brayard, Nützel, Bylund, Jenks, Vennin, Olivier and Bucher2014; Zakharov and Popov, Reference Zakharov and Popov2014; Popov and Zakharov, Reference Popov and Zakharov2017; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Xu, Qiao, Rong, Jin, Shen and Zhan2017; Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019). However, 26 species (including seven undefined species) of Early Triassic brachiopods have been reported in Spathian strata (Hoover, Reference Hoover1979; Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979; Shigeta et al., Reference Shigeta, Zakharov, Maeda and Popov2009; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Wasmer and Bucher2013, Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Brayard, Nützel, Bylund, Jenks, Vennin, Olivier and Bucher2014; Zakharov and Popov, Reference Zakharov and Popov2014; Popov and Zakharov, Reference Popov and Zakharov2017; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Xu, Qiao, Rong, Jin, Shen and Zhan2017; Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019).

The paleogeographical distribution of Early Triassic brachiopods is heterogenous between the two hemispheres. Brachiopods were more widely distributed in the northern hemisphere than in the southern hemisphere, and a total of 45 species (including 18 indeterminant species) were distributed from the low latitude to high latitude regions in the northern hemisphere throughout the Griesbachian to Spathian. These species include six from South China (Feng and Jiang, Reference Feng and Jiang1978; Shen and He, Reference Shen and He1994; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shi and Kaiho2002; F.Y. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Dai and Song2017), 10 species from the western USA (Girty, Reference Girty1927; Newell and Kummel, Reference Newell and Kummel1942; Hoover, Reference Hoover1979; Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Wasmer and Bucher2013, Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Brayard, Nützel, Bylund, Jenks, Vennin, Olivier and Bucher2014), five species from Romania (Iordan, Reference Iordan1993; Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019), three species from the southern Qilian Mountains of China (Xu and Liu, Reference Xu, Liu, Yang, Xu, Wu, He, Liu and Yin1983), seven species from Kazakhstan (Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Zakharov and Popov, Reference Zakharov and Popov2014), one species from northwest Caucasus (Dagys, Reference Dagys1974), and 20 species from South Primorye of Russia (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899b; Dagys, Reference Dagys1965, Reference Dagys1974; Shigeta et al., Reference Shigeta, Zakharov, Maeda and Popov2009; Zakharov and Popov, Reference Zakharov and Popov2014; Popov and Zakharov, Reference Popov and Zakharov2017). However, only six species have been reported in the southern hemisphere, including three species from Lhasa in China (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Hu and Chen1981), one species from Spiti in India (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a), and two species from southern Tibet in China (Chen, Reference Chen1983). Notably, the internal structures of most of these brachiopods from the southern hemisphere have not been well studied. Investigations regarding Early Triassic brachiopods in the southern hemisphere may give us a better understanding of the evolution, ecology, and paleobiogeography of the Early Triassic.

In this study, we report a new Early Triassic (late Dienerian–late Smithian) brachiopod fauna from the middle-upper part of the Kangshare Formation at the Selong section in southern Tibet. One new genus and three new species were systematically described. In addition, we studied the internal structures and ontogeny of these species in detail. Our findings may fill a gap in our knowledge of brachiopod biogeography.

Geological setting

The Selong section (84°49′E, 28°39′N) is located in Selong Village, Nyalam County, in southern Tibet, China (Fig. 1.1–1.3), and was previously proposed as a candidate of the Global Stratotype Section and Point of the Permian-Triassic boundary (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Shen, Zhu, Mei, Wang and Yin1996; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). A detailed biostratigraphic framework was constructed at Selong using conodonts and ammonoids (Wang and He, Reference Wang and He1976; Yao and Li, Reference Yao and Li1987; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989; Orchard et al., Reference Orchard, Nassichuk and Rui1994; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang1995; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Shen, Zhu, Mei, Wang and Yin1996; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Cao, Henderson, Wang, Shi, Wang and Wang2006b; L.N. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wignall, Sun, Yan, Zhang and Lai2017; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). In addition, sedimentology (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Shen, Zhu, Mei, Wang and Yin1996; Garzanti et al., Reference Garzanti, Nicora and Rettori1998; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Song, Woods, Dai and Wignall2019), geochemistry (Li et al., Reference Li, Song, Algeo, Wignall, Dai and Woods2018; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018), and Permian-Triassic mass extinction patterns have also been studied (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Cao, Henderson, Wang, Shi, Wang and Wang2006b; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018).

Figure 1. (1) Geological map of southern Tibet, China, modified from Li et al. (Reference Li, Song, Woods, Dai and Wignall2019). (2) Geological map of Selong area, showing the studied section. (3) Field view of Selong section. C1–2 n = Lower and middle Carboniferous Naxing Formation; P1 j = lower Permian Jilong Formation; P2–3 s = middle and upper Permian Selong Group; T1–3 t = Lower and Upper Triassic Tulong Group; J2 l = Middle Jurassic Lagongtang Formation; Qp, Pleistocene; Qh, Holocene.

The Selong section exposes a complete stratigraphic sequence from the uppermost Permian to the basal upper Lower Triassic strata (Fig. 2). There may be an unconformity between the Selong Group below the Permian-Triassic boundary and the Kangshare Formation above the boundary (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). The lower part of the Selong Group consists of 24 m thick bioclastic limestone and dark silty shales, and the upper part consists of massive crinoid grainstone beds that contain abundant brachiopods, crinoids, bryozoans, and corals (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2000, Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2001, Reference Shen, Cao, Henderson, Wang, Shi, Wang and Wang2006b; Sakagami et al., Reference Sakagami, Sciunnach and Garzanti2006; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). The lowermost part of the Kangshare Formation is characterized by brown dolomitized crinoidal packstone and thick-bedded packstone beds (i.e., Waagenites Bed and Otoceras Bed), yielding brachiopods, corals, bryozoans, ammonoids, ostracodes, foraminifers, and calcareous sponges. The Permian-Triassic boundary is indicated by the first occurrence of the conodont Hindeodus parvus (Kozur and Pjatakova, Reference Kozur and Pjatakova1976) at the bottom of the Otoceras Bed (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2000, Reference Shen, Cao, Henderson, Wang, Shi, Wang and Wang2006b; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). The overlying strata consist of khaki thin- to medium-bedded packstone/wackestone beds, which are dominated by abundant ammonoids, brachiopods, and bivalves. The middle portion of the Kangshare Formation is a set of black shales, in which there are two packstone/wackestone layers. The overlying strata are dominated by reddish to yellowish and ferruginous wackestone layers consisting of abundant brachiopods and a small number of ammonoids. This part includes gray and thin- to medium-bedded packstone/wackestone carbonates that are rich in ammonoids, bivalves, and brachiopods. Farther up, another set of black shales crops out. Above the shale strata are 2 m thick packstone/wackestone beds, which constitute the uppermost part of the Lower Triassic.

Figure 2. Lithology of the Selong Group and the Kangshare Formation at Selong section, showing the distribution of brachiopods. Conodont biozones and part of ammonoid beds modified from Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989) and An et al. (Reference An, Zhang, Zhu, Zhang and Yuan2018). Spa. = Spathian.

A high-resolution biostratigraphic framework was established based on the conodont and ammonoid records from the Selong section (Yao and Li, Reference Yao and Li1987; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989; Orchard et al., Reference Orchard, Nassichuk and Rui1994; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang1995; An et al., Reference An, Zhang, Zhu, Zhang and Yuan2018). Occurrences of the conodont Neospathodus pakistanensis Sweet, Reference Sweet1970 (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989; Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang1995; An et al., Reference An, Zhang, Zhu, Zhang and Yuan2018) and ammonoid Koninckites vetustus Waagen, Reference Waagen1895 (Figs. 2, 3) in Beds 29–33 indicate a late Dienerian age. The conodont Neospathodus waageni Sweet, Reference Sweet1970, and ammonoid Kashmirites occur in Beds 35–42, suggesting an early Smithian age (Brühwiler et al., Reference Brühwiler, Bucher, Brayard and Goudemand2010) (Figs. 2, 3). The overlying brachiopods in Beds 67–70 co-occurred with the ammonoid Anasibirites, indicating their occurrence during the late Smithian age (Wang and He, Reference Wang and He1976; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Rui, Wang, Liao, He, Sun, Li, Zhao, Xu, Li and Jiang1989). Based on the conodont and ammonoid data mentioned above, the abundant brachiopods in Beds 29, 35–42, and 67–70 (Fig. 2) occurred during the late Dienerian–late Smithian age.

Figure 3. Ammonoids from the Kangshare Formation from Selong section, southern Tibet. (1, 2) Koninckites vetustus Waagen, Reference Waagen1895 (SL-AMM-001); (3) Kashmirites sp. indet. (SL-AMM-002).

Materials and methods

There were 825 brachiopod specimens collected from the Kangshare Formation in the Selong section. The external features, internal structure, and ontogeny of these specimens have been systematically studied. The Selong fauna contains three brachiopod species from three genera: Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. (612 specimens), Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. (181 specimens), and Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. (32 specimens). Despite these brachiopods being extremely small, most of them were completely preserved. However, the Early Triassic brachiopods and some Middle Triassic brachiopods were difficult to identify because of their similarities in both their internal and external features. In order to accurately identify the Selong brachiopods, the external and internal characteristics were studied in detail, and the ontogenetic characteristics of each species were fully considered. Moreover, a comprehensive review of related species was carried out, focusing on the characteristics of intraspecific variation and individual development. The external features of juveniles to adults of each species in a large number of specimens were carefully studied. All specimens were photographed using a Canon 6D Mark II camera with a macro lens EF 100 mm f/2.8. To accurately assess the characteristics of the internal structures, 17 specimens (10 specimens of Piarorhynchella selongensis n. sp., four specimens of Schwagerispira cheni n. sp., and three specimens of Selongthyris plana n. gen. n. sp.) were selected to grind serial sections. The minimal distance among serial sections is 0.01 mm. There were 414 serial sections produced, each of which was observed and photographed under a Leica S8 APO stereo microscope.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All described specimens in this study are deposited in the Yifu Museum of China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China (collection number CUG SL-A-001-SL-C-825).

Systematic paleontology

The classification of the Brachiopoda adopted herein follows the revised Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part H (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Brunton, Carlson, Alvarez, Blodgett and Kaesler2002, Reference Williams, Brunton, Carlson, Baker, Carter and Kaesler2006).

Order Rhynchonellida Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1949

Superfamily Norelloidea Ager, Reference Ager1959

Family Norellidae Ager, Reference Ager1959

Subfamily Holcorhynchellinae Dagys, Reference Dagys1974

Genus Piarorhynchella Dagys, Reference Dagys1974

Type species

Piarorhynchella mangyshlakensis Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Karatauchik Range, Dolnapa Well, Mangyshlak; Olenekian.

Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen new species

Figures 4–12

- Reference Chen1983

Nudirostralina subtrinodosi; Chen, p. 155, pl. 1, fig. 2.

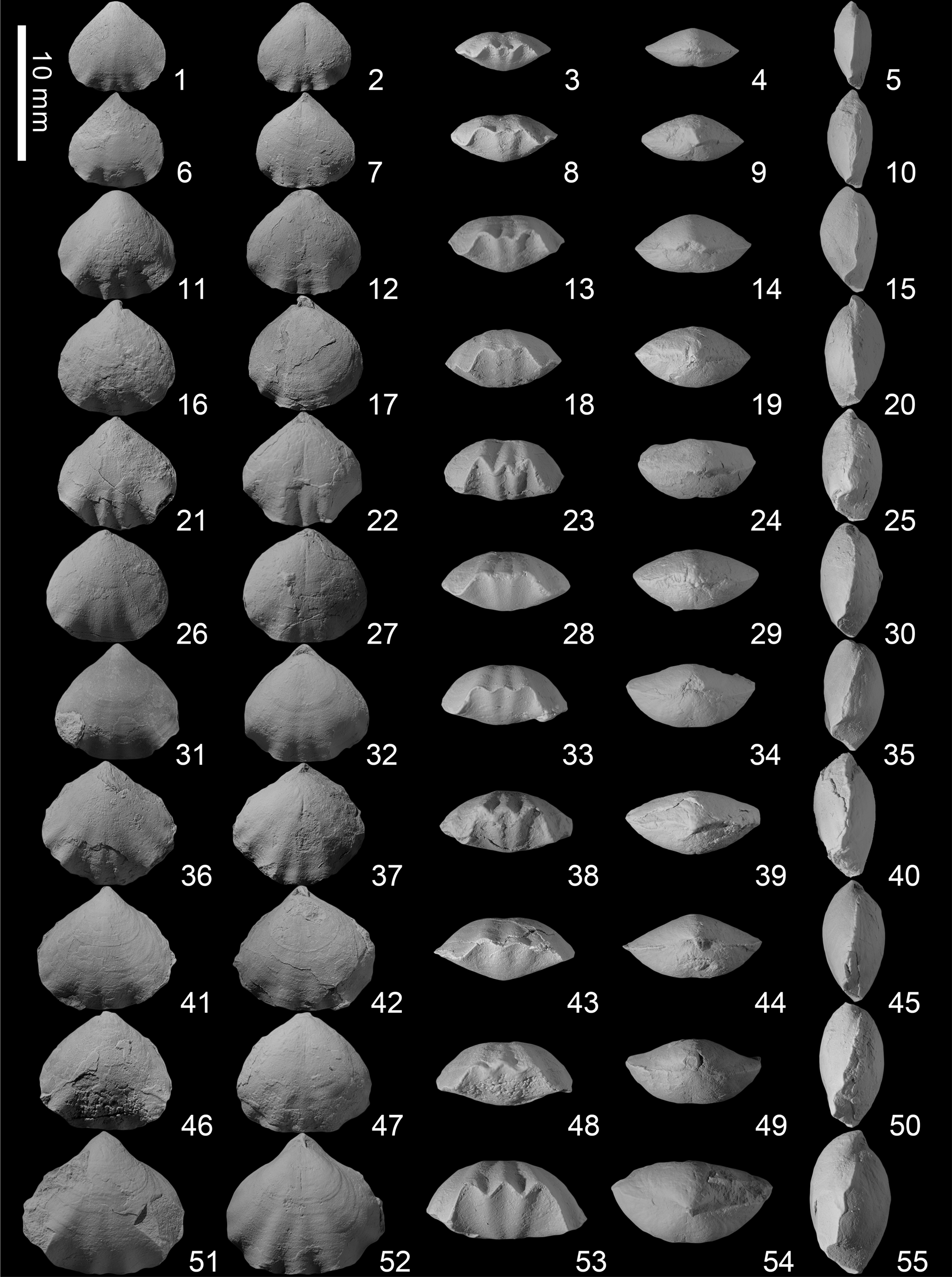

Figure 4. Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each articulated shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, and lateral views. (1–5) SL-A-001; (6–10) SL-A-002; (11–15); (16–20) SL-A-004; (21–25) SL-A-005; (26–30) SL-A-006; (31–35) SL-A-007; (36–40) SL-A-008; (41–45) SL-A-009; (46–50) SL-A-010; (51–55) SL-A-011; (56–60) SL-A-012; (61–65) SL-A-013; (66–70) SL-A-014; (71–75) SL-A-015; (76–80) SL-A-016; (81–85) SL-A-017; (86–90) SL-A-018.

Figure 5. Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each articulated shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, and lateral views. (1–5) SL-A-019; (6–10) SL-A-023; (11–15) SL-A-026; (16–20) SL-A-027; (21–25) SL-A-030; (26–30) SL-A-029; (31–35) SL-A-032; (36–40) paratype SL-A-033; (41–45) paratype SL-A-034; (46–50) syntype SL-A-035.

Figure 6. Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, lateral views from the right to left side. (1–5) SL-A-036; (6–10) SL-A-039; (11–15) SL-A-041; (16–20) SL-A-043; (21–25) SL-A-044; (26–30) SL-A-046; (31–35) SL-A-047; (36–40) paratype SL-A-052; (41–45) SL-A-050; (46–50) SL-A-051; (51–55) syntype SL-A-053.

Figure 7. Ontogenesis of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. showing two different growth patterns.

Figure 8. (1) Scatter plot of length/width of 612 articulated shells of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. (2) Scatter plot of length/thickness of the same. The red dotted line represents the trend line.

Figure 9. (1) Scatter plot of length/a/width of 612 articulated shells of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. (2) Scatter plot of length/b/width of the same. (3) Scatter plot of length/h/thickness of the same. (4) Frequency histogram of h/thickness in (3).

Figure 10. Serial sections of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. based on specimen SL-A-SS-002. The distance from the ventral beak to individual section is given in mm. Ventral valve upward. Sections continue in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Serial sections of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. based on specimen SL-A-SS-002. Sections continued from Figure 10.

Figure 12. Reconstructed dorsal internal view of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. based on the serial sections in Figures 10, 11. Abbreviations: C. = Crura; D. p. = dental plate; D. v. = dorsal valve; H. t. = hinge teeth; I. h. p. = inner hinge plate; I. h. r. = inner hinge ridge; M. s. = median septum; O. h. p. = outer hinge plate; O. h. r. = outer hinge ridge; So. = socket; Sp. = septalium; V. v. = ventral valve.

Syntypes

Specimens SL-A-035 (Fig. 5.46–5.50) and SL-A-053 (Fig. 6.51–6.55), from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Paratypes

Specimens SL-A-033 (Fig. 5.36–5.40), SL-A-034 (Fig. 5.41–5.45), and SL-A-052 (Fig. 6.36–6.40), from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Diagnosis

Small-sized biconvex and subpentagonal shells; width slightly larger than the length, maximum width located in the anterior third. Fold and sulcus moderately developed. Posterior smooth, short plicae near anterior. Plicae range from 2–3 plica in the dorsal fold, 1–2 in the ventral sulcus, and 1–2 poorly developed plicae on lateral flanks. Ventral valve with strong hinge teeth. Median septum absent. Dorsal valve with well-developed and steady median septum up to half length of shell in size. Septalium distinct but shallow. Crural bases distinct, subtriangular in shape. Crura raduliform.

Occurrence

Kangshare Formation of late Dienerian–late Smithian age, Selong section, southern Tibet, China.

Description

Subpentagonal in outline. Small size, 1.88–10.06 mm long, 1.73–11.21 mm wide; width slightly larger than the length (Fig. 8.1); maximum width reaches three-thirds of length anteriorly. Bioconvex in profile, the convexity of the dorsal valve slightly greater than that of the ventral valve, but shell flat; 0.55–6.32 mm thick, maximum thickness lies in the mid-length. Postero-lateral margin straight; anterior margin straight. Hinge line short and curved, much shorter than the maximal width. Fold and sulcus only appear anteriorly. Anterior commissure uniplicate to bisulcate. Trapezoidal linguiform extension short and slightly curved; beveled at low or medium angle to the plane of commissure. Shell smooth posteriorly, short and weak plicae near anterior margin.

Ventral valve mildly convex and most convex approximately in the middle of the shell. Umbo mildly convex, middle part flat, anterior part extends forward and slightly bent. Apical angles 75–113°. Beak very distinct, small, pointed, slightly curved. Beak ridges round and curved, slightly convex to the plane of symmetry. Interarea short and narrow, but distinct. Foramen tiny, hypothyrid, oval or rounded triangular in shape. Deltidial plates disjunct. Sulcus develops from the middle of the shell, extremely shallow and flat posteriorly, and gradually widens towards anterior and starts to appear at one-fourth to one-sixth of the length anteriorly. Bottom of the sulcus flat and very shallow. Sulcus extends forward and slightly curved, forming trapezoidal linguiform extension, and never perpendicular to the commissure plane, forming geniculate commissure. Width of base accounts for 0–85% of the maximum width (Fig. 9.2). Width of top edge accounts for 0–68% of the maximum width (Fig. 9.1). Height of trapezoidal linguiform accounts for 0–95% of the maximum thickness (Fig. 9.3, 9.4). One to two plicae on the sulcus.

Dorsal valve mildly convex, most convex approximately in the middle of the shell. Umbo strongly curved, middle and anterior part slightly bent forward at the same degree. Beak strongly incurved and embedded into the ventral valve. Median sulcus very weak and shallow; appears from umbonal region where it is extremely weak, then extends forward and is replaced by the fold when there are three plicae on the fold, or continuously extends to the anterior region, forming shallow interspace between the two plicae when there are two plicae on the fold. Dorsal median fold moderately developed, begins in the mid-length, and becomes obvious on one-third to one-fourth of anterior area where one or three plicae present.

Shells covered by dense concentric growth lines. Short plicae only developed in the anterior region, about one-third to one-fourth of anterior area. Plicae blunt, rounded triangular in cross section. One to two identical plicae on the sulcus and linguiform extension. Fold bears two to three identical plicae. Two arrangements of plicae in matured specimens, either three plicae on fold with two in sulcus (3/2, 50%) or two plicae on fold and one on sulcus (2/1, 50%). Plicae in the lateral flanks generally undeveloped, especially those closer to the posterolateral margin. One to two plicae only develop on lateral flanks. First lateral plicae appear at one-third of the length anteriorly, located at the two sides of the fold and sulcus of both valves. Second lateral plicae much wider, weaker, and shorter than any other, and appear only at the outermost lateral margin occasionally. Small bends next to the two lateral plicae only appear at the lateral commissure and never form real plicae on the shell surface in a few of the largest specimens.

Ventral delthyrial cavity oval to round. Pedicle collar absent. Dental plates thin and distinct, always straight, but the dip orientation varies. Dental plates nearly parallel, to ventrally convergent. Hinge teeth very strong with a large base and bifid; denticula absent or not developed. Sockets in dorsal valve well developed, mildly deep, with wide and flat bottom. Inner socket ridges and the outer socket ridges bend slightly toward each other; inner socket ridges incline toward medial. Hinge plates thin but very distinct, narrow posteriorly, wide anteriorly. Outer hinge plates nearly straight. Inner hinge plates slightly incline to the middle, connect to the median septum, forming distinct U- or V-shaped septalium, and become wider and deeper anteriorly. Median septum extends to half of length or more of the dorsal valve. Crural bases very distinct and triangular. Crura short, raduliform, nearly straight in the posterior area, symmetrically extend anteroventrally, and hook-like. Crura subtriangular, becoming increasingly thinner towards anterior and eventually becoming curved, subvertical plates in serial sections.

Etymology

After the Selong section, from which the specimens were collected.

Material

A total of 612 complete specimens collected from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation. Of these, 10 specimens were sectioned (SL-A-SS-001, SL-A-SS-002 [Figs. 10, 11], SL-A-SS-003, SL-A-SS-004, SL-A-SS-005, SL-A-SS-006, SL-A-SS-007, SL-A-SS-008, SL-A-SS-009, SL-A-SS-010) and 39 selected specimens were photographed.

Remarks

Some rhynchonellid species, attributed to nine genera (Piarorhynchella Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Abrekia Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Nudirostralina Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966; Paranorellina Dagys, Reference Dagys1974; Laevorhynchia Shen and He, Reference Shen and He1994; Meishanorhynchia Chen and Shi in Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shi and Kaiho2002; Lichuanorelloides F.Y. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Dai and Song2017; Lissorhynchia Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966; Prelissorhynchia Xu and Grant, Reference Xu and Grant1994), share many external (especially in juvenile stages) and internal features and show relatively large intraspecific variation. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to ontogeny and intraspecific variation in order to identify Triassic brachiopod species accurately, rather than just focusing on characteristic external features. As for internal structures, crura should be regarded as among the most important and valuable characteristics for classification because their features are relatively complex and generally consistent (Ager, Reference Ager and Moore1965; Ager et al., Reference Ager, Childs and Pearson1972; Shi and Grant, Reference Shi and Grant1993; Manceñido and Owen, Reference Manceñido, Owen, Copper and Jin1996, Reference Manceñido and Owen2001; Savage et al., Reference Savage, Manceñido, Owen and Kaesler2002; Manceñido and Motchurova-Dekova, Reference Manceñido and Motchurova-Dekova2010).

Considering that the specimens, which were collected in contemporary strata from adjacent Tulong section (Chen, Reference Chen1983) and Selong section (this study) in southern Tibet, China, have similar external features, we judge that they should belong to the same species. However, Chen (Reference Chen1983) identified these specimens as Nudirostralina subtrinodosi Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966. No description or discussion of these specimens were presented in the article (Chen, Reference Chen1983). In addition, the external and internal features of these specimens are very different from those of N. subtrinodosi (see below). As a result, we re-identified these specimens.

Piarorhynchella mangyshlakensis Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, the type species of the genus Piarorhynchella Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, can be distinguished from P. selongensis n. sp. by the outline. The former species has a much wider shell (width significantly greater than length) than the latter species. The profile of P. mangyshlakensis is more convex than P. selongensis n. sp. Piarorhynchella mangyshlakensis shows a flat dorsal valve and a convex ventral valve. As for P. selongensis n. sp., its dorsal valve is slightly more convex than the ventral valve. Piarorhynchella mangyshlakensis has a distinct and high trapezoidal linguiform extension, which is beveled at a high angle toward the anterior commissure. The height of the trapezoidal linguiform extension is equal to the thickness (Fig. 13). However, these features of linguiform extension are all different from P. selongensis n. sp. (Figs. 9.3, 9.4, 13). Compared to that in P. selongensis n. sp., P. mangyshlakensis has more-rounded plicae in the anterior. In addition, P. mangyshlakensis has three forms of plicae, namely 4/3 (Dagys. Reference Dagys1974, pl. 32, fig. 9, 7%), 3/2 (Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, pl. 32, fig. 8, 58%), and 2/1 (Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, pl. 32, fig. 10, 35%). However, P. selongensis n. sp. has only two types of plicae with similar proportions. In terms of internal structures, P. mangyshlakensis shows thick, massive, and narrow hinge plates (Fig. 13), including thickened and nearly horizontal outer hinge plates, and a narrow and deep septalium. However, P. selongensis n. sp. has much wider and thinner hinge plates (Figs. 10, 11, 13), horizontal or slightly oblique outer hinge plates, and a shallow and wide septalium. The crura of P. mangyshlakensis were identified as calcariform by Dagys (Reference Dagys1974). However, the distal ends of the crura present two lines inclined toward the symmetrical plane; no long hooks or expanded heads pointing to the dorsal valve were found. Thus, the crura of P. mangyshlakensis should be identified as raduliform (Fig. 13), that is, a short and strongly curved rod-like structure that projects toward the ventral valve. Therefore, the crura are the same in the two species.

Figure 13. Comparison of the main external and internal features in all the species of Piarorhynchella. The figures of crura are shown by the distal ends in serial sections.

Piarorhynchella trinodosi (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890), a widespread species in Europe (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890; Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969; Pálfy, Reference Pálfy1988; Urošević et al., Reference Urošević, Radulović and Pesić1992), has wide intraspecific variation of the shell shapes (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890; Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969; Pálfy, Reference Pálfy1988). Thus, comparison of the two species must consider ontogeny and intraspecific variation. Typical P. trinodosi shows high linguiform extensions (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 32, figs. 17–28; Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969, pl. 34, figs. 1–7), which bevel at a high angle (sometimes approximately vertical) to the anterior commissure, forming a geniculate anterior portion that becomes the thickest part of the shell (Fig. 13). Meanwhile, Piarorhynchella trinodosi var. latelinguata (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890) and Piarorhynchella trinodosi cf. toblochensis (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890) have low and wide linguiform extensions (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 32, figs. 29–32). However, nearly all mature specimens of P. selongensis n. sp. have less-developed linguiform extensions (Figs. 13, 9.3, 9.4). Because of intraspecific variation, P. trinodosi has a biconvex to geniculately biconvex profile. Nevertheless, the profile of P. selongensis n. sp. is only biconvex. The dominant types of plicae distribution of these two species are different. Two/one is the dominant form in Italian (70–98%, Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969), Alpine, and Hungarian specimens of P. trinodosi (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890). However, the two types of P. selongensis n. sp. have balanced proportions. Piarorhynchella trinodosi and P. selongensis n. sp. show significant differences in terms of ontogeny. The growth pattern of P. trinodosi attests to an ‘early maturity.’ Many structures already exist in most juvenile specimens, including the convex ventral valve, distinct linguiform extension (the height of the linguiform extension is approximately equal to the maximum thickness), an obvious sulcus, and a fold (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 32, figs. 17–20, 24, 33; Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969; our personal collections). However, the juvenile specimens of P. selongensis n. sp. have a weak sulcus and fold or only have a low linguiform extension (Figs. 4, 7). The growth process of plicae is also different between two species. In juvenile of P. selongensis n. sp., the middle plica is smaller and lower than others because of the existence of a narrow sulcus in the middle of the dorsal valve (Figs. 4–6). However, in P. trinodosi, there is no sulcus on the dorsal valve, so the three plicae are of different sizes with the middle one always larger and higher than the other two (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 32, figs. 28, 29, 31; Gaetani, Reference Gaetani1969, pl. 34, fig. 3). It should be noted that the development of the lateral plicae of P. trinodosi is not consistent between original description (very weak, only pronounced in shell margin; Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, p. 14–15) and plates (long and distinct in lateral flanks; Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 32, figs. 17, 19–23, 25–28, 34). According to Gaetani (Reference Gaetani1969, p. 500, pl. 34, figs. 1–7), in combination with our personal specimens (collected in the same location), it was found that the lateral plicae were indeed very weak, and most specimens had only one real plica on the lateral shell surface next to the sulcus and fold on each side. Therefore, the lateral plicae in these two species share the same features.

Piarorhynchella triassica (Girty, Reference Girty1927), a common species from the western USA (Girty, Reference Girty1927; Alexander, Reference Alexander1977, Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979), is elongate in comparison to P. selongensis n. sp. P. selongensis n. sp. is only slightly elongate in small shells, but becomes wider than long in larger shells (Figs. 4–6, 8.1). In profile, P. triassica is slightly to strongly dorsibiconvex, and the thickest part is located at the anterior of the shell. Nevertheless, P. selongensis n. sp. is biconvex, and the maximum thickness of P. selongensis n. sp. is situated in the middle of the shell. The characteristics of linguiform extension have obvious differences between the two species (Figs. 9.3, 9.4, 13). P. triassica has a long and high trapezoidal linguiform extension, which bevels at a high angle to the anterior commissure. The height of the linguiform extension is approximately equal to the thickness (Fig. 13). P. triassica always shows a narrow, high, and strongly inclined fold, both sides of which are strongly tilted. However, P. selongensis n. sp. has a wide and low dorsal fold. In light of the description by Perry and Chatterton (Reference Perry and Chatterton1979), P. triassica (1–3 plicae on the ventral sulcus and 2–4 plicae on the dorsal fold) has more plicae than P. selongensis n. sp. (1–2 plicae on the dorsal sulcus and 2–3 plicae on the ventral valve).

Piarorhynchella tazawai Popov in Popov and Zakharov, Reference Popov and Zakharov2017 (9–14 mm long, 15 mm wide), which was first identified by Popov and Zakharov (Reference Popov and Zakharov2017), is larger than P. selongensis n. sp. (10.06 mm long, 11.21 mm wide). P. tazawai is elongate in comparison to P. selongensis n. sp. Length of adults of P. selongensis n. sp. is usually less than the width. The fold and sulcus of P. tazawai start from two-thirds of the length, and the top of the fold on the dorsal valve is relatively flat. However, the fold and sulcus of P. selongensis n. sp. start from the middle of the shell. Moreover, P. tazawai has more plicae than P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13): P. tazawai has 1–6 plicae on the ventral sulcus, 2–7 on the dorsal fold, 1–3 obvious plicae on the lateral shell margin, and 1–2 bends found only on the lateral commissure. P. tazawai has a rounded submesothyrid foramen. However, P. selongensis n. sp. has an oval or rounded-triangle-shaped hypothyroid foramen. In terms of the internal structures, the hinge teeth of P. tazawai are weaker than those of P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13). Popov in Popov and Zakharov (Reference Popov and Zakharov2017) described P. tazawai as having a calcariform crura. However, based on the serial sections of P. tazawai (Popov in Popov and Zakharov, Reference Popov and Zakharov2017, figs. 3, 4), the crura appears more raduliform, with the distal ends converging toward each other (Fig. 13).

Piarorhynchella kittli Gaetani in Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019, is larger than P. selongensis n. sp., with a maximum length of 13.6 mm and maximum width of 16.3 mm (Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019), while those of P. selongensis n. sp. are 10.06 mm and 11.21 mm, respectively. The linguiform extension of P. kittli, which is triangular or trapezoidal, bevels at a high angle to the anterior commissure. The height of the linguiform extension is less than or equal to the thickness because the dorsal fold is slightly recumbent in the anterior region (Fig. 13). However, P. selongensis n. sp. shows obvious differences with these aspects (Fig. 13). P. kittli seems to be characterized by asymmetrical development (Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019, pl. 3, figs. B1-5, C1-5, D1-5, E1-5) and different sizes of plicae in the fold and sulcus (Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019, pl. 3, figs. C1-5, D1-5). However, very few specimens are asymmetric, and the plicae are always the same size on the fold and sulcus of P. selongensis n. sp. Due to the strong recrystallization in the shell, some of the internal structures of P. kittli are only roughly recognized with no detailed description (Grădinaru and Gaetani, Reference Grădinaru and Gaetani2019). Therefore, it is difficult to compare them to P. selongensis n. sp.

?Piarorhynchella griesbachi (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a) seems to have more variation in outline, from subpentagonal (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2, 6) to elongated subpentagonal (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a, pl. 2, figs. 3–5), than P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13). In addition, there are 1–3 plicae on the ventral sulcus and 2–4 plicae on the dorsal valve, while P. selongensis n. sp. has at most two plicae on the ventral sulcus and three on the dorsal valve. Moreover, ?P. griesbachi has more distinct plicae on the fold and sulcus than P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13). Because the serial sections of ?P. griesbachi originally published by Bittner (Reference Bittner1899a) have not been studied, the internal structures of this species cannot be compared with P. selongensis n. sp. In addition, another species, ?Piarorhynchella dieneri (Bittner, Reference Bittner1899a), which was also collected in India, has some features in common with P. selongensis n. sp. However, ?P. griesbachi and ?P. dieneri should be represented as different ontogenetic stages of the same species (Gaetani et al., Reference Gaetani, Balini, Nicora, Giorgioni and Pavia2018).

Nudirostralina subtrinodosi Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966 (maximum length and width: 10.98 mm and 14.26 mm, respectively; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Chen and Harper2019) is larger than P. selongensis n. sp. (maximum length and width: 10.06 mm and 11.21 mm, respectively). N. subtrinodosi is strongly dorsibiconvex in profile, while P. selongensis n. sp. is biconvex. N. subtrinodosi has a rather high and distinct linguiform extension, which is beveled toward the anterior commissure at a high angle, and the height is equal to or slightly less than the maximum thickness (Fig. 13). Therefore, the dorsal valve has a high and obvious fold corresponding to the linguiform extension. However, there are features that exhibit apparent differences from P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13). N. subtrinodosi has more distinct and strong plicae (both on the sulcus and fold and lateral flanks) than P. selongensis n. sp. (Fig. 13). The plicae of N. subtrinodosi originate at the posterior or at two-thirds of the length. However, the plicae of P. selongensis n. sp. start from one-third to one-quarter of the length. In terms of the internal structures, the hinge teeth of P. selongensis n. sp. are stronger than those of N. subtrinodosi (Fig. 13). The crura of N. subtrinodosi are either canaliform or calcariform (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Chen and Harper2019, fig. 8), while the crura of P. selongensis n. sp. might be treated as raduliform (Fig. 13). It should be noted that Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Chen and Harper2019) considered Piarorhynchella Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, and Nudirostralina Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966, to be essentially the same. However, by studying a large number of specimens of P. selongensis n. sp. (Figs. 4–12) and comprehensively reviewing the relevant literature for each species of Piarorhynchella, as well as taking into account ontogenetic characteristics and intraspecific variation, we found that all species of Piarorhynchella have the following stable characteristics (Fig. 13): (1) the length of plicae on the fold and sulcus is usually less than half of the length; (2) the plicae on the lateral flanks are weaker and shorter than the plicae on the fold and sulcus; (3) the dorsal valve has a long, massive median septum; and (4) the crura is raduliform. However, as mentioned above, the distribution of the plicae, the development of lateral plicae, fold and sulcus, and the type of crura of N. subtrinodosi show obvious differences with these common features of Piarorhynchella (Fig. 13). Based on this evidence, we consider Nudirostralina (with N. subtrinodosi as a type species) and Piarorhynchella to be two different genera, but they are closely related in their evolution.

Order Athyrida Boucot, Johnson, and Staton, Reference Boucot, Johnson and Staton1964

Suborder Retziidina Boucot, Johnson, and Staton, Reference Boucot, Johnson and Staton1964

Superfamily Retzioidea Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Family Neoretziidae Dagys, Reference Dagys1972

Subfamily Hustediinae Grunt, Reference Grunt1986

Genus Schwagerispira Dagys, Reference Dagys1972

Type species

Retzia schwageri Bittner, Reference Bittner1890; Köveskál and Sintwag, North Alpine; Anisian.

Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen new species

Figures 14–17

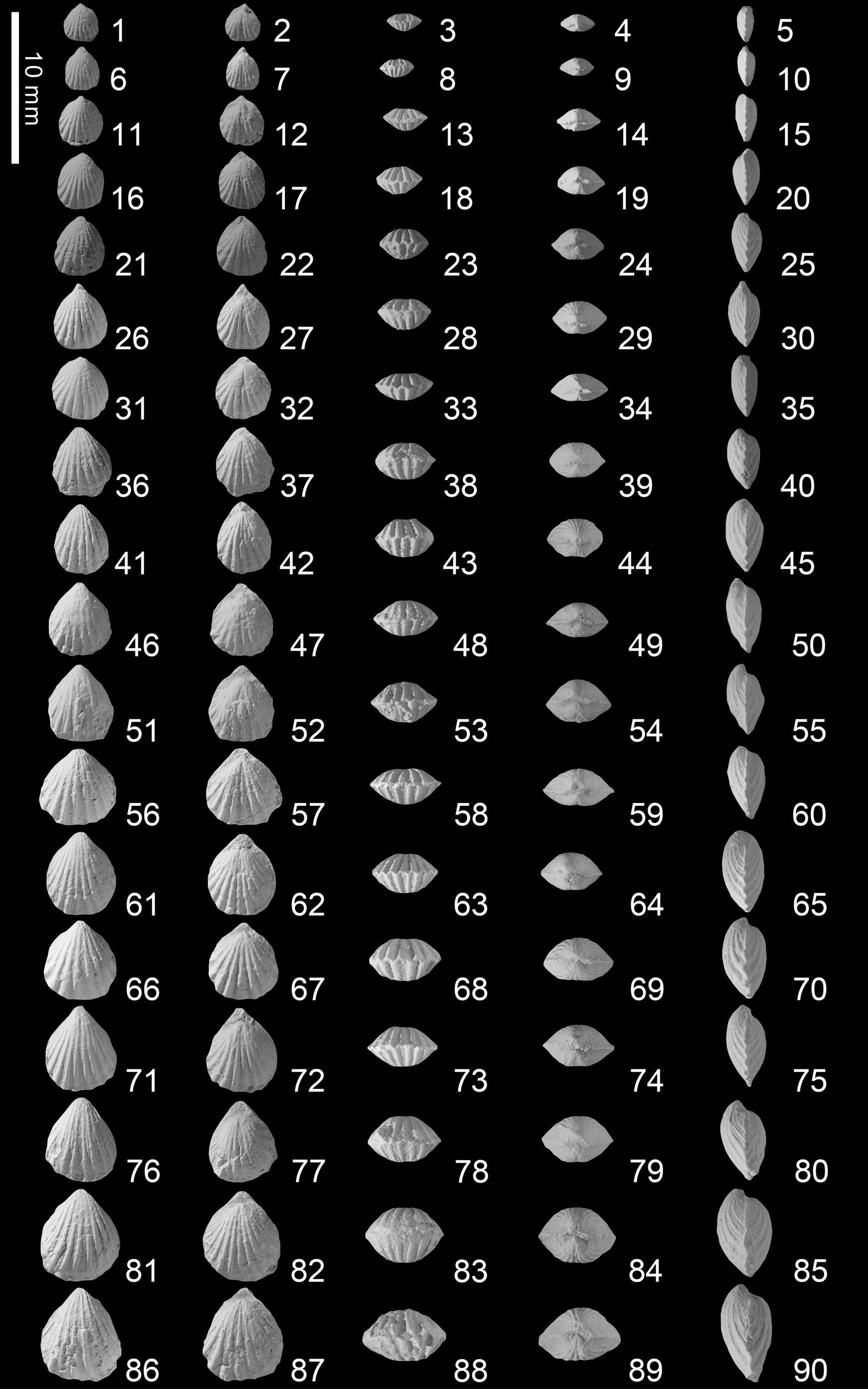

Figure 14. Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, and lateral views. (1–5) SL-B-001; (6–10) SL-B-002; (11–15) SL-B-003; (16–20) SL-B-004; (21–25) SL-B-005; (26–30) SL-B-006; (31–35) SL-B-007; (36–40) SL-B-008; (41–45) SL-B-009; (46–50) SL-B-010; (51–55) SL-B-011; (56–60) SL-B-012; (61–65) SL-B-013; (66–70) SL-B-014; (71–75) SL-B-015; (76–80) SL-B-016; (81–85) SL-B-017; (86–90) SL-B-018.

Figure 15. Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, and lateral views. (1–5) SL-B-019; (6–10) SL-B-020; (11–15) SL-B-021; (16–20) SL-B-022; (21–25) SL-B-023; (26–30) SL-B-024; (31–35) SL-B-025; (36–40) SL-B-026; (41–45) paratype SL-B-027; (46–50) paratype SL-B-028; (51–55) holotype SL-B-029.

Figure 16. (1) Scatter plot of length/width of 181 articulated shells of Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. (2) Scatter plot of length/thickness of the same. The red dotted line represents the trend line.

Figure 17. Serial sections of Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. based on specimen SL-B-SS-002. The distance from the ventral beak to individual section is given in mm. Ventral valve upward.

Holotype

Specimen SL-B-029 (Fig. 15.51–15.55), from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Paratypes

Specimens SL-B-028 (Fig. 15.46–15.50) and SL-B-027 (Fig. 15.41–15.45), from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Diagnosis

Small size, generally elliptical in outline, equibiconvex in profile, anterior commissure rectimarginate, dorsal median sulcus very weak, shallow, and only developed at the anterior region. Shells bear 9–14 costae, median costa on the dorsal sulcus slightly weaker and wider than the adjacent two costae. Width of interspace equal to width of costae. Bottom of the interspace flat. Pedicle collar developed, dental plates absent, cardinal flanges very thick and project toward the ventral valve, hinge plates thick, and the middle portion arched toward the ventral valve.

Occurrence

Kangshare Formation of early Smithian, Selong section, southern Tibet, China.

Description

Shell generally elliptical (a small number of specimens subcircular) in outline. Small size (2.01–9.61 mm long, 1.81–8.26 mm wide); length obviously larger than width; maximum width located at two-thirds of length anteriorly. Equibiconvex in profile, 0.85–5.73 mm thick; maximum thickness reached in the middle of the shell. Lateral margin nearly straight to slightly curved; anterior margin straight. Hinge line short and curved, much shorter than the maximum width. Dorsal sulcus very weak, only appearing at anterior region. Anterior commissure rectimarginate. Shell surface entirely covered by round costae, without distinct concentric growth lines.

Ventral valve mildly convex, maximum convexity approximately in the middle of the valve. Umbo mildly curved, middle part flat, anterior slightly to mildly bent. Apical angles 74–106°. Beak distinct, slightly incurved. Beak ridges round. Small foramen permesothyrid, oval to circular in shape. Interarea apsacline, high and distinct. Deltidial plates divided.

Dorsal valve mildly convex, maximum convexity approximately at mid-length. Umbo strongly curved, middle part flat, anterior slightly to mildly bent. Extremely shallow and narrow sulcus begins at middle to anterior of ventral valve, indistinct. One costa on the sulcus.

Shell surface bears straight and simple costae, with no bifurcation and extending anteriorly from the beak. Costae rounded, with the tops flat, and the sides strongly inclined. Interspace between two adjacent costae shallow, with flat bottom. Width of the interspace is equal to width of the costa. Three types of costae arrangement appear: 10 costae on the ventral valve and nine costae on the dorsal valve (10/9, 12%), 12 costae on the ventral valve and 11 costae on the dorsal valve (12/11, 68%), and 14 costae on the ventral valve and 13 costae on the dorsal valve (14/13, 20%). Middle costa on the shallow and narrow dorsal sulcus depressed, and with quite flat top. Development of the middle costa weaker than that of adjacent costae. Width of the middle costa larger than that of other costae, especially at the anterior region. Strength and width of the costae on both sides of the middle costa decrease slowly to the posterior region. Middle interspace on the ventral valve much wider than that of other interspaces. Strength and width of the costae on both sides of the middle interspaces also decrease slowly towards the postero-lateral region.

Pedicle collar in the ventral valve well developed, connects to the deltidial plates. Dental plates absent. Blunt hinge teeth elongate transversely and parallel to the hinge axis. Cardinal flanges in the dorsal valve highly developed, extend from inner socket ridges perpendicular to the hinge axis and project strongly to the ventral valve. Lumpy cardinal flanges extend from the cardinal plate and approach the ventral valve. Hinge plates thick, and middle portion arched to the ventral shell, forming cusps. Median septum thin and relatively high. Spiralia and jugum unknown.

Etymology

In honor of the Chinese paleontologist Yongming Chen, who studied the Early and Middle Triassic brachiopods in Tulong in southern Tibet, China.

Material

A total of 181 complete specimens collected from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation. Of these, four specimens were sectioned (SL-B-SS-001, SL-B-SS-002 [Fig. 17], SL-B-SS-003, SL-B-SS-004) and 29 selected specimens were photographed.

Remarks

Schwagerispira schwageri (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890), the type species of the genus Schwagerispira Dagys, Reference Dagys1972, has a different number of costae than S. cheni n. sp. S. schwageri has two types costae distributions: 6/7 (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 36, figs. 1, 2, 4; Dagys, Reference Dagys1974, pl. 42, fig. 8; Pálfy, Reference Pálfy2003, pl. Br-I, fig. 3) and 10/11 (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 36, fig. 3). The beak of S. schwageri is much stronger and higher than that of S. cheni n. sp. (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 36, figs. 1, 3). The costae of S. schwageri are subangular and appear subtriangular in cross-sections, while those of S. cheni n. sp. are rounded and appear semi-circular in cross-sections. In addition, the interspaces between two adjacent costae of S. schwageri are always narrower than the width of the costae. The bottom of the interspace is V-shaped (Fig. 18). Nevertheless, these features are completely different than S. cheni n. sp. (Fig. 18). Bittner (Reference Bittner1890) noted that S. schwageri has a slightly recessed middle costa on the dorsal valve (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 36, figs. 1, 3), and the width of the middle costa is larger than or equal to that of other costae. However, these features are absent from other specimens collected by Dagys (Reference Dagys1972, Reference Dagys1974) and Pálfy (Reference Pálfy2003). Therefore, it may be different than S. cheni n. sp. S. schwageri has two lobed cardinal flanges extending from the cardinal plate (Fig. 18). However, S. cheni n. sp. has massive cardinal flanges stretching from the cardinal plate (Figs. 17, 18).

Figure 18. Comparison of the main external and internal features in all the species of Schwagerispira. The figures of crura show the distal ends in serial sections.

Schwagerispira fuchsi (Koken, Reference Koken1900) was first collected in southwestern China. This species also has been reported by Sun and Ye (Reference Sun and Ye1982) in northwestern China, However, S. fuchsi lacks a distinct dorsal sulcus and a recessed, narrow middle costa (Sun and Ye, Reference Sun and Ye1982, pl. 3, figs. 5–8). Therefore, these specimens might not represent typical S. fuchsi. S. fuchsi has subangular costae that are subtriangular in cross-sections, while S. cheni n. sp. has rounded costae that are semi-circular in cross-sections. The dorsal sulcus of S. fuchsi is more distinct than S. cheni n. sp. The median costa, which is located in the dorsal sulcus, has opposite development between two species. The median costa of S. fuchsi is weaker, lower, and narrower than the adjacent costae. The two widest and most-developed costae are situated alongside the dorsal sulcus (Fig. 18). However, the middle costa of S. cheni n. sp. is wider than that are other costae. S. fuchsi has V-shaped interspaces between two adjacent costae. However, the bottom of the interspace between two adjacent costa of S. cheni n. sp. is very flat. Moreover, the hinge plates of S. cheni n. sp. is much thicker than that of S. fuchsi (Fig. 18).

The outline of Schwagerispira subcircularis (Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966) is subcircular, whereas S. cheni n. sp. shows a generally elliptical outline (Fig. 18). There is no sulcus on the dorsal valve of S. subcircularis (Yang and Xu, Reference Yang and Xu1966). However, S. cheni n. sp. has a dorsal sulcus. The costae of S. subcircularis are subangular, and the widths of the V-shaped interspaces are less than the widths of the costae. Nevertheless, S. cheni n. sp. has rounded costae, the widths of which are equal to those of the interspaces. The bottoms of the interspaces are flat. Because serial sections of S. subcircularis have never been studied, their internal structures cannot be compared with S. cheni n. sp.

Schwagerispira pinguis Sun and Ye, Reference Sun and Ye1982, has a rounded triangular outline (Fig. 18), whereas the outline of S. cheni n. sp. is a generally elliptical shape. The shell convexity of S. pinguis is slightly greater than that of S. cheni n. sp. S. pinguis has no sulcus on the dorsal valve. The size and development of the middle costa on the dorsal valve are the same as those of the adjacent costae. However, S. cheni n. sp. has a dorsal sulcus. The dorsal middle costa is wider than the adjacent costae. Interiorly, S. pinguis has thin hinge plates and a strong dorsal median septum (Fig. 18), while S. cheni n. sp. has very thick hinge plates and a thin dorsal median septum (Figs. 17, 18).

Schwagerispira sichuanensis Liao and Sun, Reference Liao and Sun1974, has a much higher and longer ventral beak than that of S. cheni n. sp. The features of costae and interspace are completely different between the two species. The costae of S. sichuanensis are subangular and subtriangular in cross section. The width of the V-shaped interspace between two adjacent costae is narrower than the width of the costa. S. sichuanensis has no sulcus on the dorsal valve. Therefore, the middle costa on the dorsal valve shows no difference from adjacent costae. These features also show distinct differences with S. cheni n. sp. In the internal structures, S. sichuanensis has thick and two-lobed cardinal flanges extending from the cardinal plate (Fig. 18), while S. cheni n. sp. has rounded cardinal flanges stretching from the cardinal plate (Figs. 17, 18).

Both Schwagerispira fastosa (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890) and S. cheni n. sp. are generally elliptical, but the former shows significant varieties in outline from elongated subpentagonal to generally elliptical. The beak of S. fastosa is more distinct and higher than that of S. cheni n. sp. S. fastosa has a very indistinct sulcus on the dorsal valve, while S. cheni n. sp. has a narrow and shallow sulcus. According to the original description by Bittner (Reference Bittner1890), the middle costa on the dorsal valve of S. fastosa is usually weaker and lower than or has the same development as the adjacent costae. However, these features were not observed in specimens collected from the other areas (Bittner, Reference Bittner1890, pl. 36, figs. 17–20; Jin and Fang, Reference Jin and Fang1977, pl. 5, figs. 13–16; Iordan, Reference Iordan1993, pl. 2, fig. 7; Siblík, Reference Siblík1994, pl. 1, fig. 9; Siblík and Bryda, Reference Siblík and Bryda2005, pl. 2, fig. 2). It seems that this feature is not stable in S. fastosa. Through the observation of specimens from different regions, we found that S. fastosa has subangular costae; the widths of interspaces are smaller than the widths of the costae and are V-shaped. These features stand in stark contrast to S. cheni n. sp. The internal structures of S. fastosa have not been studied.

?Schwagerispira tulongensis (Chen, Reference Chen1983) has fewer costae than that does S. cheni n. sp. The bottom of the interspaces of ?S. tulongensis are slightly convex, while the bottom of the interspaces of S. cheni n. sp. are flat. Based on the indistinct serial sections of ?S. tulongensis, the cardinal flanges and hinge plates seem very thin (Chen, Reference Chen1983, fig. 4; Fig. 18). However, S. cheni n. sp. possesses very developed and thick cardinal flanges and hinge plates (Figs. 17, 18).

Order Terebratulida Waagen, Reference Waagen1883

Suborder Terebratellidina Muir-Wood, Reference Muir-Wood1955

Superfamily Zeillerioidea Allan, Reference Allan1940

Family Zeillerlldae Allan, Reference Allan1940

Subfamily Zeilleriinae Allan, Reference Allan1940

Genus Selongthyris Wang and Chen new genus

Type species

Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp., Kangshare Formation, Early Triassic, Selong section, southern Tibet, China.

Diagnosis

Small size, shell flat, subcircular, elongate suboval to subpentagonal in outline, ventribiconvex in profile, without fold and sulcus, anterior commissure rectimarginate, shell smooth without plicae. Ventral myophragm low and long. Dental plates absent. Hinge plates undivided. Septalium shallow and wide. Crural bases arise from the inner socket ridges and hinge plates stretch to the ventral valve. Loop long and delicate, teloform, descending lamellae slightly curved anteriorly, strongly convergent and closer each other, spine structures absent.

Occurrence

Kangshare Formation of the early-late Smithian, Selong section, southern Tibet, China.

Etymology

Named after the Selong section, and the Latin thyris, window or hole.

Remarks

According to the diagnostic criteria, Selongthyris n. gen. is easily distinguished from most of the subfamily Zeilleriinae Allan, Reference Allan1940. Periallus Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, is the most similar taxon to Selongthyris n. gen. in terms of the external features. However, the anterior commissure of Periallus ranges from rectimarginate, to uniplicate or paraplicate, whereas Selongthyris n. gen. only has a rectimarginate anterior commissure. There were obvious differences in the internal structures between the two genera mainly based on the absence of a low ventral myophragm in Periallus. In addition, Periallus has divided hinge plates, and its inner hinge plates are unstable and are sometimes absent entirely. The median septum and septalium are present or replaced by crural plates directly connected to the dorsal valve. Crural bases arise from the middle of the hinge plates and stretch to the dorsal valve. In addition, the descending lamellae converge anteriorly, but are separated widely. The whole dorsal surface of the descending lamellae is covered with many spines.

The Early Triassic Obnixia Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, and Protogusarella Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979, have a shallow sulcus and fold in the anterior region, and the anterior commissure is unisulcate. However, Selongthyris n. gen. does not develop a sulcus or fold on the shell; thus, it has a rectimarginate anterior commissure. The internal structures of Selongthyris n. gen. are quite different from those of the other two genera. There is no median septum or septalium in either Obnixia or Protogusarella. The crural bases stretch to the dorsal valve, and the descending lamellae converge anteriorly, but are wide separated. In addition, the loop of Obnixia has spines on the junction of the descending lamellae and ascending lamellae.

Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen new species

Figures 19–23

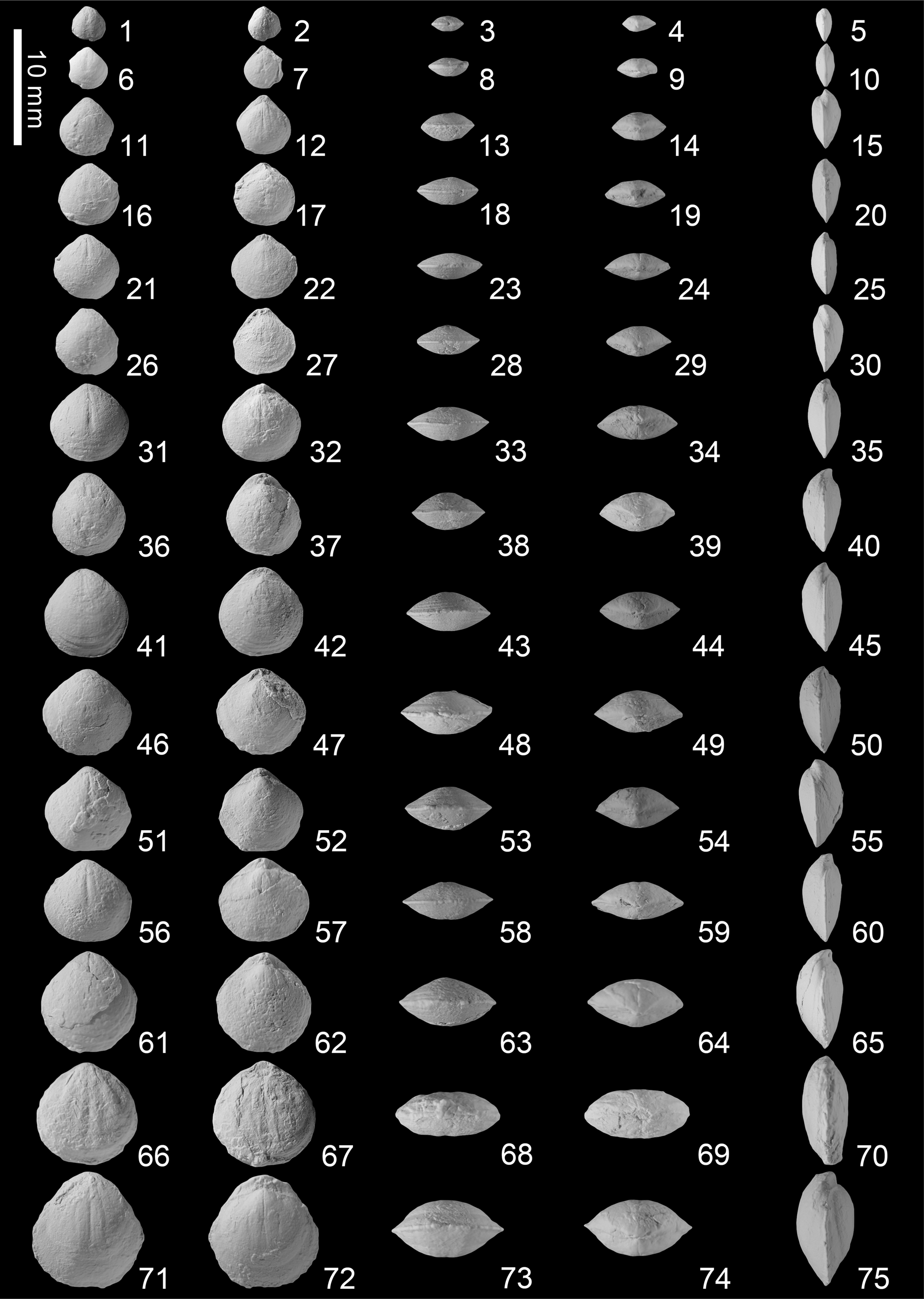

Figure 19. Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. from the Kangshare Formation of Selong section, southern Tibet. For each shell we present ventral, dorsal, anterior, posterior, and lateral views. (1–5) SL-C-001; (6–10) SL-C-002; (11–15) SL-C-003; (16–20) SL-C-004; (21–25) SL-C-005; (26–30) SL-C-006; (31–35) SL-C-007; (36–40) SL-C-008; (41–45) SL-C-009; (46–50) SL-C-010; (51–55) SL-C-011; (56–60) SL-C-012; (61–65) paratype SL-C-013; (66–70) paratype SL-C-014; (71–75) holotype SL-C-015.

Figure 20. (1) Scatter plot of length/width of 181 articulated shells of Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. (2) Scatter plot of length/thickness of the same. The red dotted line represents the trend line.

Figure 21. Serial sections of Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. based on specimen SL-C-SS-001. The distance from the ventral beak to individual section is given in mm. Ventral valve upward. Sections continue in Figure 22.

Figure 22. Serial sections of Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. based on specimen SL-C-SS-001. Sections continued from Figure 21.

Figure 23. Reconstructed dorsal internal view of Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. based on the serial sections in Figures 21 and 22. Abbreviations: A. l. = ascending lamellae; C. P. = crural process; D. l. = descending lamellae; H. p. = hinge plate; I. h. r. = inner hinge ridge; M. s. = median septum; So. = socket; Sp. = septalium; T. b. = transverse band.

Holotype

Specimen SL-C-015 (Fig. 19.71–19.75) from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Paratypes

Specimens SL-C-013 (Fig. 19.61–19.65) and SL-C-014 (Fig. 19.66–19.70) from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section in southern Tibet, China.

Diagnosis

Shell small and flat, subcircular, elongate suboval to subpentagonal in outline, ventribiconvex in profile, anterior commissure rectimarginate, shell surface without fold and sulcus, shell entirely smooth. Ventral myophragm low and long, dental plate thin but distinct, hinge teeth long. Dorsal valve with deep sockets, inner socket ridges thick, hinge plates undivided, crural bases arise from the junction of inner socket ridges and hinge plates, and stretch to the ventral valve, median septum high, septalium shallow and wide. Loop teloform, long and delicate, descending lamella slightly curved anteriorly, strongly convergent, and closely approached, ascending lamellae extended relatively broadly. No spine structures on loop.

Occurrence

Kangshare Formation of the early-late Smithian, Selong section, southern Tibet, China.

Description

Subcircular, elongate suboval to subpentagonal in outline. Shell small, 2.67–8.97 mm long, 2.57–8.47 mm wide; length slightly larger than width, or equidimensional; maximum width at middle of the shell. Ventribiconvex (occasionally subequally biconvex) in profile; very flattened shell, 1.02–4.55 mm thick, maximum thickness located in middle to posterior part of the shell. Postero-lateral margin straight; lateral margin rounded, strongly curved; anterior margin straight to slightly curved. Hinge line short and curved, much shorter than the maximum shell width. Anterior commissure rectimarginate, without ventral or dorsal fold and sulcus. Shell smooth, covered with concentric growth lines and lamellae in the anterior region.

Ventral valve gently convex, maximum convexity located approximately close to the umbonal region. Umbo mildly convex, middle part flat, anterior part extends forward and is slightly bent. Beak wide and short, slightly incurved, tangential to and slightly protrudes out of the commissure plane, apical angles 98–136°. Beak ridges round and straight. Interarea short but distinct, triangular in shape. Foramen mesothyrid small, oval or circular in shape; deltidial plates divided.

Dorsal valve slightly convex, maximum convexity located at the umbonal region. Umbo strongly curved, middle and anterior part slightly bent forward with the same degree.

Ventral dental plates thin and straight, nearly parallel posteriorly and slightly converge anteriorly. Hinge teeth relatively strong and long, oblique to the plane of symmetry at ~45°. Myophragm low and long up to half of length of shell in size. Pedicle collar unknown. Dorsal valve with deep sockets expands anterolaterally. Inner hinge ridges very developed and thick, posterodistally hooked, oblique to the plane of symmetry at ~45°. Hinge plates thin, undivided, tilt toward the plane of symmetry at ~45°. Median septum thick and low, extending approximately one-third of the length of the dorsal valve, and connects to hinge plates forming very shallow and wide septalium. Cardinal process undeveloped. Crural bases large, very distinct, oval to circular in shape, arising from the junction of inner socket ridges and hinge plates, and stretch to the ventral valve. Loop teloform, long and delicate, commonly about two-thirds of the length of the dorsal valve; descending lamellae slightly curved anteriorly, strongly convergent, and closely approached, while the ascending lamellae are relatively broadly extended. Crural process short, width slightly larger than maximum diameter of the crural bases; descending lamellae very flat but relatively wide; ascending lamellae slender and narrow; transverse band narrow and short and appear at approximately one-third of the length of the dorsal valve. No spine structures on the loop. In serial sections, crural process triangular or parenthesis-shaped, and inclines toward the plane of symmetry; descending lamellae thin arc, and horizontal or very slightly inclined toward the plane of symmetry; ascending lamellae triangular in the posterior area, becomes thin line anteriorly, and inclines toward the plane of symmetry.

Etymology

From the Latin, planus (plana, feminine), denoting the flat shells.

Material

A total of 32 complete specimens collected from the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation. Of these, three specimens were sectioned (SL-C-SS-001 [Figs. 21, 22], SL-C-SS-002, SL-C-SS-003) and 15 selected specimens were photographed.

Remarks

Because the overall shape of the loop changes as the shell grows (MacKinnon and Lee, Reference MacKinnon, Lee and Kaesler2006), only by comparing the same growth stage of loops in different species we can accurately identify the differences among several species. Hoover (Reference Hoover1979) studied the development of loops in small-sized specimens of Obnixia thaynesiana (Girty, Reference Girty1927) (12.3 mm maximal length, 11.7 mm maximal width). The results indicated that the loop matures (Glossothyropsiform stage; Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, pl. 3, figs. 8–13) when the shell grows to half of its maximum length (3.35–6.6 mm in dorsal length; Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, Table 1). To study the internal structures of S. plana n. gen. n. sp., we selected a specimen with a length of 7.25 mm to grind the serial sections because the largest holotype specimen (Fig. 19.71–19.75, SL-C-015, 8.97 mm in length) and the smaller paratype specimens (Fig. 19.66–19.70, SL-C-014, 8.27 mm in length; Fig. 19.61–19.65, SL-C-013, 7.54 mm in length) have only one complete specimen. Therefore, based on ontogeny, this smaller specimen can still typify the adult structure of S. plana n. gen. n. sp.

Periallus woodsidensis Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, a narrowly distributed species from western USA (Hoover, Reference Hoover1979; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Hautmann, Wasmer and Bucher2013), is subtrigonal or oval to subpentagonal in outline, whereas S. plana n. gen. n. sp. is subcircular. The anterior commissure of P. woodsidensis varies greatly, from rectimarginate to uniplicate or paraplicate, while S. plana n. gen. n. sp. shows only a rectimarginate anterior commissure in both adults and juveniles. The mesothyrid foramen of P. woodsidensis is larger than that in S. plana n. gen. n. sp.. In terms of the internal structures, P. woodsidensis has no myophragm in the ventral valve, while S. plana n. gen. n. sp. shows a low myophragm in the ventral valve (Figs. 21, 22). The development of inner hinge plates of P. woodsidensis is unstable and sometimes completely absent (Fig. 24). Nevertheless, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. shows undivided hinge plates (Figs. 21, 24). The septalial plates of P. woodsidensis are also variably expressed as short vertical crural plates that connect inner hinge plates to the valve floor or as a low and wide septalium that links the inner hinge plates to the dorsal median septum (Fig. 24). However, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. always has a stable septalium (Figs. 21, 24). The crural bases of P. woodsidensis arise from the middle of the hinge plates and stretch to the dorsal valve (Fig. 24). Nevertheless, it is quite distinct from S. plana n. gen. n. sp. (Figs. 21, 24). There is a substantial difference between P. woodsidensis and S. plana n. gen. n. sp. in the structure of the loop. P. woodsidensis has descending lamellae and broad ascending lamellae that converge anteriorly, but are widely separated. The entire dorsal surface of the descending lamellae is profusely covered with spines (Fig. 24).

Figure 24. Comparison of the main external and internal features in Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. with Periallus woodsidensis Hoover, Reference Hoover1979, Obnixia thaynesiana (Girty, Reference Girty1927), Protogusarella smithi Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979, and Tosuhuthyris sulcus Sun and Ye, Reference Sun and Ye1982. The figures of loop are shown by serial sections through posterior to anterior or silicified specimens.

Obnixia thaynesiana has a shallow sulcus anteriorly in the early stages of ontogeny, and forming a unisulcate commissure. However, in all specimens, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has no sulcus, and the anterior commissure still belongs to the rectimarginate type. O. thaynesiana has thin and very short deltidial plates, while S. plana n. gen. n. sp. shows relatively high and distinct deltidial plates. For the internal structures, O. thaynesiana has no myophragm in the ventral valve (Fig. 24), while S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has a low myophragm (Figs. 21, 22). O. thaynesiana has only a low myophragm and no inner hinge plates, dorsal median septum, or septalium in the dorsal valve (Fig. 24). The descending lamellae and ascending lamellae of O. thaynesiana are widely separated and convergent anteriorly. Spines commonly appear at the junction of the descending and ascending lamellae (Fig. 24). All these structures have massive differences compared with S. plana n. gen. n. sp. (Figs. 21–24).

Protogusarella smithi Perry and Chatterton, Reference Perry and Chatterton1979, has a weak sulcus on the dorsal valve and a weak fold on the ventral valve anteriorly, forming a weakly unisulcate to rectimarginate anterior commissure. However, all specimens of S. plana n. gen. n. sp. are rectimarginate in the anterior commissure and have no sulcus or fold on the shell surface. The valves of P. smithi are equally biconvex in profile, whereas the shells of S. plana n. gen. n. sp. are ventribiconvex in profile. The foramen of P. smithi belongs to the permesothyrid type, and the deltidial plates are very short and thin. Nevertheless, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has a mesothyrid foramen with high, distinct deltidial plates. As for the internal structures, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has a low myophragm on the ventral valve, while P. smithi lacks myophragm on the ventral valve (Figs. 21, 22, 24). The cardinal plates of the two species have apparent differences (Fig. 24). The inner hinge plates (crural plates) of P. smithi are directly connected to the dorsal valve with no median septum or septalium. Besides, the crural bases possibly stretch to the dorsal valve. In addition, in specimens of P. smithi, the long and ventrally pointed crural process inclines toward the lateral region, and the descending lamellae and ascending lamellae are widely separated and slightly convergent anteriorly (Fig. 24).

Tosuhuthyris sulcus Sun and Ye, Reference Sun and Ye1982 (holotype specimen: 13.6 mm in length and 13 mm in width; paratype specimen: 13.9 mm in length and 17 mm in width) is larger than S. plana n. gen. n. sp. (2.67–8.97 mm in length and 2.57–8.47 mm in width). The dorsal valve of T. sulcus has a shallow sulcus that forms a unisulcate anterior commissure. However, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. consistently shows a rectimarginate anterior commissure, without any sulcus or fold. In the interior of the ventral valve, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has a low myophragm, but T. sulcus does not. The biggest difference between the two species is the loop. The loop of T. sulcus is very simple and short, with only descending lamellae and no transverse band, such as a simple crura (Fig. 24). In contrast, S. plana n. gen. n. sp. has a long teloform loop (Figs. 21–24).

Reconstruction of ontogeny

In this study, we compared the individual morphological changes of these species in each growth period and found that the three species showed completely different development patterns. Shell shape of Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. changed greatly throughout the growth processes, with very clear differences between juveniles and adults (Figs. 4–9). The juvenile shell has a subtriangular outline with length larger than width (Fig. 8.1) and maximum width located in the middle of the shell. As the shell grows, width grows at a greater rate than length (Fig. 8.1). Its flanks gradually widen, the anterior part of the outline becomes straighter, and the outline gradually becomes subpentagonal. The shell reaches maximum width at three-quarters length towards the anterior. With the growth of the shell, the convexity of the shell also changes (Figs. 4–6, 8.2). Juveniles have flat ventral valves and convex dorsal valves with maximum thickness located at the posterior area. However, adult shells are much more convex with the dorsal valve slightly more convex than that ventral valve, and the maximum thickness in the middle of the shell. Juveniles have smooth shells, very shallow sulcus in the dorsal valve, and less-significant fold in the ventral valve (Fig. 4). As the shell grew, the distribution of the sulcus and fold was reversed: the anterior part of the ventral valve extended forward and bent strongly to form a linguiform extension and the central bulge of the dorsal valve formed a fold (Figs. 4–7). The sulcus and fold gradually developed plicae and form two different development directions (Fig. 7): one in which two plicae appear on the fold and one in which three plicae appear on the fold. Statistics show that there are equal numbers of each type, which shows that these two kinds of shell forms have no special advantages. There are no plicae on the lateral flanks before the shell fold and sulcus become obvious. Where the fold and sulcus emerge, they are flanked by weak plica that appeared on the side of lateral flanks of the two valves, occasionally forming a second shorter and weaker plica on the lateral margin (Figs. 4–6). The anterior commissure becomes increasingly uniplicate through growth, eventually becoming bisulcate in larger shells (Figs. 4–7).

Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. only showed subtle changes in morphology through development (Figs. 14–16). S. cheni n. sp. has the same outline (Figs. 14–16.1), profile (Fig. 16.2), and number of costae (Figs. 14, 15) throughout growth, but the beak becomes slightly curved during shell growth. With the growth of the shell, the narrow median dorsal sulcus, which arises from the umbo area, widened progressively, but remained shallow and becomes indistinct (Figs. 14, 15). As the shell grew, the narrow median costa gradually widened, and finally became wider than other costae in the anterior region (Figs. 14, 15). As the width of the middle costa increased, the top of the middle costa gradually flattened (Figs. 14, 15).

Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp. showed small morphological change through shell growth. The outline (Figs. 19, 20.1) and profile (Fig. 19) of S. plana n. gen. n. sp. are roughly the same through development. As the growth rate of the shell decreased, the convexity of the shell gradually increased (Fig. 20.2). However, even in adult specimens, the shells are still very flat (Figs. 19, 20.2). There is no sulcus or fold during growth of the shell, so the anterior commissure of this species is rectimarginate in all specimens (Fig. 19). The beak of the juveniles is slightly incurved and never tangent to the commissure plane. However, as the shell grew, the beak of the adults became more curved and tangent to the commissure plane.

Brachiopod recovery after the Permian–Triassic extinction

There are nine orders of Permian-type brachiopods (Permian relict brachiopods) in the latest Permian–earliest Triassic strata, including Lingulida, Orthothetida, Orthida, Productida, Spiriferida, Spiriferinida, Rhynchonellida, Athyrida, and Terebratulida (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho and George2005a). All Permian relict brachiopods were extinct before the early Griesbachian, with the exception of some inarticulate brachiopods. Only the Spiriferinida, Rhynchonellida, Athyrida, and Terebratulida survived the extinction (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho and George2005b), sharing several characteristics that clearly differed from the Permian-type brachiopods. In this study, the brachiopods found in the strata of the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation in the Selong section were all typical Mesozoic species. Piarorhynchella selongensis Wang and Chen n. sp. belongs to order Rhynchonellida and has very simplified internal and external features. These features consist of a small size, weak and few plicae, a smooth shell surface from the middle to the beak, a ventral valve with thin dental plates with no spondylium or median septum, no complex cardinal process in the dorsal valve, hinge plates, a median septum, a septalium, and raduliform crura in the simplest forms. In comparison to the Permian species of the athyridide Hustedia, Schwagerispira cheni Wang and Chen n. sp. also belongs to order Athyrida, but it is smaller in size, has less-pronounced and rounded costae, and has simpler cardinal structures. Selongthyris plana Wang and Chen n. gen. n. sp., a terebratulide, is characterized by a small size, flat shell, no sulcus or fold, no shell ornaments, and the presence of a simple teloform loop.

The recovery process of brachiopods after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction in southern Tethys remains unclear. The Selong section was a candidate of the Global Stratotype Section and Point of the Permian-Triassic boundary, which spans the late Permian Selong group and the Early Triassic Kangshare Formation. Brachiopod fossils have been studied in detail by Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2000, Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2001) in the strata of the late Permian Selong Group. Forty-two brachiopod species in 30 genera and two unidentifiable genera that represent a typical big, thick-shelled, Peri-Gondwanan type brachiopod fauna have been recorded. In addition, Shen and Jin (Reference Shen and Jin1999) studied brachiopods of the Permian-Triassic boundary beds (Waagenites Bed) at Selong. However, the Waagenites Bed at the bottom of the Kangshare Formation contained a different group of small- to medium-sized, warm-water brachiopods. This succession process of brachiopods in the Permian-Triassic boundary beds appears in many Peri-Gondwanan regions, such as Salt Range of Pakistan (Grant, Reference Grant, Kummel and Teichert1970), Kashmir (Nakazawa et al., Reference Nakazawa, Kapoor, Ishii, Bando, Okimura and Tokuoka1975), and north-central Nepal (Waterhouse and Shi, Reference Waterhouse, Shi, Mackinnon, Lee and Campbell1990). However, these Permian-type brachiopods did not cross the Permian-Triassic boundary at Selong (Shen and Jin, Reference Shen and Jin1999; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Archbold, Shi and Chen2000; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Zhang and Shen2018). In addition, only six Early Triassic brachiopod species have been reported in the Himalayas.

In this study, we found abundant Mesozoic-type brachiopods in Beds 29, 36–42, and 67–70 (late Dienerian–late Smithian, Fig. 2), and their composition and characteristics (as mentioned above) differ completely from those in the Selong Group and Waagenites Bed. Piarorhynchella selongensis n. sp. first appeared in Bed 29, corresponding to the late Dienerian. The three new species identified in this study appeared in early Smithian strata (Bed 36). Although there were only three species in this fauna, they were related to three of the four orders of Mesozoic-type brachiopods. Therefore, recovery of brachiopods after the Permian-Triassic mass extinction may have had an initial phase in the early Smithian in the Himalayas.

Late Smithian extinction of brachiopods