Introduction

The McKay Group of the Bull River Valley has, in recent decades, proved to be one of the best areas in the World to find large numbers of well-preserved, articulated trilobites of mid-Furongian age. The recent discovery of three sites close to each other along the same forestry road in the Bull River Valley (site 15A, 49°43.378′N, 115°18.557′W; site 15B, 49° 43.675′N, 115°18.495′W; and site 15C, 49°43.916′N, 115°18.607′W) containing trilobites that are well preserved, with a high proportion of them preserved as articulated carcasses and molts, adds to the paleobiological data available from this region (see the following). The system of numbering these sites in the Bull River Valley is based on previous publications (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998; Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) and a system set up by local collectors, primarily C. Jenkins and C. New, to label their fossil collections in the Bull River Valley (see Fig. 1 and Acknowledgments). The faunas from each of these new sites are similar to one another (faunal lists are not identical, but the common species occur in all three sites, suggesting they are similar, if not overlapping, in age and belong to the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone). The trilobites from these sites come from a level that is not well represented in earlier works from the region. In particular, they include specimens of two species that were not, or were comparatively poorly, known from other localities of equivalent age (Aciculolenus askewi n. sp. and Cliffia nicoleae n. sp.). Earlier papers on trilobites of Furongian age from the Bull River Valley include the works of Chatterton et al. (Reference Chatterton, Johanson and Sutherland1994), Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998, see for information on earlier collectors of trilobites from this region), Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016), and Lerosey-Aubril et al. (Reference Lerosey-Aubril, Patterson, Gibb and Chatterton2016).

Figure 1. Maps showing Canada, British Columbia, and the Bull River Valley region of southeastern British Columbia, with the location of localities 15A, 15B, and 15C (shown as A, B, and C, near ‘15’ close to the end of the prominent arrow). Other numbers and letters are locations of other Furongian trilobite localities in the region described by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016; see their text-fig. 1).

Because of the numerous complete trilobite carapaces that occur in the region, many specimens have been collected by amateur collectors. In some cases, these collectors have donated important specimens for academic study. Two such rare specimens from a locality at Clay Creek (horizon Tang 8; see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-fig. 2) and from Locality 7B (see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-fig. 4), when combined with a specimen previously published (Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 84, fig. 6, from Tang 8 at Clay Creek), provide adequate material for types of a proposed new species of Labiostria, L. gibbae. This species occurs in outcrop at a slightly higher stratigraphic level (the upper part of the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone) than the part of the McKay Group that outcrops at localities 15A–C. I have visited and collected trilobites from all of the localities from which the trilobites in the present work were obtained, but most of the specimens included herein were collected by others (see Acknowledgments) who live in the Canbrook area. In many cases, amateur collectors who collected the specimens included herein have noted that they were found in one of these three localities (Locality 15A, 15B, or 15C), without noting which of them they were collected from. In that case, the location of the specimen is stated as coming from Locality 15.

Geological setting

The stratigraphy of the McKay Group was discussed in some detail by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016), so it is discussed briefly herein.

The McKay Group in the Bull River Valley consists of comparatively deepwater (largely below storm-wave base) calcareous mudstone or shale with minor amounts of thin, discontinuous (from one section to another) argillaceous limestone beds. All the trilobite-bearing levels from the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley that have been described are mid-Furongian in age (although Cambrian trilobites from higher levels have been collected from talus in some of the sections, e.g., containing specimens of the trilobite Briscoia). The strata in this region have undergone low-level metamorphism (but the shale is not phyllitic) and have been subjected to minor folding and faulting. This, combined with areas of cover (dense forest) between the three new localities, is the reason why it is difficult to determine the relative stratigraphic positions of the three new localities (15A to 15C), which are close to one another, but out of sight, along the same curved, forestry road. Because the strata of mid-Furongian age, assigned to the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region, cannot be subdivided readily into continuous distinctive lithological units that can be mapped from one locality to another (or one local valley to adjacent ones), it has not been formally subdivided into formations in this region. Minor faulting and folding occur in the area, which is located in the Rocky Mountains of Canada, so some specimens show signs of distortion as a result of tectonic events. It is apparent from looking up at the ridges surrounding the Bull River Valley that resistant carbonates of younger Cambrian and later formations, lying above the McKay Group, are not horizontal and have been subjected to thrust faulting. However, these massive younger rock units are dipping at comparatively gentle angles and are not distorted into complex folds.

The beds are largely calcareous mudstone to calcareous shale, and they have, during early diagenesis, undergone substantial dewatering. This has caused a variable degree of compression, particularly flattening, of the fossils that they contain (causing their exoskeletons, when viewed dorsally, to be slightly longer and distinctly wider than they were during life), since almost all of the exoskeletons were deposited parallel to bedding planes. In these new sites, most of the trilobites are preserved by the calcite of their original exoskeletons, with some of them coated by thin layers of additional calcite, or they are sitting on or within wafers of diagentically added calcite (see Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998, p. 5–7, fig. 6). Unfortunately, thin coatings of calcite on the carapaces of some of the specimens proved impossible to remove without damaging the specimen. The preservation of the trilobites in this region is discussed at greater length by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016).

The object of the present work is to document these trilobites to improve our knowledge of trilobite systematics and biostratigraphy for the Furongian of northwestern Laurentia.

Trilobite faunas and biogeography

The commonest trilobite or agnostid species, found in all three of these new sites, include Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, Proceratopyge rectispinata (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937), Pseudagnostus cf. P. josepha (Hall, Reference Hall1863), Pseudagnostus securiger (Lake, Reference Lake1906), and Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016. Rather less common taxa include Aciculolenus askewi n. sp. (found to date only in sites 15A and 15B and Locality 7C of Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016), Agnostotes orientalis (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935), Cliffia nicoleae n. sp. (only three specimens found), Grandagnostus? species 1 of Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, Elvinia roemeri (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861), Eugonocare? phillipi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, Proceratopyge canadensis (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998), Irvingella convexa (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935), Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, Irvingella flohri Resser, Reference Resser1942, Housia vacuna (Walcott, Reference Walcott1912), and Pseudeugonocare bispinatum (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1962). One juvenile specimen of Pterocephalia was collected from Locality 15. While the trilobites illustrated herein are holaspides, smaller growth stages, mainly meraspides but including rare protaspides, have been found at the Locality 15 sites.

Most of the specimens available for the present work were collected by others (mostly enthusiastic, and often knowledgeable, amateurs). Collection in the field, and selection for presentation to me for the present work, was guided by such factors as quality of preservation, completeness of the specimen, rarity of the species, and aesthetic qualities of the species (e.g., Aciculolenus askewi n. sp. was often selected over less-attractive species). Thus, rare and more aesthetic taxa are almost certainly overrepresented in the collections. Providing an accurate count of the relative abundance of the various taxa in each of these localities was apparently not a priority of most of the collectors, and so attempting to provide one in the present work would be misleading.

Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) discussed in some detail the biogeographic relationships of the Jiangshanian trilobite faunas of the Bull River Valley of southeastern British Columbia. They posited that these Canadian Furongian faunas, apart from those found in some other regions of Laurentia, are most similar to those of Korea and South China. The species documented for the first time from this region herein, in particular Pseudagnostus securiger, support those findings.

Biostratigraphy

The biostratigraphy and biogeography of the mid-Furongian trilobite faunas from the Bull River Valley were discussed by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). The importance of the present collections lies not only in the illustration and description of new species from the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone but also in describing a diverse and well-preserved trilobite fauna from a part of that subzone that is not well represented in earlier works from the region. Some additional morphological details of species previously described are also provided (e.g., details of the axial prosopon, rostral plate, and hypostome of Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). This should improve systematics and correlation with other regions on the basis of trilobites or agnostids.

The fauna described herein is older than the trilobite fauna described by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and can be correlated with some of the older (but not the oldest) trilobite collections described from the same region by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-fig. 6). Compared with the latter work, the trilobite faunas described herein are closest in age to the trilobites that occur in trilobite Locality 7C of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-figs. 4, 6) and are probably roughly equivalent to or slightly younger than the oldest trilobite-bearing levels in Clay Creek of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-figs. 2, 6). This would place these collections from Locality 15 somewhere near or below the middle of the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone (see Fig. 2). The trilobite specimens collected from Locality 7C are not as well preserved or as diverse as those described and illustrated herein from Locality 15. Species that appear particularly characteristic of this level within the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone, rather than higher levels within that zone, include Aciculolenus askewi, Cliffia nicoleae, Eugonocare? phillipi, Irvingella convexa, Olenaspella chrisnewi, Proceratopyge rectispinata, Pseudagnostus securiger, Pseudeugonocare bispinatum, and Wujiajiania lyndasmithae. Pseudagnostus securiger has not been previously reported from the Bull River Valley. Choi et al. (Reference Choi, Lee and Sheen2004) found Pseudagnostus securiger in the Machari Formation of Korea in the Eochuangia hana Zone, below the Agnostotes orientalis Zone. In Locality 15, Pseudagnostus securiger and Agnostotes orientalis occur together. However, it is noted in the Systematics section that specimens of Agnostotes orientalis from Locality 15 are slightly different from Agnostotes orientalis specimens from higher in the Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone. Naimark and Pegel (Reference Naimark and Pegel2017, p. 1228) noted that specimens identified as Sulcatagnosts sp. aff. S. securiger have been collected from the Siberian Platform in strata that have been assigned to the lowermost Aksayan Stage and the Sakian Stage (= Jiangshanian). The beds exposed at Locality 15 are probably early Jiangshanian in age.

Figure 2. Diagram showing the approximate stratigraphic position of Locality 15 within some Laurentian biozones (see Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998; Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) and the appropriate biomeres of Palmer (Reference Palmer1965b). The FAD of Agnostotes orientalis is regarded as a useful marker for the base of the Jiangshanian Stage of the Furongian Series (Terfelt et al., Reference Terfelt, Eriksson, Ahlberg and Babcock2008; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock, Zuo, Zhu, Lin, Yang, Qi, Bagnoli and Wang2012). The boundary between the Pterocephaliid and Ptychaspid biomeres is associated with an important trilobite extinction event (Saltzman, Reference Saltzman1999).

Whittington et al. (Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997) listed Pseudagnostus securiger as being found in upper Cambrian strata in a number of countries: England in the Olenus cataractes Subzone; Canada (Northwest Territories) in the Olenaspella regularis Zone; China (Zhejiang) in the Lotagnostus punctatus Zone (?Xinjiang, ?Hunan) and in an uncertain zone; and Australia (Tasmania) in the Olenus Zone. Shergold (Reference Shergold1977) noted that A.R. Palmer had informed him in a personal communication that he had found Pseudagnostus securiger in Elvinia Zone beds in Nevada, USA. Ergaliev et al. (Reference Ergaliev, Zhemchuzhnikov, Popov, Bassett and Ergaliev2014) showed a species of Sulcagnostus [sic], S. trispinus, a possible synonym of Pseudagnostus securiger, occurring in lower Jiangshanian strata in Kazakhstan. Sulcagnostus is not listed as a genus by either Whittington et al. (Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997) or Jell and Adrain (Reference Jell and Adrain2003) and is a nomen nudum (although there does appear to be a genus called Trisulcagnostus Ergaliev, Reference Ergaliev1980, from the Furongian of Kazakhstan).

Paleoecology

The paleoecology of the trilobite-bearing levels of the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region of southeastern British Columbia was discussed by Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) and Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). A majority of the trilobites found in the three new localities are articulated (both molt and carcass carapaces, the latter showing all the sclerites still associated in the correct relative positions). Most of the articulated trilobite carapaces lie parallel to bedding planes. In the same beds as the trilobites, there are a few, mostly sessile, benthic fossils of filter-feeding organisms, such as brachiopods (mainly Linguliformea, but rare Rhynchonelliformea), dendroid graptolites (Dendrograptus cf. D. hallianus (Prout, Reference Prout1851), see Lochman, Reference Lochman1964), and a complete glass sponge (Hyalospongea). From their morphology and what we know of almost all other Cambrian trilobites, the trilobites found in these new localities lived on or near the seafloor for most if not all of their lives (were benthic or nektobenthic). Schoenemann et al. (Reference Schoenemann, Clarkson, Ahlberg and Álvarez2010) argued that one very small, spiney olenid trilobite, Ctenopyge ceciliae Clarkson and Ahlberg, Reference Clarkson and Ahlberg2002, from the Furongian, was pelagic. This claim was based as much on details of the size, arrangement, and form of the lenses of the eyes as it was on the overall size and form of the carapace of Ctenopyge ceciliae. Aciculolenus askewi n. sp. is also a small, spiny olenid trilobite. However, it grew to a much larger size (by nearly an order of magnitude) than C. ceciliae, has rather different eyes, has marginal spines that extend only laterally and/or dorsally (not ventrally), and was almost certainly benthic or nektobenthic for most if not all of its life cycle. Clarkson et al. (Reference Clarkson, Ahlgren and Taylor2004) believed that some other, rather larger, species of Ctenopyge had benthic and/or nektobenthic life habits, at least after the earliest growth stages. They were certainly prepared to consider the suggestion of Fortey (Reference Fortey1999, Reference Fortey2000) that some olenid trilobites may have been chemoautotrophic symbionts, living on bacteria on or in the substrate. That life mode would certainly have been possible for some of the species that are described herein (Aciculolenus and Wujiajiania are olenids). Other possible candidates for such a lifestyle might be Eugonocare, Proceratopyge, Pseudeugonocare, and even some agnostids.

It is likely that many, if not all, of the trilobites from Locality 15 were deposit feeders or feeders of fine organic material (perhaps surface bacterial films in some cases) at or close to the sediment surface. Unless some of the trilobites were active predators, it is likely that most of the organic material available as food in this comparatively quiet and deep marine environment would have been on or in the sediment of the seafloor. The presence of a few small brachiopods, a glass sponge, and dendroid graptolites does suggest that there was enough food in suspension in the water column to support some filter feeders. However, the small size and paucity in numbers of suspension filter-feeding fossils found in Locality 15 suggests that the amount of food in suspension was limited. Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Lerosey-Aubril and Esteve2014) made a convincing case from analyses of the gut contents of a ‘ptychopariid’ trilobite from the Cambrian of China that that animal was a deposit feeder. Chatterton et al. (Reference Chatterton, Johanson and Sutherland1994) argued that the preserved gut beneath some specimens of Pterocephalia from the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region (at stratigraphic levels slightly higher in the same region but in sedimentary rocks that are very similar to those found in Locality 15) are supportive of a deposit-feeding life mode.

Some horizontal burrows and other trace fossils in the calcareous shale found in the three localities from which the present trilobites were collected provide evidence of benthic organisms living on and in the seafloor in these locations during the mid-Furongian. These trace fossils are not common as the uniform nature of the fine-grained marly shale and/or mudstone that outcrops at these localities is not well suited for preservation of trace fossils.

The muds that became the shales and calcareous mudstones of this mid-Furongian part of the McKay Group were deposited in a marine environment. They were deposited below a moderate depth of water (below fair-weather wave base and probably below storm wave base for most, if not all, of the time) as the fossils show little evidence of having been moved around by currents on the seafloor. There is little evidence of winnowing or transport of the fossils. The beds sometimes show fine laminations parallel to bedding. As with other localities in the region, sedimentation of the mid-Furongian part of the McKay Group was probably comparatively rapid in a low-energy environment, allowing for the frequent preservation of articulated carapaces (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998; Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016; Lerosey-Aubril at al., Reference Lerosey-Aubril, Patterson, Gibb and Chatterton2016). Much of the sediment may have accumulated in this area at that time as distal obrution deposits. It is also possible that the fine laminations could be distal turbidites, but they show none of the obvious signs of more proximal turbidites such as Bouma sequences (Bouma, Reference Bouma1962), erosion, tool marks, graded bedding, and so on.

One of the distinctive features of the mid-Furongian trilobite faunas of the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region is the absence of enrolled specimens. Many thousands of articulated trilobite specimens have been collected from this region, so this absence is unlikely to be an artifact of insufficient collecting. Rare specimens have been found where a part of the carapace (such as the back of the thorax and the pygidium) has been folded under or over the rest of the carapace, and one specimen was illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 79, fig. 7) that appears to be partly enrolled, but it is difficult to tell whether this specimen is a distorted enrolled specimen or a specimen that was partly enrolled during sediment movement after death. This is equally true for the specimens collected from Locality 15. The absence of enrolled specimens could suggest a paucity of predators and/or a low-energy environment where the animals were not endangered by themselves being moved or by other objects being moved by currents on the seafloor. There is little doubt that most, if not all, mature trilobites were capable of partial or complete enrollment. One specimen of Housia vacuna (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890) does show some signs of what appears to be damage and repair to the thorax (see Systematic paleontology). This could have resulted from a failed attack by a predator. Large coprolites containing trilobite sclerites and small trilobites and agnostids have been found in other Furongian sections of the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region, mostly at higher stratigraphic levels. These Furongian coprolites from the McKay Group often contain large numbers of scales of polychaete annelid worms.

Materials and methods

The only species treated in detail in the following (including diagnosis, description, and remarks) are those proposed as new species. Other arthropod taxa from the McKay Group, illustrated and mentioned herein, for the sake of brevity and the lack of new morphologic data of significance that are not obvious in the illustrations, are provided with brief synonymies and discussions.

Most of the specimens were coated with black watercolor paint (that can be removed with detergent and water); and after the specimens were dried, they were coated with a sublimate of ammonium chloride before macro photography (using Nikon cameras and a variety of macro lenses). Most of the final images are the result of numerous stacked photographic images. The camera and lens were moved toward the specimen using a StackShot automated-focus stacking rail (at increments varying from 10 to 200 microns, depending upon magnification) while numerous images were made. Focus stacking of the resultant images was accomplished by using either Helicon Focus or ZereneStacker 2 programs in an Apple iMac computer to provide images with greater depth of field.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

Types and figured specimens from the present work are housed in the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM type numbers), 675 Belleville Street, Victoria, BC V8W 9W2, Canada, with the exception of one of the paratypes of Labiostria gibbae n. sp., which is in the type collection of the University of Alberta (UA type number), Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6 G 2E3, Canada.

AGSO numbers are given to specimens in Geoscience Australia's fossil collection housed in Canberra, Australia, 101 Jerrabomberra Avenue, Symonston, ACT 2609, Australia. A.M.N.H. numbers belong to specimens in the type collections of the American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West and 79th Street, NY, NY 10024, USA. C.G.S. specimens refer to specimens in the Canadian Geological Survey type collections, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E8, Canada. GSM numbered specimens are housed in the British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, England. Lund LO specimens are housed in Lund University, Box 117, 221 00 Lund, Sweden. PA and SNUP numbered specimens can be found in the Paleontological Collections of Seoul University, 163 Seoulsiripdaero (90 Jeonnong-dong), Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130–743, South Korea. UA specimens are in the type collections of the University of Alberta (see above for address). UMAT-PA numbered specimens are stored in the University Museum, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan. Specimens with U.S.N.M. numbers are located in the type collections of the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution (including National Museum Catalogue of Invertebrate Fossils), 10th Street and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560, USA. Specimens with UT numbers are saved at the University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712-1692, USA. YPM (PU) numbers are given to specimens housed in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 208118, New Haven, Connecticut, CT 06520-8118, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Class Uncertain

Order Agnostida Salter, Reference Salter1864

Remarks

There is still a lack of general agreement as to whether agnostids are trilobites (as stated by Fortey in Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997) or a group of arthropods (perhaps crustaceans) outside the class Trilobita (Adrain, Reference Adrain2011). There are enthusiastic proponents of both points of view with regard to the relationship of agnostids to other small forms with few thoracic segments that almost all arthropod specialists would accept as trilobites (e.g., eodiscids; see Fortey in Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997). Since agnostids are similar in form and preservation to fossils accepted to be trilobites, frequently found with them, and useful for biostratigraphy, they are included in the present work. To satisfy those who believe that agnostids belong to a taxon outside Trilobita, they are included in an uncertain class.

Family Agnostidae M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1849

Subfamily Agnostinae M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1849

Genus Grandagnostus Howell, Reference Howell1935

Type species

Grandagnostus vermontensis Howell, Reference Howell1935, by original designation. Holotype cephalon YPM(PU)9736 (Howell, Reference Howell1935, pl. 22, fig. 8; Robison, Reference Robison1988, fig. 12.7; Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997, fig. 239.7).

Grandagnostus? species 1 Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Figure 3.12, 3.13

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Grandagnostus? species 1 Chatterton and Gibb, p. 30, pl. 5, figs. 7, 8, pl. 6, figs. 1, 4, pl. 7, fig. 8.

Figure 3. All specimens are from Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. (1, 2) Pseudagnostus securiger (Lake, Reference Lake1906): (1) dorsal view of latex of external mold of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P933; (2) dorsal view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P934. (3) Pseudagnostus cf. P. josepha (Hall, Reference Hall1863); dorsal view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P935. (4, 7, 8) Agnostotes orientalis (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935): (4) dorsal view of slightly smeared specimen RBCM-P936; (7) ventral view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P937; (8) dorsal view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P938. (5) Proceratopyge rectispinata? (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937); ventral view of hypostome, found with disarticulated molt carcass pieces of P. rectispinata RBCM-P939. (6, 10) Irvingella species B of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016): (6) ventral view of articulated thoracopygon RBCM-P940; (10) dorsal view of partial articulated specimen RBCM-P941. (9) Aciculolenus askewi new species (from Locality 15A or 15B); ventral view of latex cast of articulated posterior portion of thorax and pygidium of paratype RBCM-P942 (note possible incipient marginal spines at tips of first segment of pygidium). (11) Irvingella flohri Resser, Reference Resser1942; ventral view of incomplete and slightly displaced articulated molt or carcass carapace RBCM-P943. (12, 13) Grandagnostus? sp. 1 of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016): (12) dorsal view of partly articulated specimen (partial thoracic segment and pygidium?) RBCM-P944; (13) dorsal view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P945. (1–8, 10–13) Scale bars = 2.5 mm; (9) scale bar = 1.25 mm.

Occurrence

RBCM-P944 and RBCM-P945, from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

Identifying fossils with very few characters is always a problem. Several agnostid genera, including Grandagnostus, Delagnostus, and Leiagnostus, with very few dorsal features are known from strata of Miaolingian to early Ordovician age, but few are well known from Jiangshanian levels. Robison (Reference Robison1988) suggested that Grandagnostus should be restricted to the rather poorly preserved holotype cranidium from the Miaolingian of Vermont, which supposedly has an advanced glabellar node that is not visible on the specimens from British Columbia. However, the node is barely visible on the holotype of the type species (Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997, fig. 239.7) and could be an artifact of preservation. Most of the available Cambrian agnostid genera that have bulbous cranidia showing few morphological features, such as this species, have pygidia with features that are not present in this form from the McKay Group such as a prominent border furrow that runs some distance from the margin (this species has a shallow border furrow that runs close to the margin), vestigial anterior axial furrows, articulating ring furrows, and/or distinct anterolateral articulating facets. I am reluctant to propose a new genus for rare specimens that show few distinctive morphological characteristics (other than absences) and are not perfectly preserved and consequently have assigned these specimens to Grandagnostus with question. For further discussion of this species, see Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, p. 30).

Subfamily Pseudagnostinae Whitehouse, Reference Whitehouse1936

Genus Pseudagnostus Jaekel, Reference Jaekel1909

Type species

Agnostus cyclopyge Tullberg, Reference Tullberg1880 (p. 26) by original designation. Topotypes illustrated by Westergård (Reference Westergård1922, pl. 1, figs. 7, 8), Shergold (Reference Shergold1977, pl. 15, figs. 1, 2), Whittington et al. (Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997, fig. 232.1a, b [3066t and 3067t LO Lund]).

Pseudagnostus cf. P. josepha (Hall, Reference Hall1863)

Figure 3.3

- cf. Reference Hall1863

Agnostus josepha Hall, p. 178, pl. 6, figs. 54, 55.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Pseudagnostus (Pseudagnostus) cf. P. josepha; Chatterton and Gibb, pl. 2, figs. 1–14, pl. 5, figs. 1–3, pl. 6, figs. 1, 4, pl. 7, figs. 4, 6, pl. 8, figs. 1–4, pl. 12, fig. 7, pl. 27, fig. 4 (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

Cotypes A.M.N.H. 311 cranidium and pygidium preserved as sandstone molds Agnostus josepha Hall, Reference Hall1863 (p. 178, pl. 6, figs. 54, 55; see Shergold, Reference Shergold1977, pl. 15, figs. 9, 10).

Occurrence

RBCM-P935 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

Pseudagnostus cf. P. josepha is one of the most widespread and common (stratigraphically and geographically) of the species occurring in the mid-Furongian strata of the McKay Group. Specimens assigned to this taxon from the McKay Group are varied morphologically in such features as the depth of the furrows, with some of the variation being imposed on the specimens during diagenesis (through flattening and distortion). Peng and Robison (Reference Peng and Robison2000, p. 16–17) synomymized a number of species with Pseudagnostus josepha and noted that Pseudagnostus josepha is “very widespread geographically” and is “broadly defined morphologically because of much variation observed both within and between populations.” I agree with this comment because of the large amount of morphological variation shown by the abundant specimens of this species in the Furongian of the Bull River Valley region. The ‘cf.’ is retained here mainly because details of both the morphology and the quality of preservation of McKay Group specimens assigned to this taxon are more variable than in most other species-level taxa from the same strata.

Pseudagnostus securiger (Lake, Reference Lake1906)

Figure 3.1, 3.2

- Reference Lake1906

Agnostus securiger Lake, p. 20, pl. 2, fig. 11.

- Reference Kobayashi1937

Sulcatagnostus securiger; Kobayashi, p. 51.

- Reference Peng1992

Pseudagnostus (Sulcatagnostus) hunanensis; Peng, p. 27, figs. 12h–p.

- Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997

Pseudagnostus (Sulcatagnostus) securiger; Whittington et al., p. 367, fig. 232.5 (illustration of holotype).

- Reference Choi, Lee and Sheen2004

Pseudagnostus securiger; Choi et al., p. 178, fig. 14.9–14.15 (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

Articulated carapace GSM57650 (or BGS57650) Agnostus securiger Lake, Reference Lake1906 (p. 20, pl. 2, fig. 11; see also Shergold, Reference Shergold1977, pl. 15, fig. 13; Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997, fig. 232.5). According to the original paper, the specimen was loaned to Philip Lake by a Mr. Sykes through the assistance of Charles Lapworth and collected from Chapel End, near Nuneaton, 40 feet below an unconformity. Lake (Reference Lake1906) does not include a type number or location.

Occurrence

Plesiotypes RBCM-P933–RBCM-P934 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

Peng and Robison (Reference Peng and Robison2000) considered Kobayashi's (Reference Kobayashi1937) genus Sulcatagnostus to be a junior synonym of Pseudagnostus. Pseudagnostus securiger is distinctive in that it is a typical Pseudagnostus with a posterior median marginal spine. The specimens from the McKay Group at Locality 15 are very similar to those from the Machari Formation of Korea (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Lee and Sheen2004). The Korean specimens were obtained from the Eochuangia hana Zone (‘middle Upper Cambrian’) of the Machari Formation (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Lee and Sheen2004, p. 178). That zone is below the Agnostotes orientalis Zone in the Machari Formation, but in Locality 15, Pseudagnostus securiger occurs with Agnostotes orientalis. The revised Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997) followed Shergold (Reference Shergold1977) and treated Sulcatagnostus as a subgenus of Pseudagnostus, and Pseudagnostus securiger was shown as occurring in a variety of ‘upper Cambrian’ zones in a number of countries (see Trilobite faunas and biogeography). Shergold (Reference Shergold1977, p. 86), while recognizing a ‘Securiger group’ within Pseudagnostus, included only one species within it and commented that Pseudagnostus securiger, the only species in the group, “Apart from its possession of a third, sagittal, pygidial spine, Sulcatagnostus securiger (Lake) compares well with members of the Cyclopyge group, such as Pseudagnostus ampullatus Öpik and P. idalis Öpik, both of which have similar over-all morphology.” It is difficult to justify maintaining the subgenus Sulcatagnostus on the basis of a single characteristic (presence of a median posterior spine) since this character state occurs in other genera of agnostids (e.g., Oidagnostus, Triadaspis, Utagnostus).

Genus Agnostotes Öpik, Reference Öpik1963

Type species

Agnostotes inconstans Öpik, Reference Öpik1963, by original designation. Holotype CPC 4272 (AGSO, Canberra) (Öpik, Reference Öpik1963, pl. 3, fig. 11; Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997, fig. 232.3b).

Agnostotes orientalis (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935)

Figure 3.4, 3.7, 3.8

- Reference Kobayashi1935

Agnostus (Ptychagnostus) orientalis Kobayashi, p. 105, pl. 14, figs. 11, 12.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Agnostotes orientalis; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 32, pl. 4, figs. 1, 3–12; pl. 5, fig. 5 (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

External mold of pygidium UMAT PA0957, from Machari Formation, Yeongwal, Korea (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935, pl. 14, figs. 11, 12; Peng and Babcock, Reference Peng and Babcock2005, fig. 1.1, 1.2).

Occurrence

RBCM-P936–RBCM-P938, from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

This species was described in full and discussed at length by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, p. 33–34). The specimens from Locality 15 are stratigraphically slightly below (older than) the specimens illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, see synonymy). The pygidial deuterolobe is somewhat intermediate in form (slightly more rounded and less angular posterolaterally) between that found in younger specimens of Agnostotes orientalis found in the same region and that in specimens assigned to Agnostotes weugi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016 but is more similar to that of the former species (justifying the assignment to Agnostotes orientalis). This suggests that these slightly earlier forms of Agnostotes orientalis could have given rise to, and are certainly closely related to, Agnostotes weugi.

Class Trilobita Walch, Reference Walch1771

Remarks

All of the polymerid (non-agnostid, non-eosdiscid) trilobites described in the present work (in the following) were placed in the order Ptychopariida in the first treatise on trilobites (Moore, Reference Moore1959). By the time a newer classification appeared in the second treatise on trilobites (Fortey in Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Chang, Dean, Fortey, Jell, Laurie, Palmer, Repina, Rushton, Shergold and Kaesler1997), some of the Cambrian trilobites described herein had moved from the Ptychopariida to the Asaphida (e.g., Ceratopyge, Housia, Proceratopyge, Pterocephalia). Adrain (Reference Adrain2011) proposed a new view of higher-level classification within the class Trilobita (also based upon informed opinion rather than formal phylogenetic analysis). In that work, he proposed an order Olenida that included other taxa formerly included in the Ptychopariida or the Asaphida (e.g., Pterocephaliidae such as Pterocephalia and Housia and Aphelaspididae such as Eugonocare, Labiostria, and Pseudeugonocare moved from Asaphida to Olenida). His Olenida included, among others, the families Olenidae, Pterocephaliidae, and Aphelaspididae that occur herein (e.g., the genera Aciculolenus, Wujiajiania, Housia, Pterocephalia, Labiostria, Eugonocare, Olenaspella, and Pseudeugonocare). His new classification involved leaving 58, largely Cambrian, families of trilobites unassigned as to order (including Elviniidae and Phylacteridae: Elvinia, Irvingella, and Cliffia herein). While Adrain's proposals are most valuable in improving classification at the ordinal level of post-Cambrian trilobites, they were apparently not intended to solve the problem of what to do with many of the families with rather ‘primitive’ (plesiomorphic) morphologies that had previously been lumped together in the order Ptychopariida. He also excluded agnostids from Trilobita and seemed to wish to suppress the use of Swinnerton's (Reference Swinnerton1915) order Ptychopariida, the order that has long been used to group a number of Cambrian trilobite families that may or may not be closely related and monophyletic. The present work should prove useful by providing morphological data that will help to clarify the problem of which and how many trilobite orders should be recognized for Cambrian trilobites. It was decided herein that it is, for the present, better to leave some trilobite genera in the order Ptychopariida than to abandon them to an unknown order or orders.

Order Asaphida Salter, Reference Salter1864

Family Ceratopygidae Linarsson, Reference Linnarsson1869

Genus Proceratopyge Wallerius, Reference Wallerius1895

Type species

Proceratopyge conifrons Wallerius, Reference Wallerius1895 from the uppermost Miaolingian of Sweden.

Proceratopyge rectispinata (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937)

Figures 3.5, 4.7, 5.1, 5.3–5.5, 5.9

- Reference Troedsson1937

Lopnorites rectispinatus Troedsson, p. 35, pl. 2, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Troedsson1937

Lopnorites fragilis Troedsson, p. 36, pl. 2, figs. 3–6.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Proceratopyge rectispinata; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 35, pl. 9, figs. 1–10, pl. 10. figs. 1–7 (see for further synonymy).

Figure 4. All specimens are from Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. (1–6) Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016: (1, 4) dorsal views of articulated molt carapace (free cheeks missing) RBCM-P946; (2) dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P947; (3) ventral view of carcass carapace RBCM-P948; (5) dorsal view of incomplete articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P949; (6) ventral view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P950. (7) Proceratopyge rectispinata (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937); view of several articulated and disarticulated molt and carcass carapaces on latex mold of RBCM-P951. Also present are cranidia of Pseudagnostus and Wujiajiania. (8, 9) Cliffia nicoleae new species: (8) dorsal view of paratype impression of ventral surface (dorsal view of ventral mold) RBCM-P952; (9) dorsal view of holotype articulated, almost complete, carcass carapace RBCM-P953. (1–7) Scale bars = 5 mm; (8, 9) scale bars = 2.5 mm.

Holotype

Partial complete articulated carcass carapace (? PA number) of Lopnorites rectispinatus Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937 (p. 35, pl. 2, fig. 1; see also illustration of holotype in Palmer, Reference Palmer1968, pl. 10, fig. 1).

Occurrence

RBCM-P939, RBCM-P951, and RBCM-P954, RBCM-P956–RBCM-P959, from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

As noted, this species is one of the most common forms occurring at Locality 15 (15A–15C). Proceratopyge rectispinata is clearly closely related to Proceratopyge canadensis, and small growth stages of these two species are much more similar to one another than are mature growth stages, making it difficult to determine which of these two species they belong to.

Proceratopyge canadensis (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998)

Figure 5.6

- Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998

Hedinaspis canadensis Chatterton and Ludvigsen, p. 35, p. 39, fig. 7.6–7.10.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Hedinaspis canadensis; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 36, pl. 5, fig. 4; pl. 11, figs. 1–10; pl. 12, figs. 1–10; pl. 13, figs. 1–10.

Holotype

Incomplete articulated carcass crapace UA11119 (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998, figs. 7.6, 7.10) from Clay Creek Monograph Level, Wujiajiania sutherlandi Subzone of Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia, Canada.

Occurrence

RBCM-P960 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

Specimens assigned to this species from these new localities are similar to the types. They appear to be less abundant than the specimens of the closely related Proceratopyge rectispinata. See discussion of Proceratopyge. See also numerous comparatively well-preserved and articulated specimens of this species from the same region and similar stratigraphic levels illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pls. 11–13). In the illustrations of Troedsson's type species of Hedinaspis (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937; Poulsen in Moore, Reference Moore1959, fig. 196.5a, b), it appears that the pygidium is small and there are numerous thoracic segments, narrowing backward toward the small pygidium. In fact, it was suggested that there might be as many as 24 thoracic segments in that species, and it was contrasted with olenid rather than asaphid trilobites. That is clearly not the case for this Canadian species, which has only nine segments and a large pygidium. In earlier works on this species, it was thought that perhaps the pygidium and back of the thorax of the type species of Hedinaspis had been misinterpreted and that they were fused into a larger pygidium. However, that may well not be the case, and for the present, since this species is clearly closely related to other Proceratopyge species, it is assigned to Proceratopyge.

Family Pterocephaliidae Palmer, Reference Palmer1960

Genus Cernuolimbus Palmer, Reference Palmer1960

Type species

Cernuolimbus orygmatus Palmer, Reference Palmer1960. Holotype cranidium U.S.N.M. 136875, 30–50 feet above the base of Dunderberg Shale, Nevada, USA (Palmer, Reference Palmer1965a, pl. 8, figs. 1, 5).

Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Figures 5.2, 6.1, 6.4

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, p. 39, pl. 16, figs. 1–6, pl. 17, figs. 1–10.

Figure 5. All specimens are from Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. (1, 3–5, 9) Proceratopyge rectispinata (Troedsson, Reference Troedsson1937): (1) dorsal view of articulated molt RBCM-P954; (3) dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P956; (4) dorsal view of incomplete pygidium RBCM-P957; (5) dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P958; (9) dorsal view of articulated molt cranidium and thoracopygon, with free cheek of Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, RBCM-P959. (2) Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016; dorsal view of carcass carapace (shell largely missing) RBCM-P955, showing a ventral median suture. (6) Proceratopyge canadensis (Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998); dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P960. (7, 8) Housia vacuna Walcott, Reference Walcott1890: (7) dorsal view of slightly disarticulated molt carapace RBCM-P961, X2.8 (note this specimen is coated with crystals of calcite); (8) dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace of small holaspis RBCM-P962. Scale bars = 5 mm.

Figure 6. All specimens are from Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. All figures are of specimens from Locality 15, except (7), which is from Locality 7B of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-figs. 1, 4). (1, 4) Cernuolimbus ludvigseni Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016: (1) dorsal view of partly articulated partial molt specimen RBCM-P963; (4) dorsal view of incomplete articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P964. (2, 5) Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016: (2) dorsal view of articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P967; (5) ventral view of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P968. (3, 6) Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016: (3) mostly dorsal view of articulated molt thoracopygon and disarticulated free cheek (in ventral view) RBCM-P965; (6) dorsal view of partly articulated molt RBCM-P966. (7, 9) Pseudeugonocare bispinatum (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1962): (7) Ventral view of incomplete articulated carcass specimen RBCM-P969; (9) dorsal view of incomplete articulated molt with cranidium attached to more anterior 22 thoracic segments RBCM-P970. (8) Irvingella species; dorsal view of small holaspis or large meraspis RBCM-P971. (1–4, 6, 7, 9) Scale bars = 10 mm; (5, 8) scale bars = 2.5 mm.

Holotype

Complete articulated carcass carapace UA13875 from site 7, horizon 7E, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Furongian strata of McKay Group, Bull River Valley, southeastern British Columbia (Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, p. 39, pl. 17, fig. 10).

Occurrence

RBCM-P955 and RBCM-P963–RBCM-P964, from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Zone of the McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

This species is numerous in all three sites at Locality 15 (15A, 15B, and 15C). Most of the specimens found of this species are rather crushed, distorted, and/or incomplete. However, they clearly share the features of the types illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). This species is not known to occur above the Wujijiania lyndasmithae Subzone of the Elvinia Zone in the Bull River Valley region. The articulated carcass carapace of this species illustrated in Figure 5.2 shows clearly the occurrence of a pterocephaliid type of ventral median suture.

Subfamily Housiinae Hupé, Reference Hupé1953

Genus Housia Walcott, Reference Walcott1916

Type species

Dolichometopus (Housia) varro Walcott, Reference Walcott1916 by original designation (Walcott, Reference Walcott1916, p. 74, pl. 65, fig. 1a–e) from the upper Cambrian Orr Formation, Orr Ridge, south of Marjum Pass, House Range, Utah. Holotype, by original designation, cranidium U.S.N.M. no 62831 (see also Walcott, Reference Walcott1925, pl. 18, fig. 4).

Remarks

Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) described two species of Housia from the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley region: Housia canadensis (Walcott, Reference Walcott1912) and Housia vacuna (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890). One of the two specimens available for the present study (Fig. 5.7) is covered by fine calcite crystals and lacks the genal angles, making identification with confidence, at the species level, problematic. This specimen is included in Housia vacuna (below) because what can be seen is very similar to the other, much better preserved, specimen of Housia vacuna (Fig. 5.8).

Housia vacuna (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890)

Figure 5.7, 5.8

- Reference Walcott1890

Ptychoparia vacuna Walcott, p. 271, pl. 21, figs. 8, 12.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Housia vacuna; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 41, pl. 18, figs. 1, 3, 5, pl. 19, figs. 1–3 (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

Cranidium United States National Museum Catalogue Invertebrate Fossil 23862, from Furongian of the Potsdam Terrane Limestone, Spring Hills Creek, Black Hills, Dakota (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890, p. 271, pl. 21, figs. 8, 12 [sketches]).

Occurrence

Two articulated plesiotypes RBCM-P961 and RBCM-P962 from Locality 15C, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone part of the McKay Group, near Cranbrook, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

See the preceding under genus. One of the specimens of this species (Fig. 5.8) shows signs of damage and repair. This is a rare example of what may be predation in the Furongian trilobite faunas from the McKay Group in the Bull River Valley.

The fact that the type specimen of this species is a cranidium is not very helpful in discriminating between this species and Housia canadensis (Walcott, Reference Walcott1912) since one of the main differences between these two species is the presence or absence of a distinct genal spine in holaspid growth stages. The specimens from Locality 15 are somewhat intermediate between specimens of these two species (H. vacuna and H. canadensis) found in the Bull River Valley region in that the genal angle is slightly extended backward into a short rather blunt genal spine, but it lacks the sharper, longer, and more distinct genal spine of H. canadensis (see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 18, fig. 6, pl. 19, figs. 5–7, 9). It is included in H. vacuna herein because its genal morphology is closer to H. vacuna (see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 19, figs. 1–3) than it is to H. canadensis.

Order Ptychopariida Swinnerton, Reference Swinnerton1915

Remarks

This order is included herein to include three trilobite genera that have previously been assigned to the Ptychopariida rather than leave these genera in an unassigned, at ordinal level, limbo. It is realised that some workers (e.g., Adrain, Reference Adrain2011) consider the order Ptychopariida to be, at present, not a useful or practical higher-level taxon.

Family Phylacteridae Ludvigsen and Westrop in Ludvigsen et al., Reference Ludvigsen, Westrop and Kindle1989

Genus Cliffia Wilson, Reference Wilson1951

Type species

Acrocephalites lataegenae Wilson, Reference Wilson1949 from the Furongian Wilberns Formation of Texas.

Diagnosis

See Lochman-Balk in Moore (Reference Moore1959). As pointed out by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016), the genus typically has 10–13 thoracic segments.

Cliffia nicoleae new species

Figures 4.8, 4.9, 7.2

- ?Reference Hohensee and Stitt1989

Cliffia lataegenae (Wilson, Reference Wilson1949) Hohensee and Stitt, fig. 3.21, 3.23 (not 3.22).

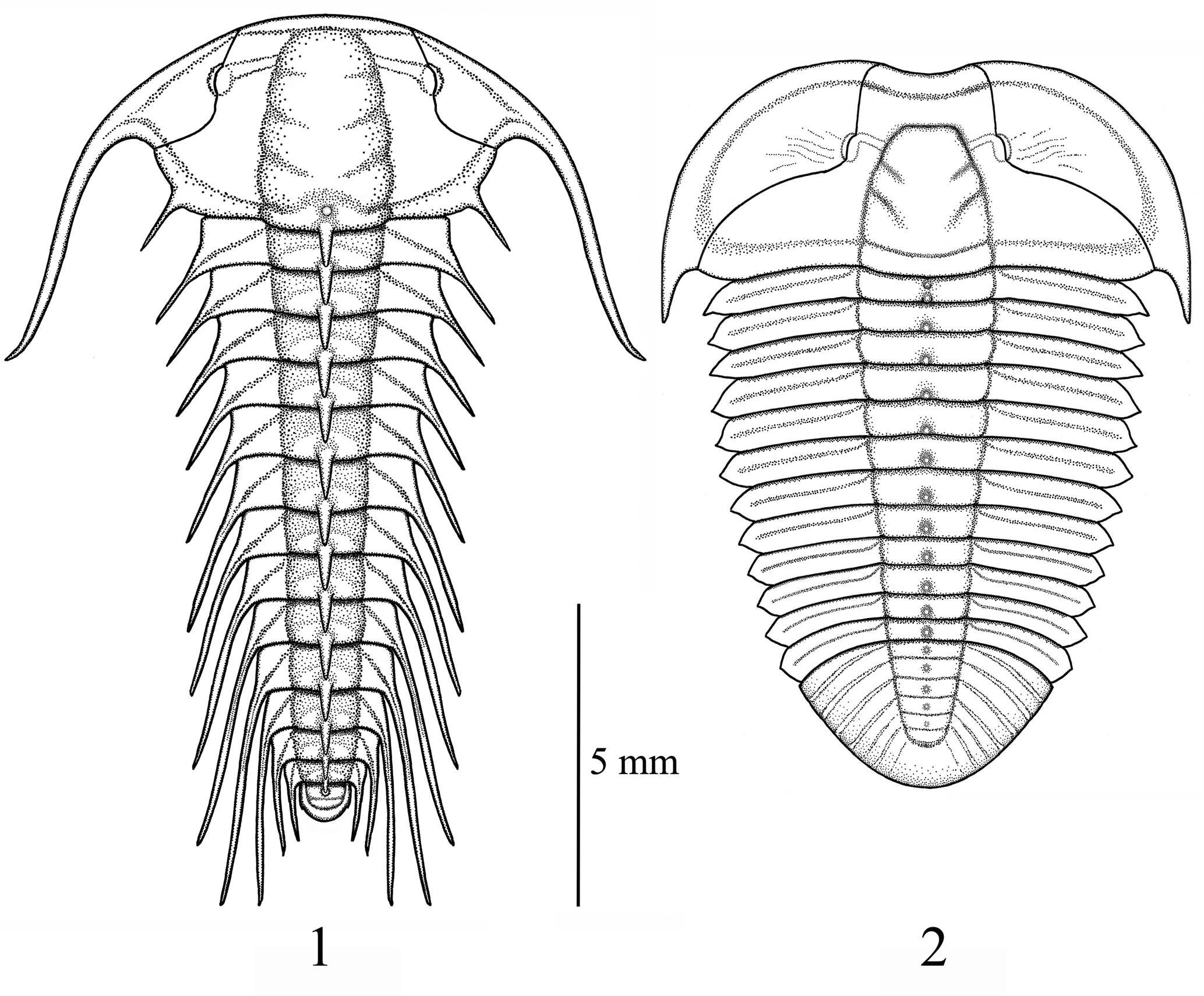

Figure 7. (1) Reconstructive drawing of Aciculolenus askewi new species. (2) Reconstructive drawing of Cliffia nicoleae new species. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Holotype and other types

Holotype RBCM-P953 (Fig. 4.9) and paratype RBCM-P952 (Fig. 4.8) and paratype pygidium RBCM-P988 (not illustrated) from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Furongian strata of the McKay Group, Bull River Valley, near Cranbrook, southeastern British Columbia, Canada.

Diagnosis

Cliffia with 12 thoracic segments, short, pointed genal spines, and distinct axial nodes on thoracic axial rings. Eye is small and far forward, with posterior of eye opposite S2. There are two axial nodes on the first thoracic segment, but the occipital ring lacks an axial node. Single axial nodes also occur on all the other thoracic axial rings and on at least the more anterior axial rings of the pygidium. Pygidium lacks distinct border and border furrow. There are six to seven rings and terminal piece in pygidial axis. Six to seven pairs of narrow, distinct, but not deep pleural and interpleural furrows, of similar depth, run close to each other posterolaterally across pygidial pleurae.

Description

Exoskeleton is moderately arched, with 12 thoracic segments. Prosopon is difficult to discern but may be slightly granulose on cheeks; weak genal caecae appear to be present. Cephalic border furrows are comparatively deep. Axial, occipital, and preglabellar furrows are deep. S1 and S2 are firmly impressed to deep but extend posteromedially less than a third width of glabella. S3 is inconspicuous. Eyes are small and far forward, opposite frontal lobe of glabella. Eye ridges are present and extend outward slightly anterolaterally from frontal lobe of glabella. Preglabellar field is similar in length to or slightly shorter (sag.) than frontal lobe of glabella. Axial furrows converge forward in gentle curve from widest point across occipital ring. Glabella width, across occipital ring, is similar in length to or slightly longer than length (sag.) of glabella (excluding occipital ring). Preglabellar furrow is comparatively transverse.

Genal spines on free cheeks are short (only extending back as far as the second or third thoracic segment), sharp, and directed posteriorly. Facial sutures appear to run almost exsagittally from ß to γ and run almost transversely from ε before curving backward to ω. Posterior border furrows run laterally almost transversely. Lateral border furrows are deep, particularly anterolaterally.

The thorax has 12 thoracic segments. The first segment has two median spinose tubercles on axis, and more posterior thoracic segments have single median spinose tubercle. Distinct pleural furrows run outward only slightly behind laterally on each thoracic pleura. Tips of thoracic segments are bluntly angular. Thoracic axis tapers little backward if at all on three to four more anterior thoracic segments and then tapers more distinctly backward to narrower (tr.) pygidial axis.

Pygidial axis has five to six rings and a small terminal piece. Single median spinose tubercle is present on most pygidial axial rings. Axis is distinctly arched. Narrow but distinct interpleural and pleural furrows are present, and they run close to one another, with pleural furrows distinctly deeper than interpleural furrows. Pleural ribs are distinct. Pygidial border furrow is absent or inconspicuous.

Etymology

This species is named for Nicole Iona Chatterton, dedicated grade school teacher and daughter of the author, who is happy to show her students fossils and rocks.

Remarks

Cliffia nicoleae n. sp. occurs in a locality that is older than the strata that contain Cliffia aitkeni Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016 in the same region. It differs from Cliffia aitkeni in having distinct axial nodes on thoracic and pygidial axial rings and shorter and finer (smaller) genal spines. In addition, both articulated types of Cliffia nicoleae have 12 thoracic segments, while the types of Cliffia aitkeni have 13 thoracic segments.

Cliffia nicoleae n. sp. differs from the type species, Cliffia lataegenae (Wilson, Reference Wilson1949), from the “middle part of the Elvinia Zone” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1949, p. 32), in having slightly smaller eyes placed farther forward so that the posterior areas of the fixigenae are longer (exsag.) and a less distinct prosopon of coarse granules on the preglabellar field. However, the types of Cliffia lataegenae consist of a single rather damaged cranidium (the only specimen mentioned by Wilson, Reference Wilson1949). Stitt (Reference Stitt1983) assigned four enrolled specimens from the Davis Formation of southeast Missouri to Cliffia lataegenae (although he illustrated only one of them, fig. 2H–K). He noted that none of these specimens has more than 10 thoracic segments (two fewer than in Cliffia nicoleae) but also that pygidia are missing from all of these specimens so there may have been more segments in the thorax. He also noted small granules on the axial rings of segments 1–5, two axial nodes on the sixth thoracic segment, and slightly posteriorly directed, short axial spines on segments 7–10 (clearly not the same as the pattern of axial tubercles on Cliffia nicoleae). In addition, the specimen that he illustrated and assigned to Cliffia lataegenae has an obvious axial node on the occipital ring (not present on the types of Cliffia nicoleae). Other differences between this specimen and the types of Cliffia nicoleae include the position of a larger eye farther back opposite S1–L3, a narrower (tr.) glabella, and a more convex forward anterior margin to the cranidium. Cliffia nicoleae shows some similarity to two of the three specimens from the Elvinia Zone Collier Shale of the Ouichita Mountains, west-central Arkansas, assigned by Hohensee and Stitt (Reference Hohensee and Stitt1989, fig. 3.21–3.23) to Cliffia lataegenae. The cranidium of the Hohensee and Stitt specimens has a shorter preglabellar field and a slightly more tapered forward glabella but has eyes that are in a similar position to those of Cliffia nicoleae. The pygidium assigned by those authors to Cliffia lataegenae has a distinct border furrow (not present in Cliffia nicoleae) and a greater number of more prominent pleural ribs. The free cheek that they illustrated is quite similar in form to that of Cliffia nicoleae. Thus, the cranidium and free cheek are assigned with question herein to Cliffia nicoleae, but the pygidium is not.

Stitt (Reference Stitt1983, fig. 2L–U) illustrated two enrolled specimens that he assigned to Cliffia wilsoni Lochman, Reference Lochman1964. These specimens differ from Cliffia nicoleae in having a narrower (tr.) axis, larger eyes placed farther back on the cephalon, and distinct granular ornament on the axial rings of the thorax (without the obvious axial nodes of Cliffia nicoleae). Stitt's specimens share with Cliffia nicoleae a thorax with 12 segments. Lochman (Reference Lochman1964, pl. 11, figs. 11–22) illustrated a number of types (disarticulated sclerites) for her new species Cliffia wilsoni, from the subsurface Deadwood Formation of Montana. These differ from Cliffia nicoleae in having a more inflated preglabellar field medially, slightly larger eyes that are placed slightly farther back (the back sides of the palpebral lobe are opposite the middle of L2 rather than S2), a pygidial axis that appears rather wider (tr.) when compared to its length and (at least in some specimens) appears distinctly flared outward near its anterior margin, pleural and interpleural furrows of the pygidium that are more backward directed and almost merged to form a much deeper joint furrow, and more-distinct pleural ribs on the pygidium. Kurtz (Reference Kurtz1975) illustrated a specimen that he assigned to Cliffia wilsoni from the top of the Elvinia Zone. This small specimen differs from Cliffia nicoleae in having a much longer (sag.) anterior border medially and much larger eyes (distinct palpebral lobes) that extend back farther in the cranidium.

Cliffia nicoleae lacks the large eyes of Cliffia magnacolis Hohensee and Stitt, Reference Hohensee and Stitt1989 (see Hohensee and Stitt, Reference Hohensee and Stitt1989, figs. 3, 17–20). Cliffia nicoleae also has a narrower pygidial axis.

Family Elviniidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Genus Elvinia Walcott, Reference Walcott1924

Type species

Dikelocephalus roemeri Shumard, Reference Shumard1861 (p. 220), from the Furongian of Texas (see Lochman-Balk in Moore, Reference Moore1959, fig. 219.3a–d).

Remarks

The type species of this genus, Elvinia roemeri, is widespread and an important zone fossil, the name bearer of the Elvinia Zone, which includes all of the strata that produced the trilobites described in the present work.

Elvinia roemeri (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861)

Figure 8.3, 8.4

- Reference Shumard1861

Dikelocephalus roemeri Shumard, p. 220

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Elvinia roemeri; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 55, pl. 33, figs. 1–11, pl. 34, figs. 1–8, pl. 35, figs. 1–3, pl. 80, fig. 8 (see for further synonymy).

Figure 8. All specimens are from Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. (1, 2) Olenaspella chrisnewi Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016: (1) detailed ventral view of anteriormost part of cephalon of articulated carcass carapace (note rostral plate) RBCM-P948 (see Fig 4.3); (2) detailed ventral view of anteriormost part of cephalon of articulated carcass carapace (note gap where rostral plate is missing, see Fig. 4.6) RBCM-P950. (3, 4) Elvinia roemeri (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861): (3) dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace of Elvinia roemeri RBCM-P989; (4) dorsal view of almost complete articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P990. (5) Pterocephalia sp.; dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace of meraspid degree 6 RBCM-P991. (6) Eugonocare? sp. A.; dorsal view of anterior part of articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P992. (7) Irvingella convexa Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935; dorsal view of articulated molt thoracopygon RBCM-P993. (8, 9) Eugonocare? phillipi Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016): (8) dorsal view of articulated cephalon and three anteriormost thoracic segments RBCM-P994; (9) dorsal view of slightly distorted articulated carcass carapace RBCM-P995. (10) Irvingella flohri Resser, Reference Resser1942; dorsal view of articulated molt thoracopygon RBCM-P996. (11) Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016); ventral view of external mold of posterior end of incomplete articulated carapace RBCM-P966 (see Fig. 6.6). (1, 2, 5, 7, 10) Scale bars = 2.5 mm; (3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11) scale bars = 5 mm.

Holotype

Cranidium neotype U.S.N.M. 70259, Dikelocephalus roemeri Shumard, Reference Shumard1861. Not illustrated by Shumard, and his original types have been lost, but see history and extensive discussion and photographic illustration of types of this species in Bridge and Girty (Reference Bridge and Girty1937, p. 253, pl. 69, figs. 1–22). Drawings were included in the first edition of the treatise (Lochman-Balk in Moore, Reference Moore1959, fig. 219.3).

Occurrence

RBCM-P989–RBCM-P990, from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

This species is fairly rare in Locality 15, but its presence supports the assignment of that locality to the Elvinia Zone. There is some variability in the specimens of Elvinia from Locality 15, as there is in the specimens illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). One feature that seems to vary is the depth of the posteriorly convex L1 furrow (from almost absent to firmly impressed, Fig. 8.3, 8.4); another feature that varies is the shape (including length-to-width ratio) of the pygidium, with smaller specimens showing shorter and relatively wider pygidia than large specimens. However, the length of the pleural spine of the twelfth (penultimate) thoracic segment is usually much longer on early (stratigraphically lower) specimens of this species than it is on later (higher) specimens. This last difference appears to be biostratigraphic rather than the result of growth allometry. The specimens from Locality 15 have comparatively long pleural spines on the twelfth thoracic segment, supporting their occurrence in the lower part of the Elvinia Zone.

Genus Irvingella Ulrich and Resser in Walcott, Reference Walcott1924

Type species

Irvingella major Ulrich and Resser in Walcott, Reference Walcott1924 (p. 58, pl. 10, fig. 3) from the Furongian, locality not stated, but localities mentioned included Appalachians, Mississippi Valley, Rocky Mountains, and Novaya Zemlya.

Remarks

The species of Irvingella in the Bull River Valley region were discussed by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, p. 58–59). A number of species occur in the McKay Group, but only a few of them are represented by numerous well-preserved specimens. Some of the species from this area are represented by numerous articulated specimens that are moderately well preserved. Even fewer specimens of this genus are well preserved. In future, discovery of additional well-preserved specimens from this region may substantially advance our understanding of this widespread and useful genus. As far as I am aware, none of the specimens of this genus collected from Locality 15 have well-preserved cranidia, but several of them are articulated molts with most or all of the thoracopygon preserved, and some of them have an associated free cheek. One of the problems with this genus is that Resser (Reference Resser1942) proposed a large number of species names for Irvingella, with many of them apparently based on geography more than morphology, and most of them are based on inadequate type material. Some Irvingella species such as the type species, Irvingella major, are widespread geographically, suggesting that some species of Irvingella had an unusual ability to disperse (perhaps through pelagic or nektonic growth stages, e.g., Fortey, Reference Fortey1985). Thus, Resser's species, based at least in part on their geographic occurrences in different areas of North America, proved to be flawed, especially as his types usually consist of single, often incomplete, cranidia. Many of his species have been synonymized, but unless the others are considered nomina nuda, further collecting of material in their type sections could prove them to be senior synonyms of later proposed species that are based on much more complete type material. Three different species of Irvingella have been identified in the collections from Locality 15 (see the following).

Irvingella convexa (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935)

Figure 8.7

- Reference Kobayashi1935

Komaspis? convexa Kobayashi, p. 142, pl. 16, fig. 3.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Irvingella convexa; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 61, pl. 8, fig. 5, pl. 80, fig. 7, pl. 84, fig. 1 (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

Cranidium PA0895 identified as Komaspis? convexa Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935 (p. 142, pl. 16, fig. 3; see also illustrations of holotype in Hong et al., Reference Hong, Lee and Choi2003, p. 185, pl. 2, figs. 7, 8).

Occurrence

A single articulated thoracopygon RBCM-P993 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

The specimen from Locality 15 is similar to similar parts of a specimen of this species illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 84, fig. 1).

Irvingella flohri Resser, Reference Resser1942

Figures 3.11, 8.10

- Reference Resser1942

Irvingella flohri Resser, p. 24, pl. 4, figs. 12–14.

- Reference Resser1942

Irvingella adamsensis; Resser, p. 24, pl.4, figs. 7–11.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Irvingella flohri; Chatterton and Gibb, p. 64, pl. 9, fig. 7, pl. 37, figs. 2, 3, pl. 40, figs. 1–9, pl. 42, figs. 1–4, pl. 77, fig. 4, text-fig. 12A (see for further synonymy).

Holotype

Cranidium U.S.N.M. 108667 (Resser, Reference Resser1942, p. 24, pl. 4, figs. 12–14). Specimen from Locality 60, near Richmond Mine, Eureka District, Nevada.

Occurrence

Several articulated thoracopygons RBCM-P943, RBCM-P996 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia. See also occurrences in the Bull River Valley listed previously in synonymy.

Remarks

Several articulated but incomplete specimens of Irvingella flohri were recovered from Locality 15. These specimens differ from the drawing by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-fig. 12A) by having rather longer macropleural spines on the eighth and eleventh thoracic segments, with that on the eighth segment extending well posterior to the tips of the quite long spines on the last (eleventh) thoracic segment, which extend well posterior to the back of the pygidium. These specimens from Locality 15 were collected from a stratigraphic level that is lower than the strata that contain the specimens illustrated by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016), and so earlier specimens of Irvingella flohri may have longer macopleural and genal spines than younger specimens of the same species (a form of anagenetic cline?). However, it is also apparent that few if any of the specimens available to Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) have the ends of the macropleural spines on the eighth segment preserved, so the length of the macropleural spines on that segment may have been underestimated in that work.

Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016.

Figures 3.6, 3.10, 6.3, 6.6, 8.11

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Irvingella species B Chatterton and Gibb, p. 67, pl. 38, fig. 2, pl. 48, figs. 3–5, pl. 80, fig. 4.

Occurrence

RBCM-P940, RBCM-P941, RBCM-P965, and RBCM-P966 from Locality 15, Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, McKay Group, southeastern British Columbia.

Remarks

The specimens of this species from Locality 15 do not provide enough additional morphological information to propose a new species name for the taxon. The stratigraphic levels represented by Locality 15 are slightly older than the localities where this species was documented by Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016).

Order Olenida Adrain, Reference Adrain2011

Family Aphelaspidae Palmer, Reference Palmer1960

Genus Labiostria Palmer, Reference Palmer1954

Type species

Labiostria conveximarginata Palmer, Reference Palmer1954 from the Furongian (‘Franconian, middle and upper parts of Aphelaspis Zone’) of the Riley Formation, Texas. Holotype cranidium UT-32141 from WC-775 (Palmer, Reference Palmer1954, pl. 86, fig. 4).

Remarks

Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) provided an extensive discussion of this genus.

Labiostria gibbae new species

Figure 9.2, 9.4

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Prehousia? sp. Chatterton and Gibb, p. 43, pl. 84, fig. 6.

- Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016

Kindbladia wilsoni Chatterton and Gibb, pl. 77, fig. 5.

Figure 9. All specimens are from mid Furongian sediments of the McKay Group, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia. (1) Specimen is from the ‘Monograph Level’ of Chatterton and Ludvigsen (Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998) at Clay Creek (Wujiajiania sutherlandi Subzone of Elvinia Zone). (2) Specimen is from Clay Creek section, horizon Tang 8 (~33 m below ‘Monograph Level’ of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016). (3) Specimen is from Locality 15 (Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone). (4) Specimen is from Locality 7B of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016) (Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone). (1) Labiostria westropi Chatterton and Ludvigsen, Reference Chatterton and Ludvigsen1998; dorsal view of articulated carcass carapace Topotype RBCM-P972. (2, 4) Labiostria gibbae new species: (2) dorsal view of carapace holotype RBCM-P973; (4) dorsal view of incomplete carcass carapace paratype RBCM-P974. (3) Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016; dorsal view of articulated molt carapace RBCM-P975. Scale bars = 5 mm.

Holotype and other types

Holotype carcass carapace RBCM-P973 (part and counterpart), from about 180 m above base of section at Clay Creek, near Tanglefoot Creek (see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, text-figs. 1, 2, 6), Bull River Valley, northeast of Cranbrook, southeastern British Columbia (Fig. 9.2); paratype RBCM-P974 (Fig. 9.4) from horizon 7B of Section 7 of Chatterton and Gibb (Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016); and paratype UA14311, from same locality as holotype (see Chatterton and Gibb, Reference Chatterton and Gibb2016, pl. 84, fig. 6, pl. 77, fig. 5).

Diagnosis

Species of Labiostria with 11 thoracic segments and comparatively broad and prominent axis that ends some distance from back of pygidium. Glabella tapers slightly forward, with roundly convex anterior margin. Anterior and lateral border furrows on cephalon are broad and concave upward. Palpebral lobes are well developed, quite large, and placed near midlength of glabella. Genal spines are well developed, sharply pointed, and extend back to opposite axis of third thoracic segment. Axis is moderately inflated and tapers uniformly back from occipital ring to front of pygidium. Posteriorly directed thoracic pleural spines increase in length from first to about seventh segment and then decrease in length backward so are short on last thoracic segment. Pygidial axis is much wider (tr.) than long, and convex backward, with one ring and terminal piece. Pygidial pleural lobes are broad, comparatively flat, and have few (one to two) shallow furrows and low ribs; and pygidial border furrow is inconspicuous.

Occurrence

Upper part of Wujiajiania lyndasmithae Subzone of Elvinia Zone, Bull River Valley region, southeastern British Columbia.

Description